Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Comparative Effects of LO-mg Versus 80-Mg Atorvastatin On High-Sensitivity C-Reactive Protein

Uploaded by

ferdianriskaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Comparative Effects of LO-mg Versus 80-Mg Atorvastatin On High-Sensitivity C-Reactive Protein

Uploaded by

ferdianriskaCopyright:

Available Formats

Clinical Therapeutics/Volume 30, Number 12, 2008

Comparative Effects of lO-mg Versus 80-mg Atorvastatin on

High-Sensitivity C-Reactive Protein in Patients with Stable

Coronary Artery Disease: Results of the CAP (Comparative

Atorvastatin Pleiotropic Effects) Study

Jacques Bonnet, MD1; R. McPherson, MD, PhD2; A. Tedgui, MD3; D. Simoneau, MD4;

A. Nozza, MSc5; P. Martineau, PharmD5; and Jean Davignon, MD6; forthe CAP Investigators*

1H6pital du Haut-Leveque, Pessac, France; 2University of Ottawa Heart Institute, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada;

31NSERM, Paris, France; 4Medical Division, Pfizer France, Paris, France; sMedical Division, Pfizer Canada,

Kirkland, Quebec, Canada; and 6C!inical Research Institute of Montreal, Montreal, Quebec, Canada

ABSTRACT time points, were also calculated. The secondary effi-

Background: The major beneficial effect of statins- cacy variables included the percentage changes from

reducing the risk for coronary events-has primar- baseline in lipid parameters (LDL-C, high-density lipo-

ily been ascribed to reductions in low-density protein cholesterol [HDL-C], total cholesterol [TC], TG,

lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) but may in part be apolipoprotein B, non-HDL-C, and TC:HDL-C ratio)

related to a direct antiinflammatory action (ie, de- at 5, 13, and 26 weeks of treatment. Tolerability was

creased high-sensitivity C-reactive protein [hs-CRP] assessed using physical examination, including vital

concentration). sign measurement, and laboratory analyses.

Objectives: The objectives of this CAP (Comparative Results: A total of 339 patients were enrolled

Atorvastatin Pleiotropic Effects) study were to com- (283 men, 56 women; mean age, 62.5 years; weight,

pare the effects of low- versus high-dose atorvastatin 81.3 kg; 10-mg/d group, 170 patients; 80-mg/d group,

on hs-CRP concentrations and to determine the rela- 169). No significant differences in baseline demograph-

tionship between changes in LDL-C and hs-CRP con- ic or clinical data were found between the 2 treatment

centrations in patients with coronary artery disease arms. In the 10-mg group, hs-CRP was decreased

(CAD), low-grade inflammation, and normal lipo- by 25.0% at 5 weeks and remained stable thereafter

protein concentrations. (%1'1 at week 26, -24.3%; P < 0.01). In the 80-mg

Methods: This multicenter, prospective, randomized, group, hs-CRP was decreased by 36.4% at 5 weeks and

double-blind, double-dummy study was conducted at continued to be decreased over the study period

65 centers across Canada and Europe. Patients with (%1'1, -57.1 % at week 26; P < 0.001 vs baseline). At

documented CAD, low-grade inflammation (hs-CRP 5 weeks, LDL-C was decreased by 35.9% in the

concentration, 1.5-15.0 mg/L), and a normal-range 10-mg group and by 52.7% in the 80-mg group

lipid profile (LDL-C concentration, 1.29-3.87 mmol/L (P < 0.001 between groups) and remained stable

[50-150 mg/dL]; triglyceride [TG] concentration, thereafter (%1'1 at week 26, -34.8% and -51.3%, re-

<4.56 mmoUL [<400 mg/dL]) were randomly assigned spectively; P < 0.001 between groups). The NCEP

to receive 26-week double-blind treatment with ator- ATP III LDL-C target of <2.59 mmol/L (<100 mg/dL)

vastatin 10 or 80 mg QD. Investigators were to aim for was reached in 77.1 % of patients treated with atorva-

the National Cholesterol Education Program Adult statin 10 mg and 92.3% of those treated with 80 mg

Treatment Panel III (NCEP ATP III) LDL-C target of (P < 0.001). Dual targets of hs-CRP <2 mg/L and

<2.59 mmol/L (<100 mg/dL). The primary end point

was the percentage change from baseline in hs-CRP,

*The CAP Investigators are listed In the Acknowledgments.

as measured at baseline and weeks 5, 13, and 26 using

Accepted for publicatIOn October 17, 2008

high-sensitivity, latex microparticle-enhanced immu- dOl:1 0.1 016/J.cIInthera.2008.12.023

noturbidimetric assay. Changes from baseline in 0149-2918/$32.00

LDL-C, as measured directly in serum at the same © 2008 Excerpta Medica Inc. All nghts reserved.

2298 Volume 30 Number 12

J. Bonnet et al.

LDL-C <1.81 mmol/L «70 mg/dL) were reached in the median) hs-CRP concentration (0.58 mg/L [95%

a significantly greater proportion of patients in the CI, 0.34-0.98 mg/L]) compared with those with low

80-mg group compared with the 10-mg group (55.6% (less than the median) hs-CRP (1.08 mg/L [95% CI,

vs 13.5%; P < 0.001). The decrease in hs-CRP was 0.56-2.08 mg/L ]).10

largely independent of baseline LDL-C and change Results from AFCAPSlTexCAPSlO and the CARE

in LDL-C. Two serious adverse events were reported (Cholesterol and Recurrent Events) triaP1,12 have sug-

by the investigator as treatment related: acute hepati- gested that the decreases in CRP with statin use may

tis in the 10-mg group and intrahepatic cholestasis in be independent of LDL-C concentrations. In AFCAPS/

the 80-mg group, in 2 patients with multiple comor- TexCAPS, the effect of lovastatin on hs-CRP concen-

bidities. Two deaths occurred during the study, both in tration was not found to be significantly related to the

the atorvastatin 80-mg group (1, myocardial infarc- effect of lovastatin on lipid levels; the Spearman cor-

tion; 1, sudden death), neither of which was deemed relation coefficients for the relationship between the

treatment related by the investigator. percentage change in hs-CRP level and the percentage

Conclusions: In these patients with documented change in total cholesterol (TC) and LDL-C concen-

CAD, evidence of low-grade inflammation, and normal- trations were -0.001 and 0.014, respectively. 10 In the

range lipid profiles, the effects of atorvastatin on chang- CARE trial,11,12 at 5 years of follow-up, no significant

es in hs-CRP were dose dependent, with the high dose correlation was observed between the magnitude of

(80 mg) being associated with significantly greater re- change in hs-CRP and the magnitude of change in

ductions in hs-CRP concentrations. Both doses were LDL-C among 472 patients who received pravastatin

associated with a significant and progressive decline 40 mg/d or placebo. 12

in hs-CRP largely independent of changes in LDL-C, In 4162 patients with acute coronary syndrome

HDL-C, and TG. Clinical Trials Identification Number: (ACS) enrolled in the PROVE IT-TIMI 22 (Pravastatin

NCT00163202. (Clin Ther. 2008:30:2298-2313) © or Atorvastatin Evaluation and Infection Therapy-

2008 Excerpta Medica Inc. Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction 22) trial,13 those

Key words: cardiovascular diseases, cholesterol, lipids, with hs-CRP concentrations <2 mg/L after treatment with

lipoproteins, C-reactive protein. pravastatin 40 mg/d or atorvastatin 80 mg/d for a

mean duration of 24 months had significantly fewer

recurrent events compared with those with hs-

INTRODUCTION CRP concentrations >2 mg/L (2.8 vs 3.9 events per

In individuals with and without established coronary ar- 100 person-years; P = 0.006), regardless of the LDL-C

tery disease (CAD), C-reactive protein (CRP) is a robust concentration reached. 14 Reductions in hs-CRP were

marker of inflammation, and plasma high-sensitivity significant at 1 month in PROVE IT-TIMI 22 but

(hs)-CRP has been found to be a predictor of risk for did not reach significance until 4 months in the A

coronary events. 1 Evidence suggests that CRP may be to Z trial 15 in 4497 patients who received simvastat-

involved in the atherothrombotic process. I - 4 CRP is in (40 mg/d for 1 month, then 80 mg/d for 23 months)

also believed to be a regulator of endothelial function, or 4-month placebo followed by 20 mg/d for the re-

vascular remodeling, and thrombosis. 4- 7 mainder of the trial. 16,17 At the same time, there was

Statin treatment has been associated with reduced an early (0-4 months) favorable separation of event

plasma cholesterol concentrations; in a meta-analysis curves in PROVE IT-TIMI 22 (hazard ratio [HR],

of 14 trials in 90,056 patients, 8 statins were associated 0.80), but not in A to Z (HR, 1.17), suggesting a pos-

with a mean low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) sible benefit associated with the early CRP reduc-

difference at 1 year of 1.09 mmol/L compared with tion. 16 ,17 In the MIRACL (Myocardial Ischemia Re-

controls. In AFCAPSlTexCAPS (Air ForcelTexas Coro- duction with Aggressive Cholesterol Lowering) study, 18

nary Atherosclerosis Prevention Study),9 5742 pa- 16-week administration of high-dose atorvastatin

tients received lovastatin 20 to 40 mg/d or placebo for (80 mg/d) versus placebo was associated with a signifi-

a mean duration of 5.2 years. A significantly greater cant reduction in CRP (-86% vs -78%; P < 0.001) in

reduction in the relative risk for coronary events was patients with ACS and LDL-C <3.2 mmol/L.1 9

found in patients with low (less than the median) Although the results from those previously pub-

LDL-C concentration who had a high (greater than lished studies 10,12,14,16,17,19 have suggested that statin

December 2008 2299

Clinical Therapeutics

use is associated with decreased hs-CRP concen- secondary hyperlipidemia or type 1 diabetes mellitus

trations, a randomized controlled trial (RCT) in (DM) or type 2 DM with insulin therapy, inadequately

107 patients with stable CAD and high (>3 mg/L) hs- controlled DM (glycosylated hemoglobin, >9%), body

CRP levels did not find a dose-response relationship mass index >32 kg/m 2, history or presence of alcohol

between simvastatin 80 mg or 20 mg/d for 12 weeks or drug abuse, inability to comply with study proce-

and decreases in hs-CRP levels (-0.6 vs -0.5 mg/L).20 dures, progressive or life-threatening disease with a

A meta-analysis of 14 randomized trials in 90,056 pa- life expectancy of <1 year, contraindication to statin

tients found that statin treatment was associated with treatment (history of intolerance or hypersensitivity

a significantly reduced incidence of major coronary events to statins, active hepatic disease, or hepatic dysfunc-

compared with controls (21 %; rate ratio = 0.79; 95% tion), and/or current treatment with a potent cyto-

CI, 0.77-0.81; P < 0.001).8 The clinical benefit of stat- chrome P450 3A4 inhibitor (eg, erythromycin, keto-

ins may be related not only to their lipid-lowering ef- conazole). Women who were pregnant or breastfeeding

fects but also to other pleiotropic effects, such as anti- were excluded. Eligible women of childbearing poten-

inflammatory, immunomodulatory, antithrombotic, tial were required to use an effective method of con-

and vascular effects. 21 traception throughout the study period.

The objectives of this Comparative Atorvastatin

Pleiotropic Effects (CAP) study were to compare the Study Drugs

effects of low- versus high-dose atorvastatin on hs-CRP After an initial 6-week washout period in patients

concentrations, and to determine the relationship be- who had been receiving statin treatment, fibrates, nia-

tween changes in LDL-C and hs-CRP concentrations in cin, and/or resins prior to selection, patients were

patients with stable CAD, evidence of low-grade in- randomized in a 1:1 ratio to receive one of the follow-

flammation, and normal lipoprotein concentrations. ing treatment schedules: two 40-mg atorvastatin tab-

lets and 1 placebo tablet of atorvastatin 10 mg, or one

PATIENTS AND METHODS 10-mg atorvastatin tablet and 2 placebo tablets of

Study Design atorvastatin 40 mg (Figure 1). Patients were random-

This CAP study used a 26-week, multicenter, pro- ized at visit 2, with treatment being allocated in nu-

spective, randomized, double-blind, double-dummy meric order. The double-blind study drug supplies

design and was conducted at 65 sites in Canada and were delivered to investigators in sealed, numbered

Europe. The relevant institutional review boards ap- randomization envelopes according to the computer-

proved the protocol, and written informed consent generated randomization code.

was obtained from all patients before study entry. This Patients could continue, at a stable dosing regimen,

study was conducted in compliance with the ethical their usual antihypertensive and antianginal treatment

principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. 22 during the study. Patients could receive short (:C:;7 days)

courses of antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs, cyclo-

Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria oxygenase-2 inhibitors, or corticosteroids) if treat-

Eligible patients included men and women aged ment was discontinued ~1 week before each hs-CRP

<80 years with documented CAD, low-grade inflam- assessment (weeks 0 [baseline], 5, 13, and 26). Long-

mation (hs-CRP concentration, 1.5-15.0 mg/L), and a course (~7-day) treatment with these agents was not

normal-range lipid profile (LDL-C concentration, 1.29- permitted. Treatment with acetylsalicylic acid at doses

3.87 mmol/L [50-150 mg/dL]; triglyceride [TG] con- of :c:;325 mg/d was permitted.

centration, :c:;4.56 mmol/L [:c:;400 mg/dL]). CAD was

defined as the presence of ~1 of the following: history Efficacy Assessments

of myocardial infarction (~3 months before screening), The primary efficacy end point was the percentage

stable angina, history of unstable angina, history of change from baseline to 26 weeks in hs-CRP concen-

percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty and! trations with atorvastatin 10 and 80 mg/d. The sec-

or coronary artery bypass grafting (~6 months before ondary efficacy variables included the percentage

screening), and/or coronary stenosis ~50%. changes from baseline in lipid parameters (LDL-C,

Patients were considered ineligible for the study if high-density lipoprotein cholesterol [HDL-C], TC, TG,

they met any of the following criteria: presence of apolipoproteinB [apoB],non-HDL-C,andTC:HDL-C

2300 Volume 30 Number 12

J. Bonnet et al.

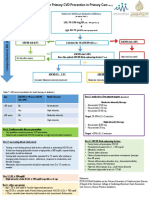

Randomized to treatment

(N ~ 340)

Atorvastatm 10 mg Atorvastatm 80 mg

(n~170) (n ~ 169*)

Completed Withdrawn (n ~ 13) Completed Withdrawn (n ~ 16)

(n~157) Adverse event t (7) (n ~ 153) Adverse event§ (10)

Protocol violation (2) Withdrawn consent (4)

Withdrawn consent (2) Death (2)

Other* (2)

Figure 1. Study design and disposition of patients assigned to receive 26-week treatment with atorvastatin

10 or 80 mg in patients with stable coronary artery disease (modified intent-to-treat [ITT] popula-

tion). *One patient was not included in the ITT analysis due to lack of postbaseline data. tlncluded

asthenia and myalgia (2 patients); cerebrovascular accident (2 patients); and atrial fibrillation and

palpitations, chest pain, and leg cramps (1 patient). :j:lncluded loss to follow-up and investigator

decision based on patient noncompliance (1 patient each). §Included myalgia (2 patients), and

weight loss, asthenia, abdominal pain, anemia, liver damage, dyspepsia, increased alanine amino-

transferase, atrial fibrillation, and myalgia (1 patient).

ratio) at 5, 13, and 26 weeks of treatment. The rela- Tolerability Assessment

tionship between changes in hs-CRP and LDL-C was Tolerability analyses included adverse events re-

also evaluated. ported and/or observed during clinical examination,

which included monitoring of vital signs (heart rate,

Laboratory Analyses blood pressure, electrocardiography and laboratory

For hs-CRP assessment, blood samples were drawn analyses (tolerability parameters, including alanine

by a registered nurse or phlebotomist as per usual prac- aminotransferase [ALT] , aspartate aminotransferase

tice at each site into dry tubes and EDTA tubes. The [AST], and creatine kinase [CK]).

tubes were centrifuged for 10 minutes at 1500g and

stored at 4 D C or -20 D C, depending on which test was Statistical Analysis

being run, until shipped on dry ice to a centrallabora- Primary efficacy analysis was performed on the

tory (Focus Bio-Inova Global Laboratory Services, modified intent-to-treat (mITT) population, which con-

Herndon, Virginia). hs-CRP was measured with high- sisted of all patients who were randomized to treat-

sensitivity, latex microparticle-enhanced immunotur- ment, received ~1 dose of assigned treatment, and had

bidimetric assay using a commercial kit (Tina-quant, data available from ~1 postbaseline assessment of the

Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Mannheim, Germany). primary end point (hs-CRP concentration). Missing

TC and TG were measured using an enzymat- values were replaced according to the last-observation-

ic colorimetric assay. LDL-C and HDL-C were mea- carried-forward (LOCF) approach. Patients with no

sured directly using a homogeneous enzymatic colo- on-treatment data for a parameter were excluded from

rimetric assay, and apoB was measured using an the analysis of that parameter. The per-protocol popu-

immunoturbidimetric assay (Roche Diagnostics lation consisted of all patients randomized to treatment

GmbH). who received study drug ~20 weeks and had no major

December 2008 2301

Clinical Therapeutics

protocol deviations. The tolerability analysis included (LOCF), the mean changes in hs-CRP were -20.8%

all patients who were randomized to treatment and (-31.6% to -8.3 %) in the 10-mg group and -54.9%

received ~1 dose of assigned treatment. (-60.6% to -48.5%) in the 80-mg group.

The hs-CRP concentrations were not normally dis-

tributed and therefore are reported as geometric means. Secondary End Points

Percentage changes from baseline (mean of screening The effects of atorvastatin on plasma lipid concen-

and baseline values) to week 26 were compared be- trations and apoB are outlined in Figure 3. At study

tween the 2 treatment groups using a 2-tailed Mann- end, the mean (95% CI) percentage changes in LDL-C

Whitney U test. 23 ,24 Changes from baseline in lipid were -34.8% (-37.5% to -32.0%) with the 10-mg

parameters were assessed using the t test. dose and -51.3% (-54.5% to -48.1 %) with the 80-mg

Spearman's rank correlation coefficient23 ,24 was dose. These decreases were evident at the first visit

used to test for correlations between changes in hs- (5 weeks) and remained stable thereafter (Figure 3).

CRP and LDL-C. Significance level was fixed at 0.05. TC, TG, apoB, non-HDL-C, and TC:HDL-C ratio

Because this was an exploratory study, no adjustment were all found to have a similar pattern, decreasing by

for multiplicity was used. 5 weeks and remaining stable until study end, with

A post hoc analysis was conducted to determine changes from baseline being significantly greater with

the proportions of patients in whom the most recently atorvastatin 80 mg compared with 10 mg for each of

proposed National Cholesterol Education Program these lipid parameters at all time points (P < 0.005).

(NCEP) targets (hs-CRP, <2 mg/I)4; LDL-C, <100 mg! As expected, changes in HDL-C were less consistent,

dL [<70 mg!dLj25,26) were reached. with a mean change at study end of +3.6% with the

10-mg dose and +0.8% with the 80-mg dose (P = 0.01).

RESULTS On analysis according to tertiles of baseline hs-

Patient Disposition CRP concentrations, those in the highest tertile were

Between May 2002 and January 2005,1198 patients found to have the greatest changes from baseline in

were screened and 340 were randomized to receive hs-CRP (-37.2% and -69.3% in the 10- and 80-mg

treatment at 65 sites in France, Canada, Poland, the groups, respectively; P < 0.001) (Figure 4).

Czech Republic, Romania, Slovakia, and Russia. Of the

858 screening failures, 806 did not meet entry criteria Correlation Between Reduction in hs-CRP and

and 37 withdrew consent. Consequently, the tolerability Lipid Parameters

population included 340 patients, and the mITT popu- The decrease in hs-CRP was largely independent

lation included 339. The proportions of patients who of baseline LDL-C and change in LDL-C and totally

completed the study were 92.4% in the 10-mg group independent of changes in HDL-C and TG, regardless

and 90.5% in the 80-mg group (Figure 1). of dose (Table II). Although the P value suggested

There were no meaningful significant differences statistical significance, the correlation between hs-

between the 2 treatment groups in baseline demo- CRP and LDL-C was small, with <5% of change in

graphic or clinical characteristics (Table I). hs-CRP being explained by changes in LDL-C. In the

10-mg group, hs-CRP concentrations were significantly

Primary End Point correlated with LDL-C concentrations (r2 = 0.032;

The mean (95% CI) baseline hs-CRP concentra- P = 0.016), whereas the change in hs-CRP was not

tion was 3.1 (2.8-3.5) mg/L and 3.6 (3.2-3.9) mg/L correlated with change in LDL-C (r2 = 0.0036; P = NS)

in the atorvastatin 10- and 80-mg groups, respec- (Table II). In the 80-mg group, the hs-CRP and LDL-C

tively (Figure 2). In the 10-mg group, the mean per- concentrations (r2 = 0.0484; P = 0.005) and changes

centage change in hs-CRP at 5 weeks was -25.0% in hs-CRP and LDL-C were significantly correlated

(-32.7% to -16.6%); hs-CRP remained stable there- (r2 = 0.0484; P = 0.003).

after. In the 80-mg group, hs-CRP changed by

-36.4% (-43.8% to -28.0%) at 5 weeks and contin- LDL-C and hs-CRP Treatment Targets

ued to decrease for the duration of the study period, The proportions of patients in whom recommend-

with a total change of -57.1 % (-62.3% to -51.2%) ed targets for LDL-C were reached are shown in

at 26 weeks (P < 0.001 vs baseline). At study end Figure 5. The NCEP Adult Treatment Panel (ATP) III

2302 Volume 30 Number 12

J. Bonnet et al.

Table I. Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of the study population.

Atorvastatin 10 mg Atorvastatin 80 mg

Characteristic (n = 170) (n = 169)

Age, mean (SO), y 62.8 (8.9) 62.3 (9.7)

Sex, no. (%)

Male 144 (84.7) 139 (82.2)

Female 26 (15.3) 30 (17.8)

Weight, kg

Mean (SO) 81.5 (12.3) 80.8 (12.6)

Range 51.0-111.0 49.0-110.0

BMI, kgjm 2

Mean (SO) 27.8 (3.3) 27.8 (3.1)

Median (range) 27.7 (27.2-28.2) 27.7 (27.3-28.2)

Vital signs, mean (95% CI)

OBP, mm Hg 77.1 (75.9-78.3) 77.3 (76.1-78.5)

SBP, mm Hg 129.4 (127.3-131.5) 128.9 (126.5-131.4)

Heart rate, bpm* 63.6 (62.1-65.1) 65.8 (64.3-67.3)

Lipid parameters, mean (95% CI)

LOL-C

mmoljL 3.26 (3.16-3.34) 3.26 (3.19-3.34)

mgjdL 126 (122-129) 126 (123-129)

HOL-C

mmoljL 1.24 (1.22-1.30) 1.24 (1.19-1.30)

mgjdL 48 (47-50) 48 (46-50)

Non-HOL-C

mmoljL 4.16 (4.06-4.27) 4.10 (3.99-4.20)

mgjdL 160.62 (156.76-164.86) 158.30 (154.05-162.16)

TCjHOL-C ratio 4.59 (4.40-4.77) 4.58 (4.40-4.75)

ApoBt

mmoljL 5.52 (5.39-5.65) 5.39 (5.26-5.49)

mgjdL 213 (208-218) 208 (203-212)

TC

mmoljL 5.41 (5.31-5.52) 5.34 (5.23-5.44)

mgjdL 209 (205-213) 206 (202-210)

TG

mmoljL 2.05 (1.89-2.20) 1.85 (1.72-1.98)

mgjdL 181 (167-195) 164 (152-175)

Inflammatory marker, GM (95% CI)

hs-CRP, mgjL 3.13 (2.84-3.45) 3.56 (3.22-3.94)

Smokers, no. (%) 25 (14.7) 20 (11.8)

BMI ~ body mass Index; DBP ~ diastolic blood pressure; SBP ~ systolic blood pressure; LDL-C ~ low-density lipoprotein

cholesterol; HDL-C ~ high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; TC ~ total cholesterol; ApoB ~ apollpoproteln B; TG ~ tnglyc-

endes; GM ~ geometnc mean; hs-CRP ~ high-sensitivity C-reactive protein.

*P ~ 0.024 (Mann-Whitney U test).

t n ~ 161 (10 mg) and n ~ 160 (80 mg).

December 2008 2303

Clinical Therapeutics

- . Atorvastatln 10 mg (n ~ 170)

• Atorvastatln 80 mg (n ~ 169)

A B

4

Study Week

2 4 6 8 10 12 14 16 18 20 22 24 26 LOCF

___-'------J-----'-------"-----'-------"------'------J-----'-------"-----'-------"------'--,{Ll

:=J 3

~

E

0...

• 0...

-10

0::: 2 0::: t

l( -20

l(

Vl

..c • Vl

..c

t t •

~ ~ -30

Q Q

c

-<I -40

?f2.

o ~

-50

o 2 4 6 8 10 12 14 16 18 20 22 24 26 LOCF

Study Week -60

•

Figure 2. (A) Geometric mean (GM) high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP) concentrations over 26-week

treatment with atorvastatin 10 or 80 mg in patients with stable coronary artery disease. P = 0.001

(last observation carried forward [LOCF]). (B) Percentage changes (%L'.) from baseline in GM hs-

CRP over time (modified intent-to-treat population; LOCF). *p = 0.008 versus 80 mg; tp < 0.001

versus 80 mg (2-tailed Mann-Whitney U test). P values are for change or %Il from baseline between

groups.

LDL-C target of <2.59 mmol/L (<100 mg/dL)25 was group (Table III). The most common all-causality events

reached in 92.3% (95% CI, 87.2%-95.8%) of patients reported, with a global incidence >3 % in either the

who received atorvastatin 80 mg and 77.1 % (95% CI, 10- or 80-mg group, were chest pain (4.1 % and 3.5%,

70.0%-83.1 %) of those who received the 10-mg dose respectively), flulike symptoms (3.5% and 1.8%), ar-

(P < 0.001). The more stringent NCEP ATP III target of thralgia (3.5% and 1.2%), respiratory tract infection

<1.81 mmol/L «70 mg/dL)26 was reached in 81.1% (2.9% and 5.9%), myalgia (1.8% and 3.5%), vagini-

(95% CI, 74.3%-86.7%) of patients with the 80-mg tis (0% and 3.3%), and vulvovaginal disorder (0%

dose and 33.5% (95% CI, 26.5%-41.2%) with the and 3.3 %). The most common treatment-related

10-mg dose (P < 0.001). The percentage of patients in events reported, with a global incidence> 1% in either

whom an hs-CRP <2 mgIL14 was reached was signifi- the 10- or 80-mg group, were asthenia (1.8 % and

cantly higher in the 80-mg group than in the 10-mg 1.8%, respectively), increased CK (1.8% and 0.6%),

group (63.9% [95% CI, 56.2%-71.1%] vs 47.1% myalgia (1.2% and 2.4 %), constipation (1.2% and

[95% CI, 39.4%-54.8%]; P = 0.002). 1.8%), increased AST (0% and 1.2%), and insomnia

Overall, dual targets of hs-CRP <2 mg/L and LDL-C (0% and 1.2%). The majority of events were of mild

<1.81 mmol/L «70 mg/dL) were reached in 13.5% to moderate intensity, with severe adverse events re-

(95% CI, 8.8%-19.6%) and 55.6% (95% CI,47.8%- ported in 1.2% of patients in both groups (1 patient

63.3%) of patients in the 10- and 80-mg groups, re- each: myalgia, dyspepsia, liver damage, and increased

spectively (P < 0.001). CK). Overall, 2.6% of patients discontinued atorva-

statin use due to treatment-related adverse events

Tolerability (5 patients: asthenia and/or myalgia; 1 patient each:

The prevalences of treatment-related adverse events leg cramps, liver damage, dyspepsia, increased ALT).

were 8.2% in the 10-mg group and 11.8% in the 80-mg Treatment-related adverse events involving the mus-

2304 Volume 30 Number 12

J. Bonnet et al.

___ Atorvastatln 10 mg (n ~ 170)

A B • Atorvastatln 80 mg (n ~ 169)

4 1.5

••

3

::J' ::J'

........ ........ 1.0

0 0

E E

~

E 2 • ~

E

U

~

0

--.J

• U

~

0 0.5

I

o h o h

o 2 4 6 8 10 12 14 16 18 20 22 24 26 LOCF o 2 4 6 8 10 12 14 16 18 20 22 24 26 LOCF

Study Week Study Week

C D

6 3

::J'

........

4 • ::J' 2

........

0

E 3

• 0

E •

E E

~

~ 2

~

lJ

f-

•

o h o h

o 2 4 6 8 10 12 14 16 18 20 22 24 26 LOCF o 2 4 6 8 10 12 14 16 18 20 22 24 26 LOCF

Study Week Study Week

Figure 3. Mean lipid concentrations over 26-week treatment with atorvastatin 10 or 80 mg in patients with

stable coronary artery disease. (A) Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) (P < 0.001).

(B) High-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) (P = 0.01). (C) Total cholesterol (TC) (P < 0.001).

(D) Triglycerides (TG) (P < 0.001). P values are for percentage change from baseline between the

groups (last observation carried forward [LOCF]) and were calculated using the t test.

(continued)

culoskeletal system occurred in 3.5% of patients. The SO-mg groups, respectively (Table III). There was 1 case of

most common adverse event involving the musculo- CK >10 x ULN in each treatment group (0.6% overall).

skeletal system was myalgia (1.2 % and 2.4 % with the Two serious adverse events were reported by the

10- and SO-mg doses, respectively). investigator as treatment related: acute hepatitis in the

The prevalences of any increase in AST/ALT >3 x up- 10-mg group and intrahepatic cholestasis in the SO-mg

per limit of normal (ULN) from a normal baseline value, group, in 2 patients with multiple comorbidities. Two

regardless of causality, were 0% and 1.S% in the 10- and deaths occurred during the study, both in the atorva-

December 2008 2305

Clinical Therapeutics

___ Atorvastatln 10 mg (n ~ 170)

E F • Atorvastatln 80 mg (n ~ 169)

6 6

5 5

::J'

4 • "-

0

E

E

4

::J'

"-

0

3

• ~

l{ 3

E

E •

l:fY

0...

<{

2

--.J

0

:::n:

2 •

Z

0 h 0 h

0 2 4 6 8 10 12 14 16 1820222426 LOCF 0 2 4 6 8 10121416 1820222426 LOCF

Study Week Study Week

G

6

0

.;:;

ro 4

0:::

U

3

•

~

0

I

•

U 2

f-

o h

o 2 4 6 8 10 12 14 16 18 20 22 24 26 LOCF

Study Week

Figure 3 (continued). Mean lipid concentrations over 26-week treatment with atorvastatin 10 or 80 mg in pa-

tients with stable coronary artery disease. (E) Apolipoprotein B (apoB) (P < 0.001). (F) Non-HDL-C

(P < 0.001). (G) TC/HDL-C ratio (P < 0.001) (modified intent-to-treat population [LOCF]). Pvalues are

for percentage change from baseline between the groups (LOCF) and were calculated using the t test.

statin SO-mg group (1, myocardial infarction; 1, sud- rosisY It has been suggested that CRP is not only a

den death), neither of which was deemed treatment prognostic indicator of CAD risk but also may be caus-

related by the investigator. ally involved in the atherothrombotic process and hence

could be considered a direct therapeutic target. 4 CRP

DISCUSSION can be detected within atherosclerotic lesions,28 and al-

Plasma hs-CRP concentration is a biochemical marker though not apparently directly atherogenic in rodent

of inflammation in patients with established atheroscle- models,4 CRP may have prothrombotic effects. 29 ,30

2306 Volume 30 Number 12

J. Bonnet et al.

D Atorvastatln 10 mg (n - 170)

D Atorvastatl n 80 mg (n - 169)

1st Tertde 2nd Tertde 3rd Tertde

30

10

I I I

CL

0:::

-10 L - L -

l(

Vl

...c -30

c * t - -

- -

-<I

Cf2, -

-50 '-----

-70

-90

+

Figure 4. Percentage changes (%L'.) from baseline (95% CI) in geometric mean high-sensitivity C-reactive pro-

tein (hs-CRP) concentrations over 26-week treatment with atorvastatin 10 or 80 mg in patients with

stable coronary artery disease, by baseline hs-CRP tertile (modified intent-to-treat population, last

observation carried forward). First tertile = hs-CRP <2.3 mg/L; 2nd tertile = 2.3-3.9 mg/L; 3rd ter-

tile = >3.9 mg/L. *p < 0.001 versus 80 mg; tp < 0.015 versus 80 mg.

However, recent studies have not found a relation- not be enough to alter CAD risk, which might explain

ship between genetic variants related to hs-CRP con- the lack of association between the majority of com-

centrations and CAD risk. 31,32 An analysis of associa- mon haplotypes in the CRP gene and risk for CAD. 32

tions between 3 genetic polymorphisms (-717C>T, The PROVE IT-TIMI 22 tria1 9 found improved

rs2794521; +1059G>C, rs1800947; +1444C>T, outcomes with more aggressive treatment (atorvastat-

rsl130864) at the CRP locus and related haplotypes in 80 mg compared with pravastatin 40 mg).14 Signifi-

in 3252 patients with ACS31 found that while some cantly lower event rates were observed in patients

genetic variants were associated with circulating CRP, with lower (<2 mg/L) versus higher (>2 mg/L) hs-CRP

none were consistently associated with the prevalence concentrations at all achieved LDL-C concentrations

of angiographic CAD. Similarly, case-control studies (2.8 vs 3.9 events per 100 person-years; P = 0.006).14

in 51,051 patients, of whom 515 had CAD events, In fact, the lowest event rate (1.9 events per 100 person-

found that 2 of the 5 common CRP haplotypes were years; P < 0.001) was observed in patients achieving

associated with significantly lower CRP levels, and both an LDL-C target <1.81 mmol/L «70 mg/dL) and

haplotype 4 was associated with significantly lower an hs-CRP target <2 mg/L. The A to Z trial,15 which

CRP levels and an elevated risk for CAD. 32 The other compared intensive and moderate treatment with sim-

haplotypes were not associated with CAD. This find- vastatin (80 vs 20 mg), did not achieve the prespeci-

ing was not unexpected given that the identified ge- fied primary end point (composite of cardiovascular-

netic polymorphisms predict a small proportion of related death, nonfatal myocardial infarction,

variation in hs-CRP, and most of the variation has not readmission for ACS, and stroke); event rates were

been explained. 31 ,32 The apparent influence on base- 14.4% in the 80-mg group and 16.7% in the simva-

line CRP levels caused by CRP polymorphisms may statin 20-mg group at 6- to 24-month follow-up (HR,

December 2008 2307

Clinical Therapeutics

Table II. Analysis of correlations between concentrations and changes from baseline (Ll) in hs-CRP and lipid

parameters after 26 weeks of treatment with atorvastatin 10 or 80 mg/d in patients with stable

coronary artery disease. (Spearman correlation coefficients were used.)

Atorvastatin 10 mg Atorvastatin 80 mg

(n = 170) (n = 169)

Concentration 6 Concentration 6

Lipid

Parameter r2 p r2 p r2 p r2 p

LDL-C 0.0324 0.016 0.0036 0.47 0.0484 0.005 0.0484 0.003

HDL-C 0.0169 0.080 0.0100 0.19 0.0004 0.770 0.0144 0.110

TG 0.0025 0.520 0.0081 0.24 0.0009 0.700 0.0004 0.820

LDL-C ~ low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; HDL-C ~ high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; TG ~ tnglycendes.

0.89; 95% CI, 0.76-1.04; P = NS). In a post hoc those with hs-CRP 1 to 3 mg/L or hs-CRP <1 mg/L

analysis of results from the A to Z trial, hs-CRP con- (6.1 % vs 3.7% vs 1.6%; P < 0.001). Moreover, in

centrations that were strongly and independently as- contrast with the significant early coronary event re-

sociated with long-term survival were reached at duction found in PROVE IT-TIMI 22, the A to Z trial

30 days and 4 monthsY After adjustment for other did not find any significant between-group differences

risk factors, patients with hs-CRP >3 mg/L at 30 days in the primary end point during the first 4 months.

had significantly higher 2-year mortality rates than Despite a similar LDL-C concentration reached early

D Atorvastatln 10 mg (n - 170)

D Atorvastatln 80 mg(n -169)

100

80-

Vl

'-'

c 60-

.;:;

Q)

n:I

CL

4-

o 40-

Cf2.

20-

+

o-+-----'--------'---L.---,----I---'-------'--------'------,I

LDL-C <2.59 mmoljL LDL-C <1.81 mmoljL

«100 mgjdL) «70 mgjdL)

Figure 5. Proportions (95% CI) of patients achieving National Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment

Panel III low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) targets after 26-week treatment with atorvastatin

10 or 80 mg in patients with stable coronary artery disease (modified intent-to-treat population).

2308 Volume 30 Number 12

J. Bonnet et al.

Table III. Tolerability with atorvastatin 10 and 80 mg/d In patients with stable coronary

artery disease. Values are no. (%) of patients.

Atorvastatin Atorvastatin

10 mg 80 mg

Parameter (n = 170) (n = 170)

All causality

~1 AE 85 (50.0) 82 (48.2)

~1 Musculoskeletal AEs 17(10.0) 12 (7.1)

AST or ALT >3 x ULN 0 3 (1.8)

CK >10 x ULN 1 (0.6) 1 (0.6)

Treatment-related AEs

~1 AE 14 (8.2) 20 (11.8)

~1 Musculoskeletal AE 6 (3.5) 6 (3.5)

Discontinued due to AE 3 (1.8) 6 (3.5)

AE ~ adverse event; AST ~ aspartate aminotransferase; ALT ~ alanine aminotransferase; ULN ~ upper

limit of normal; CK ~ creatinine kinase.

after treatment (1.61 mmol/L [62 mg/dL] at 120 days) and evidence of low-grade systemic inflammation. The

in the 2 trials, the hs-CRP reduction versus placebo population in the present study was similar to that in

was >2-fold greater in PROVE IT-TIMI 22 13 com- the TNT (Treating to New Targets) study,35 which in-

pared with that achieved in A to Z (38% vs 17%),15 cluded patients with clinically evident CAD and

which is possibly relevant to the difference in out- slightly elevated LDL-C (<3.4 mmol/L [130 mg/dL])

comes between the 2 clinical trials. and found a 22% relative risk reduction (HR, 0.78;

The REVERSAL (Reversal of Atherosclerosis with 95% CI, 0.69-0.89; P < 0.001) with atorvastatin

Aggressive Lipid Lowering) triaP3 found reduced ath- 80 mg/d compared with atorvastatin 10 mg/d.

erosclerosis progression rates (percentage change in This CAP study found that reductions in hs-CRP

atheroma volume) after intensive (atorvastatin 80 mg/d, were dose dependent. The maximum change in hs-CRP,

-0.4%; 95% CI, -2.4% to 1.5%), compared with mod- -25%, was achieved at week 5 in the 10-mg group.

erate (pravastatin 40 mg/d, 2.7%; 95% CI,0.24-4.67; In contrast, the change in hs-CRP at 5 weeks in the

P = NS), statin treatment in 502 patients with stable 80-mg group was -36.4%; this concentration de-

CAD after 18 months using intravascular ultrasonog- creased progressively over the 26-week study period,

raphy. In REVERSAL, the reduction in atherosclerosis to a total change of -57.1 %. These data are consistent

progression was significantly related to greater reduc- with the dose-dependent reductions, -27% in the

tions in the concentrations of lipoproteins and hs- 10-mg and -43% in the 80-mg group, in hs-CRP con-

CRP (1" = 0.09; P = 0.04).34 The authors attributed this centrations previously found with 12 weeks of treat-

additional benefit in part to the greater reduction in ment with atorvastatin 10, 20, 40, and 80 mg/d in

hs-CRP in the atorvastatin group. 628 patients with or without CAD in an RCT. 36 Simi-

Taken together, the results from PROVE IT-TIMI lar results were reported in an RCT in 182 patients

22, A to Z, and REVERSAL suggest that therapeutic with type 2 diabetes, in whom the median CRP con-

interventions to substantially lower CRP may have centrations were reduced by 15% and 47%, respec-

ameliorative effects on coronary events and mortality. tively, with 30 weeks of treatment with atorvastatin

We investigated the effects of low- versus high-dose 10 and 80 mg/d (P < 0.001).31 These findings suggest

atorvastatin treatment on LDL-C in a population of that long-term treatment with a high-dose statin is nec-

patients with stable CAD, a normal-range lipid profile, essary to achieve maximum antiinflammatory effect.

December 2008 2309

Clinical Therapeutics

A post hoc analysis of data from the present study hypercholesterolemia; thus, findings may not be ap-

found that the dual targets of LDL-C <1.81 mmoUL plicable to the general population. A single hs-CRP

«70 mg/dL) and hs-CRP <2.0 mg/L were reached sample was taken at each time point, while the mean

in a significantly greater proportion of patients with of 2 samples taken 2 weeks apart would have been

atorvastatin 80 mg compared with less intensive treat- preferable to account for variability in measure-

ment with 10 mg (55.6% vs 13.5%; P < 0.001). How- ments. 43 In addition, this study was not designed to

ever, the decrease in hs-CRP was largely independent investigate the impact of lowering hs-CRP concentra-

of baseline LDL-C and change in LDL-C and totally tions on the incidence of coronary events.

independent of changes in HDL-C and TG, regardless It remains possible that underlying inflammatory pro-

of dose. We report herein the correlation between the cesses that predict coronary events cannot be captured

magnitude of changes in hs-CRP and LDL-C, which solely by variation in the CRP gene. The CAP study con-

reached statistical significance with the 80-mg dose, tributes to the growing body of evidence supporting the

but not the 10-mg dose, of atorvastatin (80 mg, r2 = benefit of high-dose statin treatment in patients at high

0.0484; P = 0.003; 10 mg, r2 = 0.0036; P = NS). This risk, through LDL-C lowering and vascular benefits (hs-

finding was similar to that from the PROVE IT-TIMI CRP reduction), with the aim of reducing cardiovascular-

22 trial 14 with atorvastatin 80 mg/d or pravastatin related mortality and morbidity in this population.

40 mg/d (r = 0.16; P < 0.001). The greater correlation

between hs-CRP and LDL-C found in PROVE IT- CONCLUSIONS

TIMI 22 compared with the present trial may be ac- In this population of patients with stable CAD, normal-

counted for by the comparatively smaller sample size, range lipid profiles, and evidence of chronic low-grade

large interindividual variability, different patient popu- systemic inflammation, the effects of atorvastatin on

lation (eg, ACS), or perhaps site interaction in the changes in hs-CRP were dose dependent, with the

present trial. However, because <3 % of the variation high dose (80 mg) being associated with significantly

in achieved hs-CRP concentrations was explained by greater reductions in hs-CRP concentrations. Patients

the variation in achieved LDL-C in PROVE IT-TIMI in highest tertile of baseline hs-CRP experienced sig-

22, this small difference may not be clinically relevant. nificantly greater reductions in hs-CRP. Both low- and

Thus, statin-mediated reductions in hs-CRP may be high-dose atorvastatin were associated with a signifi-

mediated by independent antiinflammatory effects of cant and progressive decline in hs-CRP, largely inde-

inhibition of 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A pendent of changes in LDL-C, HDL-C, and TG. Ator-

reductase. 1O ,34,38--41 However, correlations of changes vastatin 80 mg was generally well tolerated over the

in LDL-C and hs-CRP in individuals are decreased by study period.

their measurement variability. A meta-analysis of

23 studies with 57 patients treated with a variety of ACKNOWLEDGM ENTS

statins (atorvastatin, cerivastatin, lovastatin, pravasta- This research and its publication were funded by

tin, rosuvastatin, or simvastatin), nonstatin drugs, and Pfizer France and Pfizer Canada.

nondrug therapies found a strong correlation between We are grateful to the patients, local investigators,

the changes in LDL-C and hs-CRP (r = 0.80; and study coordinators and other study collabora-

P < 0.001), and concluded that statin therapies had no tors who made completion of the study possible.

significant effect on hs-CRP after adjustment for the The study was designed and conducted by the CAP

change in LDL-C. 42 steering committee members in collaboration with

The results from this CAP study suggest that the Pfizer France and Pfizer Canada. The authors thank

80-mg dose of atorvastatin was generally well tolerat- Pauline Lavigne, MSc (CMED, Toronto, Ontario,

ed, with severe adverse events being reported in 2 pa- Canada), for her assistance with preparation of the

tients, as a starting dose in patients with stable CAD manuscript.

and low baseline LDL-C concentrations. The authors had full access to the data and take

There were a number of limitations in the present responsibility for its integrity. All authors have read

study. The population was restricted to patients with and agree to the manuscript as written.

at least moderately elevated hs-CRP concentrations The CAP Investigators included, from Canada:

at baseline and did not include patients with severe P.T.S. Ma (Calgary, Alberta), A. Opgenorth (Edmon-

2310 Volume 30 Number 12

J. Bonnet et al.

ton, Alberta), J. Frohlich (Vancouver, British Colum- and Wyeth Pharmaceuticals. He is partlCIpating in

bia), G. Hoag (Victoria, British Columbia), D. Mymin clinical trials for Pfizer, Merck, Pharmena, sanofi-

(Winnipeg, Manitoba), E. Dr (Halifax, Nova Scotia), aventis, and Takeda and is a member of the speakers'

D. Spence (London, Ontario), J.Y.M. Cha (Oshawa, bureau of the International Atherosclerosis Society.

Ontario), R. McPherson (Ottawa, Ontario), M.J.

O'Mahony (Sarnia, Ontario), L.A. Leiter (Toronto, REFERENCES

Ontario), L.C.H. Yao (Weston, Ontario), D. Gaudet 1. Tedgu I A, Mallat Z. Cytokl nes In atherosclerosIs: Patho-

(Chicoutimi, Quebec), R. Habib (Chomedey, Laval, genic and regulatory pathways. Physiol Rev. 2006;86:515-

Quebec), c. Constance, J. Davignon, M.A. Lavoie, R. 581.

2. Berk BC, Weintraub WS, Alexander RW. Elevation of

Nadeau (Montreal, Quebec), c. Gagne (Sainte-Foy,

C-reactive protein In "active" coronary artery disease. Am

Quebec), P. Perron (Sherbrooke, Quebec), and T. Wil-

J Cardlol. 1990;65:168-172.

son (Saskatoon, Saskatchewan); from the Czech Re-

3. Lluzzo G, Biasucci LM, GalilmoreJR, et al. The prognostic

public: L. Berka (Jindrichuv Hradec), J. Bultas, M. value of C-reactive protein and serum amyloid a protein In

Herold, D. Zemanek (Prague), and V. Chaloupka (Br- severe unstable angina. N EnglJ Med. 1994;331 :417-424.

no-Bohunice); from France: P. Amarenco (Paris), P. 4. Verma S, DevaraJ S, Jlalal I. Is C-reactive protein an inno-

Assayag (Ie Kremlin Bicetre Cedex), M. Barboteu cent bystander or proatherogenlc culprit? C-reactive pro-

(Evecquemont), J. Bonnet (Pessac Cedex), J. Boschat tein promotes atherothrombosls. Circulation. 2006;113:

(Brest); B. Citron (Clermont-ferrand), J.M. Davy 2135-2150.

(Montpellier); E. Decoulx (Tourcoing), B. Doucet 5. Wdlerson JT, Rldker PM. Inflammation as a cardiovascu-

(Chambery),J. Emmerich (Paris Cedex), D. Flammang lar nsk factor. Circulation. 2004;109(Suppl 1):112-111 O.

(Saint Michel), F. Funck (Pontoise), P. Guenoun (Thi- 6. Venugopal SK, DevaraJ S,Jlalall. Effect of C-reactive pro-

tein on vascular cells: EVidence for a prolnflammatory,

onville), T. Haftel (Roubaix), J.c. Kahn (Poissy), K.

proatherogenlc role. Curr Opln Nephrol Hypertens. 2005; 14:

Khalife (Metz Cedex), P. Kohan (Nancy), J.M.

33-37.

Lablanche (Lille), J. Lipiecki (Clermont-ferrand), M.

7. Jlalal I, DevaraJ S, Venugopal SK. C-reactive protein: Risk

Martelet (Langres), T. Olive (Gap), J.P. Ollivier (Paris marker or mediator In atherothrombosls? Hypertension.

Cedex), E. Perrier (Clamart), J. Puel (Toulouse), J. 2004;44:6-11.

Seoud (Creil), P. Voiriot (Vandoeuvre Les Nancy), and 8. Balgent C, Keech A, Kearney PM, et ai, for the Cholesterol

J.E. Wolf (Dijon); from Poland: R. Bubinski (Bel- Treatment Tnallsts' (CTT) Collaborators. Efficacy and

chatow), R. Filipczak (Rawa Mazowiecka), K. Jawor- safety of cholesterol-Iowenng treatment: Prospective

ska (Torun),A. Kleinrok (Zamosc), K. Loboz-Grudzien meta-analysIs of data from 90,056 participants In 14 ran-

(Wroclaw), and M. Piepiorka (Gdynia); from Roma- domlsed tnals of statlns [published corrections appear In

nia: M. Cinteza (Bucuresti), D. Dimulescu (Bucharest), Lancet. 2005;366:1358; Lancet. 2008;371 :2084]. Lancet.

and M. Vintila (Bucuresti); from Russia: N. Ahmedzha- 2005;366:1267-1278.

nov (Moscow) and Y. Lopatin (Volgograd); from Slova- 9. Downs JR, Clearfield M, Wels S, et al. Pnmary prevention

kia: A. Dukat, S. Filipova, and J. Murin (Bratislava). of acute coronary events with lovastatln In men and

women with average cholesterol levels: Results of AF-

Dr. McPherson has received speaker and consulta-

CAPS/TexCAPS. Air Force/Texas Coronary AtherosclerosIs

tion fees from Pfizer Canada and has served on advi-

Prevention Study.JAMA. 1998;279:1615-1622.

sory boards and received honoraria for Continuing

10. Rldker PM, Rlfal N, Clearfield M, et ai, for the Air Force/

Medical Education from AstraZeneca Canada, Glaxo-

Texas Coronary AtherosclerosIs Prevention Study Investi-

SmithKline, Merck Frosst Canada, Oryx Pharmaceu-

gators. Measurement of C-reactive protein for the target-

ticals, and Roche Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Davignon has Ing of statln therapy In the pnmary prevention of acute

received research grant support from AstraZeneca, coronary events. N EnglJ Med. 2001 ;344: 1959-1965.

Pfizer Canada, and Merck-Frosst Canada, and he is or 11. Sacks FM, Pfeffer MA, Moye LA, et ai, for the Cholesterol

has been a consultant or scientific advisor for Astra- and Recurrent Events Tnal Investigators. The effect of

Zeneca, Bayer, Bristol-Meyers Squibb, CardAlpha, pravastatln on coronary events after myocardial infarc-

Cortia (Pharmena), Esperion, Genzyme Corporation, tion In patients with average cholesterol levels. N Engl

Fournier/Solvay, Genfit, LifeCycle Pharma, McCain, J Med. 1996;335:1001-1009.

Merck, Merck/Frosst Schering, Merck-Schering, No- 12. Rldker PM, Rlfal N, Pfeffer MA, et ai, for the Cholesterol

vartis, Oryx, Pfizer Sankyo, sanofi-aventis, Takeda, and Recurrent Events (CARE) Investigators. Long-term ef-

December 2008 2311

Clinical Therapeutics

fects of pravastatln on plasma con- Reduction with Aggressive Choles- 27. LJbby P, Rldker PM. Inflammation and

centration of C-reactive protein. Cir- terol Lowenng Study Investigators. atherosclerosIs: Role of C-reactive

culatlon.1999;100:230-235. High-dose atorvastatl n en hances protein In nsk assessment. AmJ Med.

13. Cannon CP, Braunwald E, McCabe the decline In Inflammatory mark- 2004;116(Suppl 6A):9S-16S.

CH, et ai, for the Pravastatln or ers In patients with acute coronary 28. Torzewskl J, Torzewskl M, Bowyer

Atorvastatln Evaluation and Infec- syndromes In the M IRACL study. DE, et al. C-reactive protein fre-

tion Therapy-ThrombolysIs In Myo- Circulation. 2003;108:1560-1566. quently colocallzes with the termi-

cardlallnfarctlon 22 (PROVE IT-TIM I 20. Meredith KG, Horne BD, Pearson nal complement complex In the in-

22) Investigators. Intensive versus RR, et al. Companson of effects of tima of early atherosclerotic lesions

moderate lipid lowenng with statlns high (80 mg) versus low (20 mg) of human coronary artenes. Arteno-

after acute coronary syndromes dose of slmvastatln on C-reactive seier Thromb Vasc Bioi. 1998; 18:

[published correction appears In protein and lipoproteins In patients 1386-1392.

N EnglJ Med. 2006;354:778]. N Engl with anglographlc eVidence of coro- 29. Yaron G, Bnll A, Dashevsky 0, et al.

J Med. 2004;350: 1495-1504. naryartenal narrowing. AmJ Cardlol. C-reactive protein promotes platelet

14. Rldker PM, Cannon CP, Morrow D, 2007;99: 149-153. adhesion to endothelial cells: A po-

et ai, for the Pravastatln or Ator- 21. SCinca BM, Morrow DA. Is C-reactive tential pathway In atherothrombosls.

vastatln Evaluation and Infection protein an Innocent bystander or BrJ Haematol. 2006;134:426-431.

Therapy-ThrombolysIs In Myocardial proatherogenlc culpnt? The verdict 30. Song CJ, Nakagoml A, Chandar S,

Infarction 22 (PROVE IT-TIM I 22) IS still out. Circulation. 2006; 113: et al. C-reactive protein contnbutes

Investigators. C-reactive protein lev- 2128-2134; discussion 2151. to the hypercoagulable state In coro-

els and outcomes after statln thera- 22. World Medical Association Decla- nary artery disease. J Thromb Hae-

py. N En~J Med. 2005;352:20-28. ration of Helsinki: Ethical pnnclples most. 2006;4:98-106.

15. de Lemos JA, Blazing MA, WIVIOtt for medical research involving hu- 31. Grammer TB, Marz W, Renner

SD, et ai, for the A to Z Investiga- man subjects. JAMA. 2000;284: W, et al. C-reactive protein geno-

tors. Early intensive vs a delayed 3043-3045. types associated with circulating C-

conservative slmvastatln strategy In 23. Sachs L. Applted StatistiCS: A Hand- reactive protein but not with anglo-

patients with acute coronary syn- book of Techniques. 2nd ed. New graphic coronary artery disease:

dromes: Phase Z of the A to Z tnal. York, NY: Spnnger-Verlag; 1984. The LURIC study [published online

JAMA. 2004;292:1307-1316. 24. Winer BJ, Brown DR, Michels KM. ahead of pnnt May 21, 2008]. Eur

16. WIVIOtt SD, de Lemos JA, Cannon CP, Statistical PnnClples In Expenmental De- Heart}.

et al. A tale of two tnals: A com- sign. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw- 32. Pal JK, Mukamal KJ, Rexrode KM,

panson of the post-acute coronary Hill; 1991. Rlmm EB. C-reactive protein (CRP)

syndrome llpld-lowenng tnals A to 25. The Expert Panel on Detection, Evalu- gene polymorph Isms, CRP levels,

Z and PROVE IT-TIMI 22. Circula- ation, and Treatment of High Blood and nsk of incident coronary heart

tlon.2006;113:1406-1414. Cholesterol In Adults. Executive disease In two nested case-control

17. Morrow DA, de Lemos JA, Sabatine summary of The Third Report of studies. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e1395.

MS, et al. Clinical relevance of C- the National Cholesterol Education 33. Nissen SE, Tuzcu EM, Schoenhagen P,

reactive protein dunng follow-up of Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on et ai, for the REVERSAL Investiga-

patients with acute coronary syn- Detection, Evaluation, and Treat- tors. Effect of intensive compared

dromes In the Aggrastat-to-Zocor ment of High Blood Cholesterol In with moderate Iipld-lowenng therapy

Tnal. Circulation. 2006;114:281-288. Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III). on progression of coronary athero-

18. Schwartz GG, Olsson AG, Ezekow- JAMA. 2001 ;285:2486-2497. sclerosIs: A randomized controlled

Itz MD, et ai, for the Myocardial 26. Grundy SM, Cleeman JI, Merz CN, et tnal.JAMA. 2004;291:1071-1080.

Ischemia Reduction with Aggressive ai, for the National Heart, Lung, and 34. Nissen SE, Tuzcu EM, Schoenhagen P,

Cholesterol Lowenng (MIRACL) Blood Institute; the Amencan Col- et ai, for the Reversal of Atheroscle-

Study Investigators. Effects of ator- lege of Cardiology Foundation; and roSIS with Aggressive Lipid Lowenng

vastatln on early recurrent Ischemic the Amencan Heart Association. Im- (REVERSAL) Investigators. Statl n

events In acute coronary syndromes: plications of recent clinical tnals for therapy, LDL cholesterol, C-reactive

The MIRACL study: A randomized the National Cholesterol Education protein, and coronary artery dis-

controlled tnal. JAMA. 2001 ;285: Program Adult Treatment Panel III ease. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:29-

1711-1718. gUidelines [published correction ap- 38.

19. Klnlay S, Schwartz GG, Olsson AG, pears In Circulation. 2004;110:763]. 35. LaRosaJC, Grundy SM, Waters DD,

et ai, for the Myocardial Ischemia Circulation. 2004;110:227-239. et ai, forthe Treating to New Targets

2312 Volume 30 Number 12

J. Bonnet et al.

(TNT) Investigators. Intensive lipid ease Control and Prevention and A statement for health care profes-

lowenng with atorvastatln In pa- the Amencan Heart Association. sionals from the Centers for Disease

tients with stable coronary disease. Markers of inflammation and car- Control and Prevention and the

N Englj Med. 2005;352:1425-1435. diovascular disease: Application to Amencan Heart Association. Circu-

36. Ballantyne CM, Houn J, Notarbar- clinical and public health practice: latlon.2003;107:499-511.

tolo A, et ai, for the Ezetlmlbe Study

Group. Effect of ezetlmlbe co-

administered with atorvastatln In

628 patients with pnmary hyper-

cholesterolemia: A prospective, ran-

domized, double-blind trial. Circula-

tion. 2003; 107:2409-2415.

37. van de Ree MA, HUisman MV, Pnn-

cen HM, et ai, for the DALI-Study

Group. Strong decrease of high sen-

SitiVity C-reactive protein with hlgh-

dose atorvastatln In patients with

type 2 diabetes mellitus. Atheroscle-

roSIS. 2003; 166:129-135.

38. Rldker PM, Rlfal N, Lowenthal SP.

Rapid reduction In C-reactive pro-

tein with cenvastatln among 785 pa-

tients with pnmary hypercholester-

olemia. Circulation. 2001;103:1191-

1193.

39. Klnlay S, Timms T, Clark M, et ai,

for the Vascular BasIs Study Group.

Companson of effect of intensive

lipid lowenng with atorvastatln to

less Intensive lowenng with Iova-

statln on C-reactive protein In pa-

tients with stable angina pectons

and inducible myocardial Ischemia.

Am} Cardlol. 2002;89:1205-1207.

40. Jlalal I, Stein D, Balls D, et al. Effect

of hydroxymethyl glutaryl coenzyme

A reductase Inhlbltortherapy on high

sensitive C-reactive protein levels.

CirculatIOn. 2001;103:1933-1935.

41. PlengeJK, HernandezTL, Well KM,

et al. Slmvastatln lowers C-reactive

protein within 14 days: An effect

Independent of low-density lipo-

protein cholesterol reduction. Circu-

latlon.2002;106:1447-1452.

42. Klnlay S. Low-density Ilpoproteln-

dependent and -Independent e~

fects of cholesterol-Iowenng thera-

pies on C-reactive protein: A meta-

analysIs.} Am Call Cardlol. 2007;49: Address correspondence to: Jean Davignon, MD, Hyperlipidemia and

2003-2009. Atherosclerosis Research Group, Clinical Research Institute of Montreal

43. Pearson TA, Mensah GA, Alexander (IRCM), 110 Pine Avenue West, Montreal, Quebec, Canada H2W lR7.

RW, et ai, for the Centers for Dls- E-mail: davignj@ircm.qc.ca

December 2008 2313

You might also like

- CRESTOR Launch Presentation January 2011Document40 pagesCRESTOR Launch Presentation January 2011Chikezie Onwukwe67% (3)

- 10-11 - Anti-Hyperlipidemic Drugs (Summary SAQ and MCQS)Document6 pages10-11 - Anti-Hyperlipidemic Drugs (Summary SAQ and MCQS)Purvak MahajanNo ratings yet

- Lipitor WorksheetDocument2 pagesLipitor WorksheetMichael Kuzbyt100% (4)

- AURORA: Is There A Role For Statin Therapy in Dialysis Patients?Document4 pagesAURORA: Is There A Role For Statin Therapy in Dialysis Patients?Ravan WidiNo ratings yet

- CLC 4960230910Document7 pagesCLC 4960230910walnut21No ratings yet

- LDL Cholesterol Reduction and Cardiovascular Outcomes with High-Intensity Statin TherapyDocument7 pagesLDL Cholesterol Reduction and Cardiovascular Outcomes with High-Intensity Statin TherapyWanda Novia P SNo ratings yet

- Effects of Niacin Combination Therapy With Statin or Bile-Acid Resin On Lipoproteins and Cardiovascular DiseaseDocument10 pagesEffects of Niacin Combination Therapy With Statin or Bile-Acid Resin On Lipoproteins and Cardiovascular Diseaselina budiartiNo ratings yet

- Rosuvastatin Reduces Coronary Plaque in ASTEROID TrialDocument12 pagesRosuvastatin Reduces Coronary Plaque in ASTEROID TrialSharmil IyapillaiNo ratings yet

- Anti-Inflammatory and Metabolic Effects of Candesartan in Hypertensive PatientsDocument5 pagesAnti-Inflammatory and Metabolic Effects of Candesartan in Hypertensive PatientsBarbara Sakura RiawanNo ratings yet

- AtorvastatinDocument27 pagesAtorvastatinBolgam PradeepNo ratings yet

- Jurnal 4 WordDocument20 pagesJurnal 4 WordSri MaryatiNo ratings yet

- TRT CanderinDocument45 pagesTRT CanderinAngieda SoepartoNo ratings yet

- LupusDocument8 pagesLupusFerdinand YuzonNo ratings yet

- Research Journal of Pharmaceutical, Biological and Chemical SciencesDocument9 pagesResearch Journal of Pharmaceutical, Biological and Chemical SciencesMuhammad ZubaidiNo ratings yet

- AMADEO Full PaperDocument6 pagesAMADEO Full PaperAnggraeni PermatasariNo ratings yet

- Long-Term Effect of Dual Renin-Angiotensin BlockadeDocument7 pagesLong-Term Effect of Dual Renin-Angiotensin BlockadechondroNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Ebm Kedkel SashaDocument14 pagesJurnal Ebm Kedkel SashaSasha Fatima ZahraNo ratings yet

- Objective:: BackgroundDocument23 pagesObjective:: BackgroundJanine DimaangayNo ratings yet

- Blood Pressure and Cholesterol Lowering in Persons Without Cardiovascular DiseaseDocument46 pagesBlood Pressure and Cholesterol Lowering in Persons Without Cardiovascular DiseaseJirran CabatinganNo ratings yet

- System Journal of Renin-Angiotensin-AldosteroneDocument6 pagesSystem Journal of Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosteronerizqi_cepiNo ratings yet

- Comparison of The Efficacy of Rosuvastatin Versus Atorvastatin, Simvastatin, and Pravastatin in Achieving Lipid Goals: Results From The STELLAR TrialDocument11 pagesComparison of The Efficacy of Rosuvastatin Versus Atorvastatin, Simvastatin, and Pravastatin in Achieving Lipid Goals: Results From The STELLAR Trialamit khanNo ratings yet

- ARB Delays Microalbuminuria in DiabetesDocument3 pagesARB Delays Microalbuminuria in DiabetesCésar EscalanteNo ratings yet

- Pharm 316 Case Presentation: Statins in The Golden Years - Statin For Primary Prevention in ElderlyDocument37 pagesPharm 316 Case Presentation: Statins in The Golden Years - Statin For Primary Prevention in ElderlyKevin JiaNo ratings yet

- Kim 2019Document14 pagesKim 2019Dianne GalangNo ratings yet

- Jupiter Trial: DR Sheeraz Alam DM Cardiology SR1 JNMCH, AmuDocument23 pagesJupiter Trial: DR Sheeraz Alam DM Cardiology SR1 JNMCH, AmuSheerazNo ratings yet

- Effectiveness and Safety of Low-Dose Pravastatin and Squalene, Alone and in Combination, in Elderly Patients With HypercholesterolemiaDocument6 pagesEffectiveness and Safety of Low-Dose Pravastatin and Squalene, Alone and in Combination, in Elderly Patients With HypercholesterolemiaeduardochocincoNo ratings yet

- Perhitungan RRDocument5 pagesPerhitungan RRMuh Witly FairussaflyNo ratings yet

- Catalano1992 PDFDocument6 pagesCatalano1992 PDFSepti Fadhilah SPNo ratings yet

- More intensive LDL cholesterol lowering reduces vascular risksDocument12 pagesMore intensive LDL cholesterol lowering reduces vascular risksStefania CristinaNo ratings yet

- Atorvastatin RaDocument2 pagesAtorvastatin RaNejra JonuzNo ratings yet

- Efficacy of Low-And Moderate-Intensity Statins For Achieving Low - Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol Targets in Thai Type 2 Diabetic PatientsDocument8 pagesEfficacy of Low-And Moderate-Intensity Statins For Achieving Low - Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol Targets in Thai Type 2 Diabetic Patientsnaufal12345No ratings yet

- Refludan® (Lepirudin (rDNA) For Injection) RX Only DescriptionDocument22 pagesRefludan® (Lepirudin (rDNA) For Injection) RX Only DescriptionDoctorMoodyNo ratings yet

- Metaanálisis Uso Hipolipemiantes. Mejor Evo 140,420 y Aliro 150Document45 pagesMetaanálisis Uso Hipolipemiantes. Mejor Evo 140,420 y Aliro 150Fernando DominguezNo ratings yet

- Publication CAP and PTBDocument9 pagesPublication CAP and PTBAvniApteNo ratings yet

- Effect of Candesartan Monotherapy On Lipid Metabolism in Patients With Hypertension: A Retrospective Longitudinal Survey Using Data From Electronic Medical RecordsDocument7 pagesEffect of Candesartan Monotherapy On Lipid Metabolism in Patients With Hypertension: A Retrospective Longitudinal Survey Using Data From Electronic Medical RecordsAldiKurosakiNo ratings yet

- FluidDocument190 pagesFluidAndrias OzNo ratings yet

- Ator Simvas OkDocument7 pagesAtor Simvas OkGatiNo ratings yet

- Original Article: Journal of Clinical Lipidology (2017)Document12 pagesOriginal Article: Journal of Clinical Lipidology (2017)IrhamNo ratings yet

- DiabegardDocument6 pagesDiabegardmlteenNo ratings yet

- The Effects of Malunggay Moringa Oleifera Leaves Capsule Supplements OnHigh Specificity C-Reactive Protein HSCRP and Hemoglobin A1c HgbA1cDocument10 pagesThe Effects of Malunggay Moringa Oleifera Leaves Capsule Supplements OnHigh Specificity C-Reactive Protein HSCRP and Hemoglobin A1c HgbA1cCatNo ratings yet

- Pi Is 1933287417302908Document11 pagesPi Is 1933287417302908Anonymous yptjlwJNo ratings yet

- Telmisartan For Treatment of Covid-19 Patients: An Open Multicenter Randomized Clinical TrialDocument4 pagesTelmisartan For Treatment of Covid-19 Patients: An Open Multicenter Randomized Clinical TrialTeam - MEDICALSERVICESNo ratings yet

- Comparative Study of Serum and Biliary Lipid Profile in Libyan Gallstone PatientsDocument54 pagesComparative Study of Serum and Biliary Lipid Profile in Libyan Gallstone PatientsJagannadha Rao PeelaNo ratings yet

- English JournalDocument4 pagesEnglish JournalRamya HarlistyaNo ratings yet

- European Journal of Preventive Cardiology-2016-Karlson-744-7 PDFDocument4 pagesEuropean Journal of Preventive Cardiology-2016-Karlson-744-7 PDFIrina Cabac-PogoreviciNo ratings yet

- AntioksidanDocument5 pagesAntioksidanRakasiwi GalihNo ratings yet

- Comparative Biological Data and Clinical Trial Design for CT-P10 and RTXDocument20 pagesComparative Biological Data and Clinical Trial Design for CT-P10 and RTXniajaplaniNo ratings yet

- Effect of Cinacalcet on Cardiovascular Outcomes in Dialysis PatientsDocument62 pagesEffect of Cinacalcet on Cardiovascular Outcomes in Dialysis PatientssantoshvelloreNo ratings yet

- AtorvastatinDocument3 pagesAtorvastatinheema valeraNo ratings yet

- Baseline Low-Density LipoproteinDocument9 pagesBaseline Low-Density LipoproteinjoNo ratings yet

- C Reaktive ProteinDocument4 pagesC Reaktive Proteinsinggih2008No ratings yet

- X. Tillin 2011 DT2Document6 pagesX. Tillin 2011 DT2Juan Carlos FloresNo ratings yet

- Roberto Fogari, MD Annalisa Zoppi, MD Amedeo Mugellini, MD Paola Preti, MD Maurizio Destro, MD Andrea Rinaldi, MD and Giuseppe Derosa, MDDocument15 pagesRoberto Fogari, MD Annalisa Zoppi, MD Amedeo Mugellini, MD Paola Preti, MD Maurizio Destro, MD Andrea Rinaldi, MD and Giuseppe Derosa, MDdini hanifaNo ratings yet

- Furtado 2016Document10 pagesFurtado 2016zzzzNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 0049384887903586 MainDocument8 pages1 s2.0 0049384887903586 Mainong251183No ratings yet

- To Compare Rosuvastatin With Atorvastatin in Terms of Mean Change in LDL C in Patient With Diabetes PDFDocument7 pagesTo Compare Rosuvastatin With Atorvastatin in Terms of Mean Change in LDL C in Patient With Diabetes PDFJez RarangNo ratings yet

- Influence of Triglycerides On Other Plasma Lipids in Middle-Aged Men Intended For Hypolipidaemic TreatmentDocument6 pagesInfluence of Triglycerides On Other Plasma Lipids in Middle-Aged Men Intended For Hypolipidaemic TreatmentPatrisia HallaNo ratings yet

- Allograft Outcomes After Simultaneous Pancreas Kidney Transplantation Comparing T1DM With Type 2 DMDocument6 pagesAllograft Outcomes After Simultaneous Pancreas Kidney Transplantation Comparing T1DM With Type 2 DMbjornwiinbladNo ratings yet

- Complementary and Alternative Medical Lab Testing Part 8: UrologyFrom EverandComplementary and Alternative Medical Lab Testing Part 8: UrologyRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (1)

- Complementary and Alternative Medical Lab Testing Part 6: Liver and GallbladderFrom EverandComplementary and Alternative Medical Lab Testing Part 6: Liver and GallbladderNo ratings yet

- Statin Intolerance Some Practical HintsDocument7 pagesStatin Intolerance Some Practical HintsTony Miguel Saba SabaNo ratings yet

- Lower Cholesterol with AtorvastatinDocument2 pagesLower Cholesterol with AtorvastatinNicole Anne TungolNo ratings yet

- Vegucation Over MedicationDocument260 pagesVegucation Over MedicationGod Ra100% (7)

- Impurities List Cattleya PharmaceuticalsDocument20 pagesImpurities List Cattleya Pharmaceuticalssiddhu444No ratings yet

- Evidence Based Cardiology 4th EdDocument424 pagesEvidence Based Cardiology 4th EdROGER LUDEÑA SALAZARNo ratings yet

- Dyslipidemia Final Poster June 24Document2 pagesDyslipidemia Final Poster June 24drabdulrabbNo ratings yet

- Citicoline Mode of ActionDocument5 pagesCiticoline Mode of ActionBeverlyNo ratings yet

- Popular Drugs With Brand Name and Generic NameDocument16 pagesPopular Drugs With Brand Name and Generic NameJason MontesaNo ratings yet

- Pharmaceuticals and Healthcare - 2017 PDFDocument114 pagesPharmaceuticals and Healthcare - 2017 PDFGautam SiddharthNo ratings yet

- Pleiotropic Effects of StatinsDocument5 pagesPleiotropic Effects of StatinsFathur RahmanNo ratings yet

- Leqvio Epar Product Information - enDocument41 pagesLeqvio Epar Product Information - enAditya MadhavpeddiNo ratings yet

- Clinical Chemistry Results and MRI FindingsDocument8 pagesClinical Chemistry Results and MRI FindingsHayzel Rivera RemotoNo ratings yet

- ATI Flash Cards 06, Medications Affecting The Cardiovascular SystemDocument48 pagesATI Flash Cards 06, Medications Affecting The Cardiovascular SystemWiilka QarnigaNo ratings yet

- Beyond Statins - NEW AHA/ACC Cholesterol Guidelines: Diane Osborn ARNP, CLSDocument54 pagesBeyond Statins - NEW AHA/ACC Cholesterol Guidelines: Diane Osborn ARNP, CLSDilan GalaryNo ratings yet

- Natural Medicines Comprehensive Database 2010Document26 pagesNatural Medicines Comprehensive Database 2010PsineticNo ratings yet

- Disorders of Lipid Metabolism Full Article Tables FiguresDocument32 pagesDisorders of Lipid Metabolism Full Article Tables Figureshasnawati100% (1)

- Drug StudyDocument6 pagesDrug Studydwyane0033No ratings yet

- 6 Studii StatineDocument37 pages6 Studii Statinejust4uhopeNo ratings yet

- SuperDrugs! Simon's Short Drug SummaryDocument5 pagesSuperDrugs! Simon's Short Drug Summarybriancripe100% (2)

- Cholesterol Does Not Cause Heart Disease PDFDocument20 pagesCholesterol Does Not Cause Heart Disease PDFRani Oktaviani Sidauruk100% (2)

- Fi H 0840 004 ParDocument16 pagesFi H 0840 004 ParNathaniel Roi BalbarinoNo ratings yet

- Lipid Lowering AgentsDocument2 pagesLipid Lowering Agentsapi-623203696No ratings yet

- January 25, 2010 IDocument75 pagesJanuary 25, 2010 IomairfarooqNo ratings yet

- Cholesterol Lowering Drugs Work in Many Different WaysDocument2 pagesCholesterol Lowering Drugs Work in Many Different WaysSassySeanNo ratings yet

- Chogtu 2015Document7 pagesChogtu 2015Maskur Fahmi ÄdibasNo ratings yet

- Drugs for anemias, coagulation disorders, dyslipidemiaDocument7 pagesDrugs for anemias, coagulation disorders, dyslipidemiaMaha KhanNo ratings yet

- Evolution of Lipid Management GuidelinesDocument63 pagesEvolution of Lipid Management GuidelinesM Azmi HNo ratings yet

- Journal Homepage: - : IntroductionDocument10 pagesJournal Homepage: - : IntroductionIJAR JOURNALNo ratings yet