Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Roche, C. 2008. The Fertile Brain and Inventive Power of Man

Uploaded by

Mike WatsonOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Roche, C. 2008. The Fertile Brain and Inventive Power of Man

Uploaded by

Mike WatsonCopyright:

Available Formats

Africa

http://journals.cambridge.org/AFR

Additional services for Africa:

Email alerts: Click here

Subscriptions: Click here

Commercial reprints: Click here

Terms of use : Click here

‘The Fertile Brain and Inventive Power of Man’: Anthropogenic Factors in

the Cessation of Springbok Treks and the Disruption of the Karoo

Ecosystem, 1865–1908

Chris Roche

Africa / Volume 78 / Issue 02 / May 2008, pp 157 - 188

DOI: 10.3366/E0001972008000120, Published online: 03 March 2011

Link to this article: http://journals.cambridge.org/abstract_S0001972000087374

How to cite this article:

Chris Roche (2008). ‘The Fertile Brain and Inventive Power of Man’: Anthropogenic Factors in the Cessation of Springbok

Treks and the Disruption of the Karoo Ecosystem, 1865–1908. Africa, 78, pp 157-188 doi:10.3366/E0001972008000120

Request Permissions : Click here

Downloaded from http://journals.cambridge.org/AFR, IP address: 137.158.158.60 on 30 Aug 2013

Africa 78 (2), 2008 DOI: 10.3366/E0001972008000120

‘THE FERTILE BRAIN AND INVENTIVE POWER

OF MAN’: ANTHROPOGENIC FACTORS IN

THE CESSATION OF SPRINGBOK TREKS AND

THE DISRUPTION OF THE KAROO

ECOSYSTEM, 1865–1908

Chris Roche

In the 1700s and 1800s, the imaginations of Dutch and British settlers

at the southern tip of Africa in what was to become the Cape Colony

fell captive to reports of enormous roving herds of a small gazelle-

like antelope, the springbok Antidorcas marsupialis. Descriptions of

herds, estimated at hundreds of thousands or even millions of animals,

periodically sweeping across the then mostly unknown interior of the

sub-continent, laying waste vast swathes of grazing and pasture and

disrupting any attempt at profitable pastoralism, both concerned

and fascinated the colonists and were featured with some fanfare and

excitement in the local press. Known as the trekbokken or trekbokke

(migrating antelope), by the Dutch, these swarms of small antelope and

their apparently random comings and goings were wrapped in myth and

mystery. It was not known precisely where the large herds came from,

what drove their movements, where they disappeared to, and why and

when they would return. The vast flat interior beyond the Cape Fold

Mountain, a harsh and largely unsettled scrub-covered desert known as

the Karoo, was the area most associated with their incursions, however,

and all manner of theory and conjecture accompanied the veritable war

waged against them by the colonists.

Over the latter half of the nineteenth century, while outright hunting

and shooting was generally seen as the only means of staunching the

periodic onslaughts, media and municipality urged multiple methods of

protecting stock and grazing against the springbok treks if any progress

was to be made in taming and settling the interior. Indeed, after a

protracted and dramatic inundation of springbok in a concentrated area

of the north-eastern Karoo in 1896 and 1897, the treks suddenly ceased

and the principal mammal migration of the Karoo became extinct, so

removing an important impediment to settlement and agriculture.

The cessation of springbok treks coincided with the arrival in the

colony of the rinderpest epizootic: a ‘cattle plague’ that over the

preceding five years had raced the length of Africa and decimated cattle

CHRIS ROCHE, a graduate of the University of Cape Town, has spent the last ten years

in the Southern African ecotourism industry. He is currently based in Johannesburg as

communications manager and environmentalist for Wilderness Safaris. His research interests

have focused on environmental history and historical ecology in the former Cape Colony, and

the integration of this into modern conservation planning.

http://journals.cambridge.org Downloaded: 30 Aug 2013 IP address: 137.158.158.60

158 THE END OF SPRINGBOK TREKS

populations from Uganda to the Transvaal and finally the Cape Colony

(Henning 1956: 828–33). Given its apparent coincidence in both space

and time with the last great springbok trek in 1896 and 1897, rinderpest

has long been claimed as the root cause of the extinction of springbok

treks (Skinner 1993: 302; Skinner and Louw 1996: 7). There is no

hard evidence to support this conclusion, however, and there are more

plausible explanations.

After first examining the basic ecology of the species and the

important role of trekbokke in the Karoo ecosystem, this article

investigates any potential relationship between rinderpest and the

cessation of springbok treks. Having discovered no more than a

circumstantial link, a combination of anthropogenic influences is

introduced as the primary causative complex in the extinction of this

phenomenon. The loss of the treks robbed the Karoo of a cornerstone

of its ecosystem and severely disrupted the natural processes of the area.

KAROO CORNERSTONE: THE ROLE OF SPRINGBOK IN AN ARID ECOSYSTEM

The broader Karoo is in fact comprised of two distinct biomes, the

Succulent Karoo in the west (winter rainfall) and the (summer rainfall)

Nama Karoo in the central and eastern reaches (see Figure 1). Over

the past 50 years the state of this semi-desert environment has provided

much fuel for an extended and ongoing debate about environmental

degradation in the region and the extent of man’s influence on this

apparent decline (Acocks 1953: 1–92; Hoffman and Cowling 1990:

286–94; Dean and Roche 2007: 57–63). Much of this debate has

centred on the composition of available vegetation (both grasses and

shrubs and the ratio between them) and what this make-up indicates

as to past agricultural and pastoral practices. Certainly it is clear

from agricultural censuses conducted by the colonial administration

that sheep densities in particular have at times been damagingly high

and that as a result the productivity of the system and its ability to

sustain high stock populations have declined over time (Dean and

MacDonald 1994: 281–98; Beinart 2003: 1–27). These trends were

already recognizable in some areas of the Karoo, and its earlier settled

fringe, by the late nineteenth century. It is here that the foundations of

the debate lie (Shaw 1875: 202–8; Graaff-Reinet Advertiser 13 February

1899, 2 February 1900).

While this discussion continues unabated today it is nonetheless

indisputable that the natural processes of the Karoo are now largely

or, in some cases, entirely disrupted. The first fifty years of the

twentieth century exerted considerable impact, of course, but this

massive disruption began to occur primarily in the late nineteenth

century during a period when anthropogenic impacts on then extant

natural processes were spectacular.

By 1878 the quagga Equus quagga quagga was extinct (Skinner and

Smithers 1990: 720). Eland Tragelaphus oryx had been extirpated

from the Karoo even earlier (Bryden 1889: 291), and formerly

http://journals.cambridge.org Downloaded: 30 Aug 2013 IP address: 137.158.158.60

THE END OF SPRINGBOK TREKS 159

characteristic species such as black wildebeest Connochaetes gnou, red

hartebeest Alcephalus buselaphus, blesbok Damaliscus dorcas phillipsi

and gemsbok Oryx gazella occurred only at negligible densities

(C. Roche, unpublished data). Of the larger herbivores, only springbok

still occurred in significant numbers. Most importantly, however,

springbok, and specifically the enormous herds of so-called trekbokke,

continued to exhibit irruption and nomadism in sync with the cyclical

fluctuations and functioning of the Karoo ecosystem (Roche 2004:

110–54). Irruption, an arid ecosystem survival strategy that sees

population explosions during times of plenty and subsequent crashes

or out-migration in the harder times that follow, is today well known in

certain bird species occurring in the Karoo (Dean and Siegfried 1997:

11–21; Milton, Davies and Kerley 1999: 183–207; Dean and Milton

2001: 101–21) and other arid areas (Davies 1984: 183–4) but was

not recognized during the colonial period. Nonetheless we know from

ethnographic and archaeological records of the hunter-gatherer/Xam

and Swyèi (Bushman clans that inhabited this forbidding desert before

the arrival of Europeans) that the movements of trekbokke and their

cyclical abundance were a cornerstone of survival in the Karoo, and

an aspect of the natural process around which much else revolved

(Roche 2004: 45–64; Roche 2005: 1–22). The other large herbivores

such as the quagga and eland had in all likelihood also exhibited similar

movements, albeit on a significantly smaller scale and as a result of

slightly different stimuli, but by the latter half of the nineteenth century

occurred at such low densities that the exact nature of these movements

is not known.

Endowed with exceptional fecundity, springbok in the central parts

of the Nama Karoo displayed a cyclical build-up of numbers and

ensuing emigration to neighbouring areas in both the Succulent

Karoo to the west (with its winter rainfall) and the higher-rainfall

areas of the eastern Nama Karoo to the east. This cyclical build-

up was naturally allied to rainfall and the response of both grass

and shrubs; it did not take place every year, but rather in tandem

with what has been termed a ‘quasi-periodic rainfall oscillation’. This

oscillation sees an average 18-year cycle of two consecutive nine-year

periods of above- and below-average rainfall (Tyson and Preston-

Whyte 2000: 322; Roche 2004: 83–90). During extended periods of

high rainfall, springbok numbers grew exponentially, particularly in

normally marginal areas with low productivity in normal or dry years

but high fertility during wet years. During the inevitable droughts that

followed, these swollen herds migrated at random to whatever grazing

remained, usually in adjacent higher-rainfall areas of the Karoo that

may not necessarily have seen a dramatic local increase in springbok

numbers. As the cycle progressed, with droughts increasing in duration

and forage availability decreasing, springbok numbers declined and

even crashed. This biome-wide process, although also exploited by

them, was generally compatible with the initial transhumance of settlers

of the region, who were themselves partly nomadic with their herds

and flocks of cattle, sheep and goats. Later, however, the springbok

http://journals.cambridge.org Downloaded: 30 Aug 2013 IP address: 137.158.158.60

160 THE END OF SPRINGBOK TREKS

Graaff-Reinet

Philipstown

FIGURE 1 Extent of the Succulent Karoo and Nama Karoo in the admin-

istrative districts of the Cape Colony

trek phenomenon was inevitably disruptive of attempts at organized

stock farming and increasingly came into conflict with this evolving

land use.

While early settlers in the region were initially forced by dependence

on the vagaries of weather patterns to mimic natural nomadic

processes – such as those of the springbok – increasing numbers of

people, allied with advances in technology and infrastructure, meant

that transhumance evolved into farming practices characterized by

greater permanency. Windmills and boreholes allowed the invasion of

the previously inhospitable Karoo by permanent stock farmers, their

flocks and their rifles, and the ensuing enclosure with wire fencing

increasingly prevented free movement of wild ungulates such as the

trekbokke, at least into the most productive areas integral to both stock

and game. These changes in the Karoo landscape were censused on

a regular basis by the colonial administration and can be mapped

at the relatively coarse resolution of districts, the colonial units of

administration (see Figure 1).

While rinderpest, the so-called ‘cattle plague’, was previously

believed to have been the primary cause of the demise of the springbok

treks, this article establishes that a combination of anthropogenic

factors – and most importantly enclosure and hunting – were in fact

responsible, and that rinderpest played little or no role in the demise of

the phenomenon. The dramatic extinction of this phenomenon allowed

http://journals.cambridge.org Downloaded: 30 Aug 2013 IP address: 137.158.158.60

THE END OF SPRINGBOK TREKS 161

the replacement of the Karoo’s fundamental, and essential, boom and

bust cycle – and its most apparent exponent, the trekbokke – with an

artificial system regulated more by market demand than environmental

cycles. The eclipse of the trekbokke symbolized the triumph of human

economies over undesirable ecological processes and the beginning of a

long process of environmental degradation.

‘THE DAYS OF THE GREAT “TREKS” ARE OVER’ – REASONS FOR THE END

As a number of authors have noted, 1896–7 witnessed the last ‘mega-

trek’ of springbok in the Karoo. This trek, the result of several years

of good rainfall followed by a devastating drought, was concentrated in

the Britstown district. The trekbokke remained clustered here for several

months before favourable rains further west caused their dispersal.

Due to the unusually concentrated nature of the trek, springbok

suffered enormous and previously unsustained mortalities at the hands

of settlers, many of whom had travelled to the area specifically

to hunt the trekbokke. Vosburg became known as a ‘springbuck town’

(De Britstowner 21 October 1896) and various lurid descriptions of veld

strewn with offal and abandoned carcasses and the massive trade in

ammunition and springbok skins and biltong appeared in both the local

and British press (Roche 2004: 110–54).

Thereafter, dramatically reduced springbok numbers, scattered

across the remaining unfenced areas of the Karoo, continued to exhibit

some limited localized movement in response to rain, but not on a scale

that could be considered treks. Rather these movements might be better

understood as seasonal concentrations and the trekbok population in

fact never recovered. Explanations for the disappearance of the mass

migrations remain wholly unsatisfactory, often being based on nothing

more than conjecture and coincidence. Skinner, and subsequently

Skinner and Louw, attempted to provide a more reasoned explanation.

Skinner was initially dismissive of fencing as a cause, claiming, on the

basis of a single oral source, that enclosure began only twenty years

after treks had ended. While conceding that hunting may have played a

role in reducing numbers, he contended that the rinderpest epidemic,

which spread rapidly in the Cape from 1896, was ‘almost certainly’

the overriding cause (Skinner 1993: 302). Skinner and Louw (1996:

7) were more circumspect, concluding that the treks had probably

been terminated by a combination of factors such as increases and

advances in stock farming, fencing and hunting techniques, but still

singled out rinderpest as the single most important cause. While this

latter combination has the ring of common sense to it, it has not been

substantiated to any significant extent and even the passage of the

rinderpest epidemic through the Cape Colony, although tracked with

regard to social impact and veterinary science (van Onselen 1972: 473–

88; Phoofolo 1993: 112–43; Gilfoyle 2002: 161–200; Gilfoyle 2003:

133–54; Phoofolo 2004: 94–177), has yet to be plotted chronologically

or quantitatively in any great detail. Skinner and Louw’s claims

http://journals.cambridge.org Downloaded: 30 Aug 2013 IP address: 137.158.158.60

162 THE END OF SPRINGBOK TREKS

therefore remain based on intuitive logic, not empirical evidence, and

can at best be regarded as a provisional hypothesis.

‘THE FEARFUL PEST’: THE SPREAD AND IMPACT OF RINDERPEST IN

THE CAPE COLONY, 1896–8

Rinderpest, endemic in Europe and Asia, reached northern Africa in

the area of Eritrea in 1889 and spread southwards via the transport

oxen of the Italian army in 1890 (Henning 1956: 829). As an airborne

viral disease attacking both domesticated and wild ruminants in the

form of cattle and various ungulate species, and causing fatalities in less

than 14 days in over 90 per cent of infected animals, it spread rapidly

southwards (Jacobs 2002: 29). Rinderpest reached the Cape Colony in

1896, leaving a swathe of dead livestock in its wake (Henning 1956:

829–31; Jacobs 2002: 29; Bengis et al. 2003: 260).

Skinner’s conclusion that rinderpest was the primary cause of the

termination of springbok treks appears to be based on two pieces of

circumstantial evidence. First, the epidemic coincided roughly with the

end of springbok treks; second, springbok treks typically originated in

the Kalahari and moved south across the Orange River into the Cape

Colony and the Karoo – a path that would have exposed the trekbokke to

rinderpest as the plague swept down through Botswana from Zimbabwe

and into the area north of the Orange River. Skinner’s contention that

springbok treks originated north of the Orange River and not to the

south (Skinner 1993: 298) appears, however, to be a misinterpretation

of Andries Stockenstrom’s analysis of the phenomenon. Stockenstrom

was in fact adamant that the treks originated between the colonial

border and the River itself; in other words, south of the Orange River

and thus outside of the Kalahari (Hutton 1887: 37–9).

Although springbok apparently did trek south across the Orange

River from the Kalahari into the Karoo in 1896 (Roche 2004: 129–

45), these animals did not comprise a significant portion of the last

mega-trek and, contrary to Skinner’s supposition, would appear to

have constituted only a very minor fraction of it (Roche 2004: 144).

Indeed, this is the only period during which a springbok trek crossed

the Orange River from the Kalahari into the Karoo in the nineteenth

century that could be discerned in a thorough reading of the Karoo

colonial press and numerous other sources (Roche 2004: 13–152).

Such movements cannot therefore be considered to have been the

norm. The overwhelming majority of the springbok involved in the trek

of 1896 would therefore not have been exposed to rinderpest. This does

not exclude the possibility that a small minority introduced rinderpest

at a later stage, subsequently decimating the tightly massed population

south of the Orange River, but it does cast some doubt on one premise

of Skinner’s explanation.

As far as the other coincidence is concerned, the rinderpest epidemic

was closely tracked by the colonial administration. The path and timing

of its entry into both the area immediately north of the Orange River

http://journals.cambridge.org Downloaded: 30 Aug 2013 IP address: 137.158.158.60

THE END OF SPRINGBOK TREKS 163

FIGURE 2 The spread of rinderpest in central southern Africa by January

1897 (Anon 1897: 729–31)

and the Cape, as well as its impact on livestock in border districts

from Hope Town through to Namaqualand, were documented in

considerable detail (see Figure 2). This fact makes a comparison of

the spread of rinderpest with the movements of the trekbokke possible.

From its first recorded occurrence in southern Africa on 5 March

1896 in Bulawayo, rinderpest spread rapidly. As early as that same

month a cordon of Cape Mounted Police had been established along

the northern and eastern border of the Colony to prevent the epizootic

crossing from Rhodesia and the Bechuanaland Protectorate (Courier

26 March 1896). By May this cordon had been breached and hastily

redeployed further south (Graaff Reinet Advertiser 15 June 1896).

By June the Kalahari was described as ‘swept clean by rinderpest’

rendering it ‘hoofless’ (Graaff Reinet Advertiser 15 June 1896). Nothing

but dead cattle were apparently to be seen along the Molopo River, with

massive losses of both revenue and animals recorded: the Protectorate

estimated a loss of £4,000,000 while the Bechuana under Khama were

said to have lost 600,000 head of stock (Courier 25 June 1896). In the

Transvaal any hope of stamping out the disease outside the cordon (see

Figure 2) was surrendered by July when the veld was said to be ‘simply

rotten with disease stricken game, koedoe, gemsbok, duiker &c. being

in such a condition that policemen simply ride up and shoot them down

with revolvers’ (Graaff Reinet Advertiser 6 July 1896). Further south

similar fatalism prevailed. Contrary to Skinner’s claim that rinderpest

had broken out in Vryburg in May (Skinner 1993: 302), it is only

two months later in July that this is in fact the case (Courier 16 July

http://journals.cambridge.org Downloaded: 30 Aug 2013 IP address: 137.158.158.60

164 THE END OF SPRINGBOK TREKS

1896). By September it had reached Herbert on the northern bank of

the Orange River, leading to the feeling that ‘the fearful pest . . . [was]

most likely to find its way eventually to the coast’ (Courier 10 September

1896).

Attitudes towards rinderpest within the Colony itself varied,

however. There was the inevitable panic-tinged response that regarded

any unusual cattle death as evidence of the epidemic and imagined

the disease to be advancing far more quickly than it was. This was

counter-balanced by sceptics who believed the threat to be exaggerated.

For example, an outbreak of rinderpest was prematurely reported for

Kenhardt in September, having to be corrected the following week as a

mistake (Courier 28 September 1896; 1 October 1896), and the same

process occurred in Prieska the following July (De Britstowner 14 July

1897; 28 July 1897). Conversely some farmers of the Prieska district

felt that, in the light of the rinderpest fence that prevented access to the

Orange River, it was ‘better to have rinderpest than fence, as the latter

will mean death to all river farm cattle and stock generally, as no other

water is available owing to the drought’ (Courier 8 October 1896).

Rinderpest duly spread from Vryburg and Herbert to Kimberley by

October 1896 (Skinner 1993: 302) and thereafter broke out in the Free

State, being well established along its southern and eastern borders

by January 1897 (see Figure 2). From here it crossed to the Colony

in March that year (Courier 30 March 1897; see also Phoofolo 1993:

114). Although rinderpest penetrated the eastern districts, its route

from the Kalahari into the northern districts of the Karoo continued

to be obstructed: the double barbed wire fence along the Orange

River from Hopetown to Prieska was guarded by 50 special police

and their supervisors. From Prieska to the Kenhardt boundary another

160 ‘specials’ were present and from here to Zeekoestreek a further

230. Protection along the remaining 300 miles to the west coast was

considered ‘exceedingly unsatisfactory’ and this section was thought

to represent the greatest danger of infection to the northern districts

(De Britstowner 5 May 1897). As an added precaution, and to create

a buffer zone, Gordonia was declared an infected district prior to any

documented rinderpest outbreak (De Britstowner 19 May 1897) and by

May, despite appearing on the borders, the disease had yet to enter the

district (Anon 1897: 729–31).

Partly in anticipation of a rinderpest outbreak expected to decimate

domestic stock and render the carcasses unfit for human consumption,

meat prices in Kenhardt had been on the increase since February (De

Britstowner 10 February 1897) and in October rinderpest did finally

reach the district (Victoria West Messenger 8 October 1897). The disease

had advanced from Hopetown via Britstown in September, and then on

to Victoria West (Victoria West Messenger 1 October 1897) and Prieska.

As a result of limited inoculation the cattle population in Britstown was

‘devastated’ (De Britstowner 1 September 1897; 15 September 1897).

The interior and extreme north-western districts were not affected,

however, and by August 1898 the Civil Commissioner believed that

rinderpest had ‘entirely disappeared’ from Kenhardt (Anon 1898a:

http://journals.cambridge.org Downloaded: 30 Aug 2013 IP address: 137.158.158.60

THE END OF SPRINGBOK TREKS 165

237–43). There was a risk of reintroduction from Gordonia where it

still existed, but, despite fears that it would remain for ‘some time’

(Anon 1898a: 237–43), by October it had been eradicated from this

district as well (Anon 1898c: 493–502).

Rinderpest, although relatively short-lived in the Colony, had a

massive impact and, writing towards the end of 1897, a correspondent

to the Victoria West Messenger summed up the devastating dual effects

of drought and rinderpest as a pivotal moment in South African history:

Ja als er ooit iets belangryks was om opgestekend te worden in de geschiednis van

Zuid Afrika, dan is het de gebeurtenissen van 1896 en 1897, de zware droogten,

sterven van duizenden van groot en klein vee, door droogte en rinderpest. (Yes,

if ever there was something important to emphasize in the history of South

Africa, it is the events of 1896 and 1897, the severe drought, the deaths of

thousands of large and small stock as a result of drought and rinderpest.)

(Victoria West Messenger 22 October 1897)

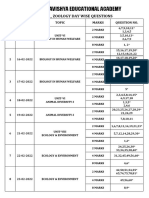

As will be seen in Figure 6 and Figure 7, the impact of rinderpest on

settler cattle and sheep holdings is easily quantifiable. For the purposes

of this argument, and because the colonial administrative districts

regularly changed boundaries and size, the core of the Succulent

and Nama Karoo can be divided into four regions (see Figure 3),

allowing a spatial analysis of the impact of rinderpest and other factors.

The four regions are roughly aligned to certain characteristics such

as geographic location and dominant habitat and rainfall patterns.

The north-western districts (Namaqualand, Van Rhynsdorp and

Clanwilliam), for example, are comprised mainly of Succulent Karoo in

a winter rainfall area, while the midland districts (Murraysburg, Graaff-

Reinet, Middelburg, Cradock) are comprised of mountainous Nama

Karoo and grassland in the highest rainfall region under discussion,

with precipitation occurring mainly in summer. The northern and

central districts (Kenhardt, Calvinia, Fraserburg, Carnarvon, Prieska,

Victoria West) and the north-eastern districts (Hopetown, Britstown,

Richmond, Hanover, De Aar, Philipstown, Colesberg) comprise the

bulk of the Nama Karoo and can be separated on the basis of rainfall

and vegetation. The north-eastern districts experience significantly

higher and more reliable rainfall, and as a consequence feature more

extensive grass cover.

The north-eastern districts were worst hit in terms of cattle numbers,

suffering a decrease of almost 68 per cent between 1891 and 1898, with

only minor recovery demonstrated by 1911. Similarly, the northern and

central region lost over 64 per cent of cattle between 1891 and 1898

and numbers rose only slightly by 1911. An analysis of the effect of

rinderpest on cattle density, rather than absolute numbers, is even more

revealing: the number of cattle per hectare in the very large geographic

area of the northern and central districts fell by only a third between

1891 and 1904, while in the comparatively much smaller north-eastern

districts this figure was over 70 per cent, indicating just how hard hit

this part of the Colony was by the disease. That these losses were

http://journals.cambridge.org Downloaded: 30 Aug 2013 IP address: 137.158.158.60

166 THE END OF SPRINGBOK TREKS

FIGURE 3 The districts of the core of the Nama and Succulent Karoo divided

into four regions: north-western districts, northern and central districts, north-

eastern districts, and midland districts

driven by rinderpest and not drought is supported by the fact that

the north-western districts, which suffered an even worse period of

drought in the mid-1890s, show a loss of 53 per cent between 1891

and 1898 and a decline in density between 1891 and 1904 of only 12.5

per cent. Furthermore, this region reflected a significant increase by

1911. An analysis of sheep numbers shows a similar trend over 1891

to 1898, with the northern and central districts and those of the north-

east suffering losses of 57.3 per cent and 43.1 per cent respectively,

while over the same period the sheep population of the north-western

districts declined by only 22.9 per cent. A comparison of densities once

again offers more insight: it shows a decrease in the number of sheep

per hectare in the northern/central districts and the north-eastern

districts of almost 65 per cent and 59 per cent respectively between

1891 and 1904. Sheep proved more resilient to rinderpest than cattle

and, particularly in these two regions, numbers grew significantly fol-

lowing recovery from both this disease and drought.

The impact of rinderpest on wild ungulates is not so easily quantified.

The estimates of game numbers in the Colony provided by the

Agricultural Department and published by the Western Districts Game

Protection Association (WDGPA) (see Table 1) suggest a slight

decrease in numbers of key species occurring in the northern districts

http://journals.cambridge.org Downloaded: 30 Aug 2013 IP address: 137.158.158.60

THE END OF SPRINGBOK TREKS 167

TABLE 1 Population estimates of large wild game species occurring in the

Achterveld (back country), 1897–19081

of the Colony after July 1897. It is difficult, however, to draw any

firm conclusions from the impressionistic estimates provided by Civil

Commissioners, which do not, for the most part, differentiate between

districts. Indeed, although it was reported that some game, such as

common duiker Sylvicapra grimmia and grey rhebok Pelea capreolus

near East London (De Britstowner 13 October 1897) and eland,

kudu Tragelaphus strepsiceros, red hartebeest, klipspringer Oreotragus

oreotragus, steenbok Raphicerus campestris and an ‘antelope’ at Rhodes’s

Groote Schuur Estate in Cape Town (De Britstowner 1 December

1897), had succumbed to rinderpest, it was admitted that ‘the amount

of loss from this cause cannot be accurately ascertained’ (Graaff Reinet

Advertiser 24 August 1898). Nonetheless the WDGPA warned that:

‘The effect of rinderpest on large game has been disastrous in several

tracts of country . . . . From the best information available it would

appear that kudu, eland and buffalo suffered most; but hartebeest, the

other antelope, were affected only to a slight extent’ (Pringle 1982:

69). This latter suggestion would seem to be supported by the fact

the Kalahari was reported to be ‘teeming with vast herds of gruisbok

[gemsbok], hartebeest, wildebeest and wild ostriches’ in 1899 (Anon

1899: 477–80) and that red hartebeest occurred in sufficient numbers

to trek out of the Kalahari to Upington towards the end of 1903.

Even a single blue wildebeest appeared at the same time (Victoria West

Messenger 16 October 1903; 4 December 1903).

Modern knowledge of the disease would indeed suggest that while

bovids, such as buffalo Syncerus caffer, tragelaphids, such as kudu, and

suids, such as warthog Phacochoerus africanus, were heavily impacted

1

Estimates for the respective years were published in the following sources: Graaff Reinet

Advertiser 5 August 1897, 24 August 1898, 7 September 1900; Courier 22 October 1908. The

increase in the number of ostriches in the Prince Albert district in the 1908 figures may have

been due to escape or release of once-domesticated birds (Courier 16 April 1903).

http://journals.cambridge.org Downloaded: 30 Aug 2013 IP address: 137.158.158.60

168 THE END OF SPRINGBOK TREKS

by rinderpest (Henning 1956: 840–1; Bengis et al. 2003: 360), other

species may not have suffered declines on the same dramatic scale.

The omission of springbok from any description in the colonial press

of the devastation of rinderpest on wild game suggests they were not

obviously devastated by the disease. In addition the persistence of

gemsbok in Kenhardt and the fact that the ostrich Struthio camelus

population, a species not known to be susceptible to rinderpest, showed

similar trends to those of gemsbok and red hartebeest would seem to

indicate that the rinderpest did not completely obliterate wild game

populations in the northern districts and that some other factor, such

as the protracted drought or illegal hunting during this period, is likely

to have been the primary driver of these fluctuations.

In addition, farmers’ inherent fear of the transmission of disease from

wild animals to livestock should also be borne in mind. This fear is

clearly evident in the northern districts of the Colony in the case of

another disease, scab, which was endemic in sheep and goats as well as

springbok. Springbok suffering from scab were blamed for the spread

of the disease (Victoria West Messenger, 26 October 1894) and the

restrictions placed on the movement of stock (but not on springbok)

under the Scab Act attacked (De Britstowner, 29 November 1895). A

springbok skin infected with scab was eventually sent to Hutcheon, the

Colonial Veterinary Surgeon for confirmation. He found that a different

species of sarcoptes mite was involved, however, and that, although

it might possibly affect non-fleeced animals such as the boer goat, its

transmission to sheep was very unlikely (De Graaff Reinetter, 16 August

1894; Anon 1895: 113–18).

The obsession with disease transmission between wild and

domesticated ungulates suggests that any hint of rinderpest in the

springbok herds would have sparked vigorous calls for their complete

extermination; at the very least, if the plague had affected springbok

numbers, this would have been noted. No mention whatsoever of

rinderpest affecting springbok appears in the contemporary press,

however.

Rinderpest, then, did penetrate the districts of the northern and

north-eastern Karoo and inevitably had a dramatic impact on stock

numbers. However, as can be seen in Figure 4 and in the discussion

that follows, the progression of the plague followed in the wake of the

springbok dispersal, and rinderpest and springbok treks did not at any

point coincide.

Over the course of 1896 the overwhelming bulk of the trekbokke had

concentrated in the Britstown district. The springbok had moved into

this area from the Kenhardt, Prieska and Victoria West districts in

January of that year and, aside from some movements back and forth

between Britstown and the neighbouring areas of Prieska and Victoria

West, stayed concentrated there until November and December, when

they dispersed westwards. January 1897 saw good concentrations in

Kenhardt, but March saw the beginnings of a movement east in Prieska

and then east and south east from there in April into both Britstown and

the vicinity of Van Wyk’s Vley in the northern parts of the Carnarvon

http://journals.cambridge.org Downloaded: 30 Aug 2013 IP address: 137.158.158.60

THE END OF SPRINGBOK TREKS 169

FIGURE 4 Comparison of timing of rinderpest and trekbokke in the northern

parts of the Cape Colony

district (Roche 2004: 136–48). By March rinderpest had been recorded

in the nearby district of Hopetown, but the disease was contained

there for some months and did not spread further west. The trekbokke,

meanwhile, did not penetrate as far as Hopetown during 1897. Indeed,

by May 1897 the springbok had moved west into the Kenhardt district

and from there seem to have dispersed both north and south, with no

further records of concentrations anywhere in the Karoo that year.

By contrast, it was only in September that year that rinderpest moved

into the districts of Britstown, Prieska and Victoria West (Courier 30

March 1897; Phoofolo 1993: 114), four months after the springbok

had dispersed from the former two districts and a full ten months after

they had left Victoria West. The movement of the disease westwards

was also several months behind that of the springbok, arriving as it

did in Kenhardt in October (Victoria West Messenger 1 October 1897;

8 October 1897), at least four months after the apparent dispersal of

springbok. In addition, the disease did not penetrate as far west as

Namaqualand or as far south as Fraserburg and Sutherland (Anon

1898b: 301–10).

It can safely be said, then, that rinderpest was not the primary cause

of the cessation of springbok treks, and that, although the possibility of a

limited role cannot be completely discounted, there is no contemporary

http://journals.cambridge.org Downloaded: 30 Aug 2013 IP address: 137.158.158.60

170 THE END OF SPRINGBOK TREKS

evidence to suggest this. Other potential causes of the demise of the

springbok treks therefore need to be examined.

‘THEY DROVE THE SPRINGBOKS AWAY’ – THE INCREASE IN LIVESTOCK AND

HUMAN POPULATIONS, 1865–1911

In 1867, in reply to a question as to whether illegal hunting had been

the cause of the demise of the great game herds of the Colony, the

Auditor General replied that this was not altogether the case and that:

‘When I first came out to the Colony in 1830, there were very few flocks

of sheep in the district I lived in; as the sheep increased they drove

the springboks away. The quantity of game has diminished quite as

much by the increase of sheep as by other causes’ (Cape of Good Hope

1867: 11).

This increase in livestock numbers in the Colony as a whole and

in the Karoo has been noted by a number of scholars (Christopher

1976: 55–86; Dean and MacDonald 1994: 281–98; Beinart 2003:

1–27), mostly with regard to its contribution to the Cape economy

and impact on grazing conditions and carrying capacities. The latter

theme in particular was already well developed by the end of the

nineteenth century. The Zwarte Ruggens Farmers’ Association, for

example, decried the replacement of the natural rotation system of

herds of wild game with overstocking, overgrazing, erosion, increased

stock mortality and lowered output. Their fear was that if this system

continued the Karoo would become ‘a region of emptiness, howling

and drear – Which man has abandoned from famine and fear’ (Graaff

Reinet Advertiser 2 February 1900). MacKenzie is another who has

noted the increase in livestock numbers and concomitant decrease in

game numbers in the Cape Colony (MacKenzie 1988: 92).

Contrary to contemporary opinion, however, springbok and sheep do

not under normal circumstances compete for the same food resources

in the Karoo (Davies and Skinner 1986a: 115–32; Davies and Skinner

1986b: 133–47; Davies, Botha and Skinner 1986: 165–76). It was not

direct competition between the two species, therefore, that pushed the

indigenous springbok back. Rather, disturbance and an increasingly

impoverished ecosystem, resulting from overstocking and overgrazing,

had this effect. Perhaps even more important was the settler farmer

perception of direct competition, and reaction to it through hunting and

driving springbok away, along with the steady settlement of previously

unoccupied land. The human advance moved in tandem with an

increase in sheep and other livestock numbers and it is useful, despite

some doubt in official statistics (Nell 1998), to track the increase in

numbers and densities of all these species over the period 1865 to 1911.

Figure 5 clearly shows an increase in livestock (cattle, sheep and

goats) numbers and densities in those parts of the Karoo historically

associated with springbok treks over the course of the final few decades

of the nineteenth century. Prior to the 1898 census a steady increase

in livestock is apparent across the rural districts of the Cape Colony.

http://journals.cambridge.org Downloaded: 30 Aug 2013 IP address: 137.158.158.60

THE END OF SPRINGBOK TREKS 171

FIGURE 5 Increase in livestock numbers and densities in districts historically

associated with springbok treks, 1865–19112

The census in 1898, however, revealed a dramatic and obvious decline

that can be attributed primarily to rinderpest. This general increase,

followed by the rinderpest effect, is even more marked when broken

down into the regions previously considered in discussing the impact

of rinderpest. The north-western districts, the northern and central

districts, and the north-eastern districts all showed an increase in cattle

numbers up until 1891, with this growth persisting only in the north-

western districts thereafter. Sheep numbers also showed consistent

growth across the board between 1865 and 1891, and post-rinderpest

growth continued to a limited degree in both the north-western and

northern and central districts. It is possible that the better-watered

north-eastern districts, having been the target of the earlier thrust of

commercial pastoral expansion, had already reached and even exceeded

their carrying capacity by 1891.

It is clear that, aside from the mortalities caused by rinderpest,

there was a general increase in both cattle and sheep numbers in

all the regions prior to the springbok trek of 1895–6. The general

2

Districts accounted for in Figure 5 include: Namaqualand; Van Rhynsdorp; Clanwilliam;

Calvinia; Sutherland; Fraserburg; Carnarvon; Kenhardt; Prieska; Beaufort West; Prince

Albert; Murraysburg; Graaff-Reinet; Cradock; Richmond; Britstown; Hanover; De Aar;

Philipstown; Middelburg; Hopetown; Colesberg; Victoria West. Cattle, sheep and goat

numbers comprise all species occurring (Cape of Good Hope (1866; 1876; 1892; 1898; 1905;

Union of South Africa 1912).

http://journals.cambridge.org Downloaded: 30 Aug 2013 IP address: 137.158.158.60

172 THE END OF SPRINGBOK TREKS

FIGURE 6 Cattle numbers and densities in the north-western districts,

northern and central districts, and north-eastern districts, 1865–19113

FIGURE 7 Sheep numbers and densities in the north-western districts,

northern and central districts, and north-eastern districts, 1865–19114

3

Cattle numbers given in Figure 6 comprise all breeds of cattle (Cape of Good Hope 1866;

Cape of Good Hope 1876, 1892, 1898, 1905; Union of South Africa 1912).

4

Sheep numbers given in Figure 7 comprise numbers of both woolled sheep and all other

species (Cape of Good Hope 1866, 1876, 1892, 1898, 1905; Union of South Africa 1912).

http://journals.cambridge.org Downloaded: 30 Aug 2013 IP address: 137.158.158.60

THE END OF SPRINGBOK TREKS 173

FIGURE 8 Densities of sheep per 1,000 hectares, 1891

FIGURE 9 Densities of sheep per 1,000 hectares, 1904

http://journals.cambridge.org Downloaded: 30 Aug 2013 IP address: 137.158.158.60

174 THE END OF SPRINGBOK TREKS

FIGURE 10 Densities of sheep per 1,000 hectares, 1911

upward trend in sheep numbers is most marked, with sustained

growth occurring in the north-western and northern and central

districts, notwithstanding the impact of the rinderpest, drought and

indiscriminate stock theft during the Anglo-Boer War (Constantine

1996: 20–44; 133–49; 165–75). These regions were essential to the

phenomenon of springbok treks, providing, as they did, the space for

population growth during favourable climatic conditions. The increase

in livestock numbers here cannot have boded well for the antelope and

its natural population fluctuations. Equally importantly, stock densities

remained highest in the north-eastern districts and continued to prevent

the overflow of trekbokke from the northern and central districts into this

area. Although, as can be seen from figures 8–10, sheep densities fell

slightly across the board between 1891 and 1904, the trend for greater

densities to persist in the eastern districts, and effectively exclude

trekbokke, continued.

The colonization of the Achterveld by both humans and livestock

was of course facilitated by the provision of water; an analysis of

the increase in boreholes and wells thus provides an insight into this

process. Figure 11 reflects the significant increase in artificial sources

of permanent water over the period 1891 to 1911. This development

was instrumental in enabling extensive and permanent pastoralism in

the previously seasonally utilized northern Cape Colony. Perhaps more

important than the increase in livestock numbers however, was the

http://journals.cambridge.org Downloaded: 30 Aug 2013 IP address: 137.158.158.60

THE END OF SPRINGBOK TREKS 175

FIGURE 11 Numbers and densities of wells (artesian and other) in the north-

western districts, northern and central districts, and north-eastern districts,

1891–1911 (Cape of Good Hope 1892; 1905; Union of South Africa 1912)

associated growth in the human population, and more specifically that

of white settlers (see Figure 12).

Settlers brought with them their own need for protein. Wild game,

such as springbok, provided an important part of this, with domestic

stock such as woolled sheep being preserved for the value of their

wool on the market rather than consumed for sustenance. Even more

importantly springbok, especially the trekbokke, did massive damage

with their myriad hooves to the pasture and gardens maintained by

farmers. Even when the veld was not trampled to dust by the passage

of large herds of springbok, it was said that sheep would not graze

where the antelope had cropped the grass (Courier 12 August 1880).

This damage, both real and imagined, encouraged the indiscriminate

slaughter of springbok. Stockenstrom, in 1824, had identified the

arid areas of the northern and central districts, and the absence

of a permanent settler presence, as the key to the springbok treks

(Hutton 1887: 37–9). With this refuge increasingly penetrated and

ultimately lost to settlement and livestock, the Karoo springbok treks

were seriously imperilled.

‘SECURING HIS ACRES’: THE EFFECTS OF FENCING

Another innovation brought by settlers to the springbok range was

fencing. This development was integral to both control and ownership

of the landscape (van Sittert 2002) and in one case the process of

fencing or enclosure was described as a farmer ‘securing his acres’

http://journals.cambridge.org Downloaded: 30 Aug 2013 IP address: 137.158.158.60

176 THE END OF SPRINGBOK TREKS

FIGURE 12 Numbers and densities of white settlers compared with total

population in the north-western districts, northern and central districts, and

north-eastern districts, 1865–1911 (Cape of Good Hope 1866, 1876, 1892,

1898, 1905; Union of South Africa 1912)

(Victoria West Messenger 4 October 1880). As early as 1880 the Victoria

West Messenger argued for wide-scale fencing of farms to protect both

stock and grazing against the invasion of springbok herds (Victoria

West Messenger 4 October 1880) and it is clear that as wire fencing

spread it proved effective against invasion by trekbokke. Springbok

did occasionally damage and tear down small stretches of fence (De

Britstowner 10 April 1896; Cronwright-Schreiner 1899: 45; Green

1955: 39) but the confidence with which the Colesberg Advertiser could

refute claims of a trek in the area in 1893 by citing the fact that the

whole country was ‘traversed by a network of wire fences’ (Colesberg

Advertiser 21 July 1893) suggests that this generally proved an efficient

method of exclusion. The fact that in 1893 only about 17 per cent of

the Colesberg district was enclosed indicates the extent to which even

limited enclosure effectively curtailed springbok movements.

Similarly, in Graaff-Reinet the initial decline in springbok numbers in

the 1850s was blamed on fencing and the end of the age of the trekbokke

locally was widely ascribed to enclosure. Ironically, however, this

fencing process was driven by the economic boom in ostrich feathers,

which also allowed the recovery of the local springbok population

because landowners ‘jealously protected’ their encamped populations

of trekbokke in order to allow hunts with family, friends and neighbours

(Roche 2003: 86–108). This transformation in the nature of springbok

populations from nomadic to sedentary was an irrevocable one that was

to follow in the wake of fencing’s advance across the Colony.

http://journals.cambridge.org Downloaded: 30 Aug 2013 IP address: 137.158.158.60

THE END OF SPRINGBOK TREKS 177

FIGURE 13 The increase in fencing (hectares) and the extent (%) of the

country enclosed in the north-western districts, the northern and central

districts, the north-eastern districts, and the midland districts, 1891–1911

(Cape of Good Hope 1866, 1876, 1892, 1898, 1905; Union of South Africa

1912)

Fencing was initially most concentrated in the midland divisions

of the Cape Colony (van Sittert 2002), where long-established and

settled districts such as Graaff-Reinet (78 per cent), Cradock (79 per

cent) and Colesberg (90 per cent) were almost completely enclosed

by 1911. Districts such as Middelburg (75 per cent), Philipstown (72

per cent) and Hope Town (82 per cent) were not far behind, and in

some cases even overtook their predecessors. The more remote and less

densely populated districts such as Namaqualand and Kenhardt were

much slower to follow: both were still less than 1 per cent enclosed by

1911. The proclamation of the Fencing Act (No. 30 1883) spread the

practice steadily across the Karoo and, as can be seen in figures 13–

16, fencing flourished first in the older, more densely settled eastern

districts, only spreading very gradually into the lower-rainfall districts

of the interior where population densities were lower, farms larger and

farming methods more extensive.

While the eastern districts were increasingly covered with a ‘network

of wire fences’ that, despite not enclosing all available land, effectively

prevented the invasion of trekbokke into these better-watered areas, the

Achterveld remained relatively unenclosed. Between 1904 and 1911,

however, key districts such as Calvinia, Fraserburg and Carnarvon

increased the area fenced by 54 per cent, 61 per cent and 68 per cent

respectively. Ultimately, between 1891 and 1911, ‘the fertile brain and

inventive power of man’ invoked by the Victoria West Messenger in

1880 (Victoria West Messenger 4 October 1880) had triumphed and the

http://journals.cambridge.org Downloaded: 30 Aug 2013 IP address: 137.158.158.60

178 THE END OF SPRINGBOK TREKS

FIGURE 14 Extent of enclosure, 1891

FIGURE 15 Extent of enclosure, 1904

http://journals.cambridge.org Downloaded: 30 Aug 2013 IP address: 137.158.158.60

THE END OF SPRINGBOK TREKS 179

FIGURE 16 Extent of enclosure, 1911

‘gigantic scheme’ of fencing the perimeter of every farm began to gain

momentum.

Skinner’s original contention (1993) that fencing began only twenty

years after treks had already ceased is patently incorrect. Instead the

opportunistic movement of springbok in response to rain, integral to

both population fluctuations and treks, was significantly curtailed. The

trek overflow areas of the better-watered eastern Karoo districts were

the first to be enclosed by a moving wire fencing front advancing

gradually westward. The increasing fencing out of springbok from the

districts of Hopetown, Philipstown, De Aar, Hanover and Colesberg

by the mid-1890s resulted in the build-up and concentration of trekbok

numbers in the unenclosed triangle between the towns of Britstown,

Vosburg and Victoria West in 1896. Exacerbating this cul-de-sac was

the effect of drought in the districts to the north, south and west,

suggesting that the natural mortality of the 1896 trek was considerably

higher than in earlier, more dispersed, mass movements.

‘DE KLACHT VAN DEN DAG IS DER VERSCHRIKKELYKE DROOGTE’ – THE TWIN

EFFECTS OF DROUGHT AND HUNTING, 1895–1908

Perhaps the most important impact on the 1896/7 trek was hunting.

The unnatural concentration of springbok in the Britstown-Vosburg-

Victoria West triangle allowed for a more focused and sustained

http://journals.cambridge.org Downloaded: 30 Aug 2013 IP address: 137.158.158.60

180 THE END OF SPRINGBOK TREKS

FIGURE 17 Percentage variation of annual rainfall in the Achterveld, 1889–

19085

exploitation, and ultimately decimation, of the trekbokke. Whereas

earlier ‘mega-treks’ such as those of 1861–2, 1872–3, 1877–8 and

1880 had followed the same pattern and build-up as that of 1896–7,

their movements were far less restricted. The result of this was that

concentrations were not as marked or as prolonged, and the human-

induced impact on mortality therefore significantly less, permitting the

natural ‘boom and bust’ springbok population cycle to continue in

subsequent years (Roche 2004: 72–109).

The effects of both prolonged hunting and drought on the 1896/7

trek (Roche 2004: 110–54) produced an unprecedented mortality of

trekbokke. The continuing drought of 1897 and 1898 only exacerbated

the initial impact and ensured that there was no immediate recovery in

the population. Rather, instead of an expected wet cycle, the wet years

of 1899–1901 gave way to a decade that, with the exception of 1907,

was significantly drier than even the mid-1890s (see Figure 17). With

the exception of a few districts in 1904 and 1907, for example, rainfall

received across the Karoo during this period was dramatically below

average and in harsh contrast to the above average years 1889 to 1895

and 1899 to 1901.

In Upington during 1903 ‘de klacht van den dag [was] der

verschrikkelyke droogte’ (Victoria West Messenger 16 October 1903) (‘the

complaint of the day was the terrible drought’) and the same was true of

most of the districts south of the Orange River. Complaints of drought

in districts such as Kenhardt and Prieska filled the local press (see,

for example: Victoria West Messenger 24 February 1905; Cape Archives

Depot 1902–3) and in Beaufort West the proverbial ‘oldest farmers

in the district’ held that it was ‘by far the severest drought that has

been known here’ (Courier 26 March 1903). By July 1903 Kenhardt

http://journals.cambridge.org Downloaded: 30 Aug 2013 IP address: 137.158.158.60

THE END OF SPRINGBOK TREKS 181

was described as devoid of people or stock, the inhabitants having

trekked north of the Orange River in search of pasture (Courier 23 July

1903). By year’s end it was accepted that the districts worst affected

were Fraserburg, Carnarvon, Victoria West and Beaufort West (Courier

19 November 1903). Public prayers for rain were held in Beaufort

West in early 1904 (Courier 7 January 1904) and although the drought

conditions in the interior lifted somewhat during 1904 and 1905 (see

Figure 17), as a result of exhausted local grazing the trekboere (migrating

farmers) of the Fraserburg district were said to ‘rond maal soo’s spring-

bokke, en weet ni waarheen ni’ (Victoria West Messenger 24 February

1905) (‘mill around like springbok and not know what direction to go

in’). Even in the regions of much higher rainfall such as Graaff-Reinet,

the drought took its toll, and as a result even the local springbok, which

were known as a species to be more drought-resistant that domestic

stock, were ‘so ma’er [thin] that they die easily from fright’ (Victoria

West Messenger 20 May 1905) and hundreds reportedly perished during

the drought (Graaff Reinet Advertiser 28 June 1905). By 1908 the

persistent drought led to widespread speculation that ‘South Africa

[was] becoming parched up’ due to the ‘decreasing African rainfall’

(Victoria West Messenger 6 February 1908; 13 August 1908).

This extended drought precluded a recovery in springbok numbers, a

fact borne out by the complete lack of reported treks during this period.

Hunting continued, of course. This was not on the scale of 1896, but

in the Achterveld surviving springbok were still regarded as vermin and

a threat to what was essentially a marginal agrarian economy under

massive pressure from drought (Victoria West Messenger 5 July 1906).

In addition to hunting organized either for sport or for vermin

extermination, springbok were also important as a source of protein

during both the 1899–1902 Anglo-Boer War (see Figure 18). Aside

from farmers embattled by the drought and forced to rely on

wild sources of protein such as springbok, Boer guerrillas operated

throughout the districts discussed here and themselves relied to a

large extent on what the veld could provide in the way of sustenance

(Constantine 1996: 20–44; 133–49; 165–75).

In Victoria West during 1903, to the great relief of the population,

the Game Law Amendment Act (No. 36 of 1886) was suspended, ‘not

so much to serve sportsmen, but to enable the poorer class to eke

out their meagre food supply with game’ (Victoria West Messenger 18

December 1903). The similar importance of springbok to households in

the Kenhardt district was noted the following year by a correspondent

of the Victoria West Messenger (18 November 1904), and even ostrich,

during the open season, were hunted for biltong and to protect the

pasture (Victoria West Messenger 27 September 1906). Kimberley,

although beyond the range of the trekbokke and a substantially larger

5

Annual rainfall figures are taken from Meteorological Commission data published in the

Statistical Register of the Cape of Good Hope. Average rainfall figures are obtained from

Union of South Africa 1927.

http://journals.cambridge.org Downloaded: 30 Aug 2013 IP address: 137.158.158.60

182 THE END OF SPRINGBOK TREKS

FIGURE 18 ‘Group of Boers beside a trestle table loaded with Springbok

carcasses.’ (Cape Archives Depot: AG 2221)

town than those within the Achterveld, serves as a vivid example of the

importance of ‘game’ to sustenance during this time. Accounts of life

on the diamond fields record how an industry developed to meet the

demand of the diggings for meat, ‘many men [spending] their morning

in the veld, shooting whatever they came across, and trekking towards

the diggings in the afternoon to sell what they shot on the early morning

market’ (McNish 1968: 261–2) and there is no doubt that this parallel

‘extractive industry’ was both burgeoning and profitable. In the 1904

hunting season, for example, 12,975 ‘head of game’, realizing £2,752,

were sold on the Kimberley market. In 1905 this figure was 29,119

at £4,667, and in 1906, 40,933 at £4,829. Springbok were not the

only target of market hunting, however, and in 1906 the composition

of the trade was: Springbok 4,025; Duiker 174; Steenbok 1,415;

Hares 5,131; Korhaan 3,565; Redwing Francolin 2,957; Guineafowl

818; Bustards 59; Wild Duck 130; Geese 33; small birds 22,626

(Horsbrugh 1912: 26).

In short, the twin effects of drought and hunting first ensured

abnormal mortality during the 1895–6 trek and then, together with

a range steadily shrunken by fencing and expanding permanent

settlement and agriculture, effectively prevented any recovery in the

population over the ensuing decade, thus accounting for the mass

mortality that precipitated the disappearance of springbok treks and

which previously has been ascribed to rinderpest.

http://journals.cambridge.org Downloaded: 30 Aug 2013 IP address: 137.158.158.60

THE END OF SPRINGBOK TREKS 183

CONCLUSIONS

That springbok treks in the Karoo ended with the 1896–7 trek is

obvious and indisputable. A modern ecological understanding of the

cyclical and nomadic pattern of these treks helps to make it equally clear

that the replacement of this phenomenon with sedentary small stock

farming has had a dramatic impact on the ecological state of the Karoo.

Previously the abrupt end of the springbok treks has been attributed

directly to the rinderpest epidemic that swept through southern Africa

at roughly the same time. It is apparent, however, that the closeness

in time of the two events is purely coincidental and that rinderpest

had little or no influence on the Karoo springbok population and the

trekbok phenomenon. This is clear for a number of reasons. First, the

two events did not coincide exactly, with at least four months between

the dispersal of the trekbokke and the arrival of rinderpest in any of

the Karoo districts affected in 1897. Second, the spatial overlap of

the trekbok movements in 1897 and the path of infection taken by

rinderpest is not convincing. Third, given that colonial farmers were

obsessive about disease in their stock and the role wild game played

as a reservoir and transmitter of such disease, the fact that there is no

contemporary report of rinderpest in springbok (in most cases the only

large wild mammal surviving in any appreciable number) is persuasive

evidence that springbok did not in fact suffer dramatic impact from the

disease, if indeed it affected the population at all.

It is important, however, to discern the causes of the obvious

demise of the trekbok phenomenon in such an abrupt and absolute

fashion. First, it is clear that the advent of widespread settlement of

the Karoo during the last quarter of the nineteenth century exerted

considerable pressure on natural resources, including local extinctions

of large mammal species and subspecies. Increasing enclosure through

wire fencing, the establishment of villages, towns and permanent farm

settlements, and the growing human and livestock population densities

began the process of circumscribing springbok treks. Increased

competition for space, the introduction of a new super predator in

the form of colonial man and his firearms, the need for protein in a

growing human population and the perception amongst farmers that

springbok and livestock competed for forage drove a decline in the

overall springbok population.

Crowding out of the springbok was gradual at first, but increasingly

access of the trekbokke from the Achterveld to the higher-rainfall

districts of the eastern Karoo was restricted. Initially this resulted

in ever more concentrated treks as springbok were forced to gather

in bottlenecks of good unenclosed grazing surrounded by established

farmland and towns. The process had been noted by Scully in

explaining the destructive impact of the 1892 trek in Namaqualand:

‘as the area over which the bucks range becomes more and more

circumscribed, the trek, although the numbers of bucks is rapidly

diminishing, becomes more and more destructive owing to its greater

concentration’ (Scully 1898: 104–5). The highly concentrated nature

http://journals.cambridge.org Downloaded: 30 Aug 2013 IP address: 137.158.158.60

184 THE END OF SPRINGBOK TREKS

of the springbok treks combined with dramatically increased resident

human populations and the infrastructure in the form of rail links

meant that springbok mortality was enormous, with large numbers

being commercially harvested and others shot for sport. This increasing

mortality culminated in 1896 when the trekbokke spent the bulk of

the year focused on the area around Vosburg – a cul-de-sac caused

by colonial expansion (a significant aspect of which was fencing) and

drought, and which resulted in an unusually concentrated, sustained

and severe impact on pasture. Abnormal mortalities followed, and,

combined with the devastating impacts of equally unprecedented

hunting, effectively reduced the trekbokke to numbers below a

population threshold from which early recovery was possible.

There is no doubt, therefore, that the unprecedented number of

springbok killed during this time, enabled by the factors described

above, dealt a mortal blow to the overall springbok population of the

Karoo and thus the ability of this population to recover.

While hunting might have been the proximate cause of the demise of

the springbok treks, recovery of the overall springbok population and

the re-establishment of the trek phenomenon in the decade after 1897

was prevented by ever-increasing enclosure, a severe and prolonged

drought and continued hunting of the surviving springbok. Hence, not

only was the overall springbok population decimated but the conditions

essential for the maintenance of treks were destroyed, thus ensuring the

extinction of a unique phenomenon.

Skinner and Louw’s conclusion that rinderpest was the main cause

of the demise of the springbok treks is thus clearly wrong, the disease

playing little or no role in the 1896–7 trek or in springbok mortality

in the years thereafter. In much the same way as an amalgam of

environmental and anthropogenic factors are considered to have caused

the destruction of the bison (Isenberg 2000: 123–63), the end of

springbok treks in the Karoo can instead be attributed to a complex

combination of factors including the increase in livestock and human

populations, the spread of fencing and increasing enclosure, drought

and hunting. The combined effect of all these factors ensured that the

conditions necessary to sustain cyclical springbok treks in the Karoo

were completely eroded and the advent of the Game Law Amendment

Act No. 11 in August 1908, for all its good intentions to include the

trekbokke as ‘game’, was a clear case of closing the stable door after the

horse had bolted.

The impact of the disappearance of springbok treks and replacement

thereof with livestock and human settlement must be seen from two

perspectives. In the first case the trekbokke ceased to exist because the

ecosystem and conditions needed to sustain such enormous population

growth and movement ceased to exist. In the second case the removal

from the ecosystem of such an important component must have had

far-reaching consequences which at this stage are unfathomable. Both

perspectives hint at the massive anthropogenic impact on the Karoo.

The replacement of a system of irruption and nomadism adapted to

Karoo fluctuations with a static and artificially manipulated one that

http://journals.cambridge.org Downloaded: 30 Aug 2013 IP address: 137.158.158.60

THE END OF SPRINGBOK TREKS 185

sought to overcome Karoo ecological cycles, rather than to respond to

them, has resulted in the continuing degradation of Karoo pasture.

REFERENCES

Acocks, J. P. H. (1953) ‘Veld types of South Africa’, Memoirs of the Botanical

Survey of South Africa 28: 1–92.

Anon (1895) ‘Scab in springbucks’, Agricultural Journal of the Cape of Good

Hope 8 (5): 113–18.

—— (1897) ‘Agriculture: reports and prospects’, Agricultural Journal of the

Cape of Good Hope 10 (13): 729–31.

—— (1898a) ‘Agriculture: reports and prospects’, Agricultural Journal of

the Cape of Good Hope 13 (5): 237–43.

—— (1898b) ‘Agriculture: reports and prospects’, Agricultural Journal of the

Cape of Good Hope 13 (6): 301–10.

—— (1898c) ‘Agriculture: reports and prospects’, Agricultural Journal of

the Cape of Good Hope 13 (9): 493–502.

—— (1899) ‘Agriculture: report and prospects’, Agricultural Journal of the Cape

of Good Hope 14 (8): 477–80.

Beinart, W. (2003) The Rise of Conservation in South Africa: settlers, livestock and

the environment 1770–1950. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Bengis, R. G., R. Grant and V. de Vos (2003) ‘Wildlife diseases and veterinary

controls: a savanna ecosystem perspective’ in J. T. du Toit, K. H. Rogers and

H. C. Biggs (eds), The Kruger Experience: ecology and management of savanna

heterogeneity. Washington DC: Island Press.

Bryden, H. A. (1889) Kloof and Karoo: sport, legend and natural history in Cape

Colony with a notice of the game birds and of the present distribution of the

antelopes and larger game. London: Longmans Green.

Cape Archives Depot (1902–3) ‘Kenhardt distress’. CO 7750, 1810.

Cape Archives Depot (no date) ‘Anglo-Boer War. Group of Boers beside a

trestle table loaded with Springbok carcasses. A covered wagon is in the

background.’ Photograph. AG 2221.

Cape of Good Hope (1866) Census of the Cape, 1865. G. 20.

—— (1867) ‘Report of the Select Committee appointed to consider and report

on the Game Laws Bill’. A. 9.

—— (1876) Census of the Cape, 1875. G. 42.

—— (1892) Census of the Cape, 1891. G. 6.

—— (1898) ‘Statistical Register: Livestock enumeration’.

—— (1905) Results of a Census of the Colony of the Cape of Good Hope, 1904.

G. 19.

Christopher, A. J. (1976). Southern Africa. Folkestone: Dawson.

Constantine, R. J. (1996) ‘The Guerilla War in the Cape Colony during the

South African War of 1899–1902: a case study of the republican and rebel

commando movement’. Unpublished MA thesis, University of Cape Town.

Cronwright-Schreiner, S. C. [1899] (1925) ‘The “trekbokke” (migratory

springbucks); and the “trek” of 1896’, The Zoologist, reprinted in

S. C. Cronwright-Schreiner, The Migratory Springbucks of South Africa (the

Trekbokke): also an essay on the ostrich and a letter descriptive of the Zambezi

Falls. London: Hamilton, Adams.

Davies, R. A. G. and J. D. Skinner (1986a) ‘Spatial utilization of an enclosed

area of the Karoo by springbok Antidorcas marsupialis and merino sheep Ovis

aries during drought’, Transactions of the Royal Society of South Africa 46:

115–32.

http://journals.cambridge.org Downloaded: 30 Aug 2013 IP address: 137.158.158.60

186 THE END OF SPRINGBOK TREKS

—— (1986b) ‘Temporal activity patterns of springbok Antidorcas marsupialis

and merino sheep Ovis aries during a Karoo drought’, Transactions of the

Royal Society of South Africa 46: 133–47.

Davies, R. A. G., P. Botha and J. D. Skinner (1986) ‘Diet selected by springbok

Antidorcas marsupialis and merino sheep Ovis aries during a Karoo drought’,

Transactions of the Royal Society of South Africa 46: 165–76.

Davies, S. J. J. F. (1984) ‘Nomadism as a response to desert conditions in

Australia’, Journal of Arid Environments 7: 183–95.

Dean, W. R. J. and I. A. W. MacDonald (1994) ‘Historical changes in

stocking rates of domestic livestock as a measure of semi-arid and arid

rangeland degradation in the Cape Province, South Africa’, Journal of Arid

Environments 26: 281–98.

Dean, W. R. J. and S. J. Milton (2001) ‘Responses of birds to rainfall and

seed abundance in the southern Karoo, South Africa’, Journal of Arid

Environments 47: 101–21.

Dean, W. R. J. and C. J. Roche (2007) ‘Are historical references appropriate

restoration targets for changed habitats in the semi-arid Karoo, South

Africa?’ in S. J. Milton and J. Aronson (eds), Restoring Natural Capital 1:

developing countries of the south. Washington DC: Island Press.

Dean, W. R. J. and W. R. Siegfried (1997) ‘The protection of endemic and

nomadic avian diversity in the Karoo, South Africa’, South African Journal of

Wildlife Research 27: 11–21.

Gilfoyle, D. (2002) ‘Veterinary Science and Public Policy at the Cape Colony,

1877–1910’. Unpublished D.Phil thesis, University of Oxford.

—— (2003) ‘Veterinary research and the African rinderpest epizootic: the Cape

Colony, 1896–1898’, Journal of Southern African Studies 29 (1): 133–54.

Green, L. G. (1955) Karoo. Cape Town: Howard Timmins.

Henning, M. W. (1956) Animal Diseases in South Africa: being an account of the

infectious diseases of domestic animals. South Africa: Central News Agency.

Hoffman, M. T. and R. M. Cowling (1990) ‘Vegetation change in the semi-

arid Karoo over the last 200 years: an expanding Karoo – fact or fiction?’,

South African Journal of Science 86: 286–94.

Horsbrugh, B. (1912) The Game-birds and Waterfowl of South Africa. London:

Witherby and Co.

Hutton, C. W. (ed.) (1887) The Autobiography of the Late Sir Andries

Stockenstrom. Cape Town: J. C. Juta and Co.

Isenberg, A. C. (2000) The Destruction of the Bison: an environmental history,

1750–1920. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Jacobs, N. (2002) ‘The colonial ecological revolution in South Africa: the case

of Kuruman’ in S. Dovers, R. Edgecombe and W. Guest (eds), South Africa’s

Environmental History: cases and comparisons. Cape Town: David Philip.

MacKenzie, J. M. (1988) The Empire of Nature: hunting, conservation and British

imperialism. New York: Manchester University Press.

McNish, J. T. (1968) The Road to El Dorado. Cape Town: C. Struik.

Milton, S. J., R. A. G. Davies and G. I. H. Kerley (1999) ‘Population level

dynamics’ in W. R. J. Dean and S. J. Milton (eds), The Karoo: ecological

patterns and processes. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Nell, D. D. (1998) ‘ “You Cannot Make the People Scientific by Act of

Parliament”: farmers, the state, and livestock enumeration in the north-

western Cape, c. 1850–1900’. Unpublished MA thesis, University of Cape

Town.

Phoofolo, P. (1993) ‘Epidemics and revolutions: the rinderpest epidemic in

late-nineteenth century South Africa’, Past and Present 138: 112–43.

http://journals.cambridge.org Downloaded: 30 Aug 2013 IP address: 137.158.158.60

THE END OF SPRINGBOK TREKS 187

—— (2004) ‘Zafa! Kwahlwa! Kwasa! African responses to the rinderpest

epizootic in the Transkeian territories, 1897–8’, Kronos 30: 94–117.

Pringle, J. A. (1982) The Conservationists and the Killers. Cape Town: T. V.

Bulpin and Books of Africa.

Roche, C. (2003) ‘ “Fighting their battles o’er again”: the springbok hunt in

Graaff-Reinet, 1860–1908’, Kronos 29: 86–108.

—— (2004) ‘ “Ornaments of the Desert”: springbok treks in the Cape Colony,

1774–1908’. Unpublished MA thesis, University of Cape Town.

—— (2005) “The springbok . . . drink the rain’s blood”: indigenous knowledge

and its use in environmental history – the case of the /Xam and an

understanding of springbok treks’, South African Historical Journal 53: 1–22.

Scully, W. C. (1898) Between Sun and Sand: a tale of an African desert. Cape

Town: Juta.

Shaw, J. (1875) ‘On the changes going on in the vegetation of S. A. through the

introduction of the Merino sheep’, Journal of the Linnean Society 14: 202–8.

Skinner, J. D. (1993) ‘Springbok (Antidorcas marsupialis) treks’, Transactions of

the Royal Society of South Africa 48: 291–305.

Skinner, J. D. and G. N. Louw (1996) The Springbok: Antidorcas marsupialis

(Zimmermann, 1780). Pretoria: Transvaal Museum.