Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Institutionalizing Health Technology Assessment in Ethiopia Seizing The Window of Opportunity

Uploaded by

IntanGumilOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Institutionalizing Health Technology Assessment in Ethiopia Seizing The Window of Opportunity

Uploaded by

IntanGumilCopyright:

Available Formats

International Journal of Institutionalizing health technology assessment

Technology Assessment in

Health Care

in Ethiopia: seizing the window of opportunity

www.cambridge.org/thc Daniel Erku1,2,3 , Damian Walker4, Ana A. Caruso4 , Befikadu Wubishet5,

Yibeltal Assefa6, Samuel Abera7, Alemayehu Hailu8,9 and Paul Scuffham1,2

1

Centre for Applied Health Economics, School of Medicine, Griffith University, Brisbane, QLD, Australia; 2Menzies Health

Institute Queensland, Griffith University, Brisbane, QLD, Australia; 3Centre for Research and Engagement in Assessment

Commentary of Health Technology (CREATE), Addis Ababa, Ethiopia; 4Health Financing, Technologies, and Market Dynamics, Global

Health Systems Innovation, Management Sciences for Health, Arlington, VA, USA; 5Centre for Economic Impacts of

Cite this article: Erku D, Walker D, Caruso AA, Genomic Medicine, Macquarie University, Sydney, NSW, Australia; 6School of Public Health, The University of

Wubishet B, Assefa Y, Abera S, Hailu A,

Queensland, Brisbane, QLD, Australia; 7Healthcare Financing Technical Advisor Partnership and Coordination,

Scuffham P (2023). Institutionalizing health

Directorate, Ministry of Health, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia; 8Department of Global Public Health and Primary Care,

technology assessment in Ethiopia: seizing the

window of opportunity. International Journal Bergen Center for Ethics and Priority Setting, University of Bergen, Bergen, Norway and 9Harvard T.H. Chan School of

of Technology Assessment in Health Care, 39(1), Public Health, Harvard University, Boston, MA, USA

e49, 1–5

https://doi.org/10.1017/S0266462323000454 Abstract

Received: 29 December 2022 Ethiopia’s commitment to achieving universal health coverage (UHC) requires an efficient and

Revised: 19 June 2023 equitable health priority-setting practice. The Ministry of Health aims to institutionalize health

Accepted: 06 July 2023

technology assessment (HTA) to support evidence-based decision making. This commentary

Keywords: highlights key considerations for successful formulation, adoption, and implementation of HTA

health technology assessment; sub-Saharan policies and practices in Ethiopia, based on a review of international evidence and published

Africa; decision making; capacity building; normative principles and guidelines. Stakeholder engagement, transparent policymaking, sus-

policy making; priority setting tainable financing, workforce education, and political economy analysis and power dynamics are

Corresponding author: critical factors that need to be considered when developing a national HTA roadmap and

Daniel Erku; implementation strategy. To ensure ownership and sustainability of HTA, effective stakeholder

Emails: d.erku@griffith.edu.au; engagement and transparency are crucial. Regulatory embedding and sustainable financing

daniel.asfaw05@gmail.com ensure legitimacy and continuity of HTA production, and workforce education and training are

essential for conducting and interpreting HTA. Political economy analysis helps identify

opportunities and constraints for effective HTA implementation. By addressing these consid-

erations, Ethiopia can establish a well-designed HTA system to inform evidence-based and

equitable resource allocation toward achieving UHC and improving health outcomes.

Introduction

The 2030 sustainable development goals (SDGs), adopted by the United Nations in 2025,

represent a global commitment to sustainable development and aim to address pressing global

challenges. One of the key targets of the SDGs is achieving universal health coverage (UHC) by

2030 (1). UHC means that everyone should have access to quality healthcare services without

facing financial hardship. Achieving UHC requires significant progress toward efficient, access-

ible, quality, and equitable health services while ensuring financial risk protection for households

burdened with significant healthcare expenses (2). However, many low- and middle-income

countries (LMICs) face significant budgeting and financial constraints, making it difficult to

implement their plans toward UHC (2;3). LMICs often have limited fiscal space for health, rely on

donor funding for healthcare, and face significant out-of-pocket (OOP) payments by households.

Additionally, the allocation of limited healthcare resources can be inefficient and inequitable,

further exacerbating access to quality healthcare services.

In Ethiopia, the healthcare sector is funded by various sources including international loans

and donations (35 percent), the Ethiopian Government (32 percent), and OOP payments

(31 percent) (4). Despite an increase in health financing from domestic sources from US$1.3

billion in 2008 to US$3.1 billion in 2017, and an increase in per capita health expenditure from US

© The Author(s), 2023. Published by Cambridge $4.50 in 1995 to US$33.2 in 2017, the amount is still inadequate compared to the recommended

University Press. This is an Open Access article, spending for essential health services (5;6). Furthermore, Ethiopia’s health spending constituted

distributed under the terms of the Creative

Commons Attribution licence (http://

5.6 percent of the gross domestic product (GDP) in the last decade, which is below World Health

creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which Organization (WHO)’s average estimation of 7 percent for low-income countries (7).

permits unrestricted re-use, distribution and OOP payments in Ethiopia account for more than 30 percent of all health spending, which is

reproduction, provided the original article is above the average for sub-Saharan Africa according to the WHO’s Global Health Expenditure

properly cited.

database (8). This heavy reliance on OOP payments can discourage individuals with low socio-

economic status from seeking and accessing healthcare services (9). Donor funding is another

major source of funding in Ethiopia, often channeled toward priority programs such as immun-

ization, infectious diseases, and maternal and child health. However, such funds often depend on

https://doi.org/10.1017/S0266462323000454 Published online by Cambridge University Press

2 Daniel Erku et al.

donor preference and priorities, making it challenging to predict during the development and revision of the EHSP were participa-

the level, flow, and use of resources. Although most health pro- tory, inclusive, evidence-based, and guided by a clear roadmap (16).

grams prioritized by donors are fundamental to achieving UHC, The revision committee applied explicit sets of criteria, in the form

they are often delivered through vertical structures and can raise of multi-criteria decision analysis, to systematically synthesize and

efficiency and sustainability issues, particularly in the absence of collate evidence on clinical effectiveness, cost-effectiveness, equity,

additional funding. and budget impact of health interventions. The use of multi-criteria

Efforts toward achieving UHC and the broader SDGs require a decision criteria in the EHSP revision and consideration of evidence

systematic approach to allocating scarce healthcare resources (10). from economic evaluations indicates a growing interest in and use

This involves determining the financial requirements for UHC, of (economic) evidence to inform health policies in Ethiopia.

deciding on a feasible benefits package given resource constraints, Although the use of multi-criteria decision analysis and evidence-

and identifying priorities for expanding service coverage. Institu- based prioritization in Ethiopia’s priority setting is a positive step

tionalizing health technology assessment (HTA) is critical to forward, there are still several limitations that need to be addressed

addressing these challenges. HTA is a process of evaluating the in order to enhance the effectiveness of the approach.

clinical effectiveness, safety, cost-effectiveness, ethical, and social

implications of healthcare interventions (10). It provides evidence- Lack of relevant data and limited technical capacity

based information to inform healthcare decision making, such as

whether a particular intervention should be adopted, reimbursed, In Ethiopia, there is a lack of relevant country-specific data and the

or covered by health insurance. HTA helps set priorities for health types of evidence generated do not always align with policy needs,

interventions, estimates the impact on budgets, and identifies which presents a challenge to effective priority setting. A review of

potential barriers to uptake that might exacerbate inequities. The published HTA reports and health economic evaluations con-

WHO has recognized the importance of HTA and declared reso- ducted in Ethiopia identified no comprehensive HTA reports and

lutions to adopt it as an essential approach to address global health only thirty-four full health economic evaluations published until

challenges, improve health systems, and achieve SDGs (11). Reso- May 2021 (17). Although some of these economic evaluations were

lution WHA67.23 calls for the institutionalization of HTA within used as inputs in the 2019 revision of the EHSP, the lack of context-

national frameworks to promote evidence-based policy develop- relevant data to conduct contextualized cost-effectiveness analyses

ment and decision making in health systems (11). resulted in many of the input parameters being derived from

HTA has been widely adopted as a means of priority setting in systematic reviews (16;17). The reliance on such evidence can be

high-income countries such as the UK, Australia, and Canada, as problematic, as it may not accurately reflect the local health system,

well as in upper-middle-income countries such as Thailand, Bra- demographics, or epidemiology, limiting the transferability of cost-

zil, and Mexico (12). In recent years, there has been growing effectiveness ratios. It is therefore crucial to generate, collate, and

interest in HTA among sub-Saharan African countries, including archive country-specific data in Ethiopia to produce actionable and

Ethiopia, driven in part by commitments to UHC and the chan- readily interpretable evidence for policymakers. This will not only

ging landscape of donor funding. However, despite this interest, facilitate more effective priority setting but also reduce the depend-

HTA awareness and capacity remains low, and the use of HTA in ence on economic evaluations conducted in different health sys-

policy making is often uncoordinated and disconnected (13). In tems.

this commentary, we argue that the institutionalization of HTA in Another significant factor that hinders effective priority setting

Ethiopia is influenced not only by a lack of awareness and cap- is the lack of local technical capacity in Ethiopia to undertake and

acity, but also by the broader context of public-sector decision interpret economic evaluations across the health sector. HTA

making. To understand the policy and political dynamics that development process often requires a combination of a broad

affect the adoption and implementation of HTA, we applied John mix of skills, including expertise in medicine, epidemiology, bio-

Kingdon’s Multiple Streams Framework (MSF), which has been statistics, economics, psychology, and health outcomes research

successfully used to explore the political prioritization of public fields. Unfortunately, many HTA-related capacity-building activ-

health issues in LMICs (14). The multiple streams in this approach ities in Ethiopia focus solely on technical assistance and do not

are named for the parallel streams of problem, policy, and politics, adequately consider individual, organizational, and institutional

which contain actors and ideas that make up the milieu from aspects of capacity-building, limiting the effectiveness and sustain-

which policies rise to prominence in the agenda-setting process. ability of these efforts.

The development and convergence of these streams make a policy

more likely to rise onto the government’s policy agenda. There- Lack of funding and coordination

fore, policy decisions occur at the confluence of problem, politics,

and policy streams in the case study at hand, which is HTA There is a severe lack of local research funding for conducting

institutionalization in Ethiopia. health economic evaluations (17). More than half of the studies

included in the Erku et al. review of economic evaluation conducted

in Ethiopia (17) were funded by non-governmental organizations

HTA and priority-setting approaches in Ethiopia

or foreign institutions and focused mainly on communicable dis-

In Ethiopia, priority setting for healthcare is made at various levels ease and maternal and child health, reiterating the need for more

of government including the national, regional, district, and service funding, both from the government and external funding agencies,

delivery levels. Over the past few decades, the country has focused to generate reliable, policy-relevant economic evidence in major

on decentralizing healthcare and prioritizing health promotion, chronic diseases. The lack of research funding also raises concerns

disease prevention, and basic curative services. To achieve this, about the sustainability of the EHSP revision exercise, which was

the government has produced a range of documents, such as the made possible with the technical and financial support from Dis-

Essential Health Service Package (EHSP) (15), to inform service ease Control Priorities–Ethiopia (DCP-Ethiopia) project (16). This

delivery and reimbursement. The priority-setting approaches used highlights the need for greater investment in local capacity-building

https://doi.org/10.1017/S0266462323000454 Published online by Cambridge University Press

International Journal of Technology Assessment in Health Care 3

initiatives to enhance the technical expertise required to generate PEA and strategies into policy design, adoption, and implementa-

and interpret contextualized data to inform HTA in Ethiopia, and tion. PEA provides a lens through which to understand the struc-

for the government to prioritize funding for health economic tural and socioeconomic conditions underpinning decision making

research. and conflicting interests. It combines the economics of reforms

In addition to the challenges related to funding, data, and with the politics of change by examining how power and resources

capacity, the lack of coordination and institutionalization has are distributed and how interests, incentives, and institutions

resulted in uncoordinated and fragmented efforts (18). Weak insti- enable or hinder change. PEA can be conducted by segmenting

tutional arrangements and low awareness of HTA among policy- stakeholders into distinct subgroups, such as interest group politics,

makers have also been identified as critical barriers to the bureaucratic politics, budget politics, leadership politics, benefi-

institutionalization of HTA and the priority-setting process in ciary politics, and external actor politics (20). By doing so, policy-

Ethiopia. Moreover, apart from the EHSP, there is little to no clear makers can identify which stakeholders are most likely to be

evidence on the priority-setting criteria and methods used in other engaged and consider the political feasibility of specific reforms.

key policy documents such as the Pharmaceuticals Procurement PEA can provide insights into how HTA and priority-setting

List (used by Ethiopian Pharmaceutical Supply Agency) and the process may evolve in response to broader health financing and

Health Benefits Package (used by Ethiopia’s health insurance health system reforms. The findings can help policymakers under-

agency) (18). These limitations of the current priority-setting stand how the political, structural, and socioeconomic contexts

approach underscore the need to establish sustainable, locally- shape the development and implementation of HTA and identify

owned mechanisms for effective, equitable, and sustainable the extent to which agencies transform decision making and dis-

resource allocation in Ethiopia beyond donor funding and place irrationality in the system. Moreover, incorporating PEA into

demand-driven technical support. Such mechanisms should be reform processes can help policymakers develop more effective

informed by a robust institutional framework and a coordinated approaches to navigate the political challenges that arise when

approach to HTA and priority setting. introducing policy change and ensure that priority setting is more

explicit, equitable, and sustainable.

Institutionalizing HTA and evidence-informed priority

setting Human resources and capacities for HTA

To address the challenges in Ethiopia’s health priority-setting Sustainable improvements in the performance of key HTA-related

process, the Ministry of Health is taking steps to develop a national initiatives require more than just on-demand technical assistance

HTA roadmap based on evidence-based recommendations from a and knowledge transfer at the individual level. It is also important to

situation analysis. The aim is to strengthen the existing HTA- establish robust technical and operational systems that can carry

related activities in the Ethiopian health system in a more institu- HTA work forward into the future. This includes developing local

tionalized and harmonized way as well as working toward having a technical capacity to undertake and interpret economic evalu-

strong HTA body in Ethiopia. In the following sections, we briefly ations, collecting relevant country-specific data, and establishing

discuss: (i) examination of the institutional context and power strong institutional arrangements that support HTA and priority-

dynamics between stakeholders (political economy analysis setting processes. Finally, it is important to learn from countries

[PEA]), (ii) human resources and capacities for HTA and (iii) a with comparable healthcare systems to Ethiopia, and to translate

reflection on the experiences and lessons derived from healthcare those findings to the Ethiopian context. This includes answering

systems of a comparable nature. Drawing on existing evidence (19), key cross-cutting questions, such as why HTA is being done, what

the integration of these aspects with a comprehensive analysis of the the scope of HTA is in terms of interventions, products, or services,

healthcare system and current decision making methodologies how and by whom HTA is conducted, and how HTA is used, and

should form the foundation for an evidence-based HTA strategy. what the key knowledge dissemination strategies are. By taking

This grounding paves the way for a robust and sustainable practice these considerations into account, Ethiopia can develop a sustain-

of evidence-based priority setting. able and locally owned mechanism for effective, equitable, and

sustainable resource allocation, which can support the achievement

of UHC.

The political economy of HTA institutionalization

The process of priority setting in healthcare is complex and

International experiences regarding HTA institutionalization

involves multiple stakeholders with diverse interests, preferences,

and expectations. Reforms aimed at making priority setting more When developing a national HTA strategy, it is helpful to incorp-

explicit must take into account the broader socio-economic fiscal, orate experiences and lessons from comparable healthcare systems

and political governance contexts in which stakeholders operate. and make deductive conclusions from international knowledge.

These contexts can influence the governance of HTA and the Based on the findings from an analysis of multi-country experi-

priorities and feasibility of improving it. For example, when ences and supplemented with Battista et al. “natural history” of

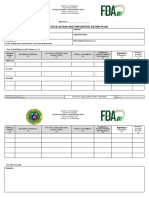

deciding on benefit package specifications, policymakers must HTA (21), we provided a summary of three phases of HTA devel-

consider heterogeneity in preferences and expectations, which opment: “emergence,” “consolidation” and “expansion” (Figure 1).

involves multiple stakeholders within or across different sectors, Currently, Ethiopia’s status regarding HTA development is best

each with different interests that may not necessarily align. To described as in the “emergence” phase. With Ethiopia’s recent

achieve effective priority setting, policymakers must navigate progress toward a public insurance funding mechanism, it is crucial

these complex contexts and work to balance competing interests to employ HTA to ensure that claims and reimbursements for

and goals. services and health technologies are well justified. Given that tran-

The formulation, adoption, and institutionalization of HTA are sitioning to a more structured priority-setting approach takes time,

inherently political, and thus, policymakers should incorporate initial HTA efforts may focus on “high cost” or priority health

https://doi.org/10.1017/S0266462323000454 Published online by Cambridge University Press

4 Daniel Erku et al.

Figure 1. Phases of HTA development.

technologies to determine the value for money and whether or not commenced by academic “champions” to manage the inefficient

the technology should be recommended for government reim- and inequitable distribution of limited healthcare resources. One

bursement or should be made widely available to the people of of the most important milestones in Thailand’s HTA institu-

Ethiopia. The progression through the different phases of HTA tionalization journey was the establishment of Health Interven-

development and the establishment of institutional and governance tion and Technology Assessment Program (HITAP) in 2007,

arrangements for HTA are interrelated with the evolution of the which has served the country’s Subcommittee for the develop-

country’s overall health system, including the current payment ment of the Benefits Package and Service Delivery as a technical

mechanisms. In order to effectively transition through these phases, focal point (24).

it is important to build on existing strengths, manage potential

barriers, and create new opportunities for the meaningful and

Where to from here? Seizing the window of opportunity

sustainable production and use of HTA products at both the policy

and practice level. As a country with limited resources, Ethiopia needs an efficient

International experiences from countries suggest that certain and equitable health priority-setting practice to achieve UHC. In

strategies can alleviate common barriers to the institutionaliza- recent years, there has been an increased interest in using explicit,

tion of HTA. These include establishing a legal mandate for evidence-based priority-setting criteria in health policy making in

HTA, building local technical capacity through partnerships, Ethiopia. The Health Economics and Financing Analysis (HEFA)

and enhancing strategic communication with stakeholders unit and the Ethiopian Public Health Institute have been leading

(18). An excellent example of such initiatives is the work being the way in the design and execution of various demand-driven

done in Ghana. Before 2016, spending on medicines constituted HTA projects in Ethiopia. Despite efforts to introduce HTA,

nearly half (46 percent) of the total health expenditure in the barriers such as the lack of local technical capacity, limited rele-

country, 60 percent of which was being spent only on antihy- vant country-specific data, weak institutional arrangements, and

pertensives and antibiotics due to inappropriate prescribing, low awareness of HTA among policymakers still hinder the insti-

polypharmacy, and inefficient supply chain. The Ghanaian Min- tutionalization of HTA and priority-setting processes. To address

istry of Health, supported by an international decision support these challenges, the Ministry of Health of Ethiopia plans to

initiative, conducted an HTA study to examine the cost- introduce HTA as one of the main implementation strategies of

effectiveness of antihypertensives (22). The findings indicated the Health Sector Transformation Plan (HSTP II) and to produce

that, in the Ghanaian context, diuretics and calcium channel a national HTA strategy followed by various knowledge products

blockers would be more effective and less expensive than other (25).

drug classes, such as beta-blockers, angiotensin-converting This commentary provides insights into the key considerations

enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers (23). This for successful formulation, adoption, and implementation of HTA

exercise saved the Ghanaian Government US$11.2 million, policies and practices in Ethiopia. Stakeholder engagement, trans-

which is now available for hypertension prevention and early parent policymaking, sustainable financing, workforce education,

detection. Thailand is another excellent example. Efforts to use and political economy and power dynamics are critical factors that

HTA methods to inform healthcare decisions in Thailand should be considered while developing a national HTA roadmap

https://doi.org/10.1017/S0266462323000454 Published online by Cambridge University Press

International Journal of Technology Assessment in Health Care 5

and implementation strategy. Ensuring effective stakeholder 11. World Health Organization. World Health Assembly, 67 (2014). Health

engagement and transparency is essential to ensure ownership intervention and technology assessment in support of universal health cover-

and sustainability of HTA. Regulatory embedding and sustainable age; 2014. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/162870.

financing are important to ensure legitimacy and continuity of 12. Teerawattananon Y, Painter C, Dabak S, et al.. Avoiding health technology

assessment: A global survey of reasons for not using health technology

HTA production. Workforce education and training are essential

assessment in decision making. Cost Eff Resour Alloc. 2021;19(1):1–8.

for conducting and interpreting HTA, and PEA helps identify 13. Hollingworth S, Fenny AP, Yu S-Y, Ruiz F, Chalkidou K. Health tech-

opportunities and constraints for effective HTA implementation. nology assessment in sub-Saharan Africa: A descriptive analysis and nar-

By establishing a well-designed and locally owned HTA system, rative synthesis. Cost Eff Resour Alloc. 2021;19(1):39.

Ethiopia can make informed decisions toward achieving UHC and 14. Kusi-Ampofo O, Church J, Conteh C, Heinmiller BT. Resistance and

improving health outcomes, building on successful experiences in change: A multiple streams approach to understanding health policy mak-

other countries. ing in Ghana. J Health Polit Policy Law. 2015;40(1):195–219.

15. Ministry of Health of Ethiopia. Essential health services package of Ethi-

Funding statement. This work was supported by the U.S. Agency for Inter- opia. Addis Ababa: Ministry of Health of Ethiopia; 2019.

national Development (USAID) contract no. 7200AA18C00074. 16. Eregata GT, Hailu A, Geletu ZA, et al.. Revision of the Ethiopian essential

health service package: An explication of the process and methods used.

Competing interest. The authors declare that they have no known competing Health Syst Reform. 2020;6(1):e1829313.

financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influ- 17. Erku D, Mersha AG, Ali EE, et al.. A systematic review of scope and quality

ence the work reported in this paper. of health economic evaluations conducted in Ethiopia. Health Policy Plan.

2022;37(4):514–522.

18. Kim T, Sharma M, Teerawattananon Y, et al. Addressing challenges in

References

health technology assessment institutionalization for furtherance of univer-

1. Yamey G, Shretta R, Binka FN. The 2030 sustainable development goal for sal health coverage through south–south knowledge exchange: Lessons

health. BMJ. 2014;348:g5295. from Bhutan, Kenya, Thailand, and Zambia. Value Health Reg Issues.

2. McIntyre D, Obse AG, Barasa EW, Ataguba JE. Challenges in financing 2021;24:187–192.

universal health coverage in sub-Saharan Africa. In Oxford research encyclo- 19. Bertram M, Dhaene G, Tan-Torres Edejer T. Institutionalizing health

pedia of economics and finance. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2018. technology assessment mechanisms: A how to guide. Geneva: World Health

3. Hanson K, Brikci N, Erlangga D, et al.. The Lancet Global Health Com- Organization; 2021.

mission on financing primary health care: Putting people at the centre. 20. Campos PA, Reich MR. Political analysis for health policy implementation.

Lancet Global Health. 2022;10(5):e715–e772. Health Syst Reform. 2019;5(3):224–235.

4. World Health Organization. Primary health care systems (primasys): Case 21. Battista RN, Hodge MJ. The “natural history” of health technology assess-

study from Ethiopia (abridged version). Geneva: World Health Organiza- ment. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2009;25(S1):281–284.

tion; 2017. 22. Addo R, Goodall S, Hall J, Haas M. Assessing the capacity of Ghana to

5. U.S. Agency for International Development. Ethiopia’s health financing introduce health technology assessment: A systematic review of economic

outlook: What six rounds of health accounts tell us. Washington: United evaluations conducted in Ghana. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2020;36(5):

States Agency for International Development; 2018. 500–507.

6. Jowett M, Brunal MP, Flores G, Cylus J. Spending targets for health: No 23. Gad M, Lord J, Chalkidou K, et al.. Supporting the development of

magic number. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2016. evidence-informed policy options: An economic evaluation of hypertension

7. World Health Organization. New perspectives on global health spending for management in Ghana. Value Health. 2020;23(2):171–179.

universal health coverage. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2017. 24. Leelahavarong P, Doungthipsirikul S, Kumluang S, et al. Health technol-

8. World Health Organization. Global health expenditure database. Geneva: ogy assessment in Thailand: Institutionalization and contribution to health-

World Health Organization; 2022. care decision making: review of literature. Int J Technol Assess Health Care.

9. Kiros M, Dessie E, Jbaily A, et al.. The burden of household out-of-pocket 2019;35(6):467–473.

health expenditures in Ethiopia: Estimates from a nationally representative 25. Ministry of Health. The Ethiopian health sector transformation plan II.

survey (2015–16). Health Policy Plan. 2020;35(8):1003–1010. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: Ethiopian Ministry of Health; 2020 [cited

10. Chalkidou K, Marten R, Cutler D, et al.. Health technology assessment in 2021 August 11]. Available from: https://www.moh.gov.et/ejcc/am/node/

universal health coverage. Lancet. 2013;382(9910):e48–e49. 152.

https://doi.org/10.1017/S0266462323000454 Published online by Cambridge University Press

You might also like

- Iubjbkb KLDocument21 pagesIubjbkb KLJohn-adewaleSmithNo ratings yet

- Health Financing For Universal HealthDocument9 pagesHealth Financing For Universal HealthMirani BarrosNo ratings yet

- Health Facilities Roles in Measuring Progress of Universal Health CoverageDocument10 pagesHealth Facilities Roles in Measuring Progress of Universal Health CoverageIJPHSNo ratings yet

- sdg3 AkucheDocument31 pagessdg3 AkucheJohn-adewaleSmithNo ratings yet

- OXFORD Bart Jacobs, Sam Sam Oeun, Por Ir, Susan Rifkin, Wim Van DammeDocument11 pagesOXFORD Bart Jacobs, Sam Sam Oeun, Por Ir, Susan Rifkin, Wim Van DammeMuhammad NasherNo ratings yet

- Health EconomicsDocument23 pagesHealth EconomicsmanjisthaNo ratings yet

- Journal Pone 0152866Document20 pagesJournal Pone 0152866yulya lasmitaNo ratings yet

- Is The Routine Health Information System Ready To Support The Planned National Health Insurance Scheme in South Africa?Document12 pagesIs The Routine Health Information System Ready To Support The Planned National Health Insurance Scheme in South Africa?Glimex Pty LtdNo ratings yet

- Building Health Literacy System CapacityDocument11 pagesBuilding Health Literacy System Capacitynuno ferreiraNo ratings yet

- 04-Health Insurance in India - What Do We Know and Why Is Ethnographic Research NeededDocument24 pages04-Health Insurance in India - What Do We Know and Why Is Ethnographic Research Neededmeljo johnNo ratings yet

- Health Insurance in India What Do We Know and Why Is Ethnographic Research NeededDocument24 pagesHealth Insurance in India What Do We Know and Why Is Ethnographic Research Neededankita2004nishadNo ratings yet

- The Knowledge, Ability, and Skills of Primary Health Care Providers in SEANERN Countries: A Multi-National Cross-Sectional StudyDocument8 pagesThe Knowledge, Ability, and Skills of Primary Health Care Providers in SEANERN Countries: A Multi-National Cross-Sectional StudyAzubeda SaidiNo ratings yet

- How Least Developed To Lower-Middle Income Countries Use Health Technology Assessment A Scoping ReviewDocument17 pagesHow Least Developed To Lower-Middle Income Countries Use Health Technology Assessment A Scoping ReviewIntanGumilNo ratings yet

- Mebratie Pub 7Document8 pagesMebratie Pub 7AnuNo ratings yet

- Review Jurnal Pembiayaan Kesehatan 2Document5 pagesReview Jurnal Pembiayaan Kesehatan 2SUCI PERMATANo ratings yet

- Ameyaw_2021_Is the National Health_Insurance Helping Pregnant Women Access HealthcareDocument9 pagesAmeyaw_2021_Is the National Health_Insurance Helping Pregnant Women Access Healthcarepapaebojackson2004No ratings yet

- Sustainable Thresholds, Health Outcomes, Health Expenditures and Education Nexus in Selected African Countries: Quadratic and Moderation ModellingDocument15 pagesSustainable Thresholds, Health Outcomes, Health Expenditures and Education Nexus in Selected African Countries: Quadratic and Moderation ModellingHuy Lê ThanhNo ratings yet

- Abstract The Roleof Health Information Systemsin Achieving Universal Health Coverage AbdullaDocument2 pagesAbstract The Roleof Health Information Systemsin Achieving Universal Health Coverage AbdullaROBBIE PALCENo ratings yet

- Public Health CourseworkDocument12 pagesPublic Health CourseworkAndrew AkamperezaNo ratings yet

- MaccedoniaDocument11 pagesMaccedoniaKenny Richard TheoNo ratings yet

- UNDP Issue Brief - Universal Health Coverage For Sustainable DevelopmentDocument16 pagesUNDP Issue Brief - Universal Health Coverage For Sustainable DevelopmentbabubvNo ratings yet

- hsr2 254Document16 pageshsr2 254BarneyNo ratings yet

- The Economics of Universal Healthcare A Comparative Analysis of Healthcare Systems and Their Economic EffectsDocument5 pagesThe Economics of Universal Healthcare A Comparative Analysis of Healthcare Systems and Their Economic EffectskeeshiaNo ratings yet

- Aikens_2020_Positioning the NHISDocument16 pagesAikens_2020_Positioning the NHISpapaebojackson2004No ratings yet

- IHCDocument30 pagesIHCAbhijit PathakNo ratings yet

- Fpubh 11 1078462Document15 pagesFpubh 11 1078462BiyaNo ratings yet

- Ajol File Journals - 53 - Articles - 8659 - Submission - Proof - 8659 625 12941 1 10 20040217Document4 pagesAjol File Journals - 53 - Articles - 8659 - Submission - Proof - 8659 625 12941 1 10 20040217Alaiza Jane TandegNo ratings yet

- Demand in Health Care AnalysisDocument9 pagesDemand in Health Care AnalysisZewdu MinwuyeletNo ratings yet

- Equity in Healthcare Financing in ZimbabweDocument5 pagesEquity in Healthcare Financing in ZimbabweInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- State Led Innovations For Achieving UnivDocument8 pagesState Led Innovations For Achieving UnivPragyan MonalisaNo ratings yet

- Strengthening health systems for universal health coverage and sustainable developmentDocument3 pagesStrengthening health systems for universal health coverage and sustainable developmentghoudzNo ratings yet

- Uncovering Progress of Health Information Management PracticesDocument32 pagesUncovering Progress of Health Information Management PracticeskhalidgnNo ratings yet

- CSIS Policy Brief Reforming Sustainable Healthcare System Lesson Learned From Three Countries in ASEANDocument17 pagesCSIS Policy Brief Reforming Sustainable Healthcare System Lesson Learned From Three Countries in ASEANBersama Budi Kembali BerbaktiNo ratings yet

- Application of Artificial Intelligence To The Public Health EducationDocument7 pagesApplication of Artificial Intelligence To The Public Health Educationmgw backupdataNo ratings yet

- SDG 3: Progress, Gaps and Recommendations For The UKDocument6 pagesSDG 3: Progress, Gaps and Recommendations For The UKjaycats07No ratings yet

- Analysis of The Health Financing Structure of BotswanaDocument5 pagesAnalysis of The Health Financing Structure of BotswanaOlusola Olabisi OgunseyeNo ratings yet

- Intentions To Use MWHs and Associated Factors in Northwest EthiopiaDocument10 pagesIntentions To Use MWHs and Associated Factors in Northwest EthiopiaMezgebu Yitayal MengistuNo ratings yet

- Are We Too Far From Being Client-CenteredDocument12 pagesAre We Too Far From Being Client-CenteredAyinengidaNo ratings yet

- ing the burden 2020-2015 16Document8 pagesing the burden 2020-2015 16EstreLLA ValenciaNo ratings yet

- Research Article Willingness To Pay For Social Health Insurance and Associated Factors Among Health Care Providers in Addis Ababa, EthiopiaDocument7 pagesResearch Article Willingness To Pay For Social Health Insurance and Associated Factors Among Health Care Providers in Addis Ababa, EthiopiaaisyahNo ratings yet

- Assessing The Feasibility of Community Health Insurance in Uganda: A Mixed-Methods Exploratory AnalysisDocument12 pagesAssessing The Feasibility of Community Health Insurance in Uganda: A Mixed-Methods Exploratory AnalysisbejarhasanNo ratings yet

- The Universal Health Coverage Ambition Faces A Critical Test.Document2 pagesThe Universal Health Coverage Ambition Faces A Critical Test.Brianna Vivian Rojas TimanaNo ratings yet

- Mothers ' Experiences of Quality of Care and Potential Benefits of Implementing The WHO Safe Childbirth Checklist: A Case Study of Aceh IndonesiaDocument8 pagesMothers ' Experiences of Quality of Care and Potential Benefits of Implementing The WHO Safe Childbirth Checklist: A Case Study of Aceh Indonesialisnawati rahayuNo ratings yet

- Universal Health Coverage For Non-Communicable Diseases and Health Equity: Lessons From Australian Primary HealthcareDocument11 pagesUniversal Health Coverage For Non-Communicable Diseases and Health Equity: Lessons From Australian Primary HealthcareNicolás ManonniNo ratings yet

- Re Engineering Indian Healthcare 2.0 - FICCI PDFDocument204 pagesRe Engineering Indian Healthcare 2.0 - FICCI PDFkishore13No ratings yet

- Building The Primary of The 21st Century: Health Care WorkforceDocument32 pagesBuilding The Primary of The 21st Century: Health Care Workforcelucila falconeNo ratings yet

- Assessing The Feasibility of Introducing Health Insurance in Afghanistan: A Qualitative Stakeholder AnalysisDocument9 pagesAssessing The Feasibility of Introducing Health Insurance in Afghanistan: A Qualitative Stakeholder AnalysisbejarhasanNo ratings yet

- Adoption of Health Technologies For Effective Health Information SystemDocument22 pagesAdoption of Health Technologies For Effective Health Information SystemFitriani FitrianiNo ratings yet

- Towards Universal Health Coverage and Sustainable Financing in Afghanistan: Progress and ChallengesDocument5 pagesTowards Universal Health Coverage and Sustainable Financing in Afghanistan: Progress and ChallengesAyu NovitaNo ratings yet

- HEAL 2013 RecommendationsDocument39 pagesHEAL 2013 RecommendationsDhawan SandeepNo ratings yet

- OConnell-What Does UHC MeanDocument3 pagesOConnell-What Does UHC MeanMamadou Selly LyNo ratings yet

- WHO Study GuideDocument18 pagesWHO Study Guidegis.kieraNo ratings yet

- Ethiopia's Community-Based Health Insurance: A Step On The Road To Universal Health CoverageDocument12 pagesEthiopia's Community-Based Health Insurance: A Step On The Road To Universal Health CoverageTsegayeNo ratings yet

- Mary Mavole NdoloDocument23 pagesMary Mavole NdoloJohnson MavoleNo ratings yet

- Ijerph 20 07112Document17 pagesIjerph 20 07112Hina SardarNo ratings yet

- Trends and challenges of public health care financing in NigeriaDocument8 pagesTrends and challenges of public health care financing in NigeriaMella PutriNo ratings yet

- Spatial Distribution and Associated Factors of Health Insurance Coverage in Ethiopia: Further Analysis of Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey, 2016Document11 pagesSpatial Distribution and Associated Factors of Health Insurance Coverage in Ethiopia: Further Analysis of Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey, 2016aisyahNo ratings yet

- Jurnal 3Document8 pagesJurnal 3Api Rosela AlfiNo ratings yet

- Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Health Sector Review: Hospital CareFrom EverandKhyber Pakhtunkhwa Health Sector Review: Hospital CareNo ratings yet

- WHO Community ResourcesDocument8 pagesWHO Community ResourcesabuumaiyoNo ratings yet

- Role of Clinical Nurse Specialist and EbpDocument10 pagesRole of Clinical Nurse Specialist and Ebpapi-255626529No ratings yet

- Psychiatric Services: Area 2: Psychiatric Hospitals Town Hill Hospital Umzikulu Umgeni Fort Napier Hospital MadadeniDocument1 pagePsychiatric Services: Area 2: Psychiatric Hospitals Town Hill Hospital Umzikulu Umgeni Fort Napier Hospital MadadeniprabhaNo ratings yet

- Subject: Health Grade: 4 UNIT 3: Substance Use and Abuse LESSON 3: Using Medicine Properly ObjectivesDocument4 pagesSubject: Health Grade: 4 UNIT 3: Substance Use and Abuse LESSON 3: Using Medicine Properly ObjectivesJerome Eziekel Posada PanaliganNo ratings yet

- Typology of 21 Nursing ProblemsDocument18 pagesTypology of 21 Nursing ProblemsJaneth Cambronero CayetanoNo ratings yet

- Nursing Informatics: The Emerging FieldDocument46 pagesNursing Informatics: The Emerging FieldGracy CasañaNo ratings yet

- Moderate Viral Croup: Curricular InformationDocument3 pagesModerate Viral Croup: Curricular InformationAlexandr SergeevichNo ratings yet

- Kaela Snodgrass: Registered Dental HygienistDocument1 pageKaela Snodgrass: Registered Dental Hygienistapi-498295251No ratings yet

- Peace Corps Medical Doctor, Nurse, Nurse Practitioner or Physician Assistant - Contract PCMODocument3 pagesPeace Corps Medical Doctor, Nurse, Nurse Practitioner or Physician Assistant - Contract PCMOAccessible Journal Media: Peace Corps DocumentsNo ratings yet

- Patient Case StudyDocument26 pagesPatient Case StudyDinesh BanerjeeNo ratings yet

- A Blinded, Randomized, Controlled Trial Assessing Conservative Management Strategies For Frozen ShoulderDocument4 pagesA Blinded, Randomized, Controlled Trial Assessing Conservative Management Strategies For Frozen ShoulderSergiNo ratings yet

- Criteria for assessing post-surgery patient readiness for transfer from recovery areaDocument2 pagesCriteria for assessing post-surgery patient readiness for transfer from recovery areaDnyanesh AitalwadNo ratings yet

- Disability The Missing Puzzle Piece Baseline Review of The Situation of People With Disabilities in MacedoniaDocument138 pagesDisability The Missing Puzzle Piece Baseline Review of The Situation of People With Disabilities in MacedoniaPolio Plus - movement against disabilityNo ratings yet

- Resume KRDocument1 pageResume KRapi-662026473No ratings yet

- Capa 2018Document3 pagesCapa 2018Lexi MontanteNo ratings yet

- E-Brochure International AYUSH Conference Dubai 2020Document8 pagesE-Brochure International AYUSH Conference Dubai 2020Dr. KaarthikaNo ratings yet

- Advances in Psychiatry Second VolumeDocument301 pagesAdvances in Psychiatry Second VolumeAlice Douglas100% (3)

- Ebook PTDocument24 pagesEbook PTMuhammad NurtiyantoNo ratings yet

- 4 - Guidelines For HIV Care and Treatment in Infants and ChildrenDocument136 pages4 - Guidelines For HIV Care and Treatment in Infants and Childreniman_kundu2007756100% (1)

- GUIDE INTENSIVE CARE SOCIETY WEANINGDocument4 pagesGUIDE INTENSIVE CARE SOCIETY WEANINGdeliejoyceNo ratings yet

- Gambaran Status Gizi Pada Pasien Tuberkulosis Paru (TB Paru) Yang Menjalani Rawat Inap Di Rsud Arifin Achmad PekanbaruDocument33 pagesGambaran Status Gizi Pada Pasien Tuberkulosis Paru (TB Paru) Yang Menjalani Rawat Inap Di Rsud Arifin Achmad PekanbaruAmalia SuryaniNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2 Pharmacokinetics of Drug AbsorptionDocument27 pagesChapter 2 Pharmacokinetics of Drug AbsorptionTMTNo ratings yet

- Application for Tutor PositionDocument2 pagesApplication for Tutor PositionMythNo ratings yet

- Cna Resume Template FreeDocument4 pagesCna Resume Template Freeafmrhbpxtgrdme100% (1)

- Guideline Standards Practice Complete PDFDocument21 pagesGuideline Standards Practice Complete PDFNavanayan ghimireNo ratings yet

- NurseCorps Part 10Document36 pagesNurseCorps Part 10smith.kevin1420344No ratings yet

- CaplanisDocument12 pagesCaplanisCarlos Zepeda GuidoNo ratings yet

- Chapter 047Document2 pagesChapter 047cjahleeNo ratings yet

- Pediatrics Overview: Development, Socio-cultural Issues, Environment and Community RoleDocument3 pagesPediatrics Overview: Development, Socio-cultural Issues, Environment and Community RoledadaNo ratings yet

- Customers Roles in Service DeliveryDocument11 pagesCustomers Roles in Service DeliveryHeeru TejwaniNo ratings yet

- Cases in Health Services Management Sixth Edition 6th Edition Ebook PDFDocument61 pagesCases in Health Services Management Sixth Edition 6th Edition Ebook PDFkelli.rechtzigel668100% (42)