Professional Documents

Culture Documents

TiCS CellPress

TiCS CellPress

Uploaded by

firman ardiyansyahOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

TiCS CellPress

TiCS CellPress

Uploaded by

firman ardiyansyahCopyright:

Available Formats

TICS 2137 No.

of Pages 4

Trends in

Cognitive Sciences

Forum

over decisions and their outcomes. Forcing unrelated to the influences exerted by the

Mind Control Tricks: techniques are frequently discussed in the magician [7,9].

Magicians’ Forcing and magic literature, but magicians do not

Free Will offer a universally accepted definition. We Decision Forces

define a force as a technique that covertly Decision forces are techniques in which

Alice Pailhès 1,* and Gustav Kuhn 1 influences a person’s choice without their the magician directly manipulates the per-

awareness (here, we use ‘choice’ as an son’s decisions. These techniques allow

umbrella term comprising the spectator’s the magicians to enhance the probabilities

decision as well as the outcome of that that the target card or item is selected, but

A new research program has re-

decision). they typically do not guarantee its choice.

cently emerged that investigates

For instance, the visual riffle force (Box 1)

magicians’ mind control tricks, also

Illusory Agency and Freedom in has a success rate that ranges between

called forces. This research high- Forcing 30 and 98%, depending on whether the

lights the psychological processes As we have argued elsewhere [2], a suc- performance was live or computer-based

that underpin decision-making, illus- cessful force has two key components. [7,8]. Empirical research on the position

trates the ease by which our deci- Firstly, the force has to significantly affect force shows that around 60% of participants

sions can be covertly influenced, the spectator’s decision or the outcome end up with the target card when we would

and helps answer questions about of their choice. Secondly, the spectator expect 25% by chance [4,6]. In these tech-

our sense of free will and agency has to feel free in their choice and in control niques, the magician uses psychological

over choices. of the outcome they get. When successful, tricks and biases to influence the spectator’s

the force results in an illusory feeling of decisions. People tend to choose a ‘path of

freedom of choice and/or agency over least resistance’: the chosen item is often

We like to think that we are in charge the outcome (e.g., the card they chose). the one that involves the least amount of

of our decisions, but psychological re- As we will see later, some forces exploit effort; this is associated with heuristic/

search shows that many of our behaviours psychological biases and restrictions to system 1 type of behaviour. Most of the

are unconsciously influenced by external influence the spectator’s decision, while decision forces that have been investigated

stimuli and that we are often oblivious others do not. In the first case, the specta- to date rely on exploiting psychological

to the cognitive mechanisms that under- tor’s freedom of choice is undermined as it biases (Box 1): priming, stereotypical

pin the choices we make. Magicians is constrained by external factors imposed behaviours, and visual saliency.

have exploited this illusory sense of by the magician. In the latter, the spectator

agency for a long time and they have makes a completely free decision, which Outcome Forces

developed a wide range of techniques has no impact on the outcome. In both In outcome forces, the spectator has, and

to influence and control their spectators’ cases, spectators typically fail to realize makes a genuinely free decision, but

choices of such things as cards, words, that their decision was manipulated or unknown to them this decision has no

or numbers. These techniques are called that it had no impact on the outcome [3]. impact on the outcome of the trick. Most

forces. Video examples of the techniques can be forcing techniques fall into this category,

found at https://www.magicresearchlab. as they guarantee that the spectator will

The past decade has seen a sharp rise in com/forcing-taxonomy-material. end up with the forced item [11]. Here, a

scientific research on the science of key principle relies on the spectator not

magic and researchers have investigated Forcing techniques provide powerful tools understanding that their choice cannot

diverse cognitive processes such as per- to investigate illusory sense of agency and affect the outcome of the procedure.

ception, attention, problem solving, or freedom over choices. Empirical research These techniques provide a particularly

belief formation [1]. More recently, the using magicians’ forces indeed shows useful tool to investigate illusory sense of

focus has shifted towards understanding that participants report high feelings of agency over the outcome of our actions.

how magicians control our choices. Magi- freedom and control over their choice, Many outcome forces rely on the fact that

cians have developed a wide range of even though they ended up with the the chosen item is covertly switched by

psychological tricks to covertly influence predetermined target card or object the magician for the target/predetermined

people’s choices [2]. These forces are [4–10]. Moreover, when asked to explain one. This kind of technique has been used

often extremely effective and illustrate the reason for their choice, most partici- in choice blindness paradigms, in which

various weaknesses in our sense of control pants confabulated reasons that were people fail to notice the mismatch between

Trends in Cognitive Sciences, Month 2021, Vol. xx, No. xx 1

Trends in Cognitive Sciences

Box 1. Decision Forces

Visual Riffle Force

In the visual riffle force [7,8] visual saliency and/or restrictions are used to influence the spectator to mentally choose a playing card. The magician flips through a deck of

cards and asks the spectator to visually select one of them. However, unbeknownst to the spectator, the target card is shown slightly longer than the others and

becomes more visually salient. Two scientific papers have investigated this force and shown that in a live context, between 54 and 98% of participants choose the target

card, while feeling completely free for their choice.

Position Force

The position force relies on a physical/motor stereotypical behaviour [4,6]: most people tend to act in the same way when presented with a specific situation. In this

technique, the conjurer places four cards in a horizontal row on a table and asks the spectator to touch or take one. As most people are right-handed and tend to choose

items that are more reachable, the majority will choose the third card form their left. Two scientific papers have investigated this force: on average 60% of people choose

the target card. Moreover, participants are oblivious to this bias, as they significantly underestimated the percentage of people who would also select this card.

Interestingly, the percentage of people who impulsively chose the most reachable card dropped from 60 to 35% when participants were explicitly reminded that they

were making a decision [6].

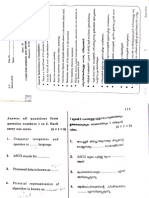

Mental Priming Force

The mental priming force relies on subtle priming mechanisms (Figure I). Here, the magician uses both verbal and nonverbal primes, to prime the spectator to name the

target object. The mental priming force, created by British mentalist Derren Brown, relies on using subtle hand gestures and key words to prime people to think of the

three of diamonds [9]. In this force, the magician declares that they will try to mentally transmit the identity of a playing card and then asks them to follow some instruc-

tions while imagining different things. For instance, the magician gestures a diamond shape while asking participants to imagine a screen in their mind, or quickly draws

little threes in the air while asking them to imagine the numbers on the card. This force has been shown to be effective for 18% of participants, when we would expect less

than 2% by chance [9].

Figure I. The Mental Priming Force.

The magician primes the spectator to think

about the three of diamonds. (A) Hands

picture a diamond shape, (B) finger draws

the number three, (C) three fingers are

pointed, and (D) three different places are

pointed.

Trends in Cognitive Sciences

their choice and the outcome of this misunderstand the event sequence. To Wider Implications

choice [12]. Other outcome forces rely date, two outcome forces have been Studying forcing techniques can help us

on the spectator’s memory or reasoning scientifically studied: the criss-cross force understand the cognitive mechanisms that

errors, leading them to misremember or and the equivoque force (Box 2). underpin decision making, the external

2 Trends in Cognitive Sciences, Month 2021, Vol. xx, No. xx

Trends in Cognitive Sciences

Box 2. Outcome Forces

The Criss-Cross Force

The criss-cross force consists of asking a spectator to cut a deck of cards and place the top pile next to the bottom one, after which the magician takes the bottom pile

and places it on the top one in a crossed figure (Figure I). The magician then asks the spectator a question to draw their attention away from the deck and create a time

delay. The conjurer then raises the top pile of the cross and asks the audience member to take the top card of the bottom pile (the top card of the original deck). This

technique has been shown to be extremely effective and the vast majority of participants fail to understand that their action of cutting the deck had no impact on their

outcome card and believe that they were in control of it [5].

The Equivoque

The equivoque, also called the Magician’s force, is considered to be one of the most powerful forcing techniques a magician can use. This technique relies on ambiguity

blindness (the failure to recognize ambiguous situations) to create an illusion of choice [2]. For this, the magician deals two objects on a table, such as a key and a wallet. They

then ask the spectator to touch one of them. If the conjurer wants the person to end up with the key and the spectator touches it, the magician keeps it and discards the wallet.

But if the spectator touches the wallet rather than the key, the magician simply discards this choice and keeps the key anyway. Regardless of the spectator’s choice, the

sequences result in the same outcome. The equivoque is highly effective in providing an illusory sense of control over the outcome of participants’ actions [10]. Participants

fail to understand that their action, touching one object, could be interpreted in different ways and are oblivious to the semantic inconsistencies in the procedure.

Figure I. The Criss-Cross Force. The

spectator ends up with the forced card

(card A), which he/she believes to be the

other card, selected by the cut (card B).

Trends in Cognitive Sciences

factors (e.g., visual saliency, position ef- and in situations in which there are lots of mechanisms [13]. Some theories put the

fects, priming) that guide our choices, choice alternatives. Many of these principles emphasis on processes that precede

and what makes us believe that we are have been thoroughly tested in the real the execution of one’s action (i.e., the expe-

in control of our actions. These tech- world (i.e., magic performances), but they rience of agency arises from internal predic-

niques provide an opportunity to help can be easily implemented in more con- tion about the sensory consequences of

understand what makes one action feel trolled laboratory experiments that allow us one’s actions). Others stress the importance

‘freer’ than another, as few studies have to examine the cognitive factors that result of processes succeeding one’s action

investigated this subjective experience. in illusory feelings of freedom and agency (e.g., the experience of agency is a product

Most of the past research on free will over our behaviour and thoughts. of our post-hoc inference after the action

and agency has focused on simple physi- has occurred). Decision forces are success-

cal actions (e.g., when to press a button). Magicians’ forces also relate to the broader ful because the spectator does not have

The study of forcing allows us to examine issue of agency, for which there is a distinc- direct access to the cognitive processes

these questions in more natural contexts tion between predictive and postdictive preceding their decision (e.g., priming

Trends in Cognitive Sciences, Month 2021, Vol. xx, No. xx 3

Trends in Cognitive Sciences

mechanisms, or thoughts activated by the domains outside the magic performance. *Correspondence:

apail001@gold.ac.uk (A. Pailhès).

visual saliency of a card). In this case, the Nudging people’s behaviours has become

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2021.02.001

spectators often confabulate reasons for an increasingly popular way of modifying

© 2021 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

their choice, which have nothing to do behaviour. Most forcing principles have

with the forcing technique. Outcome forces been tested in the real world and thus offer

References

take advantage of the fact that spectators powerful tools to influence people’s choices. 1. Rensink, R.A. and Kuhn, G. (2015) A framework for using

cannot predict the outcome of their choice This might provide new ways of en- magic to study the mind. Front. Psychol. 5, 1508

2. Pailhès, A. et al. (2020) A psychologically based taxonomy of

(e.g., choosing a card when it is face down couraging better decisions regarding health magicians’ forcing techniques. Conscious. Cogn. 86, 103038

or touching a card without knowing and well-being (e.g., visual saliency, place- 3. Kuhn, G. (2019) Experiencing the Impossible: The Science

of Magic, MIT Press

whether it will be kept or discarded). ment of items). Forcing techniques could 4. Kuhn, G. et al. (2020) Forcing you to experience wonder:

Because of this, they fail to understand also be implemented in the entertainment unconsciously biasing people’s choice through strategic

physical positioning. Conscious. Cogn. 80, 102902

that they had no agency on the outcome industry, by creating a false sense of choice 5. Pailhès, A. and Kuhn, G. (2020) The apparent action causation:

result. As it has been noted, an interplay and autonomy, which helps create more using a magician forcing technique to investigate our

illusory sense of agency over the outcome of our choices.

between prediction and postdiction seems engaging and interactive experiences. Q. J. Exp. Psychol. (Hove) 73, 1784–1795

to exist in the experience of agency and Similar principles could be implemented in 6. Pailhès, A. and Kuhn, G. (2020) Subtly encouraging more

deliberate decisions: using a forcing technique and popu-

the context of forcing in magic purposefully other interactive media such as TV shows lation stereotype to investigate free will. Psychol. Res.

downplays the role of predictive processes or theatre. Finally, the covert control and Published online May 14, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1007/

s00426-020-01350-z

on the spectator’s sense of agency. modification of people’s thoughts does 7. Olson, J.A. et al. (2015) Influencing choice without

raise serious ethical issues. Magicians are awareness. Conscious. Cogn. 37, 225–236

8. Shalom, D.E. et al. (2013) Choosing in freedom or forced to

Importantly, decision forces simply enhance not alone in using such techniques and we choose? Introspective blindness to psychological forcing in

the probability that a spectator will choose believe that magicians’ forcing techniques stage-magic. PLoS One 8, e58254

9. Pailhès, A. and Kuhn, G. (2020) Influencing choices with

one alternative over the other and it is possi- provide a valuable tool to raise awareness conversational primes: how a magic trick unconsciously

ble that some people are more strongly about the ease by which our choices influences card choices. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A.

117, 17675–17679

affected by these techniques than others. can be manipulated. Such awareness may 10. Pailhès, A. et al. (2020) The magician’s choice: providing illu-

The magic literature often emphasizes that help protect people against unwanted sory choice and sense of agency with the equivoque forcing

technique. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. Published online November

the performer should select ‘responsive influences (e.g., political propaganda) and 30, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1037/xge0000929

spectator’ and that external factors might encourage policy makers to take the issue 11. Cole, G.G. (2020) Forcing the issue: little psychological

influence in a magician’s paradigm. Conscious. Cogn.

impact the success rate of such technique. seriously. 84, 103002

These parameters seem worth exploring in 12. Rieznik, A. et al. (2017) A massive experiment on choice

blindness in political decisions: confidence, confabulation,

the future (e.g., needs for cognition, locus Declaration of Interests and unconscious detection of self-deception. PLoS One

of control, hypnotic suggestibility). No interests are declared. 12, 1–16

13. Synofzik, M. et al. (2013) The experience of agency: an interplay

between prediction and postdiction. Front. Psychol. 4, 127

Many of the psychological principles that 1

Psychology Department, Goldsmiths, University of London,

underpin these forces can be applied to London, UK

4 Trends in Cognitive Sciences, Month 2021, Vol. xx, No. xx

You might also like

- Visualizing and Forecasting Stocks: Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of The Requirement of For The Degree ofDocument31 pagesVisualizing and Forecasting Stocks: Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of The Requirement of For The Degree ofAinul AlamNo ratings yet

- Modern CryptographyDocument6 pagesModern Cryptographyprakash kumar katwal0% (1)

- Science Webquest 2Document3 pagesScience Webquest 2Maleah GossaiNo ratings yet

- CCI 06 Comm ADocument338 pagesCCI 06 Comm AVictor AmarandiNo ratings yet

- Potato Squad New Trader Welcome Sheet.: Never Ever Use More Than You Are Willing To LoseDocument11 pagesPotato Squad New Trader Welcome Sheet.: Never Ever Use More Than You Are Willing To LosehakimdopeNo ratings yet

- Research Paper 1 1Document16 pagesResearch Paper 1 1api-483994460No ratings yet

- CIA Structured-Analytic-Techniques PDFDocument45 pagesCIA Structured-Analytic-Techniques PDFashbhatia02No ratings yet

- A Psychologically Based Taxonomy of MagiDocument33 pagesA Psychologically Based Taxonomy of MagicuriosityNo ratings yet

- How Get Started NLP 6 Unique Ways Perform TokenizationDocument12 pagesHow Get Started NLP 6 Unique Ways Perform TokenizationHoang PhamNo ratings yet

- Group 3Document13 pagesGroup 3Suman JajooNo ratings yet

- Investigation of Insight With Magic Tricks - Introducing A (PDFDrive)Document117 pagesInvestigation of Insight With Magic Tricks - Introducing A (PDFDrive)Sunny GujjarNo ratings yet

- Data Security Using Variant of Hill CipherDocument9 pagesData Security Using Variant of Hill CipherIJRASETPublicationsNo ratings yet

- Unit No. 01 - Introduction To AI & MLDocument31 pagesUnit No. 01 - Introduction To AI & MLGAME ZONENo ratings yet

- JcsumbladepyramidDocument12 pagesJcsumbladepyramidJhogamNo ratings yet

- Basic Color TheoryDocument5 pagesBasic Color TheoryCEZ NICOLE BAYUNNo ratings yet

- Ey Ficci M and e Report Tuning Into ConsumerDocument374 pagesEy Ficci M and e Report Tuning Into ConsumerSindhu RaghavanNo ratings yet

- UCCU For Multiple Selection (Max T. Oz) : U.C.C.U. Performance IdeasDocument22 pagesUCCU For Multiple Selection (Max T. Oz) : U.C.C.U. Performance IdeasAdrian SalamonNo ratings yet

- Emotional Arousal in 2D Versus 3D Virtual Reality PDFDocument17 pagesEmotional Arousal in 2D Versus 3D Virtual Reality PDFCeciliaIsolaNo ratings yet

- The Illusion of The Perpetual Money MachineDocument30 pagesThe Illusion of The Perpetual Money MachineRodrigo Candido De CarvalhoNo ratings yet

- Television Blindfold Drive!: by Richard OsterlindDocument4 pagesTelevision Blindfold Drive!: by Richard OsterlindmindmystifierNo ratings yet

- Taylor ExperiencingDocument12 pagesTaylor ExperiencingFranco CapuanoNo ratings yet

- Bài tập tự động hóa sản xuất - 0001-0001Document1 pageBài tập tự động hóa sản xuất - 0001-0001Minh NhậtNo ratings yet

- West Africa Fertilizer Recommendations: 2018 EditionDocument48 pagesWest Africa Fertilizer Recommendations: 2018 EditionMadam CashNo ratings yet

- Majd Y. Ibrahim PHD ThesisDocument381 pagesMajd Y. Ibrahim PHD ThesisUn KnownNo ratings yet

- Objectorienteddesignnpatterns Cayhorstmann 2ndDocument475 pagesObjectorienteddesignnpatterns Cayhorstmann 2ndfirozakhatoon SheikNo ratings yet

- STS Final Exam ReviewerDocument26 pagesSTS Final Exam ReviewerAlthea Marie CruzNo ratings yet

- Intelligence and TheoriesDocument13 pagesIntelligence and TheoriesVarnika KatariaNo ratings yet

- Operating System (Algorithms) : Q. Producer - Consumer Problem AnsDocument11 pagesOperating System (Algorithms) : Q. Producer - Consumer Problem Ans;ouhgfNo ratings yet

- Advance Database Management System LAB ETCS - 457Document34 pagesAdvance Database Management System LAB ETCS - 457AayushNo ratings yet

- MentalistDocument434 pagesMentalistAngeline ErcillaNo ratings yet

- How To Effectivelly Build Marketing in The Digital Era EconomiesDocument11 pagesHow To Effectivelly Build Marketing in The Digital Era EconomiesPaul BernardNo ratings yet

- Lesson 2-The Moral ActDocument14 pagesLesson 2-The Moral ActPam MillenasNo ratings yet

- The Mystery of The Mystics and A Scientific Vision Uncovering A New RealityDocument2 pagesThe Mystery of The Mystics and A Scientific Vision Uncovering A New RealityChirag ChhabriaNo ratings yet

- Law of Torts Notes (Part 1) - IPleadersDocument60 pagesLaw of Torts Notes (Part 1) - IPleadersDharmendera BhallaNo ratings yet

- Excel VBA To Interact With Other ApplicationsDocument7 pagesExcel VBA To Interact With Other ApplicationsgirirajNo ratings yet

- The New Epoch - Sample 2Document18 pagesThe New Epoch - Sample 2Jonathan FriedmanNo ratings yet

- Disney PatentDocument12 pagesDisney PatentCharles GrossNo ratings yet

- Short and Long Vowel Sounds - Week 6 - k1Document14 pagesShort and Long Vowel Sounds - Week 6 - k1PAOLA ALEJANDRA RAMIREZ PLATERONo ratings yet

- Information: Knowledge Graphs and Explainable AI in HealthcareDocument11 pagesInformation: Knowledge Graphs and Explainable AI in HealthcareBen AllenNo ratings yet

- 21-22 T1 Intermediate Writing BookletDocument166 pages21-22 T1 Intermediate Writing BookletBeste KahyaNo ratings yet

- Hindustan TimesDocument46 pagesHindustan TimesRavindra Varma PvsNo ratings yet

- QP 2018Document8 pagesQP 2018Ashkar AshrafNo ratings yet

- Deleted PortionDocument3 pagesDeleted PortionSujal Yadav 10 FNo ratings yet

- Waldman, Ward, Becker - 2017 - Neuroscience in Organizational Behavior - SSRN PDFDocument22 pagesWaldman, Ward, Becker - 2017 - Neuroscience in Organizational Behavior - SSRN PDFMarv KHNo ratings yet

- Colecting and Analysing Cunatitive Data, An Hemeneutic, PattersonDocument128 pagesColecting and Analysing Cunatitive Data, An Hemeneutic, PattersonCarlos manuel Romero torradoNo ratings yet

- Creative Test CCC 33Document2 pagesCreative Test CCC 33parth100% (1)

- Cleartrip Flight E-TicketDocument1 pageCleartrip Flight E-TicketpawanNo ratings yet

- Guidelines UGC NETDocument54 pagesGuidelines UGC NETmthiyagarajanNo ratings yet

- RealTimeTableDetails 7.5Document44 pagesRealTimeTableDetails 7.5Alfredo SilveiraNo ratings yet

- TiCS GRODocument12 pagesTiCS GROHina AshishNo ratings yet

- Consciousness and Cognition: Alice Pailh'es, Ronald A. Rensink, Gustav KuhnDocument12 pagesConsciousness and Cognition: Alice Pailh'es, Ronald A. Rensink, Gustav KuhnAleksandar NusicNo ratings yet

- Forcing Techniques and NeuroscienceDocument26 pagesForcing Techniques and NeuroscienceLanchenba ShNo ratings yet

- Tradecraft Primer Structured-Analytic-Techniques PDFDocument45 pagesTradecraft Primer Structured-Analytic-Techniques PDFLucas Beaumont100% (1)

- Structured Analytic Techniques PDFDocument45 pagesStructured Analytic Techniques PDFcbales99100% (1)

- CIA Tradecraft Primer Structured Analytic TechniquesDocument45 pagesCIA Tradecraft Primer Structured Analytic Techniquessmoothoperator30No ratings yet

- Week 3Document13 pagesWeek 3Arishragawendhra NagarajanNo ratings yet

- Minds at Play: Challenging Manipulation and Taking Control: Psychological Manipulation and Mass Control, #1From EverandMinds at Play: Challenging Manipulation and Taking Control: Psychological Manipulation and Mass Control, #1No ratings yet

- TMP 6 A07Document10 pagesTMP 6 A07FrontiersNo ratings yet

- 04 Cia 2009Document45 pages04 Cia 2009armando zasooNo ratings yet

- Heuristics - Nazreen SMDocument6 pagesHeuristics - Nazreen SMNazreen S MNo ratings yet

- Goldstein Et Al. (2008) A Room With A ViewpointDocument11 pagesGoldstein Et Al. (2008) A Room With A ViewpointNatashaNo ratings yet

- Chapter 6. Browsing Strategies: Document Browsing, Since The Information Seeker Browses Across Records or Books To FindDocument29 pagesChapter 6. Browsing Strategies: Document Browsing, Since The Information Seeker Browses Across Records or Books To FindCatalina Echeverri GalloNo ratings yet

- Effects of Goal Specificity On Means-Ends Analysis and LearningDocument12 pagesEffects of Goal Specificity On Means-Ends Analysis and LearningdoaguirreNo ratings yet

- Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics: Article InformationDocument21 pagesAsia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics: Article InformationThifal AzharNo ratings yet

- Group 6 - A CASE STUDY OF HILIFE FOODSDocument16 pagesGroup 6 - A CASE STUDY OF HILIFE FOODSAnjali KhatiwadaNo ratings yet

- Chapter Three: "How To Strike Psychological Paydirt in Biographical Data"Document38 pagesChapter Three: "How To Strike Psychological Paydirt in Biographical Data"Seth BautistaNo ratings yet

- Brand Management Lesson 3Document13 pagesBrand Management Lesson 3Jhagantini PalaniveluNo ratings yet

- CB Attitude and IntentionDocument11 pagesCB Attitude and IntentionCarlNo ratings yet

- Attractivity 2Document17 pagesAttractivity 2Cosmin RusuNo ratings yet

- Brand Resonance and The Brand Value ChainDocument22 pagesBrand Resonance and The Brand Value ChainLalit TankNo ratings yet

- Juror Decision MakingDocument31 pagesJuror Decision Makingapi-542125446No ratings yet

- Samson - An Introduction To Behavioral Economics - BEGuide2014Document12 pagesSamson - An Introduction To Behavioral Economics - BEGuide2014zaghtour achrafNo ratings yet

- Rocio Glez Romero TFMDocument64 pagesRocio Glez Romero TFMaridimeglioNo ratings yet

- Impoliteness: Using Language To Cause Offence: 1. BackgroundDocument11 pagesImpoliteness: Using Language To Cause Offence: 1. BackgroundBrandon WangNo ratings yet

- Editing.... - SCALE FOR RANKING HEALTH CONDITIONS AND PROBLEMS ACCORDING TO PRIORITIESDocument15 pagesEditing.... - SCALE FOR RANKING HEALTH CONDITIONS AND PROBLEMS ACCORDING TO PRIORITIESDonna Mae BoolNo ratings yet

- What Is The Cognitive Neuroscience of ArDocument20 pagesWhat Is The Cognitive Neuroscience of ArMario VillenaNo ratings yet

- 1969 - Lipsky - Toward A Theory of Street Level Bureaucracy PDFDocument51 pages1969 - Lipsky - Toward A Theory of Street Level Bureaucracy PDFMariel MuraroNo ratings yet

- Customer Based Brand Equity Identifying & Establishing Brand Positioning & ValuesDocument54 pagesCustomer Based Brand Equity Identifying & Establishing Brand Positioning & Valuesurandom101No ratings yet

- Community Resilience: Integrating Hazard Management and Community EngagementDocument21 pagesCommunity Resilience: Integrating Hazard Management and Community EngagementJavier Gonzales IwanciwNo ratings yet

- Brand Resonance As A Strategic Marketing ToolDocument35 pagesBrand Resonance As A Strategic Marketing ToolRichard DjayaNo ratings yet

- Late Adolescent and Adulthood Career DevelopmentDocument22 pagesLate Adolescent and Adulthood Career DevelopmentNurhayati Wan MudaNo ratings yet

- Self-Understanding and Self-Extension: A Systems and Representational ApproachDocument23 pagesSelf-Understanding and Self-Extension: A Systems and Representational ApproachFikir JohnNo ratings yet

- AgendaSetting IntlEncyDocument21 pagesAgendaSetting IntlEncyMạnh ĐứcNo ratings yet

- Greenhaus y Beutell (19859Document14 pagesGreenhaus y Beutell (19859Diana AlvaradoNo ratings yet

- Enhancing Destination Image On Tourism Brochure of Barru Regency Sulawesi Selatan, Indonesia: A Tourism Discourse PerspectiveDocument12 pagesEnhancing Destination Image On Tourism Brochure of Barru Regency Sulawesi Selatan, Indonesia: A Tourism Discourse PerspectiveMegi VisiNo ratings yet

- BDM-Chapter 3Document41 pagesBDM-Chapter 3J83MEGHA DASNo ratings yet

- Nationalism ScaleDocument15 pagesNationalism ScaleMihai Rusu0% (1)

- Research Profile FormatDocument15 pagesResearch Profile Formatpritish chadhaNo ratings yet

- Brand Resonance and The Brand Value ChainDocument12 pagesBrand Resonance and The Brand Value ChainAshrafulNo ratings yet

- Brand Resonance and Brand ValueDocument46 pagesBrand Resonance and Brand ValueKassandra Kay De RoxasNo ratings yet