Changing Perceptions of Language in Sociolinguistics

Uploaded by

Shina Hashim JimohChanging Perceptions of Language in Sociolinguistics

Uploaded by

Shina Hashim JimohREVIEW ARTICLE

[Link] OPEN

Changing perceptions of language in

sociolinguistics

Jiayu Wang1 ✉, Guangyu Jin1,2 ✉ & Wenhua Li1 ✉

This paper traces the changing perceptions of language in sociolinguistics. These perceptions

of language are reviewed in terms of language in its verbal forms, and language in vis-à-vis as

1234567890():,;

a multimodal construct. In reviewing these changing perceptions, this paper examines dif-

ferent concepts or approaches in sociolinguistics. By reviewing these trends of thoughts and

applications, this article intends to shed light on ontological issues such as what constitutes

language, and where its place is in multimodal practices in sociolinguistics. Expanding the

ontology of language from verbal resources toward various multimodal constructs has

enabled sociolinguists to pursue meaning-making, indexicalities and social variations in its

most authentic state. Language in a multimodal construct entails the boundaries and dis-

tinctions between various modes, while language as a multimodal construct sees language

itself as multimodal; it focuses on the social constructs, social meaning and language as a

force in social change rather than the combination or orchestration of various modes in

communication. Language as a multimodal construct has become the dominant trend in

contemporary sociolinguistic studies.

T

Introduction

his article will review a range of sociolinguistic concepts and their applications in mul-

timodal studies, in relation to how language has been conceptualized in sociolinguistics.

While there are reviews of specific areas of research in sociolinguistics, including prosody

and sociolinguistic variation (Holliday, 2021), language and masculinities (Lawson, 2020), and

Language change across the lifespan (Sankoff, 2018), there have been few reviews works set out

to delineate the most fundamental ontological questions in sociolinguistic studies; that is, what is

and what constitutes language? How do sociolinguists perceive language in relation to other

semiotic resources that are part and parcel of social meaning-making and social interaction?

Relevant discussions are scattered in passing mainly in the introductory sections of various

sociolinguistic works, such as Blommaert (1999), García and Li (2014) and Makoni and Pen-

nycook (2005). However, there have not been review articles systematically dealing with the

changing perceptions of language in sociolinguistic studies.

These issues are worthwhile to pursue in the sense that though sociolinguistics studies lan-

guage, yet no reviews were done regarding what on earth constitutes language, especially in

relation to a wider range of semiotic resources. What even makes the review more imperative is

1 Central China Normal University, Wuhan, China. 2 Inner Mongolia Agricultural University, Hohhot, China. ✉email: jwang@[Link]; jgy567@[Link];

wenhua@[Link]

HUMANITIES AND SOCIAL SCIENCES COMMUNICATIONS | (2023)10:91 | [Link] 1

REVIEW ARTICLE HUMANITIES AND SOCIAL SCIENCES COMMUNICATIONS | [Link]

that in an increasingly globalized and high-tech world, linguistic than linguists in other disciplines are concerned with the ontology

practices are complicated by the super-diversity of ethnic fluidity, of language regarding its nature and its relation with broader

communications technologies, and globalized cross-cultural art. social structures. In other words, such concerns can, firstly, justify

Centring on the ontological perception of language in socio- the identity of sociolinguistics being either a branch of sociology,

linguistics, this article consists of five sections. After the “Intro- or linguistics, or even more broadly, anthropology. They can also

duction” section, the next section will review traditional (socio) delineate the contour of the macro vis-à-vis micro research

linguistic perceptions of language as written or spoken signs or subjects: are languages seen as separate systems, or inseparable

symbols that people use to communicate or interact with each but relatively fixed systems or an integrated construction in

other. The next section will review representative sociolinguistic relation to their social dimensions of power, ideology and

approaches that place language in multimodal settings which hegemony?

involve the relationship between language and other semiotic Such ontological concerns are important, because different

resources. They are categorized as the conceptualizations of approaches to research may be engendered accordingly. For

“language in multimodal construct” and “language as multimodal instance, variational sociolinguistics is concerned with the lin-

construct”. These conceptualizations share the common feature guistic differences within a language (standard language vis-à-vis

that language is not researched merely in terms of written and its variations in dialects) and examines how these differences are

spoken signs and symbols, but it is probed (1) in relation to its linked to social aspects of linguistic practices, such as gender and

multimodal contexts and (re)contextualization (regarding lan- social status. These differences within a certain category of lan-

guage in multimodal construct), (2) in terms of its own materi- guage may be placed in the changing situations of various lan-

ality and spatiality, and linguistic representations of guage communities or areas (e.g., Labov, 1963, 1966), or in

multimodality, for instance, social (inter)action and “smellscapes” contextualized pragmatic situations (Agha, 2003; Eckert, 2008).

(Pennycook and Otsuji, 2015a) which are in turn conflated with Assumptions of separable or separate languages may be well-

linguistic features (regarding language as multimodal construct). encapsulated in the works regarding language ideology and lin-

The penultimate section and the last section will present a critical guistic differentiation, such as the studies by Kroskrity (1998),

reflection and a conclusion of the review, respectively. Irvine and Gal (2000), as well as considerable other works on

bilingualism or multilingualism. These works treat language as

belonging to different standard systems (e.g., English, French,

Language as written and spoken signs and symbols German, and so on) and can be pursued by “enumerating” these

What constitutes language(s)? Saussure (1916) distinguishes categories. In other words, these standard language systems are

between langue and parole. The former refers to the abstract, seen as having clear boundaries between them, and language can

systematic rules and conventions of the signifying system, while be researched by attributing different linguistic resources to (one

the latter represents language in daily use. Chomsky (1965) refers of) these systems. The stance of the inseparability of language

to them as competence (corresponding to langue) and perfor- problematizes the enumeration of languages, by discrediting their

mance (corresponding to parole). Chomsky (1965) assumes that explanatory potential in linguistic practices. In pedagogical con-

performance is bound up with “grammatically irrelevant condi- texts, transnational students are found using language features

tions as memory limitations, distractions, shifts of attention and beyond the boundaries of language systems (Creese and

interest, and errors (random or characteristic) in applying his Blackledge, 2010; Lewis et al., 2012). In the context of youth or

knowledge of this language in actual performance” (Chomsky, urban culture, there are loosely fixed assumptions between lan-

1965, pp. 3–4). He advocates that the agenda of linguistics should guage and ethnicity (Maher, 2005; Woolard, 1999). In some

be the study of competence of “an ideal speaker-listener, in a globalized contexts, new communications technologies as well as

completely homogeneous speech-community, who knows its (the globalization itself are changing the traditional power structure in

speech community’s) language perfectly” (in brackets original). linguistic practices (Jacquemet, 2005; Jørgensen, 2008; Jørgensen

His conception of the ideal language rules out the “imperfections” et al., 2011). Furthermore, Makoni and Pennycook (2005), by

arising from the influences of social or pragmatic dimensions in advocating the disinvention of languages, problematize the pro-

real language use. This can be seen as the conception of language cess of “historical amnesia” (Makoni and Pennycook, 2005, p.

as innate human competence. By contrast, constructionists have 149) of bi- and multilingualism, and their tradition of enumer-

argued that language cannot be separated from the societal and ating languages which reduces sociolinguistics to at best a

social domain; social reality is constructed through languages “pluralization of monolingualism” (Makoni and Pennycook,

(Berger and Luckmann, 1966), and linguistics should take social 2005, p. 148). However, this does mean that languages cannot be

dimensions into account, as shown by Systemic Functional Lin- probed as standard categories. It holds a more intricate stance: on

guistics developed by Halliday. These approaches to language the one hand, it problematizes the separation of languages, as

studies, nevertheless, do not pay much attention to the ontolo- language is characterized by fluidity in multi-ethnic settings; on

gical issues of language or linguistics concerning what constitutes the other hand, it assumes the fixity of the relationship between a

language, whether languages can be separated from each other, given (standard) language and its corresponding identity, ethni-

and whether there are different conceptions of language(s). city, and other societal factors (Otsuji and Pennycook, 2010);

Sociolinguistics, taking as its departure an interdisciplinary fluidity and fixity, however, are not binary attributes that exclude

attempt to be the sociology regarding linguistic issues or lin- each other; they coexist, mutually influence each other in real-life

guistics regarding sociological issues, faces the ambivalent posi- linguistic practices. By the same token, Blackledge and Creese

tioning of whether it should be sociologically oriented (that is, (2010) and Martin-Jones et al. (2012) also hold a dynamic view

more explanatory) or linguistically oriented (that is, more on language and identity: while language functions as “heritage”

descriptive) (Cameron, 1990). Also, there are contentions (see Blackledge and Creese, 2010, pp. 164–180) and the posi-

regarding whether more attention should be paid to epistemically tioning or maintenance of national identity, the bondage, how-

linguistic minutiae (as in conversation analysis or CA), or to the ever, frequently loosens as it is always contested, resisted and

macro-social interpretation of ideology not necessarily dependent “disinvented” (Makoni and Pennycook, 2005). Table 1 illustrates

on the evident orientation of the participants (as in critical dis- three kinds of sociolinguistic conceptualizations of language.

course analysis, or CDA), as debated in Blommaert (2005) and The above discussion briefly delineates how contemporary

Schegloff (1992, 1998a/1998b, 1999). As such, more sociolinguists sociolinguistic studies attempt to capture the complex ways in

2 HUMANITIES AND SOCIAL SCIENCES COMMUNICATIONS | (2023)10:91 | [Link]

HUMANITIES AND SOCIAL SCIENCES COMMUNICATIONS | [Link] REVIEW ARTICLE

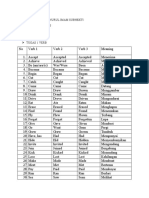

Table 1 Different conceptualizations of language as a verbal form in social linguistics.

Sociolinguistic Basic assumption(s) Paradigms

conceptualizations of language

Language and variations There is a language within which standard language and Variational sociolinguistics (Labov, 1963, 1966; Agha,

its variations exist. 2003; Coupland, 2007; Eckert, 2008; Eckert and

Rickford, 2001)

Separating and enumerating Language belongs to different standard systems (e.g., Linguistic differentiation, bi- and multilingualism

Languages English, French, German, and so on) and can be (Kroskrity, 1998; Irvine and Gal, 2000)

investigated by “enumerating” these categories; that is,

language is seen as belonging to different systems

or codes.

Languages as an Sociolinguistics should focus on linguistic features or Research on language use among transnational students

inseparable system resources (for instance, parts of words or characters (Creese and Blackledge, 2010), youth or urban culture

that do not belong to a certain language, and multimodal (Maher, 2005), new communications technologies and

resources), rather than separate or enumerable standard globalization (Jacquemet, 2005), and the disinvention of

systems; language is characterized by fluidity and it languages (Makoni and Pennycook, 2005);

cannot be separated, while there is fixity regarding the Metrolingualism (Otsuji and Pennycook, 2010);

relationship between a given (standard) language and its translanguaging (García and Li, 2014)

corresponding identity, ethnicity, and other societal

factors.

which the notion of language is construed, resisted or reinvented Martha’s Vineyard, Massachusetts and in New York City. The

in and through practices. Most of these approaches are based on sound change or phonetic features are studied in relation to

the traditional assumption of language as written signs and ethnicity, social stratification and class. Agha (2003) and Eckert

symbols in its verbal forms. Other forms of resources are gen- (2008) also probe the phonetic features or regional change of

erally seen as contexts where these verbal signs and symbols take variations in relation to ethnicity and social and economic status.

place. They are contextual facets that contribute to the ideological In fact, the above-mentioned concerns of sociolinguistics are

and sociological corollary of language use, but they are not seen as also consistent with CDA (see Wang and Jin, 2022; Wang and

ontological components in linguistics. Later developments, which Yang, 2022), especially multimodal critical discourse analysis

integrate multimodal studies into sociolinguistics, show differing (MCDA), which also contributes to the research trend in terms of

stances regarding the ontology of language, as shown in the next language in multimodality. Kress and van Leeuwen (1996) pos-

section. tulates a set of visual grammar based on systemic functional

grammar. Machin (2016) and Machin and Mayr (2012) and other

Language in vis-à-vis as multimodal construct scholars have also adopted MCDA in various types of discourse.

Jewitt (2013, p. 141) defines multimodality as “an inter- Semiotic resources other than language are analysed to reveal the

disciplinary approach that understands communication and social construct of power, ideology, and inequality in relation to

representation to be more than about language”. This should be verbal resources (Wang, 2014, 2016a, 2016b). Language in the

seen as a definition oriented toward social semiotics, in which multimodal construct in sociolinguistics is quite similar to the

different semiotic resources are seen as various modes of repre- social semiotic and critical discourse approach to multimodality:

sentation or communication through semiosis. For a socio- language is seen as one type of resource, amongst other non-

linguistic version of the definition, we prefer to interpret it as language resources (visual, aural, embodied, and spatial) in the

language in vis-à-vis as a multimodal construct. By using the meaning-making process. The difference lies in that socio-

word “construct”, we would like to point out that multimodality linguistic approaches toward language in multimodality have

or multimodal conventions enter into sociolinguistic studies much more focus on social interaction, power and ideology and

because they are socially constructed; that is, sociolinguists their research frequently includes ethnographical data and

research these multimodal dimensions because they are semiotic observations. Language as a multimodal construct, by contrast,

resources and practices which are constructed by social subjects sees language as a more integral part of multimodal resources,

with power, manipulation and ideology. They are not neutral and vice versa; less distinct boundaries are seen as existing

resources by which people communicate information or by which between languages and non-languages. These two trends of

the process of meaning-making, or semiosis, is realized. Instead, conceptions are discussed below.

they are a social construct that constitutes the type of Foucauldian

knowledge in which sociological power and ideology lie at the Language in multimodal construct

core. In this sense, the notions, frameworks, and approaches that To place language studies in the multimodal construct is not a

we discuss as follows are socially critical in nature and are pre- new practice in sociolinguistics. Agha (2003, p. 29) analyses the

dominantly related to socially constructed ideologies such as Bainbridge cartoon, treating accent not as “object of metasemiotic

hegemony, power, and identity. As Makoni and Pennycook scrutiny”, but as an integral element in “the social perils of

(2005) note, languages are “invented” by the dominant (colonial) improper demeanour in many sign modalities” such as dress,

groups through classification and naming in history; they are not posture, gait and gesture. His discussion demonstrates how lan-

neutral practices and they are constructed and invested with guage studies can be embedded in a larger multimodal scope.

ideologies, power and inequality. Sociolinguistics thus needs a Language is contextualized by its peripheral multimodal para-

historically critical perspective. In fact, since its birth, socio- linguistic sign systems. In Eckert (2008, p. 25), the process of

linguistics has been a discipline focusing on language use in “bricolage” (Hebdige, 1984), in which “individual resources can

relation to socially critical issues, such as gender, race, class and be interpreted and combined with other resources to construct a

politics. This focus can date back as early as Labov’s (1963, 1966) more complex meaningful entity”, is linked to the style and

ethnographical research on variations of English on the island of language variations which reflect social meaning. She gives

HUMANITIES AND SOCIAL SCIENCES COMMUNICATIONS | (2023)10:91 | [Link] 3

REVIEW ARTICLE HUMANITIES AND SOCIAL SCIENCES COMMUNICATIONS | [Link]

examples of how the clothing of students at Palo Alto High Language as a multimodal construct

School affords them certain types of styles to convey social A slightly different approach to studies of language in multimodal

meaning. Eckert (2001), Coupland (2003, 2007) and other scho- contexts is to view it as a multimodal construct: either in the way

lars’ research represent the “third-wave” sociolinguistic studies, that language is considered as autonomously constituting the

which see the use of variation in terms of personal and social semiotic texture (e.g., in the art form of the “text art” where text is

styles (Eckert, 2012). Language and other semiotic resources also seen as picture) or in the way that some traditionally

constitute a stylistic complex that makes social meaning and assumed extra-linguistic modes are considered as special forms or

constructs social styles and identities together. Goodwin (2007) dimensions of language. This trend of research includes recent

extensively encompasses multimodal interaction in the exam- studies on language in space, social interactional multimodal

ination of participation, stance and affect in a “homework” discourse analysis, and new concepts or conceptualizations of

interaction between a father and his daughter, where gaze, ges- language in society, as discussed below.

ture, and the spatial environment are taken into account.

Goodwin’s research is partly premised on Bourdieu’s (1991, pp.

81–89) associating bodily hexis with habitus, which is also a Language in space: semiotic landscape, place semiotics, and

notion that is multimodal in itself. The deployment of different discourse geography. Jaworski and Thurlow (2010) review the

bodily modes in different contexts of participation (such as notion of spatialization, that is, the semiotics and discursivity of

homework, archaeology, and surgery) depends on conventions of space (Jaworski and Thurlow, 2010), and the extension of the

various social practices or their respective habitus. notion of the linguistic landscape. By so doing, they frame the

Research regarding language in multimodal construct shares concept of semiotic landscape as encapsulating how written dis-

some common ground with the social semiotic approach towards course interacts with other multimodal discursive resources with

multimodality. First, in communication, there are different modes blurring boundaries in between.

of resources or semiotic types that convey social meaning and In their opinion, space is “not only physically but also socially

embed ideology. Second, these resources consist of language and constructed, which necessarily shifts absolutist notions of space

“non-language”: the former being written or spoken signs and towards more communicative or discursive conceptualizations”

symbols that social actors use to communicate, and the latter (Jaworski and Thurlow, 2010, p. 7). Sociological research on space

being visual, aural, or embodied ones in that language are situ- thus is more oriented toward spatialization, “the different

ated. Third, meaning-making is done through the orchestration processes by which space comes to be represented, organized

of these resources. and experienced” (Jaworski and Thurlow, 2010, p. 6). This

In contrast to social semiotic approaches, with an spatialization—as represented discursively—is intrinsically

anthropology-oriented concern, language in the multimodal multimodal:

construct as a sociological and sociolinguistic approach usually

bases itself on ethnographical observations of social interaction. Echoing the sentiments of Kress and van Leeuwen quoted

Language is seen as a component in social interactional discourse; at the start of this chapter, Markus and Cameron argue that

other semiotic modes or resources are also important resources ‘[b]uildings themselves are not representations’ (p. 15), but

through which language use is contextualized. To be more spe- ways of organizing space for their users; in other words, the

cific, language in multimodal construct shows concerns with way buildings are used and the way people using them

language as one type of semiotic resource that is placed in mul- relate to one another, is largely dependent on the spoken,

timodal contexts in the following aspects: written and pictorial texts about these buildings… Archi-

First, meaning-making through other resources is seen as tecture and language (spoken and written) may then form

“add-ons” to that of language. In other words, language indexes an even more complex, multi-layered landscape (or

social meaning and ideology in collaboration with other types cityscape) combining built environment, writing, images,

of resources. An example is Agha’s (2003) analysis of the as well as other semiotic modes, such as speech, music,

Bainbridge cartoon in which clothes, demeanour, and even photography, and movement…(Jaworski and Thurlow,

body shape work in collaboration with accent in conveying 2010, pp. 19–20)

register and social status. Second, language as one type of social The “spatial turn” (Jaworski and Thurlow, 2010, p. 6) in

meaning-making resource can be conceptualized in relation to sociolinguistics thus adds the analytical dimensions of multi-

the meaning-making process of other resources. For example, modal resources to the traditional concept of the linguistic

the process of “bricolage” is probed in relation to variations landscape. Written language itself does convey social meaning

with their indexed styles and social categorization in terms of and ideologies, while it is situated in materiality (the materials it is

“gender and adolescence” (Eckert, 2008, p. 458). This concept is written on) and spatiality (the places where it appears). The

used to offer clues regarding how “the differential use of vari- concept of the semiotic landscape blurs the traditional boundary

ables constituted distinct styles associated with different com- between language and non-language.

munities of practice” (Eckert, 2008, p. 458). Third, language is Different from social semiotic approaches towards multi-

one of the communicative modes in social interactional dis- modality, researchers of semiotic landscape pay predominant

course. It does not necessarily take the central role, because attention to the “metalinguistic or metadiscursive nature of

other types of resources, such as gestures, gaze, and the envir- ideologies” (Jaworski and Thurlow, 2010, p. 11). In Kallen’s

onment where these actions take place, jointly constitute the words, the concept of semiotic landscape starts from the

social meaning-making process. This can be best encapsulated assumption that “sinage is indexical of more than the ostensive

in Goodwin’s (2007) analysis of the “homework” interaction message of the sign”. (Kallen, 2010, p. 41); signage indexes

between a father and his daughter. In this quite mundane ideologies that are embedded in, or indicated by, different types of

interactional discourse, the father uses different embodied space or spatiality: city centre, tourist places, districts and so on.

actions to negotiate different moral and affective stances Less interest is invested in the process of semiosis regarding how

through the “homework interaction” with his daughter. Con- different modes of signs are orchestrated to communicate

versation as a linguistic resource plays a role in the interaction, information, which is one of the primary endeavours of social

while embodied actions are key factors in affecting these semiotics (Li and Wang, 2022; Wang, 2014, 2019; Wang and Li,

stances. 2022). As such, in ethnographical studies or data analysis,

4 HUMANITIES AND SOCIAL SCIENCES COMMUNICATIONS | (2023)10:91 | [Link]

HUMANITIES AND SOCIAL SCIENCES COMMUNICATIONS | [Link] REVIEW ARTICLE

language, materiality, and spatiality are usually seen as inter- activities. It is an integral part of multimodal construct, where

woven with each other, with no distinct boundaries in between; or other modes (visual, gesture, action, and so on) are not peripheral

at least, boundary-marking is not the primary concern of semiotic or auxiliary, but frequently they also belong to linguistic

landscape. resources, for instance, the visual resources in text arts.

In the same vein, Scollon and Scollon (2003, p. 2) coin the term

“geosemiotics” (or “place semiotics”) which is “the study of the

social meaning of signs and discourses and of our actions in the Multimodal studies from the social interactional perspective.

material world”. Their research objects are signs in public places. There are sociolinguistic approaches towards multimodality that

The conceptual framework of “geosemiotics” sees language as a combine social interactional sociolinguistics (Goffman,

multimodal construct in terms of the following aspects. First, 1959, 1963, 1974), social semiotic approach towards multi-

verbal language is analysed by using social semiotic approaches to modality (Kress and van Leeuwen, 1996), and intercultural

visuals. Code preference (regarding which language is seen as communication (Wertsch, 1998). We summarize these approa-

“primary” language) shown on signs or buildings is analysed by ches as multimodal studies from the social interactional per-

using Kress and van Leeuwen’s (1996, p. 208) conception of spective, which include mediated discourse analysis (Scollon and

compositional meaning indexed by different positions in pictures. Scollon, 2003) and multimodal interaction analysis (Norris,

Second, language is seen as multimodal itself. Language on signs 2004); the latter grew out of the former.

or buildings is analysed in terms of the multimodal inscription Multimodal studies from the social interactional perspective

(see Scollon and Scollon, 2003, pp. 129–142) that includes fonts, focus on people’s daily actions and interactions, and the

letter form, material quality, layering and state changes. Third, environment and technologies with(in) which they take place.

the emplacement (referring to meaning-making through position- This trend of research sees discourse as (embedded in) social

ing signs in different places) in geosemiotics, similar to Jaworski interaction and sets out to investigate social action through

and Thurlow’s (2010) approach towards the semiotic landscape, multimodal resources used in daily interaction, such as gestures,

is predominantly concerned with spatiality and metalinguistic or postures, and language (see Jones and Norris, 2005). In Norris’s

metadiscursive ideology, rather than the interaction and orches- (2004) framework for multimodal interaction analysis, units of

tration of different modes (language vis-à-vis non-language) in analysis are a system of layered and hierarchical actions including

semiosis. the lower-level actions such as an utterance of spoken language, a

Similar to the concepts of semiotic landscape and place gesture, or a posture, and the higher-level actions consisting of

semiotics, Gu (2009, 2012) postulates the framework of four- chains of higher-level actions. Norris (2004) also coins the term

borne discourse and discourse geography. Based on Blommaert’s “modal density” to refer to the complexity of modes a social actor

(2005, p. 2) view of discourse as “language-in-action”, Gu uses to produce higher-level actions.

analyses the language and activities in social actors’ trajectories of The focus on hierarchical levels of actions and the concept of

time and space in the land-borne situated discourse (LBSD): a type “modal density” entail reflections on the question with regard to

of discourse categorized by Gu (2009) according to different types what constitute(s) mode and language. Language in multimodal

of spatiality as carriers and places where the discourses take place. interaction analysis is seen as a type of lower-level action amongst

In Gu’s (2012) conceptualizations, language and discourse are other different embodied resources that are at interactants’

metaphorically spatialized: language is seen in terms of the place disposal. These embodied resources are seen as different modes

where it takes place. Multimodality is evaluated based on space such as gesture, gaze, and proxemics. But arguably gestures and

(Gu, 2009). Though it is arguable to what extent language is seen gazes in Norris (2004) are also seen as forms of language in

as a conflation of modes or semiotic attributes in Gu (2009), his interaction as well. Furthermore, regarding the mode of spoken

work demarcates an ambivalent boundary between language and language, Norris (2004) and her other works methodologically

the “non-language”. Also, in “spatializing” language as discourse treat it as a multimodal construct where the pitches and

geography, it represents language and discourse as a PLACE or intonation are visualized through various fonts in the wave-

SPACE metaphor that is multimodal itself. In addition, it analyses shaped annotation, along with the policeman’s gestures, as shown

the translation between different modes, for instance, the in Fig. 1.

“modalization” of written language into visuals and sounds; Multimodal studies from the social interactional perspective,

visuals are also seen as forms of “modalized” language and vice similar to other sociolinguistic approaches to multimodality,

versa. As such, Gu (2009) also represents the “spatial turn” of target the meta-modal or metadiscursive facets of ideology. This

sociolinguistics which can be seen as the research trend that is done through a bottom-up approach, that is, examining the

regards language as multimodal construct. general social categories of such as power, dominance and

In general, the trend to spatialize language and discourse (or ideology from people’s daily (inter)action. This trend of research

the “spatial turn”), with the concepts or frameworks such as focuses on basic units of actions in people’s daily interaction; the

semiotic landscape, place semiotics, and discourse geography, conception of mode and language is oriented toward seeing

treats language as multimodal construct in the following two language as multimodal; the methodological treatment of

aspects. First, it focuses on metalinguistic or metadiscursive languages also shows this orientation. Multimodal studies from

ideologies that are embedded in different modes of signs or the social interactional perspective are intended to reveal the

symbols; also, Gu’s research metaphorically theorizes social ideology and power embedded in language as action. Overall, they

interaction through multimodality. In other words, it posits that perceive language as a multimodal construct in social (inter)

language itself is multimodal or modalizable in meaning-making. action.

Written language has its multimodal dimensions such as facets of

its inscription including fonts, letterform, material quality,

layering and state changes (Scollon and Scollon, 2003). Different Metrolingualism, heteroglossia, polylanguaging and multi-

forms of language are multimodal in terms of spatiality: they can modality. In the second section of the paper, we mentioned the

be naturally multimodal and aural-visual for instance in televised works on some similar notions such as metrolingualism and

discourse; written language can also be “modalized” (Gu, 2009, p. polylanguaging. In this section, we will review the latest appli-

11) into visuals (Gu, 2009). Overall, language is either considered cation of the notion of metrolingualism in multimodal analysis

as signs in the spatialized system or actions in trajectories of and discuss why other related notions or approaches also

HUMANITIES AND SOCIAL SCIENCES COMMUNICATIONS | (2023)10:91 | [Link] 5

REVIEW ARTICLE HUMANITIES AND SOCIAL SCIENCES COMMUNICATIONS | [Link]

In relation to metrolingualism, Jaworski (2014) briefly reviews

the history of arts and writing, from which he chose the art form

of “text art” as his research subject. Referring to the notion of

metrolingualism, he sees these art forms as “metrolingual art”,

where language interacts with other modes or is seen as part of

the visual mode. He suggests that it be useful to “extend the range

of semiotic features amenable to metrolingual usage to include

whole multimodal resources” (Jaworski, 2014, p. 151). The

multimodal representations in text art are realized by mixing,

meshing and queering of the linguistic features, as well as by its

relation to a “melange of styles, genres, content, and materiality”

(Jaworski, 2014, p. 151). In this regard, the multimodal

affordances (Kress, 2010; Jewitt, 2009) realized by materiality

(e.g., papers, cloths, walls where the language is written), media

(e.g., soundtrack, video, moving images, etc.), and styles (e.g.,

fonts, letterform, layering like add-ons or decorations) are an

integral part of the metrolingualism. Subsequently, he postulates

that it would be useful to align the concept of heteroglossia with

Fig. 1 Selected example from Norris (2004, p. 8). The policeman’s spoken metrolingualism, so as “to extend the idea of metrolingualism

language is treated as a multimodal construct where the pitches and beyond ‘hybrid and multilingual’ speaker practices (Otsuji and

intonation are visualized through various fonts in the wave-shaped Pennycook, 2010, p. 244) and move towards a more ‘generic’ view

annotation, along with his gestures. of metrolingualism as a form of heteroglossia” (Jaworski, 2014, p.

152). In this way, it relates the subject position taken by the

encapsulate the conceptualization regarding language as a mul- producers of the text arts to their social orientation or alignment

timodal construct. as regards power, domination, hegemony, and ideology in a

Metrolingualism is a concept postulated by Otsuji and broader social realm. This is also in line with Bailey’s discussion

Pennycook (2010) originally referring to “creative linguistic about heterogliossia: “(a) heteroglossia can encompass socially

conditions across space and borders of culture, history and meaningful forms in both bilingual and monolingual talk; (b) it

politics, as a way to move beyond current terms such as can account for the multiple meanings and readings of forms that

multilingualism and multiculturalism” (Otsuji and Pennycook, are possible, depending on one’s subject position, and (c) it can

2010, p. 244). Their later works (Pennycook and Otsuji, connect historical power hierarchies to the meanings and valences

2014, 2015a, 2015b) develop the concept and reformulate it as of particular forms in the here-and-now” (Bailey, 2007, pp.

a broader notion encompassing the everyday language use in the 266–267; also quoted in Jaworski, 2014, p. 153). Overall, Jaworski

city and linguistic landscapes in urban settings. (2014) shows how metrolingualism and heteroglossia can be used

In Pennycook and Otsuji (2014, 2015b), metrolingualism to analyse features of language and their place in multimodal

involves the practice of “metrolingual multitasking” (Pennycook construct. He also discusses how other notions which are similar

and Otsuji, 2015b, p. 15), in which “linguistic resources, everyday to metrolingualism may bear a relationship with multimodality in

tasks and social space are intertwined” (Pennycook and Otsuji, that they stress “the importance of linguistic features (rather than

2015b, p. 15). Metrolingualism thus is not only concerned with the discrete languages) as resources for speakers to achieve their

mixed use of linguistic resources (from different languages), but it communicative aims” (Jaworski, 2014, p. 138).

involves how language use is involved in broader multimodal Apart from the concepts of metrolingualism and heteroglossia,

practices such as (embodied) actions accompanying or included in Jaworski (2014) touches upon the relationship between poly-

the metrolingual process, (changing) space or places where these languaging and multimodality, but he does not elaborate on it.

actions and language use take place, and the objects in the Jørgensen (2008) demonstrates how polylanguaging is concerned

environment. Pennycook and Otsuji (2015b) include an olfactory with the use of language features in language practice among

mode in their analysis of the metrolingual practices in cities. Smell adolescents in superdiverse societies. Some of these language

is represented through linguistic or pictorial signs in the city and features “would be difficult to categorize in any given language”

suburb to constitute “smellscapes” in relation to social activities, (Jørgensen et al., 2011, p. 25); that is, they do not belong to any

ethnicities, gender and races. Metrolingual smellscapes are standard language system (e.g., English, Chinese, German). In

represented through the conflation of written and visual signs addition, emoticons are frequently used in communication via

and symbols (e.g., street signs), social activities (e.g., buying and social networking software. If some of these language features do

selling, and riding a bus), objects (e.g., spices), and places or spaces not belong to any given language, it is difficult to say whether they

(e.g., suburb markets, coffee shops, buses and trains). The can be seen as languages. The attention on features of language

conventional distinction between language and the non-language hence blurs the boundary between language and other semiotic

is less important, or not at issue here, as smells have to be resources. Of course, these features can be seen as a type of

represented through language or visuals, and more resources are linguistic (lexical, morphemic or phonemic) units which still

conceptualized as metrolingual other than languages. belong to language, but they are frequently used in multimodal

Language in Pennycook and Otsuji’s (2014, 2015a, 2015b) meaning-making. Below I use Jørgensen et al.’s (2011, p. 26)

conception of metrolingualism, in this regard, is seen as being example (Fig. 2) to illustrate this.

integrated into different types of activities and actions; it is also Jørgensen et al.’s analysis of this example focuses on the

spatialized in the sense that metrolingual practice is seen as “majority boy” using the word “shark”, which is a loan word from

involving the organization of space, the relationship between Arabic. As a majority member, he is using the minority’s language

“locution and location” (Pennycook and Otsuji, 2015b, p. 84), to which he is not entitled. Judging by the interaction, it can be

(historical) layers of cities (Pennycook and Otsuji, 2015b, p. 140). seen that “both interlocutors are aware of the norm and react

The spatialization is intrinsically multimodal, which we have accordingly” (Jørgensen et al., 2011, p. 25). As such he noted that

discussed in earlier sections. one feature of polylanguaging is “the use of resources associated

6 HUMANITIES AND SOCIAL SCIENCES COMMUNICATIONS | (2023)10:91 | [Link]

HUMANITIES AND SOCIAL SCIENCES COMMUNICATIONS | [Link] REVIEW ARTICLE

above, we delineated the ontological perceptions of language in

sociolinguistics, including language as spoken and written signs

and symbols, language in vis-à-vis as a multimodal construct. In

teasing out various trends of approaches, language in socio-

linguistics is found to have undergone several stages of develop-

ment. Language as spoken and written signs and symbols have

been pursued in variational sociolinguistics, bi- and multi-

lingualism, and the latest theoretical and conceptual trends of

research that do not see language as separate and separable sys-

tems or codes. Language in sociolinguistics, however, has been

predominantly placed in nuanced and complicated relationships

with other semiotic resources. Research regarding language in

multimodal constructs sees language and non-language resources

as different modes, or types of resources. These different modes

have boundaries, and efforts are made to see how each mode

combines with each other in meaning-making; language itself is a

Fig. 2 Selected example of polylanguaging from Jørgensen et al. (2011, p. distinctive type of mode, interdependent with but different from

26). The “majority boy” makes use of resources from the minority’s other modes. Research regarding language as a multimodal

language (the word “shark”). construct sees language itself as multimodal, language is spatia-

with different ‘languages’ even when the speaker knows very little lized (that is, probed in relation to various spatiality and mate-

of these” (Jørgensen et al., 2011, p. 25). riality where they appear); in the social interactional approach to

What also needs attention but is not discussed by Jørgensen multimodality, it is embodied and seen as embedded in a layered

et al. (2011), is the interlocutors’ creative way to use these features and hierarchical system of modes (including gesture, posture, and

in polylanguaging: the word “shark” is written as a prolonged intonation) in social interaction; in the latest concepts built on

“shaarkkk” in terms of its phonetic and visual effects. The creative languaging, language is regarded as “inventions” (Makoni and

configuration of the language feature “shark” functions to draw Pennycook, 2005), as cross- and trans-cultural practice, instead of

other interlocutors’ attention toward the polylanguaging practice. separable and enumerable codes, or system. Language is entan-

The emoticon “:D” following it is to demonstrate that the speaker gled and integrated with objects (for instance, signage, and the

knows that he is using language features by violating the “normal” materiality where it appears) and multitasking with embodied

rules; that is, he is using the minority language features to which resources (gestures, talking, and simultaneously doing other

he is not entitled. The repeated words “cough, cough”, followed things).

by the emoticon “:D”, also demonstrate this. Expanding the ontology of language from verbal resources

Polylanguaging, as formulated by Jørgensen et al. (2011), toward various multimodal constructs has enabled sociolinguists

deviates from the tradition of multilingualism to enumerate to pursue meaning-making, indexicalities and social variations in

languages, but focuses on language features that may not belong its most authentic state. Language itself is multimodal, though it

to any given language. In this sense, the emoticons or creative cannot be denied that language and other modes do have

configuration of words can also be seen as language features—the boundaries and distinctions (yet not always being so). Whenever

language features that are creatively used by a virtual community of a language is spoken, the stresses, intonations, and paralinguistic

(young) netizens in communication. These features are multimodal resources are all integrated into it. Focusing on language per se

in the following aspects. First, they visualize the polylanguaging has generated fruitful outcomes in sociolinguistic studies, but

practice by creating new forms of words, for instance, the placing language in the multi-semiotic resources has innovated

prolonged word “shaarkkk”. This creation itself is in fact also a the field and it has become the dominant trend in contemporary

process of polylanguaging, in the sense that it uses the features of sociolinguistics. Both languages in or as multimodal constructs

common language, or language in people’s daily life (that is, non- have captured the complex ways in which language interacts with

cyber language) to create new cyber-language that is used by multi-subjects, materiality, objects and spatiality. But it may be

members of a virtual community. Second, these language features found that the latest research in sociolinguistics comes to

utilize the multimodal resources of embodiment in polylanguaging. increasingly see language itself as an intricate multimodal con-

For example, emoticons use different letters or punctuations (as struct, as encapsulated by various new concepts and theories

language features from people’s daily written language) to including translanguaging, metrolingualism, and polylanguaing,

represent different facial expressions and emotions. The repetition in the contexts of globalization, migration, multi-ethnicity, and

of the words “cough, cough”, as “a reference to a cliché way of new communication technologies. Language is not only seen as

expressing doubt or scepticism” (Jørgensen et al., 2011, p. 27) also separable codes and systems spoken or written by a different

takes on an embodied stance. It shows that the interlocutors are group of people, but it entails a wider range of communicative

aware that the majority boy is using the minority’s language to repertoires including embodied meaning-making, objects and the

which he is not entitled. Hence, this embodied stance indexes the environment where the written or spoken signs are placed. It

polylanguaging practice. To summarize what is discussed above, hence may be speculated that sociolinguistics will be increasingly

polylanguaging entails seeing language as a multimodal construct, less concerned with the boundaries of language and non-language

as interlocutors creatively adapt language features in daily resources, but will focus more on the social constructs, social

communication (face-to-face or written communication not meaning, and language as a force in social change. The enu-

involving the internet) or utilize embodied language features when merating and separating way of studying language and multi-

polylanguaging in online communication. modality—that is, delineating inter-semiotic boundaries and

focusing on how modes of communication are combined in

meaning-making—has generated various outcomes, especially in

Discussion and a critical reflection the field of grammar-oriented social semiotic research and

In the sections “Language as written and spoken signs and MCDA. However, contemporary sociolinguistic studies have

symbols” and “Language in vis-à-vis as multimodal construct” immensely expanded their scope toward a wider range of areas

HUMANITIES AND SOCIAL SCIENCES COMMUNICATIONS | (2023)10:91 | [Link] 7

REVIEW ARTICLE HUMANITIES AND SOCIAL SCIENCES COMMUNICATIONS | [Link]

other than discursive, grammatical, and communicative. The Received: 12 September 2022; Accepted: 20 February 2023;

three research paradigms regarding language as a multimodal

construct reviewed in “Language as multimodal construct” have

proved themselves as a feasible approach toward language in

social interaction, geo-semiotics, and language use in ethno-

graphical and multi-ethnic settings. The ontology of language in References

sociolinguistics, in this regard, may be perceived in terms of the Agha A (2003) The social life of cultural value. Language Commun

sociology and societal facets of multimodal construct, rather than 23(3–4):231–273

language placed in a multitude of semiotic types or the Berger P, Luckmann T (1966) The social construction of reality: a treatise in the

sociology of knowledge. Doubleday, New York

verbal resources per se. A critical reflection on the ontology of

Blackledge A, Creese A (2010) Multilingualism: a critical perspective. Continuum,

language is one of the prerequisites of innovations in con- London

temporary linguistics, which is also the objective of this com- Blommaert J (Ed.) (1999) Language ideological debates, vol. 2. Walter de Gruyter,

prehensive review. Berlin

Blommaert J (2005) Discourse: a critical introduction. Cambridge University Press,

Cambridge

Bourdieu P (1991) Language and symbolic power [Thompson JB (ed and introd)]

Conclusion (trans: Raymond G, Adamson M). Polity Press/Blackwell, Cambridge

As can be seen through the above discussion, there are several Bailey B (2007) Heteroglossia and boundaries. In: Heller M (Ed.) Bilingualism: a

versions of the perception of language in sociolinguistics. First, social approach. Palgrave Macmillan, New York, pp. 257–274

perceptions of language as a written or verbal system are moving Cameron D (1990) Demythologizing sociolinguistics: why language does not reflect

society. In: Joseph J, Taylor T (eds) Ideologies of language. Routledge, Lon-

from, or have moved from, the enumerating traditions bi- or

don, pp. 79–93

multi-lingualism towards seeing language as an inseparable Chomsky N (1965) Aspects of the theory of syntax. MIT Press, Cambridge,

entity with fixity and fluidity. In other words, new approaches in Massachusetts

sociolinguistics come to see languages as comprising different Coupland N (2003) Sociolinguistic authenticities. J Sociolinguist 7(3):417–431

features, repertories, or resources, rather than different or dis- Coupland N (2007) Style: language variation and identity. Cambridge University

Press, Cambridge

crete standard languages such as English, French, German and Creese A, Blackledge A (2010) Translanguaging in the bilingual classroom: a

so on. The negotiation, construction, or attribution of ethnicity, pedagogy for learning and teaching? Mod Language J 94:103–115

identity, power and ideologies through language also has taken Eckert P, Rickford JR (Eds.) (2001) Style and sociolinguistic variation. Cambridge

on a more dynamic and diverse look. Second, there is socio- University Press, Cambridge

linguistic research that places language within the multimodal Eckert P (2008) Variation and the indexical field. J Sociolinguist 12(4):453–476

construct. Language is seen as being contextualized by other Eckert P (2012) Three waves of variation study: the emergence of meaning in the

study of sociolinguistic variation. Annu Rev Anthropol 41(1):87–100

multimodal semiotics that is seen as “non-language”. However, García O, Li W (2014) Translanguaing: language, bilingualism and education.

more research comes to see language as multimodal construct; Palgrave Macmillan, London

that is, language, be it written or spoken, is multimodal in itself Goffman E (1959) The presentation of self in everyday life. Doubleday, New York,

as it comprises multimodal elements such as type, font, mate- NY

riality, intonation, embodied representations and so on. It is also Goffman E (1963) Behavior in public places. Free Press, New York, NY

Goffman E (1974) Frame analysis. Harper & Row, New York, NY

activated (seen as actions or activities) or spatialized in different Goodwin C (2007) Participation, stance, and affect in the organization of activities.

approaches such as mediated discourse analysis, multimodal Discourse Soc 18(1):53–73

interaction analysis, geosemiotics, semiotic landscape, and Gu Y (2009) Four-borne discourses: towards language as a multi-dimensional city

metrolingualism discussed earlier. Third, these changing per- of history. In: Li W, Cook V (eds.) Linguistics in the real world. Continuum,

ceptions of languages in sociolinguistics result from researchers’ London, pp. 98–121

Gu Y (2012) Discourse geography. In: Gee JP, Hanford M (eds.) The Routledge

innovative efforts to view language from different perspectives. handbook of discourse analysis. Routledge, London, pp. 541–557

More importantly, they arise from the fact that language itself is Hebdige D (1984) Framing the youth ‘problem’: the construction of troublesome

also changing as society changes. As mentioned in the begin- adolescence. In: Garms-Homolová V, Hoerning EM, Schaeffer D (eds.)

ning, the world has been increasingly globalized and commu- Intergenerational Relationships. Lewiston, NY: C. J. Hogrefe, pp.184–195

nications technologies have fundamentally changed the ways Holliday N (2021) Prosody and sociolinguistic variation in American Englishes.

Annu Rev Linguist 7:55–68

people interact with each other. Linguistic practices are com-

Irvine JT, Gal S (2000) Language ideology and linguistic differentiation. In:

plicated by the super-diversity of ethnic fluidity (e.g., the Kroskrity PV (ed.) Regimes of language: ideologies, polities, and identities.

diversity of ethnic groups and the ever-present changes in ethnic School of American Research Press, Santa Fe, pp. 35–84

structure), communications technologies, and globalized cross- Jaworski A (2014) Metrolingual art: multilingualism and heteroglossia. Int J Biling

cultural art. 18(2):134–158

Jaworski A, Thurlow C (eds.) (2010) Semiotic landscapes: language, image, space.

In sum, it can be argued that contemporary sociolinguistics has

Continuum, New York

become increasingly concerned with languaging (trans-, poly-, Jewitt C (2009) Different approaches to multimodality. In: Jewitt C (ed) The

metro-, and pluri- and so on), rather than languages as a type of Routledge handbook of multimodal analysis. Routledge, Abingdon, pp. 28–39

(static and fixed) verbal resource with demarcated boundaries Jewitt C (2013) Multimodality and digital technologies in the classroom. In: de

separating them from other multimodal resources. Language is Saint-Georges I, Weber J (eds) Mulitlingualism and multimodality: current

challenges for educational studies. Sense Publishing, Boston, pp. 141–152

multimodal; it is embedded in or represents social activities,

Jørgensen JN (2008) Poly-lingual languaging around and among children and

places or spaces, objects, and smells. Language in society belongs adolescents. Int J Multiling 5(3):161–176

to and constitutes the “semiotic assemblage” (Pennycook, 2017) Jørgensen JN, Karrebæk MS, Madsen LM, Møller JS (2011) Polylanguaging in

that can be better analysed holistically so as to reach an under- superdiversity. Diversities 13(2):23–37

standing of “how different trajectories of people, semiotic Jacquemet M (2005) Transidiomaticpractices: language and power in the age of

resources and objects meet at particular moments and places” globalization. Language Commun 25:257–277

Jones R, Norris S (2005) Discourse as action/discourse in action. In: Norris S, Jones

(Pennycook, 2017, p. 269). At a fundamental level of socio- R (eds) Discourse in action: introducing mediated discourse analysis. Rou-

linguistic ontology, this trend of research reflects the changing tledge, London, pp. 1–3

ways in which sociolinguists come to understand what language is Kallen J (2010) Changing landscapes: language, space and policy in the Dublin

and how it should be understood as part of a more general range linguistic landscape. In: Jaworski A, Thurlow C (eds) Semiotic landscapes:

of semiotic practices. language, image, space. New York: Continuum, pp. 41–58

8 HUMANITIES AND SOCIAL SCIENCES COMMUNICATIONS | (2023)10:91 | [Link]

HUMANITIES AND SOCIAL SCIENCES COMMUNICATIONS | [Link] REVIEW ARTICLE

Kress GR (2010) Multimodality: a social semiotic approach to contemporary Wang J, Li W (2022) Situating affect in Chinese mediated soundscapes of suona.

communication. Routledge, London Soc Semiot. [Link]

Kress GR, van Leeuwen T (1996) Reading Images: the grammar of graphic design. Wang J, Yang M (2022) Interpersonal-function topoi in Chinese central govern-

Routledge, London ment’s work report (2020) as epidemic (counter-) crisis discourse. J Language

Kroskrity PV (1998) Arizona Tewa Kiva speech as a manifestation of linguistic Politics. [Link]

ideology. In: Schieffelin BB, Woolard KA, Kroskrity P (eds) Language Wertsch JV (1998) Voices of the mind: a sociocultural approach to mediated

ideologies: practice and theory. Oxford University Press, New York, pp. action. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA

103–122 Woolard K (1999) Simultaneity and bivalency as strategies in bilingualism. J

Labov W (1963) The social motivation of a sound change. Word 19(3):273–309 Linguist Anthropol 8(1):3–29

Labov W (1966) Hypercorrection by the lower middle class as a factor in linguistic

change. Sociolinguistics 1966:84–113

Lawson R (2020) Language and masculinities: history, development, and future. Acknowledgements

Annu Rev Linguist 6(1):409–434 Our thanks are extended to Dr. William Dezheng Feng for his constructive advice on the

Lewis WG, Jones B, Baker C (2012) Translanguaging: origins and development earlier drafts of the paper. This work is supported by the National Social Science

from school to street and beyond. Educ Res Eval 18(7):641–654 Foundation of China (Project No. 18CYY050); the Foreign Language Education Foun-

Li W, Wang J (2022) Chronotopic identities in contemporary Chinese poetry dation of China (Project No. ZGWYJYJJ11A030); and the Self-Determined Research

calligraphy. Poznan Stud Contemp Linguist 58(4):861–884 Funds of CCNU from MOE for basic research and operation (Project No.

Machin D (2016) The need for a social and affordance-driven multimodal critical CCNU20TD008).

discourse studies. Discourse Soc 27(3):322–334

Machin D, Mayr A (2012) How to do critical discourse analysis: a multimodal Author contributions

introduction. Sage, London All three authors contributed to the conception and design of the study. JW mainly

Maher J (2005) Metroethnicity, language, and the principle of Cool. Int J Sociol participated in drafting the work. GJ revised it critically for important intellectual con-

Language 11:83–102 tent. WL participated in major intellectual contributions to the Chinese versions of the

Makoni S, Pennycook A (2005) Disinventing and (re)constituting languages. Crit paper (unpublished); her ideas and points are integrated into the final version of this

Inq Language Stud 2(3):137–156 paper. All three authors are corresponding authors responsible for the final approval of

Martin-Jones M, Blackledge A, Creese A (eds) (2012) The Routledge handbook of the version to be published.

multilingualism. Routledge, London

Norris S (2004) Analyzing multimodal interaction: a methodological framework.

Routledge, London Competing interests

Otsuji E, Pennycook A (2010) Metrolingualism: fixity, fluidity and language in flux. The authors declare no competing interests.

Int J Multiling 7:240–254

Pennycook A (2017) Translanguaging and semiotic assemblages. Int J Multiling

14(3):1–14

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of

Pennycook A, Otsuji E (2014) Metrolingual multitasking and spatial repertoires:

the authors.

‘Pizza mo two minutes coming’. J Socioling 18(2):161–184

Pennycook A, Otsuji E (2015a) Making scents of the landscape. Linguist Landsc

1(3):191–212 Informed consent

Pennycook A, Otsuji E (2015b) Metrolingualism. Language in the city. Routledge, This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of

New York the authors.

Sankoff G (2018) Language change across the lifespan. Annu Rev Linguist

4:297–316

Schegloff EA (1992) In another context. In: Duranti A, Goodwin C (eds) Additional information

Rethinking context: language as an interactive phenomenon. Cambridge Correspondence and requests for materials should be addressed to Jiayu Wang, Guangyu

University Press, Cambridge, pp. 191–227 Jin or Wenhua Li.

Schegloff EA (1998a) Positioning and interpretative repertoires: conversation

analysis and poststructuralism in dialogue: reply to Wetherell. Discourse Soc Reprints and permission information is available at [Link]

9(3):413–416

Schegloff EA (1998b) Reply to Wetherell. Discourse Soc 9(3):457–60 Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in

Schegloff EA (1999) ‘Schegloff’s texts’ as ‘Billig’s data’: a critical reply. Discourse published maps and institutional affiliations.

Soc 10(4):558–572

Scollon R, Scollon S (2003) Discourses in place: language in the material world.

Routledge, New York

Saussure F (1916) Course in general linguistics. Duckworth, London Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons

Wang J (2014) Criticising images: critical discourse analysis of visual semiosis in Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing,

picture news. Crit Arts 28(2):264–286 adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give

Wang J (2016a) Multimodal narratives in SIA’s “Singapore Girl” TV advertise- appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative

ments—from branding with femininity to branding with provenance and Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party

authenticity? Soc Semiot 26(2):208–225 material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless

Wang J (2016b) A new political and communication agenda for political discourse indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the

analysis: critical reflections on critical discourse analysis and political dis- article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory

course analysis. Int J Commun 10:19 regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from

Wang J (2019) Stereotyping in representing the “Chinese Dream” in news reports the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit [Link]

by CNN and BBC. Semiotica 2019(226):29–48 licenses/by/4.0/.

Wang J, Jin G (2022) Critical discourse analysis in China: history and new

developments. In: Aronoff M, Chen Y, Cutler C (eds) Oxford Research

Encyclopedia of Linguistics. Oxford University Press. [Link] © The Author(s) 2023

acrefore/9780199384655.013.909

HUMANITIES AND SOCIAL SCIENCES COMMUNICATIONS | (2023)10:91 | [Link] 9

You might also like

- McLuhan's Interdisciplinary Media InsightsNo ratings yetMcLuhan's Interdisciplinary Media Insights24 pages

- Language Ecology & Ecolinguistics DebateNo ratings yetLanguage Ecology & Ecolinguistics Debate12 pages

- Naoko Saito, Ourselves in Translation - Stanley Cavell and Philosophy As AutobiographyNo ratings yetNaoko Saito, Ourselves in Translation - Stanley Cavell and Philosophy As Autobiography15 pages

- Machin - A Course in Critical Discourse Analysis (Curso)No ratings yetMachin - A Course in Critical Discourse Analysis (Curso)7 pages

- Fishman Et Al - The Rise and Fall of The Ethnic Revival - 1985 PDFNo ratings yetFishman Et Al - The Rise and Fall of The Ethnic Revival - 1985 PDF549 pages

- Earth As Praxis - Environmental HumanitiesNo ratings yetEarth As Praxis - Environmental Humanities14 pages

- Mary Bucholz and Kira Hall Sociocultural LinguisticsNo ratings yetMary Bucholz and Kira Hall Sociocultural Linguistics31 pages

- Happiness and Domestic Life - The Influence of The Home On Subjective and Social Well-Being-Routledge (2022)No ratings yetHappiness and Domestic Life - The Influence of The Home On Subjective and Social Well-Being-Routledge (2022)264 pages

- Christopher Alexander's Battle For Beauty in A World Turning Ugly: The Inception of A Science of Architecture?No ratings yetChristopher Alexander's Battle For Beauty in A World Turning Ugly: The Inception of A Science of Architecture?31 pages

- Eco-Translation - Translation and Ecology in The Age of The AnthropoceneNo ratings yetEco-Translation - Translation and Ecology in The Age of The Anthropocene188 pages

- Silverstein - The Implications of (Models Of) Culture For LanguageNo ratings yetSilverstein - The Implications of (Models Of) Culture For Language20 pages

- Discourse and Political Culture The Language of The Third Way - Kranert, Michael100% (1)Discourse and Political Culture The Language of The Third Way - Kranert, Michael318 pages

- A-Teun A. Van Dijk - Prejudice in Discourse - An Analysis of Ethnic Prejudice in Cognition and Conversation (1984)No ratings yetA-Teun A. Van Dijk - Prejudice in Discourse - An Analysis of Ethnic Prejudice in Cognition and Conversation (1984)180 pages

- Hffding 2023 Expandingphenomenologicalmethods OUPhandbookNo ratings yetHffding 2023 Expandingphenomenologicalmethods OUPhandbook20 pages

- (Palgrave Studies in Languages at War) Michael Kelly, Catherine Baker (Auth.) - Interpreting The Peace - Peace Operations, Conflict and Language in Bosnia-Herzegovina-Palgrave Macmillan UK (2013)No ratings yet(Palgrave Studies in Languages at War) Michael Kelly, Catherine Baker (Auth.) - Interpreting The Peace - Peace Operations, Conflict and Language in Bosnia-Herzegovina-Palgrave Macmillan UK (2013)249 pages

- Towards A Critical Cognitive LinguisticsNo ratings yetTowards A Critical Cognitive Linguistics19 pages

- Local Identity Amid Globalization: YanesenNo ratings yetLocal Identity Amid Globalization: Yanesen8 pages

- Gillborn, 2015 - Race, Class, Gender and Disability in EducationNo ratings yetGillborn, 2015 - Race, Class, Gender and Disability in Education11 pages

- Fraser - An Account of Discourse MarkersNo ratings yetFraser - An Account of Discourse Markers28 pages

- (Palgrave Politics of Identity and Citizenship Series) Elke Murdock (Auth.) - Multiculturalism, Identity and Difference - Experiences of Culture Contact-Palgrave Macmillan UK (2016) PDFNo ratings yet(Palgrave Politics of Identity and Citizenship Series) Elke Murdock (Auth.) - Multiculturalism, Identity and Difference - Experiences of Culture Contact-Palgrave Macmillan UK (2016) PDF358 pages

- Heft Affordances, Dynamic Experience, and The Challenge of Reification 2003No ratings yetHeft Affordances, Dynamic Experience, and The Challenge of Reification 200333 pages

- Beyond Basic Communication: The Role of The Mother Tongue in Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy (CBT)No ratings yetBeyond Basic Communication: The Role of The Mother Tongue in Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy (CBT)12 pages

- Some Practices For Referring To Persons in Talk-in-InteractionNo ratings yetSome Practices For Referring To Persons in Talk-in-Interaction51 pages

- In The Fullness of Time - M. M. Bakhtin in Discourse and in LifeNo ratings yetIn The Fullness of Time - M. M. Bakhtin in Discourse and in Life250 pages

- Speaking Our Minds-Narrating Mental Illness SyllabusNo ratings yetSpeaking Our Minds-Narrating Mental Illness Syllabus8 pages

- (Ebook PDF) The Anthropology of Language: An Introduction To Linguistic Anthropology 4th Edition PDF Download71% (7)(Ebook PDF) The Anthropology of Language: An Introduction To Linguistic Anthropology 4th Edition PDF Download47 pages

- A Study of Conversational Structure Paper Submitted To Fulfill The Requirements of Pragmatics Final ExamNo ratings yetA Study of Conversational Structure Paper Submitted To Fulfill The Requirements of Pragmatics Final Exam18 pages

- Construing Experience Through Meaning PDFNo ratings yetConstruing Experience Through Meaning PDF672 pages

- Social Reconstruction Curriculum and Technology EducationNo ratings yetSocial Reconstruction Curriculum and Technology Education11 pages

- AMethodof Phenomenological InterviewingNo ratings yetAMethodof Phenomenological Interviewing10 pages

- Halverson. Gravitational Pull HypothesisNo ratings yetHalverson. Gravitational Pull Hypothesis38 pages

- Internet Pragmatics Conference AbstractsNo ratings yetInternet Pragmatics Conference Abstracts85 pages

- Time Conception and Cognitive LinguisticsNo ratings yetTime Conception and Cognitive Linguistics31 pages

- Epistemological and Theoretical Foundations in Language Policy and PlanningNo ratings yetEpistemological and Theoretical Foundations in Language Policy and Planning145 pages

- Extrastatecraft: The Power of Infrastructure Space by Keller EasterlingNo ratings yetExtrastatecraft: The Power of Infrastructure Space by Keller Easterling4 pages

- What Linguists Need From The Social SciencesNo ratings yetWhat Linguists Need From The Social Sciences7 pages

- English Fal May June Grade 10 p1 Memorundum 2025No ratings yetEnglish Fal May June Grade 10 p1 Memorundum 202511 pages

- Approach To Using Literature With The Language Learner100% (1)Approach To Using Literature With The Language Learner5 pages

- Speech-Language Pathologists and Prosody Clinical Practices andNo ratings yetSpeech-Language Pathologists and Prosody Clinical Practices and15 pages

- DR Emile Bellewes - Ecolinguistics and Environment in Education - Language, Culture and Textual Analysis (Bloomsbury Advances in Ecolinguistics) - Bloomsbury Academic (2024)100% (1)DR Emile Bellewes - Ecolinguistics and Environment in Education - Language, Culture and Textual Analysis (Bloomsbury Advances in Ecolinguistics) - Bloomsbury Academic (2024)265 pages

- Degree of Comparison: (Positive Degree, Comparative Degree, & Superlative Degree)No ratings yetDegree of Comparison: (Positive Degree, Comparative Degree, & Superlative Degree)25 pages

- How To Increase Reading Ability - A Guide To Developmental - Albert Josiah Harris - 1970-01-01 - D - MacKay Co - Anna's ArchiveNo ratings yetHow To Increase Reading Ability - A Guide To Developmental - Albert Josiah Harris - 1970-01-01 - D - MacKay Co - Anna's Archive600 pages

- Language Shapes The Way We Think, and Determines What We Can Think About.No ratings yetLanguage Shapes The Way We Think, and Determines What We Can Think About.18 pages

- Nama: Ikhtiar Nurul Imam Subhekti NIM: 1917202193 Kelas: F-17No ratings yetNama: Ikhtiar Nurul Imam Subhekti NIM: 1917202193 Kelas: F-174 pages