Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Washreg Approach

Uploaded by

Andrea Carolina FochesatoOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Washreg Approach

Uploaded by

Andrea Carolina FochesatoCopyright:

Available Formats

DISCLAIMER

This publication may be reproduced in whole or in part and in any form for educational or non-profit

purposes without special permission from the copyright holder provided proper acknowledgement of

the source is made.

The authors would appreciate receiving a copy of any publication that uses this publication as a

source. No use of this publication may be made for resale or for any other commercial purpose

without prior permission in writing from SIWI and from UNICEF.

The designation of geographical entities in this report, and the presentation of the material herein, do

not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the publisher or the participating

organizations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or of its authorities, or

concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries.

Copyright © 2021, Stockholm International Water Institute, SIWI

Copyright © 2021, United Nations Children’s Fund, UNICEF

Copyright © 2021, World Health Organisation, WHO

Copyright © 2021, Inter American Development Bank IADB

FOR MORE INFORMATION

For further information, suggestions, and feedback, please contact the Stockholm International Water

Institute (SIWI) www.siwi.org and UNICEF New York headquarters www.unicef.org.

AUTHORS

This report was co-authored by a team from the SIWI Water and Sanitation Department composed of

Ivan Draganic (Lead consultant), Pilar Avello and Alejandro Jiménez. The authors contributed equally

to this work.

CONTRIBUTORS

Substantial contributions were provided by Jorge Alvarez Sala (WASH Specialist ,UNICEF NY), Bisi

Agberemi (WASH Specialist ,UNICEF NY), Silvia Gaya (Senior Water and Environment Advisor, UNICEF

NY), Robin Ward (Program Manager, SIWI), Batsirai Majuru, (Technical Officer for Water, Sanitation,

Hygiene and Health, WHO), Jennifer De France (Team lead for drinking-water quality, WHO), Kate

Medlicott (Team lead for sanitation, WHO), Corinne Cathala (IADB), Virginia Mariezcurrena (Program

Manager, SIWI), and Lotten Hubendick (Program officer, SIWI).

HOW TO CITE

SIWI/UNICEF/WHO/IADB (2021) “The WASHREG Approach: An Overview” Stockholm and New York.

Available from www.siwi.org

Version for Print, 2021

CONTENTS

FOREWORD________________________________________________________________ II

GLOSSARY________________________________________________________________ III

1. THE NEED TO REGULATE WATER AND SANITATION SERVICE PROVISION______ 1

2. WASH REGULATORY GOVERNANCE_______________________________________ 3

2.1 Regulation theory_____________________________________________________________ 3

2.2 Regulatory models____________________________________________________________ 4

2.3 Regulatory autonomy__________________________________________________________ 4

2.4 Regulatory principles__________________________________________________________ 5

2.5 Regulatory accountability______________________________________________________ 5

3. GEOGRAPHICAL REGULATORY SCOPE_____________________________________ 8

3.1 Regulation of water and sanitation services in a decentralized context________________ 8

3.2 Urban water and sanitation services regulation____________________________________ 8

3.3 Rural water and sanitation services regulation_____________________________________ 9

4. REGULATORY AREAS____________________________________________________ 10

4.1 Tariff setting or price regulation_________________________________________________ 11

4.2 Service quality regulation______________________________________________________ 11

4.3 Competition regulation________________________________________________________ 12

4.4 Consumer protection regulation________________________________________________ 12

4.5 Environmental regulation______________________________________________________ 13

4.6 Public health regulation_______________________________________________________ 13

5. THE REGULATORY CYCLE________________________________________________ 14

6. WORKING WITH REGULATION: THE WASHREG APPROACH´S METHODOLOGY___ 15

BIBLIOGRAPHY____________________________________________________________ 16

THE WASHREG APPROACH: AN OVERVIEW | i

FOREWORD

The Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) a phased approach to regulatory reform. The

6 Global Acceleration Framework calls for a conceptual framework for regulatory reform is

dramatic acceleration to meet off-track SDG 6 further explained, and an accompanying full

targets. The SDG targets for WASH go further methodology is provided in a separate document:

than just the provision of facilities. They target “The WASHREG Approach: Methodology”,

safely managed water and sanitation services, which provides a practical step by step guide to

which requires sustainable local service models help countries identify and plan for implementing

operating under a robust regulatory framework. the “best-fit” solution to regulatory reform.

Estimates indicate that, despite progress made This product is part of the set of guidance

in the preceding decades, in 2020, around one documents produced under the “Accountability

in four people lacked safely managed drinking for Sustainability”1 partnership, between

water in their homes and nearly half the world’s UNICEF, SIWI and the UNDP-SIWI Water

population lacked safely managed sanitation Governance Facility – which aims at increasing

(UNICEF & WHO, 2021). Lack of safe water, sustainability of WASH interventions through

and poor sanitation and wastewater practices, the improvement of governance in the WASH

have serious impacts on people’s health service delivery framework. The World Health

and the environment. The recognition of the Organization (WHO) and the Inter American

human rights to water and sanitation, and the Development Bank (IADB) have provided

international commitment towards sustainable substantial inputs to the development of the

water and sanitation services for all, expressed WASHREG Approach documents. We believe

through the SDGs, demands a stronger focus that by strengthening regulation, countries can

on both expanding the coverage of facilities and improve the performance and sustainability of

services, and on ensuring the quality of services water and sanitation service delivery, achieving

delivered. Regulation of water and sanitation the SDG targets on universal access to services,

services in the economic, social, public health and realizing the human rights to water and

and environmental dimensions, is an essential sanitation for all.

governance function, which ensures better

service outcomes, in terms of affordability,

consumer protection, quality of service, public

health, and environmental protection.

This “WASH Regulation (WASHREG)

Approach: An Overview” is intended to help

WASH professionals and other stakeholders

understand the elements of WASH regulation

within a broader enabling environment for

effective and sustainable WASH service delivery.

The document aims to provide clarity on the

main areas of WASH regulation, the main

tasks of water and sanitation regulatory actors

and introduces a conceptual framework for

1 https://www.siwi.org/what-we-do/accountability-for-sustainability/#partnership

ii | THE WASHREG APPROACH: AN OVERVIEW

GLOSSARY

ENABLING ENVIRONMENT: the set of REGULATORY MODEL (OR REGIME): generally

interrelated sector functions that impact the understood as a set of agreements on the

capacity of governments and public and private division of the respective responsibilities of

partners to engage in the WASH service delivery actors involved in the sector regulation.

development processes in a sustained and

effective manner. In the context of UNICEF’s REGULATORY ACTORS: used in a broad sense,

work, an enabling environment for WASH is includes government institutions that exercise

one that creates the conditions for a country to regulatory functions (i.e. a department within a

have sustainable, at-scale WASH services that ministry) and separate bodies created by the State

will facilitate achievement of Universal Access to carry out regulatory functions (Heller, 2017).

for All to WASH with Progressive Reduction in

Inequality (UNICEF, 2016). REGULATOR (OR REGULATORY BODY OR

REGULATORY AUTHORITY): a public authority

WATER GOVERNANCE: Water governance responsible for applying and enforcing standards,

defines who gets water, when and how, and who criteria, rules or requirements – which have

has the right to water and its related services been politically, legally or contractually adopted

and benefits (Allan, 2001). Hence, governance – exercising autonomous authority over the

is about the processes and institutions involved Services, in a supervisory capacity (International

in decision-making about water. From this Water Association, 2015)

procedural perspective, it has been defined

as “a combination of functions, performed REGULATORY AREAS: the different areas which

with certain attributes, to achieve one or more can be subject to regulation in the water and

desired outcomes, all shaped by the values and sanitation sector: tariff setting or price regulation,

aspirations of individuals and organisations” service quality, competition, consumer

(Jiménez et al., 2020). protection, environment, and public health.

REGULATION (OR THE REGULATION FUNCTION): REGULATORY POWERS: the instruments

the legal mechanisms, enforcement processes used by regulatory actors to ensure individuals

and other rules to ensure that stakeholders fulfil and operators comply with regulations. The

their mandates, and that standards, obligations powers are: rule definition and approval granting;

and performance are maintained, as well as to monitoring and informing; and enforcement.

ensure that the interests of each stakeholder are

respected (Jiménez et al., 2020).

REGULATION THEORY: a set of propositions

or hypotheses about why regulation emerges,

which actors contribute to that emergence and

typical patterns of interaction between regulatory

actors (Morgan & Yeung, 2007).

REGULATORY AUTONOMY: refers to the

capacity of regulatory actors to be protected

against other powerful groups or entities’

interferences.

THE WASHREG APPROACH: AN OVERVIEW | III

1. THE NEED TO REGULATE WATER AND

SANITATION SERVICE PROVISION

The Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 6 course corrections for the compliance of the

Global Acceleration Framework aims to deliver services provided with the normative content

fast results at an increased scale as part of the of the human rights to water and sanitation,

Decade of Action to deliver the SDGs by 2030. which call for services to be available, affordable,

By committing to the Framework, the United accessible, acceptable, of quality and safe

Nations (UN) system, and its multi-stakeholder to all; and to be delivered in a transparent,

partners, driven by country demand, and accountable, participatory, non-discriminatory

coordinating through UN-Water, will unify the and sustainable way (Heller, 2017).

international community’s support to countries

to rapidly accelerate towards national targets for Second, the water and sanitation sector is highly

SDG 6. The framework identifies five accelerators dependent on large infrastructural works, which

(financing; data and information; capacity is a reason why water and sanitation service

development; innovation; and governance). provision becomes a natural monopoly. Without

Regulation contributes to all of them. Well public oversight, water and sanitation service

balanced regulation is an essential component operators could possibly neglect key factors such

of governance, as it helps to clarify the roles and as the quality of services, certain geographical

responsibilities of different stakeholders; it allows areas, population groups or simply charge

for more predictable financing of the sector, by unreasonable tariffs. As such, public oversight

highlighting the performance, and strengths is articulated through regulation of economic,

and weaknesses of the service providers; it public health and environmental elements of

contributes to data collection and availability services, which is primarily necessary to protect

of information about the sector, including for consumers´ interests and their rights. On the

the public; it can promote innovation through other hand, since the water and sanitation

new standards, and performance criteria; and service might be provided at a loss to ensure

it can support capacity development of service full coverage and uniform pricing, the operator

providers and consumers, through technical needs to be compensated. The governments

support, and peer to peer exchange among and relevant authorities can manage such

operators. compensation through various modalities. In

some cases, operators are reimbursed through

In most jurisdictions, regulation of water supply is cross-subsidization i.e., the areas profitably

significantly more established and well-defined than serviced compensate those served under an

for sanitation, and especially for on-site sanitation imposition. In many urban cases, utilities receive

facilities and faecal sludge management. Regulation subsidies from the national or municipal budget

of sanitation is in a period of rapid evolution and as well. It is in this context that regulation is set

effective approaches are beginning to emerge. to make service operators more accountable, to

As such, guidance within this concept note and establish an independent price-setting process

accompanying methodology is likely to evolve as and to bring regulatory expertise into the public

new experiences emerge. sector. There are, however, some exceptions,

where water and sanitation services are not

Regulation aims to address different elements considered to be a natural monopoly. In areas

of water and sanitation service delivery. First, where water is provided by trucks, kiosks,

water and sanitation are not only services, but standpipes or through any other kind of on-

human rights that need to be guaranteed. In this selling arrangement, users might benefit from

regard, regulation is key to monitor and make competition among several operators. This is

1 | THE WASHREG APPROACH: AN OVERVIEW

also frequently the case in sanitation and faecal Lastly, the provision of water and sanitation

sludge management services provision, e.g., services may have externalities that can be

on-site sanitation emptying services. In these both negative and positive. Consumption of

circumstances the role of a regulatory body is contaminated water, for instance, that sparks an

to first ensure free market entry to all interested epidemic disease such as cholera can quickly

parties, and second, to play an anti-monopoly spread beyond the geographical zone from which

role in the case of an abuse of a dominant the services originate. Over abstraction at a

position by a single operator, or several operators. water point or intake could affect a downstream

waterbody, its related ecosystems, and limit

Third, unequal access to information between downstream consumers’ ability to access services.

operators and consumers in the absence of On the positive side, an increase of wastewater

regulation could result in severe consequences and faecal sludge treatment in a specific

for the consumers. Information about poor geographical area could improve the surrounding

water quality or service interruption are among environment and the lives of citizens. Regulating

those where timely notification could prevent the public health, social and environmental costs of

potential public health problems or other related service operator activities are, therefore, important

and unnecessary damage to consumers. To elements to ensure an optimal level of service

bridge this gap, a wide range of reporting and provision, and adequate protection, when it comes

monitoring requirements and mechanisms exist to the impact both within and beyond the area in

that specify the different types and quality of which the services originate.

information to be provided.

THE WASHREG APPROACH: AN OVERVIEW | 2

2. WASH REGULATORY GOVERNANCE

Regulation is one of the core water and sanitation if contracts are well established between the

governance functions and is described as the parties and impartial courts ensure efficiency

“legal mechanisms, enforcement processes through appropriate wrongdoing rules and

and other rules to ensure that stakeholders fulfil enforcement of contracts. In this sense,

their mandates, and that standards, obligations potential wrongdoers are disincentivized by the

and performance are maintained, as well as to consequences of breaching contracts if well-

ensure that the interests of each stakeholder are functioning courts enforce them, and in this

respected” (Jiménez et al., 2020). scenario, scholars of the contracting theory

argue that only limited regulation can be justified

The UN system views human rights norms and (Posner, 1974).

standards as its primary frame of reference

for everything it does. Following the Special The capture theory of Stigler (1971) critiques

Rapporteur’s (Heller, 2017) interpretation, the the public interest theory’s understanding that

ultimate goal of WASH regulation should be to the government is a benign being, because the

give practical meaning to the normative content regulator can be controlled by different group

and principles of the human rights to water interests, hence a fully independent role of a

and sanitation. However, there is no single regulator is almost impossible and instead it is

formula on how to best achieve that goal and more an arbiter between conflicting interests.

the mechanisms and processes designed and Scholars of the capture theory have been very

implemented are different from one country to prolific in developing mechanisms to control

another. The study of those differences and the regulatory activity, ensuring performance of

implications for regulatory outcomes constitutes the utilities, creating coordination mechanisms

what is known as regulatory governance. about regulatory activities, and establishing a

This chapter unpacks the concept of WASH clear, transparent, accountable, legitimate, and

regulatory governance by presenting the main credible regulatory process.

concepts about regulation theory, models,

autonomy, principles, and accountability. The theories of regulation are not mutually

exclusive and policy makers’ choices are the

2.1 Regulation theory result of a combination of influences from the

various theories that impact on decisions about

While a full discussion about regulation theory is the regulatory model, regulatory autonomy,

beyond the scope of this note, it is important to and the mechanisms to ensure regulatory

understand the main schools of thought that have accountability. In any case, in the last decades,

come with different ways to understand and think the trend in WASH regulatory reform has

about regulation in our society. Public interest witnessed the creation of quasi-autonomous

theory (Pigou, 1920) , also known as the welfare regulatory agencies and an increased

state, presents that markets often fail because application of rules to protect “public services”

of problems of monopolies or other factors, (Cabrera & Cabrera, 2016; Melo Baptista, 2014;

and assumes that governments are capable of Lodge, 2001; Mumssen et al., 2018; OECD,

correcting those failures through regulation. Public 2014, 2015; Rouse, 2013).

interest theory has been used to justify much of

the growth of public ownership and regulation over However, there is a need to acknowledge that

the twentieth century (Shleifer, 2005). current regulatory theory is better suited to

service provision through large infrastructure and

The contracting theory, associated with Coase professional service providers, mainly in urban

(1960), assumes that regulation can happen areas. Regulatory theory does not always apply,

3 | THE WASHREG APPROACH: AN OVERVIEW

particularly for water supplies in rural areas (e.g., respective responsibilities of actors involved in

community water supplies), and for sanitation, a certain sector. There is no magic formula in

when the household is not connected to a relation to the models, and the solutions that

sewerage network. In this case, service provision may have worked for some countries may not

can have multiple actors along the sanitation value work for others (Heller, 2017). In the water and

chain, many of them acting informally. In these sanitation sector, the most common models

cases, regulation needs to balance enforcement are regulation by government, regulation by an

measures with support for professionalization and agency, regulation by contract, regulation by

technical support to operators. outsourcing some activities to third parties and

self-regulation (Mumssen et al., 2018; OECD,

2.2 Regulatory models 2015). These five models are summarized below:

Regulatory models are generally understood

as a set of agreements on the division of the

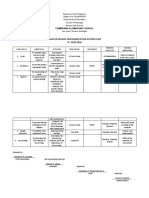

The public sector owns Concerns the Also known as the Use of external Service providers

the assets and has the establishment of an French model. This is contractors to perform regulate their own

responsibility of the agency responsible for one of the predominant certain duties such as activities, set tariffs and

management. The conducting regulation in models, especially in tariff review, quality standards and

Netherlands and a more or less those countries in benchmarking or monitor their own

Germany have this autonomous manner which the municipalities dispute resolution performance

model and adapts the rules to have the responsibility

changing circumstances for service provision

REGULATION BY

REGULATION BY REGULATION BY REGULATION SELF-

SOURCING TO

GOVERNMENT AN AGENCY BY CONTRACT REGULATION

3RD PARTIES

Figure 1: Regulatory models

The most important lesson to bear in mind for policymakers, service providers and users; and

regulatory designers is that there is no single they are the best placed to assess whether water

international best practice for regulatory models. and sanitation rights are being progressively

In fact, the models are not mutually exclusively met, or are being overlooked. In this regard, it

and tend to adopt different aspects of each one of is recognized that although no universal model

them. For example, when addressing sanitation, exists, those carrying out regulatory activity

there are different regulatory mechanism options should enjoy some level of immunity, or regulatory

that can be applied across the sanitation service autonomy, against pressures from illegitimate

chain (containment, conveyance, treatment, and interests, so that the main objectives of regulation

end use/disposal), as highlighted by WHO in the are aligned with the human rights to drinking

Guidelines on Sanitation and Health (World Health water and sanitation (Heller, 2017). Regulatory

Organization (WHO), 2018). Although, it is worth autonomy refers to the capacity of regulatory

acknowledging, that in the past two decades, actors to take and implement decisions without

countries have tended to develop a dedicated influence from other powerful groups or entities.

regulatory body in the water and sanitation sector It is important to acknowledge though that in

(OECD, 2015). The most effective regulatory some situations, regulatory autonomy is far

model depends on a multitude of factors including from present. A starting point in those cases to

the country’s legal and political system, as well as improve autonomy is to identify authorities with

its governance structure (Mumssen et al., 2018). some responsibility for oversight and establish

a dialogue to understand the existing degree of

2.3 Regulatory autonomy autonomy, and to identify feasible avenues for

making progress. When discussing regulatory

The human rights framework understands that autonomy, it is important to understand different

regulatory actors are at the interface between autonomy dimensions: institutional, financial,

THE WASHREG APPROACH: AN OVERVIEW | 4

managerial, political, and decentralized autonomy. towards the full realization of the rights.

Institutional autonomy: refers to the skills The principle and obligation of progressive

and capacity a regulatory actor needs to secure realization refers to the obligation of regulatory

to initiate or implement regulatory practice. actors to put in practice regulatory measures

Institutional autonomy also includes the ability to ensure that the State utilizes the maximum

of the regulatory actor to ensure capacity of their available resources to move beyond the

building activities for operators and consumer minimum levels of water and sanitation service

associations around regulation. provision. However, regulatory frameworks should

be appropriate for the existing service landscape

Financial autonomy: refers to the ability of the and policy goals need to be achievable. As each

regulatory actor to secure sufficient resources goal is achieved, and as additional resources

to initiate or implement regulatory practice. and capacity are gained, the regulations can be

Regulatory actors should ideally rely financially increased in complexity and/or scope over time.

on the licenses and fines it issues and imposes The principle and obligation to ensure equality

on operators as its own and unique revenue, and non-discrimination is ensuring the same

distinct and clearly separated from the state or treatment to all consumers without any distinction

governmental budget. based on race, political affiliation, origin, religion,

gender, age, or other condition. To ensure

Managerial autonomy: refers to the existence non-discrimination, regulatory actors must,

of an established regulatory mandate with a clear for example, when regulating prices, consider

matrix of roles and responsibilities among the those who cannot pay for services, or implement

principal actors within the sector. It also includes mechanisms for their protection. Regulatory

the ability of the regulatory actor to secure actors also have the obligation to identify and

appropriate human resources and respond to the monitor possible retrogressions in the realization

needs of the sector. of the rights, and the obligation to find and

remediate the root causes of these violations.

Political autonomy: refers to the ability of

the regulatory actor to be protected against In addition to these three main obligations,

political interferences. As the regulatory mandate there are additional human rights principles that

is granted by a state it is a state itself that should guide not only regulatory actors and

often tends to control the decision making WASH regulations, but the entirety of WASH

around regulatory policies, for its own interest. service provision: active, free and meaningful

Regulatory actor staff should ideally remain participation; access to information; and

detached from political engagement. sustainability.

Decentralized autonomy: refers to the capacity 2.5 Regulatory accountability

of the regulatory actor to delegate and supervise

certain regulatory activities to decentralized The principle of accountability, defined as “the

government levels. democratic principle whereby elected officials

and those in charge of providing access to

2.4 Regulatory principles water supply and sanitation services account

for their actions and answer to those they

From a human rights perspective, “regulatory serve” (UNDP-SIWI Water Governance Facility

actors must ensure that their policies, & UNICEF, 2015), also applies to the regulatory

procedures and activities are compliant with the actors and to the degree to which they are

State’s international human rights obligations held accountable for their choices and actions.

in relation to the rights to water and sanitation” The study of accountability poses an essential

(Heller, 2017). In this regard, regulatory actors question to both regulatory scholars and to

are bound by certain principles and obligations: theories of democratic participation (Baldwin

progressive realization, equality and non- et al., 2012; Gerber & Teske, 2000; Graham,

discrimination and the obligation to take steps 1995; Majone, 1997).

5 | THE WASHREG APPROACH: AN OVERVIEW

WASH regulation is highly complex, requiring and transparent a regulator should be (OECD,

significant technical expertise, like other 2014b). Regulatory actors are generally

regulated sectors; because of this complexity accountable to the three same actors for which

there is a consequent delegation of substantial they act as referee (Figure 2): the government or

policymaking authority to the regulatory staff. parliament (policy-maker), the service providers

Accountability is considered as the other side of (or regulated entities) and the users, or more

the coin to autonomy, and the more autonomous generally, the public.

a regulatory actor is, the more accountable

POLICY

MAKER

AC VI

SE

CO CE

R

UN PR

IG S

S

L R ED

TA OV

HT

GA NE

BIL IS

CO RVIC

EN ON

SE

G

ITY ION

LE ICE,

NT E P

DIN

SP TY

RA RO

ON

VO

ILI

BL AB

CT

PU UNT

FO ISIO

IC

R

V

CO

AC

REGULATOR

COMMUNITIES SERVICE

PAYMENT (TARIFF)

/ USERS AND COMPLAINTS PROVIDERS

SERVICE PROVISION

(ACCORDING TO CONTRACT)

Figure 2: Accountability service delivery triangle (UNDP-SIWI Water Governance Facility & UNICEF, 2015)

The different elements of accountability are Assembly, 2018; Jiménez et al., 2018; UNICEF &

often explained through its three-dimensional UNDP/SIWI, 2016).

approach: responsibility, refers to the existence

of clear roles and responsibilities of the actors The fundamentals of regulatory accountability

for the variety of processes and the coordination combine these two levels of analysis, with the actors

mechanisms between them; answerability refers to whom the regulator should be accountable to

to the mechanisms whereby the actors provide on one side, and on the other side, the different

explanations of, and justification for, their actions, elements of the accountability dimensions (Table

inaction and decisions; and enforceability, refers 1). For these accountability lines to be operational,

to the existence of mechanisms to oversee and regulatory data and its granularity is of particular

ensure actors’ compliance with established importance, to enable accountability as well as to

standards, impose sanctions and ensure that evaluate if the regulatory mechanisms are benefiting

corrective and remedial action is taken (General sub-groups as intended.

THE WASHREG APPROACH: AN OVERVIEW | 6

Table 1: Regulatory accountability. Sources: UNDP-SIWI Water Governance Facility & UNICEF, 2015

and OECD, 2014b

7 | THE WASHREG APPROACH: AN OVERVIEW

3. GEOGRAPHICAL REGULATORY SCOPE

All water and sanitation service operators should As much as decentralization can promote

fall under the scope of a regulatory authority, better and more efficient services through

regardless of the management model adopted enhanced accountability, it is empirically evident

in each context. All service providers should that decentralized regulation is not easy to

be subject to regulation. This would ensure the implement. How is it possible to implement

same level of protection to any user, regardless decentralized water and sanitation regulation in

of the operator that provides the service to countries with limited resources and capacities?

them. However, this might not be feasible To what extent is it possible to rely on local

in the short term in many circumstances. In authorities for consumer protection or when

those cases, progressive improvement towards challenged to develop sustainable and affordable

reaching this goal will be needed, by using a tariff systems in impoverished areas? Most

risk-based approach – i.e., prioritising regulatory of the answers to these questions lie within

aspects and service providers that pose the strengthened capacities, legislative reforms, and

highest risk to population if not dealt with, and an appropriate balance between central and local

acting on them first. power, and between regulation by centralized

and decentralized bodies. This includes an

Regulatory intervention should be geographically appropriate decentralization legislative reform

bordered, ideally nationally, or regionally in to strengthen central to local level governance

large countries. This allows for a broad view relations; capacities in provision of water and

of the sector, whereby a regulatory actor can sanitation services, and improved accountability,

better harmonize the rules, procedures, and oversight, and participation of locals in a bottom-

interpretations in an extended territory, with the top approach. In some countries, such as in

possibility of benchmarking a more significant Colombia, Mozambique, Honduras, or Zambia,

number of operators. In general, the bigger the even though water services are decentralized, a

territory it regulates, the larger is the rationalization national regulatory body has been established.

of regulatory resources and provision of lower

service unit costs per user is ensured. At the same 3.2 Urban water and sanitation services

time, the geographical regulatory scope needs regulation

to be matched with the resources and capacity

needed to successfully undertake the regulation. Regulation has been historically focused on

urban centres, typically determined by many

3.1 Regulation of water and sanitation users serviced by a single service provider (a

services in a decentralized context “utility”), with a networked infrastructure providing

piped water and a sewerage network for

Theory suggests that a local government’s sanitation. However, modern cities face multiple

proximity to citizens gives the latter more challenges that are not always well addressed

influence over local officials, promotes productive by this typical regulation. Rapid increase in

competition among local governments, urban populations, and lack of proper planning,

and alleviates corruption through improved have led to almost a billion people worldwide

transparency and accountability. At the same living in informal settlements. These peri-urban

time, decentralisation can generate negative areas often fall into a responsibility gap between

effects, if local political dynamics undermine rural and urban authorities, leaving them in a

accountability, or local governments have grey zone of unclear legalities, regulations, and

inadequate capacity, or face weak incentives to administration. Multiple informal actors step in to

act as the theory predicts (Smoke, 2015). deliver services (e.g., water vendors), which are

typically not covered by regulation.

THE WASHREG APPROACH: AN OVERVIEW | 8

The challenge for sanitation is even much larger. or service provision may fall directly under

In developing countries, the proportion of citizens municipal services. At the same time, several

connected to sewerage systems is very low, and it rural service operators may perform informally in

is even lower when considering proper treatment a legal vacuum. However, more recently these

and disposal of wastewater and faecal sludge. Over informal service operators tend to formalize

a billion people in urban and peri-urban areas of their status through signed contracts with

Africa, Asia, and Latin America are served by onsite local community-based organizations or local

sanitation technologies. And, around 2.7 billion governments (regulation by contract).

need faecal sludge management (FSM) services for

emptying, transporting, treating and safely disposing As much as these contracts regulate their

the waste generated (Strande et al., 2014). FSM activities, support is still required from regional

is very different from wastewater management. or national institutions when conducting certain

Multiple actors, who often operate informally, are regulatory activities, mainly because regulatory

involved in FSM, and these actors might perform actor and service operator capacity is often low

different functions within the sanitation service chain. in rural contexts. For this reason, it is common

to find regulatory instruments that mostly rely on

Hence, regulation needs to cover all actors the dissemination of information and consumer

and each step of the sanitation service chain, feedback, to increase accountability and

including the storage, collection, transport, minimize intensive and costly monitoring, and

treatment and end use or disposal of faecal application of penalties. For example, the water

sludge. The actors providing FSM services will watch groups created by the Zambian regulator

require a substantial effort from the regulator in (NWASCO) are voluntary consumer groups

terms of the provision of licenses for qualified responsible for monitoring the performance of

operators, coordination across stages of the the local authorities or utilities and for ensuring

service chain, and monitoring and follow up of that consumer water rights are protected, and

their performance. This also includes the control that information is readily available to consumers.

of discharges to the environment.

An important segment of service delivery

3.3 Rural water and sanitation services activities in rural areas are those that are

regulation performed on a voluntary basis in the form

of village water committees. In such cases,

In the context of rural areas, it is difficult to regulation based on penalties risks being

identify and introduce regulatory mechanisms ineffective, as it will only impose a higher

due to the number of rather small service burden on the already weak structure and

providers (or even self-supply arrangements), might lead towards discontinuation of service

geographical dispersion, low level of provision activities. Hence, a more “supportive”

formalization and limited access to information regulation, which includes capacity development

at central level. These service providers often and support for compliance, is often more

have limited resources to respond to regulatory appropriate in these contexts.

requirements and penalties. Hence, it is

generally necessary to apply a mix of approaches

to regulate water and sanitation services,

relying on a mix of contracts, national-level

regulatory bodies, and in some cases, regulatory

attributions at the local level (Trémolet, 2013).

Regulation in rural areas is sometimes very

complex, as the service provision can be

undertaken by many operators, (e.g., several

thousands in many countries), with legal statuses

ranging from private to community associations,

9 | THE WASHREG APPROACH: AN OVERVIEW

4. REGULATORY AREAS

In the same way that there is no universal also considered the areas that constitute economic

regulatory regime implemented by all countries, regulation, and in many countries, there exists a

regulatory actors conduct a combination of dedicated regulatory agency. In contrast are public

very different activities (OECD, 2015) that can health and environmental regulation that often

be organized around six main regulatory areas: fall within the mandate of ministries of health or

tariff setting/price regulation, service quality, environment, or a specific dedicated public health

competition, consumer protection, environment or environmental protection agency.

and public health (Figure 3). The first four area are

Figure 3: Regulatory areas.

It should be noted that there may be overlap regulatory aspects such as water quantity, supply

between the different regulatory areas, notably reliability and continuity, pressure, and wastewater

between Public Health and Environment and Public treatment and sludge standards are relevant for

Health and Service Quality. For example, effective public health regulation and should be coherent

catchment management for drinking water source between the two. And in turn these linked service

protection, and setting of effluent standards, quality and public health aspects also affect the

requires coherence between public health and cost of water delivered, and thus the tariffs to be

environmental regulation. Similarly, service quality set and charged. Hence the different regulatory

THE WASHREG APPROACH: AN OVERVIEW | 10

functions are interlinked, and coherence is needed Other common approaches are price cap

between the different mandates to avoid gaps regulation, revenue cap regulation or yardstick

and overlaps, as well as cooperation among the competition, which are approaches based

different institutions involved. on performance incentives which introduce

the component of productivity to motivate

Capacity building and resourcing for implementation operators to improve their efficiency and increase

of regulatory functions within the responsible innovation. Price cap regulation consists of

agencies is critical for regulation to work smoothly establishing an average limit or cap for the prices

(World Health Organization (WHO), 2018). of the water, wastewater and FSM services

during a given regulatory period, between three

4.1 Tariff setting or price regulation and ten years. The regulated operators retain

the profits coming from the reduction of costs

Price regulation can be defined as the that happens during the given period, along with

establishment and implementation of a set of those gained through improved productivity. At

specific rules for the definition of tariffs and the end of each regulatory period, the benefits

prices, inducing operators to achieve optimum of the cost reductions are partially transferred

results in terms of the prices adopted, the to consumers through the reduction of prices

quantities produced, and the standards of during the next regulatory period. In revenue cap

quality offered. It is considered one of the most regulation, operators are limited to a maximum

important regulatory areas, and whether services average value for their revenues. The revenue

are outlined through public or private ownership ceiling is established through a consumer price

and irrespective of the actual regulatory model, index and a factor that translates variations,

tariff setting is necessary and essential for the in terms of productivity. The gains achieved

sustainability of water and sanitation services. are transferred to consumers within the next

regulatory timeframe. Yardstick competition

Tariffs should be sufficient to cover the costs of is price regulation by comparison, between

providing the service. Various definitions may be a given operator and its peers through a

used, depending on how far the existing tariffs are benchmarking exercise, that is in turn translated

from full cost-recovery levels and how challenging into financial consequences. The key element

moving to cost-recovery levels may be in the short of this regulatory model consists of redirecting

term. In general, legislation would require that incentives to improve efficiency for a given

tariffs cover at least the operation and maintenance operator through information extracted from

costs, plus the costs of investments (that is, other operators. In consequence, this constitutes

depreciation and a fair return on capital), but this an artificial form of competition between the

might not always be implemented in practice. regulated operators. The yardstick approach also

serves against asymmetry in information among

One of the most common approaches to price- the operators and tends to set a fertile ground

regulation is the rate-of-return price, also called the for transparency and access to information.

American approach, that allows an operator to set However, a sufficient base of comparable service

a level of remuneration based on the investments providers is required for this approach to work

preapproved by the regulator. Within this approach, (Rouse, 2013).

a regulatory body defines the prices and facilitates

the definition of tariff systems that motivate the 4.2 Service quality regulation

accomplishment of non-economic objectives

(e.g., contexts involving the extensive creation Service quality regulation is defined as the

of infrastructure in less mature sectors), and, establishment and implementation of a set

especially, cross-subsidization between users, or of specific rules to achieve a certain level of

between the services supplied. However, if under- service in relation to certain characteristics

regulated, the operators do not have incentives such as technical requirements or customer

to reduce the costs and have a remuneration responsiveness. Service quality regulation

regardless of the operators’ actual performance. can be direct or indirect. In direct regulation,

11 | THE WASHREG APPROACH: AN OVERVIEW

a service quality parameter is included in the further investigate such abuses and to take

service contract, with the operators being concrete actions to resolve it. Depending on the

rewarded or penalized following their level of nature of the abuse, a possible range of actions

compliance at the end of a regulatory period. may include breaking of the oligopoly through

The indirect approach penalizes and rewards financial penalties, enforcement of asset sale to

operators occasionally and periodically during break a dominant position, or imposition of an

the regulatory period for shortcomings in their obligation to supply.

performance (e.g., a failure to address consumer

complaints), according to the minimum Competition is also important in the provision of

standards of quality that had been defined. sanitation and faecal sludge management (FSM)

Operators are not audited randomly under services. The sanitation service value chain

the direct approach, and enjoy more freedom might be fragmented, and different operators

to manage the quality of service (Rovizzi & can be working on on-site sanitation emptying,

Thompson, 1992). transportation, treatment and discharge, or

eventual re-use of by-products. To learn about

Both direct and indirect service quality regulation can the market dynamics, the competition regulatory

use the benchmarking approach, which consists activity must first seek to obtain all the available

of the application of comparative and quantitative data and information to assess the existence of

methods that are used to assess and measure anti-competitive abuses. On many occasions,

the performance of operators over the course the first step will be to provide licenses to

of time, for instance in monitoring sustainability the operators that might be operating in the

through sustainability checks or other monitoring informal sector. At the same time, it is important

mechanisms. The use of benchmarking indicators to oversee quality of service and public health

results in continuous pressure on the operators to regulations when trying to establish competition

improve the quality of service, whilst also increasing in the market- for example, by avoiding a

the sharing and transparency of information, and situation where services providers limit the

minimizing the asymmetry of information that equipment for sanitation workers to reduce

exists between regulators and operators. Another costs. Similarly, as for water, when an abuse is

approach in service quality regulation is the found, sanctions will be imposed, for example,

sunshine approach, which obliges operators to when a few operators in an area have created an

make available all relevant service information and oligopoly and agreed to charge an unreasonable

actions for public observation, participation, and/or tariff to consumers.

inspection, and it is through the exposure to media

and the public that this approach has proven to 4.4 Consumer protection regulation

have a competitive impact on the sector.

Consumer protection regulation is defined as

As mentioned earlier, there can be quite a blurred the establishment and implementation of a set

line between service quality and public health of specific rules applicable to the water and

regulation. For example, technical requirements sanitation service providers in order to achieve

and protection of sanitation workers’ standards, the protection of the users. Regulatory actors

are both integral to service quality and public are due to audit all the available mechanisms for

health protection. consumer protection, to assess to what extent

they are relevant, and to help consumers identify

4.3 Competition regulation and claim their own standards and requirements.

Competition regulation is defined as the In addition, regulatory actors collect consumer

establishment and implementation of a set of and operator views through different consultation

specific rules to prevent the abuse of a dominant processes, review the results, and potentially

position by one or several operators through amend regulatory policies. Typical forms of

oligopoly (e.g., water trucking). If abuse is consultations are informal consultation with

found, the regulatory actor is duly bound to selected groups, public meetings open to any

THE WASHREG APPROACH: AN OVERVIEW | 12

user, consultation with other sector regulators, offending operator to remediate and compensate

public notice of regulatory intentions, open for the environmental damage.

calls for commenting on policy documents, or

preparatory public commissions or committees. 4.6 Public health regulation

4.5 Environmental regulation Public health regulation is defined as the

establishment, monitoring (surveillance) of

Environmental regulation is defined as the implementation and/or enforcement, of a set

establishment and implementation of a set of of specific rules to ensure drinking water safety

specific rules applicable to water abstractions and safe management of the sanitation chain, in

and sanitation chain management, in order to order to protect public health.

protect the environment.

Regulations should include requirements for

Environmental regulation of water abstractions monitoring priority substances and for preventive

may involve a variety of options, with various risk management, such as Water Safety Planning

levels of effectiveness and cost. Generally, a (WSP). Often the term “standard” is used to

regulatory authority would establish a registry describe the mandatory numerical value in a

of existing abstraction points and require all table of parameters and limits. These standard

new applicants wanting to develop a new requirements are usually established at the

water abstraction to obtain authorization in national or sub-national level and often in

advance. Authorization would include a fee, alignment with the WHO Guidelines for Drinking

typically aimed to cover administrative costs. Water Quality. Operators then monitor and

To grant an abstraction license, a regulatory report to the regulator on compliance against

authority would need to assess the impact of the standards and norms. Support for such

the planned abstraction on the environment, and monitoring activities may be provided at the

on the existing usages and availability of water national level, especially for carrying out more

resources; as well as to assess whether the expensive testing activities. The regulatory body

water quality of the source matches the intended should gather, assess, and publish drinking

use. The licensed abstractors may be required water safety and WSP compliance data. Other

to monitor their abstractions (in quantity and activities to be carried out by the regulator

quality) over time and report on compliance with should include auditing WSPs, where WSP are

an issued license. required or promoted, carrying out sanitary

inspections (particularly where WSPs are not

Environmental regulation along the sanitation required), conducting water quality testing

chain (including for both “off-site” networked to complement the testing carried out by the

sanitation and on-site sanitation) can be done water supplier, and monitoring and investigating

in different ways. Commonly, a regulatory drinking water safety failure events and

authority regulates the quantity and quality consumer complaints. In the event of a drinking

standards of discharges and the treatment/ water safety failure event, the regulatory body

use/disposal of wastewater, effluent, and faecal may instruct the service provider to remediate

sludge, to prevent heavily polluting substances the damage, compensate for damages, or to

from being released into the environment, strengthen operations, including introducing or

and to ensure minimum environmental water improving WSPs. Detailed guidance has been

flows in receiving waterbodies (in the case of developed by the WHO on “Developing drinking-

urban wastewater discharges). The licensed water quality regulations and standards” (WHO,

dischargers or users/disposers may be required 2018)

to monitor their discharges/uses/disposals over

time, and report on compliance with an issued Public health regulation for safe management

license or standard. In the event of a serious of the sanitation chain is an emerging area of

non-compliance event, the regulatory body may regulation. Relevant legislation and regulation

coordinate an investigation and instruct the and elements may be found under local

13 | THE WASHREG APPROACH: AN OVERVIEW

government public health, occupational sludge treatment and specific standards for safe

health and safety, environmental, water use of wastewater and sludge according to the

resources, amongst other areas (WHO, 2018). use type. There is hence a strong interconnection

The regulation of the safe management of between public health, service quality regulation

the sanitation chain should use risk-based and environment in sanitation regulation.

approaches to set health-based standards at

each step of the chain. Multiple regulators may Regulators may establish a requirement for local

be involved in deploying a variety of regulatory authorities to carry out Sanitation Safety Planning

mechanisms at each step of the sanitation (SSP) to ensure risk-based improvements are

chain such as planning and building regulation monitored and coordinated among service providers

standards for toilets and on-site treatment at the local level. Finally, incentives or sanctions may

technologies, licencing of faecal sludge emptying be imposed on sanitation chain operators and end

and transport service providers, occupational users of sanitation products, for actions that infringe

health and safety regulations to protect workers, the health-based standards.

and minimum standards for wastewater and

5. THE REGULATORY CYCLE

Whichever regulatory area is analysed, with the aim for progressive improvement. These

regulatory activity can be divided into three regulatory powers apply to each of the regulatory

main regulatory powers, that can be organized areas defined in section 4- Tariff setting, Service

in a cyclical process (Figure 4). First, Rule Quality, Competition, Consumer protection,

definition and Approval Granting it is about Environment and Public Health.

defining and setting the regulation rules, as

well as granting the approvals required

for operating water and sanitation related

services. Secondly, Monitoring and Informing

is about collection of the information and

data needed to regulate, and making the

information available to the service providers

and public. Thirdly, Enforcement is about

the mechanisms developed to enforce

compliance with the defined rules. The

results of the assessment of the information

gathered through monitoring, as well as

results of enforcement, should inform

updates of the regulations and supporting

programmes,

Figure 4: The Regulatory Cycle

THE WASHREG APPROACH: AN OVERVIEW | 14

6. WORKING WITH REGULATION: THE

WASHREG APPROACH´S METHODOLOGY

As previously explained, there is no single systematic approach structured in line with this

model for a good regulatory framework, or for concept note (see Figure 5), to help decision-

its implementation. Every country has its own makers and practitioners better understand

institutional and legal settings, each facing a wide the challenges and different approaches, and

range of different challenges. Hence, there is the help them to implement regulatory objectives.

need to have a structured analysis of each situation, Once conducted, the WASHREG Approach´s

in order to be able to assess and improve the Methodology results in a set of actions and

performance of regulation in a given country. practical solutions conceived to initiate a

process of developing, strengthening, or

The WASHREG Approach´s Methodology is aligning regulatory roles and responsibilities.

a multi-stakeholder diagnosis, proposed to The WASHREG Approach´s Methodology and

identify national regulation gaps and challenges Annexes provides a detailed description of the

in water and sanitation services provision. It is a process, and how to facilitate it.

Figure 5: WASHREG Approach´s Methodology

15 | THE WASHREG APPROACH: AN OVERVIEW

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Allan, T. (2001). The Middle East Water Question: GLAAS data. Water Alternatives, 11(2), 238–259.

Hydropolitics and the Global Economy. I.B.Tauris & http://www.water-alternatives.org/index.php/alldoc/

Co. Ltd. articles/vol11/v11issue2/435-a11-2-2

Baldwin, R., Cave, M., & Lodge, M. (2012). Jiménez, A., Saikia, P., Giné, R., Avello, P., Leten,

Understanding regulation: theory, strategy, and J., Lymer, B. L., Schneider, K., & Ward, R. (2020).

practice. Oxford University Press on Demand. Unpacking water governance: A framework for

practitioners. Water (Switzerland), 12(3), 827.

Cabrera, E., & Cabrera, E. (2016). Regulation https://doi.org/10.3390/w12030827

of Urban Water Services. An Overview. In Water

Intelligence Online (Vol. 15, Issue 0). https://doi. Lodge, M. (2001). Regulatory accountability:

org/10.2166/9781780408187 towards a single citizen-consumer model? In

Challenges to Democracy (pp. 205–219). Springer.

Coase, R. H. (1960). The problem of social cost. In

Classic papers in natural resource economics (pp. Majone, G. (1997). From the positive to the regulatory

87–137). Springer. state: Causes and consequences of changes in the

mode of governance. Journal of Public Policy, 139–167.

General Assembly. (2018). Human rights to

safe drinking water and sanitation: report on Morgan, B., & Yeung, K. (2007). An introduction to

Accountability A/73/162. law and regulation: text and materials. Cambridge

University Press.

Gerber, B. J., & Teske, P. (2000). Regulatory

policymaking in the American states: A review of Mumssen, Y., Saltiel, G., Kingdom, B., Sadik,

theories and evidence. Political Research Quarterly, N., & Marques, R. (2018). Regulation of Water

53(4), 849–886. Supply and Sanitation in Bank Client Countries.

Regulation of Water Supply and Sanitation in

Graham, C. (1995). Is there a crisis in regulatory Bank Client Countries, November. https://doi.

accountability? Chartered Institute of Public Finance org/10.1596/30869

and Accountability.

OECD. (2014a). Applying better regulation in the

Heller, L. (2017). Service Regulation and the human water service sector. November, 94.

rights to water and sanitation A/HRC/36/45.

OECD. (2014b). The Governance of Regulators.

Internation Water Association. (2015). The Lisbon https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264209015-en

Charter: Guiding the Public Policy and Regulation of

Drinking Water Supply, Sanitation and Wastewater OECD. (2015). The Governance of Water Regulators

Management Services. 16. http://www.iwa-network. Results of the OECD Survey on the Governance of Water

org/downloads/1428787191-Lisbon_Regulators_ Regulators. In The Governance of Water Regulators.

Charter.pdf https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264231092-en

Jaime Melo Baptista. (2014). The Regulation of Water Pigou, A. C. (1920). The economics of welfare.

and Wastte services. In IWA Publishing (Vol. 53, Issue 9). Palgrave Macmillan.

Jiménez, A., Livsey, J., Åhlén, I., Scharp, C., Posner, R. A. (1974). Theories of economic

& Takane, M. (2018). Global assessment of regulation. National Bureau of Economic Research.

accountability in water and sanitation services using

THE WASHREG APPROACH: AN OVERVIEW | 16

Rouse, M. (2013). Institutional governance and UNDP-SIWI Water Governance Facility & UNICEF.

regulation of water services. In IWA Publishing (2015). WASH and Accountability: Explaining

(Issue AUG.). IWA publishing. https://doi. the Concept. http://www.watergovernance.org/

org/10.2166/9781780401973 resources/accountability-in-wash-explaining-the-

concept/

Rovizzi, L., & Thompson, D. (1992). The regulation

of product quality in the public utilities and the UNICEF. (2016). Strengthening enabling

Citizen’s Charter. Fiscal Studies, 13(3), 74–95. environment for water, sanitation and hygiene

(WASH): guidance note. May, 58.

Shleifer, A. (2005). Understanding regulation.

European Financial Management, 11(4), 439–451. UNICEF & WHO. (2017). Progress on Drinking

Water , Sanitation and Hygiene. Launch Version

Smoke, P. (2015). Accountability and service July 12 Main Report Progress on Drinking Water ,

delivery in decentralising environments: Sanitation and Hygiene.

Understanding context and strategically advancing

reform. A Governance Practitioner’s Notebook, 219. UNICEF, & UNDP/SIWI. (2016). WASH

accountability mapping tools: Vol. Accountabi.

Stigler, G. J. (1971). The theory of economic

regulation. The Bell Journal of Economics and World Health Organization (WHO). (2018).

Management Science, 3–21. Guidelines on sanitation and health. In World

Health Organization. World Health Organization.

Strande, L., Ronteltap, M., & Brdjanovic, D. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/hand

(2014). Faecal Sludge Management: Systems le/10665/274939/9789241514705-eng.pdf?ua=1

Approach for Implementation and Operation. In

L. Strande, M. Ronteltap, & D. Brdjanovic (Eds.),

IWA Publishing. IWA Publishing. https://doi.

org/10.13140/2.1.2078.5285

Trémolet, S. (2013). Regulation in rural areas. Water

Services That Last.

Stockholm International Water Institute

Linnégatan 87A, 100 55, Stockholm, Sweden

Phone: +46 8 121 360 00

UNICEF Water, Sanitation and Hygiene

UNICEF Headquarters

3 UN Plaza New York

Phone: +1 212 326 7000

Email: wash@unicef.org

You might also like

- Mainstreaming Water Safety Plans in ADB Water Sector Projects: Lessons and ChallengesFrom EverandMainstreaming Water Safety Plans in ADB Water Sector Projects: Lessons and ChallengesNo ratings yet

- Manuscript Clean Final Track Changes AnonymousDocument28 pagesManuscript Clean Final Track Changes AnonymousmvulamacfieldNo ratings yet

- WHO FWC WSH 17.03 EngDocument44 pagesWHO FWC WSH 17.03 EngRafaella BarachoNo ratings yet

- GLAAS 2017 Report For Web - FinalDocument96 pagesGLAAS 2017 Report For Web - FinalNewsBharatiNo ratings yet

- Global SDG Baseline For WASH in Health Care Facilities Practical Steps To Achieve Universal WASH in Health Care Facilities Questions and AnswersDocument3 pagesGlobal SDG Baseline For WASH in Health Care Facilities Practical Steps To Achieve Universal WASH in Health Care Facilities Questions and Answersعمرو عليNo ratings yet

- What Has Been The Role of Global Actors and ActionsDocument17 pagesWhat Has Been The Role of Global Actors and ActionsWei Wu XianNo ratings yet

- GHD 2023 Fact Sheet EnglishDocument7 pagesGHD 2023 Fact Sheet EnglishAbakule BoruNo ratings yet

- Building On A Decade of Progress in Water, Sanitation and Hygiene To Control, Eliminate and Eradicate Neglected Tropical DiseasesDocument3 pagesBuilding On A Decade of Progress in Water, Sanitation and Hygiene To Control, Eliminate and Eradicate Neglected Tropical DiseasesMstNo ratings yet

- Towards More Sustainable Sanitation SolutionsDocument4 pagesTowards More Sustainable Sanitation SolutionsRosie ReateguiNo ratings yet

- AgendaForChange GlobalStrategy Final-EnGDocument16 pagesAgendaForChange GlobalStrategy Final-EnGJuan Victor SeminarioNo ratings yet

- One Wash Concept Note May2019Document10 pagesOne Wash Concept Note May2019ceoNo ratings yet

- NGO Project Proposal SampleDocument10 pagesNGO Project Proposal SampleBirhanu TeshaleNo ratings yet

- Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) (Draft)Document18 pagesMemorandum of Understanding (MoU) (Draft)MERHAWIT NEGATUNo ratings yet

- PHAST LawsDocument11 pagesPHAST Lawsrodgers omondiNo ratings yet

- GHD 2022 Fact SheetDocument8 pagesGHD 2022 Fact SheetTako PruidzeNo ratings yet

- Status of Implementation of 7th SACOSAN CommittmentsDocument5 pagesStatus of Implementation of 7th SACOSAN CommittmentsProdip RoyNo ratings yet

- Air Sanitasi Dan Kebersihan Di PuskesmasDocument5 pagesAir Sanitasi Dan Kebersihan Di PuskesmasJulian GressandoNo ratings yet

- What Are The Benefits of Safe Water Supply and Sanitation?: Respecting Human ValuesDocument5 pagesWhat Are The Benefits of Safe Water Supply and Sanitation?: Respecting Human ValueslantaencNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0048969721038614 MainDocument12 pages1 s2.0 S0048969721038614 MainLiezl Andrea Keith CastroNo ratings yet

- Guidelines - Aceh and NiasDocument25 pagesGuidelines - Aceh and NiasBenny Aryanto SihalohoNo ratings yet

- Concept NoteDocument11 pagesConcept Noteaugustine amaraNo ratings yet

- Watershed - Empowering Citizens Programme and WAI WASH SDG Programme in BangladeshDocument42 pagesWatershed - Empowering Citizens Programme and WAI WASH SDG Programme in BangladeshMogesNo ratings yet

- CEEW Veolia Urban Water and Sanitation in India Nov13Document168 pagesCEEW Veolia Urban Water and Sanitation in India Nov13jeyankarunanithiNo ratings yet

- Water-Sensitive Informal Settlement Upgrading:: Overall Principles and ApproachDocument46 pagesWater-Sensitive Informal Settlement Upgrading:: Overall Principles and ApproachadyayatNo ratings yet

- DFID 20WASH 20portfolio 20review PDFDocument87 pagesDFID 20WASH 20portfolio 20review PDFCristi SandruNo ratings yet

- DFID 1998 Guidance Manual On Water Supply and Sanitation ProgrammesDocument356 pagesDFID 1998 Guidance Manual On Water Supply and Sanitation ProgrammesDan Tarara100% (1)

- Advocacy SourcebookDocument118 pagesAdvocacy SourcebookMat SCNo ratings yet

- New Problem StatementDocument4 pagesNew Problem StatementVogz KevogoNo ratings yet

- Pakistan Floods 2010: Evaluation of CARE's DEC Phase 1 and DFID Dadu ProjectsDocument32 pagesPakistan Floods 2010: Evaluation of CARE's DEC Phase 1 and DFID Dadu ProjectskashiNo ratings yet

- Regional and Global Costs For WAHDocument28 pagesRegional and Global Costs For WAHHelder MbidiNo ratings yet

- MWM Water Discussion PaperDocument17 pagesMWM Water Discussion PaperGreen Economy CoalitionNo ratings yet

- Washdev 0080176Document20 pagesWashdev 0080176Rajarshi BanerjeeNo ratings yet

- Unit 1 1 Tilley Et Al EST2014Document6 pagesUnit 1 1 Tilley Et Al EST2014Nguyen HuyNo ratings yet

- Ijerph 17 04528Document17 pagesIjerph 17 04528Abdul HadiNo ratings yet

- Assessing Sustainability of Wash Projects in Public and Private Schools of Jalalabad City Nangarhar 13475Document6 pagesAssessing Sustainability of Wash Projects in Public and Private Schools of Jalalabad City Nangarhar 13475Farman UllahNo ratings yet

- Hand Hygiene For All Initiative: Improving Access and Behaviour in Health Care FacilitiesDocument16 pagesHand Hygiene For All Initiative: Improving Access and Behaviour in Health Care FacilitiesMai BasionyNo ratings yet

- UNICEF SanitationMonitoring Toolkit 2Document90 pagesUNICEF SanitationMonitoring Toolkit 2Ulil RukmanaNo ratings yet

- Report 11Document28 pagesReport 11Jyothsna GopisettiNo ratings yet

- Baldwin, Gunnar. The Role of International Standard-Setting BodiesDocument6 pagesBaldwin, Gunnar. The Role of International Standard-Setting Bodiesammoj850No ratings yet

- Benjamin Dissertation 2-2-22 CommentsDocument29 pagesBenjamin Dissertation 2-2-22 Commentsbusinge benjaminNo ratings yet

- A Review of The Community Health Club Literature Describing Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene OutcomesDocument33 pagesA Review of The Community Health Club Literature Describing Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene OutcomesJheyDyraNo ratings yet

- ORF OccasionalPaper 250 CleanWaterSanitationDocument56 pagesORF OccasionalPaper 250 CleanWaterSanitationSelin PınarNo ratings yet

- Household EngDocument76 pagesHousehold EngLjiljana MilenkovNo ratings yet

- 2020 Water AccountingDocument87 pages2020 Water AccountingPaulaNo ratings yet

- JMP 2018 Core Questions For Household Surveys PDFDocument24 pagesJMP 2018 Core Questions For Household Surveys PDFKim Alvic Bantilan SaldoNo ratings yet

- JMP 2018 Core Questions For Household SurveysDocument24 pagesJMP 2018 Core Questions For Household SurveysNajeebullah MandokhailNo ratings yet

- Sustainability in The Water Energy Food NexusDocument11 pagesSustainability in The Water Energy Food NexusAntoiitbNo ratings yet

- Addressing The Policy Implementation Gaps in Water Services The Key Role of Meso Institutions PDFDocument22 pagesAddressing The Policy Implementation Gaps in Water Services The Key Role of Meso Institutions PDFGino MontenegroNo ratings yet

- Review of Public Financing For Water Sanitation AnDocument7 pagesReview of Public Financing For Water Sanitation AnNgoc Tram VanNo ratings yet

- Sanitation Safety Planning As A Tool For Achieving Safely Managed Sanitation Systems and Safe Use of WastewaterDocument7 pagesSanitation Safety Planning As A Tool For Achieving Safely Managed Sanitation Systems and Safe Use of WastewaterMashaelNo ratings yet

- SDG6 Indicator Report 651 Progress-On-Integrated-Water-Resources-Management 2021 ENGLISH Pages-1Document111 pagesSDG6 Indicator Report 651 Progress-On-Integrated-Water-Resources-Management 2021 ENGLISH Pages-1mohdjibNo ratings yet

- All Systems Go!: Background Note For The Wash Systems SymposiumDocument10 pagesAll Systems Go!: Background Note For The Wash Systems Symposiumangela HustonNo ratings yet

- Water and SanitationDocument18 pagesWater and SanitationOlusegun TolulopeNo ratings yet

- Water Law ProjectDocument48 pagesWater Law ProjectSurabhi ChaturvediNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S2666535222000994 MainDocument9 pages1 s2.0 S2666535222000994 MainDea AmandaNo ratings yet

- J MP Report 2012Document66 pagesJ MP Report 2012sumanpuniaNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S2405844023010794 MainDocument29 pages1 s2.0 S2405844023010794 MainNizam AlynNo ratings yet

- Bookshelf: S Kip To Main Content S Kip To NavigationDocument50 pagesBookshelf: S Kip To Main Content S Kip To NavigationHyngz Twinceyy Tbh Zu'nghNo ratings yet

- GWP Strategy Towards 2020 PDFDocument28 pagesGWP Strategy Towards 2020 PDFSoenarto Soendjaja100% (1)

- Gender's Role in Rural Uganda's WASH ProjectsDocument18 pagesGender's Role in Rural Uganda's WASH ProjectsMariana MartinsNo ratings yet

- Water Quality Index For Measuring Drinking Water Quality in Rural Bangladesh: A Cross-Sectional StudyDocument12 pagesWater Quality Index For Measuring Drinking Water Quality in Rural Bangladesh: A Cross-Sectional StudyMd.Sakil AhmedNo ratings yet

- WASH Guidance Note Draft Updated LRDocument58 pagesWASH Guidance Note Draft Updated LRTirtharaj DhunganaNo ratings yet

- ISF UTS - 2015 - Local ScaleSanitationIndonesia - Legal Review ReportDocument86 pagesISF UTS - 2015 - Local ScaleSanitationIndonesia - Legal Review ReportMohamad Mova AlAfghaniNo ratings yet

- Effectiveness of Demonstration Technique On Hand Washing Practices Among School Children Aged 7 11 Years in Selected Schools of District MohaliDocument4 pagesEffectiveness of Demonstration Technique On Hand Washing Practices Among School Children Aged 7 11 Years in Selected Schools of District MohaliEditor IJTSRDNo ratings yet

- A Lively & Healthy MeDocument18 pagesA Lively & Healthy MeARACELI RAITNo ratings yet

- African Water Facility - 2021 Work Plan and Budget PDFDocument47 pagesAfrican Water Facility - 2021 Work Plan and Budget PDFhamiss tsumaNo ratings yet

- AAI - Water Utility of The Future SC FlyerDocument2 pagesAAI - Water Utility of The Future SC FlyerTracy KerehNo ratings yet

- NNP2Document94 pagesNNP2Abebe GedamNo ratings yet

- INDUSTRIAL ATTACHMENT REPORT by Shikhule Kevin IbrahimDocument34 pagesINDUSTRIAL ATTACHMENT REPORT by Shikhule Kevin IbrahimIbrahim Shikhule Kevin100% (8)

- UNICEF Ethiopia Humanitarian Situation Report No. 9 - September 2022Document15 pagesUNICEF Ethiopia Humanitarian Situation Report No. 9 - September 2022N SNo ratings yet

- Affidavit FormatDocument24 pagesAffidavit FormatLalit DalalNo ratings yet

- Sphere Standards: Water Supply, Sanitation and Hygiene Promotion (WASH)Document29 pagesSphere Standards: Water Supply, Sanitation and Hygiene Promotion (WASH)Sote BrilloNo ratings yet

- Handwashing and Hygiene Study Using Malunggay SoapDocument32 pagesHandwashing and Hygiene Study Using Malunggay Soapelizabeth torres100% (2)

- Personal Hygiene Brochure - BERNALDocument3 pagesPersonal Hygiene Brochure - BERNALBernal, Abegail I.No ratings yet

- TSA WinS Booklet Sanitation FINAL WEB 20181105Document68 pagesTSA WinS Booklet Sanitation FINAL WEB 20181105Reg Sevilla SibalNo ratings yet

- Module 5 Safety and Health at WorkDocument46 pagesModule 5 Safety and Health at WorkYhan Brotamonte BoneoNo ratings yet

- Module 3 - SociologyDocument74 pagesModule 3 - SociologyakshayaNo ratings yet

- Simavi Social Accountability Online ManualDocument30 pagesSimavi Social Accountability Online ManualAsghar Khan SalahNo ratings yet

- Yemen HNO 2023 FinalDocument113 pagesYemen HNO 2023 FinalfuadjshNo ratings yet

- CATALYZE MS4G Learning Brief - 1Document7 pagesCATALYZE MS4G Learning Brief - 1Estiphanos GetNo ratings yet

- Pas 220 2008Document35 pagesPas 220 2008Gameel Thabit100% (3)

- What Are Water-Related Diseases? Water-Related Diseases and Their Control - Options For IntegrationDocument23 pagesWhat Are Water-Related Diseases? Water-Related Diseases and Their Control - Options For IntegrationBilal MemonNo ratings yet

- Wins Narrative Report 2021Document4 pagesWins Narrative Report 2021NASSER ABDUL100% (1)

- Wash in School Implementation Action Plan SY. 2019-2020Document2 pagesWash in School Implementation Action Plan SY. 2019-2020RONALYN ALVAREZNo ratings yet

- Diarrhea New Edited 2Document82 pagesDiarrhea New Edited 2bharathNo ratings yet

- Seminar Setting: ObjectivesDocument34 pagesSeminar Setting: ObjectivesMary CallejaNo ratings yet