Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Tyrer 1974

Uploaded by

Somente CoisasOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Tyrer 1974

Uploaded by

Somente CoisasCopyright:

Available Formats

long has been known that tremor may be a prominent

Tremor in Acute (Problemata

It symptom in anxiety. This was noted by Aristotle

947" 10) and in the book of Ecclesiastes (12:1,

and Chronic Anxiety 3), and the common expressions, "shivering with fear,"

"quaking with horror," and "chattering teeth," all illus¬

trate the association between tremor and emotion. Like

much that is common knowledge, however, the actual ori¬

Peter J. Tyrer, MRCP, Malcolm H. Lader, MD

gins of the phenomenon are unknown, although the in¬

crease of tremor that occurs in states of excitement is bet¬

ter understood. The earliest objective measurements of

Finger tremor between 2 and 32 hertz in frequency was measured tremor were carried out in the 19th century by the tam¬

in two groups of anxious subjects. In one study 32 normal subjects

bour method, in which the movements of the trembling

were made acutely anxious by experimental stressors, and their

tremor was measured and compared with rest conditions. In a sec- limb were transmitted by a rubber diaphragm to a pen

ond study, tremor was measured in 28 chronically anxious psychiat- that traced out the movements on a smoked drum.'·2 Con¬

ric patients and in 28 control subjects matched for age and sex. No sidering the relative crudity of this method, the results ob¬

differences were found in the peak frequency of tremor in any of the tained were remarkably good. Charcot2 was able to divide

groups, but the amount of tremor was greater in the anxious sub- pathological tremor into three groups based on frequency

jects. The differences were greatest at tremor in the frequency range alone: slow (four to five tremors per second), found in dis¬

between 6 and 17 Hz. The results support the view that the differ- seminated sclerosis, senility, and Parkinson disease; inter¬

ences between normal and anxious tremors are those of degree, not mediate (5Vè to 6 per second), which he classified as "hys¬

of nature.

terical"; and rapid or vibratile (eight to nine per second),

characteristic of thyrotoxicosis, mercury poisoning, alco¬

holism, and general paralysis of the insane.

Although Charcot's classification proved to be correct

for parkinsonian tremor, this was not so for the other

categories. Several years earlier1 it had been shown that

tremor of about 10 hertz consistently accompanied volun¬

tary muscular activity, and most studies of physiological

tremor have found this frequency peak to be surprisingly

constant under a wide range of experimental conditions.

Tremor measured in anxious and neurotic patients has

produced a wider range of results: Graham4 found a mean

frequency of 14 Hz; Redfearn,5 in a study of neurotic pa¬

tients, described a peak of 8 Hz for tremor measured in a

subgroup of anxiety states; and Carrie" found a peak of 7

to 10 Hz, with a greater amplitude in men than in women.

The amount of tremor recorded in anxious subjects was

invariably greater than in normal subjects in all these

studies.

At least some of the differences in these studies may be

explained by different techniques of measurement. In re¬

cent years improvement in these techniques had led to

more reliable results. Advantage was taken of these to

Accepted for publication March 8, 1974.

From the Department of Psychiatry, Institute of Psychiatry, University

of London.

Reprint requests to the Departmant of Psychiatry, South Block, South-

ampton General Hospital, Southampton, England (Dr. Tyrer).

Downloaded From: http://archpsyc.jamanetwork.com/pdfaccess.ashx?url=/data/journals/psych/12251/ by a University of California - San Diego User on 01/25/2017

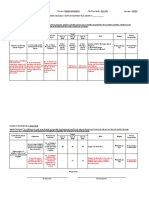

Analog to digital

<*- Eight samples of 4.8 sec

*- Autocorrelation function

«- Power spectral density

Computer

Fig 1.—Apparatus for recording tremor.

record tremor in a range of conditions in which anxiety chosen after visual inspection of the acceleration on an os¬

was deliberately induced in normal subjects, in psychiatric cilloscope (Tektronix 502A). Recordings lasted for about a minute

on each occasion. During recording, the analog signals represent¬

outpatients with chronic anxiety, and in a matched control

group. ing acceleration were filtered to allow only frequencies between 2

and 32 Hz to pass (Kemo Filters Ltd.) before on-line analysis,

Methods using a computer (PDP 12A, Digital Equipment Corporation). In

the analysis, eight epochs of tremor, each comprising 4.8 seconds,

The technique used in the studies involved the measurement of were displayed individually on the computer oscilloscope. The

acceleration with a commercially available subminiature acceler- tremor was also recorded simultaneously on one channel of mag¬

ometer (Ether BLA 2 model, Pye Industries Ltd.). This comprises netic tape, using an analog tape recorder (Ampex SP 300). The to¬

two active inductive bridge arms, each wound within a magnetic tal sample was subjected to power spectral analysis, a technique

shield. The air gap between the bridge arms is controlled by a derived from communications engineering,8 in which the amount

seismically suspended magnetic armature. The accelerometer is of tremor in each hertz between 2 and 32 Hz was calculated by au¬

supplied with only two bridge arms and it is necessary to make up tocorrelation, followed by a Fourier transform. To normalize the

the two remaining arms and incorporate a dry battery (1.5 v) to distribution of data, logarithmic conversion was carried out be¬

complete the Wheatstone bridge. The accelerometer is light (2.5 fore statistical testing. The full procedure is shown diagrammat-

gm) and compact (17x7x5 mm), and is easily attached to the ically in Figure 1.

trembling part without altering the inertia of the system. The ac¬ Anxiety was induced in 32 paid, normal subjects by three

celerometer measures movement in the vertical plane only, so ar¬ stressful situations: (1) electric shocks given to the upper arm at a

tifacts due to lateral movement are not recorded. The range of the level that the subject was just able to tolerate, (2) the same proce¬

accelerometer is much greater than that normally required for dure following the taking of isoproterenol sulfate (Medihaler-Iso),

physiological purposes (± 20 g), but it is sensitive to an accuracy and (3) exposure to a phobic stimulus (usually of animals such as

of ± 5% and has a frequency response of 1 to 100 Hz. The accel¬ snakes, spiders, or rats) that was chosen in advance to produce an

erometer has been used successfully in several studies of postural increase in anxiety that was unpleasant but not sufficiently dis¬

tremor and gives reliable recordings.' turbing to disrupt the experiment. The situations were repeated

Before recording, the accelerometer was taped to the middle in the same order for each subject. Both before and after exposure

finger of the left hand immediately behind the fingernail. The left to these stresses subjects were tested at rest, so that for each sub¬

forearm was supported to the level of the wrist joint and the wrist ject there were five tremor recordings. Three types of stress were

fixed with a Velcro band. The subject was asked to look straight chosen because of the difficulties of creating anxiety in an experi¬

ahead during the period of recording, and the left hand was held mental situation that is similar to real-life anxiety. The phobic sit¬

horizontally with the forearm pronated and the fingers slightly uation approximated most closely normally experienced anxiety,

abducted. Preliminary tests showed that this gave reliable record¬ but lacked the standardization of the other two stresses. Isopro¬

ings. terenol was included as well as electric shocks, because cate-

The analog signals representing acceleration of the trembling cholamines are known to increase anxiety in anxiety-provoking

finger were amplified 10s to 104 times by an amplifier (Grass situations.8

P511C) with the half amplitude upper and lower frequencies set at The 28 psychiatric patients all had a primary diagnosis of anxi¬

1,000 Hz and 0.3 Hz, respectively. The amplification factor was ety state, and symptoms of anxiety were present continuously for

Downloaded From: http://archpsyc.jamanetwork.com/pdfaccess.ashx?url=/data/journals/psych/12251/ by a University of California - San Diego User on 01/25/2017

at least the previous four months. All were drug-free at the time sured to the nearest 0.5 Hz for each subject, yielded F ra¬

of assessment, and none had taken phenothiazines or anti- tios of 0.42 in the acute anxiety study and 0.15 in the

depressants in the three weeks prior to testing. The 28 controls chronic anxiety study, thus showing that, despite the

were matched individually with the patients for age (± 3 years)

and sex. Both patients and control subjects were unfamiliar with

changes in amount of tremor, the main frequency re¬

mained essentially constant. The differences in amount of

the experimental situation before testing.

tremor were analyzed in 4-Hz frequency bands between 2

Results and 29 Hz, and the results are shown in the Table.

The scores for the 32 acutely anxious subjects were Comment

tested by a split-plot analysis of variance, variation The results support the view that there is little qual¬

within subjects being estimated against residual variance, itative difference between anxious and normal tremors.

with between-subject variance removed. The scores for The changes in tremor that occur in anxiety are consistent

the chronically anxious patients and control subjects were with increased secretion of catecholamines, particularly

exposed to a simple one-way analysis of variance. adrenaline. It is now well established that there is a rise in

Tremor profiles for the groups are illustrated (Fig 2 and the level of circulating catecholamines during anxiety,1012

3). and that catecholamines increase the amplitude of physi¬

Although the psychiatric patients had the most severe ological tremor.11 As isoproterenol is itself a cate-

tremor, the pattern shown for acute and chronic anxiety is cholamine, it is notable that when this was given together

essentially the same. There is an increase in tremor over with electric shocks the pattern of tremor was very sim¬

the physiological range (6 to 14 Hz), but little difference at ilar to that in other stress situations (Table). There are

other frequencies. Analysis of the peak frequency, mea- other factors, possibly cortical in origin and certainly in-

5l

4-

Shocks alone

At rest

1-

0J

10 12 14 16 18 20

Frequency, Hz

Fig 2.—Tremor in acute anxiety. For simplicity, results for only one stress and rest situation are shown.

Fig 3.—Tremor in chronic anxiety.

6i

Patients

Control subjects

1-

0-1

16

Frequency, Hz

Downloaded From: http://archpsyc.jamanetwork.com/pdfaccess.ashx?url=/data/journals/psych/12251/ by a University of California - San Diego User on 01/25/2017

Frequency Band Analysis of Tremor*

Acute Anxiety

Chronic Anxiety

Tremor Shock and

Frequency, Shock Isopro- Control

Hz Rest Alone terenol Phobia Rest F Ratio Subjects Patients F Ratio

2- 5 4.60 4.19 4.39 4.36 4.01' 0.13 4.24 7.69 3.53

6- 9 11.77 12.39 13.32 12.35 11.25 2.55t 11.60 17.75 11.28t

10-13 9.86 10.56 10.80 10.33 9.65 0.97 9.29 15.02 15.73§

14-17 2.40 1.81 1.90 1.70 1.67 0.42 0.99 5.88 14.49§

18-21 1.16 0.64 1.30 0.67 0.65 0.97 0.33 2.51 3.35

22-25 0.90 0.53 1.19 0.77 0.93 0.83 0.71 2.73 2.71

26-29 0.67 0.58 0.79 0.42 0.90 0.61 0.24 2.12 2.85

* The figures given are in log, units,

t <.05.

* P<.01.

§ P<.001.

dependent of catecholamines, that may affect tremor am¬ The classification of tremors is still not a satisfactory

plitude,11 and these may be responsible for some of the dif¬ one and we have advanced little since Charcot's time. It is

ferences between the two studies. For example, the now clear that classification based on frequency is of lim¬

relatively greater proportion of faster tremor in the 10- to ited value. As far as anxiety is concerned it would seem

17-Hz range in chronic anxiety is not shown in acute anxi¬ preferable to confine descriptions of tremor to terms of

ety (Table). This corroborates, to some extent, previous quantity instead of suggesting that there are qualitative

suggestions of increased tremor at faster frequencies in differences that distinguish it from other types of tremor.

anxious patients.11"' Terms that imply that there is such a difference, such as

At frequencies above 17 Hz, anxiety has little effect on "coarse" and "fine," are misleading; they imply differ¬

tremor. The subsidiary peak at 24 to 27 Hz has been noted ences in frequency that do not exist.

before,"117 and may be due to local factors such as intrinsic

finger tremor. It certainly does not appear to have any This work was carried out while Dr. Tyrer had a Medical Research Coun¬

clinical importance. cil Clinical Research Fellowship.

References

1. Marey EJ: Du Mouvement dans les Fonctions de la Vie. 10. von Euler US, Lundberg J: Effect of flying on the epineph-

Paris, Germer Bailli\l=e`\re,1868, p 148. rine excretion in air force personnel. J Appl Physiol 6:551-555,

2. Charcot JM: Clinical Lectures on Diseases of the Nervous 1954.

System. T Savill (trans), London, New Sydenham Society, 1889, vol 11. Levi L: The urinary output of adrenaline and noradrenaline

3, pp 185-187. during pleasant and unpleasant emotional states. Psychosom Med

3. Sch\l=a"\ferEA, Canney HEL, Tunstall JO: On the rhythm of 27:80-85, 1965.

muscular response to volitional impulses in man. J Physiol (Lond) 12. Edmondson HD, Roscoe B, Vickers MD: Biochemical evi-

7:111-117, 1886. dence of anxiety in dental patients. Br Med J 4:7-9, 1972.

4. Graham JDP: Static tremor in anxiety states. J Neurol 13. Marsden CD, et al: Peripheral beta-adrenergic receptors

Neurosurg Psychiatry 8:57-60, 1945. concerned with tremor. Clin Sci 33:53-65, 1967.

5. Redfearn JWT: Normal and neurotic tremors. J Neurol 14. Marsden CD, Owen DAL: Mechanisms underlying emo-

Neurosurg Psychiatry 20:302-313, 1957. tional variation in Parkinsonian tremor. Neurology 17:711-715,

6. Carrie JRG: Sex differences in the limb tremor of morbidly 1967.

anxious patients. Br J Psychiatry 113:1265-1266, 1967. 15. Lippold OCJ, Redfearn JWT, Vuco J: The frequency analy-

7. Marsden CD, et al: Variation in human physiological finger sis of tremor in normal and thyrotoxic subjects. Clin Sci 18:587-

tremor, with particular reference to change in age. Electroenceph- 595, 1959.

alogr Clin Neurophysiol 27:169-178, 1969. 16. Randall JE, Stiles RN: Power spectral analysis of finger ac-

8. Blackman RB, Tukey JW: The Measurement of Power celeration tremor. J Appl Physiol 19:357-360, 1964.

Spectra. New York, Dover Publications Inc, 1959. 17. Stiles RN, Randall JE: Mechanical factors in human tremor

9. Schachter S, Singer J: Cognitive, social and physiological de- frequency. J Appl Physiol 23:324-330, 1967.

terminants of emotional state. Psychol Rev 69:379-397, 1962.

Downloaded From: http://archpsyc.jamanetwork.com/pdfaccess.ashx?url=/data/journals/psych/12251/ by a University of California - San Diego User on 01/25/2017

You might also like

- Hypnosis in The Emergency Department BIERMANDocument5 pagesHypnosis in The Emergency Department BIERMANAyoub LilouNo ratings yet

- What Is Healing Energy - Part 3 Silent PulsesDocument11 pagesWhat Is Healing Energy - Part 3 Silent PulsesDianaNo ratings yet

- Unit IG2: Risk Assessment Part 1: BackgroundDocument17 pagesUnit IG2: Risk Assessment Part 1: BackgroundStven Smith100% (6)

- Essential TremorDocument9 pagesEssential TremorsolecitodelmarNo ratings yet

- Reflections On The Ether and Some Notes On The Convergence Between Homoeopathy and Radionics PDFDocument18 pagesReflections On The Ether and Some Notes On The Convergence Between Homoeopathy and Radionics PDFisaiahNo ratings yet

- FELINE-Peritoneopericardial Diaphramatic Hernia in CatsDocument13 pagesFELINE-Peritoneopericardial Diaphramatic Hernia in Catstaner_soysuren100% (1)

- Theories of Pain: From Specificity To Gate Control: ReviewDocument8 pagesTheories of Pain: From Specificity To Gate Control: ReviewmustafasacarNo ratings yet

- A Review of Psi Activity in The DNA PDFDocument8 pagesA Review of Psi Activity in The DNA PDFIvan KonarNo ratings yet

- Cpydp AbyipDocument7 pagesCpydp AbyipRod Michael BadianNo ratings yet

- Trixie Ann C. Salasibar BSN 2B-2DDocument6 pagesTrixie Ann C. Salasibar BSN 2B-2Dann camposNo ratings yet

- Lavender Essential Oil PDFDocument2 pagesLavender Essential Oil PDFalaskaessentialsNo ratings yet

- Franks EtherDocument18 pagesFranks EtherJeremy PriceNo ratings yet

- Scofield Mind in RadionicsDocument17 pagesScofield Mind in Radionicshassock100% (3)

- Intuition, Telepathy, and Interspecies Communication PDFDocument8 pagesIntuition, Telepathy, and Interspecies Communication PDFBeddek AmiroucheNo ratings yet

- Human RelationsDocument3 pagesHuman Relationsarianamistry5No ratings yet

- Essential Tremor: Clinical PracticeDocument9 pagesEssential Tremor: Clinical PracticeDaniel Torres100% (1)

- Dr. S.K. Haldar's Lectures On Industrial Health For AFIH Students - OHS Modern ConceptDocument3 pagesDr. S.K. Haldar's Lectures On Industrial Health For AFIH Students - OHS Modern ConceptDr. Prakash KulkarniNo ratings yet

- Clinical Osteopathic Approaches To Emotions: - Kenneth Lossing DO - AAO Convocation 2016Document57 pagesClinical Osteopathic Approaches To Emotions: - Kenneth Lossing DO - AAO Convocation 2016Diana SchlittlerNo ratings yet

- NEW CHECKLIST Oropharyngeal SuctioningDocument2 pagesNEW CHECKLIST Oropharyngeal SuctioningDan Dan Manaois100% (1)

- Introduction of Community MedicineDocument111 pagesIntroduction of Community MedicineSanjeet SahNo ratings yet

- From Biologic Research Laboratory, University of DenverDocument6 pagesFrom Biologic Research Laboratory, University of DenverDr TONOUGBA danielNo ratings yet

- Ouantitative Assessment of Tactile Allodynia in The Rat PawDocument9 pagesOuantitative Assessment of Tactile Allodynia in The Rat PawAskarNo ratings yet

- Sleep Dysfunction: Rett SyndromeDocument7 pagesSleep Dysfunction: Rett SyndromeErika PratistaNo ratings yet

- Correlates of in Rats: Physiological Prolonged Sleep DeprivationDocument3 pagesCorrelates of in Rats: Physiological Prolonged Sleep DeprivationJuan Vale TrujilloNo ratings yet

- Tremor: Clinical Phenomenology and Assessment Techniques: ReviewDocument15 pagesTremor: Clinical Phenomenology and Assessment Techniques: ReviewSomente CoisasNo ratings yet

- Miotto - Tremor Recording ReviewDocument20 pagesMiotto - Tremor Recording ReviewVrutang ShahNo ratings yet

- Anger-Paranoia Comm SbaDocument5 pagesAnger-Paranoia Comm SbaJulia ObioraNo ratings yet

- Mebritish: 1966 Tetanus-HendrickseDocument4 pagesMebritish: 1966 Tetanus-HendrickseRamadhan Andhika PutraNo ratings yet

- Positive and Negative Schizophrenic Symptoms, Attention, and Information ProcessingDocument12 pagesPositive and Negative Schizophrenic Symptoms, Attention, and Information ProcessingcarolNo ratings yet

- 14 HangingsDocument4 pages14 Hangingsडा. सत्यदेव त्यागी आर्यNo ratings yet

- Foremed - DEC 2010 PDFDocument4 pagesForemed - DEC 2010 PDFAnamika DasNo ratings yet

- Vibration Stress and The Autonomic Nervous SystemDocument8 pagesVibration Stress and The Autonomic Nervous SystemGuillermo923No ratings yet

- JPSP Aron and Aron 97 Sensitivity Vs I and N PDFDocument24 pagesJPSP Aron and Aron 97 Sensitivity Vs I and N PDFInés DoradoNo ratings yet

- Status Epilepticus: Correspondence: Hpg9v@virginia - EduDocument12 pagesStatus Epilepticus: Correspondence: Hpg9v@virginia - EduGerardo Lerma BurciagaNo ratings yet

- Dementia FrontotemporalDocument24 pagesDementia FrontotemporalTeologia GamalielNo ratings yet

- Sensory Processing Sensitivity AronDocument24 pagesSensory Processing Sensitivity AronagustinaNo ratings yet

- Delirium Review 2002Document6 pagesDelirium Review 2002Naxhiely Fuentes JiménezNo ratings yet

- Reimers 2007Document8 pagesReimers 2007Joanna Riera MNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 s15678237612312 PDFDocument1 page1 s2.0 s15678237612312 PDFAnonymous mIAyZ4TNo ratings yet

- The Fascial Distortion Model BookDocument10 pagesThe Fascial Distortion Model BooksimonyanNo ratings yet

- Ketamine-Peril and Promise - HTMLDocument10 pagesKetamine-Peril and Promise - HTMLGlibNo ratings yet

- Achilles Reflex Time and Sympathetic ToneDocument5 pagesAchilles Reflex Time and Sympathetic ToneBudi AthAnza SuhartonoNo ratings yet

- Opioid Dystonia 1Document1 pageOpioid Dystonia 1PuneetNo ratings yet

- Pain Threshold Is Reduced in DepressionDocument4 pagesPain Threshold Is Reduced in DepressionAmer WasimNo ratings yet

- Hypnotic Depth and Basal Skin Resistance: Abstract: 2 2Document12 pagesHypnotic Depth and Basal Skin Resistance: Abstract: 2 2Bia&Eva SURPRISE SONGSNo ratings yet

- Worldwalking - Latest VDocument28 pagesWorldwalking - Latest Vekamitra-nusantaraNo ratings yet

- Diagnosing Carpal Tunnel Syndrome: The PatientDocument4 pagesDiagnosing Carpal Tunnel Syndrome: The Patienthelenotatiana24No ratings yet

- Pranormal Experience and BeleifDocument6 pagesPranormal Experience and BeleifRené GallardoNo ratings yet

- Brain: Reality of Auditory Verbal HallucinationsDocument8 pagesBrain: Reality of Auditory Verbal HallucinationsBebby Amalia sunaryoNo ratings yet

- Where Do Voices Come FromDocument5 pagesWhere Do Voices Come FromSudipta Kumar DeNo ratings yet

- State of The Art: The Biology of Fear-And Anxiety-Related BehaviorsDocument19 pagesState of The Art: The Biology of Fear-And Anxiety-Related BehaviorsHarumWulansariNo ratings yet

- Sensing and Perceiving 4.1Document9 pagesSensing and Perceiving 4.1Toheeb SholaNo ratings yet

- Probing The Stress and Depression Circuits With A Disease GeneDocument4 pagesProbing The Stress and Depression Circuits With A Disease GeneAldo VictoriaNo ratings yet

- Ultrasound Therapy CTADocument5 pagesUltrasound Therapy CTAmitchNo ratings yet

- Telomere Poster MSRF - AdrienneMaguireDocument1 pageTelomere Poster MSRF - AdrienneMaguireg1870186No ratings yet

- Current Issues in Tourette SyndromeDocument13 pagesCurrent Issues in Tourette SyndromeVasanth KolurNo ratings yet

- The Two-Syndrome. Timothy J. CrowDocument16 pagesThe Two-Syndrome. Timothy J. CrowQwerty QwertyNo ratings yet

- Div Class Title Decreased Heart Rate Variability During Emotion Regulation in Subjects at Risk For Psychopathology DivDocument9 pagesDiv Class Title Decreased Heart Rate Variability During Emotion Regulation in Subjects at Risk For Psychopathology DivP AlexiaNo ratings yet

- 362 FullDocument6 pages362 FullMohanBabuNo ratings yet

- Music and Mental Illness in Search of Lost Time From "Demonic Possession" To Anti-N-Methyl - Aspartate Receptor EncephalitisDocument2 pagesMusic and Mental Illness in Search of Lost Time From "Demonic Possession" To Anti-N-Methyl - Aspartate Receptor EncephalitisivanNo ratings yet

- Recurrent Seizures in Cats: 1. Diagnostic Approach - When Is It Idiopathic Epilepsy?Document13 pagesRecurrent Seizures in Cats: 1. Diagnostic Approach - When Is It Idiopathic Epilepsy?Rifia FaniNo ratings yet

- Malmo 1949Document16 pagesMalmo 1949Víctor FuentesNo ratings yet

- 2001 The First-Night Effect May Last More Than One NightDocument8 pages2001 The First-Night Effect May Last More Than One NightpsicosmosNo ratings yet

- Strata 1999Document2 pagesStrata 1999Agustin LopezNo ratings yet

- A Practical Guide To The Differential Diagnosis of Tremor: Jane E Alty, Peter A KempsterDocument8 pagesA Practical Guide To The Differential Diagnosis of Tremor: Jane E Alty, Peter A KempsterBmNo ratings yet

- Spasmodic Torticollis - Review of 220 Patients: P. Rondot, M.P. Marchand and G. DellatolasDocument9 pagesSpasmodic Torticollis - Review of 220 Patients: P. Rondot, M.P. Marchand and G. Dellatolastiffanybell04No ratings yet

- Montes N - Philosophy PaperDocument10 pagesMontes N - Philosophy Paperapi-652798681No ratings yet

- Analysis of Nutrition and Nutritional Status of HaDocument11 pagesAnalysis of Nutrition and Nutritional Status of HaVione rizkiNo ratings yet

- MODULE 7 - CAPABILITY AND CAPACITY BUILDING IN DISASTER PREPAREDNESSDocument7 pagesMODULE 7 - CAPABILITY AND CAPACITY BUILDING IN DISASTER PREPAREDNESSKaguraNo ratings yet

- FX 100 MSDS 031213Document5 pagesFX 100 MSDS 031213Achraf Ben DhifallahNo ratings yet

- NRSG 428lDocument4 pagesNRSG 428lapi-2778422060% (1)

- News Structuralist 004Document2 pagesNews Structuralist 004HofstraUniversityNo ratings yet

- Labor ExerciseDocument2 pagesLabor ExerciseDon RaulNo ratings yet

- Dress Codes For Postgraduate Medical and Dental Recruitment, Training and AssessmentDocument4 pagesDress Codes For Postgraduate Medical and Dental Recruitment, Training and AssessmentAgilan KaliappanNo ratings yet

- Bio Medical Waste Authorization Certificate: Haryana State Pollution Control BoardDocument3 pagesBio Medical Waste Authorization Certificate: Haryana State Pollution Control BoardManishNo ratings yet

- Letter of Continued Interest - Rhodes CollegeDocument2 pagesLetter of Continued Interest - Rhodes CollegedayieltskhonglaytienchetlienNo ratings yet

- Module 6Document26 pagesModule 6xtnreyesNo ratings yet

- Cheyenne Scott Final ResumeDocument3 pagesCheyenne Scott Final Resumeapi-267328340No ratings yet

- Memory Loss & 10 Early Signs of Alzheimer's - Alzheimer's AssociationDocument9 pagesMemory Loss & 10 Early Signs of Alzheimer's - Alzheimer's AssociationRatnaPrasadNalamNo ratings yet

- Reproduction 8 QP 5090Document10 pagesReproduction 8 QP 5090sunflower rantsNo ratings yet

- SuppressionDocument9 pagesSuppressiondharmishthavala41No ratings yet

- COVID 19 in Kidney Transplant RecipientsDocument11 pagesCOVID 19 in Kidney Transplant RecipientsDouglas SantosNo ratings yet

- Hyperthermia and HypothermiaDocument5 pagesHyperthermia and HypothermiaDesign worldNo ratings yet

- Amblyopia eDocument3 pagesAmblyopia eIeien MuthmainnahNo ratings yet

- Sharps Injury Checklist: TrainingDocument2 pagesSharps Injury Checklist: TrainingjosiasNo ratings yet

- Canmedaj01540 0049Document4 pagesCanmedaj01540 0049ImanNo ratings yet

- SpeechDocument1 pageSpeechSheryl BorromeoNo ratings yet

- RA-015139 PHYSICIAN Iloilo 10-2022Document29 pagesRA-015139 PHYSICIAN Iloilo 10-2022Marlon BaltarNo ratings yet