Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Review - Ossian and Ossianism in Britain and Germany - A Review Article

Uploaded by

V POriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Review - Ossian and Ossianism in Britain and Germany - A Review Article

Uploaded by

V PCopyright:

Available Formats

Review: Ossian and Ossianism in Britain and Germany: A Review Article

Reviewed Work(s): 'Homer des Nordens' und 'Mutter der Romantik': James Macphersons

'Ossian' und seine Rezeption in der deutschsprachigen Literatur. Vol. IV: Kommentierte

Neuausgabe wichtiger Texte zur deutschen Rezeption by Wolf Gerhard Schmidt and

Howard Gaskill: Ossian and Ossianism: Subcultures and Subversions, 1750-1850 by

Dafydd Moore

Review by: Francis Lamport

Source: The Modern Language Review , Jul., 2005, Vol. 100, No. 3 (Jul., 2005), pp. 740-

746

Published by: Modern Humanities Research Association

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/3739124

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

Modern Humanities Research Association is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and

extend access to The Modern Language Review

This content downloaded from

147.210.116.181 on Mon, 06 Mar 2023 11:47:30 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

OSSIAN AND OSSIANISM IN BRITAIN

AND GERMANY: A REVIEW ARTICLE

'Homer des Nordens' und 'Mutter der Romantik': James Macphers

Rezeption in der deutschsprachigen Literatur. By Wolf Gerha

i-iii); vol. iv: Kommentierte Neuausgabe wichtiger Texte zur de

ed. by Wolf Gerhard Schmidt and Howard Gaskill. Berlin and New York: de

Gruyter. 2003. Vols 1 and n: xx+ 1417 pp.; vol. m: x + 501 pp.; vol. iv: xvi +850 pp.

Vols 1 and n: ?218; vol. 111: ?98; vol. iv: ?138. Vols 1 and 11: ISBN 3-11-017924-5;

vol. 111: ISBN 3-11-017923-7; vol. iv: ISBN 3-11-017937-7.

Ossian and Ossianism: Subcultures and Subversions, iy50-1850. Ed. by Dafydd Moore.

London: Routledge. 2004. 4 vols; 2300 pp. ?425. ISBN 0-415-28894.

James Macpherson's Ossianic poems are among the most remarkable, and in?

fluential, literary phenomena to have arisen from these islands. Macpherson

published his Fragments of Ancient Poetry [. . .] Translated from the Galic or

Erse Language in 1760, followed by Fingal, an Ancient Epic Poem [. . .] together

with Several Other Poems, Composed by Ossian, the Son of Fingal in 1761 and

a further 'reconstructed' epic, Temora, in 1763, together with further shorter

poems and 'a specimen of the original Galic, for the satisfaction of those who

doubt the authenticity of Ossian's poems'. Doubts had indeed already been

forcefully expressed. Macpherson presented the poems as literal translations

from the works of a third-century Gaelic bard. That they certainly were not,

but nor were they entirely the fraudulent concoctions of an unscrupulous Scots-

man on the make, as was roundly declared by numerous Scotophobes, not least

the redoubtable Samuel Johnson. Controversy continued to rage as further

editions of the poems appeared, lasting well into the nineteenth century and

flaring up intermittently beyond it. Mean while the poems had been enthusi-

astically devoured across the entire world of Western civilization, especially in

Germany?thanks no doubt in considerable measure to Goethe's Werther, de?

spite Goethe's later disavowal of his early enthusiasm. In 1901 Rudolf Tombo

set out to trace the fortunes of Ossian in Germany, but got no further than the

1760s, with Klopstock and the would-be German 'bards'.1 Ossian in France

was better served by Paul van Tieghem, who also, in Le Preromantisme, showed

the crucial significance of Ossian in the European sensibility of the time.2 The

last fifteen years or so have seen a great resurgence of Ossian studies in the

English-speaking world, with the monographs by Fiona Stafford and Paul J.

DeGategno, numerous articles by Howard Gaskill (a collected edition of these

scattered publications would be very useful), and not least Gaskill's indispens?

able edition of the poems, based on Macpherson's complete collection of 1765,

and published in 1996, the bicentennial year of Macpherson's death.3 Now, it

would seem coincidentally, two substantial four-volume compendia have ap-

1 Rudolf Tombo, Ossian in Germany (New York: Columbia University Press, 1901).

2 Paul van Tieghem, Ossian en France (Paris: Rieder, 1917); Le Preromantisme (Paris: Rieder,

1924);

3 Fiona Stafford, The Sublime Savage: A Study of James Macpherson and the Poems of Ossian

(Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1988); Paul J. DeGategno, James Macpherson, Twayne's

English Authors Series, 427 (Boston, MA: Twayne, 1989); The Poems of Ossian and Related Works,

This content downloaded from

147.210.116.181 on Mon, 06 Mar 2023 11:47:30 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

FRANCIS LAMPORT 741

peared, tracing and documenting the appe

and critical controversies and the further

Britain and Ireland (Moore) and in the G

Both furnish invaluable material for future

The two works are similar in conception a

in balance. Both present 'original' (the inv

Ossian appropriately cautious) as well as a g

terial, much of it otherwise difficult or ev

notes mostly of a bibliographical character

first editions of the Fragments (in this cas

followed the first in October of the same

volumes in facsimile, thus supplementing

Schmidt gives us the first complete Germ

Gedichte Ossians neuverteutschet, together w

and of Macpherson's and Blair's prefatory

lume iv a selection of other translations (D

Further material (Moore, Volumes 111 and

Gaskill is named as joint editor) documents

tical writings' and 'the creative response' in th

adaptations, etc; Schmidt adopts a further

mit it is not possible to separate these cat

prefaced in Moore's Volume 1 by a succinc

suggestively outlining the main issues raise

other hand, devotes his first two volumes,

work was originally a dissertation presente

to a detailed critical and historical survey,

siderations, then proceeding to analyse the m

aspects, then chronologically author by au

some repetitiousness, compounded by a goo

of argument and of illustrative material,

reduced by judicious cross-referencing. Th

and critical analysis, but a labyrinthine on

fitfully illuminated by the Foucauldian disc

(with some reservations and modifications)

rization. My own preference is for Moore's

Saxon (or rather, in this case, Celtic!) appr

argument is (to my mind) unnecessarily co

historical survey contains a wealth of inform

provocative insights.

That the poems of Ossian aroused an extra

accident: it would seem to have been Macp

intention from the outset. 'Pleasant is the

thura', PO, p. 158), and many readers no doub

of melancholy wash voluptuously over the

ed. by Howard Gaskill, with an introduction by Fion

Press, 1996), henceforth cited as PO.

This content downloaded from

147.210.116.181 on Mon, 06 Mar 2023 11:47:30 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

742 Ossian and Ossianism in Britain and Germany

der Wehmut', first coined by Michael Denis in his version of 'Carric-thura'

(Schmidt, p. 123) and persistently recurring thereafter, is perhaps already more

insidiously ecstatic?almost anticipating Mario Praz's 'Romantic Agony'?and

Werther shows all too plainly to what real tragedy such imaginative wallowing

could lead.) But the poems, as they originally appeared (literally) from the Fin-

gal volume onwards, resist such a simple emotional response, starting off rather,

or in addition, a number of intellectual hares (or, in Schmidt's preferred Fou-

cauldian jargon, initiating 'a series of polyvalent discourses'). Moore's facsimile

reprint reminds us of that original, literal appearance, in which the poems are

accompanied by extensive footnotes, elucidating Gaelic names and historical

references with a great show of (bogus?) scholarship, drawing attention to spe?

cific stylistic features, and establishing Ossian's epic credentials by pointing

out numerous parallels to passages in Homer, Vergil, and Milton. In Gaskill's

edition these notes are relegated to the end of the volume, but here we can see

them as Macpherson's original readers saw them, sometimes occupying more

than half the printed page, so that the reader has, as Gaskill observes, 'to con-

tend with pages containing minimal Ossian and maximal Macpherson, not to

mention Homer and Virgil' (PO, p. xxv, quoted by Moore, 1, lii). Moore stresses

'the need to come to terms with th[is] disruption of the experience of reading'

(ibid.). The notes draw attention to the problematic status ofthe poems, sup-

plementing but diffracting and at times implicitly subverting them. In saying

this, one might perhaps be thought to be imputing a greater degree of modern,

even proto-postmodern, literary self-awareness to Macpherson than is in fact

warranted. And yet the 'Preface' to Fingal in effect anticipates, even invites, all

the major subsequent controversies: on the age and authenticity of the poems,

their poetic merits, and the standards by which these are to be judged?by sup?

posedly universal, enlightened Augustan standards, in comparison with Homer

and company ('Homer ofthe North'), or as 'original compositions' in the pre-

Romantic sense, to be evaluated only by original standards intrinsic, not to

say peculiar, to themselves?; on their reliability as historical characterizations

of a 'primitive' civilization; on the rival claims of Scotland and Ireland to the

origin ofthe poems, and indeed ofthe Gaelic 'nation'. The Irish controversy

is further deliberately stirred up in the prefatory Dissertation to Temora, and a

specifically political provocation, in the Anglo-Scottish dimension, is implicit

in the dedication of Temora (and ofthe complete edition of 1765) to Macpher?

son's widely detested patron Lord Bute (who had meanwhile been the target

of a ribald Ossianic parody, quoted by Moore in Volume 111). Macpherson thus

comes out, as Moore puts it, 'all guns blazing' (1, lvii). At the same time he was

perhaps already becoming 'jealous of Ossian', as Gaskill has suggested (PO,

p. xxiv), implicitly reasserting his own claim to at least a share of Ossian's fame.

A complicated situation indeed for readers to be forced, or at any rate strongly

encouraged, to 'contend with'.

Both Moore and Schmidt also point out that Ossian did not appear, as is

sometimes supposed, completely out of the blue (emerging, fully armed like

Minerva, from swirls of Scotch mist). Moore prints in Volume 1 a number of

Macpherson's earlier poetic works, indicative of his cultural and political patri?

otism; also some important forerunners, Alexander Macdonald's preface to his

This content downloaded from

147.210.116.181 on Mon, 06 Mar 2023 11:47:30 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

FRANCIS LAMPORT 743

The Resurrection of the Scottish Languag

Gaelic poetry to an English-speaking re

tion' of a Gaelic ballad, contributed to t

'translation' implicitly anticipates the d

above, for it assimilates the 'primitive' b

to lie precisely in its primitive qualities)

ling its length, ironing out its Herderia

underlining both its 'heroic' and its sen

simple unrhymed quatrains into elabora

stanzas. Similarly, many later adaptors o

'translators' but working, of necessity, f

from any Gaelic source, also found it des

verse forms, usually heroic couplets?'to

John Wodrow wrote in the introductor

(1769), 'and take occasion, by throwing

Poet's sentiments, to render the narratio

more clear and easy', thereby throwing

son's rhapsodic style (Moore, iv, 80; cf. 1

to the quite un-Ossianically jolly songs

Called Oscar and Malvina, or the Hall of

Tho' the scene of existence be clouded

Yet valour and beauty it's evils begui

To these shall the worthy, the gentle r

Or to live, or to die, by the sword an

[. . .] OSCAR, like the orb of day,

Drives each threat'ning storm away;

Far before his blazing eye,

Swift the mingled squadrons fly.

Let us then united raise

Songs of triumph in his praise [. . .]

(iv, 185, 188)

(The numerous 'dramatic' adaptations seem in fact to have had little success

on the stage, but Moore suggests that they may actually have been intended

primarily for reading rather than performance; this would not have been the

case, though, for operatic and other musical settings.) The critical debates,

particularly those regarding the poems' authenticity, also offer some amusing

moments. William Shaw's Enquiry into the Authenticity of the Poems Ascribed

to Ossian (1781), for example, recounts the lengths to which partisan investiga-

tions (on either side ofthe controversy) would go, ranging in Shaw's case from

creeping into 'humble cottages on all four [sie] to interrogate the inhabitants'

to offering to pay Professor Macleod of Glasgow zs. 6d. a word for genuine

specimens of Gaelic poetry (111, 264, 262). But there is much serious and valu?

able material here, from early reviews to substantial extracts from the report of

4 The date is given differently in the bibliographical note. Without thorough checking of the

often inaccessible sources, one can only hope that there are not too many errors and inconsistencies

of this kind. I noticed, however, a number of errors and infelicities in Moore's Introduction, and

what appeared to be errors of transcription in some of the texts reproduced in Volumes 111 and iv,

marring what is otherwise a very handsome production.

This content downloaded from

147.210.116.181 on Mon, 06 Mar 2023 11:47:30 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

744 Ossian and Ossianism in Britain and Germany

the Highland Society of Scotland's enquiry of 1805 into the authenticity ofthe

poems and the testimonies submitted (111, 366-96).

Comic relief is, however, not in plentiful supply. As Macpherson himself ob?

served, 'If he [Ossian] ever composed any thing of a merry turn, it is long since

lost' (PO, p. 472, note to 'Berrathon', quoted by Schmidt, 1, 131), and in the

German reception, as documented by Schmidt, seriousness and melancholic

gloom prevail. All too appropriate is the Freudian misprint in the Munchner

Ausgabe of Werther, whereby the hero is made to declare: 'Ossian hat in meinem

Herzen den Humor verdrangt.'5 (Can it really be the case, though, as Schmidt

avers, that there is no note of irony in Karl Teuthold Heinze's specification

(quoted by Schmidt, p. 470) for a grotto in Ossianic taste, with a fireplace dis?

guised as a hollow blasted oak and comfortable inglenook seats in stone-coloured

leather?) Schmidt traces in great detail the appearance of the Ossianic poems,

the cultural and political context from which they emerged, and the various 'dis?

courses' which they initiated in the critical reception?philological, aesthetic,

ethical, and cultural-political; finally (for this is Germany) a 'philosophical-

transcendental discourse' in which, taking up Hugh Blair's hint that the poems,

for all their notorious lack of any specific religious or mythological background,

nevertheless seem to offer a 'mythology of human nature' (PO, p. 368), writers

of the high Romantic tendency sought to find in them not merely exemplary

specimens of ancient poetry, or a portrait of a past golden age, or models of

human nature or human society, but a 'Zugang zu den Tiefenstrukturen der

Wahrheit' (p. 476). The poems seem to imply, but also to refute, something like

the favourite Romantic paradigm of a triadic historical progression. Ossian,

from the perspective of an alienated present in which he is forced to 'walk with

little men' (Fingal, Book 3, PO, p. 79), celebrates the great deeds of a heroic

past and sees in this commemorative act some hope for future regeneration, yet

this act (the poetry) is itself doomed to be forgotten; Ossian mourns his father

Fingal, but also his son Oscar, the destined bridegroom of his muse Malvina.

Nevertheless, the poetic act is seen as the sole remaining guarantee, and the

poet as the sole remaining guarantor, of true human values.

This is already powerfully articulated by Goethe, 'der wesentliche Popula-

risator Ossians innerhalb der deutschen Rezeption' (p. 723). Among Goethe's

dramatic figures, Gotz von Berlichingen is stylized, by significant distortion of

history, into an Ossianic poet-hero: like Ossian, the blind bard who was once a

hero, Gotz the man of action is reduced to chronicling his own heroic deeds for

the benefit of a doubtful posterity, and lamenting like Ossian the death (and in

this case the degeneracy) of his son, while Orest and Tasso are both, according

to Schmidt, presented as Ossianic melancholics?though one should observe

that Orest is cured of his paralysing melancholy and returned to the world of

action from which Tasso is barred, recovering only a kind of (Ossianic?) pride

in claiming to be the voice of an otherwise dumb, suffering humanity. From this

a line runs directly to Franz Spunda, the twentieth-century translator of Ossian

(1938), proclaiming the message of the poems to be 'den Hinfall der Welt zu

5 Johann Wolfgang Goethe, Samtliche Werke nach Epochen seines Schaffens, ed. by Karl Richter

and others, 21 vols (Munich: Hanser, 1985?98), 11/ii, ed. by Hannelore Schlaffer, Hans J. Becker,

and Gerhard H. Muller (1987), p. 423.

This content downloaded from

147.210.116.181 on Mon, 06 Mar 2023 11:47:30 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

FRANCIS LAMPORT 745

uberleben als Sieger im Geist' (Schmid

comments on Ossian are increasingly ne

for his early work is, Schmidt argues, d

und Wahrheit, but Ossian continues to i

his 'Asthetik der Dammerung', and he r

Reservoir' (p. 794).

Here, however, we encounter a problem

Schmidt's account. It is undoubtedly tru

major, and perhaps even more the minor,

the appearance of the Ossianic poems we

Ossianic imagery, and though this has b

by the majority of earlier German critic

Schlegel's untypical rejection of Ossian,

of Schiller, Jean Paul, Holderlin, and the

calls 'unmarkierte Ossianintertextualitat'

what point these echoes and reminiscen

actual allusions, to which the reader is e

other than a mere joyously grievous glow

ficult question (and one which Moore, 1,

of wider English patterns of influence).

The case of Kleist is particularly intere

sian, but the latter is, according to Sch

work, and Ossianic reminiscences have '

(p. 927). But the Ossianic images are d

distorted, even reversed in their signif

steht | Dem Sturm, doch die gesunde

emphasis); Penthesilea's suicide is an 'im

lungsmuster' (p. 935)?and Schmidt has e

Werther that according to Macpherson

the ancient Scots (PO, p. 415 n. 28, quot

these supposed Ossianic echoes seems to

of Macpherson's world-view: 'Der domes

lust der Idylle, Kleist laBt sie scheinbar

(p. 937). Is Kleist really using Ossianic r

a set of attitudes and sensibilities which

The problem is aggravated by the fact th

first appearance of Macpherson's Fragm

peppered with Ossianic reminiscences, m

hand; Schmidt refers to this as 'Potenzie

reference here is to Arnim), but in man

signification seems rather diluted than in

6 Kleist's only (surviving) recorded reference to

richs SeelandschafV: see my essay * "Eine wahrhaf

Patriotic Landscapes of the Goethezeit', Publicatio

73. I am now inclined to think that Kleist may h

patriotism of Ossian or Kosegarten (or Friedrich)

not to say bloodthirsty anti-Napoleonic sentimen

beneath the surface of many of the ostensibly unpo

This content downloaded from

147.210.116.181 on Mon, 06 Mar 2023 11:47:30 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

746 Ossian and Ossianism in Britain and Germany

explicit citations, of which there are a good many. The list could no doubt

be extended into the latter half of the nineteenth century, though there is a

slackening-off of literary reception after about 1840?paradoxically, at a time

when scholarly controversy about the authenticity of the poems was undergoing

something of a revival. But Schmidt jumps forward to give us a few examples of

surviving twentieth-century 'creative reception', with Hesse's characters in Un-

term Rad indulging in 'ossianische[] Stimmungen', or the bizarre citations and

montages of Gisela Prast's experimental Ossian novel of 1996. Though Prast's

actual knowledge of Macpherson and his work appears to be very superficial

(Schmidt, pp. 1129-32), it seems that the name of Ossian is still expected to

arouse some recognition and response in a modern German readership.

Limitation of space precludes further detailed discussion, but let it be said

again that these two handsome compilations complement each other to give a

remarkably comprehensive picture of the sixty-odd years of the Ossian pheno?

menon in Britain and Germany.

Worcester College, Oxford Francis Lamport

This content downloaded from

147.210.116.181 on Mon, 06 Mar 2023 11:47:30 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

You might also like

- Myths and Symbols in Pagan Europe: Early Scandinavian and Celtic ReligionsDocument20 pagesMyths and Symbols in Pagan Europe: Early Scandinavian and Celtic ReligionsRichard WooliteNo ratings yet

- Poems of Ossian PDFDocument350 pagesPoems of Ossian PDFerhan savas100% (1)

- Valdambrini46 v2 Dances RSM 013009Document14 pagesValdambrini46 v2 Dances RSM 013009Vicente Rios TlatelpaNo ratings yet

- Generation of Instrument Makers Has Grown Up WithDocument5 pagesGeneration of Instrument Makers Has Grown Up Withyaroslav88No ratings yet

- Giulianiad ContentsDocument6 pagesGiulianiad ContentsMarco Vinicio BazzottiNo ratings yet

- Palestrina and The Roman SchoolDocument7 pagesPalestrina and The Roman SchoolVickyLiuNo ratings yet

- Los Lybros Del Delphín de Música (English)Document5 pagesLos Lybros Del Delphín de Música (English)Xavier Díaz-LatorreNo ratings yet

- Remarks On An Unnoticed Seventeenth-Century French Lute in Sweden, The Swedish Lute (Svenskluta or Swedish Theorbo) and Conversions of Swedish LutesDocument32 pagesRemarks On An Unnoticed Seventeenth-Century French Lute in Sweden, The Swedish Lute (Svenskluta or Swedish Theorbo) and Conversions of Swedish Lutesrodolfo100% (1)

- Sanz Mid. XVII - Early XVIIIDocument2 pagesSanz Mid. XVII - Early XVIIISergio Miguel MiguelNo ratings yet

- Playford Division Violin 1705Document76 pagesPlayford Division Violin 1705Karolina BrachmanNo ratings yet

- m3 Hittites Religion Women and Temple ProstitutesDocument7 pagesm3 Hittites Religion Women and Temple Prostitutesapi-315567627No ratings yet

- Bazzotti - Seicorde - The Guitar of The Czars - SychraDocument10 pagesBazzotti - Seicorde - The Guitar of The Czars - SychraPhilipp Molderings100% (1)

- 996c PDFDocument28 pages996c PDFeNo ratings yet

- Nina Treadwell - Music of The Gods - Solo Song and Effetti Meravigliosi in The Interludes For La PellegrinaDocument52 pagesNina Treadwell - Music of The Gods - Solo Song and Effetti Meravigliosi in The Interludes For La PellegrinaFelipeNo ratings yet

- Giulio Caccini's Published Writings Bilingual Edition by Lisandro AbadieDocument61 pagesGiulio Caccini's Published Writings Bilingual Edition by Lisandro AbadieJulián PolitoNo ratings yet

- The Scandal of The Speaking Body PDFDocument177 pagesThe Scandal of The Speaking Body PDFLeandro GomezNo ratings yet

- Lutebot 2Document14 pagesLutebot 2Mau AlvaradoNo ratings yet

- Pierre AttaingnantDocument4 pagesPierre AttaingnantCole Louis HankinsNo ratings yet

- The Faded Splendour of Lagashite Princesses: A Restored Statuette From Tello and The Depiction of Court Women in The Neo-Sumerian Kingdom of LagashDocument25 pagesThe Faded Splendour of Lagashite Princesses: A Restored Statuette From Tello and The Depiction of Court Women in The Neo-Sumerian Kingdom of LagashSaya AsaadiNo ratings yet

- She Descended On A Cloud From The Highes PDFDocument22 pagesShe Descended On A Cloud From The Highes PDFRoger BurmesterNo ratings yet

- The Spanish Guitar in The Nineteenth and Twentieth CenturiesDocument35 pagesThe Spanish Guitar in The Nineteenth and Twentieth CenturiesRafael Iravedra100% (1)

- 000091348Document16 pages000091348Adrián100% (1)

- Kellner Sonatas y PartitasDocument14 pagesKellner Sonatas y Partitasfakeiaee100% (1)

- pmr0003 Scarlatti BookletDocument17 pagespmr0003 Scarlatti BookletGökhan ArslanNo ratings yet

- Andrea González Caballero: Laureate Series - GuitarDocument6 pagesAndrea González Caballero: Laureate Series - GuitarLeonardo SáenzNo ratings yet

- PChang 2011 Analytical Per Formative Issues v1 TextDocument326 pagesPChang 2011 Analytical Per Formative Issues v1 TextAngelica Stavrinou100% (1)

- Luys Nrvaez Conde Claros Lute Tablature VihuelaDocument2 pagesLuys Nrvaez Conde Claros Lute Tablature VihuelaemasteinNo ratings yet

- Mantovani Thesis 2019Document414 pagesMantovani Thesis 2019Vitor SampaioNo ratings yet

- TanzDocument1 pageTanzkami6127No ratings yet

- Visee Rebours Lsa Article PDFDocument8 pagesVisee Rebours Lsa Article PDFGabrieleSpinaNo ratings yet

- Arthur Rimbaud - IlluminationsDocument30 pagesArthur Rimbaud - IlluminationsAnnie WogelNo ratings yet

- BT1275Document4 pagesBT1275DavidMackorNo ratings yet

- Vogl LosyPragueLutenistDocument20 pagesVogl LosyPragueLutenistadmiralkirkNo ratings yet

- Celt Music: Nicolas Passerini, Bilingual Translation Universidad de MontevideoDocument4 pagesCelt Music: Nicolas Passerini, Bilingual Translation Universidad de MontevideoNico PasseriniNo ratings yet

- Using The Root Proportion To Design An OudDocument5 pagesUsing The Root Proportion To Design An Oudحسن الدريديNo ratings yet

- Journal of Music History Pedagogy: NumberDocument71 pagesJournal of Music History Pedagogy: NumberIvana DjolovicNo ratings yet

- AllText PDFDocument9 pagesAllText PDFRadamésPazNo ratings yet

- Antonio Jose Sonata DeskripsiDocument12 pagesAntonio Jose Sonata DeskripsiRobyHandoyoNo ratings yet

- Granata 1620 21 - 1687Document2 pagesGranata 1620 21 - 1687Sergio Miguel Miguel100% (1)

- Sinier de Ridder - Lacote A Paris GB PDFDocument9 pagesSinier de Ridder - Lacote A Paris GB PDFAndrey BalalinNo ratings yet

- Lycian Way Program Make Your Own ProgramDocument4 pagesLycian Way Program Make Your Own ProgramperacNo ratings yet

- Adrian Le RoyDocument3 pagesAdrian Le RoyIgnacio Juan GassmannNo ratings yet

- Pagina 2 TraducidaDocument2 pagesPagina 2 TraducidaChristianDiazNo ratings yet

- Frescobaldi, Froberger and The Art of FantasyDocument2 pagesFrescobaldi, Froberger and The Art of Fantasy方科惠100% (1)

- Elites in The Cemetry of Hallstatt UpperDocument23 pagesElites in The Cemetry of Hallstatt UpperelfifdNo ratings yet

- Bells For Cittern: R R R R LLLLLLLLLLLLLLLLLLLLLLLL R R R R RDocument2 pagesBells For Cittern: R R R R LLLLLLLLLLLLLLLLLLLLLLLL R R R R RTio Jorge100% (1)

- "In Te Domine Speravi" - From Frottola To Real Lute MusicDocument7 pages"In Te Domine Speravi" - From Frottola To Real Lute Musicapi-3862478100% (2)

- Gan2018 PHD PDFDocument369 pagesGan2018 PHD PDFClarence TanNo ratings yet

- Foscarini - 1629 47Document2 pagesFoscarini - 1629 47Sergio Miguel MiguelNo ratings yet

- FrottolaDocument10 pagesFrottolayayabaoNo ratings yet

- SYmphony 9 BrucknerDocument41 pagesSYmphony 9 BrucknerLê Đoài HuyNo ratings yet

- An Analysis of Villa-Lobos Early Guitar Works - The Synthesis of ADocument27 pagesAn Analysis of Villa-Lobos Early Guitar Works - The Synthesis of ANgvinh PieNo ratings yet

- A2 4231Document52 pagesA2 4231chitarrone1700No ratings yet

- TimpleDocument8 pagesTimpleJorge LaurentinoNo ratings yet

- France & Low Countries: ORNAMENTS (Agrémens) and Other SignsDocument5 pagesFrance & Low Countries: ORNAMENTS (Agrémens) and Other SignsPaulinhodeJesusNo ratings yet

- DowlandRobert Varietie Part1Document40 pagesDowlandRobert Varietie Part1Raúl Vergel CantilloNo ratings yet

- Brescianello 1690 - 1758Document2 pagesBrescianello 1690 - 1758Sergio Miguel MiguelNo ratings yet

- COMSOL WebinarDocument38 pagesCOMSOL WebinarkOrpuzNo ratings yet

- Carjau Aurelia Nicoleta - ENDocument1 pageCarjau Aurelia Nicoleta - ENFirst CopyNo ratings yet

- GRFU Description: Huawei Technologies Co., LTDDocument9 pagesGRFU Description: Huawei Technologies Co., LTDJamal HagiNo ratings yet

- High Temperature Materials An Introduction PDFDocument110 pagesHigh Temperature Materials An Introduction PDFZeeshan HameedNo ratings yet

- Grade 8 RespirationDocument6 pagesGrade 8 RespirationShanel WisdomNo ratings yet

- MK3000L BrochureDocument2 pagesMK3000L BrochureXuân QuỳnhNo ratings yet

- Sop 905Document10 pagesSop 905harryNo ratings yet

- Transportation Research Part C: Xiaojie Luan, Francesco Corman, Lingyun MengDocument27 pagesTransportation Research Part C: Xiaojie Luan, Francesco Corman, Lingyun MengImags GamiNo ratings yet

- Apartments? Not in My Backyard. Stouffville & Affordable Housing. Presentation To Public HearingDocument14 pagesApartments? Not in My Backyard. Stouffville & Affordable Housing. Presentation To Public HearingArnold Neufeldt-FastNo ratings yet

- Rough Translation of Emil Stejnar's Schutzengel BookDocument119 pagesRough Translation of Emil Stejnar's Schutzengel BookJustA Dummy100% (1)

- Steam Turbine and Condenser Lab Report FullDocument2 pagesSteam Turbine and Condenser Lab Report FullJoshua Reynolds0% (3)

- Middle East Product Booklet 5078 NOV18Document56 pagesMiddle East Product Booklet 5078 NOV18Mohamed987No ratings yet

- CAE Listening Practice Test 13 Printable - EngExam - InfoDocument2 pagesCAE Listening Practice Test 13 Printable - EngExam - InfoCarolina MartinezNo ratings yet

- Chapter 15.1.2.3 DC Drives PPT II Spring 2012Document56 pagesChapter 15.1.2.3 DC Drives PPT II Spring 2012Muhammad Saqib Noor Ul IslamNo ratings yet

- Mud Motor DV826Document1 pageMud Motor DV826CAMILO ALFONSO VIVEROS BRICEÑONo ratings yet

- Fatigue BasicsDocument30 pagesFatigue BasicsABY.SAAJEDI879No ratings yet

- Computer Architecture and Organization: Intel 80386 ProcessorDocument15 pagesComputer Architecture and Organization: Intel 80386 ProcessorAtishay GoyalNo ratings yet

- IO InterfacingDocument10 pagesIO InterfacingAxe AxeNo ratings yet

- Citizen ManualDocument18 pagesCitizen ManualWalter MeinneNo ratings yet

- Biology 20 Unit A Exam OutlineDocument1 pageBiology 20 Unit A Exam OutlineTayson PreteNo ratings yet

- Literature & MedicineDocument14 pagesLiterature & MedicineJoyce LeungNo ratings yet

- Ericsson - Cell PlanningDocument5 pagesEricsson - Cell PlanningBassem AbouamerNo ratings yet

- Electronic Transformer For 12 V Halogen LampDocument15 pagesElectronic Transformer For 12 V Halogen LampWin KyiNo ratings yet

- Courses Offered in Spring 2015Document3 pagesCourses Offered in Spring 2015Mohammed Afzal AsifNo ratings yet

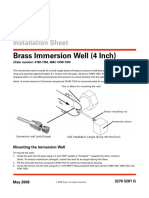

- Brass Immersion Well (4 Inch) : Installation SheetDocument2 pagesBrass Immersion Well (4 Inch) : Installation SheetKim Nicolas SaikiNo ratings yet

- TCM FD20-25Document579 pagesTCM FD20-25Socma Reachstackers100% (2)

- New NCERTDocument3 pagesNew NCERTajmalhusain1082007No ratings yet

- Staff Perception of Respect For Human Rights of Users and Organizational Well-Being: A Study in Four Different Countries of The Mediterranean AreaDocument7 pagesStaff Perception of Respect For Human Rights of Users and Organizational Well-Being: A Study in Four Different Countries of The Mediterranean Areakhouloud razkiNo ratings yet

- MontecarloDocument44 pagesMontecarloAnand Krishna GhattyNo ratings yet

- How To Disassemble Dell Inspiron 17R N7110 - Inside My LaptopDocument17 pagesHow To Disassemble Dell Inspiron 17R N7110 - Inside My LaptopAleksandar AntonijevicNo ratings yet