Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Biocel Informe

Uploaded by

Isidora Oyarzún IcónomosOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Biocel Informe

Uploaded by

Isidora Oyarzún IcónomosCopyright:

Available Formats

bs_bs_banner

International Journal of Nursing Practice 2014; ••: ••–••

CLINICAL PAPER

Factors contributing to malnutrition in patients

with Parkinson’s disease

Sung R Kim RN PhD

Assistant Professor, College of Nursing, Chonbuk National University, Jeonju, Korea

Sun J Chung MD PhD

Associate Professor, Department of Neurology, Asan Medical Center, University of Ulsan College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

Sung-Hee Yoo RN PhD

Assistant Professor, College of Nursing, Chonnam National University, Gwangju, Korea

Accepted for publication November 2014

Kim SR, Chung SJ, Yoo SH. International Journal of Nursing Practice 2014; ••: ••–••

Factors contributing to malnutrition in patients with Parkinson’s disease

Our objective in this study was to evaluate the nutritional status and to identify clinical, psychosocial, and nutritional

factors contributing to malnutrition in Korean patients with Parkinson’s disease. We used a descriptive, cross-sectional

study design. Of 102 enrolled patients, 26 (25.5%) were malnourished and 27 (26.5%) were at risk of malnutrition based

on Mini-Nutritional Assessment scores. Malnutrition was related to activity of daily living score, Hoehn and Yahr stage,

duration of levodopa therapy, Beck Depression Inventory and Spielberger’s Anxiety Inventory scores, body weight, body

weight at onset of Parkinson’s disease, and body mass index. On multiple logistic regression analysis, anxiety score,

duration of levodopa therapy, body weight at onset of Parkinson’s disease, and loss of body weight were significant factors

predicting malnutrition in Parkinson’s disease patients. Therefore, nutritional assessment, including psychological evalu-

ation, is required for Parkinson’s disease patients to facilitate interdisciplinary nutritional intervention for malnourished

patients.

Key words: malnutrition, nutritional status, Parkinson’s disorder.

INTRODUCTION Malnutrition is generally defined as an underweight

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is the second most common BMI less than 18.50 kg/m2 in adults, according to the

neurodegenerative disorder characterized by dopaminer- WHO classification.4 Previous studies have shown that PD

gic neuronal loss.1 Patients with PD experience not only patients have a lower body weight and body mass index

neurological motor symptoms including tremor, rigidity (BMI) than healthy controls5–7 and also are at increased

and bradykinesia but also health-related problems includ- risk of developing malnutrition than age-matched con-

ing depression, dementia, fatigue and constipation.2 Mal- trols.8 The prevalence of malnutrition in PD patients has

nutrition has also been recognized as an important problem been reported to range from 0 to 24%, and the malnutri-

in PD patients.2,3 tion risk from 3 to 60% based on various nutritional

parameters and definitions.8–11 Although the true extent of

Correspondence: Sung-Hee Yoo, College of Nursing, Chonnam malnutrition in the PD population remains unclear, a not

National University, 160 Baekseo-ro, Dong-gu, Gwangju 501-746, inconsiderable proportion of patients have a nutritional

Korea. Email: shyoo@jnu.ac.kr problem.

doi:10.1111/ijn.12377 © 2014 Wiley Publishing Asia Pty Ltd

2 SR Kim et al.

Nutritional assessment can be performed by assessing METHODS

hematologic parameters such as albumin or prealbumin Design

levels, anthropometric parameters such as body mass This was an observational study with a cross-sectional

index (BMI) and body weight, and using nutritional assess- design.

ment tools to assess dietary habits and general status.12

The mini-nutritional assessment (MNA) tool is one of Participants

the most widely used tools for nutritional assessment in Subjects were recruited from a single tertiary university

clinical and research settings, because it can evaluate hospital in Seoul, Korea, and convenience sampling was

neuropsychological health and morbidity as well as used to select subjects.

anthropometric parameters and dietary habits, and has We included patients (i) who were over 20 years of

been validated in elderly patients.13 Therefore, nutritional age, (ii) who had PD based on the United Kingdom Par-

assessment using this validated tool is essential for PD kinson’s Disease Society Brain Bank criteria as the primary

patients. diagnosis,24 and (iii) who had no other major health prob-

Several factors might contribute to the high prevalence lems that could influence nutritional status such as active

of malnutrition in PD patients. The first factor is related cancer, infection, inflammation, liver failure, or renal

to motor symptoms. Bradykinesia, rigidity and gait dis- failure. We excluded patients with atypical Parkinsonism

turbance cause some patients to experience difficulty in or secondary Parkinsonism. We enrolled a total of 102

performing the activities of daily living (ADL) such as patients in the current study.

shopping, preparing and eating or swallowing food inde-

pendently11,14 These types of disabilities might also be Measurement of nutritional status

caused by levodopa-related motor complications such Mini-Nutritional Assessment (MNA)

as dyskinesia.7,8,15 The second factor is related to psycho- Nutritional status was measured using the MNA tool.25

social and cognitive factors. Depression, anxiety and The MNA is widely used to assess nutritional status and

dementia have been found to contribute to lowered food has been validated in various settings,13 including in

intake and weight loss in the elderly,16–18 and such symp- elderly Korean patients.26 MNA is highly sensitive (96%)

toms are present at a higher incidence in PD patients than and specific (98%).13,27 The MNA is an 18-item question-

in controls.19,20 The last factor is related to medications naire comprising anthropometric measurements, general

that are used to manage PD, which can have side effects status including swallowing function, dietary habits and

such as nausea, vomiting, loss of appetite and change of self-perception of health and nutrition states.13 MNA

taste.8,21–23 scores range from 0 to 30 points; a higher score indicates

Although multiple factors might contribute to malnu- a healthier nutritional status. Based on the final MNA

trition in PD patients, only a few of these factors have scores, we classified the nutritional status of subjects

been examined in previous studies.5,7,9,10,23 Therefore, a ‘good’ (≥ 24 points), at ‘risk of malnutrition’ (17–23.5

comprehensive study examining all potential factors is points), or ‘malnourished’ (< 17 points).13,25 In this study,

needed to identity factors that significantly affect malnu- we defined patients with a good nutritional status and

trition in PD patients. Because malnutrition leads to those at risk of malnutrition into the non-malnutrition

poorer quality of life and worse health outcomes, such as group, whereas malnourished patients were defined to the

higher mortality and prolonged length of hospital stay,8 malnutrition group.

evaluation of the nutritional status of PD patients and

determination of the factors that contribute to malnutri- Beck Depression Inventory (BDI)

tion in PD patients are particularly relevant. Depression was measured using the Beck Depression

Inventory (BDI) with self-rating scales,28,29 which is one of

the most commonly used tools for assessment of depres-

Aims sion.30 Its reliability and validity have been validated in

Our aims in the current study were to describe the nutri- Korean patients.30,31 The BDI includes 21 questions and

tional status of Korean patients with PD and to identify BDI scores range from 0 to 63. Higher scores indicate

clinical, psychosocial and nutritional factors that predicted greater depression. Cronbach’s alpha value for the BDI

malnutrition in these patients. was 0.90 in the current study.

© 2014 Wiley Publishing Asia Pty Ltd

Malnutrition in patients with PD 3

Spielberger’s Anxiety Inventory (SAI) Data collection

Anxiety was measured using the Korean version of Between March and September 2012, we enrolled sub-

SAI.32,33 This is a well-established scale that has been used jects who provided written informed consent. Subjects

extensively in research and clinical practice.34,35 SAI were informed of the aims and procedures of the current

includes 20 questions and SAI scores range from 20 to 80. study by clinical nurse specialists. Patients who agreed to

Higher scores indicate greater anxiety. Cronbach’s alpha face-to-face interviews had their body weight and BMI

value for the SAI was 0.95 in the current study. measured and were administered a structured question-

naire that they completed together with a spouse or family

member. Following the interviews, we confirmed patient

Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE)

Korean version of the MMSE (K-MMSE) was used to information using medical records.

measure the cognitive function of patients.36 Sensitivity

for detecting dementia with the K-MMSE has been Analysis

reported to range from 0.70 to 0.83.37 K-MMSE scores Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS version

range from 0 to 30. Higher scores indicate greater cogni- 20.0 (IBM SPSS Statistics, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). All

tive function. data are expressed as numbers (percentages), means ± SD

(standard deviations), or medians (ranges). To compare

clinical, psychosocial and nutritional characteristics

Other variables between the malnutrition and non-malnutrition group,

We examined various clinical and nutritional variables

we used the chi-square test, t-test or Mann–Whitney

using a structured questionnaire. The clinical characteris-

U-test as appropriate, and we used the Kolmogorov–

tics of age of onset of PD, disease duration, duration of

Smirnov test to analyze the normality of continuous vari-

levodopa therapy, daily levodopa equivalent dose (LED),

ables. To identify independent predictors of malnutrition,

presence of motor fluctuation and dyskinesia, Hoehn and

we performed multiple logistic regression analysis and

Yahr stage, and the Schwab and England ADL score were

calculated odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals

assessed.

(CIs). Hosmer–Lemeshow test was used to assess

We assessed nutritional characteristics in detail includ-

goodness-of-fit. A two-tailed P value less than 0.05 was

ing MNA; anthropometric parameters such as current

considered statistically significant.

body weight, body weight at onset of PD, weight loss and

body mass index (BMI); biochemical parameters such as

serum albumin and total protein; and presence of symp- Ethical considerations

toms potentially affecting oral intake by PD medication The current study was approved by the Institutional

such as constipation, nausea and vomiting, and dyspepsia. Review Board (IRB) of Asan Medical Center in Korea.

Current body weight and BMI were measured using an We obtained written informed consent from all subjects

automatic fatness measuring system (G-tec, G-tec Inter- or their legal representatives. Subjects were allowed to

national, Uijungbu, South Korea). Subjects were assigned voluntarily withdraw their informed consent and their

to one of four categories based on BMI values according to personal data were kept strictly confidential throughout

WHO recommendations for Asian populations.38 Weight the study.

loss was calculated as the difference between weight at

onset of PD and current weight based on a review of RESULTS

electronic medical records. In addition, serum protein Demographic, clinical and

and albumin levels were assessed as biochemical param- psychosocial characteristics

eters. Serum total protein was classified based on a cut-off Of the 102 patients included in this study, 57 (55.9%)

of 6.2 g/dL and serum albumin on a cut-off of 3.5 g/ were female. Age ranged from 31 to 81 years

dL.39 We defined constipation as bowel action less than (mean ± SD, 61.2 ± 10.1 years), and the median disease

three times weekly,40 whereas we defined dyspepsia as duration was 9 years (range, 1–24 years). Median Hoehn

gastrointestinal discomfort after taking PD medication and Yahr stage was 2 (range, 0–5). Mean K-MMSE, BDI,

based on subjective sensations of bloating, burning and gas and SAI scores were 25.7 ± 3.7, 14.7 ± 10.8, and

in the bowels.22 44.6 ± 11.1, respectively.

© 2014 Wiley Publishing Asia Pty Ltd

4 SR Kim et al.

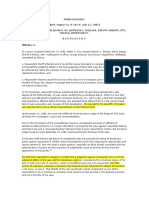

Nutritional status and characteristics In the malnutrition group, the age of onset of PD was

Nutritional characteristics are summarized in detail in significantly higher than that in the non-malnutrition

Table 1. Twenty-six (25.5%) of the 102 patients were group (55.6 ± 9.5 years vs. 49.6 ± 11.8 years, respec-

categorized as malnourished whereas 27 (26.5%) patients tively) (P = 0.020), and Schwab and England ADL

were considered at risk of malnutrition based on the score was significantly lower in the malnutrition group

MNA results. Fifty-eight (56.8%) patients had experi- (P < 0.001). However, the duration of levodopa therapy

enced weight loss. Mean BMI of all PD patients was was significantly shorter in the malnutrition group

23.2 ± 3.7 kg/m2 and seven patients (6.9%) were under- (P = 0.038). Hoehn and Yahr stage was significantly cor-

weight (BMI < 18.5 kg/m2). Mean serum total protein related with the degree of malnutrition according to MNA

and albumin levels were 6.6 ± 0.5 and 4.0 ± 0.4 g/dl score (P = 0.017).

(range, 5.3–7.7 g/dl and 3.0–5.9 g/dl), respectively. BDI and SAI scores were significantly higher in the

malnutrition group than the non-malnutrition group

Demographic, clinical, psychosocial, (P = 0.009 and P < 0.001, respectively).

and nutritional characteristics Among nutritional parameters, body weight, body

related to malnutrition weight at disease onset, and BMI were significantly lower

Differences in demographic, clinical, psychosocial, and in the malnutrition group than the non-malnutrition

nutritional characteristics between the two groups are group (P < 0.001, P = 0.009, and P < 0.001, respec-

presented in Table 2. tively), whereas weight loss was higher in the malnutri-

tion group than the non-malnutrition group (P < 0.001).

Table 1 Nutritional characteristics of PD patients (n = 102)

Moreover, we found a significant correlation between

malnutrition and nausea and vomiting (P = 0.048) and

Variables n (%) or Range

dyspepsia (P = 0.001) related to anti-PD medication.

mean ± SD

However, clinical factors such as sex, age, disease dura-

tion, daily levodopa equivalent dose (LED), motor fluc-

MNA 21.4 ± 6.2 4.5–29.0

Good status (≥ 24) 49 (48.0%)

tuation, dyskinesia, K-MMSE score, and levels of visceral

Risk of malnutrition (17–23.5) 27 (26.5%) proteins such as serum total protein and albumin were not

Malnutrition (< 17) 26 (25.5%) related to malnutrition.

Body weight (kg) 58.7 ± 9.4 40.5–83.0

Body weight at disease onset (kg) 61.7 ± 9.4 42.0–93.8 Factors predicting malnutrition in

Weight loss 58 (56.9%) patients with PD

7.2 ± 4.7 1.0–20.0 Multiple logistic regression analysis revealed that anxiety

BMI (kg/m2) 23.2 ± 3.7 14.4–34.2 score (OR = 1.124, 95% CI: 1.003–1.261, P = 0.044),

< 18.5 7 (6.9%) duration of levodopa therapy (OR = 0.666, 95% CI:

18.5 ≤ BMI < 23 44 (43.1%) 0.460–0.962, P = 0.030), body weight at onset of PD

23 ≤ BMI < 27.5 40 (39.2%) (OR = 0.709, 95% CI: 0.544–0.925, P = 0.011), and

≥ 27.5 11 (10.8%)

weight loss (OR = 2.972, 95% CI: 1.366–6.464,

Protein (g/dl), (n = 98) 6.6 ± 0.5 5.3–7.7

P = 0.006) were significant factors predicting malnutri-

< 6.2 21 (21.4%)

≥ 6.2 77 (78.6%)

tion (Table 3).

Albumin (g/dl), (n = 98) 4.0 ± 0.4 3.0–5.9

< 3.5 8 (7.8%) DISCUSSION

≥ 3.5 90 (88.2%) The results of our study indicate that the prevalence of

Constipation 55 (53.9%) malnourishment in patients with PD is high, and that the

Nausea & vomiting 12 (11.8%) psychological factor of anxiety, as well as duration of

Dyspepsia 16 (15.7%) levodopa treatment, initial weight at diagnosis, and

weight change after PD onset are independent predictors

PD, Parkinson’s disease; SD, standard deviation; MNA, mini- of malnutrition. A strength of our study is that we

nutritional assessment; LED, levodopa equivalent dose; K-MMSE, examined all potential contributing factors, including

Korean mini mental status examination; BMI, body mass index. nutritional symptoms related with anti-PD medication,

© 2014 Wiley Publishing Asia Pty Ltd

Malnutrition in patients with PD 5

Table 2 Comparison of clinical, psychosocial, and nutritional characteristics between the malnutrition group and the non-malnutrition

group

Variables Malnutrition Non-malnutrition t or z or χ2 P value

(n = 26) (n = 76)

Clinical characteristics

Sex (Female) 18 (69.2%) 39 (51.3%) 0.169 0.112

Age (years) 64.5 ± 8.6 60.1 ± 10.4 1.968 0.052

Age at onset (years) 55.6 ± 9.5 49.6 ± 11.8 2.360 0.020*

Disease duration (years) 8.7 ± 5.3 10.6 ± 6.2 −1.338 0.114†

Hoehn & Yahr stage 13.463 0.017*

0 0 2 (2.6%)

1 3 (11.5%) 5 (6.6%)

2 10 (38.5%) 46 (60.5%)

3 5 (19.2%) 16 (21.1%)

4 5 (19.2%) 7 (9.2%)

5 3 (11.5%) 0

ADL (%) 63.9 ± 26.1 84.7 ± 11.9 −3.930 < 0.001**

Duration of levodopa Therapy (years) 6.5 ± 4.4 9.3 ± 6.1 −2.468 0.038†*

LED (mg/day) 614.1 ± 311.9 788.5 ± 497.7 −1.643 0.384†

Motor fluctuation (n = 25) (n = 76) 0.849 0.654

No 9 (36.0%) 22 (28.9%)

Yes, but not disabling 8 (32.0%) 32 (42.1%)

Yes, disabling 8 (32.0%) 22 (28.9%)

Dyskinesia (n = 25) (n = 76) 0.004 0.998

No 9 (36.0%) 27 (35.5%)

Yes, but not disabling 11 (44.0%) 34 (44.7%)

Yes, disabling 5 (20.0%) 15 (19.7%)

K-MMSE 24.4 ± 3.6 26.1 ± 3.6 −2.036 0.083†

Psychosocial characteristics

Depression 23.7 ± 10.6 11.6 ± 9.1 4.682 0.009†*

Anxiety 52.3 ± 12.3 42.2 ± 9.6 3.654 < 0.001**

Nutritional characteristics

Body weight (kg) 50.8 ± 6.3 61.4 ± 8.8 −5.629 < 0.001**

Body weight at PD onset (kg) 57.5 ± 8.5 63.1 ± 9.3 −2.655 0.009*

BMI (kg/m2) 20.2 ± 2.6 24.3 ± 3.4 −5.612 < 0 .001**

< 18.5 6 (23.1%) 1 (1.3%) 27.951 < 0.001**

18.5 ≤ BMI < 23 17 (65.4%) 27 (35.5%)

23 ≤ BMI < 27.5 3 (11.5%) 37 (48.7%)

≥ 27.5 0 11 (14.5%)

Weight loss (kg) 22 (84.6%) 36 (47.4%) 10.957 0.001*

7.4 ± 5.0 3.1 ± 4.6 3.992 < 0.001†**

Protein (g/dl) 6.6 ± 0.4 6.6 ± 0.5 −0.161 0.873

Albumin (g/dl) 4.0 ± 0.6 3.9 ± 0.3 0.629 0.401†

Constipation 14 (53.8%) 41 (53.9%) 0.000 0.993

Nausea & vomiting 6 (23.1%) 6 (7.9%) 4.302 0.048*

Dyspepsia 10 (38.5%) 6 (7.9%) 13.686 0.001**

* P < 0.05; ** P < 0.001; †Mann–Whitney U-test. ADL, activities of daily living; LED, levodopa equivalent dose; K-MMSE, Korean-

mini mental status examination; BMI, body mass index.

© 2014 Wiley Publishing Asia Pty Ltd

6 SR Kim et al.

Table 3 Predictors of malnutrition in PD patients those of the current study;6,7,23 further studies are needed

to address this issue. Our results suggest that disease

Variables Odds 95% CI P value severity might be a more important factor than disease

ratio duration for predicting malnutrition in PD patients.

It is well known that depression and anxiety are

Anxiety 1.124 1.003–1.261 0.044* psychological factors associated with malnutrition,16,18

Duration of levodopa therapy 0.666 0.460–0.962 0.030* consistent with our results. In particular, we found that

Body weight at onset of PD 0.709 0.544–0.925 0.011*

anxiety was an independent predictor of malnutrition

Weight loss 2.972 1.366–6.464 0.006*

after adjusting for all other factors in our study. Anxiety is

a frequent emotional symptom in PD patients and is asso-

* P < 0.05, Hosmer–Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test showed

ciated with motor symptoms, such as severe gait prob-

χ2 = 1.56 (P = .980). PD, Parkinson’s disease; CI, confidence

lems, dyskinesia, and off symptoms.46 Anxiety might

interval.

worsen nutritional status through exacerbated neurologic

symptoms and might affect appetite and food intake. Until

clinical and psychological factors, and various nutritional recently, medication was the main treatment strategy in

parameters, to determine independent predictors of patients with high levels of anxiety.47 However, cognitive

malnutrition. behavior therapy and exercise are gaining popularity as

The prevalence of malnutrition was 25.5% and the risk effective approaches to treat anxiety in PD patients.48,49

of malnutrition was 26.5%, indicating that more than half Thus, a multi-dimensional intervention strategy might

of the subjects (52%) had nutritional problems. This alleviate anxiety and improve nutritional status in PD

result is largely consistent with those reported in previous patients.

studies based on MNA assessment.8,23 Our results indicate Other nutritional parameters were also significantly

that PD patients are therefore more likely to be under- different between the malnutrition and non-malnutrition

nourished than hemodialysis patients (56.5%)41 or groups. We used albumin as a biochemical parameter to

patients with other chronic diseases, such as chronic investigate cross-sectional nutritional state in PD patients,

obstructive pulmonary disease (30.7%).42 This result not temporal changes, because albumin is known to be a

highlights the necessity of performed nutritional assess- good predictor of poor clinical outcomes in various dis-

ments in all PD patients, given that patients at risk of eases50,51 and has a longer half-life than prealbumin or

malnutrition might become malnourished.43 transferrin. However, the albumin results did not reflect

We found that although K-MMSE scores were lower the MNA results in our study. This was consistent with

in the malnutrition group than in the non-malnutrition previous findings that the serum albumin was not a reli-

group (24.4 ± 3.6 vs. 26.1 ± 3.6, respectively), these able indicator for nutritional assessment in patients with

scores were not statistically correlated with malnutrition, chronic diseases.52 In addition, we also measured the BMI

a finding similar to that reported in previous studies.7,8 as an anthropometric parameter, but the proportion of

However, because cognitive function has been shown to underweight individuals according to the WHO BMI clas-

be associated with malnutrition in other populations,44 sification showed a discrepancy with the incidence of mal-

including Alzheimer’s disease patients,45 further studies nutrition according to the MNA. It was also consistent

are warranted to elucidate the correlation between cog- with previous findings performed in elderly patients and

nitive function and nutritional status in patients with PD. patients with cancer.53–55 We believe that these results

Because PD is a neurodegenerative disorder, disease might be due to each nutritional parameter (such as

duration and disease severity are positively associated with anthropometric, biochemical, and global assessment

each other, and both might be negatively associated with tools) reflecting a different clinical process.56 Neverthe-

nutritional status. We found an association between mal- less, the MNA considers various nutritional parameters

nutrition and a higher Hoehn and Yahr stage, as described including food intake by appetite or swallowing difficulty,

in previous studies,6,8 but no association between malnu- anthropometric measurements including weight loss, and

trition and PD duration. It is therefore unclear whether physical and mental functions, and malnutrition and non-

PD duration is associated with malnutrition, because pre- malnutrition groups classified by the MNA showed a dif-

vious studies have reported findings that conflict with ference in clinical and psychological factors reported in

© 2014 Wiley Publishing Asia Pty Ltd

Malnutrition in patients with PD 7

previous studies, symptoms affecting oral intake, and 6 Van der Marck MA, Dicke HC, Uc EY et al. Body mass

other nutritional factors excluding biochemical param- index in Parkinson’s disease: A meta-analysis. Parkinsonism

eters. Therefore, we believe that the MNA is a useful tool and Related Disorders 2012; 18: 263–267.

7 Jaafar AF, Gray WK, Porter B, Turnbull EJ, Walker RW.

for nutritional assessment in patients with PD as a chronic

A cross-sectional study of the nutritional status of

disease. community-dwelling people with idiopathic Parkinson’s

We recommend assessing the nutritional state of PD disease. BMC Neurology 2010; 10: 124.

patients using a validated tool and identifying risk factors 8 Sheard JM, Ash S, Silburn PA, Kerr GK. Prevalence of

for poor nutrition. Moreover, for patients at risk of mal- malnutrition in Parkinson’s disease: A systematic review.

nutrition, as well as those with malnutrition, various Nutrition Reviews 2011; 69: 520–532.

individual interventions such as diet modification and 9 Barichella M, Villa MC, Massarotto A et al. Mini nutritional

nutritional supplements, education, stress relief, regula- assessment in patients with Parkinson’s disease: Correlation

between worsening of the malnutrition and increasing

tion of symptoms affecting poor oral intake, and dietary

number of disease years. Nutritional Neuroscience 2008; 11:

consultation should be considered in both research set- 128–134.

tings and clinical practice. 10 Markus HS, Tomkins AM, Stern GM. Increased prevalence

of undernutrition in Parkinson’s disease and its relationship

CONCLUSIONS to clinical disease parameters. Journal of Neural Transmission

Our study revealed that more than half of patients with 1993; 5: 117–125.

PD had nutritional problems, and that anxiety, duration of 11 Miller M, Daniels L. Nutritional risk factors and dietary

levodopa therapy, body weight at onset of PD, and weight intake in older adults with Parkinson’s disease attending

loss were factors that contributed significantly to the community-based therapy groups. Australian Journal of

Nutrition and Dietetics 2000; 57: 152–158.

development of malnutrition in PD patients.

12 Charney P, Malone AM. ADA Pocket Guide to Nutrition Assess-

Therefore, appropriate nutritional assessment, includ- ment. Chicago, IL, USA: American Dietetic Association,

ing psychological evaluation, should be conducted regu- 2000.

larly in PD patients, and a multidisciplinary approach 13 Cereda E. Mini nutritional assessment. Current Opinion in

involving various nutritional interventions should be con- Clinical Nutrition and Metabolic Care 2012; 15: 29–41.

sidered for undernourished patients. 14 Pirlich M, Lochs H. Nutrition in the elderly. Best Practice and

Research. Clinical Gastroenterology 2001; 15: 869–884.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 15 Bachmann CG, Trenkwalder C. Body weight in patients

with Parkinson’s disease. Movement Disorders 2006; 21:

No research funding or any other financial support was

1824–1830.

received for this study. None of the authors have any 16 Cilan H, Sipahioglu MH, Oguzhan N et al. Association

conflicts of interest to declare. between depression, nutritional status, and inflammatory

markers in peritoneal dialysis patients. Renal Failure 2013;

REFERENCES 35: 17–22.

1 Nutt JG, Wooten GF. Clinical practice. Diagnosis and 17 Tamura BK, Bell CL, Masaki KH, Amella EJ. Factors asso-

initial management of Parkinson’s disease. New England ciated with weight loss, low BMI, and malnutrition among

Journal of Medicine 2005; 353: 1021–1027. nursing home patients: A systematic review of the litera-

2 Chaudhuri KR, Healy DG, Schapira AH, National Institute ture. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association 2013;

for Clinical Excellence. Non-motor symptoms of Parkin- 14: 649–655.

son’s disease: Diagnosis and management. Lancet Neurology 18 Kvamme JM, Grønli O, Florholmen J, Jacobsen BK. Risk of

2006; 5: 235–245. malnutrition is associated with mental health symptoms in

3 Barichella M, Cereda E, Pezzoli G. Major nutritional issues community living elderly men and women: The Tromsø

in the management of Parkinson’s disease. Movement Disor- Study. BMC Psychiatry 2011; 11: 112.

ders 2009; 24: 1881–1892. 19 Reijnders JS, Ehrt U, Weber WE, Aarsland D, Leentjens

4 World Health Organization. BMI classification. 2006. AF. A systematic review of prevalence studies of depression

Available from URL: http://apps.who.int/bmi/index.jsp in Parkinson’s disease. Movement Disorders 2008; 23: 183–

?introPage=intro_3.html Accessed 05 September 2014. 189.

5 Chen H, Zhang SM, Hernán MA, Willett WC, Ascherio A. 20 Uc EY, Struck LK, Rodnitzky RL, Zimmerman B, Dobson

Weight loss in Parkinson’s disease. Annals of Neurology 2003; J, Evans WJ. Predictors of weight loss in Parkinson’s

53: 676–679. disease. Movement Disorders 2006; 21: 930–936.

© 2014 Wiley Publishing Asia Pty Ltd

8 SR Kim et al.

21 Marcason W. What are the primary nutritional issues for a 37 Kang Y, Na DL, Hahn S. A validity study on the Korean

patient with Parkinson’s disease? Journal of the American Mini-Mental State Examination (K-MMSE) in dementia

Dietetic Association 2009; 109: 1316. patients. Journal of Korean Neurological Assocication 1997; 15:

22 Pfeiffer RF. Gastrointestinal dysfunction in Parkinson’s 300–308.

disease. Lancet Neurology 2003; 2: 107–116. 38 WHO Expert Consultation. Appropriate body-mass index

23 Wang G, Wan Y, Cheng Q et al. Malnutrition and associ- for Asian populations and its implications for policy and

ated factors in Chinese patients with Parkinson’s disease: intervention strategies. Lancet 2004; 363: 157–163.

Results from a pilot investigation. Parkinsonism and Related 39 Stosovic MD, Naumovic RT, Stanojevic M,

Disorders 2010; 16: 119–123. Simic-Ogrizovic SP, Jovanovic DB, Djukanovic LD. Could

24 Gibb WR, Lees AJ. The relevance of the lewy body to the the level of serum albumin be a method for assessing mal-

pathogenesis of idiopathic Parkinson’s disease. Journal of nutrition in hemodialysis patients? Nutrition in Clinical Prac-

Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry 1988; 51: 745–752. tice 2011; 26: 607–613.

25 Guigoz Y, Vellas B, Garry PJ. Mini nutritional assessment: 40 Chaudhuri KR, Martinez-Martin P, Brown RG et al. The

A practical assessment tool for grading the nutritional state metric properties of a novel non-motor symptoms scale for

of elderly patients. Facts and Research in Gerontology 1994; 4 Parkinson’s disease: Results from an international pilot

(Suppl. 2): 15–59. study. Movement Disorders 2007; 22: 1901–1911.

26 Kim EJ, Yoon YH, Kim WH, Lee KL, Park JM. The clinical 41 Tsai AC, Chang MZ. Long-form but not short-form Mini-

significance of the mini-nutritional assessment and the Nutritional Assessment is appropriate for grading nutri-

scored patient-generated subjective global assessment in tional risk of patients on hemodialysis: A cross-sectional

elderly patients with stroke. Annals of Rehabilitation Medicine study. International Journal of Nursing Studies 2011; 48:

2013; 37: 66–71. 1429–1435.

27 Vellas B, Guigoz Y, Garry PJ et al. The mini nutritional 42 Battaglia S, Spatafora M, Paglino G et al. Ageing and COPD

assessment (MNA) and its use in grading the nutritional affect different domains of nutritional status: The ECCE

state of elderly patients. Nutrition (Burbank, Los Angeles study. The European Respiratory Journal 2011; 37: 1340–

County, Calif.) 1999; 15: 116–122. 1345.

28 Beck AT. Depression: Clinical, Experimental and Theoretical 43 Yoo SH, Kim JS, Kwon SU et al. Undernutrition as a pre-

Aspects. New York, USA: Harper & Row, 1967. dictor of poor clinical outcomes in acute ischemic stroke

29 Lee YH, Song JY. A study of the reliability and the validity patients. Archives of Neurology 2008; 65: 39–43.

of the BDI, SDS, and MMPI-D scales. Korean Journal of 44 Fagerström C, Palmqvist R, Carlsson J, Hellström Y. Mal-

Clinical Psychology 1991; 10: 98–113. nutrition and cognitive impairment among people 60 years

30 Kil SY, Oh WO, Koo BJ, Suk MH. Relationship between of age and above living in regular housing and in special

depression and health-related quality of life in older Korean housing in Sweden: A population-based cohort study. Inter-

patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Journal national Journal of Nursing Studies 2011; 48: 863–871.

of Clinical Nursing 2010; 19: 1307–1314. 45 Gillette Guyonnet S, Abellan Van Kan G, Alix E et al. IANA

31 Jo SA, Park MH, Jo I, Ryu SH, Han C. Usefulness of Beck (International Academy on Nutrition and Aging) Expert

Depression Inventory (BDI) in the Korean elderly popula- Group: Weight loss and Alzheimer’s disease. The Journal of

tion. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 2007; 22: Nutrition, Health & Aging 2007; 11: 38–48.

218–223. 46 Leentjens AF, Dujardin K, Marsh L et al. Anxiety rating

32 Kim JT, Shin DK. A study based on the standardization of scales in Parkinson’s disease: Critique and recommenda-

the STAI for Korea. New Medical Journal 1978; 21: 69–75. tions. Movement Disorders 2008; 23: 2015–2025.

33 Spielberger CD. Anxiety; State-Trait Process: Stress and Anxiety. 47 Nègre-Pagès L, Grandjean H, Lapeyre-Mestre M et al.

New York, NY, USA: Joan Wiley & Sons, 1975. Anxious and depressive symptoms in Parkinson’s disease:

34 Ju HO, McElmurry BJ, Park CG, McCreary L, Kim M, The French cross-sectionnal DoPaMiP study. Movement Dis-

Kim EJ. Anxiety and uncertainty in Korean mothers of orders 2010; 25: 157–166.

children with febrile convulsion: Cross-sectional survey. 48 Pachana NA, Egan SJ, Laidlaw K et al. Clinical issues in the

Journal of Clinical Nursing 2011; 20: 1490–1497. treatment of anxiety and depression in older adults with

35 Luo YY. Effects of written plus oral information vs. oral Parkinson’s disease. Movement Disorders 2013; 28: 1930–

information alone on precolonoscopy anxiety. Journal of 1934.

Clinical Nursing 2013; 22: 817–827. 49 van der Kolk NM, King LA. Effects of exercise on mobility

36 Kwon YC, Park J. Korean version of mini-mental state in people with Parkinson’s disease. Movement Disorders 2013;

examination (MMSE-K) part I: Development of the test for 28: 1587–1596.

the elderly. Journal of the Korean Neuropsychiatric Association 50 Akdag I, Yilmaz Y, Kahvecioglu S et al. Clinical value of

1989; 28: 125–135. the malnutrition-inflammation-atherosclerosis syndrome

© 2014 Wiley Publishing Asia Pty Ltd

Malnutrition in patients with PD 9

for long-term prediction of cardiovascular mortality in cancer patients. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2008;

patients with end-stage renal disease: A 5-year prospec- 87: 1678–1685.

tive study. Nephron. Clinical Practice 2008; 108: c99– 54 Isenring E, Cross G, Daniels L, Kellett E, Koczwara B.

c105. Validity of the malnutrition screening tool as an effective

51 Di Fiore F, Lecleire S, Pop D et al. Baseline nutritional predictor of nutritional risk in oncology outpatients receiv-

status is predictive of response to treatment and survival ing chemotherapy. Supportive Care in Cancer 2006; 14: 1152–

in patients treated by definitive chemoradiotherapy for a 1156.

locally advanced esophageal cancer. The American Journal of 55 Slee A, Birch D, Stokoe D. A comparison of the malnutri-

Gastroenterology 2007; 102: 2557–2563. tion screening tools, MUST, MNA and bioelectrical imped-

52 Baron M, Hudson M, Steele R, Canadian Scleroderma ance assessment in frail older hospital patients. Clinical

Research Group (CSRG). Is serum albumin a marker of Nutrition. Published Online: May 02, 2014. doi: 10.1016/

malnutrition in chronic disease? The scleroderma paradigm. j.clnu.2014.04.013.

Journal of the American College of Nutrition 2010; 29: 144– 56 Covinsky KE, Covinsky MH, Palmer RM, Sehgal AR.

151. Serum albumin concentration and clinical assessments of

53 Laky B, Janda M, Cleghorn G, Obermair A. Comparison of nutritional status in hospitalized older people: Different

different nutritional assessments and body-composition sides of different coins? Journal of the American Geriatrics

measurements in detecting malnutrition among gynecologic Society 2002; 50: 631–637.

© 2014 Wiley Publishing Asia Pty Ltd

You might also like

- Sarc X Con 2Document6 pagesSarc X Con 2Samuel SilvaNo ratings yet

- Commentary: Nutritional Assessment and Length of Hospital StayDocument2 pagesCommentary: Nutritional Assessment and Length of Hospital StayNjeodoNo ratings yet

- Dietary Assessment Methods in Epidemiologic Studies: Epidemiology and HealthDocument8 pagesDietary Assessment Methods in Epidemiologic Studies: Epidemiology and Healthsuhada.akmalNo ratings yet

- VIKDAHL, 2014 - Weight Gain and Increased Central Obesity in The Early Phase ofDocument8 pagesVIKDAHL, 2014 - Weight Gain and Increased Central Obesity in The Early Phase ofAndressa BurgosNo ratings yet

- FNS 2015032316265641 PDFDocument9 pagesFNS 2015032316265641 PDFFelix EquinoNo ratings yet

- J Parenter Enteral Nutr - 2022 - Gressies - Nutrition Issues in The General Medical Ward Patient From General Screening ToDocument8 pagesJ Parenter Enteral Nutr - 2022 - Gressies - Nutrition Issues in The General Medical Ward Patient From General Screening ToRaiden EiNo ratings yet

- Comparison of Malnutrition and Malnutrition Screening Tools in Pediatric Oncology Patients A Cross-Sectional StudyDocument5 pagesComparison of Malnutrition and Malnutrition Screening Tools in Pediatric Oncology Patients A Cross-Sectional StudySebastian MarinNo ratings yet

- Nutritional Assessment and Its Comparison Between Obese and NonDocument37 pagesNutritional Assessment and Its Comparison Between Obese and NonJaspreet SinghNo ratings yet

- Triagem EspenDocument7 pagesTriagem EspenGogo RouNo ratings yet

- J Parenter Enteral Nutr - 2021 - Compher - Guidelines For The Provision of Nutrition Support Therapy in The AdultDocument30 pagesJ Parenter Enteral Nutr - 2021 - Compher - Guidelines For The Provision of Nutrition Support Therapy in The Adultsulemi castañonNo ratings yet

- Jurnal 5Document9 pagesJurnal 5Nuzulia KhoirilliqoNo ratings yet

- Simplified Malnutrition Tool For Thai Patients: Original ArticleDocument6 pagesSimplified Malnutrition Tool For Thai Patients: Original ArticleFitriyana WinarnoNo ratings yet

- Nutrients: Micronutrient Status in 153 Patients With Anorexia NervosaDocument10 pagesNutrients: Micronutrient Status in 153 Patients With Anorexia NervosaReza Yusna HanastaNo ratings yet

- A.S.P.E.N. Clinical Guidelines Nutrition Support of Hospitalized Adult Patients With Obesity.Document9 pagesA.S.P.E.N. Clinical Guidelines Nutrition Support of Hospitalized Adult Patients With Obesity.Madalina TalpauNo ratings yet

- 9994CNR - CNR 7 48Document8 pages9994CNR - CNR 7 48dr.martynchukNo ratings yet

- Cardenas 2021 Nday 2 JPEN Jpen.2085Document10 pagesCardenas 2021 Nday 2 JPEN Jpen.2085CamilaNo ratings yet

- Clinical Impact of Prescribed Doses of Nutrients For Patients Exclusively Receiving Parenteral Nutrition in Japanese HospitalsDocument9 pagesClinical Impact of Prescribed Doses of Nutrients For Patients Exclusively Receiving Parenteral Nutrition in Japanese Hospitalsmarco marcoNo ratings yet

- Systematic Review of Evidence For The Use of Intradialytic Parenteral Nutrition in Malnourished Hemodialysis PatientsDocument7 pagesSystematic Review of Evidence For The Use of Intradialytic Parenteral Nutrition in Malnourished Hemodialysis PatientsCarlos Miguel Mendoza LlamocaNo ratings yet

- EatingDocument14 pagesEatingadrianaNo ratings yet

- J Parenter Enteral Nutr - 2021 - Compher - Guidelines For The Provision of Nutrition Support Therapy in The AdultDocument30 pagesJ Parenter Enteral Nutr - 2021 - Compher - Guidelines For The Provision of Nutrition Support Therapy in The AdultPabloNo ratings yet

- Nutrition Therapy in Critically Ill Patients A Review of Current Evidence For CliniciansDocument7 pagesNutrition Therapy in Critically Ill Patients A Review of Current Evidence For CliniciansangiolikkiaNo ratings yet

- Ed 2020 1Document25 pagesEd 2020 1Alejandra Loyo MonsalveNo ratings yet

- A.S.P.E.N. Clinical Guidelines - Nutrition Screening, Assessment, and Intervention in Adults, ASPEN 2011Document10 pagesA.S.P.E.N. Clinical Guidelines - Nutrition Screening, Assessment, and Intervention in Adults, ASPEN 2011Born to be Wild MyselfNo ratings yet

- Armodafinil in Binge Eating Disorder A RandomizedDocument7 pagesArmodafinil in Binge Eating Disorder A RandomizedQuel PaivaNo ratings yet

- Aplicación Universidad de AarhusDocument21 pagesAplicación Universidad de AarhusFrancisca Cabezas HenríquezNo ratings yet

- Impact of Intensive Nutritional Education With Carbohydrate Counting On Diabetes Control in Type 2 Diabetic PatientsDocument7 pagesImpact of Intensive Nutritional Education With Carbohydrate Counting On Diabetes Control in Type 2 Diabetic PatientsReeds LaurelNo ratings yet

- Rheumatoid Arthritis and Dietary Interventions - Systematic Review of Clinical TrialsDocument19 pagesRheumatoid Arthritis and Dietary Interventions - Systematic Review of Clinical Trialsmededep273No ratings yet

- Enteral Nutrition in Dementia A Systematic ReviewDocument13 pagesEnteral Nutrition in Dementia A Systematic ReviewAkim DanielNo ratings yet

- Validitas SNAQDocument8 pagesValiditas SNAQDanang Adit KuranaNo ratings yet

- Recent Research On BulimiaDocument12 pagesRecent Research On BulimialoloasbNo ratings yet

- The Use of Visceral Proteins As Nutrition Markers: An ASPEN Position PaperDocument7 pagesThe Use of Visceral Proteins As Nutrition Markers: An ASPEN Position PaperAdrián LópezNo ratings yet

- Feeding and Eating Disorders in DSM 5Document3 pagesFeeding and Eating Disorders in DSM 5zoyachaudharycollegeNo ratings yet

- The Impact of Orem's Self-CareDocument9 pagesThe Impact of Orem's Self-CareRiski Official GamersNo ratings yet

- Diet Quality - What Is It and Does It MatterDocument20 pagesDiet Quality - What Is It and Does It MatterDayana Luz Garay RamirezNo ratings yet

- Harmer2019 Article AssociationOfNutritionalStatusDocument9 pagesHarmer2019 Article AssociationOfNutritionalStatusariNo ratings yet

- Intervención Nutricional en Insuficiencia Cardiaca CrónicaDocument10 pagesIntervención Nutricional en Insuficiencia Cardiaca CrónicaFlorenciaNo ratings yet

- Original Paper: World Nutrition JournalDocument6 pagesOriginal Paper: World Nutrition JournalSaptawati BardosonoNo ratings yet

- Systematic Review of Nutritional Interventions For People Admitted To Hospital For Alcohol WithdrawalDocument14 pagesSystematic Review of Nutritional Interventions For People Admitted To Hospital For Alcohol WithdrawalBlanka GelniczkyNo ratings yet

- Clinical CareDocument8 pagesClinical CareDalilaNo ratings yet

- Effects of A Feeding Intervention in Patients With Alzheimer's DiseaseDocument9 pagesEffects of A Feeding Intervention in Patients With Alzheimer's DiseaseDanielly Danino BasilioNo ratings yet

- Nmaa 108Document20 pagesNmaa 108fidya ardinyNo ratings yet

- Guia ESPEN - Tamizaje NutricionalDocument7 pagesGuia ESPEN - Tamizaje NutricionalJudy OlivaNo ratings yet

- Ebp Team Assignment Group 10Document15 pagesEbp Team Assignment Group 10api-621785757No ratings yet

- Paper 4 - Article-7 TRR December 2019 Mrs Kiran DR CP Sharma FullDocument8 pagesPaper 4 - Article-7 TRR December 2019 Mrs Kiran DR CP Sharma FullStavan MehtaNo ratings yet

- Pengantar Gizi Klinik DasarDocument30 pagesPengantar Gizi Klinik DasarMela GuritnoNo ratings yet

- The Association Between A Nutritional Quality Index and Risk of Chronic DiseaseDocument9 pagesThe Association Between A Nutritional Quality Index and Risk of Chronic Diseasekamila rodriguezNo ratings yet

- Asian Nursing ResearchDocument6 pagesAsian Nursing ResearchALmirdhad LatarissaNo ratings yet

- Health-Related Quality of Life For Infants in The Neonatal Intensive Care UnitDocument7 pagesHealth-Related Quality of Life For Infants in The Neonatal Intensive Care Unitsri wahyuniNo ratings yet

- Nutrición y Enfermedad RenalDocument7 pagesNutrición y Enfermedad RenalTeresa La parra AlbaladejoNo ratings yet

- Evaluation of Nutrition Status Using The Subjective Global Assessment: Malnutrition, Cachexia, and SarcopeniaDocument15 pagesEvaluation of Nutrition Status Using The Subjective Global Assessment: Malnutrition, Cachexia, and SarcopeniaLia. OktarinaNo ratings yet

- Allama Iqbal Open University, IslamabadDocument22 pagesAllama Iqbal Open University, Islamabadazeem dilawarNo ratings yet

- Nuevos Tratamientos TCA SeverosDocument10 pagesNuevos Tratamientos TCA SeverosfranciscaikaNo ratings yet

- Hubungan Asupan Nutrisis Dengan Status Gizi Pasien HIV & AIDS (Studi Di UPIPI RSUD Dr. Soetomo Tahun 2010)Document1 pageHubungan Asupan Nutrisis Dengan Status Gizi Pasien HIV & AIDS (Studi Di UPIPI RSUD Dr. Soetomo Tahun 2010)Mirza RisqaNo ratings yet

- Parenteralnutrition: Indications, Access, and ComplicationsDocument21 pagesParenteralnutrition: Indications, Access, and ComplicationsJair Alexander Quintero PanucoNo ratings yet

- 8 InglesDocument19 pages8 IngleskarenhdezcastroNo ratings yet

- Recent Research AnDocument9 pagesRecent Research AnloloasbNo ratings yet

- Artigo 1536Document5 pagesArtigo 1536Solange FernandesNo ratings yet

- Nutritional Status and Dietary Management According To Hemodialysis DurationDocument8 pagesNutritional Status and Dietary Management According To Hemodialysis DurationVione rizkiNo ratings yet

- The Changing Landscape of IBD: Emerging Concepts in Patient ManagementFrom EverandThe Changing Landscape of IBD: Emerging Concepts in Patient ManagementNo ratings yet

- The Prevention and Treatment of Disease with a Plant-Based Diet Volume 2: Evidence-based articles to guide the physicianFrom EverandThe Prevention and Treatment of Disease with a Plant-Based Diet Volume 2: Evidence-based articles to guide the physicianNo ratings yet

- Planet Maths 5th - Sample PagesDocument30 pagesPlanet Maths 5th - Sample PagesEdTech Folens48% (29)

- WWW - Ib.academy: Study GuideDocument122 pagesWWW - Ib.academy: Study GuideHendrikEspinozaLoyola100% (2)

- Excellent Inverters Operation Manual: We Are Your Excellent ChoiceDocument71 pagesExcellent Inverters Operation Manual: We Are Your Excellent ChoicephaPu4cuNo ratings yet

- Ministry of Truth Big Brother Watch 290123Document106 pagesMinistry of Truth Big Brother Watch 290123Valentin ChirilaNo ratings yet

- Sale Deed Document Rajyalakshmi, 2222222Document3 pagesSale Deed Document Rajyalakshmi, 2222222Madhav Reddy100% (2)

- Caltech RefDocument308 pagesCaltech RefSukrit ChatterjeeNo ratings yet

- International Human Rights LawDocument21 pagesInternational Human Rights LawRea Nica GeronaNo ratings yet

- ATLS Note Ed 10Document51 pagesATLS Note Ed 10Nikko Caesario Mauldy Susilo100% (10)

- Chan Sophia ResumeDocument1 pageChan Sophia Resumeapi-568119902No ratings yet

- Nguyễn Thị Ngọc Huyền - 19125516 - Homework 3Document7 pagesNguyễn Thị Ngọc Huyền - 19125516 - Homework 3Nguyễn HuyềnNo ratings yet

- Role of Courts in Granting Bails and Bail Reforms: TH THDocument1 pageRole of Courts in Granting Bails and Bail Reforms: TH THSamarth VikramNo ratings yet

- 06 Cruz v. Dalisay, 152 SCRA 482Document2 pages06 Cruz v. Dalisay, 152 SCRA 482avatarboychrisNo ratings yet

- Man Is Made by His BeliefDocument2 pagesMan Is Made by His BeliefLisa KireechevaNo ratings yet

- INTRODUCTIONDocument1 pageINTRODUCTIONNabila Gaming09No ratings yet

- 76 ECL GuideDocument45 pages76 ECL GuideOana SavulescuNo ratings yet

- Thesis Committee MeetingDocument7 pagesThesis Committee Meetingafknojbcf100% (2)

- A Scenario of Cross-Cultural CommunicationDocument6 pagesA Scenario of Cross-Cultural CommunicationN Karina HakmanNo ratings yet

- Practice Makes Perfect Basic Spanish Premium Third Edition Dorothy Richmond All ChapterDocument67 pagesPractice Makes Perfect Basic Spanish Premium Third Edition Dorothy Richmond All Chaptereric.temple792100% (3)

- Unit 2 Foundations of CurriculumDocument20 pagesUnit 2 Foundations of CurriculumKainat BatoolNo ratings yet

- Forecast Error (Control Chart)Document2 pagesForecast Error (Control Chart)Jane OngNo ratings yet

- Symbiosis National Aptitude Test (SNAP) 2004: InstructionsDocument21 pagesSymbiosis National Aptitude Test (SNAP) 2004: InstructionsHarsh JainNo ratings yet

- Scribe FormDocument2 pagesScribe FormsiddharthgamreNo ratings yet

- Units 6-10 Review TestDocument20 pagesUnits 6-10 Review TestCristian Patricio Torres Rojas86% (14)

- Mathematicaleconomics PDFDocument84 pagesMathematicaleconomics PDFSayyid JifriNo ratings yet

- Mathematics - Grade 9 - First QuarterDocument9 pagesMathematics - Grade 9 - First QuarterSanty Enril Belardo Jr.No ratings yet

- Hard Soft Acid Base TheoryDocument41 pagesHard Soft Acid Base TheorythinhbuNo ratings yet

- English Lesson PlanDocument3 pagesEnglish Lesson PlanJeremias MartirezNo ratings yet

- Habanera Botolena & Carinosa (Gas-A)Document8 pagesHabanera Botolena & Carinosa (Gas-A)christian100% (4)

- Tool Stack Template 2013Document15 pagesTool Stack Template 2013strganeshkumarNo ratings yet

- RFP On Internal AuditDocument33 pagesRFP On Internal AuditCan dien tu Thai Binh DuongNo ratings yet