Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Use of Incident Command System

Uploaded by

Oktomi WijayaCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Use of Incident Command System

Uploaded by

Oktomi WijayaCopyright:

Available Formats

CONCEPTS IN DISASTER MEDICINE

Use of Incident Command System for Disaster

Preparedness: A Model for an Emergency Department

COVID-19 Response

Andra Farcas, MD; Justine Ko, MD; Jennifer Chan, MD, MPH ; Sanjeev Malik, MD;

Lisa Nono, BS; George Chiampas, DO

ABSTRACT

The COVID-19 pandemic has placed unprecedented demands on health systems, where hospitals have

become overwhelmed with patients amidst limited resources. Disaster response and resource allocation

during such crises present multiple challenges. A breakdown in communication and organization can

lead to unnecessary disruptions and adverse events. The Federal Emergency Management Agency

(FEMA) promotes the use of an incident command system (ICS) model during large-scale disasters,

and we hope that an institutional disaster plan and ICS will help to mitigate these lapses. In this article,

we describe the alignment of an emergency department (ED) specific Forward Command structure with

the hospital ICS and address the challenges specific to the ED. Key components of this ICS include a

hospital-wide incident command or Joint Operations Center (JOC) and an ED Forward Command. This

type of structure leads to a shared mental model with division of responsibilities that allows institutional

adaptations to changing environments and maintenance of specific roles for optimal coordination and

communication. We present this as a model that can be applied to other hospital EDs around the country

to help structure the response to the COVID-19 pandemic while remaining generalizable to other

disaster situations.

Key Words: communication, coordination, COVID-19, disaster preparedness and response, incident

command system

S

ignificant advances have been made in the The global community, specifically hospital-based

realm of disaster preparedness over the past responses, are currently facing unprecedented chal-

few decades. Models and systems, such as the lenges responding to the outbreak of the novel severe

United States National Incident Management System acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS

(NIMS), have been created to address challenges relat- CoV-2) causing coronavirus disease 2019

ing to communication, resource use, and coordination (COVID-19). Hospitals across the world are evaluat-

of efforts.1-3 ing and caring for rising numbers of infected patients,

despite limited resources and increasing community

Valuable lessons were learned from notable past dis- panic. Prior efforts with multi-agency incident com-

aster scenarios, such as Hurricane Katrina and the mand systems (ICS) have proven effective for mass

Boston Marathon bombings. In the former, commu- gatherings, such as the Chicago Marathon, and similar

nication was problematic as both cellular towers and concepts can be translated to the current disaster state.

landlines stopped working; hospitals switched to using Similarly, ICS principles have been used to organize

ham radios and walkie-talkies as a result.4 During the responses to other major disasters and disease out-

Boston Marathon bombings, communication also breaks. In more recent years, responses for disease

became a problem when the cellular towers were shut outbreaks, such as the US response to Ebola and

down, as the primary interdepartmental method of Zika, have required coordinated efforts through an

communication was by means of cell phones.5 This ICS.7 Additionally, during the outbreak of SARS

resulted in delays in treatment and redundant trips in Taiwan and the initial H1N1 influenza outbreak

and actions. Through these examples, breakdowns in Mexico, an ICS structure was adopted by respec-

in communication were made evident. Uncertainty tive health authorities to help organize responses.8,9

related to command structures, roles, and relationships In the current disaster, the emergency department

led to confusion and limited a coordinated response.6 (ED) serves at the frontlines and, therefore, has a

Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness 1

Copyright © 2020 Society for Disaster Medicine and Public Health, Inc. This is an Open Access article, distributed under the terms of the Creative

Commons Attribution licence (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted re-use, distribution, and reproduction in

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 165.215.209.15, on 01 Dec 2020 at 04:27:05, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at

any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. DOI: 10.1017/dmp.2020.210

https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/dmp.2020.210

Incident Command System for COVID-19 Response

vital role in preparedness and response. It follows that an The federal government requires the use of NIMS and ICS

ICS structure adapted to respond to the COVID-19 pan- to structure a response to disaster scenarios.13 The ICS struc-

demic needs to include an ED component to be maximally ture is used at all levels of a disaster response, from single

efficient. departments to entire hospitals and, on a broader scale, at

the city, state, and federal levels. These individual ICS

Using guidelines from the Federal Emergency Management structures integrate in a clearly defined manner, which is

Agency (FEMA), we believe that a unified command critical for coordinating an efficient response in a disaster

approach within the ED during this unprecedented time situation. It is also important to ensure that implementing

can alleviate tasks and help coordinate a joint effort among the ICS structure enhances response activities rather than

hospital stakeholders.10 In this article, we specifically describe encumbers them.14 We have, therefore, similarly adapted

the ICS at our institution during the COVID-19 pandemic, these principles to structure and enhance our hospital’s

focusing on the unique aspect of the ED serving as the response to the current COVID-19 pandemic.

Forward Command, which FEMA defines as the location

nearest to the affected area used to direct activities and coor-

dinate field teams.11 We believe that similar command struc- SHARED MENTAL MODEL

tures and unified commands can assist hospitals in managing During a disaster, decisions are often complex and fluid. They

this growing pandemic and other analogous disasters. involve multiple stakeholders at various levels of command

and authority with a wide array of backgrounds and experi-

ences throughout different agencies. Decision-making in a

FEMA AND US FEDERAL GUIDELINES disaster situation needs to be dynamic and distributed across

Under the Department of Homeland Security, FEMA devel- different agencies that share common goals.1 It can often be

oped NIMS so that communities could create a “common, difficult to unify everyone’s thoughts and objectives, which

interoperable approach to sharing resources, coordinating can have consequences on the efficiency of the disaster

and managing incidents, and communicating information.”10 response. Therefore, it is important to have a shared mental

This system was first implemented in 2004 in the aftermath of model (SMM) to enhance teamwork, and a lack thereof can

the 9/11 terrorist attacks. NIMS focuses on 3 pillars for the be an obstacle to interagency coordination. SMMs provide

foundation for incident management: resource management, information to all of the team members regarding individual

coordination and command, and communication and infor- responsibilities. The model facilitates synergy between various

mation management, while it is also guided by flexibility, parts of the team when a task needs to be achieved by inter-

standardization, and unity of effort.10 dependent work.15 Stout et al. showed that high-quality plan-

ning led to the development of a better SMM and performance

The notion of the ICS resulted from the development of NIMS in a teamwork scenario.15 During an inter-agency response to a

and was defined as a “standardized approach to the command, railway accident in the United Kingdom, a poorly distributed

control, and coordination of on-scene incident management SMM contributed to difficulty in coordination.1

that provides a common hierarchy within which personnel

from multiple organizations can be effective.”10 It centers We believe that the planning involved with setting up the pro-

around having a predetermined chain of command that allows posed ICS structure and the structure itself helps encourage an

for a unified approach with a clear line of authority. It focuses SMM in disaster situations where coordination among various

on communication, especially interagency, and facilitates team members may otherwise be a point of weakness. During

multiple agencies working together while allowing each the COVID-19 pandemic, our SMM encompasses the judi-

agency to maintain their own authority.10 At its core, it is cious use of resources, such as personal protective equipment

designed to alleviate “confusion regarding authorities and (PPE), isolation of the infected population, and protection

responsibilities” and reduce “resource shortages and misdirec- of staff. This SMM enables hospital departments to work

tion of existing resources.”12 ICS also centers around the con- together during a surge to limit nonemergent visits and to focus

cept of a unified approach, so there is no single commander in on protocols to ensure staff protection. It is also important that

the system but instead a unified set of objectives. This allows there is an SMM at each level of the hospital ICS. At the ED

for full cooperation between various stakeholders and a union level, it is critical that all parties share an SMM to design our

of similar goals and expectations. Each agency is responsible for ICS structure.

presenting and sharing its agency-specific information, such as

resource availability, limitations, and conflicts.10 These are

crucial concepts in disaster environments, where an organized ED FORWARD COMMAND

and coordinated response can minimize confusion while main- At the heart of our ICS model is the ED Forward Command.

taining efficiency. The COVID-19 pandemic is an example of While the concept of a forward command, or a physical space

a complex unprecedented disaster and public health crisis nearest to the affected area where representatives of different

requiring the efficient coordination of interdependent agen- agencies gather to coordinate and direct activities, is com-

cies with various activities. monly used in other ICS structures, the concept of the ED

2 Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 165.215.209.15, on 01 Dec 2020 at 04:27:05, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at

https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/dmp.2020.210

Incident Command System for COVID-19 Response

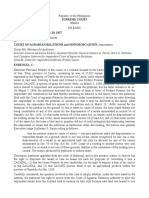

FIGURE 1

Emergency Department Incident Command System Structure

serving as Forward Command in a hospital ICS is a fairly An ED’s typical leadership structure can serve as the starting

unique one.11 In designing this concept, we looked to the point for a forward command structure, which is how it was

Chicago Model, a comprehensive disaster preparedness model formed in our ICS. Instead of the external agencies involved

for large mass gatherings, which uses an on-site Forward in a traditional interagency/interdepartmental model, an ICS

Command.2,16 This model has been used to coordinate structure at the ED level is composed of ED leadership split

the Chicago Marathon, one of the world’s largest marathons into various areas of focus that function much like agencies

with over 45,000 annual participants. Although a large mass do in the traditional ICS structure. Although existing ED lead-

gathering event does not translate directly to an active large ership roles are a good organizational starting point, it is critical

scale disaster response, the Chicago Model does represent a to adapt this to the needs of a particular incident or disaster.

robust approach to establishing a framework to best respond While a common academic ED model may not apply to a more

to a complex large scale event.2 clinically oriented disaster, items such as effects on research,

educational mission, trainee safety, and wellness are unique

In the midst of a pandemic, the forward command concept aspects that warrant dedicated focus.

can be easily translated to the ED, which is at the frontlines

of this COVID-19 crisis. EDs around the country are the

front doors through which COVID-19 patients enter into INCIDENT COMMAND STRUCTURE ROLES

the hospitals and, along with intensive care units and gen- The ICS model’s unified command theory allows for the

eral medicine floors, are the areas of the hospital most burden of response to be widely dispersed but interconnected

involved with the response to this pandemic.17 Because emer- with a common goal. It helps avoid overwhelming a single

gency staff are the first to interact with and treat affected individual or department and instead spreads the unprec-

patients, as well as are in direct contact with first responders, edented increase in workload across a larger group of stake-

they are able to see the day-to-day changes in the course of the holders. Our ICS structure and involved areas of focus

pandemic and understand which response strategies are effi- during the COVID-19 pandemic or other similar disasters

cient and which need to be changed. Similar to agencies can be seen in Figure 1. In our top-down model, the hospital

gathering in the Forward Command in the Chicago Model, Incident Command serves as the Joint Operations Center

representatives from various areas of focus come together in (JOC) and is the overall decision-maker for the incident.

the ED. This allows for real-time updates and an organized The emergency department falls under the Operations sec-

approach to solving problems from those experiencing them tion chief and serves as Forward Command, managing the

firsthand. It, therefore, follows that the ED is the department interdepartmental work of multiple areas of focus. Each of

best suited operationally and physically to serve as the Forward these areas has their own set of roles and responsibilities.

Command. A manager or representative is assigned for each area and

Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness 33

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 165.215.209.15, on 01 Dec 2020 at 04:27:05, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at

https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/dmp.2020.210

Incident Command System for COVID-19 Response

serves as the liaison between their staff and the Forward visitations. Specifically pertinent to the current COVD-19

Command team. pandemic, the Operations team also serves as the liaison with

the infection control department and helps manage personnel

exposures to the virus.

Communications

This area is responsible for relaying ED-specific information to

hospital media relations, hospital leadership, and ED person- Logistics

nel. It is also responsible for communicating externally with Logistics is responsible for department strategy and ensuring

the approval of the JOC. It is tasked with creating a daily sit- all processes and protocols involving resources and personnel

uation report that provides a composite timely overview of are implemented. This includes overseeing the supply chain,

both the system-wide and ED-focused responses and incorpo- relationships with consultants, and department throughput.

rates ICS structural updates. Having a single team managing Crucial to the current pandemic, Logistics is responsible for

communication helps to limit misinformation to personnel ensuring adequate PPE is available for personnel, as well

and the public, which is especially important in a situation as other vital supplies for patient care. Additionally, in

where clear and concise communication is vital for operations our hospital, creative innovations have been set in place to

and mitigating staff and public panic. help minimize potential exposures to consultants. For exam-

ple, we have been implementing telemedicine practices by

means of phone and video interviews when in-person consul-

External Affairs

tation is not crucial. Logistics also oversees ED throughput

External Affairs is the area that oversees emergency medical

and has coordinated ways to improve this through actions,

services, community education, social services, and health sys-

such as delaying elective surgical cases to make inpatient

tem integration. It interacts with public/private partnerships,

beds available.

outside hospitals and care providers, as well as with local gov-

ernment, to provide community resources. For example, it

engages with community partners to tackle the challenges that Research

COVID-19 poses to the homeless population and coordinates Research is tasked with keeping abreast of new developments

with city-wide actors who are establishing a large field hospital and discoveries. This is especially important in the current

for COVID-19 patients. pandemic, as COVID-19 is a novel virus and new information

is surfacing on a daily basis. The Research team serves as a con-

duit for sharing the broader research efforts within the hospital,

Administration

including the development of novel treatments. It also works

Administration leads all financial and necessary administra-

to develop protocols that may lead to new practices while nav-

tive duties related to the ED and the current crisis. Examples

igating potentially difficult ethical pathways. The Research

include establishing policies for furloughed workers and

team is also faced with new challenges, especially with patient

expedited credentialing processes to allow surge staffing

enrollment, and has needed to adapt to changes with patient

from the labor pool if necessary.

interactions.

Operations

Education

Operations oversees all ED clinical procedures, patient care,

Education’s role is to consolidate all digital, written, and aca-

and personnel across the department. One of the main roles

demic material that is pertinent to the current pandemic. It is

during the pandemic is patient care, which includes innovative

tasked with disseminating this information to all ED stake-

ways to prepare for anticipated patient surges. Operations must

holders to ensure consistent care across various individuals.

adapt to the challenges of the particular incident. In our depart-

In a teaching hospital, Education is also responsible for ensur-

ment, a temporary COVID-19 unit (“COVID tent” in Figure 1)

ing the continuing education of trainees in a safe manner. The

is set up outside of but adjacent to the ED to accommodate an

COVID-19 pandemic creates some unique challenges to the

influx of patients who require testing but may not need hospi-

typical academic teaching model and educational curriculum.

talization. Additionally, the risk of health-care worker expo-

Enhancements to videoconferencing and asynchronous

sures experienced in other parts of the world prompted a

learning have been created to maintain an adequate trainee

change to typical airway management in the ED: a dedicated

environment.

airway support team was created, which helps to ensure

intubations are carried out in the safest manner possible.

Operations is also responsible for staffing the department, Staff Affairs

which has required significant changes to adapt to a new Staff Affairs covers all entities that relate to supporting

patient population. Resource allocation and ethics also fall the individual needs of staff members. This may include

within this domain. The high transmission rates for COVID-19 coordination of support resources from the community and

has created unique circumstances and ethical dilemmas during food for personnel. Importantly, it is also responsible for

patient care, such as early intubations and limiting family addressing wellness and peer support by monitoring staff’s

4 Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 165.215.209.15, on 01 Dec 2020 at 04:27:05, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at

https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/dmp.2020.210

Incident Command System for COVID-19 Response

physical and emotional health during the crisis. It aids as et al. reported that teams that used more efficient communica-

needed with interventions, such as securing meals, involving tion methods performed better than teams that did not.15

chaplain services, and identifying measures for physical, fam-

ilial, and psychological decompression and mitigation. Other As learned from the Boston Marathon bombings and

wellness initiatives include optional debriefing conference Hurricane Katrina, having backup systems of communica-

calls, as well as weekly emails with wellness-based reads and tion in place is crucial.4,5 While not as directly applicable

uplifting news. to a viral pandemic given the anticipated course does not

involve loss of phone towers, these lessons nonetheless

In our department, these roles are filled by ED attending physi- emphasize the importance of contingency plans.

cians, administrators, nursing leadership, and a data analyst in

management and leadership roles. Resident physicians, nurses, The primary method of communication within our ICS struc-

and other allied health workers work under their management. ture involves a daily conference call with ICS managers. There

In a disaster, clear and decisive structure is critical to manage- is also an editable, Web-based document that is updated daily

ment, and individuals are selected who can not only best and accessible by all stakeholders. There are radios for backup

manage teams and tasks to meet the goals of the particular if these 2 forms of communication were to fail.

role but also embrace the shared mental model to influence

the mission. Some roles coincide well with a leader’s prior The primary method of communication outward to personnel

base of expertise, such as the Medical Director and an ED is by means of near-daily email updates from Communications.

Nurse Manager leading Operations or Vice Chair of Research These mainly address protocols and practices, as well as new

leading Research. However, other roles are assigned to support research and pertinent educational materials. They are organ-

the needs of the incident. Staff Affairs is a role that requires ized into main ICS-based categories (eg, Operations, Logistics,

unique communication and collaboration skills along with Staff Affairs, etc.). Personnel can also opt in to access updates

extensive community relationships. In this response, this role in the virtual space by means of a Web-based conference call

is co-led by the Vice Chair of Academics and an ED Nurse led by ED Forward Command that takes place 2 d/wk.

Manager with this experience. External Affairs is headed by

an attending with medical directorship experience for events

outside the ED. The Administration role is led by the LIMITATIONS

Department Administrator, while Analytics is provided This model is not without limitations. Primarily, this is 1 hos-

by the department’s Data Analyst. pital’s newly developed model for responding to a quickly-

changing disaster situation. Although there is constant feed-

As described, each of these stakeholders has an area of focus back and improvement internally, there is not as of yet any

for which they can offer their expertise and relevant points data to allow for an objective evaluation of such an approach.

of contact. This enables efficient and goal-directed responses. Further objective analysis of the efficiency and usefulness of

For instance, the COVID-19 pandemic caused a unique chal- this model is needed.

lenge with safely performing intubations and other aerosolizing

procedures. To conserve vital PPE and limit unnecessary Furthermore, this model was developed in a large academic

provider exposure, multiple areas of focus worked together hospital in an urban environment and is, therefore, most appli-

to create a protocol outlining the necessary equipment, person- cable to similar EDs. It may be challenging for smaller hospitals

nel, and procedures with input from various stakeholders. and EDs to implement, as they may not necessarily have the

Members from Operations for personnel and patient care, staff or capabilities. Additionally, some hospitals may not have

Logistics for supplies, Education for trainee education, and a need to address educational or research challenges. However,

Communications for dissemination of protocols all collabo- it is possible that the areas of focus can be combined for a more

rated and rapidly developed a solution to a new problem. compact approach to the model, requiring fewer stakeholders.

This example highlights the importance of the ICS structure

and Forward Command on a departmental level. Another evident limitation is that key leaders of the ICS

also serve as staffing personnel. This may be challenging

in the efficiency and timing of key communications but will

COMMUNICATION METHODS be addressed in the after action.

Particular emphasis was placed on communication methods

within our department. This includes communication and

leadership within a specific area of focus so that all team mem- CONCLUSIONS

bers are united in their actions. More importantly, however, it While disaster preparedness has developed significantly, the

involves sharing ideas and adaptability among the different COVID-19 pandemic has led to novel and unprecedented

areas of focus, as well as communication with personnel. As demands on the health-care system. Using principles of NIMS

the situation within the current COVID-19 climate is ever- and lessons learned from prior disasters and the successful

changing, frequent precise communication is crucial. Stout implementation of similar systems in mass gatherings, we have

Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness 55

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 165.215.209.15, on 01 Dec 2020 at 04:27:05, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at

https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/dmp.2020.210

Incident Command System for COVID-19 Response

developed a top-down approach to setting up an ICS in our 5. Hemingway M, Ferguson J. Boston bombings: response to disaster. AORN

hospital with the ED as the Forward Command. We propose J. 2014;99(2):277-288. doi: 10.1016/j.aorn.2013.07.019

6. Jensen J, Thompson S. The Incident Command System: a literature

that, in the current COVID-19 pandemic, this model can help

review. Disasters. 2016;40(1):158-182. doi: 10.1111/disa.12135

improve communication, resource use, staff and patient safety, 7. Bryant JL, Sosin DM, Wiedrich TW, et al. Emergency Operations Centers

and maintenance of roles. We offer this model as one that can and Incident Management Structure. Centers for Disease Control and

be generalizable to other sites and events but emphasize the Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/eis/field-epi-manual/chapters/EOC-

need for adaptability to customize to the unique needs of both Incident-Management.html. Published September 25, 2019. Accessed

March 30, 2020.

the hospital and the incident.

8. Tsai M-C, Arnold JL, Chuang C-C, et al. Implementation of the Hospital

Emergency Incident Command System during an outbreak of severe acute

About the Authors respiratory syndrome (SARS) at a hospital in Taiwan, ROC. J Emerg Med.

2005;28(2):185-196. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2004.04.021

McGaw Medical Center of Northwestern University, Chicago, Illinois (Drs Farcas, 9. Cruz MA, Hawk NM, Poulet C, et al. Public health incident management:

Ko); Northwestern Medicine Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago, Illinois logistical and operational aspects of the 2009 initial outbreak of H1N1

(Drs Chan, Malik, Chiampas) and Northwestern Medicine, Chicago, Illinois influenza in Mexico. J Emerg Manag. 2015;13(1):71-77. doi: 10.5055/

(Ms Nono). jem.2015.0219

10. Department of Homeland Security. National Incident Management System.

Correspondence and reprint requests to Andra Farcas, 211 E Ontario Street, Suite https://www.fema.gov/media-library-data/1508151197225-ced8c60378c3936

200, Chicago IL 60611 (e-mail: andra.farcas@northwestern.edu). adb92c1a3ee6f6564/FINAL_NIMS_2017.pdf. Accessed March 28, 2020.

11. Federal Emergency Management Agency. Glossary. FEMA.gov. https://

Acknowledgments emilms.fema.gov/IS331-REP/lesson9/glossary.htm. Accessed April 7,

The authors acknowledge the contributions of the Emergency Department 2020.

Leadership Team at Northwestern Memorial Hospital and Katherine Bruni 12. Council National Research. Facing Hazards and Disasters: Understanding

from Northwestern Medicine. Human Dimensions. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press;

2006. doi: 10.17226/11671

13. Homeland Security Presidential Directive 5. Department of Homeland

REFERENCES Security. https://www.dhs.gov/publication/homeland-security-presidential-

directive-5. Published November 27, 2013. Accessed April 3, 2020.

1. Smith W, Dowell J. A case study of co-ordinative decision-making in 14. Papagiotas SS, Frank M, Bruce S, et al. From SARS to 2009 H1N1

disaster management. Ergonomics. 2000;43(8):1153-1166. doi: 10.1080/ influenza: the evolution of a public health incident management sys-

00140130050084923 tem at CDC. Public Health Rep. 2012;127(3):267-274. doi: 10.1177/

2. McCarthy DM, Chiampas GT, Malik S, et al. Enhancing community 003335491212700306

disaster resilience through mass sporting events. Disaster Med Public 15. Stout RJ, Cannon-Bowers JA, Salas E, et al. Planning, shared mental mod-

Health Prep. 2011;5(4):310-315. doi: 10.1001/dmp.2011.46 els, and coordinated performance: An empirical link is established. Hum

3. Federal Emergency Management Agency. Incident command system Factors. 1999;41(1):61-71. doi: 10.1518/001872099779577273

resources. FEMA.gov. https://www.fema.gov/incident-command-system- 16. Chiampas GT, Goyal AV. Innovative operations measures and nutritional

resources. Accessed April 9, 2020. support for mass endurance events. Sports Med. 2015;45(1):61-69. doi: 10.

4. Brevard SB, Weintraub SL, Aiken JB, et al. Analysis of disaster response 1007/s40279-015-0396-6

plans and the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina: lessons learned from a level I 17. Martin IB. President Statement. Society for Academic Emergency

trauma center. J Trauma. 2008;65(5):1126-1132. doi: 10.1097/TA. Medicine. https://saem.org/annual-meeting/saem20/coronavirus-(covid-19)/

0b013e318188d6e5 president-statement. Accessed April 10, 2020.

6 Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 165.215.209.15, on 01 Dec 2020 at 04:27:05, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at

https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/dmp.2020.210

© 2020. This work is licensed under

https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/(the “License”).

Notwithstanding the ProQuest Terms and Conditions, you may use this

content in accordance with the terms of the License.

You might also like

- The Evolution of Public Health Emergency Ajph.2017.303947Document8 pagesThe Evolution of Public Health Emergency Ajph.2017.303947Jack Yu-Tung ChangNo ratings yet

- I Used To Be A Desgin StudentDocument256 pagesI Used To Be A Desgin StudentMLNo ratings yet

- Challenges of Public Schools With Incident Command Systems For Disaster Risk Reduction ManagementDocument7 pagesChallenges of Public Schools With Incident Command Systems For Disaster Risk Reduction ManagementPsychology and Education: A Multidisciplinary JournalNo ratings yet

- Public Health Preparedness - A Systems - Level ApproachDocument5 pagesPublic Health Preparedness - A Systems - Level ApproachViorentina YofianiNo ratings yet

- ContentDocument1 pageContentRohanisa AdapNo ratings yet

- Review of The Requirements For Effective Mass Casualty Preparedness For Trauma Systems. A Disaster Waiting To Happen?Document10 pagesReview of The Requirements For Effective Mass Casualty Preparedness For Trauma Systems. A Disaster Waiting To Happen?Anthony Mero RezabalaNo ratings yet

- Responding To COVID 19 Healthcare Surge Capacity Design For High Consequence Infectious DiseaseDocument6 pagesResponding To COVID 19 Healthcare Surge Capacity Design For High Consequence Infectious DiseaseArdaNo ratings yet

- Diaster Chapter 16Document79 pagesDiaster Chapter 16Vinod ChaudhariNo ratings yet

- Shock Leadership - Pandemic ManagementDocument24 pagesShock Leadership - Pandemic Managementodin1710No ratings yet

- Hospital Disaster Plan PBL 1bDocument6 pagesHospital Disaster Plan PBL 1bTsalitsa azNo ratings yet

- Changseng2013 Tsunami Resilience Multi-Level Institution Arrangements Architectures and System of Governance For Disaster RiskDocument14 pagesChangseng2013 Tsunami Resilience Multi-Level Institution Arrangements Architectures and System of Governance For Disaster RiskAde ratihNo ratings yet

- Disaster Crisis Communication Preparedness For Healthcare: Robert C. Chandler, PH.DDocument10 pagesDisaster Crisis Communication Preparedness For Healthcare: Robert C. Chandler, PH.Dczhong16No ratings yet

- Healthcare Facility Preparedness in DisasterDocument16 pagesHealthcare Facility Preparedness in DisasterydtrgnNo ratings yet

- Baker, D. and Refsgaard, K. (2007) Institutional Development and Scale Matching in Disaster Response Management. Ecological Economics 63 PDFDocument13 pagesBaker, D. and Refsgaard, K. (2007) Institutional Development and Scale Matching in Disaster Response Management. Ecological Economics 63 PDFmichael17ph2003No ratings yet

- Community Support To Public Safety and Law Enforcement: Operation Shadow BowlDocument21 pagesCommunity Support To Public Safety and Law Enforcement: Operation Shadow BowlcpbauschNo ratings yet

- National Response FrameworkDocument57 pagesNational Response FrameworkAvishek NepbloodNo ratings yet

- Final Technology 001Document9 pagesFinal Technology 001kebNo ratings yet

- Kanlaon: Disaster Management Information SystemDocument9 pagesKanlaon: Disaster Management Information SystemMarcAguilar100% (1)

- COVID ECMO Resource PlanningDocument5 pagesCOVID ECMO Resource PlanningTing Churn WongNo ratings yet

- 121 Richmond Street W Suite 700 Toronto, On M5H 2K1 T: 4 1 6 - 6 4 2 - 1 2 7 8 F: 4 1 6 - 8 4 7 - 0 0 3 7Document9 pages121 Richmond Street W Suite 700 Toronto, On M5H 2K1 T: 4 1 6 - 6 4 2 - 1 2 7 8 F: 4 1 6 - 8 4 7 - 0 0 3 7hemangpalwalaNo ratings yet

- Outsourcing Incident-Response Communications: A Managed Services ApproachDocument5 pagesOutsourcing Incident-Response Communications: A Managed Services ApproachnharveyNo ratings yet

- Jama Barbash 2021 VP 210091 1629733292.12718Document2 pagesJama Barbash 2021 VP 210091 1629733292.12718ArdaNo ratings yet

- EOC Situational Awareness EssentialsDocument31 pagesEOC Situational Awareness EssentialsKeyvoh KeymanNo ratings yet

- Shared Governance During A PandemicDocument3 pagesShared Governance During A PandemicNurulfitrahhafidNo ratings yet

- Mass Casualty Incident Management - PMCDocument10 pagesMass Casualty Incident Management - PMCLolaNo ratings yet

- Leadership During The COVID-19 Pandemic: Building and Sustaining Trust in Times of UncertaintyDocument4 pagesLeadership During The COVID-19 Pandemic: Building and Sustaining Trust in Times of Uncertainty06Annisa SyifaNo ratings yet

- Incident Command SystemDocument4 pagesIncident Command Systemtdywaweru5No ratings yet

- Meta-Leadership and National Emergency Preparedness: A Model To Build Government ConnectivityDocument7 pagesMeta-Leadership and National Emergency Preparedness: A Model To Build Government ConnectivityFirah MagfirahNo ratings yet

- 2021 The Resilience of Critical Infrastructure Systems - A Systematic Literature ReviewDocument33 pages2021 The Resilience of Critical Infrastructure Systems - A Systematic Literature ReviewkevinNo ratings yet

- DM Act in COVID-19Document1 pageDM Act in COVID-19Anushka GuptaNo ratings yet

- ReviewDocument34 pagesReviewMoises Apolonio100% (1)

- Scenario Planning in Disaster Management A Call To Change The Current PracticeDocument3 pagesScenario Planning in Disaster Management A Call To Change The Current Practiceeditorial.boardNo ratings yet

- International Journal of Information Management: Opinion PaperDocument7 pagesInternational Journal of Information Management: Opinion PaperNanoNo ratings yet

- Healthcare Facilities Incident CommandDocument18 pagesHealthcare Facilities Incident CommandydtrgnNo ratings yet

- Advisory Memorandum On Ensuring Essential Critical Infrastructure Workers' Ability To Work During The Covid-19 ResponseDocument23 pagesAdvisory Memorandum On Ensuring Essential Critical Infrastructure Workers' Ability To Work During The Covid-19 ResponseGisele ChagasNo ratings yet

- Advisory Memorandum On Ensuring Essential Critical Infrastructure Workers' Ability To Work During The Covid-19 ResponseDocument23 pagesAdvisory Memorandum On Ensuring Essential Critical Infrastructure Workers' Ability To Work During The Covid-19 ResponseGisele ChagasNo ratings yet

- Pi Is 0140673620307297Document2 pagesPi Is 0140673620307297Koushik MajumderNo ratings yet

- The Role of Emergency Nurses in Emergency Preparedness and ResponseDocument7 pagesThe Role of Emergency Nurses in Emergency Preparedness and ResponseEnis SpahiuNo ratings yet

- COVID-19 The Showdown For Mass Casualty Preparedness and Management: The Cassandra SyndromeDocument6 pagesCOVID-19 The Showdown For Mass Casualty Preparedness and Management: The Cassandra SyndromejesaloftNo ratings yet

- Case Study Chapter 2020405Document62 pagesCase Study Chapter 2020405Dang Hoang QuanNo ratings yet

- Assignment 1 - CrisisDocument14 pagesAssignment 1 - CrisisRosebell K MathewNo ratings yet

- WHO WHE SPP 2023.1 EngDocument20 pagesWHO WHE SPP 2023.1 Engpenelitian.shellyNo ratings yet

- Critical Care and Disaster Management: Margaret M. Parker, MD, FCCMDocument4 pagesCritical Care and Disaster Management: Margaret M. Parker, MD, FCCMSid DhayriNo ratings yet

- Integrating Disaster Preparedness Into A Community Health Nursing Course: One School's ExperienceDocument5 pagesIntegrating Disaster Preparedness Into A Community Health Nursing Course: One School's ExperienceEviNo ratings yet

- Crit Care DisasterDocument7 pagesCrit Care DisasterArif_ProbliNo ratings yet

- Voorbeeldpaper BigleyDocument20 pagesVoorbeeldpaper BigleyIssamHirchiNo ratings yet

- Business Continuity Plan Specific Issues For Public Health EmergenciesDocument9 pagesBusiness Continuity Plan Specific Issues For Public Health EmergenciesaeroipnNo ratings yet

- DRM Policy & StrategyDocument36 pagesDRM Policy & StrategyMarkan GetnetNo ratings yet

- 2disaster Nursing SAS Session 2Document7 pages2disaster Nursing SAS Session 2Beverly Mae Castillo JaymeNo ratings yet

- EWS Task 1@gatluak+++Document11 pagesEWS Task 1@gatluak+++Gatluak Ngueny TotNo ratings yet

- OutlineDocument2 pagesOutlineLea CaringalNo ratings yet

- Reneslacis Anne - Honors ProjectDocument33 pagesReneslacis Anne - Honors ProjectLigia-Elena StroeNo ratings yet

- NURS FPX 6618 Assessment 3 Disaster Plan With Guidelines For ImplementationDocument4 pagesNURS FPX 6618 Assessment 3 Disaster Plan With Guidelines For ImplementationEmma WatsonNo ratings yet

- DisasterNursing SemifinalsDocument2 pagesDisasterNursing SemifinalsKATHLEEN JOSOLNo ratings yet

- Telemedicine in The Era of The COVID-19 Pandemic: Implications in Facial Plastic SurgeryDocument3 pagesTelemedicine in The Era of The COVID-19 Pandemic: Implications in Facial Plastic Surgerytresy kalawaNo ratings yet

- Response: Managing Emergencies and Disasters: OutcomesDocument57 pagesResponse: Managing Emergencies and Disasters: OutcomesprabodhNo ratings yet

- S1049023X19005181 2Document8 pagesS1049023X19005181 2Dr. Sahrish SabaNo ratings yet

- Disaster 1 1Document9 pagesDisaster 1 1Anonymous MeFXTEXOhNo ratings yet

- Disaster Risk Communication: A Challenge from a Social Psychological PerspectiveFrom EverandDisaster Risk Communication: A Challenge from a Social Psychological PerspectiveKatsuya YamoriNo ratings yet

- Policy Note - Understanding Risk in an Evolving WorldFrom EverandPolicy Note - Understanding Risk in an Evolving WorldNo ratings yet

- Crisis Management: Strategies for Mitigating and Recovering from DisastersFrom EverandCrisis Management: Strategies for Mitigating and Recovering from DisastersNo ratings yet

- SQL 2Document7 pagesSQL 2Mahendra UgaleNo ratings yet

- Listing of SecuritiesDocument5 pagesListing of SecuritiesticktacktoeNo ratings yet

- Consumer Decision MakingDocument8 pagesConsumer Decision Making9986212378No ratings yet

- One2One Panama 2015Document6 pagesOne2One Panama 2015Dhaval ShahNo ratings yet

- Milk TesterDocument9 pagesMilk TesterUjval ParghiNo ratings yet

- VP422 HDTV10A Service Manual PDFDocument25 pagesVP422 HDTV10A Service Manual PDFDan Prewitt0% (1)

- Designing Data Analysis ProcedureDocument15 pagesDesigning Data Analysis ProcedureShadowStorm X3GNo ratings yet

- Hills Cement FinalDocument204 pagesHills Cement FinalAniruddha DasNo ratings yet

- FABM 2 Module 6 Cash Bank ReconDocument6 pagesFABM 2 Module 6 Cash Bank ReconJOHN PAUL LAGAO40% (5)

- Easy Soft Education Loans For SRM StudentsDocument13 pagesEasy Soft Education Loans For SRM StudentsSankarNo ratings yet

- Soal Bahasa Inggris Semerter VI (Genap) 2020Document5 pagesSoal Bahasa Inggris Semerter VI (Genap) 2020FabiolaIvonyNo ratings yet

- Oracle Database Appliance Bare Metal Restore StepsDocument7 pagesOracle Database Appliance Bare Metal Restore StepsKarthika TatiparthiNo ratings yet

- Regional Memorandum: Adjusted Search Timeline Activity Date RemarksDocument2 pagesRegional Memorandum: Adjusted Search Timeline Activity Date RemarksKimttrix WeizsNo ratings yet

- Følstad & Brandtzaeg (2020)Document14 pagesFølstad & Brandtzaeg (2020)Ijlal Shidqi Al KindiNo ratings yet

- BBA 420 Lecture 2: Individual Differences and Work AttitudesDocument14 pagesBBA 420 Lecture 2: Individual Differences and Work AttitudesTh'bo Muzorewa ChizyukaNo ratings yet

- Javascript For Abap Programmers: Chapter 3.5 - ArraysDocument26 pagesJavascript For Abap Programmers: Chapter 3.5 - ArraysvenubhaskarNo ratings yet

- DeloitteConsulting - Nancy Singhal ResumeDocument4 pagesDeloitteConsulting - Nancy Singhal ResumeHemant BharadwajNo ratings yet

- SupplyPower Overview Presentation SuppliersDocument20 pagesSupplyPower Overview Presentation SuppliersCarlos CarranzaNo ratings yet

- Multistage Flowsheets - SABC-2Document191 pagesMultistage Flowsheets - SABC-2lewis poma rojasNo ratings yet

- BSP M-2022-024 s2022 - Rural Bank Strengthening Program) PDFDocument5 pagesBSP M-2022-024 s2022 - Rural Bank Strengthening Program) PDFVictor GalangNo ratings yet

- James Hardie Eaves and Soffits Installation ManualDocument32 pagesJames Hardie Eaves and Soffits Installation ManualBoraNo ratings yet

- AgrrrraaDocument31 pagesAgrrrraaAnonymous apYVFHnCYNo ratings yet

- Maximum Equivalent Stress Safety ToolDocument2 pagesMaximum Equivalent Stress Safety ToolDonfack BertrandNo ratings yet

- Stacie Adams: Professional Skills ProfileDocument1 pageStacie Adams: Professional Skills Profileapi-253574880No ratings yet

- Bakri Balloon PDFDocument5 pagesBakri Balloon PDFNoraNo ratings yet

- A. Introduction: Module Gil BasicsDocument12 pagesA. Introduction: Module Gil BasicsMayuresh JoshiNo ratings yet

- Bou CatddDocument2 pagesBou CatddDJNo ratings yet

- Struts 2 InterceptorsDocument14 pagesStruts 2 InterceptorsRamasamy GoNo ratings yet

- Public Private Partnership in Public Administration Discipline A Literature ReviewDocument25 pagesPublic Private Partnership in Public Administration Discipline A Literature ReviewJuan GalarzaNo ratings yet