Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Is This Patient Having A Myocardial Infarction

Uploaded by

ALVARO LUCIO JIBAJA DEZAOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Is This Patient Having A Myocardial Infarction

Uploaded by

ALVARO LUCIO JIBAJA DEZACopyright:

Available Formats

The Rational Clinical Examination

Is This Patient Having

a Myocardial Infarction?

Akbar A. Panju, MBChB, FRCPC; Brenda R. Hemmelgarn, PhD, MD;

Gordon H. Guyatt, MD, MSc, FRCPC; David L. Simel, MD, MHS

When faced with a patient with acute chest pain, clinicians must distinguish ment of patients with symptoms sugges-

myocardial infarction (MI) from all other causes of acute chest pain. If MI is sus- tive of acute MI. These include evalua-

pected, current therapeutic practice includes deciding whether to administer tion of time-dependent changes in car-

thrombolysis or primary percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty and diac enzymes including creatine kinase,

whether to admit patients to a coronary care unit. The former decision is based creatine kinase isoenzyme, and, more re-

cently, myoglobin and troponin, as well as

on electrocardiographic (ECG) changes, including ST-segment elevation or left an assessment of wall-motion abnormal-

bundle-branch block, the latter on the likelihood of the patient’s having unstable ity using echocardiography, radionuclide

high-risk ischemia or MI without ECG changes. Despite advances in investiga- angiography, or nuclear imaging.

tive modalities, a focused history and physical examination followed by an ECG Despite this progress, a carefully con-

remain the key tools for the diagnosis of MI. The most powerful features that in- ducted history and a physical examina-

crease the probability of MI, and their associated likelihood ratios (LRs), are new tion remain the first component, and the

ST-segment elevation (LR range, 5.7-53.9); new Q wave (LR range, 5.3-24.8); cornerstone, in the initial assessment of

chest pain radiating to both the left and right arm simultaneously (LR, 7.1); patients presenting with suspected MI.

presence of a third heart sound (LR, 3.2); and hypotension (LR, 3.1). The most The history and physical examination are

powerful features that decrease the probability of MI are a normal ECG result critical in guiding the selection of further

diagnostic and therapeutic interventions.

(LR range, 0.1-0.3), pleuritic chest pain (LR, 0.2), chest pain reproduced by Clinicians complement their clinical ex-

palpation (LR range, 0.2-0.4), sharp or stabbing chest pain (LR, 0.3), and po- amination with a 12-lead ECG and car-

sitional chest pain (LR, 0.3). Computer-derived algorithms that depend on clini- diac enzymes, which are additional data

cal examination and ECG findings might improve the classification of patients that provide the most definitive diagno-

according to the probability that an MI is causing their chest pain. sis of MI. We will focus on features of his-

JAMA. 1998;280:1256-1263 tory, physical examination, and ECG that

aid in increasing or decreasing the likeli-

CLINICAL SCENARIOS fort started 30 minutes ago and was as- hood of acute MI. We include the ECG in

sociated with diaphoresis. His blood pres- our review because the clinician often in-

Are These Patients Having

sure is 90/60 mm Hg, his heart rate is 50/ terprets the results at the patient’s bed-

a Myocardial Infarction?

min, and the ECG reveals Q waves in V1 side as part of a prompt initial clinical

Case 1.—A 57-year-old man presents to V4 (present in the old ECG). evaluation.

to the emergency department (ED) with For the purpose of clarification, we be-

Case 3.—A 50-year-old woman pre-

squeezing retrosternal pain that started gin by describing the 3 diagnostic group-

sents to the ED with retrosternal burn-

1 hour ago. He is diaphoretic. His blood ings of patients with acute chest pain cur-

ing of 1 hour’s duration and nausea. Ant-

pressure is 110/70 mm Hg, his heart rate rently used by clinicians and then we con-

acids provided no relief. The findings of

is 74/min, and he has an audible fourth trast these with the categorization of

the clinical examination were unremark-

heart sound. The electrocardiogram chest pain as presence or absence of MI,

able. The ECG reveals 3-mm ST-seg-

(ECG) reveals 2-mm ST-segment eleva- as is evident in the literature. We then

ment elevation in leads II, III, and aVF

tion in leads V1 to V4. briefly describe signs and symptoms of

and 1-mm ST-segment depression in I

Case 2.—A 70-year-old man, with a his- MI, mechanisms of chest pain, and condi-

and aVL.

tory of myocardial infarction (MI) 5 years tions that may present with symptoms

Case 4.—A 40-year-old woman pre-

previously, presents to the ED with se- suggestive of MI. Following these intro-

sents to the ED with a 24-hour history of

vere tightness in the neck. The discom- ductory topics, a detailed account of the

left-sided chest pain. The pain is wors-

ened by exertion and movement. Prior precision and accuracy of the history,

history is unremarkable. Examination physical examination, and ECG in the di-

From the Departments of Medicine (Drs Panju and reveals normal vital signs and tender- agnosis of MI is provided. Having pre-

Guyatt), Clinical Epidemiology and Biostatistics (Dr

ness with palpation of the left lower cos- sented multiple clinical examination

Guyatt), and McMaster Medical Programme (Dr Hem-

melgarn), McMaster University, Hamilton, Ontario; and tal cartilages. The ECG result is normal. items and their associated likelihood ra-

the Center for Health Services Research in Primary tios (LRs), we conclude by noting the

Care, Durham Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Duke

University Medical Center, Durham, NC (Dr Simel). Dr Why Is This an Important Question

Hemmelgarn is currently a resident in internal medicine

at the University of Calgary, Alberta. to Answer With a The Rational Clinical Examination section editors:

Reprints: Akbar A. Panju, MBChB, FRCPC, McMas- Clinical Examination? David L. Simel, MD, MHS, Durham Veterans Affairs

ter University Medical Centre, 1200 Main St W, Room Medical Center and Duke University Medical Center,

3X28, Hamilton, Ontario, Canada L8N 3Z5 (e-mail: There have been numerous technologi- Durham, NC; Drummond Rennie, MD, Deputy Editor

panjuaa@fhs.csu.mcmaster.ca). cal advancements made in the assess- (West), JAMA.

1256 JAMA, October 14, 1998—Vol 280, No. 14 A Question of Myocardial Infarction—Panju et al

©1998 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: http://jama.jamanetwork.com/ by a University of St. Andrews Library User on 05/26/2015

Table 1.—Grading of Angina of Effort by the

Canadian Cardiovascular Society Chest Pain

Grade Description

I “Ordinary physical activity does not Group A Group B Group C

cause angina,” such as walking or Myocardial Infarction With Myocardial Infarction Without Unstable Angina–Low Risk

climbing stairs. Angina with strenuous ST-Segment Elevation or ST-Segment Elevation or Nonischemic Pain

or rapid or prolonged exertion at work Left Bundle-Branch Block Left Bundle-Branch Block

or recreation.

II “Slight limitation of ordinary activity.” Unstable Angina–High Risk

Walking or climbing stairs rapidly,

walking uphill, or walking or stair Strategy: Thrombolysis, Strategy: Admit to Coronary Strategy: Admit to Intermediate

climbing after meals, in cold, in wind, Coronary Angioplasty Care Unit Care Setting Ward Bed

or under emotional stress, or only and Further Testing or

during the few hours after awakening. Discharge Home With

Walking more than 2 blocks on the

level and climbing more than 1 flight of

Plans for Further Testing

ordinary stairs at a normal pace and in

normal conditions.

III “Marked limitation of ordinary physical Figure 1.—Diagnostic groupings of acute chest pain based on management strategies.

activity.” Walking 1 or 2 blocks on the

level and climbing 1 flight of stairs in

normal conditions and at a normal

pace.

IV “Inability to carry on any physical activity Chest Pain

without discomfort—angina syndrome

may be present at rest.”

Group 1 Group 2

Myocardial Infarction With ST-Segment Elevation Unstable Angina–High Risk

clinical relevance of this information and or Left Bundle-Branch Block Unstable Angina–Low Risk

by discussing the role of combined find- Nonischemic Pain

ings and clinical prediction rules in the Myocardial Infarction Without ST-Segment Elevation

setting of acute MI. or Left Bundle-Branch Block

DEFINITIONS

Cardiac ischemic chest pain presents Figure 2.—Categorization of patients with acute chest pain in studies ascertaining test properties of history,

in a spectrum of conditions including an- physical examination, and electrocardiogram.

gina, unstable angina, and MI. Angina is

defined as a discomfort in the chest or mal or with an ECG progression labeled to establish the cause of their symptoms.

adjacent areas caused by myocardial is- probable and lesser symptoms.4 Recent economic pressures on the health

chemia, usually brought on by exertion, care system have highlighted the impor-

and associated with a disturbance of Diagnosis in Acute Chest Pain tance of distinguishing the second from

myocardial function, but without myo- Determining the correct diagnosis is the third group of patients.

cardial necrosis.1 Various grading sys- imperative to administering the appro- Ideally, we should have information

tems of the severity of angina pectoris priate therapy. The available therapeu- that allows us to classify patients into 1 of

have been developed. The classification tic options create the categories for pa- these 3 groups. Importantly, this is not,

proposed by the Canadian Cardiovascu- tients presenting to the ED with chest however, the issue addressed by most

lar Society,2 outlined in Table 1, is a prac- pain or other symptoms suggesting car- studies of the history and physical exami-

tical one adopted in a variety of settings. diac ischemia. Three distinct manage- nation in the setting of acute chest pain.

Unstable angina encompasses a spec- ment strategies determine the diagnos- Rather, as shown in Figure 2, studies re-

trum of symptomatic manifestations of tic groupings clinicians use currently viewed classified patients with acute

ischemic heart disease intermediate be- (Figure 1). chest pain into 2 groups based on the pres-

tween stable angina and acute MI. Based For the first group of patients, which ence (group 1) or absence (group 2) of MI.

on historical features, ECG findings includes those with MI and ST-segment Specifically, all patients with MI (Figure

(with and without pain), and hemody- elevation or left bundle-branch block 1, groups A and B) are compared with all

namic changes (low blood pressure, third (LBBB) (Figure 1, group A), current those without MI (Figure 1, group C).

heart sound, mitral regurgitation, and therapy consists of early thrombolytic The results of studies that used the

pulmonary crackles), guidelines have therapy and/or emergency percutane- Figure 2 design may mislead clinicians

been developed to stratify patients with ous transluminal coronary angioplasty. who need to discriminate between the 3

suspected unstable angina into high, in- A second group of patients includes groups of patients as shown in Figure 1.

termediate, or low risk of complications those with MI, but without ST-segment Clinical features that fail to distinguish

after initial evaluation.3 These guide- elevation or LBBB, or those with high- patients with infarct or high-risk un-

lines also recommend disposition based risk unstable angina (Figure 1, group B). stable angina from those with low-risk

on initial assessment of risk. These patients require intensive moni- unstable angina or nonischemic chest

The diagnosis of MI used in most stud- toring, immediate administration of as- pain might still be useful in the decision

ies is based on criteria proposed by the pirin, early administration of b-block- about whether to admit to a monitored

World Health Organization. In an at- ers, and possibly heparin therapy. The bed in an acute care hospital. The study

tempt to standardize the diagnosis of third group includes patients with low- design that most investigators have cho-

acute MI, the World Health Organiza- risk unstable angina or nonischemic sen, depicted in Figure 2, does not cor-

tion requires evolutionary changes on chest pain (Figure 1, group C). Clinicians relate with the current triage of chest

serially obtained ECG tracings or a rise may consider either admitting these pa- pain patients based on the therapeutic

and fall in serum cardiac markers either tients to an intermediate care setting or options available. Current therapeutic

with typical ischemic-type chest discom- ward bed or discharging them home with interventions for MI require the pres-

fort and an ECG result that was not nor- plans for subsequent diagnostic testing ence of ECG changes. It will, however,

JAMA, October 14, 1998—Vol 280, No. 14 A Question of Myocardial Infarction—Panju et al 1257

©1998 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: http://jama.jamanetwork.com/ by a University of St. Andrews Library User on 05/26/2015

Chest Pain

Cardiac Noncardiac

Ischemic Nonischemic Gastroesophageal Nongastroesophageal

Angina Unstable Myocardial Gastroesophageal Esophageal Peptic

Angina Infarction Reflux Disease Spasm Ulcer

Disease

Pericarditis Valvular Pneumothorax Pulmonary Musculoskeletal Somatoform

Embolism Disorder

(Panic Attack)

Aortic

Dissection

Figure 3.—Cardiac and noncardiac conditions presenting with chest pain.

provide clinically important information pain.6 Cardiac ischemic pain originates trates the most common of these condi-

when we have interventions that are in the myocardium, where free nerve tions, but is not all-inclusive.

clearly useful in acute MI both with and endings are the sensory receptors. Car- Given the diversity of the conditions

without ECG changes. In the interim, diac afferent impulses travel through fi- presenting with chest pain, and the ex-

this review will aid the reader in identi- bers in the cardiac sympathetic nerves, tent of the diagnostic testing that would

fying features of the history, physical ex- the upper 5 sympathetic ganglia, the be required, it is difficult to determine

amination, and ECG that help differen- white rami communicants, the gray the relative frequency of each of these

tiate acute MI, both with and without rami, and then via the upper 4 or 5 tho- conditions occurring in the setting of

ECG changes, from non-MI patients. racic roots. Cardiac afferent impulses chest pain. Pozen et al,8 in an evaluation

Clinicians must avoid misinterpreting project to the dorsal horn convergent of 1032 patients presenting to the ED

the diagnostic information we will pre- neurons and subsequently travel via the with a chief symptom of chest pain, in-

sent as if it were useful in differentiating spinothalamic tract to the thalamus and cluding follow-up ECG and cardiac en-

between the 3 groups in Figure 1. subsequently to the cortex, where the zyme tests for both hospitalized and

cardiac stimuli are decoded. nonhospitalized patients, reported an

Relevant Signs and Symptoms Afferent impulses also travel in the overall incidence of acute ischemia of

Patients with acute MI typically pre- cholinergic fibers of the vagus nerve, 29% (ischemia included new-onset or un-

sent with a characteristic combination of many of which arise from the inferior stable angina and MI). In an attempt to

signs and symptoms, as outlined in stan- cardiac wall. The signs and symptoms of determine the etiology of noncardiac

dard textbooks of medicine. Pain is de- nausea, bradycardia, and hypotension, chest pain, Panju et al9 conducted fur-

scribed as being the most common pre- which appear to be more prevalent in ther cardiac and gastrointestinal inves-

senting complaint, and considerable em- patients with inferior wall MI, are be- tigations in 100 patients discharged from

phasis is placed on the characteristics of lieved to be related to the larger number the coronary care unit (CCU) with chest

the pain, including its location, duration, of vagal afferent fibers located in the in- pain not yet diagnosed (8.1% of the CCU

radiation, and quality. Location of the ferior cardiac wall.7 admissions for chest pain). More than

pain includes the central portion of the Like other visceral sensations, myo- 75% of these patients had evidence of

chest or epigastrium, with potential ra- cardial pain is poorly and variably local- esophageal disorders by objective test-

diation to the arms, neck, jaw, or less ized. In addition, sensations originating ing, including 24-hour intraesophageal

commonly to the abdomen and back. in other intrathoracic structures (par- pH monitoring, upper gastrointestinal

Quality of the chest pain is characteris- ticularly the esophagus) can cause pain tract endoscopy with biopsy, esophageal

tically described using adjectives such that is indistinguishable from cardiac motility studies, or upper gastrointesti-

as squeezing, crushing, and pressure. pain. nal tract barium series. These results are

Other symptoms also may be present, generalizable to patients discharged

including diaphoresis, nausea, vomiting, Conditions That May Present from the CCU with chest pain not yet

weakness, and syncope. While certain With Symptoms Suggestive of MI diagnosed, a distinct subset of the pa-

features have been identified as being im- There are many other clinical condi- tients with noncardiac chest pain pre-

portant in recognizing MI, follow-up data tions that can present with symptoms senting to the ED.

from the Framingham Study cohort es- suggestive of acute MI, which can be

timate that approximately 25% of infarcts broadly divided into cardiac and noncar- METHODS

may go unrecognized due to either lack of diac disorders. The noncardiac causes of

chest pain or atypical symptoms.5 chest pain are further divided into gas- Inclusion Criteria of Tests

troesophageal diseases and nongastro- for Precision and Accuracy

Mechanism of Chest Pain in MI esophageal diseases, while the cardiac Given the limited number of studies

Three quarters of all patients with rec- causes are grouped into ischemic and that have focused on the precision of the

ognized acute MI present with chest nonischemic conditions. Figure 3 illus- history, physical examination, and ECG

1258 JAMA, October 14, 1998—Vol 280, No. 14 A Question of Myocardial Infarction—Panju et al

©1998 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: http://jama.jamanetwork.com/ by a University of St. Andrews Library User on 05/26/2015

Table 2.—Interobserver Agreement in Recording Chest Pain Histories* Table 3.—Interobserver Agreement in Assessment

of Physical Symptoms and Signs of Heart Failure in

Inpatients (N = 197) Outpatients (N = 112) Myocardial Infarction Patients*

Two Internist and Nurse and Nurse and Physical Sign Range, k

Attribute Internists, k Questionnaire, k Internist, k Questionnaire, k

Dyspnea 0.62-0.75

Pain radiates to left arm 0.89 0.58 0.43 0.41 Displaced apex beat 0.53-0.73

Pain relieved by nitroglycerin 0.79 0.51 0.94 0.77 S3 gallop 0.14-0.37

History of myocardial infarction 0.78 0.81 0.70 0.81 Rales 0.12-0.31

Pain in substernal location 0.74 0.50 0.38 0.19 Neck vein distention 0.31-0.51

Hepatomegaly 0.00-0.16

Pain brought on by exertion 0.63 0.51 0.42 0.22 Dependent edema 0.27-0.64

Pain described as “pressure” 0.57 0.37 0.49 0.50

Patient must stop activities when pain occurs 0.50 0.47 0.44 0.40 *Adapted, with permission, from Gadsboll et al.14

Pain brought on by cough or deep breath 0.44 0.30 0.55 0.62

Pain described as “sharp” 0.30 0.26 0.33 0.31

variation) or within observers (intraob-

Pain brought on by moving arms or torso 0.27 0.44 0.52 0.54 server variation) regarding a particular

clinical finding. Hickan and colleagues12

*Adapted, with permission, from Hickan et al.12 studied the precision of an important as-

pect of the history, namely that of chest

in the diagnosis of MI, we developed a articles might be relevant, she and an- pain. They assessed the interobserver

broad set of inclusion criteria. We in- other author (A.A.P.) reviewed the ar- agreement in chest pain histories ob-

cluded studies that consisted of an as- ticles in detail and determined their eli- tained by general internists, nurse

sessment of the interobserver and/or in- gibility. practitioners, and self-administered ques-

traobserver variation, of features of the tionnaires for 197 inpatients and 112 out-

history, physical examination, and ECG Methodologic Quality Assessments patients with chest pain. As outlined in

among patients with chest pain or a di- We evaluated the methodologic qual- Table 2, the 2 internists, who each inde-

agnosis of MI. ity of articles addressing the accuracy of pendently interviewed 47 of 197 inpa-

For the accuracy of the history, physi- history, physical examination, or ECG tients, showed high agreement for 7 of the

cal examination, and ECG, we included using criteria adapted from Sackett and 10 items, including location and descrip-

studies that met the following criteria: Goldsmith and previously used in this tion of the pain, as well as aggravating and

(1) patients: those with chest pain thought series.10 A grade A designation meant an relieving factors. Agreement was slightly

to be ischemic in nature; (2) test: history, independent, blind comparison of sign or lower between internist and question-

physical examination, or ECG described symptom with a “gold standard” among naire and between the nurse practition-

in adequate detail; (3) outcome: MI or no 500 or more consecutive patients sus- ers and internist, with the lowest level of

infarction using the definition described pected of having the target condition; agreement between nurse and question-

above; (4) sample size: studies with a grade B meant an independent, blind naire. Features of the chest pain associ-

sample size of at least 200 patients. comparison of sign or symptom with a ated with a lower probability of MI,

gold standard among fewer than 500 con- namely pleuritic, positional, and sharp

Search Strategy secutive patients suspected of having chest pain, typically showed a lower level

For both precision and accuracy of the the target condition; grade C meant an of agreement for all comparisons.

history, physical examination, and ECG independent, blind comparison of sign or The precision of the history obtained

we performed an English-language symptom with a standard of uncertain is also dependent on the reliability of

MEDLINE search from 1980 using the validity; or independent, blind compari- the sources themselves. Kee and col-

following Medical Subject Heading son of sign or symptom with a gold stan- leagues13 assessed the reliability of a re-

(MeSH) terms and search strategy: dard among nonconsecutive patients ported family history of MI from pa-

(1) medical history taking or physical ex- suspected of having the target disorder. tients who had recently survived MI

amination and myocardial infarction or with that of other documented sources

chest pain and (2) reproducibility of re- Analysis including hospital charts and death cer-

sults or observer variation and myocar- To calculate LRs for features of the tificates. They reported a moderate level

dial infarction or chest pain. A tex- history, physical examination, and ECG, of agreement with a k of 0.65.

tword search was also performed using we considered studies suitable for com- Few studies have evaluated the pre-

interobserver, intraobserver, accuracy, bination if the sensitivity and specificity cision of features of the physical exami-

precision, reliability, sensitivity, speci- met 1 of the following criteria: (1) x2 test nation in the assessment of patients with

ficity, and myocardial infarction or chest of sensitivity and specificity excluding suspected MI. One study did evaluate

pain. Additional search strategies for ac- statistically significant heterogeneity the interobserver agreement between 3

curacy included the term myocardial in- (P..05) or (2) range of sensitivity and clinicians in the assessment of physical

farction, diagnosis (subheading). For all specificity across studies of 15% or less. symptoms and signs of heart failure in

strategies, references from appropriate We pooled studies satisfying at least 1 102 MI patients.14 As shown in Table 3,

articles were reviewed to provide addi- criterion and calculated LRs by simple agreement was high for dyspnea, as well

tional references for this article. Of the combination of results across studies. as for the displaced apex beat. However,

14 references used to assess the preci- The 95% confidence intervals were cal- the level of agreement for the other

sion and accuracy of the history, physi- culated according to the method of Simel physical symptoms and signs of heart

cal examination, and ECG in the diagno- et al.11 failure, particularly the assessment of

sis of acute MI, 12 were obtained from the pulmonary rales and hepatomegaly, was

MEDLINE search strategy outlined and RESULTS considerably lower.

2 from the review of reference lists.

Precision of the History Precision of the ECG Interpretation

Selection of Articles and Physical Examination Unfortunately, most studies that have

One author (B.R.H.) initially screened Precision refers to the degree of varia- assessed the precision of ECG interpre-

the titles and abstracts. If she felt the tion between observers (interobserver tation have simply reported the percent-

JAMA, October 14, 1998—Vol 280, No. 14 A Question of Myocardial Infarction—Panju et al 1259

©1998 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: http://jama.jamanetwork.com/ by a University of St. Andrews Library User on 05/26/2015

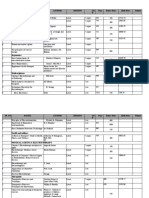

Table 4.—Features of Studies Used to Determine Accuracy of the History, Physical Examination, and Electrocardiogram

Methodologic Incidence of No. of Patients

Source, y Quality* Inclusion Criteria Myocardial Infarction (MI), % (% Women) Age, y Country

Rude et al,21 1983 A Consecutive patients admitted to 48.9 3697 (38) Mean = 61 United States

coronary care unit (CCU) with

suspected MI

Yusuf et al,22 1984 B Consecutive patients admitted to CCU 85.1 475 (15.4) Mean = 56.2 United Kingdom

with suspected MI

Pozen et al,8 1984 A Consecutive patients presenting to NR 2801 (NR) Males $30 United States

emergency department (ED) with Females $40

chest pain

Lee et al,23 1985 A Consecutive patients presenting to ED 17.4 596 (52.0) $25 United States

with chest pain

Tierney et al,24 1986 B Consecutive patients presenting to ED 12.4 492 (NR) Males $30 United States

with chest pain Females $40

25

Herlihy et al, 1987 B Consecutive patients admitted to CCU 44.5 265 (NR) Not reported United States

with suspected MI

Klaeboe et al,26 1987 B Consecutive patients admitted to CCU 59.1 237 (35.8) Range = 29-90 Norway

with suspected MI

Rouan et al,27 1989 A Consecutive patients presenting to ED 14.4 7115 (50.0) $30 United States

with chest pain

28

Solomon et al, 1989 A Consecutive patients presenting to ED 14.5 7734 (50.3) $30 United States

with chest pain

Berger et al,29 1990 B Consecutive patients admitted to hospital 36.0 278 (30.9) 57.2 Switzerland

with chest pain

Weaver et al,30 1990 C Patients with chest pain brought to ED 18.3 2472 (NR) ,75 United States

by paramedics

Jonsbu et al,31 1991 B Consecutive patients admitted to hospital 36.5 200 (NR) Not reported Norway

with suspected MI

32

Karlson et al, 1991 A Consecutive patients admitted to hospital 19.6 4690 (NR) Not reported Sweden

with suspected MI

Kudenchuk et al,33 1991 C Patients brought to ED by paramedics 32.9 1189 (34) #74 United States

*See “Methodologic Quality Assessments” subsection of the text for an explanation of these grades.

age agreement between clinicians, with- The precision in the interpretation of tients with chest pain brought to the ED

out taking into account chance agreement ECGs appears to increase with experi- by paramedics.30,33

through the use of k or other statistical ence. Eight cardiologists interpreted The studies examined a variety of fea-

measures.15 Precise interpretations are ECGs of 1220 clinically validated cases of tures of the clinical examination and

important because they are made at the various cardiac disorders including ante- ECG. For the sake of relevance and clar-

bedside and set off immediate manage- rior, inferior, or combined MI, as well as ity we have chosen to present only the

ment strategies. There are several fac- right, left, or biventricular hypertrophy.19 results of those variables in which an LR

tors that may influence the interpreta- The interobserver agreement between of 2.0 or more or 0.5 or less was obtained.

tion of the ECG, including the clinical cardiologists was reasonably high, with These studies provide the best available

observation of the patient and clinical an average k of 0.67. For the 125 selected evidence for identifying those features

data (expectation bias), as well as the ECGs that were read twice by each car- that aid in the diagnosis of MI.

training and experience of the individual diologist, different diagnoses were given

reading the ECG. Although they must be for 10% to 23% of the ECGs (intraob- Accuracy of the History

interpreted with caution, the results of server reproducibility, 76.8%-90.4%). and Physical Examination

earlier studies suggest appreciable vari- Sgarbossa et al20 have assessed the Nine of the studies outlined in Table 4

ability in precision in the interpretation precision of features of the ECG that reported the relation between features

of ECGs. may aid in the diagnosis of acute MI in of the clinical examination of patients

In one of the earlier studies,16 10 clini- the presence of LBBB. In this study, 4 presenting to the ED with chest pain, as

cians with experience in cardiology read investigators read 2600 ECGs and determined by physicians, with that of

100 ECGs on 2 separate occasions and achieved a k of more than 0.85 for QRS- the final diagnosis of MI. In all studies,

classified the tracings as normal, abnor- complex and T-wave polarities, with a the gold standard for the diagnosis of MI

mal, or infarction. The 3 clinicians agreed high degree of correlation among the in- was based on cardiac enzyme and ECG

completely in only one third of the ECGs. vestigators for interpretation of ST-seg- changes, except for the study by Weaver

Following a second reading, the clinicians ment deviation (Pearson product mo- et al30 in which the discharge diagnosis

disagreed with 1 of 8 of their original re- ment correlation coefficient, .0.9). was used to define acute MI. Although

ports. Gjorup et al17 had 16 residents in features of the clinical examination are

internal medicine read 107 ECGs of sus- Studies Used to Determine Accuracy extremely insensitive in diagnosing MI,

pected MI patients and assessed whether of the History, Physical Examination, they are reasonably specific and their

signs indicative of acute infarction were and ECG presence is more likely to occur in pa-

present. There was disagreement in ap- Table 4 summarizes features of the 14 tients with MI.

proximately 70% of the cases. studies8,21-33 used to determine the accu- As noted in Table 5, chest pain radia-

Brush et al18 reported much higher racy of the history, physical examina- tion was the clinical feature that increased

agreement in a study in which 2 clini- tion, and ECG in the diagnosis of acute the probability of MI the most, with a

cians classified 50 ECGs according to MI. Five of the studies included consecu- wider extension of pain associated with

evidence of infarction, ischemia or strain, tive patients presenting to the ED with the highest likelihood of MI. In particular,

left ventricle hypertrophy, LBBB, or chest pain,8,23,24,27,28 7 included patients chest pain radiating to the left arm was

paced rhythm. They obtained agree- admitted to the hospital or CCU for sus- twice as likely to occur in patients with, as

ment in 45 of the 50 cases (k = 0.69). pected MI,21,22,25,26,29,31,32 and 2 included pa- opposed to those without, MI, while ra-

1260 JAMA, October 14, 1998—Vol 280, No. 14 A Question of Myocardial Infarction—Panju et al

©1998 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: http://jama.jamanetwork.com/ by a University of St. Andrews Library User on 05/26/2015

diation to the right shoulder was 3 times Table 5.—Clinical Features That Increase the Probability of a Myocardial Infarction in Patients

as likely and radiation to both the left and Presenting With Acute Chest Pain

right arm was 7 times as likely to occur in Likelihood Ratio

such patients. Chest pain radiating to the Clinical Feature (95% Confidence Interval) Reference

right arm alone has been reported to be an Pain in chest or left arm 2.7* 8

extremely specific, but insensitive, Chest pain radiation

marker of MI (LR, 8.9; 95% confidence Right shoulder 2.9 (1.4-6.0) 24

interval,1.1-75.1).29 However,asreflected Left arm 2.3 (1.7-3.1) 29

by the width of the confidence interval, Both left and right arm 7.1 (3.6-14.2) 29

these results were based on a small num- Chest pain most important symptom 2.0* 8

ber of subjects (6 of the 100 patients with History of myocardial infarction 1.5-3.0† 8, 24

MI) and must therefore be interpreted Nausea or vomiting 1.9 (1.7-2.3) 24, 25, 29, 31

Diaphoresis 2.0 (1.9-2.2) 24, 28, 31

with caution.

Third heart sound on auscultation 3.2 (1.6-6.5) 24

Further aspects of the chest pain, in-

Hypotension (systolic blood pressure #80 mm Hg) 3.1 (1.8-5.2) 30

cluding presence of pain in the chest or

Pulmonary crackles on auscultation 2.1 (1.4-3.1) 24

left arm, and chest pain described as the

most important symptom were associ- *Data not available to calculate confidence intervals.

ated with LRs of 2.7 and 2.0, respec- †In heterogeneous studies the likelihood ratios are reported as ranges.

tively. Other items of the history that

aided in the diagnosis of MI included his- Table 6.—Clinical Features That Decrease the Probability of a Myocardial Infarction in Patients Presenting

tory of MI, nausea and vomiting, and dia- With Acute Chest Pain

phoresis (LRs#3.0 past history and a Likelihood Ratio

combined LR of 1.9 and 2.0 for nausea Clinical Feature (95% Confidence Interval) Reference

and vomiting and diaphoresis). Pleuritic chest pain 0.2 (0.2-0.3) 23, 24, 28

A number of features from the history Chest pain sharp or stabbing 0.3 (0.2-0.5) 23, 24

and clinical examination thought to be Positional chest pain 0.3 (0.2-0.4) 23, 28

useful in determining the presence of MI Chest pain reproduced by palpation 0.2-0.4* 23, 24, 28

were in fact of little value in establishing

*In heterogeneous studies the likelihood ratios are reported as ranges.

such a diagnosis. Features of the his-

tory, including age above 60 years, male

sex, history of angina or coronary artery Table 6 presents clinical features that also much more likely to occur in patients

disease, history of nitroglycerin use, du- decrease the probability of MI. Chest with, as opposed to those without, MI,

ration of chest pain greater than 60 min- pain described as pleuritic, sharp, stab- with LRs ranging from 5.3 to 24.8, al-

utes, constant or episodic chest pain, and bing, or positional decreased the likeli- though the usefulness of this finding was

chest pain of sudden onset, were all as- hood of MI significantly. In addition, reduced when patients with old Q waves

sociated with LRs of less than 2. Adjec- chest pain reproduced by palpation on were included.

tives used to describe the quality of the physical examination was associated ST-segment depression, whether new

chest pain, including that of pressure, with a low LR, ranging from 0.2 to 0.4. or known to have been present previ-

aching, and squeezing, were also associ- ously, and new T-wave peaking or inver-

ated with LRs of less than 2. Therefore, Accuracy of the ECG sion were all approximately 3 times as

none of these features carry information Eight studies addressed the accuracy likely to occur in patients with, as op-

independently useful in establishing an of the ECG in diagnosing MI. The results posed to those without, MI. In addition,

MI diagnosis. reported in this article are for interpre- conduction defects, particularly those

The 3 components of the physical ex- tation of the ECGs by clinicians and not reported to be new, also increased the

amination associated with LRs higher by computer algorithms. Interpretation probability of MI.

than 2 included hypotension, presence of of the ECG was by an independent phy- A normal ECG decreased the prob-

a third heart sound, and pulmonary sician blinded to the clinical data in 5 of ability of MI the most and was associ-

crackles on auscultation (LRs of 3.1, 3.2, the studies,8,21,22,32,33 by the ED physician ated with LRs of 0.1 to 0.3.19,20,26,31

and 2.1, respectively). Dyspnea was not alone in 2 others,23,27 and by the ED phy-

found to be an important component of sician with a review by an independent The Role of Combined Findings

the clinical examination. Other features physician blinded to the clinical data in and Clinical Prediction Rules for MI

frequently described in the assessment 1.24 In all studies the gold standard for the Clinicians are frequently presented

of the patient with chest pain, including diagnosis of MI was based on cardiac en- with multiple clinical examination items,

bradycardia and tachycardia, were not zymes, except for the study by Kuden- each of which can be considered a sepa-

evaluated. chuk et al,33 in which the hospital dis- rate diagnostic test for establishing the

Cardiac risk factors, including hyper- charge diagnosis was used to define MI. diagnosis of MI. The challenge in situa-

tension, smoking, obesity, hypercholes- Several features of the ECG have been tions such as this is in knowing how to

terolemia, diabetes, and a family history used to assist in the diagnosis of acute MI. combine the LRs from these multiple

of cardiovascular disease, are frequently The most common characteristics include tests to obtain an accurate estimate of

included in the history of a patient pre- the presence of Q waves, ST-segment el- the posttest probability of MI. The

senting with chest pain. However, cur- evation or depression, and T-wave inver- simple serial multiplication of LRs that

rent evidence provides little support for sion. As noted in Table 7, there was a con- has been proposed assumes that the

the diagnostic value of a history of these siderable degree of variability between tests are conditionally independent,15

risk factors. In 3 large studies of patients studies for some of these features. New that is, that the patient’s results on one

presenting to the ED with chest pain, ST-segment elevation was the most pow- test bear no relationship to the results

none of the classic cardiac risk factors erful feature in increasing the probability on any of the other tests. As demon-

emerged as independent predictors of of MI, with the LRs ranging from 5.7 to strated by Holleman and Simel,36 viola-

acute MI.8,34,35 53.9. The presence of a new Q wave was tion of the conditional independence as-

JAMA, October 14, 1998—Vol 280, No. 14 A Question of Myocardial Infarction—Panju et al 1261

©1998 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: http://jama.jamanetwork.com/ by a University of St. Andrews Library User on 05/26/2015

Table 7.—Features of the Electrocardiogram That Increase the Probability of a Myocardial Infarction in Pa- A classic and widely used example of this

tients Presenting With Acute Chest Pain concept was proposed by Diamond and

Likelihood Ratio Forrester.42 Estimates of the pretest

Feature of the Electrocardiogram (95% Confidence Interval) Reference(s) probability of coronary artery disease on

New ST-segment elevation $1 mm 5.7-53.9* 21-24, 32, 33 the basis of age, sex, and chest pain de-

New Q wave 5.3-24.8* 21, 24, 32, 33 scription have been published and are

Any ST-segment elevation 11.2 (7.1-17.8) 24 easily used in the clinical setting. A more

New conduction defect 6.3 (2.5-15.7) 24 comprehensive attempt to consider all

New ST-segment depression 3.0-5.2* 21, 24, 32 clinical characteristics has also been un-

Any Q wave 3.9 (2.7-5.7) 24 dertaken.43

Any ST-segment depression 3.2 (2.5-4.1) 24 The predictive value of the history,

T-wave peaking and/or inversion $1 mm 3.1† 8 physical examination, and ECG present-

New T-wave inversion 2.4-2.8* 24, 32, 33 ed also depends therefore on the pretest

Any conduction defect 2.7 (1.4-5.4) 24 probability of MI. Even with a normal

*In heterogeneous studies the likelihood ratios are reported as ranges. ECG result, for example, a high pretest

†Data not available to calculate confidence intervals. probability of MI would result in a high

posttest probability of this condition be-

sumption can yield inaccurate posttest hour or more, pain worse than usual an- ing present. Proper use of these findings

probabilities of disease. Unfortunately, gina or the same as earlier MI, and radia- must therefore incorporate the pretest

the precision and accuracy of combina- tion of pain to neck, left shoulder, or left probability of MI.

tion of findings were not reported in the arm as predictors of infarction. Features

studies included in this review. How- of the chest pain including radiation to the COMMENT

ever, the combination of clinical findings back, abdomen, or legs, stabbing pain, and The diagnosis of MI in the setting of

are assessed in clinical prediction rules. pain reproduced by palpation included in chest pain is a complex task. Clinicians

By combining findings from patients’ the algorithm lower the probability of in- categorize patients with chest pain into 3

history, physical examination, and ECG, farction. The ECG changes predictive of groups based on current therapeutic in-

investigators have developed probabil- an acute MI included new ST-segment el- terventions, while in the literature pa-

ity-based decision aids, as well as com- evation or Q waves in 2 or more leads and tients with chest pain are typically cat-

puter-based protocols and guidelines, new ST-T–segment changes of ischemia egorized into the presence or absence of

that categorize patients with chest pain or strain. On the basis of the algorithm, MI. Based on this latter categorization,

into risk groups based on their probabil- patients can be assigned to 1 of 14 sub- we have assessed the features of the his-

ity of MI.34,35,37 These tools have been de- groups, with a probability of acute MI tory, physical examination, and ECG,

vised to improve physician recognition ranging from 1% to 77%. which aid in increasing or decreasing the

and triage of patients with acute ische- These prediction rules included sev- likelihood of acute MI. We have also ad-

mic events.8,38 Although these measures eral of the common variables identified dressed the use of clinical prediction

have helped clinicians make appropriate in univariate analysis and included in rules, which use a number of clinical vari-

decisions, not all studies of probability- this review, namely the location and ex- ables, to aid in the diagnosis of MI, as well

based risk assessment tools have dem- tent of the chest pain, chest pain with as the need to take into account pretest

onstrated improvement in ED triage or diaphoresis, and ECG changes including probability of disease when assessing the

reduction in resource utilization.39 These new Q-wave and ST-segment elevation. predictive value of individual variables.

clinical prediction rules conform to the However, in situations in which the in- Referring back to the scenarios pre-

methodological standards of clinical pre- dependence of features of the history sented at the beginning of this article, the

diction rules initially proposed by Was- and clinical examination has not been first 3 have features that increase the

son et al,40 and recently revised,41 except tested, as in these studies, clinicians likelihood of acute MI. Patient 1 has chest

for the validation of the rule by Tierney must be cautious when interpreting and pain, diaphoresis, and ST-segment eleva-

et al,34 which was performed on a subset, attempting to combine these multiple tion. Patient 2 has diaphoresis, hypoten-

rather than on a prospective sample of clinical findings. In these situations they sion, and history of an MI. Patient 3 has

the population. may look to clinical prediction rules to nausea and ST-segment elevation. In con-

Tierney et al34 developed an instru- help integrate and interpret the results. trast, Patient 4 has features that decrease

ment for the prediction of MI. Based on the likelihood of MI, namely, chest pain

multivariate analysis of 540 ED patients Pretest Probability that is both positional and reproducible

with chest pain, 4 variables with inde- in the Diagnosis of MI by palpation and a normal ECG.

pendent predictive value for infarction To determine the posttest probability, Clinicians interested in distinguishing

were identified. These included diapho- or likelihood, of disease based on the clini- patients with acute MI from those with un-

resis with chest pain, history of MI, ECG cal features and their associated LRs, one stable angina and nonanginal chest pain

changes of a new Q wave, and ST-seg- must take into account the pretest prob- can use either Goldman’s algorithm or the

ment elevation either new or old. ability, or likelihood, of that condition. Al- individual clinical features that we sum-

Goldman et al35,37 also developed a pro- though much focus has been placed on the marize in Tables 5 to 7. However, the dis-

tocol to predict MI in ED patients with combination of multiple clinical variables tinction between MI and non-MI chest

chest pain. The instrument was based on and the development of prediction rules pain may not be the most relevant initial

the history, physical examination, and for MI, as described above, there has been clinical decision; it is more important to de-

ECG of more than 6000 patients present- little emphasis on establishing the pre- cide on appropriate immediate therapy.

ing at an ED with a chief complaint of test probability of MI based on standard

chest pain. Variables in Goldman’s algo- clinical assessment. If an estimate of the THE BOTTOM LINE

rithm include patient’s age above 40 pretest probability of MI is available, a The presence of any of the following

years, history of angina or MI, chest pain diagnostic test, based on its sensitivity, clinical findings increases the likelihood

that began less than 48 hours prior to ar- specificity, and LR, can be used to estab- of MI: patients presenting with chest

rival at the ED, longest pain episode 1 lish a new estimate of disease likelihood. pain radiating to the left arm, radiating

1262 JAMA, October 14, 1998—Vol 280, No. 14 A Question of Myocardial Infarction—Panju et al

©1998 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: http://jama.jamanetwork.com/ by a University of St. Andrews Library User on 05/26/2015

to the right shoulder, or radiating to both Features of ECG that increase the like- admission from those with less danger-

left and right arms; and patients present- lihood of MI include the following: new ous ischemia or nonischemic pain.

ing with chest pain diaphoresis, a third ST-segment elevation, new Q waves, any Further research is required in this

heart sound, or with hypotension. ST-segment elevation, and new conduc- regard.

The presence of any of the following tion defect. A normal ECG is a powerful

clinical findings decreases the likelihood feature in ruling out MI. We are indebted to Eric C. Westman, MD, Mi-

of MI: patients presenting with chest Finally, as noted previously, these chael Cuffe, MD, Salim Yusuf, MD, and Ernest

Fallen, MD, for their review and contribution to the

pain that is described as pleuritic, sharp findings may not be relevant for distin- manuscript, as well as to John Attia, MD, Arie

or stabbing, positional, or reproduced by guishing between patients with acute Levinson, MD, and James Velianou, MD, for their

palpation. ischemic syndromes requiring CCU suggestions on the final manuscript.

References

1. Mathews MB, Julian DG. Angina pectoris: defi- Godtfredsen J. Interpretation of the electrocardio- 30. Weaver WD, Eisenberg S, Martin JS, et al. Myo-

nition and description. In: Julian DG, ed. Angina gram in suspected myocardial infarction: a random- cardial Infarction Triage and Intervention Project,

Pectoris. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Churchill Living- ized controlled study of the effect of a training pro- phase I: patient characteristics and feasibility of pre-

stone Inc; 1985:2. gramme to reduce interobserver variation. J Intern hospital initiation of thrombolytic therapy. J Am

2. Campeau L. Grading of angina pectoris. Circu- Med. 1992;231:407-412. Coll Cardiol. 1990;15:925-931.

lation. 1976;54:522-523. 18. Brush JE, Brand DA, Acampora D, Chalmer B, 31. Jonsbu J, Rollag A, Aase O, et al. Rapid and

3. Braunwald E, Jones RH, Mark DB, et al. Diag- Wackers FJ. Use of the initial electrocardiogram to correct diagnosis of myocardial infarction: standard-

nosing and managing unstable angina. Circulation. predict in-hospital complications of acute myocar- ized case history and clinical examination provide

1994;90:613-622. dial infarction. N Engl J Med. 1985;312:1137-1141. important information for correct referral to moni-

4. Tunstall-Pedoe H, Kuulasmaa K, Amouyel P, 19. Willems JL, Abreu-Lima C, Arnaud P, et al. The tored beds. J Intern Med. 1991;229:143-149.

Arveiler D, Rajakangas AM, Pajak A. Myocardial diagnostic performance of computer programs for 32. Karlson BW, Herlitz J, Wiklund O, Richter A,

infarction and coronary deaths in the World Health the interpretation of electrocardiograms. N Engl J Hjalmarson A. Early prediction of acute myocardial

Organization Monica Project. Circulation. 1994;90: Med. 1991;325:1767-1773. infarction from clinical history, examination and

583-612. 20. Sgarbossa EB, Pinski SL, Barbagelata A, et al. electrocardiogram in the emergency room. Am J

5. Kannel WB, Abbott RD. Incidence and prognosis Electrocardiographic diagnosis of evolving acute Cardiol. 1991;68:171-175.

of unrecognized myocardial infarction. N Engl J myocardial infarction in the presence of left bundle- 33. Kudenchuk PJ, Ho MT, Weaver D, et al. Accu-

Med. 1984;311:1144-1147. branch block. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:481-487. racy of computer-interpreted electrocardiography

6. Uretsky BF, Farquhar DS, Berezin AF, Hood 21. Rude RE, Poole WK, Muller JE, et al. Electro- in selecting patients for thrombolytic therapy. J Am

WB. Symptomatic myocardial infarction without cardiographic and clinical criteria for recognition of Coll Cardiol. 1991;17:1486-1491.

chest pain: prevalence and clinical course. Am J Car- acute myocardial infarction based on analysis of 34. Tierney WM, Roth BJ, Psaty B, et al. Predictors

diol. 1977;40:498-503. 3,697 patients. Am J Cardiol. 1983;52:936-942. of myocardial infarction in emergency room pa-

7. Ness TJ, Gebbart GF. Visceral pain: a review of 22. Yusuf S, Pearson M, Parish S, Ramsdale D, tients. Crit Care Med. 1985;13:526-531.

experimental studies. Pain. 1990;41:167-234. Rossi P, Sleight P. The entry ECG in the early di- 35. Goldman L, Cook EF, Brand DA, et al. A com-

8. Pozen MW, D’Agostino RB, Selker HP, Syt- agnosis and prognostic stratification of patients with puter protocol to predict myocardial infarction in

kowski PA, Hood WB. A predictive instrument to suspected acute myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J. emergency department patients with chest pain.

improve coronary care unit admission practices in 1984;5:690-696. N Engl J Med. 1988;318:797-803.

acute ischemic heart disease. N Engl J Med. 1984; 23. Lee TH, Cook EF, Weisberg M, Sargent RK, 36. Holleman DR, Simel DL. Quantitative assess-

310:1273-1278. Wilson C, Goldman L. Acute chest pain in the emer- ments from the clinical examination: how should cli-

9. Panju A, Farkouh ME, Sackett DL, et al. Out- gency room. Arch Intern Med. 1985;145:65-69. nicians integrate the numerous results? J Gen In-

come of patients discharged from a coronary care 24. Tierney WM, Fitzgerald D, McHenry R, et al. tern Med. 1997;12:165-171.

unit with a diagnosis of “chest pain not yet diag- Physicians’ estimates of the probability of myocar- 37. Goldman L, Weinberg M, Weisberg M, et al. A

nosed.” CMAJ. 1996;155:541-547. dial infarction in emergency room patients with computer-derived protocol to aid in the diagnosis of

10. Holleman DR, Simel DL. Does the clinical ex- chest pain. Med Decis Making. 1986;6:12-17. emergency room patients with acute chest pain.

amination predict airflow limitation? JAMA. 1995; 25. Herlihy T, McIvor ME, Cummings CC, Siu CO, N Engl J Med. 1982;307:588-596.

273:313-319. Alikahn M. Nausea and vomiting during acute myo- 38. Sarasin F, Reymond J, Griffith J, et al. Impact of

11. Simel DL, Samsa GP, Matchar DB. Likelihood ra- cardial infarction and its relation to infarct size and the acute cardiac ischemia time-insensitive predic-

tios with confidence: sample size estimation for diag- location. Am J Cardiol. 1987;60:20-22. tive instrument (ACI-TIPI) on the speed of triage

nostic test studies. J Clin Epidemiol. 1991;44:763-770. 26. Klaeboe G, Otterstad JE, Winsnes T, Espeland decision making for emergency department patients

12. Hickan DH, Sox HC, Sox CH. Systematic bias in N. Predictive value of prodromal symptoms in presenting with chest pain. J Gen Intern Med. 1994;

recording the history in patients with chest pain. myocardial infarction. Acta Med Scand. 1987;222: 9:187-194.

J Chronic Dis. 1985;38:91-100. 27-30. 39. Pearson S, Goldman L, Garcia T, Wok E, Lee T.

13. Kee F, Tiret L, Robo JY, et al. Reliability of 27. Rouan GW, Lee TH, Cook EF, Brand DA, Physician response to a prediction rule for triage of

reported family history of myocardial infarction. Weisberg MC, Goldman L. Clinical characteristics emergency department patients with chest pain.

BMJ. 1993;307:1528-1530. and outcome of acute myocardial infarction in J Gen Intern Med. 1994;9:241-247.

14. Gadsboll N, Hoilund-Carlsen PF, Nielsen GG, patients with initially normal or nonspecific electro- 40. Wasson JH, Sox HC, Neff RK, Goldman L. Clini-

et al. Symptoms and signs of heart failure in patients cardiograms. Am J Cardiol. 1989;64:1087-1092. cal prediction rules: application and methodological

with myocardial infarction: reproducibility and re- 28. Solomon CG, Lee TH, Cook EF, et al. Compari- standards. N Engl J Med. 1985;313:793-799.

lationship to chest x-ray, radionuclide ventriculog- son of clinical presentation of acute myocardial in- 41. Laupacis A, Sekar N, Stiell IG. Clinical predic-

raphy and right heart catheterization. Eur Heart J. farction in patients older than 65 years of age to tion rules: a review and suggested modifications of

1989;10:1017-1028. younger patients: the Multicenter Chest Pain Study methodological standards. JAMA. 1997;277: 488-494.

15. Sackett DL, Haynes RB, Guyatt GH, Tugwell experience. Am J Cardiol. 1989;63:772-776. 42. Diamond GA, Forrester JS. Analysis of prob-

P. Clinical Epidemiology: A Basic Science for 29. Berger JP, Buclin R, Haller E, Van Melle G, ability as an aid in the clinical diagnosis of coronary

Clinical Medicine. 2nd ed. Boston, Mass: Little Yersin B. Right arm involvement and pain exten- artery disease. N Engl J Med. 1979;300:1350-1358.

Brown & Co Inc; 1991. sion can help to differentiate coronary diseases from 43. Pryor DB, Harrell FE Jr, Lee KL, Califf RM,

16. Davies LG. Observer variation in reports of chest pain of other origin: a prospective emergency Rosati RA. Estimating the likelihood of significant

electrocardiograms. Br Heart J. 1958;20:153-161. ward study of 278 consecutive patients admitted for coronary artery disease. Am J Med. 1983;75:

17. Gjorup T, Kelbaek H, Nielsen D, Kreiner S, chest pain. J Intern Med. 1990;227:165-172. 771-780.

JAMA, October 14, 1998—Vol 280, No. 14 A Question of Myocardial Infarction—Panju et al 1263

©1998 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: http://jama.jamanetwork.com/ by a University of St. Andrews Library User on 05/26/2015

You might also like

- Case-Based Device Therapy for Heart FailureFrom EverandCase-Based Device Therapy for Heart FailureUlrika Birgersdotter-GreenNo ratings yet

- Diagnosis of Acute Myocardial InfarctDocument5 pagesDiagnosis of Acute Myocardial InfarctOscar SanNo ratings yet

- Caso Clinico Clinica Mayo 2Document5 pagesCaso Clinico Clinica Mayo 2Francisco HernandezNo ratings yet

- Is It Always Anterior Chest Pain Angina Pectoris?Document7 pagesIs It Always Anterior Chest Pain Angina Pectoris?Diana MinzatNo ratings yet

- Omur - Tc-99m MIBI Myocard Perfusion SPECT Findings in Patients With Typical Chest Pain and Normal Coronary ArteriesDocument8 pagesOmur - Tc-99m MIBI Myocard Perfusion SPECT Findings in Patients With Typical Chest Pain and Normal Coronary ArteriesM. PurnomoNo ratings yet

- Higher Troponin Levels Linked to Embolic StrokesDocument7 pagesHigher Troponin Levels Linked to Embolic StrokesafbmgNo ratings yet

- STEMi Reading MaterialDocument14 pagesSTEMi Reading MaterialJerry GohNo ratings yet

- Depresion Del ST DX DifDocument7 pagesDepresion Del ST DX DifMiguel Angel Hernandez SerratoNo ratings yet

- 01 Cir 0000047527 11221 29Document7 pages01 Cir 0000047527 11221 29Jane GutierrezNo ratings yet

- Myocardial Infarction, Acute Case FileDocument7 pagesMyocardial Infarction, Acute Case Filehttps://medical-phd.blogspot.comNo ratings yet

- Yeshwant 2018Document16 pagesYeshwant 2018StevenSteveIIINo ratings yet

- Nejmcps 2116690Document8 pagesNejmcps 2116690Luis MadrigalNo ratings yet

- Cardiac MR With Late Gadolinium Enhancement in Acute Myocarditis With Preserved Systolic FunctionDocument11 pagesCardiac MR With Late Gadolinium Enhancement in Acute Myocarditis With Preserved Systolic FunctionAnca NegrilaNo ratings yet

- Acute PericarditisDocument7 pagesAcute PericarditisMirza AlfiansyahNo ratings yet

- Acute Myocarditis Mimicking ST-elevation Myocardial Infarction: A Diagnostic Challenge For Frontline CliniciansDocument3 pagesAcute Myocarditis Mimicking ST-elevation Myocardial Infarction: A Diagnostic Challenge For Frontline CliniciansZazaNo ratings yet

- ContentServer AspDocument9 pagesContentServer Aspganda gandaNo ratings yet

- Manage Acute Myocardial InfarctionDocument96 pagesManage Acute Myocardial InfarctionSoze KeyserNo ratings yet

- G7pfe7Document5 pagesG7pfe7Carmen Cuadros BeigesNo ratings yet

- Survival of A Neurologically Intact Patient With Subarachnoid Hemorrhage and Cardiopulmonary ArrestDocument4 pagesSurvival of A Neurologically Intact Patient With Subarachnoid Hemorrhage and Cardiopulmonary ArrestDino RatnamNo ratings yet

- ECG Diagnosis: Acute Myocardial Infarction in A Ventricular-Paced RhythmDocument3 pagesECG Diagnosis: Acute Myocardial Infarction in A Ventricular-Paced RhythmFlora Eka HeinzendorfNo ratings yet

- 10 Relato de Caso Acute CoronaryDocument4 pages10 Relato de Caso Acute CoronaryAsis FitrianaNo ratings yet

- 2001 Noninvasive Tests in Patients With Stable Coronary Artery DiseaseDocument6 pages2001 Noninvasive Tests in Patients With Stable Coronary Artery DiseaseAlma EscobarNo ratings yet

- Lee Et Al 2023 Concurrent Acute Ischemic Stroke and Myocardial Infarction Associated With Atrial FibrillationDocument5 pagesLee Et Al 2023 Concurrent Acute Ischemic Stroke and Myocardial Infarction Associated With Atrial FibrillationBlackswannnNo ratings yet

- 2021 Girl Who Cried Wolf A Case of PrinzmetalDocument5 pages2021 Girl Who Cried Wolf A Case of PrinzmetalFariz DwikyNo ratings yet

- Acute Myocardial Infarction and Heart FailureDocument5 pagesAcute Myocardial Infarction and Heart FailureWirawan PrabowoNo ratings yet

- Bezold JarischDocument6 pagesBezold Jarischbecky_meloniNo ratings yet

- Serial T-Wave Changes in A Patient With Chest PainDocument2 pagesSerial T-Wave Changes in A Patient With Chest PainsunhaolanNo ratings yet

- CVS Physio Case Files p1Document4 pagesCVS Physio Case Files p1dawnparkNo ratings yet

- Predicting Outcomes in Acute Coronary Syndrome Using Biochemical MarkersDocument9 pagesPredicting Outcomes in Acute Coronary Syndrome Using Biochemical MarkersSitti Monica A. AmbonNo ratings yet

- A Dangerous Twist of The T Wave A Case of WellenDocument5 pagesA Dangerous Twist of The T Wave A Case of WellenJayden WaveNo ratings yet

- Does This Dyspneic Patient in The Emergency Department Have Congestive Heart Failure?Document13 pagesDoes This Dyspneic Patient in The Emergency Department Have Congestive Heart Failure?Jorge MéndezNo ratings yet

- EE Pac Con FADocument6 pagesEE Pac Con FAGuillermo CenturionNo ratings yet

- Lin 2009Document7 pagesLin 2009Nur Syamsiah MNo ratings yet

- Improving Patient CareDocument10 pagesImproving Patient CarebrookswalshNo ratings yet

- Pak Jaenal - Askep Acs - Scu - PPTDocument37 pagesPak Jaenal - Askep Acs - Scu - PPTDilaNo ratings yet

- Elevação de V1 A V3 No BrugadaDocument8 pagesElevação de V1 A V3 No BrugadaNITACORDEIRONo ratings yet

- Simulation Acute Coronary Syndrome (Learner)Document2 pagesSimulation Acute Coronary Syndrome (Learner)Wanda Nowell0% (1)

- Leadership Excellence Through Critical Care InsightDocument16 pagesLeadership Excellence Through Critical Care InsightJuan Carlos LopezNo ratings yet

- Belardi Nell I 1999Document11 pagesBelardi Nell I 1999LidiyahNo ratings yet

- 2017 17 4 148 150 EngDocument3 pages2017 17 4 148 150 Engخالد العيلNo ratings yet

- Case Reports AbstractsDocument7 pagesCase Reports AbstractsNovie AstiniNo ratings yet

- Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy Simulating An Acute Coronary SyndromeDocument5 pagesHypertrophic Cardiomyopathy Simulating An Acute Coronary SyndromeIJAR JOURNALNo ratings yet

- The Challenge of Diagnosing Psoas Abscess: Case ReportDocument4 pagesThe Challenge of Diagnosing Psoas Abscess: Case ReportNataliaMaedyNo ratings yet

- Prehospitalresearch - Eu-Case Study 5 Antero-Lateral STEMIDocument8 pagesPrehospitalresearch - Eu-Case Study 5 Antero-Lateral STEMIsultan almehmmadiNo ratings yet

- April 2018 1522659614 97Document2 pagesApril 2018 1522659614 97Rohit ThakareNo ratings yet

- Acute Meningitis Complicated by Transverse Myelitis: Case ReportDocument2 pagesAcute Meningitis Complicated by Transverse Myelitis: Case ReportSeptian TheaNo ratings yet

- Penanganan Ima1Document81 pagesPenanganan Ima1Debbi AnggrainiNo ratings yet

- Artículo Deep Brain Stimulation For Phantom Limb PainDocument6 pagesArtículo Deep Brain Stimulation For Phantom Limb Paindaniela olayaNo ratings yet

- A Rare Cause of Chest Pain: Spontaneous Sternum Fracture: Ibrahim Sarbay, Halil DoganDocument5 pagesA Rare Cause of Chest Pain: Spontaneous Sternum Fracture: Ibrahim Sarbay, Halil DoganYuliSsTiaNo ratings yet

- Mitral Valve Prolapse Syndrome With Coronary Artery Spasm: Possible Cause of Recurrent Ventricular TachyarrhythmiaDocument3 pagesMitral Valve Prolapse Syndrome With Coronary Artery Spasm: Possible Cause of Recurrent Ventricular TachyarrhythmiaDewina Dyani RosariNo ratings yet

- An Important Cause of Wide Complex Tachycardia: Case PresentationDocument2 pagesAn Important Cause of Wide Complex Tachycardia: Case PresentationLuis Fernando Morales JuradoNo ratings yet

- The Trigemino-Cardiac Reflex: Is Treatment With Atropine Still Justified?Document2 pagesThe Trigemino-Cardiac Reflex: Is Treatment With Atropine Still Justified?DinNo ratings yet

- 1Document4 pages1Mirla Castellanos JuradoNo ratings yet

- Pi Is 0002934312004901Document2 pagesPi Is 0002934312004901MuliaDharmaSaputraHutapeaNo ratings yet

- Management of Acute Coronary SyndromeDocument73 pagesManagement of Acute Coronary SyndromeSantosh NaliathNo ratings yet

- Arrhythmogenic Right Ventricular Cardiomyopathy in A WeimaranerDocument5 pagesArrhythmogenic Right Ventricular Cardiomyopathy in A WeimaranerEmilia AmmariNo ratings yet

- Jama BuenoDocument7 pagesJama BuenoNoel Saúl Argüello SánchezNo ratings yet

- Stress Related Takotsubo Cardiomyopathy: A Case ReportDocument6 pagesStress Related Takotsubo Cardiomyopathy: A Case ReportSabrina JonesNo ratings yet

- Coronary Vasomotion AbnormalitiesFrom EverandCoronary Vasomotion AbnormalitiesHiroaki ShimokawaNo ratings yet

- Vaccination and Autoimmune Disease: What Is The Evidence?: ReviewDocument8 pagesVaccination and Autoimmune Disease: What Is The Evidence?: Reviewtito7227No ratings yet

- Triage Assessment SlipDocument1 pageTriage Assessment SlipJm unite100% (1)

- COVID-19 Quarantine and Isolation GuidelinesDocument10 pagesCOVID-19 Quarantine and Isolation GuidelinesFraulein LiNo ratings yet

- Review Cram SheetDocument57 pagesReview Cram Sheetjim j100% (1)

- 5 6217311614496932277Document81 pages5 6217311614496932277DR.SANJOY GHOSHNo ratings yet

- Scars PDFDocument9 pagesScars PDFMichaely NataliNo ratings yet

- DLT211Document5 pagesDLT211Qudus SilmanNo ratings yet

- CHAPTER 7: Phar Macology, Medical Diagnostic Techno Logy, Treatment An D Life SupportDocument118 pagesCHAPTER 7: Phar Macology, Medical Diagnostic Techno Logy, Treatment An D Life SupportChristine LehmannNo ratings yet

- Diagnostic Criteria For 298Document1 pageDiagnostic Criteria For 298Pradeep KumarNo ratings yet

- List of Zoonotic Diseases and Their ReservoirsDocument1 pageList of Zoonotic Diseases and Their ReservoirsHuyen J. DinhNo ratings yet

- Reis Da Silva 2023 Falls Assessment and Prevention in The Nursing Home and CommunityDocument5 pagesReis Da Silva 2023 Falls Assessment and Prevention in The Nursing Home and CommunityTiago SilvaNo ratings yet

- Best Practice & Research Clinical Obstetrics and GynaecologyDocument12 pagesBest Practice & Research Clinical Obstetrics and GynaecologyGrit WingsNo ratings yet

- Breast Pain - UpToDateDocument22 pagesBreast Pain - UpToDateSalo MarianoNo ratings yet

- Prince Price Alide Price Printer Sr. No Books Author Edition QT Y KinesiologyDocument9 pagesPrince Price Alide Price Printer Sr. No Books Author Edition QT Y KinesiologyNaveed AkhterNo ratings yet

- Asbestosis StatPearls NCBIBookshelfDocument11 pagesAsbestosis StatPearls NCBIBookshelfAjeng RahmawatiNo ratings yet

- Ch2012.Decompressive Craniectomy - Operative TechniqueDocument22 pagesCh2012.Decompressive Craniectomy - Operative TechniqueKysy CodonNo ratings yet

- Family Medicine COPCDocument20 pagesFamily Medicine COPCrachellesliedeleonNo ratings yet

- Medical TerminologyDocument4 pagesMedical Terminologyflordeliza magallanesNo ratings yet

- Device Related Error in Patient Controlled.17Document6 pagesDevice Related Error in Patient Controlled.17Ali ÖzdemirNo ratings yet

- Medtronic Circular StaplerDocument4 pagesMedtronic Circular StaplerClaire SongNo ratings yet

- Chest Tube Thoracostomy ProcedureDocument17 pagesChest Tube Thoracostomy ProcedureJill Catherine CabanaNo ratings yet

- Sleep Pattern DisturbanceDocument4 pagesSleep Pattern DisturbanceVirusNo ratings yet

- Editing Exercise: Improving Grammar, Punctuation and FormalityDocument3 pagesEditing Exercise: Improving Grammar, Punctuation and FormalityMaiElGebaliNo ratings yet

- History of Falls Care PlanDocument1 pageHistory of Falls Care PlanJoax Wayne SanchezNo ratings yet

- RNTCP Training Course For Program Manager Module 1 To 4Document208 pagesRNTCP Training Course For Program Manager Module 1 To 4Ashis DaskanungoNo ratings yet

- Treatment of Angular Cheilitis A Narrative Review and AuthorsDocument9 pagesTreatment of Angular Cheilitis A Narrative Review and AuthorsElizabeth SihiteNo ratings yet

- Krok 1 2003Document22 pagesKrok 1 2003xacan12No ratings yet

- Bds 2nd YearDocument26 pagesBds 2nd YearGauravNo ratings yet

- Dental Public HealthDocument2 pagesDental Public HealthKhairumi Dhiya'an AbshariNo ratings yet

- SL No Tast Name PriceDocument6 pagesSL No Tast Name Pricesmrutiranjan paridaNo ratings yet