Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Australia - Transfer Pricing - Dispute Resolution - IBFD

Uploaded by

marialaura.rojasOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Australia - Transfer Pricing - Dispute Resolution - IBFD

Uploaded by

marialaura.rojasCopyright:

Available Formats

Australia - Transfer Pricing & Dispute Resolution - Country Tax Guides (Last Reviewed: 31 May 2023)

Transfer Pricing & Dispute Resolution

Australia

Author

Stewart Grieve[*]

Partner, Johnson Winter & Slattery, Melbourne, Australia

Based on the original chapter written by Reynah Tang.

IBFD Tax Technical Editor

Zachary Somers

Latest Information

This chapter is based on information available up to 31 May 2023. Please find below the main changes made to this

chapter up to that date:

Federal government has extended the funding of the Tax Avoidance Taskforce until 30 June 2026.

The OECD released 2021 MAP statistics of Australia.

The ATO released 2021/2022 APA statistics of Australia.

1. Introduction[1]

1.1. Overview of TP documentation procedure

See Australia – Transfer Pricing section 13.

1.2. Overview of local dispute procedure

The ATO analyses the information that is disclosed in tax returns (including the International Dealings Schedule),[2] together with

other information it collects, to determine which taxpayers to review and, potentially, audit. It is generally only following review and

audit that the Commissioner of Taxation (Commissioner) will issue an assessment for additional tax, penalties and interest. The

audit process is discussed in more detail in section 2.3.

To the extent that transfer pricing adjustments are made by the Commissioner, a taxpayer has an administrative right to object

to any assessment raised.[3] Following objection, a process of internal review is conducted by an “independent” officer within the

ATO. It is only following failure to obtain satisfactory resolution of an objection that a taxpayer has the right to seek review of the

decision by the Administrative Appeals Tribunal (AAT)[4] or appeal to the Federal Court of Australia (Federal Court). The dispute

process is discussed in more detail in section 3.2.

*. Stewart Grieve is a Partner at Johnson Winter & Slattery in Melbourne, Australia. The assistance of Don Spirason and Julian Wan in preparing the latest update is

gratefully acknowledged. The views expressed in this chapter are the authors’ personal views (and do not necessarily represent the views of their organization).

1. This chapter focuses on the administration of Australia’s transfer pricing laws. It does not specifically address the administration of Australia’s diverted profits

tax (DPT) or Multinational Anti-Avoidance Law (MAAL). It should be noted that the DPT and the MAAL may be raised by the ATO in conjunction with a transfer

pricing dispute but they are separate and distinct from Australia’s transfer pricing laws.

2. ATO, International Dealings Schedule, available at https://www.ato.gov.au/Business/International-tax-for-business/In-detail/Transfer-pricing/International-

transfer-pricing---introduction-to-concepts-and-risk-assessment/?anchor=IDS#IDS (accessed 20 June 2023).

3. Part IVC, Div. 3, Taxation Administration Act 1953 (TAA 1953).

4. In Dec. 2022, the federal government announced that the AAT will be abolished and replaced with a new federal administrative review body. The AAT will

continue to operate until this reform takes effect.

S. Grieve, Australia - Transfer Pricing & Dispute Resolution, Country Tax Guides IBFD (accessed 2 August 2023). 1

© Copyright 2023 IBFD: No part of this information may be reproduced or distributed without permission of IBFD.

Disclaimer: IBFD will not be liable for any damages arising from the use of this information.

Exported / Printed on 22 Nov. 2023 by Maria.L.Rojas@ar.ey.com.

Australia - Transfer Pricing & Dispute Resolution - Country Tax Guides (Last Reviewed: 31 May 2023)

1.2.1. Availability of international procedures and relief from double taxation

To the extent that transfer pricing adjustments made by the ATO (or its foreign counterparts) may lead to double taxation, Australia

has mutual agreement procedures (MAPs) in place to resolve any disputes under the relevant tax treaties, which are discussed in

section 4.2.

Multinational enterprises also have the option of seeking to avoid the risk of double taxation in advance by entering into a (bilateral)

advance pricing arrangement (APA) with the ATO and the tax authority in the foreign jurisdiction. This process – including the

use of unilateral APAs – is addressed in section 5.2.4. and is performed by the “competent authority” within the ATO (see section

1.2.2.2.).

1.2.2. Tax authorities

1.2.2.1. Organizational structure with relevant areas of jurisdiction

The ATO is organized into a number of different groups and business lines. The ATO’s Client Engagement Group includes a

number of business lines broadly delineated by type of taxpayer. There is no specific transfer pricing group or business line

identified within the ATO’s Client Engagement Group. However, the Client Engagement Group includes Public Groups and

International business lines which, by virtue of the type of taxpayers they are responsible for, commonly deal with transfer pricing

matters.[5]

In 2016, the government established a Tax Avoidance Taskforce to conduct operations in high-risk sectors. The Tax Avoidance

Taskforce has received significant government funding which was recently extended until 30 June 2026. The ATO claims that

since its inception, Taskforce activity has helped generate AUD 17.2 billion in tax liabilities, leading to an additional AUD 9.7 billion

in cash collections.[6] A number of significant tax dispute settlements have also been credited to the Tax Avoidance Taskforce.[7]

1.2.2.2. Other relevant players

There are a number of other roles within the ATO as well as other government institutions that may be relevant to a transfer pricing

matter.

The “competent authority” under Australia’s tax treaties (who is responsible for negotiating MAPs and APAs) is a number of

specified officers of the ATO.

As indicated in section 3.2., objections against assessments that are raised are considered by a different officer within the ATO. If

the objection is disallowed, the taxpayer can apply for review of the objection decision by the AAT or appeal of the decision to the

Federal Court, both of which are independent of the ATO.

1.2.2.3. Programmes to ensure consistent application of TP policies and penalties

The Commissioner has issued various guidelines (e.g. in the form of rulings, practice statements and practical compliance

guidelines) [8] which are designed to guide ATO officers in the administration of transfer pricing matters.

1.2.2.4. Downward TP adjustments procedure

Under Australia’s current transfer pricing provisions in subdivision 815-B of the Income Tax Assessment Act (ITAA 97), primary

adjustments can only be made to increase taxable income, reduce tax losses, reduce tax offsets or increase withholding

tax. However, if a determination is made to adjust for a transfer pricing benefit, the Commissioner is empowered to make a

“consequential adjustment” for any entity that is disadvantaged as a result of the arm’s length conditions operating rather than the

actual conditions.[9]

5. ATO, Organisational Chart, available at https://www.ato.gov.au/uploadedFiles/Content/CR/downloads/n75148_ATO_organisational_structure.pdf (accessed 20

June 2023).

6. ATO, Tax Avoidance Taskforce extended and expanded (last modified 21 Nov. 2022), available at https://www.ato.gov.au/Business/Business-bulletins-

newsroom/Tax-avoidance/Tax-Avoidance-Taskforce-extended-and-expanded/ (accessed 13 June 2023).

7. Including a USD 381.7 settlement with ResMed in October 2021 (see ATO, ATO welcomes announcement of settlement of tax dispute, available at https://

www.ato.gov.au/Media-centre/Media-releases/ATO-welcomes-announcement-of-settlement-of-tax-dispute/ (accessed 20 June 2023); and the approximately

AUD 1 billion settlement with Rio Tinto in July 2022, one of the largest settlements in Australia’s tax history, see ATO, ATO secures settlement of marketing hub

tax dispute, available at https://www.ato.gov.au/Media-centre/Media-releases/ATO-secures-settlement-of-marketing-hub-tax-dispute/ (accessed 20 June 2023).

8. See e.g. ATO, Practice Statement Law Administration (PS LA) 2015/3, available at https://www.ato.gov.au/law/view/print?DocID=PSR%2FPS20153%2FNAT

%2FATO%2F00001&PiT=99991231235958&Life=20150226000001999912312359 (accessed 20 June 2023).

9. Sec. 815-145 ITAA 97.

S. Grieve, Australia - Transfer Pricing & Dispute Resolution, Country Tax Guides IBFD (accessed 2 August 2023). 2

© Copyright 2023 IBFD: No part of this information may be reproduced or distributed without permission of IBFD.

Disclaimer: IBFD will not be liable for any damages arising from the use of this information.

Exported / Printed on 22 Nov. 2023 by Maria.L.Rojas@ar.ey.com.

Australia - Transfer Pricing & Dispute Resolution - Country Tax Guides (Last Reviewed: 31 May 2023)

1.2.2.5. Contact information

Australian Competent Authority Transfer pricing gatekeeper

APA/MAP Program Management Unit internationalsgatekeeper@ato.gov.au

Public Groups and International

Australian Taxation Office

GPO Box 9977

Brisbane QLD 4001

1.2.2.6. Comment on profile and aggressiveness

The ATO has been active in making its views on transfer pricing known to the taxpaying community leading to a “somewhat

unbalanced engagement, in which the emphasis has often been on the economic analysis at the expense of the legal

fundamentals”.[10] The ATO seeks to influence taxpayer behaviour through its various publications. The ATO is also very active

in the media (relative to Australia’s size). The ATO published more than 20 rulings, determinations and practice statements, as

well as other guides and Internet resources, in relation to transfer pricing under the former transfer pricing regime (division 13

of the ITAA 36) and has been producing a range of tax rulings, practice statements and practical compliance guidelines on the

current regime in subdivisions 815-B to D of the ITAA 97. By and large, it appears that taxpayers do have regard for the ATO’s

guidance with a view to minimizing the prospect of review, audit and dispute – for example, in relation to marketing hubs, the

ATO estimated that, following the publication of Practical Compliance Guideline (PCG) 2017/1,[11] more than 50% of exports from

Australia associated with marketing hubs fell into the “safe zones” set out in that PCG.[12] At the time that BHP settled its long

running dispute with the ATO over BHP’s marketing hub, BHP expressly mentioned in its press release to the Australian stock

exchange that as part of the settlement, the ownership of its marketing hub would be held wholly under the Australian side of

BHP’s dual listed company structure and its marketing hub operations would be within the “low risk” or “green zone” for offshore

marketing hubs in accordance with PCG 2017/1.[13]

2. Audit

2.1. Historical background

The ATO first established an International Tax Division in 1993 in order to have a better focus, as an organization, on

globalization.[14] Over time, the ATO has continued to build and refine its approach to the review and audit of transfer pricing

issues.

The frequency with which a taxpayer is engaged by the ATO depends on which “client category” the taxpayer falls into.[15] For

example, taxpayers in the “Top 100” justified trust program receive ongoing one-to-one tailored engagement. The ATO offers

three “engagement experiences”, described as “partnering”, “encouraging” and “influencing”. The approach which the ATO

applies is based on a point-in-time assessment of the taxpayer’s transparency in terms of engagement with the ATO, choices and

10. D. Hearder, New Transfer Pricing Legislation, 18 Asia-Pac. Tax Bull. 5, p. 372 (2012), Journal Articles & Opinion Pieces IBFD. In this regard,

it is noted that the ATO issued its first tax ruling on transfer pricing in 1992, Taxation Ruling (TR) 92/11, Income Tax: application of the

Division 13 transfer pricing provisions to loan arrangements and credit balances (1 Oct. 1992) available at https://www.ato.gov.au/law/view/

document?src=hs&pit=99991231235958&arc=false&start=1&pageSize=10&total=16&num=5&docid=TXR%2FTR9211%2FNAT%2FATO

%2F00001&dc=false&stype=find&tm=phrase-basic-TR%2092%2F11 (accessed 20 June 2023). This followed a recommendation of the House of

Representatives Standing Committee on Finance and Public Administration (see recommendation (5) in Shifting the tax burden? Interim report on an Auditor-

General’s efficiency audit on the Australian Taxation Office – International profit shifting, para. 3.3.7 (Interim Martin Committee Report) (AGPS, 1988).

11. ATO, Practical Compliance Guideline (PCG) 2017/1, available at https://www.ato.gov.au/law/view/pdf/cog/pcg2017-001.pdf (accessed 20 June 2023).

12. ATO, ATO Submission – Inquiry into Australia’s oil and gas reserves, 8 Nov. 2019, available at https://www.aph.gov.au/Parliamentary_Business/Committees/

Senate/Economics/Australiasoilandgas/Submissions (accessed 20 June 2023).

13. BHP, BHP Settles longstanding transfer pricing dispute, News Release (19 Nov. 2018), available at https://www.asx.com.au/asxpdf/20181119/

pdf/440f9kqqdnxfyh.pdf (accessed 20 June 2023).

14. J. Killaly, Transfer Pricing – Compliance Issues and Insights in the Context of Global Profit Allocation, presentation to Transnational Crime Conference, p. 2 (9-10

Mar. 2000).

15. The ATO uses the Action Differentiation Framework (ADF) to determine how it engages with public and multinational business taxpayers. Under the ADF,

taxpayers will be placed into one of four client categories: (i) “Top 100” for market leaders or businesses with more than AUD 5 billion total business income;

(ii) “Top 1,000” for businesses with more than AUD 250 million total business income; (iii) “Medium” for businesses with between AUD 10 million and AUD 250

million total business income; and (iv) “Emerging” for businesses with less than AUD 10 million total business income; ATO, Action Differentiation Framework,

available at https://www.ato.gov.au/business/large-business/action-differentiation-framework/ (accessed 20 June 2023). For privately owned groups, the ATO

uses the Risk Differentiation Framework for private groups (available at https://www.ato.gov.au/Business/Privately-owned-and-wealthy-groups/What-you-should-

know/Transparency/How-we-assess-risk/ (accessed 20 June 2023)); and Tax performance programs for privately owned and wealthy groups (available at https://

www.ato.gov.au/Business/Privately-owned-and-wealthy-groups/What-you-should-know/Tax-performance-programs-for-private-groups/ (accessed 20 June

2023)).

S. Grieve, Australia - Transfer Pricing & Dispute Resolution, Country Tax Guides IBFD (accessed 2 August 2023). 3

© Copyright 2023 IBFD: No part of this information may be reproduced or distributed without permission of IBFD.

Disclaimer: IBFD will not be liable for any damages arising from the use of this information.

Exported / Printed on 22 Nov. 2023 by Maria.L.Rojas@ar.ey.com.

Australia - Transfer Pricing & Dispute Resolution - Country Tax Guides (Last Reviewed: 31 May 2023)

behaviours (as evidenced in their tax affairs) and the level of risk exhibited.[16] Taxpayers subject to a “partnering” approach will

generally be subject to “less intensive” compliance interactions whilst taxpayers subject to an “influencing” approach can expect

“firm approaches” from the ATO such as the use by it of formal information gather powers.[17]

The ATO publishes PCGs which provide a self-assessment risk framework to help taxpayers assess the ATO’s likely view of the

risk associated with particular arrangements.[18] It should be noted that taxpayers may be required to disclose the outcome of their

risk assessment under the PCGs (if relevant) in the Reportable Tax Position schedule to their income tax return. The PCGs allow

the ATO to differentiate risk, prioritize the deployment of compliance resources and provide guidance on the type of engagement

taxpayers can expect from the ATO. The ATO has represented that arrangements which are categorised as low risk will not

generally attract the allocation of compliance resources, although resources may still be allocated to confirm the risk categorization

is correct,[19] however, it is important to stress that the guidelines do not create safe harbours for taxpayers. Further, it is important

to understand that PCGs are merely statements of the ATO’s “practical administration approach” and are not “public rulings” – as

such, they do not have a legally binding effect.[20]

Transfer pricing is a key focus area of the ATO and considered a critical component of the Australian taxation system.[21] As noted

at section 1.2.2.1., the federal government has extended the funding of the Tax Avoidance Taskforce until 30 June 2026.

2.2. Primary current controversies

2.2.1. Areas of ATO focus

The broad areas that the ATO is focusing upon include:[22]

- financing transactions, including related-party derivatives, interest-free loans (outbound and inbound), cash pooling

arrangements and guarantee fees;

- offshore hubs (marketing or procurement) or service centres;

- inbound distribution arrangements;

- arrangements relating to intangible assets, in particular the documentation of activities in relation to the development,

enhancement, maintenance, protection and/or exploitation of intangibles;

- inbound and outbound supplies of goods and services;

- management, administrative and technical services, in particular the documentation of the beneficial nature of the service and

the appropriateness of allocation keys;

- research and development performed on behalf of an overseas party; and

- insurance and reinsurance.

16. ATO, Top 100 population, available at https://www.ato.gov.au/Business/Large-business/Top-100-population/ (accessed 20 June 2023).

17. ATO, Action Differentiation Framework, available at https://www.ato.gov.au/business/large-business/action-differentiation-framework/ (accessed 20 June 2023).

18. For example, in relation to transfer pricing, see Practical Compliance Guideline (PCG) 2017/1 concerning centralized operating models involving procurement,

marketing, sales and distribution functions; Practical Compliance Guideline (PCG) 2017/4 in relation to cross-border related-party financing arrangements and

related transactions, Practical Compliance Guideline (PCG) 2017/8 in relation to the use of internal derivatives by multinational banks; Practical Compliance

Guideline (PCG) 2019/1 in relation to transfer pricing issues related to inbound distribution arrangements; Practical Compliance Guideline (PCG) 2020/1 in

relation to transfer pricing issues related to projects involving the use of non-resident owned mobile offshore drilling units in Australian waters; and draft Practical

Compliance Guide (PCG) 2023/D2 in relation to intangibles arrangements.

19. For example, see ATO, Practical Compliance Guideline (PCG) 2017/1, at para. 26, available at https://www.ato.gov.au/law/view/document?

src=rs&pit=99991231235958&arc=false&start=1&pageSize=10&total=10&num=9&docid=COG%2FPCG20171%2FNAT%2FATO

%2F00001&dc=false&stype=find&df=1897&tm=or-basic-PCG%202017%2F1DC2; Practical Compliance Guideline (PCG) 2017/2, at para. 12, available

at https://www.ato.gov.au/law/view/document?DocID=COG/PCG20172/NAT/ATO/00001; Practical Compliance Guideline (PCG) 2017/4, at paras. 17-18,

available at https://www.ato.gov.au/law/view/document?src=hs&pit=99991231235958&arc=false&start=1&pageSize=10&total=6&num=4&docid=COG

%2FPCG20174%2FNAT%2FATO%2F00001&dc=false&stype=find&tm=phrase-basic-PCG%202017%2F4; Practical Compliance Guideline

(PCG) 2019/1, at paras. 27-32, available at https://www.ato.gov.au/law/view/document?DocID=COG/PCG20191/NAT/ATO/00001;

and, more recently, Practical Compliance Guideline (PCG) 2020/1, at para. 29, available at https://www.ato.gov.au/law/view/document?

src=hs&pit=99991231235958&arc=false&start=1&pageSize=10&total=1&num=0&docid=COG%2FPCG20201%2FNAT%2FATO

%2F00001&dc=false&stype=find&tm=phrase-basic-PCG%202020%2F1 (all accessed 20 June 2023).

20. See ATO, Practical Compliance Guideline (PCG) 2016/1, at para. 24, available at https://www.ato.gov.au/law/view/document?docid=COG/PCG20161/NAT/

ATO/00001&PiT=20160603000001 (accessed 12 July 2023).

21. J. Hirschhorn, Second Commissioner, Welcome address and opening remarks at the Tax Institute National Transfer Pricing Conference (14 Aug. 2019), available

at https://www.ato.gov.au/Media-centre/Speeches/Other/Transfer-pricing-a-key-focus-for-ATO/ (accessed 12 July 2023).

22. ATO, Findings report top 100 income tax and GST programs, available at https://www.ato.gov.au/Business/Large-business/In-detail/Findings-report-Top-100-

income-tax-and-GST-program/#Taxrisksflaggedtomarket (accessed 20 June 2023).

S. Grieve, Australia - Transfer Pricing & Dispute Resolution, Country Tax Guides IBFD (accessed 2 August 2023). 4

© Copyright 2023 IBFD: No part of this information may be reproduced or distributed without permission of IBFD.

Disclaimer: IBFD will not be liable for any damages arising from the use of this information.

Exported / Printed on 22 Nov. 2023 by Maria.L.Rojas@ar.ey.com.

Australia - Transfer Pricing & Dispute Resolution - Country Tax Guides (Last Reviewed: 31 May 2023)

Common issues that the ATO has stated that it has identified include:

- inadequate information to support transfer pricing positions; and

- changes in transfer pricing methodologies without an underlying change to the functional profile of the taxpayer and the

selection of inappropriate methodologies for a particular functional profile.

2.2.2. COVID-19

The ATO has previously acknowledged that COVID-19 may result in related-party arrangements being terminated, amended or

replaced and encouraged taxpayers which were considering altering their related-party arrangements due to COVID-19 to engage

with the ATO.[23]

The ATO has flagged that, when undertaking compliance activities, it will seek to understand and assess:

- the taxpayer’s function, asset and risk profile before and after COVID-19;

- the actual economic impacts of COVID-19 on the taxpayer’s Australian operations, which may include an analysis of how

COVID-19 has impacted the taxpayer’s industry more broadly;

- the contractual arrangements between the taxpayer and its related parties, and whether any obligations or material terms and

conditions have been varied, amended or terminated;

- evidence of the impact (if any) of COVID-19 on the specific product and service offerings of the taxpayer and how this impacts

upon its financial results; and

- evidence of changes in business strategies as a result of COVID-19, including decisions made, outcomes sorted and actions

taken to give effect to those strategies.[24]

The ATO has emphasized the importance of gathering evidence and contemporaneous documentation regarding the impact of

COVID-19 on the taxpayer’s business and supporting any business changes that were made.[25] The business changes which the

ATO has initially flagged that it will be reviewing include:

- early termination or repayments of related-party dealings and liabilities which trigger deductions for foreign exchange losses;

- changes which reduce ongoing withholding tax obligations;

- changes to rights or property provided that reduce assessable income; and

- changes that increase the risks assumed by, or allocation of, global losses to limited risk entities.[26]

The ATO has stated that it will be examining documentation to assess whether:

- independent parties dealing wholly independently in comparable circumstances would have agreed to change their

arrangements or enter into the new arrangements (for example, do the new arrangements have limited benefits, or result in a

detriment, for the taxpayer);[27]

- there was a mismatch between the substance and form of the changes;

- there was a tax avoidance purpose (presumably to assess the potential application of Australia’s various anti-avoidance

rules rather than to support a transfer pricing adjustment – for a discussion on the relevance of purpose to Australia’s transfer

pricing rules, see section 3.3.); or

23. ATO, COVID-19 economic impacts on transfer pricing arrangements, available at https://www.ato.gov.au/Business/International-tax-for-business/In-detail/

Transfer-pricing/COVID-19-economic-impacts-on-transfer-pricing-arrangements/ (accessed 12 July 2023).

24. ATO, COVID-19 economic impacts on transfer pricing arrangements – How we assess the economic impacts of COVID-19 on transfer pricing arrangements,

available at https://www.ato.gov.au/Business/International-tax-for-business/In-detail/Transfer-pricing/COVID-19-economic-impacts-on-transfer-pricing-

arrangements/?page=1#How_we_assess_the_economic_impacts_of_COVID_19_on_transfer_pricing_arrangements (accessed 12 July 2023).

25. ATO, COVID-19 economic impacts on transfer pricing arrangements – How we assess the economic impacts of COVID-19 on transfer pricing arrangements,

available at https://www.ato.gov.au/Business/International-tax-for-business/In-detail/Transfer-pricing/COVID-19-economic-impacts-on-transfer-pricing-

arrangements/?page=1#How_we_assess_the_economic_impacts_of_COVID_19_on_transfer_pricing_arrangements (accessed 12 July 2023).

26. ATO, Changing related party agreements, available at https://www.ato.gov.au/misc/downloads/pdf/qc62954.pdf (accessed 12 July 2023).

27. The author observes that this ATO guidance was published prior to the Full Federal Court handing down its decision in the Glencore Appeal. As discussed further

in the discussion of that case at sec. 3.3. the Full Federal Court in that case had held this line of reasoning was not relevant.

S. Grieve, Australia - Transfer Pricing & Dispute Resolution, Country Tax Guides IBFD (accessed 2 August 2023). 5

© Copyright 2023 IBFD: No part of this information may be reproduced or distributed without permission of IBFD.

Disclaimer: IBFD will not be liable for any damages arising from the use of this information.

Exported / Printed on 22 Nov. 2023 by Maria.L.Rojas@ar.ey.com.

Australia - Transfer Pricing & Dispute Resolution - Country Tax Guides (Last Reviewed: 31 May 2023)

- the changes to the related party arrangements and the commercial justifications for the changes had originated with a tax

adviser.[28]

The ATO has also acknowledged that, at least in the short term, analyses of comparable benchmarking may not support transfer

pricing outcomes which have been impacted by COVID-19. On that basis, the ATO has stated that it will seek to understand the

financial outcomes a taxpayer would have been able to achieve “but for” COVID-19.[29]

One area where the ATO has provided more guidance is in relation to the transfer pricing treatment of payments received by

businesses under Australia’s COVID-19 wage subsidy program known as “JobKeeper”. The ATO’s position is that independent

parties would not share the benefit of government assistance payments and therefore, Australian entities should retain the benefit

of the JobKeeper payments they have received. In the context of an Australian service provider, this means the ATO expects

that the cost base of services provided should not have been reduced by the benefit of JobKeeper payments that have been

received.[30]

2.3. Audit process and milestones

2.3.1. Authorities involved

Reviews and audits are carried out by the relevant business line within the ATO responsible for the taxpayer. For instance, the

Public Groups Compliance Section conducts reviews and audits of listed Australian companies and multinational companies.

2.3.2. Joint audits

ATO investigations can include the cooperative involvement of many different parts of the ATO and the examination of multiple

issues. For example, a taxpayer can be simultaneously audited by the ATO on any number of issues, including direct and indirect

taxes administered by the ATO. Indeed, it is not unheard of for taxpayers to attend meetings with the ATO on a particular issue to

find representatives from other ATO teams attending.

The ATO also works with revenue authorities of other jurisdictions to address tax evasion and crime on a global scale. The ATO’s

“global cooperation” includes strategies such as investigations and audits with international tax administrations using Australia’s

bilateral tax treaties and the OECD’s Convention on Mutual Administrative Assistance on Tax Matters.[31] Australia was an original

member of the Joint International Tax Shelter Information Centre, originally established in 2004 to combat cross-border tax

avoidance and is a member of the reformed Joint International Taskforce on Shared Intelligence and Collaboration (JITSIC)

initiative. Australia’s Commissioner, Mr Chris Jordan AO, is currently the Vice-Chair of the OECD’s Forum on Tax Administration

with sponsorship of the JITSIC.[32] The ATO is also a member of the J5 (the Joint Chiefs of Global Tax Enforcement) formed in

2018 to tackle, amongst other, international tax crime and those who act as the facilitators of global tax evasion.[33] The other

members of the J5 are His Majesty’s Revenue and Customs, the Internal Revenue Service Criminal Investigations from the United

States, the Canada Revenue Agency and the Dutch Fiscal Information and Investigation Service.[34]

Whilst the ATO has participated in joint audits with foreign tax administrations, it is uncertain how prevalent this practice is.

In November 2017, Mr Chris Jordan, Commissioner, commented that he planned to launch co-ordinated investigations with

authorities in Europe and around the world with “more real-time, multi-country projects and joint audits”.[35]

2.3.3. Audit timeline

ATO compliance activity typically comprises the following phases: general information gathering, risk review, audit and

assessment. Where an issue can be resolved at a particular phase, it obviously does not proceed to the next phase. Where

an issue is unable to be resolved and an assessment is raised, the taxpayer may pursue an objection and if the objection is

determined unfavourably then proceed to litigation (discussed in section 3.2.).

28. ATO, Changing related party agreements, available at https://www.ato.gov.au/misc/downloads/pdf/qc62954.pdf (accessed 12 July 2023).

29. ATO, COVID-19 economic impacts on transfer pricing arrangements – How to support the arm’s length nature of your transfer pricing outcomes, available at

https://www.ato.gov.au/Business/International-tax-for-business/In-detail/Transfer-pricing/COVID-19-economic-impacts-on-transfer-pricing-arrangements/?

page=1#How_to_support_the_arm_s_length_nature_of_your_transfer_pricing_outcomes (accessed 12 July 2023).

30. ATO, Transfer pricing arrangements and JobKeeper payments, available at https://www.ato.gov.au/general/JobKeeper-payment/ (accessed 12 July 2023).

31. See ATO, Global Cooperation, available at https://www.ato.gov.au/General/The-fight-against-tax-crime/Our-focus/Global-cooperation/ (accessed 12 July 2023).

32. OECD, Forum on Tax Administration - Joint International Taskforce on Shared Intelligence and Collaboration, available at https://www.oecd.org/tax/forum-on-tax-

administration/jitsic/ (accessed 12 July 2023).

33. See ATO, The fight against tax crime - Joint Chiefs of Global Tax Enforcement, available at https://www.ato.gov.au/General/The-fight-against-tax-crime/Our-

focus/Joint-Chiefs-of-Global-Tax-Enforcement/ (accessed 12 July 2023).

34. See ATO, The fight against tax crime - Joint Chiefs of Global Tax Enforcement, available at https://www.ato.gov.au/General/The-fight-against-tax-crime/Our-

focus/Joint-Chiefs-of-Global-Tax-Enforcement/ (accessed 12 July 2023).

35. The Australian newspaper, $5bn tax crackdown targets multinational technology giants (30 Nov. 2017).

S. Grieve, Australia - Transfer Pricing & Dispute Resolution, Country Tax Guides IBFD (accessed 2 August 2023). 6

© Copyright 2023 IBFD: No part of this information may be reproduced or distributed without permission of IBFD.

Disclaimer: IBFD will not be liable for any damages arising from the use of this information.

Exported / Printed on 22 Nov. 2023 by Maria.L.Rojas@ar.ey.com.

Australia - Transfer Pricing & Dispute Resolution - Country Tax Guides (Last Reviewed: 31 May 2023)

General information gathering

The ATO reviews publicly available sources of information (such as annual reports) for potential issues of interest. Taxpayers must

also provide extensive and detailed information to the ATO about their interactions with related foreign entities, e.g. as part of their

income tax return or CbC reporting. The ATO can also initiate programs to gather information directly from taxpayers (for example,

by initiating a risk review).

Large taxpayers may also be required by the ATO to complete a Reportable Tax Position (RTP) schedule as part of their company

tax returns. An RTP schedule requires a taxpayer to disclose its contestable and material tax positions. Since the year ended 30

June 2019, taxpayers have been required to lodge an RTP schedule if they are a public or foreign-owned company and have either

a total business income of AUD 250 million or more, or have a total business income of AUD 25 million or more, and are part of an

economic group with a total business income of AUD 250 million or more in the current or immediately prior year.[36] From 1 July

2020, the ATO expanded the requirement to lodge an RTP schedule to large private companies as well. However, for the first year

(i.e. the 2020/21 income year), only large private companies which the ATO notified of the requirement to lodge an RTP schedule

were required to do so.[37]

As discussed in section 2.1., the ATO has now published a number of PCGs which allow taxpayers to self-assess their risk

profile in relation to specific arrangements, including in relation to their marketing hub arrangements[38] and intra-group financing

transactions.[39] The ATO can request that a taxpayer provide the ATO with its self-assessed risk weighting (as determined using

those PCGs). Australia’s Foreign Investment Review Board will also apply these PCGs when assessing a proposed foreign

investment.[40] For taxpayers which are required to complete an RTP schedule, the RTP schedule requires taxpayers to disclose

their self-assessed risk zones under the PCGs.[41]

The ATO may decide to institute a risk review based on the general information it has gathered through these processes.

Risk review

The first formal step in the compliance review process is for the ATO to undertake a transfer pricing risk review.[42]

The broader and more significant a taxpayer’s international related-party dealings are, the more likely the ATO will devote

compliance resources to undertaking a risk review. The ATO has flagged that a taxpayer will be more likely to be subject to a risk

review if it:

- has significant levels of international dealings with related parties;

- pays less tax compared to industry standards; or

- has recently undertaken business restructures that materially affect its related-party international dealings.[43]

In the event that the ATO decides to proceed with a review, it usually requests detailed background information on the taxpayer’s

business and tax position and a taxpayer will often need to devote considerable resources to the review.

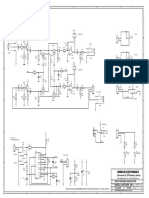

The risk for a taxpayer of the ATO proceeding from a review to a transfer pricing audit is impacted by the quality of the

documentation maintained by the taxpayer, as illustrated in Figure 1.[44]

36. For example, see ATO, Reportable tax position instructions 2022 – Who needs to complete the schedule, available at https://www.ato.gov.au/Forms/Reportable-

tax-position-schedule-instructions-2022/?page=2#Who_needs_to_complete_the_schedule_ (accessed 12 July 2023).

37. See ATO, Large Business – Reportable tax position schedule, available at https://www.ato.gov.au/Business/Large-business/Compliance-and-governance/

Reportable-tax-positions/ (accessed 12 July 2023).

38. ATO, Practical Compliance Guideline (PCG) 2017/1, available at https://www.ato.gov.au/law/view/document?

src=rs&pit=99991231235958&arc=false&start=1&pageSize=10&total=10&num=9&docid=COG%2FPCG20171%2FNAT%2FATO

%2F00001&dc=false&stype=find&df=1897&tm=or-basic-PCG%202017%2F1DC2 (accessed 12 July 2023).

39. ATO, Practical Compliance Guideline (PCG) 2017/4, available at https://www.ato.gov.au/law/view/document?

src=hs&pit=99991231235958&arc=false&start=1&pageSize=10&total=6&num=4&docid=COG%2FPCG20174%2FNAT%2FATO

%2F00001&dc=false&stype=find&tm=phrase-basic-PCG%202017%2F4 (accessed 12 July 2023).

40. Foreign Investment Review Board, Guidance Note 12 – Tax Conditions (last updated 9 July 2021).

41. For example, see questions 9 and 14 of Section C: Category C reportable tax positions.

42. See ATO, Taxation Ruling (TR) 98/11, Documentation and practical issues with setting and reviewing transfer pricing in international dealings para. 4.6 (24 June

1998), available at https://www.ato.gov.au/law/view/document?DocID=TXR/TR9811/NAT/ATO/00001 (accessed 12 July 2023). Although it should be noted that

this ruling was written in the context of the former TP rules in division 13 ITAA 36. Of course, the ATO may identify a transfer pricing issue as a result of one of its

other investigative activities (e.g. a broader client risk review).

43. ATO, International transfer pricing – introduction to concepts and risk assessment – Transfer pricing risk assessment, available at https://www.ato.gov.au/

Business/International-tax-for-business/In-detail/Transfer-pricing/International-transfer-pricing---introduction-to-concepts-and-risk-assessment/?

anchor=TransferPricing#TransferPricing (accessed 12 July 2023).

44. ATO, Taxation Ruling (TR) 98/11, Documentation and practical issues with setting and reviewing transfer pricing in international dealings para. 4.27 (24 June

1998) available at https://www.ato.gov.au/law/view/document?DocID=TXR/TR9811/NAT/ATO/00001 (accessed 12 July 2023). See also ATO, International

transfer pricing – Introduction to concepts and risk assessment – Documentation requirements, available at https://www.ato.gov.au/Business/International-tax-

S. Grieve, Australia - Transfer Pricing & Dispute Resolution, Country Tax Guides IBFD (accessed 2 August 2023). 7

© Copyright 2023 IBFD: No part of this information may be reproduced or distributed without permission of IBFD.

Disclaimer: IBFD will not be liable for any damages arising from the use of this information.

Exported / Printed on 22 Nov. 2023 by Maria.L.Rojas@ar.ey.com.

Australia - Transfer Pricing & Dispute Resolution - Country Tax Guides (Last Reviewed: 31 May 2023)

Figure 1: Risk of a transfer pricing audit

Where the review identifies that the taxpayer has poor documentation, and consistently returns losses, the taxpayer is at “very

high” risk of progressing to an audit. Conversely, a taxpayer with high-quality documentation, and which produces a “commercially

realistic result”, is at “low” risk of audit.

Audit

Once in an audit phase, the ATO will gather further information, usually by the issue of “information requests”. These requests

can take the form of “informal” requests, rather than requests involving the exercise of the ATO’s statutory access powers.[45]

Historically, the use of informal requests for information had been relatively common, however, the ATO’s use of its statutory

powers has been increasing, from 16,366 formal notices being issued in 2016-17 to 31,359 such notices in 2021-22.[46]

Most taxpayers would comply with informal requests, except to the extent they:

- relate to third-party information for which there may be confidentiality issues that necessitate a formal request;[47]

for-business/In-detail/Transfer-pricing/International-transfer-pricing---introduction-to-concepts-and-risk-assessment/?page=5#Documentation_requirements

(accessed 12 July 2023).

45. Formal access powers exist to require the provision of information held onshore and to request a taxpayer to obtain information held offshore, under secs. 353-10

and 353-25, sch. 1 TAA 1953 respectively. The ATO also has powers to access premises to, amongst other things, inspect and make copies of documents under

sec. 353-15, sch. 1 TAA 1953.

46. ATO, Annual Report 2021/22, Appendix 10: Use of access powers.

47. Confidentiality obligations do not override the statutory obligation to comply with a notice issued under sec. 353-10, sch. 1 TAA 1953; see Australia and New

Zealand Banking Group Limited v. Konza [2012] FCA 196 (in the context of the predecessor provision in sec. 264 ITAA 36).

S. Grieve, Australia - Transfer Pricing & Dispute Resolution, Country Tax Guides IBFD (accessed 2 August 2023). 8

© Copyright 2023 IBFD: No part of this information may be reproduced or distributed without permission of IBFD.

Disclaimer: IBFD will not be liable for any damages arising from the use of this information.

Exported / Printed on 22 Nov. 2023 by Maria.L.Rojas@ar.ey.com.

Australia - Transfer Pricing & Dispute Resolution - Country Tax Guides (Last Reviewed: 31 May 2023)

- seek access to confidential communications comprising legal advice or requests for legal advice or service protected by legal

professional privilege;[48]

- include professional accounting advice which the Commissioner accepts should be confidential (protected under the

administrative concession known as the “Accountants’ Concession”);[49] or

- relate to advice on tax compliance risk given to a company’s board of directors (protected under the administrative

concession known as the “Corporate Board Advice Concession”).[50]

Apart from these matters, there are effectively no restrictions on the information which the ATO may request,[51] and which may

include commercially sensitive information. In the latter respect, taxpayers would usually draw some comfort from the strict secrecy

provisions that apply to the collection and use of this information,[52] and which extends to experts engaged by the ATO.[53] Indeed,

at the Senate Economics References Committee inquiry into Corporate Tax Avoidance (Senate Inquiry), the Commissioner

initially refused to disclose confidential taxpayer information at the public hearings,[54] although subsequently he did reveal some

information to correct perceived “errors” in the evidence given by particular taxpayers to the Senate Inquiry.[55]

ATO economists will also become involved at the audit stage to assist the audit team to arrive at the ATO’s view of the relevant

arm’s length conditions.[56] If this is materially different to that adopted by the taxpayer, a position paper is issued by the ATO

setting out the basis for the ATO’s determination. Generally, the taxpayer has an opportunity to respond to the position paper

before the ATO issues a Statement of Audit Position.[57]

Taxpayers with a turnover greater than AUD 250 million may also request an independent review of the ATO’s Statement of Audit

Position within 10 working days of receiving the statement.[58] However, the circumstances in which this process is available, are

very limited in transfer pricing matters.

Amended assessment

Once the audit is complete, the ATO will notify the taxpayer of the outcome (for example, through the issue of a Statement of Audit

Position) and a delegate of the Commissioner will then decide whether to issue an amended assessment. It should be noted that

under division 13 of the ITAA 36 and subdivision 815-A of the ITAA 97, a determination had to be made before the ATO could

issue an amended assessment in relation to the transfer pricing issue. However, this does not apply for subdivisions 815-B to

D, which operate on a self-assessment basis; that is, corporate taxpayers are required to consider the application of the transfer

pricing provisions in preparing their tax returns, with an assessment being deemed to arise for the tax shown in the return. The

Commissioner can then issue an amended assessment, subject to certain time limitations, if he disagrees with the taxpayer’s self-

assessment. Subdivisions 815-B, 815-C and 815-D apply in relation to income years starting on or after 1 July 2013.[59]

48. In Daniels Corporation International v. Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (2002) HCA 49, the High Court of Australia confirmed that statutory

access powers similar to those of the ATO did not abrogate legal professional privilege.

49. ATO, Our Approach to Information Gathering (22 June 2022) available at https://www.ato.gov.au/about-ato/commitments-and-reporting/in-detail/privacy-and-

information-gathering/our-approach-to-information-gathering/ (accessed 12 July 2023).

50. ATO, Practice Statement Law Administration (PS LA) 2004/14, Access to ‘corporate board documents on tax compliance risk’ (11 Mar. 2016), available at

https://www.ato.gov.au/law/view/document?Docid=PSR/PS200414/NAT/ATO/00001 (accessed 12 July 2023).

51. Enquiries must be for the purposes of administering the tax legislation, but this is a very broad concept (AU: HCA, 30 Nov. 1990, 46, Industrial Equity Ltd v.

Deputy Commissioner of Taxation). In that case, the High Court of Australia indicated that the access powers allow the Commissioner to engage in a “fishing

expedition”, (at para. 24 per Chief Justice Mason, Justice Brennan, Justice Deane, Justice Dawson, Justice Toohey and Justice McHugh) or a “roving

enquiry” (at para. 16, per Justice Gaudron). See also AU: FCAFC, 26 Feb. 2021, 43, CUB Australia Holding Pty Ltd v. Commissioner of Taxation, discussed in

sec. 2.3.14.

52. Div. 355, sch. 1 TAA 1953.

53. AU: FCA, 15 Mar. 1995, 1214, Consolidated Press Holding Ltd v. Commissioner of Taxation,

54. Official Committee Hansard, Senate Economics References Committee – Corporate tax avoidance, transcript of 8 Apr. 2015, pp. 21, 23, 24 and 30.

55. Senate Inquiry, Answers to questions on notice from a public hearing held in Sydney on 8 April 2015, received from the Australian Taxation Office on 24

April 2015; Answers to questions on notice from a public hearing held in Sydney on 22 April 2015, received from the Australian Taxation Office on 1 May

2015; and Answers to additional questions on notice, received from the Australian Taxation Office on 8 May 2015, available at https://www.aph.gov.au/

Parliamentary_Business/Committees/Senate/Economics/Corporate_Tax_Avoidance/Additional_Documents?docType=Answer%20to%20Question%20on

%20Notice (accessed 12 July 2023).

56. ATO, Practice Statement Law Administration (PS LA) 2013/2, Provision of accredited economic advice (13 May 2014).

57. See, for example, ATO, Practical Compliance Guideline (PCG) 2017/1, at para. 99, available at https://www.ato.gov.au/law/view/document?docid=COG/

PCG20171/NAT/ATO/00001 (accessed 12 July 2023).

58. ATO, Independent review of the Statement of Audit Position for groups with a turnover greater than $250m, available at https://www.ato.gov.au/General/

Dispute-or-object-to-an-ATO-decision/In-detail/Avoiding-and-resolving-disputes/Independent-review/Large-market-independent-review---turnover-over-$250m/

(accessed 12 July 2023). For completeness, there is also an independent review service for certain small businesses with a turnover of less than AUD 10 million,

see ATO, Independent review for small businesses with turnover less than $10 million, available at https://www.ato.gov.au/General/Dispute-or-object-to-an-ATO-

decision/In-detail/Avoiding-and-resolving-disputes/Independent-review/Independent-review-for-small-businesses-with-turnover-less-than-$10-million/ (accessed

12 July 2023).

59. Division 815 Income Tax (Transitional Provisions) Act 1997 (Cth).

S. Grieve, Australia - Transfer Pricing & Dispute Resolution, Country Tax Guides IBFD (accessed 2 August 2023). 9

© Copyright 2023 IBFD: No part of this information may be reproduced or distributed without permission of IBFD.

Disclaimer: IBFD will not be liable for any damages arising from the use of this information.

Exported / Printed on 22 Nov. 2023 by Maria.L.Rojas@ar.ey.com.

Australia - Transfer Pricing & Dispute Resolution - Country Tax Guides (Last Reviewed: 31 May 2023)

The transfer pricing review and audit process is illustrated in Figure 2, published by the ATO as part of Taxation Ruling (TR) 98/11

- Income tax: Documentation and practical issues associated with setting and reviewing transfer pricing in international dealings:[60]

60. ATO, Taxation Ruling (TR) 98/11, at para. 4.25, available at https://www.ato.gov.au/law/view/document?DocID=TXR/TR9811/NAT/ATO/00001 (accessed 12

July 2023).

S. Grieve, Australia - Transfer Pricing & Dispute Resolution, Country Tax Guides IBFD (accessed 2 August 2023). 10

© Copyright 2023 IBFD: No part of this information may be reproduced or distributed without permission of IBFD.

Disclaimer: IBFD will not be liable for any damages arising from the use of this information.

Exported / Printed on 22 Nov. 2023 by Maria.L.Rojas@ar.ey.com.

Australia - Transfer Pricing & Dispute Resolution - Country Tax Guides (Last Reviewed: 31 May 2023)

Figure 2: ATO transfer pricing review and audit process

S. Grieve, Australia - Transfer Pricing & Dispute Resolution, Country Tax Guides IBFD (accessed 2 August 2023). 11

© Copyright 2023 IBFD: No part of this information may be reproduced or distributed without permission of IBFD.

Disclaimer: IBFD will not be liable for any damages arising from the use of this information.

Exported / Printed on 22 Nov. 2023 by Maria.L.Rojas@ar.ey.com.

Australia - Transfer Pricing & Dispute Resolution - Country Tax Guides (Last Reviewed: 31 May 2023)

2.3.4. Rights and obligations of taxpayers

The main rights and obligations of taxpayers vis-à-vis the ATO are set out in the ATO Charter (previously known as the Taxpayers’

Charter).[61] The Taxpayers’ Charter is a policy guide published by the ATO which is intended to provide information to taxpayers

on their legal rights and what they can expect from their dealings with the ATO.[62]

Taxpayers’ rights include the right to be treated fairly and reasonably by the ATO. Specifically, the ATO will (i) treat taxpayer’s

with courtesy, consideration and respect; act with honesty and integrity; (ii) be impartial and act in good faith; (iii) treat taxpayers

as being honest unless the ATO has reason to think otherwise and give taxpayers an opportunity to explain; and (iv) work with the

people who taxpayers have chosen to represent them.[63]

The main obligations of taxpayers include: (i) being truthful and acting within the law; (ii) responding to queries in a timely manner

and providing all relevant information; (iii) meeting lodgement and payment obligations on time; and (iv) keeping proper records.[64]

2.3.5. Rights and obligations of tax authorities

The Commissioner’s rights include broad statutory access and information-gathering powers, which can be used not only in

relation to specific taxpayers, but also in respect of third parties and advisors.[65] [66] The extent of the Commissioner’s powers has

previously come under criticism.[67]

The obligations of the ATO are set out in the ATO Charter. In particular, the ATO is required to treat taxpayers fairly and

consistently, help taxpayers understand how the law applies to their circumstances and inform taxpayers of their review rights.[68]

The ATO has the right to discontinue its investigation or audit of a taxpayer at any time, although in this event, the taxpayer does

not have any real ability to recover the costs it has incurred in defending its position.

2.3.6. Information used in tax audits

In undertaking an audit, the ATO aims to obtain a broad sense of the commerciality of an arrangement, in order to determine

whether a taxpayer has complied with its tax obligations. In doing so, the ATO will consider a wide range of information and

documentation. As the conduct of audits is not governed by legislation, the information examined by the ATO can be extensive.

2.3.7. Confidentiality of information

As noted in section 2.3.3., the Commissioner is bound by a number of statutory secrecy and privacy rules.[69] These rules bind not

only those ATO officers who come into possession of confidential information directly, but also any other government agency that

comes into possession of the information and experts engaged by the ATO. However, there are exceptions to the obligation of

secrecy.[70]

In 2012, the government ratified the Convention on Mutual Administrative Assistance in Tax Matters (MAA Convention), which

took effect from 1 December 2012. The MAA Convention provides for further exchange of information and administrative

cooperation between national tax authorities. Information obtained by a party under the MAA Convention is subject to the same

domestic confidentiality rules as if that information was obtained under domestic law.[71]

In June 2014, the government released a discussion paper to seek the views of stakeholders on the Common Reporting Standard

for the automatic exchange of tax information (CRS) which was endorsed by G20 Finance Ministers and Central Bank Governors

61. ATO, ATO Charter: About our Charter, QC 57115 (last modified 26 June 2023), available at https://www.ato.gov.au/About-ATO/Commitments-and-reporting/

ATO-Charter/Our-Charter/ (accessed 30 July 2023).

62. Although the Taxpayers’ Charter is not legally binding, taxpayers have a legitimate expectation that it will be followed and may be denied procedural fairness if this

is not the case. See AU: FCA, 13 Nov. 1998, 1439, Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu v. Deputy Commissioner of Taxation; AU: FCA, 13 Mar. 2000, 270, ONE.TEL Ltd

v. Deputy Commissioner of Taxation.

63. ATO, ATO Charter: Our Commitment to you; QC 57115 (last modified 26 June 2023), available at https://www.ato.gov.au/About-ATO/Commitments-and-

reporting/ATO-Charter/Our-Charter/#Yourrightswhatyoucanexpectfromus1 (accessed 30 July 2023).

64. ATO, ATO Charter: What we ask of you; QC 57115 (last modified 26 June 2023), available at https://www.ato.gov.au/About-ATO/Commitments-and-reporting/

ATO-Charter/Our-Charter/#Whatweaskofyou1 (accessed 30 July 2023).

65. Secs. 353-10, 353-15 and 353-25, sch. 1 TAA 1953.

66. ATO, ATO Charter: Our Commitment to you; QC 57115 (last modified 26 June 2023), available at https://www.ato.gov.au/About-ATO/Commitments-and-

reporting/ATO-Charter/Our-Charter/#Yourrightswhatyoucanexpectfromus1 (accessed 30 July 2023).

67. Sydney Morning Herald, Tax Commissioner's power 'lurks beneath surface like a salt-water crocodile': expert (14 Mar. 2018), available at https://

www.smh.com.au/business/the-economy/tax-commissioner-s-power-lurks-beneath-surface-like-a-salt-water-crocodile-expert-20180312-p4z40i.html (accessed

12 July 2023).

68. ATO, ATO Charter: Steps to take if you would like a decision reviewed; QC 57115 (last modified 26 June 2023).

69. Div. 355, sch. 1 TAA 1953 and, more generally, under the Privacy Act 1988.

70. For example, see secs. 355-45 to 355-55 and 355-65 to 355-72, sch. 1 TAA 1953. See also the example in sec. 2.3.3.

71. The Hon D. Bradbury MP, Australia ratifies multilateral tax cooperation agreement, Media release No. 114 (5 Oct. 2012). See also art. 22 Convention on Mutual

Administrative Assistance in Tax Matters. See also the Hon Joe Hockey MP and Hon Steven Ciobo MP, Australia signs up to combat tax evasion (3 June 2015).

S. Grieve, Australia - Transfer Pricing & Dispute Resolution, Country Tax Guides IBFD (accessed 2 August 2023). 12

© Copyright 2023 IBFD: No part of this information may be reproduced or distributed without permission of IBFD.

Disclaimer: IBFD will not be liable for any damages arising from the use of this information.

Exported / Printed on 22 Nov. 2023 by Maria.L.Rojas@ar.ey.com.

Australia - Transfer Pricing & Dispute Resolution - Country Tax Guides (Last Reviewed: 31 May 2023)

in February 2014 and recommitted to at the G20 summit in November 2014.[72] Australia signed the Multilateral Competent

Authority Agreement on Automatic Exchange of Financial Account Information on 3 June 2015.

The CRS provides a common international standard for:

- the collection of financial account information by financial institutions in participating jurisdictions on account holders who are

residents in another jurisdiction;

- the reporting of that information to the jurisdictions’ tax authorities; and

- the exchange of that information with the respective tax authorities of the non-residents.

This has now been implemented domestically in subdivision 396-C of Schedule 1 to the TAA 1953.

The CRS commenced operation in Australia on 1 July 2017, with the first reporting of reportable accounts to the ATO on 31 July

2018 and the first automatic exchange having been planned for 30 September 2018.[73] Australia exchanged information with 72

partners during 2021 and with 76 partners in 2022[74] under the OECD’s Standard on Automatic Exchange of Financial Account

Information (referred to as the AEOI Standard).[75]

In 2020, the OECD Global Forum on Transparency and Exchange of Information for Tax Purposes conducted peer reviews of the

domestic and international legal frameworks established by the first 100 jurisdictions to implement the AEOI Standard. The overall

findings in relation to Australia’s legal framework were that it is “in place but needs improvement” due to Australia’s domestic law

providing for non-reporting financial institutions and excluded accounts which were found not to meet the requirements of the AEOI

Standard.[76] Australia’s rules for preventing the adoption of practices to circumvent reporting and due diligence procedures were

also found to be insufficient.[77] In May 2021, the ATO published additional guidance on its website stating that reporting financial

institutions must have strong measures in place to obtain self-certifications from account holders of their CRS status as part of their

account opening process (as opposed to previous guidance which required reporting financial institutions take all reasonable steps

to compel compliance).[78]

In addition, subdivision 396-A facilitates the sharing of information with the United States in relation to the Foreign Account Tax

Compliance Act (FATCA). Information that is exchanged under FATCA is subject to the confidentiality protections in article 25 of

the Australia-United States tax treaty.[79] In September 2015, the ATO announced the first exchange of information pursuant to the

FATCA arrangements.[80] The ATO has issued combined guidance covering both FATCA and CRS.[81]

Australia has also implemented BEPS Action 13 (CbC reporting) with effect from income years commencing on or after 1 July

2016. Australia has also signed the OECD’s multilateral treaty for the exchange of CbC reports which requires signatories to have

the necessary legal framework and infrastructure to safeguard the confidentiality of exchanged CbC reports.[82] However, it is worth

noting that as part of a push for increased transparency in recent times, the federal government announced in its October 2022-23

Budget that it would introduce a separate public country-by-country (CbC) reporting regime which would require multinational

entities to release certain tax-related information on a CbC basis.

Finally, Australia has considered implementing BEPS Action 12 (mandatory disclosure rules). On 3 May 2016, the government

released a discussion paper seeking the community’s input on how mandatory disclosure rules should be framed in the Australian

72. The Treasury, Discussion Paper – Common Reporting Standard for the automatic exchange of tax information, June 2014; The Hon Tony Abbott MP, G20 Helps

Restore Fairness to Global Tax System, Media Release (16 Nov. 2014).

73. ATO, Automatic exchange of information guidance - CRS and FATCA, available at https://www.ato.gov.au/General/International-tax-agreements/In-detail/

International-arrangements/Automatic-exchange-of-information---CRS-and-FATCA/?page=1#1_4_Implementation_timelines (accessed 12 July 2023).

74. See OECD, exchanges of information that took place in 2021 and 2022 under the AEOI Standard (as of 20 Feb. 2023), available at https://www.oecd.org/tax/

automatic-exchange/commitment-and-monitoring-process/AEOI-exchanges.pdf (accessed 12 July 2023).

75. OECD, Automatic Exchange Portal – Commitment and Monitoring Process, available at http://www.oecd.org/tax/automatic-exchange/commitment-and-

monitoring-process/ (accessed 12 July 2023).

76. See OECD, Global Forum on Transparency and Exchange of Information for Tax Purposes, Peer Review of the Automatic Exchange of Financial

Account Information 2020, at pp. 49-51, available at https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/taxation/peer-review-of-the-automatic-exchange-of-financial-account-

information-2020_175eeff4-en (accessed 12 July 2023).

77. See OECD, Global Forum on Transparency and Exchange of Information for Tax Purposes, Peer Review of the Automatic Exchange of Financial

Account Information 2020. at pp. 49-51, available at https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/taxation/peer-review-of-the-automatic-exchange-of-financial-account-

information-2020_175eeff4-en (accessed 12 July 2023).

78. See ATO, Obtaining valid self-certifications for all new accounts, available at https://www.ato.gov.au/General/International-tax-agreements/In-detail/Obtaining-

valid-self-certifications-for-all-new-accounts/ (accessed 12 July 2023).

79. Agreement between the Government of Australia and the Government of the United States of America to Improve International Tax Compliance and to Implement

FATCA, art. 3(7).

80. ATO, A major step in global transparency, media release (23 Sept. 2015).

81. ATO, Automatic exchange of information guidance – CRS and FATCA, https://www.ato.gov.au/General/International-tax-agreements/In-detail/International-

arrangements/Automatic-exchange-of-information---CRS-and-FATCA/ (accessed 12 July 2023).

82. Multilateral Competent Authority Agreement on the exchange of Country-by-Country reports, secs. 5 and 8.

S. Grieve, Australia - Transfer Pricing & Dispute Resolution, Country Tax Guides IBFD (accessed 2 August 2023). 13

© Copyright 2023 IBFD: No part of this information may be reproduced or distributed without permission of IBFD.

Disclaimer: IBFD will not be liable for any damages arising from the use of this information.

Exported / Printed on 22 Nov. 2023 by Maria.L.Rojas@ar.ey.com.

Australia - Transfer Pricing & Dispute Resolution - Country Tax Guides (Last Reviewed: 31 May 2023)

context.[83] The consultation process concluded on 15 July 2016 and there is yet to be any domestic legislation introduced to

implement disclosure rules.

2.3.8. Right of access to information

The ATO has formal access and information-gathering powers under sections 353-10, 353-15 and 353-25 of Schedule 1 to the

TAA 1953. See section 2.3.5.

2.3.9. Penalties

Penalties imposed under subdivisions 815-B to D are explicitly linked to contemporaneous transfer pricing documentation

requirements.[84] Taxpayers may be liable for a base penalty of 25% or 50%, depending on whether the taxpayer entered the

transaction for the sole or dominant purpose of obtaining a scheme benefit, if they fail to keep the relevant records.[85] The

base penalty is reduced to 10% if the taxpayer did not possess the requisite purpose of obtaining a scheme benefit and the

documentation supports a “reasonably arguable position”. The base penalty rate may also be reduced in cases where the taxpayer

makes a “voluntary disclosure” to the ATO.[86]

For the purposes of penalty mitigation, documentation is considered contemporaneous if it has been prepared before the time by

which the entity lodges its income tax return for the income year.[87]

The maximum administrative penalties are doubled for companies with a global revenue of AUD 1 billion or more that enter into

tax avoidance or profit shifting schemes for income years commencing on or after 1 July 2015 (and that do not have a “reasonably

arguable position”).[88] In June 2020, the regime to double penalties for significant global entities was extended with retrospective

effect from 5 December 2019 to cover significant global entities that are also subsidiary members of consolidated groups and

multiple entry consolidated groups.[89]

2.3.10. Access to foreign-based information

There are three main ways that the ATO can seek information from outside Australia:

- by relying on the exchange of information article in the applicable tax treaty;[90]

- by issuing the taxpayer with an “offshore information notice”;[91] and

- where the information relates to a non-OECD country with which Australia has a tax information exchange agreement, by

relying on the information exchange article in that agreement.[92]

As referred to in section 2.3.7., the government now has access to foreign based information by virtue of information exchanged

under FATCA and the CRS as well as through exchanged CbC reports.

Whilst not strictly a transfer pricing measure, the ATO also has the ability, in a practical sense, to access foreign-based information

by virtue of Australia’s Diverted Profits Tax (DPT) regime. Under Australia’s DPT regime, only information provided to the ATO

during the period of review for a DPT assessment (i.e. 12 months from the date of that assessment) can be admitted into evidence

in any proceedings challenging that DPT assessment.[93] Accordingly, it may be necessary for taxpayers which find themselves

the subject of both transfer pricing and DPT action to provide the ATO with foreign-based information which they might otherwise

previously not have been under practical compulsion to provide. The ATO has released guidance to assist taxpayers comply

with their DPT obligations, including Practical Compliance Guideline (PCG) 2018/5.[94] PCG 2018/5 outlines the ATO’s client

engagement framework and its approach to risk assessment and compliance activity for the DPT, including information the ATO

83. The consultation paper is available at https://treasury.gov.au/consultation/oecd-proposals-for-mandatory-disclosure-of-tax-information/ (accessed 20 July 2023).

84. Sec. 284-250, sch. 1 TAA 1953.

85. Sec. 284-160, sch. 1 TAA 1953.

86. Sec. 284-225, sch. 1 TAA 1953.

87. Sec. 284-255(1)(a), sch. 1 TAA 1953.

88. Sec. 284-155(3) Schedule 1 TAA 1953.

89. See items 139 to 144 Treasury Laws Amendment (2019 Measures No. 3) Act 2020.

90. See e.g. art. 27 Australia-United Kingdom Income Tax Treaty (21 Aug. 2003), Treaties & Models IBFD, as defined in sec. 3AAA International Tax Agreements Act

1953 (Int AA).

91. Sec. 353-25, sch. 1 TAA 1953. The notice requests the taxpayer to give or produce such information to the Commissioner. If the taxpayer fails to comply, the

information may not be relied on later in evidence in legal proceedings without the consent of the Commissioner; sec. 353-30 sch. 1 TAA 1953.

92. See e.g. art. 5 Australia-Isle of Man Exchange of Information Treaty (29 Jan. 2009), Treaties & Models IBFD, as defined in sec. 3AAA Int AA.

93. Sec. 145-25, sch. 1 TAA 1953.

94. ATO, Practical Compliance Guideline (PCG) 2018/5, Diverted Profits Tax, at paras. 62-64 available at https://www.ato.gov.au/law/view/document?DocID=COG/

PCG20185/NAT/ATO/00001&PiT=99991231235958 (accessed 12 July 2023).

S. Grieve, Australia - Transfer Pricing & Dispute Resolution, Country Tax Guides IBFD (accessed 2 August 2023). 14

© Copyright 2023 IBFD: No part of this information may be reproduced or distributed without permission of IBFD.

Disclaimer: IBFD will not be liable for any damages arising from the use of this information.

Exported / Printed on 22 Nov. 2023 by Maria.L.Rojas@ar.ey.com.

Australia - Transfer Pricing & Dispute Resolution - Country Tax Guides (Last Reviewed: 31 May 2023)

will have regard to when applying the DPT. The ATO has also released Law Companion Ruling LCR 2018/6 which sets out the

ATO’s view on how various aspects of the DPT will apply.

2.3.11. Burden of proof

In any litigation, the burden of proof is on the taxpayer (see section 3.2.). Unfortunately, calls to create better alignment with other

OECD countries by reversing the onus of proof in respect of adjustments under subdivisions 815-B to D of the ITAA 97[95] were not

accepted by the government.

2.3.12. Statute of limitations

Under the former transfer pricing rules in division 13 of the ITAA 36 and subdivision 815-A of the ITAA 97, there was no time limit

on the ability of the Commissioner to amend assessments to give effect to a transfer pricing determination under domestic law.[96]

However, subdivisions 815-B to D of the ITAA 97 now impose a 7-year limitation period on transfer pricing adjustments from the

date of the original assessment, usually being the date when a taxpayer lodges its income tax return.[97] Subdivisions 815-B to D

apply in relation to income years starting on or after 1 July 2013.[98]

2.3.13. Information requests

In addition to requests made pursuant to the formal rights of access described in section 2.3.8., the Commissioner may (and

typically will) also make informal requests for information or access from a taxpayer.

2.3.14. Solicitor-client privilege

As discussed in section 2.3.3., the Commissioner’s access and information-gathering powers are subject to the right of taxpayers

to claim legal professional privilege in respect of certain communications. Legal professional privilege applies to communications

between:

- lawyers and their clients (or agents) which are for the dominant purpose of giving or obtaining legal advice; and

- lawyers and third parties where the communication is for the dominant purpose of conducting litigation.[99]

Communications between tax advisors that are accountants and their clients are not protected in and of themselves by

legal professional privilege. However, the Commissioner recognizes that such documents should be afforded some level of

confidentiality, and the Commissioner’s current policy is to refrain from seeking access to certain categories of accountants’

papers other than in “exceptional circumstances”.[100]

In recent years, the ATO has grown increasingly, concerned that legal professional privilege claims are being made

inappropriately, and in some cases, may even be “reckless and false”[101] leading to a legal challenge to claims made by

PricewaterhouseCoopers and one of its clients (refer further below).

The scope of legal professional privilege in Australia was recently the subject of litigation in the High Court (Australia’s highest

court). In broad terms, the question before the Court was whether a taxpayer is entitled to injunctive relief which would prevent

the ATO from using privileged documents which were stolen from the Bermuda law firm Appleby.[102] The High Court dismissed

the taxpayer’s application for relief on the basis that whilst legal professional privilege provides a right to resist the compulsory

disclosure of confidential communications or documents, legal professional privilege is not an actionable legal right.[103] The High

95. Law Council of Australia, Submission to The Treasury – Modernisation of Transfer Pricing Rules: Exposure Draft of Tax Laws Amendment (Cross Border Transfer

Pricing) Bill 2013 (17 Dec. 2012), at paras. 10-13.

96. Sec. 170(9B) ITAA 36. This may be contrasted to the general time limit for the amendment of assessments of 4 years (item 4 of the table in sec. 170(1)) in the

absence of fraud or evasion. However, this is subject to any time limit in an applicable tax treaty, such as art. 9(4) Australia-New Zealand Income Tax Treaty (26

June 2009), Treaties & Models IBFD, and the Australia-Japan Income Tax Treaty (1 Jan. 2009), Treaties & Models IBFD, which both specify a 7-year time limit

for transfer pricing adjustments.

97. Broadly, a 7-year limitation period also applies to the DPT; see sec. 145-10, sch. 1 TAA 1953.

98. Division 815 Income Tax (Transitional Provisions) Act 1997 (Cth).

99. AU: FCA, 19 Apr. 1989, 161, Commissioner of Taxation v. Citibank Ltd; AU: HCA, 21 Dec. 1999, 67, Esso Australia Resources v. Federal Commissioner of

Taxation; AU: FCAFC, 12 May 2004, 122, Pratt Holdings Pty Ltd v. Commissioner of Taxation; Evidence Act 1995 secs. 118 and 119.

100. ATO, Our Approach to Information Gathering – Accountants’ concession, available at https://www.ato.gov.au/About-ATO/Commitments-and-reporting/In-detail/

Privacy-and-information-gathering/Our-approach-to-information-gathering/?page=51 (accessed 12 July 2023).

101. For example, see the Australian Financial Review, ATO calls out 'reckless and false' legal privilege claims in tax avoidance cases (4 Jan. 2019), available at

https://www.afr.com/news/politics/ato-calls-out-reckless-and-false-legal-privilege-claims-in-tax-avoidance-cases-20190104-h19psh (accessed 12 July 2023).

102. AU: HCA, 17 Apr. 2019, 82, Glencore International AG & Ors v. Commissioner.

103. AU: HCA, 14 Aug. 2019, 26, Glencore International AG v. Commissioner of Taxation, at paras. 21-26.

S. Grieve, Australia - Transfer Pricing & Dispute Resolution, Country Tax Guides IBFD (accessed 2 August 2023). 15

© Copyright 2023 IBFD: No part of this information may be reproduced or distributed without permission of IBFD.

Disclaimer: IBFD will not be liable for any damages arising from the use of this information.

Exported / Printed on 22 Nov. 2023 by Maria.L.Rojas@ar.ey.com.

Australia - Transfer Pricing & Dispute Resolution - Country Tax Guides (Last Reviewed: 31 May 2023)

Court observed that once privileged communications have been disclosed, a taxpayer that wishes to prevent the use of those

communications will need to rely on the equitable doctrine of breach of confidence.[104]

The use of legal professional privilege during reviews and audits has been identified as a focus area for the ATO’s Tax Avoidance

Taskforce.[105]

In early 2022, the Federal Court handed down its much-anticipated judgment in the PricewaterhouseCoopers case. This case

appears to be one of the first cases resulting from the ATO’s increased focus on legal professional privilege claims. The case

concerned an action by the Commissioner to challenge claims for privilege made by PricewaterhouseCoopers, a multi-disciplinary

practice (broadly, a practice comprising both lawyers and non-lawyers) and its client. The claims were made in response to formal

notices to produce documents issued to PricewaterhouseCoopers by the Commissioner. The Commissioner was unsuccessful in

arguing that, either as a matter of form or substance, there was no lawyer-client relationship between PricewaterhouseCoopers

and its client sufficient to ground a claim for privilege.

Justice Moshinsky found that:

In my view, as a matter of form, the Statements of Work do establish a relationship of lawyer and client sufficient to be able

to ground a claim for legal professional privilege. The key features of the Statements of Work have been summarised at

[89] above. Each Statement of Work identifies the client, the [Australian Legal practitioners (ALPs)] who are to provide the

services, the [Non legal practitioners] who will assist the ALPs in the provision of those services, and describes the services

to be provided as legal services. The identified ALPs are lawyers qualified such as to be capable of being in a lawyer and

client relationship which gives rise to privileged communications.[106]

and