Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Learning Process On State

Uploaded by

Axmed Sidiiq0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

8 views2 pagesOriginal Title

learning process on state

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

8 views2 pagesLearning Process On State

Uploaded by

Axmed SidiiqCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 2

s Working Paper is part of an initial DFID learning process on state-building.

The aim of this work has

been to establish some language and concepts that aid our understanding of how states do or do not

work, helping us to identify areas for further research and for future guidance. In the process this phase

of work has engendered a rich debate among international experts and development practitioners. The

work on state-building has underlined the centrality of states within development, and has also

highlighted the potential for donors to both help and hinder their improvement. Development is now

premised on engagement with states, and it is assumed that these operate in a recognisable and familiar

way. The international architecture for economic, political and development co-operation are all based

on assumptions about state capability and structure. Yet the reality of states and their ability to function

is more complex than either our assumptions, or international architecture, would suggest. It has also

been argued that in many ways the global environment for state-building is now worse than ever

before.1 Given this context, this paper suggests that looking more closely at `state-building’ allows

international actors to consider underlying realities, putting social, economic and political analysis into a

historical context. In so doing it helps us to accept that some states may never look similar to our own

(and indeed given the realities of their own contexts, why they probably shouldn’t). The need to better

understand state-building is not an academic exercise; states are crucially important to the future of

those who live under their jurisdiction. It has been suggested that there are over 40 fragile and conflict

affected states;2 those most off-track in reaching the MDGs and least likely to enjoy growth and poverty

reduction. It is an urgent priority for development actors to support positive state-building processes

and to avoid harming any progress that is being made. This paper suggests that applying a state-building

lens has potential to improve the impact of aid, while failure to consider these issues will reduce the net

overall benefit brought by aid programmes. This paper therefore provides a way for readers to

understand states, and the processes that drive their development. Section Two outlines language and

key concepts for state-building; drawing on political-science, governance and economic literature to set

out definitions that can underpin models of how these processes work. Section Three puts forward two

conceptual frameworks, or models, for statebuilding dynamics. The first is a model of how state-building

can work to produce capable, accountable and responsive states, this is described as responsive

statebuilding. The second is a model of unresponsive state-building, a set of dynamics likely to lead to

states affected by problems such as endemic rent-seeking or political repression. Section Four looks at

those factors that are likely to influence the direction of state-building, including issues that are shaped

by policy decisions. 1 A point argued by Mick Moore and Sue Unsworth, of IDS, in their contributions to

the DFID state-building consultation process. 2 Using OECD-DAC definitions States in Development:

Understanding State-building page 4 Finally Section Five draws some initial conclusions on the

implications of this work for donors. Section Two: Concepts and Terminology Dialogue on state-building

is often blighted by the use of common terms without common meanings, we therefore need to offer

some definitions of the key concepts involved. Perhaps no concept is more central to the discussion than

that of the State. States have become the dominant model for organising societies within defined

territories.3 The process by which territories and peoples become identified with these distinct

organisational structures is often termed state-formation (a process that may occur through separation

from a larger state structure or colonial power). State structures are the visible embodiment of the idea

of the state: the Ministries, agencies and forces created to act on the instructions of the individuals who

have gained political decision making power (governments). State-building is the process through which

states enhance their ability to function.4 The aims of this `functionality’ will differ (affected by factors

such as government priorities), and may or may not emphasise areas orientated to the public good.

Therefore state-building is a value neutral term, our preference is that it lead to effective economic

management with political and economic inclusion, but it is not inevitably so. State-building takes place

in all states, whether rich or poor, resilient or fragile, all states are seeking to make their structures

better at delivering on the goals of government. Importantly, members of the international community,

collectively or individually, do not `do’ state-building outside their own borders. State-building is a

national process, a product of state-society relations that may be influenced by a wide variety of

external forces (including trade or the media as much as aid), but which is primarily shaped by local

dynamics The structures of the state are determined by an underlying political settlement; the forging of

a common understanding, usually among elites, that their interests or beliefs are served by a particular

way of organising political power.5 A political settlement may survive for centuries, but within that time

decision making power is likely to transfer among elite groups as individual governments come and go.

Elites are prominent within the literature on statebuilding, but elites can rarely take social

constituencies for granted, they must maintain an ability to organise, persuade, command or inspire.

Wider societies are not bystanders in political settlements or state-building. Adrian Leftwich points out

that political settlements now mostly adopt the structures of the `modern’ (legal-rational) state (rather

than say `feudal’ structures). The `modern’ state usually includes a political executive and separate,

permanent and professional structures to implement policy, s

You might also like

- Building State Capacity in A Post ConfliDocument14 pagesBuilding State Capacity in A Post ConfliWaafi LiveNo ratings yet

- Human rights and good governance: How they strengthen each otherDocument10 pagesHuman rights and good governance: How they strengthen each otherLydia NyamateNo ratings yet

- State Building in Situations of Fragility: Initial Findings - August 2008Document4 pagesState Building in Situations of Fragility: Initial Findings - August 2008Maria Emilia LlerasNo ratings yet

- Unpacking States in The Developing WorldDocument10 pagesUnpacking States in The Developing WorldDanNo ratings yet

- Intro To Politics and AdministrationDocument11 pagesIntro To Politics and Administration21-50808No ratings yet

- Graham, Principles For Good GovernanceDocument8 pagesGraham, Principles For Good Governanceclemente2k100% (1)

- Tussie - Global GovernanceDocument37 pagesTussie - Global GovernanceMeli DeciancioNo ratings yet

- Globalization - Concept PaperDocument6 pagesGlobalization - Concept PaperBeatrice EdictoNo ratings yet

- Governance 2Document9 pagesGovernance 2Dena Flandez100% (1)

- By Thomas G. Weiss and Ramesh Thakur: The Challenges of GovernanceDocument23 pagesBy Thomas G. Weiss and Ramesh Thakur: The Challenges of Governancerhiantics_kram11No ratings yet

- Social Capital and Development: The Coming Agenda: Francis FukuyamaDocument15 pagesSocial Capital and Development: The Coming Agenda: Francis FukuyamaSarah G.No ratings yet

- Briefing Paper Briefing Paper: State-Building For Peace': Navigating An Arena of ContradictionsDocument4 pagesBriefing Paper Briefing Paper: State-Building For Peace': Navigating An Arena of ContradictionsFrancisco cossaNo ratings yet

- Democratisation With Inclusion Political ReformsDocument58 pagesDemocratisation With Inclusion Political ReformsMarium ShaikhNo ratings yet

- Limited Access Orders in The Developing World - WBDocument50 pagesLimited Access Orders in The Developing World - WBKD BankaNo ratings yet

- Mendoza, Nelryan - Bpaoumn 1-2 - Chapter 2 To 14Document36 pagesMendoza, Nelryan - Bpaoumn 1-2 - Chapter 2 To 14NelRyan MendozaNo ratings yet

- Lec 2Document9 pagesLec 2Umme Mahima MaisaNo ratings yet

- Graham - Peru@yahoo - Co.uk: Human Flourishing Project Briefing Paper 4Document32 pagesGraham - Peru@yahoo - Co.uk: Human Flourishing Project Briefing Paper 4Ankit GuptaNo ratings yet

- MODULE 3 PolGovDocument18 pagesMODULE 3 PolGovEugene TongolNo ratings yet

- Public Administration and DevelopmentDocument13 pagesPublic Administration and Developmentxdpera8No ratings yet

- Political Economy Theories of Policy DevelopmentDocument6 pagesPolitical Economy Theories of Policy DevelopmentGypcel Seguiente Arellano100% (1)

- Module 1 - The Concept of Governance PoliticsDocument52 pagesModule 1 - The Concept of Governance PoliticsAllana Grace Loraez InguitoNo ratings yet

- Power Politics and Governance: The Influence of Transnational CorporationsDocument13 pagesPower Politics and Governance: The Influence of Transnational CorporationsJacob MahlanguNo ratings yet

- Definition of GovernanceDocument10 pagesDefinition of Governancetufail100% (1)

- 02 Worksheet 3Document3 pages02 Worksheet 3Krystal Anne MansanidoNo ratings yet

- Lecture Definition Governance GovernmentDocument4 pagesLecture Definition Governance GovernmentTrojan VirusNo ratings yet

- Cpa KDocument19 pagesCpa KNikki PachikaNo ratings yet

- State CapacityDocument35 pagesState CapacityElisa LagesNo ratings yet

- Role of Governance and Public Administration in DevelopmentDocument2 pagesRole of Governance and Public Administration in DevelopmentBebargNo ratings yet

- State Role in Development: Rethinking Current LiteratureDocument93 pagesState Role in Development: Rethinking Current LiteratureJoanne FernandezNo ratings yet

- By William Easterly: Working Paper Number 94 August 2006Document34 pagesBy William Easterly: Working Paper Number 94 August 2006Mohan Kumar SinghNo ratings yet

- Participation and Development: Perspectives From The Comprehensive Development ParadigmDocument20 pagesParticipation and Development: Perspectives From The Comprehensive Development ParadigmEnrique SilvaNo ratings yet

- Governance Issues in a Globalized WorldDocument3 pagesGovernance Issues in a Globalized WorldJunu HadaNo ratings yet

- Round 2 1NCDocument25 pagesRound 2 1NCyesman234123No ratings yet

- Foundations and Development of Indian Fe PDFDocument11 pagesFoundations and Development of Indian Fe PDFShivaraj ItagiNo ratings yet

- Global Governance Reform for the 21st CenturyDocument14 pagesGlobal Governance Reform for the 21st CenturytompidukNo ratings yet

- UCSPDocument10 pagesUCSPJasmin UnabiaNo ratings yet

- PeaceDocument4 pagesPeaceBisma NNo ratings yet

- Special Articles The Governance AgendaDocument6 pagesSpecial Articles The Governance AgendaIshpreet SinghNo ratings yet

- MOIST Governance & Social Responsibility Module 01Document11 pagesMOIST Governance & Social Responsibility Module 01MARJUN ABOGNo ratings yet

- Lesson-Week-8-GaD (1)Document8 pagesLesson-Week-8-GaD (1)bpa.galsimaaNo ratings yet

- The Ethiopian Developmental State and ItDocument26 pagesThe Ethiopian Developmental State and ItFanose GudisaNo ratings yet

- GovernanceDocument27 pagesGovernancealexaaluan321No ratings yet

- Unit Iii: GovernanceDocument20 pagesUnit Iii: GovernanceTyron Rod VillegasNo ratings yet

- Translating Community Participation into Sustainable National DevelopmentDocument19 pagesTranslating Community Participation into Sustainable National Developmentklm klmNo ratings yet

- How Multinational Corporations Erode State SovereigntyDocument25 pagesHow Multinational Corporations Erode State SovereigntyWeldone Saw100% (1)

- Towards A Political Economy of "Post-Celtic Tiger" IrelandDocument22 pagesTowards A Political Economy of "Post-Celtic Tiger" Irelanddavid_conway_16No ratings yet

- What Does Good Governance MeanDocument4 pagesWhat Does Good Governance Meanranjann349No ratings yet

- Uses and Abuses of The Concept of GovernanceDocument9 pagesUses and Abuses of The Concept of GovernanceAlexandru AlexNo ratings yet

- Building Institutional Capacity For DevelopmentDocument3 pagesBuilding Institutional Capacity For DevelopmentADB Knowledge SolutionsNo ratings yet

- New Configurations of International OrderDocument10 pagesNew Configurations of International OrdermaressaomenaNo ratings yet

- Private Side Go Bal Gov Her TelDocument10 pagesPrivate Side Go Bal Gov Her TelJulia GodinhoNo ratings yet

- Chibber Bureaucratic RationalityDocument40 pagesChibber Bureaucratic RationalitydoctoradoenpoliticauntNo ratings yet

- Chapter 4Document6 pagesChapter 4Crystal Mae EgiptoNo ratings yet

- Getting Real about NGO Relationships in the Aid SystemDocument13 pagesGetting Real about NGO Relationships in the Aid SystemKimberly LagmanNo ratings yet

- Good Governance Key to DevelopmentDocument6 pagesGood Governance Key to DevelopmentJohar NawazNo ratings yet

- Hope and Insufficiency: Capacity Building in Ethnographic ComparisonFrom EverandHope and Insufficiency: Capacity Building in Ethnographic ComparisonRachel Douglas-JonesNo ratings yet

- LECTURE PPG Quarter-1Document23 pagesLECTURE PPG Quarter-1Chrystal Khey MendozaNo ratings yet

- People's Role in DevelopmentDocument8 pagesPeople's Role in DevelopmentrachitaNo ratings yet

- Who Rules the World? The Power of the Black NobilityDocument2 pagesWho Rules the World? The Power of the Black Nobilityuser1489881100% (1)

- Contingency Procedures For 2023 BSKEDocument8 pagesContingency Procedures For 2023 BSKELiniel FeliminianoNo ratings yet

- TCWD ReviewerDocument9 pagesTCWD Reviewerstarejl357No ratings yet

- Historical Background of The IALA Maritime Buoyage SystemDocument1 pageHistorical Background of The IALA Maritime Buoyage SystemShaun JohnsonNo ratings yet

- Philippines-China relations over the decadesDocument5 pagesPhilippines-China relations over the decadesHydrgn 1001No ratings yet

- Adjournment MotionDocument9 pagesAdjournment MotionSATYARTH PRAKASH IASNo ratings yet

- Aunt Jennifer's TigersDocument2 pagesAunt Jennifer's TigersAyush KNo ratings yet

- 2.A - Brandt Et Al. (2019)Document13 pages2.A - Brandt Et Al. (2019)Milena IvanovićNo ratings yet

- The Montague-Chelmsford Reforms (1919)Document9 pagesThe Montague-Chelmsford Reforms (1919)Sayed Zameer ShahNo ratings yet

- Reagan's 1985 Radio Address on Upcoming Geneva SummitDocument4 pagesReagan's 1985 Radio Address on Upcoming Geneva SummitMarina DiaconescuNo ratings yet

- Church of AbadarDocument4 pagesChurch of AbadarCourtneyNo ratings yet

- Contemporary Challenges To RegionalismDocument2 pagesContemporary Challenges To RegionalismHannah Reyna Herda Pancho33% (3)

- Pakistan Affairs Syllabus For CSS 2023Document8 pagesPakistan Affairs Syllabus For CSS 2023Abdul WahidNo ratings yet

- Keputusan Matematik Gerak Gempur 2019Document2 pagesKeputusan Matematik Gerak Gempur 2019farhan imranNo ratings yet

- Electoral Politics Class 9 Important Questions Very Short Answer Type Questions.Document9 pagesElectoral Politics Class 9 Important Questions Very Short Answer Type Questions.Shamim BanuNo ratings yet

- The History of UaeDocument10 pagesThe History of UaeAnselkThomasNo ratings yet

- Rizal Life and WorksDocument8 pagesRizal Life and WorksIan AlvarezNo ratings yet

- Postcolonial and Postsocialist Dialogues Intersections Opacities Challenges in Feminist Theorizing and PracticeDocument283 pagesPostcolonial and Postsocialist Dialogues Intersections Opacities Challenges in Feminist Theorizing and PracticeArunNo ratings yet

- Offer Letters 01022018Document14 pagesOffer Letters 01022018Hacker RoyNo ratings yet

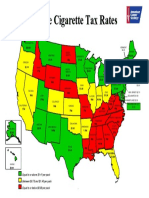

- Tax MapDocument1 pageTax MaprkarlinNo ratings yet

- Detailed Lesson Plan FinalDocument9 pagesDetailed Lesson Plan FinalDianne Seno BasergoNo ratings yet

- Role of CSOs in Public Policy and Service DeliveryDocument23 pagesRole of CSOs in Public Policy and Service DeliveryfrustratedlawstudentNo ratings yet

- Week 2 Major Political Ideologies and Their Key TenetsDocument25 pagesWeek 2 Major Political Ideologies and Their Key TenetsFredo EstoresNo ratings yet

- En 1371-2-1998Document14 pagesEn 1371-2-1998Pippo LandiNo ratings yet

- 1000 RecipientsDocument121 pages1000 Recipients4zqz75b2znNo ratings yet

- International Women's Day Report Highlights Ongoing Need for Gender EqualityDocument12 pagesInternational Women's Day Report Highlights Ongoing Need for Gender EqualityMahakNo ratings yet

- Cambridge International AS & A Level: HISTORY 9489/22Document4 pagesCambridge International AS & A Level: HISTORY 9489/22Zsara ManuelNo ratings yet

- Critical Issues in Black Women NotesDocument7 pagesCritical Issues in Black Women Notesmyles reeseNo ratings yet

- Samuel C. Occeña: Commission On Elections, Commission On Audit, National Treasurer, and Director of PrintingDocument3 pagesSamuel C. Occeña: Commission On Elections, Commission On Audit, National Treasurer, and Director of PrintingmeerahNo ratings yet

- HQ Cug 020922Document20 pagesHQ Cug 020922siddharthNo ratings yet