Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Journal Pone 0280213

Uploaded by

Kasep PisanOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Journal Pone 0280213

Uploaded by

Kasep PisanCopyright:

Available Formats

PLOS ONE

REGISTERED REPORT PROTOCOL

Identifying the key characteristics of a

culturally safe mental health service for

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples:

A qualitative systematic review protocol

Helen Milroy1,2, Shraddha Kashyap ID2*, Jemma R. Collova ID2, Monique Platell3,

Graham Gee4,5, Jeneva L. Ohan6

a1111111111 1 UWA Medical School, University of Western Australia, Perth, Western Australia, Australia, 2 Bilya Marlee

a1111111111 School of Indigenous Studies, University of Western Australia, Perth, Western Australia, Australia, 3 School

a1111111111 of Allied Health, University of Western Australia, Perth, Western Australia, Australia, 4 Murdoch Children’s

a1111111111 Research Institute, The Royal Children’s Hospital, Parkville, Victoria, Australia, 5 Mebourne School of

a1111111111 Psychological Sciences, University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia, 6 School of Psychological

Science, University of Western Australia, Perth, Western Australia, Australia

This is a Registered Report and may have * shraddha.kashyap@uwa.edu.au

an associated publication; please check the

article page on the journal site for any

related articles.

Abstract

OPEN ACCESS

Citation: Milroy H, Kashyap S, Collova JR, Platell Background

M, Gee G, Ohan JL (2023) Identifying the key

Mental health inequities between Indigenous and non-Indigenous populations are well docu-

characteristics of a culturally safe mental health

service for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander mented. There is growing recognition of the role that culturally safety plays in achieving equi-

peoples: A qualitative systematic review protocol. table outcomes. However, a clear understanding of the key characteristics of culturally safe

PLoS ONE 18(1): e0280213. https://doi.org/ mental health care is currently lacking. This protocol outlines a qualitative systematic review

10.1371/journal.pone.0280213

that aims to identify the key characteristics of culturally safe mental health care for Aborigi-

Editor: Peter Edwards, Manaaki Whenua - nal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, at the individual, service, and systems level. This

Landcare Research, NEW ZEALAND

knowledge will improve the cultural safety of mental health care provided to Indigenous peo-

Received: August 2, 2022 ples, with a focus on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples in Australia.

Accepted: December 21, 2022

Published: January 12, 2023

Methods and expected outputs

Copyright: © 2023 Milroy et al. This is an open

access article distributed under the terms of the Through a review of academic, grey, and cultural literature, we will identify the key charac-

Creative Commons Attribution License, which teristics of culturally safe mental health care for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peo-

permits unrestricted use, distribution, and ples in Australia. We will consider the characteristics of culturally safe care at the individual

reproduction in any medium, provided the original

practitioner, service, and systems levels.

author and source are credited.

Data Availability Statement: This is a protocol for

a systematic review, and so there is no data.

Prospero registration number

Funding: This review was funded by the Million

CRD42021258724.

Minds Research Fund, supported by the Medical

Research Future Fund [grant number

APP1178803], Chief Investigators on this grant

include HM and GG. https://www.health.gov.au/

PLOS ONE | https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0280213 January 12, 2023 1 / 10

PLOS ONE What makes a culturally safe mental health service for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples?

initiatives-and-programs/medical-research-future- Introduction

fund The funders had not and will not have a role in

study design, data collection and analysis, decision Prior to colonisation, Indigenous peoples across the globe lived healthy lives, and their mental

to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. health and wellbeing flourished for thousands of years. However, today, many Indigenous peo-

Competing interests: The authors have declared

ples face disproportionate rates of mental health challenges as the result of intergenerational

that no competing interests exist. trauma and the continuing experience of colonising practices and attitudes [1–4]. The contrib-

uting role of mental health services and systems to mental health outcomes is under increasing

scrutiny by mental health professionals, service providers, and service users [5–7]. In turn,

there is growing consensus regarding the need for culturally safe mental health care [6, 8], par-

ticularly within the Australian policy context [9]. However, there is a lack of clarity regarding

what makes a mental health service culturally safe. This proposed systematic review aims to

identify the key characteristics of culturally safe mental health care.

The review will focus specifically on cultural safety for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander

peoples, the First Nations people of Australia. The decision to focus on Aboriginal and Torres

Strait Islander peoples was made for several reasons. First, it is not clear whether the character-

istics that contribute to cultural safety for one Indigenous population would transfer to all

other Indigenous populations. Therefore, this review provides a crucial and localized founda-

tion on which future research can build upon. Second, Australia is among the leading coun-

tries driving a culturally safe healthcare agenda [10–12], therefore providing a good candidate

to be a focus of this review. Further, a local focus enables the scope of this review to be feasible

with the addition of grey literature to thoroughly examine, where a substantial proportion of

Indigenous health research is published [13]. The review process is governed by Aboriginal

researchers, and it will privilege Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander literature and cultural

knowledge, including forms of published stories, interviews, videos as this essential form of

knowledge has been historically excluded.

Cultural safety

The term cultural safety, in the context of healthcare service provision, was first coined follow-

ing observations of inequity in mainstream healthcare services in Aotearoa, New Zealand [14,

15]. More recently, this term has been applied to describe disparities in healthcare for Aborigi-

nal and Torres Strait Islander peoples in Australia, where unsafe practices are those which

diminish, demean, and/or disempower the cultural identity and wellbeing of an individual

[16]. Here, we provide a description of how cultural safety is determined, which was adopted

following public consultation within Australia, noting that the concept of cultural safety can be

applied to any Indigenous group;

“Cultural safety is determined by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander individuals, families

and communities. Culturally safe practise is the ongoing critical reflection of health practi-

tioner knowledge, skills, attitudes, practising behaviours and power differentials in delivering

safe, accessible and responsive healthcare free of racism”

[17].

Terms such as cultural safety, awareness, and competency are often used interchangeably

and inconsistently [18]. However, there are some important differences between them [18–21]

and this description highlights some key features which differentiate cultural safety from other

similar concepts. Broadly, cultural safety is viewed as a step beyond cultural awareness and

competency, because it requires more than an understanding of other cultures, and more than

a set of competent-related skills. Instead, a defining feature of cultural safety, is its emphasis on

recognising and responding to the critical role of power. Cultural safety for service users

PLOS ONE | https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0280213 January 12, 2023 2 / 10

PLOS ONE What makes a culturally safe mental health service for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples?

requires healthcare professionals and organisations to reflect on and critique taken for granted

power structures, and a willingness to challenge one’s own culture, history, and privilege [18].

Importantly, cultural safety can only ever be determined by the user of a service [22]. In this

context, cultural safety as a concept incorporates the idea of a changed power structure, where

the power is transferred to the service user [23]. In short, cultural safety is about ensuring as

far as possible, the safe journey through services and systems to achieve equitable health out-

comes regardless of one’s cultural background.

Cultural safety in mental health services

To date, reviews of cultural safety have been mostly considered in the general context of health

care [18, 24], as opposed to mental health care specifically. For example, there have been

reviews about culturally safe approaches in palliative care [25], diabetes [26], and health care

[27] for Indigenous populations around the globe.

Cultural safety is especially important within the context of mental health services, where

there are several additional complexities. For example, experiences of mental health and well-

being are shaped by culture. Culture shapes understandings of the nature and causes of dis-

tress, the decision to seek help for distress, the kind of support that people seek, the degree of

discrimination they may face, and the way diagnostic categories are constructed [28–33]. Con-

sequently, failing to provide care that considers another’s culture can cause serious harm. For

example, in some Indigenous cultures it is not unusual to experience the voices of ancestors,

whereas within the Western psychiatric diagnostic system hearing voices is classified as a

symptom of psychosis. Understanding whether this is a cultural phenomenon or a serious

mental health disorder with a cultural dimension is critical to providing appropriate care [34].

In this context, a service which privileges Western knowledges and excludes Indigenous

knowledges could potentially fail to provide culturally, and clinically safe mental health care

practices, with detrimental consequences.

In Australia, the importance of cultural safety is reflected in guidelines for the Royal Austra-

lian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists [35], accreditation standards of the Australian

Medical Council [36], and national mental health policy frameworks [9], and health targets

[12], specifically for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. However, despite growing

national support for cultural safety, there is currently a lack of clarity and evidence regarding

how cultural safety in mental health care can be achieved. Many mainstream mental health ser-

vices fail to adequately support cultural safety [6]. Many mental health practitioners have a

limited understanding of cultural safety, and do not recognise the relationship between histori-

cal events, intergenerational trauma, racism, and contemporary health inequities [6]. Thus,

although the importance of cultural safety is well articulated, there is ambiguity surrounding

the key characteristics which would promote or hinder cultural safety in practice.

The systematic review

This systematic review aims to identify the key characteristics of culturally safe mental health

care at the practitioner/service/system level, privileging the perspectives of Aboriginal and

Torres Strait Islander peoples. When working with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander ser-

vice users, a recent framework highlighted three principles or Aboriginal ways of Being, Know-

ing, and Doing [37, 38]. It is also important that cultural safety is embedded at the individual

practitioner level, service level, and systems level. In this context, service providers must con-

sider what they need to know, be, and do at individual, service and systems levels to provide

culturally safe care. In our review, we will therefore consider the evidence for cultural safety at

each of these levels, whenever possible.

PLOS ONE | https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0280213 January 12, 2023 3 / 10

PLOS ONE What makes a culturally safe mental health service for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples?

Consistent with Indigenous research methodologies [39], a meta-synthesis approach is

favourable as it enables the synthesis of qualitative studies on a topic in order to identify key

themes and concepts [40]. Our review will differ to previous similar reviews [41] in that it will

specifically focus on cultural safety as opposed to competency, as well as privilege the voices of

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

In line with best practice guidelines [42] this systematic review protocol is registered with

the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO:

CRD42021258724). We undertook a preliminary search of databases (PROSPERO, PubMed,

SCOPUS), and did not identify any existing or ongoing systematic reviews on the topic.

Methods

The methodology of this qualitative systematic review (herein, meta-synthesis), was informed

by the Joanna Briggs Institute Manual for Evidence Synthesis [43]. The structure of this proto-

col was based on the Qualitative Systematic Review protocol, using a critical and interpretive

approach to synthesis and meta-aggregation [43].

Inclusion criteria

Types of participants. This review will focus on Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander

peoples who have accessed mental health services, as well as carers, family members, and com-

munity members of the service users. There will be no restrictions on age or gender.

We will include literature published in the past 30 years (1992–2022). We describe Level 1

evidence as studies which either demonstrate improvements to cultural safety, or articles

where factors which would improve cultural safety are described by Aboriginal and/or Torres

Strait Islander service users (as well as carers, and/or community members of service users) of

mental health services.

We consider Level 2 evidence as academic and grey literature which describe the character-

istics of cultural safety (e.g., literature published by relevant Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait

Islander-led organisations and services, and government policy documents). This also includes

commentary, editorials, articles, and opinion pieces describing health professionals’ views of

culturally safe mental health services.

Sitting alongside these two levels of evidence, we will include cultural knowledge to incor-

porate broader knowledges and privilege Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander wisdom (see

Table 1).

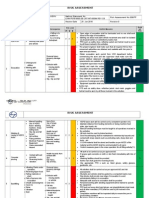

Table 1. Sources of evidence for the systematic review.

Level 1 Evidence Level 2 Evidence Cultural Knowledge

Peer-reviewed studies (qualitative) Published texts (including peer- Sources of cultural knowledge in

which evaluate how culturally safe a reviewed and grey literature) which various forms (e.g., written texts,

mental health service delivery was, or describe the characteristics of cultural audio recordings, video

those which describe the key safety in mental health interventions recordings). Because this literature

characteristics of what would make, i.e., where components of a culturally comes from a different paradigm,

or what made the experience safe mental health service can be we will present this side by side

culturally safe. Importantly, whether extracted from a text. Evidence may with other forms of evidence, with

or not the service was culturally safe include Reports, Training guides, Any the intent of equal positioning and

must come from the perspective of other published texts relevant to not comparison.

the service user. Evidence may include culturally safe mental health care for Evidence may include knowledge

evaluation studies with qualitative Indigenous peoples. published from Cultural Healers,

data. Exclude: Literature reviews, book Elders, mental health service users.

chapters, existing frameworks as in

[44], to focus on ‘raw data’.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0280213.t001

PLOS ONE | https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0280213 January 12, 2023 4 / 10

PLOS ONE What makes a culturally safe mental health service for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples?

We will exclude the following: literature reviews, book chapters, and existing frameworks as

in [44], to focus on ‘raw data’.

We will only conduct forward searches for papers which are included in the final review.

Phenomena of interest. The characteristics of a mental health intervention or service

delivery which make it culturally safe.

Because the level of cultural safety of any mental health service is determined by the service

user (as opposed to the service provider); see, for example, the definition of cultural safety

according to the Australian Health Practitioner Registration Agency (AHPRA) [45]. Services

or interventions will be considered culturally safe if they have been described as such by service

users (or by carers/community members of the service user). In the literature to be reviewed,

the term ‘cultural safety’ may not necessarily be used, however we will consider a service or

intervention culturally safe if it is described in a way that is aligned with the definition of cul-

tural safety used in this protocol [17].

Context. We will review any published intervention or service delivery which identifies,

evaluates, or describes cultural safety (or similar, via a qualitative methodology; see search

strategy) and designed to support the mental health or wellbeing of service users. For example,

any inpatient or outpatient service delivery, mental health service, or psychiatric, psychologi-

cal, psychosocial, or Social and Emotional Wellbeing intervention.

This review will consider studies that focus on qualitative data which describe the experi-

ences or describe the effects of the experiences of cultural safety when engaging with mental

health services [43]. In Table 1, the terms Level 1 and 2 types of evidence distinguish between

peer-reviewed studies with an evaluation focus and other published texts with a descriptive

focus.

Search strategy

The following search terms will be used and adapted appropriately for each information

source:

(Australia� and (Indigenous or Aboriginal or “Torres Strait Islander” or “First Nations” and

“Cultur� Safe� ”or “Cultur� Security” or “Cultur� Appropriat� ” or “Cultur� Respons� ” or

“Cultural Framework”) and (“mental health” or Psychiatr� or Psycholog� or Psychosoc� or

“social and emotional wellbeing” or suicid� ) and (treatment or intervention or care or ther-

ap� or service or program or course or evaluation or trial)).

These search terms were developed and refined after preliminary searches across various

databases, and a review of the key terms used in relevant literature. The key search terms iden-

tified from this method also align with the search strategy of a recent systematic review into

cultural competency in the general context of healthcare (Clifford et al., 2015), confirming

these terms are appropriate for our review. To be conservative, we include several search terms

relating to cultural safety (e.g. cultural appropriateness, cultural responsiveness) given the

inconsistent use of these terms. We will limit data to the past 30 years (1992–2022) and include

sources which are in English or translated to English.

Information sources

• PubMed, Cinahl Plus, SCOPUS, Web of Science, PsychInfo, EMBASE, Medline, Proquest,

Informit, APAIS-ATSIS, and ATSIHEALTH.

• Gray Literature will be accessed from:

PLOS ONE | https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0280213 January 12, 2023 5 / 10

PLOS ONE What makes a culturally safe mental health service for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples?

• Gray literature databases (e.g., https://guides.library.cornell.edu/evidence-synthesis/gray-

literature), Department of Health websites, government websites, Google, Google Scholar,

Open Science Framework, Health Info Net, Grey.net.

• Search for unpublished studies will include the National Aboriginal Torres Strait Islander

Health Worker Association (NATSIHWA) website (https://www.naatsihwp.org.au)

• Hand searches of the reference lists of selected articles.

• Books, videos, and other forms of publicly accessible knowledge published by Cultural Heal-

ers. These will be accessed by contacting Indigenous academics, organisations and publish-

ing houses.

Study selection and records

Following the search, all identified citations will be loaded into Endnote Version X9 as the

mechanism for data management.

Selection process

Selection will entail three stages:

1. Screen titles for relevance

Two researchers will screen titles based on their relevance to the research question. For

example, we will examine titles containing terms relating to mental health or social and

emotional wellbeing (including terms relating to any psychological distress, stress, depres-

sion, anxiety, substance abuse, post-traumatic stress disorder, or suicide, and terms used in

local languages to refer to mental health and spirit e.g., lyarn, mirin), and cultural safety (or

similar, see search terms for details).

2. Screen abstracts for relevance

Abstracts will then be assessed based on their relevance to the research question by the

same two researchers, (i.e., does the article discuss the characteristics of culturally safe men-

tal health services).

3. Screen full texts for relevance

At this stage of the selection process, three researchers will review full texts and decide on

which texts to include in the review. Number and reasons for exclusion of full text studies

that do not meet the inclusion criteria will be recorded and reported in the systematic

review, following the PRISMA guidelines, any discrepancies will be discussed and/or mod-

erated by the third researcher, as described above. If discrepancies remain, the team will

seek guidance from a fourth researcher, who will be a senior Aboriginal member of the

team [43].

Potentially relevant studies will be retrieved in full and their citation details imported into

the QSR International’s NVivo 12 qualitative data analysis software (released in March 2020).

Data extraction

Qualitative data will be extracted by two researchers from papers included in the review using

the standardized data extraction tool from JBI SUMARI by two independent reviewers. The

data extracted will include specific details about the populations, context, culture, geographical

location, study methods and the phenomena of interest relevant to the review question and

specific objectives. Findings, and their illustrations, will be extracted and assigned a level of

PLOS ONE | https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0280213 January 12, 2023 6 / 10

PLOS ONE What makes a culturally safe mental health service for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples?

credibility [43]. The accuracy of data extraction will be verified by the two researchers extract-

ing the information.

Quality and risk of bias assessment for eligible studies

Quality and risk of bias will first be assessed by two independent reviewers according to the

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Quality Appraisal Tool [46]. This tool was developed by

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, for the purposes of systematic and scoping

reviews [46]. The tool consists of 14 questions, and assesses the quality of health research from

an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander perspective [46]. This tool will be used to ensure that

studies are culturally informed, i.e., researchers followed the appropriate community consulta-

tion and co-design processes, and therefore the research is of relevance to Indigenous peoples.

We will report on the quality of the studies included and consider the exclusion of studies

based on this criterion (e.g., if a study fails this quality check).

Authors of papers will be contacted to request missing or additional data for clarification,

where required. The results of critical appraisal will be reported in narrative form and in a

table [43].

Data synthesis and integration

Data in this review will first be synthesised using a thematic analysis approach. We will then

group themes according to a Framework Synthesis method, whenever possible, following the

IAHA framework for Culturally Responsive practice, i.e., doing, being & knowing (as well as

any other factors which are identified during the course of the review). We chose this frame-

work as it was developed by the Indigenous Allied Health Association, and was developed to

assess mental health outcomes from an Indigenous perspective.

Ethical considerations

This research is designed and led by Aboriginal researchers and clinicians. All members of the

research team (including non-Indigenous team members) will follow the guidance of cultural

protocols in support of Aboriginal data sovereignty, research governance and community

safety [47]. Cultural protocols referred to here include ethical guidelines for conducting

research with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples as set out by the National Health

and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) of Australia [47], as well as protocols determined by

the Aboriginal leadership team. Interpretation of findings for the review will be supervised by

a team of Aboriginal researchers to ensure that the voices and worldviews of Aboriginal and

Torres Strait Islander peoples are privleged.

Supporting information

S1 Checklist. PRISMA-P 2015 checklist.

(PDF)

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the Aboriginal research leadership and governance team who guided this

review and wider project (https://timhwb.org.au/).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Helen Milroy.

PLOS ONE | https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0280213 January 12, 2023 7 / 10

PLOS ONE What makes a culturally safe mental health service for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples?

Supervision: Helen Milroy, Graham Gee, Jeneva L. Ohan.

Writing – original draft: Shraddha Kashyap.

Writing – review & editing: Helen Milroy, Shraddha Kashyap, Jemma R. Collova, Monique

Platell, Graham Gee, Jeneva L. Ohan.

References

1. King M, Smith A, Gracey M. Indigenous health part 2: the underlying causes of the health gap. The lan-

cet. 2009; 374(9683):76–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60827-8 PMID: 19577696

2. Mitchell T, Arseneau C. Colonial trauma: complex, continuous, collective, cumulative and compounding

effects on the health of Indigenous peoples in Canada and beyond. International Journal of Indigenous

Health. 2019; 14(2):74–94.

3. Zubrick SR, Shepherd CCJ, Dudgeon P, Gee G, Paradies Y, Scrine C, et al. Social determinants of

social and emotional wellbeing. Working together: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander mental health

and wellbeing principles and practice. 2014; 2:93–112.

4. Sherwood J. Colonisation–It’s bad for your health: The context of Aboriginal health. Contemporary

nurse. 2013; 46(1):28–40. https://doi.org/10.5172/conu.2013.46.1.28 PMID: 24716759

5. Saxena S, Thornicroft G, Knapp M, Whiteford H. Resources for mental health: scarcity, inequity, and

inefficiency. The lancet. 2007; 370(9590):878–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61239-2

PMID: 17804062

6. McGough S, Wynaden D, Wright M. Experience of providing cultural safety in mental health to Aborigi-

nal patients: A grounded theory study. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing. 2018; 27(1):204–

13. https://doi.org/10.1111/inm.12310 PMID: 28165178

7. Molloy L, Lakeman R, Walker K, Lees D. Lip service: Public mental health services and the care of

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing. 2018; 27

(3):1118–26. https://doi.org/10.1111/inm.12424 PMID: 29280272

8. Auger M, Crooks CV, Lapp A, Tsuruda S, Caron C, Rogers BJ, et al. The essential role of cultural safety

in developing culturally-relevant prevention programming in First Nations communities: Lessons

learned from a national evaluation of Mental Health First Aid First Nations. Evaluation and program

planning. 2019; 72:188–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2018.10.016 PMID: 30391824

9. Commonwealth of Australia. National strategic framework for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peo-

ples’ mental health and social and emotional wellbeing 2017–2023,. Canberra2017.

10. Commonwealth of Australia. The fifth national mental health and suicide prevention plan 2017. https://

www.health.gov.au/health-topics/mental-health-and-suicide-prevention/what-were-doing-about-

mental-health?utm_source=health.gov.au&utm_medium=callout-auto-custom&utm_campaign=

digital_transformation.

11. Commonwealth of Australia. National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Plan 2021–2031. In:

Health Do, editor. 2021.

12. Commonwealth of Australia. National Agreement on Closing the Gap. In: Department of the Prime Min-

ister and Cabinet, editor. 2020.

13. Derrick GE, Hayen A, Chapman S, Haynes AS, Webster BM, Anderson I. A bibliometric analysis of

research on Indigenous health in Australia, 1972–2008. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public

Health. 2012; 36(3):269–73. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1753-6405.2011.00806.x PMID: 22672034

14. Elvidge E, Paradies Y, Aldrich R, Holder C. Cultural safety in hospitals: validating an empirical measure-

ment tool to capture the Aboriginal patient experience. Aust Health Rev. 2020; 44(2):205–11. https://

doi.org/10.1071/AH19227 PMID: 32213274

15. Ramsden I. Cultural safety in nursing education in Aotearoa. Nurs Prax N Z. 1993; 8(3):4–10.

16. Clear G. A re-examination of cultural safety: A national imperative. Nursing Praxis in New Zealand.

2008; 24(2):2–5.

17. AHPRA. Report on findings from the public consultation on the definition of ‘cultural safety’ for use within

the National Scheme. Melbourne, VIC.; 2019.

18. Curtis E, Jones R, Tipene-Leach D, Walker C, Loring B, Paine S-J, et al. Why cultural safety rather than

cultural competency is required to achieve health equity: a literature review and recommended defini-

tion. International journal for equity in health. 2019; 18(1):1–17.

19. Darroch F, Giles A, Sanderson P, Brooks-Cleator L, Schwartz A, Joseph D, et al. The United States

does CAIR about cultural safety: Examining cultural safety within Indigenous health contexts in Canada

PLOS ONE | https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0280213 January 12, 2023 8 / 10

PLOS ONE What makes a culturally safe mental health service for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples?

and the United States. Journal of Transcultural Nursing. 2017; 28(3):269–77. https://doi.org/10.1177/

1043659616634170 PMID: 26920574

20. Milne T, Creedy D, West R. Development of the Awareness of Cultural Safety Scale: A pilot study with

midwifery and nursing academics. Nurse Education Today. 2016; 44:20–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.

nedt.2016.05.012 PMID: 27429325

21. Brascoupé S, Waters C. Cultural safety exploring the applicability of the concept of cultural safety to

aboriginal health and community wellness. International Journal of Indigenous Health. 2009; 5(2):6–41.

22. Papps E, Ramsden I. Cultural safety in nursing: The New Zealand experience. International Journal for

Quality in Health Care. 1996; 8(5):491–7. https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/8.5.491 PMID: 9117203

23. Robinson K, Kearns R, Dyck I. Cultural safety, biculturalism and nursing education in Aotearoa/New

Zealand. Health & Social Care in the Community. 1996; 4(6):371–80.

24. Laverty M, McDermott DR, Calma T. Embedding cultural safety in Australia’s main health care stan-

dards. The Medical Journal of Australia. 2017; 207(1):15–6. https://doi.org/10.5694/mja17.00328

PMID: 28659104

25. Schill K, Caxaj S. Cultural safety strategies for rural Indigenous palliative care: a scoping review. BMC

palliative care. 2019; 18(1):1–13.

26. Tremblay M-C, Graham J, Porgo TV, Dogba MJ, Paquette J-S, Careau E, et al. Improving cultural

safety of diabetes care in Indigenous populations of Canada, Australia, New Zealand and the United

States: a systematic rapid review. Canadian Journal of Diabetes. 2020; 44(7):670–8. https://doi.org/10.

1016/j.jcjd.2019.11.006 PMID: 32029402

27. Clifford A, McCalman J, Bainbridge R, Tsey K. Interventions to improve cultural competency in health

care for Indigenous peoples of Australia, New Zealand, Canada and the USA: a systematic review.

International Journal for Quality in Health Care. 2015; 27(2):89–98. https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/

mzv010 PMID: 25758442

28. Abdullah T, Brown TL. Mental illness stigma and ethnocultural beliefs, values, and norms: An integrative

review. Clinical psychology review. 2011; 31(6):934–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2011.05.003

PMID: 21683671

29. Carpenter-Song E, Chu E, Drake RE, Ritsema M, Smith B, Alverson H. Ethno-cultural variations in the

experience and meaning of mental illness and treatment: implications for access and utilization. Trans-

cultural Psychiatry. 2010; 47(2):224–51. https://doi.org/10.1177/1363461510368906 PMID: 20603387

30. Hwang W-C, Myers HF, Abe-Kim J, Ting JY. A conceptual paradigm for understanding culture’s impact

on mental health: The cultural influences on mental health (CIMH) model. Clinical psychology review.

2008; 28(2):211–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2007.05.001 PMID: 17587473

31. Hwang W-C. The psychotherapy adaptation and modification framework: Application to Asian Americans.

American Psychologist. 2006; 61(7):702. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.61.7.702 PMID: 17032070

32. Lopez SA. Culture as an influencing factor in adolescent grief and bereavement. The prevention

researcher. 2011; 18(3):10–4.

33. WHO. Culture and reform of mental health care in central and eastern Europe: Cultural Contexts of

Health and Well-being. Klecany, Czechia; 2017.

34. Parker R, Milroy H. Schizophrenia and related psychosis in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

Aboriginal and Islander Health Worker Journal. 2003; 27(5):17.

35. The Royal Australian & New Zealand College of Psychiatrists. Position Statement: Cultural safety 2021.

https://www.ranzcp.org/news-policy/policy-and-advocacy/position-statements/cultural-safety.

36. Australian Medical Council. Accreditation of specialist medical colleges and their programs of study

2015. https://www.medicalboard.gov.au/Accreditation/Specialist-medical-colleges.aspx.

37. IAHA. Cultural Responsiveness in Action: An IAHA Framework. IAHA Australia: Indigenous Allied

Health Australia; 2019.

38. Martin K, Mirraboopa B. Ways of knowing, being and doing: A theoretical framework and methods for

indigenous and indigenist re-search. Journal of Australian studies. 2003; 27(76):203–14.

39. Bessarab D, Ng’Andu B. Yarning about yarning as a legitimate method in Indigenous research. Interna-

tional Journal of Critical Indigenous Studies. 2010; 3(1):37–50.

40. Thorne S. Data analysis in qualitative research. Evidence-Based Nursing. 2000; 3:68–70.

41. Bhui K, Warfa N, Edonya P, McKenzie K, Bhugra D. Cultural competence in mental health care: a

review of model evaluations. BMC health services research. 2007; 7(1):1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/

1472-6963-7-15 PMID: 17266765

42. Shamseer L, Moher D, Clarke M, Ghersi D, Liberati A, Petticrew M, et al. Preferred reporting items for

systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: elaboration and explanation. BMJ.

2015; 350:g7647. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.g7647 PMID: 25555855

PLOS ONE | https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0280213 January 12, 2023 9 / 10

PLOS ONE What makes a culturally safe mental health service for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples?

43. Aromataris E, Munn Z. JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis. Joanna Briggs Institute; 2020.

44. Jennings W, Bond C, Hill PS. The power of talk and power in talk: a systematic review of Indigenous

narratives of culturally safe healthcare communication. Australian Journal of Primary Health. 2018; 24

(2):109–15. https://doi.org/10.1071/PY17082 PMID: 29490869

45. Agency AHPR. The National Scheme’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health and Cultural Safety

Strategy 2020–2025 Online: AHPRA; 2020. file://uniwa.uwa.edu.au/userhome/staff6/00059986/Down-

loads/National-Scheme-s-Aboriginal-and-Torres-Strait-Islander-Health-and-Cultural-Safety-Strategy-

2020-2025.PDF.

46. Harfield S, Pearson O, Morey K, Kite E, Canuto K, Glover K, et al. Assessing the quality of health

research from an Indigenous perspective: the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander quality appraisal

tool. BMC medical research methodology. 2020; 20:1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-020-00959-3

PMID: 32276606

47. National Health and Medical Research Council. Ethical conduct in research with Aboriginal and Torres

Strait Islander peoples and communities: Guidelines for researchers and stakeholders. Canberra:

Commonwealth of Australia; 2018.

PLOS ONE | https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0280213 January 12, 2023 10 / 10

You might also like

- Healing Across Cultures: Pathways to Indigenius Health EquityFrom EverandHealing Across Cultures: Pathways to Indigenius Health EquityNo ratings yet

- Indigenous Cultural Training For Health Workers in AustraliaDocument11 pagesIndigenous Cultural Training For Health Workers in AustraliaLe HuyNo ratings yet

- Measuring Social and Emotional Wellbeing in Aboriginal Youth Using Strong Souls: A Rasch Measurement ApproachDocument18 pagesMeasuring Social and Emotional Wellbeing in Aboriginal Youth Using Strong Souls: A Rasch Measurement ApproachMares InliwanNo ratings yet

- 1-s2.0-S1326020023000547-main (1)Document10 pages1-s2.0-S1326020023000547-main (1)Neal TorwaneNo ratings yet

- Assessment 3Document9 pagesAssessment 3Teliah ThyssenNo ratings yet

- Articulo Nuevo TEAFDocument14 pagesArticulo Nuevo TEAFyury urregoNo ratings yet

- Western Notions of Informed Consent and Indigenous Cultures: Australian Findings at The InterfaceDocument11 pagesWestern Notions of Informed Consent and Indigenous Cultures: Australian Findings at The InterfaceJanet YauNo ratings yet

- Promote AboDocument20 pagesPromote AboDavid WilsonNo ratings yet

- Chapter Objectives: Health Care and Indigenous AustraliansDocument1 pageChapter Objectives: Health Care and Indigenous AustraliansAhmedFarooqNo ratings yet

- Goris PDFDocument24 pagesGoris PDFAndrew WongNo ratings yet

- Cultural Safety No Turning BackDocument2 pagesCultural Safety No Turning BackCale HollowayNo ratings yet

- RetrieveDocument10 pagesRetrieveAlexa Ramírez ContrerasNo ratings yet

- Term 2 Reflection 4Document3 pagesTerm 2 Reflection 4api-477982644No ratings yet

- ReviewDocument11 pagesReviewyhenti widjayantiNo ratings yet

- Aboriginal Health and Aboriginal Health Statistics: COSPAR Information Bulletin May 1982Document42 pagesAboriginal Health and Aboriginal Health Statistics: COSPAR Information Bulletin May 1982fahad zakirNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S2211335521003673 MainDocument13 pages1 s2.0 S2211335521003673 MainMarichelle LeclairNo ratings yet

- Evidence Based PracticeDocument11 pagesEvidence Based PracticesulhaaskaNo ratings yet

- Mental Health Research and EvaDocument26 pagesMental Health Research and EvaRima MuhsenNo ratings yet

- Culture and Healthy Lifestyles: A Qualitative Exploration of The Role of Food and Physical Activity in Three Urban Australian Indigenous CommunitiesDocument6 pagesCulture and Healthy Lifestyles: A Qualitative Exploration of The Role of Food and Physical Activity in Three Urban Australian Indigenous CommunitiesnettyNo ratings yet

- East Kimberley concepts of health and illnessDocument13 pagesEast Kimberley concepts of health and illnessgeralddsackNo ratings yet

- Decolonising AustraliaDocument22 pagesDecolonising AustraliaJamal Mughal100% (2)

- Copy 2Document7 pagesCopy 2Abdullah SakhiNo ratings yet

- Understanding Culture's Importance in Nursing CareDocument9 pagesUnderstanding Culture's Importance in Nursing CareRahul SharmaNo ratings yet

- 2008 Munro2008Document17 pages2008 Munro2008Lucila S. RolfoNo ratings yet

- IKC101 Assessment 3Document9 pagesIKC101 Assessment 3ovov711No ratings yet

- CALD in AustraliaDocument7 pagesCALD in AustraliaJosphat MwangiNo ratings yet

- Intersecting Cultures in Deaf Mental Health: An Ethnographic Study of NHS Professionals Diagnosing Autism in D/deaf ChildrenDocument22 pagesIntersecting Cultures in Deaf Mental Health: An Ethnographic Study of NHS Professionals Diagnosing Autism in D/deaf ChildrenCarol Albuquerque0% (1)

- Article Review Name - ID - Course Name - Date of SubmissionDocument6 pagesArticle Review Name - ID - Course Name - Date of SubmissionPrachi SharmaNo ratings yet

- Article Print 4155Document12 pagesArticle Print 4155bejanNo ratings yet

- Barriers_Accessing_Mental_HealDocument6 pagesBarriers_Accessing_Mental_HealRima MuhsenNo ratings yet

- WT Part 1 Chapt 4 FinalDocument14 pagesWT Part 1 Chapt 4 FinalNatasha AlbaShakiraNo ratings yet

- SEWB Fact SheetDocument4 pagesSEWB Fact Sheetalbatross558No ratings yet

- Deeble Institue Issues Brief No 19 1Document15 pagesDeeble Institue Issues Brief No 19 1dyan ayu puspariniNo ratings yet

- African Traditional Medicine's Contributions to Nigeria's HealthcareDocument12 pagesAfrican Traditional Medicine's Contributions to Nigeria's HealthcareAliNo ratings yet

- Cultural Competency in Health PDFDocument6 pagesCultural Competency in Health PDFMikaela HomukNo ratings yet

- Cultural Competence in Correctional Mental HealthDocument8 pagesCultural Competence in Correctional Mental HealthArielNo ratings yet

- 2 GreenblattDocument10 pages2 Greenblattisabel galloNo ratings yet

- Research participation by people with intellectual disability and mental health issues: An examination of the processes of consentDocument12 pagesResearch participation by people with intellectual disability and mental health issues: An examination of the processes of consentyalenaj09No ratings yet

- Negotiated Assignment ProposalDocument2 pagesNegotiated Assignment ProposalJerome PrattNo ratings yet

- Providing Culturally Appropriate Care: A Literature ReviewDocument9 pagesProviding Culturally Appropriate Care: A Literature ReviewLynette Pearce100% (1)

- Ethical Guideline ATSIDocument8 pagesEthical Guideline ATSINectanabisNo ratings yet

- 1 PB PDFDocument19 pages1 PB PDFKharen Domacena DomilNo ratings yet

- Bellamyetal 2015 Accesstomedication RefugeesDocument7 pagesBellamyetal 2015 Accesstomedication Refugeesdilmav111No ratings yet

- Mental Health Issues Among Refugee Children and Adolescents: Joh Henley and Julie RobinsonDocument12 pagesMental Health Issues Among Refugee Children and Adolescents: Joh Henley and Julie RobinsonMohamed Ridzwan AJNo ratings yet

- Traditional Healing: A Review of LiteratureDocument32 pagesTraditional Healing: A Review of LiteratureMax MarcusNo ratings yet

- Reflection pcp2-1 KsDocument4 pagesReflection pcp2-1 Ksapi-468597987No ratings yet

- Concepts DoajDocument21 pagesConcepts DoajNur AiniNo ratings yet

- 2017 UofT-IndigenousMedEd-HandbookDocument14 pages2017 UofT-IndigenousMedEd-HandbookRésaNo ratings yet

- Ijerph 19 11282 With CoverDocument13 pagesIjerph 19 11282 With Coverandriaeypreel1224No ratings yet

- Religion & SpiritualityDocument31 pagesReligion & SpiritualityMega Lita StevaniNo ratings yet

- Journal 2Document13 pagesJournal 2NurfaizuraNo ratings yet

- Indigenous Health Information and Knowledge SystemsDocument20 pagesIndigenous Health Information and Knowledge SystemsDexter Abrenica AlfonsoNo ratings yet

- MHC Lived Experience PW Framework Oct2022 DigitalDocument44 pagesMHC Lived Experience PW Framework Oct2022 DigitalChrisNo ratings yet

- Exploring The Relationship Between Housing and Health For Refugees and Asylum Seekers in South Australia 2017Document20 pagesExploring The Relationship Between Housing and Health For Refugees and Asylum Seekers in South Australia 2017GuiheneufNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S2157171615311242 MainDocument4 pages1 s2.0 S2157171615311242 MainGustavo Geronimo HernandezNo ratings yet

- Impact of colonisation on Aboriginal healthDocument6 pagesImpact of colonisation on Aboriginal healthマイ ケ ルNo ratings yet

- Health Information Services and Public Healthcare Awareness A Behavioral Study of Rural Inhabitants of The Balasore District of OdishaDocument7 pagesHealth Information Services and Public Healthcare Awareness A Behavioral Study of Rural Inhabitants of The Balasore District of OdishaInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- End-Of-life Issues For Aboriginal Patients A Literature ReviewDocument7 pagesEnd-Of-life Issues For Aboriginal Patients A Literature ReviewafmabreouxqmrcNo ratings yet

- Dwnload Full Physical Examination and Health Assessment 6th Edition Jarvis Solutions Manual PDFDocument36 pagesDwnload Full Physical Examination and Health Assessment 6th Edition Jarvis Solutions Manual PDFsithprisus100% (7)

- Assessment 2 - Written.Document5 pagesAssessment 2 - Written.jonkers85No ratings yet

- Human Resources Manager in San Jose CA Resume Priscilla CramerDocument2 pagesHuman Resources Manager in San Jose CA Resume Priscilla CramerPriscillaCramerNo ratings yet

- Colorectal Cancer: Symptoms, Staging and ScreeningDocument65 pagesColorectal Cancer: Symptoms, Staging and ScreeningMuhammed Muzzammil Sangani50% (2)

- SIP Physical SCiDocument8 pagesSIP Physical SCiShane Catherine BesaresNo ratings yet

- IELTS Essay SamplesDocument5 pagesIELTS Essay SamplesRebaz Jamal AhmedNo ratings yet

- Round Hill Community Garden FAQ - Round Hill, VirginiaDocument3 pagesRound Hill Community Garden FAQ - Round Hill, VirginiaZafiriou MavrogianniNo ratings yet

- Neonatal Care Pocket Guide For Hospital Physicians PDFDocument319 pagesNeonatal Care Pocket Guide For Hospital Physicians PDFelmaadawy2002100% (7)

- Obamacare Ushers in New Era For The Healthcare IndustryDocument20 pagesObamacare Ushers in New Era For The Healthcare Industryvedran1980No ratings yet

- Hse Risk Assessment - 006 Ra - Hdpe Duct LayingDocument7 pagesHse Risk Assessment - 006 Ra - Hdpe Duct Layingbinunalukandam83% (12)

- The Works of Alan OpenshawDocument38 pagesThe Works of Alan OpenshawAlan OpenshawNo ratings yet

- Water Treatment PDFDocument87 pagesWater Treatment PDFJubin KumarNo ratings yet

- T2anklearthrodesis Optech b1000044d0710Document36 pagesT2anklearthrodesis Optech b1000044d0710Alsed GjoniNo ratings yet

- Penile Injection TherapyDocument4 pagesPenile Injection Therapydr NayanBharadwajNo ratings yet

- Organon of Medicine All Years 2marks Question Viva Questions AnswersDocument12 pagesOrganon of Medicine All Years 2marks Question Viva Questions Answersabcxyz15021999No ratings yet

- Clinical Immunology and AllergyDocument156 pagesClinical Immunology and AllergySoleil DaddouNo ratings yet

- TWC Final Settlement DocsDocument374 pagesTWC Final Settlement DocsTHROnlineNo ratings yet

- Booklet - e 1 - 2013Document101 pagesBooklet - e 1 - 2013Dani AedoNo ratings yet

- Media Kesehatan Masyarakat: Gracewati Rambu Ladu Day, Muntasir Basri, Rina Waty SiraitDocument15 pagesMedia Kesehatan Masyarakat: Gracewati Rambu Ladu Day, Muntasir Basri, Rina Waty Siraitnimas ayu kusumaningrumNo ratings yet

- NCP LymphomaDocument3 pagesNCP Lymphomamahmoud fuqahaNo ratings yet

- Pothole Claim Form in PhiladelphiaDocument3 pagesPothole Claim Form in Philadelphiaphilly victorNo ratings yet

- Psychopathic Personality: Bridging The Gap Between Scientific Evidence and Public PolicyDocument69 pagesPsychopathic Personality: Bridging The Gap Between Scientific Evidence and Public PolicyGokushimakNo ratings yet

- DMLC Part I & II Cyprus (Hyundai Busan)Document17 pagesDMLC Part I & II Cyprus (Hyundai Busan)Shankar Singh0% (1)

- Thomas Foot ReflexologyDocument112 pagesThomas Foot ReflexologySa MiNo ratings yet

- 1.2 POWERPOINT History of ForensicsDocument23 pages1.2 POWERPOINT History of ForensicsSilay Parole & ProbationNo ratings yet

- Detecting Malingering On The MMPI-2 - An Examination of The Utilit PDFDocument56 pagesDetecting Malingering On The MMPI-2 - An Examination of The Utilit PDFernie moreNo ratings yet

- Top 10 Graphic Design Interview Questions and AnswersDocument16 pagesTop 10 Graphic Design Interview Questions and Answersbetsjonh100% (1)

- Ecg 01Document103 pagesEcg 01Bandar al ghamdi100% (1)

- 3075 SWMS RendererDocument13 pages3075 SWMS Renderernik KooNo ratings yet

- Introduction of Online Basic First Aid Course - For Circulation April 2021Document39 pagesIntroduction of Online Basic First Aid Course - For Circulation April 2021Yuwaraj NaiduNo ratings yet

- Leopold Maneuvers Nursing ProcedureDocument3 pagesLeopold Maneuvers Nursing ProcedureDiane grace SorianoNo ratings yet

- Measurement and Correlates of Family Caregiver Self-Efficacy For Managing DementiaDocument9 pagesMeasurement and Correlates of Family Caregiver Self-Efficacy For Managing DementiariskhawatiNo ratings yet