Professional Documents

Culture Documents

How To Recognise and Treat Peripheral Nervous System Vasculitis.

Uploaded by

zaquvubeOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

How To Recognise and Treat Peripheral Nervous System Vasculitis.

Uploaded by

zaquvubeCopyright:

Available Formats

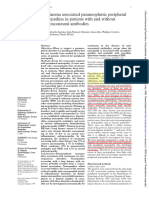

THERAPEUTIC INTERVENTIONS

How to recognise and treat

peripheral nervous system vasculitis

E A Marsh,1,2 L M Davies,3 J G Llewelyn1,2

ABSTRACT

1

Department of Neurology, Royal can be as a series of complete mono-

Gwent Hospital, Newport, UK Peripheral neuropathy can be the first and only neuropathies presenting acutely over a

2

Department of Neurology,

University Hospital of Wales, manifestation of necrotising primary immune- few days, or with slow accumulation of

Cardiff, UK mediated vasculitis which, carries a high asymmetric multifocal neurological defi-

3

Department of Pharmacy, mortality. A clear idea of how to both recognise cits, sometimes punctuated by acute

University Hospital of Wales,

Cardiff, UK

and treat peripheral nervous system vasculitis is events. Occasionally the progression of

important. We provide a practical approach to mononeuropathies can be so rapid that

Correspondence to immediate and longer term treatment protocols. the presenting picture can be mistaken

Dr E A Marsh, Department of for that of a symmetric polyneuropathy.

Neurology, Royal Gwent

Hospital, Newport, NP20 2UB, INTRODUCTION PNS vasculitis can also present with an

UK; In a third of patients, neuropathy is isolated mononeuropathy, a chronic distal

eleanor.marsh@wales.nhs.uk

the initial manifestation of necrotising symmetric sensorimotor axonal polyneur-

primary immune-mediated vasculitis.1 opathy or a radiculoplexus neuropathy.

Published Online First

10 May 2013 The range of classification systems is con- The range of potential causes is large

fusing: some considering the size of the (table 1).

affected blood vessel,2 3 others referring

to types of organ involvement and auto- PNS VASCULITIS: IS IT PART OF A

antibody profiles. From the neurologists’ SYSTEMIC OR LOCALISED PROCESS?

point of view, what is useful to know is While multi-organ involvement in

whether peripheral nervous system (PNS) primary immune-mediated vasculitides is

vasculitis is likely to be part of a systemic the rule, the ANCA associated conditions

process or whether it is non-systemic and have predominant ‘kidney–chest’ involve-

localised. Another useful division con- ment, and immune complex types have a

cerns the underlying immune process: ‘kidney–skin’ involvement. Microscopic

whether it is antineutrophil cytoplasmic polyangiitis, a subtype of polyarteritis

antibody (ANCA) associated or immune nodosa, is highly likely to affect the PNS,

complex driven. This will help the clin- a neuropathy being seen in up to 50% of

ician to make an unifying diagnosis, all cases within a few months of diagno-

allowing appropriate investigation and sis.8 In Wegener’s granulomatosis and

relevant involvement of other specialists, Churg–Strauss syndrome, PNS involve-

usually rheumatologists or renal physi- ment occurs as a secondary phenomenon,

cians. Before the introduction of steroids the primary stage typically involving

and cyclophosphamide (CYC) in the chest and upper airways.

early 1970s, survival rates from primary There is also PNS-specific vasculitis.

immune-mediated vasculitis were low. Long term follow-up studies have shown

Induction of remission is now achieved in that this remains localised to the PNS9

over 90% of patients by 6 months,4 and and despite the occasional presence of

5-year survival rates are around 75%.5 systemic markers (raised CRP, etc), carries

However, even with best available no risk of multi-organ failure.

therapy, relapse rates remain high at up

to 50% over 5 years,6 as does treatment HOW TO DIAGNOSE AND WHEN

related morbidity and mortality. TO TREAT PNS VASCULITIS

Histological evidence remains the ‘gold-

HOW TO IDENTIFY PNS VASCULITIS standard’ for the diagnosis of PNS vascu-

To cite: Marsh EA, CLINICALLY litis. Of patients ultimately diagnosed

Davies LM, Llewelyn JG. Pract Multiple mononeuropathy is the mode of with vasculitic neuropathy, sural nerve

Neurol 2013;13:408–411. presentation in up to 30% of cases.7 This biopsy alone is confirmatory in 40%–50%

408 Marsh EA, et al. Pract Neurol 2013;13:408–411. doi:10.1136/practneurol-2012-000464

THERAPEUTIC INTERVENTIONS

Table 1 Causes of peripheral nervous system (PNS) vasculitis

A primary immune-mediated vasculitic ANCA associated Wegener’s granulomatosis, Churg–Strauss syndrome, polyarteritis nodosa and

process microscopic polyangiitis

Immune complex Henoch-Schönlein purpura and essential cryoglobulinaemic vasculitis

driven

A vasculitic process resulting from other types Rheumatoid arthritis, systemic sclerosis, Sjögren’s syndrome, essential

of autoimmune conditions cryoglobulinaemia

A vasculitic process resulting from other Diabetes Diabetic radiculoplexus neuropathy

non-autoimmune conditions Drugs Amphetamine, propylthiouracil, hydralazine, interferons, non-steroidal

anti-inflammatory drugs, penicillin, allopurinol, cocaine, heroin, sulfonamides and

phenytoin

Viral infections Cytomegalovirus, human T-lymphotropic virus 1, hepatitis, human immunodeficiency

virus, Herpes simplex virus, Varicella zoster virus, Epstein-Barr virus, cytomegalovirus

Bacterial infections Infective endocarditis, Strep pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, Salmonella typhi,

alpha haemolytic strep, Lyme, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, leprosy, Treponema

pallidum

Fungal infections Aspergillus, coccidoides, mucormycosis, histoplasma capsulatum

Protozoa infections Toxoplasma gondii, Plasmodium falciparum

Radiation

Paraneoplastic

Malignancy

Chronic Sarcoidosis

inflammatory

ANCA, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody.

of cases. A combined nerve–muscle biopsy gives a posi- we feel the presence of poor prognostic indicators

tive result in 60%–70% of cases.10 Biopsy should only would justify intravenous steroids early in this initial

be considered if the possibility of vasculitis is high and phase.

the blood tests are uninformative. Delay in starting The CYCLOPS trial showed that a single pulse of

treatment should be avoided. intravenous CYC 15 mg/kg (max dose 1.2 g) repeated

every 2 weeks for the first three pulses, then at

HOW TO TREAT PNS VASCULITIS 3 weekly intervals until remission and then for

The treatment of vasculitis depends on its cause. The another 3 months was equal to oral CYC at its normal

use of CYC and other immunosuppressive agents has dosing regimen (2 mg/kg/day for 3 months and then

transformed the prognosis of the primary immune- 1.5 mg/kg/day for another 3 months, with dose adjust-

mediated vasculitides. There is no available evidence ment for age) in providing remission-induction, but

from randomised controlled studies to support the use with fewer side effects.11 Patients should be moni-

of CYC in isolated PNS vasculitis. There are two main tored clinically every 8 weeks during this initial remis-

phases in the treatment of PNS vasculitis.11 sion period. The dose of intravenous CYC should be

▸ Remission-induction therapy: An initial treatment that adjusted according to age and renal function, as

results in resolution of the manifestations of active shown in table 2. Usually in clinical practice, we find

vasculitis. 6–10 pulses are required over a period of 3–6 months.

▸ Remission-maintenance therapy: A continuation of treat- One of the main limitations of CYC is its ability to

ment for a prolonged period with the aim of maintaining reduce the white cell count (WCC). Therefore, subse-

control and reducing the likelihood of clinical relapses. quent pulses should be adjusted (in addition to renal

function) according to the lowest WCC, referred to as

nadir, typically seen 10–14 days after the pulse, as

REMISSION-INDUCTION THERAPY

shown in box 1. This dose adjustment aims to main-

Glucocorticoids and CYC form the basis of initial

tain the total WCC in a safe range so as to minimise

treatment. Oral prednisolone is prescribed at 1 mg/kg/

the risk of infection.

day from onset of treatment. When rapid effect is

needed, intravenous methylprednisolone 1g/day for

the first 3 days, then oral prednisolone at 1 mg/kg/day Table 2 Dose adjustment of intravenous cyclophosphamide

can be used.12 Markers of poor prognosis in vasculitis (IV CYC) according to age and renal function11

include advanced renal impairment at presentation

Creatine mmol/l

and the presence of c-ANCA with anti-proteinase 3

(which is highly suggestive of Wegener’s granulomato- Age <300 300–500 >500

sis) rather than p-ANCA with anti-myeloperoxidase

<60 15 mg/kg/pulse 12.5 mg/kg/pulse Consider alternative

(more commonly seen in microscopic polyangiitis and to IV CYC

60–70 12.5 mg/kg/pulse 10 mg/kg/pulse

Churg–Strauss syndrome).12 While there is no clear

>70 10 mg/kg/pulse 7.5 mg/kg/pulse

guidance to advise us on the intensity of steroid use

Marsh EA, et al. Pract Neurol 2013;13:408–411. doi:10.1136/practneurol-2012-000464 409

THERAPEUTIC INTERVENTIONS

for early non-life threatening disease without signifi-

Box 1 Adjustment of intravenous cyclophospha- cant renal disease. However, it has been seen to result

mide (IV CYC) doses according to white cell count in more relapses at 18 months and an increased risk

(WCC) nadir13 of progression to more widespread disease than with

CYC.14 MTX is prescribed orally at 10 mg once a

▸ WCC: 1–2×109/L reduce IV CYC for next dose by 40% week, gradually increasing to 20–25 mg once a week

▸ WCC: 2–3×109/L reduce IV CYC for next dose by 20% over 1–2 months if tolerated. Folic acid (5 mg once a

▸ WCC: >3×109/L keep IV CYC dose the same week) should be prescribed to be taken 1–2 days after

MTX to minimise some side effects. A baseline chest

x-ray is usually carried out and routine blood moni-

In addition, the pulse of intravenous CYC is only toring for full blood count, liver and renal function is

given if the WCC on the day of the pulse is >4 × 109/l also required throughout treatment. We feel this

and neutrophils >2 × 109/l. If this is not the case, the represents a good option for treatment in patients

pulse is postponed until the WCC is in range, normally with isolated non-systemic PNS vasculitis without

rechecking full blood count on a weekly basis. renal impairment.

Mesna (2-mercaptoethanesulfonate sodium) is admi-

nistered intravenously immediately before the intra-

venous CYC infusion. Two further oral doses are REMISSION-MAINTENANCE THERAPY

given at 2 and 6 h after the start of the infusion to This second phase of treatment is achieved with a

reduce the urotoxic side effects of a metabolite of combination of oral prednisolone and a steroid-

CYC.13 Prehydration with a litre of normal saline is sparing agent. Azathioprine (AZA) at 2 mg/kg/day has

usually given before the CYC pulse. Urinalysis is rou- been shown to be as effective as oral CYC (1.5 mg/kg/

tinely carried out prior to each dose to monitor for day) in preventing relapse at 18 months, but with a

bladder toxicity. Patients are given antiemetic medica- lower risk of serious adverse effects (10% vs 18%).15

tion on a ‘when required’ basis for the initial 48 h. AZA is started at a low dose, for example, 25 mg

Pneumocystis jiroveci infection can be a complication daily and increased gradually over a few weeks to

in immunocompromised patients. In patients receiving target dose provided pretreatment thiopurine methyl-

CYC and glucocorticoids there is some evidence to transferase levels are normal. We take a pragmatic

support the use of prophylactic co-trimoxazole view that remission-maintenance therapy (with AZA,

960 mg given orally three times a week.13 CYC or MTX) should be continued for 24 months,

It has been recommended that patients with severe/ although evidence for this duration of treatment only

life threatening vasculitis and significant renal failure exists for ANCA positive vasculitis.12

(creatine >500 mmol/l) should be treated with plasma Oral prednisolone should be started at a dose of

exchange in addition to the standard treatment regi- 1 mg/kg/day—see Remission-induction therapy section

mens (with oral prednisolone and intravenous CYC).13 above. The dose is then gradually tapered; however,

Oral methotrexate (MTX) has been shown to have the dose should not go below 15 mg/ day for the first

similar success rates to CYC for remission-induction 3 months. When a dose of 15 mg/day is reached,

Table 3 Oral prednisolone calculator chart: adapted from CYCLOPS trial protocol16

Time from entry Prednisolone dosage Prednisolone dosage

(weeks) (mg/kg/day) Prednisolone dosage (mg/day for 60 kg) (mg/kg for 90 kg)

0 1 60 80

1 0.75 45 70

2 0.5 30 45

3 0.4 25 35

6 0.33 20 30

8 0.25 15 20

Maximum 80 mg a day

Round dose to nearest 5 mg above 20 mg

Prednisolone dosage Round dose to nearest 2.5 mg below 20 mg

(mg/day)

At end of month 3 12.5

At month 6 10

During months 12–15 7.5

During months 15–18 5

410 Marsh EA, et al. Pract Neurol 2013;13:408–411. doi:10.1136/practneurol-2012-000464

THERAPEUTIC INTERVENTIONS

the steroid taper is continued at a slower rate (see REFERENCES

table 3). With prolonged use of steroids, it is our 1 Said G, Lacroix C, Lozeron P, et al. Inflammatory vasculopathy

routine practice to provide adequate bone (bispho- in multifocal diabetic neuropathy. Brain 2003;126:376–85.

sphonate, calcium, vitamin D) and gastrointestinal 2 Hunder GG, Arend WP, Bloch DA, et al. The American

College of Rheumatology 1990 criteria for the classification of

( proton pump inhibitor) protection.

vasculitis. Arthritis Rheum 1990:33,1065–67.

Oral MTX continuing at 20–25 mg/week as an

3 Jeanette JC, Faulk RJ, Andrassy K, et al. Nomenclature of

alternative to AZA can be used if it had been started systemic vasculitides. Proposal of an international consensus

in the remission-induction phase.17 conference. Arthritis Rheum 1994;37:187–92.

4 Jayne D, Rasmussen N, Andrassy K, et al. A randomized trial

of maintenance therapy for vasculitis associated with

antineutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibodies. N Engl J Med

2003;349:36–40.

WHAT TO TELL PATIENTS ABOUT TREATMENT 5 Matteson EL, Gold KN, Bloch DA, et al. Long-term survival of

Once the diagnosis of PNS vasculitis has been dis- patients with Wegener’s granulomatosis from the American

cussed, the patient must be informed before treatment College of Rheumatology Wegener’s Granulomatosis

of the side effects of steroids and advised to carry a Classification Criteria Cohort. Am J Med 1996;101:129–34.

steroid treatment card at all times. 6 Westman KW, Bygren PG, Olsson H, et al. Relapse rate, renal

CYC, MTX and AZA are immunosuppressant medi- survival, and cancer morbidity in patients with Wegener’s

cines with a major risk of bone marrow suppression granulomatosis or microscopic polyangiitis with renal

and associated infection. Liver toxicity is a possible involvement. J Am Soc Nephrol 1998;9:842–52.

7 Zivkovic SA, Ascgerman D, Lacomis D. Vasculitic neuropathy

adverse effect of MTX and AZA therapy. Patients

—electrodiagnostic findings and association with malignancies.

must be made aware that blood test monitoring (full

Acta Neurol Scand 2007;115:432–36.

blood count, liver function and renal function as 8 Schaublin GA, Michet CJ Jr, Dyck PJ, et al. An update on the

appropriate) is required regularly throughout treat- classification and treatment of vasculitic neuropathy. Lancet

ment to ensure safety. This is usually started in Neurol 2005;4:853–65.

hospital and once stable the responsibility is trans- 9 Dyck PJ, Benstead TJ, Conn DL, et al. Nonsystemic vasculitic

ferred to the GP using agreed local shared care proto- neuropathy. Brain 1987;110:843–53.

cols. We encourage patients to keep their own record 10 Collins MP, Mendell JR, Periquet MI, et al. Superficial

of blood results. Patients should be advised on how to peroneal nerve/ peroneous brevis muscle biopsy in vasculitic

recognise and act on any symptoms that may suggest neuropathy. Neurology 2000;55:636–43.

infection, thrombocytopenia, liver toxicity, MTX- 11 De Groot K, Harper L, Jayne DRW, et al. EUVAS (European

induced pneumonitis or CYC-induced urotoxicity. Vasculitis Study Group). CYCLOPS trial. Pulse versus daily oral

cyclophosphamide for induction of remission in

Other potential adverse effects associated with these

antineurtrophil cyctoplasmic antibody-associated vasculitis: a

medicines include nausea, rash, secondary malignancy, randomised trial. Ann Intern Med 2009;150:670–80.

teratogenicity and hair loss. CYC treatment is asso- 12 Hamour S, Salama AD, Pusey CD. Management of

ciated with infertility and the possibility of egg/sperm ANCA-associated vasculitis: current trends and future

harvesting should be discussed with appropriate prospects. Ther Clin Risk Manag 2010;6:253–64.

patients. It is recommended that patients receiving 13 Lapraik C, Watts R, Bacon P, et al. BSR and BHPR guidelines

immunosuppressants should receive pneumococcal for the management of adults with ANCA associated vasculitis.

and influenza vaccination. Live vaccines should gener- Rheumatology 2007;46:1–11.

ally be avoided due to reduced response and risk of 14 De Groot K, Rasmussen N, Bacon P, et al. Randomisation trial

infection. Patient collaboration through being thor- of cyclophosphamide versus methotrexate for induction of

remission in early systemic antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody

oughly informed and motivated is critical to minimis-

associated vasculitis. Arthritis Rheum 2005;52:2462–8.

ing clinical risk and optimising treatment outcome.

15 Mukhtyar C, Guillevin L, Cid MC, et al. EULAR

recommendations for the management of primary small and

Contributors JGL had a role in planning the project and editing medium vessel vasculitis. Ann Rheum Dis 2009;68:310–17.

the manuscript for presentation. LMD had a role in

16 De Groot K, Harper L, Jayne DRW, et al. EUVAS (European

pharmacotherapy-related contents and recommendations for

minor editing (typographical/grammatical). EAM takes Vasculitis Study Group). CYCLOPS trial protocol. http://www.

responsibility for the planning and overall content. vasculitis.nl/media/documents/cyclops.pdf

Competing interests None. 17 Reinhold-Keller E, Fink CO, Herlyn K, et al. High rate of

renal relapse in 71 patients with Wegener’s granulomatosis

Provenance and peer review Not commissioned; externally

peer reviewed. This paper was reviewed by Neil Scolding, under maintenance of remission with low-dose methotrexate.

Bristol, UK. Arthritis Rheum 2002;47:326–32.

Marsh EA, et al. Pract Neurol 2013;13:408–411. doi:10.1136/practneurol-2012-000464 411

You might also like

- COVID Report NegativeDocument1 pageCOVID Report NegativeahmedNo ratings yet

- LOG BOOK For Objective Assessment C-P I & II KMUDocument13 pagesLOG BOOK For Objective Assessment C-P I & II KMUFarhaanKhanHaleem100% (3)

- Pharmaceutics-III For Pharmacy Technician 2nd Year BookDocument30 pagesPharmaceutics-III For Pharmacy Technician 2nd Year BookAttari Express YT88% (8)

- JHA Risk Assesment 1Document6 pagesJHA Risk Assesment 1leonardo GaraisNo ratings yet

- A Clinician's Approach To Peripheral NeuropathyDocument12 pagesA Clinician's Approach To Peripheral Neuropathytsyrahmani100% (1)

- Vasculitic NeuropathiesDocument20 pagesVasculitic NeuropathiesHITIPHYSIONo ratings yet

- Anaesthesia Revised A5Document720 pagesAnaesthesia Revised A5barn003100% (1)

- PARANEOPLASTICDocument8 pagesPARANEOPLASTICMuhammad Imran MirzaNo ratings yet

- 2007 - Deinstitutionalisation and Reinstitutionalisation - Major Changes in The Provision of Mental Heathcare Psychiatry 6, 313-316Document4 pages2007 - Deinstitutionalisation and Reinstitutionalisation - Major Changes in The Provision of Mental Heathcare Psychiatry 6, 313-316Antonio Tari100% (1)

- Autoimmune Axonal Neuropathies. 2023Document15 pagesAutoimmune Axonal Neuropathies. 2023Arbey Aponte PuertoNo ratings yet

- Acute Pain Due To Gastritis Care Plan-G.a.Document1 pageAcute Pain Due To Gastritis Care Plan-G.a.Kristin Bienvenu85% (13)

- Localization and Diagnostic Evaluation of Peripheral Nerve Disorders. 2023Document23 pagesLocalization and Diagnostic Evaluation of Peripheral Nerve Disorders. 2023Arbey Aponte PuertoNo ratings yet

- Neurological Disease VIH LibroDocument27 pagesNeurological Disease VIH LibroEdwin AlvarezNo ratings yet

- Antoine 2017Document8 pagesAntoine 2017Eliana NataliaNo ratings yet

- Membrane NephropathyDocument14 pagesMembrane NephropathyCasey GondoNo ratings yet

- Tavee2015 NeurosarcoidosisDocument14 pagesTavee2015 NeurosarcoidosisJohan ArocaNo ratings yet

- Antibody Mediated Autoimmune Encephalitis in ChildhoodDocument11 pagesAntibody Mediated Autoimmune Encephalitis in ChildhoodTessa CruzNo ratings yet

- Neuromyelitis Optica (Devic's Syndrome) : An Appraisal: Vasculitis (LR Espinoza, Section Editor)Document9 pagesNeuromyelitis Optica (Devic's Syndrome) : An Appraisal: Vasculitis (LR Espinoza, Section Editor)ezradamanikNo ratings yet

- Examination of Peripheral Nerve InjuriesDocument9 pagesExamination of Peripheral Nerve InjuriessarandashoshiNo ratings yet

- Meningitis Vs Ensefalitis MeganDocument10 pagesMeningitis Vs Ensefalitis MeganFandi ArgiansyaNo ratings yet

- Espectro Neuromielitis Óptica 2022 NejmDocument9 pagesEspectro Neuromielitis Óptica 2022 NejmOscar BushNo ratings yet

- 19 Full-1Document15 pages19 Full-1Dionisio Garcia AlvarezNo ratings yet

- Pres y SepsisDocument8 pagesPres y SepsisAlfredo Enrique Marin AliagaNo ratings yet

- Autoimmune Vestibulocerebellar SyndromesDocument19 pagesAutoimmune Vestibulocerebellar Syndromesrafael rocha novaesNo ratings yet

- Clinical evaluation and investigation of neuropathy simplifiedDocument6 pagesClinical evaluation and investigation of neuropathy simplifiedMaria RenjaanNo ratings yet

- 2020 Épileptogenèse Et Neuro InflammationDocument22 pages2020 Épileptogenèse Et Neuro InflammationFlorian LamblinNo ratings yet

- Nephrotic Syndrome: Symposium: NephrologyDocument4 pagesNephrotic Syndrome: Symposium: Nephrologypramuliansyah haqNo ratings yet

- Journal ReadingDocument15 pagesJournal ReadingUsmel RamadhaniaNo ratings yet

- Paraneoplastic SyndromesDocument8 pagesParaneoplastic SyndromesAndres F AristizabalNo ratings yet

- Multiple-System AtrophyDocument15 pagesMultiple-System AtrophyNathasia SuryawijayaNo ratings yet

- Paraneoplastic Neurologic Syndromes: Myrna R. Rosenfeld, MD, PHD A, Josep Dalmau, MD, PHD BDocument25 pagesParaneoplastic Neurologic Syndromes: Myrna R. Rosenfeld, MD, PHD A, Josep Dalmau, MD, PHD Banton MDNo ratings yet

- The Diagnosis and Treatment of Autoimmune Encephalitis JCN 2016Document13 pagesThe Diagnosis and Treatment of Autoimmune Encephalitis JCN 2016Alex Del PieroNo ratings yet

- Review Article: Acute Necrotizing Encephalopathy: An Underrecognized Clinicoradiologic DisorderDocument11 pagesReview Article: Acute Necrotizing Encephalopathy: An Underrecognized Clinicoradiologic DisorderfrizkapfNo ratings yet

- Pathogenesis of Antineutrophil Cytoplasmic Autoantibody-Mediated DiseaseDocument11 pagesPathogenesis of Antineutrophil Cytoplasmic Autoantibody-Mediated DiseasewilpmfmhNo ratings yet

- Diagnosis and Treatment of Autoimmune EncephalitisDocument26 pagesDiagnosis and Treatment of Autoimmune EncephalitisSylvia TrianaNo ratings yet

- Cidp ParaneoDocument8 pagesCidp ParaneoPablo MarinNo ratings yet

- Autoimmune EncephalitisDocument14 pagesAutoimmune EncephalitisMarco Antonio KoffNo ratings yet

- NeuromyelitisOpticaSpectrumDisorder US en ANS ORPHA71211Document8 pagesNeuromyelitisOpticaSpectrumDisorder US en ANS ORPHA71211HERIZALNo ratings yet

- Neuropatia Vasculitica - MultiplexDocument18 pagesNeuropatia Vasculitica - MultiplexJorge GámezNo ratings yet

- Nefro 341 REVIEWTreatmentoflupusnephritis OKDocument9 pagesNefro 341 REVIEWTreatmentoflupusnephritis OKSelena GajićNo ratings yet

- Neuro 1st WeekDocument70 pagesNeuro 1st WeekMel PajantoyNo ratings yet

- Diagnosis of Multiple Sclerosis Progress and ChallengesDocument11 pagesDiagnosis of Multiple Sclerosis Progress and Challengessarawu9911No ratings yet

- Paraneoplastic Neurological Review 2022Document15 pagesParaneoplastic Neurological Review 2022Med McqsNo ratings yet

- Noninfectious Cerebral Vasculitis in Children: Indianapolis, IndianaDocument15 pagesNoninfectious Cerebral Vasculitis in Children: Indianapolis, IndianaNathaly LapoNo ratings yet

- Noy 192Document10 pagesNoy 192Cleysser Antonio Custodio PolarNo ratings yet

- Nerve Conduction Studies: Australian Family Physician September 2011Document6 pagesNerve Conduction Studies: Australian Family Physician September 2011anjelikaNo ratings yet

- 412 FullDocument14 pages412 FullDennyNo ratings yet

- Role of Neuroinflammation in Neurodegeneration DevelopmentDocument32 pagesRole of Neuroinflammation in Neurodegeneration Developmentelibb346No ratings yet

- Print 2Document13 pagesPrint 2jtd9h2xp5hNo ratings yet

- Toxoplasmosis y NeosporaDocument12 pagesToxoplasmosis y NeosporaAntonio ReaNo ratings yet

- Nervous System Lupus: Pathogenesis and Rationale For TherapyDocument11 pagesNervous System Lupus: Pathogenesis and Rationale For TherapymortazaqNo ratings yet

- Síndrome PRES Inducido Por Quimioterapia e InmunosupresoresDocument8 pagesSíndrome PRES Inducido Por Quimioterapia e InmunosupresoresLaura VargasNo ratings yet

- Clinical Evaluation and Investigation of Neuropathy: Hugh J Willison, John B WinerDocument7 pagesClinical Evaluation and Investigation of Neuropathy: Hugh J Willison, John B Winerdefri rahmanNo ratings yet

- Neur CL in Pract 2013005694Document10 pagesNeur CL in Pract 2013005694Haha RowlingNo ratings yet

- JAAD - Review of Generalized and Nonlocal DysesthesiaDocument9 pagesJAAD - Review of Generalized and Nonlocal DysesthesiatzuskymedNo ratings yet

- Nej MR A 1216008Document11 pagesNej MR A 1216008guillosarahNo ratings yet

- Acquired NeuropathiesDocument106 pagesAcquired NeuropathiesDanny J. BrouillardNo ratings yet

- Vasculitic NeuropathiesDocument12 pagesVasculitic NeuropathiesAnonymous QLadTClydkNo ratings yet

- Chapter 21Document4 pagesChapter 21wazim20No ratings yet

- Encefalomielitis Diseminada AgudaDocument7 pagesEncefalomielitis Diseminada AgudasamNo ratings yet

- CE Update: Wegener's Granulomatosis: A Review of The Clinical Implications, Diagnosis, and TreatmentDocument3 pagesCE Update: Wegener's Granulomatosis: A Review of The Clinical Implications, Diagnosis, and TreatmentAfif FaiziNo ratings yet

- Ni Hms 490811Document14 pagesNi Hms 490811Trivikram RaoNo ratings yet

- Evaluation and Management of The Dizzy Patient: L M LuxonDocument8 pagesEvaluation and Management of The Dizzy Patient: L M LuxonCarolina Sepulveda RojasNo ratings yet

- Pathology Report On Intracranial Shunt For Treatment of NPHDocument10 pagesPathology Report On Intracranial Shunt For Treatment of NPHSam GitongaNo ratings yet

- Neuroimmunology: Multiple Sclerosis, Autoimmune Neurology and Related DiseasesFrom EverandNeuroimmunology: Multiple Sclerosis, Autoimmune Neurology and Related DiseasesAmanda L. PiquetNo ratings yet

- Auto-Inflammatory Syndromes: Pathophysiology, Diagnosis, and ManagementFrom EverandAuto-Inflammatory Syndromes: Pathophysiology, Diagnosis, and ManagementPetros EfthimiouNo ratings yet

- Myasthenia Gravis - Association of British Neurologists' Management Guidelines.Document8 pagesMyasthenia Gravis - Association of British Neurologists' Management Guidelines.zaquvubeNo ratings yet

- First-Line Immunosuppression in Neuromuscular Diseases.Document14 pagesFirst-Line Immunosuppression in Neuromuscular Diseases.zaquvubeNo ratings yet

- Immunotherapy Guidlines in NMS Diseases.Document21 pagesImmunotherapy Guidlines in NMS Diseases.zaquvubeNo ratings yet

- Toxic Neuropathies - A Practical Approach.Document13 pagesToxic Neuropathies - A Practical Approach.zaquvubeNo ratings yet

- Myasthenia Gravis - Association of British Neurologists' Management Guidelines.Document8 pagesMyasthenia Gravis - Association of British Neurologists' Management Guidelines.zaquvubeNo ratings yet

- Nice DementiaDocument55 pagesNice DementiaMONICANo ratings yet

- Echocardiographic Assessment of Aortic Stenosis - A Practical Guideline From The British Society of Echocardiography.Document41 pagesEchocardiographic Assessment of Aortic Stenosis - A Practical Guideline From The British Society of Echocardiography.zaquvubeNo ratings yet

- Plasma Exchange in Neurological Disease.Document10 pagesPlasma Exchange in Neurological Disease.zaquvubeNo ratings yet

- Patient Decision Aid User Guide On Enteral Tube Feeding For People Living With Severe Dementia PDF 4852697008Document2 pagesPatient Decision Aid User Guide On Enteral Tube Feeding For People Living With Severe Dementia PDF 4852697008zaquvubeNo ratings yet

- The British Society For Rheumatology Guideline For SLEDocument45 pagesThe British Society For Rheumatology Guideline For SLEAlin AmaliyahNo ratings yet

- Thomas 2013Document10 pagesThomas 2013josephNo ratings yet

- BR J Haematol - 2012 - KeelingDocument12 pagesBR J Haematol - 2012 - Keelingsu and claireNo ratings yet

- Diabetes Mellitus The 'Silent Killer' of MankindDocument12 pagesDiabetes Mellitus The 'Silent Killer' of MankindzaquvubeNo ratings yet

- Adult Basic Life Support GuidelinesDocument7 pagesAdult Basic Life Support GuidelineszaquvubeNo ratings yet

- PACES23 Communication Encounter ExamplesDocument21 pagesPACES23 Communication Encounter ExampleszaquvubeNo ratings yet

- Automatic Medicine Vending MachineDocument7 pagesAutomatic Medicine Vending MachinePrajwal PoojaryNo ratings yet

- Impact of Lateral Occlusion Schemes: A Systematic ReviewDocument12 pagesImpact of Lateral Occlusion Schemes: A Systematic ReviewCristobalVeraNo ratings yet

- Role of Pharmacist in Patient CareDocument2 pagesRole of Pharmacist in Patient CareblossomkdcNo ratings yet

- Amoxicillin Capsules Patient Information LeafletDocument7 pagesAmoxicillin Capsules Patient Information Leafletshinta anggia prawestiNo ratings yet

- Level of Awareness on HIV/AIDS among Adolescent MSMDocument19 pagesLevel of Awareness on HIV/AIDS among Adolescent MSMFritz MaandigNo ratings yet

- Educational Module Boosts Staff Knowledge of Hypertension ManagementDocument88 pagesEducational Module Boosts Staff Knowledge of Hypertension ManagementSherwin PazzibuganNo ratings yet

- Critical Nursing IntroductionDocument4 pagesCritical Nursing IntroductionJo Traven AzueloNo ratings yet

- Bone Marrow StudiesDocument3 pagesBone Marrow StudiesDELLNo ratings yet

- The Role of Nursing in Cervical Cancer Prevention and TreatmentDocument5 pagesThe Role of Nursing in Cervical Cancer Prevention and TreatmentLytiana WilliamsNo ratings yet

- 15-05-29 TBTC Soap NoteDocument2 pages15-05-29 TBTC Soap Notejhk0428No ratings yet

- Dentistry: A Case of Drug - Induced Xerostomia and A Literature Review of The Management OptionsDocument4 pagesDentistry: A Case of Drug - Induced Xerostomia and A Literature Review of The Management OptionsSasa AprilaNo ratings yet

- Daftar Pustaka RevisiDocument4 pagesDaftar Pustaka RevisiDita Ayu WidyasariNo ratings yet

- Davis's NCLEX-RN® Success 3E (2012) - MEMORY AIDS - IMPORTANTDocument4 pagesDavis's NCLEX-RN® Success 3E (2012) - MEMORY AIDS - IMPORTANTMaria Isabel Medina MesaNo ratings yet

- Accident and Loss StatisticsDocument13 pagesAccident and Loss StatisticsHajra AamirNo ratings yet

- Active-Screening-Tool-for-Patrons - AFKDocument1 pageActive-Screening-Tool-for-Patrons - AFKParamjit KaurNo ratings yet

- Digital DentistryDocument13 pagesDigital DentistryCesar Augusto Rojas MachucaNo ratings yet

- PB3 NP3Document9 pagesPB3 NP3Angelica Charisse BuliganNo ratings yet

- Delegation in Nursing LeadershipDocument25 pagesDelegation in Nursing LeadershipChiara FajardoNo ratings yet

- Ethiopia Livestock Disease and Food Safety BriefDocument27 pagesEthiopia Livestock Disease and Food Safety BriefBehailu Assefa WayouNo ratings yet

- 20221201151148college Wise P2 BDSDocument17 pages20221201151148college Wise P2 BDSMEGLADONNo ratings yet

- Dds Curriculum. Jalil June 30Document45 pagesDds Curriculum. Jalil June 30তৌহিদ তপুNo ratings yet

- Bahasa Inggris SOALDocument20 pagesBahasa Inggris SOALAyu Nita PangestuNo ratings yet

- Nursing Cover Letter: ( (Company) )Document2 pagesNursing Cover Letter: ( (Company) )Petrisor VasileNo ratings yet