0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

620 views152 pagesMarine Engineering

Uploaded by

donatoCopyright

© © All Rights Reserved

We take content rights seriously. If you suspect this is your content, claim it here.

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online on Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

620 views152 pagesMarine Engineering

Uploaded by

donatoCopyright

© © All Rights Reserved

We take content rights seriously. If you suspect this is your content, claim it here.

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online on Scribd

oN en) ~ ae

CLASS 1 DECK

raat |

AL

¥

eo

Ue :

i 5

ase

ai

7

8

sg

c

Od

Bae

BS

AN

MARINE 4

ENGINEERING ~

% ;"

me em

ats

a T

iy - pANGIrora 1sLANO

Se me be ee pe

THE NEW ZEALAND MARITIME SCHOOL

MANUKAU INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY

MASTERS / MATES FOREIGN GOING

ENGINEERING _7th-18" February 2005 Tutor Roy Swan

TIME:

10 DAYS INCLUDING TUITION AND ASSESSMENTS

PROGRAMME:

THE ATTACHED TIMETABLE SHOWS THE TOPICS TO BE COVERED

DURING THE COURSE.

OBJECTIVE:

BY THE END OF THE COURSE STUDENTS WILL UNDERSTAND THE

BASIC PRINCIPLES OF MAIN AND AUXILIARY MACHINERY USED ON

BOARD VARIOUS TYPES OF SHIP AND BE AWARE OF THEIR FUNCTIONS

AND LIMITATIONS FROM A MASTER OR DECK OFFICERS VIEWPOINT.

ASSESSMENT:

A3HOUR WRITTEN ASSESSMENT WILL BE HELD ON THE FRIDAY OF

THE SECOND WEEK. A MARK OF 60% IS REQUIRED TO PASS.

PRACTICE AND A PRACTICAL ASSESSMENT ON THE ENGINE

SIMULATORS WILL BE UNDERTAKEN THROUGHOUT THE COURSE.

‘THESE WILL BE ASSESSED AS COMPETENT OR NOT YET COMPETENT.

DETAILS ON SEPARATE SHEET.

TEACHING METHODS:

STCW95 HAS RAISED THE ACADEMIC REQUIREMENTS FOR TRAINING

OF SHIPS OFFICERS AND REQUIRES PROOF OF COMPETENCY BEFORE

ISSUE OF CERTIFICATES.

IN LINE WITH THIS THE MARITIME SCHOOL HAS A POLICY OF

ENCOURAGING AN INCREASINGLY HIGH STANDARD OF STUDY AND.

ASSESSMENT TO ENSURE THAT NEW ZEALAND CERTIFICATE HOLDERS

CONTINUE TO BE REGARDED AS AMONG THE BEST TRAINED IN THE

WORLD.

THIS REQUIRES A POSITIVE ATTITUDE BOTH FROM STAFF AND

STUDENTS AND A HIGHER DEGREE OF SELF CENTRED STUDY AND.

RESEARCH THAN PREVIOUSLY.

ALTHOUGH FORMAL CLASSES FINISH AT 2PM IT IS EXPECTED THAT

STUDENTS WILL USE THE AVAILABLE TIME TO SUPPLEMENT CLASS

NOTES AND LECTURES WITH PRIVATE STUDY, RESEARCH AND

REVISION USING LIBRARY TEXTS, INTERNET, TRADE MAGAZINES,

ENGINE SIMULATOR AND ANY OTHER RELEVANT MATERIAL.

SHOULD YOU HAVE ANY PROBLEMS WITH THE WORK PLEASE

CONTACT YOUR TUTOR OR THE DIRECTOR AS SOON AS POSSIBLE.

IF YOU REQUIRE ASSISTANCE OR ADVICE AT ANY TIME PLEASE ASK,

WE ARE HERE TO HELP YOU !

GOOD LUCK !

COURSE: MASTER'S ENGINEERING

1

1

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

24

22

23

24

25

26

Diesel Propulsion Machinery

Describes the layout of diesel propulsion systems.

Describes gearing and reversing mechanism used in conjunction with medium speed

diesel engines and fixed and controlled pitch propellers.

Describes the causes of scavenge fires and the precaution to take to prevent them.

Describes the causes of crankcase explosions.

States the precautions to be taken when an oil mist is detected.

Explains the controls for slow speed and medium speed diesel engines.

Describes the interlocks associated with the controls of a slow and medium speed

diesel engine.

Describes the process of preparing marine diesel engines for departure.

Explains operating procedures prior to movement and during long idle time during

standby.

Describes the starting procedure for a slow speed diesel engine,

Describe operating procedures at full away, arrival, standby, finished with engines.

Describes the procedure for emergency full aster.

Describe the process of starting and putting on load for a diesel generator, alternator,

pump and air compressor.

Describes the transmission of power from a diesel engine to the propeller and thence

the ship.

Describes use of gearing in medium speed diesel engines.

Discusses "Maximum Efficiency" conditions, especially for C.P. propellers, and the

various load controls in the engine control room.

Describes the main power losses associated with diesel engines between fuel energy

content and shatt power obtained.

Discusses methods of minimising the losses referred to in 1.17.

Bollers

Describe exhaust boilers, composite bollers, water tube boilers (one main, one

auxiliary).

Describe the function of safety valves, drains, vents, gauge glasses.

Explain the function of water level alarms and associated alarms.

Describes the function of the fuel supply system to a boller and the associated safety

devices, alarms and interlocks.

Describes the process of flashing up and shutting down water tube boilers and

associated operating procedures.

‘Appreciates the problems associated with salt or oil contamination in boilers.

a4

32

4d

42

43

44

5A

52

53

61

62

63

64

2

7A

72

73

74

75

at

82

Evaporators/Desalination Plant

Describes flash evaporators and a reverse osmosis plant.

Explains procedures to ensure the production of safe drinking water.

Turbines.

Describes the layout of steam turbine plant.

Describes manoeuvring procedure for a steam turbine in conjunction with fixed and

Controlled pitch propellers.

Describes the alarms and safety devices associated with steam turbine propulsion.

Describes the transmission of power from a steam turbine to the propeller, and thence

to the ship.

Pumps

Describes the operating principle of the following types of pump in marine application;

reciprocating, gear, screw, axial flow, centrifugal, eductor, variable displacement pump

[Hele Shaw).

‘Selects suitable pumps for use in given shipboard application.

Describes the operation of given shipboard pumping systems for use in cargo

‘operations, bilge and ballast systems, engine rooms.

Steering

Describes the operation of electro-hydraulic steering gear.

Describes the hydraulic and electric system linking the steering position to steering

(gear, and hunting gear relating to each (one of each type)..

Describes routine operating procedures and safety checks.

Describes duplicate and emergency steering systems and methods of changing from

ain to emergency steering systems.

Refrigeration Plant

Describes the vapour compression refrigeration cycle.

Describes the components of a vapour compression refrigeration system.

Describes refrigeration systems for the carriage of refrigerated cargo in a general

cargo vessel.

Describes refrigeration systems for the carriage of cargo in container vessels.

Properties of refrigerants. Dangers associated with freon, ammonia and

trichlorethylene.

‘Sewage Treatment Systems

Describes the operation of a biological sewage treatment system.

Describes the operation of a chemical sewage treatment system, and incineration of

sewage.

83

a4

92

93

94

95

96

10.

10.1

12.

124

122

13.

13.4

132

133

13.4

14.

Explains the requirements for the control of pollution from ships sewage systems.

Control Systems

Basic concepts of a control system.

Defines the terms open loop and closed loop.

Identifies the components of open loop and closed loop systems.

Defines a cascade control system.

Defines discontinuous control, continuous control, proportional control, integral control,

derivative control,

Identifies the function of each control action.

Transducers

‘Applies the concept of the transducer to the operation of:

(a) liquid level sensors

(b) flow rate measurement

(6) _ speed and revolution counters

(@) temperature sensors (highviow)

(e) relative humidity measurement

(gas detectors and monitors

(9) ollin water monitors

(h) tank contents and draught gauges

Controllers and Actuators

Describes a pneumatic controller and actuator.

Describes a hydraulic controller and actuator.

Describes an electric controller and actuator.

Regulators

Describes the operation of gate, butterfly, plug and needle valves as regulators.

Describes the function of a pneumatic positioner.

Main engine contro! system

With the aid of block diagrams describes the principles of bridge control, including fail

safe, fail run and safety interiocks for:

(2) _ steam turbines with associated boilers

(0) slow speed 2 stroke diesel engines

(6) medium speed diesel engines fitted with controlled pitch propeller or reversing

‘gear box.

Describes the procedure for changing from bridge control to engine room control and

vice versa.

Lists the requirements for plant monitoring and alarm systems for UMS operation.

Describes the operating procedures when a manual check is being made in engine

room during unmanned operations, under alarm conditions,

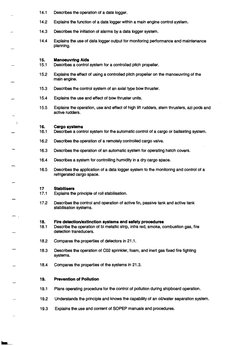

Data Loggers

14.1

142

14.3

144

15.

15.4

152

15.3

15.4

155

16.

16.1

16.2

16.3

16.4

165

7

174

172

18.

18.4

182

18.3

18.4

19.

19.4

192

19.3

Describes the operation of a data logger.

Explains the function of a data logger within a main engine control system.

Describes the initiation of alarms by a data logger system.

Explains the use of data logger output for monitoring performance and maintenance

planning,

Manoeuvring Aids

Describes a control system for a controlled pitch propeller.

Explains the effect of using a controlled pitch propeller on the manoeuvring of the

main engine.

Describes the control system of an axial type bow thruster.

Explains the use and effect of bow thruster units.

Explains the operation, use and effect of high lft rudders, stem thrusters, azi pods and

active rudders.

Cargo systems

Describes a control system for the automatic control of a cargo or ballasting system.

Describes the operation of a remotely controlled cargo valve.

Describes the operation of an automatic system for operating hatch covers.

Describes a system for controling humidity in a dry cargo space.

Describes the application of a data logger system to the monitoring and control of a

refrigerated cargo space.

Stabllisers

Explains the principle of roll stabilisation.

Describes the control and operation of active fin, passive tank and active tank

stabilisation systems.

Fire detection/extinction systems and safety procedures

Describe the operation of bi metalic strip, infra red, smoke, combustion gas, fre

detection transducers.

‘Compares the properties of detectors in 21.1.

Describes the operation of C02 sprinkler, foam, and inert gas fixed fire fighting

systems.

Compares the properties of the systems in 21.3.

Prevention of Pollution

Plans operating procedure for the control of pollution during shipboard operation.

Understands the principle and knows the capability of an ollwater separation system.

Explains the use and content of SOPEP manuals and procedures.

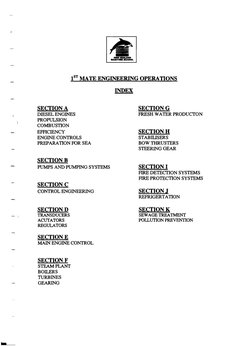

18" MATE ENGINEERING OPERATII

SE! INA

DIESEL ENGINES

PROPULSION

COMBUSTION

EFFICIENCY

ENGINE CONTROLS

PREPARATION FOR SEA

SECTION B

PUMPS AND PUMPING SYSTEMS

SECTION

CONTROL ENGINEERING

SECTION D

TRANSDUCERS:

ACUTATORS

REGULATORS

SECTION E

MAIN ENGINE CONTROL

SECTION F

STEAM PLANT

BOILERS

TURBINES

GEARING

INDEX

SECTION G

FRESH WATER PRODUCTON

SECTION H

STABILISERS

BOW THRUSTERS

STEERING GEAR

SECTIONI

FIRE DETECTION SYSTEMS

FIRE PROTECTION SYSTEMS.

SECTION

REFRIGERTATION

SECTION K

SEWAGE TREATMENT

POLLUTION PREVENTION

fe

18 MATE ENGINEERING OPERATIONS

SECTION A

DIESEL ENGINES

PROPULSION

COMBUSTION

EFFICIENCY

ENGINE CONTROLS

PREPARATION FOR SEA

CRANKCASE EXPLOSIONS

SCAVENGE FIRES

15" Mates / Master

Marine Engineering 1.

General

Main Propulsio

‘Many types of propulsion systems exist for ships but excluding nuclear

fuel the source of power is invariably fuel oil.

This is converted into energy to drive the ship by two main processes,

(2) by burning fuel in a boiler to generate steam or (2) by burning fuel in

the cylinders of a diesel engine.

(A small number of vessels are still fitted with gas turbines similar to an

-aircraft jet engine but these tend to be expensive to run .)

The output of steam may be used directly to drive a high speed turbine

connected to the propeller through a reduction gearbox, (steam turbine) or

to drive a turbine connected to a generator powering an electric motor on

the propeller (turbo-electtic). - *

Diesel engines may be slow speed (approx. 80 to 150 rpm) usually

Griving the propeller shaft directly at the samie speed or medium speed

High speed ferries often use an impeller drawing water into a large pump

and pushing it out as a jet instead of a propeller but this is still powered by

diesel engines.

We will consider boilers, turbines and diesel engines in general terms with

the intention of understanding the complexity of such systems and

possible problems ships engineers may encounter.

Always remember - the last thing an engineer needs when things go

wrong down that big black hole is the master or mate phoning him every

few minutes asking how long it will take to fix !

When on board the ship visit the engine and control room occasionally

(after asking permission) and show an interest in things that go up and

down or round and round.

‘Main propulsion2 July 2001

(© Roy Swan New Zealand Maritime School

Diesel Engines: A general description

Named after Rudolph Diesel, this is a compression ignition engine

burning fuel at constant pressure.

For comparison, a petrol engine is spark ignition buming fuel at

constant volume.

Further, the two main differences between petrol and diesel engines

are the fuel used and when itis added to the air.

In a petrol engine the fuel is drawn in through a carburettor or

injected during the induction (suction) stroke and before

compression occurs..

Ina diesel it is injected after the air is compressed by the piston to a

high pressure (> 15 bar or atmospheres).

Constant pressure means that the fuel continues to be injected from

slightly before Top Dead Centre of the piston to slightly after that.

‘This means that even while the piston is moving down on the power

stroke and volume is increasing in the cylinder, the pressure remains

fairly constant.

It is this feature which gives a diesel engine its good torque

characteristics through a wide range of revolutions.

By comparison in a petrol engine ignition is almost instantaneous

while the piston is at the top of its stroke. These engines only

develop full power over a short range of r.p.m.

Diesel Combustion Cycles:

1. Four stroke cycle. (Suck, squeeze, bang, blow )

a) Induction stroke - The piston is travelling down drawing clean

air into the cylinder through the inlet valve which is open.

b) Compression stroke - The piston travels upwards with both

valves closed thus compressing the air to high pressure. (15 - 30

bar)

As the air is compressed its temperature rises to over 500°C

c) Power stroke - Just before TDC fuel starts to be injected into the

cylinder, continuing for a short period after.

As the auto-ignition temperature of the fuel is only about 400° C it

starts to bum supplying heat and energy. This expanding gas

pushes the piston downwards with a steady force.

Just after fuel injection finishes, the exhaust valve opens to start the

‘outward flow of exhaust gas.

Main propulsion? July 2001

(© Roy Swan New Zealand Maritime School

Exhaust stroke - the piston once again rises pushing the remaining

exhaust gas out. Just before TDC the inlet valve opens and the

cycle repeats.

The short time that both valves are open together is called “valve

overlap” and is necessary to overcome inertia of the air or gas flow.

Most medium and high speed diesels are four stroke. Although

more moving parts are required and power is only produced every

second revolution of the engine, valve opening times and fuel

buming can be better controlled resulting in a quieter and cleaner

engine.

2. The Two Stroke Cycle ( Squeeze, Bang, Change it)

This type of engine is used by GM and Detroit type engines for

their medium and high speed units, and invariably by all slow speed

diesel engines on ships.

This cycle has no induction or exhaust stroke, instead the burnt

exhaust gas is pushed out by the incoming clean air which is blown

in while the piston is at Bottom Dead Centre.

This operation is known as “scavenging”.

Compression and power strokes are the same as the four stroke

engine.

It is the difficulty in achieving a good clean scavenge which is the

problem with higher revving two stroke engines.

In the very short time available it is necessary to blow in sufficient

clean air to blow out all the gas. Various flow designs have been

developed to improve this such as “uniflow” from top to bottom,

“loop” around the cylinder or “cross scavenge” from side to side.

We will soon look at another problem of two strokes, scavenge fires.

Main propulsion2 July 2001 -3-

(© Roy Swan New Zealand Maritime School

Going Astern (aka Reversing or Going Backwards.)

Several methods exist for applying astern power depending on the

type of engine or propeller.

Gearboxes:

In medium speed diesel engines a gearbox is used to reduce engine

evolutions to propeller revs and this usually incorporates a

reversing gear.

Reversing engine:

Slow speed engines may be of the “reversing” type where the engine

timing is changed and its direction of rotation altered.

Controllable pitch propeller (CPP):

The blades of the propeller may be rotated on the hub to alter the

pitch and reverse the direction of thrust.

Steam Turbine:

Most steam turbines contain a single astern turbine blade compared

to about six ahead blades.

This results in very low astern power (30 - 40 % of ahead) on these

ships which must be taken into account when manoeuvring the

vessel.

Main propulsion2 July 2001

(© Roy Swan New Zealand Maritime School

INGE Fl

Scavenging is the act of changing the exhaust gas in a two stroke

engine with fresh air.

To enable this to happen the cylinder has air inlet ‘ports’ around the

base which are uncovered by the descending piston.

Exhaust is usually through a valve at the top of the cylinder but may

be through similar ports on one side of the cylinder.

Air is fed to the inlet ports through a large pipe known as the

scavenge trunk.

In older or worn engines unbumnt fuel and lubricating oil may find

its way into this trunking through the inlet ports.

If not drained off this may accumulate and be ignited by hot carbon

sparks.

Although contained in the trunking the fire is being fed by air and

may cause serious damage to the engine. ‘Thermal damage to the

liner, piston or connecting rod may occur or rubber seals etc. may be

burnt.

Excessive heat through the trunking may spread the fire to other

surrounding areas and materials.

wvenge Fire Indications

Black smoke, Funnel sparks, Engine slows down, Inlet and exhaust

emperatures rise, Visual signs of paint blistering, Smell,

‘Turbocharger and r-p.m variations or surging

‘Actions Required

1. Slow engine down to minimum revs. Avoid stopping which

‘would stop lube oil supply to cylinder. If essential to stop

2. Engine, engage turning gear to keep it rotating.

3. Tum off fuel to affected cylinder to reduce heat

4. Increase lube oil pressure to that cylinder to compensate for

burnt oil on cylinder walls.

5. Boundary cool if necessary on adjacent areas

6. Fire should quickly burn itself out as fuel and air supply to it

are reduced.

7 If fire continues, CO2 smothering may be required but must be

‘used with caution as thermal stress may occur due to rapid cooling

of engine components.

Main propulsion? July 2001 A-s-

© Roy Swan New Zealand Maritime School

Prevention is better than cure:

1. Fire risk can be minimised by regular maintenance and draining of

scavenge spaces.

2. In port, spaces should be regularly manually cleaned of carbon

deposits.

3 Fuel injectors must be maintained in perfect condition to prevent

leakage into cylinder.

Main propulsion? July 2001

© Roy Swan New Zealand Maritime School

(CRANKASE EXPLOSIONS

‘These are a real danger on large diesel engines and legislation

requires alarms to be fitted and special precautions to be taken.

‘The crankcase is the bottom section of an engine in which the

crankshaft rotates.

In small and medium engines the lubricating oil is held in it to be

pumped around the engine. In large engines it is usual to have a

“dry sump’ with the oil held in a separate tank.

Cycle of events:

1 A hot spot may occur in the running gear, eg.a tight bearing

Lube oil being forced around the moving parts such as the

crankshaft comes into contact with the hot metal and vapourises.

This cloud of vapour is too rich too bum but blows around the

crankcase mixing with air. Between 1 and 10% of hydrocarbon gas

mixed with air is in the explosive range.

The flammable gas now migrates back towards the hot spot and is,

ignited, the rise in temperature increasing pressure inside the

crankcase,

If not relieved, the increased pressure blows the crankcase apart at

its weakest point, often the manhole doors.

This allows air to rush in and mix with the unburnt gas, causing a

second, often larger explosion.

Main propulsion2 July 2001 -T-

‘© Roy Swan New Zealand Maritime School

Precautions:

Engines over 1200 kW must be fitted with oil mist detectors which

continually sample the atmosphere from each crankcase bay.

This sample is passed through a device which detects vapour build

up and flammable gas. Each section of the crankcase is compared

with the others and fresh air, allowing early detection of mist build

up.

If detected, an audio and visual alarm is given and the engine may

be slowed down automatically.

Relief valves must be fitted in the casing which are self closing and

deflect any blast away from personnel.

EXPLOSION RELIEF DOOR,

SPRING

+

ENGINE ROOM CRANKCASE

FLASH GAUZE

Action on Oil Mist Alarm:

1 Keep personnel away from crankcase doors and relief valves

2 Slow down or stop engine

3 If explosion appears imminent, evacuate engine room

4 Prepare fire fighting equipment

5 After at least 20 minutes, remove crankcase doors and locate heat source.

Look for discolouration (blueing), squeezed out bearings, feel for heat etc.

‘Main propulsion? July 2001

(© Roy Swan New Zealand Maritime School

EN NTR

To start a diesel engine it must be rotated at sufficient speed to pump fuel to

the injectors and provide heat by compression.

‘On medium smaller engines this is usually done using electric starter motors

powered by 12 or 24 volt batteries.

This is not practical on large engines so the are rotated by allowing

compressed air at about 500 psi. into the cylinders in rotation though an air

distributor.

‘As the engine picks up speed the air is tumed off and the fuel opened. To

avoid over-pressurising the cylinder it is essential that this is done in the

correct sequence. Pressure relief valves are fitted in case of erros.

Most modern engines have an automatic sequence control for starting with

interlocks to prevent damage

‘Common ones are air/fuel , wrong way, overspeed, and braking air.

‘When manual starting controls are provided they comprise an ahead/astern

selection, starting air supply and fuel supply.

‘These may be on three separate controls but often are incorporated into one

‘wheel type control to provide them all.

MANUAL ENGINE CONTROL

‘Main propulsion? July 2001

(© Roy Swan New Zealand Maritime School

STARTING PROCEDURE FOR LARGE DIESEL ENGINES:

PREPARATIONS:

1 Ifa large engine is started from cold the heat will be unevenly

distributed with the piston getting hotter and expanding more

than the cylinder liner. This causes thermal stress to the steel

and may result in the engine seizing up.

It is essential therefore that such an engine is brought up to

working temperature before starting. This is done by

warming the circulating water normally used for cooling

jacket water) to a temperature of about 60° C.

Usually electric heaters are used and water circulated for 3 to

4hours.

2 All tanks, filters and drains are checked. Lubricating oil

circulating pumps are started and oil returns checked.

Starting air pressure is built up to maximum by running air

compressors.

3 Allalarms and data logging equipment is tested.

4 Indicator cocks on top of each cylinder are opened to relieve

compression and the engine tured over with the tuning gear.

(Bridge clearance must be obtained first)

This forces any water which may have accumulated in the

cylinder out of the cock.

5 The fuel oil system is checked and warmed through. Engines

often use medium diesel oil for manoeuvring and heavy fuel

for full away but not always.

6 — During manoeuvring an auxiliary electric air blower may be

used to supplement the engine blower.

7 If maintenance has been carried out special care must be taken

to ensure all tools etc. have been removed from crankcase.

When all turning freely, turning gear is disengaged and engine

kicked over on air only with the cocks open. These are then

closed and engine is ready to start.

‘Main propulsion2 July 2001 A-10-

(© Roy Swan New Zealand Maritime School

STARTING (MANUAL CONTROL):

Ahead or Aster direction is selected in accordance with

telegraph order.

2. The manoeuvring handle is moved to the ‘AIR’ or ‘START’

position. This sends low pressure ‘pilot air’ to the main

starting air valve and air distributor. Air at about 500 psi is

injected into each cylinder in tum depending on the

required direction of rotation.

3. As the engine picks up speed the lever is moved to the “fuel”

or ‘run’ position. This closes off the air pressure and fuel is

pumped up to the injectors and sprayed into the cylinders near

‘Top Dead Centre.

4, The lever is moved to a position to give the required r.p.m.

EMERGENCY STOP:

The lever is moved to the stop position and fuel supply is cut

off.

2. Engine will continue to rotate due to vessels movement

through water.

3. Lever is moved into the Astern position. This moves the

camshaft valve and fuel cams to their astern lobes.

4, Air is admitted in short bursts to slow the engine down and

bring it to stop. Care must be taken to avoid overpressurising

the cylinder except in extreme emergency ( double ring

astern). This may require manually overiding any interlocks.

In such cases the engine must be carefully inspected before

resuming normal running.

LONG STANDBY PERIODS:

If the engine is to stand idle for an extended period, eg. waiting for a

pilot, it is necessary to ensure that it stays at working

temperature and heavy fuel if being used does not solidify in

the lines.

Similar to pre=starting procedure, warmed water is circulated,

sometimes from other machinery such as a generator.

Alternatively the engineers may request the bridge to run the

engine for short periods while waiting.

‘Main propulsion? July 2001 ne

© Roy Swan New Zealand Maritime School

FULL AWAY ON PASSAGE:

‘This notifies the engineers that the ship is in open water and

unlikely to require engine movements without prior notice. It does

not however preclude the deck officer on watch from using the

telegraph or direct engine control at any time it is necessary.

At this time fuel may be changed from diesel to heavy, auxiliary

blowers tumed off, temperatures and pressures stabilised and

standby engineers relieved. It is also usual to shut down any

additional generators that were running in port and switch off one

steering motor. At night the engine room will be set to UMS mode

and the bridge advised.

PUTTING MACHINERY ON LOAD:

This refers to starting the “prime mover” of equipment such as

‘generators, pumps and compressors and connecting them for normal

running.

‘When possible it is desirable to start the diesel engine and run it up

to speed without any load attached. For generators this is achieved

by switching off the electrical load which lets the armature rotate

freely. Compressors can sometimes be “decompressed” by opening

a valve or else connected to the engine by a clutch arrangement.

Small pumps do not generally provide such a great load so are

usually permanently connected to the diesel but may have a clutch.

Main propulsion? July 2001 2

© Roy Swan New Zealand Maritime Schoo!

~ ‘TRANSMISSION OF POWER TO THE PROPELLER

The reciprocating pistons are attached to the rotating crankshaft by

“connecting rods” having bearings at each end, ‘big end’ and

‘gudeon pin’

Larger engines may have a straight rod to the bottom of the piston

and a “crosshead” connecting to the con. rod.

‘This gives a direct up and down force to the piston and avoids wear

‘on one side of the piston and cylinder. The crosshead bearing is

also easier to access and change.

The flywheel:

This heavy wheel attached to the end of the crankshaft absorbs the

pulsating energy of the pistons and delivers it as a smooth flow. It

provides the energy required to push the pistons up on their

- ‘compression stroke.

The gearbox:

Not usually fitted on slow speed diesels which are run at propeller

revolutions but necessary to reduce medium speed diesel revolutions

to propeller revs. (e.g. Engine rpm 1000, propeller 200 rpm

= requires a reduction ratio of 5: 1)

‘The gearbox will also contain a reversing gear for going astern

unless a Controllabel Pitch Propeller is fitted.

The Thrust Block

As the propeller tums and pushes the ship ahead or pulls it astern, its

7 thrust is transmitted up the propeller shaft towards the gearbox or

engine.

It is therefore necessary to pick up this force and transmit it to the

hull of the ship to prevent damage to the gears or crank.

The thrust block consists of a short length of shaft with a steel collar

cast into it and supported in journals (bearings).

The collar rotates between plates on each side containing bearing

pads coated in white metal. A continuous film of oil is maintained

between them to reduce friction and wear.

‘These plates pick up the thrust from the shaft in either direction and

‘transmit it to the hull through the block structure,

This is firmly bolted to specially strengthened hull members in way

of solid floors, close spaced frames and girders and a heavy tank

top.

‘Main propulsion? July 2001 BH

(© Roy Swan New Zealand Maritime School

Intermediate Shafting and Bearings:

Between the thrust block and the tail shaft lie lengths of

intermediate shafting This may be short in all aft ships but

substantial in midships and threequarter aft ships.

‘To prevent it “whipping” out of alignment it must be well supported

at intervals by bearings or “Plummer Blocks” These consist of white

= metal lined bearings in the lower half either with an oil bath or

forced oil lubrication. Large ones may also be cooled by circulating

water.

a The after bearing or ‘trailing block’ may also have a device which

prevents the shaft moving aft in case of fracture further forward.

S The Propeller (Tail) Shaft

This after shaft is the one to which the propeller is attached, having

1 tapered end and threaded section for the propeller nut. It is not

= usual to use a key slot and key on large vessels, instead the propeller

boss is hydraulically pushed onto the taper to give a tight friction fit

known as a keyless propeller fitting.

7 This is done by means of a device known as a “Pilgrim Nut” The

same procedure is reversed to remove the propeller. The propeller

nut is tightened up, locked in positon and a fairing bolted over the

= top of it. The screw thread direction is designed to tighten it while

the propeller is turning ahead,

The Stern Tube:

Usually oil lubricated on modern ships, this provides the final

support for the propeller shafting and a watertight seal between the

sea and engineroom.

Lube oil is supplied either from a gravity feed tank or by pump,

giving a pressure slightly higher than the outside seawater. This

‘ensures that any slight leakage from the after seal results in a trace

of oil leaking out rather than seawater inwards. For obvious reasons

today a regular inspection around the propeller should be made to

ensure no leakage is occuring.

Shafting Connections:

Lengths of shafting may be joined to each other by one of two main

= methods:

1. Flange connection - each length of shaft is cast with a flange at

each end with bolt holes for tightening together.

- 2. Muff Couplings ~ the lengths of shaft are plain at the ends but

gripped together by a surrounding clamp bolted around them. On

large shafts thin wedges are hydraulically pressed between the shaft

~ and the clamp to give a tight friction fit.

The advantage of muff couplings is that the shafts are lighter and

S easier to handle without flanges. On the tail shaft it also means that

the shaft may be removed from the outside if required instead of

into the shaft tunnel.

Main propulsion? uly 2001 oi

‘© Roy Swan New Zealand Maritime School

= EREICIENCY

With the current high cost of fuel efficiency in both the combustion

process and propulsion of the ship are critical. Much research has

‘been done in this area in both hull, propeller and engine design.

Engine:

‘The output power of any engine will always be substantially less

than the heat energy contained in the fuel it burns.

A typical figure of efficiency is 40% - 50% depending upon engine

design, condition, tuning, turbo-charged or naturally aspirated etc.

‘The difference is due to heat and energy losses from a variety of

= causes, the major ones bein,

1 Heat to Exhaust 35%

‘The hot gas remaining after the power stroke must be cleared out by

the scavenge systeme ( 2 stroke) ot the exhaust stroke of the piston

= (4 stroke engines).

In ships main engines some of this heat may be recovered in the

exhaust boiler for other uses such as domestic heating but most is

= generally lost up the funnel.

2 Heat to Cooling System 15%

Because of the physical limitations of lubricating oil which bums at

about 400° C and the melting point of various metals, it is necessary

- to cool the cylinder walls and piston below this figure. This is

usually done by fresh water circulation which in turn is cooled by a

heat exchanger. The heat energy is therefore pumped over the side.

3 Heat to Lube Oil 5%

For the reasons given above and to maintain viscosity the lube oil

must be cooled. This is achieved by passing it through a seawater

cooled heat exchanger.

4 Heat to radiation 5%

This is the heat given off the engine to the surrounding atmosphere,

for example the hot air being changed by the engine room exhaust

fans or venting out of the engineroom skylight.

: Total Wasted Energy 60% Available to Power Ship 40%

Obviously all the above figures are approximate and depend upon

- actual plant and operating conditions.

See video “Energy savings at sea”

Main propulsion? July 2001 A -1s-

© Roy Swan New Zealand Maritime Schoo!

Propeller Efficiency:

Fixed pitch propellers are designed as a compromise of the best

efficiency for average conditions on a particular ship, for example

light or load draught, trim, weather conditions, engine r.p.m etc.

Even with the best design a slip factor of about 5% can be expected

due to cavitation effects. Later notes will cover calculations on

propeller pitch and slip problems.

Controllable Pitch propellers involve a higher capital cost but as

pitch can be continually adjusted to suit current conditions long term

increases in efficiency are possible.

A big advantage is obtained in manoeuvrability as ahead to astern

movements can be quickly made without changing gear or reversing

the engine.

‘Therefore, offsetting the higher cost in medium speed plants is the

non-requirement for a reversing gearbox and in slow speed engines

no reversing cams are required as engine is also uni-directional.

A small loss in efficiency is incurred due to the requirement for a

larger hub than fixed pitch. Blades are usually bolted on

individually so may be exchanged easier in case of damage.

Load Control:

To take full advantage of a CPP the pitch should be continually

adjusted automatically throughout the voyage to obtain maximum

efficiency.

Load control systems such as KaMeWa use input from the actual

propeller revolutions and the fuel pump setting.

This information is used to make continuous pitch corrections.

The maximum change of pitch is proportional to the ordered pitch

with regard to size and direction. For instance at full ahead quite

large variations could be made while at dead slow only small ones

would occur. At stop position requested, propeller is still rotating

bbut blades feathered for zero thrust so no variations in pitch would

be allowed.

‘This system also protects the engine from either over speed or over

loading in situations such as crash stop, navigation in ice or sailing

in heavy weather and pitching heavily.

During a crash stop the shortest stopping distance is achieved by

minimising cavitation effects.

In the longer term best efficiency is maintained even as hull

becomes fouled between dry dockings.

ACPP also allows the shaft to run at constant r.p.m if required for

shaft driven alternators.

‘Main propulsion2 July 2001 -16-

‘© Roy Swan New Zealand Maritime School

sat eh te

: ors

feuencuPereny

ne

ne a,

> ruinces

- 2 sins

eruinser

PISTON

CONNECTING

acd)

, CRANK

E ia ae PEN

! CRANK

7 0 To SHAFT

2 “. oe

. |

INGUCTION STROKE COMPRESSION STACKE

Exhaust gas. | Fresh air

Gas 5 | Rotary air

turbine 2 [oiphater

: 3

rut ,

Rocker arm injector Air cooler

: L Cinder eed

exhaust Inletvave

Pushrod ——T |__—water cooling

Piston | ‘Piston rings

Exhaust

ginaust Le QO Q-—inetrabecan

Gudgeon pin | os

Gucgeo Cylinder liner i

| comecinared

Crankcase_

door

cankease i

; | Bottomend —j

i __. . ~ ‘bearing i

1 i 1

= : tf

_ wll.

Crankshaft Of i

i

i

Figure 2.19 Four-stroke medium-speed diesel engine.

#20

fe

15 MATE ENGINEERING OPERATIONS

SECTION B

PUMPS AND PUMPING

SYSTEMS

PUMPS AND PUMPING SYSTEMS

Theory of pumping:

Pump suction

Almost all pumps use atmospheric pressure as part of their operating

principle so are limited as to suction height.

Average pressure over the Earth is about 1013 hPa or about 14.5 p.s.i.

This will support a column of mercury of around 760 mm or a column of

water 10.4 metres.

PRESSURE (Pa) =HXDXG

Where H = height in metres

D= density in kg./ m*

G= gravity (9.81 m/s”)

QU. Height of barometer = 760 mm

Denisity of mercury = 13600 kg/m?

Find atmospheric pressure:

QZ If the atmospheric pressure is 1020 hPa, find the maximum lift of

salt water by a pump whose efficiency is 80%

The maximum suction lift for a perfect pump with no air leaks would

therefore be limited to just over 10 metres. In practice it will be

considerably less than this.

Bi

Pump Discharge:

Although the lifting height of a pump is limited due to atmospheric

pressure, once the liquid is in the pump it may be pushed to any height

required, subject only to the power of the pump and strength of the piping.

Practical Pumps on Board Ship:

‘Many different types of pump are used on ships to cover the large range of

pumping requirements.

Choice of pump type will depend on liquid to be pumped, temperature and

viscosity , pressure or volume required, continuous or intermittent service,

prime mover type i.e., electric motor, steam turbine, diesel engine etc. and

initial cost.

Pumps may be split into two main groups, positive displacement and non-

positive displacement. The former are self priming while the latter are

not and must be filled with liquid before use.

For example, a piston or diaphragm pump is self priming while a

centrifugal pump is not.

A simple test of which group a pump belongs to would be to close the

discharge valve with the pump full of liquid and see if it can be moved.

A positive displacement pump would lock up in theory, although in

practice there is always a relief valve fitted to prevent this occurring.

The attached sheet shows a selection of pump types typically found on

board ship.

By far the greater majority of general use pumps are centrifugal as these

are easily driven by electric motors, have few moving parts and are very

reliable.

They tend to have a high volume output but at lower pressure than piston

type pumps. They can however be ‘multi-staged’ if increased pressure is

required such as boiler feed or high discharge height.

R2

ROTARY VANE yp

RUBBER IMPELLER ROTARY

. VANE PUMP.

TP esitie impeter biades upon te As inpeler roe, each succesive

GJABSCO TYFE) iby ote cam. erste a neatly pers Slade don a Hew and ein

[etvacaum forimastadlprinoy, fm ur owe po.

; 8s

Whee dexble impeller blade apts

eouact theo ‘hey bene

iba squeenng azton that pro

j TEI

g

a? Ez >

BE Be ze

= ol88, las, | 8 Bo lel, |g

| § 2/8 8.[830] $0 | we (Ssalzhe| Se [2

2e2|222|223| 33 | 8s SeSlg6$| 25 Gus

BHeSee|8oex| S2 | SP |SSz/esz2| S2 are

SEA s|s|{s]s Stn)

HOTWELL OR

FEED TANK s|s D

4——_}

jexwst

1 TANKS Fe) sD

RESH WATER

D.B, TANKS s s : s

ENGINE ROOM T

BILGE Seleslesuies

+ i.

MAIN

BILGE LINE s s|s

1

CONDENSER

CONDENSATE s

BOILERS plo

OVERBOARD pd |.

CONDENSER

WATER-BOX dD |.

WASH-DECK AND

FIRE-SERVICE D pd |. o|o

SANITARY

TANKS D D >

1

FRESH WATER

HEAD TANKS. D D -|o

FORE AND AFT

PEAKS

3.8 CARGO PUMP AUTOMATIC STRIPPING SYSTEM (PRIMAVAC)

Prowwdnc snk vale 6 teerewltiy Dia 4 sported by

verte ffl onl Haate hak 0 a2 tage

ae On qucliin ve opto

oul) oh ew pepe obene. pep he beck E Cab,

wntennel call, hen ptned . &s

Electric motor.

Motor/Shaft coupling.:

Shaft seal.

Electric cable junction box.

Standard Bulkhead piece

at Tank top.

Cargo Tank centreline

bulkhead.

\}- Electric cable led up bulkhead,

clipped to stiffener flanges.

6” Discharge pipe led up

bulkhead. Aluminium alloy

No flanges.

DEEPWELL ELECTRICAL

PUMP SUBMERGED PUMP

ARRANGEMENT ARRANGEMENT

Drive Shaft inside Bellows expansion joint,

dischar; pe.

Cae Pump rigidly fixed

Intermediate bearings (8) to bottom structure.

Cable junction box. i

Electric motor.

Guides to allow pump

Alternative

contraction.

position,

Alternative Pump arrangements for U.K. ships.

Reference: Roger Ffooks, Natural Gas by Sea, Gentry Books,

London, 1979, p67.

i

15 MATE ENGINEERING OPERATIONS

SECTION C

CONTROL ENGINEERING

1" MATES / MASTER_ENGINEERING OPERATIONS

CONTROL ENGINEERING

Control engineering covers many fields of industry, we will look at those

which relate to the automatic control of ships systems such as boiler water

level or combustion, control of the main engine and auxiliarys and auto pilots.

Definitions:

Loops

Alll control systems are classified into ‘open’ or ‘closed’ loops.

‘Open loop is one in which the control action is independent of the output, e.g.

‘an automatic toaster, washing machine etc.

Closed loops have a feedback system which supplies continuous information

about the output to the controller.

Loops may be manually or automatically closed, for example the man on the

‘wheel steering the ship or the auto-pilot.

Measured Value

‘The actual condition of the controlled system as relayed by a transducer to the

controller e.g. temperature, level, pressure etc.

Desired Value ( Set Value)

The value of the control action that we wish to obtain, for example the

pressure of the boiler, course of the ship.

Error or Deviation

‘The difference between the desired value and the measured value

Offset

Sustained deviation — the measured value remains constantly above or below

the desired value. Offset is an inherent property of proportional control and

will increase as the load increases.

Feedback

Property of a closed loop that allows the measured value to be compared with

the desired value.

‘Transducer

‘A device to measure and transmit information to the controller.

a.

‘Comparison Device

Compares measured and desired values and gives an output of the error signal.

Regulator

A valve or similar device which can be opened and closed to adjust the supply

of mass or energy to the system. E.g. rudder, fuel valve, feed water check

valve etc.

‘Actuator

‘A powered device which operates the regulator in accordance with control

signals e.g. steering motor, hydraulic or electric valve motor.

Controller

Unit which converts the error signal into a form suitable to operate the

regulator e.g. voltage to hydraulic pressure.

Amplifier

“Step up’ device to convert a low energy signal into a higher one.

‘The degree of amplification is known as the ‘gain’.

Continuous Control

Where the output of a system is continuously monitored and the input

continuously adjusted to maintain the desired level e.g. boiler water level,

steam pressure, ships course etc.

Discontinuous Control

‘System having only two basic modes, ‘on’ and ‘off’. Provided the output

remains between two set limits the input is ‘off’, if output falls outside the

limits then the system input is switched ‘on’.

‘This is typical of simple room heating thermostats and refrigeration systems.

Note: In practical systems many of the above items may be combined into a single

unit or circuit board.

seeeeeeeenees

c2

AUTOMATICALLY CLOSED LOOP

c3

RoPORTIONAL. CONTROL.

Liquid In

Drain Valve

Liquid Out

Ball-cock. Example of proportional control

re £

™ Conta point

ofter disturbance

Tine ———e Ck.

+ Response of process with proportional controller to step-change input

(CONTROL FUNCTIONS:

Three main types of control will be considered, Proportional, Integral and

Derivative.

Each acts according to different parameters and is used depending upon the

degree of control required, for example how much can we accept the water

level in a tank varying, how much can the ship yaw off course and how long

can it stay there before rudder is applied.

Proportional control is the only one which can be used on its own. It may

however be combined with Integral only or Integral and Derivative to give two

and three term control respectively.

‘A simple example of a tank of water is used to illustrate only the concepts of

control. Practical systems will be much more sophisticated.

PROPORTIONAL CONTROL

THE OUTPUT OF THE CONTROLLER IS IN DIRECT PROPORTION TO THE

MAGNITUDE OF THE ERROR.

CONTROLLER OUTPUT = ERROR MAGNITUDE _X CONSTANT (Kp) ]

In the first diagram a simple ball cock arrangement is shown in a tank. Itis

required to keep the water at its present level.

Note: The tap is able to supply water at a rate at least equal to the maximum

outflow of the drain.

‘When the drain (load) is closed the water is at the correct level and the tap is

closed. If the drain is now opened part way the water level will fall and the

ball lever will open the tap proportionately according to the position of the

pivot.

At some level the tap input will equal the drain output and the level will

remain constant. This however is not the desired level and the difference is

known as the “offset”.

If the drain is opened further the level will fall more until the tap opens more

and équilibrium is again reached. “Offset has therefore increased with the

bigger load.

Offset is an inherent problem with proportional control.

It may be reduced by moving the pivot or fulcrum so that the tap opens more

for a given fall of the ball, ie. the proportion is altered.

If done too much however the system will become unstable so that a ripple

across the surface would result in a gush of water from the tap.

Example: Simple autopilot applies rudder only according to the amount by

which the ship is off the set course. 5° off course = 3° rudder,

10° off course = 6° rudder.

INTEGRAL CONTROL

cs

INTEGRAL CONTROL

MOTOR MAINS

Liquid In

Drain Valve

Liquid Out

‘Ball-cock example with mechanism modified to produce integral mode control action

Leos

Proce

Time

Response of process wich integral controller to step-change input

ck

THE OUTPUT OF THE CONTROLLER VARIES WITH THE MAGNITUDE OF THE

ERROR AND THE TIME FOR WHICH IT HAS EXISTED

CONTROLLER OUTPUT = ERROR MAGNITUDE _X TIME X CONSTANT (Ki)

In the second diagram an electric motor has been fitted to the tap and attached

to the ball cock with a variable speed controller.

Now as the drain is partly opened the water level will fall and the dropping,

ball will cause the tap to start opening. The speed of opening will increase as

the ball drops further.

At some point the tap input will equal the drain output and the level will stop

falling. ‘The tap is still opening however so the level will start to rise.

‘When it reaches the original level the tap will have stopped turning but still be

‘open. The water will therefore rise above the desired level until the tap is

closed, at which point it will start to fall again. The cycle then repeats this

oscillation about the desired level.

‘The important point to note is that that even ifthe level only falls a few

millimeters below desired level, the tap will start to open very slowly, but

continue to open until level starts to rise again. Control function is therefore

dependant upon the time that the error has existed as well as its magnitude.

Integral control would be no use on its own as the level oscillates up and

down. Combined with proportional control however it will reduce the offset

to zero.

Proportional and Integral control is commonly used and known as “Two Term

Control”

Example:

Ships autopilot. If the ship is off course slightly but for an extended period

integral control would bring it back to the correct heading.

2° off course for 1 minute = 3°rudder, for 2 minutes = 6° rudder

Cc}

DEI INTROL,

THE OUTPUT OF THE CONTROLLER IS IN DIRECT PROPORTION TO THE SPEED

AT WHICH THE ERROR IS INCREASING.

CONTROLLER OUTPUT = CHANGE OF ERROR X CONSTANT (Kd)

TIME

In the third diagram a centrifugally operated valve is fitted to the tap.

‘This will only open the tap while the level inthe tank is falling quickly.

If the level is steady, falling slowly or rising the tap will remain closed.

If fited on its own the water in the tank would eventually empty with the tap

opening intermittently.

Fitted in conjunction with proportional and integral control however derivative

will arrest any error which occurs suddenly, preventing a drop in level before

the other two controllers cut in.

‘An example on autopilot would be the immediate application of opposite

rudder ifthe ship was swinging quickly off course or swinging back too

quickly towards the set course.

PRACTICAL SYSTEMS

These use mechanical, hydraulic, electrical or pneumatic methods to achieve

the required control actions.

‘The diagram shows a three term controller using mechanical levers for

proportional, pneumatic for the integral and hydraulic for derivative control.

‘When the drain valve is opened the float drops and the levers open the supply

valve by an amount in proportion to the position of the fulcrum.

‘Atthe same time the integral valves move down allowing air to flow

underneath the piston which will start to rise and lift the piston more and more

‘as time increases.

‘The derivative controller consists of a piston in a cylinder of oil, suspended

between two springs. The piston has a small hole in it for oil to flow through.

if the level drops quickly the lever pushes the piston and its cylinder down.

‘The oil then flows through the hole and the piston centralizes.

If the tank level is falling slowly the piston can move down without moving its

cylinder as the oil flows through the hole.

<3

DRWATIVE CONTROL

—— Liquid In

Drain Valve

Liquid Out

Ball-cock example modified to produce derivative action

cy

| PRAcTICAL — SYSTEH

THREE TERM CoWT ROL

iG teuuest

2 yportonal

om |

re_L i [over Deswrea

| a value

=-

ree oe 7

Qutout veto & * ‘action 4) } Outout dueto <

Broparuanal | jp ntesetaction iY

~ Beton >

, Ga T

\

=" Suooy [epbamane

x,

= a

| Example of proportional plus integral plus derivative control

| action.

C10

S29004

: [- VupyaLxd o

Uv

vane] (vetnan3y) t RemnasMryL)|

wap | (Haasas) eo ce

aeuaan aoe dts OWKD

j T

i

( ssyn02

se aveszy)

pyianpw) iy vaastare a

ee “ TayesuaW

r

Coy

CQarsrany negro} | ves

yaniaey *eeLNOS hen cd Dr 1n3a

ava pvlya 31s MeyLNoD (Mos wYyWo>

(sree davisaq)

POWN 135

ae maisras| | waaay

ra | A335

42s sess

We OMT B02 WAT VW WBELET a yee yo)

~ViSisKs”

a

157 MATE ENGINEERING OPERATIONS

SECTION D

TRANSDUCERS

ACUTATORS

REGULATORS

TRANSDUCERS

‘A transducer has been defined as a device which can measure a parameter

such as level, temperature, pressure etc. and transmit the information to a

remote location.

‘The signal from the transducer may be electrical pulses, varying voltage, air

pressure (pneumatic), mechanical or hydraulic.

Sometimes a combination of these is used.

Level Measurement:

Several methods to measure the level of liquid in a tank are available.

Float Gauge:

‘Sometimes referred to as a ‘Whessoe * gauge

after the original manufactures.

A float sits on top of the liquid surface and is

held in position between two guide wires from

top to bottom of the tank.

A tape runs up from the float to a self coiling.

spool on the outside of the tank.

Rotation of the spool is shown by a visual

counter as depth or ullage of liquid and

transmitted by low voltage signals to the control

room.

‘A hand key or motor is fitted to wind the tape up

to the top when not in use to prevent damage by

rolling motions or tank washing machines.

Pneumatic Gauge (Pneumicator)

A low pressure air flow is supplied to a pipe

running down into the tank (or down to the keel

for draught gauges).

For manual use a three way valve is fitted

which is first used to purge the tank pipe of

liguid. The valve is then moved to the ‘read’

position. Air is shut off and liquid in the tank

‘creates a back pressure up the line and along toa

pressure gauge.

The most common thermometer is the mercury or alcohol in glass type but these are not

able to transmit the information readily so other methods are used in transducers. Among

‘the most common are: -

Resistance Thermometer:

Electricity is conducted through metal by the free electrons in the atoms jumping from

‘one to another. if the metal is heated expansion causes the atoms to move further apart

thus increasing the resistance to electrical flow. Ifa steady current of electricity is

passed through metal the voltage drop across it will be proportional to the temperature.

This type is commonly used in all applications such as engine cooling systems both

ashore and afloat,

Thermocouple

‘Thermocouples are pairs of dissimilar metal wires joined at least at one end, which

generate a net thermoelectric voltage between the open pair according to the size of the

temperature difference between the ends,

Bi-metallic strip:

‘Two different metals fused together, e.g. Brass

and steel, will have different coefficients of

expansion causing them to bend upwards

towards the lesser expanding one.

This ean bé uséd to make a switch contact at

set temperature (thermostat), or by connection

to a variable resistance, to transmit a voltage,

whieh is proportional to the temperature,

Other methods of measuring and transmitting temperature include Radiation sensors,

Infra red sensors and expanding gas types.

Flow Measurement

Devices, which measure flow of liquid in pipelines, can be likened to ships logs, which

measure flow of water past the hull. These include:

Rotating impeller:

‘An impeller is fitted in the line ( or a

branch sampling line) in the flow of

liquid. Magnetic sensors send signals as

it rotates in the flow proportional to the

velocity.

Knowing the velocity of flow and

diameter of the pipe, flow rate is

calibrated.

Pressure type:

The liquid flow pushes against a piston

or diaphragm with a pressure

proportional to the flow rate. An

equalizing device is fitted to ensure that

no flow is recorded in the case of

pressure in the fine dus to a valve being

closed upstream.

Relative Humidity

This is often required for cargo

ventilation purposes. One type uses an

absorbent cotton roll with a resistance

thermometer in the center and @ heating

element around the outside.

Using the principle of “evaporation

causes loss of heat”, the damper the

cotton roll is, the lower the temperature

at the thermometer.

The temperature output is a voltage,

which is proportional to the R.H.

Pressure can be measured by means of a

“Bourdon Tube”, a spiral of hollow tube

into which the pressure is fed. The

pressure causes the tube to straighten and

this movement can be detected by a

variable resistance to give a voltage.

Other ways of measuring pressure

inglude diaphragms (rubber discs) and

__Jpiatpas pushed into cylinders against

“epemi Preasure.

De

\CTUATORS AND REGULATORS:

‘Actuators are the mechanisms that actually move the regulator, such as a motor or

diaphragm which lfts a valve.

Commonly used on board ship are pneumatic (air pressure), lydraulic (oil pressure) and

electric ( motor or solenoid).

In addition to these of course are the manual actuators such as valve wheels, levers and

hand hydraulic pumps

Pneumatic:

Air pressure is used to push against a piston or diaphragm.

As THRUST = PRESSURE X AREA large forces are possible even at low air

pressures even though quite large diaphragms are required in comparison to hydraulic.

eg. using a diaphragm of 200mm diameter, and air pressure of 0.5 kg/cm?

(5 bar or 7 psi)

Area=nr = 3.14 x 10°%cm =314cm? Thrust= 157kg.

Advantages:

Air is an unlimited resource, at low pressure leaks are harmless.

Compression is easy and compressed air is transportable in small quantities.

Itis not seriously affected by moisture or extremes of temperature,

Disadvantages

Because it is compressible air in the line absorbs some of the compression energy before

it reaches the diaphragm and may cause a slight delay in reaction,

DS

Hydraulics:

May be used at either high or low pressure using small diameter or large diameter pipes

respectively.

Because oil is not compressible reaction time is instantaneous provided no air bubbles or

water vapour are present in the fluid.

Advantages:

Very high forces are possible using small size motors, either piston or rotary vane design

Disadvantages:

High pressure pumps and storage bottles are required. Leaks result in loss of oil with

resulting feilure of power, danger to personnel from high pressure and slipping in oil

lost.

Relatively expensive motors and pumps are required.

Oil must be kept scrupulously clean. It absorbs moisture with resulting loss in

efficiency.

Electrics:

Advantages:

Very versatile, may be used at high or low voltages as required. Easily amplified and

controlled by electronic circuits.

Actuators can be by electric motors or solenoids.

Disadvantages:

Subject to disruption by moisture,

Fire risk if insulation or circuit breakdown.

Special sealed units (intrinsically safe) must be used if risk of explosive atmosphere.

saneee

ily

i

18 MATE ENGINEERING OPERATIONS

SECTION E

MAIN ENGINE CONTROL

MAl ROL SYSTEM

‘The syllabus requires an understanding of the way that diesel and turbine

engines are controlled, using the technique of block diagrams.

‘This requires the student to consider the problem in steps and build up a

suitable system, rather than trying to memorise a particular diagram from the

book.

To this end, students are to work individually or in small groups to look at

each requirement listed below.

A.class session will then be held to put together the ideas.

To get started a short example is given using an autopilot and manual steering

control system.

Technique

First decide the parameters which are to be controlled, eg... pressure, rpm,

fuel, temperature etc. and which are critical.

Decide whether one, two or three term control is justified, i.e, proportional

only, proportional and integral or proportional plus integral plus derivative.

Determine what needs to be in the feed back loop and where fed to.

Decide what interlocks are required and show them in the diagram.

‘Show what alarms would be required in the system

Diagrams are required for bridge control of:

1, Steam turbine with associated boilers

2. Slow speed two stroke engines

3. Medium speed diesels with either a reversing gearbox or CPP.

Also:

4, Control of a cargo or ballast system

5. Conrol of humidity in a dry cargo space

eennee

Control by autopilot and manual helm, example of flow chart:

SHIP

&

—>

STEER

>| GEAR |<

GYRO

RUDDER REPEATER

ANGLE

SET

COURSE,

P+

SIG.

MAN ON

WHEEL | *

AUTO)

ERR

SIG

>

CoMP’N [—— >| CONTR

DEVICE

UNATTENDED MACHINERY SPACES (UMS)

SOLAS Regulations 46 to 54 cover the IMO’s guidelines on unattended

machinery spaces in ships at sea. Regulations 46 to 53 refer to Cargo

Ships and regulation 54 is reserved for Passenger Ships.

General Requirements: The arrangements provided shall be such as to

ensure that the safety of the ship in all sailing conditions, including

manoeuvring, is equivalent to that of a ship having machinery spaces

manned.

Measures shall be taken to the satisfaction of the Administration to ensure

that the equipment is functioning in a reliable manner and that

satisfactory arrangements are made for regular inspections and routine

tests to ensure continuous reliable operation.

Every ship shall be provided with documentary evidence, to the

satisfaction of the administration, of its fitmess to operate with

periodically unattended machinery space.

Fire Precautions: Means shall be provided to detect and give alarms at

an early stage in case of fires:

(@) in boiler air supply casings and exhausts (uptakes); and

(©) in scavenging air belts of propulsion machinery,

unless the Administration considers this to be unnecessary in a particular

case.

Internal combustion engines of 2,250 kW and above or having cylinders

of more than 300mm bore shall be provided with crankcase oil mist

detectors or engine bearing temperature monitors or equivalent devices.

Protection against Flooding: Bilge wells in periodically unattended

machinery spaces shall be located and monitored in such a way that the

accumulation of liquids is detected at normal angles of trim and heel, and

shall be large enough to accommodate easily the normal drainage during

the unattended period.

Where the bilge pumps are capable of being started automatically, means

shall be provided to indicate when the influx of liquid is greater than the

pump capacity or when the pump is operating more frequently than would

normally be expected. In these cases, smaller bilge wells to cover a

reasonable period of time may be permitted. Where automatically

controlled bilge pumps are provided, special attention shall be given to oil

pollution prevention requirements.

‘The location of the controls of any valve serving a sea inlet, a discharge

below the waterline or a bilge injection system shall be so sited as to

allow adequate time for operation in case of influx of water to the space,

having regard to the time likely to be required in order to reach and

operate such controls. If the level to which the space could become

flooded with the ship in the fully loaded condition so requires,

arrangements shall be made to operate the controls from a position above

such level.

Control of Propulsion Machinery from the Navigation Bridge: Under

all sailing conditions, including manoeuvring, the speed, direction of

thrust and, if applicable, the pitch of the propeller shall be fully

controllable from the navigation bridge.

Such remote control shall be performed by a single control device for

each independent propeller, with automatic performance of all associated

services, including, where necessary, means of preventing overload of the

propulsion machinery.

The main propulsion machinery shall be provided with an emergency

stopping device on the navigation bridge which shall be independent of

the navigation bridge control system.

Propulsion machinery orders from the navigation bridge shall be

indicated in the main machinery control room or at the propulsion

machinery control position as appropriate.

Remote control of the propulsion machinery shall be possible only from

one location at a time; at such locations interconnected control positions

are permitted. At each location there shall be an indicator showing which

location is in control of the propulsion machinery. The transfer of control

between the navigation bridge and machinery spaces shall be possible

only in the machinery space or in the main machinery control room. The

system shall include means to prevent the propelling thrust from altering

significantly when transferring control from one location to another.

ey

It shall be possible for all machinery essential for the safe operation of the

ship to be controlled from a local position, even in the case of failure in

any part of the automatic control systems.

The design of the remote automatic control system shall be such that in

case of its failure an alarm will be given. Unless the Administration

considers it impracticable, the present speed and direction of thrust of the

propeller shall be maintained until local control is in operation.

Indicators shall be fitted on the navigation bridge for:

(a) propeller speed and direction of rotation in the case of fixed pitch

propellers; or

(b) propeller speed and pitch position in the case of controllable pitch

propellers.

The number of consecutive automatic attempts which fail to produce a

start shall be limited to safeguard sufficient starting air pressure. An

alarm shall be provided to indicate low starting air pressure set at a level

which still permits starting operations of the propulsion machinery.

Communication: A reliable means of vocal communication shall be

provided between the main machinery control room or the propulsion

machinery control position as appropriate, the navigation bridge and the

engineer officers’ accommodation.

Alarm Systems: An alarm system shall be provided indicating any fault

requiring attention and shall:

(a) be capable of sounding an audible alarm in the main machinery

control room or at the propulsion machinery control position, and

indicate visually each separate alarm function at a suitable

position;

(b) have a connection to the engineers’ public rooms and to each of

the engineers’ cabins through a selector switch, to ensure

connection to at least one of those cabins, Administrations may

permit equivalent arrangements.

(c) activate an audible and visual alarm on the navigation bridge for

any situation which requires action or attention of the officer on

‘watch;

(@) as far as practicable be designed on a fail-to-safety principle; and

(©) activate the engineers’ alarm if an alarm function has not received

attention locally within a limited time.

The alarm system shall be continuously powered and shall have an

automatic change-over to a stand-by power supply in case of loss of

normal power supply.

Failure of the normal power supply of the alarm system shall be indicated

by an alarm.

The alarm system shall be able to indicate at the same time more than one

fault and the acceptance of any alarm shall not inhibit another alarm.

Acceptance at the position referred to in the first paragraph of any alarm

condition shall be indicated at the position where it was shown. Alarms

shall be maintained until they are accepted and the visual indications of

individual alarms shall remain until the fault has been corrected, when the

alarm system shall automatically reset to the normal operating condition.

Safety Systems: A safety system shall be provided to ensure that serious

malfunction in machinery or boiler operations, which presents an

immediate danger, shall initiate the automatic shutdown of that part of the

plant and that an alarm shall be given. Shutdown of the propulsion system

shall not be automatically activated except in cases that could lead to

serious damage, complete breakdown, or explosion. Where arrangements

for overriding the shutdown of the main propelling machinery are fitted,

these shall be such as to preclude inadvertent operation. Visual means

shall be provided to indicate when the override has been activated.

Special Requirements for Machinery, Boiler and Electrical

Installations: The special requirements for the machinery, boiler and

electrical installations shall be to the satisfaction of the Administration

and shall include at least the requirements of this regulation.

The main source of electrical power shall comply with the following:

(a) Where the electrical power can normally be supplied by one

generator, suitable load-shedding arrangements shall be provided

to ensure the integrity of supplies to services required for

propulsion and steering as well as safety of the ship. In the case of

loss of the generator in operation, adequate provision shall be

made for automatic starting and connecting to the main

switchboard of a stand-by generator of sufficient capacity to

permit propulsion, steering and to ensure the safety of the ship

with automatic restarting of the essential auxiliaries including,

where necessary, sequential operations. The administration may

dispense with this requirement for a ship of less than 1,600 gross

tonnage, if it is considered impracticable.

(b) If the electrical power is normally supplied by more than one

generator simultaneously in parallel operation, provision shall be

made, for instance by load shedding, to ensure that, in case of loss

of one of these generating sets, the remaining ones are kept in

operation without overload to permit propulsion and steering, and

to ensure the safety of the ship.

(©) Where stand-by machines are required for other auxiliary

machinery essential to propulsion, automatic change-over devices

shall be provided.

The control system shall be such that the services needed for the

operation of the main propulsion machinery and its auxiliaries are

ensured through the necessary automatic arrangements.

An alarm shall be given on the automatic changeover.

An alarm system shall be provided for all important pressures,

temperatures and fluid levels and other essential parameters.

‘A centralized control position shall be arranged with the necessary alarm

panels and instrumentation indicating any alarm.

Means shall be provided to keep the starting air pressure at the required

level where internal combustion engines are used for main propulsion.

Special Considerations in respect of Passenger Ships: Passenger ships

shall be specially considered by the administration as to whether or not

their machinery spaces may be periodically unattended and if so whether

additional requirements to those stipulated in these regulations are

necessary to achieve equivalent safety to that of normally attended

machinery spaces.

You might also like