Professional Documents

Culture Documents

rgj9w7

Uploaded by

Stella SulartoOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

rgj9w7

Uploaded by

Stella SulartoCopyright:

Available Formats

Open Access Original

Article DOI: 10.7759/cureus.44237

Risk Factors for Post-appendectomy Surgical Site

Infection in Laparoscopy and Laparotomy -

Review began 08/05/2023

Retrospective Cohort Study

Review ended 08/21/2023

Published 08/28/2023 Amer Fayraq 1, 2 , Saif A. Alzahrani 3 , Ahmed G. Alsayaf Alghamdi 4 , Saleh M. Alzhrani 5 , Abdullmajeed A.

Alghamdi 6, 7 , Hashem B. Abood 8

© Copyright 2023

Fayraq et al. This is an open access article

distributed under the terms of the Creative 1. Preventive Medicine, King Abdullah International Medical Research Centre, Jeddah, SAU 2. Preventive Medicine,

Commons Attribution License CC-BY 4.0., King Abdulaziz Medical City, Jeddah, SAU 3. Preventive Medicine, Ministry of National Guard Health Affairs, Jeddah,

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, SAU 4. General Surgery, King Fahad General Hospital, Al Baha, SAU 5. General and Colorectal Surgery, King Fahad

and reproduction in any medium, provided

General Hospital, Al Baha, SAU 6. Preventive Medicine, Ministry of Health, Jeddah, SAU 7. Medical Directorate, Saudi

the original author and source are credited.

Royal Land Forces, Riyadh, SAU 8. Surgery, King Fahad General Hospital, Al Baha, SAU

Corresponding author: Amer Fayraq, amer.fayraq@gmail.com

Abstract

Background

Appendicitis is a frequent emergency condition. Surgical site infections (SSI) are a common complication of

appendectomy. Despite improvements in infection control, SSIs continue to cause harm, prolonged hospital

stays, and even death.

Objective

The objective of this study is to compare the risk of developing surgical site infections (SSIs) between open

laparotomy and laparoscopic appendectomies in Al-Baha, Saudi Arabia.

Methods

This retrospective cohort study compared laparotomy and laparoscopy for post-operative surgical site

infection among patients who underwent an appendectomy at King Fahad Hospital (KFH) in Albaha, Saudi

Arabia. Medical record numbers (MRNs) of patients who met the inclusion criteria were collected to build the

sampling frame. From the final sampling frame, simple random sampling using a random number generator

was used to draw a representative sample. Data were collected from the surgical health records of the

patients. The collected data included patients' demographics, comorbidities, presenting symptoms, ordered

imaging studies, pre-operative shaving, type and duration of surgery, intraoperative findings, and signs of

wound inflammation.

Results

The total number of patients included in the analysis was 256, who underwent surgery for acute appendicitis.

Among those who underwent laparoscopy, 5.7% had to be converted to open laparotomy. Signs of surgical

wound inflammation were found in 10.2% of the patients. Patients who underwent open laparotomy had a

significantly higher risk of wound infection (RR=3.1, p-value=0.001). Further analysis revealed an effect

modification of pre-operative shaving. Open laparotomy has a higher risk of wound infection among

patients who have not had pre-operative shaving (RR=4.1 vs. RR=2.6), while both risks were statistically

significant (p-value=0.033 and p-value=0.035), respectively. Complicated cases in intra-operative findings

were found to have a higher risk of post-appendectomy SSI.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates that laparoscopic appendectomy carries a lower risk of surgical site infection (SSI)

compared to open laparotomy. Additionally, pre-operative shaving of the surgical site was found to increase

the incidence of SSI. Healthcare providers can use this information to enhance their practice and reduce the

occurrence of surgical site infections. Whenever possible, laparoscopic appendectomy should be preferred

over open laparotomy due to its substantially lower SSI risk. We also recommend vigilant monitoring of

complicated appendectomy, particularly in cases of ruptured appendicitis, for signs of SSI.

Categories: Preventive Medicine, General Surgery, Infectious Disease

Keywords: surgical site infection (ssi), risk factors, laparotomy, laparoscopy, appendectomy

Introduction

Acute appendicitis is a common surgical emergency. Appendectomy for acute appendicitis is one of the most

commonly performed types of emergency surgery, with over 300,000 appendectomies performed annually in

How to cite this article

Fayraq A, Alzahrani S A, Alsayaf Alghamdi A G, et al. (August 28, 2023) Risk Factors for Post-appendectomy Surgical Site Infection in

Laparoscopy and Laparotomy - Retrospective Cohort Study. Cureus 15(8): e44237. DOI 10.7759/cureus.44237

the United States [1]. In Riyadh, between 1999 and 2003, 852 patients underwent appendectomy at King

Khalid University Hospital [2].

Surgical site infection (SSI) is a common complication of any surgical intervention and can be avoided. SSI is

one of the main causes of postoperative morbidity and mortality [3]. According to the Centers for Disease

Control and Prevention (CDC), SSI is an infection that occurs after surgery in the part of the body where the

surgery took place. SSIs can be superficial infections involving the skin only or more serious infections

involving tissues under the skin, organs, or implanted material [4].

Despite advances in infection control practices, including improved operating room ventilation, sterilization

methods, barriers, surgical technique, and availability of antimicrobial prophylaxis, SSIs remain a

substantial cause of morbidity, prolonged hospitalization, and death. SSI accounts for 20% of all healthcare-

associated infections (HAIs) and is associated with a 2- to 11-fold increase in the risk of mortality, with 75%

of SSI-associated deaths directly attributable to the SSI [5]. Surgical site infection is the most costly HAI

type, with an estimated annual cost of $3.3 billion and extending hospital length of stay by 9.7 days, with

the cost of hospitalization increasing by more than $20,000 per admission [5,6]. A systematic review of 35

studies found that the overall rate of infection for open appendectomies was 17.9% (CI: 95% with 10.4-25.3

infections/100 procedures), and the percentage for laparoscopic appendectomy was 8.8% (CI: 95% with 4.5-

13.2 infections/100 procedures) [6].

The choice of laparoscopic vs. open method to manage acute appendicitis is usually based on patient-

specific factors, such as physical build, cosmetic goals, especially in female patients, old age, and suspected

complicated appendix on radiological study peri-operatively. The laparoscopic approach is preferred due to

early postoperative recovery and less wound infection, as supported by the literature [7,8].

Despite significant efforts to prevent postoperative complications and increased knowledge regarding

preventive measures against surgical site infections (SSI), the burden of this complication remains a major

reason for morbidity and longer hospital stays. Identifying groups at risk and predisposing factors can reduce

the burden of the disease and lead to clinical recommendations that will reduce the prevalence of SSI.

Therefore, the aim of this study is to compare the risk of developing SSI between open laparotomy and

laparoscopic appendectomies in Al-Baha, Saudi Arabia.

Materials And Methods

Study setting

This retrospective cohort study compares laparotomy and laparoscopy in terms of postoperative surgical site

infection among patients who underwent an appendectomy at King Fahad Hospital (KFH) in Albaha, Saudi

Arabia. King Fahad Hospital is a tertiary center that receives patient referrals from eight various provinces

that are affiliated with the Albaha region.

Study population

All the patients who underwent appendectomy from January 2018 to December 2022 were eligible for

inclusion. Immunocompromised patients "receiving immunosuppression therapy, chemotherapy, or

diagnosed with HIV" and those who had appendectomy for an indication other than appendicitis were

excluded from the study. The exposure group was defined as patients having an elective laparotomy for

appendectomy of both genders, while controls included those who underwent laparoscopy of the same group

during the study period.

The sample size was calculated using an online calculator (riskcalc.org). The equation was built with 80%

power, 0.05 type I error, unexposed to the exposed ratio of three, and a relative risk of 10. The relative risk

was used according to a previous study having a similar objective to the current study [9]. The calculated

sample size was about 226. Due to the scarcity of Laparoscopy cases in the selected study period, further

inclusion from the years of 2018 and 2019 was done to satisfy the calculated sample size.

Medical record numbers (MRN) of patients who met the inclusion criteria were collected to build the

sampling frame. After collecting eligible patients in a sampling frame, simple random sampling using a

random number generator was used to select the controls who underwent laparoscopic appendectomy.

During the sampling procedure, a considerable exposure to control ratio of 1:3 was used.

To diagnose surgical site infection, the clinical team examined patients using CDC criteria. These criteria

include signs and symptoms such as localized pain or tenderness, localized swelling, erythema, heat, and

infection involvement or drainage.

Data collection

Data were collected from the surgical health records of the patients. An electronic instrument was designed

to store the data of the selected sample. The collected data included patients' demographics, comorbidities,

2023 Fayraq et al. Cureus 15(8): e44237. DOI 10.7759/cureus.44237 2 of 8

presenting symptoms, ordered imaging studies, pre-operative shaving, type and duration of surgery, intra-

operative findings, and signs of wound inflammation. The data collection took place from November 2022 to

January 2023.

Statistical analysis

The data analysis was performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences version 29.0 (IBM Inc..

Armonk, New York). Categorical variables were summarized by frequencies and proportions, while

continuous variables were summarized by the median and interquartile range (IQR) after applying the

Shapiro-Wilk normality distribution test. The exposure variable was the type of surgery (open laparotomy vs.

laparoscopy), and the event of interest was the development of signs of surgical wound inflammation.

Baseline characteristics and categorical variables were compared using the Chi-squared test. Significant

associations with the outcome variable were tested and treated as possible confounders, and significant

differences across were taken into consideration and reported. Due to the low number of events, multiple

adjustments of confounders were omitted.

Ethical considerations

The scientific research committee affiliated with the education, training center, and academic affairs of King

Fahad Hospital in Albaha, Saudi Arabia, granted ethical approval for this study (Ref number

KFHIRB/0311202119). After data collection was complete, all personal identifiers were removed and

replaced with serial numbers prior to data analysis. The collected information was used solely for research

purposes while ensuring patient privacy and confidentiality.

Results

The total included in the analysis was (256) patients who underwent surgery for acute appendicitis. The age

ranged from seven to 91 years with a median and IQR of (29, 21-36). Of the total, 57.4% were males, and

74.6% were Saudis. The most common comorbidity was diabetes mellitus among 4.7%, followed by

hypertension at 2.7%. Open surgery was performed on 24.2% of the total, while 75.8% underwent

laparoscopy. Of those who underwent laparoscopy, 2.1% were converted to open laparotomy. See the

comparison of the baseline characteristics shown in Table 1.

2023 Fayraq et al. Cureus 15(8): e44237. DOI 10.7759/cureus.44237 3 of 8

Open laparotomy Laparoscopic p-value

Gender

Male 48 (32.7%) 99 (67.3%)

<0.001

Female 14 (12.8%) 95 (87.2%)

Nationality

Saudi 44 (23%) 147 (77%)

0.275

Non-Saudi 18 (27.7%) 47 (72.3%)

Diabetes mellitus

Yes 5 (41.7%) 7 (58.3%)

0.17

No 57 (23.4%) 187 (76.6%)

Hypertension

Yes 3 (42.9%) 4 (57.1%)

0.634

No 59 (23.7%) 190 (76.3%)

Cardiovascular diseases

Yes 2 (33.3%) 4 (66.7%)

0.448

No 60 (24%) 190 (76%)

Coagulopathy

Yes 3 (50%) 3 (50%)

0.155

No 59 (23.6%) 191 (76.4%)

Other comorbidities

Yes 5 (20.8%) 19 (79.2%)

0.806

No 57 (24.6%) 175 (75.4%)

TABLE 1: Comparison of the baseline characteristics between open laparotomy and laparoscopy

surgeries of acute appendicitis patients

Approximately half of the patients (49.6%) had symptoms within 24 hours of presentation. The most

commonly reported symptom was tenderness in the right lower quadrant, with a frequency of 96.1%. Nausea

and vomiting were reported by 55.9% of patients, while anorexia was reported by 48.4% of patients.

Migration of pain was reported by 75.8% of patients. Rebound pain was reported by 67.2% of patients.

Elevated temperature was the least commonly reported symptom, with a frequency of 11.3%. Computed

tomography (CT) was done for two-thirds of the patients (68%), ultrasound was done for 28.1%, X-ray for

28.1%, and magnetic resonance imaging was done for only one patient (0.4%). In CT, fat stranding was the

most common finding (46.1%), followed by lymph node enlargement and fluid around the appendix among

27.7% and 23.4%, respectively. See CT findings shown in Table 2.

2023 Fayraq et al. Cureus 15(8): e44237. DOI 10.7759/cureus.44237 4 of 8

CT findings N %

Fat stranding 118 46.10%

Lymph node enlargement 71 27.70%

Fluid around appendix 60 23.40%

Cecal thickness 25 9.80%

Appendix not seen 16 6.30%

Fecalith 14 5.50%

Ileum thickness 14 5.50%

Unremarkable 6 2.30%

TABLE 2: Computed tomography findings for patients diagnosed with acute appendicitis

Pre-operative shaving was done for 34.8% of the patients using razors. Of all the patients who were included

in the study, 89.5% received more than one antibiotic. Out of all the surgeries that were carried out, 75.8%

were performed using laparoscopic techniques. Additionally, 5.7% of the laparoscopic cases had to be

converted to open surgery. See the surgery type and duration in (Table 3). Among all patients included in the

study, a majority of surgeries, specifically 69.2%, were completed in under 60 minutes. For 30% of patients,

surgeries lasted between 60 and 90 minutes. A small percentage, only 0.8%, of surgeries took longer than 90

minutes to complete. Intra-operative findings revealed that 62.9% of the patients had suppurative

appendicitis, 20.7% had early-stage appendicitis, and 16.4% had complicated appendicitis. Complicated

cases were those that were perforated, gangrenous, or manifested mass or abscess. On the other hand,

suppurative and early-stage cases were considered uncomplicated. For more detailed intra-operative

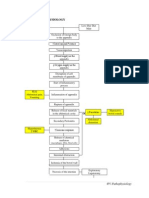

findings, refer to Figure 1.

N %

Surgery type

Open 62 24.20%

Laparoscopic 194 75.80%

Laparoscopic cases converted to open surgery

Yes 11 5.70%

No 183 94.30%

TABLE 3: Surgery types distribution among patients of acute appendicitis

2023 Fayraq et al. Cureus 15(8): e44237. DOI 10.7759/cureus.44237 5 of 8

FIGURE 1: Intraoperative findings of acute appendicitis patients

All included patients had a histopathological diagnosis of appendicitis. Additionally, other histopathological

findings were discovered in 31.3% of the patients. The length of stay (LOS) postoperatively was more than

24 hours for the majority of patients (70.7%). Surgical site infections were found among 10.2% of the

patients.

Patients who underwent open laparotomy had a significantly higher risk of wound infection (RR=3.1, p-

value=0.001). Further analyses revealed an effect modification of pre-operative shaving. Open laparotomy

has more risk of wound infection among patients who have not had pre-operative shaving (RR=4.1 vs.

RR=2.6), while both risks were statistically significant, p-value=0.033 and p-value=0.035, respectively. The

results on the risk of the type of surgery and pre-operative shaving are further detailed in Table 4.

Surgical site infection

RR (95%CI)

Yes No

Open laparotomy 13 (21%) 49 (79%)

Surgery type (Total) 3.1 (1.5-6.4)

Laparoscopic surgery 13 (6.7%) 181 (93.3%)

Stratified analysis

Open laparotomy 8 (34.8%) 15 (65.2%)

Pre-operative shaving (Yes) 2.6 (1.1-5.83)

Laparoscopic surgery 9 (13.6%) 57 (86.4%)

Open laparotomy 5 (12.8%) 34 (87.2%)

Pre-operative shaving (No) 4.1 (1.2-14.5)

Laparoscopic surgery 4 (3.1%) 124 (96.9%)

TABLE 4: Total and stratified analysis of the relation between surgery type, pre-operative shaving,

and surgical site infection among patients of acute appendicitis

Of the complicated cases, 31% manifested surgical site infections compared to 6.1% of the uncomplicated

cases. Therefore, it was found that complicated cases in intra-operative findings had a higher risk of surgical

site infection (RR=5.1). Stratified analysis was conducted to show the effect of surgery type on surgical site

infection among both groups of intra-operative findings (complicated and uncomplicated), which revealed a

small difference between the groups in the RR, 2.6 and 2.3, respectively. The association between

laparotomy and surgical site infection stratified by intra-operative findings was significant among the

complicated group only. This suggests that complicated appendicitis can be considered an independent risk

factor for surgical site infection.

Discussion

2023 Fayraq et al. Cureus 15(8): e44237. DOI 10.7759/cureus.44237 6 of 8

Surgical site infections remain a significant health problem that costs more than 320 million dollars in

developed countries [10]. However, the cost can vary greatly depending on the incidence rate from country

to country, which can lead to higher costs in lower-income countries. The overall incidence of SSI was

estimated to range from zero to 37.4, with a pooled estimate of 7/100 appendectomies, as reported in a

meta-analysis [11].

Our study, which included 256 patients, indicates that open laparotomy is associated with a higher risk of

surgical site infection (SSI) among patients undergoing appendectomy. Those who undergo laparotomy have

three times the risk of SSI compared to laparoscopic appendectomy. Similar findings were reported in a local

study in Saudi Arabia, which found that SSI had significantly higher odds among laparotomy patients

(OR=4.11) [12]. Furthermore, a systematic review found that the pooled SSI incidence was 17.9/100 open

laparotomies compared to 8.8/100 laparoscopic appendectomies [7]. On a larger scale, a meta-analysis also

reported a discrepancy in SSI rates between open laparotomy and laparoscopic procedures (11 vs. 4.6) per

100 appendectomies, respectively [11]. Although not statistically significant, another study reported that

laparotomy had higher rates of wound infection compared to laparoscopy (15.9% vs. 6.8%, respectively) [13].

In contrast to our results, Thomson et al. reported that wound sepsis, procedure duration, and length of

hospital stay did not show a statistical difference between open and laparoscopic appendectomies [14].

Further analysis of our results revealed that pre-operative shaving of the surgical site contributes to the

incidence of surgical site infections (SSIs). Our findings indicate that both laparoscopy procedures and hair

removal can significantly reduce the incidence of SSIs. In contrast to our results, previous studies have

indicated that pre-operative shaving does not increase the risk of SSIs nor provide a preventive effect against

them [15,16]. Although other studies have considered different methods of hair removal, the use of clippers

or chemical creams for hair removal had moderate certainty evidence of reducing the incidence of SSIs

compared to using a razor for hair removal [17].

Complicated appendectomy carries a higher risk of post-appendectomy surgical site infection (SSI)

independent of other factors, particularly evident among cases with ruptured appendicitis [18]. A systematic

review comparing delayed and primary wound closure for patients with contaminated wounds or

complicated appendicitis concluded that there is no superior method to reduce SSI [19]. Our results indicate

that the risk difference in SSI between complicated and non-complicated appendicitis was not substantial

(2.6% vs. 2.3%). However, the risk of SSI was statistically significant among those with complicated

appendicitis, which is consistent with previous studies identifying complicated appendicitis as an

independent risk factor for SSI [18,19]. Our findings align with those of Foster et al., who reported higher

pooled SSI rates among complicated cases (24.9% vs. 10.5%) [7].

The use of electronic instruments for standardized data collection reduced potential bias and increased

accuracy and efficiency. This study examined an important topic and provided valuable information for

healthcare providers to improve their practice and reduce surgical site infections. However, the study has

limitations. As a single-center study, the findings may not be generalizable to other settings. The

retrospective design may have limited data availability and quality. The study did not investigate other

potential risk factors for surgical site infections, such as obesity or smoking. Additionally, the study did not

consider the cost analysis of different surgical approaches, which could be an important factor for patients

and healthcare systems in decision-making.

Conclusions

The study indicates that laparoscopic appendectomy is associated with a lower risk of surgical site infection

(SSI) than open laparotomy. Furthermore, it has been discovered that shaving the surgical site before an

operation can increase the likelihood of surgical site infections (SSI). Additionally, complicated

appendectomy carries an independent higher risk of post-appendectomy SSI. Healthcare providers can use

this information to improve their practice and reduce surgical site infections. Whenever possible,

laparoscopic appendectomy is preferred over open laparotomy due to its significantly lower risk of SSI. We

also recommend close monitoring of complicated appendectomy, especially in cases of ruptured

appendicitis, for signs of SSI. By following these recommendations, healthcare providers can improve their

practice and reduce surgical site infections, ultimately leading to better patient outcomes.

Additional Information

Disclosures

Human subjects: Consent was obtained or waived by all participants in this study. King Fahad Hospital

issued approval KFHIRB/0311202119. The scientific research committee affiliated with the education,

training center, and academic affairs of King Fahad Hospital in Albaha, Saudi Arabia, granted ethical

approval for this study (Ref number KFHIRB/0311202119). Animal subjects: All authors have confirmed

that this study did not involve animal subjects or tissue. Conflicts of interest: In compliance with the

ICMJE uniform disclosure form, all authors declare the following: Payment/services info: All authors have

declared that no financial support was received from any organization for the submitted work. Financial

relationships: All authors have declared that they have no financial relationships at present or within the

2023 Fayraq et al. Cureus 15(8): e44237. DOI 10.7759/cureus.44237 7 of 8

previous three years with any organizations that might have an interest in the submitted work. Other

relationships: All authors have declared that there are no other relationships or activities that could appear

to have influenced the submitted work.

Acknowledgements

AF and SA contributed to the methodology of the study and the data management plan and tools, as well as

to the first draft of the manuscript. ASA and SA contributed to the literature search and data collection and

handling. AAA contributed to the statistical analysis of the data and data visualization. HA contributed to

the intellectual strategy and the scientific relevance of the study, as well as the proofreading of the final

manuscript.

References

1. Livingston EH, Fomby TB, Woodward WA, Haley RW: Epidemiological similarities between appendicitis and

diverticulitis suggesting a common underlying pathogenesis. Arch Surg. 2011, 146:308-14.

10.1001/archsurg.2011.2

2. Khairy G: Acute appendicitis: is removal of a normal appendix still existing and can we reduce its rate? .

Saudi J Gastroenterol. 2009, 15:167-70. 10.4103/1319-3767.51367

3. Ahmed K, Connelly TM, Bashar K, Walsh SR: Are wound ring protectors effective in reducing surgical site

infection post appendectomy? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ir J Med Sci. 2016, 185:35-42.

10.1007/s11845-015-1381-7

4. Owens CD, Stoessel K: Surgical site infections: epidemiology, microbiology and prevention . J Hosp Infect.

2008, 70:3-10. 10.1016/S0195-6701(08)60017-1

5. Zimlichman E, Henderson D, Tamir O, et al.: Health care-associated infections: a meta-analysis of costs and

financial impact on the US health care system. JAMA Intern Med. 2013, 173:2039-46.

10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.9763

6. Ban KA, Minei JP, Laronga C, et al.: American College of Surgeons and Surgical Infection Society: surgical

site infection guidelines, 2016 update. J Am Coll Surg. 2017, 224:59-74. 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2016.10.029

7. Foster D, Kethman W, Cai LZ, Weiser TG, Forrester JD: Surgical site infections after appendectomy

performed in low and middle Human Development-Index countries: a systematic review. Surg Infect

(Larchmt). 2018, 19:237-44. 10.1089/sur.2017.188

8. Tzovaras G, Baloyiannis I, Kouritas V, et al.: Laparoscopic versus open appendectomy in men: a prospective

randomized trial. Surg Endosc. 2010, 24:2987-92. 10.1007/s00464-010-1160-5

9. Mahmood MM, Shahab A, Razzaq MA: Surgical site infection in open versus laparoscopic appendectomy .

PJMHS. 2016, 10:1076-8.

10. Royle R, Gillespie BM, Chaboyer W, Byrnes J, Nghiem S: The burden of surgical site infections in Australia: a

cost-of-illness study. J Infect Public Health. 2023, 16:792-8. 10.1016/j.jiph.2023.03.018

11. Danwang C, Bigna JJ, Tochie JN, et al.: Global incidence of surgical site infection after appendectomy: a

systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2020, 10:e034266. 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-034266

12. Koumu MI, Jawhari A, Alghamdi SA, Hejazi MS, Alturaif AH, Aldaqal SM: Surgical site infection post-

appendectomy in a tertiary hospital, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. Cureus. 2021, 13:e16187. 10.7759/cureus.16187

13. Güler Y, Karabulut Z, Çaliş H, Şengül S: Comparison of laparoscopic and open appendectomy on wound

infection and healing in complicated appendicitis. Int Wound J. 2020, 17:957-65. 10.1111/iwj.13347

14. Thomson JE, Kruger D, Jann-Kruger C, Kiss A, Omoshoro-Jones JA, Luvhengo T, Brand M: Laparoscopic

versus open surgery for complicated appendicitis: a randomized controlled trial to prove safety. Surg

Endosc. 2015, 29:2027-32. 10.1007/s00464-014-3906-y

15. Rojanapirom S, Danchaivijitr S: Pre-operative shaving and wound infection in appendectomy . J Med Assoc

Thai. 1992, 75 Suppl 2:20-3.

16. Lefebvre A, Saliou P, Lucet JC, et al.: Preoperative hair removal and surgical site infections: network meta-

analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Hosp Infect. 2015, 91:100-8. 10.1016/j.jhin.2015.06.020

17. Tanner J, Melen K: Preoperative hair removal to reduce surgical site infection . Cochrane Database Syst Rev.

2021, 8:CD004122. 10.1002/14651858.CD004122.pub5

18. Siribumrungwong B, Srikuea K, Thakkinstian A: Comparison of superficial surgical site infection between

delayed primary and primary wound closures in ruptured appendicitis. Asian J Surg. 2014, 37:120-4.

10.1016/j.asjsur.2013.09.007

19. Siribumrungwong B, Noorit P, Wilasrusmee C, Thakkinstian A: A systematic review and meta-analysis of

randomised controlled trials of delayed primary wound closure in contaminated abdominal wounds. World J

Emerg Surg. 2014, 9:49. 10.1186/1749-7922-9-49

2023 Fayraq et al. Cureus 15(8): e44237. DOI 10.7759/cureus.44237 8 of 8

You might also like

- Infections in Surgery: Prevention and ManagementFrom EverandInfections in Surgery: Prevention and ManagementMassimo SartelliNo ratings yet

- Incidence of Wound Sepsis and Related Factors in Post-Operative Patients in Kampala International University Teaching Hospital Ishaka Bushenyi-Western UganDocument12 pagesIncidence of Wound Sepsis and Related Factors in Post-Operative Patients in Kampala International University Teaching Hospital Ishaka Bushenyi-Western UganKIU PUBLICATION AND EXTENSIONNo ratings yet

- Prevalence of Surgical Site Infections Among Surgical Operated Patients in Zewditu Memorial Hospital Addis Ababa EthiopiDocument10 pagesPrevalence of Surgical Site Infections Among Surgical Operated Patients in Zewditu Memorial Hospital Addis Ababa EthiopiAngelo Michilena100% (1)

- 10 1155@2019@1438793Document7 pages10 1155@2019@1438793bouchra8blsNo ratings yet

- Prevalence and Risk Factors of Surgical Site Infections in Fort Portal Regional Referral Hospital A Retrospective Cross-Sectional StudyDocument7 pagesPrevalence and Risk Factors of Surgical Site Infections in Fort Portal Regional Referral Hospital A Retrospective Cross-Sectional StudyKIU PUBLICATION AND EXTENSIONNo ratings yet

- Surgical Site Infections: Epidemiology, Microbiology and PreventionDocument8 pagesSurgical Site Infections: Epidemiology, Microbiology and Preventionm8wyb2f6ngNo ratings yet

- Surgical Site Infection in A Teaching Hospital: A Prospective StudyDocument7 pagesSurgical Site Infection in A Teaching Hospital: A Prospective StudymajedNo ratings yet

- Surgical Site Infections Latest Literature Update March 2019Document42 pagesSurgical Site Infections Latest Literature Update March 2019shah hassaanNo ratings yet

- Surgical Site Infection Following Abdominal SurgerDocument8 pagesSurgical Site Infection Following Abdominal SurgerJohn Ohene-PeprahNo ratings yet

- Post Caesarean Surgical Site Infections 2Document6 pagesPost Caesarean Surgical Site Infections 2saryindrianyNo ratings yet

- Risk Factors For Surgical Site InfectionDocument5 pagesRisk Factors For Surgical Site InfectionElizabeth Mautino CaceresNo ratings yet

- Prophylactic Antibiotics Before Gynecologic Surgery - A Comprehensive Review of GuidelinesDocument18 pagesProphylactic Antibiotics Before Gynecologic Surgery - A Comprehensive Review of GuidelinesLuisa MorenoNo ratings yet

- Antibiotic Prophylaxis in Blepharoplasty - Review of The Current Literature 2017Document5 pagesAntibiotic Prophylaxis in Blepharoplasty - Review of The Current Literature 2017María Alejandra Rojas MontenegroNo ratings yet

- Journal Homepage: - : Manuscript HistoryDocument11 pagesJournal Homepage: - : Manuscript HistoryIJAR JOURNALNo ratings yet

- 4147 15918 1 PBDocument7 pages4147 15918 1 PBI Made AryanaNo ratings yet

- A Study of Prevalence and Root Causes of Surgical Site Infections in An Acute Care Facility in Sharjah, United Arab EmiratesDocument23 pagesA Study of Prevalence and Root Causes of Surgical Site Infections in An Acute Care Facility in Sharjah, United Arab EmiratesInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- 47 (11), 761-767 PDFDocument7 pages47 (11), 761-767 PDFAdelinaArghireNo ratings yet

- Non-Medial Infectious Orbital Cellulitis: Etiology, Causative Organisms, Radiologic Findings, Management and ComplicationsDocument11 pagesNon-Medial Infectious Orbital Cellulitis: Etiology, Causative Organisms, Radiologic Findings, Management and ComplicationsPutri Sari DewiNo ratings yet

- Surgical Site InfectionDocument8 pagesSurgical Site Infection1234chocoNo ratings yet

- American College of Surgeons and Surgical Infection Society - Surgical Site Infection Guidelines, 2016 Update (SSI)Document16 pagesAmerican College of Surgeons and Surgical Infection Society - Surgical Site Infection Guidelines, 2016 Update (SSI)Anonymous LnWIBo1GNo ratings yet

- SudanMedMonit9281-3930827 105508Document6 pagesSudanMedMonit9281-3930827 105508Monika Diaz KristyanindaNo ratings yet

- Prophylactic Antibiotics For HemorrhoidectomyDocument5 pagesProphylactic Antibiotics For HemorrhoidectomyThắng NguyễnNo ratings yet

- Prevalence of Post Caesarean Wound Infections and Associated Factors Among Mothers Delivering From Kampala International University Teaching HospitalDocument14 pagesPrevalence of Post Caesarean Wound Infections and Associated Factors Among Mothers Delivering From Kampala International University Teaching HospitalKIU PUBLICATION AND EXTENSIONNo ratings yet

- 3767 11326 1 SMDocument9 pages3767 11326 1 SMGeztaNasafirHermawanNo ratings yet

- Theeffectoftriclosan CoatedsuturesontheincidenceofsurgicalsiteinfectioninlaparoscopicsleevegastrectomylaparoscopicappendicectomyorlaparoscopiccholecystectomyDocument9 pagesTheeffectoftriclosan CoatedsuturesontheincidenceofsurgicalsiteinfectioninlaparoscopicsleevegastrectomylaparoscopicappendicectomyorlaparoscopiccholecystectomyHardik ShahNo ratings yet

- Analysis of Risk Factors in Surgical Site Infection Following Caesarean SectionDocument7 pagesAnalysis of Risk Factors in Surgical Site Infection Following Caesarean SectionYosephine SantosoNo ratings yet

- Surgical Site InfectionsDocument29 pagesSurgical Site Infectionsalfredochelo1921No ratings yet

- Prevention of Surgical Site Infections: Pola Brenner, Patricio NercellesDocument10 pagesPrevention of Surgical Site Infections: Pola Brenner, Patricio NercellesAmeng GosimNo ratings yet

- Prevention of Surgical Site Infections: Pola Brenner, Patricio NercellesDocument10 pagesPrevention of Surgical Site Infections: Pola Brenner, Patricio NercellesAmeng GosimNo ratings yet

- Predictors of Mesh Infection and Explantation After Abdominal Wall Hernia RepairDocument8 pagesPredictors of Mesh Infection and Explantation After Abdominal Wall Hernia RepairOtto NaftariNo ratings yet

- Does An Antimicrobial Incision Drape Prevent.15Document9 pagesDoes An Antimicrobial Incision Drape Prevent.15Jimenez-Espinosa JeffersonNo ratings yet

- Screenshot 2022-09-26 at 20.14.44Document8 pagesScreenshot 2022-09-26 at 20.14.44Sutama ArtaNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0039606007003480 MainDocument8 pages1 s2.0 S0039606007003480 MainAna MîndrilăNo ratings yet

- 1-S2.0-S0039606022004056-Main 2Document6 pages1-S2.0-S0039606022004056-Main 2alihumoodhasanNo ratings yet

- Surgical Site Infection Prevention Among Nursing Staff at Kampala International University Teaching Hospital Bushenyi, UgandaDocument33 pagesSurgical Site Infection Prevention Among Nursing Staff at Kampala International University Teaching Hospital Bushenyi, UgandaKIU PUBLICATION AND EXTENSIONNo ratings yet

- Prevention, Diagnosis, and Management of Acute Postoperative Bacterial EndophthalmitisDocument16 pagesPrevention, Diagnosis, and Management of Acute Postoperative Bacterial EndophthalmitisNiñoTanNo ratings yet

- Surgery JournalDocument7 pagesSurgery JournalJane Arian BerzabalNo ratings yet

- Antibiotic Prophylaxis in Plastic Surgery: Journal ReadingDocument21 pagesAntibiotic Prophylaxis in Plastic Surgery: Journal ReadingRoby Aditya SuryaNo ratings yet

- Surgical Site InfectionDocument7 pagesSurgical Site InfectionCaxton ThumbiNo ratings yet

- Predictors of Surgical Site Infection in Laparoscopic and Open Ventral Incisional Herniorrhaphy - 2010 - Journal of Surgical ResearchDocument6 pagesPredictors of Surgical Site Infection in Laparoscopic and Open Ventral Incisional Herniorrhaphy - 2010 - Journal of Surgical ResearchJose Manuel Luna VazquezNo ratings yet

- Incidence and Risk Factors For Surgical Site Infection Following Elective Foot and Ankle Surgery: A Retrospective StudyDocument8 pagesIncidence and Risk Factors For Surgical Site Infection Following Elective Foot and Ankle Surgery: A Retrospective StudyFrancisco Castillo VázquezNo ratings yet

- Prevalence and Factors Associated With Surgical Site Infection in Post Caesarean MothersDocument10 pagesPrevalence and Factors Associated With Surgical Site Infection in Post Caesarean MothersKIU PUBLICATION AND EXTENSIONNo ratings yet

- Postoperative Infection and Mortality Following Elective Surgery in The International Surgical Outcomes Study (ISOS)Document32 pagesPostoperative Infection and Mortality Following Elective Surgery in The International Surgical Outcomes Study (ISOS)Antonio Carlos Betanzos PlanellNo ratings yet

- Epidemiology of Surgical Site Infection in A Tertiary Care Centre in North IndiaDocument7 pagesEpidemiology of Surgical Site Infection in A Tertiary Care Centre in North IndiaIJAR JOURNALNo ratings yet

- Wound Infections inDocument6 pagesWound Infections inprissyben17No ratings yet

- Wound Infection Incidence in Patients With Simple and Gangrenous or Perforated AppendicitisDocument4 pagesWound Infection Incidence in Patients With Simple and Gangrenous or Perforated AppendicitisRinamaria UlfahNo ratings yet

- Predictors of Surgical Site InfectionsDocument7 pagesPredictors of Surgical Site InfectionsMageNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0039606018302721 MainDocument7 pages1 s2.0 S0039606018302721 MainMelo Pérez Pamela J.No ratings yet

- Factores Asociados en Paises PobresDocument7 pagesFactores Asociados en Paises PobresMiluska Torrico CanoNo ratings yet

- Burden of Adhesions in Abdominal and Pelvic SurgeryDocument15 pagesBurden of Adhesions in Abdominal and Pelvic SurgeryDian AdiNo ratings yet

- Post-Operative Wound Infection: A Surgeon'S Dilemma: Original ArticleDocument7 pagesPost-Operative Wound Infection: A Surgeon'S Dilemma: Original ArticlePetit-Paul WedlyNo ratings yet

- Thesis Topic On Surgical Site InfectionDocument7 pagesThesis Topic On Surgical Site Infectionracheljohnstondesmoines100% (2)

- Is Cystic Enucleation With Peripheral Osteotomy Sufficient Treatment For Okcs of The Jaws?Document8 pagesIs Cystic Enucleation With Peripheral Osteotomy Sufficient Treatment For Okcs of The Jaws?IJAR JOURNALNo ratings yet

- Fcimb 12 962470Document15 pagesFcimb 12 962470wiwiNo ratings yet

- 2 Erewrf 242Document5 pages2 Erewrf 242supaidi97No ratings yet

- Faktor Resiko Infeksi SCDocument11 pagesFaktor Resiko Infeksi SCAlberto BrahmNo ratings yet

- 2019 Article 525Document8 pages2019 Article 525Diane MxNo ratings yet

- Incidence of Surgical Site Infection in Abdominal Surgery in A Tertiaty Care Center in AssamDocument6 pagesIncidence of Surgical Site Infection in Abdominal Surgery in A Tertiaty Care Center in AssamIJAR JOURNALNo ratings yet

- Coba Baca 36634-130622-2-PBDocument5 pagesCoba Baca 36634-130622-2-PBannisaNo ratings yet

- The Open Access Journal of Science and TechnologyDocument6 pagesThe Open Access Journal of Science and TechnologyNatalia SilahooyNo ratings yet

- 2020 World Society of Emergency Surgery Updated Guidelines For The Diagnosis and Treatment of Acute Calculus CholecystitisDocument26 pages2020 World Society of Emergency Surgery Updated Guidelines For The Diagnosis and Treatment of Acute Calculus CholecystitisDiego Andres VasquezNo ratings yet

- EASL CPG Gallstones PDFDocument36 pagesEASL CPG Gallstones PDFGabo Bravo RodríguezNo ratings yet

- rgj9w7Document8 pagesrgj9w7Stella SulartoNo ratings yet

- Otitis Media Diagnosis Nand TreatmentDocument6 pagesOtitis Media Diagnosis Nand TreatmentreyhanrrNo ratings yet

- Chapter 12 Siklus SelDocument47 pagesChapter 12 Siklus SelStella SulartoNo ratings yet

- Chapter 12 Siklus SelDocument47 pagesChapter 12 Siklus SelStella SulartoNo ratings yet

- Chapter 29 ProtistDocument37 pagesChapter 29 ProtistStella SulartoNo ratings yet

- General Surgery v1.0Document59 pagesGeneral Surgery v1.0SamiaNazNo ratings yet

- The Ship Captain's Medical Guide PDFDocument278 pagesThe Ship Captain's Medical Guide PDFIvo D'souza100% (2)

- Discharge SummaryDocument2 pagesDischarge SummaryJaslynn WhiteNo ratings yet

- AppendectomyDocument9 pagesAppendectomyMohsin Chaudhari100% (1)

- Disturbances of Gastrointestinal Tract (Git) : Alzbeta - Trancikova@Jfmed - Uniba.SkDocument57 pagesDisturbances of Gastrointestinal Tract (Git) : Alzbeta - Trancikova@Jfmed - Uniba.SkCharm MeelNo ratings yet

- Cabugao vs. PeopleDocument25 pagesCabugao vs. Peoplead infinitumNo ratings yet

- Causes of Abdominal Pain in Adults - UpToDateDocument13 pagesCauses of Abdominal Pain in Adults - UpToDateAudricNo ratings yet

- Surgical Site Infection (SSI) Event: Monthly Reporting PlanDocument31 pagesSurgical Site Infection (SSI) Event: Monthly Reporting PlanDRMC InfectioncontrolserviceNo ratings yet

- Peritonitis PDFDocument4 pagesPeritonitis PDFAndreas TheoNo ratings yet

- Surgery Ward NCPDocument1 pageSurgery Ward NCPElla MuskNo ratings yet

- Supplement Ch05Document16 pagesSupplement Ch05michellefrancis26100% (1)

- Management of Acute Abdomen in Pregnancy Current PerspectivesDocument16 pagesManagement of Acute Abdomen in Pregnancy Current PerspectivesjessicapxeNo ratings yet

- Appendicitis PathophysiologyDocument4 pagesAppendicitis PathophysiologyAngelica Cassandra VillenaNo ratings yet

- Diseases of Rectum and Anal CanalDocument68 pagesDiseases of Rectum and Anal CanalKoridor Falua Sakti Halawa 21000063No ratings yet

- LI - Physical Examination - AbdomenDocument6 pagesLI - Physical Examination - AbdomenTravis DonohoNo ratings yet

- Acute Intestinal ObstructionDocument50 pagesAcute Intestinal ObstructionDin LukbanNo ratings yet

- Surgical Case NCPDocument2 pagesSurgical Case NCPMaryjoy Gabriellee De La CruzNo ratings yet

- Combo Hospital Coding TestDocument7 pagesCombo Hospital Coding Testmscorella13% (8)

- WJR 8 656Document13 pagesWJR 8 656aldosaputraNo ratings yet

- Acute Abdomen and PeritonitisDocument17 pagesAcute Abdomen and PeritonitisAgatha Billkiss IsmailNo ratings yet

- Acute AbdomenDocument46 pagesAcute AbdomenErwin Siregar100% (2)

- Appendectomy Case StudyDocument16 pagesAppendectomy Case StudyMahmoud Al Abed100% (1)

- GitDocument23 pagesGitHannah Meriel Del MundoNo ratings yet

- Appendicitis in The Child With A Ventriculo-Peritoneal Shunt: A 30-Year ReviewDocument4 pagesAppendicitis in The Child With A Ventriculo-Peritoneal Shunt: A 30-Year ReviewAngel OlarteNo ratings yet

- NCP For Activity IntoleranceDocument1 pageNCP For Activity IntoleranceDaryl Paglinawan100% (4)

- Common Gastrointestinal Problems and Emergencies in Neonates and ChildrenDocument24 pagesCommon Gastrointestinal Problems and Emergencies in Neonates and ChildrenPatrick KosgeiNo ratings yet

- Department of General Surgery: Thermal Injuries Skin Grafts Acute AbdomenDocument115 pagesDepartment of General Surgery: Thermal Injuries Skin Grafts Acute AbdomenAj Christian Lacuesta IsipNo ratings yet

- Rife Frequencies by NumberDocument90 pagesRife Frequencies by Numbernepretip100% (5)

- Appendicular Abscess NewDocument4 pagesAppendicular Abscess NewkucingdekilNo ratings yet

- Case Study (Appendicitis)Document8 pagesCase Study (Appendicitis)Jobelle AcenaNo ratings yet

- Raising Mentally Strong Kids: How to Combine the Power of Neuroscience with Love and Logic to Grow Confident, Kind, Responsible, and Resilient Children and Young AdultsFrom EverandRaising Mentally Strong Kids: How to Combine the Power of Neuroscience with Love and Logic to Grow Confident, Kind, Responsible, and Resilient Children and Young AdultsRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Think This, Not That: 12 Mindshifts to Breakthrough Limiting Beliefs and Become Who You Were Born to BeFrom EverandThink This, Not That: 12 Mindshifts to Breakthrough Limiting Beliefs and Become Who You Were Born to BeNo ratings yet

- Summary: The Psychology of Money: Timeless Lessons on Wealth, Greed, and Happiness by Morgan Housel: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedFrom EverandSummary: The Psychology of Money: Timeless Lessons on Wealth, Greed, and Happiness by Morgan Housel: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (80)

- The Age of Magical Overthinking: Notes on Modern IrrationalityFrom EverandThe Age of Magical Overthinking: Notes on Modern IrrationalityRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (23)

- Summary: Outlive: The Science and Art of Longevity by Peter Attia MD, With Bill Gifford: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisFrom EverandSummary: Outlive: The Science and Art of Longevity by Peter Attia MD, With Bill Gifford: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (42)

- By the Time You Read This: The Space between Cheslie's Smile and Mental Illness—Her Story in Her Own WordsFrom EverandBy the Time You Read This: The Space between Cheslie's Smile and Mental Illness—Her Story in Her Own WordsNo ratings yet

- Gut: the new and revised Sunday Times bestsellerFrom EverandGut: the new and revised Sunday Times bestsellerRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (392)

- The Obesity Code: Unlocking the Secrets of Weight LossFrom EverandThe Obesity Code: Unlocking the Secrets of Weight LossRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5)

- The Body Keeps the Score by Bessel Van der Kolk, M.D. - Book Summary: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of TraumaFrom EverandThe Body Keeps the Score by Bessel Van der Kolk, M.D. - Book Summary: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of TraumaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Why We Die: The New Science of Aging and the Quest for ImmortalityFrom EverandWhy We Die: The New Science of Aging and the Quest for ImmortalityRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (3)

- Dark Psychology & Manipulation: Discover How To Analyze People and Master Human Behaviour Using Emotional Influence Techniques, Body Language Secrets, Covert NLP, Speed Reading, and Hypnosis.From EverandDark Psychology & Manipulation: Discover How To Analyze People and Master Human Behaviour Using Emotional Influence Techniques, Body Language Secrets, Covert NLP, Speed Reading, and Hypnosis.Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (110)

- 12 Rules for Life by Jordan B. Peterson - Book Summary: An Antidote to ChaosFrom Everand12 Rules for Life by Jordan B. Peterson - Book Summary: An Antidote to ChaosRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (207)

- The Courage Habit: How to Accept Your Fears, Release the Past, and Live Your Courageous LifeFrom EverandThe Courage Habit: How to Accept Your Fears, Release the Past, and Live Your Courageous LifeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (253)

- Raising Good Humans: A Mindful Guide to Breaking the Cycle of Reactive Parenting and Raising Kind, Confident KidsFrom EverandRaising Good Humans: A Mindful Guide to Breaking the Cycle of Reactive Parenting and Raising Kind, Confident KidsRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (169)

- The Ritual Effect: From Habit to Ritual, Harness the Surprising Power of Everyday ActionsFrom EverandThe Ritual Effect: From Habit to Ritual, Harness the Surprising Power of Everyday ActionsRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (3)

- Outlive: The Science and Art of Longevity by Peter Attia: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisFrom EverandOutlive: The Science and Art of Longevity by Peter Attia: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Algorithms to Live By: The Computer Science of Human DecisionsFrom EverandAlgorithms to Live By: The Computer Science of Human DecisionsRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (722)

- Sleep Stories for Adults: Overcome Insomnia and Find a Peaceful AwakeningFrom EverandSleep Stories for Adults: Overcome Insomnia and Find a Peaceful AwakeningRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (3)

- When the Body Says No by Gabor Maté: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisFrom EverandWhen the Body Says No by Gabor Maté: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2)

- ADHD is Awesome: A Guide to (Mostly) Thriving with ADHDFrom EverandADHD is Awesome: A Guide to (Mostly) Thriving with ADHDRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- The Garden Within: Where the War with Your Emotions Ends and Your Most Powerful Life BeginsFrom EverandThe Garden Within: Where the War with Your Emotions Ends and Your Most Powerful Life BeginsNo ratings yet

- Mindset by Carol S. Dweck - Book Summary: The New Psychology of SuccessFrom EverandMindset by Carol S. Dweck - Book Summary: The New Psychology of SuccessRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (328)

- An Autobiography of Trauma: A Healing JourneyFrom EverandAn Autobiography of Trauma: A Healing JourneyRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (2)