Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Fund of Funds Diversification

Uploaded by

Flávio FerreiraCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Fund of Funds Diversification

Uploaded by

Flávio FerreiraCopyright:

Available Formats

Fund of Funds

Diversification:

How Much is Enough?

Downloaded from https://jai.pm-research.com by Flavio Ferreira on March 5, 2020 Copyright 1998 Pageant Media Ltd.

JAMES M. PARK AND JEREMY C. STAUM

A

JAMES M. PARK lthough considerable research diversification on portfolio variance. Hill

is a professor of and Schneeweis also showed that as secu-

in the alternative investment

finance at Long Island

area concentrates on the per- rities are added, the tracking error Ž the

University College of

Management and formance characteristics of in- difference of the randomly selected port-

Chairman and CEO of dividual hedge funds or commodity trad- folio’s variance from its expected vari-

PARADIGM Capital ing advisors ŽCTAs. Že.g. Fung and Hsieh ance. decreases.1 As such, investors must

Management in w 1997a, 1997bx. , many investors hold a realize that not only does diversification

New York.

portfolio of alternative investment man- reduce portfolio variance, it also increases

JEREMY C. STAUM agers. For traditional investments, the rule accuracy in achieving the expected level

is a Ph.D. candidate at of thumb that nearly all of the diversifi- of risk.2

Columbia Business able risk is eliminated in a portfolio of ten

School and Director of stocks dates back to Evans and Archer

Research PARADIGM

w 1968x . Evans and Archer discussed the RANDOM DIVERSIFICATION

Capital Management FOR MANAGED FUNDS

in New York. mathematical relationship between the size

and variance of a portfolio and showed

that for an equally weighted portfolio each Results for portfolios of managed

randomly selected security added to the futures and hedge funds are similar to

portfolio produces an ever smaller de- those illustrated in previous studies on

crease in portfolio variance. The actual stock and bond diversification. Billingsley

impact of random security diversification and Chance w 1996x have shown that naive

for stock and bond portfolios has been diversification among as few as ten CTA

analyzed by various authors. Both Elton managers results in a mixed stock

and Gruber w 1977x and Hill and Schneeweis Žstock兾bond. and CTA portfolio resulting,

w 1980x illustrated the impact of random on average, in a lower asymptotic portfo-

security selection on portfolio variance for lio variance. The benefit of adding CTAs

stocks and bonds, respectively. In both to the traditional passive stock and bond

cases, the final impact is determined by portfolio comes from the low correlation

the intrasample correlations. For instance, between the CTAs and the traditional in-

Hill and Schneeweis show that for portfo- vestment vehicles.

lios of AAA bonds, the high intracorrela- The number of CTAs required to

tion of AAA rated bonds, in contrast to achieve the lower variance bound for the

BAA rated bonds, lessens the impact of mixed traditional and nontraditional port-

WINTER 1998 THE JOURNAL OF ALTERNATIVE INVESTMENTS 39

folio is, as for stocks or bonds, determined by the where 12 is the expected variance of a single

correlation among the represented sample CTAs. randomly selected security, M2 is the variance of

The more similar the styles and markets traded, the the market portfolio of securities, and n2 is the

lower the impact of the increased number of CTAs expected variance of a randomly selected portfolio

on reducing the portfolio variance. For stand-alone of n securities.5

alternative investment portfolios, Henker and Martin Equation Ž1. shows how the expected variance

w 1998x showed that the higher the intracorrelation of a portfolio of n randomly selected securities de-

Downloaded from https://jai.pm-research.com by Flavio Ferreira on March 5, 2020 Copyright 1998 Pageant Media Ltd.

among CTAs in a universe, the lower the number of pends on only two empirically estimated quantities,

CTAs required to achieve the lower variance bound 1 and M . In all cases, a portfolio of size 5

as well as to mimic the underlying universe’s perfor- eliminates 80% Ž1 y 1兾5. of the diversifiable vari-

mance benchmark.3 Last, research has shown the ance, whereas a portfolio of size 20 eliminates 95%

potential benefits of CTA investment in enlarging Ž1 y 1兾20. of the diversifiable variance. However, 1

the efficient frontier when considered as part of a and M must be estimated for each class of securi-

mixed stock and bond portfolio Ž Edwards and Park ties. The greater the ratio of the diversifiable risk

w 1996x. . Ž 12 y M2 . to nondiversifiable risk M2 , the greater

Although original research on the benefits of the benefits of diversification.

naive diversification concentrated on the absolute

reduction in portfolio risk and the ability of the

portfolio to track that of the underlying universe of ILLUSTRATION OF

benchmark, more recent research Ž Statman w 1987x. DIVERSIFICATION BENEFITS

concluded that investors should perform a marginal

cost兾benefit analysis in terms of a common

A comparison of several asset classes illus-

return兾risk ratio to determine an appropriate num-

trates the benefits of diversification across CTAs and

ber of securities to hold. In practice, there is no

hedge funds relative to typical stock diversification.

widely used method for computing this number, but

The data for 948 CTAs and 1230 hedge funds comes

Statman showed that many investors’ diversification

from the TASS data base for the years 1989 through

policies, which often result in portfolios of fewer

1996, and incorporates a correction for survivorship

than ten assets, appear to be suboptimal in terms of

bias discussed in Park w 1995x . The data for NYSE

the tradeoff between reducing variance and the ac-

stocks comes from Elton and Gruber w 1995x . Exhibits

tual return兾risk performance.

1 and 2 show that increasing the size of the portfolio

from five to twenty decreases the expected portfolio

FUND OF FUNDS DIVERSIFICATION

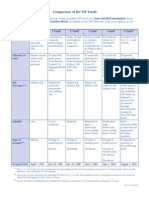

In particular, one may address the question of EXHIBIT 1

how many funds belong in a fund of funds. In

Volatility Versus Portfolio Size

practice, has the fund of funds industry attained an

acceptable level of diversification? TASS Manage-

ment, a London-based information services firm

monitoring CTAs and hedge funds, provides an in-

dustry average. Funds of funds contain a mean of

fewer than five funds, and a median of four.4 How

good is the amount of diversification provided by

five funds? Given a simple assumption that all securi-

ties have the same correlation with each other, sta-

tistical theory yields a simple relationship between

portfolio size and variance:

n2 s M2 q Ž 12 y M2 . 兾n Ž 1.

40 FUND OF FUNDS DIVERSIFICATION: HOW MUCH IS ENOUGH? WINTER 1998

EXHIBIT 2

Reduction in Risk through Diversification

Asset Nondiversifiable Diversifiable Reduction

Class Std. Deviation Std. Deviation 1 5 20 in Risk (%)

CTAs 3.57 3.34 6.91 4.44 3.81 14.33

Hedge Funds 2.05 2.42 4.47 2.71 2.24 17.59

Downloaded from https://jai.pm-research.com by Flavio Ferreira on March 5, 2020 Copyright 1998 Pageant Media Ltd.

NYSE Stocks 2.66 4.17 6.83 3.87 3.01 22.31

Data for stocks are presented for purposes of comparison.

standard deviation by differing proportions for CTAs, annum, over his actual strategy. Exhibit 3 summa-

hedge funds, and NYSE stocks. The greatest im- rizes the results for CTAs, hedge funds, and stocks.

provement is for stocks; the least is for CTAs. All

show a substantial reduction in risk Ž 1 y 20兾5 .. CONCLUSION

Statman w 1987x suggested a method for assign-

ing a value to this reduction in risk. Suppose that an In the case of stock investors who lend or

average fund of funds manager has investments in borrow, Statman presented this method with the

five randomly selected CTAs and feels that he has profits from leverage reduced by the risk-free or

achieved an acceptable level of risk at 4.44% monthly call-money rates, respectively. This reduces the

standard deviation. As an average fund of CTAs leveraged stock return from what would have been

manager, he has accumulated historical returns over 22.61% without interest costs. Although leveraging

1989 through 1996 of 12.81%. How much better hedge funds requires borrowing, free leverage is

could he have done by investing in twenty randomly generally available for CTAs up to 4 or 5:1. ŽThe

selected CTAs while leveraging his investment up to only part of a CTAs’ return that may not be lever-

4.44% standard deviation? Increasing standard devia- aged is interest income on margin account balances,

tion from 3.81% to 4.44% allows the manager a which is typically only a small part of the overall

leverage factor of 1.17 Ž 4.44兾3.81. . This results in return.. This means that, for instance, it is possible

annual returns of 15.09%, or a gain of 2.28% per without borrowing to leverage 2:1 a fund whose

EXHIBIT 3

Gains from Diversifying and Leveraging

Asset Annual Interest Leveraged Gain in

Class Return Leverage Rate (%) Return Return

CTAs 12.81 1.17 0 15.09 2.28

Hedge Funds 12.83 1.21 0 15.76 2.93

Stocks ŽLend. 17.20 1.29 5 20.70 3.50

Stocks ŽBorrow. 17.20 1.29 7 20.12 2.93

In a lending portfolio Ži.e., which includes cash., leverage requires a reduction in lending and

foregone interest at the risk-free rate, 5%. In a borrowing portfolio, leverage requires further

borrowing at the call-money rate, 7%. Figures have been rounded.

WINTER 1998 THE JOURNAL OF ALTERNATIVE INVESTMENTS 41

5

notional allocations are one-third to hedge funds and For a full discussion of the impact of random

two-thirds to CTAs, by leveraging the CTAs 4:1. security selection on portfolio variance, see Elton and

In the absence of borrowing costs for lever- Gruber w 1977x .

age, the only barrier to diversification is the ability

to make the minimum investment in each fund.

REFERENCES

Management expense for a fund of five funds should

be roughly the same as for a fund of twenty funds.

Downloaded from https://jai.pm-research.com by Flavio Ferreira on March 5, 2020 Copyright 1998 Pageant Media Ltd.

Moreover, the argument that ‘‘overdiversification’’ Billingsley, T., and D. Chance. ‘‘Benefits and Limitations

can lead to ‘‘diversifying returns away’’ is erroneous. of Diversification among Commodity Trading Advisors.’’

If adding another money manager to a fund really Journal of Portfolio Management, Fall Ž1996., pp. 65᎐80.

dilutes its returns, this fund’s managers must have

greater expected return than all other managers. Edwards, F., and J. Park. ‘‘Do Managed Futures Make

Obviously, this cannot be simultaneously true for Good Investments?’’ Journal of Futures Markets, 16 Ž1996.,

pp. 475᎐517.

every fund’s selections. The theory of naive diversifi-

cation is based on the assumption that the typical

Elton, E.J., and M.J. Gruber. ‘‘Risk Reduction and Portfo-

portfolio manager is naive in the sense of not know-

lio Size: An Analytical Solution.’’ Journal of Business, 50

ing which money managers are the best, and must Ž1977., pp. 415᎐437.

pick randomly. There is almost no cost to increasing

the size of a fund of funds from five Ž the industry ᎏᎏ. Modern Portfolio Theory and Investment Analysis, 5th

average. to twenty. Because the penalty for inade- edition. New York: Wiley, 1995, p. 61.

quate diversification is, in effect, foregone profits, it

seems that funds of funds may wish to embrace Evans, J.L., and S.H. Archer. ‘‘Diversification and the

diversification more fully. Reduction of Dispersion: An Empirical Analysis.’’ Journal

of Finance, 23 Ž1968., pp. 761᎐767.

ENDNOTES

Fung, W., and D. Hsieh. ‘‘Empirical Characteristics of

1

See Statman w 1987x for a similar analysis of ran- Dynamic Trading Strategies: The Case of Hedge Funds.’’

dom equity selection. Review of Financial Studies, Summer Ž1997., pp. 275᎐302.

2

Note that the impact of naive security selection

on portfolio performance concentrates on risk. The ᎏᎏ. ‘‘Survivorship Bias and Investment Style in the

central limit theorem of statistics shows that sample Returns of CTAs.’’ Journal of Portfolio Management, Fall

size affects the sample mean’s variance, but not its Ž1997., pp. 30᎐41.

expectation.

3

It is important to point out that an assumption

Henker, T., and G. Martin. ‘‘Naive Diversification for

underlying naive Žrandom. asset selection is that asset

Managed Futures.’’ Working paper, CISDM兾SOM, Uni-

weights are equal, not optimized after selection. For

versity of Massachusetts, 1998.

planned asset diversification based on traditional

mean兾variance optimization, research has shown the po-

tential benefits of CTA investment in enlarging the effi- Hill, J., and T. Schneeweis. ‘‘Diversification and Portfolio

cient frontier when considered as part of a mixed stock Size for Fixed Income Securities.’’ Journal of Economics and

and bond portfolio. See Schneeweis w 1998x . Business, Winter Ž1980., pp. 115᎐121.

4

The TASS data base is not a random sample of

the universe of funds. Moreover, the low 24% response Park, J.M. Managed Futures as an Investment Class Asset. Ann

rate to this question raises some doubts as to the accuracy Arbor: UMI Dissertation Services, 1995.

of this number. Nonetheless, in the absence of obvious

biases leading to underresponse by funds with large num- Statman, M. ‘‘How Many Stocks Make a Diversified

bers of submanagers, it seems safe to claim that the Portfolio?’’ Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, 22

average is not much more than five funds. Ž1987., pp. 353᎐363.

42 FUND OF FUNDS DIVERSIFICATION: HOW MUCH IS ENOUGH? WINTER 1998

You might also like

- Does Gender Matter?: Younger Generations' Investing Behaviors in Mutual FundsDocument11 pagesDoes Gender Matter?: Younger Generations' Investing Behaviors in Mutual FundsSanjita ParabNo ratings yet

- The Analysis of Mutual Fund Performance: Evidence From U.S. Equity Mutual FundsDocument156 pagesThe Analysis of Mutual Fund Performance: Evidence From U.S. Equity Mutual FundsNeeraj Singh RainaNo ratings yet

- The Surprising Alpha From Malkiel's Monkey and Upside-Down StrategiesDocument15 pagesThe Surprising Alpha From Malkiel's Monkey and Upside-Down StrategiesAndresNo ratings yet

- Andonov Et Al A Global Perspective On Pension Investments in Real EstateDocument11 pagesAndonov Et Al A Global Perspective On Pension Investments in Real EstateJuan Manuel FigueroaNo ratings yet

- Best fund managers 2019Document26 pagesBest fund managers 2019Manohar BNo ratings yet

- Ampersand White Paper - Risk Contribution of StocksDocument16 pagesAmpersand White Paper - Risk Contribution of StockstabbforumNo ratings yet

- Can Portfolios Be Crisis Proofed?: The Best of Strategies For The Worst of TimesDocument22 pagesCan Portfolios Be Crisis Proofed?: The Best of Strategies For The Worst of Timesavallonia9No ratings yet

- Risk Parity Portfolio vs. Other Asset Allocation Heuristic PortfoliosDocument11 pagesRisk Parity Portfolio vs. Other Asset Allocation Heuristic Portfolioscuitao42No ratings yet

- Black 2013Document10 pagesBlack 2013jacekinneNo ratings yet

- Fabozzi Gupta MarDocument16 pagesFabozzi Gupta MarNurwahidah AbidinNo ratings yet

- Portfolio Theory Creates New Investment OpportunitiesDocument3 pagesPortfolio Theory Creates New Investment OpportunitiesCardoso PenhaNo ratings yet

- West 2017Document15 pagesWest 2017gogayin869No ratings yet

- Fintech AssignmentDocument2 pagesFintech AssignmentAlka RajpalNo ratings yet

- DFI J-F-2019 DigitalDocument111 pagesDFI J-F-2019 DigitalAlinNo ratings yet

- Raising Venture Capital For The Serious Entreprene... - (Part I Understanding The Basics of The Venture Capital Method)Document28 pagesRaising Venture Capital For The Serious Entreprene... - (Part I Understanding The Basics of The Venture Capital Method)jasmesNo ratings yet

- Sources of Return in Global Investing - JPM - Win05Document10 pagesSources of Return in Global Investing - JPM - Win05medavis54251No ratings yet

- A Spectrum Approach To Active Risk Budgeting: Rethinking The BarbellDocument12 pagesA Spectrum Approach To Active Risk Budgeting: Rethinking The Barbellwangshuqing97No ratings yet

- Morningstar's Classification of Large-Cap Mutual Funds (2001)Document11 pagesMorningstar's Classification of Large-Cap Mutual Funds (2001)Gonza NNo ratings yet

- Personal Investment Literacy Among College Students: A SurveyDocument10 pagesPersonal Investment Literacy Among College Students: A SurveyHer MioneNo ratings yet

- Ane Empiric Cal Inve Int Estigati The Indi Ionoft Ian Sto The Prof Ock Mar Fitabilit Rket Ty Anom MalyDocument15 pagesAne Empiric Cal Inve Int Estigati The Indi Ionoft Ian Sto The Prof Ock Mar Fitabilit Rket Ty Anom MalyAravindVenkatramanNo ratings yet

- AR Personal FinanceDocument7 pagesAR Personal FinanceGil M. Acid Jr.No ratings yet

- Fund ComparisonsDocument1 pageFund Comparisonsarom09No ratings yet

- SPE68603Document7 pagesSPE68603Jose Gregorio Fariñas GagoNo ratings yet

- Complete IssueDocument184 pagesComplete IssueMichael PetersNo ratings yet

- Angel NetworksDocument12 pagesAngel NetworksShashank SinghNo ratings yet

- Personal Investment Literacy Among College StudentDocument11 pagesPersonal Investment Literacy Among College StudentMinh Châu VũNo ratings yet

- A Study On Investor's Perception Towards Mutual Fund in The City of BhubaneswarDocument8 pagesA Study On Investor's Perception Towards Mutual Fund in The City of BhubaneswarAkhileshNo ratings yet

- Asset Allocation in The Chinese Stock Market The Role of Return PredictabilityDocument13 pagesAsset Allocation in The Chinese Stock Market The Role of Return PredictabilityNabila AriantiNo ratings yet

- Risk-Return Analysis of ICICI Mutual FundsDocument67 pagesRisk-Return Analysis of ICICI Mutual FundsMaha Lakshmi0% (1)

- Hitch Hikers Guide To Funding ReadinessDocument28 pagesHitch Hikers Guide To Funding ReadinessJulian YellowSan NelNo ratings yet

- J 100 JPMorganDocument40 pagesJ 100 JPMorganKartik DhinakaranNo ratings yet

- JAI-Hedge-Fund-Industry-Overview1Document11 pagesJAI-Hedge-Fund-Industry-Overview1JayaNo ratings yet

- Hedge Fund ValuationDocument4 pagesHedge Fund ValuationFarnaz ChavoushiNo ratings yet

- The Business Cycle and Expectations-Driven Investment CyclesDocument109 pagesThe Business Cycle and Expectations-Driven Investment CyclesAntonio NikolovNo ratings yet

- Barron's - 05.04.2021Document117 pagesBarron's - 05.04.2021marcelo moNo ratings yet

- Signal Weighting by Richard GrinoldDocument11 pagesSignal Weighting by Richard GrinoldJolin Majmin100% (1)

- Corporate Presentation 4-7-2020Document24 pagesCorporate Presentation 4-7-2020Azrunnas ZakariaNo ratings yet

- Fuzzy Cross-Entropy, Mean, Variance, Skewness Models For Portfolio SelectionDocument9 pagesFuzzy Cross-Entropy, Mean, Variance, Skewness Models For Portfolio SelectionSasha GelfandNo ratings yet

- Wallstreetjournal 20191107 TheWallStreetJournalDocument32 pagesWallstreetjournal 20191107 TheWallStreetJournalMustafa LOUGHNIMINo ratings yet

- PhiladelphiaBusinessJournal Sept. 22, 2017Document36 pagesPhiladelphiaBusinessJournal Sept. 22, 2017Craig EyNo ratings yet

- Venture Capital: A Geographical PerspectiveDocument43 pagesVenture Capital: A Geographical PerspectivePaul DavisNo ratings yet

- Euromoney Institutional Investor PLC The Journal of Private EquityDocument15 pagesEuromoney Institutional Investor PLC The Journal of Private EquitynishthaNo ratings yet

- Fund Performance: Active Risk Budgeting in Action: Understanding HedgeDocument12 pagesFund Performance: Active Risk Budgeting in Action: Understanding Hedgewangshuqing97No ratings yet

- Research Paper (Somya Kakra and Tanya Garg)Document19 pagesResearch Paper (Somya Kakra and Tanya Garg)somyaNo ratings yet

- SSRN Id1873234Document70 pagesSSRN Id1873234Ayer MañanaNo ratings yet

- February 10 To 21 2020 PDFDocument7 pagesFebruary 10 To 21 2020 PDFFrenie MoliNo ratings yet

- Arkan, AppendixDocument4 pagesArkan, AppendixMd ArkanNo ratings yet

- Fund Factors 2009janDocument43 pagesFund Factors 2009janj.fred a. voortman100% (3)

- Does Portfolio Concentration Affect Corporate Bond Fund PerformanceDocument19 pagesDoes Portfolio Concentration Affect Corporate Bond Fund PerformanceLauraNo ratings yet

- ALL Change: Nvestor ErvicesDocument100 pagesALL Change: Nvestor Ervices2imediaNo ratings yet

- Fund Source PDFDocument1 pageFund Source PDFMaeTeñosoDimaculanganNo ratings yet

- Fund Source PDFDocument1 pageFund Source PDFMaeTeñosoDimaculanganNo ratings yet

- How Can Mutual Funds Help Me? What Are Mutual Funds? What Are THE Types of Funds? Benefits ofDocument1 pageHow Can Mutual Funds Help Me? What Are Mutual Funds? What Are THE Types of Funds? Benefits ofCarmel Buniel SabadoNo ratings yet

- The Money Markets: Key Words: Public Debt, T-Bills, Repos, Book Entry, Commercial Papers, CertificateDocument23 pagesThe Money Markets: Key Words: Public Debt, T-Bills, Repos, Book Entry, Commercial Papers, CertificateTatiana BuruianaNo ratings yet

- Real Estate Value Fund: AS OF JUNE 30, 2021Document7 pagesReal Estate Value Fund: AS OF JUNE 30, 2021Owm Close CorporationNo ratings yet

- June 2018 23Document7 pagesJune 2018 23jayswalhiralal899No ratings yet

- ISJ008Document84 pagesISJ0082imediaNo ratings yet

- Engineering Economics Assignment 2Document6 pagesEngineering Economics Assignment 2balkrishna7621No ratings yet

- Order in The Matter of M/s Bishal Abasan India Limited (BAIL)Document37 pagesOrder in The Matter of M/s Bishal Abasan India Limited (BAIL)Shyam SunderNo ratings yet

- Lunar Rubbers PVT LTDDocument76 pagesLunar Rubbers PVT LTDSabeer Hamsa67% (3)

- 6898 - Equity InvestmentsDocument2 pages6898 - Equity InvestmentsAljur SalamedaNo ratings yet

- Chapter 5 Quantitative ProblemsDocument2 pagesChapter 5 Quantitative ProblemsVăn Ngọc PhượngNo ratings yet

- Activity Chapter 1 Actg 111aDocument2 pagesActivity Chapter 1 Actg 111aVergs Valencia100% (3)

- FabHotels Invoice 15UR2XDocument1 pageFabHotels Invoice 15UR2XDev singh100% (1)

- ACCT5001 2022 S2 - Module 2 - Lecture Slides StudentDocument33 pagesACCT5001 2022 S2 - Module 2 - Lecture Slides Studentwuzhen102110No ratings yet

- LKP Spade - Tatachem - 30decDocument3 pagesLKP Spade - Tatachem - 30decBhavya jainNo ratings yet

- Triple Trouble2 (Mar09)Document10 pagesTriple Trouble2 (Mar09)Jolin MajminNo ratings yet

- Description of Research InterestsDocument6 pagesDescription of Research InterestsManas DimriNo ratings yet

- Chapter 5 - Health Insurance SchemesDocument0 pagesChapter 5 - Health Insurance SchemesJonathon CabreraNo ratings yet

- DR Pepper Snapple Keurig Green Mountain Slide Deck - FINALDocument30 pagesDR Pepper Snapple Keurig Green Mountain Slide Deck - FINALlisaNo ratings yet

- 10 1108 - Ijlma 03 2017 0060 PDFDocument21 pages10 1108 - Ijlma 03 2017 0060 PDFNur aziziNo ratings yet

- Unit-1 Potential RevenueDocument5 pagesUnit-1 Potential RevenueYash RajNo ratings yet

- Case Study: Equitas MicroDocument4 pagesCase Study: Equitas MicropvassiliadisNo ratings yet

- Tax Invoice/Bill of Supply/Cash Memo: (Original For Recipient)Document1 pageTax Invoice/Bill of Supply/Cash Memo: (Original For Recipient)Sanchita KunwerNo ratings yet

- Institute of Business Management: Lms Based Finalexaminations-Summer 2020 Analytical PartDocument3 pagesInstitute of Business Management: Lms Based Finalexaminations-Summer 2020 Analytical PartSafi SheikhNo ratings yet

- Mit Commercial Real Estate Analysis and Investment Online Short Program BrochureDocument9 pagesMit Commercial Real Estate Analysis and Investment Online Short Program BrochureTino MatsvayiNo ratings yet

- ACTREV 4: Business Combination Review QuestionsDocument6 pagesACTREV 4: Business Combination Review QuestionsProm GloryNo ratings yet

- P2 ACR Business Combinations ArticleDocument6 pagesP2 ACR Business Combinations Articlerain06021992No ratings yet

- Estmt - 2023 02 17Document6 pagesEstmt - 2023 02 17allan tu50% (2)

- IESBA Code of Ethics For AADocument10 pagesIESBA Code of Ethics For AAMuhammad YousafNo ratings yet

- Ark Autonomous Technology & Robotics Etf Arkq Holdings PDFDocument1 pageArk Autonomous Technology & Robotics Etf Arkq Holdings PDFandrew2020rNo ratings yet

- PN DeedDocument8 pagesPN DeedSunita SinghNo ratings yet

- Vista Equity Partners - 2017 Analyst PositionDocument4 pagesVista Equity Partners - 2017 Analyst PositionJonathan StewartNo ratings yet

- CH 03Document47 pagesCH 03api-3804982No ratings yet

- Commerce Questions For PSC ExamsDocument40 pagesCommerce Questions For PSC ExamsShanmuga SubramanianNo ratings yet

- MBA IV Sem Important Questions of Behaviural Finance MBA 4th SemDocument3 pagesMBA IV Sem Important Questions of Behaviural Finance MBA 4th SemrohanNo ratings yet

- EarlyRetirementNow Side Hustle SWR ToolboxDocument375 pagesEarlyRetirementNow Side Hustle SWR ToolboxJaredNo ratings yet