Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Stroke Training in Tweeter

Uploaded by

Shirsho ShreyanOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Stroke Training in Tweeter

Uploaded by

Shirsho ShreyanCopyright:

Available Formats

RESEARCH ARTICLE OPEN ACCESS

Curriculum Innovations: A Social Media–Based

Educational Curriculum Improves Knowledge for

Trainees in Neurocritical Care

Results of a Stratified Randomized Study

Ronald Alvarado-Dyer, MD, Faddi G. Saleh Velez, MD, Hera A. Kamdar, MD, Naomi Niznick, MD, Correspondence

Elizabeth Carroll, MD, Carlos Castillo-Pinto, MD, Melvin Parasram, DO, Dearbhla Kelly, MD, Dr. Alvarado-Dyer

Shweta Goswami, MD, Mikel S. Ehntholt, MD, Neha S. Dangayach, MD, MSCR, Marc-Alain Babi, MD, Ronald.Alvarado-Dyer@

Ahmad Riad Ramadan, MD, Christos Lazaridis, MD, Catherine Albin, MD, and Nicholas A. Morris, MD ouhealh.com

®

Neurology Education 2023;2:e200087. doi:10.1212/NE9.0000000000200087

Abstract

Introduction and Problem Statement

The Neurocritical Care (NCC) Society Resident and Fellow Task Force’s NEURON study

concluded that learners had significant concerns regarding the need for educational improve-

ment in NCC. To address these shortcomings, we identified the lack of an educational cur-

riculum for trainees in NCC and developed a Twitter-based educational curriculum for trainees

to improve knowledge in NCC.

Objectives

The objectives of this study were to describe the pathophysiology, delineate a systematic

diagnostic approach, and apply evidence-based strategies in the management of diseases in

NCC.

Methods and Curriculum Description

Ten trainees developed a Tweetorial (educational content available on Twitter)–based cur-

riculum, with individual review by at least 2 NCC faculty. Learners were recruited through

Twitter and randomized to 1 of 2 groups in a wait-list control prospective study. Group 1

completed the curriculum in the first 6 months of the 2021–2022 academic year, and group 2

completed the curriculum in the second half. Tweetorials were posted weekly on a private

Twitter account only available to the active learner group. Learners were assessed by a multiple-

choice format test (written by the trainees and reviewed by faculty) at 3 time points: before the

first Tweetorial was released (preeducational curriculum assessment), after group 1 completed

all tutorials and before group 2 started the curriculum (assessment 1), and after both groups

finished (assessment 2). The primary outcome was the mean score on the second and third

assessments.

Results and Assessment Data

One hundred forty-six learners were assigned to group 1 or 2 using stratified block randomi-

zation including 99 (68%) Neurology residents, 81 (55%) US-based. Each group was com-

posed of 73 participants. A total of 20 Tweetorials were published on a private Twitter account

(@NeurocriticalE). Completed assessments were obtained from 100, 32, and 18 learners for

From the Department of Neurology (R.A.-D., C.L.), University of Chicago Medical Center, University of Chicago, IL; Department of Neurology (F.G.S.V.), The University of Oklahoma

Health Sciences Center, Oklahoma City; Department of Neurology (H.A.K.), Massachusetts General Hospital and Brigham and Women Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston;

Department of Medicine (Neurology; Critical Care) (N.N.), The Ottawa Hospital, Ontario, Canada; Department of Neurology (E.C.), Columbia University Medical Center; Department

of Neurology (E.C.), Cornell University School of Medicine, New York, NY; Department of Neurology (C.C.-P.), Seattle Children’s Hospital, University of Washington, Seattle; De-

partment of Neurology (M.P.), Yale School of Medicine, New Haven, CT; Department of Intensive Care Medicine (D.K.), St. James’s Hospital, Dublin, and Global Brain Health Institute,

Trinity College Dublin, Ireland; Department of Neurology (S.G.), University of Florida, Gainesville; Department of Neurology (M.S.E.), University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA;

Department of Neurology (N.S.D.), Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, NY; Department of Neurology and Neurosurgery (M.-A.B.), Neurological Institute, Cleveland

Clinic Foundation (Florida), Port St. Lucie; Department of Neurology (A.R.R.), Henry Ford Health, Detroit, MI; Department of Neurology and Neurosurgery (C.A.), Emory University

School of Medicine, Atlanta, GA; and Department of Neurology (N.A.M.), Program in Trauma, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore.

Go to Neurology.org/NE for full disclosures. Funding information and disclosures deemed relevant by the authors, if any, are provided at the end of the article.

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0 (CC BY), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any

medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Copyright © 2023 American Academy of Neurology 1

Glossary

APP = advanced practice provider; NCC = neurocritical care; NCCU = NCC unit; NICU = neurologic intensive care unit;

REDCap = Research Electronic Data Capture.

the pre-educational curriculum assessment, assessment 1, and assessment 2, respectively. Group 1 and group 2 performed

similarly in the pre-educational curriculum assessment. A potential for knowledge improvement was observed in group 1 at

assessments 1 and 2 when compared with the learner group 2. Group 1 had more impressions, engagements, likes, URL clicks,

and media views.

Discussion and Lessons Learned

Although there was some learner attrition, our study demonstrates that social media can effectively deliver educational content

and engage a diverse group of trainees around the globe.

thousands of Twitter users. The coronavirus disease 2019

Introduction and Problem Statement pandemic accelerated the adoption of social media platforms

Physician trainees and advanced practice providers (APPs) such as Twitter, leveraging its independent, asynchronous,

often provide frontline care to critically ill neurologic and interactive, and democratic features that flatten traditional

neurosurgical patients in the neurologic intensive care unit educational hierarchies.5

(NICU). Despite the establishment of neurocritical care

(NCC) units (NCCUs) in academic centers across the Despite its growing popularity, a gap exists in showing

United States, a 2012 survey of neurology residency directors evidence-based support for the educational efficacy of this

revealed that only 56% of neurology residency programs have newly embraced platform, particularly within NCC. In this

a dedicated NCCU rotation, and even across these programs, study, we aimed to develop a social media–based NCC edu-

formal training in NCC is highly variable.1,2 When the Neu- cational curriculum for trainees and APPs with the goal of

rocritical Care Society Resident and Fellow Task Force’s improving knowledge in NCC disorders and assess the

NEURON study surveyed neurology residents across the feasibility and efficacy of a Tweetorial-based educational

United States and 1 international NCC training program, they curriculum.

found that residents had significant concerns regarding the

need for educational improvement within the NCCU.3 Given

the demanding nature of the field, complex patient care, Curriculum Objectives

and varying call schedules, there is also limited time for 1. To describe the pathophysiology of diverse condi-

and engagement with formal NCC didactics. We posited tions in NCC (Table 1).

that an on-demand, asynchronous learning solution 2. To delineate a systematic approach in the diagnosis

was needed to address educational gaps broadly across of NCC disorders through case-based learning.

NCCUs. Thus, we developed a novel Twitter-based edu- 3. To apply evidence-based strategies in the manage-

cational curriculum for trainees and APPs to improve their ment of diseases in NCC.

knowledge in NCC.

We developed and delivered a Twitter-based NCC educa-

Social media has emerged as a relevant and growing tool for tional curriculum to all the registered participants.

medical education. Twitter offers a rich interactive platform

for disseminating educational content through Tweetorials,

which are collections of threaded or consecutive tweets aimed

at teaching users who engage with them.4 Furthermore, via

Methods and Curriculum Description

Twitter analytics, Twitter also offers the possibility of gauging Curriculum Design

the interaction across followers with every individual tweet, We developed a wait-list control educational curriculum

which provides valuable insight regarding the interaction be- among the recruited participants. The educational curriculum

tween users and the educational content delivered via was staggered. The participants randomized to group 1 had

Tweetorials. Tweetorials offer several features that are well the curriculum made available to them in the first half of the

adapted to adult learners including asynchronous learning and 2021–2022 academic year. The participants randomized to

distilled points and require only a short investment of time to group 2 had the curriculum made available to them in the

read for independent learning. As such, these microteaching second half of the academic year. The educational curriculum

posts are perfectly adapted “chalk talks” that can reach was designed to be delivered over 5–6 months.

2 Neurology: Education | Volume 2, Number 3 | September 2023 Neurology.org/NE

Table 1 Educational Curriculum Topics

Topics Subtopics

Increased intracranial pressure Basics, monitoring and overview of management.

Ischemic stroke Anterior circulation ischemic stroke

Posterior circulation ischemic stroke

Intracerebral hemorrhage Supratentorial hemorrhage

Infratentorial hemorrhage

Subarachnoid hemorrhage Aneurysmal high-grade subarachnoid hemorrhage

Traumatic brain injury Blunt traumatic brain injury

Penetrating brain injury

Spinal cord injury Cervical spine injury

Status epilepticus Definition, pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment

Neuromuscular diseases Guillain-Barré syndrome and myasthenia gravis

Encephalitis/meningitis Etiology, diagnosis, and management

Toxic/metabolic syndromes Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome, serotonin syndrome, and neuroleptic malignant

syndrome.

Brain death Definition and algorithm

Ventilator management in the NCCU Basic concepts and applications in mechanical ventilation in the NICU

Basic NCCU pharmacology Anticoagulant and antiplatelet reversal, antihypertensive medications

Critical care nephrology in NCCU Diabetes insipidus

Syndrome of inadequate antidiuretic hormone secretion

Dialysis disequilibrium syndrome

Pediatric NCCU for neurology and non-neurology Pediatric stroke and pediatric traumatic brain injury

residents

Abbreviations: NCCU = neurocritical care unit; NICU = neurologic intensive care unit.

Participant’s Recruitment NCC management, several links to scientific references for

The study was advertised through the author’s Twitter ac- further review, key points of the pathology and management,

counts during the enrollment period. Trainees and APPs in- and at least 1 poll.

terested in participating in the educational curriculum

completed an initial survey (distributed through Research Educational Curriculum Outline/Syllabus

Electronic Data Capture [REDCap]), which contained basic The curriculum was based on the published core curriculum

demographic information, current level of training, location of and competencies for advanced training in neurologic in-

training, interest in NCC, prior rotation in an NCCU, if so, tensive care (Table 1).6

the duration of the rotation, and whether they would like to

participate in the educational curriculum. Curriculum Learning Outcomes: Assessments

In addition to authoring tweetorials, the participating fellows

Curriculum Content: Tweetorials also collaborated in authoring a knowledge assessment test

Ten trainees (8 NCC fellows, 1 vascular neurology fellow, and with a total of 65 multiple-choice questions on the covered

1 pediatric neurology fellow) developed the curriculum. Each topics. Each question was approved and verified by 6 board-

trainee wrote at least 1 case-based Tweetorial on an assigned certified neurointensivists prior to being included (same 6

topic that was reviewed by at least 2 of 6 NCC faculty from neurointensivists who reviewed the Tweetorials). Two of the

different academic institutions across the United States. neurointensivists (N.A.M. and C.L.) were directly assigned by

Tweetorials were posted on a private Twitter account the main investigator (R.A.-D.). The other 4 (N.S.D., M.-A.B.,

(@NeurocriticalE) on a weekly basis throughout the duration A.R.R., C.A.) were recruited through Twitter. A total of 5

of the curriculum for each learner group. Each Tweetorial questions were discarded. Any question-related discrepancy

consisted of the following: a brief case presentation, initial was resolved by N.A.M. In the process of creating the

Neurology.org/NE Neurology: Education | Volume 2, Number 3 | September 2023 3

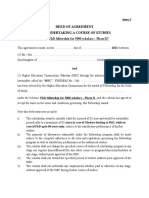

Figure 1 Educational Curriculum’s Flowchart

assessments, we randomly sorted the questions into three 20- Statistical Analysis

question assessments. All the tests were delivered via RED- We reported participant’s tests scores and Twitter metrics

Cap to each participant. (impressions, engagements, likes, and social media views)

using standard descriptive statistics (e.g., mean and SD for

Before the initiation of the educational curriculum, all continuous normally distributed data and median and inter-

participants were expected to complete a 20-question pre- quartile range for non-normally distributed data). We com-

educational curriculum assessment to gauge baseline knowl- pared participants’ tests scores, as well as group 1 and 2

edge. Assessment 1 was expected to be completed by all Twitter metrics using student unpaired t test. Differences

participants after group 1 had finished the curriculum (but were considered significant with a p value <0.05. All analyses

before group 2 has started the curriculum), and assessment 2 were performed using Stata/MP (version 15.0; StataCorp.,

was expected to be completed by all participants after both College Station, TX) and photon 3 software. Only complete

learner groups completed the curriculum. The primary cases were analyzed at each time point. There was no

learning outcome of our curriculum was the mean score on intention-to-treat analysis, and there was no data imputation.

the second and third assessments. The wait-list design con-

trolled for the expected learning or maturation effect that Standard Protocol Approvals, Registrations,

takes place during a training program. and Patient Consents

The study was reviewed and approved by The University of

Twitter Metrics Chicago Institutional Review Board. A waiver of signed in-

The Twitter analytics website7 was used to gather Twitter formed consent was granted. Through an initial REDCap

metrics after each learner group finished the educational survey, all the participants were provided an opportunity to

curriculum. We collected the number of impressions, en- agree or decline to participate in the educational curriculum.

gagements, likes, URL clicks, and media views of all 20

Data Availability

published Tweetorials per learner group. Impressions were

Data will be made available through request directed to the

defined as the number of times users saw a Tweet on

corresponding author.

Twitter. Engagements were the number of times a user

interacted with a Tweet (clicked anywhere on the Tweet).

Likes indicated the number of times a user liked a Tweet.

URL clicks referred to the number of times a user clicked

Results

on a website link within a Tweet. Media views denoted the Participants

number of times a user interacted with images and videos in A total of 146 learners participated (Figure 1). This included

a Tweet. 99 (68%) neurology trainees and 45 (31%) trainees from

4 Neurology: Education | Volume 2, Number 3 | September 2023 Neurology.org/NE

other specialties such as anesthesia, child neurology, internal

medicine, neurosurgery, emergency medicine, and pediat- Table 3 Twitter Metricsa

rics. Two participants (1%) were APPs. Of them, 81 (55%) Group 1 Group 2

were US-based, while 65 (45%) were non-US-based. One

Impressions 1,577 (1,210–2,483) 959 (621–1,168)

hundred (69%) had a dedicated NCCU at their institution.

Ninety-two (63%) were considering pursuing an NCC fel- Engagements 182 (148–276) 81 (59–105)

lowship. When comparing both groups, there was no sta-

Likes 17 (13–28) 5 (3–6)

tistically significant difference regarding the learners’ mean

age, sex (self-identified in the first REDCap survey), interest URL clicks 8 (4–16) 2 (0–6)

in pursuing an NCC fellowship, and participants who had an Media views 151 (130–213) 7 (40–86)

NCCU at their institution. Group 1 was composed of 57

a

(78%) neurology trainees, while group 2 had 42 (58%) All data presented as median (interquartile range). Data represent the

median of all Tweetorials for each group.

neurology trainees. Similarly, group 1 had more US-based

trainees when compared with group 2 (47 [64%] vs 34

[47%]) (Table 2).

the divergence in test scores between group 1 and group 2;

Assessments and (3) wait-list control studies delivered over social media

One hundred learners completed the pre-educational curric- risk losing social media–based learners to follow-up.

ulum assessment. Thirty-two learners completed assessment

1, and 18 learners completed assessment 2. Both learner Free, global, and easily accessible, Twitter has the ability to engage

groups performed similarly in the pre-educational curriculum trainees and other healthcare providers from around the world and

assessment. A potential for knowledge improvement was serve as a platform to provide medical education through many

observed in group 1 at assessments 1 and 2 when compared formats including journal clubs, conferences, and webinars.5,8,9 Our

with that in learner group 2. study was able to recruit learners from more than 22 countries

(eTables 1 and 2, links.lww.com/NE9/A39) and from several

Twitter Metrics medical specialties as well. This diverse group of learners partici-

Learner group 1 had overall more impressions, engagements, pated in an innovative Tweetorial-based educational curriculum.

likes, URL clicks, and media views than group 2 (Table 3). As

summarized in eTable 3 (links.lww.com/NE9/A39) and pre- Tweetorial-based educational efforts lack data supporting their

sented in Figure 2, group 1 had consistently higher engage- efficacy. The divergence in tests scores between our 2 groups from

ments throughout the curriculum. the preassessment to assessment 1 suggests knowledge improve-

ments are possible, although our results should be interpreted

cautiously in light of poor participant retention. A recent study of

Discussion and Lessons Learned Tweetorials from the CardioNerds Academy analyzed 7 cardiol-

In this novel Tweetorial-based educational curriculum, we ogy Tweetorials from 4 unique authors that found that the mean

found out the following: (1) our Tweetorial-based education proportion of respondents felt comfortable with a given topic

was able to reach learners with different backgrounds around increased from 24.7% to 72.9% after completing a Tweetorial.10

the globe but lacked sustained curricular engagement; (2) the Our study builds on this work by suggesting that knowledge may

preliminary evaluation of our educational curriculum suggests actually increase, a higher-order learning outcome.11

potential for improving knowledge in NCC as evidenced by

While both groups performed similarly on the baseline as-

sessment, group 1 scored better on the second and third

assessments, showing minimal knowledge decay. By contrast,

Table 2 Participant Characteristicsa group 2 did not seem to benefit from the curriculum, possibly

Group 1 Group 2 due to poor engagement, evidenced by their Twitter metrics.

(n = 73) (n = 73) A plausible explanation for a lower engagement rate in the

Age, mean (SD) 31 (6.0) 31 (5.1) second learner group is the methodology of wait-list–

controlled studies that may lead to more attrition as other

Woman 34 (47) 25 (34)

content vies for learner attention. Malcom Knowles’ adult

US-based 47 (64) 34 (47) learning theory suggests that adults are most interested in

Neurology trained 57 (78) 42 (58) learning that has immediate relevance and impact.12 The slow

incremental deployment of our curriculum may have delayed

Dedicated NCCU 54 (74) 46 (63)

its delivery to the point that group 2 learners had moved

Interested in pursuing NCC fellowship 48 (66) 44 (60) beyond the initial engagement on social media that inspired

their participation. We had segmented the curriculum in this

Abbreviations: NCC = neurocritical care; NCCU = NCC unit.

a

All data presented as n (%) unless otherwise specified.

way to align with Mayer’s principles of multimedia learning.

According to Mayer,13 learners have limited capacity to their

Neurology.org/NE Neurology: Education | Volume 2, Number 3 | September 2023 5

Figure 2 Engagements per Tweetorial

processing powers and learn better when messages are pre- longitudinal curriculum and how to assess outcomes. Our

sented in user-paced segments rather than as a continuous Tweetorial-based educational curriculum embraces the

unit. While this may be true, the peripatetic nature of resi- andragogy theory of adult education, which is based on self-

dency training may demand that the subspecialized curricu- directed, self-efficacious, problem-centered, independent

lum is delivered during the relevant clinical rotations lest all and constructive methods.16 In addition, these micro-

but the most intrinsically motivated learners be lost. Future teaching threads are innovations in medical education be-

studies of subspecialty education may need to account for this. cause they are a novel teaching method that involve creation,

integration, and application and thus merit inclusion within

An alternative explanation would be that group 1 was in- the Educational Scholarship through social media as defined

herently more motivated than group 2 and that this motiva- by Holmboe et al.17

tion could have led to group 1 learning more about NCC

independent of our curriculum. The imbalance in trainee Because our Twitter profile (@NeurocriticalE) and curricu-

background is another possible explanation for the difference lum was made available publicly in July 2022, it has garnered

in performance between both learner groups because group 1 1,395 followers, highlighting its expansive reach.

had more Neurology trainees compared with group 2, and the

maturation effect is expected to be greater in Neurology trainees. Our study has several limitations. There were more neurology

Another possible explanation for the difference in performance trainees in group 1 than in group 2 despite randomization,

between both learner groups is the presence of differential although this difference was not statistically significant. There

dropout, particularly given the considerable decrement in the was a dramatic reduction in the number of participants who

number of participants completing all the assessments. Last, completed each assessment; however, the reductions were

while NCC training is quite diverse throughout the world, we similar in each group. In addition, we were not able to assess

have no objective evidence to believe the country of origin or Twitter metrics at an individual participant level, which would

location of training played a substantial role in the score variation have allowed us to determine whether increased engagement

or engagement between both learner groups. with the curriculum led to more knowledge transfer. We also

lacked qualitative feedback from the participants. Regarding

Twitter has emerged as an innovative platform that can ef- our assessments, our multiple-choice–based assessments

fectively deliver educational content and engage diverse lacked measures of validity outside of internal content validity.

groups of healthcare professionals around the world. Our We also lacked international diversity in the participating

novel educational curriculum was able to reach learners from NCC faculty. Finally, our findings may have been biased to-

across 23 countries. On average, the learners accessed our ward more engagement with the platform because we

educational material multiple times as measured by the recruited our learners on Twitter and they volunteered to take

number of engagements obtained via Twitter metrics. We part. We do not know whether learners who do not already

followed expert advice in developing our Tweetorials, yet actively use Twitter would have interacted with our curricu-

best practices for Tweetorials remain to be elucidated.14,15 lum as favorably if assigned to it as part of a training program.

Future research should focus on answering important

questions to help optimize Tweetorial-based education, A Twitter-based educational curriculum disseminates teach-

including how to maintain learner engagement through a ing and improves knowledge in engaged learners. It is a low-

6 Neurology: Education | Volume 2, Number 3 | September 2023 Neurology.org/NE

resourced curriculum that worldwide neurosciences educa-

tors can design and adapt for their own learning needs and Appendix (continued)

context. Furthermore, given the educational modality, Name Location Contribution

worldwide collaborations and partnerships are possible in

curriculum design, delivery, and evaluation. Twitter may be Dearbhla Department of Intensive Drafting/revision of the

Kelly, MD Care Medicine, St James’s article for content, including

a valuable adjunct tool for learning and teaching in acade- Hospital, Dublin, and Global medical writing for content

mia. Further research is necessary to discover best research Brain Health Institute, Trinity

College Dublin, Ireland

designs for evaluating this platform. Best practices for

consistent, longitudinal learner engagement also remain to Shweta Department of Neurology, Drafting/revision of the

Goswami, University of Florida, article for content, including

be defined. MD Gainesville medical writing for content

Mikel S. Department of Neurology, Drafting/revision of the

Study Funding Ehntholt, University of Pennsylvania, article for content, including

No targeted funding reported. MD Philadelphia medical writing for content

Neha S. Department of Neurology, Drafting/revision of the

Disclosure Dangayach, Icahn School of Medicine at article for content, including

The authors report no disclosures relevant to the manuscript. MD, MSCR Mount Sinai, New York, NY medical writing for content

Go to Neurology.org/NE for full disclosures. Marc-Alain Department of Neurology Drafting/revision of the

Babi, MD and Neurosurgery, article for content, including

Neurological Institute, medical writing for content

Publication History Cleveland Clinic Foundation

Received by Neurology: Education November 20, 2022. Accepted in final (Florida), Port St. Lucie

form June 5, 2023. Submitted and externally peer reviewed. The Ahmad Riad Department of Neurology, Drafting/revision of the

handling editor was Editor Roy Strowd III, MD, MEd, MS. Ramadan, Henry Ford Health, Detroit, article for content, including

MD MI medical writing for content

Christos Department of Neurology, Drafting/revision of the

Lazaridis, University of Chicago Medical article for content, including

MD Center, University of Chicago, medical writing for content;

IL study concept or design

Appendix Authors

Catherine Department of Neurology Drafting/revision of the

Name Location Contribution

Albin, MD and Neurosurgery, Emory article for content, including

University School of medical writing for content;

Ronald Department of Neurology, Drafting/revision of the

Medicine, Atlanta, GA study concept or design

Alvarado- University of Chicago Medical article for content, including

Dyer, MD Center, University of Chicago, medical writing for content;

Nicholas A. Department of Neurology, Drafting/revision of the

IL; Current affiliation: major role in the acquisition

Morris, MD Program in Trauma, article for content, including

Department of Neurology, of data; study concept or

University of Maryland medical writing for content;

OU Health University of design; and analysis or

School of Medicine, study concept or design; and

Oklahoma Medical Center, interpretation of data

Baltimore analysis or interpretation of

Oklahoma City

data

Faddi G. Department of Neurology, Drafting/revision of the article

Saleh Velez, The University of Oklahoma for content, including medical

MD Health Sciences Center, writing for content; study

Oklahoma City concept or design; and analysis References

or interpretation of data 1. Sheth KN, Drogan O, Manno E, Geocadin RG, Ziai W. Neurocritical care education

during neurology residency AAN survey of US program directors. Neurology. 2012;

Hera A. Department of Neurology, Drafting/revision of the 78(22):1793-1796. doi:10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182583034

Kamdar, Massachusetts General article for content, including 2. Builes-Aguilar A, Diaz-Gomez JL, Bilotta F. Education in neuroanesthesia and neu-

MD Hospital and Brigham and medical writing for content rocritical care: trends, challenges and advancements. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2018;

Women Hospital, Harvard 31(5):520-525. doi:10.1097/ACO.0000000000000628

Medical School, Boston 3. Lerner DP, Kim J, Izzy S. Neurocritical care education during residency: opinions

(NEURON) study. Neurocrit Care. 2017;26(1):115-118. doi:10.1007/s12028-016-

Naomi Department of Medicine Drafting/revision of the 0315-1

Niznick, MD (Neurology; Critical Care), article for content, including 4. Breu AC. Why is a cow? Curiosity, tweetorials, and the return to why. N Engl J Med.

The Ottawa Hospital, medical writing for content 2019;381(12):1097-1098. doi:10.1056/nejmp1906790

Ontario, Canada 5. Thamman R, Gulati M, Narang A, Utengen A, Mamas MA, Bhatt DL. Twitter-based

learning for continuing medical education? Eur Heart J. 2020;41(46):4376-4379. doi:

Elizabeth Department of Neurology, Drafting/revision of the 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa346

Carroll, MD Columbia University Medical article for content, including 6. Mayer SA, Coplin WM, Chang C, et al. Core curriculum and competencies for

Center; Department of medical writing for content advanced training in neurological intensive care: United Council for Neurologic

Neurology, Cornell University Subspecialties Guidelines. Neurocrit Care. 2006;5(2):159-165. doi:10.1385/NCC:5:

School of Medicine, New 2:159

York, NY 7. Twitter Analytics. Accessed September 2022. analytics.twitter.com.

8. Merchant RM, Lurie N. Social media and emergency preparedness in response to

Carlos Department of Neurology, Drafting/revision of the novel coronavirus. JAMA. 2020;323(20):2011-2012. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.4469

Castillo- Seattle Children’s Hospital, article for content, including 9. Sarwal A, Desai M, Juneja P, Evans JK, Kumar A, Wijdicks E. Twitter journal club

Pinto, MD University of Washington, medical writing for content impact on engagement metrics of the Neurocritical Care journal. Neurocrit Care.

Seattle 2022;37(1):129-139. doi:10.1007/s12028-022-01458-7

10. Das TM, Helms L, Rai D, et al. Tweetorials as a teaching tool for cardiology medical

Melvin Department of Neurology, Drafting/revision of the education. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2022;79(9):1856. doi:10.1016/s0735-1097(22)02847-9

Parasram, Yale School of Medicine, New article for content, including 11. Kirkpatrick DL, Kirkpatrick J. Evaluating Training Programs. 3rd ed. Berret-Koehler

DO Haven, CT medical writing for content Publishers Inc.; 2006.

12. Knowles M. The Adult Learner: A Neglected Species. 3rd ed. Gulf Publishing; 1984.

Neurology.org/NE Neurology: Education | Volume 2, Number 3 | September 2023 7

13. Mayer RE. Multimedia Learning. 2nd ed. Cambridge University Press; 2009. 16. Pasquale SJ. Education and learning theory. In: Levine AI, DeMaria S, Schwartz AD,

14. Albin C, Berkowitz A. #NeuroTwitter 101: a tweetorial on creating tweetorials. Pr Sim AJ, eds. The Comprehensive Textbook of Healthcare Simulation. Springer; 2013:

neurol. 2021;21(6):539-540. doi:10.1136/practneurol-2021-003116 51-55. doi:10.1007/978-1-4614-5993-4_3

15. Breu AC. From tweetstorm to tweetorials: threaded tweets as a tool for medical 17. Sherbino J, Arora VM, Van Melle E, Rogers R, Frank JR, Holmboe ES. Criteria for

education and knowledge dissemination. Semin Nephrol. 2020;40(3):273-278. doi:10. social media-based scholarship in health professions education. Postgrad Med J. 2015;

1016/j.semnephrol.2020.04.005 91(1080):551-555. doi:10.1136/postgradmedj-2015-133300

8 Neurology: Education | Volume 2, Number 3 | September 2023 Neurology.org/NE

You might also like

- Relationship Between Health Literacy Scores and Patient Use of the iPET for Patient EducationFrom EverandRelationship Between Health Literacy Scores and Patient Use of the iPET for Patient EducationNo ratings yet

- Mini Thesis Draft For DummiesDocument32 pagesMini Thesis Draft For DummiesDaniela BalarbarNo ratings yet

- Revised Chapter-1-3-GreatmatesDocument24 pagesRevised Chapter-1-3-GreatmatesJocelyn Sta AnaNo ratings yet

- Allied Health Students' Coping Strategies in Their Related Learning Experiences in Skills Laboratory During The Virtual Classroom SetupDocument7 pagesAllied Health Students' Coping Strategies in Their Related Learning Experiences in Skills Laboratory During The Virtual Classroom SetupPsychology and Education: A Multidisciplinary JournalNo ratings yet

- Articles 1Document6 pagesArticles 1Syedah RashidNo ratings yet

- Article - INFUSION - OF - AGE-FRIENDLY - PRINCIPLES - INTO - CURRICULADocument1 pageArticle - INFUSION - OF - AGE-FRIENDLY - PRINCIPLES - INTO - CURRICULAHarlene ArabiaNo ratings yet

- Osborne+et+al +the+health+education+impact+questionnaireDocument10 pagesOsborne+et+al +the+health+education+impact+questionnairesandrine.abellarNo ratings yet

- Health Case Studies 1512494009Document258 pagesHealth Case Studies 1512494009lisa weareNo ratings yet

- A Resource For Teaching Emergency Care Communication: Clinical and Communication SkillsDocument6 pagesA Resource For Teaching Emergency Care Communication: Clinical and Communication SkillsAsihworo AnggraeniNo ratings yet

- Course Outline NURS 4524 W 24Document19 pagesCourse Outline NURS 4524 W 24cydeykulgmzarinlhkNo ratings yet

- Multimedia in Education: What Do The Students Think?: SciencedirectDocument9 pagesMultimedia in Education: What Do The Students Think?: SciencedirectMuhammad RamadhanNo ratings yet

- GROUP 1 - Chapter 2 (Revised)Document9 pagesGROUP 1 - Chapter 2 (Revised)itsgumbololNo ratings yet

- Attitudes of US Medical Trainees Towards Neurology Education: "Neurophobia" - A Global IssueDocument7 pagesAttitudes of US Medical Trainees Towards Neurology Education: "Neurophobia" - A Global Issuealikhanomer5No ratings yet

- Entrevistas TCCDocument37 pagesEntrevistas TCCBelen StrangeNo ratings yet

- Research PaperDocument12 pagesResearch PaperCai GatmaitanNo ratings yet

- 10 1016@j Aogh 2017 09 005 PDFDocument6 pages10 1016@j Aogh 2017 09 005 PDFWaldi RahmanNo ratings yet

- E-Learning Experience For Medical EducationDocument4 pagesE-Learning Experience For Medical Educationangelo.dibernardo63No ratings yet

- Duarte 2022Document12 pagesDuarte 2022Juan Carlos FloresNo ratings yet

- 7 MoocDocument14 pages7 MoocAda NwamemeNo ratings yet

- Jurnal 2Document5 pagesJurnal 2Edwin Rochmad MendiotaNo ratings yet

- Individual Assignment Cover Page: Department of Information Science and TechnologyDocument7 pagesIndividual Assignment Cover Page: Department of Information Science and Technologyadriana khanNo ratings yet

- Mental Health Challenges of Students in the New Learning SystemDocument53 pagesMental Health Challenges of Students in the New Learning SystemFrancis Alyana MagtibayNo ratings yet

- Basic Life SupportDocument15 pagesBasic Life Supportmiss betawiNo ratings yet

- J Ijmedinf 2021 104514Document8 pagesJ Ijmedinf 2021 104514Shofiyah WatiNo ratings yet

- Freshmen BEEd Students' Online Learning PracticesDocument12 pagesFreshmen BEEd Students' Online Learning PracticesDiane May Tuquero TusiNo ratings yet

- Kern Chapter 1Document6 pagesKern Chapter 1Claudia HenaoNo ratings yet

- Neutrosophic Analysis of The Nursing Care Process in The Teaching of NursingDocument8 pagesNeutrosophic Analysis of The Nursing Care Process in The Teaching of NursingScience DirectNo ratings yet

- Discharge Communication Practices in Pediatric Emergency Care - A Systematic Review and Narrative SynthesisDocument28 pagesDischarge Communication Practices in Pediatric Emergency Care - A Systematic Review and Narrative Synthesisleivaherre10No ratings yet

- Developing A Multimedia Courseware Using Cognitive Load TheoryDocument10 pagesDeveloping A Multimedia Courseware Using Cognitive Load TheorySMNo ratings yet

- Running Head: Teaching Project Paper 1Document10 pagesRunning Head: Teaching Project Paper 1api-539369902No ratings yet

- Summary 1Document4 pagesSummary 1claireXOXO 2746No ratings yet

- Impact of Social Media On Nurses Service Delivery - EditedDocument14 pagesImpact of Social Media On Nurses Service Delivery - EditedMaina PeterNo ratings yet

- Yeppy Vanya Fio Ovylia - 22020122120025 - Nurse EducationDocument7 pagesYeppy Vanya Fio Ovylia - 22020122120025 - Nurse EducationYeppy VanyaNo ratings yet

- Principles of Risk CommunicationDocument9 pagesPrinciples of Risk CommunicationTagliya TagoNo ratings yet

- Use of Neutrosophy in The Evaluation of A Health Education Program For Undergraduate Medical StudentsDocument6 pagesUse of Neutrosophy in The Evaluation of A Health Education Program For Undergraduate Medical StudentsScience DirectNo ratings yet

- A Qualitative Inquiry Comparing Mindfulness-Based Art Therapy Versus Neutral Clay Tasks As A ProactiDocument10 pagesA Qualitative Inquiry Comparing Mindfulness-Based Art Therapy Versus Neutral Clay Tasks As A ProactiGiNo ratings yet

- Sgu CompendiumDocument44 pagesSgu Compendiumdudeman2332No ratings yet

- Child NeurologyDocument5 pagesChild NeurologymhabranNo ratings yet

- Outline of Research Article Presentation-Group 2 (EFN 4A.A)Document5 pagesOutline of Research Article Presentation-Group 2 (EFN 4A.A)Zen ZeinNo ratings yet

- 725 Research ProposalDocument13 pages725 Research Proposalapi-676510959No ratings yet

- Nursing Students' Use of Technology Enhanced Learning: A Longitudinal StudyDocument14 pagesNursing Students' Use of Technology Enhanced Learning: A Longitudinal StudyDeva GeofahniNo ratings yet

- Comparing Computer-Assisted Learning Activities For Learning Clinical Neuroscience: A Randomized Control TrialDocument12 pagesComparing Computer-Assisted Learning Activities For Learning Clinical Neuroscience: A Randomized Control Trialdavid chungNo ratings yet

- Nursing Informatics Course Module on Educational and Research ApplicationsDocument5 pagesNursing Informatics Course Module on Educational and Research ApplicationsANGELICA MACASONo ratings yet

- Research Chapter 1 5Document79 pagesResearch Chapter 1 5Nichole John Ernieta50% (2)

- Chapter 1Document11 pagesChapter 1Yuuki Chitose (tai-kun)No ratings yet

- Annales D 891 HÃ Tã Nen DissDocument85 pagesAnnales D 891 HÃ Tã Nen DissDen SinyoNo ratings yet

- A Study To Evaluate The Efficacy of Self Instructional Module (SIM) On Knowledge and Practice Regarding Newborn Care Among Staff Nurses Working in Selected Hospitals of Delhi NCRDocument6 pagesA Study To Evaluate The Efficacy of Self Instructional Module (SIM) On Knowledge and Practice Regarding Newborn Care Among Staff Nurses Working in Selected Hospitals of Delhi NCRInternational Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)No ratings yet

- Medethex Online: A Computer-Based Learning Program in Medical Ethics and Communication SkillsDocument12 pagesMedethex Online: A Computer-Based Learning Program in Medical Ethics and Communication SkillsdrsrikanthreddyNo ratings yet

- Effectiveness of Planned Teaching Program On Hepatitis Among Mothers of School Children, ChennaiDocument3 pagesEffectiveness of Planned Teaching Program On Hepatitis Among Mothers of School Children, ChennaiEditor IJTSRDNo ratings yet

- 881 3032 1 PB PDFDocument5 pages881 3032 1 PB PDFBayarbaatar BoldNo ratings yet

- MededPublish - 3034 PDFDocument12 pagesMededPublish - 3034 PDFNailis Sa'adahNo ratings yet

- Chapter 4 & 5 Template (Draft)Document77 pagesChapter 4 & 5 Template (Draft)Alecs TungolNo ratings yet

- AJHPE 2018 V10i2 1057Document1 pageAJHPE 2018 V10i2 1057Tam AwNo ratings yet

- Ijlsit 3 (1) 2018 55-59Document7 pagesIjlsit 3 (1) 2018 55-59Dr. Rajeev ManhasNo ratings yet

- Nursing Thesis Proposal on Human Papilloma Vaccine AwarenessDocument24 pagesNursing Thesis Proposal on Human Papilloma Vaccine AwarenessCharlie Cotoner Falguera100% (1)

- Jayson NovellesDocument38 pagesJayson Novellesaronara dalampasiganNo ratings yet

- The Impact of Peer Assisted Learning On Mentors' Academic Life and Communication Skill in Medical Faculty: A Systematic ReviewDocument10 pagesThe Impact of Peer Assisted Learning On Mentors' Academic Life and Communication Skill in Medical Faculty: A Systematic ReviewIJPHSNo ratings yet

- Annotated Bibliography Vivian Dinh Dixie State UniversityDocument7 pagesAnnotated Bibliography Vivian Dinh Dixie State Universityapi-314231356No ratings yet

- Integrated Medical Informatics With Small Group Teaching in Medical EducationDocument10 pagesIntegrated Medical Informatics With Small Group Teaching in Medical EducationHAKNo ratings yet

- Publishable 4psDocument16 pagesPublishable 4psDan Lhery Susano Gregorious0% (1)

- Metrology Lab Manual PDFDocument12 pagesMetrology Lab Manual PDFBollu Satyanarayana0% (1)

- Job Description Job Details: Psychology Lead Fro Early Intervention, Psychosis Clinical Academic GroupDocument7 pagesJob Description Job Details: Psychology Lead Fro Early Intervention, Psychosis Clinical Academic GroupRuth Ann HarpurNo ratings yet

- Klasifikasi Pasien 1Document7 pagesKlasifikasi Pasien 1syofwanNo ratings yet

- BiharDocument51 pagesBiharshammiaquarianNo ratings yet

- 150+ English Conversation TopicsDocument11 pages150+ English Conversation TopicsLaura Borzoi100% (1)

- CLAT 2020 ApplicationDocument4 pagesCLAT 2020 ApplicationMohammad taha amirNo ratings yet

- Childhood and Adolescence DisordersDocument28 pagesChildhood and Adolescence DisordersFfahima M Khann100% (1)

- Higher Education South Africa BrochureDocument8 pagesHigher Education South Africa BrochureP FNo ratings yet

- Deed of AgreementDocument11 pagesDeed of AgreementSulemanKhNo ratings yet

- Accomplishment BSP CamporalDocument2 pagesAccomplishment BSP CamporalNylreyram Sentillas Cabilan-MontoNo ratings yet

- Philosophical Perspectives On Music by Wayne D. BowmanDocument615 pagesPhilosophical Perspectives On Music by Wayne D. BowmanChristina Pallas Guízar100% (2)

- 4k PhilosophyDocument1 page4k Philosophyapi-662330315No ratings yet

- Careers in Hospitality Management: Generation Y's Experiences and PerceptionsDocument14 pagesCareers in Hospitality Management: Generation Y's Experiences and PerceptionsCindy SorianoNo ratings yet

- Lesson Plan - UNIT6 - ReadingDocument6 pagesLesson Plan - UNIT6 - Reading981120.nmtdNo ratings yet

- Title of Lesson Grade Level Lesson Sources/ References: Ccss - Math.Content.2.G.A.1Document4 pagesTitle of Lesson Grade Level Lesson Sources/ References: Ccss - Math.Content.2.G.A.1api-313993232No ratings yet

- Chapter 3Document4 pagesChapter 3crizz_teen24No ratings yet

- Ebook Life CaochDocument37 pagesEbook Life CaochArafath AkramNo ratings yet

- English Teaching in ColombiaDocument4 pagesEnglish Teaching in Colombiafernanda sotoNo ratings yet

- National Taiwan University Student Dormitory Management RegulationsDocument9 pagesNational Taiwan University Student Dormitory Management RegulationsGavriel ChristophanoNo ratings yet

- Essentials Cap 1 2 3Document55 pagesEssentials Cap 1 2 3Pepe GeoNo ratings yet

- Exercising Lesson PlanDocument5 pagesExercising Lesson Planapi-309701161100% (5)

- CV Jing Jiawen 1Document2 pagesCV Jing Jiawen 1api-437518283No ratings yet

- SitatapatraDocument3 pagesSitatapatranieotyagiNo ratings yet

- K To 12 Caregiving Learning ModulesDocument85 pagesK To 12 Caregiving Learning ModulesGretchen FavilaNo ratings yet

- McLean Hospital Annual Report 2011Document32 pagesMcLean Hospital Annual Report 2011mcleanhospitalNo ratings yet

- Online Assignment LekshmiDocument7 pagesOnline Assignment LekshmiPreethi VNo ratings yet

- Essay On Alcohol Abuse Among Teenagers PDFDocument4 pagesEssay On Alcohol Abuse Among Teenagers PDFDamien Ashwood100% (1)

- Concept MappingDocument8 pagesConcept MappingRashid LatiefNo ratings yet

- MNB1501 TL 102 1 2024Document9 pagesMNB1501 TL 102 1 2024karenwaldeck06No ratings yet