Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Barnard GarcilasosPoeticsSubversion 1987

Uploaded by

Cry VandalOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Barnard GarcilasosPoeticsSubversion 1987

Uploaded by

Cry VandalCopyright:

Available Formats

Garcilaso's Poetics of Subversion and the Orpheus Tapestry

Author(s): Mary E. Barnard

Source: PMLA , May, 1987, Vol. 102, No. 3 (May, 1987), pp. 316-325

Published by: Modern Language Association

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/462479

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

Modern Language Association is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend

access to PMLA

This content downloaded from

200.16.86.81 on Fri, 06 Oct 2023 20:59:25 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

MARY E. BARNARD

Garcilaso's Poetics of Subversion and the Orpheus Tapestry

O RPHEUS LOST Eurydice to the under- this type of transformative act is often compared to

world. Given the chance to restore his wife bees gathering pollen from flowers and converting

to the world of light and life, Orpheus dis- it to honey-an image derived originally from the

obeyed the injunction not to look back and lost her ancients and a popular topic in discussions on im-

forever. Then, as he had earlier left spirits spell- itation. In the alchemy of imitation, the industri-

bound in Hades, the poet and lover enchanted ousness of the bees signals the creative energy of the

beasts, trees, and stones with his piercing lament in poets, who convert what they inherit from their

the living world. This poignant tale of the mysteri- precursors into elegant variations. Transformation

ous lyrist was appropriated by poets of the Span- was often accompanied by emulation (aemulatio),

ish Golden Age, including Garcilaso de la Vega an attempt to surpass the model; and so the inter-

(1501[?]-36), whose imitation in his third eclogue textual dialogue between surface text and subtext

engages his models in an intertextual dialogue. clearly emerges as a conflict. (On transformation

The Renaissance imitation of models is clearly a and emulation in Renaissance theories and practice

form of intertextuality, the act of writing by which of imitation, see Pigman and Greene.) Petrarch, the

a text emerges as a product of prior texts.I Terence master imitator of ancient material, warns: "Take

Cave speaks of this interplay of texts within the care that what you have gathered does not long re-

framework of sixteenth-century theories of imitation:main in you in its original state: the bees would have

no glory if they did not convert what they found

Imitation theory . . . recognizes the extent to which the into something different and something better" (1:

production of any discourse is conditioned by pre-existing 44; trans. based on Pigman 7). To the extent that

instances of discourse; the writer is always a rewriter, the emulation strives for a victory, it is revisionary and

problem then being to differentiate and authenticate the corrective, an implicit criticism of the subtext. In the

rewriting. This is executed not by the addition of some-

language of contemporary literary theory-that of

thing wholly new, but by the dismembering and recon-

Harold Bloom in his Map of Misreading-the revi-

struction of what has already been written. (76)

sionist poet "strives to see again, so as to esteem and

estimate differently, so as then to aim 'correc-

Garcilaso's imitation of classical and Italian models

tively' " (4). Through a series of tropes and "psy-

in his treatment of the Orpheus myth in the third

chic defenses," Bloom's revisionist poets "correct"

eclogue is an example of this art of rewriting. In

their precursors in order to win a victory: not only

what I call his "poetics of subversion," Garcilaso

to assert their freedom from the inevitable tyranny

"dismembers" his sources, adapts and transforms

of earlier poets but to overcome them. In a "trium-

fragments of his antecedents, reconstructs them,

phant wrestling with the greatest of the dead" (9),

and in the process fabricates his text. Garcilaso's

Bloom's poets insist on their own uniqueness and

transformation of his multiple sources also betrays

accuracy, seeking in effect to seem self-begotten.

elements of emulation, a correction of the models

Renaissance revisionist poets may have had simi-

in an attempt to achieve a decisive victory over

lar anxieties. It is true that, peacocklike, they imi-

them. Before I examine instances of intertextuality

tate the ancients to display their classical erudition,

in Garcilaso's text, however, a few words about the

but there is ample evidence from those who speak

role of transformation and emulation in Renais-

on matters of imitation that the pressures exerted

sance imitation theory are necessary.

by a prestigious past caused much concern. The

Renaissance theories of imitation called for the

words from Petrarch I quote above are an example.

appropriation of an alien text through a transfor-

Erasmus speaks more vehemently in his

mation in which the text reemerges as part of a new

Ciceronianus:

idiom. For instance, through a kind of artificial

mythopoeia, Garcilaso presents new variants for the Some shrewd people distinguish imitation from emula-

Orpheus myth: a transformed Orpheus stands with- tion. Imitation aims at similarity; emulation, at victory.

out a lyre on a bleak mountain, enchanting neither Thus, if you take all of Cicero and him alone for your

inanimate nature nor beasts. In theoretical treatises, model, you should not only reproduce him, but also de-

316

This content downloaded from

200.16.86.81 on Fri, 06 Oct 2023 20:59:25 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Mary E. Barnard 317

feat him. He must not be just passed by, but rather left En tanto, no te offenda ni te harte

behind. (116; trans. Pigman 24) tratar del campo y soledad que amaste,

ni desdenies aquesta inculta parte

de mi estilo, que'n algo ya estimaste;

It is safe to assume that, unlike Bloom's poets,

Renaissance poets, in correcting their sources, do

not seek to seem self-begotten; their reverence for

Aplica, pues, un rato los sentidos

antiquity is too transparent. But they insist on their

al baxo son de mi ~ampofna ruda,

individual uniqueness and accuracy and, following

indigna de liegar a tus oydos,

admonitions such as those of Petrarch and

pues d'ornamento y gracia va desnuda;

Erasmus, even arrogantly attempt to surpass their

mas a las vezes son mejor oydos

precursors. True creative imitation is, above all, an el puro ingenio y lengua casi muda,

act of subversion. testigos limpios d'animo inocente,

The emergence of the new text from a struggle que la curiosidad del eloquente.

with its prestigious sources, however, involves hom- (29-36, 41-48)

age as well as correction. In their famous exchange

of letters on imitation, Pico della Mirandola and Apollo and all nine sisters will give me leisure and a

Pietro Bembo agree that emulation should be the tongue with which to speak the least of the praises of

which you are worthy, for this will be the most that I can

goal of the imitator. They view rivalry as a stimu-

do. Meanwhile, I hope that you're not offended or bored

lus for creative imitation, a notion later elaborated

by my writing of the countryside and solitude you loved,

in Erasmus's eloquent Ciceronianus (1528). But

and that you don't disdain this rustic aspect of my style,

Bembo's clear admiration for the model, coupled

which you once esteemed.. . . Apply then for a while

with the idea of rivalry, reveals the complexity of theyour senses to the humble sound of my crude pipes, un-

imitator's task. In the Renaissance, transformative worthy of reaching your ears, for it is naked of adornment

imitation, with its notions of emulation, has a dou- and grace; but at times it is better to listen to creativity

ble focus: an implicit faith in the original and a free- pure and simple and to an almost silent tongue, pure wit-

dom to create new poetic visions. If I may borrow nesses of the innocent soul, than to the sophistication of

Julia Kristeva's words, "le texte poetique est produit the rhetorician. (69_70)2

dans le mouvement complexe d'une affirmation et

d'une negation simultanees d'un autre texte" 'the

The speaker as poet draws a distinction between two

poetic text is produced in the complex movement of

kinds of poetry: poetry as divine inspiration and

a simultaneous affirmation and negation of an-

poetry as a product of pure ingenio. Since these are

other text' (Se'me'iotike 257; trans. mine). As we

conceived as oral discourse, speaking (30) and sing-

shall see, Garcilaso, whose third eclogue contains

ing (42), the term lengua plays a major role in the

elements of emulation, is one of the most skillful

passage. Apollo and the muses will endow the poet

intertextualists of the Golden Age. His multivocal

with ocio y lengua, the divine gifts that will carry

text wrestles with its sources, at times affirming

out the business at hand, the celebration of the

them, at times transforming them. At other times

woman to whom the poem is dedicated. But the sur-

the text privileges one voice over another; it then

prising "En tanto" 'Meanwhile' of line 33 shifts the

shifts the emphasis, not only "remaking" its sources

direction of the poem and introduces a new poetic

but also seeking to overcome them. In the process,

concern. The poem will address not celebration

there emerges a highly imaginative version of the

through inspiration but something that is suppos-

Orpheus myth, an artificial erotic drama of loss and

edly the result of a "lengua casi muda" 'an almost

brooding pain.

silent tongue,' that is, the lowly pastoral.3 Both the

At the beginning of the eclogue, the speaker as

blemishes of the text ("inculta parte / de mi estilo"

poet reveals thoughts about his writing, about in-

'rustic aspect of my style'; "baxo son de mi cam-

spiration and creativity (ingenio), imitation and ar-

ponia ruda, / indigna de llegar a tus oydos" 'hum-

tifice. He tells Maria:

ble sound of my crude pipes, unworthy of reaching

your ears') and its triumph (the product of "[un]

Apollo y las hermanas todas nueve animo inocente" '[an] innocent soul') are, if not si-

me daran ocio y lengua con que hable lence, something approaching the virtues of silence:

lo menos de lo que'n tu ser cupiere, a lack of artifice and rhetorical eloquence. More-

que'sto sera lo mas que yo pudiere. over, the lengua casi muda, coupled with puro inge-

This content downloaded from

200.16.86.81 on Fri, 06 Oct 2023 20:59:25 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

318 Garcilaso's Poetics of Subversion and the Orpheus Tapestry

nio (ingenio may be identified with the classical minating in the scene of the decapitated Elissa (the

ingenium, the creative talent of a writer), not only nympha degollada) and Nemoroso's lament.4 Each

makes a claim for the moral superiority of the poet of the mythological tales, beginning with Orpheus

("testigos limpios d'animo inocente" 'pure wit- and Eurydice, prefigures the pastoral story. Speak-

nesses of the innocent soul') but seems to announce ing of a text's plurality of meaning ("the signifiers

the self-begetting of the poem, an autonomous text that weave it"), Roland Barthes points out that

that is a product of pure invention rather than of "etymologically the text is a cloth; textus, from

rhetorical sophistication. The poet disavows all ties which text derives, means 'woven"' ("Work" 76).

with literary tradition: he sets himself up as the sole The weaving of the tapestries in the third eclogue

creator and master of his poetic, albeit lowly, mimes the writing of the text "woven" from frag-

universe. ments of prior texts.

But here we are dealing with an obligatory mod- Garcilaso finds the models for his Orpheus in an-

esty topos, the writer who places his creation, cient and Italian sources. The main ancient model,

knowingly and shamelessly, in a position of artis- according to his early commentators and modern

tic inferiority. Since the topos is simply that, a source critics, is Vergil's Georgics (4.453-527).

topos-and not meant to be believed-it implicitly There are, moreover, reminiscences from the

affirms what it explicitly denies: rhetoric will be theItalians: the Eurydice tapestry from Sannazaro's

guiding principle of the text. Artifice will rule. And Arcadia (prose 12), Ariosto's Orlando furioso, and

since the key literary theory enacted in the text is the Orphei tragoedia.5 Ovid's Metamorphoses 10

that of imitation of models, we have a text that is and 11 and Martial's epigram 25 from De spec-

far from autonomous. The poet is affirming, per- taculis may also have served as models.

haps even celebrating, his participation in an act of To create his Orpheus in the short space of three

rewriting. stanzas, Garcilaso must be selective. He chooses

Pastoral enacts a lost Golden Age of simplicity three key moments from the ancient tale: the death

and innocence in which there was one tongue and of Eurydice; the katadbasis, Orpheus's descent into

no need of rhetoric-and the modesty topos Hades to retrieve her; and Orpheus's lament after

reenacts this state. But in Garcilaso, as in Theocri- her final loss. In the first stanza (121-28), Garcilaso

tus, Vergil, and the Italians, the fiction of pastoral describes the Thracian landscape and introduces a

is elaborated in the fiction of words. Garcilaso's reference to Orpheus's lament: "donde el amor mo-

modesty topos reveals the duplicity of pastoral: its vi6 con tanta gracia / la dolorosa lengua del de Tra-

artlessness is a deception. Ultimately the pastoralist cia" 'where love moved with so much grace the

must indulge in the "curiosidad del eloquiente." grieving tongue of the Thracian' (127-28; 73). By

Garcilaso-poet, courtier, and soldier in the beginning, in effect, with the ending of his story,

army of Charles v-met with an early death in a Garcilaso establishes a circular structure that fore-

skirmish with the French in Provence, leaving be- closes all possibilities for a happy ending. What fol-

hind a small opus. Frustrated love is the predomi- lows simply confirms what the lament clearly

nant theme of his poems, which include three announces: the moment of loss and a doomed lover,

eclogues, thirty-eight Petrarchan sonnets, five can- a Renaissance Orpheus who cannot disguise his an-

ciones, one epistle, and two elegies. He also wrote cient origins. Garcilaso has read his sources.

several coplas and three odes in Latin. Garcilaso's Garcilaso's elaborate treatment of Eurydice's

reworkings of the Orpheus story are featured death in the second stanza is a self-conscious expan-

prominently in his verses. They appear in sonnets sion of his classical models, though, as we shall see,

15 and 24, cancion 5, ode 2, and the second and he owes more to Sannazaro, who offers a fuller ver-

third eclogues. The most significant version is sion of the death scene. Vergil's text tells how

elaborated in the first tapestry scene in the third ec-

Eurydice runs toward a huge snake hidden in the tall

logue, whose four tapestries depict frustrated love grass; her death is conveyed only by the commiser-

affairs: three mythological tales-Orpheus and Eu- ating phrase moritura puella 'doomed maiden'

rydice, Apollo and Daphne, Venus and Adonis- (458). Ovid's text is more explicit but equally curt:

and a pastoral tale, the adventure of Elissa and the strolling through the grass, the woman is bitten on

shepherd Nemoroso. Loss and grief are the haunt- the ankle by the serpent's tooth and dies (10.8-10).

ing notes of these tapestries, which present a The ancients' clipped renditions give way in Gar-

crescendo of violent destruction of a loved one, cul- cilaso to extensive sensual details:

This content downloaded from

200.16.86.81 on Fri, 06 Oct 2023 20:59:25 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Mary E. Barnard 319

Estava figurada la hermosa from the spiritual to the erotic. The sensual Gar-

Euridice, en el blanco pie mordida cilaso here outdoes the sensual Italian. Garcilaso

de la pequefia sierpe poncofiosa, may have also imitated the Orphei tragoedia, where

entre la yerva y flores escondida; Eurydice's soul is described as having left a beau-

descolorida estava como rosa

tiful abode, that is, her body: "Abbandonato ha il

que ha sido fuera de saz6n cogida,

spirto peregrino / Quel bel albergo" 'the wander-

y el anima, los ojos ya bolviendo,

ing spirit has abandoned that beautiful abode'

de la hermosa carne despidiendo. (129-36)

(2.144-45; trans. mine). But while the tragedy uses

Beautiful Eurydice was depicted, bitten on her white foot

the metaphor albergo for the body, Garcilaso

by the small venomous snake hidden in the grass and speaks of the sensuous carne, lending freshness and

flowers; she was pale like a rose that has been plucked out strength to his text.

of season and, rolling back her eyes, was already releas- Beauty and death are dramatically juxtaposed:

ing her soul from her beautiful flesh. (73) the pastoral landscape with its idyllic splendor

along with the delicate, beautiful woman fatally bit-

ten by the poisonous snake. But Garcilaso offers

To dramatize the loss of Eurydice, Garcilaso fo-

more than the reality of death. He presents Eurydice

cuses on the contrast between beauty and death, on

in the very act of dying, an element absent in the

the process of dying undergone by the beautiful

Italian models. As she expires, there is a sense of

woman, and the soul's departure from the

shock in the realistic rolling back of her unfocused

damaged, lovely flesh. The ancients do not describe

eyes ("los ojos ya bolviendo"), reminiscent of Ver-

the woman, but Sannazaro does, and Garcilaso

gil, where Eurydice's eyes "swim" (496) as, over-

takes his cue from him and from Ariosto's image of

come by the drowsiness of death, she is snatched a

the rose that is left unplucked in the story of Isabel

second time by the powers of the underworld.

and Zerbin in the Orlando. Ariosto depicts Isabel

By transforming Sannazaro (and possibly the Or-

as she grieves over the dying body of Zerbin, who

phei tragoedia) and adapting fragments from Ari-

has been wounded by the Tartar king Mandricard:

osto and Vergil, Garcilaso reconstructs the scene of

loss and gives it precisely the emphasis he wants: a

languidetta come rosa, rosa non colta in sua stagione, drawing out of time to make the instant of dying a

si che'lla impallidisca in su la siepe ombrosa. profound realm of its own, a passage of the beloved

from life to colorless exile from the living, the

drooping like a rose, a rose unpicked in its season and

gradual disappearance of the loved one from the

turning pale on the shady bush.

lover's grasp. Garcilaso's elegant drama of death

(24.80.4-6; trans. mine)

not only reveals his ingenuity and virtuosity, key ele-

ments prescribed for good imitation, but emerges

Garcilaso echoes Ariosto's "impallidisca" in his in a curious way as a correction of his predecessors.

"descolorida," focusing on the ominous paleness In the dialectic established between Garcilaso's text

of death. From Sannazaro's Eurydice tapestry in theand its antecedents, the ancients sin by omission

Arcadia, Garcilaso takes the reference to the white (amplification is the corrective), and Sannazaro and

foot and the exhalation of the soul: the Orphei tragoedia sin by failing to give the loss

of fragile Eurydice the proper emphasis. Garcilaso

engages his ancient models in what Bloom calls tes-

Euridice: si come nel bianco piede punta dal velenoso

sera and his Italian models in what Bloom calls

aspide fu costretta di esalare la bella anima.

clinamen (Anxiety 19-73). Garcilaso "completes"

Eurydice: how pricked on her white foot by the poisonous his ancient precursors, for they have not gone far

asp was compelled to exhale her beautiful soul. enough; he "swerves" away from his Italian sources

(196; trans. mine) and moves in a different direction, giving high

drama to the event.

Garcilaso's subversion of his models points to

But Sannazaro's image of Eurydice exhaling her their insufficiencies and achieves a secret victory

beautiful soul is changed by Garcilaso to the soul over them. The result is not only a unique poetic vi-

leaving the beautiful flesh ("el anima . . . de la sion but one that rivals the models in accuracy of

hermosa carne despidiendo"), so there is a shift presentation. And yet in the correction lies a poetic

This content downloaded from

200.16.86.81 on Fri, 06 Oct 2023 20:59:25 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

320 Garcilaso's Poetics of Subversion and the Orpheus Tapestry

strategy. Eurydice's loss must be conveyed by Gar- of the dark people.' By contrast, Vergil offers a

cilaso as a dramatic withering of beauty because her wealth of observation of his foul Hades, whose dis-

death prefigures that of Elissa, the decapitated tinctive features are its darkness and its unhappy

nymph, in the fourth tapestry. In this last tapestry, dwellers. His Orpheus enters a "grove that is murky

the mutilated body of the delicate nymph rests, like with black terror" 'caligantem nigra formidine lu-

a lifeless swan, on the luxuriant pleasance. cum' (468); its inhabitants are the shadows and

In the next stanza Orpheus descends to the un- phantoms of those deprived of light ("umbrae .

derworld, loses Eurydice a second time, and la- tenues simulacraque luce carentum" [472]). Vergil

ments her. Garcilaso departs from his models, yet offers a pathetic picture of sadness and fear: the

their intertextual presence points to a radically al- denizens of Hades are like birds hiding amidst

tered Orpheus: leaves; unmarried girls, sons who died on the pyre

before their fathers' eyes, mothers, men are all held

by the black ooze of the Cocytus and the abundant

Figurado se via estensamente

waters of the treacherous Styx (473-80). Ovid's

el osado marido, que baxava

Hades is silent and dark (10.53-54); its inhabitants,

al triste reyno de la escura gente

y la muger perdida recobrava;

like Vergil's, are umbrae-Eurydice is among them,

y c6mo, despues desto, e1, impaciente limping as she walks because of her wound, a not

por mirarla de nuevo, la tornava so unexpected playful note by the bantering Ovid

a perder otra vez, y del tyrano (48-49). But Garcilaso has no need for Vergil's ex-

se quexa al monte solitario en vano. (137-44) tensive details or, obviously, for Ovid's comedy. It

is his turn to exercise restraint. His description is

The daring husband was seen depicted at length, descend- crisp and to the point. The expected "escuro reyno

ing to the sad kingdom of the dark people and recover-

de la triste gente" 'dark kingdom of the sad people,'

ing his lost wife; and how after this, he, impatient to see

perhaps too close to the Vergilian model for Gar-

her again, lost her once more, and in vain complains to

cilaso's comfort and clearly too ordinary an expres-

the solitary mountain about the tyrant. (73)

sion for the occasion, suffers a dislocation through

a transposition of adjectives. It becomes, as we have

From the start, Garcilaso adds a distinct note. seen, "triste reyno de la escura gente," startling and

Whereas Vergil sends Orpheus into a terrifying thus pleasing in its ingenuity, as it subverts the an-

Hades but does not specifically speak of him as cient notion of the underworld. Moreover, Gar-

brave, Garcilaso actually calls Orpheus osado in cilaso's "escura gente" has a threatening tone,

describing the daring descent into the sad kingdom insisting not only on mystery but on the inaccessi-

of dark people. Here there are echoes of another bility of those who live in Hades. Eurydice, no

lover and another ancient source: Martial's audax longer the fair, luminous woman whose beauty is

Leander, who serves as a model for Garcilaso's Le- marked by her blanco pie, is one of them-and

ander in sonnet 29, "Passando el mar Leandro el equally inaccessible. The phrase escura gente

animoso" 'Crossing the sea the daring Leander.'6 presages the unhappy outcome, which is caused by

But this reminiscence is not simply a quotation Orpheus himself, the slave and tragic victim of love.

from a prestigious Latin source. In an ironic mul- Love spurs him into the impatience that causes him

tiplication of sources, Martial's text qualifies Ver- to lose Eurydice forever.

gil's, giving way to Garcilaso's text; hence there By using the epithet iinpaciente, Garcilaso shows

emerges a new, courageous Orpheus willing to sac- how different his Orpheus is from the Vergilian

rifice himself for love, like "Leandro el animoso," archetype, who is caught in a whirl offuror and de-

who swims the dangerous Hellespont to reach Hero. mentia as he leads Eurydice back to the world of the

The hyperbolic scene of the loss of Eurydice, where living (485-95).7 In Vergil, the Orpheus who con-

female delicacy and grace are ravished by urgent, quers death and the merciless powers of Hades by

untimely death, finds its counterpart in this inflated the magic of his song loses his beloved because,

passage where heroic Orpheus enters the forbidden morally weak, he cannot bridle his reckless passion.

circle of death, ready to do battle to recover his wife.Herein lies the tragedy of the Vergilian Orpheus. Al-

But curiously Garcilaso's Orpheus descends to a though at times sympathetic to Orpheus, Vergil

rather tame Hades, described in a brief phrase: condemns him for his excesses and, confirming his

"triste reyno de la escura gente" 'the sad kingdom flawed character, Eurydice reproaches him, crying

This content downloaded from

200.16.86.81 on Fri, 06 Oct 2023 20:59:25 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Mary E. Barnard 321

out, "What madness, Orpheus, what dreadful mad- light his voice is sterile. His song spins in a void; Or-

ness has ruined my unhappy self and you?" 'quis pheus has lost the power of the word as he laments

et me . . . miseram et te perdidit, Orpheu, quis on a solitary mountain. Moreover, Garcilaso

tantus furor?' (494-95). deprives him of his lyre; its absence reinforces the

Garcilaso mitigates the tragedy by diminishing notion that Orpheus has lost that special gift to cre-

the moral misdeed-frenzy and madness give way ate universal harmony, to reach nature and receive

to impatience. The Spanish poet seems to rely on its intimate response.

Ovid's version, where Orpheus is avidus, not fren- The failure of the word is a reflection of the fail-

zied or mad but "eager for sight of Eurydice" ure of love. It is not Orpheus the poet-musician but

(10.56-57). So the Vergilian Orpheus's grave moral Orpheus the failed lover who takes center stage. The

transgression is reduced in Ovid and Garcilaso to emphasis falls on his private suffering, his brood-

a lover's mistake, for which he is unreproached. In ing, and the pathos of loss and defeat, touchstones

Ovid, Eurydice does not complain; attributing of the typical tormented Garcilasian lover. Caught

Orpheus's action to love, she says merely, "fare- in his complaint against the tyrant of the under-

well." Garcilaso goes one step further: his Eurydice world who holds Eurydice captive, Orpheus will

is totally silent. Whereas the tragic element forever be the grieving lover, feeding his pain on the

persists-Orpheus yields his beloved to doom be- memory of his loss. Vergil's Orpheus can equally be

cause of a flaw in his character-Garcilaso has a loner, singing on a solitary shore (465) or in the

created a tame Renaissance lover, whom he ulti- deserted icy regions of northern Greece (517-20).

mately excuses. The love poet is, in the end, more But when the Vergilian Orpheus is placed in the "icy

interested in highlighting the sad consequences of caverns" of the Rhodope (509), he is the seductive

loving too much than in dealing with questions of lyrist who can and does move nature. Ovid's

tragic choice.8 Orpheus creates a whole forest with the power of

Garcilaso also diminishes the tragic dimensions his lyre (86-105). But Orpheus the enchanter gives

by shifting blame for Orpheus's loss to Pluto. Al- way in Garcilaso to a figure wandering in an un-

though Vergil refers to Pluto as the "ruthless ty- responsive monte. The last words are, significantly,

rant" 'immitis tyrannus' (492), he clearly blames "en vano." There remain two solipsistic entities: the

Orpheus for having broken the vow not to look solitary mountain and Orpheus in his own dispir-

back. In Vergil, Pluto and Orpheus are placed on ited wilderness.

an epic scale. Pluto appears as a terrible inhuman In transforming Orpheus, as in transforming

force that Orpheus conquers with the power of his Eurydice, Garcilaso's intertextual play with his an-

song; later, because of mad passion, Orpheus loses tecedents contains an element of correction. Gar-

out justly to his antagonist. Garcilaso, by contrast, cilaso seems to be exposing the inadequacy of the

suggests an unfairness in Orpheus's fate and has the ancients' presentation of Orpheus's response to los-

lover complain about the tyrant: "del tyrano / se ing Eurydice.9 Orpheus's lament must be a bleak,

quexa al monte solitario en vano" 'in vain com- anguished moment without the slightest hint of

plains to the solitary mountain about the tyrant.' consolation or regeneration. The silence of nature

By using the word tyrano, Garcilaso maintains matches and reinforces the silence of the under-

Pluto on the Vergilian plane of merciless power world. And also, as in the scene of Eurydice's death,

while he lowers Orpheus to the level of impatience. what we are witnessing is a specific poetic strategy.

The punishment is clearly excessive. As we shall see, Garcilaso reserves the Orphic voice

But Garcilaso's Orpheus is different from Vergil's for the lyric speaker's self-presentation as poet and

and Ovid's in a more profound way: his song no as Nemoroso's instrument to celebrate the doomed

longer enchants. In the ancient writers, Orpheus is Elissa in the fourth tapestry. The power of the word

the vates, the eloquent artist whose lyric power belongs to the singer of the eclogue-like a Ho-

moves the world and the underworld. Their meric aoidos seeking to charm his listener

Orpheus charms the spirits of Hades, including im- (49-52)-and to one of the poem's key pastoral

movable Pluto, and after Eurydice disappears for figures, the grieving shepherd.

a second time, he tames beasts and enchants trees. Garcilaso radically subverts Orpheus by leaving

Garcilaso does not mention Orpheus's magical him only his failure as a lover. In so doing, Garcilaso

song to the underworld. And, in contrast to the an- denies him his triumphant side as the magical ver-

cient models, when Orpheus sings to the world of bal artist. The role of the vates, the inspired bard

This content downloaded from

200.16.86.81 on Fri, 06 Oct 2023 20:59:25 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

322 Garcilaso's Poetics of Subversion and the Orpheus Tapestry

with his

with Orphic powers to move nature, is claimed byexalted role as a type of Christ in allegori-

cal exegeses of Ovid's Metamorphoses, such as the

the lyric "I," who, at the beginning of the eclogue,

tells Maria that his voice will celebrate her:10 Ovide moralise and Pierre Bersuire's commentary

(Bersuire circulated widely in the Renaissance): Or-

pheus the tamer of animals and Logos figure be-

Y aun no se me figura que me toca

comes Christ the Good Shepherd and Word

aqueste officio solamente'n vida,

Incarnate. This allegorical tradition was inherited

mas con la lengua muerta y fria en la boca

by Spanish writers such as Calderon, who Chris-

pienso mover la boz a ti devida;

libre mi alma de su estrecha roca,

tianizes Orpheus in his mythological auto El divino

por el Estygio lago conduzida, Orfeo. But Garcilaso kept company with a differ-

celebrando t'ira', y aquel sonido ent lot, those who found a kindred spirit in the likes

hard parar las aguas del olvido. (9-16) of Giovanni Boccaccio. In his influential Genealo-

gia deorum (c. 1370), Boccaccio stayed clear of

And I even imagine it will not be my lot totypological

performinterpretations

this of Orpheus and, even

function only in my lifetime, but with my though

tonguehe dead

did not ignore the ethical possibilities of

and cold in my mouth I intend to stir the voice owed

the myth, histo

Orpheus emerges as the gifted artist

you. My soul, free of its narrow rock and ferried across

whose genius resides in an eloquence that ensures

the Stygian Lake, will continue to celebrate you, and that

immortality (1: 245-46; 5.12).

sound will halt the waters of oblivion. (68)

The appropriation of the Orphic power in the ec-

logue not only serves for the self-presentation of the

The speaker is now a new Orpheus, an artist- lyric speaker as poet-and ensures his immortality,

magician and seer whose voice persists even after as his voice conquers death itself-but has a

death, as it records the beloved and halts the waters programmatic value. The ancient Orpheus is both

of oblivion, that is, the Lethe, twin river to the Styx. poet and seer. When the speaker becomes Orpheus-

Garcilaso's model for the Orphic voice is Vergil. In like, this act is also a rite of passage into the fantas-

the Georgics the head of the dismembered Orpheus tic world of myth, which his eyes will witness and

is swept down the Hebrus River, its "voice and his voice will reveal.

death-cold tongue" calling out Eurydice's name In addition to imitating classical models, Gar-

cilaso adapts, in the same transforming and subver-

(523-27), the devotion to his wife caught in his last

mournful sigh. Garcilaso echoes Vergil in "la len- sive manner, an essential idea of the Orphic cult

gua muerta y fria en la boca." But, whereas in Ver- that has analogues in Gnostic and Christian

gil the voice is mournful, in the eclogue it is thought: the liberation of the soul from the prison

celebratory. or tomb of the body. Following the famous line

In becoming a new Orpheus, the lyric speaker "pienso mover la boz a ti devida" 'I intend to stir

clearly draws attention to his role as poet. Thomas the voice owed to you,' the speaker says, as he be-

Greene has suggested that "imitation at its most comes a new Orpheus, "libre mi alma de su estrecha

powerful pitch required a profound act of self- roca" 'my soul, free of its narrow rock.' The "es-

knowledge and then a creative act of self- trecha roca" is clearly the body as a stone tomb. A

definition" (97). In the typical manner of other tenet in Orphism holds that "the soul is immortal

Renaissance writers, such as Spenser and Ronsard, and divine but imprisoned in a mortal, Titanic

Garcilaso arrogantly defines the lyric persona by body; therefore it becomes the duty of the follower

appropriating the voice of Orpheus, an ancient poet of Orpheus to liberate the divine, ecstatic, and pure

figure that had an enormous vogue in the sixteenth soul from the shackles of an evil body by living a

century." Along with Orpheus the priscus theolo- life of progressive ritual purification oriented

gus of the Neoplatonists and Orpheus the lover, Or- toward the attainment of immortality" (Strauss

pheus the eloquent poet had a lasting currency. It 7-8). In Renaissance Neoplatonism, especially in

is perhaps useful to remember that Orpheus came Ficino, Orpheus is the master theologian of the oc-

to the Renaissance with an illustrious medieval past cult who is supernaturally inspired with knowledge

(see Friedman and Heitmann; on Orpheus in the of both human and divine things. The Neopla-

Golden Age, see Cabafias). He is the courtier and tonists' enthusiasm for the sacral character of the

minstrel in medieval romances-the anonymous Sir Orphic hymns leads to a religious syncretism, an at-

Orfeo and Robert Henryson's Orpheus and Eu- tempt to reconcile the pagan world with the Chris-

rydice, for instance. These images contrast sharply tian (on Orpheus and the Neoplatonists, see Walker

This content downloaded from

200.16.86.81 on Fri, 06 Oct 2023 20:59:25 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Mary E. Barnard 323

and Wind). But Garcilaso eschews the Neoplatonic dependent voices. In this Chinese box of voices

way, and the reference to the soul liberated from its within voices there are four centers: (1) the narra-

imprisoning "narrow rock," a notion that could tor; (2) the epitaph's speaking letters; (3) Elissa,

easily have turned into a mystagogic discourse, is Nemoroso, and the Tagus; and (4) Eurydice and

here at the service of poetry. In leaving the body, the Orpheus, who are there by implication, through the

soul is making a poetic journey, for it carries a Orphic call and echo that we perceive intertextually

celebratory song devised by the voice of the Orphic as Garcilaso imitates the Vergilian model.

vates. Garcilaso's emphasis on oral discourse, the

And this voice does not stay behind in lofty iso- presentation of the text as emerging directly from

lation as the poem continues: it is the first voice in the mind or voice of the speaker or speakers, is an

a series of voices that show the mechanism behind attempt to escape strict rhetorical verse that sup-

the making of the poem. That complexity draws at- presses naturalness. The poet creates an illusion of

tention, in turn, to the text as an artifact. The elo- refined artlessness that calls forth a paradox simi-

quence of the game of voices-anchored on the lar to the one found in the obligatory modesty topos

notion of the Orphic-gives the poem its special at the beginning of the eclogue: the text both af-

qualities, indeed its structure and brilliance. At the firms and denies what it sets forth. The voices point

beginning of the eclogue the speaker assumes the to a spoken language, but their very existence in a

Orphic voice. Then he becomes a third-person nar- written discourse, especially an intricate one where

rator with a pastoral voice, who sings "a lowly the hand of the poet is, as we have seen, readily evi-

strain" with his "crude pampofia." The narrator,dent,

a bespeaks their artificiality. And since these

visionary endowed with the power to "see" the fan- voices exist in an intertextual space, the interplay be-

tastic, mythological world of the nymphas del Tajo, tween Garcilaso's text and its Vergilian subtext, they

tells of their stories embroidered in the four tapes- reveal the text not only as an artifact but as a prod-

tries. In the last tapestry, the narrator has a nymph uct of an act of rewriting.

introduce another voice, Elissa's, by means of an Garcilaso's Orpheus is an imitation and subver-

epitaph on a poplar whose letters speak ("que ha- sion of ancient and Italian models. A typical

blavan ansi por parte della" 'which spoke thus on Renaissance humanist, Garcilaso fully ac-

her behalf'): knowledges his predecessors, paying homage to

them even as he subverts them. At the heart of Gar-

"Elissa soy, en cuyo nombre suena cilaso's revisionist poetics lies an aesthetic opti-

y se lamenta el monte cavernoso, mism, a conviction that his rewriting of the

testigo del dolor y grave pena Orpheus myth is both a tribute to the models and

en que por mi se aflige Nemoroso an affirmation of his poetic mission. Through a

y llama 'Elissa'; 'Elissa' a boca llena multiplicity of sources, with its reconstruction and

responde el Tajo, y Ileva pressuroso correction of models, Garcilaso not only rivals the

al mar de Lusitania el nombre mifo,

accuracy of his antecedents but authenticates his

donde sera escuchado, yo lo fio." (241-48)

text, establishing his unique poetic vision: he por-

"I am Elissa, in whose name resounds and laments the trays Eurydice's loss as a dramatic destruction of

cavernous mountain, witness to the pain and heavy griefher sensual beauty and transforms Orpheus into a

which for my sake afflicts Nemoroso, and he calls out pathetic lover caught in a solitary mountain, forever

'Elissa'; 'Elissa' full-throatedly replies the Tagus, and hur- brooding his loss and deprived of the power of his

riedly takes my name to the Lusitanian Sea, where it will song. But Garcilaso's most arrogant subversion oc-

be heard, I trust." (77) curs when he appropriates the Orphic power for his

lyric speaker, who becomes a new Orpheus. In the

Elissa in turn introduces Nemoroso, in whose dis- eclogue Garcilaso brings his personages alive

embodied presence the Orphic voice surfaces once through a complex strategy of voices. This inge-

again. His voice, existing within the voice of Elissa, nious device, in the end, gives voice to a major poet,

rings out her name in glorious celebration. The Ta- in an act of self-creation. He subverts Vergil and the

gus then responds. This response is a reworking of rest to create Garcilaso de la Vega.

Vergil's version, where Orpheus's head calls out for

Eurydice and the banks of the Hebrus echo his cry. Pennsylvania State University

Here we have an extraordinary complexity of inter- University Park

This content downloaded from

200.16.86.81 on Fri, 06 Oct 2023 20:59:25 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

324 Garcilaso&s Poetics of Subversion and the Orpheus Tapestry

Notes

'My use of the term intertextuality purposely disregards istence as literary tricks. By this means he highlights the fictional

Roland Barthes's notion that the texts that make up another text dimension of his artful eclogue. On the tradition of the stabil-

are anonymous and untraceable (S/Z). Julia Kristeva, who de- ity topos, see Fernandez-Morera 82-83.

fines intertextuality as the transposition of one (or several) sys- 4 The term degollada has been the cause of much controversy.

tem(s) of signs into another (Revolution 59), does at times refer El Brocense, one of Garcilaso's sixteenth-century commentators,

to texts that can be identified (Sjmjiotik, esp. 194-95). In my was so shocked by the violence of the image that he substituted

discussion, the prior text (called subtext, source, or model) is igualada (amortajada 'shrouded') for degollada (Gallego Morell

identifiable. Harold Bloom uses the concept of intertextuality 301). Fernando de Herrera, another early commentator, took

in this restricted sense and, even though his exotic tropes are not degollada to mean desangrada 'bled to death' (Gallego Morell

useful for my purposes, some of his views on poetic influence 582). On the controversy, see Blecua 172-76, Porqueras-Mayo,

are curiously akin to those of Renaissance writers. I bring Bloom and Martinez-L6pez. Martinez-L6pez argues persuasively for

briefly into my analysis simply to establish some suggestive re- "decapitated" as the meaning of degollada.

lations between a well-known contemporary revisionist formula 5 The Orphei tragoedia, first published by Ireneo Aff6 in

and a dominant practice of the Renaissance. I have chosen the 1776, is a reworking in five acts of Angelo Poliziano's Favola di

term intertextuality because, even though it is not used in theo- Orfeo. Aff6 attributed it to Poliziano, as, later, did Carducci-

retical discussions of the Renaissance, it defines the complex re- with some reservations-and Neri. Even though subsequent

lation between Garcilaso's text and the antecedent texts it critics have attributed it to Antonio Tebaldeo (1463-1537)-a mi-

imitates. For further thoughts on intertextuality, see Riffaterre,nor poet of the court of Ferrara-authorship remains a matter

Culler, and Jenny. of conjecture. The work was very popular, and it is likely that

2 All quotations from Garcilaso's poetry are from Elias L. Garcilaso had access to it. On the question of attribution, see

Rivers's edition, Obras completas con comentario. Translations Pernicone and Mussini Sacchi. The fragment from the Orphei

are from Rivers, Renaissance and Baroque Poetry of Spain. I tragoedia cited in my text comes from Neri's edition.

have made alterations on these translations.

3 This change of direction reveals a fickleness the poet had de- 6 Cum peteret dulces audax Leandros amores

nied in the lines that immediately precede the reference to Apollo et fessus tumidis iam premeretur aquis,

and the muses: sic miser instantes adfatus dicitur undas:

"Parcite dum propero, mergite cum redeo."

(Martial 18)

Pero por mas que'n mi su fuerca prueve,

no tornard mi corac6n mudable; While bold Leander was swimming to his sweet love, and his

nunca dirdn jamas que me remueve weary head was now being engulfed by the swelling waters, so

fortuna d'un estudio tan loable. (25-28) in misery (it is said) he spoke to the surging waves: "Spare me

while I hurry there, drown me when I return."

(19; modified trans.)

But, no matter how it tests its strength on me, it will not make

my heart changeable; they will never say that I have been moved

by Fortune from so praiseworthy a purpose. (69) 7 On Vergil's Orpheus, see Otis and Segal.

8 For a modern rereading of the Orpheus myth, see Blanchot.

Blanchot relates the look by which Orpheus loses Eurydice to

("Estudio loable" refers to the task of praising the woman.) The the act of writing, to inspiration and desire (179-84).

stability topos to stay firm, a commonplace that finds antece- 9 Pigman sees a similar corrective emulation in Milton, who

dents in the ancients and the Italians, proves false since the poet exposes "the inadequacy of pagan pastoral elegy as a response

will indeed abandon his "estudio loable." The poet shows the to death" (28).

stability topos for what it is, a mere topos, by proceeding to con- 10 On the possible identity of Maria, see Garcilaso 417.

tradict it. In his atypical manipulation of the stability topos, as 11 On Spenser, see Cain; on Ronsard, see Kushner. Fernandez-

in his typical use of the modesty topos (discussed below), Gar- Morera, speaking of Garcilaso's "poetic self-awareness" in this

cilaso reveals the artificiality of these commonplaces, their ex- passage, sees the poet himself "as an Orpheus-like figure" (86).

Works Cited

Ariosto, Lodovico. Orlando furioso. Ed. Piero Nardi. Verona: tatione" di Giovanfrancesco Pico della Mirandola e di

Mondadori, 1966. Pietro Bembo. Ed. Giorgio Santangelo. Firenze: Olschki,

Barthes, Roland. "From Work to Text." Textual Strategies: Per- 1954.

spectives in Post-Structuralist Criticism. Ed. Josue V. Bersuire, Pierre. L'Ovidius moralizatus di Pierre Bersuire. Ed.

Harari. Ithaca: Cornell UP, 1979. 73-81. Fausto Guisalberti. Studj romanzi 23. Roma: La societa,

. S/Z. Paris: Seuil, 1970. 1933.

Bembo, Pietro, and Pico della Mirandola. Le epistole "De imi- Blanchot, Maurice. L'espace litte'raire. Paris: Gallimard, 1955.

This content downloaded from

200.16.86.81 on Fri, 06 Oct 2023 20:59:25 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Mary E. Barnard 325

Blecua, Alberto. En el texto de Garcilaso. Madrid: Insula, 1970. filologia. Milano: Saggiatore, 1979. 132-45.

Bloom, Harold. The Anxiety of Influence. New York: Oxford Otis, Brooks. Virgil: A Study in Civilized Poetry. Oxford: Claren-

UP, 1973. don, 1963.

. A Map of Misreading. New York: Oxford UP, 1975. Ovid. Metamorphoses. Ed. and trans. F. J. Miller. 1916. 2 vols.

Boccaccio, Giovanni. Genealogia deorum gentilium. Ed. Vin- Cambridge: Harvard UP, 1966-68.

cenzo Romano. 2 vols. Bari: Laterza, 1951. Ovide moralise. Ed. C. de Boer. Verhandelingen der Koninklijke

Cabanas, Pablo. El mito de Orfeo en la literatura espaniola. Akademie van Wetenschappen 37. Amsterdam: Muller,

Madrid: CSIC, 1948. 1936.

Cain, Thomas H. "Spenser and the Renaissance Orpheus." Pernicone, Vincenzo. "Sul testo delle opere in volgare di A.

University of Toronto Quarterly 41 (1971): 24-47. Poliziano." Il Poliziano e il suo tempo. Atti del Iv Convegno

Carducci, Giosue, ed. Le Stanze, l'Orfeo et le Rime. Firenze: Internazionale di Studi sul Rinascimento. Firenze: Sansoni,

Barbera, 1863. 1957. 83-88.

Cave, Terence. The Cornucopian Text: Problems of Writing in . "La tradizione manoscritta dell'Orfeo del Poliziano."

the French Renaissance. Oxford: Clarendon, 1979. Studi di varia umanita in onore di Francesco Flora. Milano:

Culler, Jonathan. "Presupposition and Intertextuality." The Pur- Mondadori, 1963. 362-71.

suit of Signs: Semiotics, Literature, Deconstruction. Ithaca: Petrarch. Lefamiliari. Ed. Vittorio Rossi and Umberto Bosco.

Cornell UP, 1981. 100-18. 4 vols. Firenze: Sansoni, 1933-42.

Erasmus, Desiderius. Il Ciceroniano. Ed. Angiolo Gambaro. Pigman, G. W. "Versions of Imitation in the Renaissance."

Brescia: La Scuola, 1965. Renaissance Quarterly 33 (1980): 1-32.

Fernandez-Morera, Dario. The Lyre and the Oaten Flute: Gar- Poliziano, Angelo. Opere del Poliziano: L'Orfeo et le Stanze. Ed.

cilaso and the Pastoral. London: Tamesis, 1982. Ferdinando Neri. Strasbourg: Heitz [1911].

Friedman, John. Orpheus in the MiddleAges. Cambridge: Har- Porqueras-Mayo, Alberto. "La ninfa degollada de Garcilaso

vard UP, 1970. (egloga ILL, versos 225-232)." Actas del Tercer Congreso In-

Gallego Morell, Antonio, ed. Garcilaso de la Vega y sus comen- ternacional de Hispanistas. Mexico: Colegio de Mexico,

taristas. Madrid: Gredos, 1972. 1970. 715-24.

Garcilaso de la Vega. Obras completas con comentario. Ed. Elias Riffaterre, Michael. La production du texte. Paris: Seuil, 1979.

L. Rivers. Madrid: Castalia, 1981. Semiotics of Poetry. Bloomington: Indiana UP, 1978.

Greene, Thomas M. The Light in Troy: Imitation and Discov- "Syllepsis." Critical Inquiry 6 (1980): 625-38.

ery in Renaissance Poetry. New Haven: Yale UP, 1982. "La trace de l'intertexte." Pensee 215 (1980): 4-18.

Heitmann, Klaus. "Orpheus im Mittelalter." ArchivfurKultur- Rivers, Elias L., trans. Renaissance and Baroque Poetry of Spain.

geschichte 45 (1963): 253-94. New York: Dell, 1966.

Jenny, Laurent. "La strategie de la forme." Poeitique 27 (1976): Sannazaro, Jacopo. Opere. Ed. Enrico Carrara. Torino: Unione

257-81. Tipografico-Torinese, 1967.

Kristeva, Julia. La revolution du langagepoetique. Paris: Seuil, Segal, Charles. "Orpheus and the Fourth Georgic: Vergil on Na-

1974. ture and Civilization." American Journal of Philology 87

. Sjmjiotik& Recherches pour une se6manalyse. Paris: (1966): 307-25.

Seuil, 1969. Strauss, Walter S. Descent and Return: The Orphic Theme in

Kushner, Eva. "Le personage d'Orphee chez Ronsard." Lumiere Modern Literature. Cambridge: Harvard UP, 1971.

de la Plejiade. Paris: Vrin, 1966. Virgil. Georgics. Ed. and trans. H. Rushton Fairclough. 1916.

Martial. Epigrams. Ed. and trans. Walter C. A. Ker. 1919. 2 vols. Cambridge: Harvard UP, 1965.

Cambridge: Harvard UP, 1968. Walker, D. P. "Orpheus the Theologian and Renaissance

Martinez-L6pez, Enrique. "Sobre 'aquella bestialidad' de Gar- Platonists." Journal of the Warburg Institute 16 (1953):

cilaso (egl. 111.230)." PMLA 87 (1972): 12-25. 100-20.

Mussini Sacchi, Maria Pia. "La 'Orphei tragoedia' e il suo au- Wind, Edgar. Pagan Mysteries in the Renaissance. London:

tore." In ricordo di Cesare Angelini. Studi di letteratura e Faber, 1958.

This content downloaded from

200.16.86.81 on Fri, 06 Oct 2023 20:59:25 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

You might also like

- On Evil and Suffering in Modern PoetryDocument2 pagesOn Evil and Suffering in Modern PoetryEVIP1100% (1)

- Review by Barbara D Riess El Alfiler y La Mariposaby 1998Document4 pagesReview by Barbara D Riess El Alfiler y La Mariposaby 1998Elizabeth QuintanaNo ratings yet

- HAVELOCK, Eric. Parmenides and Odysseus PDFDocument12 pagesHAVELOCK, Eric. Parmenides and Odysseus PDFbruno100% (1)

- Remembrances The Experience of Past in Classical Chinese LiteratureDocument79 pagesRemembrances The Experience of Past in Classical Chinese LiteratureoskrabalNo ratings yet

- Classical Studies: IllinoisDocument236 pagesClassical Studies: IllinoisМаша КрахмалёваNo ratings yet

- Review of Sujeto femenino y palabra poeticaDocument5 pagesReview of Sujeto femenino y palabra poeticaneobarroco71No ratings yet

- Selection Harold Bloom-Deconstruction and Criticism-Routledge & Kegan Paul PLC (1980)Document19 pagesSelection Harold Bloom-Deconstruction and Criticism-Routledge & Kegan Paul PLC (1980)Hop EfulNo ratings yet

- Article Carpentier - ProustDocument23 pagesArticle Carpentier - ProustGiovanny SalasNo ratings yet

- Ragusa BooksAbroad 1953Document3 pagesRagusa BooksAbroad 1953Ana-Maria FilipNo ratings yet

- Rosador - The Power of Magic, From Endimion To The TempestDocument14 pagesRosador - The Power of Magic, From Endimion To The TempestSophia BissoliNo ratings yet

- Havelock Par Men Ides and OdisseusDocument12 pagesHavelock Par Men Ides and OdisseusMarcello FontesNo ratings yet

- Curator As OracleDocument11 pagesCurator As OracleRevista Feminæ LiteraturaNo ratings yet

- Literary Terms and Critical Thinking TermsDocument24 pagesLiterary Terms and Critical Thinking Termsapi-269500017No ratings yet

- Shakespeare and The Theory of ComedyDocument5 pagesShakespeare and The Theory of ComedyAVRIL SOFIA GARCIA BERROCALNo ratings yet

- CLAY, Diskin. The Theory of The Literary Persona in AntiquityDocument33 pagesCLAY, Diskin. The Theory of The Literary Persona in AntiquityLucas Silvestre CândidoNo ratings yet

- Glossary of Literary TermsDocument33 pagesGlossary of Literary Termsnevanaaa100% (1)

- Greene 1993Document24 pagesGreene 1993Andrê PenicheNo ratings yet

- The Gnostics and Their Remains - Description of The Plates - Plate H. Egyptian Types (Continued)Document3 pagesThe Gnostics and Their Remains - Description of The Plates - Plate H. Egyptian Types (Continued)ColinNo ratings yet

- List of Useful TermsDocument3 pagesList of Useful TermsmmaurnoNo ratings yet

- Asociacion Internacional de Literatura y Cultura Femenina HispanicaDocument4 pagesAsociacion Internacional de Literatura y Cultura Femenina HispanicaKaren Rosentreter VillarroelNo ratings yet

- 10 Chapter 3Document73 pages10 Chapter 3Vaishnavi ChaudhariNo ratings yet

- Clarke, 1981. Homer's Readers A Historical Introduction To The Iliad and The Odyssey, Newark, 60-105.Document5 pagesClarke, 1981. Homer's Readers A Historical Introduction To The Iliad and The Odyssey, Newark, 60-105.PerseusAusKitiumNo ratings yet

- $RS5GAN3Document23 pages$RS5GAN3emna2502No ratings yet

- Alcman, Poetic Etymology Tradition and Innovation (Muses Sirens Καλλιόπα) - Evanthia T. VasalosDocument25 pagesAlcman, Poetic Etymology Tradition and Innovation (Muses Sirens Καλλιόπα) - Evanthia T. VasalosLeombruno Blue100% (1)

- Apuleius and AeneidDocument22 pagesApuleius and AeneidEduardoHenrikAubertNo ratings yet

- Cambridge University Press The Classical AssociationDocument12 pagesCambridge University Press The Classical AssociationmarcusNo ratings yet

- New Catholic Encyclopedia entry on oral transmission of literatureDocument11 pagesNew Catholic Encyclopedia entry on oral transmission of literatureGustavo Milano BeserraNo ratings yet

- Cosmic Choruses: Metaphor and PerformanceDocument24 pagesCosmic Choruses: Metaphor and PerformanceCydLosekannNo ratings yet

- Calasso - Deconstructing Mythology - FioraniDocument372 pagesCalasso - Deconstructing Mythology - FioraniGubs Saban100% (1)

- Bergal WORDPICTUREERASMUS 1985Document12 pagesBergal WORDPICTUREERASMUS 1985EiriniEnypnioNo ratings yet

- Birdsongs Celan and KafkaDocument19 pagesBirdsongs Celan and KafkamoonwhiteNo ratings yet

- Bloom, Poetry and RepressionDocument312 pagesBloom, Poetry and RepressionIvánPérez100% (3)

- Catullle VirilitDocument56 pagesCatullle VirilitMarta DonnarummaNo ratings yet

- Reliability and Evasiveness in Epic CataDocument18 pagesReliability and Evasiveness in Epic CataMatías Ezequiel PughNo ratings yet

- Prólogo Lais María de FranciaDocument7 pagesPrólogo Lais María de Franciaisabel margarita jordánNo ratings yet

- Literary TermsDocument17 pagesLiterary TermsMinh Nghĩa VõNo ratings yet

- Language, Style, and Meaning in Troilus and CressidaDocument16 pagesLanguage, Style, and Meaning in Troilus and Cressidamerve sultan vuralNo ratings yet

- Letteratura IngleseDocument35 pagesLetteratura IngleseLoris AmorosoNo ratings yet

- Tracking The Path of Transcending The Source of Creativity in Lope de VegaDocument15 pagesTracking The Path of Transcending The Source of Creativity in Lope de VegaAMTRNo ratings yet

- Concrete Poetry.Document6 pagesConcrete Poetry.camilobeNo ratings yet

- Parmenides' Journey Inspired by Odysseus' TravelsDocument12 pagesParmenides' Journey Inspired by Odysseus' Travelsthe gatheringNo ratings yet

- Poetic Prose and Imperialism: The Ideology of Form in Joseph Conrad's Heart of DarknessDocument19 pagesPoetic Prose and Imperialism: The Ideology of Form in Joseph Conrad's Heart of DarknessAlejandro AcostaNo ratings yet

- Simias of Rhodes. The Artsy Avantgardist PDFDocument39 pagesSimias of Rhodes. The Artsy Avantgardist PDFNomads RhapsodyNo ratings yet

- Why Does Prospero Abjure His "Rough MagicDocument19 pagesWhy Does Prospero Abjure His "Rough MagicStefanoDiCaprioNo ratings yet

- Ezra Pound - The Spirit of RomanceDocument256 pagesEzra Pound - The Spirit of Romancewhiteg73100% (1)

- Portals Gates - Compiled AbstractsDocument25 pagesPortals Gates - Compiled Abstractsapi-318667755No ratings yet

- Parody in The Ancient AND Medieval WorldsDocument22 pagesParody in The Ancient AND Medieval WorldsCarl FitzpatrickNo ratings yet

- The Gnostics and Their Remains - Description of The Plates - Plate D. Sigils of The Cnuphis SerpentDocument2 pagesThe Gnostics and Their Remains - Description of The Plates - Plate D. Sigils of The Cnuphis SerpentColinNo ratings yet

- Stephen Barker Canon-FodderDocument16 pagesStephen Barker Canon-FodderLeo CoxNo ratings yet

- The Oxford Book of Latin VerseDocument408 pagesThe Oxford Book of Latin VersepavleNo ratings yet

- Literary TermsDocument361 pagesLiterary TermsALINA DONIGA .No ratings yet

- OresteiaDocument310 pagesOresteiarizwanullahtahirNo ratings yet

- Book of Masks - Symbolist PoetryDocument218 pagesBook of Masks - Symbolist PoetrythephantomoflibertyNo ratings yet

- Latin Verse Anthology Spans Earliest Fragments to 5th CenDocument354 pagesLatin Verse Anthology Spans Earliest Fragments to 5th CenMarcelo Souto Maior Monteiro100% (1)

- MetamorphosesDocument54 pagesMetamorphosesDebu Bera100% (1)

- Literary TermsDocument36 pagesLiterary TermsBasheer Alraie100% (2)

- Women Traditions in Greek PoetryDocument3 pagesWomen Traditions in Greek PoetryDomínguezCicchettiMartínNo ratings yet

- Modern Humanities Research Association The Modern Language ReviewDocument3 pagesModern Humanities Research Association The Modern Language ReviewmoonwhiteNo ratings yet

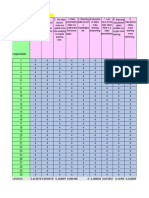

- Part 5&6.cronbach Alpha and Sample Size ComputationDocument8 pagesPart 5&6.cronbach Alpha and Sample Size ComputationHazel AnnNo ratings yet

- Journal of Cleaner Production: Fabíola Negreiros de Oliveira, Adriana Leiras, Paula CerynoDocument15 pagesJournal of Cleaner Production: Fabíola Negreiros de Oliveira, Adriana Leiras, Paula CerynohbNo ratings yet

- UNIT 4 Microwave TubesDocument39 pagesUNIT 4 Microwave TubesSnigdha SidduNo ratings yet

- Kumpulan Berenam Pandu Puteri Tunas 2022Document7 pagesKumpulan Berenam Pandu Puteri Tunas 2022Zi YanNo ratings yet

- Mock Test 2Document8 pagesMock Test 2Niranjan BeheraNo ratings yet

- Lawki Final ProjectDocument2 pagesLawki Final Projectapi-291471651No ratings yet

- ACCFA V CUGCO Case DigestDocument2 pagesACCFA V CUGCO Case DigestLoren yNo ratings yet

- Quail Eggs IncubatorDocument5 pagesQuail Eggs IncubatorMada Sanjaya WsNo ratings yet

- Theories of StressDocument15 pagesTheories of Stressyared desta100% (1)

- Curs LIMBA ENGLEZA Anul 1, Sem I - GramaticaDocument64 pagesCurs LIMBA ENGLEZA Anul 1, Sem I - GramaticaDaniel AntohiNo ratings yet

- Teacher'S Notes: Liter Ature 1ADocument3 pagesTeacher'S Notes: Liter Ature 1AAnne KellyNo ratings yet

- PERSONALITY DEVELOPMENT COURSE MODULEDocument9 pagesPERSONALITY DEVELOPMENT COURSE MODULELeniel John DionoraNo ratings yet

- Islamic Bank ArbitrationDocument27 pagesIslamic Bank Arbitrationapi-3711136No ratings yet

- Supreme Court Detailed Judgement On Asia Bibi's AppealDocument56 pagesSupreme Court Detailed Judgement On Asia Bibi's AppealDawndotcom94% (35)

- REduce BAil 22Document2 pagesREduce BAil 22Pboy SolanNo ratings yet

- Cardiac Cath LabDocument2 pagesCardiac Cath Labapi-663643642No ratings yet

- Consumer Buying Behaviour at Reliance PetroleumDocument4 pagesConsumer Buying Behaviour at Reliance PetroleummohitNo ratings yet

- Education During The Contemporary TimeDocument18 pagesEducation During The Contemporary TimeRichard Tayag Dizon100% (1)

- Cruz Vs Dir. of PrisonDocument3 pagesCruz Vs Dir. of PrisonGeeanNo ratings yet

- English - Exam ECO - 2Document6 pagesEnglish - Exam ECO - 2yogie yohansyahNo ratings yet

- Global Product Classification (GPC) Standards Maintenance Group (SMG)Document1 pageGlobal Product Classification (GPC) Standards Maintenance Group (SMG)YasserAl-mansourNo ratings yet

- English Proficiency TrainingDocument21 pagesEnglish Proficiency TrainingDayang GNo ratings yet

- What Makes A Family Strong and Successful?Document1 pageWhat Makes A Family Strong and Successful?Chinmayee SrivathsaNo ratings yet

- REVLONDocument20 pagesREVLONUrika RufinNo ratings yet

- Activity Guide and Evaluation Rubric - Activity 7 - Creating A WIX PageDocument5 pagesActivity Guide and Evaluation Rubric - Activity 7 - Creating A WIX PageLina VergaraNo ratings yet

- Extended Trumpet Techniques by Cherry Amy KristineDocument321 pagesExtended Trumpet Techniques by Cherry Amy KristineBil Smith100% (12)

- Locutionary ActDocument42 pagesLocutionary Actnandangiskandar100% (1)

- Philippine Cartoons: Political Caricatures of the American EraDocument27 pagesPhilippine Cartoons: Political Caricatures of the American EraAun eeNo ratings yet

- Brand Awareness Impact Repeat PurchaseDocument10 pagesBrand Awareness Impact Repeat Purchasegaurish raoNo ratings yet

- MGT162Document23 pagesMGT162ZulaiqhaAisya50% (2)

- The Rape of Nanking: The History and Legacy of the Notorious Massacre during the Second Sino-Japanese WarFrom EverandThe Rape of Nanking: The History and Legacy of the Notorious Massacre during the Second Sino-Japanese WarRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (63)

- Hunting Eichmann: How a Band of Survivors and a Young Spy Agency Chased Down the World's Most Notorious NaziFrom EverandHunting Eichmann: How a Band of Survivors and a Young Spy Agency Chased Down the World's Most Notorious NaziRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (157)

- Bind, Torture, Kill: The Inside Story of BTK, the Serial Killer Next DoorFrom EverandBind, Torture, Kill: The Inside Story of BTK, the Serial Killer Next DoorRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (77)

- Hubris: The Tragedy of War in the Twentieth CenturyFrom EverandHubris: The Tragedy of War in the Twentieth CenturyRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (23)

- The Prize: The Epic Quest for Oil, Money, and PowerFrom EverandThe Prize: The Epic Quest for Oil, Money, and PowerRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (47)

- Rebel in the Ranks: Martin Luther, the Reformation, and the Conflicts That Continue to Shape Our WorldFrom EverandRebel in the Ranks: Martin Luther, the Reformation, and the Conflicts That Continue to Shape Our WorldRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (4)

- Digital Gold: Bitcoin and the Inside Story of the Misfits and Millionaires Trying to Reinvent MoneyFrom EverandDigital Gold: Bitcoin and the Inside Story of the Misfits and Millionaires Trying to Reinvent MoneyRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (51)

- The Great Fire: One American's Mission to Rescue Victims of the 20th Century's First GenocideFrom EverandThe Great Fire: One American's Mission to Rescue Victims of the 20th Century's First GenocideNo ratings yet

- The Hotel on Place Vendôme: Life, Death, and Betrayal at the Hotel Ritz in ParisFrom EverandThe Hotel on Place Vendôme: Life, Death, and Betrayal at the Hotel Ritz in ParisRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (49)

- The Lost Peace: Leadership in a Time of Horror and Hope, 1945–1953From EverandThe Lost Peace: Leadership in a Time of Horror and Hope, 1945–1953No ratings yet

- Principles for Dealing with the Changing World Order: Why Nations Succeed or FailFrom EverandPrinciples for Dealing with the Changing World Order: Why Nations Succeed or FailRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (237)

- The Pursuit of Happiness: How Classical Writers on Virtue Inspired the Lives of the Founders and Defined AmericaFrom EverandThe Pursuit of Happiness: How Classical Writers on Virtue Inspired the Lives of the Founders and Defined AmericaRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Dunkirk: The History Behind the Major Motion PictureFrom EverandDunkirk: The History Behind the Major Motion PictureRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (19)

- Desperate Sons: Samuel Adams, Patrick Henry, John Hancock, and the Secret Bands of Radicals Who Led the Colonies to WarFrom EverandDesperate Sons: Samuel Adams, Patrick Henry, John Hancock, and the Secret Bands of Radicals Who Led the Colonies to WarRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (7)

- The Quiet Man: The Indispensable Presidency of George H.W. BushFrom EverandThe Quiet Man: The Indispensable Presidency of George H.W. BushRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Knowing What We Know: The Transmission of Knowledge: From Ancient Wisdom to Modern MagicFrom EverandKnowing What We Know: The Transmission of Knowledge: From Ancient Wisdom to Modern MagicRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (25)

- The Future of Capitalism: Facing the New AnxietiesFrom EverandThe Future of Capitalism: Facing the New AnxietiesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (17)

- Reagan at Reykjavik: Forty-Eight Hours That Ended the Cold WarFrom EverandReagan at Reykjavik: Forty-Eight Hours That Ended the Cold WarRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (4)

- D-Day: June 6, 1944 -- The Climactic Battle of WWIIFrom EverandD-Day: June 6, 1944 -- The Climactic Battle of WWIIRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (36)

- Never Surrender: Winston Churchill and Britain's Decision to Fight Nazi Germany in the Fateful Summer of 1940From EverandNever Surrender: Winston Churchill and Britain's Decision to Fight Nazi Germany in the Fateful Summer of 1940Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (45)

- We Crossed a Bridge and It Trembled: Voices from SyriaFrom EverandWe Crossed a Bridge and It Trembled: Voices from SyriaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (30)

- Witness to Hope: The Biography of Pope John Paul IIFrom EverandWitness to Hope: The Biography of Pope John Paul IIRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (58)

- Making Gay History: The Half-Century Fight for Lesbian and Gay Equal RightsFrom EverandMaking Gay History: The Half-Century Fight for Lesbian and Gay Equal RightsNo ratings yet

- They All Love Jack: Busting the RipperFrom EverandThey All Love Jack: Busting the RipperRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (30)

- Voyagers of the Titanic: Passengers, Sailors, Shipbuilders, Aristocrats, and the Worlds They Came FromFrom EverandVoyagers of the Titanic: Passengers, Sailors, Shipbuilders, Aristocrats, and the Worlds They Came FromRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (86)

- The Rise and Fall of the Stuart Dynasty in Britain: The History of the Stuarts from the Tudor Era to the Glorious Revolution and the JacobitesFrom EverandThe Rise and Fall of the Stuart Dynasty in Britain: The History of the Stuarts from the Tudor Era to the Glorious Revolution and the JacobitesNo ratings yet

- 1963: The Year of the Revolution: How Youth Changed the World with Music, Fashion, and ArtFrom Everand1963: The Year of the Revolution: How Youth Changed the World with Music, Fashion, and ArtRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5)