Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The Nazis Were Right-Wing

Uploaded by

Maks imilijan0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

6 views6 pagesend of discussion.

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

ODT, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this Documentend of discussion.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as ODT, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

6 views6 pagesThe Nazis Were Right-Wing

Uploaded by

Maks imilijanend of discussion.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as ODT, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 6

The Nazis were Right-Wing (Part 1 of 2) https://www.youtube.com/watch?

v=TYfYMbg-HqI The Nazis were Right-Wing (Part 2 of

2) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mkCywtE7yak Steven Crowder: "Hitler was a Liberal Socialist" DEBUNKED

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mmVaXA6jJgk The following could be a MAGA rally: "Socialism is the science of dealing with

the common weal. Communism is not Socialism. Marxism is not Socialism. The Marxians have stolen the term and confused its

meaning. I shall take Socialism away from the Socialists. Socialism is an ancient Aryan, Germanic institution. Our German ancestors

held certain lands in common. They cultivated the idea of the common weal. Marxism has no right to disguise itself as socialism.

Socialism, unlike Marxism, does not repudiate private property. Unlike Marxism, it involves no negation of personality, and unlike

Marxism, it is patriotic. We might have called ourselves the Liberal Party. We chose to call ourselves the National Socialists. We are

not internationalists. Our socialism is national. We demand the fulfilment of the just claims of the productive classes by the state on

the basis of race solidarity. To us state and race are one."- Hitler Hitler hated Social Justice like The Right does now: "Because it

seems inseparable from the social idea and we do not believe that there could ever exist a state with lasting inner health if it is not

built on internal social justice, and so we have joined forces with this knowledge" Hitler thought whites were the best people and

culture in the world like the right does The minority anti-capitalist strand of Nazism (Strasserism) on which van Onselen fastens was

eliminated well before 1934, when Gregor Strasser and the Storm Trooper (SA) leader Ernst Roehm were murdered with over eighty

others in the "Night of the Long Knives." In fact, Strasserism had already been defeated at the Bamberg Conference of 1926 when

the Nazis were polling under 3% of the vote. Here, Hitler brought the dissidents back into line, denouncing them as "communists"

and ruling out land expropriations and grassroots decision-making. He heightened the party's alliance with businesses small and

large, and insisted on the absolute centralisation of decision-making - the "Fuehrer (leader) Principle."

https://www.abc.net.au/religion/nazismsocialism-and-the-falsification-of-history/10214302 Nazis were not socialists in any way,

shape or form. They were industrialist capitalists, like England and America. The Nazi war machine consisted of huge factories that

were privately owned by giant corporations, like ThyssenKrupp.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Political_views_of_Adolf_Hitler#Anti-communism Hitler advocated for "the destruction of Marxism in

all its shapes and forms".[109] According to Hitler, Marxism was a Jewish strategy to subjugate Germany and the world and saw

Marxism as a mental and political form of slavery. ”The German state is gravely attacked by Marxism” Mein Kampf p.535 ”In the

years 1913 and 1914 I expresssed the conviction that the question of the future of the German nation was the question of destroying

Marxism” Mein Kampf p. 155 ”Marxism itself systematically plans to hand over the world to the Jews! Mein Kampf p.382 ”The

Jewish doctrine of Marxism rejects the principle of nature and replaces the eternal privilege of power and strength by the mass of

numbers and their dead weight. Mein Kampf. p.60 ”We stand for the maintenance of private property... We shall protects free

enterprise as the most expedient, or rather the sole possible economic order... – Adolf Hitler (Heiden, The Fuhrer, p.105. You can

have publicly owned industry and still be capitalist. Look at the American New Deal; the post-war welfare state in the UK; the

Scandinavian social democratic model, etc. Plus, capitalism is defined by capitalist relations of production, too. Or, basically any

form of Keynesian interventionism. This is besides the fact that capitalism requires the state, for the legitimation of private property

rights, and their legal enforcement. If you claim that you have the right to a piece of land, how would you back that up without a

legal framework that recognises private property rights? Likewise, the state very often has to step in, both to secure property rights,

prevent action by other classes, and nominally maintain an even playing field for competition. The primary functions of the capitalist

state are to provide a legal framework and infrastructural framework conducive to business enterprise and the accumulation of

capital. If any intervention in the market by the state is fascism, then this would lead to absurd conclusions, like saying France is

socialist. Also, this is very different from the economic formation known as state-capitalism. State capitalism is used by various

authors in reference to a private capitalist economy controlled by a state, i.e. a private economy that is subject to economic planning

and interventionism. It has also been used to describe the controlled economies of the Great Powers during World War I. The great

powers included Britain, France, Austria, Prussia and Russia. If we follow the argument here, than the empires of all these countries

at the time bar Russia, would be socialist - if we conflate socialism with state ownership of/intervention in the market. Or, if we

follow your argument that any state intervention constitutes fascism, then all these countries would be fascist In Fascism, the state is

run as a corporate, hierarchical body, where everyone is assigned a place from which they cannot deviate. Hence, in his doctrine of

fascism, Musollini writes, 'No individuals or groups (political parties, cultural associations, economic unions, social classes) outside

the State. Fascism is therefore opposed to Socialism to which unity within the State (which amalgamates classes into a single

economic and ethical reality) is unknown, and which sees in history nothing but the class struggle. Fascism is likewise opposed to

trade unionism as a class weapon. But when brought within the orbit of the State, Fascism recognizes the real needs which gave rise

to socialism and trade unionism, giving them due weight in the guild or corporative system in which divergent interests are

coordinated and harmonized in the unity of the State (16). Likewise, in Mussolini's 'The Doctrine of Fascism', 'Such a conception of

life makes Fascism the resolute negation of the doctrine underlying so called scientific and Marxian socialism, the doctrine of historic

materialism which would explain the history of mankind in terms of the class struggle and by changes in the processes and

instruments resolute negation of the doctrine underlying so called scientific and Marxian socialism,[...]" Hell, Mussolini in the same

text has a section called, 'The Rejection of Marxism': 'Having denied historic materialism, which sees in men mere puppets on the

surface of history, appearing and disappearing on the crest of the waves while in the depths the real directing forces move and work,

Fascism also denies the immutable and irreparable character of the class struggle which is the natural outcome of this economic

conception of history; above all it denies that the class struggle is the preponderating agent in social transformations. Having thus

struck a blow at socialism in the two main points of its doctrine, all that remains of it is the sentimental aspiration, old as humanity

itself-toward social relations in which the sufferings and sorrows of the humbler folk will be alleviated' As the name suggests,

fascism sought to bundle the folk together, like a bundle of sticks, arguing every class had its proper place, gathering them together

for war. To quote Musollini again; '[The state] is not simply a mechanism which limits the sphere of the supposed liberties of the

individual... Neither has the Fascist conception of authority anything in common with that of a police ridden State... Far from

crushing the individual, the Fascist State multiplies his energies, just as in a regiment a soldier is not diminished but multiplied by the

number of his fellow soldiers' This is NOWHERE NEAR what Marx was writing about when he wrote of direct democracy in the

commune, and the abolition of the state, money and classes. Mussolini, like all fascists, was a virulent anti-communist. During the

coalition period, Mussolini appointed a classical liberal economist, Alberto De Stefani, originally a stalwart leader in the Center Party

as Italy’s Minister of Finance, who advanced economic liberalism, along with minor privatization. Before his dismissal in 1925,

Stefani "simplified the tax code, cut taxes, curbed spending, liberalized trade restrictions and abolished rent controls", where the

Italian economy grew more than 20 percent, and unemployment fell 77 percent, under his influence. The full name of Adolf Hitler’s

Nazi Party, the political movement that brought him to power and supplied the infrastructure of the fascist dictatorship over which he

would preside, was Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei, the National Socialist German Workers’ Party. According to

historians, the complicated moniker reveals more about the image the party wanted to project and the constituency it aimed to build

than it did about the Nazis’ true political goals, which were building a state based on racial superiority and brute-force governance.

Given that Nazism is traditionally held to be an extreme right-wing ideology, the party’s conspicuous use of the term “socialist” —

which refers to a political system normally plotted on the far-left end of the ideological spectrum — has long been a source of

confusion, not to mention heated debate among partisans seeking to distance themselves from the genocidal taint of Nazi Germany.

The debate has heated up to the point of critical mass in recent years, thanks to the rise of nationalist political movements reacting in

part to stagnant economic conditions and the perceived threat of globalism, and also in part to a flood of immigrants and foreign

refugees pouring into Europe and the United States because of war and economic crises abroad. A subset of these groups, identified

as ethno-nationalists, hold racially-tinged views ranging from nativism (the belief that the interests of native-born people must be

defended against encroachment by immigrants) to full-on, hate-mongering white supremacy. Some of the latter openly align

themselves with historical Nazism, to the point of waving swastikas, spouting anti-Semitic rhetoric, and imitating the tactics of Adolf

Hitler. Add to this mix the ascendancy of President Donald Trump, who won the 2016 election in part by courting a nativist, anti-

immigrant constituency, and whose reticent condemnation of white nationalist protesters who held a rally in Charlottesville, Virginia

that erupted in fatal violence in August 2017 drew howls of criticism from all but his most loyal supporters, and the urgency of

sorting out these political associations begins to make sense. The Nazi Problem Nobody, least of all the millions of rank-and-file

right-leaning Americans who voted for Donald Trump, wants to be lumped in with Nazis. It’s a fact, however, that Nazi-friendly

organizations, Nazi symbols, and Nazi gestures were in evidence at the disastrous Charlottesville event, whose unfortunate title was

not “Unite the Left,” but “Unite the Right.” Although the terms “left” and “right” as used in American politics can be somewhat less

than perspicuous, they are helpful in delineating the basic ideological divide between liberalism/progressivism (as embodied mainly

by the Democratic Party) on one side (“the left”), and conservatism/traditionalism (as embodied mainly by the Republican Party) on

the other (“the right”). Seen as a spectrum or continuum of ideologies, socialism/communism traditionally falls on the far left end of

this scale, nationalism/fascism on the far right. The Nazi problem comes down to this: As an ultra-nationalist, socially conservative,

anti-egalitarian and fascist ideology, Nazism naturally falls on the extreme far-right end of the political spectrum; but if it can be

successfully argued that it’s really a form of socialism, it would make more sense to place it on the far left. That being the case, it’s

becoming more and more common to encounter insistent polemics like this one published on the right-wing blog UFP News: The

Nazis were left-wing socialists. Yes, the National Socialist Workers Party of Germany, otherwise known as the Nazi Party, was

indeed socialist and it had a lot in common with the modern left. Hitler preached class warfare, agitating the working class to resist

“exploitation” by capitalists , particularly Jewish capitalists, of course. Their programs called for the nationalization of education,

health care, transportation, and other major industries. They instituted and vigorously enforced a strict gun control regimen. They

encouraged pornography, illegitimacy, and abortion, and they denounced Christians as right-wing fanatics. Yet a popular myth

persists that the Nazis themselves were right-wing extremists. This insidious lie biases the entire political landscape today. A similar

argument is propounded in the 2017 book The Big Lie: Exposing the Nazi Roots of the American Left by Dinesh D’Souza, who

maintains that Adolf Hitler himself was a “dedicated socialist”: In statement after statement, Hitler could not be clearer about his

socialist commitments. He said, for example, in a 1927 speech, “We are socialists. We are the enemies of today’s capitalist system of

exploitation … and we are determined to destroy this system under all conditions.” (Actually a Strasser quote, whom Hitler killed for

being... a socialist...) However, the assumption that because the word “socialist” appeared in the party’s name and socialist words and

ideas popped up in the writings and speeches of top Nazis then the Nazis must have been actual socialists is naive and ahistorical.

What the evidence shows, on the contrary, is that Nazi Party leaders paid mere lip service to socialist ideals on the way to achieving

their one true goal: raw, totalitarian power. Richard J. Evans: ‘It Would Be Wrong to See Nazism as a Form of, or an Outgrowth

From, Socialism’ Despite having declared, at various times, “I am a socialist,” “We are socialists,” and similar avowals, on a personal

level Hitler displayed little regard for the actual tenets of socialism, or, for that matter, socialists themselves. This excerpt from a

speech Hitler gave in 1922 (quoted in William L. Shirer’s The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich, published in 1960) is indicative:

Whoever is prepared to make the national cause his own to such an extent that he knows no higher ideal than the welfare of the

nation; whoever has understood our great national anthem, “Deutschland ueber Alles,” to mean that nothing in the wide world

surpasses in his eyes this Germany, people and land — that man is a Socialist. And this is what came out of Adolf Hitler’s mouth on

another occasion when a comrade riled him by harping on socialism (as reported by Henry A. Turner, author of German Big Business

and the Rise of Hitler, published in 1985): Socialism! What does socialism really mean? If people have something to eat and their

pleasures, then they have their socialism. In his 2010 book Hitler: A Biography, British historian Ian Kershaw wrote that despite

putting the interests of the state above those of capitalism, he did so for reasons of nationalism and was never a true socialist by any

common definition of the term: [Hitler] was wholly ignorant of any formal understanding of the principles of economics. For him, as

he stated to the industrialists, economics was of secondary importance, entirely subordinated to politics. His crude social-Darwinism

dictated his approach to the economy, as it did his entire political “world-view.” Since struggle among nations would be decisive for

future survival, Germany’s economy had to be subordinated to the preparation, then carrying out, of this struggle. This meant that

liberal ideas of economic competition had to be replaced by the subjection of the economy to the dictates of the national interest.

Similarly, any “socialist” ideas in the Nazi programme had to follow the same dictates. Hitler was never a socialist. But although he

upheld private property, individual entrepreneurship, and economic competition, and disapproved of trade unions and workers’

interference in the freedom of owners and managers to run their concerns, the state, not the market, would determine the shape of

economic development. Capitalism was, therefore, left in place. But in operation it was turned into an adjunct of the state. For

members of the Nazi Party, in fact, defending socialism on its own terms was a risky activity which could result in ejection from the

party, or worse. Of party leader and dissenter Otto Strasser (whose similarly-minded brother, Gregor, would ultimately be

assassinated by the Nazis), William Shirer writes: Unfortunately for him, he had taken seriously not only the word “socialist” but the

word “workers” in the party’s official name of National Socialist German Workers’ Party. He had supported certain strikes of the

socialist trade unions and demanded that the party come out for nationalization of industry. This of course was heresy to Hitler, who

accused Otto Strasser of professing the cardinal sins of “democracy and liberalism.” On May 21 and 22, 1930, the Fuehrer had a

showdown with his rebellious subordinate and demanded complete submission. When Otto refused, he was booted out of the party.

The plain truth, writes Historian Richard J. Evans in The Coming of the Third Reich, was that Hitler and his party saw socialism,

communism, and leftism generally as inimical to everything they hoped to achieve: In the climate of postwar counter-revolution,

national brooding on the “stab-in-the-back,” and obsession with war profiteers and merchants of the rapidly mushrooming

hyperinflation, Hitler concentrated especially on rabble-rousing attacks on “Jewish” merchants who were supposedly pushing up the

price of goods: they should all, he said, to shouts of approval from his audiences, be strung up. Perhaps to emphasize this anti-

capitalist focus, and to align itself with similar groups in Austria and Czechoslovakia, the party changed its name in February 1920 to

the National Socialist German Workers’ Party…. Despite the change of name, however, it would be wrong to see Nazism as a form

of, or an outgrowth from, socialism. True, as some have pointed out, its rhetoric was frequently egalitarian, it stressed the need to put

common needs above the needs of the individual, and it often declared itself opposed to big business and international finance

capital. Famously, too, antiSemitism was once declared to be “the socialism of fools.” But from the very beginning, Hitler declared

himself implacably opposed to Social Democracy and, initially to a much smaller extent, Communism: after all, the “November

traitors” who had signed the Armistice and later the Treaty of Versailles were not Communists at all. What Nazism Stood For The

National Socialists completely ignored socialism’s primary aim (replacing the existing class-based society with an egalitarian one in

which workers owned the means of production) and substituted their own topsy-turvy agenda, Evans writes, “replacing class with

race, and the dictatorship of the proletariat with the dictatorship of the leader”: The “National Socialists” wanted to unite the two

political camps of left and right into which, they argued, the Jews had manipulated the German nation. The basis for this was to be

the idea of race. This was light years removed from the class-based ideology of socialism. Nazism was in some ways an extreme

counter-ideology to socialism, borrowing much of its rhetoric in the process, from its selfimage as a movement rather than a party, to

its much-vaunted contempt for bourgeois convention and conservative timidity. German historian and National Socialism expert

Joachim Fest characterizes this repurposing of socialist rhetoric as an act of “prestidigitation”: This ideology took a leftist label

chiefly for tactical reasons. It demanded, within the party and within the state, a powerful system of rule that would exercise

unchallenged leadership over the “great mass of the anonymous.” And whatever premises the party may have started with, by 1930

Hitler’s party was “socialist” only to take advantage of the emotional value of the word, and a “workers’ party” in order to lure the

most energetic social force. As with Hitler’s protestations of belief in tradition, in conservative values, or in Christianity, the socialist

slogans were merely movable ideological props to serve as camouflage and confuse the enemy. The proof was in the pudding. Not

long after acquiring the reins of power, the Nazis banned the Social Democratic Party and sent its leaders and other leftists identified

as threats to the National Socialist program to concentration camps. According to the Holocaust Encyclopedia: In the months after

Hitler took power, SA and Gestapo agents went from door to door looking for Hitler’s enemies. They arrested Socialists,

Communists, trade union leaders, and others who had spoken out against the Nazi party; some were murdered. By the summer of

1933, the Nazi party was the only legal political party in Germany. Nearly all organized opposition to the regime had been

eliminated. Democracy was dead in Germany. Despite continuing certain Weimar-era social welfare programs, the Nazis proceeded

to restrict their availability to “racially worthy” (non-Jewish) beneficiaries. In terms of labor, worker strikes were outlawed. Trade

unions were replaced by the party-controlled German Labor Front, primarily tasked with increasing productivity, not protecting

workers. In lieu of the socialist ideal of an egalitarian, worker-run state, the National Socialists erected a party-run police state whose

governing structure was anti-democratic, rigidly hierarchical, and militaristic in nature. As to the redistribution of wealth, the socialist

ideal “From each according to his ability, to each according to his need” was rejected in favor of a credo more on the order of “Take

everything that belongs to non-Aryans and keep it for the master race.” Above all, the Nazis were German white nationalists. What

they stood for was the ascendancy of the “Aryan” race and the German nation, by any means necessary. Despite co-opting the name,

some of the rhetoric, and even some of the precepts of socialism, Hitler and party did so with utter cynicism, and with vastly different

goals. The claim that the Nazis actually were leftists or socialists in any generally accepted sense of those terms flies in the face of

historical reality. https://www.abc.net.au/religion/nazism-socialism-and-the-falsification-of-history/10214302 Theories Of Nazism

And Fascism ; Palingenetic Ultranationalism(Roger Griffin) Roger Griffin adopted a Weberian ideal-type methodology to define the

nature of Fascism. On this basis he criticized the typological definition of Fascism put forward by Payne. Adopting Georges Sorel's

theory of political myth, Griffin argued that Fascism can be defined in terms not of a common ideological component, but of a

common mythic core. According to Griffin, "Fascism is a genus of political ideology whose mythic core in its various permutations is

a palingenetic form of populist ultra-nationalism." This definition combines two central components; first the palingenetic myth of

rebirth and regeneration defined as "the vision of a revolutionary new order which supplies the effective power of an ideology".

Second Fascism as "Ultranationalism" referring to a form of nationalism that explicitly rejects liberal institutions and the humanist

legacy of enlightenment. Fascism thus emerges when populist ultra-nationalism combines with the myth of a radical crusade against

decadence and for renewal in every sphere of national life . The result is an ideology which operates a mythic core celebrating the

unity and sovereignty of the whole people in a specifically anti-liberal and anti-Marxist sense. The mythic core that forms the basis of

Griffin's generic fascism is the vision of the percieved crisis of the nation as indicating the birth-pangs of a new order. The idea that

'nation' is an entity which can decay and be regenerated, implies something diametrically opposed to what libearals understand by it.

According to Griffin, Fascists felt he had been fatefully born at a watershed between national decline and national regeneration, a

feeling that alchemically converted all pessimism and cultural despair into a manic sense of purpose and optimism. His task it was to

prepare the ground for the new breed of men, the homo fascists, who would instinctively form part of the revitalized national

community without having first to purge himself of the selfish reflexes inculcated by a civilization sapped by egotism and

materialism. Anti-liberal - Griffin propounded that Fascism's call for the regeneration of the national community through a heroic

struggle against its alleged enemies and the forces undermining it. It involves the radical rejection of liberalism in all its aspects ;

pluralism, tolerance, individualism, pacifism, parliamentary democracy, the separation of powers, egalitarianism etc. Anti-

conservative - For Griffin, The centrality to fascism is a myth of the nation's regeneration within a new order implies a rejection of

illiberal conservative politics, as well as of liberal and authoritarian conservative solution to the current crisis. In other words, in the

context of fascism 'rebirth' means 'new birth' , 'a new order', one which might draw inspiration from the past but doesn't seek to turn

the clock back. However two factors have obscurred fascism's revolutionary, forward looking thrust. First, in order to achieve power

in the interwar period fascism was forced to ally itself with conservative force on the basis of common enemies and common

priorities. Second fascist ideologues frequently attach great importance to allegedly glorious epochs in the nation's past and the

heroes which embody them. They do so not out of nostalgia, but to remind the people of the nation's 'true' nature and its destiny to

rise once more to historical greatness. Charismatic form of Politics - Since to use Weberian terminology, fascism rejects both the

traditional politics of the ancien regime and the legal rational politics of liberalism and socialism, it follows charismatic form of

politics. This doesn't necessarily involve the epitome of such politics, the leader cult. All political ideologies are prone to assume a

charismatic aspect when they operate as revolutionary forces - liberalism did, for eg ; in French Revolution. It is significant, though,

that fascism remained a charismatic form of politics in the two cases where it managed to install itself in power. Fascist Socialism -

Griffin argued that, if it is core mobilizing myth of the imminent rebirth of the nation that forms the definitional core of fascism, it

follows that the various fascist negations(anti-communism, anti-liberalism etc) are corollaries of this positive belief not definitional

components. The same myth explains the recurrent claim by fascist ideologues that their vision of the new order is far from anti-

socialist. Hitler had a shadow of left way thinking. Link to Totalitarianism - In the words of Griffin, Also implicit in fascism's mythic

core is the drive towards totalitarianism. For from being driven by Nihilism or Barbarism, the convinced fascist is a Utopian,

conceiving the homogeneous, perfectly co-ordinated national community as a total solution to the problems of modern society.

Fortunately for humanity only two fascist movements have been in a position to attempt to implement their total solutions to society's

alleged woes, namely Fascism and Nazism. Heterogeneity of fascism's social support - Griffin is of the view that, Fascism has no

specific class basis in its support. If middle class were over represented in the membership of Fascism and Nazism. This is because

specific socio-political conditions made a significant percentage of them more susceptible to a palingenetic form of Ultranationalism

than to a palingenetic form of Marxism or liberalism. Fascist racism - For Griffin, By its nature, fascism is racist, since all ultra

nationalism are racist in their celebration of the alleged virtues and greatness of an organically concieved nation or culture. Fascism is

also intrinsically anti-cosmopolitan, axiomatically rejecting as decadent liberal vision of the multicultural, multi-religious, multi-

racial society. This type of fascism thus tends to produce an apartheid mentality calling for ethnically pure nation states, for

foreigners to go back, or be returned, to 'where they belong' , and a vitriolic hatred of 'mixed marriages' and 'cultural bastardization'.

Fascist Internationalism - Fascism, anti-internationalist in the sense of regarding national distinctiveness and identity as primordial

values, is quite capable of generating its own form of universalism or internationalism by fostering a bond with fascists in other

countries engaged in an equivalent struggle for their own nation's palingenesis, often againts common enemies(e.g. liberals,

communists). In Europe, this may well lead to a sense of fighting for a common European homeland on the basis of Europe's alleged

cultural, historical, or even genetic unity in contrast to non-Christian, non-Indo European(e.g. Muslims, Asian Soviet, Chinese

Communists) or degenerated ones. Within such a Europe, national or ethnic identities would, according to the fascist blueprint, be

strengthened, not diluted. Fascist eclecticism - For Griffin, an important feature of this charismatic and identificatory form of

nationalism is its eclecticism: it can be rationalised through a wide variety of regenerationist myth drawing on historical or

pseudoscientific facts. Inevitably each fascism will be made in the image or imagining of a particular national culture, but even

within the same movement or party its most influential ideologues will inevitably represent a wide range of ideas and theories

sometimes quite incompatible with each other except at the level of a shared mythic core of palingenetic Ultra-nationalism. Fascism

is thus inherently syncretic, bringing heterogeneous current of ideas into a loose alliance united only by the common struggle for a

new order. As a result there is in fascist thought a recurrent element of synthesis. Griffin argued that it is worth adding that , in its

self-creation through synthesis, fascist ideology can draw just an early on right-wing forms of thought as on forms of left wing

thought. It is also implicit in what has been said that fascism is not necessarily confined to inter-war Europe, but can flourish

wherever the stability of Western style liberal democracy is threatened by a particular conjuncture of destabilising forces.

https://www.vox.com/2019/3/27/18283879/nazism-socialism-hitler-gop-brooks-gohmert https://fullfact.org/online/nazis-socialists/

Det är inte sällan som man från den kontemporära högern hör påståenden om kopplingar mellan nazismen och vänsterideologi, trots

att det då råder en allmänn konsensus som vidhåller att det rör sig om en högerextrem ideologi. Oftast förs tre olika typer av

argument fram för denna position. Det första är kopplat till etymologi: “National-SOCIALISM” . Antagandet utgår då ifrån att

socialismen är vänsterorienterad och att nationalSOCIALISMEN därför med automatik också är vara det. Det andra fokuserar på

statens inflytande: eftersom nazismen förser staten med makt då staten enligt nationalsocialismen är stor måste nationalsocialismen

vara vänster. Det tredje är lite mer sofistikerad och går ut på analyser av det tyska nazistpartiets (NSDAPs) olika uttalanden och

program som pekar på att de hade en social och ekonomisk jämlikhetstanke. I denna artikel ska jag försöka förklara hur och varför

den allmänna konsensus som råder kring att nazismen är en högerideologi är korrekt och bemöta de invändningar som görs om den

saken i högerformat. Höger och vänster För att reda ut hur det står till med nationalsocialismen i höger-/vänsterskalan måste vi börja

med att definiera höger- och vänsterteori. Uppdelningen av de politiska ideologierna i höger- respektive vänsterfack har sitt ursprung

i den franska Nationalförsamlingen där de konservativa och reaktionära politikerna satt till höger om kungen medan de progressiva

politikerna (främst liberaler, frihetliga socialister och statssocialister) satt till vänster. På församlingens vänstersidan fanns sådana

klassiska liberaler som nationalekonomen Frédéric Bastiat, den moderna anarkismens fader Pierre-Joseph Proudhon och

statssocialisten Louis Blanc. På den andra satt de som ville bevara den gamla ordningen, de konservativa och de som ville återgå till

någon ännu äldre och mer auktoritär ordning, de reaktionära. Den klassiska vänstern hade som mål att förändra samhället på ett

progressivt vis, den strävade efter ökad frihet och jämlikhet och sökte bryta med det rådande samhällets strukturella orättvisor och

hierarkier, något som än i dag kännetecknar vänsterteori. Ett fokus på att bevara etablerad ordning, traditionella värderingar och

rådande hierarkier kom att definieras som högerteori. Ytterlighetsvänstern ville förändra samhället på ett sätt som skulle innebära en

radikal förändring mot en omfattande frihet och jämlikhet (främst revolutionära socialister och anarkister) medan ytterlighetshögern

ville återskapa en tidigare ordning som var ännu mer hierarkisk med ett ännu större fokus på traditionella värderingar och normer än

den rådande samhällsnormen (främst reaktionärer och absoluta monarkister). Traditionella ideologier i skalan Var placerar man då

lämpligast socialismen? Naturligtvis till vänster. Socialismen, som bred rörelse och idéströming, strävar efter att frigöra individen

från kapitalistisk exploatering samtidigt som ojämlikheten mellan samhällsklasserna ska annuleras. Även på ett kulturellt plan segrar

jämlikhetstanken i socialismen vilken tidigt ledde till den Internationella arbetareassociationen, eller Internationalen, vars fokus låg

på internationalism och internationell solidaritet i de socialistiska strävandena där arbetarklassen sågs som en gränsöverskridande och

nationslös entitet. Även kampen för jämlikhet mellan olika kön och etniciteter blev tidigt en integrerad del i socialismen som en

naturlig följd av den grundläggande jämlikhetstanken. I socialismen, liksom i liberalismen, vann upplysningen mot traditionalismen.

Liberalismen hamnar till höger om socialismen då liberalerna inte ville gå lika långt i samhällsförändringarna men strävade

fortfarande efter frihet och jämlikhet i meningen avsaknad av strukturellt förtryck. Att göra människor friare och mer jämlika som en

“startpunkt” i livet varefter egna strävanden avgör en individs position i samhället var den liberala grundtanken. Så länge

konservativa och reaktionära krafter var dominerande i högern sågs liberalismen således som en vänsterteori. Den sågs också i vissa

fall som en mittenideologi. Till höger om liberalerna fanns då, liksom nu, de konservativa och reaktionära ideologierna och

rörelserna. Nationalsocialismen: höger eller vänster? Var befinner sig då nationalsocialismen? Hämtar den kraft av en grundläggande

ekonomisk och kulturell frihets- och jämlikhetstanke? Är den med andra ord en vänsterteori? Svaret ter sig tämligen evident – nej det

är den inte. Nationalsocialismen gjorde ojämlikheten till sin hjärtefråga. I nationen strävade man för att bevara den egna etniciteten

och man förespråkade dess överlägsenhet gentemot andra. I den meningen var den nationella identiteten socialiserad i det att

nationalismen konsoliderades av en gemensam tysk identitet; i ekonomin förespråkades en korporativ klassamarebetesmodell där

samhällsklasserna cementerades och tilldelades strukturella roller som upprätthölls av staten; i privatlivet upphöjdes traditionell

kultur och traditionella könsroller hellre än en progressiv förändring av dessa; i den internationella politiken förespråkades

militaristisk imperialism och så vidare. Nationalsocialismens målsättning var inte att upphäva hierarkier och förtryckande strukturer

men att säkerställa deras existens och armera dem. Bland annat beskriver den ultraliberala anarkokapitalisten Murray Rothbard det vi

diskuterar så här: Fascismen och nazismen var de högerkollektivistiska inrikespolitiska tendensernas logiska slutpunkt. Det har blivit

vanligt bland libertarianer, liksom hos etablissemanget i väst, att betrakta fascismen och kommunismen som i grunden identiska. Men

medan båda system onekligen var kollektivistiska skilde de sig mycket åt, sett till deras socioekonomiska innehåll. Kommunismen

var en verklig revolutionär rörelse som hänsynslöst trängde undan och störtade den gamla styrande eliten medan fascismen tvärtom

cementerade makten hos de gamla härskande klasserna. Fascismen var således en kontrarevolutionär rörelse som frös fast en

uppsättning monopolprivilegier i samhället; kort sagt, fascismen upphöjde den moderna statskapitalismen till gudastatus. Detta var

anledningen till att fascismen var så attraktiv för stora affärsintressen i väst (vilket kommunismen förstås aldrig var) – öppet och

ogenerat så under 1920- och början på 1930-talet. (Murray Rothbard, Left and Right: The Prospects for Liberty) Nazismen är således

en solklar högerideologi, en extrem högerideologi, givet dess grundläggande ideologiska innehåll när det gäller allt från ekonomi till

kultur. Nationalsocialisten talar om “nationalism” där socialisten talar om “internationalism.” Nationalsocialisten talar om

“klassamarbete” där socialisten talar om “klasskamp.” Nationalsocialisten talar om “tradition” där socialisten talar om

“progressivitet.” Nationalsocialisten talar om “den ariska rasens överlägsenhet” där socialisten talar om att “alla människor är

jämlika.” Vi skulle kunna hålla på hur länge som helst men för att korta ner det hela kan vi helt enkelt säga: nazisten säger “höger”

där socialisten säger “vänster.” Bemötande av vanligt förekommande påståenden från modern höger 1. “Det heter ju faktiskt national-

SOCIALISM!” Att en företrädare för en viss ideologi kallar sin egen idé “socialistisk” innebär inte med automatik att den måste

motsvara vad den gör anspråk på att vara. I det här fallet vänsterteori. För att demonstrera vad jag menar tänkte jag att vi applicerar

samma angreppsmetodologi som vi gör med nationalsocialismen men på två andra områden: Nordkoreas officiella namn är

“Demokratiska folkrepubliken Korea”. Vore det alltför långdraget för en politisk analytiker att anta att demokratin i det förhållandet

endast är nominellt? För oss är det därför lika uppenbart att avstyrka Demokratiska Kampucheas anspråk på den demokrati de

uppenbarligen inte förvaltade. Istället kan vi hitta förklaringen till NSDAP:s “socialism” i dåtidens höger. En relativt konventionell

högerkonservativ utlöpare i dåtidens Europa var en sådan som lade stor vikt vid kollektivet, i regel i en nationalistisk och

korporativistisk mening. Joseph de Maistre företrädde en sådan position i den så kallade “kontinentala konservatismen.” Ett annat

exempel hittar vi på hemmaplan i den svenske unghögermannen Rudolf Kjellén (verksam i vad som nu är Moderaterna). Han

förespråkade en form av korporativistisk konservatism grundad i nationalism – vilken han kallade “nationalsocialism.” Termen

socialism hade som begrepp i den kollektivistiska högern en annan mening än termen hade och har i vänstern. I högern syftade den

ofta till att se samhället som en “organism” efter gammal idealistisk konservativ modell där alla delar hänger ihop och bör bevaras så

som de är eller återföras till ett tidigare “mer naturligt” tillstånd; folket och nationen stod i fokus, liksom klassamarbetet,

traditionerna och hierarkierna, i rak motsats till hur termen användes av vänstern. Med den betydelse socialismen har idag och alltid

har haft hos vänstern sedan den moderna socialismens uppkomst kan nazismen således sägas vara ungefär lika mycket socialistisk

som Nordkorea eller Kampuchea är/var demokratiskt. 2. “Stor stat = socialism” Detta är av någon obergriplig anledning ett

återkommande antagande som upprepas gång på gång i diskussionerna om såväl nazism som om socialism och givetvis speciellt i

diskussionerna om ideologiernas eventuella kopplingar till varandra. Men det är ett bakslugt påstående. En stor stat, i meningen

omfattande och/eller inflytelserik sådan, har inte nödvändigtvis med socialism att göra. En socialist kan förespråka en stat med stort

inflytande i samhället. Sådan är till exempel den klassiska socialdemokratin. Men en socialist kan lika gärna frondera staten helt och

fullt vilket ju är anarkisters och många andra frihetliga socialisters hållning. Inom den marxistiska kommunismen ses staten ofta som

ett verktyg för att uppnå måletsättningen “stats- och klasslöst samhälle”. Någon enhetlig eller ens specifik inställning till staten finns

inte inom socialismen. Socialister av olika slag täcker hela spektrat från väldigt stark stat till ingen stat alls. Vad som finns är däremot

progressivitet: om staten ska användas som ett politiskt verktyg så ska den påverka samhället i progressiv riktning. Det är åtminstone

tanken bakom statssocialismen. Hur det översattes i praktiken är en annan sak. I konservatismen och hos reaktionärerna fanns

däremot specifikt i början av 1900-talet ofta ett starkt fokus på staten; staten måste vara stark för att kunna bevara ordningen

samtidigt som den till viss del måste ge efter för allmänna intressen för att kunna vidmakthålla ordningen (för att undvika

revolutioner). Hos de traditionella konservativa och reaktionära hittar vi monarkister som vill att samhället ska styras av en enda

monark och korporativister som ser samhället som en “organism” som måste ledas av en stark korporativ stat där “de bästa” står för

styret (vilket ofta stod i motsats till demokratiskt valda ledare). Här är parallellen till Platons syn på den elitdemokratin tydlig. Det är

således återigen bland de kollektivistiska och nationalistiska reaktionärerna som de flesta beröringspunkterna med

nationalsocialismen och fascismen går att utläsa. Den stora stat som nationalsocialisterna förespråkade och upprätthöll passar som

handen i handsken med andra högerkollektivistiska tankegångar under sent 1800-tal och under 1900-talets första hälft. Det intima

förhållandet var förmodligen också en av anledningarna till att den svenska högerns ungdomsförbund, Sveriges nationella

ungdomsförbund till slut bröt sig loss från moderpartiet (nuvarande Moderaterna) tillsammans med några moderata riksdagsmän och

bildade Sveriges nationella förbund, en organisation som var en öppet pronazistisk rörelse med tillhörande “kamporganisation”,

uniformer och armbindlar. 3. NSDAP ville genomdriva socialistisk politik Detta är ett något mer sofistikerat argument än de två

föregående, men även det saknar stabil grund. Det är sant att det existerade något mer (strikt ekonomiskt) socialistiska element inom

den bredare nazistiska rörelsen men sådana aspirationer eliminerades av Hitler innan de riskerade att konkretiseras. Den socialistiska

ekonomins främsta företrädare inom partiet eliminerades under vad som kommit att bli känt som “de långa knivarnas natt”

tillsammans med stora delar av SA. Inte ens “kvasi-socialistisk” ekonomi med bibehållen rasism, traditionalism och nationalism var

alltså något som Hitler ville tolerera. Istället skulle han betrakta de socialistiska strömningarna som rivaler. Man talade ofta varmt om

jämliket och arbetarnas rätt men verkligheten var en annan. Förutom sänkta löner för de sämst betalda arbetstagarna jobbade även

miljontals människor som slavar i nazistregimens arbets- och koncentrationsläger med en vinst som gick till staten och storkapitalet. I

Fascism och klassherravälde konstaterar Gunnar Gunnarsson att “…Handelsprofitens andel av de tyska nationalinkomsterna steg från

17,4 procent år 1932 till 26,6 procent 1938″ och att “de tyska aktiebolagens kapital steg från 18,75 miljarder riksmark år 1938 till

mer än 29 miljarder vid slutet av 1942”. Det skall då kontrasteras med att “de lägsta lönerna i Hitlertyskland sjönk med mellan 25

och 40 procent (i Italien uppemot 50 procent) åren efter 1933 och att börsvinsterna gick i taket” Realpolitiken var högerpolitik. När

fackliga rättigheter avskaffades kammade storföretagen hemenorma övervinster samtidigt som de lägsta arbetarlönerna blev ännu

lägre. Staten styrdes på ett korporativt vis av NSDAP tillsammans med Tysklands storföretag och ledande kapitalister. De faktiska

reformer som genomfördes knyter naturligt an till den klassiska konservativa tanken om förändring i syfte att bevara ordningen:

genom att erbjuda befolkningen reformistiskt “bröd och skådespel” kunde man hålla fast vid den reella makten och lejonparten av

vinsterna. Vad som fördes var således inte socialistisk politik. Inte heller var det vänsterpolitik i liberal form Det var snarare en

extrem kollektivistisk och nationalistisk högerkonservativ/reaktionär politik i linje med vad man kan förvänta sig av en sådan. Emilia

Princeton, gästskribent Politifonen. Relaterad läsning: Hitlers politiska historia startade efter första världskriget. Under kriget var

Hitler ordonnans och korpral. Vi krigsslutet 1918 tog han anställning i Münchens armédistrikt som spion åt det tyska Riksvärnet, det

som återstod av den tyska armén efter nederlaget. Hitlers uppgift var att spionera på vänstern och fackföreningsrörelsen. Hitlers

första uppdrag var att 1919 överta ledningen för det lilla högerpartiet, Tyska Arbetarpartiet, Deutsche Arbeiterpartei. På partiets

möten hetsade Hitler grovt mot kommunister, socialister, fackföreningsmän och judar. Han var en utomordentlig demagog som kunde

konsten att hetsa upp åhörarna. Han drog till partiet gamla yrkesmilitärer, underbefäl och officerare vilket gav partiet en militär profil.

Hitler tog snart över ledningen av partiet. Han döpte om partiet till Nationalsocialistiska Tyska Arbetarpartiet – NSDAP och antog ett

program som bestod av extremnationalistiska principer och en starkt antisocialistisk, antisemitisk grund. Åren därefter

karakteriserades av stor massarbetslöshet och stor social oro. Hitlers hatpropaganda drog till sig anhängare och partiet växte.

Konfrontation med kommunisterna och socialisterna var ett av partiets mål som alltid stog överst på dagordningen. Hitler gav Ernst

Röhm, en gammal officer, uppdraget att organisera partiets privatarmé SA, Sturmabteilung (stormavdelning), som nazisterna använde

vid attacker mot kommunisternas partimöten och partilokaler

You might also like

- Hitler Was a Socialist: A comparison of NAZI-Socialism, Communism, Socialism, and the United StatesFrom EverandHitler Was a Socialist: A comparison of NAZI-Socialism, Communism, Socialism, and the United StatesNo ratings yet

- The Nazis Were Right-Wing - Part 2Document10 pagesThe Nazis Were Right-Wing - Part 2Maks imilijanNo ratings yet

- Excerpt From The OMINOUS PARALLELS, by Leonard PeikoffDocument6 pagesExcerpt From The OMINOUS PARALLELS, by Leonard Peikoffskalpsolo100% (2)

- Nazism and FascismDocument4 pagesNazism and FascismJayson TasarraNo ratings yet

- Summary Of "The Fascism" By Jover Cervera: UNIVERSITY SUMMARIESFrom EverandSummary Of "The Fascism" By Jover Cervera: UNIVERSITY SUMMARIESNo ratings yet

- Fascism Vs Nazism Ibrahim Noorani: Prepared ByDocument10 pagesFascism Vs Nazism Ibrahim Noorani: Prepared ByEbrahim NooraniNo ratings yet

- Mein Kampf by Adolf Hitler (Book Analysis): Detailed Summary, Analysis and Reading GuideFrom EverandMein Kampf by Adolf Hitler (Book Analysis): Detailed Summary, Analysis and Reading GuideNo ratings yet

- A Nerd's Response to Neo-Fascist Appropriation of Sci-Fi and Fantasy Works for the Purpose of "Triggering Liberals"From EverandA Nerd's Response to Neo-Fascist Appropriation of Sci-Fi and Fantasy Works for the Purpose of "Triggering Liberals"No ratings yet

- ProjectDocument9 pagesProjectapi-649877960No ratings yet

- Sociales 2Document5 pagesSociales 2Isabela ReveloNo ratings yet

- Rise of FascismDocument31 pagesRise of Fascismmartinshehzad100% (1)

- The fight for workers' power: Revolution and counter-revolution in the 20th centuryFrom EverandThe fight for workers' power: Revolution and counter-revolution in the 20th centuryRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Were Nazis FascistsDocument11 pagesWere Nazis FascistsHugãoNo ratings yet

- 31-3 Fascism Rises in EuropeDocument25 pages31-3 Fascism Rises in Europeapi-213462480No ratings yet

- Blackshirts and Reds: Rational Fascism and the Overthrow of CommunismFrom EverandBlackshirts and Reds: Rational Fascism and the Overthrow of CommunismRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (46)

- Examples of TotalitarianismDocument4 pagesExamples of TotalitarianismTeona TurashviliNo ratings yet

- G1 Are Individualist Anarchists Anti-CapitalistDocument47 pagesG1 Are Individualist Anarchists Anti-Capitalistglendalough_manNo ratings yet

- Zackary Petit - Totalitarian Dictators Project Part II Compare and Contrast Totalitarian Dictatorships EssayDocument16 pagesZackary Petit - Totalitarian Dictators Project Part II Compare and Contrast Totalitarian Dictatorships Essayapi-688321007No ratings yet

- Alberto Toscano, The Nightwatchman's Bludgeon - SidecarDocument9 pagesAlberto Toscano, The Nightwatchman's Bludgeon - SidecarMajaMarsenicNo ratings yet

- The Specter of Democracy: What Marx and Marxists Haven't Understood and WhyFrom EverandThe Specter of Democracy: What Marx and Marxists Haven't Understood and WhyNo ratings yet

- Fascism Rises in EuropeDocument25 pagesFascism Rises in Europegamila workNo ratings yet

- Ibarrurai 12Document2 pagesIbarrurai 12Gerald J DowningNo ratings yet

- FascismDocument4 pagesFascismAsad RazaNo ratings yet

- Fascism & Nazism - BS IR - Sem IIIDocument3 pagesFascism & Nazism - BS IR - Sem IIIzulqarnainlaadi1No ratings yet

- Eclipse and Re-emergence of the Communist MovementFrom EverandEclipse and Re-emergence of the Communist MovementRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2)

- "Infamous Decade" In Argentina, 1930-1943: UNIVERSITY SUMMARIESFrom Everand"Infamous Decade" In Argentina, 1930-1943: UNIVERSITY SUMMARIESNo ratings yet

- An Analysis of Fascist Economic TheoryDocument33 pagesAn Analysis of Fascist Economic TheoryskadettleNo ratings yet

- Anarchism Definitions Marshall S ShatzDocument84 pagesAnarchism Definitions Marshall S ShatzrdamedNo ratings yet

- Assignment # 1 Submitted By: F2019266364: Totalitarianism, Form of Government That Theoretically Permits NoDocument3 pagesAssignment # 1 Submitted By: F2019266364: Totalitarianism, Form of Government That Theoretically Permits NoRizwan KhadimNo ratings yet

- How Did The Rise of Nazism and Fascism Lead To World War 2Document6 pagesHow Did The Rise of Nazism and Fascism Lead To World War 2RahimahameedNo ratings yet

- The Quest for Community: A Study in the Ethics of Order and FreedomFrom EverandThe Quest for Community: A Study in the Ethics of Order and FreedomRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (8)

- Toward Socialist America: An Analysis of America's Slide into CollectivismFrom EverandToward Socialist America: An Analysis of America's Slide into CollectivismNo ratings yet

- Rise of The Dictators in The 1920Document16 pagesRise of The Dictators in The 1920krats1976No ratings yet

- The Left/Right ParadigmDocument15 pagesThe Left/Right ParadigmTimothyNo ratings yet

- Fascism vs. NazismDocument3 pagesFascism vs. NazismSkylock12280% (5)

- Communism VS FascismDocument12 pagesCommunism VS Fascismkamran murtazaNo ratings yet

- Nazism and Communism EssayDocument2 pagesNazism and Communism Essayapi-353013978No ratings yet

- Not Regret: The Road To SesfdornDocument5 pagesNot Regret: The Road To SesfdornCarlos AyalaNo ratings yet

- DEMOCRACY The Primacy of Politics Social Democracy and The Making of Europe's Twentieth CenturyDocument30 pagesDEMOCRACY The Primacy of Politics Social Democracy and The Making of Europe's Twentieth CenturyUlisses AlvesNo ratings yet

- Democratic Socialism Encyclopedia of Activism and Social Justice Sage Reference Project (Forthcoming)Document11 pagesDemocratic Socialism Encyclopedia of Activism and Social Justice Sage Reference Project (Forthcoming)Angelo MariNo ratings yet

- The 1956 Draper-Silone DebateDocument26 pagesThe 1956 Draper-Silone DebateMartin ThomasNo ratings yet

- The Seduction of Unreason: The Intellectual Romance with Fascism from Nietzsche to Postmodernism, Second EditionFrom EverandThe Seduction of Unreason: The Intellectual Romance with Fascism from Nietzsche to Postmodernism, Second EditionNo ratings yet

- Otto Strasser and National Socialism GottfriedDocument10 pagesOtto Strasser and National Socialism Gottfriedgiorgoselm100% (1)

- Hal Draper - Karl Marx's Theory of Revolution - V. 5 - War and Revolution (With E. Haberken)Document286 pagesHal Draper - Karl Marx's Theory of Revolution - V. 5 - War and Revolution (With E. Haberken)Rodrigo GonçalvesNo ratings yet

- The Invisible Handcuffs of Capitalism: How Market Tyranny Stifles The Economy by Stunting Workers (PDFDrive)Document359 pagesThe Invisible Handcuffs of Capitalism: How Market Tyranny Stifles The Economy by Stunting Workers (PDFDrive)Maks imilijan100% (1)

- 90 04 13643 6Document272 pages90 04 13643 6Vicente H. MartínezNo ratings yet

- History of Socialism - An Historical Comparative Study of Socialism, Communism, UtopiaDocument1,009 pagesHistory of Socialism - An Historical Comparative Study of Socialism, Communism, UtopiaMaks imilijanNo ratings yet

- Michael Perelman (Auth.) - Steal This Idea - Intellectual Property Rights and The Corporate Confiscation of Creativity-Palgrave Macmillan US (2002)Document263 pagesMichael Perelman (Auth.) - Steal This Idea - Intellectual Property Rights and The Corporate Confiscation of Creativity-Palgrave Macmillan US (2002)PlinioSampaioJr.No ratings yet

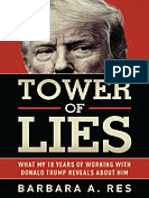

- Tower of Lies What My Eighteen Years of Working With Donald Trump Reveals About Him by Barbara ResDocument227 pagesTower of Lies What My Eighteen Years of Working With Donald Trump Reveals About Him by Barbara ResMaks imilijan100% (1)

- Simon Choat - Marx's Grundrisse PDFDocument236 pagesSimon Choat - Marx's Grundrisse PDFFelipe Sanhueza Cespedes100% (1)

- Dutt - Fascismo e Revolucao SocialDocument207 pagesDutt - Fascismo e Revolucao SocialGabriel Gonçalves MartinezNo ratings yet

- Marcel Van Der Linden - The Cambridge History of Socialism, Volume I 1 (2022, Cambridge University Press) - Libgen - LiDocument688 pagesMarcel Van Der Linden - The Cambridge History of Socialism, Volume I 1 (2022, Cambridge University Press) - Libgen - LiMaks imilijanNo ratings yet

- Criminal Immigrants in Texas: Illegal Immigrant Conviction and Arrest Rates For Homicide, Sexual Assault, Larceny, and Other CrimesDocument8 pagesCriminal Immigrants in Texas: Illegal Immigrant Conviction and Arrest Rates For Homicide, Sexual Assault, Larceny, and Other CrimesLatinos Ready To VoteNo ratings yet

- Fascism (By Scott Nearing)Document61 pagesFascism (By Scott Nearing)Maks imilijanNo ratings yet

- Two Neglected Interviews With Karl MarxDocument27 pagesTwo Neglected Interviews With Karl MarxMaks imilijanNo ratings yet

- "Karl Marx's Realist Critique of Capitalism - Freedom, Alienation, and Socialism" by Paul RaekstadDocument288 pages"Karl Marx's Realist Critique of Capitalism - Freedom, Alienation, and Socialism" by Paul RaekstadMaks imilijan100% (1)

- Newspapers AxisDocument433 pagesNewspapers AxisMaks imilijan100% (1)

- An Economic History of The USSR, 1917-91 by Alec NoveDocument482 pagesAn Economic History of The USSR, 1917-91 by Alec NoveMaks imilijanNo ratings yet

- Human Rights in The Soviet Union by Albert SzymanskiDocument178 pagesHuman Rights in The Soviet Union by Albert SzymanskiMaks imilijanNo ratings yet

- German Ideology - The ManuscriptsDocument402 pagesGerman Ideology - The ManuscriptsMaks imilijanNo ratings yet

- Marxism and Freedom.Document253 pagesMarxism and Freedom.Maks imilijanNo ratings yet

- Nasir Khan-Development of The Concept and Theory of Alienation in Marx's Writings-Solum Forlag (1995)Document294 pagesNasir Khan-Development of The Concept and Theory of Alienation in Marx's Writings-Solum Forlag (1995)Omair Iftikhar100% (2)

- An Analysis of Karl Marx's Capital: A Critique of Political Economy (The Macat Library)Document108 pagesAn Analysis of Karl Marx's Capital: A Critique of Political Economy (The Macat Library)Maks imilijan100% (2)

- Soviet Democracy by Pat SloanDocument294 pagesSoviet Democracy by Pat SloanMaks imilijanNo ratings yet

- Marxs Capital and Global CrisisDocument109 pagesMarxs Capital and Global CrisisMaks imilijanNo ratings yet

- Marx and Engels' 'Communist Manifesto' A Reader's GuideDocument193 pagesMarx and Engels' 'Communist Manifesto' A Reader's GuideMaks imilijan100% (1)

- Marx and EthicsDocument228 pagesMarx and EthicsDmitry BespasadniyNo ratings yet

- Lukacs On Marxism and Human LiberationDocument353 pagesLukacs On Marxism and Human LiberationMaks imilijanNo ratings yet

- Theory of BolshevismDocument64 pagesTheory of BolshevismMaks imilijanNo ratings yet

- Marxian LegacyDocument356 pagesMarxian LegacyMaks imilijanNo ratings yet

- Feenberg, Andrew - Lukács, Marx, and The Sources of Critical TheoryDocument301 pagesFeenberg, Andrew - Lukács, Marx, and The Sources of Critical TheoryMaks imilijanNo ratings yet

- The Marxist Theory of Alienation - George Novack, Ernest Mandel (1973)Document98 pagesThe Marxist Theory of Alienation - George Novack, Ernest Mandel (1973)Keith100% (3)

- A Marxist Philosophy of Language - J.-J.lecercle (Brill-2006)Document246 pagesA Marxist Philosophy of Language - J.-J.lecercle (Brill-2006)Fabiola Rodríguez100% (1)

- Ya Rasool AllahDocument10 pagesYa Rasool AllahEhteshamNo ratings yet

- Judith Butler The Psychic Life of Power Theories in Subjection 1997Document222 pagesJudith Butler The Psychic Life of Power Theories in Subjection 1997lauracqpNo ratings yet

- Anda, BoholDocument2 pagesAnda, BoholSunStar Philippine NewsNo ratings yet

- Divorce by Mutual and Waiver of Caution PeriodDocument17 pagesDivorce by Mutual and Waiver of Caution Periodkhanin lahkarNo ratings yet

- Flightcar Moves To South City: Oobbaammaa Iinn BbaayyDocument36 pagesFlightcar Moves To South City: Oobbaammaa Iinn BbaayySan Mateo Daily JournalNo ratings yet

- Fil 40 Wika Kultura LipunanDocument2 pagesFil 40 Wika Kultura LipunanNona RachoNo ratings yet

- Hearty Welcome To AllDocument15 pagesHearty Welcome To AllPreethi GopalanNo ratings yet

- Iptv Urls For NudeDocument13 pagesIptv Urls For Nudewaseem kingNo ratings yet

- Brandis SpeechDocument2 pagesBrandis SpeechMax DonaireNo ratings yet

- MACN-R999999999 - Declaration of Trust of The Moorish National Republic Federal GovernmentDocument1 pageMACN-R999999999 - Declaration of Trust of The Moorish National Republic Federal GovernmentSharon T Gale Bey100% (6)

- Sinophone Studies: A Critical ReaderDocument17 pagesSinophone Studies: A Critical ReaderColumbia University Press100% (2)

- Objective, Model Paper, Islamiat, 2020 PDFDocument4 pagesObjective, Model Paper, Islamiat, 2020 PDFMuhammad Khalid Mehmood SialviNo ratings yet

- Excise Duties-Part I Alcohol enDocument17 pagesExcise Duties-Part I Alcohol enKaty SosNo ratings yet

- Pancasila Sebagai Sistem EtikaDocument5 pagesPancasila Sebagai Sistem EtikaKawit WangiNo ratings yet

- Rights in Intimate Relationships PDFDocument163 pagesRights in Intimate Relationships PDFPartners for Law in DevelopmentNo ratings yet

- 185 91 1 PBDocument14 pages185 91 1 PBJane Alambra AlombroNo ratings yet

- Baltimore Afro-American Newspaper, April 16, 2011Document16 pagesBaltimore Afro-American Newspaper, April 16, 2011The AFRO-American NewspapersNo ratings yet

- Joint Survey / Damage Assessment-Monsoon Flood 2022 Taluka RatoderoDocument105 pagesJoint Survey / Damage Assessment-Monsoon Flood 2022 Taluka RatoderoYousof Khan100% (1)

- HansIndia Ap PDFDocument14 pagesHansIndia Ap PDFSatyendraYadavNo ratings yet

- Lauren Berlant and Michael Warner - What Does Queer Theory Teach Us About XDocument7 pagesLauren Berlant and Michael Warner - What Does Queer Theory Teach Us About XMaría Laura GutierrezNo ratings yet

- The Expansion of The Christian KingdomsDocument5 pagesThe Expansion of The Christian KingdomsAlexiaSeleniaNo ratings yet

- Gregorio HonasanDocument3 pagesGregorio HonasanThe Movement for Good Governance (MGG)No ratings yet

- The Politics of Working Class Communism in Greece, 1918-1936Document296 pagesThe Politics of Working Class Communism in Greece, 1918-1936Stefan OzrenNo ratings yet

- Hope in The Age of CollapseDocument16 pagesHope in The Age of CollapseelpadrinoleoNo ratings yet

- World Watch List 2010, Open DoorsDocument16 pagesWorld Watch List 2010, Open DoorsOpen DoorsNo ratings yet

- What's Happening in Zimbabwe?: Important Elections Took Place in Zimbabwe in Southern Africa On 30 July 2018Document6 pagesWhat's Happening in Zimbabwe?: Important Elections Took Place in Zimbabwe in Southern Africa On 30 July 2018EriqNo ratings yet

- Sultaniyya - Abdalqadir As-SufiDocument137 pagesSultaniyya - Abdalqadir As-SufiJabal Sab KadyrovNo ratings yet

- AM No 02 8 13 SCDocument2 pagesAM No 02 8 13 SCKristela AdraincemNo ratings yet

- Gender StereotypesDocument6 pagesGender Stereotypesapi-273242189No ratings yet

- Sovereignty: Assistant Professor Hidayatullah National Law University Raipur, ChhattisgarhDocument15 pagesSovereignty: Assistant Professor Hidayatullah National Law University Raipur, ChhattisgarhOnindya MitraNo ratings yet