Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Howard 2010 Triangulating Debates Within The Field Teaching International Relations Research Methodology

Uploaded by

VGOOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Howard 2010 Triangulating Debates Within The Field Teaching International Relations Research Methodology

Uploaded by

VGOCopyright:

Available Formats

Triangulating Debates Within the Field: Teaching International Relations Research

Methodology

Author(s): Peter Howard

Source: International Studies Perspectives , November 2010, Vol. 11, No. 4 (November

2010), pp. 393-408

Published by: Oxford University Press

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/44218697

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

Oxford University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to

International Studies Perspectives

This content downloaded from

98.7.4.89 on Mon, 22 May 2023 16:58:02 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

International Studies Perspectives (2010) 11, 393-408.

Triangulating Debates Within the Field:

Teaching International Relations Research

Methodology

Peter Howard1

American University

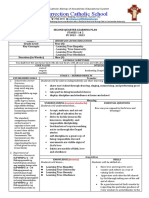

Undergraduate introductory methods courses offer a unique opportu-

nity to bring methodological pluralism to the field by teaching students

multiple approaches to research. This article presents one way to orga-

nize an introductory undergraduate research methods course. By focus-

ing on central debates between methodological approaches on issues of

causality, context, and essentialism, an instructor can introduce positiv-

ism, interpretivism, and relationalism as distinct, coherent methodologi-

cal approaches to research. Depicting these three debates and three

approaches graphically on a triangle can illuminate some core method-

ological debates within the field today. It also illuminates the methodo-

logical underpinnings of many of the discipline's theoretical debates.

Keywords: teaching, methodology, relationalism, interpretiv-

ism, positivism

While the "high politics" of methodological debates within the field play out in

the pages of top journals, the "low politics" of methodological debates reside in

the curriculum design of introductory undergraduate methods courses. These

courses serve as critical junctures in the education of both future scholars and

the much wider group of future readers of scholarship, where students learn

how to discern, evaluate, and construct knowledge claims, evidence-based argu-

ments, and methodologically sound work. However, a generic version of this

course, using a generic textbook as its guide, typically presents a very narrow pic-

ture of both the discipline of international relations and contemporary social sci-

ence methodology. Given calls for expanding methodological pluralism within

the discipline (Monroe 2005), it is important to introduce students to different

ways scholars are presently doing research without a priori privileging one over

the other. Such an approach accomplishes two important pedagogical goals:

equipping students to critically read, evaluate, and appreciate scholarship from a

range of methodological approaches, and empowering students to locate them-

selves in a particular methodological camp so that they may then learn to

Author's note : Special thanks are due to all of the students in my Introduction to International Relations

Research classes at American University's School of International Service for whom this triangle was developed. An

earlier version of this paper was presented at the 2007 annual meeting of the International Studies Association

Northeast. The views expressed in this article are my own and do not necessarily represent those of the US govern-

ment.

^eter Howard is currently an AAAS Science and Technology Policy Fellow at the US Departmen

is also an adjunct assistant professor in the School of International Service at American University.

doi: 10.1111/j.l528-3585.2010.00413.x

© 2010 International Studies Association

This content downloaded from

98.7.4.89 on Mon, 22 May 2023 16:58:02 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

394 Tńangulating Debates Within the Field

produce coherent scholarship. Students are empowered by learning the to

language, and skills to ask questions and design research projects consistent w

their philosophical approach to knowledge. Making these implicit commitmen

to knowledge explicit allows students to develop an understanding of t

possibilities as well as limits of their chosen approach to research.

As Schwartz-Shae and Yanow (2002) observe, "an exclusive emphasis on p

tivist epistemology limits students' capacity for questioning what is worthwhil

know - with a consequent skewing (or even stultifying) effect on the kinds

research questions students learn to pose. Or, it leaves those asking such ques

tions in a weak position absent philosophical and methodological arguments t

support their case." This is the story of one attempt to enact these goals in

classroom - the syllabus of my undergraduate Introduction to International Re

tions Research course. In that course, I teach three major approaches t

research methodology within contemporary international relations in relation

one another, as if in a sustained scholarly conversation that illuminates impo

tant debates within the field. This approach offers a different way to introd

students to methodology in a way that is intended to both better serve studen

and better serve the long-term health of the field that some of these studen

may eventually join.

In introducing approaches to research methodology, it is important to reca

that we as scholars typically define "research" as the production of "knowledg

Any discussion of different approaches to research draws on longstanding deb

in ontology and epistemology - what we can know about the world and how

can know it. The goal of methodology is not to resolve these intellectually p

debates, but rather to start from a particular position and articulate what exa

"counts" as knowledge, how claims about that knowledge are arbitrated, and w

one must demonstrate with evidence to produce knowledge.

Within a given methodological framework, then, various methods can be d

cussed and those techniques of gathering information about the world ca

put into context of the methodologies they serve. Some methods can be used

different ways to make different points, depending on the methodolo

employed. For example, archival research is a well-established method in inte

national relations research. However, archival documents can be used by

number of scholars in a number of ways in service of a number of differen

methodologies. An archival record could be part of a process-tracing of a

foreign policy decision, it could be part of a case study that tests a hypothesis

it could be an example of a discourse to analyze (George and McKeown 1

Van Evera 1997; Hansen 2006). It does not mean that archival work must serv

one or the other; rather, going to the archives is a method of research t

requires a methodology to tell the researcher how to make sense of the inform

tion - in this case the documents - found in the archives.

My approach is premised on the notion that in contemporary international

relations research there are three dominant methodological approaches to schol-

arship in the discipline. The ideal-type version of each methodology can be iden-

tified by its position on three debates. The debates allow us to "triangulate"

these three positions. Recall the way an ideal type works - no one researcher

actually takes these positions in a pure form, rather they approach them as a

function approaches a limit. We evaluate scholarship by holding it up to the

ideal, assessing its convergences and divergences, and understanding its relation-

ship to the ideal type (Weber 1968). To triangulate the position of each type

within the field, I will outline three debates. Each debate involves a two-step

discussion. First is a yes/no distinction between those willing to commit to the

position and those who are not. Second is a debate among members on

the "yes" side on how that position is defined. Three positions on each issue

are presented and illustrated graphically. When combined, they form a

This content downloaded from

98.7.4.89 on Mon, 22 May 2023 16:58:02 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Peter Howard 395

methodological triangle for in

useful as a pedagogical tool.

illuminates "research design

publications' ' (Skocpol 1994

The focus on research des

research starts with posing q

ent design for answering que

triangle when it is connect

assignment for the class, stu

produce three short research

odological camp identified o

methodological implications

each position. Using a comm

contrasting types of know

assignments allow students to

This triangle is meant to in

the discipline in the context

debates, multiple methodolog

not meant to argue for a rad

to open vast new areas of i

certain debates within the

certain methodological argu

logical positions within th

trouble within those alliances that one observes in the literature (Price and

Reus-Smit 1998; Sterling-Folker 2000; Barkin 2003). When paired with a very

basic theoretical map of the field, it reveals that many theoretical debates are as

much about methodology as they are about theory. It is also important to keep

in mind what this triangulation is not. It is not meant to be a definitive map of

the discipline, nor is it meant to create boxes in which scholars and research

programs may be placed. Moreover, it is not meant to be exclusive - other

approaches to introducing methodology can present a coherent picture of the

discipline in a compelling and enlightening way. It is designed primarily as peda-

gogical tool to help students better understand the fundamental commitments

of certain methodologies and the relationships between them.

To explain the development and use of this triangle in teaching research

methods, I will first discuss the three main debates that define the distinctions

between approaches to research and knowledge: causality, context, and essential-

ism. Next, I will articulate the ideal-type sketch of the three main methodologi-

cal types based on positions within those debates and provide a brief example of

how this plays out in one segment of the international relations literature. The

debates will be depicted graphically, on a triangular map of methodology in

international relations research. Finally, I will pair the methodological map with

a basic theoretical map of the field to further illuminate debates within interna-

tional relations.

The "Great Debates"

Causality

The first key debate concerns the status of causality. This remains a central fault-

line within the field, and many methodological texts only discuss this issue

(King, Keohane, and Verba 1994), ignoring the other two. The debate over

causality happens on two levels, illustrated graphically in Figure 1.

The first level of debate about causality pits those who reject the notion of

causality altogether against those who see a causality as central to any

This content downloaded from

98.7.4.89 on Mon, 22 May 2023 16:58:02 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

396 Triangulating Debates Within the Field,

General

causal forces

'

Causality

No Causality ' ''

Specific causal

processes /

mechanisms

Fig. 1. Causality

explanation of a phenomenon. Robert Keohane asserts that "making causal

inferences is the 'Holy Grail' of political science" (Keohane 2009) and exhorts

political scientists to seek causal factors that produce the outcomes we observe

in contemporary politics. This knowledge of causation thus unlocks explanation,

understanding, and recommendations. While, traditionally, a majority of the

members of the discipline agree with Keohane' s assertion, an increasing number

are challenging the role that causality plays in contemporary social science

inquiry.

Claiming that social life is too complicated and contingent, and aware that

the position of the researcher has significant influence on what is reported, it is

possible to reject causality as a relevant source of explanation in the social world.

From this perspective, social phenomena are not caused in any meaningful

sense; rather, they are interpreted or experienced by an author from a particular

position. Dunn, for example, remains "unconvinced that we can offer causal

explanations. The world is far too complex, complicated, and contingent to be

studied with any degree of certainty" (Dunn 2006). He instead follows Camp-

bell's (1993) "logic of interpretation that acknowledges the improbability of

cataloguing, calculating, and specifying 'real causes.'" This position of "no

causality" demands that a researcher focus only on the particular experience of

a phenomenon. Among those who appreciate and seek to understand causality,

then, there are two approaches to the phenomenon: that of general causation,

and that of particular causation (Parsons 2007).

The traditional definition of social science research is to provide explanations

of social phenomena. Within political science and international relations, many

have sought to define an acceptable explanation as a "causal law" (King et al.

1994; Van Evera 1997). Modeled after a basic understanding of causality in the

classical description of the "hard sciences" (physics, chemistry) originating with

thinkers such as Hume and Mill, the idea of causality assumes that a particular

and identifiable force acts on an entity to produce an observed outcome. Grav-

ity causes objects to fall. Imbalances of power cause states to go to war (Mears-

heimer 2001). The life-blood of social science research has long been a quest

to identify causal relationships of this sort. The key to this sort of causal argu-

ment is to be able to identify a causal force and to be able to correlate out-

This content downloaded from

98.7.4.89 on Mon, 22 May 2023 16:58:02 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Peter Howard 397

comes with the existence of th

that a scholar can generalize th

to produce parsimonious, gene

works that can be verified by oth

the mainstream, most widely acc

as defined by King, Keohane, and

1994). For undergraduate student

stand and reproduce in a researc

taught in high school science cla

makes a good starting point to in

Increasingly, a number of schol

generalizable causal laws in favor

(Tilly 1995). Here, causality is a p

in particular ways to produce an

somewhat generalizable, outcom

setting, and circumstance. Conte

in similar processes - variation t

dent of context. Causation move

specific interaction of actors

asking what causes war, a focu

caused a particular war, or rath

outbreak of the war in question

still seeks to uncover a cause for

''how" as "why" (Tilly 2006).

Context

The second key debate is over

(Figure 2). Dating back to the

allows for objectivity, there is

irrelevant when making claims a

objective, observable world that

researcher should be able to ob

objective world. The social con

role in this objective world becau

measured. Social context canno

are generalized, observable outc

ied and confirmed by any resear

as another observable and reprod

then is to produce an accurate re

izing findings is possible beca

independent of the researcher, n

specific.

Opposite this is the notion that

consequential to be broken int

social world, and in a social worl

mean to them. Consider Geert

description of the difference be

same observable behavior, an e

pointed at a particular person.

behavior, the point of a wink is

winkee. From a purely objective

ized is the raising and lowering

ciative of social context, the co

amusing wink all convey deep ye

This content downloaded from

98.7.4.89 on Mon, 22 May 2023 16:58:02 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

398 Tńangulating Debates Within the Field

in the moment. It is this context that makes the wink worth studying (an

worth doing). As an in-class example, it readily demonstrates value of under

standing context as students are quite familiar with the different contexts and

meanings associated with a wink. It also points out the importance of the con-

text of the researcher, as in-class discussion will quickly reveal a wide variety of

ways to make sense of the same wink based on past experience as either a win-

ker or winkee.

The question arises, however, as to the nature of social context: is meaning

wholly subjective, determined separately by each observer and ultimately open to

each observer's unique interpretation, or is meaning intersubjective, created by

shared understandings among actors as to how all make collective sense of an

experience? On the subjective side, meaning is strictly a function of position

and encounter. Each researcher will uncover a different meaning depending on

his or her position and access to a social structure. Because social contexts are

unique, they are not reproducible; rather, all one can do is attempt to under-

stand how a researcher made sense of, or 4 'read" a particular encounter.

Indeed, each encounter of researcher and subject is unique, emphasizing

' 'multiple representations or interpretations and the infinite number of ways in

which individuals or groups 'see' the world" (Fierke 2002). As Dunn (2006) says,

"I am interested in whether or not my conclusions make sense to me." Meaning

is thus fluid, and its interpretation is "absolutely" relative.

On the other hand, meaning may be understood as intersubjective - a series

of shared understandings that exist in use, be it a discourse, practice, or institu-

tional form. The more subjective orientation "tends to emphasize interpretation

and representation rather than rules" (Fierke 2002). From the intersubjective

position, meaning does not depend on what any one individual believes, rather,

meaning rests in what members of a group can share amongst themselves and

recognize as such. Social context is thus a set of shared rules. The interpretation

of a rule can only be taken so far - there is a way to grasp a rule that is not pure

interpretation - is one following the rule or not. From an intersubjective per-

spective, the social context is more plastic. It can be maintained as stable for a

sustained period, allowing complex social forms to develop, but it is not so rigid

as to resist change and the social practices that give rise to change. The more

who share a social context, the more work to change it. But because it is inter-

subjective, a social context can be easily studied, observed, and traced. It cannot

reside inside an individual's head, it must be shared, and again, the process of

sharing meaning must be participatory and therefore observable for study.

Indeed, meaning rests in this process of sharing, not with the actors who may

participate in this process.

Objective

(independent

of context)

Subjective Context - ■ ,ntersubjective

(unique to (shared

individual) understanding)

Fig. 2. Context

This content downloaded from

98.7.4.89 on Mon, 22 May 2023 16:58:02 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Peter Howard 399

Essentialism

The third key debate is over essentialism (Figure 3). This is perhaps the most

recent debate and most difficult to explain to undergraduates, but it is no less

significant. Those who make or rest on essentialist claims hold that actors in the

social world have clear, identifiable, unchanging essences. A state is... Bipolarity

is... The West is... The notion that there is such a thing as a state or bipolarity

or the West that can be identified with a core set of characteristics without which

it would not be itself is the hallmark of essentialism. Essentialism locates the

properties of an object within that object, and essences serve as the sta

point for inquiry.

Opposite the essentialists are those who argue that all social phenomena to

studied are processes, not things (Tilly 1995). "Instead of possessing a constit

essence , actors - whether states or individuals - should be regarded as the pr

of ongoing constitutive practices " (Jackson 2004b; emphasis original). The

posed 4 'essence' ' of an object at any particular point is thus the product of a

cess. At any one moment it may appear fixed, but that fixity is subjec

explanation. It is the job of the researcher to disassemble ' 'things' ' int

processes that create, maintain, and shape those social forms. The West is n

essential culture, rather, the West is an ongoing project to assert a connect

among certain core texts, ideas, history, and people. France is a set of proc

and practices to continually link an idea of nationhood to a particular

institutions, people, and territory. All of it could unfold differently, g

that such processes are contingent and not fixed (in any essential way). Hen

both stability and change are equally problematic and to be explained. C

requires an explanation of processes leading to different results, taking adv

tage of a particular contingency, while stasis requires an explanation of

particular processes were continually maintained and reproduced in the fac

contingency.

Essentialists differ on the nature of essence: are essential qualities material

and objective facts, or are they ideational and subjective items? Material, objec-

tive essences are posited to exist in actors or things such as States or Bipolarity

or the National Interest. "The State" is a fundamental unit of study in the field,

and it has identifiable interests that can be identified and measured. States exist

and persist, and it is the job of the researcher to most accurately represent their

essential nature. On the other side, items like culture or a foundational text

have an ideational, subjective essence. To claim that there is an "authentic"

local culture that best represents a traditional folkway is to essentialize both the

"real nature" of a culture and the items that threaten it by somehow distancing

it from its essential roots. Either way, essences serve as the starting point for

inquiry and are not the object of inquiry. Stasis is the assumed nature of things,

while change is to be problematized and explained.

Triangulation

When combined, these three debates allow for the triangulation of three ideal-

type methodological positions within contemporary international relations

research. It is important to keep in mind that these are ideal-types around which

it becomes possible to organize and map the literature of the field. I do not

assume that these ideal types represent the research of any particular scholar.

Rather, as scholars identify with one methodological camp or another, as defined

by these ideal types, they locate their research relative to the above debates.

A short description of each of the three approaches to research - the points

of the triangle - follows. Pedagogically, my syllabus is actually organized this way,

as it is easier to teach each methodology as a coherent approach. Moreover, it is

This content downloaded from

98.7.4.89 on Mon, 22 May 2023 16:58:02 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

400 Tńangulating Debates Within the Field

Objective

materialist

Essentialism

/

^ Anti-essentialist

S"bJectlvf ideational (processecual)

ideational

Fig. 3. Essentialism

necessary to support the research design assignments for the course. The course

unfolds in three sub-units, covering each methodological approach. Each

sub-unit concludes with a research design assignment, forcing students to think

through the requirements of research design for each approach and the practi-

cal consequences of those requirements in the research process. After a descrip-

tion of each approach, I provide an example of how I illustrate these differences

in class using the democratic peace debate.

Type 1: (Neo)Positivists

The (Neo)Positivists are those who subscribe to general causality, objective essen-

tialism, and reject the importance of social context. This ideal type is best articu-

lated by Waltz (1979) and later King et al. (1994), and remains the dominant

standard against which much research is evaluated. Again, though, keeping with

the notion of the ideal type, it is important to note that few researchers are fully

able to implement each and every one of King, Keohane, and Verba's dictums.

Rather, they try to approach this ideal, making necessary compromises as partic-

ular projects require. Take, for instance Van Evera's (1997) Guide to Methods for

Students of Political Science. It is intended as a guide, a cookbook almost, on how

to construct a qualitative case study dissertation. Van Evera continues to hold

King, Keohane, and Verba as the ideal, but instructs students on acceptable com-

promises deviating from the ideal in the name of practicality.

The goal of a (Neo) Positivist research design is to construct a project that

seeks to test a claim of cause and effect on an observable world to generate a

generalizable causal law about how the world works. The role of theory is to gen-

erate hypotheses, defined as statements positing a causal relationship between

independent and dependent variables, and test those hypotheses against

objective, real-world evidence. Successful research will produce evidence that

corresponds with the claims of the hypothesis, thus validating its causal claims.

Type 2: Interpretivist

The Interpretivists subscribe to the importance of subjective context, idea-

tional/subjective essences, but reject the notion of causality. For the interpretivist,

the goal of research is to uncover essential meanings of cultures, representations,

or discourses while recognizing that each articulation of meaning is totally and

incontrovertibly subjective. Each reading of the world is subjectively unique,

This content downloaded from

98.7.4.89 on Mon, 22 May 2023 16:58:02 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Peter Howard 401

depending on the position of the

research "self-consciously adopts

interpretation is as equally valid

terms and makes sense to the int

is impossible for any two people

same position. This subjectivity r

of themselves - the merit lies in

uncovering the "political consequ

over another" (Campbell 1993).

An interpretivist research des

read an aspect of politics and rep

encounter, identifying what key

form, it is a wholly subjective en

own merits. This may take the fo

struction. Regardless, the end pr

of the position of the researcher

Type 3: Relational

The third approach requires brin

tional relations methodological le

new label that is not yet widely u

tional sociology (Emirbayer 1997

relations scholarship (Nexon 20

that is home to a variety of theo

Nexon 2009).

A relational approach rejects essentialism, focuses on the specifics of causal

processes and the intersubjective nature and importance of social context. The

processes that form "things" are indeed causal and produce an intersubjective

understanding among those involved that can lead to particular outcomes in

contingent situations. The stuff of politics is intersubjective understandings

shared over a network of actors. This network, however, is not a network of wires

and routers, rather it is a social network of social ties and social communication.

These social ties are processes themselves, causal mechanisms that create or

maintain a network. The stuff of those social processes is the intersubjective

meaning making sense of the world. Social context exists in the relationships

actors have with each other. Relational approaches study relations before states

(Jackson and Nexon 1999).

A relational research design seeks to identify either the constitution of inter-

subjective understandings and social networks or the causal processes and mech-

anisms that create, maintain, and change those items. Both can be seen as two

sides of the same coin - processes of relating create relationships that can be

described as a network, processes of discourse create intersubjective understand-

ings - but a researcher must start somewhere, and often analytically brackets one

side to investigate the second. The result of this research is an account of how a

particular, contingent configuration of social processes come together to pro-

duce a recognizable, meaningful result. "What is generalizable from an account

such as this is not a specific set of nomethetic generalizations, but a 'toolkit' of

analytical devices which might be used to analyze similar situations" (Jackson

2002).

Example

There are numerous examples and exemplar pieces of scholarship for each

approach. When crafting a syllabus, providing many examples of exemplar

This content downloaded from

98.7.4.89 on Mon, 22 May 2023 16:58:02 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

402 Tńangulating Debates Within the Field

scholarship is necessary to give students a tangible understanding of

engage in research from each approach. However, I have found it also us

provide examples of each approach to research on similar topics. By s

different ways of looking at a similar empirical puzzle, students can

implications of each research perspective on both the type of questio

project proposed, and analysis offered. The democratic peace debate p

one such site.

There is a substantial amount of (Neo) Positivist research on the democratic

peace, most relying on statistical analysis to identify a causal relationship

between regime type and conflict. I have found one early debate in the litera-

ture, between Maoz and Russett (1993) and Färber and Gowa (1995), particu-

larly useful. Maoz and Russett were among the first to offer and test a set of

hypotheses on the causes of the democratic peace. Färber and Gowa dispute

their findings, and thus challenge the democratic peace hypothesis. These two

articles engage each other directly, and use the same data source to test rival

hypotheses. The core of this particular dispute produces a discussion of the

importance of how a researcher operationalizes a variable and the sample size of

the test data. When taught together, the two articles provide a solid example of

how (Neo) Positivist research is conducted across the discipline to test a hypothe-

sis with objective data to produce cumulative knowledge about concepts such as

the democratic peace.

From the interpretive perspective, Ido Oren (1995) offers a trenchant and

powerful criticism of this debate. He argues that a claim about democracies is

value-laden, not objective and value-free, and the product of the American social

context in which the scholarship was produced. I often introduce this article by

asking students to define democracy - framing the question as who counts as a

democracy in the world today. As students debate democracy, they soon see the

subjective elements of the definitional debate. Once the class has a working defi-

nition, I then ask when the US became a democracy by that standard. The

answer is often sometime in the early to mid-twentieth century, and yet the US

is often classified as a democracy from the founding of the republic. As Oren

demonstrates, by interpreting the definition of democracy relative to a contem-

porary American standard, and yet not applying these standards in a uniform

trarishistorical fashion when coding data, the democratic peace argument is

really a peace among states understood to be "like us." Through a detailed

discussion of prominent early political scientists' views of Germany before and

after World War I, Oren shows that as Americans reinterpret which states they

most admire, they reinterpret the essential elements and meaning of democracy.

Colin Kahl (1999) offers an early relational approach to his analysis of the

democratic peace. While Kahl wrote before the widespread use of the relational

label, his argument nevertheless makes use of relational approaches. Kahl

(1999) explicitly positions himself between the "hard" positivists and the

"extreme form" of interpretivism, making an early case for a relational

approach to the democratic peace. He identifies a collective liberal identity as

the mechanism that produces peaceful relationships among those states who

share the set of liberal intersubjective understandings he describes. Kahl's focus

on the democratic peace as an intersubjective process of sharing an identity

based on the meaning of democracy in a particular social context, rather than

an objective, essential quality of a particular regime type differentiates him from

the (Neo) Positivists. His focus on the causal mechanisms generated by intersub-

jective understandings separates him from interpretivists. The process of creating

a shared understanding among states can generate international outcomes. Kahl

illustrates how he is not simply splitting the difference between these two

positions, but rather attempting to construct a coherent third approach to the

democratic peace debate.

This content downloaded from

98.7.4.89 on Mon, 22 May 2023 16:58:02 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Peter Howard 403

This typology of the three id

angle below (Figure 4) which

(Figures 1-3):

The points of the triangle are the ideal type positions of the three major

research methodologies in international relations today. The legs of the triangle

are the three main debate issues from above. The midpoint of each leg repre-

sents the limit or break between the two ways to view the issue. The altitudes of

the triangle are the rejectionist positions. Thus, the (Neo)Positivists, at the top,

are on the general causal and objective material essentialism sides of the causal-

ity and essentialist legs. They discount the role of social context, and thus are

opposite the context leg, as indicated by the altitude from the context leg to the

(Neo) Positivist point. Interpretivists, in the lower left, are on the side of subjec-

tive meaning of context and subjective, ideational essentialism while rejecting

the importance of causality. Relationalism, on the lower right, is on the side of

causal processes, intersubjective meaning to context and anti-essentialism.

Again, the points of the triangle represent ideal types in this methodological

map. Few scholars do actual research and design actual projects from those

points. Rather, individual researchers make pragmatic and practical compro-

mises that have them slide down the legs, toward the center of the triangle in

the practice of research and scholarship. Qualitative case study research, for

example, brings the importance of contextual accounts or more specific causal

processes to bear as explanations. However, a researcher can only slide so far

down the leg - the midpoint of the leg acts as a limit, the point at which one

must switch a fundamental conviction about how the world works.

Along those lines, it is possible to consider an inscribed circle resting in the

triangle. This circle becomes an area of incompatible assumptions. It is, in a

sense, an argument against complete methodological eclecticism because to

(Neo)Positivist

Method

Material / ' Generalizable causal

essence / ' forces

.£ /

.$y v 'QQ^

W. ^

4¡f r

Ideational / ' Specific causal

essence / ' processes and

/ ' mechanisms

Interpretive ¿s' ^ ^ Relational

Method Subjective COHtCXt Intersubjective Method

meaning understanding

Fig. 4. Triangulating Debates

This content downloaded from

98.7.4.89 on Mon, 22 May 2023 16:58:02 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

404 Tńangulating Debates Within the Field

occupy a position in that circle is to hold fundamentally incompatible as

tions about the world. Either there is an objective reality or there is not

concede that one side dominates over the other has profound implication

the ultimate importance and relevance of meaning and generalization

social world. There either are essences of actors or there are not, to have an

actor be half essence, half process is to concede one side of the debate. While it

is possible to come toward the center of the triangle part-way (indeed, not just

possible, but required on some level), one must stay within the limits of one's

own position. The triangle requires commitment to one point or another.

Toward the end of the course, when presented with the triangle in full,

students learn two very important lessons about the way I am teaching them

research methodology. At the outset of the course, I tell them that they will love

one unit, hate one unit, and find a third unit plausible. They encounter a simi-

lar experience with the research design assignments - one is straightforward, one

is plausible, and one baffling. The first lesson is that there is a pre-analytic, per-

sonal decision to be made about why they come to embrace the positions they

do. It is a decision that they are capable of making. The approach that makes

the most sense does so for a reason: it resonates with how they make sense of

the world. I attempt to clarify this point repeatedly in class discussions. The sec-

ond lesson is that their particular choice does not matter - what matters is their

ability to recognize, articulate, and defend that choice and produce rigorous

research designs from their chosen methodological home. Solid research can

come from any approach if pursued rigorously. This moment is intended to be

empowering to students, as they locate themselves within the field and learn

how to design inquiries that they find both interesting and convincing.

Methodology and the Sociology of the Discipline

Toward the end of the class, after covering each of the three points of the triangle,

I attempt to illustrate the link between theory, method, and the sociology of

knowledge within the discipline. My triangle is somewhat reminiscent of Alker' s

triangle on international relations theory (Alker and Biersteker 1984). But, before

I complete the comparison, I want to clearly lay out the limits of what I am about

to argue: The theoretical map I propose is not meant to be definitive, and the

relationship between the two maps is one of general similarity, NOT a one-to-one

correspondence or any sort of isomorphism. Not all theorists from one theoretical

corner fit into the similar methodological corner. Rather, there is, to borrow the

Weberian term, an elective affinity between certain theories and certain methodol-

ogies. The general similarity is useful to illuminate the tension between theoreti-

cal camps and the types of debates they have with one another.

This theoretical triangle has its genesis in the Alker triangle of the early 1980s

where Alker divided the field into Realist, Liberal, and Radical/Marxist

approaches to international relations (Alker and Biersteker 1984). Alker's trian-

gle is reproduced in Figure 5.

In the 1990s, the shape of the Alker triangle changed. First, the distanc

between realist and liberal points shrunk considerably, resulting in the "ne

neo" consensus (Powell 1994; Waever 1996). Neorealists and Neoliberals argue

the finer points of relative vs. absolute gains but otherwise espoused rather sim

lar theories. While that happened, the radical line extended itself significantly

ultimately fracturing. Marxists largely disappeared with the end of the Cold War

and a whole host of new 4 'radicals" arose in their place. Constructivism emerged

as a new 4 'third pillar," creating a new "Big 3" theories of international rela-

tions (Walt 1998; Snyder 2004). At the same time, postmodernism (and several

other 4 'post" theories), along with critical theory emerged as the new "radical

ism," thereby creating a new trapezoid-triangle of realist/liberal, postmodern,

This content downloaded from

98.7.4.89 on Mon, 22 May 2023 16:58:02 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Peter Howard 405

Realism

Radicalism / Liberalism

Marxism

A

Fig. 5. Alker and Bierstecker's Triangle of Intern

1984)

and constructivist theories. Thus, the contemporary theoretical triangle is not

actually a nice, neat triangle, but a somewhat contrived trapezoid that at least

looks similar to a triangle from a certain distance (Figure 6).

Realism ■■■ Liberalism

(Neo-Neo consensus)

Post-Modernism Constructivism

(Neo) Positivist

Method

Material / ' Generalizable causal

essence / ' forces

// ' S

Jk'

Ideational ļ ' Specific causal

essence

Ī '

ļ ' processes and

mechanisms

Interpretive y ^ Relational

Method Subjective Con text intersubjective Method

meaning understanding

Fig. 6. Contemporary International Relations Theory and the Three Methodologies

This content downloaded from

98.7.4.89 on Mon, 22 May 2023 16:58:02 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

406 Tńangulating Debates Within the Field

Step back and consider the two triangles side by side, as shown in Figure 6.

reveals a distinct similarity between theory and method. The realists and liber

converge around (Neo) Positivism. The postmodernists occupy the interpretiv

position, and the constructivists occupy the corner for relational approach

Again, this is neither an isomorphic nor a one-to-one map. While many constru

tivists fit this relational framework, not all do - most notably Alex Wendt and

adoption of scientific realism as a way to be a constructivist and yet remain

the positivist side of the triangle. Post-structuralism fits somewhat uncomforta

on the bottom leg of the triangle, somewhere between interpretive and r

tional approaches. That said, the point of the comparison between the two trian

gles is not to pigeon-hole every theorist into a particular methodological cam

or vice versa. Rather, the comparison serves to illuminate some of the debate

within the field to students encountering them for the first time - so much

what passes for theoretical debate is in fact methodological debate.

This illustration provides one way to make sense of several alliances within th

field. Constructivists, critical theorists, and post-structuralists have mad

common stand against the neopositivism of liberals and realists which ignore

the social context they find so vital (Price and Reus-Smit 1998). Some constru

tivists and realists have attempted to make common cause over the study of

role and function of power (Barkin 2003; Jackson 2004a) while other constructi

ists and liberals share an appreciation of the power of liberal ideas to shape st

behavior (Sterling-Folker 2000). This triangle reveals that such theoreti

conversations and collaborations are potentially fruitful on certain comm

ground but also are limited by fundamental differences on a key issue.

For example, consider the challenge faced by feminist approaches to intern

tional relations theory. Much of the resistance to feminist research is justified

methodological, not substantive grounds. Consider Keohane's critique of femi-

nist scholarship in his exchange with Tickner (1995). Keohane's primary ch

lenge to feminists is a methodological critique on the issues of causality, from

clear (Neo) Positivist position on the triangle. Keohane asserts that proper soc

science methods investigate causality, and because the feminists in question d

not tell causal stories that generate testable hypotheses, they are not mak

significant contributions to the discipline. Tickner's response asserts the rele-

vance of the other legs of the triangle - feminist theory does have somethin

important to say, it just says it by employing a methodology that falls somewh

along the social context leg of the triangle. The triangle also illuminates the t

tical alliance between constructivist and postmodern feminists against critics li

Keohane. When juxtaposed with a traditional (Neo) Positivist, the relative agre

ment among feminists on the general importance of social context leads to an

ability to have a broad conversation about the importance of understandin

social context theoretically and a tactical alliance against those who deny a

relevance to any sort of context or meaning.

Toward the end of the term, I include a discussion on the sociology of t

discipline. While the triangle presents the three methodological approaches on

equal footing, a quick glance at the actual state of the discipline, whethe

program from the annual ISA meeting or a list of the articles in the top jour

nals or the dissertations deposited each year, reveals that in practice, scholar-

ship is unevenly distributed among the three approaches. Neopositivism s

dominates the field. However, the number of interpretive and relational scho

ars, papers, and publications is growing at a noticeable rate. This revelatio

however, serves as another teachable moment about the differences between

the three approaches and why they are not as balanced in practice as they

might be in theory. For the undergraduate new to the discipline, this discus-

sion serves two important purposes - one theirs and one mine. First, for the

students, it provides an explanation for what they will encounter as they

This content downloaded from

98.7.4.89 on Mon, 22 May 2023 16:58:02 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Peter Howard 407

continue their studies in the f

approaches are empowered to

of their position and that t

me, it helps realize the goal

making my students - future

ars, policymakers, and activ

field, I seek to encourage th

create a future where all th

ing field.

Conclusion

This triangle map of the three dominant research methodologies within interna

tional relations today illuminates many of the debates and alliances amo

methodological camps. It is not the only way to map methodologies in interna-

tional relations, but it is illuminating in ways that other maps are not, because

shows the fault lines between the approaches and presents each approach

equal footing, as one position in a tri-partite debate. It also allows one to emph

size the difference between methodology - how one organizes and makes sense

of information about how the world works - and method - particular techniqu

for gathering and processing information about the world. Methods - like inte

viewing, case studies, or computer-assisted quantitative analysis - can be usefu

for a multitude of methodologies, depending on how they are used. Interviews

can serve as data points to generalize relationships by gathering in-depth per-

sonal evidence, texts to deconstruct, or stories of causal processes and relation

ships. What matters, from this perspective, is less the way in which a researche

chooses to gather information, and more the way in which the research

chooses to organize and makes sense of that information to make a claim about

how the world works. As such, it provides an organizing logic for an introductor

class in international relations research.

My course explores all three approaches to research, presenting each on its own

merits, as if in a sustained scholarly conversation with other approaches. Doing so

does not inherendy privilege one approach as dominant, nor does it force stu-

dents into a particular track. Rather, it provides an opportunity for students to

learn each methodological approach on its own terms, understand its epistemo-

logica! and ontological commitments, and construct coherent research projects. I

ask them to design three research designs exploring a common topic, one from

each approach, forcing them to grapple with the practical side of identifying,

gathering, and making sense of data to support an argument. Most significantly, it

empowers students to determine how they come down on the three triangulating

questions and locate themselves on the methodological triangle. Finally, for future

scholars, this triangle helps to illuminate the stakes in making such choices in

international relations theory and international relations research.

References

Alker, H., and T. Biersteker. (1984) The Dialectics of World Order: Notes for a Future Archeolo

gist of International Savoir Faire. International Studies Quarterly 28(2): 121-142.

Barkin, J. S. (2003) Realist Constructivism. International Studies Review 5(3): 325-342.

Campbell, D. (1993) Politics Without Principle: Sovereignty, Ethics, and the Narratives of the Gulf War.

Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner Publishers.

Dunn, K. C. (2006) The Forum: Examining Historical Representations. International Studies Review

8(2): 370-381.

Emirbayer, M. (1997) Manifesto for a Relational Sociology. American Journal of Sociology 103(2): 281-

317.

This content downloaded from

98.7.4.89 on Mon, 22 May 2023 16:58:02 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

408 Tńangulating Debates Within the Field

Färber, H., and J. Gowa. (1995) Polities and Peace. International Secuńty 20(2): 123-146.

Fierke, K. (2002) Links Across the Abyss: Language and Logic in International Relations

tional Studies Quarterly 46(3): 331-354.

Geertz, C. (1973) Thick Description: Toward an Interpretive Theory of Culture. In The Inter

of Cultures. New York: Basic Books, Chapter 1, 3-30.

George, A., and T. McKeown. (1985) Case Studies and Theories of Organizational Deci

ing. In Advances in Information Processing in Organizations , edited by R. Coulam and R

Greenwich, CT: JAI Press. Vol. 2.

Hansen, L. (2006) Secuńty as Practice : Discourse Analysis and the Bosnian War. London: Routledg

Jackson, P. T. (2002) The West Is the Best: Occidentalism and Postwar German Reconstr

Constructivism and Comparative Politics , edited by D. Green. Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe.

Jackson, P. T. (2004a) Bridging the Gap: Toward A Realist-Constructivist Dialogue. Internatio

ies Review 6(2): 337-352.

Jackson, P. T. (2004b) Hegel's House, or 'People are states too.' Review of International S

281-287.

Jackson, P. T., and D. H. Nexon. (1999) Relations Before States: Substance, Process and the Study

of World Politics. European fournal of International Relations 5(3): 291-332.

Jackson, P. T., and D. Nexon. (2009) The Relational Turn in the Study of World Politics. Paper

presented at the 50th Annual Convention of the International Studies Association, New York,

NY, February 2009.

Kahl, C. (1999) Constructing a Separate Peace: Constructivism, Collective Liberal Identity, and Dem-

ocratic Peace. Security Studies 8(2): 94-144.

Keohane, R. O. (2009) Political Science as a Vocation. PS: Political Science and Politics 42(2): 359-363.

King, G., R. O. Keohane, and S. Verba. (1994) Designing Social Inquiry: Scientific Inference in Qualita-

tive Research. Princeton, NI: Princeton University Press.

Maoz, Z., and B. Russett. (1993) Normative and Structural Causes of Democratic Peace, 1946-

1986. American Political Science Review 87(3): 624-638.

Mearsheimer, J. J. (2001) The Tragedy of Great Power politics. New York: Norton.

Monroe, K. R., Ed. (2005) Perestroika! The Raucous Rebellion in Political Science. New Haven, CT: Yale

University Press.

Nexon, D. H. (2009) The Struggle for Power in Early Modern Europe: Religious Conflict, Dynastic Empires,

and International Change. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Oren, I. (1995) The Subjectivity of the 'Democratic' Peace. International Security 20(2): 147-184.

Parsons, C. (2007) How to Map Arguments in Political Science. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Powell, R. (1994) Anarchy in International Relations Theory: the Neorealist - Neoliberal Debate.

International Organization 48(2): 313-344.

Price, R., and C. Reus-Smit. (1998) Dangerous Liaisons? Critical International Theory and Con-

structivism. European Journal of International Relations 4(3): 259-294.

Schwartz-Shae, P., and D. Yanow. (2002) 'Reading' 'Methods' 'Texts': How Research Methods

Texts Construct Political Science. Political Research Quarterly 55(2): 457-486.

Skocpol, T. (1994) Social Revolutions in the Modern World. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Snyder, J. (2004) One World, Rival Theories. Foreign Policy 145 (Nov/Dec) 52-62.

Sterling-Folker, J. (2000) Competing Paradigms or Birds of a Feather? Constructivism and Neolib-

eral Institutionalism Compared. International Studies Quarterly 44: 97-119.

Suganami, H. (1996) On the Causes of War. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Tickner, J. A. (1995) What Is Your Research Program? Some Feminist Answers to International Rela-

tions Methodological Questions. International Studies Quarterly 49(1): 1-22.

Tilly, C. (1995) To Explain Political Processes. The American Journal of Sociology 100(6): 1594-1610.

Tilly, C. (2006) Why? Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Van Evera, S. (1997) Guide to Methods for Students of Political Science. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University

Press.

Waever, O. (1996) The Rise and Fall of the Inter-Paradigm Debate. In International Theory: Positivism

and Beyond , edited by S. Smith, K. Booth, and M. Zalewski. Cambridge: Cambridge University

Press.

Walt, S. M. (1998) International Relations: One World, Many Theories. Foreign Policy 110 (Spring)

29-46.

Waltz, K. (1979) Theory of International Politics. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley Pub. Co.

Weber, M. (1968) Economy and Society ; An Outline of Interpretive Sociology. New York: Bedminster Press.

This content downloaded from

98.7.4.89 on Mon, 22 May 2023 16:58:02 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

You might also like

- Let's Learn French PDFDocument87 pagesLet's Learn French PDFtopze100% (1)

- Festival and Special Event Management - AllenDocument3 pagesFestival and Special Event Management - Allenvaleria_popa33% (6)

- The Scholarship of Teaching and Learning In and Across the DisciplinesFrom EverandThe Scholarship of Teaching and Learning In and Across the DisciplinesRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Three Approaches To Case Study Methods in Education - Yin Merriam PDFDocument21 pagesThree Approaches To Case Study Methods in Education - Yin Merriam PDFIrene Torres100% (1)

- Thinking as Researchers Innovative Research Methodology Content and MethodsFrom EverandThinking as Researchers Innovative Research Methodology Content and MethodsNo ratings yet

- Interactional Research Into Problem-Based LearningFrom EverandInteractional Research Into Problem-Based LearningSusan M. BridgesNo ratings yet

- Mixed MethodsDocument30 pagesMixed MethodsNguyen Quang100% (1)

- Mixed-Methods Research: A Discussion On Its Types, Challenges, and CriticismsDocument12 pagesMixed-Methods Research: A Discussion On Its Types, Challenges, and CriticismsJester ManioNo ratings yet

- 577 517 PB PDFDocument181 pages577 517 PB PDFAgnishaThyagraajanNo ratings yet

- Curriculum Management StrategyDocument36 pagesCurriculum Management StrategyBheki TshimedziNo ratings yet

- Research Dilemmas - Paradigms, Methods and MetDocument8 pagesResearch Dilemmas - Paradigms, Methods and MetHussam RajabNo ratings yet

- INTE 30103 Information Processing and Handling in Libraries and Information CentersDocument4 pagesINTE 30103 Information Processing and Handling in Libraries and Information CentersAriel MaglenteNo ratings yet

- ELT J 1993 Hedge 275 7 FluencyDocument3 pagesELT J 1993 Hedge 275 7 FluencyDaniel MartinNo ratings yet

- The Role of Theory in Educational Research PDFDocument32 pagesThe Role of Theory in Educational Research PDFRanjit Singh Gill100% (1)

- Distinguishing Between Theory, Theoretical Framework, and Conceptual Framework: A Systematic Review of Lessons From The FieldDocument10 pagesDistinguishing Between Theory, Theoretical Framework, and Conceptual Framework: A Systematic Review of Lessons From The FieldShahnawaz SaqibNo ratings yet

- HR Policies at SONY Corporation BDDocument74 pagesHR Policies at SONY Corporation BDAlfred0% (1)

- Paradigmas InvestigativosDocument14 pagesParadigmas InvestigativosKotikoti Cadena100% (1)

- ASU Tempe MapDocument1 pageASU Tempe MapPriyank ShahNo ratings yet

- Er Article On Mixed MethodsDocument15 pagesEr Article On Mixed MethodsAyşenur SözerNo ratings yet

- Combining Methods in Educational and Social ResearchDocument207 pagesCombining Methods in Educational and Social ResearchaasallamNo ratings yet

- Doctoral Seminar I: Research, Theories and IssuesDocument16 pagesDoctoral Seminar I: Research, Theories and IssuesEduardo GuadalupeNo ratings yet

- Er Article On Mixed MethodsDocument15 pagesEr Article On Mixed MethodsZACHARY CAROGNo ratings yet

- Riazi 2014Document40 pagesRiazi 2014Weronika KrzebietkeNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 103.21.125.84 On Tue, 27 Dec 2022 09:07:57 UTCDocument14 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 103.21.125.84 On Tue, 27 Dec 2022 09:07:57 UTCA NNo ratings yet

- The Principles of Learning and Teaching PoLT PDFDocument20 pagesThe Principles of Learning and Teaching PoLT PDFWedo Nofyan FutraNo ratings yet

- Mixed Methods Research: A Research Paradigm Whose Time Has ComeDocument14 pagesMixed Methods Research: A Research Paradigm Whose Time Has ComeBo ColemanNo ratings yet

- M MR in Language Teaching 2014Document41 pagesM MR in Language Teaching 2014zinta logNo ratings yet

- Explanatory Sequential Mixed Method Design As The Third Research Community of Knowledge ClaimDocument9 pagesExplanatory Sequential Mixed Method Design As The Third Research Community of Knowledge ClaimFerdinand BulusanNo ratings yet

- Three Approaches To Case Study Methods in Education: Yin, Merriam, and StakeDocument20 pagesThree Approaches To Case Study Methods in Education: Yin, Merriam, and StakeShumaila OmarNo ratings yet

- Johnson & Onwuegbuzie PDFDocument14 pagesJohnson & Onwuegbuzie PDFmauricio.ramirezcuevas7585No ratings yet

- Jacob, W. James - Global Trends in Educational PolicyDocument38 pagesJacob, W. James - Global Trends in Educational PolicySri LindusariNo ratings yet

- Achieving Emphaty and EngagementDocument15 pagesAchieving Emphaty and EngagementPanagiotis PantzosNo ratings yet

- 6.4mixed Methods ResearchDocument14 pages6.4mixed Methods ResearchJiayuan XuNo ratings yet

- The Principles of Learning and Teaching PoLT PDFDocument20 pagesThe Principles of Learning and Teaching PoLT PDFMindy Penat PagsuguironNo ratings yet

- Three Approaches To Case Study Methods in Education: Yin, Merriam, and StakeDocument20 pagesThree Approaches To Case Study Methods in Education: Yin, Merriam, and StakeRenata JapurNo ratings yet

- Heutagogy and Lifelong Learning A Question of Self-Determined Practices in Post Secondary Education - 1-95 (90-95)Document6 pagesHeutagogy and Lifelong Learning A Question of Self-Determined Practices in Post Secondary Education - 1-95 (90-95)CIK JAMALIAH ABD MANAFNo ratings yet

- Views on Combining Quantitative and Qualitative ResearchDocument14 pagesViews on Combining Quantitative and Qualitative Researchmaddog67No ratings yet

- The Interdisciplinary Research ProcessDocument18 pagesThe Interdisciplinary Research ProcessAntara AdachiNo ratings yet

- Research Design in Quantitative-Qualitative-Mixed Methods-41165 - 10Document36 pagesResearch Design in Quantitative-Qualitative-Mixed Methods-41165 - 10TEFFANIE VALLECERNo ratings yet

- 4Document10 pages4batiri garamaNo ratings yet

- Johnson Mixed Methods 2004 PDFDocument14 pagesJohnson Mixed Methods 2004 PDFMarianna AntonopoulouNo ratings yet

- MIE Journal of Education Volume 11 Special Issue December 2020Document93 pagesMIE Journal of Education Volume 11 Special Issue December 2020Luchmee Devi GoorjhunNo ratings yet

- The Oxford Handbook of Quantitative Methods, Vol 1 FoundationsDocument32 pagesThe Oxford Handbook of Quantitative Methods, Vol 1 FoundationsPlesoianu Ana MariaNo ratings yet

- 1 (Group - 1) Creswell a Movement to Mixed Method StudyDocument13 pages1 (Group - 1) Creswell a Movement to Mixed Method Studylily88141011No ratings yet

- POL 404-Research Methods For International Studies - SyllabusDocument10 pagesPOL 404-Research Methods For International Studies - SyllabusHalwest ShekhaniNo ratings yet

- The Usefulness of Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches and Methods in Researching Problem-Solving Ability in Science Education CurriculumDocument10 pagesThe Usefulness of Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches and Methods in Researching Problem-Solving Ability in Science Education CurriculumGlazelle Paula PradoNo ratings yet

- Approaches in Science Teacher Preparation: A Comparative Study of England and ZimbabweDocument21 pagesApproaches in Science Teacher Preparation: A Comparative Study of England and ZimbabwejcarlaalejoNo ratings yet

- Teacher Identity Development in Professional Learning: An Overview of Theoretical FrameworksDocument11 pagesTeacher Identity Development in Professional Learning: An Overview of Theoretical FrameworksNBNo ratings yet

- Sequential Mixed Model Research DesignDocument15 pagesSequential Mixed Model Research DesignDzawo GilbertNo ratings yet

- RenckJalongo Saracho2016 Chapter FromMixed MethodsResearchToAJoDocument23 pagesRenckJalongo Saracho2016 Chapter FromMixed MethodsResearchToAJoFermilyn AdaisNo ratings yet

- IIER 16 - Mackenzie and Knipe - Research Dilemmas - Paradigms, Methods and MethodologyDocument11 pagesIIER 16 - Mackenzie and Knipe - Research Dilemmas - Paradigms, Methods and MethodologyAdi Sasongko RomadhonNo ratings yet

- 20 ArticleText 32 1 10 20210224Document13 pages20 ArticleText 32 1 10 20210224zin GuevarraNo ratings yet

- The Effectiveness of Research in Educational Policy ChangesDocument24 pagesThe Effectiveness of Research in Educational Policy ChangesAndrea de SouzaNo ratings yet

- Brundett Rhodes 2011Document12 pagesBrundett Rhodes 2011api-354669211No ratings yet

- Etec 500 Journal AssignmentDocument7 pagesEtec 500 Journal Assignmentapi-381478303No ratings yet

- 10 1002@tea 21082Document36 pages10 1002@tea 21082Lia Laily Mukaromatil AhyarNo ratings yet

- Qualitative Methods in Teaching ResearchDocument43 pagesQualitative Methods in Teaching ResearchMisiara SantosNo ratings yet

- Constructive Action Research A Perspective On The Process of LearningDocument19 pagesConstructive Action Research A Perspective On The Process of LearningGizzelle LigutomNo ratings yet

- Teaching-Learning Sequences: Aims and Tools For Science Education ResearchDocument22 pagesTeaching-Learning Sequences: Aims and Tools For Science Education ResearchKoimahNo ratings yet

- Alexander 2018Document15 pagesAlexander 2018Cristell BiñasNo ratings yet

- Sampson 2013Document28 pagesSampson 2013Dea PermataNo ratings yet

- Bikner-Ahsbahs Et Al. - Investigación Cualitativa en Educación Matemática PDFDocument587 pagesBikner-Ahsbahs Et Al. - Investigación Cualitativa en Educación Matemática PDFlina caamañoNo ratings yet

- Capstone Projects and Their Potential Contributions To Professional Research - Tomorrow's Professor PostingsDocument2 pagesCapstone Projects and Their Potential Contributions To Professional Research - Tomorrow's Professor Postingssoo kimNo ratings yet

- Ercikan + Roth 2006 ERDocument10 pagesErcikan + Roth 2006 ERKatherine Uran RamirezNo ratings yet

- Adapting Design-Based Research As A Research Methodology in Educational SettingsDocument12 pagesAdapting Design-Based Research As A Research Methodology in Educational SettingsMaria GuerreroNo ratings yet

- JRP - How and Why To Teach Interdisciplinary Research PracticeDocument16 pagesJRP - How and Why To Teach Interdisciplinary Research PracticeKorghulNo ratings yet

- A Practical Guide to Mixed Research Methodology: For research students, supervisors, and academic authorsFrom EverandA Practical Guide to Mixed Research Methodology: For research students, supervisors, and academic authorsNo ratings yet

- Professional Ethics & Human Values SummaryDocument13 pagesProfessional Ethics & Human Values SummaryKalasekar M Swamy50% (2)

- UntitledDocument6 pagesUntitledvaibhav sharmaNo ratings yet

- Emergence and Evaluation of Display BoardDocument9 pagesEmergence and Evaluation of Display BoardSAMPURNA GANGULYNo ratings yet

- ELICOS Pathways to Further StudyDocument2 pagesELICOS Pathways to Further StudyNguyen Hoang YenNo ratings yet

- COT3100 FinalDocument3 pagesCOT3100 FinalMatthew StebbinsNo ratings yet

- Personal and Possessive Pronoun: Learning Activity Sheet Quarter 2-Week 2Document11 pagesPersonal and Possessive Pronoun: Learning Activity Sheet Quarter 2-Week 2Lynlyn EppitNo ratings yet

- Dawn Scuderi ResumeDocument2 pagesDawn Scuderi Resumeapi-217122719No ratings yet

- Gold in 2000 Scientific Perspective Kelly and LeshDocument79 pagesGold in 2000 Scientific Perspective Kelly and LeshAdriana Yulieth Aldana LeonNo ratings yet

- Guidelines in Hiring TeachersDocument75 pagesGuidelines in Hiring TeachersUMC Rainbow SchoolNo ratings yet

- Lesson Plan in Mathematics IIDocument2 pagesLesson Plan in Mathematics IIIvy Rose MagbanuaNo ratings yet

- The Psychology Self-Management OrganizationsDocument26 pagesThe Psychology Self-Management OrganizationsYehia IbrahimNo ratings yet

- The Influence of Corporate Culture on Organizational Commitment in Malaysian Semiconductor OrganizationsDocument18 pagesThe Influence of Corporate Culture on Organizational Commitment in Malaysian Semiconductor OrganizationsAisha MushtaqNo ratings yet

- Attendence of CandidatesDocument2 pagesAttendence of CandidatesMohammad Abdullah NabilNo ratings yet

- Monash Graduate Course Guide InternationalDocument59 pagesMonash Graduate Course Guide InternationalWesley WesloqNo ratings yet

- Lesson Log CLE 4Document2 pagesLesson Log CLE 4Jonalyn CostunaNo ratings yet

- ES SPED Teacher AssistantDocument2 pagesES SPED Teacher AssistantFrancis A. BuenaventuraNo ratings yet

- Lesson PlanDocument7 pagesLesson PlanErma PerezNo ratings yet

- Columbia 1987-02-25 0001Document11 pagesColumbia 1987-02-25 0001Becket AdamsNo ratings yet

- University College of Technology Sarawak: Assignment 1Document11 pagesUniversity College of Technology Sarawak: Assignment 1Mohammad Zulhelmi AkmalNo ratings yet

- Understanding the Life of a BullyDocument35 pagesUnderstanding the Life of a BullyCorinne ArtatezNo ratings yet

- Unit 3 Assignment Part B 5Document3 pagesUnit 3 Assignment Part B 5api-314003507No ratings yet

- Department of Education: Republic of The PhilippinesDocument3 pagesDepartment of Education: Republic of The PhilippinesEmerito PerezNo ratings yet