Professional Documents

Culture Documents

A14 2002febGallagherS58 73 2

Uploaded by

Zahra Ahmed AlzaherCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

A14 2002febGallagherS58 73 2

Uploaded by

Zahra Ahmed AlzaherCopyright:

Available Formats

. . . REPORTS . . .

Migraine: Diagnosis, Management,

and New Treatment Options

R. Michael Gallagher, DO; and F. Michael Cutrer, MD

Abstract headache may be preceded by transient

Objective: The safety and tolerability of med- focal neurologic symptoms known as aura.

ications used to treat acute migraine attacks are Migraine is the most common primary

summarized, the classification of headaches and headache disorder for which patients

the causes of and diagnostic criteria for migraine

present to primary care physicians, yet

are reviewed, and the clinical tolerability profiles

it remains underdiagnosed and under-

and therapeutic benefits of second-generation trip-

tans are presented.

treated.1,2 Migraine sufferers are often the

Background: Migraine is a paroxysmal disor- most dissatisfied patients; less than 30% of

der characterized by attacks of headache, nau- sufferers report that they are very satisfied

sea, vomiting, photophobia, and phonophobia. with their usual migraine treatment.3,4

Drugs used to prevent migraine and those that Almost two thirds of migraine sufferers

effectively treat acute migraine attacks are readily experience unwanted side effects from

available. antimigraine treatment. Those patients

Methods: Mild or moderate migraines are often often delay taking medication, which

treated with aspirin, acetaminophen, nonsteroidal results in prolonged pain and disability.5

anti-inflammatory drugs, antiemetic drugs, or

The prevalence of a family history of

isometheptene. Triptans (5-HT1 receptor agonists) are

migraine suggests that the disorder may

used to treat moderate or severe migraine and when

nonspecific medications have been ineffective.

have a genetic component.6 An estimated

Because sumatriptan, the first triptan used, is effective 6% of men and 15% to 17% of women in the

but can induce adverse events, second-generation United States experience migraine, but

triptans (zolmitriptan, naratriptan, rizatriptan, and only 3% to 5% of that population receive

almotriptan) were developed to increase the bene- preventive therapy.7 The prevalence of

fit-to-risk ratio in migraine management. migraine increased 60% (from 25.8 to 41

Results: Important pharmacologic, pharmaco- per 1000 population) from 1981 to 1989.8

kinetic, and clinical differences exist among those In addition, 2 studies conducted many

drugs, but the tolerability profile of the newer trip- years apart indicated that the incidence

tans is very good, and they provide rapid relief

of migraine in school children has

from headache and sustained duration of effect.

increased.9 Those data suggest that the

Conclusion: Primary care physicians must man-

age migraine patients with treatments that demon-

prevalence of migraine is increasing with

strate a balance between efficacy and tolerability. time; however, this increase could be the

(Am J Manag Care 2002;8:S58–S73) result of increased awareness of the disor-

der among physicians and patients.

Pathophysiology of Migraine

The characteristics of migraine vary in

igraine is a primary headache dis- frequency, duration, and the extent of dis-

M order characterized by recurring

attacks of throbbing (often unilat-

eral) headache, photophobia, phonopho-

ability produced among sufferers and

between attacks. Some migraine patients

experience fewer than 1 attack per month,

bia, nausea, and other symptoms. The and others suffer from 1 or more attacks

S58 THE AMERICAN JOURNAL OF MANAGED CARE FEBRUARY 2002

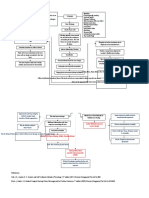

Migraine: Diagnosis, Management, and New Treatment Options

per week.10 Some migraine patients are

disabled by their headaches; others are Table 1. The International Headache

not. Therefore, the care provided to those Society Classification of Migraine

who suffer from migraine must be strati-

fied by the frequency and severity of the ■ Migraine without aura

headache and by the resultant level of ■ Migraine with aura

disability.11 Migraine with typical aura

Migraine with prolonged aura

Abnormalities in blood vessels may be

Familial hemiplegic migraine

important in the pathogenesis of migraine Basilar migraine

and the excessive muscle contraction of Migraine aura without headache

tension-type headaches, but current Migraine with acute onset aura

research suggests that headaches are pro- ■ Ophthalmoplegic migraine

duced by abnormalities in the central nerv- ■ Retinal migraine

ous system (CNS) regulation of blood Childhood periodic syndromes that may be

vessels within pain-producing intracranial precursors to or associated with migraine

meningeal structures.12,13 Evidence has Benign paroxysmal vertigo of childhood

Alternating hemiplegia of childhood

shown that changes in the level of serotonin

precede the changes in blood vessels and ■ Complications of migraine

Status migrainous

muscle tone that occur during chronic Migrainous infarction

headaches.12 The influence of serotonin on

■ Migrainous disorder not fulfilling above criteria

headache may also explain the effectiveness

of medications used to treat migraine.

The nature of the CNS dysfunction Source: Headache Classification Committee of the

produced in migraine patients is still International Headache Society. Classification and

diagnostic criteria for headache disorders, cranial

unclear and may involve spreading

neuralgias and facial pain. Cephalalgia 1988;8

depression-like phenomena and the acti- (suppl 7):1-96. Adapted with permission.

vation of brain stem monoaminergic

nuclei that are part of the central auto-

nomic, vascular, and pain-control centers. The IHS user-friendly classification con-

A proposed mechanism for the generation sists of 2 major categories: primary and

of migraine is that of local vasodilation of secondary headaches. Primary headaches

intracranial and extracerebral blood ves- (headache disorders in which an identifi-

sels and a consequent stimulation of sur- able pathologic factor is not present) con-

rounding trigeminal sensory nervous pain sist of migraine (with or without aura),

pathways.13 This activation of the trigemi- tension-type headaches (episodic or chron-

novascular system is thought to cause the ic), cluster headaches, posttraumatic head-

release of vasoactive sensory neuropep- aches, and rebound headaches caused by

tides (substance P, calcitonin–gene-related drug use or withdrawal. Secondary head-

peptide, neurokinin A, and others) that aches are symptoms of organic diseases

increase the pain response.13 The activated such as meningitis or cerebral tumors.

trigeminal nerves convey nociceptive infor- The IHS classification system provides

mation to central neurons in the brain stem valuable information about the diagnosis

trigeminal sensory nuclei, which in turn and treatment of headaches, but primary

relay the pain signals to higher centers that care physicians and neurologists are ulti-

may become sensitized as a migraine mately responsible for accurate diagnosis

attack progresses.13 and effective treatment. Migraine pro-

drome (phase 1 or preheadache period),

Diagnosis of Migraine which may occur hours to days before the

International Headache Society onset of headache, consists of nonfocal

Classification. The International Headache constitutional symptoms and can vary

Society (IHS) has developed the first clas- widely among patients. Some feel euphor-

sification system for migraine and other ic, and others may experience irritability

types of headaches (Tables 1 and 2).14,15 or extraordinary fatigue. Migraine post-

VOL. 8, NO. 3, SUP. THE AMERICAN JOURNAL OF MANAGED CARE S59

REPORTS

Medical History. Obtaining an accu-

Table 2. Diagnostic Criteria for Migraine Without Aura rate medical history is the first step in an

evaluation for migraine. Information

A. At least 5 attacks fulfilling the criteria of B to D below obtained should include the patient’s age at

B. Headache attacks lasting 4 to 72 hours (untreated or unsuccessfully first migraine; the site or sites of pain; the

treated) frequency, intensity, and duration of pain;

C. Headache with at least 2 of the following characteristics: the presence of any associated symptom

1. Unilateral location (eg, aura, dizziness); aggravating, precipi-

2. Pulsating quality tating, or ameliorating factors; prior med-

3. Moderate or severe intensity (inhibits or prohibits daily activities). ication use; caffeine intake; prior head

4. Intensified when patient walks up or down stairs or performs trauma; results of neuroimaging studies;

a similar activity and family history.16 The physician should

D. During headache, at least 1 of the following must occur: encourage the patient to keep a headache

1. Nausea and/or vomiting “diary” in which the characteristics of each

2. Photophobia or phonophobia headache and the response to treatment

E. At least 1 of the following must apply: are recorded. That type of diary is also valu-

1. History, physical, and neurologic examinations do not suggest able in helping the patient and physician

another disorder*

identify factors such as lifestyle, diet, men-

2. History and/or physical and/or neurologic examinations do suggest

strual cycle, and the overuse of medication

such a disorder, but it is ruled out by appropriate investigations

or caffeine, all of which may precipitate

3. Such a disorder is present, but migraine attacks do not occur for

the first time in close temporal relation to the disorder migraine.16

Physical Examination. After the

*Other disorders that may cause headache include head trauma; vascular patient’s medical history has been obtained,

and neurovascular disorders; substance use or withdrawal; noncephalic

a physical examination should be performed

infection; metabolic disorder; and disorders of the cranium, neck, eyes,

ears, nose, sinuses, teeth, mouth, or other facial or cranial structures. to evaluate (at the very least) blood pressure,

Source: Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache heart rate, extracranial structures (eg,

Society. Classification and diagnostic criteria for headache disorders, cranial sinuses, scalp arteries, temporomandibular

neuralgias and facial pain. Cephalalgia 1988;8(suppl 7):1-96. Adapted with joints), and the range of motion and pres-

permission.

ence of pain in the cervical spine.17 Addi-

tional laboratory tests and neuroimaging

drome appears as the pain wanes, after studies should not be necessary unless the

which the patient feels tired and listless. physician observes the following danger sig-

The clinical diagnosis of migraine with- nals: the sudden onset of a new type of

out aura requires that the patient experi- severe headache; headache onset during

ence at least 5 headaches with a duration of exertion; first headache in a middle-aged

4 to 72 hours. During migraine without patient; headache accompanied by loss of

aura, unilateral pain of moderate-to-severe consciousness or systemic illness (fever, stiff

intensity seems to pulsate, and patients neck, rash); headache associated with

must experience at least 1 of the following meningeal signs; an accelerating pattern of

symptoms: nausea, vomiting, photophobia, headache; new onset of headache in

or phonophobia.14 Such headaches are immunocompromised patients or those

often exacerbated by routine physical activ- with cancer; headache accompanied by

ity. However, during a migraine, approxi- signs of disease or focal neurologic symp-

mately 30% of migraine patients experience toms atypical for aura; and papilledema

an aura (usually visual) that precedes the (swelling of the optic disk).16 In those cases,

headache by 5 to 30 minutes, may reflect a referral for diagnostic imaging or neurologic

wide range of neural deficits, and fades with- testing is appropriate to rule out concomi-

in 30 minutes. It may first be noticed near tant illness that may cause headache.

the visual center as a small spot surround-

ed by bright, jagged lines. An aura that per- Treatment

sists for more than 1 hour may signal an Two types of treatment are available for

ischemic attack and should be evaluated.14 headaches: abortive (treatment of the

S60 THE AMERICAN JOURNAL OF MANAGED CARE FEBRUARY 2002

Migraine: Diagnosis, Management, and New Treatment Options

acute attack) and prophylactic (preven- tan drugs are highly effective when admin-

tion of headache by using medication istered early in this phase of migraine.

and/or nonpharmacologic measures to When migraine evolves into an advanced

lessen precipitating factors, such as stress stage (late headache) and first- and second-

or lifestyle). line treatments have failed, rescue therapy

must be considered. Intravenously admin-

Nonpharmacologic Measures of istered phenothiazines are often effective

Preventing Migraine. The suggestions and can be combined with dihydroergota-

below are recommended by a primary mine (DHE) or other serotonin agonists.

care physician for the nonpharmacologic Opioid analgesics are also used to treat late

management of migraine.18 headache.

• Maintain regular sleeping, eating, and Selecting Pharmacologic Agents

exercise habits. Simple Analgesics and NSAIDs. Simple

• Avoid excessive stress-producing analgesics, which may be used to treat

activities. mild-to-moderate acute migraine, are most

• Practice relaxation techniques. effective as first-line treatments when

• Avoid potential triggers such as trauma, used before the pain becomes severe.22

caffeine, and certain foods (eg, choco- Aspirin, which is both an analgesic and an

late, aged cheeses, red wine, foods con- NSAID, inhibits prostaglandin and

taining sodium nitrate). leukotriene synthesis.23 Acetaminophen

• Address possible underlying depression can also be used to treat mild-to-moderate

or anxiety. acute migraine.24 Ibuprofen and OTC com-

bination products containing aspirin, aceta-

Pharmacologic Treatment. Early inter- minophen, and caffeine have been approved

vention with appropriate medication can by the US Food and Drug Administration

completely abort a migraine so that the (FDA) for the treatment of mild-to-moder-

patient can function normally and a ate migraine. Patients should be cautioned

recurrence is prevented.19 Simple anal- that the overuse of all treatments for

gesics and nonsteroidal anti-inflammato- migraine, including triptans and OTC anal-

ry drugs (NSAIDs) may be used to treat gesics (especially combination products

mild-to-moderate headache or migraine containing caffeine) may cause rebound

that does not increase in intensity. headache.22

Triptans (5-HT1 receptor agonists) are the Prescription-strength NSAIDs such as

preferred therapy for moderate-to-severe ibuprofen, naproxen sodium, and ketoro-

headaches. In Table 3, therapies recom-

mended by primary care physicians for

patients with specific headache patterns Table 3. Medications Prescribed for Headaches by Primary

are presented.20,21 Care Physicians

During prodrome, many interventions

can be effective. Over-the-counter (OTC) Headache Pattern Suggested Therapy

or nonprescription products such as Mild-to-moderate migraine Nonspecific agents (eg, NSAIDs,

NSAIDs, serotonin receptor agonists, aspirin, combination medications)

acetaminophen, or a combination of aspirin Moderate or severe migraine; or Migraine-specific agents

and acetaminophen may prevent the poor response to NSAIDs and (eg, triptans, dihydroergotamine)

headache.19 If prodromal warning signs do combination medications

not occur or intervention fails to abort the Migraine associated with severe Nonoral route of administration

migraine in its early stage, migraine-spe- nausea or vomiting

cific medications such as triptans are Severe migraine that fails to Self-administered rescue

indicated. Headache characterized by pho- respond to other treatments medication

tophobia, phonophobia, and/or nausea and

vomiting suggests that the neurovascular NSAIDs = nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

inflammatory process has begun, and trip- Source: Reference 27.

VOL. 8, NO. 3, SUP. THE AMERICAN JOURNAL OF MANAGED CARE S61

REPORTS

lac are also effective treatments for mild- migraine.32 Suppression of the firing rate of

to-moderate migraine.25 Diclofenac, a pre- those serotonergic neurons and the subse-

scription-strength NSAID, reduced the quent stabilization of serotonergic neuro-

intensity of migraine pain and ameliorated transmission is thought to be one of the

associated symptoms such as photophobia modes of action of ET compounds.32

and phonophobia in a placebo-controlled, ET was first introduced for the treat-

double-blind, randomized clinical trial.26 If ment of migraine in the 1920s. However,

a moderate dose of an NSAID adminis- its bioavailability is poor and unpre-

tered at the onset of migraine is not com- dictable after oral administration.25 The

pletely effective within 1 hour, a triptan potent vasoconstrictor effect of ET, which

should be given.21 Cyclo-oxygenase-2 can last for up to 3 days, is undesirable.

inhibitors may be useful adjuncts for the When compared with ET, DHE is a more

treatment of migraine.27 potent α-adrenergic antagonist and is

therefore a potent vasoconstrictor. DHE is

Opioids. Opioids such as intramuscu- a more potent antiemetic than ET, has

larly or intravenously administered meperi- less effect on the uterus, and is not associ-

dine or orally administered codeine are used ated with rebound headache.25

because of their analgesic potential but may Caffeine in combination with analgesics

exacerbate nausea and vomiting and increase or ET improves the absorption of the med-

the risk of drug addiction.25 A clinical trial ication and also potentiates pain relief, pos-

involving patients treated in an emergency sibly as a result of its vasoconstrictor

department for acute migraine indicated effect.25 The combination of ET and caf-

that a combination of meperidine and feine, although effective in only 50% of

hydroxyzine reduced headache pain by patients, is a treatment option for acute

approximately 55%, ameliorated nausea, migraine.25 The efficacy of ET is enhanced

and was not statistically significantly differ- by the addition of pentobarbital and the

ent in effect (P < .05) from treatment with a levorotatory alkaloids of belladonna.

combination of DHE and hydroxyzine.28 Although complete evidence regarding the

efficacy of DHE is unavailable, intravenous

Antiemetics. Antiemetic drugs may be administration can abort approximately

used to treat acute migraine. Orally or 90% of attacks.33 In one study, DHE nasal

intravenously administered metoclo- spray significantly reduced the severity of

pramide, a dopamine antagonist that headache.34 In another double-blind, pla-

affects the 5-HT3 receptor, may provide cebo-controlled study of migraine patients,

relief from pain and nausea or vomiting.29 those who used an intranasal formulation

Patients should be advised that antiemet- of DHE as opposed to placebo experienced

ics often cause adverse events such as statistically significant migraine resolution

diarrhea, drowsiness, or restlessness. (ie, mild or no pain) within 4 hours of tak-

ing the drug (70% versus 28%, P < .001).35

Ergot Compounds. Ergot compounds In that study, the most common adverse

such as ergotamine (ET) or DHE were the events associated with intranasal DHE

first drugs used to treat migraine.25 Ergot were local, such as rhinitis (21% of

compounds are pharmacologically nonse- patients), nausea (4%), and taste perver-

lective but have been used successfully in sion (9%). Patients with ischemic heart dis-

patients with moderate-to-severe migraine ease, a history of myocardial infarction, or

since the turn of the century. Their clinical clinical signs of coronary artery disease

efficacy is at least equal to that of NSAIDs.30 should not take DHE.

They have agonist affinity for several Ergot compounds should not be pre-

different 5-HT receptors (5-HT1 A, B, D; scribed for pregnant patients or those with

5-HT2 A, B, C), dopamine receptors (DA2), peripheral vascular disease, hypertension,

and alpha-adrenergic receptors.31 The coronary heart disease, or impaired renal

great number of DHE-binding sites in the or hepatic function.25 The adverse events

dorsal raphe nuclei may precipitate produced by ergots include nausea, acro-

S62 THE AMERICAN JOURNAL OF MANAGED CARE FEBRUARY 2002

Migraine: Diagnosis, Management, and New Treatment Options

paresthesia, ischemia, habituation, and 1998. Almotriptan became available in the

ergot-dependent headache. According to United States in 2001, frovatriptan has

some research, reports of serious adverse been approved by the FDA, and FDA

events that occurred after recommended approval of eletriptan is pending. It was

doses of DHE were much fewer than hoped that those second-generation trip-

those associated with ET, and physical tans would be superior in effect to suma-

dependence did not occur.36 The most triptan by providing a shorter onset of

frequently noted adverse events with the action after oral administration, a longer

intravenous administration of DHE are half-life, greater oral bioavailability, and

nausea, vomiting, and leg cramps. However, improved tolerability.42 However, current

after intramuscular or intranasal adminis- clinical trial data pertaining to 2-hour pain

tration, the incidence of nausea and vomit- relief and pain-free endpoints suggest that

ing is low and concomitant administration the differences among triptans are subtle

of an antiemetic is not warranted. rather than dramatic. Some patients

found sumatriptan ineffective or difficult

Newer Antimigraine Drugs to tolerate, especially when administered

A new era in antimigraine drugs began in subcutaneously. Many of those patients

1973 with efforts to synthesize a more benefit from treatment with a newer trip-

selective 5-HT1 agonist. Prior research had tan or with the oral form of sumatriptan.

indicated that serotonin 5-HT (a potent The overall efficacy rates for all orally

vasoconstrictor and a pain modulator) was administered triptans is approximately

a factor in the generation of migraine.37 65%.42 However, patients may prefer one

Triptan antimigraine agents are serotoner- treatment as opposed to another.

gic agonists that act selectively. They cause Adverse events associated with triptans

vasoconstriction by affecting serotonin (5- include nausea, paresthesia, fatigue, som-

HT1B) receptors in human intracranial nolence, dizziness, pain, heaviness or

arteries and inhibit nociceptive transmis- tightness in the chest or throat, warm or

sion by their effect on 5-HT1D receptors on cold sensations, and dry mouth. Triptans,

peripheral trigeminal sensory nerve termi- like ergot-containing drugs, are con-

nals in the meninges and central terminal traindicated or prescribed with caution for

in brain stem sensory nuclei. Those com- those with uncontrolled blood pressure,

plementary sites of action are the basis of coronary artery disease, or peripheral vas-

the clinical effectiveness of those 2 types of cular disease.39

agonists in treating migraine pain and its

associated symptoms.13 Naratriptan. Naratriptan is a second-

generation drug approved for marketing

Sumatriptan. In 1991, sumatriptan, a as an oral formulation to abort migraine.

first-generation triptan, was introduced. The pharmacologic profile of naratrip-

Sumatriptan produces agonist effects at 3 tan is superior to that of sumatriptan; its

5-HT receptors (5-HT1B, 5-HT1D, and 5- bioavailability is about 60%, which

HT1F) and weaker effects at other 5-HT1 reduces the effective dose to 2.5 mg.42

receptors.38 It is about 5-fold more potent The half-life of naratriptan is about 6

at 5-HT1D receptors than at 5-HT1A recep- hours (2 to 3 times longer than that of

tors when compared with DHE, which is sumatriptan), which seems to slightly

about 10-fold more potent at 5-HT1A than lower the percentage of patients who

at 5-HT1D receptors.38 Sumatriptan experience recurrent migraine.43 However,

relieves migraine pain and associated clinical trials indicate that 2.5 mg of nara-

symptoms of nausea, vomiting, photopho- triptan is less effective than 100 mg of

bia, and phonophobia.39-41 sumatriptan but also produces fewer

adverse events. According to 1 study,

Second-Generation Triptans. Nara- adverse events produced by naratriptan

triptan, zolmitriptan, and rizatriptan included vomiting (7% of patients), nau-

entered the US market in late 1997 and sea (7%), and tingling (3%).41 Adverse

VOL. 8, NO. 3, SUP. THE AMERICAN JOURNAL OF MANAGED CARE S63

REPORTS

events reported in other clinical trials pharmacologic profile and an oral bio-

included dizziness, drowsiness, and availability of about 40%.40 Its half-life (2.5

malaise or fatigue (4% to 7%); paresthesia to 3 hours) is only slightly longer than that

(2% to 4%); and pain and pressure sensa- of sumatriptan. Rizatriptan has a more

tion (2% to 4%). The side effect of chest rapid onset (tmax < 1 hour) than other trip-

tightness is not mentioned on the product tans currently on the market.40 In clinical

label, which indicates that a low inci- trials, rizatriptan produced pain relief 2

dence of chest pain or pressure and throat hours after administration at doses rang-

or neck symptoms are associated with ing from 2.5 to 40 mg; a dose of 10 mg

naratriptan. It is important to note that produced the most benefit (52% of

the decreased frequency of chest symp- patients experienced relief from headache

toms associated with that drug does not and few adverse events).40 Common adverse

diminish the importance of alerting events included dizziness (in 4% of the

patients with active or potential coronary patients), nausea (3%), somnolence (3%),

artery disease or cardiac ischemia to their chest symptoms (2%), and fatigue (1%). As

potential occurrence. with other triptans, the number of adverse

events caused by rizatriptan was dose

Zolmitriptan. Zolmitriptan, the next dependent.

second-generation triptan to enter the

market, has an oral bioavailability of Newer Triptans. Eletriptan has an oral

approximately 50%, which exceeds that of bioavailability of almost 50%; it is rapidly

sumatriptan (14%).42 In addition, the half- absorbed (tmax < 1 hour) but has a half-life

life of zolmitriptan (3 hours) provided a of 5 hours.42 In 2 recent multicenter stud-

more prolonged therapeutic plasma con- ies, the efficacy and tolerability of eletrip-

centration than did sumatriptan. In a tan in acute migraine were examined. In

recent study, zolmitriptan was effective in the first study, doses of oral eletriptan 5,

relieving acute migraine 2 hours after 20, or 30 mg were studied in the treatment

administration at an oral dose of 2.5 mg of acute migraine in 365 patients.48 Two

(in 67% of the patients) or 5 mg (in 65%).44 hours after administration of the drug,

Patients using zolmitriptan 2.5 mg or 5 mg relief from headache was reported by 41%,

had a statistically significant 2-hour 47%, and 49% of patients who had received

response rate compared with that of eletriptan 5, 20, or 30 mg, respectively.

patients using sumatriptan 25 mg (P < Thirty-five percent of the patients had

.001). When compared with sumatriptan received placebo. In the second trial, the

50 mg, zolmitriptan 2.5 mg also pro- effect of oral eletriptan 20, 40, or 80 mg

duced a statistically significant 2-hour was compared with that of sumatriptan

response (P = .017). The rate of headache 100 mg or placebo in 270 patients.48

recurrence consistently associated with Relief from headache 2 hours after drug

zolmitriptan is about 30%.45 Adverse administration was reported by 44%, 67%,

events of zolmitriptan, including those 80%, and 57% of the patients who had

affecting the CNS, are similar to those of received eletriptan 20, 40, or 80 mg or

oral sumatriptan, although zolmitriptan sumatriptan 100 mg, respectively. In that

can cross the blood-brain barrier.42 The study, 25% of the patients had received

most common adverse events caused by placebo. The adverse events produced by

zolmitriptan 2.5 mg were nausea (in 8% to eletriptan were similar to those of suma-

11% of the patients), dizziness (8% to 9%), triptan. In another study, adverse events

paresthesia (6%), somnolence (5% to 7%), from doses of eletriptan 20 or 40 mg were

chest tightness (5%), and vomiting less than those produced by sumatriptan

(2%).46,47 In clinical practice, zolmitriptan 100 mg.49

2.5 mg is equivalent to sumatriptan 50 mg. Frovatriptan, another second-genera-

tion triptan, has a higher affinity for 5-

Rizatriptan. Rizatriptan, another sec- HT1B/1D receptors than does sumatriptan.

ond-generation triptan, has an improved In higher doses, frovatriptan is an agonist

S64 THE AMERICAN JOURNAL OF MANAGED CARE FEBRUARY 2002

Migraine: Diagnosis, Management, and New Treatment Options

of the 5-HT receptors that might cause pranolol, or timolol may be the most effec-

vasodilation on, for example, coronary tive initial therapy in patients who experi-

vessels.42 It is absorbed relatively slowly ence situational anxiety or “letdown”

and reaches its tmax 2 hours after adminis- migraine or in those with hypertension. A

tration; its pharmacokinetic properties are calcium channel blocker may be appropri-

similar to those of naratriptan. Thus, 2 ate for patients with peripheral vascular

hours after receiving frovatriptan 2.5 or 5 disease or hypertension. Doses of those

mg, 38% and 37% of the patients, respec- medications to prevent migraine often are

tively, reported headache relief. Four much lower than those used to treat a

hours after they received the drug, 68% comorbid disorder.

and 67% of patients, respectively, reported The amine ergot alkaloid methysergide

headache relief.50 Frovatriptan has a long is an effective prophylactic agent in

half-life (> 10 hours); this may result in a migraine therapy.53 Although the drug is

lower incidence of headache recurrence, devoid of α-adrenergic activity, long-term

which was reported by 7% to 25% of use may result in pleural, pericardial, or

patients.51 retroperitoneal fibrosis. However, those

problems can usually be avoided by close

Prophylaxis Against Migraine medical monitoring and by advising the

The objective of prophylactic treatment patient to take a 1-month “drug holiday”

of migraine is to reduce the frequency, every 6 months.

severity, and/or duration of attacks while Beta-blocking adrenergic drugs without

keeping adverse events to a minimum. intrinsic sympathomimetic activity are

No single prophylactic drug is superior the only class of beta-blockers effective for

when potential adverse events are also the prophylaxis of migraine.25 Their effect

considered.25 is observed within 4 weeks and seems to

Prophylactic therapy is indicated when increase with time. That group of drugs is

patients report that their acute migraines particularly useful for treating patients

are not adequately controlled or that whose attacks are triggered by stress.

they often use medication to treat an Propranolol and timolol have been studied

acute attack (Table 3). Prophylaxis should in numerous clinical trials and have also

be considered when nonpharmacologic been found to be effective.54 However, the

attempts have failed.25 Low doses of pro- adverse events caused by beta-blocking

phylactic medication should be used at drugs must be considered before they are

first and slowly titrated upward.25 Treat- prescribed. Propranolol is likely to pro-

ment can be administered for 3 months, duce adverse events on the CNS, which

reassessed before being continued for an may cause physicians to avoid prescribing

additional 6 months or more, and then it. Metoprolol, which has been shown to

gradually withdrawn after the frequency of decrease the number of migraine attacks

migraine attacks has been decreased. by 22% to 49%, is a useful alternative to

Prophylaxis is also indicated after the propranolol. A lack of adequate, controlled

diagnosis of comorbid conditions (such as clinical trials prevents conclusions with

depression) that can be treated with med- respect to the use of atenolol or nadolol as

ications effective in the treatment of alternatives to propranolol.25

migraine.52 Patients with sleep distur- Valproate, a gamma-aminobutyric acid

bances or depression may benefit most transaminase inhibitor and activator of

from treatment with a tricyclic antide- glutamic acid decarboxylase, was found to

pressant (eg, amitriptyline, doxepin, nor- be effective in double-blind, placebo-con-

triptyline, imipramine, protriptyline, trolled trials in reducing migraine fre-

desipramine). Those with agitation or quency in at least 48% to 65% of patients;

bipolar disorder or patients who have ter- the placebo-treated patients experienced

minated their drug therapy may benefit a reduction of 14% to 18%. Unlike other

from divalproate sodium. A beta-blocker prophylactic agents, valproate reduced

such as atenolol, nadolol, metoprolol, pro- the severity and duration of migraine

VOL. 8, NO. 3, SUP. THE AMERICAN JOURNAL OF MANAGED CARE S65

REPORTS

attacks.55,56 Adverse events of valproate the disability of the patient.62 It can also

include nausea, tremor, transient hair loss, interfere with the administration of oral

increase in appetite, and weight gain. medication. Exacerbation of nausea after

Hepatotoxicity was observed in patients the administration of oral medication can

treated with valproate who were younger indicate either the development of new

than 2 years of age. Women of childbearing nausea or a disease-related worsening of

age who consider treatment with valproate nausea, and alternative medications for

must be cautioned about the potential the treatment of migraine should be

increased risk of spina bifida in the newborn. explored.

The tricyclic antidepressant amitripty-

line may be effective because of its 5-HT2- Clinical Safety of Dihydroergota-

receptor-blocking and/or calcium-channel- mine and Ergotamine. The clinical safe-

blocking effect on cerebral blood vessels ty experience with DHE is based on 21

and its inhibitory effect on the dorsal raphe clinical studies; unfortunately, few of

nuclei.57 Amitriptyline, which reduces the those studies had clinical controls, many

frequency and duration of migraine attacks, were open label and unblinded, and most

is superior to placebo and more effective did not compare DHE with placebo.63

than propranolol in decreasing the severity Adverse events were often not document-

of migraine attacks.58,59 However, amitripty- ed systematically because the focus of the

line produces anticholinergic adverse studies was the efficacy of the medication.

events and causes increased appetite and No clinical studies evaluated the effects or

weight gain. Other tricyclic antidepressants efficacy of long-term intramuscular

with varying adverse-event profiles can administration of DHE, and only a few

also be tried. evaluated the results of repetitive intra-

The use of calcium antagonists in venous administration in hospital patients.

migraine prophylaxis has been disappoint- Although nausea was reported in a

ing.60 The dihydropyridine derivatives number of trials after treatment of migraine

nifedipine and nimodipine can actually with DHE, critical quantitative observa-

cause headache. Either verapamil or dil- tions demonstrated that the drug-induced

tiazem is usually used to prevent migraine symptom was difficult to differentiate

only after trials of the more effective beta- from nausea caused by migraine. Open

blockers or amitriptyline have failed. trials reported few adverse events of

According to 1 review, verapamil was 19% DHE. In summary, closed clinical trials

to 49% more effective than placebo in and open-label studies suggested that

decreasing the frequency of migraine serious adverse events occur very rarely

attacks.61 The most common adverse after a recommended dose of DHE has

events produced by verapamil are hyper- been taken, regardless of the route of

tension and constipation. Despite wide- administration.64

spread use for treatment of migraine, the The clinical safety experience with ET

results of clinical studies of diltiazem are indicates that it is much more likely than

“underwhelming.” DHE to produce nausea and vomiting,

uterine effects, and rebound headache.63

Tolerability and Safety of Most of the adverse events produced by

Migraine Treatment ET were associated with excessive dosage

Some adverse events (particularly nau- and/or long-term administration. The

sea) of drugs used to treat migraine can peripheral vasoconstrictor effect of ET is

mimic the signs or symptoms of the disor- considerably stronger than that of DHE.

der. It is therefore critical to distinguish When primary care physicians prescribe

drug-induced symptoms from those either DHE or ET, they must be aware that

caused by headache. Nausea, a common both are safe in the treatment of migraine

symptom of migraine, occurs in 78% of with or without aura when used in recom-

migraine sufferers. Because it is often mended doses and frequencies in adults

moderate to severe, nausea contributes to who have no contraindications to the

S66 THE AMERICAN JOURNAL OF MANAGED CARE FEBRUARY 2002

Migraine: Diagnosis, Management, and New Treatment Options

medications. When compared with ET, of risk (rather than the number of risk fac-

DHE causes less arterial constriction and tors) is the most important factor.67

(according to indirect comparisons) less “Therapeutic gain” refers to the propor-

frequent nausea and vomiting.63 tion of patients who respond to treatment

The Quality Standards Subcommittee with a drug tested minus the proportion of

of the American Academy of Neurology patients who respond to placebo. A review

appointed an advisory committee from of 30 clinical trials demonstrated that, 1

experts in its headache and facial pain hour after administration, subcutaneous

section to review the clinical literature on sumatriptan 6 mg administered for the

the appropriate use of DHE and ET in the acute treatment of migraine resulted in a

treatment of migraine.65 On the basis of greater therapeutic gain than did 100 mg

that thorough literature review, practice of orally administered sumatriptan or 20

guidelines were formulated to define the mg of intranasal sumatriptan 2 hours after

limits of ergot use. ET and DHE were administration.68 Although 6 mg of subcu-

found to be safe and effective for the treat- taneous sumatriptan is more effective

ment of migraine as long as recommended than the other doses and dosage forms

dosages were not exceeded and high-risk mentioned above, it causes more adverse

patients (those with uncontrolled hyper- events than does 100 mg of oral sumatrip-

tension, coronary or peripheral artery dis- tan, which appears to have the better ben-

ease, thyrotoxicosis, or sepsis) did not efit-to-risk ratio. However, most adverse

receive those drugs. The committee also events produced by the subcutaneous

recommended restricting the use of ET form of the drug were mild and short-last-

in some instances, because its overuse ing, and patients may find that the greater

has been associated with physical and efficacy and quicker onset of action of

psychological dependence. Drug-dependent subcutaneous sumatriptan outweigh the

patients often experience predictable higher incidence of adverse events.69

recurrent and/or rebound headaches, and Placebo-controlled studies have report-

subsequent medications are required to ed an incidence of chest-related adverse

alleviate the symptoms of withdrawal, events in up to 4% of patients treated with

such as nausea. None of those symptoms second-generation triptans, compared

has been associated with DHE. with an incidence ranging from less than

1% to 3% in placebo-treated patients.20 An

Clinical Safety of Triptans. First- and analysis of safety data indicates that

second-generation triptans represent a migraine patients seem to have a higher

breakthrough treatment for patients with level of risk for cardiovascular events

acute migraine. However, those drugs cause than does the general population; this

some degree of coronary vasoconstriction in implies that such events may be associat-

susceptible patients.66,67 At therapeutic doses, ed with the underlying condition rather

triptans are unlikely to cause myocardial than the treatment.70,71 However, those

ischemia in individuals with normal coronary agents should be used with caution in any

circulation.66 Although that effect is not patient with vascular risk factors.

clinically significant for patients who do Clinical judgment is key when the deci-

not have coronary artery disease, triptans sion to use triptans is made. If a patient

are contraindicated in those who have or has ischemic heart disease and uncon-

are at risk for that disorder.66 trolled high blood pressure, the primary

Adverse-event databases compiled for care physician or specialist should not pre-

the triptans show that the risk of life- scribe a triptan.70 A patient with a family

threatening cardiovascular events pro- history of heart disease and a high choles-

duced by those medications is probably terol level should first receive other med-

less than 1 in 1 million.67 The level of risk ications for migraine treatment before

associated with triptans is actually similar treatment with a triptan is initiated.

to (or perhaps even better than) that of Safety is indeed a viable concern in the

prescription NSAIDs.67 The patient’s level selection of appropriate migraine treat-

VOL. 8, NO. 3, SUP. THE AMERICAN JOURNAL OF MANAGED CARE S67

REPORTS

ment for a patient; however, it is important sumatriptan has an absolute bioavailabili-

to recognize that whether the patient can ty of only 14%.73-75

tolerate the drug is also an important (yet Of the approximately 45% of almotrip-

separate) issue. It is crucial to approach tan that is metabolized, about 27% is

those 2 distinct characteristics as separate metabolized by monoamine oxidase A and

factors in treatment choice. The safety of 12% by the cytochrome P-450 isozymes

a drug is of primary importance to ensure CYP 3A4 and 2D6. As a result, almotriptan

that a patient is least likely to experience has no substantial effect on the pharmaco-

any serious life-threatening outcomes kinetics of fluoxetine, which is metabo-

from treatment. After the safety of treat- lized by CYP 2D6, or other commonly used

ment has been established, the tolerabil- drugs such as verapamil or propranolol.76-78

ity of the treatment (ie, the point at Moclobemide, a reversible monoamine

which adverse events are sufficiently oxidase-A (MAO-A) inhibitor, modestly

reduced so that a patient is most likely to decreased the clearance of almotriptan.

continue treatment) becomes an added Thus the lowest available dose of almotrip-

consideration. tan should be used in patients treated with

MAO-A inhibitors.79 MAO-A inhibitors dra-

Almotriptan—Pharmacology, Efficacy, matically reduce the metabolism of suma-

and Tolerability triptan and zolmitriptan; thus concurrent

Almotriptan, the most recent 5-HT1B/1D administration of MAO-A inhibitors or the

agonist agent, demonstrates selective and use of sumatriptan or zolmitriptan within 2

equipotent nanomolar affinity for 5-HT1B weeks of the discontinuation of MAO-A

and 5-HT1D receptors; this mechanism of inhibitor therapy is contraindicated.

action is similar to that of sumatriptan.72 The efficacy of almotriptan was estab-

Functional affinity assays indicate that lished in 3 multicenter, randomized, dou-

almotriptan has a lower potency than ble-blind, placebo-controlled trials.80-82 In

does sumatriptan at the 5-HT1D receptor those studies, a significantly higher per-

and that its potency at the 5-HT1B recep- centage of patients who received either

tor is similar to that of rizatriptan and almotriptan 6.25 or 12.5 mg as opposed to

sumatriptan.72 Almotriptan exhibits 25 placebo experienced pain relief (mild or no

times the vasoconstrictor activity of pain) 2 hours after treatment. A higher

sumatriptan in the human meningeal percentage of patients in all 3 studies

artery.72 The oral formulation of almotrip- reported pain relief after treatment with

tan has the highest bioavailability (70%) the 12.5-mg dose as opposed to the 6.25-

among the second-generation triptans; its mg dose. In 2 of those studies, oral

half-life, however, is 3.0 to 3.7 hours. almotriptan (as opposed to placebo) pro-

Almotriptan is rapidly absorbed after an duced statistically significant 2-hour pain

oral dose and reaches a peak plasma con- relief rates (59% versus 34% and 65% ver-

centration of 66.2 ng/mL at 1.38 hours sus 33%, respectively), and 1 hour after

after administration.73 The plasma elimi- administration, significant pain relief was

nation half-life of almotriptan is 3.9 hours also experienced by patients given oral

in healthy volunteers. This may have clin- almotriptan as opposed to placebo (36%

ical relevance, especially when compared versus 19%, P = .007; and 34% versus 21%,

with sumatriptan’s half-life of about 2 P = .001).80,81 In Table 4, the 2-hour pain-

hours (regardless of the route of adminis- relief rates after oral almotriptan adminis-

tration).71 Sumatriptan’s shorter half-life tration during an initial migraine are

may explain its association with recurring summarized.

headache, which has affected 21% to When compared with the results of

57% of patients in trials of both oral and placebo, oral almotriptan 12.5 mg provid-

subcutaneous formulations of the drug.71 ed consistent pain relief over the course of

Oral almotriptan has a bioavailability of 3 consecutive migraine attacks in another

70%. In contrast, zolmitriptan has an double-blind, placebo-controlled study.82

absolute bioavailability of 49%, and Although oral almotriptan 12.5 mg also

S68 THE AMERICAN JOURNAL OF MANAGED CARE FEBRUARY 2002

Migraine: Diagnosis, Management, and New Treatment Options

produced pain relief rates similar to those mouth, nausea, paresthesia, and somno-

of oral sumatriptan 100 mg in a random- lence. No adverse events in the groups

ized, double-blind, placebo-controlled who received the 6.25 or 12.5-mg dose

clinical study, almotriptan 12.5 mg was occurred at a rate of 1 or more percentage

associated with a significantly lower inci- points higher than that of the placebo

dence of treatment-related adverse events group. Dry mouth, paresthesia, and som-

(P < .05).81 In addition, almotriptan 12.5 nolence are adverse events produced by

mg and sumatriptan 50 mg were com- triptans, and nausea and headache are

pared in a randomized, double-blind often observed in migraine patients. Other

trial.83 Pain relief occurred 2 hours after adverse events associated with triptan use,

administration in 58% of patients treated such as asthenia, chest pain, localized

with almotriptan and in 57% of those pain, palpitation, vasodilation, and dizzi-

treated with sumatriptan. However, signif- ness, were not associated with almotriptan

icantly fewer patients in the almotriptan administered at recommended doses. For

group (P < .05) experienced treatment- both doses, the only adverse event that

related adverse events (9.1% versus 15.5%) occurred in 2% or more of the patients was

and chest symptoms in particular (0.3% nausea (2% in those who received

versus 2.2%). almotriptan 12.5 mg).

The tolerability of almotriptan was in The adverse-event profile for sumatrip-

most instances similar to that of placebo. tan in the studies cited above is consis-

In controlled clinical trials, nausea in 2% tent with data from other studies of that

of the patients was the only adverse event drug.85,86 Although the types of adverse

recorded in 2% or more of those treated events in the almotriptan-treated groups

with almotriptan.84 Headache was fre- were similar to those observed in the

quently noted when oral almotriptan 6.25 groups treated with sumatriptan, almotrip-

to 25 mg was administered. Infrequent tan 6.25 and 12.5 mg produced lower rates

adverse events, all of which were mild and of chest pain and nausea than did suma-

transient in nature, included abdominal triptan 50 mg. Vomiting occurred at a

cramps, vasodilation, palpitations, tachy- higher rate in the placebo-treated group

cardia, dry mouth, diarrhea, vomiting, and (1.6%) than in any of the other main treat-

dyspepsia. In those trials, the adverse ment groups (all > 1%). Adverse-event

events were similar to those attributed to rates (particularly for chest pain, nausea,

placebo.84 Patients who experienced migraine-

associated photophobia, phonophobia, nau-

sea, or vomiting at baseline had a decreased

incidence of those symptoms after the Table 4. Clinical Studies of Oral Almotriptan Demonstrating

administration of almotriptan as opposed to Pain Relief* in the Treatment of Acute Migraine

placebo.

In controlled clinical studies, a total of Placebo Almotriptan Almotriptan

2809 patients were treated with almotrip- Study Author(s) (%) 6.25 mg (%) 12.5 mg (%)

tan (527 with 6.25 mg, 1313 with 12.5 mg,

Dahlöf et al80 33.8 56.3† 58.5‡

and 387 with 25 mg) or sumatriptan (582

(n = 80) (n = 166) (n = 164)

with 50 mg).84 The overall adverse event

rates in those studies were 12.4% (those Dowson81 42.4 — 56.8§

who received placebo), 14% (almotriptan (n = 99) (n = 183)

6.25 mg), 15.4% (almotriptan 12.5 mg), Pascual et al82 33.0 55.6‡ 64.9‡

20.4% (almotriptan 25 mg), and 19.4% (n =176) (n = 374) (n = 370)

(sumatriptan 50 mg). The most common

adverse events associated with almotrip-

*Pain relief was noted at 2 hours after administration of the drug for initial

tan use (at a rate of at least 1%—a rate

headache.

greater than that of placebo) in the con- †P = .002 in comparison with placebo.

trolled studies at the recommended doses ‡P ≤ .001 in comparison with placebo.

of 6.25 or 12.5 mg were headache, dry §P = .025 in comparison with placebo.

VOL. 8, NO. 3, SUP. THE AMERICAN JOURNAL OF MANAGED CARE S69

REPORTS

dizziness, or somnolence) in the groups than do the other marketed triptans.

treated with higher doses of almotriptan However, when compared with other

(25, 100, or 150 mg) were usually higher triptans, its delayed onset of action is a

than those in the patients who received disadvantage.

lower doses of the drug. Almotriptan is characterized by a rapid

onset of action, effectiveness over 24

Conclusions hours with a low recurrence rate of

Migraine is an underdiagnosed and migraine, and few adverse events. It is not

undertreated disorder that is experienced contraindicated in patients with severe

most often during peak productive years renal or hepatic impairment. However,

(25 to 55 years of age). The recently devel- because of the potential of 5-HT1B/1D recep-

oped IHS criteria for headache classifica- tor agonists to cause coronary vasospasm,

tion have provided a uniform case almotriptan should not be given to

definition that has facilitated epidemiolog- patients with documented ischemic or

ic research on headaches. The disability vasospastic coronary artery disease,

caused by headaches has a great effect on ischemic heart disease, or uncontrolled

individuals and on society, and health hypertension. Low tolerability is not syn-

interventions are critical to the manage- onymous with improved safety.

ment of those disorders. Physicians must Almotriptan is well tolerated. Controlled

be aware of the diagnostic criteria for clinical trials of that drug indicate that at

headaches and must be able to prescribe therapeutic doses, it causes a lower inci-

effective therapy in accordance with the dence of chest pain than does sumatrip-

patient’s possible intolerance of various tan, that it produces no dose-related

medications. clinically relevant effects on electrocardio-

Primary care physicians are concerned graphic results, and that (when compared

with 2 critical aspects in treating migraine with placebo) it produces a low incidence

patients. The first is the efficacy of an of somnolence and other CNS effects and

agent in rapidly relieving headache and has a similar tolerability profile. In clinical

preventing recurrence. The second is the trials in which 20,000 migraine attacks

knowledge that the agent does not produce occurred in nearly 4000 patients, the

harmful adverse events. Therefore, at this dropout rate of almotriptan-treated indi-

stage in the development of triptans used viduals was very low, and those patients

to treat acute migraine, the tolerability and experienced no unanticipated adverse

safety of the drug are very important con- events. Almotriptan should expand the

siderations, especially when several agents armamentarium of antimigraine drugs

are now available to relieve headache. In available to physicians and patients.

most patients, triptans alleviate migraine

pain in 2 hours, regardless of the time of . . . REFERENCES . . .

onset. However, the adverse events pro-

duced by triptans must be considered by 1. Bartelson JD. Treatment of migraine headaches.

the primary care physician before he or Mayo Clin Proc 1999;74:702-708.

she prescribes a particular drug. 2. Lipton RB, Stewart WF, von Korff M. Migraine

impact and functional disability. Cephalalgia

Although similar adverse events are 1995;15(suppl 15):4-9.

produced by triptans as a class, a benefit- 3. Hu XH, Markson LE, Lipton RB, Stewart WF,

to-risk ratio must always be considered for Berger ML. Burden of migraine in the United States:

each drug in that class. This implies that a Disability and economic costs. Arch Intern Med

1999;159:813-818.

particular oral dose of a triptan can pro- 4. Lipton RB, Stewart WF, Simon D. Medical consul-

duce an excellent therapeutic effect as tation for migraine: Results from the American

well as minimal adverse events. As newer, Migraine Study. Headache 1998;38:87-96.

more effective oral triptans are developed, 5. Gallagher RM, Kunkel R. Migraine patient con-

cerns affecting compliance: Results from the NHF sur-

it is hoped that an improved benefit-to- vey. Headache. 2002. In press.

risk ratio will also be achieved. Naratriptan 6. Goadsby PJ. Current concepts of the pathophysiol-

appears to produce fewer adverse events ogy of migraine. Neurol Clin 1997;15:27-42.

S70 THE AMERICAN JOURNAL OF MANAGED CARE FEBRUARY 2002

Migraine: Diagnosis, Management, and New Treatment Options

7. Stewart WF, Shechter A, Rasmussen BK. Migraine treatment of common migraine attacks: A double-

prevalence. A review of population-based studies. blind study versus placebo. Cephalalgia 1991;11:59-

Neurology 1994;44(suppl 4):S17-S23. 63.

8. Prevalence of chronic migraine headaches—United 27. Silberstein DS, Lipton RB, Dalessio DJ, eds.

States, 1980-1989. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep Wolff's Headache and Other Head Pain. 7th ed. New

1991;40:331-338. York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2001.

9. Sillanpaa M. Headache in children. In: Olesen J, 28. Carleton SC, Shesser RF, Pietzrak MP, et al.

ed. Headache Classification and Epidemiology. New Double-blind, multicenter trial to compare the

York, NY: Raven Press; 1994:273-281. efficacy of intramuscular dihydroergotamine plus

10. Rasmussen BK. Epidemiology of headache. hydroxyzine versus intramuscular meperidine plus

Cephalalgia 1995;15:45-68. hydroxyzine for the emergency department treatment

11. Lipton RB. Disability assessment as a basis for of acute migraine headache. Ann Emerg Med

stratified care. Cephalalgia 1998;18(suppl 22):40-46. 1998;32:129-138.

12. Marcus DA. Serotonin and its role in headache 29. Ellis GL, Delaney J, DeHart DA, Owens A. The

pathogenesis and treatment. Clin J Pain 1993;9:159- efficacy of metoclopramide in the treatment of

167. migraine headache. Ann Emerg Med 1993;22:191-

195.

13. Hargreaves RJ, Shepheard SL. Pathophysiology

of migraine—new insights. Can J Neurol Sci 1999; 30. Ferrari MD. Migraine. Lancet 1998;351:1043-

26(suppl 3):S12-S19. 1051.

14. Headache Classification Committee of the 31. Silberstein SD. The pharmacology of ergotamine

International Headache Society. Classification and and dihydroergotamine. Headache 1997;37(suppl

diagnostic criteria for headache disorders, cranial 1):S15-S25.

neuralgias and facial pain. Cephalalgia 1988;8(suppl 32. Goadsby PJ, Gundlach AL. Localization of 3H-

7):1-96. dihydroxyergotamine-binding sites in the cat central

15. Olesen J, Lipton RB. Migraine classification and nervous system: Relevance to migraine. Ann Neurol

diagnosis. International Headache Society criteria. 1991;29:91-94.

Neurology 1994;44(suppl 4):S6-S10. 33. Saadah HA. Abortive headache therapy in the

16. Capobianco DJ, Cheshire WP, Campbell JK. An office with intravenous dihydroergotamine plus

overview of the diagnosis and pharmacologic treatment prochlorperazine. Headache 1992;32:143-146.

of migraine. Mayo Clin Proc 1996;71:1055-1066. 34. Dihydroergotamine Nasal Spray Multicenter

17. Pryse-Phillips WE, Dodick DW, Edmeads JG. Investigators. Efficacy, safety, and tolerability of dihy-

Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of droergotamine nasal spray as monotherapy in the

migraine in clinical practice. CMAJ 1997;156:1273- treatment of acute migraine. Headache 1995;35:177-

1287. 184.

18. Diamond S. Diagnosing and Managing Headache. 35. Gallagher RM, the Dihydroergotamine Working

2nd ed. Caddo, OK: Professional Communications, Group. Acute treatment of migraine with dihydroer-

Inc; 1998. gotamine nasal spray. Arch Neurol 1996;53:1285-

19. Cady RK, Sheftell F, Lipton RB, et al. Effect of 1291.

early intervention with sumatriptan on migraine pain: 36. Raskin NH. Repetitive intravenous dihydroergota-

Retrospective analyses of data from three clinical tri- mine as therapy for intractable migraine. Neurology

als. Clin Ther 2000;22:1035-1048. 1986;36:995-997.

20. Deleu D, Hanssens Y. Current and emerging sec- 37. Goadsby PJ. Serotonin 5-HT1B/1D receptor ago-

ond-generation triptans in acute migraine therapy: A nists in migraine. Comparative pharmacology and its

comparative review. J Clin Pharmacol 2000;40:687- therapeutic implications. CNS Drugs 1998;10:271-

700. 286.

21. Silberstein SD. Practice parameter: Evidence- 38. Peroutka SJ. 5-Hydroxytryptamine receptor sub-

based guidelines for migraine headache (an evidence- types. Pharmacol Toxicol 1990;67:373-383.

based review): Report of the Quality Standards 39. Weiss J. Assessment and management of the

Subcommittee of the American Academy of client with headaches. Nurse Pract 1993;18:44-54.

Neurology. Neurology 2000;55:754-762. 40. Diener HC, Limmroth V. Acute management of

22. Lobo BL, Cooke SC, Landy SH. Symptomatic migraine: Triptans and beyond. Curr Opin Neurol

pharmacotherapy of migraine. Clin Ther 1999;12:261-267.

1999;21:1118-1130. 41. Diener HC, Kaube H, Limmroth V. Antimigraine

23. Buzzi MG, Sakas DE, Moskowitz MA. drugs. J Neurol 1999;246:515-519.

Indomethacin and acetylsalicylic acid block neuro- 42. Limmroth V, Diener HC. New anti-migraine

genic plasma protein extravasation in rat dura matter. drugs: Present and beyond the millennium. Int J Clin

Eur J Pharmacol 1989;165:251-258. Pract 1998;52:566-570.

24. Peatfield RC, Petty RG, Rose FC. Double blind 43. Klassen A, Elkind A, Asgharnejad M, Webster C,

comparisons of mefenamic acid and acetaminophen Laurenza A. Naratriptan is effective and well tolerated

(paracetamol) in migraine. Cephalalgia 1983;3: in the acute treatment of migraine. Results of a dou-

129-134. ble-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group study.

25. Deleu D, Hanssens Y, Worthing EA. Symptomatic Naratriptan S2WA3001 Study Group. Headache

and prophylactic treatment of migraine: A critical 1997;37:640-645.

reappraisal. Clin Neuropharmacol 1998;21:267- 44. Gallagher RM, Dennish G, Spierings EL, Chitra

279. R. A comparative trial of zolmitriptan and sumatriptan

26. Massiou H, Serrurier D, Lasserre O, Bousser for the acute oral treatment of migraine. Headache

MG. Effectiveness of oral diclofenac in the acute 2000;40:119-128.

VOL. 8, NO. 3, SUP. THE AMERICAN JOURNAL OF MANAGED CARE S71

REPORTS

45. Ferrari MD. 311C90: Increasing the options for 63. Lipton RB. Ergotamine tartrate and dihydroergota-

therapy with effective acute antimigraine 5HT1B/1D mine mesylate: Safety profiles. Headache 1997;37

receptor agonists. Neurology 1997;48(suppl 3):S21-S24. (suppl 1):S33-S41.

46. Rapoport AM, Ramadan NM, Adelman JU, et al. 64. Silberstein SD. Migraine symptoms: Results of a

Optimizing the dose of zolmitriptan (Zomig, 311C90) survey of self-reported migraineurs. Headache

for the acute treatment of migraine. A multicenter, 1995;35:387-396.

double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose range-finding 65. Young WB. Appropriate use of ergotamine tartrate

study. The 017 Clinical Trial Study Group. Neurology and dihydroergotamine in the treatment of migraine:

1997;49:1210-1218. Current perspectives. Headache 1997;37(suppl 1):

47. Solomon GD, Cady RK, Klapper JA, Earl NL, S42-S45.

Saper JR, Ramadan NM. Clinical efficacy and tolera- 66. MaassenVanDenBrink A, Reekers M, Bax WA,

bility of 2.5 mg zolmitriptan for the acute treatment Ferrari MD, Saxena PR. Coronary side-effect potential

of migraine. The 042 Clinical Trial Study Group. of current and prospective antimigraine drugs.

Neurology 1997;49:1219-1225. Circulation 1998;98:25-30.

48. Farkkhila M, Diener HC, Dahlöf C, Steiner TJ, 67. MacIntyre PD, Bhargava B, Hogg KJ, Gemmill

on behalf of the Eletriptan Steering Committee. A JD, Hillis WS. Effect of subcutaneous sumatriptan, a

dose-finding study of eletriptan (5-30 mg) for the selective 5HT1 agonist, on the systemic, pulmonary,

acute treatment of migraine [abstract]. Cephalalgia and coronary circulation. Circulation 1993;87:401-

1996;16:387. 405.

49. Jackson NC, for the Eletriptan Steering 68. Tfelt-Hansen P. Efficacy and adverse events of

Committee. A comparison of oral eletriptan (20-80 subcutaneous, oral, and intranasal sumatriptan used

mg) and oral sumatriptan (100 mg) in the acute treat- for migraine treatment: A systematic review based on

ment of migraine [abstract]. Cephalalgia 1996;16:368. number needed to treat. Cephalalgia 1998;18:532-538.

50. Goldstein J, Keywood C. A low-dose range find- 69. Simmons VE, Blakebourough P. The safety profile

ing study of frovatriptan, a potent selective 5-HT1B/1D of sumatriptan. Rev Contemp Pharmacother

agonist for the treatment of migraine. Funct Neurol 1994;5:319-328.

1998;13:178. 70. O'Quinn S, Davis RL, Gutterman DL, Part GD,

51. Migraine, frovatriptan. Available at http://www. Fox AW. Prospective large-scale study of the tolera-

vernalis.com/r_d_portfolio/content1/content.htm bility of subcutaneous sumatriptan injection for acute

Accessed April 30, 2001. treatment of migraine. Cephalalgia 1999;19:223-231.

52. Tomkins GE, Jackson JE, O’Malley PG, Balden E, 71. Perry CM, Markham A. Sumatriptan. An updated

Santero JE. Treatment of chronic headache with anti- review of its use in migraine. Drugs 1998;55:889-922.

depressants: A meta-analysis. Am J Med 2001;111: 72. Bou J, Domenech T, Puig J, et al. Pharmacological

54-63. characterization of almotriptan: An indolic 5-HT

53. Steardo L, Marano E, Barone P, Denman DW, receptor agonist for the treatment of migraine. Eur J

Monteleone P, Cardone G. Prophylaxis of migraine Pharmacol 2000;410:33-41.

attacks with a calcium-channel blocker: Flunarizine 73. Cabarrocas X, Salva M. Pharmacokinetic and

versus methysergide. J Clin Pharmacol 1986;26:524- metabolic data on almotriptan, a new antimigraine

528. drug. Cephalalgia 1997;17:421.

54. Massiou H, Bousser MG. Beta-blocqants et 74. Fowler PA, Lacey LF, Thomas M, Keene ON,

migraine. Pathol Biol (Paris). 1992;40:373-380. Tanner RJ, Baber NS. The clinical pharmacology,

55. Jensen R, Brink T, Olesen J. Sodium valproate pharmacokinetics and metabolism of sumatriptan.

has a prophylactic effect in migraine without aura: A Eur Neurol 1991;31:291-294.

triple-blind, placebo-controlled crossover study. 75. Seaber E, On N, Dixon RM, et al. The absolute

Neurology 1994;44:647-651. bioavailability and metabolic disposition of the novel

56. Mathew NT, Saper JR, Silberstein SD, et al. antimigraine compound zolmitriptan (311C90). Br J

Migraine prophylaxis with divalproex. Arch Neurol Clin Pharmacol 1997;43:579-587.

1995;52:281-286. 76. Fleishaker JC, Ryan KK, Carel BJ, Azie NE.

57. Peroutka SJ. 5-Hydroxytryptamine receptor sub- Evaluation of the potential pharmacokinetic interac-

types and the pharmacology of migraine. Neurology tion between almotriptan and fluoxetine in healthy

1993;43:S34-S38. volunteers. J Clin Pharmacol 2001;41:217-223.

58. Couch JR, Hassanein RS. Amitriptyline in 77. Fleishaker JC, Sisson TA, Carel BJ, Azie NE. Lack

migraine prophylaxis. Arch Neurol 1979;36:695-699. of pharmacokinetic interaction between the antimi-

59. Ziegler DK, Hurwitz A, Preskorn S, Hassanein graine compound, almotriptan, and propranolol in

RS, Siem J. Propranolol and amitriptyline in prophy- healthy volunteers. Cephalalgia 2001;21:61-65.

laxis of migraine. Pharmacokinetic and therapeutic 78. Fleishaker JC, Sisson TA, Carel BJ, Azie NE.

effects. Arch Neurol 1993;50:825-830. Pharmacokinetic interaction between verapamil and

60. Andersson KE, Vinge E. Beta-adrenoceptor block- almotriptan in healthy volunteers. Clin Pharmacol

ers and calcium antagonists in the prophylaxis and Ther 2000;67:498-503.

treatment of migraine. Drugs 1990;39:355-373. 79. Fleishaker JC, Ryan KK, Carel BJ, Azie NE. Effect

61. Ramadan NM, Schultz LL, Gilkey SJ. Migraine of MAO-A inhibition on the pharmacokinetics of a

prophylactic drugs: Proof of efficacy, utilization and novel antimigraine agent, almotriptan, in humans. Paper

cost. Cephalalgia 1997;17:73-80. presented at: Annual Meeting of the American Academy

62. Lipton RB, Solomon S, Newman LC, Sheftell FD. of Neurology; April 17-24, 1999; Toronto, Ontario.

Gastrointestinal symptoms in migraine: Results from 80. Dahlöf C, Tfelt-Hansen P, Massiou H, Fazekas A,

the AASH-Gallup survey [abstract]. Headache for the Almotriptan Study Group. Dose finding,

1995;45:563. placebo-controlled study of oral almotriptan in the

S72 THE AMERICAN JOURNAL OF MANAGED CARE FEBRUARY 2002

Migraine: Diagnosis, Management, and New Treatment Options

acute treatment of migraine. Neurology 2001;57: group, optimum-dose comparison. Arch Neurol

1811-1817. 2001;58:944-950.

81. Dowson A. Almotriptan is an effective and well- 84. Dodick DW. Oral almotriptan in the treatment of

tolerated treatment for migraine pain: Results of a ran- migraine: Safety and tolerability. Headache 2001;41:

domised, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical 449-455.

trial. Cephalalgia 2002. In press. 85. Pfaffenrath V, Cunin G, Sjonell G, Prendergast S.

82. Pascual J, Falk RM, Piessens F, et al. Consistent Efficacy and safety of sumatriptan tablets (25 mg, 50

efficacy and tolerability of almotriptan in the acute mg, and 100 mg) in the acute treatment of migraine:

treatment of multiple migraine attacks: Results of a Defining the optimum doses of oral sumatriptan.

large, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled Headache 1998;38:184-190.

study. Cephalalgia 2000;20:588-596. 86. Multinational Oral Sumatriptan and Cafergot

83. Spierings EL, Gomez-Mancilla B, Grosz DE, Comparative Study Group. A randomized, double-

Rowland CR, Whaley FS, Jirgens KJ. Oral almotriptan blind comparison of sumatriptan and cafergot in the

vs. oral sumatriptan in the abortive treatment of acute treatment of migraine. Eur Neurol 1991;

migraine: A double-blind, randomized, parallel- 31:314-322.

VOL. 8, NO. 3, SUP. THE AMERICAN JOURNAL OF MANAGED CARE S73

You might also like

- Gender and MigraineFrom EverandGender and MigraineAntoinette Maassen van den BrinkNo ratings yet

- Migraine: The Definitive Guide to Understanding and Managing Severe HeadachesFrom EverandMigraine: The Definitive Guide to Understanding and Managing Severe HeadachesNo ratings yet

- migraineDocument6 pagesmigraineNatália CândidoNo ratings yet

- Contents 2019 Neurologic-ClinicsDocument4 pagesContents 2019 Neurologic-ClinicsAghie vlogNo ratings yet

- Maju Jurnal MigrainDocument7 pagesMaju Jurnal MigrainRosyid PrasetyoNo ratings yet

- Diagnosis and Acute Management of MigraineDocument6 pagesDiagnosis and Acute Management of MigraineJavierNo ratings yet

- Migraine and The Scope of HomeopathyDocument6 pagesMigraine and The Scope of HomeopathyDiego RodriguezNo ratings yet

- Diagnosis and Management of Headache A ReviewDocument12 pagesDiagnosis and Management of Headache A ReviewAlicia GarcíaNo ratings yet

- CCJM Relieving Migraine PainDocument12 pagesCCJM Relieving Migraine PainBrian HarrisNo ratings yet

- New England Journal of Medicine Volume 383 Issue 19 2020 (Doi 10.1056 - NEJMra1915327) Ropper, Allan H. Ashina, Messoud - MigraineDocument11 pagesNew England Journal of Medicine Volume 383 Issue 19 2020 (Doi 10.1056 - NEJMra1915327) Ropper, Allan H. Ashina, Messoud - MigraineMarija Sekretarjova100% (1)

- Emerging Drugs For Migraine Treatment: An UpdateDocument19 pagesEmerging Drugs For Migraine Treatment: An UpdateShivam BhadauriaNo ratings yet

- Charles 2017Document9 pagesCharles 2017Aldebaran LadoNo ratings yet

- Inbound 1186825581313765270Document16 pagesInbound 1186825581313765270NylNo ratings yet

- Headache - Seminars in NeurologyDocument7 pagesHeadache - Seminars in NeurologyandreaNo ratings yet

- 2017 Article 592Document17 pages2017 Article 592Shivam BhadauriaNo ratings yet

- Nej MR A 1915327Document11 pagesNej MR A 1915327Noel Saúl Argüello SánchezNo ratings yet

- Aian 22 286Document5 pagesAian 22 286gloriaNo ratings yet

- Management of Migraine Headache: An Overview of Current PracticeDocument7 pagesManagement of Migraine Headache: An Overview of Current Practicelili yatiNo ratings yet

- Migraine: Diagnosis and Management: PathophysiologyDocument6 pagesMigraine: Diagnosis and Management: Pathophysiologykillingeyes177No ratings yet

- Nejmra 1915327Document11 pagesNejmra 1915327lakshminivas PingaliNo ratings yet

- 9.1 An Approach To Identifying Headache Patients That Require Neuroimaging (Curr, Inst and Pedagogy 2019)Document6 pages9.1 An Approach To Identifying Headache Patients That Require Neuroimaging (Curr, Inst and Pedagogy 2019)Katherine RodríguezNo ratings yet

- Diagnosing and Managing Migraine Headache PDFDocument7 pagesDiagnosing and Managing Migraine Headache PDFirene claraNo ratings yet

- Managing and Preventing Migraine in The Emergency Department A ReviewDocument20 pagesManaging and Preventing Migraine in The Emergency Department A ReviewdedeadamNo ratings yet

- UKDI PREPARATION I: Neurogenic Pain Syndromes and Primary HeadachesDocument65 pagesUKDI PREPARATION I: Neurogenic Pain Syndromes and Primary HeadachesFelicia SutarliNo ratings yet

- Practice: A 32-Year-Old Woman With HeadacheDocument2 pagesPractice: A 32-Year-Old Woman With HeadacheFeliNo ratings yet

- Chronic Migraine Pathophysiology and Treatment: A Review of Current PerspectivesDocument15 pagesChronic Migraine Pathophysiology and Treatment: A Review of Current PerspectivesJorge ZegarraNo ratings yet

- Migraine in Systemic Autoimmune Diseases Cavestro-Ferrero 2018Document11 pagesMigraine in Systemic Autoimmune Diseases Cavestro-Ferrero 2018Adrianah ValenchyNo ratings yet

- Shahdevinandar, JPHV 2241 PUBLISHDocument6 pagesShahdevinandar, JPHV 2241 PUBLISHGinanjar Putri SariNo ratings yet

- Migraine DiagnosisDocument7 pagesMigraine DiagnosisMariaAmeliaGoldieNo ratings yet

- Role of Triptans in The Management of Acute Migraine: A ReviewDocument7 pagesRole of Triptans in The Management of Acute Migraine: A ReviewAndreas NatanNo ratings yet

- 47 Migraine and Its Psychiatric ComorbiditiesDocument9 pages47 Migraine and Its Psychiatric ComorbiditiesElizabeth Mautino CaceresNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Migrain Asam ValproatDocument5 pagesJurnal Migrain Asam ValproatcynthiaramaNo ratings yet

- Headache NewDocument17 pagesHeadache NewHaris PeaceNo ratings yet

- Headaches 5Document26 pagesHeadaches 5Elvis obajeNo ratings yet

- Marcus 2001Document8 pagesMarcus 2001Juliana Valentina CedeñoNo ratings yet

- Piis0002934317309324 PDFDocument8 pagesPiis0002934317309324 PDFRenato KaindoyNo ratings yet

- Headache - Approach To The Adult PatientDocument28 pagesHeadache - Approach To The Adult PatientasasakopNo ratings yet

- Ferrari Et Al-2022-Nature Reviews Disease PrimersDocument20 pagesFerrari Et Al-2022-Nature Reviews Disease PrimersMarco Antonio KoffNo ratings yet

- Dor de Cabeça IIDocument11 pagesDor de Cabeça IIElisaLadagaNo ratings yet

- BASH Guidelines Update 2 - v5 1 Indd PDFDocument53 pagesBASH Guidelines Update 2 - v5 1 Indd PDFnephylymNo ratings yet

- Manejo de La Migraña en Adultos. Tratamiento FarmacologicoDocument19 pagesManejo de La Migraña en Adultos. Tratamiento FarmacologicoGabriel Josué Alaña UrdanetaNo ratings yet

- Jurnal 6Document4 pagesJurnal 6Anonymous DyvACjGQayNo ratings yet

- Migraine Pathophysiology Advances Implications for Clinical ManagementDocument9 pagesMigraine Pathophysiology Advances Implications for Clinical ManagementAzam alausyNo ratings yet

- Headache: Migraine and Tension-Type HeadacheDocument12 pagesHeadache: Migraine and Tension-Type HeadacheLoren SangalangNo ratings yet

- Migrraine Review 2017 NEJMDocument9 pagesMigrraine Review 2017 NEJManscstNo ratings yet

- Kung Doris Chronic MigraineDocument19 pagesKung Doris Chronic MigraineAnonymous tG35SYROzENo ratings yet

- ANSWERS Vol 24.4 - Headache.2018 PDFDocument40 pagesANSWERS Vol 24.4 - Headache.2018 PDFmonica ortizNo ratings yet

- Journal 2Document12 pagesJournal 2FieraNo ratings yet

- Headache: Thomas Kwiatkowski and Kumar AlagappanDocument11 pagesHeadache: Thomas Kwiatkowski and Kumar AlagappanS100% (1)

- Bahan Journal Reading MigraineDocument9 pagesBahan Journal Reading Migraineleviana aurelliaNo ratings yet

- Headache Classification and TypesDocument42 pagesHeadache Classification and TypesRaghoba GaonkarNo ratings yet

- Migraine Is A CommonDocument11 pagesMigraine Is A CommonajenkajenkNo ratings yet

- Menstrual Migrain Razutis 2015Document4 pagesMenstrual Migrain Razutis 2015Fifi RohmatinNo ratings yet

- GepantsDocument14 pagesGepantsmatheus galvãoNo ratings yet

- Migraine HeadachesDocument15 pagesMigraine Headachesdheeksha puvvadaNo ratings yet