Professional Documents

Culture Documents

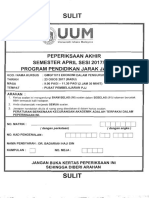

13 HPGD1103 T10

13 HPGD1103 T10

Uploaded by

aton hudaCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

13 HPGD1103 T10

13 HPGD1103 T10

Uploaded by

aton hudaCopyright:

Available Formats

Topic 10

Future Directions

By the end of this topic, you should be able to do the following:

1. Identify some methods of studying the future.

2. Critically evaluate suggestions for retooling schools.

In Topic 1, we have learned the definition of curriculum. Then, in Topics 2 till 4,

we have discussed several factors which influencing curriculum such as

philosophical beliefs, psychological perspectives, societyÊs roles and significant

historical events. After that, in Topics 5 till 8, we have examined the different

phases of the curriculum development process, starting from curriculum

planning, followed by curriculum design, implementation, and evaluation.

On the other hand in Topic 9, we focused on certain curriculum issues such as

some challenges that are impacting curriculum, differentiated curriculum for

the gifted and compensatory education. In this topic, we will discuss the future

direction of education in order to shape children to become morally responsible

and self-disciplined citizens.

Hak Cipta © Open University Malaysia (OUM)

TOPIC 10 FUTURE DIRECTIONS 251

10.1

CHARACTER EDUCATION

Character education (also called moral education or values education) has always

been the concern of educators. The focus is on how the curriculum can be

designed to teach children about basic human values such as honesty, kindness,

generosity, courage, freedom, equality, respect and so forth. Character education

aims to raise children to become morally responsible and self-disciplined citizens.

It is a deliberate and proactive effort to develop good character in students;

or, more simply, to teach students right from wrong. It is assumed that right

and wrong exist and that there are objective moral standards that transcend

individual choice. Moral standards such as respect, responsibility, honesty, and

fairness should be taught directly. Traditionally, good character is shaped by

family and religious institutions. With rising crime rates, violence among

youths, drug addiction, sexual promiscuity, breakdown of the family unit,

disrespect for authority, increasing dishonesty, and drug abuse, schools should

seriously engage in character education.

There is a kind of values vacuum further reinforced by the influence of television,

advertising and movies to the extent that traditional values have been challenged.

Religious instruction, formal or informal, parents and schools have also taken

responsibility for character education. It attempts to teach students right from

wrong and teach them a core set of values that will guide their lives towards

building a decent society. The development of good character is part of every

childÊs birthright. Parents, schools, and the community are obligated to meet

childrenÊs needs. You may have children who have not been brought up in

environments where certain values are stressed. For example, there could be

children who do not believe that honesty is important.

However, Kohn (1997) notes that school character education has tended to be

an exercise in indoctrinating students in the ways of right behaviour. The

curriculum tends to emphasise drilling students on desired behaviours rather

than engaging them in deep, critical reflection on what it means to be a moral

individual or to act morally.

Hak Cipta © Open University Malaysia (OUM)

252 TOPIC 10 FUTURE DIRECTIONS

Hunkins & A person unaware of why he or she believes or behaves even

Ornstein, when such beliefs or behaviours are good is not really a moral

(2016) person. A person of good character knows the difference

between right and wrong, knows the bases for his or her

behaviour, and chooses right over wrong, action that is of

benefit to the person and society over that which is not. There

is a difference between having a person engage in behaving

rightly and behaving morally. The latter implies an awareness

of the bases for action or non-action.

Problem solving, decision making and conflict resolution are important parts

of developing moral character. Through role-playing and discussions, students

can see that their decisions affect other people and other things. Through

such teaching-learning activities, students will understand and internalise

the desired values and habits they will require for living and maintaining their

well-being.

SELF-CHECK 10.1

1. Why should schools engage in character education?

2. What is the main weakness of teaching character education in

schools?

10.2

PERFORMANCE ASSESSMENT

An issue that has often been hotly debated relates to how students are assessed.

We have not changed much in how students are assessed in schools. Paper-and-

pencil tests dominate from primary school until secondary school and even

in higher education. Though there is consensus on the need to assess the

individualÊs overall development, assessment continues to be confined to a

segment of learnersÊ abilities. What about the affective or emotional outcomes

of education? What about the problem-solving and critical-thinking skills of

learners? They have been acknowledged as important learning outcomes but

are not adequately assessed. What options do we have?

Hak Cipta © Open University Malaysia (OUM)

TOPIC 10 FUTURE DIRECTIONS 253

One of these options is performance assessment. Performance assessment is an

assessment based on authentic tasks. These tasks are activities, problems or

exercises in which students demonstrate what they can do (McBrien et al., 1997).

Some performance tasks are designed to have students demonstrate their

ability to apply knowledge to a particular situation. For example, in an economic

lesson, students examine the price trends and production figures of petroleum

in the last five years to determine how supply and demand determine the

price per barrel. Performance tasks often have more than one acceptable solution.

Performance assessment is about performing with knowledge in a context

that relates to the real world. Learners are given opportunities to show their

understanding and ability to use knowledge differently. The goal of performance

assessment is not only to determine whether students understand but also

whether they can do what they have learned after having left school. In other

words, have the knowledge learned, skills acquired and values inculcated

have long-lasting or enduring effects.

• The implementation of performance assessment requires that one works

backwards. In other words, think first about the purpose of the assessment

and about the performances you want students to be able to do, and then

work backwards. For example, you want primary school students to be

able to write creatively. What concepts and skills do I want students to

know? At what level should my students be performing?

• Having agreed upon what you want students to perform and intend to

measure than you decide what knowledge is to be emphasised and what

skills need to be cultivated. In other words, what activities should be

introduced to provide opportunities for students to show what they can do?

For example, suppose you want primary school students to show their

creative writing skills. In that case, you should provide a topic, time and

resources that allow them to show their creative writing skills.

• After determining the activity, you need to set the criteria to indicate

whether students have acquired the knowledge and skills.

Hak Cipta © Open University Malaysia (OUM)

254 TOPIC 10 FUTURE DIRECTIONS

Why is performance assessment given importance? The reason is simple. It is what

people want from students in the real world; the ability to use wisely and

effectively what they know. We often hear society complaining that students

cannot „apply‰ their knowledge and skills in authentic situations. Society

complains because students are not provided with settings where they can

apply such knowledge and be assessed accordingly. For example, in a language

test, students may indicate that they know a story has an introduction, body

and conclusion. However, we cannot be sure that students can write a story

with these criteria. Performance assessment is vital to link school and the real

world; and give students the confidence to bridge the gap. From the studentsÊ

point of view, there is no guessing in performance assessment. Teachers

and students work together and state what needs to be improved. The role of the

teacher is more of a coach.

While there are many benefits of performance assessment, some teachers

are hesitant to implement it in the classrooms. One reason is that teachers

are not confident enough to adopt this assessment approach. The second reason

is that earlier failure with the approach have prompted some teachers to reject

the approach and to implement performance assessments in the classroom.

SELF-CHECK 10.2

1. What is performance assessment?

2. What is the rationale for encouraging the widespread use of

performance assessment in the classroom?

3. Briefly describe how performance assessment can be implemented

in the classroom.

Hak Cipta © Open University Malaysia (OUM)

TOPIC 10 FUTURE DIRECTIONS 255

ACTIVITY 10.1

Read the following text and answers the questions.

Critical Issues in Science Curriculum

The science curriculum has remained largely unchanged for decades.

Often, the natural curiosity of children, eager to understand their

surroundings, is diminished by instruction that discourages inquiry

and discovery. Science instruction has become increasingly textbook-

centred. Even though laboratory experiences are included, students

are rarely encouraged to use scientific methods to solve problems

relevant to their world perception.

A new vision of science learning is needed, calling for instructional

strategies far different from most traditional approaches. The new

paradigm for science learning should emphasise engagement

and meaning in ways that are inconsistent with past practices. The

constructivist teaching and learning models call for learning that is:

• Hands-on: Students can perform science as they construct meaning

and acquire understanding.

• Minds-on: Activities focus on core concepts, allowing students to

develop thinking processes and encouraging them to question

and seek answers that enhance their knowledge.

• Authentic: Students are presented with problem-solving activities

that incorporate authentic, real-life issues in a format that

encourages collaborative effort, dialogue with informed expert

sources, and generalisations to broader ideas and applications.

Hak Cipta © Open University Malaysia (OUM)

256 TOPIC 10 FUTURE DIRECTIONS

This approach to teaching and learning will enable students to

participate fully in a learning community where the teacher is not

the only source of knowledge and information. Technology (the

Internet) becomes a tool, supporting the learning process as students

seek new knowledge and understanding. Accordingly, teachers will

use a variety of alternative assessment (e.g. performance assessment,

portfolio assessment) tools to allow students to demonstrate their

understanding of science by solving authentic, real-life problems.

Source: Adaptation from Christensen (1995)

(a) What are the critical issues with regard to the science curriculum?

(b) Are these issues similar to the science curriculum in your school

system? Justify.

Share your answers with your coursemates in the myINSPIRE

online forum.

10.3

RETOOLING SCHOOLS FOR THE FUTURE

Mental models are how one views the world and makes decisions, which often

go unrecognised as one of the main obstacles in bringing about change in an

organisation (Senge, 1999). In education, they refer to the invisible assumptions

or beliefs educators have about their studentÊs ability to learn. According

to Senge (2000), current school systems evolved on a set of beliefs or „theories

in use‰ that (refer to Figure 10.1):

Hak Cipta © Open University Malaysia (OUM)

TOPIC 10 FUTURE DIRECTIONS 257

Figure 10.1: School Systems' Beliefs According to Senge (2000)

These are mental models that influence almost everything that is done in

schools today. For instance, knowledge is divided into sensitive topics ranging

from the Melaka Sultanate to NewtonÊs laws of motion. Each topic is taught at

appropriate time slots to learners sitting in rows listening passively, monitored

and motivated by grades. While this approach is not necessarily wrong, research

in cognitive science reveals that this approach is not compatible with how

humans learn best. Retooling schools to meet the challenges of the knowledge

economy does not mean replacing existing mental models with new ones but

rather recognising the power of mental models in limiting an educator from

thinking differently about their educational practice. More important is for

educators to suspend their mental models long enough to seek new knowledge

and to reconsider some of their beliefs about learning, thinking, and the role

of technology.

Hak Cipta © Open University Malaysia (OUM)

258 TOPIC 10 FUTURE DIRECTIONS

Bransford, Human learning is a multifaceted process that invokes

Brown and the prior knowledge of learners, is innately motivated by

Cocking(1999) the search for meaning, is influenced by emotions, is

reinforced by social negotiation, is regulated by knowledge

of cognition, is led by the construction of reality and is

enhanced in authentic situations.

In other words, learning is dynamic, and the role of educators is to facilitate

the making of dynamic knowledge. Learners need to be introduced to a world

beset with uncertainty, multiple answers and infinite possibilities involving

trial and error because that is reality. Emanating from these revised beliefs

about learning, thinking, and the role of technology, it is argued that retooling

schools be based on four guiding principles (refer to Figure 10.2):

Figure 10.2: Retooling Malaysian Schools Based on

Revised Mental Models about Learning, Thinking, and Technology

10.3.1 Schools for All

Malaysia can be proud of having made schooling accessible to most children.

Still, there is increasing awareness that it is not working for all children and

is ironically acknowledged as normal. The bell curve has made it legitimate

to say, „we canÊt educate all children because not all children are educable.‰

The tests pinned to a bell curve allow us to say that some will fail, some will

succeed, and the majority will fall in the middle. Few people realise that the

tool was designed for inanimate objects and low-level organisms and may not

necessarily apply to human beings engaged in learning. It is common practice

in our schools to label children early on. It responds to them according to the

Hak Cipta © Open University Malaysia (OUM)

TOPIC 10 FUTURE DIRECTIONS 259

labels created because of the belief that there is a certain percentage of gifted,

average, and low achievers in any classroom. Throughout the year, newspapers,

radio and television stations proudly announce schools that have obtained near-

perfect scores in national examinations.

High scorers are given extensive media coverage, but there is no mention of the

number of adolescents deficient in language, quantitative and scientific literacy

skills. There is less concern with „Why Ahmad canÊt read?‰ and a decade later

„Why Ahmad still canÊt read?‰ One can only imagine how Ahmad feels being

in a class of low achievers throughout his schooling and repeatedly told he is

not good enough. Theoretically, Ahmad should be taught by the best teachers

in the system. Still, unfortunately, the Matthew effect prevails, that can be loosely

interpreted as „those who need it donÊt get it and those who need it donÊt get.‰

It is common knowledge that learners do not do as well in environments

where adults are continually critical, constantly accentuating the negative and

not accepting them for who they are. On the contrary, students learn and thrive

in a nurturing environment. Schools must foster a warm and caring environment

in which children will bloom. From this realisation, the impetus comes to

creating schools that work for all children.

Malaysian society is rapidly changing, so educational beliefs underlie the goals

of schooling. For example, it is time that tribute is given to schools that record

the lowest number of students who cannot read and write. Schools can ill-afford

to educate just some students and ignore the rest because of examination priorities.

„No child left behind‰ (Education Act, 2001) should be the slogan for all

schools in Malaysia to ensure that schools work for all students, not just for some.

Schools should set high expectations for all students as students have a natural

inclination to rise to the level of expectation held of them (Edmonds, 1986).

Students immediately feel expectations communicated overtly or subtly by

educators. Unfortunately, many educators and schools do not effectively

communicate high expectations to all students, either because they do not have

them or because they do not believe that all children can learn. Some believe

that not all students need to realise their full potential as there are always jobs on

the farms, in the factories and low-level jobs in the service sector.

These beliefs must be revised, and educators need to believe in the incredible

potential to learn in all children and that it can be realised in all children in

any school and any classroom if the conditions are right. From the onset, students

from disadvantaged backgrounds who are at risk should be identified and

given all the cognitive coaching to succeed and not be left behind. Cognitive

strategy instruction (CSI) should be given to all academically weak students,

where „learning how to learn‰ is embedded in all instructional practices

(Phillips, 1993). In addition, schools for all must also be grounded in a value

Hak Cipta © Open University Malaysia (OUM)

260 TOPIC 10 FUTURE DIRECTIONS

system of cooperation and relationships, in contrast to the ethic of competition

and individualism. The value system of cooperation and relationship does not

discard competition, but puts it in the context of cooperation and how people

get along. Reaching goals is important, but how they are reached and with

whom is just as important.

In our increasingly diverse world, creating schools for all children is the right

thing to do, while acknowledging it is not easy. It means a major rethinking of

the core values upon which schools are built. It means focusing on both equity

and excellence in the same classroom in the same school for all children.

ACTIVITY 10.2

1. Do you agree with „the school of all‰ concept? Why?

2. To what extent is the Matthew effect common in your school?

3. „When it comes to the education of our children, failure is not

an option.‰ Do you agree with this statement?

Justify your answers to your coursemates in the myINSPIRE online

forum.

10.3.2 Thinking Goes to School

While some people would agree that developing studentsÊ thinking skills is

the main aim of education, there is less agreement on what is thinking. Over the

decades, a range of terms and definitions have been proposed, leading to further

confusion. Among the common terms used to describe thinking are reflective

thinking, critical thinking, creative thinking, lateral thinking, whole-brain

thinking, analytical thinking, mechanical reasoning, spatial thinking, logical

thinking, deductive thinking, inductive thinking, and analogical thinking to

name a few.

Fraenkel (1992) defines thinking as forming ideas, reorganising oneÊs experience

and organising information in a particular form. Chafee (1992) characterises

thinking as an unusual process for making decisions and solving problems.

According to Bourne et al. (1971), thinking is a complex, multifaceted process;

it is essentially internal, involving symbolic representation of events and objects

not immediately present but initiated by some external event. Its function is

to generate and control overt behaviour. Nickerson et al. (2014) look upon

Hak Cipta © Open University Malaysia (OUM)

TOPIC 10 FUTURE DIRECTIONS 261

thinking as a collection of skills or mental operations used by individuals.

Since thinking is a collection of mental skills, it can be performed well or poorly.

In other words,

Nickerson All people classify, but not equally perceptively,

et al.

All people make estimates, but not equally accurately,

(2014)

All people use analogies, but not equally appropriate,

All people draw conclusions, but not with equal care,

All people construct arguments, but not with equal cogency.

A synthesis of the various definitions reveals certain common threads running

through these descriptions. Thinking is a process that requires knowledge because

it is quite impossible to think in a vacuum. Thinking involves the manipulation

of mental skills; is targeted at the solution of a problem; is manifested in an

overt behaviour or ability; and is also reflected in certain attitudes or dispositions

that are indicative of good and poor thinking.

For example, a good thinker welcomes problematic situations, is open to multiple

possibilities, uses evidence skilfully, makes judgement after considering all

angles, listens to other peopleÊs views, is reflective and perseveres in searching

for information (Barron, 1987; Nickerson et al., 2014).

(a) Why has Thinking Not Been Widely Emphasised in Schools?

First, there is the belief among some educators that the development of

thinking skills should be confined to academically superior students

because they „can think‰. Teaching thinking to weak learners would be

futile and even frustrating because it is a serious mental activity

involving philosophising, deep thought, contemplation and deliberation

that would be too arduous for low achievers.

Second is the belief that students should have a complete understanding

of a subject area before they can deliberate and think about the facts,

concepts and principles. Understanding is the consequence of thinking

and if learners are taught to think about the content, then understanding

is enhanced. Educators who subscribe to this belief are preoccupied with

coverage of course content rather than ensuring understanding.

Hak Cipta © Open University Malaysia (OUM)

262 TOPIC 10 FUTURE DIRECTIONS

Third, it relates to assessment and, in particular public examinations,

which tend to test the acquisition of facts and how well learners can

remember the facts. There are few questions that demand higher-order

thinking, so schools are reluctant to venture into teaching for higher-order

outcomes.

(b) What is a „Culture of Thinking‰?

„Thinking goes to schools‰ is the title of a book by Furth et al. (1975), which

reports on a project aimed at developing the thinking ability of primary

and secondary school students based on Piagetian principles. „Thinking

will go to school‰ to when a culture of thinking permeates all Malaysian

schools where language, values, expectations, habits, and behaviour

reflect the enterprise of good thinking.

Tishman et al. (1995) identified four ways of bringing the culture of

thinking to the classroom.

• First is to have models or people who demonstrate good thinking

practices and exhibit behaviours of good thinking, such as checking

the credibility of sources or suspending judgement until all information

is available or tolerating ambiguity.

• The second is to develop thinking through explanation, whereby

teachers explicitly explain why a particular thinking skill needs to be

used, when it is to be used, and how it is to be used.

• Third is through interaction with other students, where opportunities

are given to work in groups when solving a problem, brainstorming,

and exchanging and accepting ideas.

• Fourth is feedback when teachers provide evaluative or corrective

information about studentsÊ thinking processes. For instance, a teacher

may praise students for how they arrived at a particular conclusion or

for the views expressed. Such feedback provides students with

information about their thinking behaviours which helps them become

better thinkers.

Hak Cipta © Open University Malaysia (OUM)

TOPIC 10 FUTURE DIRECTIONS 263

(c) What is the Role of Teachers?

Teachers play a crucial role in the creation of a thinking culture as they are

the ones who establish the educational climate, structure learning

experiences and have almost complete power over the processes that take

place in the classroom. In students from more affluent homes where the

parentÊs level of education is higher, questions are more frequently asked,

and the language used is relatively more complex (Sternberg & Caruso,

1985). However, students coming to school lacking the experiences of their

more affluent counterparts „succeed because of teachers who serve as

mediators of their environment; by discussing, asking questions, modelling

and teaching (Swartz and Lowery, 1989, p. 4).

Teachers have at their disposal a variety of ways to organise their classrooms

to stimulate thinking. Students need to be involved, which might take the

form of teacher-led Socratic-type discussions and cooperative small-group

or total-group investigations (Fisher, 1995). The underlying principle of

classroom organisation is to encourage greater participation of learners in

the teaching-learning process; it would be quite impossible to develop

studentsÊ thinking skills if the teacher did most of the talking.

The teacherÊs response to behaviours has a significant effect on stimulating

thinking. Most important is how teachers or even parents react to answers

given by students and whether these behaviours extend or terminate

thinking. For example, what would happen when a teacher or parent

responds to a childÊs idea with such statements as „What a dumb idea‰

or „YouÊre not good enough‰? The child might later on be reluctant to

give ideas in the future, for fear of being ridiculed or humiliated.

The language of thinking is important in encouraging thinking in the

classroom. Using specific thinking terminologies will show learners how

to perform particular skills. When used repeatedly, chances are they will

become part of their repertoire of vocabulary (Costa & Marzano, 1987).

For example, instead of saying, „LetÊs look at these two pictures‰, it would

be more precise to say, „LetÊs compare these two pictures‰.

Hak Cipta © Open University Malaysia (OUM)

264 TOPIC 10 FUTURE DIRECTIONS

SELF-CHECK 10.3

1. What is thinking?

2. Why has development thinking not been emphasised in schools?

3. How does one create a culture of thinking?

4. What is the role of teachers in developing thinking among

students?

10.3.3 Personalised Schools

Many schools have become too large and impersonal, and students are just

statistics. This observation is especially evident in urban areas where schools

have an enrolment of 1,000 to 2,000 students and some with as many as 2,500

students, which inadvertently disconnects most learners from teachers and other

adults, possibly leading to alienation, boredom and even conflict. Why should

a teenager respect a teacher who knows nothing about them? Personalised

schools are schools with a smaller student enrolment. Research is inconclusive

as to the appropriate size of such schools. Still, there is some consensus that

a primary school should not exceed 400 students and not more than 800 students

for secondary schools (Cotton, 1996). In smaller schools, teachers and students

build strong relationships. Teachers can help students learn more effectively

because they know their students as individuals. „Everybody knows your name‰.

There is also greater bonding among students as they get to know and learn

from each other.

However, even though a school may be small, it need not necessarily be

„personalised‰. Personalised schools are learning communities where students,

teachers and parents know each other personally and work together to help

young people learn and succeed. In personalised schools, students are cared for,

nurtured, and supported. This idea is significant given the increasing number

of students experiencing a lack of relationships with caring, attentive, engaged

adults when parents are working full-time. Partnerships between parents,

teachers, and administrators tend to be stronger because the opportunity to

communicate and understand each other is enhanced.

Hak Cipta © Open University Malaysia (OUM)

TOPIC 10 FUTURE DIRECTIONS 265

Generally, personalised schools have lower rates of negative social behaviour

such as classroom disruptions, vandalism, fights, thefts, substance abuse or gang

membership (Cotton, 1996). Such schools report higher school attendance and

lower dropout rates compared to larger impersonal schools. Students in smaller

schools have a greater sense of belonging, and relationship tends to be more

cordial. With the decline of the extended family and parents having to work full

time, students turn to teachers for advice and role models, which may be more

readily available in personalised schools.

10.3.4 Technology-based Schools

The unprecedented advances in internet interactivity and multimedia capabilities

are seeing the emergence of the technology-based learning environment, which

has given a new perspective to classroom learning. According to Phillips et al.

(2010), the technology-based learning environment based on a cognitive-

constructivist theoretical perspective emphasises the following seven processes

(refer to Table 10.1):

Table 10.1: Processes Implemented in Technology-based Learning Environment

Process Description

Situated Learning certain knowledge and skills is best done in situations

cognition or contexts that reflect how the knowledge will be useful in real

life. In other words, students are introduced to authentic tasks, and

the many technology tools enable the creation of microworlds

(Jonassen et al., 1998).

These are miniature environments that mimic real-world situations,

providing learners with the opportunity to apply concepts,

principles, and skills learned. For example, telecommunications

and the Internet provide access to emerging disciplinary and

interdisciplinary databases, real-time phenomena, and social

communities not accessible through print-based curricula.

Cognitive The ability to represent knowledge from different perspectives

flexibility tailored to the needs and levels of the learner. Multimedia

technology, such as virtual reality, permits knowledge and skills

to be presented in various ways, adapting content to individual

student learning styles.

Hak Cipta © Open University Malaysia (OUM)

266 TOPIC 10 FUTURE DIRECTIONS

Exploration Learners try out different hypotheses, methods and strategies to

see their effects. Computers and ancillary electronic devices

facilitate the manipulation of data and visualisation which assists

with experimenting and understanding actual, futuristic, and

hypothetical concepts, principles, relationships and probabilities.

The resources of the web and the related internet tools allow

learners to make these discoveries on their own.

Cooperative Learners work in groups by questioning each other, discussing and

learning sharing information towards the solution of a problem using

communication tools such as e-mail and chat rooms.

Collaborative Learners or groups discuss and try out their ideas and challenge the

learning ideas of others across state and international borders. For example,

a group of learners in Malaysia could be working on a project in

cyberspace on „what teenagers do besides schooling‰ with a group

of learners in Canada or Kuwait using both asynchronous and

synchronous tools. Cooperative and collaborative learning practice

are skills required in the workplace.

Articulation Getting learners to make their tacit knowledge explicit through

websites and electronic portfolios. When learners make available

to others (even across long distances) what they have done, learners

can compare strategies and provide insight into alternative

perspectives.

Reflection Learners looking back over what they have done and analysing

their performance. It enables them to see the thinking processes they

used in solving problems based on the product and determine

if their strategies were appropriate.

Technology integration into teaching and learning has not been widespread

because of defective equipment and internet connection, inadequate training of

teachers and, more importantly, a lack of understanding on how to use the

new technologies. As more schools are wired with the relevant hardware and

software, the technology-based learning environment provides a convenient

framework with a theoretical basis for the realisation of technology-based schools.

Hak Cipta © Open University Malaysia (OUM)

TOPIC 10 FUTURE DIRECTIONS 267

SELF-CHECK 10.4

1. What do you understand by personalised schools?

2. What are the processes emphasised in a technology-based learning

environment?

ACTIVITY 10.3

1. To what extent is performance assessment practised in your school?

2. Do you agree that students lack sufficient opportunities to develop

their thinking skills?

3. What do you think the curriculum of the future should be?

Explain your answers to your coursemates in the myINSPIRE online

forum.

• Character education is designed to teach children about basic human values

to raise children to become morally responsible and self-disciplined citizens.

• Performance assessment is an assessment based on authentic tasks. These tasks

are activities, problems or exercises in which students demonstrate what

they can do.

• Schools for all emphasise that an environment should be provided for all

students to realise their potential and set high expectations so that all

students will be encouraged to excel.

• A culture of thinking has to be created to encourage students to think.

• A technology-based learning environment has to be developed in as many

schools as possible in order to provide a more convenient learning

environment then the present.

Hak Cipta © Open University Malaysia (OUM)

268 TOPIC 10 FUTURE DIRECTIONS

Character education Schools for all

Culture of thinking Technology-based learning

environment

Performance assessment

Personalised schools

Barron, C. T. (1987). The process behind the process: A writing curriculum

based on theories of cognitive development.

https://scholarworks.umass.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=5246&conte

xt=dissertations_1

Bourne, L. E., Ekstrand, B. R., & Dominowski, R. L. (1971). The psychology of

thinking. Prentice Hall.

Bransford, J. D., Brown, A. L., & Cocking, R. R. (1999). The design of learning

environments. How people learn: Brain, mind, experience, and school,

117–142.

Chafee, J. (1992). Critical thinking skills: The cornerstone of developmental

education. Journal of Developmental Education, 15(3), 2.

Christensen, M. (1995). Critical issue: Providing hands-on, minds-on, and

authentic learning experiences in science. North Central Regional

Educational Laboratory. [On-line] Available: info@ ncrel. org. Retrieved on

January, 3, 2006.

Costa, A. L., & Marzano, R. (1987). Teaching the Language of

Thinking. Educational Leadership, 45(2), 29–33.

Cotton, K. (1996). Affective and social benefits of small-scale schooling. ERIC

Digest.

Fisher, R. (1995). Socratic education. Thinking: The Journal of Philosophy for

Children, 12(3), 23–29.

Hak Cipta © Open University Malaysia (OUM)

TOPIC 10 FUTURE DIRECTIONS 269

Fraenkel, J. R. (1992). Hilda TabaÊs contributions to social studies education. Social

Education, 56(3), 172–178.

Furth, H. G., & Wachs, H. (1975). Thinking goes to school: PiagetÊs theory in

practice. Oxford University Press, USA.

Hunkins, F. P., & Ornstein, A. C. (2016). Curriculum: Foundations, principles,

and issues. Pearson Education.

Jonassen, D. H., Carr, C., & Yueh, H. P. (1998). Computers as mindtools for

engaging learners in critical thinking. TechTrends, 43(2), 24–32.

Kohn, A. (1997). How not to teach values: A critical look at character education.

Phi Delta Kappan, 78, 428–439.

McBrien, J. L., Brandt, R. S., & Cole, R. W. (1997). The language of learning: A guide

to education terms. Association for Supervision and Curriculum

Development.

Nickerson, R. S., Perkins, D. N., & Smith, E. E. (2014). The teaching of thinking.

Routledge.

Phillips, S. (1993). Young learners. Oxford University Press.

Phillips, R., McNaught, C., & Kennedy, G. (2010, June). Towards a generalised

conceptual framework for learning: the Learning Environment, Learning

Processes and Learning Outcomes (LEPO) framework. In EdMedia+

Innovate Learning (pp. 2495–2504). Association for the Advancement of

Computing in Education (AACE).

Senge, P. (1999). ItÊs the learning: The real lesson of the quality movement.

The Journal for Quality and Participation, 22(6), 34.

Sowell, E. (2000). Curriculum: An integrative introduction. Prentice-Hall.

Sternberg, R. J., & Caruso, D. R. (1985). Chapter VIII: Practical modes of

knowing. Teachers College Record, 86(6), 133–158.

Tishman, S., Perkins, D. N., & Jay, E. S. (1995). The thinking classroom: Learning

and teaching in a culture of thinking. Allyn and Bacon.

Hak Cipta © Open University Malaysia (OUM)

You might also like

- Values Education (Research Paper)Document52 pagesValues Education (Research Paper)Genevie Krissa O. Gazo84% (82)

- Characteristics of An Ideal International SchoolDocument5 pagesCharacteristics of An Ideal International Schoolrachyna.annaNo ratings yet

- Lesson 2 Authentic Assessment PDFDocument6 pagesLesson 2 Authentic Assessment PDFJc SantosNo ratings yet

- Review of Richard Ashley S Untying The SDocument3 pagesReview of Richard Ashley S Untying The SBianca Mihaela LupanNo ratings yet

- I. ASSI Victor Eyo Ii. Iii. Iv. v. VIDocument7 pagesI. ASSI Victor Eyo Ii. Iii. Iv. v. VIVictor AssiNo ratings yet

- The Kalela DanceDocument3 pagesThe Kalela DanceKristýna KaňokováNo ratings yet

- Conceptual Framework and Chapter 1-3Document37 pagesConceptual Framework and Chapter 1-3Myra Lou EllaNo ratings yet

- Module 1 - Reflective Activities To Be PrintedDocument9 pagesModule 1 - Reflective Activities To Be PrintedAklilu Gulla100% (8)

- Assignment 5053Document21 pagesAssignment 5053Rosazali IrwanNo ratings yet

- Main ProposalDocument34 pagesMain ProposalRosel FajardoNo ratings yet

- AnswerDocument50 pagesAnswerdelesa abdisa100% (1)

- Compre Sample QuestionsDocument12 pagesCompre Sample QuestionsMa. Ednalyn CruzNo ratings yet

- The Impact of Teacher Performance Towards Students Learning of Khadijah Mohammad Islamic Academy As Perceived by Selected .EditedDocument30 pagesThe Impact of Teacher Performance Towards Students Learning of Khadijah Mohammad Islamic Academy As Perceived by Selected .EditedYour Academic ServantNo ratings yet

- Group Assigment CurriculumDocument3 pagesGroup Assigment CurriculumJUSMAWATI JUSMAWATINo ratings yet

- The Differences Between School Administration From School SupervisionDocument10 pagesThe Differences Between School Administration From School SupervisionMercedes A. MacarandangNo ratings yet

- Values and BeliefsDocument7 pagesValues and BeliefsKrizia May AguirreNo ratings yet

- Education Brief: School EvaluationDocument5 pagesEducation Brief: School EvaluationAayush ChapagainNo ratings yet

- Exam TipsDocument7 pagesExam TipsDavid HONo ratings yet

- Chapter 1-5Document44 pagesChapter 1-5Elain Joyce Pondalis100% (1)

- Artifact 2 - Curriculum GuideDocument6 pagesArtifact 2 - Curriculum Guideapi-279207053No ratings yet

- Final ThesisDocument43 pagesFinal ThesisEfren GuinobanNo ratings yet

- File 1Document26 pagesFile 1Fareeha ShakeelNo ratings yet

- The Difference Between An Effective School and A Good SchoolDocument2 pagesThe Difference Between An Effective School and A Good Schoolsara fahmyNo ratings yet

- Miranda, Pamela G.-Final ExaminationDocument5 pagesMiranda, Pamela G.-Final ExaminationPamela mirandaNo ratings yet

- B-Ed Thesis WrittenDocument91 pagesB-Ed Thesis Writtensamra jahangeerNo ratings yet

- Remedios D. S. Castrillo MAED - Major in Guidance and CounselingDocument7 pagesRemedios D. S. Castrillo MAED - Major in Guidance and CounselingLeila PañaNo ratings yet

- Q1: Define Consultant?: Q2: What Does ODD Mean?Document12 pagesQ1: Define Consultant?: Q2: What Does ODD Mean?Irtiza NaqviNo ratings yet

- Guidelines On Implementing Social and Emotional Learning (SEL) CurriculaDocument10 pagesGuidelines On Implementing Social and Emotional Learning (SEL) CurriculaMaria Margaret Macasaet100% (1)

- Learning To Learn HandbookDocument64 pagesLearning To Learn HandbookWill TeeceNo ratings yet

- HHHH HHHH HHHHDocument6 pagesHHHH HHHH HHHHApril SilangNo ratings yet

- SG 2 Assignment 1 2 3 4Document11 pagesSG 2 Assignment 1 2 3 4Allen Kurt RamosNo ratings yet

- FINAL EXAM PHD-SUMMER 2020 (Sanny Ferrer)Document10 pagesFINAL EXAM PHD-SUMMER 2020 (Sanny Ferrer)Joseph Caballero CruzNo ratings yet

- My Personal Reflection Draft 2Document6 pagesMy Personal Reflection Draft 2api-374467245No ratings yet

- Summary of The Study: School EffectivenessDocument43 pagesSummary of The Study: School EffectivenessKelvin ChaiNo ratings yet

- Assessment in The Affective Domain IssueDocument18 pagesAssessment in The Affective Domain IssueRittany CheahNo ratings yet

- Assessmentphilosophy 1Document6 pagesAssessmentphilosophy 1api-331573623No ratings yet

- Final Exam: Graduate School Education Central Mindanao CollegesDocument2 pagesFinal Exam: Graduate School Education Central Mindanao CollegesMark Gennesis Dela CernaNo ratings yet

- FERNANDEZ - FinallyDocument116 pagesFERNANDEZ - FinallyQueen Naisa AndangNo ratings yet

- TRF Sample Practice Objective 6 9Document3 pagesTRF Sample Practice Objective 6 9jrbuenoNo ratings yet

- Identifying Effective TeachingDocument4 pagesIdentifying Effective TeachingCary Jacot SagocsocNo ratings yet

- Activity 1-WPS OfficeDocument11 pagesActivity 1-WPS OfficeBlue MixxyNo ratings yet

- 2s-Eced03 (Task 1)Document5 pages2s-Eced03 (Task 1)Mariefe DelosoNo ratings yet

- Reflection by Unit - MACATAMPODocument10 pagesReflection by Unit - MACATAMPOAnonymous doCtd0IJDNNo ratings yet

- Learning Activity Task 6Document5 pagesLearning Activity Task 6Sheina Marie GuillermoNo ratings yet

- Admin LeadershipDocument3 pagesAdmin LeadershipSheila Grace LumanogNo ratings yet

- Set BDocument9 pagesSet BSTA. FE NHS ICTNo ratings yet

- Policy Brief - Social and Emotional Learning (2015)Document56 pagesPolicy Brief - Social and Emotional Learning (2015)Daniela DumulescuNo ratings yet

- Adrianna Mcquaid Task # 5 Leading For School ImprovementDocument7 pagesAdrianna Mcquaid Task # 5 Leading For School ImprovementAdrianna McQuaidNo ratings yet

- CareforkidsbookDocument16 pagesCareforkidsbookapi-280988126No ratings yet

- 8602-1 M.FarhanDocument35 pages8602-1 M.FarhanMalik Farhan AwanNo ratings yet

- PriyaDocument12 pagesPriyaAnonymous rIHz6wD79tNo ratings yet

- Stop & Think Research Foundation Article 05Document15 pagesStop & Think Research Foundation Article 05Caspae Prog AlimentarNo ratings yet

- Act1m2 L4Document3 pagesAct1m2 L4Harvs MonforteNo ratings yet

- Thoughtful Assessments in The New Normal - Approaches and Strategies For Formative and Summative AssessmentsDocument6 pagesThoughtful Assessments in The New Normal - Approaches and Strategies For Formative and Summative AssessmentsMary Joy FrondozaNo ratings yet

- ED701 - Course-Synthesis ADocument7 pagesED701 - Course-Synthesis AJomaj Dela CruzNo ratings yet

- Exam in Educational LeadershipDocument5 pagesExam in Educational LeadershipJacquiline TanNo ratings yet

- Higher Order Thinking Skill NotesDocument3 pagesHigher Order Thinking Skill NotesHuiping LuNo ratings yet

- Rja Final CorrectDocument7 pagesRja Final CorrectTraci ThomasNo ratings yet

- Ed 1o1 Modules 1 and 2Document18 pagesEd 1o1 Modules 1 and 2Abdulhamid Baute CodaranganNo ratings yet

- Strategies For Improving Competence Based Education in Tanzania:Experiences, Insights and PossibilitiesDocument14 pagesStrategies For Improving Competence Based Education in Tanzania:Experiences, Insights and PossibilitiesEmmanuel A. MirimboNo ratings yet

- Affective AsssessmentDocument25 pagesAffective AsssessmentDomingo CamilingNo ratings yet

- Leadership and Excellence in Schooling: Excellent Schools Need Freedom Within BoundariesDocument14 pagesLeadership and Excellence in Schooling: Excellent Schools Need Freedom Within BoundariescrisspictNo ratings yet

- The Psychology of Effective Education: Education and LearningFrom EverandThe Psychology of Effective Education: Education and LearningNo ratings yet

- Topic 1 HPGD1103 Curriculum Development - RMDocument13 pagesTopic 1 HPGD1103 Curriculum Development - RMaton hudaNo ratings yet

- Topic 2 - Philosophical Foundations of CurriculumDocument51 pagesTopic 2 - Philosophical Foundations of Curriculumaton hudaNo ratings yet

- 14 Hmef5023 T10Document16 pages14 Hmef5023 T10aton hudaNo ratings yet

- 01 HPGD1103 Cover CPDocument2 pages01 HPGD1103 Cover CPaton hudaNo ratings yet

- 11 HPGD1103 T8Document25 pages11 HPGD1103 T8aton hudaNo ratings yet

- 12 HPGD1103 T9Document13 pages12 HPGD1103 T9aton hudaNo ratings yet

- 04 HPGD1103 T1Document24 pages04 HPGD1103 T1aton hudaNo ratings yet

- Topic 3 Psychological Foundations of Curriculum - RMDocument83 pagesTopic 3 Psychological Foundations of Curriculum - RMaton hudaNo ratings yet

- 10 HPGD1103 T7Document28 pages10 HPGD1103 T7aton hudaNo ratings yet

- 3879 SITI AISHAH BINTI ADNAN s253721 Comparative Individual Assignment 73526 315203905Document14 pages3879 SITI AISHAH BINTI ADNAN s253721 Comparative Individual Assignment 73526 315203905aton hudaNo ratings yet

- Gmga3063 Essay Ja201Document4 pagesGmga3063 Essay Ja201aton hudaNo ratings yet

- AssignmentDocument5 pagesAssignmentaton hudaNo ratings yet

- Bkal1013 10 2017 2018Document21 pagesBkal1013 10 2017 2018aton hudaNo ratings yet

- Universal Studio Singapore Uss: Validity: 10 May - 31 December 2019 (Subject To Change)Document3 pagesUniversal Studio Singapore Uss: Validity: 10 May - 31 December 2019 (Subject To Change)aton hudaNo ratings yet

- Unit Two Sightseeing: Before You ReadDocument12 pagesUnit Two Sightseeing: Before You Readaton hudaNo ratings yet

- Unit 6Document8 pagesUnit 6aton hudaNo ratings yet

- GMGF1013 April 2017 2018Document12 pagesGMGF1013 April 2017 2018aton hudaNo ratings yet

- Secrets of The Aether - Final PDFDocument315 pagesSecrets of The Aether - Final PDFote100% (1)

- List of LSCs-18-05-2015Document5 pagesList of LSCs-18-05-2015AsitKumarNo ratings yet

- PharmacoepidemiologyDocument2 pagesPharmacoepidemiologyFyrrNo ratings yet

- David Abram The Spell of The Sensuous (4 Chap)Document6 pagesDavid Abram The Spell of The Sensuous (4 Chap)kabshiel86% (7)

- BSN - It Era Syllabus 2022 2023Document7 pagesBSN - It Era Syllabus 2022 2023Donie DelinaNo ratings yet

- 2nd Year Anatomy PDFDocument11 pages2nd Year Anatomy PDFFaridaNo ratings yet

- FST-01 12 IGNOU PaperDocument8 pagesFST-01 12 IGNOU Papermithu11No ratings yet

- COPERNICANDocument17 pagesCOPERNICANHellery MoradilloNo ratings yet

- Journal Icarus Pluto Ceres: What Makes A Planet?Document6 pagesJournal Icarus Pluto Ceres: What Makes A Planet?Sukesh DebbarmaNo ratings yet

- Calibration Certificate: MechanicalDocument2 pagesCalibration Certificate: MechanicalAmit KumarNo ratings yet

- James S. Coleman Consensus and Controversy (Clark J., 1996)Document506 pagesJames S. Coleman Consensus and Controversy (Clark J., 1996)diego quNo ratings yet

- Encountered Problems Ancient TimesDocument11 pagesEncountered Problems Ancient TimesKittyjoy FugabanNo ratings yet

- Constructivism PPT Group 4Document9 pagesConstructivism PPT Group 4FikriNo ratings yet

- Applied EconomicsDocument6 pagesApplied Economicskaren bulauanNo ratings yet

- Actuarial Exemptions 2023Document1 pageActuarial Exemptions 2023Irfaan CassimNo ratings yet

- (Download PDF) Introduction To Quantitative Data Analysis in The Behavioral and Social Sciences Michael J Albers Online Ebook All Chapter PDFDocument42 pages(Download PDF) Introduction To Quantitative Data Analysis in The Behavioral and Social Sciences Michael J Albers Online Ebook All Chapter PDFpeter.hamilton807100% (5)

- Science ProcessDocument32 pagesScience ProcessPrince ZaplaNo ratings yet

- The Shroud and The 'Historical Jesus' PDFDocument19 pagesThe Shroud and The 'Historical Jesus' PDFAlice GinaNo ratings yet

- Research Methods in Human-Computer Interaction Second Edition Lazar, Feng, and Hochheiser Chapter 3: Experimental DesignDocument19 pagesResearch Methods in Human-Computer Interaction Second Edition Lazar, Feng, and Hochheiser Chapter 3: Experimental DesignLucas GuarabyraNo ratings yet

- Conceptual Framework: A Step by Step Guide On How To Make OneDocument4 pagesConceptual Framework: A Step by Step Guide On How To Make OnePearl CabigasNo ratings yet

- Positive and Normative Accounting Theory: Definition and DevelopmentDocument10 pagesPositive and Normative Accounting Theory: Definition and DevelopmentPhượng ViNo ratings yet

- Developing A Theoretically Founded Data Literacy Competency ModelDocument10 pagesDeveloping A Theoretically Founded Data Literacy Competency ModelReksiana AnaNo ratings yet

- The Profound Greed: Understanding HumanDocument16 pagesThe Profound Greed: Understanding HumanSashie Sophia DadulNo ratings yet

- QUALI vs. QUANTIDocument26 pagesQUALI vs. QUANTISeraphine ZalduaNo ratings yet

- Ahmed Indivitual ReportDocument11 pagesAhmed Indivitual ReportsamNo ratings yet

- 03 Int Brazil Stages1to6 ScienceDocument21 pages03 Int Brazil Stages1to6 ScienceThiago Henrique SantosNo ratings yet

- Isda 1Document39 pagesIsda 1ショーンカトリーナNo ratings yet