Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Ecaade2013 178.content

Uploaded by

sevanscesOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Ecaade2013 178.content

Uploaded by

sevanscesCopyright:

Available Formats

Walkability as a Performance Indicator for Urban Spaces

Strategies and tools for the social construction of experiences

Burak Pak1, Johan Verbeke2

LUCA, Sint-Lucas School of Architecture, KU Leuven, Faculty of Architecture

http://arch.kuleuven.be

1

burak.pak@kuleuven.be,2johan.verbeke@kuleuven.be

Abstract. This paper frames walkability as a performance indicator for urban spaces

and critically addresses some of the existing evaluation methods. It introduces alternative

strategies and tools for enabling the collective evaluation of walkability and discusses

how experiences of the citizens can possibly lead to a social construct of walkability.

This discussion is elaborated by a pilot study which includes exploratory research,

social-geographic web services and heat maps. Using these tools and methods, it was

possible to derive various experiential and environmental spatial qualities, extract

problems and identify problematic areas. From these we have learned that walkability

may serve as a fruitful conversation framework and a participatory research concept.

Furthermore, we were able to develop ideas for solutions to design and planning

problems.

Keywords. Walkability; experiential knowledge; collective mapping; social web.

INTRODUCTION

This study is based on two main motivations: the mance dimensions: connectivity of path network,

potential of walkability as a performance indicator linkage with other transportation modes, land use

for urban spaces and the new possibilities offered patterns, safety (traffic/social), the quality of the

by the social media and novel information and path context, spatial definitions and overall explora-

communication technologies (ICT) for the collec- bility (Southworth, 2005). Despite the wide range of

tive location-based representation of individual ex- aspects and dimensions above, humans live in and

periences. perceive all of these dimensions as a whole. There-

To begin with, walkability is not a new concept fore, collecting and processing the experiences of

and has been prescribed as an essential urban qual- the citizens at a large scale can possibly lead to a so-

ity by numerous planners during the last century. In cial construct of walkability.

brief, walkability is a measure of how walking friend- Furthermore, web 2.0-based social media and

ly an area is. geographic services are potential tools for the col-

Various evaluation methods have been intro- lective understanding of walkability. By using these

duced from the perspectives of medicine, transpor- tools, dynamic knowledge acquired through lived

tation, environmental design and psycho-sociology, experience can be used as a vital resource for re-

including a significant number of alternative perfor- search and design purposes. Alternative location-

Crowdsourcing and Sensing - Volume 1 - Computation and Performance - eCAADe 31 | 423

based maps can be created by involving the public urbanization accompanied by the gigantism of the

to represent urban dynamics that are not accessible brutal international style development which defied

to authorities. Multiple perspectives of individuals, the human scale. The suburban development model

social groups and organizations can be dynamically of development disconnected the residential areas

represented and socially discussed. By working with from the business districts, creating auto-depend-

alternative depictions of urban environments, one ent commuters and traffic congestion [1]. Dominant

can simultaneously account for representations of modernist planning approaches put a low priority

the existing urban environment and imaginations of on pedestrianism and weakened the traditional func-

different realities. Such strategies provide different tion of city place as a meeting place and social forum

frameworks for discussion, knowledge-construction for the inhabitants (Gehl, 2010).

as well as participation (Pak and Verbeke, 2012). Jane Jacobs was one of the first critics to defend

In this context, in Section 2, we will start with a the street life and walkability. In her legendary book,

brief discussion of walkability and critically address “The Death and Life of Great American Cities” she

some of the existing evaluation methods. In section reserved the first two chapters on the uses of side-

3 we will introduce a suit of open-source tools for walks and described the benefits of safe, diverse and

collection and rating of walkability. This will be fol- lively streets (Jacobs, 1961).

lowed by the demonstration of a pilot study and a Around the same time, Lynch (1961) in his semi-

brief review of the findings. nal book “The Image of the City” drew attention to

In conclusion (Section 4), we will reflect on the the importance of the walking experience and of-

strengths, short comings and potentials of experi- fered mental maps of paths, edges, districts, nodes

ential walkability evaluation and draw future pros- and landmarks for analysis. He developed a theory

pects. of “good city form” through which the performance

of the city is evaluated in terms of various qualities

WALKABILITY AS A PERFORMANCE such as vitality, sense, fit, accessibility and control. He

INDICATOR focused on sense among the other qualities, which

One of the earliest references to pedestrian-orient- according to him consists of identity, structure, mean-

ed development was Perry’s (1929) introduction of ing, transparency, congruence and legibility.

the “Five-Minute Walk” as an essential urban design Today, walkability is considered as an essential

tool. It is possible to trace the origins of these ideas urban quality and referred to as closely related to ex-

to Howard’s Garden City and Drummond’s Chicago perience of a sense of place, social cohesion as well

plans (Johnson, 2002). as resilience by the Charter of the New Urbanism [2].

Perry (1929) prescribed the 5-minute walk (0.4 Influential practitioners such as Gehl (2010) have

km radius, the average distance that a pedestrian urged planners and architects to shift their focus to-

would desire to walk) as the central design com- wards the human dimension and strengthen pedes-

ponent for structuring a Neighborhood Unit con- trianism as an integrated design strategy as well as a

sidering the walking distances from residential to comprehensive city policy.

non-residential components. It would not be wrong In various studies, walkability is referenced as a

to claim that Perry’s concept made a significant im- predictor of public health (Frank et al., 2009), house

pact on the practices and still applies to contempo- values (Cortright, 2009) and pursued as a top pre-

rary design and planning at a large extent (Patricios, requisite for environmental sustainability by LEED

2002). ND [3] and neighborhood vitality [2].

In Europe and the USA, walkability became In the last decade, various walkability assess-

even more important after the Second World War, ment methods have been developed. Among these

following the automobile invasion and rapid sub- were: estimation using data from Geographical In-

424 | eCAADe 31 - Computation and Performance - Volume 1 - Crowdsourcing and Sensing

Figure 1

An unwalkable street rated

as “very walkable” by Walk

Score, a tool which estimates

walkability by GIS records

of amenities which can be

reached on foot (located

within 400 meters to 1.6

km) [4].

formation Systems (Frank et al., 2005), systematic walkability is a direct function of how many destina-

pedestrian and cycling environmental scan (SPACES) tions are located within 400 meters to 1.6 km.

(Pikora et al., 2006), Google-based Walkscore [4] and In conclusion, in order to properly diagnose ur-

citizen surveys such as the Neighborhood Environ- ban problems and create novel design solutions, it is

ment Walkability Scale (NEWS) (Saelens et. al., 2002). necessary to create a finer lens in terms of various di-

Print surveys such as NEWS aim at individual mensions, time, scale and learning from the experi-

perceptual evaluation and measure walkability only ences of local citizens. It has become clear that addi-

as an “overall” quality of a certain neighborhood tional methods and tools for evaluation are needed

which can be considered as a rough evaluation. for the assessment of walkability as a location-based

SPACES focuses on blocks for auditing, but this human experience.

method requires separate audit forms for each block

making it difficult to manage for the surveyors on SOCIAL CONSTRUCTION OF WALKING

the field. EXPERIENCES: STRATEGIES AND TOOLS

The performance categories in the studies Motivated with the problems above, we have cre-

above can be briefly summarized as: the connectiv- ated multiple scenarios for enabling the analysis of

ity of path network, linkage with other transportation walkability and then combined and tested a suite

modes, land use patterns, safety (traffic/social), the of ICT tools (Figure 2). In this suite, open-source

quality of the path context, spatial definition and over- social content management platform serves as a

all explorability (Southworth, 2005). These may seem backbone with an advanced open-source database

to be computable using GIS data at a first glance; (PostgreSQL) which is enhanced by libraries such as

however, it is difficult to make a good estimation of JQuery, Openlayers, Heatmaps [5] and various mod-

the complex dimensions, especially the explorability. ules which are also distributed in an open-source

When it comes to GIS estimations of walkability, manner.

it is clear that the performance indicators are too In this paper, we will share a single scenario with

complicated to be solely estimated by data (Figure two alternative methods which aim at the collection

1). As an example, WalkScore [4] measures the num- of experiential information from the inhabitants of

ber of “errands” within walking distance of a specific a specific neighborhood. This is followed by serving

location, with scores ranging from 0 (car dependent) this information to decision makers and urban de-

to 100 (most walkable). By the WalkScore measure, signers in a structured, easy to understand format.

Crowdsourcing and Sensing - Volume 1 - Computation and Performance - eCAADe 31 | 425

Figure 2

A simplified figure describ-

ing the architecture of the

open-source social content

management platform.

Both of the methods M01and M02 make use of The first method (M01) follows the research tra-

heat maps (e.g. Figure 5) for analysis and evaluation. dition of Lynch (1961), a qualitative research meth-

Heat maps enable the dynamic visualization of three od focusing on exploring how people experience

dimensional data, in which two dimensions repre- walkability. It makes use of the open-source social

sent Cartesian coordinates and the third dimension content management platform introduced above.

is used for visualizing the intensity of walkability or In this method, an urban designer arranges several

a dimension of walkability as a datapoint in relative Lynch (1961) style walk-through interviews in the

comparison to the absolute maximum of the data- neighborhood with the inhabitants while making

set. notes and collecting visual information, which are

Using the datapoints, an alpha map is created entered on the platform both during and after the

using a radial gradient with 0.1 alpha as the maxi- study. The aim of this method is the exploration of

mum value which fades out to alpha=0. Then these the walkability concept, the extraction of its cultur-

values are converted to RGB. This method gives us ally bound dimensions and using these in a future

the flexibility to build a customized color shift from large-scale experiment (M02, introduced below).

alpha 255 to 0 and control the radius of the data The second method (M02) involves motivating

points. the inhabitants to get involved in the walkability

The intensity is shown as a color; red (hot) for evaluation; reflect their experiences and learn from

the maxima and blue (cold) for minima. This visu- their neighbors. An open-source social content

alization tool reduces the representation complexity management platform serves as the backbone, and

and allows the analysis of urban spaces in relation provides alternative interfaces for web and mobile

to its surroundings. As a result of the study, the find- browsers, enabling the input of ratings as well as

ings are transferred to the urban designers, planners output in the forms of maps and dashboards (Figure

and other public authorities in this easy to under- 3). This interface is currently under development.

stand format. Using the provided rating interfaces, the inhab-

426 | eCAADe 31 - Computation and Performance - Volume 1 - Crowdsourcing and Sensing

Figure 3 for analysis and evaluation. These maps enable the

The conceptual interface de- dynamic visualization of three dimensional data, in

sign of the mobile dashboard, which two dimensions represent Cartesian coordi-

currently under development nates and the third dimension is used for visualizing

and operational testing. the intensity of walkability or a dimension of walk-

ability as a datapoint in relative comparison to the

absolute maximum of the dataset. The intensity is

shown as a color; red (hot) for the maxima and blue

(cold) for minima. This visualization tool reduces the

representation complexity and allows the analysis of

urban spaces in relation to its surroundings. As a re-

sult of the study, the findings are transferred to the

urban designers, planners and other public authori-

ties in this easy to understand format.

Pilot Study

A pilot study (P01) was conducted in Brussels in

order to test the walkability analysis scenario intro-

duced in the former section as well as the prelimi-

nary examination the effectiveness the open-source

social content management platform and the heat

map visualization method.

This study utilized the M01 method, which can

be considered more suitable for exploratory pilot-

itants rate walkability of specific locations in their ing. The primary intention was to test the overall

surroundings. A significant advantage of this sys- concept and transfer what is learned from the P01

tem is the fact that users with mobile devices do not to a future large-scale experiment (M02). A second-

need to manually enter their location information. It ary aim was to extract and verify the various socio-

is automatically gathered from internal GPS of their spatial and sensory dimensions of walkability from

device and translated into places and addresses the viewpoints of the users to be used for testing in

through the geocoder module with their consent. future studies (examples are reviewed in the previous

For ease of use, only a limited number of experien- section) as they can be culturally bound.

tial aspects of walkability are entered through inter- With the aims and motivations above, an explor-

active sliders (Figure 3). atory research study was initiated with the contribu-

An important motivational aspect is the loca- tion of six participants who actively use this urban

tion-based delivery of the walkability ratings. When space on a daily basis. A specific triangular path

the platform is accessed by a mobile browser, the around Liedts Square in Brussels was chosen as a

system asks for a permission to use their location. If test zone. This area is one of the most controversial

inhabitants voluntarily turn on this service, they are and segregated places in the city, which happens to

continuously provided with the average ratings for include the North Station and an ethnic shopping

their actual location and will be motivated to reflect street.

their own experiences. Each participant was asked to walk around the

According to our scenario, both of the methods neighborhood and continuously express their opin-

M01and M02 make use of heat maps (Figure 5) ions on the walkability problems of the location. The

Crowdsourcing and Sensing - Volume 1 - Computation and Performance - eCAADe 31 | 427

Figure 4

Photos from the 2-hour

walk-along studies with the

participants, revealing prob-

lems related to various aspects

of walkability.

first author accompanied and interviewed each par- tremely unsafe in terms of traffic as well as unpleas-

ticipant during a two-hour walk-along, while mak- antly noisy. Especially in less visible areas, overspill

ing location-based notes and taking photos (Figure parking by the cars and motorcycles were reported

4). as a common negative factor limiting walkability. At

Following the M01 method, the collected infor- various locations, physical qualities and placement

mation was uploaded to the platform via: of the urban furniture, policy enforcement devices

• A mobile device / geolocated notes and pho- and signs were reported as extremely poor.

tos, during the walk, on location The traffic regulations and signs at the intersec-

• A desktop browser, after the walk, based on the tion points in Liedts Square (seen as a red spot on

notes top of the triangle in the heat map) were also indi-

After the participatory study, a joint heatmap cated as negative factors reducing the walkability in

was constructed using the walkability ratings of the this area.

six contributors (Figure 5). This heat map renders a In addition, the connection of the shopping

predefined gradient based on the intensity of a da- street to the North Station (seen next to the rail road

tapoint. The more negative points, the more it shifts on the map) was perceived as unsafe. The sidewalk

towards red. in front of various abandoned building sites and

Combining this map and the location-based wide monofunctional administrative buildings were

notes revealed various problematic areas (due to the also indicated as unwalkable due to their aesthetic

limited space in this paper, only significant findings are repulsiveness.

included). Besides the identification of problematic areas

According to the findings, the walkability of the in the pilot study area, by analyzing the location-

shopping street (red area on the map) was perceived based notes entered on the content management

as very poor due to low pedestrian flow, uncollected platform, it was possible to extract various interre-

trash, sidewalks occupied by the shops and perma- lated spatial qualities. These have been reported

nently parked trucks used as storage spaces by the by the participants as related to the walkability of

stores. In contrast, the number and variety of ameni- the neighborhood. Determining these locally situ-

ties and attraction points were seen as positive fac- ated qualities were important because these can be

tors which added to the sense of place, identity and used as predefined dimensions while testing meth-

explorability. od M02. We have grouped those under two main

Various intersection points were reported as ex- categories: experiential and environmental (Table 1).

428 | eCAADe 31 - Computation and Performance - Volume 1 - Crowdsourcing and Sensing

Figure 5

Testing the open-source

social content management

platform prototype and asso-

ciated libraries: the screenshot

from the web interface

including a heat map (on the

right) generated by the more

than 300 walkability problem

points (on the left).

There is a significant difference between the street and inclusion of trees and seating ele-

two categories: it is possible to identify quantifiable ments without blocking the pedestrian flow.

measures for the dimensions in the environmental • Designing a structure to facilitate temporary

category. On the other hand, the experiential di- use of abandoned sites as a market place.

mensions cannot be purely quantifiable. This obser- • Designing urban furniture resistant to public

vation leads to the conclusion that the environmen- violence.

tal aspects can be measured and represented with • Scalable seating places integrated into the fa-

and without the help of the inhabitants; but human cades of the buildings to facilitate the use of

contribution is mostly essential for the experiential the neighborhood as a recreational area.

evaluation. • Specially designed safe bike parking spaces in

Based on Table 1, it would not be wrong to claim front of the station to enable linkage to bike

that an experiential quality (such as the sense of transport.

place) may emerge as a result of the combination of • Redesign of the pedestrian crossings at four

other environmental and experiential qualities (such points.

as the physical layout, aesthetical appeal etc.). For • Adjustment of the traffic flow to prioritize pe-

instance, in the pilot study, some of the participants destrian use around the Liedts Square and dis-

have connected the sense of place, identity and ex- encouragement of parking on the square.

plorability with a number and variety of amenities • Redesign of the bridge at the end of the shop-

and attraction points. ping street to enable a better connection to

A significant benefit of the walkability evalua- the city network and creating a more pleasur-

tion was the use of results to develop possible solu- able passage by designing small retail shops

tions to design and planning problems. For instance, under it.

as a result of our pilot study, we were able to come The ideas above are currently being developed

up with a significant number of design ideas: as a concrete architectural project which will be pre-

• Limited pedestrianization of the shopping sented during the conference.

Crowdsourcing and Sensing - Volume 1 - Computation and Performance - eCAADe 31 | 429

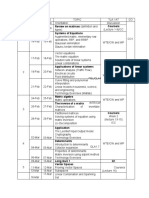

Qualities Extracted from the Pilot Study Table 1

Experiential - Aesthetical appeal Dimensions of walkability:

- Sense of place spatial qualities extracted

- Sense of identity from the pilot study (other

- Special and Somatic Sensory Experiences (odor, noise, wind, vibration, temperature, qualities reported in the litera-

kinesthetic, balance etc.) ture are not included).

- Recreational capacity

- Explorability

- Perception of safety

Environmental - Number and variety of amenities and attraction points

- Linkage to public/bike transport

- Physical layout (block length, intersection density, street width etc.)

- Land use mixity

- Linkage to other parts of the city

- The physical qualities of the sidewalks (width, height, surface etc.)

- The physical qualities and placement of the urban furniture and policy

enforcement tools (benches, parking meters, signs etc.)

- Level of pollution (collection of trash, air quality etc.)

- Number of pedestrians on the street

- Density of the car traffic

- Weather conditions

- Natural elements

CONCLUSIONS AND FUTURE DIRECTIONS ment and planning policies. From these we have

In this study, we have discussed the concept of walk- learned that walkability may serve as a fruitful con-

ability as a performance indicator and introduced versation framework and a participatory research

various strategies and tools for the analysis of walk- concept. Several controversial topics emerged as a

ability. result; among those were: loitering, graffiti and the

We have provided a pilot study demonstrating governmental regulation of the retails. These were

how the location-based evaluations of walkability seen as positive by some of the participants and dis-

can be dynamically combined and visualized using ruptive by others.

heat maps which lead to the extraction of the prob- These findings also motivate the new study

lematic areas. with the use of the M02 method: involving a higher

From the pilot study we were also able to derive number of inhabitants which can be treated as a

various experiential and environmental spatial qual- representative sample size. Using their reports and

ities as dimensions of walkability. These are planned the heat map, it will be possible to extract the most

to be used as a resource for our next study, in which common problems, visualize and extract the priori-

we will follow the M02 method and ask the inhab- ties of the locals.

itants to categorize their walkability experience ac- Considering the technological aspects, we

cording to the extracted qualities and observe the found several advantages of the proposed open-

relations between. source social content management platform. It was

During the pilot study, the participants made possible to generate heat maps from the collected

various suggestions at different scales, not only on geolocated ratings (Figure 5). We visualized these

the designerly aspects but also on public manage- in various forms and mashed them up with external

430 | eCAADe 31 - Computation and Performance - Volume 1 - Crowdsourcing and Sensing

data resources. Then they were exported in various As a final remark, we would like to conclude that

GIS formats (KML, GeoRSS). walkability is a useful performance indicator of ur-

In contrast, various challenges of the introduced ban spaces because it places the human dimension

open-source social content management platform at the center of urban design. Walkability research

were observed during the pilot study: focuses on the experiential and environmental qual-

• There were precision problems due to the mo- ities of urban spaces but also relates to many other

bile location sensing methods. qualities. For instance, in the case of safety it was

• Using mobile devices in unwalkable places was evident that economic and social contexts play a

difficult and unsafe in certain conditions such significant role. In this sense, walkability should not

as busy sidewalks or dangerous crossings. be interpreted as a sole consequence of the urban

• The gradient visualization of the heat maps design and planning decisions. It also includes vari-

needed to be calibrated according to the ous economic and social dimensions which can pos-

neighborhood size and various zoom levels. sibly inspire new design solutions from alternative

However, despite these fallbacks, it is important perspectives; and these should definitely be taken

to conclude that the introduced tools and method into account.

(M01) enabled us to extract and diagnose a signifi-

cant number of problems. In addition to the findings REFERENCES

above, by using the heat maps in combination with Cortright, J 2007, ‘Walking the walk: How walkability raises

the walk-along experiences, we were able to deve- home values in US cities’, CEOs for Cities, Impresa Inc.

lop ideas for solutions to design and planning prob- Frank, L, Schmid, T, Sallis, J, Chapman, J, Saelens, B, 2005,

lems which may provide measurable benefits to the ‘Linking objectively measured physical activity with

inhabitants. For instance, we have suggested limited objectively measured urban form’, American Journal of

pedestrianization of the shopping street with a high Preventive Medicine, Vol.28, pp.117-125.

number of negative walkability ratings (red on the Gehl, J 2010, Cities for People, Island Press, London.

heat map on Figure 5). We recommended the rede- Jacobs, J 1961, Death and Life of Great American Cities, Ran-

sign of the pedestrian crossings at two points, again dom House, New York.

highlighted as red on the map and referenced dur- Johnson, D 2002, ‘Origin of the Neighborhood Unit’, Plan-

ing the interviews by all of the participants. ning Perspectives, Vol.17, pp.227-245.

For similar future studies, we would like to intro- Kerr, J, Rosenberg, D, Frank, L 2012, ‘The Role of the Built

duce a number of recommendations: Environment in Healthy Aging’, Journal of Planning Lit-

• In order to guarantee the sustainability of this erature Vol.27(4) pp.43-6.

platform, on-site motivational activities and in- Lynch, K, 1960, The Image of the City, MIT Press, Cambridge.

teractive public displays can be useful. Pak, B., Verbeke, J. 2012, ‘Design studio 2.0: augmenting

• Utilizing the time data from the content man- reflective architectural design learning’, Journal of In-

agement platform and enabling time-based formation Technology in Construction (17), pp.502-519.

visualizations using a time slider. Patricios, N 2002, ‘Urban Design Principles of the Original

• Providing a public map of walkability may Neighborhood Concepts’, Urban Morphology, 6(1),

make the neighborhood open to the abuse of 2002, pp. 21-32.

the real estate market and therefore promoting Perry, C. A. 1929, The neighborhood unit, Monograph 1 in

gentrification. Therefore, access limitations and Committee on Regional Plan of New York and its Envi-

additional measures should be introduced. rons, Neighbourhood and community planning. Re-

• Security measures should be taken to block the gional survey VII, Committee on Regional Plan of New

invasion of privacy of the users and their identi- York and its Environs, New York, pp. 20-141

ties should be protected. Pikora TJ, Corti B, Knuiman MW, Bull FC, Jamrozik K, Dono-

Crowdsourcing and Sensing - Volume 1 - Computation and Performance - eCAADe 31 | 431

van RJ 2006, ‘Neighborhood environmental factors of Urban Planning and Development 131(4), pp.246-257.

correlated with walking near home: Using SPACES’,

Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, Vol.38, [1] tinyurl.com/thefiveminutewalk

pp.708–714. [2] www.cnu.org/sites/www.cnu.org/files/charter_english1.

Saelens, BE, Sallis, JF, Black, J, Chen, D, 2003, ‘Neighbor- pdf

hood-based differences in physical activity’, American [3] www.usgbc.org/ShowFile.aspx?DocumentID=6406

Journal of Public Health, Vol.93, pp. 1552-1558. [4] www.walkscore.com

Southworth M, 2005, ‘Designing the walkable city’, Journal [5] www.patrick-wied.at

432 | eCAADe 31 - Computation and Performance - Volume 1 - Crowdsourcing and Sensing

You might also like

- Title: Path Walkability Assessment Framework Based On Decision Making Analysis of Pedestrian Travelers Retail WalkingDocument13 pagesTitle: Path Walkability Assessment Framework Based On Decision Making Analysis of Pedestrian Travelers Retail WalkingThanes RawNo ratings yet

- Planning and Design Support Tools For Walkability: A Guide For Urban AnalystsDocument18 pagesPlanning and Design Support Tools For Walkability: A Guide For Urban Analystspranshu speedyNo ratings yet

- Pedestrian Mobility Environments Defined and EvaluatedDocument16 pagesPedestrian Mobility Environments Defined and EvaluatedOctávio AlmeidaNo ratings yet

- RRL 1Document19 pagesRRL 1Xyra Mae PugongNo ratings yet

- Pedestrianization Through TacticDocument13 pagesPedestrianization Through TacticIEREKPRESSNo ratings yet

- Rebuilding Living CityDocument8 pagesRebuilding Living Cityraja vijjayNo ratings yet

- Design's Factors Influencing Social Interaction in Public SquaresDocument9 pagesDesign's Factors Influencing Social Interaction in Public SquaresMemoonaNo ratings yet

- Modeling Pedestrian FlowsDocument18 pagesModeling Pedestrian FlowsmateovillamilvalenciaNo ratings yet

- Landmark Mak AlesiDocument22 pagesLandmark Mak AlesiLaila Abd AlazizNo ratings yet

- JPAH 15a Ewing 0Document17 pagesJPAH 15a Ewing 0Rahul VinodanNo ratings yet

- Journal of Transport Geography 87 (2020) 102778Document16 pagesJournal of Transport Geography 87 (2020) 102778Ram TulasiNo ratings yet

- Integrating Urban Knowledge for Pedestrian Behavior AnalysisDocument9 pagesIntegrating Urban Knowledge for Pedestrian Behavior AnalysisognenmarinaNo ratings yet

- Ciudad Habitable Un Acercamiento A La Peatonalización A Través Del Urbanismo Táctico PDFDocument9 pagesCiudad Habitable Un Acercamiento A La Peatonalización A Través Del Urbanismo Táctico PDFanderson scNo ratings yet

- Design's Factors Influencing Social Interaction in Public SquaresDocument9 pagesDesign's Factors Influencing Social Interaction in Public SquaresAditya PatilNo ratings yet

- Shared Space: A New Approach to Street DesignDocument21 pagesShared Space: A New Approach to Street DesignXimenaNo ratings yet

- BALASUBRAMANIAN, S. Et Al. Aesthetics of Urban Commercial Streets From The Perspective of Cognitive Memory and User Behavior in Urban EnvironmentsDocument14 pagesBALASUBRAMANIAN, S. Et Al. Aesthetics of Urban Commercial Streets From The Perspective of Cognitive Memory and User Behavior in Urban EnvironmentsLyvia FialhoNo ratings yet

- Pedestrian Perceptions of Safety on Urban StreetsDocument13 pagesPedestrian Perceptions of Safety on Urban StreetsLanlan WeiNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S2210670721009197 MainDocument16 pages1 s2.0 S2210670721009197 MainStephanie MadridNo ratings yet

- City Form and Well-Being: What Makes London Neighborhoods Good Places To Live?Document4 pagesCity Form and Well-Being: What Makes London Neighborhoods Good Places To Live?Ade JonruNo ratings yet

- Evaluating Spatial Behavior in The Urban Public Space of Kadıköy SquareDocument18 pagesEvaluating Spatial Behavior in The Urban Public Space of Kadıköy SquareJohn Xavier QuilanticNo ratings yet

- Towards_A_Comprehensive_Model_of_Placemaking_StratDocument61 pagesTowards_A_Comprehensive_Model_of_Placemaking_StratAndrei Nicole De VeraNo ratings yet

- Status ReportDocument28 pagesStatus ReportNIDHI SINGHNo ratings yet

- Sustainability 13 03648Document18 pagesSustainability 13 03648Melinda RupianiNo ratings yet

- Schlossberg GIS Audits 1Document7 pagesSchlossberg GIS Audits 1Abdullah MunifNo ratings yet

- Campisi 2020Document16 pagesCampisi 2020DrOmar ArchNo ratings yet

- Journal of Urban Design Measuring Unmeasurable QualitiesDocument21 pagesJournal of Urban Design Measuring Unmeasurable QualitiesJose Francisco RomeroNo ratings yet

- In Uence of Street Design Characteristics On Walkability: Case Studies of Two Neighborhoods in ErbilDocument13 pagesIn Uence of Street Design Characteristics On Walkability: Case Studies of Two Neighborhoods in ErbilAnuja JadhavNo ratings yet

- Bridging The Gap Between Theory and Practice in The Urban Design Process: Towards A Multi-Disciplinary ApproachDocument21 pagesBridging The Gap Between Theory and Practice in The Urban Design Process: Towards A Multi-Disciplinary ApproachIEREKPRESSNo ratings yet

- Talavera, 2012Document16 pagesTalavera, 2012FábioZampieriNo ratings yet

- Critical analysis of smart urbanism discourses and implicationsDocument12 pagesCritical analysis of smart urbanism discourses and implicationsdiana_vonnakNo ratings yet

- Sustainability FinalDocument66 pagesSustainability FinalAndrei Nicole De VeraNo ratings yet

- Cities: Kostas MouratidisDocument12 pagesCities: Kostas MouratidisTarek Mohamed Tarek FouadNo ratings yet

- Ats-1391-Van Der VlugtDocument33 pagesAts-1391-Van Der VlugtScintilla SelenophileNo ratings yet

- Improving Pedestrian Accessibility To Public Space Through Space Syntax Analysis PDFDocument16 pagesImproving Pedestrian Accessibility To Public Space Through Space Syntax Analysis PDFFikenia Miftah ANo ratings yet

- BRE533 Urban Planning and Urban Design Take Home Assignment Part 2 (WANG Tat 19012107G)Document6 pagesBRE533 Urban Planning and Urban Design Take Home Assignment Part 2 (WANG Tat 19012107G)HugoNo ratings yet

- Walkable Streets Pedestrian Behavior Perceptions and AttitudesDocument30 pagesWalkable Streets Pedestrian Behavior Perceptions and AttitudesYuet Y ChengNo ratings yet

- Ped Built Enviro SLCDocument9 pagesPed Built Enviro SLCElleNo ratings yet

- Accessibility and Street Network Characteristics oDocument19 pagesAccessibility and Street Network Characteristics oRGARCIANo ratings yet

- Literature QuizDocument2 pagesLiterature Quizcsgo.smurfen00No ratings yet

- Sustainable City Plan Based On Planning Algorithm 2011 Procedia Social AnDocument9 pagesSustainable City Plan Based On Planning Algorithm 2011 Procedia Social AnPaola Giraldo MontoyaNo ratings yet

- Model For Assessment of Public Space Quality in ToDocument29 pagesModel For Assessment of Public Space Quality in ToJOHAINAH IBRAHIMNo ratings yet

- SustainabilityDocument16 pagesSustainabilityRukhsana BadarNo ratings yet

- Proximal Cities: Does Walkability Drive Informal Settlements?Document20 pagesProximal Cities: Does Walkability Drive Informal Settlements?Tap TouchNo ratings yet

- Annotated BibliographyDocument8 pagesAnnotated BibliographyANGELICA MAE HOFILEÑANo ratings yet

- Exploring The Cultural Context and Public Realm in Urban SpacesDocument36 pagesExploring The Cultural Context and Public Realm in Urban SpacesAdrish NaskarNo ratings yet

- Ioegc 10 101 10135Document10 pagesIoegc 10 101 10135yaraahmadsayed1999No ratings yet

- Enhancing Urban Design Research Through Virtual Reality Semi-ExperimentsDocument39 pagesEnhancing Urban Design Research Through Virtual Reality Semi-ExperimentsPARVATHY R S 170564No ratings yet

- Sustainability 12 10116 v2Document21 pagesSustainability 12 10116 v2Tushar ShakyaNo ratings yet

- Potential and Limitations of Social Media Analysis for Urban StudiesDocument15 pagesPotential and Limitations of Social Media Analysis for Urban StudiesLuca SimeoneNo ratings yet

- Remotesensing 13 03363 With CoverDocument25 pagesRemotesensing 13 03363 With Coverviludhugal1996No ratings yet

- Using Participatory Mapping To Explore Participation in Three CommunitiesDocument16 pagesUsing Participatory Mapping To Explore Participation in Three CommunitiesNCVO100% (1)

- Sustainability 13 06825 v2Document22 pagesSustainability 13 06825 v2kutambaruNo ratings yet

- Sustainability 11 04356Document19 pagesSustainability 11 04356Andrew 28No ratings yet

- Space_Syntax_Expression_of_Science_on_User_Flows_iDocument15 pagesSpace_Syntax_Expression_of_Science_on_User_Flows_inasibeh tabriziNo ratings yet

- Tim Stonor - Re-Making PlacesDocument6 pagesTim Stonor - Re-Making PlacesMartin LeeNo ratings yet

- A Multi Scale Approach Mapping Spatial Equality of Urban Public Fa - 2023 - HeliDocument18 pagesA Multi Scale Approach Mapping Spatial Equality of Urban Public Fa - 2023 - Heliengmxc12No ratings yet

- Urban Design-1: As Land Use, Population, Transportation, Natural Systems, and TopographyDocument18 pagesUrban Design-1: As Land Use, Population, Transportation, Natural Systems, and TopographymilonNo ratings yet

- RP - 12 04 2021 - Final - RahulDocument23 pagesRP - 12 04 2021 - Final - RahulBATMANNo ratings yet

- Overview of Urban Quality IndicatorsDocument9 pagesOverview of Urban Quality IndicatorsYolandita AristawatiNo ratings yet

- 08 Social Och Barnkonsekvensanalys Backaplan (2018)Document20 pages08 Social Och Barnkonsekvensanalys Backaplan (2018)sevanscesNo ratings yet

- Shopping MattersDocument39 pagesShopping MatterssevanscesNo ratings yet

- 16 - Integrating A Multi-Objective Optimization Framework Into A Structural Design SoftwareDocument10 pages16 - Integrating A Multi-Objective Optimization Framework Into A Structural Design SoftwaresevanscesNo ratings yet

- March Digital Arch TectonicsDocument2 pagesMarch Digital Arch TectonicssevanscesNo ratings yet

- 05 - Algorithm-Aided Building Information Modeling Connecting Algorithm-Aided Design and Object-Oriented DesignDocument176 pages05 - Algorithm-Aided Building Information Modeling Connecting Algorithm-Aided Design and Object-Oriented Designsevansces100% (2)

- Revit® Interiors and FinishesDocument31 pagesRevit® Interiors and FinishessevanscesNo ratings yet

- Grasshopper Primer Second Edition 090323Document163 pagesGrasshopper Primer Second Edition 090323landleyvvv100% (5)

- CEPTcasestudy PDFDocument2 pagesCEPTcasestudy PDFsevanscesNo ratings yet

- Architectural Color Line Weight (MM) DescriptionDocument10 pagesArchitectural Color Line Weight (MM) DescriptionBagusBudiNo ratings yet

- Bimstore Bible - Revit Family Creation StandardsDocument44 pagesBimstore Bible - Revit Family Creation StandardsPref181180% (5)

- Image Stitching Using Matlab PDFDocument5 pagesImage Stitching Using Matlab PDFnikil chinnaNo ratings yet

- What is an electrolyser and how does it generate hydrogenDocument1 pageWhat is an electrolyser and how does it generate hydrogenbhaidadaNo ratings yet

- .625 DIA & HEX: Outline/Installation Drawing, MODEL 3100D24Document2 pages.625 DIA & HEX: Outline/Installation Drawing, MODEL 3100D24info5280No ratings yet

- E3tutorial Exercises UsDocument41 pagesE3tutorial Exercises UsKarthik NNo ratings yet

- Release 445 Driver For Windows, Version 445.87Document39 pagesRelease 445 Driver For Windows, Version 445.87Abid ArifNo ratings yet

- Solsmart 1250 - 1450Document16 pagesSolsmart 1250 - 1450Mohan RajNo ratings yet

- 3 Pureballast 3.2/ Pureballast 3.2 Compact Flex 3Document11 pages3 Pureballast 3.2/ Pureballast 3.2 Compact Flex 3TamNo ratings yet

- Review On Matrices (Definition and Coursera Systems of EquationsDocument2 pagesReview On Matrices (Definition and Coursera Systems of EquationsAlwin Palma jrNo ratings yet

- PIC hardware quick reference guide under 40 charactersDocument3 pagesPIC hardware quick reference guide under 40 charactersJojonNo ratings yet

- MEITRACK - MVT600-User-Guide-V2.0 Sensor de Combustible ResistenciaDocument22 pagesMEITRACK - MVT600-User-Guide-V2.0 Sensor de Combustible ResistenciaManuel Flores CorderoNo ratings yet

- Safety Logic For Machines and Systems - Easysafety ES4P - Safety Relay ESR5Document16 pagesSafety Logic For Machines and Systems - Easysafety ES4P - Safety Relay ESR5geocaustasNo ratings yet

- Simplicity SE Controls - 5127914-UTG-A-0515Document61 pagesSimplicity SE Controls - 5127914-UTG-A-0515Mario LozanoNo ratings yet

- 7 Steps Prevent Communication GapsDocument5 pages7 Steps Prevent Communication GapssmartisaacNo ratings yet

- Nagman Economy Pressure Calibrator Spec SheetDocument2 pagesNagman Economy Pressure Calibrator Spec SheettruongNo ratings yet

- 2018 Google Dorks MasterDocument84 pages2018 Google Dorks MasterhackedNo ratings yet

- Merge PDF Files Online. Free Service To Merge PDF - IlovepdfDocument3 pagesMerge PDF Files Online. Free Service To Merge PDF - IlovepdfAMIR RAZANo ratings yet

- The Digital Butterfly EffectDocument7 pagesThe Digital Butterfly EffectAnonymous PXX1LANo ratings yet

- Skills-Based Assessment (Version A) : TopologyDocument5 pagesSkills-Based Assessment (Version A) : TopologyYagui100% (1)

- Performance Report SummaryDocument13 pagesPerformance Report SummaryHariprasad Reddy GNo ratings yet

- HEAVY DUTY CATALOG - AP TruckDocument81 pagesHEAVY DUTY CATALOG - AP TruckCarlos Andres PachecoNo ratings yet

- Yealink Hybrid-mode Feature Compatible with AudioCodes SBC V15.3Document13 pagesYealink Hybrid-mode Feature Compatible with AudioCodes SBC V15.3jtzondoNo ratings yet

- B2B Streamlined Bill Sample - Phone Bill Template FormDocument9 pagesB2B Streamlined Bill Sample - Phone Bill Template FormBrendon DrewNo ratings yet

- w220 S-Class Encyclopedia Jan 2014Document44 pagesw220 S-Class Encyclopedia Jan 2014Aziz Al-Qadri Wal Chisti100% (2)

- Scribd For IphoneDocument3 pagesScribd For IphoneScribd50% (2)

- Quantitative Aptitude by SARVESH VERMADocument809 pagesQuantitative Aptitude by SARVESH VERMARajiv Ranjan0% (1)

- Qns Bank For Final Exam FilteredDocument104 pagesQns Bank For Final Exam FilteredPhuong PhamNo ratings yet

- Shell Mysella S6 N 40Document2 pagesShell Mysella S6 N 40Muhammad SaputraNo ratings yet

- Growing fascination with technology and data scienceDocument1 pageGrowing fascination with technology and data scienceVipul KotiNo ratings yet

- Proffessional Security Installer - January 2024Document54 pagesProffessional Security Installer - January 2024clubeautomovelviseuNo ratings yet

- History of Computer: Basic Computing Periods: Week 3 Living in The IT Era Maria Michelle VinegasDocument41 pagesHistory of Computer: Basic Computing Periods: Week 3 Living in The IT Era Maria Michelle VinegasMary Ianne Therese GumabongNo ratings yet