Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Dokumen - Tips - Understanding Robust and Exploratory Data Analysisby David C Hoaglin Frederick

Uploaded by

Pedro Pablo Ruiz HuertasOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Dokumen - Tips - Understanding Robust and Exploratory Data Analysisby David C Hoaglin Frederick

Uploaded by

Pedro Pablo Ruiz HuertasCopyright:

Available Formats

Understanding Robust and Exploratory Data Analysis. by David C.

Hoaglin; Frederick

Mosteller; John W. Tukey

Review by: D. L. McLeish

Journal of the American Statistical Association, Vol. 80, No. 389 (Mar., 1985), pp. 233-234

Published by: American Statistical Association

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2288080 .

Accessed: 15/06/2014 01:34

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

American Statistical Association is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Journal

of the American Statistical Association.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 188.72.126.88 on Sun, 15 Jun 2014 01:34:45 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Book Reviews 233

The effect on final evidence of the choice of 7r, is thus as serious as the choice Exploratorydata analysis (EDA), according to the introduction, studies

of Pr(H), and it is likely that Pr(H) can be more easily specified than 7t,. The singly and in combinationthe "fourR's": resistance,residuals, reexpression,

attemptedseparationof final evidence into "priorevidence" and "experimental and revelation. Resistance provides insensitivityof estimatorsto a change in

evidence" thus seems to be a failure. (One can, in this example, establishthe a small portion of the data. Residuals are studied to ascertain whether the

bound "weight of evidence" 2 - (n/2)2, which is independentof X,; and dominantand unusualfeaturesof the data have been adequatelyisolated and

in some circumstancesthis may be a useful bound for verifying H.) explained. Reexpression(transformation)of the data is used to promotesym-

This criticismof weight of evidence is actually somewhat unfair, because metry, homogeneity, linearity,and so forth. Revelationthroughvisual displays

Good never claimed that it is possible to break up total evidence into parts meets a clear need of dataanalyststo see behavior.Chapters1-3 are primarily

involving the prior and data separately. His only claims are that (a) in con- concerned with revelation, 4 and 8 with reexpression, 7 with residuals, and

templatingwhat the datahas to say, it is enlighteningto separateoff the initial 5, 6, and 9-12 with resistance.

log odds for H and (b) if one does want to talk abouta concept such as weight Chapter 1 describes the stem and leaf display, a well-establisheddisplay

of evidence (as many statisticiansand philosophersdesire to do), then the only that combines the features of a histogram with the need to retain more sig-

reasonablechoice is that consideredby Good (see Good 1984 for a discussion nificant digits. Rules for determiningintervalwidth, based on work of Scott

of this last point). I am certainly sympatheticwith both of these arguments and of Freedmanand Diaconis, are described.

and see no inherent harm in having available concepts such as weight of Chapter2 introducesletter values. If X(,), X(2),. X(n)are the ordersta-

evidence (and surpriseindexes, quasi utilities, etc.), except that they partially tistics from a sample of size n, the letter values are defined recursively;the

draw attentionaway from posteriorprobabilities,which may not be desirable ith lettervalues areX(J,)and X(n+ I -J),, where Ji_+ = ([J,] + 1)/2. HereJ, =

for nonexperts.This is essentially a Type II rationalityargument;that is, any (n + 1)/2 and an order statistic X(k+ 1/2) indicates the average of

additionalstatisticalbaggage we carry aroundmust be justifiable in terms of X(k) and X(k+ ,,. These are obviously closely related, but not identical, to the

the time it takes to learn how to use it properly.As with pudding, of course, 2-i and 1 - 2-' sample quantiles, and the values of these for i ' 2 or i '

the ultimateproof is in the tasting, and I must admitto not having tried these 3, together with the extremes, are displayed in five- or seven-numbersum-

concepts enough to know whetherone can indeed acquirea taste for them. (I maries of the data.

should certainly make the attempt, since I found Good's main course so Chapter3 describes boxplots, used to provide a visual impression of the

delicious.) median, fourthsXJ2)and X(n+ I -J2), andextremesof the dataaftera preliminary

Reading papers of Good, especially philosophicalones, is both easy and ad hoc separationof outliers. Examples of parallel displays of boxplots and

hard. It is easy because Good writes clearly and is often quite funny (inten- spreadversus level plots are given.

tionally);but it is hardbecause the ratioof ideas to examples is large, because Chapters4 and 8 describe the basic power transformations4p(x) = (xP -

there are frequent side trips, and because Good has a penchantfor naming 1)/p for p =$ 0 and 4o(x) = ln x. A brief discussion of transformationsfor

things "optimally," even if the names conflict with standardnames. (An symmetry, stable spread (- homogeneity), and matched transformationsis

example is the frequent use of "initial probability"and "final probability" given.

instead of "prior probability"and "posteriorprobability.") Of course, the Chapter 5 discusses resistant linear regression and a variety of methods

difference in terminology is partly the fault of others; Good was often there resistantto errorsin bothx andy, includingthose of Wald, NairandSrivastava,

first and his (eminentlysensible) names shouldthen take precedenceover later and Brown-Mood, Theil, and Siegel.

arrivals. Chapter6 introducesmedian polish for two-way tables, an algorithmthat

The book is as logically organizedas a collection of paperscan be, and the prescribesminimizing the sum of the absolute residuals alternatelyover row

lengthy introductionserves well to tie thingstogetherand provideperspective. and column effects in a two-way table. There is some discussion of the cir-

The mathematicallevel of the book should pose no difficulty for statistical cumstances when this algorithmconverges and when it converges to a least

readers. absolute residual solution and of breakdownbounds and resistance.

In conclusion, this is not a collection of outdatedpapers put together for Chapter7 is a,more traditionalbut excellent discussion of residualplots and

historicalreasons.The book addressesvital currentissues andis at the forefront diagnostics.

of statisticalthought. I heartilyrecommendit. Chapters9-12 concern robust estimationof location and scale and robust

confidence intervals. There are some tables that provide an updatedand less

JAMES 0. BERGER bewilderingcomparisonof the most prominentrobustestimatorsthan is avail-

Purdue University able, for example, in Andrews et al. (1972). These four chaptersprovide a

clear and simple perspectiveof principlesand practice in robustestimation.

REFERENCES To evaluate this book, I find it necessaryto separateexposition and theme.

Berger, James (1984), "The Robust Bayesian Viewpoint," in Robustness of Bayesian If the purpose of the book is to explain and illustratethe methods used in

Analyses, ed. J. B. Kadane, Amsterdam:North Holland, pp. 63-144. EDA to a readershipwith a moderate knowledge of statistics at an under-

Good, I. J. (1984), "TheBest Explicatumfor Weightof Evidence,"Journal of Statistical graduatelevel, then it is a considerablesuccess. In spite of the many authors,

Computingand Simulation, 19, C197. a clarity, consistency, and simplicity of style is maintainedthroughout;ab-

breviations,jargon, and terminologyparallelto that in the statisticalliterature

is less evident here than in some of the data analyticliterature.In many ways,

Understanding Robust and ExploratoryData Analysis. the authorsappearanxiousto bridgethe gap betweenEDA andmoretraditional

David C. Hoaglin, FrederickMosteller, and John W. Tukey (eds.), New statisticaltheory; some convergence of the two seems desirableif statistics is

York:John Wiley, 1983. xvi + 447 pp. $37.95. to progress.

In the debate between data analysts and more traditionalstatisticians,it is

The motivationfor this book can be summarizedby the following paragraph generally agreed that asymptotic optimality may have to be sacrificed for

quoted from the preface: improvedefficiency for small samples over a broaderrange of distributions:

the point of disagreementis the thresholdof evidence at which this sacrifice

The robustandresistanttechniquesthatwe discusshave considerablesupport is made. For some, the sacrifice of optimalityfor some naturalparentdistri-

in the statisticalresearchliterature,both at a highly abstractmathematical bution is a decision of last resort. They will not be satisfied by a collection

level and in extensive Monte Carlo studies. The book provides the basis of simple robustestimatorsprovidingreasonablesmall-sampleefficiency un-

for an adequateunderstandingof these techniques using examples and a less they are convinced that procedures (e.g., Pitman, BLUE, maximum

much reduced level of mathematicalsophistication. likelihood estimators)motivatedby a specific parentcannotcompete over the

The book consists of 12 chapters:"Stem and Leaf Displays," J. D. Emerson range of distributionsselected. For example, table 10-10 (p. 326) displays the

and D. C. Hoaglin; "Letter Values: A Set of Selected Order Statistics," variance of several estimators for different situations; maximum likelihood

D. C. Hoaglin; "Box Plots and Batch Comparisons," J. D. Emerson and estimators for only the Gauss and the double exponential are investigated.

J. Strenio; "TransformingData," J. D. Emersonand M. A. Stoto; "Resistant Some roughsimulationsindicatethata marginalmaximumlikelihoodestimator

Lines for y Versusx," J. D. Emersonand D. C. Hoaglin; "Analysis of Two- for the three-outliersituation does well comparedwith the estimatorslisted

Way Tables by Medians," J. D. Emerson and D. C. Hoaglin; "Examining there. Moreover, even though this is a more complicatedestimatorthan those

Residuals," C. Goodall; "MathematicalAspects of Transformation,"J. D. listed, it is easily programmed(in my case on an IBM personal computer)

Emerson;"Introductionto More Refined Estimators,"D. C. Hoaglin, F. Mos- using an EM iteration(Small 1984).

teller, and J. W. Tukey; "ComparingLocation Estimators:TrimmedMeans, A cautionarynote: It is apparentthat we need robust methods for viewing

Medians, and Trimean,"J. L. Rosenbergerand M. Gasko; "M-Estimatorsof tables of efficiencies of robust statistics. For example, the figures in Table 1

Location: An Outline of the Theory," C. Goodall; and "Robust Scale Esti- are takenfrom Andrewset al. (1972; A) and the book being reviewed (HMT).

mators and Confidence Intervalsfor Location," B. Iglewicz. Each chapteris The figures under HMT are from table 10-10 and are apparentlyexact. On

followed by a list of referencesand a set of problems, some of which contain the other hand, the simulatedvalue of .733 for the median at the slash dis-

data sets that provide interestingexamples of general statisticalinterest. tributionis repeatedin table 11-7. The obvious variabilityin values determined

This content downloaded from 188.72.126.88 on Sun, 15 Jun 2014 01:34:45 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

234 Journal of the American Statistical Association, March 1985

Table 1. Variances of Robust Statistics From Two Sources allows departuresof observed fertility from the standardover time as well as

age.

Parent distribution The book is separatedinto a process section (Chaps. 2-5) and an outcome

section (Chaps. 6-8). Chapter2 is a discussion of the methodand philosophy

Cauchy Slash of the EDA approachadvocated by John Tukey (1977). First applied to de-

Estimator mographicdata in McNeil and Tukey (1975), EDA emphasizes stepwise dis-

(n= 10) A HMT A HMT section of the data based on examinationof the residuals at each iteration.

The notion of a prior model is conspicuously absent. Instead, "the EDA

Median .366 .3362 .733 .7048 approachpermits the model of changing fertility patternsto grow out of the

Midmean .578 .4498 .841 .8389 time sequence data" (p. 2). The main steps of EDA are (a) examinationof

Trimean 1.331 .6348 1.042 1.1143 numericaland graphicalsummariesof the data, (b) reexpressionor transfor-

mation of data to improve linearity, (c) more complex descriptionof the data

NOTE: A = Andrews et al. (1972); HMT = Hoaglin et al. (1983).

in the form of fitted relationships,and (d) re-presentationof fitted relationships

in algebraicallyequivalentforms to facilitate the choice of a demographically

by simulation(cf. tables 11.4-11.10) surelyjustifies some referenceto stan-

interpretablemodel. Step (c) is carriedout by applicationof empiricalhigher

darderrors.

rank (EHR) analysis, the details of which are presentedin an appendix.This

There are some general criticisms that may be leveled at EDA, which

iteratively weighted fitted procedureis characterizedby two properties-ro-

consequently concern this book as well. Errorsor outliers in data sets are

bustnessto nonnormaldata, andresistanceto outliers-that makeit particularly

carefully accommodatedin EDA throughbroadermodels, resistantand robust

attractivefor exploratoryanalysis.

methods, andresidualanalysisand, in general, throughan enormousflexibility

Chapter 3 introducesthe 12 fertility sequences analyzed by EHR. These

of statisticaltools. Errorsin inferenceresultingfrom the use of the same data

include a variety of cross-section and cohort sequences for Swedish marital

for exploratoryandconfirmatorypurposesare not so carefullyguardedagainst;

and overall age-specific fertility. Cumulated, normalized age schedules are

for example, the prescriptionon page 2 reads: "A cycle of alternatinguses of

employed, ratherthan use of age-specific rates directly. For a cohort fertility

exploratoryand confirmatorytechniqueseither on successive smaller bodies

schedule, the cumulated,normalizedage-specific ratemeasuresthe proportion

of data or on a single substantialone is not uncommon and is often very

of the cohort's total fertility achievedby a given age. Fromthe cross-sectional

desirable."The greatflexibility of EDA tools will seriouslyimpairthe validity

point of view, the cumulated, normalized schedule gives the proportionof

of any of the usualconfirmatoryanalysesand increasethe dangerof overfitting.

total fertility in a given year that can be attributedto women of a given age

Plots such as those proposedto determinetransformationsto improve sym-

or younger. These data facilitate analysis of changes in the age patternof

metry combine the simplicity of a "theoretically"linear plot with an exceed-

fertility across years and cohorts in which total fertility has also undergone

ingly complicateddependentstructureamong "residuals"or departuresfrom

significant change. At a later point (Chap. 6), an attemptis made to control

linearity. One wondersto what extent an individuallacking extensive training

for the relationshipthat exists between the level and timing of cohortfertility.

with such plots is able to isolate the linear structurefrom the effects of the

Chapter4 discusses a key step in the exploratoryanalysis-examination of

dependence.

the residualsfor remainingstructureor pattern.Three types of plots are sug-

Phraseslike "If we rule out the Gaussianas a possible distributionbecause

gested for the purposeof evaluatingthe residuals-schematic plots that order

we believe that it has unrealisticallylight tails," and "If we omit the slash

residualsby size within an age category, scatterplotsthat summarizeresiduals

distributionfrom considerationfor having possibly unrealisticallyheavy tails

orderedin time sequence for pairs of age categories, and time sequence plots

for some circumstances"(p. 331) suggest a morerefinedjudgmentconcerning

for all age groups. Use of these plots facilitatesthe determinationof the level

the natureof the largely unobservablepart of the density than, I think, most

of complexity of the EHR description.The goal is to reduceresidualvariation

statisticianspossess.

about the fitted relationshipto isolated deviations that may be explained in

I also find section 9B, "Why the SymmetricCase?", not totally compelling

terms of singularevents or inferiordata.

and, uncharacteristicallyfor the subject, oriented towardmathematicalprag-

Chapter5, the last on process, addressesthe issue of how to present the

matics ratherthan the requirementsof real batches of data.

EHR results in a demographicallyinterpretablestandardform. The primary

In spite of the above mild reservations,I find this, on balance, an excellent

considerations in the choice of a standardform are to simplify the fitted

and highly readablebook suitable to a broad audience. Those of us rooted in

description, to select patternsrelated to underlyingdemographicprocesses,

the traditionsof optimalitycriteriaandlikelihoodtheorywill enjoy a refreshing

and to concentratein a single time parameterthe long-termtrend of change

excursion into pragmatism.Practitionerswill find this an excellent guide to

in the age patternof fertility that is associated with a decline in the overall

modernresults in EDA and robustness,unencumberedby complicatedmath-

level of fertility.

ematical derivations. All of us will benefit from rethinkingthe scope and

The balance of the book presents the results of applying the exploratory

direction of statistics; one of the major contributionsof books such as this

methods introducedin the first five chapters. Chapter6 considers the rela-

may' lie in this forced reanalysis. In conclusion, this book is highly recom-

tionship between cohort timing of childbearingand cohort fertility levels and

mended to all.

identifies major trends and transitionsin summarymeasuresof these dimen-

sions of Swedish demography. Some attention is given to the question of

D. L. McLEISH

relative data quality in the pre- and post-1860 periods, 1860 being the year

Universityof Waterloo

of the first modern census of populationby the Swedish CentralBureau of

Statistics. The chapterconcludes with an extensive analysisof regionalfertility

REFERENCES

change in the counties of Sweden over the period 1860-1970.

Andrews, D. F., Bickel, P. J., Hampel, F. R., Huber, P. J., Rogers, W. H., and Tukey, Chapter7 undertakesa comparisonof the EHR model and the Coale (1971)

J. W. (1972), RobustEstimatesof Location, Princeton,NJ: PrincetonUniversityPress. - Coale and Trussell(1974) model of maritalfertilityand will be of particular

Small, C. (1984), "Estimation by Marginal Maximum Likelihood for k-Outlier interestto demographers.The main conclusion of this exercise is that there is

Models," unpublishedTechnical Report, University of Waterloo.

a high level of compatibilitybetween the alternativedescriptions,but the EHR

model capturesmore of the variabilityof the data in the fitted descriptionthan

does the Coale model. The chapterconcludes with furtheranalysis of marital

fertility in Sweden.

Age, Time, and Fertility: Applications of Exploratory A detaileddescriptiveanalysisof Swedish fertilityby the EHR methodology

Data Analysis. will be of greaterutility if it is capable of producinga standardagainst which

Mary B. Breckenridge.New York: Academic Press, 1983. xxv + 317 the fertility of other countries can be measured.Chapter8 presentsevidence

pp. $39.50. for the generalityof the EHR age standardsby fitting the 1917-1968 portion

of U.S. age-specific overall fertility to an appropriateset of EHR parameters

This is a book that will interestboth studentsof Swedish populationhistory estimated from Swedish data. The positive results of this exercise imply the

and demographersseeking an introductionto the techniques of exploratory ability to make useful comparisonsof fertilitypatternsacrosspopulationsprior

data analysis (EDA). The demographicfocus of the study is 200 years of to a complete EHR analysis of all populations. Preliminaryanalysis of this

Swedish age-specific fertility rates (1775-1970) and the searchfor a standard sort is undertakenfor 48 countries, and the results are discussed in the re-

representationof demographicchange in the time domain. (For an accountof mainderof this last chapteron outcomes.

the origins of Swedish populationdata, see Hofsten and Lundstrom1976.) This book is recommendedreading for any demographerwith an interest

Previous work on what demographerscall "model fertility schedules," most in the applicationof new statistical methods to the long-standingproblemof

notably that of Coale (1971) and Coale and Trussell (1974), has been limited characterizingdemographicchange over time. The division of the chapters

to the derivationof fixed (in time) age standards.In the EDA approachBreck- into process and outcome sections provides a useful introductionto the EDA

enridge finds a procedurethat is sufficiently flexible to producea model that approachregardlessof whetherone has a substantiveinterestin the age pattern

This content downloaded from 188.72.126.88 on Sun, 15 Jun 2014 01:34:45 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

You might also like

- A Handbook of Small Data Sets D. J. Hand, F. Daly, A. D. Lunn, K. J. McConway A PDFDocument470 pagesA Handbook of Small Data Sets D. J. Hand, F. Daly, A. D. Lunn, K. J. McConway A PDFRodrigo ChangNo ratings yet

- Grua Grove 530e 2 Manual de PartesDocument713 pagesGrua Grove 530e 2 Manual de PartesGustavo100% (7)

- Shelly Cashman Series Microsoft Office 365 Excel 2016 Comprehensive 1st Edition Freund Solutions ManualDocument5 pagesShelly Cashman Series Microsoft Office 365 Excel 2016 Comprehensive 1st Edition Freund Solutions Manualjuanlucerofdqegwntai100% (10)

- Gracella Irwana - G - Pert 04 - Sia - 1Document35 pagesGracella Irwana - G - Pert 04 - Sia - 1Gracella IrwanaNo ratings yet

- American Statistical AssociationDocument3 pagesAmerican Statistical Associationpasid harlisaNo ratings yet

- Taylor & Francis, LTD., American Statistical Association, American Society For Quality TechnometricsDocument2 pagesTaylor & Francis, LTD., American Statistical Association, American Society For Quality TechnometricsArjel SalcedoNo ratings yet

- Forum: P Values, Hypothesis Testing, and Model Selection: It's de Ja' Vu All Over AgainDocument45 pagesForum: P Values, Hypothesis Testing, and Model Selection: It's de Ja' Vu All Over AgainAndres DíazNo ratings yet

- Binmore PDFDocument4 pagesBinmore PDFSol Mau B.No ratings yet

- (Probability and Its Applications) Mu-Fa Chen - Eigenvalues, Inequalities, and Ergodic Theory (Probability and Its Applications) (2004, Springer) - Libgen - Li PDFDocument239 pages(Probability and Its Applications) Mu-Fa Chen - Eigenvalues, Inequalities, and Ergodic Theory (Probability and Its Applications) (2004, Springer) - Libgen - Li PDFjkae romero100% (1)

- Book Reviews: Dgar RunnerDocument2 pagesBook Reviews: Dgar Runnermompou88No ratings yet

- Basic Measurement Theory: Patrick Suppes and Joseph L. ZinnesDocument134 pagesBasic Measurement Theory: Patrick Suppes and Joseph L. ZinnesYana PotNo ratings yet

- Archaeological Applications of Kernel Density Estimates PDFDocument8 pagesArchaeological Applications of Kernel Density Estimates PDFGustavo LuceroNo ratings yet

- EDASage PDFDocument8 pagesEDASage PDFmariammariNo ratings yet

- Lomnicki 1976Document3 pagesLomnicki 1976Carlos Bathuel Ramirez P.No ratings yet

- Review of Psychological Testing: A Practical Approach To Design and EvaluationDocument4 pagesReview of Psychological Testing: A Practical Approach To Design and EvaluationMat Baguio AcanisNo ratings yet

- Logical Theory and Semantic AnalysisDocument217 pagesLogical Theory and Semantic Analysissamir tounisianoNo ratings yet

- Specification and Testing of Some Modified Count Data ModelsDocument25 pagesSpecification and Testing of Some Modified Count Data ModelsSuci IsmadyaNo ratings yet

- GoodBadDifficult NEW - 4Document6 pagesGoodBadDifficult NEW - 4Workneh AlemuNo ratings yet

- Topics Feb21Document52 pagesTopics Feb21vivek thoratNo ratings yet

- Richard Carrier - Proving History or IdiocyDocument6 pagesRichard Carrier - Proving History or Idiocy50_BMGNo ratings yet

- Special Invited Paper: Multivariate Analysis by Data Depth: Descriptive Statistics, Graphics and InferenceDocument76 pagesSpecial Invited Paper: Multivariate Analysis by Data Depth: Descriptive Statistics, Graphics and InferenceSilvia Septi Rosa SitohangNo ratings yet

- Bachelor Thesis Formatierung WordDocument7 pagesBachelor Thesis Formatierung Worddnrrt4fr100% (2)

- Generalizability TheoryDocument7 pagesGeneralizability TheoryLaura ChiticariuNo ratings yet

- Copyright SpringerDocument19 pagesCopyright SpringerASGNo ratings yet

- History of Factor AnalysisDocument17 pagesHistory of Factor AnalysisPratiwi CahyaniBNo ratings yet

- Eerola 1998Document2 pagesEerola 1998wad elshaikhNo ratings yet

- Lectures For Chemists On StatisticDocument7 pagesLectures For Chemists On StatisticFransiska WardhaniNo ratings yet

- Statistical Decision Theory and Bayesian AnalysisDocument632 pagesStatistical Decision Theory and Bayesian AnalysisFernandaNo ratings yet

- Journal of Statistical Software: July 2008, Volume 26, Book Review 2Document3 pagesJournal of Statistical Software: July 2008, Volume 26, Book Review 2srknlkn83No ratings yet

- Learning Probabilistic NetworksDocument38 pagesLearning Probabilistic NetworksFrancisco AragaoNo ratings yet

- Carrier-Proving History or IdiocyDocument4 pagesCarrier-Proving History or Idiocy50_BMG100% (2)

- Big Data of Materials Science: Critical Role of The DescriptorDocument5 pagesBig Data of Materials Science: Critical Role of The DescriptorDivyansh SrivastavaNo ratings yet

- Koenker, R., & Bassett, G. (1978) - Regression QuantilesDocument24 pagesKoenker, R., & Bassett, G. (1978) - Regression QuantilesIlham AtmajaNo ratings yet

- Critique FinalDocument6 pagesCritique FinalnadirehsoNo ratings yet

- The MIT PressDocument12 pagesThe MIT PressGHULAM MURTAZANo ratings yet

- The Role of Significance Tests1: D. R. CoxDocument22 pagesThe Role of Significance Tests1: D. R. CoxMusiur Raza AbidiNo ratings yet

- Statistical ModelDocument9 pagesStatistical ModelRae SecretariaNo ratings yet

- American Statistical AssociationDocument3 pagesAmerican Statistical AssociationSufira WahyuniNo ratings yet

- 14 - An Introduction To Ensemble Methods For Data AnalysisDocument38 pages14 - An Introduction To Ensemble Methods For Data AnalysisEnzo GarabatosNo ratings yet

- Correlated Topic Models: David M. Blei John D. LaffertyDocument8 pagesCorrelated Topic Models: David M. Blei John D. Laffertyandrea ramirezNo ratings yet

- Which Spatial Partition Trees Are Adaptive To Intrinsic DimensionDocument12 pagesWhich Spatial Partition Trees Are Adaptive To Intrinsic DimensionOmega AlphaNo ratings yet

- Principles of Data Analysis - Prasenjit Saha (2003) PDFDocument86 pagesPrinciples of Data Analysis - Prasenjit Saha (2003) PDFasantambNo ratings yet

- Bentler BonettDocument20 pagesBentler Bonettmkubra44No ratings yet

- American Statistical AssociationDocument5 pagesAmerican Statistical AssociationpaolaNo ratings yet

- Practical Statistics For Particle Physics: © CERN, 2020,,, ISSN 0531-4283Document49 pagesPractical Statistics For Particle Physics: © CERN, 2020,,, ISSN 0531-4283Tuan PhamNo ratings yet

- Survey: Real Analysis Exchange Vol. 39 (2), 2013/2014, Pp. 261-304Document44 pagesSurvey: Real Analysis Exchange Vol. 39 (2), 2013/2014, Pp. 261-304Oscar PadillaNo ratings yet

- Substantive Theory and Constructive Measures: A Collection of Chapters and Measurement Commentary on Causal ScienceFrom EverandSubstantive Theory and Constructive Measures: A Collection of Chapters and Measurement Commentary on Causal ScienceNo ratings yet

- Kennedy 01Document39 pagesKennedy 01Mayra GarcíaRodríguezNo ratings yet

- American Statistical Association, American Society For Quality, Taylor & Francis, Ltd. TechnometricsDocument4 pagesAmerican Statistical Association, American Society For Quality, Taylor & Francis, Ltd. TechnometricsrameshNo ratings yet

- Statistical Strategies For Avoiding False Discoveries in Metabolomics and Related Experiments - 2007 - Broadhurst, KellDocument26 pagesStatistical Strategies For Avoiding False Discoveries in Metabolomics and Related Experiments - 2007 - Broadhurst, KellmasurNo ratings yet

- (1981) - Fowler, D. Anthyphairetic Ratio and Eudoxan ProportionDocument5 pages(1981) - Fowler, D. Anthyphairetic Ratio and Eudoxan ProportionnayibeNo ratings yet

- Exploratory Data Analysis Stephan Morgenthaler (2009)Document12 pagesExploratory Data Analysis Stephan Morgenthaler (2009)s8nd11d UNI100% (2)

- American Statistical Association, Taylor & Francis, Ltd. Journal of The American Statistical AssociationDocument2 pagesAmerican Statistical Association, Taylor & Francis, Ltd. Journal of The American Statistical Associationahmed22gouda22No ratings yet

- Lecture Notes in Statistics 148Document241 pagesLecture Notes in Statistics 148argha48126No ratings yet

- Interpreting DNA Evidence Statistical Genetics ForDocument3 pagesInterpreting DNA Evidence Statistical Genetics ForgeorgianaNo ratings yet

- Sample in Thesis WritingDocument4 pagesSample in Thesis WritingYolanda Ivey100% (2)

- 6134 Math StatsDocument4 pages6134 Math Statscsrajmohan2924No ratings yet

- Ias and Airness: Train/Test MismatchDocument12 pagesIas and Airness: Train/Test MismatchJiahong HeNo ratings yet

- Rosenthal 1979 Psych BulletinDocument4 pagesRosenthal 1979 Psych BulletinChris El HadiNo ratings yet

- Destercke 22 ADocument11 pagesDestercke 22 AleftyjoyNo ratings yet

- Ref 14Document29 pagesRef 14XA Atmane AYNo ratings yet

- ASTR 323 Homework 4Document2 pagesASTR 323 Homework 4Andrew IvanovNo ratings yet

- EDAG0007Document5 pagesEDAG0007krunalNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1 INTRODUCTION TO LITERATUREDocument4 pagesChapter 1 INTRODUCTION TO LITERATUREDominique TurlaNo ratings yet

- LT3845ADocument26 pagesLT3845Asoft4gsmNo ratings yet

- Half Yearly Examination, 2017-18: MathematicsDocument7 pagesHalf Yearly Examination, 2017-18: MathematicsSusanket DuttaNo ratings yet

- Presentation LI: Prepared by Muhammad Zaim Ihtisham Bin Mohd Jamal A17KA5273 13 September 2022Document9 pagesPresentation LI: Prepared by Muhammad Zaim Ihtisham Bin Mohd Jamal A17KA5273 13 September 2022dakmts07No ratings yet

- DatuinMA (Activity #5 - NSTP 10)Document2 pagesDatuinMA (Activity #5 - NSTP 10)Marc Alen Porlaje DatuinNo ratings yet

- Nursing Assessment in Family Nursing PracticeDocument22 pagesNursing Assessment in Family Nursing PracticeHydra Olivar - PantilganNo ratings yet

- Coal Mining Technology and SafetyDocument313 pagesCoal Mining Technology and Safetymuratandac3357No ratings yet

- Unit 3: Theories and Principles in The Use and Design of Technology Driven Learning LessonsDocument5 pagesUnit 3: Theories and Principles in The Use and Design of Technology Driven Learning Lessons서재배No ratings yet

- WD Support Warranty Services Business Return Material Authorization RMA Pre Mailer For ResellerDocument3 pagesWD Support Warranty Services Business Return Material Authorization RMA Pre Mailer For ResellerZowl SaidinNo ratings yet

- Collins Ks3 Science Homework Book 3Document5 pagesCollins Ks3 Science Homework Book 3g3pz0n5h100% (1)

- High Speed Power TransferDocument33 pagesHigh Speed Power TransferJAYKUMAR SINGHNo ratings yet

- PV Power To Methane: Draft Assignment 2Document13 pagesPV Power To Methane: Draft Assignment 2Ardiansyah ARNo ratings yet

- Sub-Wings of YuvanjaliDocument2 pagesSub-Wings of Yuvanjalin_tapovan987100% (1)

- Intercultural Personhood and Identity NegotiationDocument13 pagesIntercultural Personhood and Identity NegotiationJoão HorrNo ratings yet

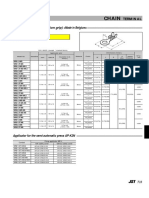

- Chain: SRB Series (With Insulation Grip)Document1 pageChain: SRB Series (With Insulation Grip)shankarNo ratings yet

- Debate Brochure PDFDocument2 pagesDebate Brochure PDFShehzada FarhaanNo ratings yet

- Entrepreneurial MotivationDocument18 pagesEntrepreneurial MotivationRagavendra RagsNo ratings yet

- Class 1 KeyDocument3 pagesClass 1 Keyshivamsingh.fscNo ratings yet

- Buddha Mind PDFDocument32 pagesBuddha Mind PDFVishal GadeNo ratings yet

- Masking Conventional Metallic Cast Post For Enhancing EstheticsDocument5 pagesMasking Conventional Metallic Cast Post For Enhancing EstheticsleilyanisariNo ratings yet

- Teaching PowerPoint Slides - Chapter 5Document19 pagesTeaching PowerPoint Slides - Chapter 5Azril ShazwanNo ratings yet

- Gigabyte Ga b85m Ds3h A r10 PDFDocument30 pagesGigabyte Ga b85m Ds3h A r10 PDFMartha Lorena TijerinoNo ratings yet

- LP Pe 3Q - ShaynevillafuerteDocument3 pagesLP Pe 3Q - ShaynevillafuerteMa. Shayne Rose VillafuerteNo ratings yet

- Earth Science NAME - DATEDocument3 pagesEarth Science NAME - DATEArlene CalataNo ratings yet

- 1.classification of Reciprocating PumpsDocument8 pages1.classification of Reciprocating Pumpsgonri lynnNo ratings yet