Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Forensic Anthropology Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History

Uploaded by

Rysdana Nur KhalidOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Forensic Anthropology Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History

Uploaded by

Rysdana Nur KhalidCopyright:

Available Formats

MENU

Forensic

Anthropology

Home / Education / Teaching Resources /

Anthropology and Social Studies Resources /

Forensic Anthropology

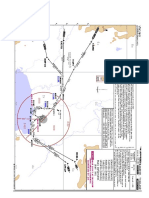

This skeleton of a 17th-century teenage boy

was found in 2001 at the Leavy Neck site in

Anne Arundel County, Maryland.

Smithsonian photo 18AN828.

What Do

Forensic

Anthropologist

s and

Detectives

Have in

Common?

Forensic anthropology is a special

sub-field of physical anthropology

(the study of human remains) that

involves applying skeletal analysis

and techniques in archaeology to

solving criminal cases. When

human remains or a suspected

burial are found, forensic

anthropologists are called upon to

gather information from the bones

and their recovery context to

determine who died, how they

died, and how long ago they died.

Forensic anthropologists

specialize in analyzing hard tissues

such as bones. With their training

in archaeology, they are also

knowledgeable about excavating

buried remains and meticulously

recording the evidence.

Reading a

Skeleton

A forensic anthropologist can read

the evidence in a skeleton like you

read a book. The techniques they

use to answer questions in

criminal cases can be applied to

skeletons of any age, modern or

ancient. The stages of growth and

development in bones and teeth

provide information about

whether the remains represent a

child or adult. The shape of pelvic

bones provides the best evidence

for the sex of the person.

Abnormal changes in the shape,

size and density of bones can

indicate disease or trauma. Bones

marked by perimortem injuries,

such as unhealed fractures, bullet

holes, or cuts, can reveal cause of

death. The trained anthropologist

is also able to identify skeletal

clues of ancestry. Even certain

activities, diet, and ways of life are

reflected in bones and teeth.

Analyzing

Human

Remains

Anthropologists at the

Smithsonian’s National Museum of

Natural History have been called

upon to analyze human remains

for over a century. The remains

may represent victims of violence

or natural disasters. In these cases

Smithsonian anthropologists work

with the FBI, State Department,

and other law enforcement

agencies to identify the individuals

and solve crimes. They also

conduct research on historic and

prehistoric human remains to learn

more about people from the past.

As Smithsonian forensic

anthropologist Kari Bruwelheide

says, "The bones are like a time

capsule."

Smithsonian anthropologist Dr.

Douglas Owsley, examining a

skeleton from historic Jamestown,

discovered evidence of chops to

the skull from an axe or other

sharp bladed, implement. Knife

cuts were also observed on the

bone. Along with other

information such as biological

indicators and discovery location

of the remains, Dr. Owsley

concluded that a 14-year-old girl

had been cannibalized after she

died. His discovery supported

other historic data that the

colonists of Jamestown suffered

severe starvation during the harsh

winter of 1609-1610.

Techniques:

Leaving No

Bone Unturned

Anthropologists at the National

Museum of Natural History use a

variety of techniques to analyze

human remains and record their

observations. For example, the

bones are typically photographed

and X-rayed. Some remains may

undergo CT scanning or be

examined with high-powered

microscopes. These techniques

provide detailed information

about remains without altering

them while providing a visual

record. DNA analysis may be used

to help establish identity. This

type of testing is most often used

in modern forensic case work, but

mitochondrial DNA in bones and

teeth can be used to confirm

relationships of old remains with

deceased or living descendants.

Other chemical analyses, such as

those involving isotopes, can

provide information about the age

of bones and a person’s diet.

The data gathered is studied and

combined to draw conclusions

about the deceased individual.

For a modern case, photos of the

skull may be superimposed on

photos of missing people to look

for consistencies between the

bone and fleshed form. Even in

cases where no photos exist, the

face can be reconstructed based

on the underlying bone structure

and known standards of facial

tissue thicknesses. For example,

using facial reconstruction,

Smithsonian forensic

anthropologist Dr. David Hunt was

able to bring about correct

identification of the remains of a

child found near Las Vegas.

Owsley and Bruwelheide were

able to help rebuild the likeness of

the girl from Jamestown.

Collections of

Bones

Comparing found remains to

other human skeletons is essential

for many analyses. The National

Museum of Natural History has

one of the world's largest

Biological Anthropology

collections, with over 30,000 sets

of human remains representing

populations from around the

world. Many of the skeletons have

associated age, sex, ancestry, and

cause of death data. Individual

remains with known biological

information are especially valuable

references. Forensic

anthropologists have used these

skeletons to develop standards for

determining sex, age and ancestry

in unknown remains. The bones

and teeth are also used as

comparative materials in cases

where interpretation of certain

features is difficult. They are

also used to train students who

are the next generation of

biological anthropologists.

Skeletal reference series may also

be used to document trends in

health and population structures

over time. Smithsonian Curator Dr.

Douglas Ubelaker, looking at a

range of skulls from 16th-20th

century Spain and Portugal, found

that women's faces got larger over

time.

Reconstructing

the Past

The study of historic human

remains by biological

anthropologists at the

Smithsonian has led to discoveries

that are changing our view of the

past and how we investigate it.

The work of Dr. Owsley and Kari

Bruwelheide has helped create a

better picture of how people lived

and died in colonial America. For

example, even a wealthy woman,

the wife of the governor of

Maryland's first English colony,

St. Mary's City, suffered from

limited medical care for a

fractured thigh bone. The sorts of

treatments that would be used

today (traction and screws), were

not options at the time. Available

treatments, such as medicine

containing arsenic, may have

made conditions worse. Chemical

testing of this woman's preserved

hair show ingestion of this toxin

with increasing dosage closer to

death.

Whether used to better

understand modern or historic

remains, the tools and techniques

of forensic anthropology give the

living a window into the lives of

the dead.

Related

Resources

Written in Bone

Video: Forensic

Anthropology - Bone

Whispering

Subject Guide - Bones

and Forensic

Anthropology

Featured Collection:

Pathologies on Human

Femora

Subject Guide: Bones and

Environmental Health

Resource Type

Science Literacy Articles

Grade Level

6-8

Topics

Anthropology and Social Studies

Smithsonian

Type your email to get NMNH updates.

National Museum

of Natural History

SIGN UP

Email powered by BlackBaud (Privacy Policy,

Terms of Use)

Face Twitt

DONATE Insta

book er gram

1000 Madison Drive NW

Washington, D.C. 20560

Free admission. Open every day except

Dec. 25 from 10 AM to 5:30 PM

Home

Smithsonian Institution

Terms of Use Privacy Policy

Host an Event Jobs Press

Blog Contact Us

You might also like

- Beyond the Body Farm: A Legendary Bone Detective Explores Murders, Mysteries, and the Revolution in Forensic ScienceFrom EverandBeyond the Body Farm: A Legendary Bone Detective Explores Murders, Mysteries, and the Revolution in Forensic ScienceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (107)

- Forensic AntropologyDocument8 pagesForensic AntropologyIustina MariaNo ratings yet

- Dry Bones: Exposing The History And Anatomy of Bones From Ancient TimesFrom EverandDry Bones: Exposing The History And Anatomy of Bones From Ancient TimesNo ratings yet

- Ubelaker, 2018 - A History of Forensic AnthropologyDocument9 pagesUbelaker, 2018 - A History of Forensic AnthropologyDanielaCabralNo ratings yet

- Forensic Science Notes by MeDocument20 pagesForensic Science Notes by MeMahadeva 371995No ratings yet

- Bone Histology of Fossil Tetrapods: Advancing Methods, Analysis, and InterpretationFrom EverandBone Histology of Fossil Tetrapods: Advancing Methods, Analysis, and InterpretationRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Forensic Anthropology HandoutDocument11 pagesForensic Anthropology HandoutSuzan100% (1)

- Forensic Methods for Identifying Unknown CorpsesDocument4 pagesForensic Methods for Identifying Unknown CorpsesIsabel Victoria GarciaNo ratings yet

- Bautista-Sean-G.-FS-301-WEEK 14 ACTIVITY - FORMEDDocument2 pagesBautista-Sean-G.-FS-301-WEEK 14 ACTIVITY - FORMEDSean BautistaNo ratings yet

- How to Identify a Forgery: A Guide to Spotting Fake Art, Counterfeit Currencies, and MoreFrom EverandHow to Identify a Forgery: A Guide to Spotting Fake Art, Counterfeit Currencies, and MoreRating: 2 out of 5 stars2/5 (1)

- Is Eve RealDocument1 pageIs Eve RealMikki EugenioNo ratings yet

- Ubelaker. 958Document88 pagesUbelaker. 958Marie HorvillerNo ratings yet

- Eradicating deafness?: Genetics, pathology, and diversity in twentieth-century AmericaFrom EverandEradicating deafness?: Genetics, pathology, and diversity in twentieth-century AmericaNo ratings yet

- PDFDocument385 pagesPDFRajamaniti100% (2)

- Sex Itself: The Search for Male & Female in the Human GenomeFrom EverandSex Itself: The Search for Male & Female in the Human GenomeNo ratings yet

- Armelagos Et Al. A Century of Skeletal PathologyDocument13 pagesArmelagos Et Al. A Century of Skeletal PathologylaurajuanarroyoNo ratings yet

- Untangling Twinning: What Science Tells Us about the Nature of Human EmbryosFrom EverandUntangling Twinning: What Science Tells Us about the Nature of Human EmbryosNo ratings yet

- These "Thin Partitions": Bridging the Growing Divide between Cultural Anthropology and ArchaeologyFrom EverandThese "Thin Partitions": Bridging the Growing Divide between Cultural Anthropology and ArchaeologyNo ratings yet

- Science in AnthDocument5 pagesScience in AnthJm VictorianoNo ratings yet

- History Within: The Science, Culture, and Politics of Bones, Organisms, and MoleculesFrom EverandHistory Within: The Science, Culture, and Politics of Bones, Organisms, and MoleculesRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (1)

- How Many Early Human Species Existed On EarthDocument3 pagesHow Many Early Human Species Existed On EarthSuzanne BuckleyNo ratings yet

- Future Humans: Inside the Science of Our Continuing EvolutionFrom EverandFuture Humans: Inside the Science of Our Continuing EvolutionRating: 2.5 out of 5 stars2.5/5 (4)

- The Stem Cell DebatesDocument52 pagesThe Stem Cell DebatesPeggy W SatterfieldNo ratings yet

- Mapping Human History by Steve Olson - Discussion QuestionsDocument5 pagesMapping Human History by Steve Olson - Discussion QuestionsHoughton Mifflin HarcourtNo ratings yet

- Week 11Document2 pagesWeek 11YoMomma PinkyNo ratings yet

- 2002 Forensics, Archaeology, and Taphonomy The Symbiotic RelationshipDocument27 pages2002 Forensics, Archaeology, and Taphonomy The Symbiotic RelationshipjonathanNo ratings yet

- ANTH1120 Research PaperDocument8 pagesANTH1120 Research Paperkhloeethompson004No ratings yet

- Introducing Philosophy of Science: A Graphic GuideFrom EverandIntroducing Philosophy of Science: A Graphic GuideRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (22)

- Collected Papers of Michael E. Soulé: Early Years in Modern Conservation BiologyFrom EverandCollected Papers of Michael E. Soulé: Early Years in Modern Conservation BiologyNo ratings yet

- Taylor & Francis, Ltd. The Journal of Sex ResearchDocument6 pagesTaylor & Francis, Ltd. The Journal of Sex ResearchMNo ratings yet

- Concept of Race - Research PaperDocument5 pagesConcept of Race - Research Paperapi-356763214No ratings yet

- Personal Adornment and the Construction of Identity: A Global Archaeological PerspectiveFrom EverandPersonal Adornment and the Construction of Identity: A Global Archaeological PerspectiveHannah V. MattsonNo ratings yet

- A Traffic of Dead Bodies: Anatomy and Embodied Social Identity in Nineteenth-Century AmericaFrom EverandA Traffic of Dead Bodies: Anatomy and Embodied Social Identity in Nineteenth-Century AmericaRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (5)

- Introduction to Personal Identification Techniques: Fingerprints, Forensics, and AnthropometryDocument7 pagesIntroduction to Personal Identification Techniques: Fingerprints, Forensics, and AnthropometryPatricia Juralbar QuintonNo ratings yet

- Forensic AnthropologyDocument1 pageForensic AnthropologylllleonnnNo ratings yet

- Unit 2 Relationship With Other Disciplines: Definition and ScopeDocument8 pagesUnit 2 Relationship With Other Disciplines: Definition and ScopeLokesh RathoreNo ratings yet

- The Stem Cell Dilemma: The Scientific Breakthroughs, Ethical Concerns, Political Tensions, and Hope Surrounding Stem Cell ResearchFrom EverandThe Stem Cell Dilemma: The Scientific Breakthroughs, Ethical Concerns, Political Tensions, and Hope Surrounding Stem Cell ResearchNo ratings yet

- Limits of Biological DeterminisDocument8 pagesLimits of Biological DeterminisMariana ÁlvarezNo ratings yet

- The Longevity Seekers: Science, Business, and the Fountain of YouthFrom EverandThe Longevity Seekers: Science, Business, and the Fountain of YouthNo ratings yet

- On The Origin of ReligionDocument4 pagesOn The Origin of ReligionAlejandro Murillo V.No ratings yet

- Forensic Anthropology Identification TechniquesDocument236 pagesForensic Anthropology Identification TechniquesRENE MARANONo ratings yet

- What Are Stem Cells?: Definitions at the Intersection of Science and PoliticsFrom EverandWhat Are Stem Cells?: Definitions at the Intersection of Science and PoliticsNo ratings yet

- Ova Donation and Symbols of Sub - Konrad, MonicaDocument26 pagesOva Donation and Symbols of Sub - Konrad, MonicaataripNo ratings yet

- William Stimpson and the Golden Age of American Natural HistoryFrom EverandWilliam Stimpson and the Golden Age of American Natural HistoryNo ratings yet

- Introduction to the Four Main Fields of AnthropologyDocument44 pagesIntroduction to the Four Main Fields of AnthropologyAlexandru RadNo ratings yet

- Forensic Anthropology PDFDocument63 pagesForensic Anthropology PDFjourey08No ratings yet

- Report ForensicsDocument3 pagesReport ForensicsAnnKhoLugasanNo ratings yet

- Science, Evolution, and CreationismDocument2 pagesScience, Evolution, and CreationismmaurolassoNo ratings yet

- Development Length ACI 318-14 v2.0Document5 pagesDevelopment Length ACI 318-14 v2.0Raymund Dale P. BallenasNo ratings yet

- Shell Marine Pocketbook For International MarineDocument60 pagesShell Marine Pocketbook For International MarineGage Cendk HNo ratings yet

- AP Calculus AB 4.1A Worksheet Key ConceptsDocument44 pagesAP Calculus AB 4.1A Worksheet Key ConceptsDavid Joseph100% (1)

- In Re Winslow 1966 - Scope & Content of Prior ArtDocument5 pagesIn Re Winslow 1966 - Scope & Content of Prior ArtJorel Andrew FlautaNo ratings yet

- BhaishajyaDocument28 pagesBhaishajyadrsa2No ratings yet

- Unit 1 Unit 2 Unit 3 DIFFERENTIAL CALCULUS 1 2 3 PDFDocument124 pagesUnit 1 Unit 2 Unit 3 DIFFERENTIAL CALCULUS 1 2 3 PDFjayaram prakash kNo ratings yet

- Well Components: Petroleum Production Engineering. DOI: © 2007 Elsevier Inc. All Rights ReservedDocument15 pagesWell Components: Petroleum Production Engineering. DOI: © 2007 Elsevier Inc. All Rights Reservedsoran najebNo ratings yet

- Power Systems Analysis Short Ciruit Load Flow and HarmonicsDocument1 pagePower Systems Analysis Short Ciruit Load Flow and HarmonicsJurij BlaslovNo ratings yet

- SEO-Optimized Title for Quantitative Techniques for Business-II Exam DocumentDocument4 pagesSEO-Optimized Title for Quantitative Techniques for Business-II Exam DocumentEthan WillsNo ratings yet

- Home Automation Chapter 1Document7 pagesHome Automation Chapter 1Nishant Sawant100% (1)

- Pol Science ProjectDocument18 pagesPol Science ProjectAnshu SharmaNo ratings yet

- Chapter 17Document48 pagesChapter 17MahmoudKhedrNo ratings yet

- African Healthcare Setting VHF PDFDocument209 pagesAfrican Healthcare Setting VHF PDFWill TellNo ratings yet

- VTBS 20-3DDocument1 pageVTBS 20-3Dwong keen faivNo ratings yet

- Facts on Timber Engineering and StructuresDocument73 pagesFacts on Timber Engineering and StructuresNaresworo NugrohoNo ratings yet

- MiG 21Document29 pagesMiG 21Zoran Vulovic100% (2)

- Advances in The Study of The Genetic Disorders PDFDocument484 pagesAdvances in The Study of The Genetic Disorders PDFhayamasNo ratings yet

- IndictmentDocument2 pagesIndictmentCBS Austin WebteamNo ratings yet

- Group 1 STEM 12 2P SIP FINALDocument17 pagesGroup 1 STEM 12 2P SIP FINALFhing FhingNo ratings yet

- 241-Article Text-1014-1-10-20201017Document8 pages241-Article Text-1014-1-10-20201017derismurib4No ratings yet

- I PU Assignment 2023-24 For WorkshopDocument12 pagesI PU Assignment 2023-24 For Workshopfaruff111100% (1)

- Build a Homebrew Pre-Amplified MicrophoneDocument3 pagesBuild a Homebrew Pre-Amplified MicrophoneMacario Imbudo BukatotNo ratings yet

- 12.3 Operation Qualification Protocol For Laminar Air Flow UnitDocument4 pages12.3 Operation Qualification Protocol For Laminar Air Flow UnituzairNo ratings yet

- Kant ParadigmDocument265 pagesKant ParadigmkairospandemosNo ratings yet

- Man and Mystery Vol 13 - Monsters and Cryptids (Rev06)Document139 pagesMan and Mystery Vol 13 - Monsters and Cryptids (Rev06)Pablo Jr AgsaludNo ratings yet

- 1964 Plymouth Barracuda Landau (Factory Prototype W/ Targa Top) - Photos & CorrespondenceDocument12 pages1964 Plymouth Barracuda Landau (Factory Prototype W/ Targa Top) - Photos & CorrespondenceJoseph GarzaNo ratings yet

- Study Journal Lesson 23-32 - LisondraDocument3 pagesStudy Journal Lesson 23-32 - Lisondrasenior highNo ratings yet

- Watkins Göbekli Tepe Jerf El Ahmar PDFDocument10 pagesWatkins Göbekli Tepe Jerf El Ahmar PDFHans Martz de la VegaNo ratings yet

- D.K.Pandey: Lecture 1: Growth and Decay of Current in RL CircuitDocument5 pagesD.K.Pandey: Lecture 1: Growth and Decay of Current in RL CircuitBBA UniversityNo ratings yet

- Ceramic Inlays A Case Presentation and LessonsDocument11 pagesCeramic Inlays A Case Presentation and LessonsStef David100% (1)