Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Coventry Grid For Adults

Uploaded by

Aliens-and-antsOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Coventry Grid For Adults

Uploaded by

Aliens-and-antsCopyright:

Available Formats

The Coventry Grid for adults: a tool to guide clinicians in differentiating complex trauma and autism

The Coventry Grid for adults: Address for

correspondence

a tool to guide clinicians E-mail: charlotte.cox@

merseycare.nhs.uk

in differentiating complex

Acknowledgements

trauma and autism The authors would like

to thank Heather Moran

for her support and

Charlotte Cox, Erin Bulluss, Frank Chapman, Alex Cookson,

encouragement and

Andrea Flood and Anna Sharp, Merseyside, UK and Australia

Georgia Fair for her advice

and information regarding

Editorial comment sensory processing

difficulties. We are also

In this paper, the authors discuss the need for an instrument to help distinguish between grateful to Antonella

autism and the effects of complex trauma in the diagnostic assessment of adults. They Brunetti, Piet Crosby, Peter

chose to adapt the Coventry Grid (Moran, 2010) for this purpose and developed the Dargan, Dougal Hare, Clare

Coventry Grid for Adults (CGA). It is widely accepted that autism presents differently in Holmes, Lyndsey Holt and

each individual with the diagnosis and so too in trauma. Diagnostic assessment tools Guido Sijbers for reviewing

are necessarily limited in that they have to use general descriptors and can not account the items of the CGA.

for every individual seen with the condition. There is also often a focus on difficulties and The authors have declared

a tendency to view difference as a deficit, when such differences can convey strengths no conflict of interest.

and/or may not be viewed as a problem by the person concerned. The authors acknowl- This research did not

edge that the CGA is in its infancy and welcome feedback from readers. receive any funding.

Introduction

Identification of autism in adulthood is not always straight- whether they may be autistic, and requested formal

forward. Many traits characteristic of autism can also assessment. The interactions between autism, poor

indicate a complex trauma (CT) history. In fact, the devel- attachment and vulnerability to trauma mean that there

opmental impact of early trauma in some institutionalised will also be a group of people who have both autism

babies has so clearly mirrored autism that it has been and CT (Perry and Flood, 2016).

considered a type of ‘quasi-autism’ (Rutter et al, 1999).

Like autism, CT is usually experienced as pervasive and Diagnostic criteria for autism specifically require that

can have a lifelong impact on an individual (Van Der Kolk, difficulties cannot be explained by ‘another mental dis-

2014). It is often unclear whether a person’s difficulties order’, acknowledging that the same symptoms could

should be best understood through the lens of autism have different origins (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual

or CT or both (Lai and Baron-Cohen, 2015). of Mental Disorders, 2013). Accordingly, gold standard

diagnostic tools, such as the Diagnostic Interview for

A significant number of adults are thought to have undi- Social and Communication Disorders (DISCO; Wing,

agnosed autism, many of whom have been mistakenly Leekam, Libby, Gould and Larcombe, 2002) and the

understood as experiencing mental health problems Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS-2;

(Lai and Baron-Cohen, 2015). Concurrently, individu- Gotham, Risi, Pickles and Lord, 2007), should be used

als with a history of feeling different from others and as a part of a comprehensive assessment undertaken

struggling to manage social interaction have queried by experienced clinicians who can also rule out other

76 GAP,20,1, 2019

GAP_text_Spring_2019.indd 76 29/05/2019 10:17

The Coventry Grid for adults: a tool to guide clinicians in differentiating complex trauma and autism

reasons for the development of apparently autistic adult services using the Coventry Grid in its original

traits (see National Institute for Clinical Excellence form. Given the Coventry Grid is a tool designed for

guideline 142, 2012). Despite the increasing commit- understanding difficulties in children, this approach

ment to comprehensive assessments, diagnosis is not has obvious limitations. The authors therefore used the

always clear cut, with clinicians sometimes practising Coventry Grid as a starting point to develop an equiva-

diagnostic ‘upgrading’ when there is a lack of clarity lent tool for use in adult services, The Coventry Grid for

(Rogers, Goddard, Hill, Henry and Crane, 2016). Adults (CGA), see Appendix 1.

The authors acknowledge and do not dispute estab- The Coventry Grid for Adults (CGA)

lished arguments against the usefulness of diagnostic Like the original Coventry Grid, the CGA was developed

labels (eg Bentall, 2006). That said, we believe that by a group of interested clinicians working in services

disentangling autism from experiences of trauma (or supporting people with autism and/or complex trauma.

recognising where both are present) is important, not The group was made up of Clinical Psychologists and

because of any inherent value in giving a person the a Speech and Language Therapist, all of whom had at

correct label(s), but to develop a better understanding least two years’ post qualification experience in these

of the person and the origins of their difficulties. From fields and were trained in the administration of at least

a good formulation follows the best person centred one of the gold standard tools for the assessment of

support, treatment or management plan (Johnstone autism (eg DISCO or ADOS). The initial working group

and Dallos, 2013). mostly comprised clinicians employed by Mersey Care

NHS Foundation Trust, a mental health trust in North

Where CT and autism are misdiagnosed, this can have West England, but also included a Clinical Psychologist

negative implications for both the person themselves from Adelaide, Australia who attended meetings via

and also on the systems that support them. Someone Skype and a Clinical Psychologist working for the

with autism understood to have CT, or vice versa, may University of Liverpool Doctorate in Clinical Psychology

find themselves poorly understood by themselves and training programme.

others, and could therefore be offered inappropriate

support or interventions. Accurate identification of The children’s Coventry Grid contrasted autism with

autism, for example, allows the clinician to adapt their attachment problems, which it defined as “all kinds of

therapeutic approach to increase suitability for the significant attachment difficulties, severe enough to

autistic individual (eg Bulluss, 2019; Gaus, 2011), facil- affect the ability to develop mutually supportive rela-

itating treatment responsivity. When interventions are tionships with family and friends”. The CGA is designed

not effectively tailored and likely to lead to an improve- to map onto how these difficulties might manifest in

ment in well-being, an individual may be apportioned adulthood, however the term complex trauma has

blame or dismissed as being ‘non-compliant’, which been used as this is a widely accepted term capturing

can serve to maintain or exacerbate distress. the adult experience of attachment difficulties while

avoiding the pitfalls of diagnostic categories such as

The Coventry Grid Borderline Personality Disorder.

The problem of disentangling autism and CT has begun

to be addressed in children’s services, most notably The first step involved reviewing each item of the

with the Coventry Grid (Moran 2010; 2015; see also Coventry Grid and agreeing whether or not it could be

Flackhill, James, Soppitt and Milton, 2017). This is a usefully applied to an adult population, or whether it

tool developed to assist professionals in noticing the needed amending or deleting. As individual items were

often subtle differences between children on the autism reviewed, it became clear that some broader sections

spectrum and those with attachment difficulties. There and their titles also required amending or deletion (for

is no equivalent tool for working with adults, although example, an item was added pertaining to forming and

the authors have anecdotal evidence of clinicians in maintaining intimate relationships).

GAP,20,1, 2019 77

GAP_text_Spring_2019.indd 77 29/05/2019 10:17

The Coventry Grid for adults: a tool to guide clinicians in differentiating complex trauma and autism

Existing networks and a conference presentation were Like the CG, the CGA does not distinguish between

used to invite interested professionals with two or more attachment styles and therefore the range of CT present-

years’ post qualification experience working with these ations. In particular, it may not be sensitive to an

populations to assist in reviewing the CGA. Prior to anxious avoidant pattern, where some behavioural

review, the draft grid was amended so that the pro- features may mirror those commonly associated with

posed ‘Autism’ and ‘CT’ items were mixed together and autism (Mackenzie and Dallos, 2017).

randomly listed under the section headers. Reviewers

were asked to indicate whether each item was likely As yet, the CGA remains an unvalidated tool with items

to be a feature of autism, CT or both. Seven reviewers assembled through the anecdotal experience of clini-

provided feedback which was used to refine the grid, cians. There is a potential weakness in relation to the

with a number of items removed or adapted where formulation of items, in that the overall experience and

there was a lack of consensus, or the items did not post qualification training within the group was skewed

reliably differentiate autism from CT. in favour of autism. While all members of the group had

been trained in at least one formal diagnostic tool for

Purpose of the CGA autism and had clinical experience working with CT,

Like the original Coventry Grid, the purpose of the CGA only one person had been trained to administer a struct-

is to assist qualified clinicians to better understand indi- ured assessment of attachment relationships. This

viduals who present with difficulties common to both perhaps reflects the relative emphasis on formulation

autism or CT, enabling more refined assessments for over diagnosis in CT.

those individuals and informing multidisciplinary team

discussions. The CGA is not intended to be used as a In addition, although over 100 experienced clinicians

checklist, and it should not be used in isolation from were invited to participate in the review process, many

other formulation work with an individual. reported insufficient confidence in their knowledge of

autism and CT to do so and only seven were eventually

Limitations of the CGA involved. This smaller than anticipated number speaks

Whilst the CGA is not a diagnostic tool, the very act of to the need for the development of a tool to support

grouping experiences and behaviours into two relatively clinicians in this complex area.

broad categories means that important subtleties may

be lost. Further, the focus of the CGA on ‘difficulties’ Concluding comments

is inherently aligned with a problem focused approach The CGA is a working document and we plan to continue

to working, even if the explicit intention is to use it to to improve it based on feedback. Further work is required

increase understanding. to develop its sensitivity to a broader range of attach-

ment styles. Future research will investigate the useful-

Autism is experienced and observed in an enormous ness of the CGA to both clinicians and the individuals

variety of ways, and this may be especially true in adult- who have been assessed using the CGA. There is

hood when individuals have developed idiosyncratic also scope to explore the link between the behavioural

ways of managing their differences (Lai and Baron- observations and the functions underpinning these.

Cohen, 2016). In addition, autism and CT may have

different presentations in men and women (Trubanova,

Donlon, Kreiser, Ollendick and White, 2014) which the

CGA is not able to directly address. However, it may

be that the CGA is indirectly useful here, for example

helping to correct the disproportionate misdiagnosis

of Borderline Personality Disorder in autistic women

(Trubanova et al, 2014).

78 GAP,20,1, 2019

GAP_text_Spring_2019.indd 78 29/05/2019 10:17

The Coventry Grid for adults: a tool to guide clinicians in differentiating complex trauma and autism

References

American Psychiatric Association (2013) Diagnostic and Moran, H (2015) The Coventry Grid 2 available from

statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th edition, Arlington, http://drawingtheidealself.co.uk/index.php?p=1_7

VA: American Psychiatric Publishing. (accessed 25 February 2019).

Bentall, R (2006) Madness explained: why we must reject National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2012)

the Kraepelinian paradigm and replace it with a ‘complaint- Autism spectrum disorder in adults: diagnosis and

orientated’ approach to understanding mental illness management (Nice clinical guideline 142) available

Medical Hypotheses 66 (2) 220-233. from https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg142/chapter/

Introduction.

Bulluss, E K (2019) Modified schema therapy as

a needs-based treatment for complex comorbidities Perry, E and Flood, A (2016) Autism spectrum disorder

in adults with autism spectrum conditions and attachment: clinician’s perspective in H Fletcher,

Australian Clinical Psychologist 1, 1–7. A Flood and Hare, E (eds) Attachment in intellectual

and developmental disability: a clinician’s guide to

Flackhill, C, James, S, Soppitt, R and Milton, K (2017) practice and research Malden: Wiley Blackwell.

The Coventry Grid Interview (CGI): exploring autism

and attachment difficulties Good Autism Practice Rogers, C L, Goddard, L, Hill, E L, Henry, L A and

Journal 18 (1) 62–80. Crane, L (2016) Experiences of diagnosing autism

spectrum disorder: a survey of professionals in the

Gaus, V L, (2011) Cognitive behavioural therapy for adults United Kingdom Autism 20 (7) 820–831.

with autism spectrum disorder Advances in Mental Health

and Intellectual Disabilities 5 (5) 15–25. Rutter, M, Andersen-Wood, L, Beckett, C, Bredenkamp,

D, Castle, J, Groothues, C and O’Connor, T G (1999)

Gotham, K, Risi, S, Pickles, A and Lord, C (2007) Quasi-autistic patterns following severe early global

The Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule: revised privation Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry

algorithms for improved diagnostic validity Journal and Allied Disciplines 40 (4) 537–549.

of Autism and Developmental Disorders 37, 613–627.

Trubanova, A, Donlon, K, Kreiser, N L, Ollendick, T H and

Johnstone, L and Dallos, R (2013) Formulation in White, S W (2014) Under-identification of ASD in females:

psychology and psychotherapy: making sense of a case series illustrating the unique presentation of ASD

people’s problems, London: Routledge. in young adult females Scandinavian Journal of Child and

Adolescent Psychiatry and Psychology 2 (2) 66–76.

Lai, M C and Baron-Cohen, S (2015) Identifying the lost

generation of adults with autism spectrum conditions Van der Kolk, B (2014) The body keeps the score:

The Lancet Psychiatry 2 (11) 1013–1027. mind, brain and body in the transformation of trauma

London: Penguin.

McKenzie, R and Dallos, R (2017) Autism and

attachment difficulties: overlap of symptoms, Wing, L, Leekam, S R, Libby, S J, Gould, J and Larcombe,

implications and innovative solutions Clinical Child M (2002) The Diagnostic Interview for Social and

Psychology and Psychiatry 22 (4) 632–648. Communication Disorders: background, inter‐rater

reliability and clinical use Journal of Child Psychology

Moran, H (2010) Clinical observations of the differences and Psychiatry 43 (3) 307–325.

between children on the autism spectrum and those

with attachment problems: The Coventry Grid

Good Autism Practice Journal 11 (2) 46–59.

GAP,20,1, 2019 79

GAP_text_Spring_2019.indd 79 29/05/2019 10:17

The Coventry Grid for adults: a tool to guide clinicians in differentiating complex trauma and autism

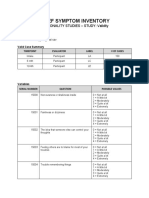

Appendix 1: The Coventry Grid for adults: a tool to guide clinicians

in disentangling complex trauma and autism

Please note: The purpose of this tool is to assist qualified clinicians to better understand individuals who

present with difficulties common to both autism or complex trauma, enabling more refined assessments for those

individuals and to inform multidisciplinary team discussions. The CGA is not intended to be used as a checklist,

and it should not be used in isolation from other formulation work with an individual.

1 Inflexible thinking and behaviour

People with autism and people with significant attachment difficulties (here termed Complex Trauma, CT)

present with difficulties with flexible thinking and behaviour. This can present as behaviours which are demanding, .

Presentation Autism Complex trauma (CT)

observed in both

1.1 Preference for predictability in daily life

a. Repetitive questions related to own i Looks forward to new experiences

focused interests. but may not manage the emotions

they provoke (eg may not cope

with excitement or disappointment).

b. Ritualised greetings (including specific ‘scripts’ ii Seeks to keep relationships

for ‘small talk’). close, driven by fear that changes

in caring behaviour indicates

potential for abandonment.

c. Becomes anxious if routine is removed

and may seek to impose usual routine

(eg difficulties transitioning between work

and holidays; becoming distressed if usual

appointment times are changed).

d. Inclined to try to repeat experiences and

therefore day to day repetition becomes

routine (eg becomes distressed if asked

to sit somewhere else in a work office).

e. Distressed when a routine cannot be

completed (eg when cannot follow the

usual route because of road works).

f. Adhering to strict and inflexible routines,

and possibly becoming distressed when

these are disrupted. (eg categorising and

organising household items: ‘everything

has its place’. Refusal to let others in

household use certain items).

80 GAP,20,1, 2019

GAP_text_Spring_2019.indd 80 29/05/2019 10:17

The Coventry Grid for adults: a tool to guide clinicians in differentiating complex trauma and autism

Presentation Autism Complex trauma (CT)

observed in both

1.2 Difficulties with eating

a. Limits foods eaten according to unusual criteria i Aversion to specific foods due

such as texture (sensory), shape, colour, brand, to textures, tastes etc. which

situation, rather than what that food is (eg will trigger traumatic memories.

eat chicken nuggets but not chicken, will only

eat Fray Bentos steak pies). May also become

distressed if packaging changes.

b. Food neophobia, showing fear for new foods, ii Person describes binge

causing a very limited diet. eating and restrictive eating

as comfort seeking, gaining a

c. Preferences for standardised/processed foods sense of control, and coping

related to their predictable nature. with emotional stimuli. Eating

difficulties may fluctuate

depending on emotional state.

1.3 Repetitive use of language

a. Immediate/delayed echolalia. This can be i Uses repeated phrases in

repeating what a communication partner has close relationships (eg ‘I can’t

said, or in the form of stereotyped language bear it anymore’) expecting

(eg speaking in quotes from books or movies). predictable responses from

others (eg ‘I’m here for you’).

b. Repetition of ‘favoured’ words which are chosen ii Language used to elicit caring

for their sound or shape, rather than for their use response from others but is not

in communication or emotional content. experienced as a comforter in

its own right.

c. Uses formal, pedantic or inappropriate language.

This may be in context but also may be using

words/phrases the person does not understand.

1.4 Unusual relationship with possessions

a. Makes collections of objects. i Interested in showing

possessions to others and

Collections often carefully arranged gaining a response, including

(eg alphabetised). social approval or envy.

b. Has a collection of items (that may or may ii Ambivalent attachment

not be socially appropriate) and does not seek relationships with objects:

social approval for the collection or for its care. may deliberately destroy

emotionally significant

possessions when angry.

c. Will often be able to say where most treasured iii Hoards items due to previous

possessions are and recognise if they are moved. experiences of deprivation

or loss.

d. Preference for certain belongings due to sensory

features (eg crystal glass figures).

e. Hoards items due to inability to discriminate

between useful and useless items.

GAP,20,1, 2019 81

GAP_text_Spring_2019.indd 81 29/05/2019 10:17

The Coventry Grid for adults: a tool to guide clinicians in differentiating complex trauma and autism

2 Intense and restricted interests

Adults with both autism and CT often display patterns of intense and restricted interests. In childhood, this may have

been most evident in the way they played (for example lining up toys or struggling to engage in imaginative play).

As adults, this may manifest itself in choice of hobbies and behaviour in informal social situations.

Presentation Autism Complex trauma (CT)

observed in both

2.1 Unusual choice of hobbies or interests

a. Preference for logical, predictable interests i Choice of interests often linked

(eg train timetables, stamp collecting). with specific group identities

(eg music scenes, tattooing).

Sudden change in interest

appears to be related to

unstable sense of identity.

b. Collects facts rather than showing interest in ii Intense interest may relate

more general aspects (eg knows football scores to a personal experience, an

but does not show a real interest in the match). emotional weighted event or

an interpersonal relationship

(positive or negative).

2.2 Social interaction related to interests

a. Prefers to pursue interests alone, or only i Quickly forms friendships

alongside others, in a parallel fashion. or sense of belonging with

others who share the same

interest. Interest could be

superficial.

b. Where interests are pursued in groups this ii Creates an ideal self through

tends to be in settings with clear social rules emulating an idealised other’s

that may have been taught (eg going out for interests.

a meal, role play).

c. Even when interests are shared, discusses

own knowledge, rather than gaining knowledge

from others and will rarely ask others for their

opinion on interest.

82 GAP,20,1, 2019

GAP_text_Spring_2019.indd 82 29/05/2019 10:17

The Coventry Grid for adults: a tool to guide clinicians in differentiating complex trauma and autism

3 Social interaction/communication

There are key similarities in social interaction/communication: people with autism and CT tend to have an

egocentric style of relating to other people and lack awareness of the subtle variations in social interaction

which are necessary to develop successful relationships with a range of other people.

Presentation Autism Complex trauma (CT)

observed in both

3.1 Difficulties with social interaction

a. Lacks awareness of the needs of the audience; i Hyper-vigilant and overly

lack of attunement and reciprocity in social sensitive to tone of voice, volume

interaction (eg does not turn take). and stance of communication

partner; person may appear to

be hyper-vigilant to any potential

emotional rejection.

b. Does not knowingly influence others emotionally ii No difficulties initiating

except through angry outbursts (eg would rarely conversation (unless in an

ingratiate self with audience). emotional aroused state).

c. Does not vary eye contact with emotional state, iii Eye contact affected by

though may still vary at times (eg when effort put emotional state.

in to make eye contact).

d. Attempts a logical approach to social

interactions (eg rote understanding of

body language).

e. Person assumes prior knowledge of

communication partner (eg limited Theory

of Mind). Does not start conversations by

addressing the person/context but starts with

the subject matter.

f. Proximity to others might be unrelated to desire

to interact socially (eg close proximity may not

signal an intimacy or desire for contact).

GAP,20,1, 2019 83

GAP_text_Spring_2019.indd 83 29/05/2019 10:17

The Coventry Grid for adults: a tool to guide clinicians in differentiating complex trauma and autism

Presentation Autism Complex trauma (CT)

observed in both

3.2 Difficulty interacting in a group setting

a. Lacks awareness of the social expectation of i Feels anxiety that other members

sharing (eg sharing talking time/turn taking of the group are not safe.

when interacting in groups).

b. One-sided social approaches. ii Hyper-alert to any indications of

threat from others, and seen by

others to ‘over-react’ to these.

This could include behaving

in a hostile way, withdrawing,

or making special efforts to

ingratiate self with others.

c. Laughs at jokes but does not understand iii Patterns of social relationships

why they are funny or laughs at the wrong time. develop to meet emotional

Misses subtle or unexpected verbal or needs, either with attempts to

contextual associations. please others or keep others

at a distance.

d. Manages well in highly structured social iv ‘Assigns’ others (eg

interactions (eg appointments). professionals) to roles which

are familiar to their own past

experience of relationships

(presenting as transference).

e. Struggles to keep up with fast moving subtle v Initiates interactions with others

interactions (eg sarcasm, body language). which allow them frequently

to play the same role in relation

to self (eg as the victim, as

the bully).

3.3 Difficulties in intimate relationships

a. Difficulties understanding what makes others feel i Pattern of seeking out attachment

loved and appreciated (eg only buys practical and then withdrawing and

presents). rejecting attachment figures.

b. Struggles to understand social rules of ii Expectation that others will be

relationships. May become fixated on others abusive and punitive.

while unaware or unconcerned that feelings are

not reciprocated.

iii Hyper-alertness to threats within

a relationship and perceived

threat of abandonment in intimate

relationships.

84 GAP,20,1, 2019

GAP_text_Spring_2019.indd 84 29/05/2019 10:17

The Coventry Grid for adults: a tool to guide clinicians in differentiating complex trauma and autism

4 Mentalising/theory of mind

People with autism and CT often have difficulties with mentalising/theory of mind. This refers to both the ability to see

the thoughts/perspective of others; to recognise that this may differ from their own; and to read others’ intentions.

Presentation Autism Complex trauma (CT)

observed in both

4.1 Difficulty appreciating others’ views and thoughts

a. Rarely refers to the views of others. i Efforts to feel safe by influencing

social interactions and evoke

desired emotional responses in

others. This may be perceived

as controlling.

b. Uses logic or rules to work out others’ intentions. ii Overly compliant and ingratiates

self with others in order to feel safe.

c. Fails to take into account how others will feel iii Acutely interested in others’

when making decisions about behaviours. thoughts or views but ability

to accurately assess these is

d. Fails to acknowledge or offer comfort when disrupted by schemas (eg early

someone has been hurt. experiences leading to the belief

‘I am unlovable’ result in suspicious

e. Obsessively reviews previous interactions and interpretation of loving behaviours).

applies logical thought patterns to previous events.

4.2 Lack of appreciation of how others may see them

a. Has unusual logic or lack of awareness about i Avoids personal responsibility by

personal responsibility (eg fail to take responsibility blaming others for own mistakes,

for unintentional mistakes). but fails to take into account

context, others’ perspectives,

others’ knowledge of events, or

the consequences of avoiding

responsibility, regardless of impact

on people or relationships.

b. May lack awareness of others’ views of self, ii Tries to shape others’ views of self

including lack of awareness of ‘visibility’ of own by biased or exaggerated reporting

difficulties. in line with social conventions.

c. Does not appreciate need for social convention

to elicit positive response and view of themselves

from others (eg responds to someone’s new hair

cut by telling them they don’t suit it).

4.3 Problems distinguishing between fact and fiction, blurring of boundaries

a. Does not place value on the distinction between i Unable to judge whether a threat

people and objects, fictional characters or events is realistic. Acts as if all threats,

(although may recognise the latter are not ‘real’). however minor or unrealistic,

need to be defended against.

b. Poor at fabrication or ‘white lies’, rather misrepresent- ii Fabrications may be elaborate and

ation may occur due to difficulties understanding also may deliberately be harmful to

and communicating multiple perspectives. others’ reputations.

GAP,20,1, 2019 85

GAP_text_Spring_2019.indd 85 29/05/2019 10:17

The Coventry Grid for adults: a tool to guide clinicians in differentiating complex trauma and autism

5 Emotional regulation

People with autism and CT often struggle to regulate their emotions. What is often termed a ‘meltdown’ in autism,

looks very similar to some of the extreme experiences of emotion observed in people with CT.

Presentation Autism Complex trauma (CT)

observed in both

5.1 Difficulties managing own emotions

a. Affective instability is not primarily in i Responds to others by expressing and

response to relationships, although may rapidly switching between intense emotions

be in response to aspects of relationships (eg love, distress and anger).

(eg a change in others behaviour).

b. Can define feelings or experiences but ii Prone to exhibiting extreme emotional

not in terms of emotional content. May use responses to others known for a short

metaphorical or idiosyncratic definitions of time period.

emotions, sometimes related to a specific

interest. iii ‘Accelerates’ personal/intimate relationships;

prone to experiencing quick ‘turnarounds’ in

personal/intimate relationships.

iv Affective instability is predominantly related

to social context and relationships.

5.2 Difficulty appreciating others’ emotions

a. Explains social relationships/interactions i Acutely sensitive to changes in others

and interpersonal relationships in more of emotional state with a tendency to perceive

a logical/analytical manner or as related these as meaningful to themselves. Hyper

to their own interests (eg an interest in vigilant with regard to particular emotions

crime or politics would be used to explain in others (eg anger, distress, approval) and

how a person can influence another often makes reference to these states.

person’s behaviours).

5.3 Unusual mood patterns

a. Sudden mood change in response to i Sudden mood changes may relate to

external information such as change in internal states (eg to PTSD, flashbacks)

the environment, miscommunication or and perceived emotional demands.

sensory information.

b. Sudden mood changes in response to a ii Sudden mood changes in response to a

perceived injustice occur primarily when perceived injustice occur primarily when

strict personal rules are perceived to have feeling personally slighted, attacked,

been violated. targeted or victimised.

5.4 Inclined to sudden extreme anxiety

a. Extreme anxiety responses around any i Extreme anxiety as a response to not having

changes to routines or to the sudden perceived needs met (especially comfort,

introduction of unexpected or novel attention, being held in mind). Belief that

experiences. unmet needs reflect own deficiencies/that

others do not care.

86 GAP,20,1, 2019

GAP_text_Spring_2019.indd 86 29/05/2019 10:17

The Coventry Grid for adults: a tool to guide clinicians in differentiating complex trauma and autism

6 Executive functioning

Difficulties with executive functioning have been observed in both autism and CT.

Presentation Autism Complex trauma (CT)

observed in both

6.1 Unusual memory

a. Presents with deficits in memory i Presents as ‘fixated’ on certain events but

specifically related to interest level struggles to see how these relate to previous

(eg difficulty remembering events experience of personal trauma or injustice.

or stimuli that are not of interest).

b. Exceptional long term memory abilities; ii Recall of events may fluctuate, appear

may demonstrate the ability to recall confused or change according to the

excessive detail for areas of particular audience.

interest. Is likely to be able to recall to the

same degree regardless of audience.

c. Less well developed/impaired iii Recall of negative memories may be

autobiographical memory processes. selective in terms of the content.

6.2 Difficulty with concept of time – limited intuitive sense of time

a. Strong preference for the use of precise i Time has an emotional significance for the

times and/or heavy reliance on external person (eg waiting a long time for someone

timekeeping (eg uses watch and is to arrive is quickly associated with a feeling

unable to guess the time). of emotional neglect and rejection).

6.3 Weak central coherence

a. Inclined to consider all the information i Presents with an ‘emotional bias’ which

relating to a situation, and have difficulty then may lead them to omit and/or focus

sorting relevant from irrelevant details on certain elements of a situation (eg the

to understand how events unfolded. person’s attention may be drawn to elements

Therefore recounting events or life history of a situation which hold an emotional

may be overly detailed and tangential, significance to them).

without a clear ‘storyline’.

GAP,20,1, 2019 87

GAP_text_Spring_2019.indd 87 29/05/2019 10:17

Copyright of Good Autism Practice is the property of British Institute of Learning Disabilities

and its content may not be copied or emailed to multiple sites or posted to a listserv without

the copyright holder's express written permission. However, users may print, download, or

email articles for individual use.

You might also like

- Maladaptive Coping Modes Perfectionistic OvercompensatorDocument2 pagesMaladaptive Coping Modes Perfectionistic OvercompensatorMArkoNo ratings yet

- Causes and Risk Factors For Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity DisorderDocument8 pagesCauses and Risk Factors For Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity DisorderFranthesa LayloNo ratings yet

- Y Bocs Information SampleDocument2 pagesY Bocs Information SampledevNo ratings yet

- A Filled-In Example: Schema Therapy Case Conceptualization FormDocument10 pagesA Filled-In Example: Schema Therapy Case Conceptualization FormKarinaNo ratings yet

- Emdr 2002Document14 pagesEmdr 2002jivinaNo ratings yet

- Adult Attachment ScaleDocument10 pagesAdult Attachment ScaleSasu NicoletaNo ratings yet

- 2 - Diagnostic Evaluation of Autism Spectrum DisordersDocument9 pages2 - Diagnostic Evaluation of Autism Spectrum DisordersAlice WernecNo ratings yet

- DSM 5 Intellectual Disability Fact SheetDocument2 pagesDSM 5 Intellectual Disability Fact SheetMelissa Ortega MaguiñaNo ratings yet

- Interrupting Internalized Racial Oppression - A Community Based ACT InterventionDocument5 pagesInterrupting Internalized Racial Oppression - A Community Based ACT InterventionLINA MARIA MORENONo ratings yet

- Writing Clinical DocumentsDocument13 pagesWriting Clinical DocumentshotumaNo ratings yet

- Adhd - Asrs .ScreenDocument4 pagesAdhd - Asrs .ScreenKenth GenobisNo ratings yet

- Scales For BIpolar DisorderDocument14 pagesScales For BIpolar DisorderDivia RainaNo ratings yet

- The Investigation and Differential Diagnosis of Asperger Syndrome in AdultsDocument9 pagesThe Investigation and Differential Diagnosis of Asperger Syndrome in AdultsamarillonoexpectaNo ratings yet

- MBT I ManualDocument42 pagesMBT I ManualMauroNo ratings yet

- CatDocument12 pagesCatnini345No ratings yet

- Spirito MC10 PDFDocument147 pagesSpirito MC10 PDFlabebuNo ratings yet

- Life-Enhancing Belief Statements: T H S ADocument11 pagesLife-Enhancing Belief Statements: T H S AA.G. Bhat0% (1)

- YES NO: Does The Client Consent To An Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) Assessment?Document1 pageYES NO: Does The Client Consent To An Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) Assessment?aspire centerNo ratings yet

- Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) As A Career Counseling StrategyDocument17 pagesAcceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) As A Career Counseling Strategydavid.settembrinoNo ratings yet

- Solution Focused Brief TherapyDocument7 pagesSolution Focused Brief TherapyBogdanŁapińskiNo ratings yet

- MSE and History TakingDocument17 pagesMSE and History TakingGeetika Chutani18No ratings yet

- Trauma Focused CBT ArticleDocument14 pagesTrauma Focused CBT ArticleClaudiaNo ratings yet

- Final Group Counseling Project - Stress ManagementDocument82 pagesFinal Group Counseling Project - Stress Managementapi-548101945No ratings yet

- Schema Modes ArntzDocument10 pagesSchema Modes ArntzMónica SobralNo ratings yet

- Modified Coventry Model - Including PDA ProfileDocument13 pagesModified Coventry Model - Including PDA ProfileAliens-and-antsNo ratings yet

- Modified Coventry Model - Including PDA ProfileDocument13 pagesModified Coventry Model - Including PDA ProfileAliens-and-antsNo ratings yet

- EFT Cheat Sheet-2Document1 pageEFT Cheat Sheet-2donnalinNo ratings yet

- Traumatic Bereavement Clinical Guide v02 UKTCDocument154 pagesTraumatic Bereavement Clinical Guide v02 UKTCPraneeta KatdareNo ratings yet

- 1983 - The Brief Symptom Inventory, An Introductory ReportDocument11 pages1983 - The Brief Symptom Inventory, An Introductory ReportBogdan BaceanuNo ratings yet

- Afifi and Reichert 1996Document12 pagesAfifi and Reichert 1996Farva MoidNo ratings yet

- Quotes by Maria MontessoriDocument6 pagesQuotes by Maria MontessoriIqra Montessori100% (1)

- Coventry Grid Interview (CGI)Document20 pagesCoventry Grid Interview (CGI)Aliens-and-antsNo ratings yet

- Focus Group PrinciplesDocument6 pagesFocus Group PrinciplesColliers2011No ratings yet

- Theories of Counseling Object Relations TheoryDocument18 pagesTheories of Counseling Object Relations TheoryYoga UpasanaNo ratings yet

- From Client Process To Therapeutic RelatingDocument15 pagesFrom Client Process To Therapeutic RelatingjeanNo ratings yet

- Altman Self Rating ScaleDocument2 pagesAltman Self Rating ScaleRifkiNo ratings yet

- (The Basics Series) Ruth O'Shaughnessy, Katherine Berry, Rudi Dallos, Karen Bateson - Attachment Theory - The Basics (2023, Routledge) - Libgen - LiDocument255 pages(The Basics Series) Ruth O'Shaughnessy, Katherine Berry, Rudi Dallos, Karen Bateson - Attachment Theory - The Basics (2023, Routledge) - Libgen - LiGergely Bereczki100% (1)

- Crittenden - Attachment and Cognitive PsychotherapyDocument11 pagesCrittenden - Attachment and Cognitive PsychotherapyJVolasonNo ratings yet

- Measuring Adult AttachmentDocument8 pagesMeasuring Adult AttachmentLisaDarlingNo ratings yet

- Case Analysis Case Study HelgaDocument10 pagesCase Analysis Case Study Helgaapi-487413988No ratings yet

- 2022-2023 Trauma Informed Care Microcredential Information BookletDocument12 pages2022-2023 Trauma Informed Care Microcredential Information Bookletapi-260883031100% (1)

- Zero To Three Slade Perinatal Mental Health 7 Pgs PDFDocument7 pagesZero To Three Slade Perinatal Mental Health 7 Pgs PDFCata UndurragaNo ratings yet

- The Overexcitability Questionnaire-Two (OEQII) - Manual, Scoring ...Document8 pagesThe Overexcitability Questionnaire-Two (OEQII) - Manual, Scoring ...Luiz CavalcantiNo ratings yet

- Coventry Grid Version 2 - Jan 2019 PDFDocument13 pagesCoventry Grid Version 2 - Jan 2019 PDFDavidLee100% (1)

- Test Bank For Leadership Theory Application and Skill Development 6th Edition LussierDocument53 pagesTest Bank For Leadership Theory Application and Skill Development 6th Edition Lussiera204491073No ratings yet

- MBA Assignment ExampleDocument21 pagesMBA Assignment ExampleZamo Mkhwanazi75% (4)

- Shame ErskineDocument17 pagesShame ErskineSonja SudimacNo ratings yet

- Manual For The Cognitive Therapy Rating Scale For Children and AdolescentsDocument22 pagesManual For The Cognitive Therapy Rating Scale For Children and AdolescentsAlberto EstradaNo ratings yet

- Psychosocial Dimensions of Displacement: Prevalence of Mental Health Outcomes and Related Stressors Among Idps in IraqDocument34 pagesPsychosocial Dimensions of Displacement: Prevalence of Mental Health Outcomes and Related Stressors Among Idps in IraqSocial InquiryNo ratings yet

- Teaching Acceptance Strategies Through Visualization PDFDocument2 pagesTeaching Acceptance Strategies Through Visualization PDFVaibhav NahataNo ratings yet

- Offensive Deffensive - Stress and DTDocument5 pagesOffensive Deffensive - Stress and DTCristina EneNo ratings yet

- Edwards - Using Schemas and Schema Modes As A Basis For (POR EMPEZAR EL PROCESO de TRADUCCION)Document14 pagesEdwards - Using Schemas and Schema Modes As A Basis For (POR EMPEZAR EL PROCESO de TRADUCCION)MateoNo ratings yet

- Topic: Critical Incident Technique: Presenter: Asma ZiaDocument25 pagesTopic: Critical Incident Technique: Presenter: Asma Ziazia shaikhNo ratings yet

- Introduction To The Special Section On Attachment Theory and PsychotherapyDocument5 pagesIntroduction To The Special Section On Attachment Theory and PsychotherapyMichaeilaNo ratings yet

- Zanarini Rating Scale For Borderline Zanarini2003Document10 pagesZanarini Rating Scale For Borderline Zanarini2003Cesar CantaruttiNo ratings yet

- Training Design - PRIMALS 4-6 (Math)Document3 pagesTraining Design - PRIMALS 4-6 (Math)oliver100% (2)

- Division of Bohol: Republic of The Philippines Department of Education Region VII, Central VisayasDocument4 pagesDivision of Bohol: Republic of The Philippines Department of Education Region VII, Central VisayasLeoben Rey CagandeNo ratings yet

- MIDTERM-Features of Human Language by HockettDocument4 pagesMIDTERM-Features of Human Language by HockettBaucas, Rolanda D.100% (1)

- YP CORE User ManualDocument36 pagesYP CORE User Manualloubwoy100% (4)

- Attachment Questionnaire For ChildrenDocument1 pageAttachment Questionnaire For ChildrenSehar YasmeenNo ratings yet

- FM Evidence of Psychosocial Disability PDFDocument9 pagesFM Evidence of Psychosocial Disability PDFAndra DinuNo ratings yet

- ISST May 2015 Schema Therapy BulletinDocument18 pagesISST May 2015 Schema Therapy Bulletinxx xxNo ratings yet

- Chapter 20 - Culturally Adaptive InterviewingDocument94 pagesChapter 20 - Culturally Adaptive InterviewingNaomi LiangNo ratings yet

- Cognitive Behavior Theraphy PDFDocument20 pagesCognitive Behavior Theraphy PDFAhkam BloonNo ratings yet

- Anger Assessment in Clinical and Nonclinical Populations Further Validation of The State-Trait Anger Expression Inventory-2Document17 pagesAnger Assessment in Clinical and Nonclinical Populations Further Validation of The State-Trait Anger Expression Inventory-2Asiska Danim INo ratings yet

- Emotional Regulation Training For Intensive and Critical Care NursesDocument9 pagesEmotional Regulation Training For Intensive and Critical Care NursesvipereejayNo ratings yet

- BAI UrduDocument2 pagesBAI Urdusarwar BBNo ratings yet

- Youngmee Kim - Gender in Psycho-Oncology (2018, Oxford University Press, USA)Document263 pagesYoungmee Kim - Gender in Psycho-Oncology (2018, Oxford University Press, USA)Dian Oktaria SafitriNo ratings yet

- School Avoidance 101 - Assessment Scale & Parent ResourcesDocument13 pagesSchool Avoidance 101 - Assessment Scale & Parent Resourcesamrut muzumdarNo ratings yet

- Trans-Affirming Therapist List - 8Document8 pagesTrans-Affirming Therapist List - 8api-250491080No ratings yet

- Coventry Model Development PaperDocument15 pagesCoventry Model Development PaperAliens-and-antsNo ratings yet

- Coventry Model ASD Diagnosis ChecklistDocument8 pagesCoventry Model ASD Diagnosis ChecklistAliens-and-antsNo ratings yet

- Learning Disabilities: Debates On Definitions, Causes, Subtypes, and ResponsesDocument14 pagesLearning Disabilities: Debates On Definitions, Causes, Subtypes, and ResponsesAllison NataliaNo ratings yet

- Group1 - Module 1-Concepts of Physical EducationDocument6 pagesGroup1 - Module 1-Concepts of Physical EducationJawhara AmirolNo ratings yet

- Information Processing Psychology Write UpDocument4 pagesInformation Processing Psychology Write UpJess VillacortaNo ratings yet

- 2014 Ep, Ethical Dilemma, Conflict of Interest and SolutionDocument42 pages2014 Ep, Ethical Dilemma, Conflict of Interest and SolutionDanNisNo ratings yet

- George Washington Lesson PlanDocument4 pagesGeorge Washington Lesson Planapi-306790814No ratings yet

- Brief Symptom Inventory: Personality Studies - Study: ValidityDocument7 pagesBrief Symptom Inventory: Personality Studies - Study: ValidityKeen ZeahNo ratings yet

- Theories of Crime and DelinquencyDocument13 pagesTheories of Crime and DelinquencyPaul Macharia100% (1)

- Principles: of Marketing Global EditionDocument47 pagesPrinciples: of Marketing Global EditionNgoc PhamNo ratings yet

- Chapter 8Document2 pagesChapter 8Mark Anthony Mores FalogmeNo ratings yet

- Resume - Sheetal Khandelwal 2yr Exp TGT - Maths and ScienceDocument4 pagesResume - Sheetal Khandelwal 2yr Exp TGT - Maths and Sciencekamal khandelwalNo ratings yet

- Retorika Deliberatif Selebgram Dalam Memotivasi Audiens Melalui Media Sosial (Konten  Œlevel Upâ Di Akun Instagram Benakribo)Document8 pagesRetorika Deliberatif Selebgram Dalam Memotivasi Audiens Melalui Media Sosial (Konten  Œlevel Upâ Di Akun Instagram Benakribo)Rebekah KinantiNo ratings yet

- Kindergarten Quarter 4 Standards For Lesson PlansDocument2 pagesKindergarten Quarter 4 Standards For Lesson PlansLydiaDietschNo ratings yet

- Novice Teacher Orientation PDFDocument48 pagesNovice Teacher Orientation PDFEligius NyikaNo ratings yet

- Mary Kiriakidis - Final Position Paper FinalDocument13 pagesMary Kiriakidis - Final Position Paper Finalapi-682308329No ratings yet

- Chapter 1.1 Intro PsyDocument27 pagesChapter 1.1 Intro PsyFatimah EarhartNo ratings yet

- Maratha Roger's TheoryDocument19 pagesMaratha Roger's TheorySimon JosanNo ratings yet

- Assure ModelDocument33 pagesAssure ModelKarlyn Ramos100% (1)

- True Instinct Pheromone ReviewDocument5 pagesTrue Instinct Pheromone ReviewpheromonesforhimandherNo ratings yet

- WLP#6 Mathematics10 Sy2019-2020 PampangaDocument4 pagesWLP#6 Mathematics10 Sy2019-2020 PampangaAnonymous FNahcfNo ratings yet

- Objectives-Stategies-Impact of Counselling by CarlosibarraDocument4 pagesObjectives-Stategies-Impact of Counselling by CarlosibarraCarlos Ibarra R.No ratings yet

- Empathy and Sympathy in EthicsDocument13 pagesEmpathy and Sympathy in EthicsAlessandro BerciouxNo ratings yet