Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Teichman 1982

Uploaded by

Federico AbalOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Teichman 1982

Uploaded by

Federico AbalCopyright:

Available Formats

Pacifism

JENNY TEICHMAN N e w Hull, Cambridge

The main thesis of this paper is that pacifism is not an incoherent

doctrine; contra the arguments of several comtemporary philosophers.

It seems to me that contemporary philosophers generally give pacifism a

pretty raw deal. I have in mind especially the following: M r Barrie

Paskins, Professor Jan Narveson and Professor Anscombe. The usual

move is to first misdescribe pacifism and then to attack the straw

man.

Anti-pacifist philosophers persistently confuse opposition to war

with opposition to violence as such. Secondly they foist on pacifists

the idea that war (or violence) is wrong eo ips0 and/or by defintion:

wrong eo ips0 being then sometimes confused with wrong by defini-

tion. Thirdly they assume that pacifism can be defined or described

without making any reference to what actual pacifists and con-

scientious objectors have said and without making any reference to

the religious and other principles held by pacifists. It is thus suggested

that pacifism need not be concerned with principles.

In what follows I am going to argue that pacifism is a doctrine

based on ethical and religious principles. Most pacifists in the West

believe that there is a connection between pacifism and Christianity

and even atheistic pacifists are inclined to quote the New Testament

in support of their pacifism. I am also going to argue that pacifism as

such is not opposition to violence as such. A pacifist may or may not

be opposed to violence as such. A pacifist is one who believes that,

whether or not some violence is justified in some circumstances, war

is a kind of violence not justified in any circumstances. Finally it will

be argued that pacifism as such is not the doctrine that war is wrong

by definition, as a matter of logic or even per se. Generally speaking

pacifists treat the proposition war is evil as a substantive proposition,

not as a proposition whose denial would be self-contradictory. It is

possible that anti-pacifist philosophers have slithered from the state-

Jenny Teichman 73

ment A pacifist is, by definition, one who thinks all war is wrong to

the statement A pacifist is one who thinks that all war is wrong by

definition.

Paskins’ description of pacifism runs as follows:

A person is a pacifist if they have beliefs such that, if they acted in the

way those beliefs require, they would refuse all participation in war. . .

Very many sorts of pacifism have something to do with beliefs that the

pacifist has about war or about vio1ence.l

This definition or description succeeds in being simultaneously too

cagey and too broad. It is too broad because it covers the coward

(whose belief that war is dangerous may well require him to refuse

participation), and the aged man who believes his presence and

participation will hinder his comrades in arms; in short it covers

everyone, principled or not, whose beliefs are consistent with refusal

to fight. But a pacifist properly so called is one whose refusal is based

on a moral or religious or political principle, not on any old belief.

Jan Narveson’s account of pacifism runs:

A pacifist believes that violence is evil . . . and that it is wrong to resist,

punish or prevent violence. . . to hold the pacifist position., .is to hold

that no-one has a right to fight back when attacked. . . it means we

have no right to punish criminals, that all our machinery of criminal

justice. . . is unjust.*

Narveson adds that ‘there are many doctrines’ which have been

called pacifism but he thinks that the one described is ‘the only

philosophically interesting kind of pacifism’. The only reason I can

see why Narveson has ignored what has been said and written by real

live pacifists and has insisted that his version is the only interesting

one is that he thinks (wrongly as it happens, but - ) that he can show

that his version is self-contradictory. In other words it is its supposed

vulnerability to attacks by Narveson which makes it so ‘philosophi-

cally interesting’.

Narveson’s definition of pacifism is far too narrow but even his

attack on what is actually a straw man fails to come off.

Narveson’s argument against pacifism runs as follows:

(a) A pacifist is one who believes that all violence is evil.

‘Barrie Paskins and Michael Dockrill, The Ethics of War, p. 112.

2Jan Narveson, ‘Pacifism: a philosophical analysis’ in War and Morality, ed. R.

Wasserstrom, pp. 63,69.

74 Philosophical Investigations

(b) One’s opposition to evil is measured by ‘the effort one puts forth

against it’.

(c) Since violence is evil no-one has a right to be violent and those to

whom violence is done have a right not to have it done to them.

(d) A right just is a status justifying preventive action.

(e) Preventive action must mean successful preventive action.

(f) Sometimes the only possible successful preventive action may be

violent action.

Narveson concludes: ‘And that is why the pacifist’s position is

self-contradictory’. But Narveson’s pacifist’s position, viz: Violence

is evil and must be opposed but not with further violence, is certainly

not formally self-contradictory. Narveson’s own position -if indeed

it is his own position - viz: No-one has a right to be violent (c) but

some rights just are statuses justifying violent action (d, e, fl, looks

much more dubious. If it doesn’t mean Violence is never justified and

violent preventive action is sometimes justified - a plain contradic-

tion - then what does it mean? However, in fairness to Narveson it

must be said that it isn’t at all clear which of the premises in the above

argument he actually believes to be true.

Narveson seems not to have heard of the principle of cost-

effectiveness, neither is he interested in the distinction between inno-

cent and guilty. It would seem to follow from his premises (d, e, f)

that it is sometimes alright to torture hostages, bomb hospitals, and

institute the death penalty for minor but intractable crime. For if

such activities turn out to be the only successful ways of opposing

certain evils then on his argument a refusal to act would either

involve one in contradiction or be tantamount to a denial that the

evil to be opposed was really evil. But the fact is that the principle of

cost-effectiveness, i.e., the principle that the cure should not be worse

that the disease is, like the distinction between guilty and innocent,

absolutely fundamental to all moral reasoning.

Professor Anscombe’s definition of pacifism is actually two defini-

tions, due to the circumstance that she identifies opposition to war

with opposition to the use of State force without noticing that she has

done so. Thus she writes:

I take the doctrine of pacifism to be that it is eo ips0 wrong to fight in

wars.

Jenny Teichman 75

Two pages later she says:

. . . pacifist doctrine,i.e., condemnation of the use of force by the ruling

authorities. . .3

Anscombe draws the line at direct killing of innocent people so it is

obvious that she must reject Narveson’s idea that it is alright, in

opposing an evil, to do whatever is necessary for success. If the only

way to avoid an evil was to kill some innocent people then according

to Anscombe one would just have to put up with the eviL4 In fact

Professor Anscombe and the pacifist are in agreement on one point,

for they both believe that it is possible and necessary to distinguish

between justified and unjustified methods of opposing evil. It’s just

that they draw the line in different places.

The OED defines pacifism as ‘the doctrine or belief that it is

desirable and possible to settle international disputes by peaceful

means’. This definition seems better than the ones proposed by

Paskins, Narveson and Anscombe. However I will not rely on it in

toto because it seems to me that the best way to find out what

pacifism is is to see what pacifists say they believe. Now of course it is

true that one must start out with an initial rough idea as to what a

pacifist is: but the OED can give us that. And then again it is of course

true that there are different varieties of pacifist, or rather, different

kinds of people who claim the label. For instance, William James,

who argued against war mainly on the grounds that it is expensive,

called himself a pacifist. He is like a man who calls himself a veget-

arian because he doesn’t want to pay the butcher’s bill. At the other

extreme there is Tolstoy who argued against violence as such as well

as against war. In between there are Quakers, Mennonites,

Jehovah’s Witnesses, and those American refuseniks who during the

Vietnam war called themselves just war pacifists, the point of the

label being to imply that the techniques of modern war necessitate

injustice of a grave kind.

What all these pacifists have in common is a belief that war is

wrong, i.e., an avoidable evil. Some also believe that State coercion

of any kind is wrong. Some believe that coercion or violence or any

use of force is always wrong. Some Indian pacifists believe, I under-

stand, that it is wrong to kill animals. Some Buddhist pacifists

believe, I understand, that it is wrong to step on an ant. But it would

’G. E. M. Anscombe, ‘War and murder’ in War and Morality, op. cit., p. 46, p. 48.

4Such as drowning in a pothole the exit from which is blocked by a fat pot-holer.

76 Philosophical Investigations

be intensely silly to suppose that pacifists as such believe that it is

wrong to step on ants. The essence of pacifism is the belief that war is

wrong. This can be seen from examples.

Consider for instance the Mennonites. The Mennonites were

founded in Zurich in 1523 and named after an early member named

Menno Simons. They migrated to America in 1683 to escape

persecution. They have now split into a number of sects, all of which

refuse war service and a minority of which refuse to hold civil office

of any kind. All Mennonites regard themselves as pacifists.

Consider secondly the German Brethren. The Brethren were

founded in 1708 by Alexander Mack in Westphalia in the county of

Wittgenstein and migrated to America in 1719 to escape persecu-

tion. They believe that the Old Testament and the New Testament

are both revelations from God and that the New Testament is ‘a

better law’ in the sense that in cases of apparent conflict you should

rely on the New rather than on the Old. According to the Brethren

the positive teaching of the New Testament is unambiguously

against war. They distinguish between positive teaching (what was

said) and negative teaching (what was not said): positive teaching is

to be found in e.g. the Sermon on the Mount and negative teaching is

exemplified by e.g. what John the Baptist did not say to the soldier,

what Christ did not say to the centurion. The Brethren say that the

State is ordained by God and as far as I can discover they do not

refuse to hold civil office. But they say that the State steps outside its

jurisdiction when it engages in war and so they do refuse military

service. They say quite explicitly that punishment by the State of

lawbreakers within its boundaries is lawful, thus police service is

distinguished from army service.

Consider thirdly the Quakers. The Society of Friends or Quakers

were founded circa 1650 by George Fox in England. They are against

taking oaths but have a thing called the Peace Testimony which runs:

I live in virtue of that life and power which took away the occasion of

all wars.

This is obviously about war and not about State coercion as such.

The Quakers are not against the State as such, in fact in the

seventeenth-century they set up a State of their own; it’s called

Pennsylvania. The Penn Quakers said that the police and the magis-

tracy ‘defend the law under God’ by protecting lives and property:

war, on the other hand, necessarily destroys both lives and property.

Jenny Teichman 77

That is to say, what is true of necessity of war is not true of necessity

of police action and the actions of magistrates.

Mennonites, German Brethren and Quakers all regard themselves

as pacifists and are so regarded by the community at large. In

wartime their young men become conscientious objectors. They

conform to the dictionary definition of pacifism. Surely therefore

they are paradigm cases of pacifists.

If the essence of pacifism is the belief that war is wrong does this

mean that pacifists believe, or have to believe if they are to be

consistent, that war is wrong either in itself or by definition or both?

It seems possible for a Chrisitan pacifist to believe that war used to

be lawful but it is not lawful now. Idolatry is forbidden in both the

Old and the New Testaments and so may be presumed to be wrong

eo @so: polygamy, in contrast, was apparently lawful in Old Testa-

ment times but is not lawful now. It follows that polygamy is either

not wrong eo ips0 or that, though wrong eo ipso, it was lawful in OT

times as a lesser evil than some alternatives. A Christian pacifist

might well consider war to be similar to polygamy rather than to

idolatry in this, i.e., as lawful once but not lawful now. (Tertullian:

‘The Lord in disarming Peter disarmed every s ~ l d i e r . ’ ~

However it seems probable that a Christian pacifist who believes

that war used to be lawful in Old Testament times would also believe

that it was lawful then only qua lesser evil and would thus believe

that war was and is evil in itself. For something that is wrong or evil

in itself may nevertheless be justified in certain extreme circumstances.

If something is wrong eo ips0 that does not mean that it is utzimagin-

able for that something to be justifiable (in certain circumstances)

qua lesser evil. For instance, some people think lying is wrong

because of its usual consequences, others think it is wrong in itself:

the latter are not thereby committed to the opinion that a situation in

which telling a lie would be a lesser evil than some alternative is

unimaginable. Other deeds besides lying are wrong in themselves,

hence it is logically possible that one might one day have to choose

between two deeds each of which is wrong eo ipso.

Sometimes anti-pacifists argue as follows: Not even military men

think that war is actually good. To be a pacifist it is not enough to

share the general belief that war is a bad thing: one must believe that

war is bad or wrong by definition. Otherwise the only difference

5Tertullian, On Idolutq~,ch. XLX.

80 Philosophical Znvestigations

either both are lawful or both are unlawful, morally speaking. But

the actions of the police and the magistracy are obviously morally

lawful, and necessary for civil peace. Therefore war must be lawful

too. Versions of this argument - which goes back at least to St Paul -

can be seen in the articles by Professors Narveson and Anscombe

already referred to.

Some philosophers have said that war is a kind of punishment.

St Augustine for instance justifies punishment as a means of justify-

ing war. Both war and punishment, he says, should be pursued in a

spirit of compassion with the motive of helping and improving the

person being punished. A just authority punishes (or fights) as a

father punishes his child. Augustine saw that this account of the

matter did not fit the death penalty however, so he gives a different

and more proasic justification for that, via reference to the good of

the community.6

Aquinas makes a comparison between internal and external force

and violence as follows:

They use the sword lawfully in defence against internal disturbances

so they lawfully use the sword of war to protect the community from

foreign attacks.'

The learned canonist Alfonso Tostado wrote circa 1430:

Just war is simply a mode of legal execution (i.e., a kind of death

penalty).s

Francisco Vitorio wrote:

Since the Apostle (i.e.,Paul, in Romans 13) says it is lawful for rulers to

use arms against wrong-doers in the community it must therefore be

lawful to use arms against foreign enemies9

Vitorio takes the analogy with punishment seriously; he says that it is

lawful to kill any combatant, including unarmed prisoners of war,

since all combatants are a kind of criminal to be punished. And he

says that a ruler fighting a just war 'has jurisdiction over the enemy as

a proper judge'.

Calvin too says that killing soldiers in war is just like exacting the

death penalty on a criminal.'O

6Augustine,On the Sermon on the Mount.

'Aquinas, Summa Tbeolog., secunda secundae 40.

*AlfonsoTostado, quoted in the Editor's Preface of VITORIO, see note (9).

9 F r a n c i ~Vitorio,

c~ De Indis ettejure belli relectiones II, trans.J. P. Bate, ed. E. Nys.

''Calvin, Christian Institutions Book IV, ch. XX.

Jenny Teichman 81

Against these authorities it can be argued that there are many

differences between the use of civil force inside a State, and warfare.

Neither police action nor judicial process is like military action, and

punishment is not in fact at all like war.

(i) Anti-pacifists arguing that war is just like police action usually

omit to mention that not all police action is alright. The move which

runs ‘If you reject the State’s right to engage in war you have no right

to call on State force to protect you against robbers’ similarly omits

to mention the fact that any right one might have to call in the police

must depend initially on how the police are likely to behave. It is only

in a civilised country that the citizen’s moral right to call in the police

can be taken for granted. If the police force is the Ton Ton Macoute it

would not be right or even sensible to ask for their help; if your local

bobby is in the habit of behaving like certain military men - like the

Crusaders in Jerusalem, or the Black and Tans in Ireland, or the

Russians in Berlin for example - it would not be wise or right to

telephone him to report a missing bicycle.

(ii) In civilised countries punishment is in the first place a matter for

the courts and subsequently a matter for the prison service. It is not a

matter for the police, whose job is to apprehend criminals, not to

punish them. This is one of the reasons why it is possible to insist on

the rule that policemen should use a minimum of force when dealing

with criminals. In warfare proper, as against post-war trials of war

criminals, there is no parallel division of roles; the battlefield is police

beat, courtroom, gaol and execution block all rolled into one.

(iii) In a civilised country it is possible to sue the police. It is not

possible to sue a victorious enemy State.

(iv) In many civilised countries the police are unarmed and it is most

unusual for a policeman to have ever killed anyone.

(v) In civilised countries policemen (and judges) uphold laws to

which they themselves are subject. When armies and kings and

generals engage in warfare they are not upholding laws to which they

themselves are subject: what laws would those be? To uphold the

so-called ‘laws of war’ is not a motive for going to war; and the ‘laws

of war’ are anyway held in such contempt that on the rare occasions

on which some soldier is tried for breaking them the newspapers run

‘man bites dog’ headlines for weeks.

(vi) We take it for granted, in a civilised country, that the actions of

the police (and of judges) are generally effective; we assume that

police activity does in the main protect lives and property, keep the

You might also like

- Pacifism and The Demarcation ProblemDocument26 pagesPacifism and The Demarcation ProblemFederico AbalNo ratings yet

- Lackey 1993Document4 pagesLackey 1993Federico AbalNo ratings yet

- Evaluating The Pacist AlternativeDocument23 pagesEvaluating The Pacist AlternativeamiraculouswishNo ratings yet

- 2010 McIntosh Nonviolence UK Defence Academy WebDocument22 pages2010 McIntosh Nonviolence UK Defence Academy WebarlikNo ratings yet

- Fiala Andrew, Defining PeaceDocument3 pagesFiala Andrew, Defining PeaceAndrea OrzaNo ratings yet

- Cheyney Ryan, Pacifism - From Oxford Handbook On WarDocument18 pagesCheyney Ryan, Pacifism - From Oxford Handbook On WarAuteurphiliaNo ratings yet

- Contingent Pacifism and Contingently Pacifist ConclusionsDocument16 pagesContingent Pacifism and Contingently Pacifist ConclusionsHui UnaNo ratings yet

- Realism and PacifismDocument18 pagesRealism and Pacifismlaurelxu33No ratings yet

- Pacifism Is Opposition To: Anarchist or Libertarian PacifismDocument10 pagesPacifism Is Opposition To: Anarchist or Libertarian PacifismAnatol MorariNo ratings yet

- Peace - Real Power Comes from Love, not Hate: A Book About Pacifism, Non-Violence and Civil DisobedienceFrom EverandPeace - Real Power Comes from Love, not Hate: A Book About Pacifism, Non-Violence and Civil DisobedienceNo ratings yet

- Faith and Violence: Christian Teaching and Christian PracticeFrom EverandFaith and Violence: Christian Teaching and Christian PracticeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (6)

- Cheyney Ryan, Pacifism, Self-Defense, and The Possibility of KillingDocument18 pagesCheyney Ryan, Pacifism, Self-Defense, and The Possibility of KillingAuteurphiliaNo ratings yet

- Violently Peaceful: Tibetan Self-Immolation and The Problem of The Non/Violence BinaryDocument15 pagesViolently Peaceful: Tibetan Self-Immolation and The Problem of The Non/Violence BinaryAtticus Peri JohnstonNo ratings yet

- Nonviolent Action: What Christian Ethics Demands but Most Christians Have Never Really TriedFrom EverandNonviolent Action: What Christian Ethics Demands but Most Christians Have Never Really TriedRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (2)

- War and the Christian Conscience How shall Modern War be Conducted Justly?From EverandWar and the Christian Conscience How shall Modern War be Conducted Justly?No ratings yet

- Syria and the chemical weapons taboo: Exploiting the forbiddenFrom EverandSyria and the chemical weapons taboo: Exploiting the forbiddenNo ratings yet

- Alpert, Avram - Philosophy Against and in Favor of ViolenceDocument23 pagesAlpert, Avram - Philosophy Against and in Favor of Violenceel pamparanaNo ratings yet

- Neitzsche KDocument7 pagesNeitzsche KnoNo ratings yet

- The Gospel Of War, If You Want Peace Prepare For War: From Ambassadors Of Conflict To Messengers Aware Of PeaceFrom EverandThe Gospel Of War, If You Want Peace Prepare For War: From Ambassadors Of Conflict To Messengers Aware Of PeaceNo ratings yet

- The Checklist to End Tyranny: How Dissidents Will Win 21st Century Civil Resistance CampaignsFrom EverandThe Checklist to End Tyranny: How Dissidents Will Win 21st Century Civil Resistance CampaignsNo ratings yet

- Languages of the Unheard: Why Militant Protest is Good for DemocracyFrom EverandLanguages of the Unheard: Why Militant Protest is Good for DemocracyNo ratings yet

- War and Moral Responsibility: A Philosophy and Public Affairs ReaderFrom EverandWar and Moral Responsibility: A Philosophy and Public Affairs ReaderRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (3)

- Beehler 1972Document5 pagesBeehler 1972Federico AbalNo ratings yet

- Soldiers, Self-Defense, and Killing in War: Master of Arts IN PhilosophyDocument64 pagesSoldiers, Self-Defense, and Killing in War: Master of Arts IN PhilosophyChetanya MundachaliNo ratings yet

- Killing in Self-Defense : Jonathan QuongDocument31 pagesKilling in Self-Defense : Jonathan QuongLeandro DiasNo ratings yet

- On Justifying Violence: Inquiry, 24, 21-57Document37 pagesOn Justifying Violence: Inquiry, 24, 21-57Ace RooseveltNo ratings yet

- Staudigl SP19Document27 pagesStaudigl SP19류의근No ratings yet

- Concept PaperDocument2 pagesConcept PaperJanwin AdapNo ratings yet

- A Defense of Christian PacifismDocument25 pagesA Defense of Christian PacifismGebre Menfes KidusNo ratings yet

- War and Massacre - Docx111Document6 pagesWar and Massacre - Docx111Roy Vincent OtienoNo ratings yet

- A Chaplain Volunteers: A Memoir of My Two Years In VietnamFrom EverandA Chaplain Volunteers: A Memoir of My Two Years In VietnamNo ratings yet

- PTX Counter KDocument2 pagesPTX Counter KA Wild SheepleNo ratings yet

- PacifismDocument12 pagesPacifismPetar StuparNo ratings yet

- Western & Chinese Philosophies On War: Part I: EssayDocument5 pagesWestern & Chinese Philosophies On War: Part I: EssayHuyNguyenNo ratings yet

- Nombre: Jean Nicolas Sanchez Mojica Science Progress and Social Justice Universidad Del Rosario 9th Critical CommentaryDocument2 pagesNombre: Jean Nicolas Sanchez Mojica Science Progress and Social Justice Universidad Del Rosario 9th Critical CommentaryNicolas SanchezNo ratings yet

- DebateDocument2 pagesDebateamar singhNo ratings yet

- The Heart of Man: Its Genius for Good and EvilFrom EverandThe Heart of Man: Its Genius for Good and EvilRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (19)

- Killing from the Inside Out: Moral Injury and Just WarFrom EverandKilling from the Inside Out: Moral Injury and Just WarNo ratings yet

- Bodies and Battlefields: Abortion, War, and the Moral Sentiments of SacrificeFrom EverandBodies and Battlefields: Abortion, War, and the Moral Sentiments of SacrificeNo ratings yet

- Survey Article: Repentance Rituals Andrestorative Justice: Ohn Raithwaite Law, Australian National UniversityDocument17 pagesSurvey Article: Repentance Rituals Andrestorative Justice: Ohn Raithwaite Law, Australian National Universityהילה אביאליNo ratings yet

- American Fascists: The Christian Right and the War On AmericaFrom EverandAmerican Fascists: The Christian Right and the War On AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (226)

- The Legitimacy of Violence As A Political ActDocument2 pagesThe Legitimacy of Violence As A Political Actghandi_66No ratings yet

- PacifismDocument2 pagesPacifismAdrianGrigoritaNo ratings yet

- JUSTWARResearch PaperDocument18 pagesJUSTWARResearch PaperGrace SalarNo ratings yet

- The Liability of Ordinary Soldiers For Crimes of AggressionDocument18 pagesThe Liability of Ordinary Soldiers For Crimes of AggressionFederico AbalNo ratings yet

- Baker 2006Document17 pagesBaker 2006Federico AbalNo ratings yet

- Nabulsi 2020Document21 pagesNabulsi 2020Federico AbalNo ratings yet

- Narveson1972 Contra BeehlerDocument5 pagesNarveson1972 Contra BeehlerFederico AbalNo ratings yet

- Wolfendale 2017Document18 pagesWolfendale 2017Federico AbalNo ratings yet

- (Law and Philosophy Vol. 39 Iss. 5) Pattison, James - Opportunity Costs Pacifism (2020) (10.1007 - s10982-020-09390-7) - Libgen - LiDocument32 pages(Law and Philosophy Vol. 39 Iss. 5) Pattison, James - Opportunity Costs Pacifism (2020) (10.1007 - s10982-020-09390-7) - Libgen - LiFederico AbalNo ratings yet

- Against Marriage Dan MollerDocument13 pagesAgainst Marriage Dan MollerFederico AbalNo ratings yet

- Dogget Qué Haría TaurekDocument5 pagesDogget Qué Haría TaurekFederico AbalNo ratings yet

- Lamb 2008Document14 pagesLamb 2008Federico AbalNo ratings yet

- (Mind Association Occasional) Helen Frowe, Gerald Lang - How We Fight - Ethics in War (2014, Oxford University Press)Document241 pages(Mind Association Occasional) Helen Frowe, Gerald Lang - How We Fight - Ethics in War (2014, Oxford University Press)Federico AbalNo ratings yet

- Distant Peers: Abstract: What Is The Nature of Rational Disagreement? A Number of PhilosophersDocument15 pagesDistant Peers: Abstract: What Is The Nature of Rational Disagreement? A Number of PhilosophersFederico AbalNo ratings yet

- Pacifism: William J. HawkDocument12 pagesPacifism: William J. HawkFederico AbalNo ratings yet

- Theory and Bioethics (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy)Document18 pagesTheory and Bioethics (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy)Federico AbalNo ratings yet

- Hirose - A NEW TAUREK PROBLEMDocument4 pagesHirose - A NEW TAUREK PROBLEMFederico AbalNo ratings yet

- Sanders Why The Numbers Should Sometimes CountDocument12 pagesSanders Why The Numbers Should Sometimes CountFederico AbalNo ratings yet

- Political Self-Determination and Wars of National Defense: Massimo RenzoDocument25 pagesPolitical Self-Determination and Wars of National Defense: Massimo RenzoFederico AbalNo ratings yet

- Dogget Salvando A Los MenosDocument27 pagesDogget Salvando A Los MenosFederico AbalNo ratings yet

- Je Cker 2013Document14 pagesJe Cker 2013Federico AbalNo ratings yet

- Good Practices Guide 2019Document95 pagesGood Practices Guide 2019Federico AbalNo ratings yet

- R3 (7 - 6) - Dougherty, Why Does Duress Undermine ConsentDocument17 pagesR3 (7 - 6) - Dougherty, Why Does Duress Undermine ConsentFederico AbalNo ratings yet

- How To Argue With An Anti-Utilitarian, by R. M. HareDocument2 pagesHow To Argue With An Anti-Utilitarian, by R. M. HareFederico AbalNo ratings yet

- Transitivity, Moral Latitude, and Supererogation: Arizona State UniversityDocument13 pagesTransitivity, Moral Latitude, and Supererogation: Arizona State UniversityFederico AbalNo ratings yet

- Is Age SpecialDocument14 pagesIs Age SpecialFederico AbalNo ratings yet

- T P M A:: HE Ossibility of Oral BsolutesDocument15 pagesT P M A:: HE Ossibility of Oral BsolutesFederico AbalNo ratings yet

- Kasper Lippert-Rasmussen-Born Free and Equal - A Philosophical Inquiry Into The Nature of Discrimination-Oxford University Press (2013)Document330 pagesKasper Lippert-Rasmussen-Born Free and Equal - A Philosophical Inquiry Into The Nature of Discrimination-Oxford University Press (2013)Federico AbalNo ratings yet

- The Limited Relevance of Analytical Ethics To The Problems of BioethicsDocument17 pagesThe Limited Relevance of Analytical Ethics To The Problems of BioethicsFederico AbalNo ratings yet

- Practice: Writing Philosophy Is Like Anything Else That's Worth Doing: Singing, Dancing, Playing ADocument8 pagesPractice: Writing Philosophy Is Like Anything Else That's Worth Doing: Singing, Dancing, Playing AFederico AbalNo ratings yet

- Godly Rule Politics and Religion 1603 60 PDFDocument200 pagesGodly Rule Politics and Religion 1603 60 PDFh3ftyNo ratings yet

- Operational ResearchDocument16 pagesOperational Research123123azxcNo ratings yet

- Ellerby 2016Document16 pagesEllerby 2016Hannah Louise DimayugaNo ratings yet

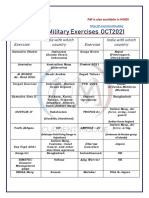

- Military Exercise Upto OctoberDocument2 pagesMilitary Exercise Upto OctoberYashwant Singh RathoreNo ratings yet

- Wartime Expansion of The Nitrogen IndustryDocument40 pagesWartime Expansion of The Nitrogen IndustryMahamud Hasan PrinceNo ratings yet

- CertificateDocument8 pagesCertificateMelody OrpiadaNo ratings yet

- Cross-Border Terrorism: Why in News?Document4 pagesCross-Border Terrorism: Why in News?Surya S PNo ratings yet

- The Twilight StruggleDocument328 pagesThe Twilight StruggleMarcelino DecenaNo ratings yet

- Missile 2003Document21 pagesMissile 2003pulkit nagpalNo ratings yet

- The Operational Art - Developments in The Theories of War PDFDocument231 pagesThe Operational Art - Developments in The Theories of War PDFDat100% (4)

- Rationalization - 3rd Periodical Exam SS8Document67 pagesRationalization - 3rd Periodical Exam SS8Venus Christine VillorejoNo ratings yet

- Philippine Literature: Pre-Spanish Period - OralDocument20 pagesPhilippine Literature: Pre-Spanish Period - OralChynna Ulep AlbertNo ratings yet

- Clea Koff Forensic AnthropologistDocument3 pagesClea Koff Forensic AnthropologistSydney MacekNo ratings yet

- Bangladeshi Courier Service Agent DatabaseDocument4 pagesBangladeshi Courier Service Agent DatabaseTarek Bin OmarNo ratings yet

- 09kruger 52 Cal Leap AheadDocument19 pages09kruger 52 Cal Leap AheadAbhishek GuptaNo ratings yet

- Communist RussiaDocument122 pagesCommunist RussiaManny B. Victor VIIINo ratings yet

- Vintage Airplane - Aug 1976Document20 pagesVintage Airplane - Aug 1976Aviation/Space History LibraryNo ratings yet

- Instant Download Multivariable Calculus 11th Edition Larson Solutions Manual PDF Full ChapterDocument32 pagesInstant Download Multivariable Calculus 11th Edition Larson Solutions Manual PDF Full Chaptersterlinghungo45100% (6)

- Blue Shark Vodka Names Retired Rear Admiral Mark Milliken As CEODocument2 pagesBlue Shark Vodka Names Retired Rear Admiral Mark Milliken As CEOPR.comNo ratings yet

- RPG - sw.DS.2.Strike Force ShantipoleDocument39 pagesRPG - sw.DS.2.Strike Force ShantipoleChristopher FergusonNo ratings yet

- ENG 49-Istoria Na BulgariaDocument34 pagesENG 49-Istoria Na BulgariaJerik SolasNo ratings yet

- The Star News October 9 2014Document39 pagesThe Star News October 9 2014The Star NewsNo ratings yet

- Biography of H.E. Mr. Bui Quang Huy - First Secretary of The HCYU Central CommitteeDocument2 pagesBiography of H.E. Mr. Bui Quang Huy - First Secretary of The HCYU Central CommitteeNicolás SabuncuyanNo ratings yet

- DBSADocument2 pagesDBSAChristopher CaleNo ratings yet

- CSS-2021 English Précis and Composition Solved Paper by Expert ProfessorsDocument8 pagesCSS-2021 English Précis and Composition Solved Paper by Expert Professorsshaheed ullah khiljee0% (1)

- History of The Phillips Curve - GordonDocument42 pagesHistory of The Phillips Curve - GordonstefgerosaNo ratings yet

- Bi SC 75 3 - FinalDocument277 pagesBi SC 75 3 - FinalHenry ArnoldNo ratings yet

- Diocesan Boys' School English Literature Society Newsletter - LitteraturaDocument15 pagesDiocesan Boys' School English Literature Society Newsletter - LitteraturaJustin Chor Yu Liu100% (1)

- Women at WarDocument9 pagesWomen at WarArina PredaNo ratings yet

- Belzec - The 'Forgotten' Death CampDocument15 pagesBelzec - The 'Forgotten' Death CampAnonymous 6KZl2KwNo ratings yet