Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Ball BallBrown1968 2014

Ball BallBrown1968 2014

Uploaded by

amangoel875Original Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Ball BallBrown1968 2014

Ball BallBrown1968 2014

Uploaded by

amangoel875Copyright:

Available Formats

Ball and Brown (1968): A Retrospective

Author(s): Ray Ball and Philip R. Brown

Source: The Accounting Review , JANUARY 2014, Vol. 89, No. 1 (JANUARY 2014), pp. 1-

26

Published by: American Accounting Association

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/24468510

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

American Accounting Association is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend

access to The Accounting Review

This content downloaded from

202.174.120.210 on Thu, 11 Jan 2024 16:19:37 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

THE ACCOUNTING REVIEW American Accounting Association

Vol. 89, No. 1 DOI: 10.2308/accr-50604

2014

pp. 1-26

Ball and Brown (1968): A Retrospective

Ray Ball

The University of Chicago

Philip R. Brown

The University of New South Wales and The University of Western Australia

ABSTRACT : This essay provides a retrospective view on our co-authored paper, Ball and

Brown (1968). The retrospective was commissioned by Gregory B. Waymire, then President

of the American Accounting Association. It describes how we both came to be Ph.D. students

at The University of Chicago and set about researching the relation between earnings and

share prices. It outlines the background against which we conducted the research, including

the largely a priori accounting research literature at the time and the electric atmosphere and

radical new ideas then in full bloom at Chicago. We describe some of the principal research

choices we made, and their strengths and weaknesses. We also describe the reception our

research received and how the related literature subsequently unfolded.

Keywords: Ball-Brown; earnings; usefulness; timeliness; anomalies; event study.

L INTRODUCTION

of Accounting Income Numbers," was among the most influential research papers published

Undoubtedly the Ball and Brown (1968; hereafter, BB68) paper, "An Empirical Evaluation

in accounting during the last century. As the authors of that paper, we were commissioned by

Gregory B. Waymire, then President of the American Accounting Association, to look back on our

contribution, given the benefit of hindsight and the evolution of the research literature over the past 45

years.1 To fulfil this commission, we will address a series of questions. We are both Australians, so how

This essay was commissioned by Gregory B. Waymire, American Accounting Association 2012 President, and is based

on our joint Presidential Scholar Address, entitled "Ball and Brown (1968): A Seed that Made a Difference," at the 2012

AAA Annual Meeting in Washington, DC. We express our appreciation to Greg for this opportunity to tell our story. We

also appreciate the comments made on earlier drafts by Sudipta Basu, Peter Easton, John Harry Evans III, Paul Griffin,

Richard Leftwich, Christian Leuz, Stephen Penman, Lakshmanan Shivakumar, Doug Skinner, James Wahlen, Greg

Waymire, and Stephen Zeff. We thank The University of Chicago Booth School of Business for permission to reproduce

Figure 1 from the Journal of Accounting Research.

This commentary, based on a lecture at the 2012 American Accounting Association Annual Meeting in Washington,

D.C., was invited by Senior Editor John Harry Evans III, consistent with the AAA Executive Committee's goal to

promote broad dissemination of the AAA Presidential Scholar Lecture.

Editor's note: Invited.

Submitted: July 2013

Accepted: August 2013

Published Online: August 2013

cf. Brown (1989).

This content downloaded from

202.174.120.210 on Thu, 11 Jan 2024 16:19:37 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

2 Ball and Brown

did we both come

BB68? What did w

accounting resear

researchers? Looki

Has BB68 been pr

Our reflections ar

Regardless of the

the literature that followed are our own.

II. HOW WE CAME TO BE PH.D. STUDENTS AT THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO

Our backgrounds have a great deal in common. We both grew up in Sydney, Aust

post-WWH period. Our major educational influences, in terms of both subject m

personalities, are remarkably similar. So we came to be Ph.D. students at The Universit

by similar routes.

Phil Brown began his university studies as a part-time accountancy student at wh

The University of New South Wales (UNSW) in Sydney, in the late 1950s. At the end

year he enrolled in the University's accountancy honours program, which was condu

late William J. McK. (Bill) Stewart. Bill Stewart was a remarkable academic for th

having established links with the University of California, Berkeley, The University

and Cornell University. Honours students completed four-year degrees (normal "pass

involved only three years of full-time study), and for the first three years they atten

classes as the pass degree students. Honours students also participated in small weekly

often held in Bill Stewart's office, where the current literature, including book

regarded as the accounting classics,2 was discussed in great detail. In the fourth year

students undertook further advanced studies and wrote a reasonably substantial

theses dealt with some accounting research question of interest to academics at the t

During the course of his honours degree, Phil decided to pursue a career as an acc

academic. That was understood to require a Ph.D., and at the lime it was not realistic

to complete a high-quality Ph.D. in accounting at an Australian university. Neit

feasible, it seems, for a young Australian to complete a Ph.D. in accounting at

hallowed British universities, which often welcomed bright foreign students fro

wealth countries who wished to study other disciplines. Since Bill Stewart had

Chicago and Cornell, he recommended Phil apply there. Serendipitously, he chos

Phil enrolled in Chicago's Ph.D. program in September 1963. Based on the strength

UNSW accounting honours program, he was exempted from all accounting courses othe

Ph.D. seminar and was now free to pursue courses in economics and finance. A corpo

course taught by Mert Miller exposed Phil to the Miller-Modigliani view of the role

dividends, and growth opportunities in the valuation of the firm. Phil was appointed an

Chicago in 1966, which was the position he held when Ray joined the Chicago Ph.D. p

September.4

Ray also completed an accountancy degree at UNSW, where he too was invited to join the

honours program by Bill Stewart. He became immersed in accounting theory, and found that, in

2 See Ball and Brown (1968, footnote 1) for a list of some of the readings.

3 Phil's honours thesis was titled "Depreciation" while Ray's was "On Objectivity in Accounting."

4 Ross Watts, who came from a similar background (including an honours program strongly influenced by Bill

Stewart), entered the Chicago Ph.D. program the same year as Ray. Another Australian, Bob Officer, joined the

program in 1968.

\Γ5Association

Accounting The Accounting Review

β

^ January 2014

This content downloaded from

202.174.120.210 on Thu, 11 Jan 2024 16:19:37 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Ball and Brown (1968): A Retrospective 3

addition to doing well at it, he thoroughly enjo

articles on accounting theory in a student journal

for a Ph.D. in the U.S. was likewise influenced b

We both owe much to Bill Stewart, as do others

personality, and his deep knowledge of accou

literatures. Bill had a gift for stimulating his b

accounting and accounting theory, the two of us

not be known except by anyone who searches out

and 1960s, but his legacy is his effect on a gener

Some sense of the times can be gleaned from

for Ray to decide where to study, Bill had beco

recently had acquired at Chicago, and of its the

market efficiency in particular. Neither was he

Phil's interests in economics and finance wer

program, where accounting was not being ov

accounting theory remained in vogue, but ina

dynamic and exciting. That impression was stre

in Chicago. So Ray accepted Chicago's offer.

On arriving, Ray also was exempted from

seminar which, he discovered, covered the same

years 2 through 4 of the UNSW program, b

Consequently, the seminar required little work,

finance—and for research.

Not long after Ray's arrival in Fall 1966, we decided to team up, and the collaboration began.

Together we have published nine peer-reviewed articles, four other articles, and an edited book of

readings. Of course, in hindsight BB68 was our most successful project.

HI. BACKGROUND TO THE RESEARCH

In this section, we describe the background against which BB68 emerged, in

accounting literature at the time, the exciting new ideas being fomented at Chicago, an

this entailed between two world views.

The Accounting Literature at the Time

From today's perspective it is difficult to comprehend the background against which Ball and

Brown (1968) emerged. Almost five decades have passed since we began the research in 1966.

During that interval, the accounting literature has changed dramatically, and the ideas taught in

doctoral programs have been so radically transformed, that the literature when we started must now

seem like another world entirely.

To understand the paper and its impact, it helps to realize that the dominant accounting

literature in the mid-1960s was predominantly a priori in nature. Research topics ranged from more

esoteric topics, such as the nature of accounting theory and the difference between postulates and

principles in accounting, to the mundane, such as whether deferred taxes are a liability. Influential

"theory" texts included Canning (1929), Edwards and Bell (1961), and Chambers (1966), whose

verbal style bore little resemblance to the modem "theory" literature.

The literature we inherited had reached two central conclusions:

1. Financial statement information prepared under existing reporting rules is meaningless; and

2. Radical changes in the nature of financial statement information are required.

The Accounting

°

Review ^5 AcccumTn?

Association

January 2014 ~

This content downloaded from

202.174.120.210 on Thu, 11 Jan 2024 16:19:37 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

4 Ball and Brown

These conclusions

Lecture by Ray C

(Chambers 1976;

It is futile to exp

are represented

payables), by his

depreciated histo

such other odd a

inventories). Agg

nothing in the n

"dated market va

amounts aggrega

... only a system

intelligible figur

another; and tha

money equivalen

andthe income a

general capacity

suchfinancial ar

Variations of the

agreement on the

meaningless becau

proverbial apples

second conclusion

There were advoc

prices), realizable

general price cha

specific prices ch

status quo.

Dyckman and Ze

normative policy

between 37 and 7

year. Some appre

literature of the

Wheeler's objecti

5 The first footnot

Canning (1929, 99)

the sense that it con

"Net Income Has N

income can be maint

expresses the mag

numerical value ha

[revenue], the met

[expenses] the meas

the original). The

meaning recently r

aggregate of individ

The aggregate of f

ο Accounting The Accounting Review

V A— january 2014

This content downloaded from

202.174.120.210 on Thu, 11 Jan 2024 16:19:37 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Ball and Brown (1968): A Retrospective 5

and research in perspective." At the time, Wheeler

Associate Dean for Academic Affairs of the G

University of California, Berkeley. The essay was

Review. Furthermore, the conclusions reached w

(Wheeler 1970, 2):

I wrote to a number of accountants who have

development of accounting theory to get fr

developments ... Their ideas, those of graduate

the subject and the writings of countless accoun

utilized.

After considering all these sources, Wheeler reach

1970, 8):

I should like to conclude by looking at accounting theory and research needs for the future.

General expositions of theory differentiate between descriptive and normative theory, but

it is my view that only the latter is relevant for accounting.

No reference was made to collecting comprehensive empirical data on the actual properties of

financial statements prepared under conventional rules, or data on how those properties might be

changed under different alternative schemes. Collecting evidence was not an important enough

priority for Wheeler or for any of the authorities he approached to even deserve a mention. In this

regard, Wheeler's views on what was important in accounting research mirrored the literature,

which was based almost entirely on a priori reasoning.

General Absence of Systematic, Comprehensive Evidence for Extant Theory

We were aware of no systematic, comprehensive evidence offered in the prior literature to

support the two central conclusions outlined above. Of the leading theorists, Chambers alone

provided empirical support for his views, but even those observations were largely pathological

cases in which financial statements had been shown ex post to be imperfect predictors of

subsequently revealed valuations in unusual circumstances, such as bankruptcies, accounting

scandals, takeovers or subsequent asset revaluations. His position, stated partly in response to our

paper, was (Chambers 1973, 165):

It did not seem to me, and it still does not seem to me, to be necessary to apply any

elaborate statistical processes to the analysis of these cases. Every company is unique; its

history, its financial and trading strength, its vulnerability to bidders, its relations with

affiliates and financiers and its work force, are unique.

Much can be learned from pathological cases, but one has to be careful not to over-generalize.

An immediate problem is selection bias. If one's hypothesis is that conventionally prepared

financial statements provide imperfect measures of value, then selecting pathological cases that are

consistent with that hypothesis is equivalent to truncating the sample on the basis of the dependent

variable, which generates biased inferences about the population. But the literature of that era

proposed radical changes in reporting for the population in its entirety. To make the point a different

way, it would be equally invalid to conclude, from an analysis of cases selected on the basis that

their financial statements had been excellent predictors of ex post valuations, that no changes to

reporting should be made.

A second problem with this approach is that it provided no evidence that the proposed radical

changes in reporting would improve social welfare. There was no systematic evidence on the major

The Accounting Review Ό

American

r. ^ Accounting

Association

January 2014

This content downloaded from

202.174.120.210 on Thu, 11 Jan 2024 16:19:37 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

6 Ball and Brown

uses to which fin

those uses. There

of bankruptcies,

be imperfect. In

engenders more

manipulation, as

In this regard, t

fallacy" that Dem

accounting) in ge

The view that n

choice as betwee

This nirvana app

which the relev

practice, those w

the ideal and the

(Demsetz 1969, 1

Inother words, d

that they are ine

A related proble

pathological case

were subsequentl

optimal (Anderso

A final limitatio

other informatio

alongside accoun

efficient aggregat

source, financial

Absence of Sys

Strange as it ma

fruitful to invest

likely reason is d

accounting rese

accounting measu

In sum, for som

change, utilizin

propositions.

Important Cont

We do not wish

without merit. In

age in the history

among them bein

One may question

major body of th

crucial stage in t

ΪΊ A^intTng The Accounting Review

Association

January 2014

This content downloaded from

202.174.120.210 on Thu, 11 Jan 2024 16:19:37 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Ball and Brown (1968): A Retrospective 7

Echoes of the great debates of the "golden age"

debates on the role of "fair value" accounting. F

"continuously contemporary accounting (Co

testimony to an enduring influence of that litera

Furthermore, the prior literature provided us w

statement information prepared under existing r

aggregating amounts that are not homogeneous.

with a prediction at the core of the prior literatu

New Ideas and Methods in Economics and Fi

The atmosphere at Chicago was electric when w

crackled with innovation. The general attitude to

workshops—a Chicago staple—were frequent

seminar, largely uninterrupted but with some tim

rude awakening within minutes of starting.

New ideas about markets were being devel

economics and finance.7 In economics, a constant

their evolved institutional structures. This line o

Friedman, Stigler, Coase (all of whom became N

became mainstream economics, but was exciting

another Nobel Laureate, had co-pioneered the int

form of the Miller-Modigliani dividend and debt

Of particular importance was the work bein

prices. Fama (1965a, 1965b) made the concept

function of information flows. Taken for grant

thinking. A corresponding development was the

(1969) of what is now known as "event time."8 T

stock prices as a function of information flows

breakthrough. It is difficult to over-estimate th

design to our study and to the understanding o

information and prices resides in calendar time

financial press observes share prices changing in

events, such as news about international and do

statistics, takeovers, management changes, prod

manager and analyst forecasts, and earnings

(1969) inverted the lay perspective: for a given

they observed prices changing at a large cros

subsequently became known, generically, as a

A final but important ingredient of the back

confronting ideas with data. To that end, the C

established at Chicago in 1961, and completed th

Kuhn (1969, 65; emphasis in the original) states that

knowing with precision what he should expect, is able

Accounting students of the period included Bill Beav

Baruch Lev, Bill Voss, and Ross Watts. Finance studen

Roll, and Myron Scholes.

While published in the year after BB68, Fama et al

references and at various points in the paper (footnot

The Accounting Review Ό i

_ _ _ Association

I American

' Accounting

January 2014 ^

This content downloaded from

202.174.120.210 on Thu, 11 Jan 2024 16:19:37 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

8 Ball and Brown

Starting with F

floodgatesto a to

widely recognize

The emphasis pl

Sidney Davidson

and George Sorte

stressed impo the

Accounting was o

proceedings were

Preface to the fi

effectively by in

evidence as well a

Nevertheless, ou

only natural. We

and teaching, and

research. One acc

(earnings) with g

the finance facult

time were like-m

A Clash of World Views

We were brash young risk-takers who were well schooled in two fundamentally different wa

of thinking, and itching to put them to the test in an environment that encouraged just that.

We had been well educated at UNSW in all the schools of thought that concluded financial

statement information was in need of radical change, and knew that literature well. But whe

exposed to the thinking in economics and finance at Chicago, it had become natural to question

conclusions drawn in the existing literature, to see flaws in its reasoning, and to look fo

empirical test.

At Chicago we had learned a fundamental respect for markets and their evolved institutional

structures. It was, to us, only natural to ask if financial statement information is so meaningless,

why have substantial resources been put into producing it for so many years? Why has financial

reporting under traditional accounting rules evolved and survived for so long as an integral part of

the institutional structure when it allegedly is so deficient? Are the basic conclusions reached in the

literature correct?

The prevailing reasoning began to seem flawed as well. Is a number reported in a financial

statement necessarily meaningless just because it is an aggregation of numbers calculated using

methods that are not completely homogeneous? Commonly used test scores such as IQ, SAT,

and GMAT scores are aggregations of answers to heterogeneous questions, verbal and

quantitative, short and long, involving different tasks such as identifying sequences, analogies

and shapes, in addition to which the aggregate scoring is a function of the number of questions

attempted as well as the number correctly answered. Nevertheless, we use these scores as

imperfect indicators, and employ them in conjunction with other information, but we do not

reject them as totally meaningless. Similarly, we grade our students in an exam by aggregating

scores on heterogeneous questions, we assign grades in our subjects by aggregating these exam

scores along with scores on essays, projects, class participation and the like, and we aggregate

grades across heterogeneous subjects such as Accounting, Strategic Management, Statistics and

Marketing to obtain program-wide GPAs, three actions that indicate we do not view such

aggregations as devoid of meaning. We tend to regard them as imperfect indicators, to be used in

Ο ArcwntTng The Accounting Review

Association

January 2014

This content downloaded from

202.174.120.210 on Thu, 11 Jan 2024 16:19:37 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Ball and Brown (1968): A Retrospective 9

conjunction with other information. Why is finan

totally meaningless because it aggregates calculatio

So we set about to challenge the basic proposition

But what test of those propositions could we devise

in retrospect, but it required several research design

are described below. In making those choices we

precedent was Fama et al. (1969), but even that

answers we needed. We cannot recall receiving any

students, with the sole exception of Myron Schole

Nobel Laureate, who is the only academic mention

IV. OUR RESULTS AND WHAT WE CONCLUDED

The basic research question

Our fundamental research question was simply, "Are accounting income numbers u

Two derivative questions are, "Useful to whom?" and "Useful for what purpose?" Our p

summarized as, "An empirical evaluation of accounting income numbers requires agreem

what real-world outcome constitutes an appropriate test of usefulness. Because net inco

number of particular interest to investors, the outcome we use as a predictive criterio

investment decision as it is reflected in security prices" (BB68, 160). We considered

relevance and the timeliness of income announcements to equity markets, because, as w

"... usefulness could be impaired by deficiencies in either." The "useful to whom" and "

purpose" questions are fundamental to this line of enquiry and warrant rather more tho

sometimes they are given. We return to this point later, when we discuss the fact that

also depends on the user's perspective.

How Did We Address the Research Question (What Did We Do?)

We begin our answer to this question by noting that the Efficient Market Hypothesi

a core component of the BB68 research design. And why not? At Chicago, in those day

was an almost unchallenged view, particularly among the finance faculty and doctoral st

BB68 is what is now seen as an archetypal event study.10 While BB68 may well have b

first "modem" event study to be published, the first such study to be conducted was b

Fisher, Jensen, and Roll. Their paper, published in 1969, is about the way in which infor

captured in financial markets, and their "event" is a stock split. The event we ch

announcement of the annual accounting income number, or earnings for the year.

Because nobody had focused on earnings announcements in any detailed way be

analysts' earnings forecasts were not being systematically collated in any form accessi

9 The above argument, and our empirical tests of it, are related to the classic Ogden and Richards (1923

that words are connected with things "through their occurrence together ... in a context" and their o

(Ogden and Richards 1923, 270) that for a word to have meaning "requires that it form a context wit

experiences." Thus, the meaning to users of accounting numbers including earnings arises through th

contexts such as the stock market and is not a simple matter of their correspondence with an analytica

10 When we first presented the forerunner paper and talked about the possibility of undertaking BB68

participants strongly argued that we should investigate the BB68 question by including the BB6

forecast errors" in an expanded version of the Market Model of stock returns. We resisted that argum

reasons. The first is that we were chary about making the linearity assumption in a returns-earnings

Second, and more importantly, this approach did not sit well with the timeliness notion we

investigate.

The Accounting Review îSSÏmîie

January 2014 ^

This content downloaded from

202.174.120.210 on Thu, 11 Jan 2024 16:19:37 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

10 Ball and Brown

we had to work ou

We employed three

we called them. T

changes in prior ye

(2) a similar Mark

well described by a

the firm's earnings

firmwas stagnant

Market Model spec

stock returns, bu

Market Models. W

earnings changes

check, which is wh

in the estimation p

the earnings foreca

before the annual e

As an aside, we h

information perspe

want to take an info

affect stock prices

perspective and a va

distinction in this

(returns).

What We Found

We reported two principal results, summarized as follows:

The initial objective was to assess the usefulness of existing accounting income numbers

by examining their information content and timeliness ... Its content is ... considerable.

However, the annual income report does not rate highly as a timely medium. (BB68, 176)

In addition, we reported the anomalous result that "the relationship between the sign of the inc

forecast error and that of the stock return residual might have persisted for as long as two mo

beyond the month of the announcement" (BB68, 173). This section discusses each of these res

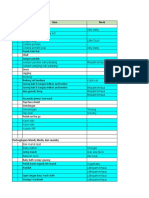

As the saying goes, "A picture is worth a thousand words."12 Figure 1 in BB68 is reprodu

below. The top half of Figure 1 depicts a company's stock price movements over the 12 mont

leading up to the announcement of the company's earnings (income) number for the y

conditional upon "good news" earnings being reported; the bottom half is for "bad news." Th

lines plot the averages of the market-adjusted stock price movements, which are expressed in t

form of an "Abnormal Performance Index," or API.

What were the answers to our initial research question? We can re-state the initial "usefulne

question in the form of one that is testable: "Is the newsworthy component of the annual earn

'1 In the forerunner paper we fitted the relation between the levels of annual earnings of the firm, its industry

the economy. We adopted a "changes" specification "because our method of analyzing the stock mark

reaction to income numbers presupposes the income forecast errors to be unpredictable at a minimum o

months prior to the announcement dates. This supposition is inappropriate when the errors are autocorrelate

(BB68, 166), as they are when the association is fitted in levels. At the time, a first differences specification w

standard econometric procedure for dealing with autocorrelation in the levels.

12 The saying's origin is obscure: http://www.phrases.org.uk/meanings/a-picture-is-worth-a-thousand-words.h

ΤΊ) «ccôurÂÎnq The Accounting Review

Association

January 2014

This content downloaded from

202.174.120.210 on Thu, 11 Jan 2024 16:19:37 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Ball and Brown (1968): A Retrospective 11

FIGURE 1

Abnormal Performance Indexes for Various Portfolios

3—i | | 1—i r- i—i I I i I I I ' I l" tl

1.12

1.10

Varioble 2

1X16

- ~ -it—

X'\ Yorioble 1

V

106

1.04 / , Vgriob!* ?

-8

-S 102

2

J NX Tq*ol«qmpl»7

0.98 V

\

:fo.*6

\

0.94 \

V

X

a92

•>

0.90

^ Vorjafeiel

Varioble 3

yorjpbV 1 F

0.88

i i > « > i Li i i i i i

-12

-12 -10

-10 -8

-8-6-4

-6 -4 -2

-2 0

0 2

2 4

4 6

6

Month

Month Relative

Relativeto

toAnnual

AnnualR

Source: Ball and Brown (1968).

number associated with stock p

perspective: because accounting ha

to produce, accounting as an econo

there was a demand for it. Our pri

American

The Accounting Review Accounting

Association

January 2014

This content downloaded from

202.174.120.210 on Thu, 11 Jan 2024 16:19:37 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

12 Ball and Brown

had not rejected t

wrong with our e

announcements we

We adopted an e

months to the end

of information

Information," or

Information (AI) b

explained using th

Assume the Effic

monthly informat

month-by-month

the annual income

way, the total ma

of the year leadin

start of each mon

went long or shor

Market Hypothesi

assume you are an

established your i

income number w

return the y over

was on average 0.1

today, every bit o

which under the

before the end of

is that, although

are interested in

on every stock, go

investment until 12 months later.

But what if we told you only the amount each stock would report as its annual earnings per

share in 12 months from now, and nothing else? Then you might wonder, "Hmm, I know what

earnings per share will be in 12 months' time, so what should I do today?" Recall we had three

models of the earnings "surprise" to simulate your decision and one of the three assumed

earnings followed a random walk. According to that model you would decide, "If earnings will

be higher this year (relative to last year), then I will go long, otherwise I will go short." If you

did so then over the course of the year, your market-adjusted return, labeled AI, would have been

about 0.08 averaged once again over all company-years in the BB68 sample. Can you see how

we brought these three numbers together? About three-quarters of the information released each

month over the course of the year is offsetting (TI is 0.731 but NI is 0.165, which is only a

quarter of the value of TI); and earnings per share captures about half the net (market-adjusted)

pricing effects of all information revealed over that same period (AI is 0.08, which is of the order

of half the value of NI).

But is the annual earnings number, as economically significant as it appears to be, also timely

as far as stock prices are concerned? Hardly. Around 85-90 percent of the price adjustment occurs

13 The calculation was more complicated than this paragraph indicates, but that is more a matter of detail at this

point.

ο Accounting The Accounting Review

V ™ january 2014

This content downloaded from

202.174.120.210 on Thu, 11 Jan 2024 16:19:37 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Ball and Brown (1968): A Retrospective 13

FIGURE 2

Ball and Brown API for EPS Good/Bad News

Rescaled

before the announcement month, which can be seen clearly in Figure 1. Possible sources of

"leakage" of earnings-related information are earlier announcements of dividends, earning

interim periods, contracts won, production figures, and so forth.

More on Timeliness

The second main result addressed the timeliness of accounting earnings. We concluded

However, most of the information contained in reported income is anticipated by th

market before the annual report is released. In fact, anticipation is so accurate that t

actual income number does not appear to cause any unusual jumps ... in the

announcement month (BB68, 170).

The timeliness notion has not been appreciated as well as it might be. We now discuss it further

because it is a remarkably simple yet extraordinarily general concept, and it may yield many more

insights in the future.

Figure 2 is a rescaled version of the BB68 Figure 1. The solid line is the market-adjusted

average price movement for good news, and the dashed line is for bad. Why was bad news in the

BB68 sample on average more timely? Was there a litigation story back then? We do not imagine so.

14 In this quote, when "the annual report is released" refers to the first earnings announcement in the press.

The Accounting Review Α^ο'ύηΙΓπι

January 2014 V Associi,,i°;

This content downloaded from

202.174.120.210 on Thu, 11 Jan 2024 16:19:37 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

14 Ball and Brown

FIGURE 3

Ball and Brown versus Nichols & Wahlen, API for EPS Good News

Rescaled

1.00

0.90

0.80

0.70

0.60

• N&W Rescaled

£ 0.50

α.

<

»

• BB

BB Re-scaled

Re-scaled

0.40

0.30

0.20

0.10

0.00

-12 -11 -10 -9

-9 -8

-8 -7

-7 -6

-6 -5

-5 -4

-4 -3

-3 -2

-2 -1

Month Relative to Announcement Month

Nichols and Wahlen (2004) published a partial replication of BB68 using more up-to-da

Figure 3 compares the rescaled lines for good news in their paper (the solid line) and in B

dashed line). Do we not expect the solid line to be to the left of the dashed line? Has the

community not vastly improved its research methods since the 1950s and 60s? Have there n

more frequent and more substantive disclosures, and would we not expect price-s

information to be coming out faster? Their findings are reassuring.

Figure 4 is an intriguing graph. It is similar to Figure 2 and is based on the results of N

and Wahlen (2004). Figure 4 indicates good news is discovered by the stock market earlier t

news in the first half of the year, but later in the second half. Assuming this pattern is charac

and not just noise, then we are faced with a question, which we will leave with you. Why

lines cross around the middle of the year? Is there a litigation risk story here?

This was the first use of the research technique of measuring important properties of ac

information by benchmarking accounting income against stock returns (a proxy for econ

income). In a well-functioning capital market, changes in stock prices incorporate a wide

information, accounting income included. We were able to show that, from the shar

perspective, annual earnings announcements are not a timely source of information.

Timeliness does depend on the user's perspective, however. Many contracts with outco

that are a function of financial statement numbers are settled only annually, or perhaps qu

These include debt, compensation, supply, franchise, licensing, and royalty agreements. W

also able to show that annual earnings captures approximately one-half of the total amou

American

MfTieriCdn rj-< I . . η

Accounting

Association

1 he Accounting Review

January

This content downloaded from

202.174.120.210 on Thu, 11 Jan 2024 16:19:37 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Ball and Brown (1968): A Retrospective 15

FIGURE 4

Nichols and Wahlen (Ball and Brown Replication) API for EPS Good/Bad

Rescaled

1.00

0.90

^ ·

^ • y

*

0.80

*

0.70

0.60

»Good

Good

ξ5 0.50

<t

<

— ««Bad

«»Bad

0.40

0.30

0.20

0.10

0.00

-12 -11 -10 -9 -8 -7 -6 -5 -4 -3 -2 -1

Month Relative to Announcement Month

information available to the share market on an annual basis, an alternative benchmarking t

explain the use of financial statement numbers in those contexts.

Basu (1997) defined timeliness in annual terms in order to investigate a related proper

accounting information, asymmetric timeliness. Basu regressed annual earnings on annual r

and specified the relation as piecewise linear. This permitted a measurement of the e

conditional conservatism, which has come to be appreciated as another important propert

accounting information. Ball, Kothari, and Robin (2000) subsequently adapted the Basu me

investigate properties of accounting information in different countries, as a function of attr

their economic systems.

The general point that arises from this discussion is that timeliness—or its absence—w

central concept in BB68 and, we believe, it remains a central and perhaps under-appr

property of financial reporting today.

Challenging Received Views

One of the two central conclusions reached in the literature of the day, the conclusio

various kinds of radical change in financial reporting are required cannot be tested directly

we cannot observe the counter-factual. In that sense, all standard-setting in accounting is t

degree an act of faith, and that applies to the copious advice that the accounting literatu

giving to standard-setters at the time.

However, we did feel we could test the parallel proposition, that financial stat

information prepared under existing reporting rules is meaningless. And it failed the test.

prepared to assume that changes in share prices incorporate real changes in underlying firm

The Accounting Review Amounting

January 2014 V Assoc,a,lon

This content downloaded from

202.174.120.210 on Thu, 11 Jan 2024 16:19:37 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

16 Ball and Brown

least to some degree

maintain that acc

prevailing theories

to reject an import

At one level, the r

dire as claimed. At

could not explain,

inconsistent with—

were premised. App

many of the next

discuss further bel

Another conclusio

earnings-announcem

subsequently was r

known as "post-ear

174) was tentative

explanation fits all

literatures of "anom

V. HOW THE PAPER WAS PUBLISHED AND ULTIMATELY RECEIVED

We presented a forerunner paper to BB68 at the JAR empirical conference in M

which we investigated the relation between the earnings of the firm, its industry, and

While working on the forerunner paper we saw the potential for a second paper, and

conference. The second paper was BB68.

We presented the first version of BB68 as work-in-progress at a Chicago accountin

workshop on June 1, 1967. The title was grandiose: "A Theoretical and Empirical Eva

Accounting Income Numbers." When we fleshed out the first version, we changed the

Information Value of the Annual Earnings Report," which was more modest and mo

This version was presented at the Center for Research in Security Prices (CRSP) confe

University of Chicago in November 1967, and by then BB68 was almost complete. Be

second version is the first full draft of BB68, for historical interest we have posted i

The third and published version expanded on version two and has the title, "An

Evaluation of Accounting Income Numbers." In response to comments on earlier

re-wrote the introduction to explain BB68's place relative to the classics, and we re-

An analogy that might help explain the relation between the two propositions is given by motor in

was as if academics were saying "[W]e have not collected data on whether or how consumers us

currently are designed, but we know a priori that these cars are useless and all cars hencefor

redesigned as 16-wheel trucks." Suppose the data reveal consumers actually find cars to be useful,

are. That result does not necessarily imply social welfare would not be improved if cars w

redesigned as 16-wheelers, but it does cast some doubt on the reasoning behind the conclusion

would be improved.

The first reference to an "efficient" market for securities was three years earlier, in Fama (19

efficient market, competition among the many intelligent participants leads to a situation where, a

time, actual prices of individual securities already reflect the effects of information based both o

have already occurred and on events which, as of now, the market expects to take place in the

Fama (1965a, 90) as " a market where, given the available information, actual prices at every

represent very good estimates of intrinsic values." Ball (1978) appears to have first used the term

describe evidence that was inconsistent with market efficiency.

Ball, Ray and Brown, Philip R., The Information Value of the Annual Earnings Report (Oct

Available at SSRN: http://ssrn.com/abstract=2128616 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2128616

Ό Accounting The Accounting Review

Association

January 2014

This content downloaded from

202.174.120.210 on Thu, 11 Jan 2024 16:19:37 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Ball and Brown (1968): A Retrospective 17

conclusion. There is more discussion of econometric

and 2 were combined into a new Figure l.18 We a

forecast errors of the three models (explained above),

As now is well known, our paper, Ball and Brown

The Accounting Review (TAR). In hindsight we have

Charles H. Griffin. It must have been almost impos

would have been competent to handle the submissio

research. We have only a loose recollection of the edi

have not survived several moves by both of us, b

discussion of the extant theory literature and its shor

little to do with accounting.

Publication in Journal of Accounting Research

The Journal of Accounting Research had been e

initial assistance from the London School of Economi

accounting. In 1968, Nicholas Dopuch was appointed a

with Sidney Davidson.

When we received the rejection letter from TAR w

of age, Ray 24, we were both relatively inexperienc

apparently was not good enough for TAR. Nick Dop

after Phil (the corresponding author) had opened the

like, "Hey, what's wrong?" Phil's reply was typical of

letters. Nick, who knew the paper well and had pre

responded, "I'll publish it," and in a nutshell that's

Nick had been quick to see the paper's potential an

not for his foresight, the paper might have languish

evolved in a completely different direction.

Reaction to BB68's Publication

The immediate reaction of influential senior faculty around the world ranged from indifferen

to open hostility. In a review entitled "Stock Market Prices and Accounting Research," Chambe

(1974, 53-54) responded in his typically aggressive and fulsome fashion, including the followin

The connection between information and prices is too loose to warrant any firm inference

about the effects of one class of information.

The stock market and operations in it are extraordinarily complex. So complex in fact that

it provides opportunity alike for serious scholars to debate its processes, for intermediaries

to earn handsome incomes (and some to fail) in it, and for peddlers of tips and advice to

gather a wide following in it. Experts who have worked in it for years admit that they

understand little of what causes shifts in security prices. But it is almost beyond question,

if one is a market-watcher, that non-accounting information and judgments and events

have a more severe, a more frequent and a more readily identifiable impact on prices than

does accounting information. If anything, accounting may be regarded as the substratum,

18 Phil Brown had drawn the old Figures 1 and 2 and they were on his desk when an M.B.A. student came into his

office and somewhat pointedly asked, "What are they?" The student had worked as a professional draftsman

before enrolling in an M.B.A. and he offered to re-draw BB68, Figure 1. Had we not accepted his offer, we doubt

Figure 1 would be as recognizable as it is today.

The Accounting Review ΝΓ5 A,,,*,'c,!,

V-, Accounting

Association

January 2014

This content downloaded from

202.174.120.210 on Thu, 11 Jan 2024 16:19:37 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

18 Ball and Brown

FIGURE 5

Citation Count BB68, 1968-2012

52 II

52 ρ

50ί i'

50

48 ||l

48

46 1!

44

44-i

42

40 -

40 ·;

381

381

36 i

361

34 j

32-!

32 j

30

28

28iI

261|

261

24

24 \\\

\

22 j;Ijj

22

20

201J

IDlONNNNNNKKNNtOBffllOtOMfflfflaiBffimmOlfflOlCnOlOimOO

Ιί>ΐΛΚΓ^ΚΚΚίν.ΚΚΝ.ΓχίΟΟΟ«0«ΟίΟΰΟ(»α3ΰΐΟΟ<Τι(7ισ><ησισι(ησιί7ισΐΟΟΟΟΟΟΟΟΟΟ»Η^Η^

cn<ntno>Ao^cnAo^o^in(ncncn<no^o^(no>(Tto>(7to^(7to^(n<no>(noNo\o^oo

cntntn(i>o\^cn(n<n(n0^(ncncn(no^o^o^o>o^o^(n<n<7to^(no\o>no^<n(nooooooooooooo

MrfWHHHHHrtHHHHHHHHHHHHriHHHrtHHHHHrifMIMNMNIMNNMNNIMM

Source: Web of Science, visited Fe

overlaid by so many other fac

surface has little identifiable

itself extraordinarily uneven,

be attributed to the quality of

A rare supportive "old schoo

Queensland, who tried to recr

Western Australia) and Ray (w

Reg had some second thoughts

Between 1968 and approximate

small. Figure V depicts the 682

Reuters' Web of Science (at the

cites or citations by other schol

influence of the paper began to

19 The first, in 1968, was by Bill Be

Gene Fama in his seminal review art

Virgil. Four of the next nine citati

T| Accounting The Accounting Review

Association

January 2014

This content downloaded from

202.174.120.210 on Thu, 11 Jan 2024 16:19:37 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Ball and Brown (1968): A Retrospective 19

the paper received the American Accounting As

Contribution to the Accounting Literature, which is a

a work that has been published for at least 15 years

cited as often or has played so important a role in th

the past thirty years."

Nevertheless, the accounting area is rich in altern

can't please everyone." Richard Mattessich is a high

prolific surveyor of the accounting literature and it

the last two centuries of accounting research, the rec

an eight-line mention at the end of a subsection en

Accounting." It is included among many papers surv

subsection entitled, "Other Trends of the 1960s" (M

to either of our two basic results, or their implicatio

paper, as distinct from the reception it received, is a

our earnings surprise variable had "the status of

content" (Mattessich 2008, 203).

VI. WHAT WE SEEMED TO GET RIGHT

The success of BB68 was due in part to interest in the topic and the novel resu

but it also was due to some things we apparently got right in the research design and

of the paper, at least by the standards of the day. Specifically:

• The paper in some ways set a standard for "good" empirical research. It used

science, formulated a testable hypothesis, was careful in handling its data,

of being replicated.

• We focused on earnings, noting that "net income is a number of particu

investors" (BB68, 160). Earnings has the additional advantage of being a

variable for changes to balance sheet variables, many of which pass through

statement. In particular, earnings timeliness is correlated with timeliness in r

sheet numbers in general.

• How to specify the earnings variable was not clear. The only event study pr

Fama et al. (1969), whose event, a stock split, did not seem comparable

discretionary. The mere fact that a firm announces its earnings is not in itself

earnings reports are mandatory. We settled on measuring the "unexpected co

"forecast error" in earnings announcements (BB68, 162), using a simple rando

and a model that controlled for market effects. We also used the labels "news" and "new

information" to describe this concept. Subsequent literature and Wall Street practice uses the

term "earnings surprise."

• To measure the expected content of annual earnings, we adopted three alternative

specifications: market models for changes in Net Income and EPS, and a "naïve" random

walk expectations model for EPS. All assume that first differences provide the appropriate

specification for earnings news. We knew this was a strong assumption, which prompted

Ball and Watts (1972), in response to Phil's suggestion, to confirm that a random walk

specification was not as "naïve" as one might have expected, particularly for expectations

formed a year in advance. Subsequently, Bradshaw, Drake, J. Myers, and L. Myers (2012)

confirmed that random walk EPS forecasts are more accurate than analysts' forecasts over

longer horizons, as well as for small and young firms, and that over shorter horizons the

difference in accuracy is not economically significant.

The Accounting Review **«■»!!■«

January 2014 ν

This content downloaded from

202.174.120.210 on Thu, 11 Jan 2024 16:19:37 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

20 Ball and Brown

• In comparison w

observed returns

statistical signifi

• In part because

careful in execut

the Wall Street J

Journal; we close

number of corre

versus log return

Asset Pricing Mo

• Finally, we avoi

"a mechanism h

controversial cho

that one cannot

advocates of radi

VII. LIMITATIONS

In hindsight and by today's standards, BB68 has several notable deficiencies, some

are listed below.

• The sample size was relatively small, comprising nine annual observations for each of 261

firms, giving a total of 2,349 firm-year observations. This compares with current sample

sizes well in excess of 100,000. Large sample sizes can be a two-edged sword, however.

They can increase the distance between the data and the researcher, who risks being unaware

of important data characteristics. They also can encourage the researcher to focus on easily

attainable t-statistic cut-offs, at the expense of addressing whether the magnitudes of the

reported effects are economically substantial and whether they are consistent with both

theory and common sense.

• At the time, CRSP provided only monthly stock returns. Subsequent studies utilize

higher-frequency data. However, with the exception of testing for anomalous price

reactions, it is not obvious that higher-frequency data would have changed our

conclusions substantively.

• The test statistics were weak by today's standards. We conducted a non-parametric Chi

square test, assuming independence.20 We were more interested in magnitudes and happy

with a simple test. More complicated tests were not feasible: we had to write our own

computer programs and could not store large matrices in computer memory (The University

of Chicago's computer had 32K of addressable memory for data and software). This too was

a two-edged sword: computing turnaround was as long as 24 hours, so one thought more

about the specification in advance, and data mining was not an option.

• There was a severe sample selection bias. The initial Compustat file covered larger firms that

were in existence at the time it was constmcted. Consequently, it did not cover smaller firms

and those that were delisted due to acquisition or failure. We imposed additional selection

bias by requiring 21 years of earnings data, 100 months of price data, and earnings

announcement data, as well as a December 31 year-end.

20 The only previous event study, Fama et al. (1969), did not provide any test statistics. The enormous influence

that paper had on the literature reinforces the point about the importance of economic versus statistical

significance.

V"* American

Accounting

Association

The Accounting

T/ i . n

Review

January 20

This content downloaded from

202.174.120.210 on Thu, 11 Jan 2024 16:19:37 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Ball and Brown (1968): A Retrospective 21

Needless to say, many of these research design f

provides one measure of the extent to which researc

also goes to show that it pays to have the first word

VIII. MISUNDERSTANDINGS

As might be expected of a novel piece of research, some aspects of BB68 were misun

One misunderstanding involved confusing our two principal results, which we d

"usefulness" (on which dimension accounting income received a positive rating) and "t

(a negative rating). Smith Bamber, Christensen, and Gaver (2000) show that the

literature essentially ignored the timeliness result, and instead conveyed the erroneous

that earnings announcements release substantial new information. They attribute the

researchers over-generalizing the results from the unrepresentative sample of small firm

(1968). Ball and Shivakumar (2008) attribute it also to researchers comparing event-da

price volatility with that of an average day, thereby depicting an apparent "spike," wh

are only four such event days each year and their volume and volatility constitute a smal

volume or volatility aggregated over the whole year. We suspect that another reason fo

our negative rating on timeliness was the understandable desire of researchers to

"accounting matters." The belief that accounting income definitely matters was in fact

point, when we reasoned it must matter to have survived as an important institutional f

evidence we reported indicates the reason it matters cannot involve timeliness.

Another misunderstanding concerned the implications of our results for the extant

We note above that although our research design did not directly test any of the alternativ

schemes proposed in that literature, we were able to test the literature's proposition that th

reporting scheme produced meaningless numbers. Nevertheless, researchers of the "o

generally dismissed price-based research because it did not test the alternative reportin

ignoring our evidence that users did not act as if accounting income is totally devoid o

Thus, in his review of price-based research Chambers (1974, 50) argued:

it just does not tackle the kind of question which has concerned those whose explorat

research processes are criticized in the opening paragraphs of the paper. For that rea

offers no mode of testing the propositions of those who have concerned themselves

the betterment of accounting theory or practice.

The counter-factual in the form of any proposed alternative to the status quo is by d

unobservable, not only to us, but also to the proponents of such schemes. But that does

price-based research cannot be used to test propositions made by those proponents. We

reported evidence contradicting the proposition, asserted regularly in the literature sin

(1929), that accounting income is devoid of meaning because it is not founded on a ho

set of principles, rules, and methods. Furthermore, there were wider implications, sinc

result brought into question the whole way of thinking on which that proposition and t

alternative accounting schemes were based.

A related misconception is that there is little or no overlap between "positive"

research and "normative" a priori research. A distinction between them, which dates at

back as Hume, was introduced to the economics literature in 1891 by John Neville Keyn

of John Maynard Keynes, as follows:21

Quoting from the fourth edition, reprinted in Keynes (1999, 22).

The Accounting Review Account**

January 2014 V

This content downloaded from

202.174.120.210 on Thu, 11 Jan 2024 16:19:37 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

22 Ball and Brown

a positive scienc

is; a normative o

criteria of what

the actual, (emp

Keynes' distincti

Chicago on testin

While our resea

viewed it as havi

propositions abou

ought to be." In

"what ought to be

mode of research

theorizing, and n

A related concer

our paper was pu

norms.22 This co

overlap between

genesis of a now

including investo

compensation, sup

these uses prior

develop optimal s

standards without

In that sense, th

theorizing based

IX. SOME LITERATURE THAT ENSUED

One reason for the success of BB68 was that it opened up a variety of research poss

the relation between financial statement variables and stock prices. The following is a s

research that ensued, in approximate chronological order:

1. International replication of the results, starting (no surprise here) with Austral

1970, 1972);

2. Extending the results to quarterly earnings announcements, in Brown and

(1972);

3. Investigating the time-series behavior of accounting earnings, starting with t

Watts (1972) verification that the random walk process we assumed when c

unexpected earnings is, in fact, a reasonable characterization;

4. Extending the earnings-returns relation to higher moments by studying the r

between accounting and market measures of risk (Ball and Brown 1969; Beaver

and Scholes 1970);

5. Studying the relation between firms' changes in accounting techniques and the

prices (Ball 1972). Following the insights of Watts (1977), this work took a radi

~2 For example, see the discussion in Leisenring and Johnson (1994), Schipper (1994), and Beresford

(1995).

Applyin the automobile industry analogy above, how can cars be redesigned without any knowledge of how

23 Applying

they are driven, what they are used to transport, whether they are simply kept for show, etc?

American fi \ , · r> ·

Accounting The Accounting Review

^ Association January 20

This content downloaded from

202.174.120.210 on Thu, 11 Jan 2024 16:19:37 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Ball and Brown (1968): A Retrospective 23

toward studying firms opportunistically lobbyin

accounting techniques (Watts and Zimmerman 1

to influence debt constraints and management

of thinking then led to the modern "earnings m

6. Earnings forecasts issued by managers (Foster

7. Using daily returns (Foster 1977) and short-ev

response coefficients" (Beaver, Lambert, and

Shah 1984);

8. Information transfers between firms that are

(Firth 1976; Foster 1981);

9. The nature and determinants of post-announce

1984; Bernard and Thomas 1990);

10. The distinction between recognition and dis

1989).

11. Nonlinearities in the returns-earnings relation24 (Freeman and Tse 1992), which Hayn

(1995) attempted to explain in terms of corporate liquidation options and Basu (1997)

attributed to conditional conservatism, under which timely loss recognition generates more

large negative transitory earnings components than positive;

12. Earnings decomposition into cash flow and accruals (Dechow 1994; Sloan 1996);

13. Exploiting cross-regime effects such as international differences (Ball et al. 2000) and

differences between private and public companies (Ball and Shivakumar 2005) to better

identify the economic and political determinants of important properties of financial

reporting, such as timeliness and conservatism.

14. Aggregate earnings and returns (Kothari, Lewellen, and Warner 2006).

X. CONCLUDING COMMENTS

Overall, Ball and Brown (1968) expressed a view of information in markets that was

accounting literature, and contributed to a sea change in attitudes toward finan

disclosure, and financial reporting. Viewed more generally, the research demon

accounting is a viable area for market-based and information-economics reasoning, at

these areas were just being developed. It helped elevate the status of accounting rese

colleagues in adjacent areas and in universities generally. We are fortunate and prou

authored it.

REFERENCES

Anderson, D., and R. Leftwich. 1974. Securities and obscurities: A case for reform of the

accounts. Journal of Accounting Research 12 (2): 330-340.

Ball, R. 1972. Changes in accounting techniques and stock prices. Journal of Account

(Supplement): 1-38.

Ball, R. 1978. Anomalies in relationships between securities' yields and yield-surrog

Financial Economics 6 (2-3): 103-126.

Ball, R., and P. Brown. 1968. An empirical evaluation of accounting income numbe

Accounting Research 6 (2): 159-178.

Ball, R., and P. Brown. 1969. Portfolio theory and accounting. Journal of Accounting Resear

As we predicted in BB68, footnote 40.

The Accounting Review Ό i I Accounting

American

January 2014 ^ αμολλοπ

This content downloaded from

202.174.120.210 on Thu, 11 Jan 2024 16:19:37 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

24 Ball and Brown

Ball, R., S. P. Kothar

accounting earning

Ball, R., and L. Shiv

timeliness. Journa

Ball, R., and L. Shiva

Research 46 (5): 97

Ball, R., and R. Watt

(3): 663-681.

Barth, M. E. 2013. M

Stanford Universi

id=2235759

Basu, S. 1997. The conservatism principle and the asymmetric timeliness of earnings. Journal of

Accounting and Economics 24 (1): 3-37.

Beaver, W., P. Kettler, and M. Scholes. 1970. The association between market determined and accounting

determined risk measures. The Accounting Review 45 (4): 654—682.

Beaver, W., R. Lambert, and D. Morse. 1980. The information content of security prices. Journal

Accounting and Economics 2 (1): 3-28.

Beaver, W. H. 1968. The information content of annual earnings announcements. Journal of Accountin

Research 6 (Supplement): 67-92.

Beaver, W. H., C. Eger, S. Ryan, and M. Wolfson. 1989. Financial reporting, supplemental disclosures, an

bank share prices. Journal of Accounting Research 27 (2): 157-178.

Beresford, D. R., and L. T. Johnson. 1995. Interactions between the FASB and the academic community.

Accounting Horizons 9 (4): 108-117.

Bernard, V. L., and J. K. Thomas. 1990. Evidence that stock prices do not fully reflect the implications o

current earnings for future earnings. Journal of Accounting and Economics 13 (4): 305-340.

Bradshaw, M. T., M. S. Drake, J. Ν. Myers, and L. A. Myers. 2012. A re-examination of analysts' superiorit

over time-series forecasts of annual earnings. Review of Accounting Studies 17 (4): 944—968.

Brown, P. 1970. The impact of the annual net profit report on the stock market. The Australian Accountant

40 (July): 277-283.

Brown, P. 1972. Those half-yearly reports. In Society Bulletin. Canberra, Australia: Australian Society o

Accountants.

Brown, P. 1989. Ball and Brown [1968]. Journal of Accounting Research 27 (Supplement): 202-217.

Brown, P., and J. W. Kennelly. 1972. The informational content of quarterly earnings: An extension a

some further evidence. The Journal of Business 45 (3): 403-415.

Canning, J. B. 1929. The Economics of Accountancy. New York, NY: The Ronald Press Co.

Chambers, R. J. 1966. Accounting, Evaluation and Economic Behavior. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prent

Hall, Inc.

Chambers, R. J. 1973. Observation as a method of inquiry-—The background of securities and obscurities.

Abacus 9 (2): 156-175.

Chambers, R. J. 1974. Stock market prices and accounting research. Abacus 10 (1): 39-54.

Chambers, R. J. 1976. Fair Financial Reporting in Law and Practice. Saxe Lecture in Accounting, Baruch

College-CUNY. Available at: http://www.baruch.cuny.edu/library/alumni/online_exhibits/digital/

saxe/saxe_1976/chambers_76. htm

Davidson, S. 1966. Editor's preface. Journal of Accounting Research, Empirical Research in Accounting:

Selected Studies 1966 4 (Supplement): iii.

Dechow, P. M. 1994. Accounting earnings and cash flows as measures of firm performance: The role of

accounting accruals. Journal of Accounting and Economics 18 (1): 3—42.

Demsetz, H. 1969. Information and efficiency: Another viewpoint. Journal of Law and Economics 12 (1):

1-22.

Dyckman, T. R., and S. A. Zeff. 1984. Two decades of the Journal of Accounting Research. Journal of

Accounting Research 22 (1): 225-297.

Accounting The Accounting Review

V A"°**,,on January 2014

This content downloaded from

202.174.120.210 on Thu, 11 Jan 2024 16:19:37 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Ball and Brown (1968): A Retrospective 25

Edwards, Ε. Ο., and P. W. Bell. 1961. The Theory and

Angeles, CA: University of California Press.

Fama, E. F. 1965a. The behavior of stock-market pr

Fama, E. F. 1965b. Random walks in stock market p

Fama, E. F., L. Fisher, M. C. Jensen, and R. Roll. 1969.

International Economic Review 10 (1): 1-21.

Firth, M. 1976. The impact of earnings announcement

The Economic Journal 86 (342): 296-306.

Fisher, L., and J. H. Lorie. 1964. Rates of return on inv

of the University of Chicago 37 (1): 1—21.

Foster, G. 1973. Stock market reaction to estimates of

Accounting Research 11 (1): 25-37.

Foster, G. 1977. Quarterly accounting data: Time-se

Accounting Review 52 (1): 1-21.

Foster, G. 1981. Intra-industry information transf

Accounting and Economics 3 (3): 201-232.

Foster, G., C. Olsen, and T. Shevlin. 1984. Earnings

returns. The Accounting Review 59 (4): 574—603.

Freeman, R. N., and S. Y. Tse. 1992. A nonlinear mode

Journal of Accounting Research 30 (2): 185-209.

Friedman, M. 1953. The methodology of positive e

Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Gaffikin, M. J. R. 1988. Legacy of the golden age: Rec

Abacus 24 (1): 16-36.

Griffin, P. A. 1976. Competitive information in the sto

and analysts' forecasts. The Journal of Finance 3

Hagerman, R. L., M. E. Zmijewski, and P. Shah. 1984.

earnings forecast errors and risk-adjusted stock re

540.

Hayn, C. 1995. The information content of losses. Jo

Holthausen, R. W. 1981. Evidence on the effect o

contracts on the choice of accounting techniques: T

of Accounting and Economics 3 (1): 73-109.

Keynes, J. N. 1999. The Scope and Method of Politi

Kitchener, Canada: Batoche Books.

Kothari, S. P., J. Lewellen, and J. B. Warner. 2006.

behavioral finance. Journal of Financial Econom

Kuhn, T. S. 1969. The Structure of Scientific Revolut

Leftwich, R. 1980. Market failure fallacies and acc

Economics 2 (3): 193-211.

Leisenring, J. J., and L. T. Johnson. 1994. Accounting

Accounting Horizons 8 (4): 74-74.

Mattessich, R. 2008. Two Hundred Years of Accountin

Ideas, and Publications (From the Beginning of th

Twenty-First Century). London, U.K.: Routledge.

Nelson, C. 1973. A priori research in accounting.

Evaluation, edited by N. Dopuch, and L. Revsine, U

Research in Accounting, University of Illinois.

Nichols, D., and J. Wahlen. 2004. How do earnings nu

accounting research with updated evidence. Acco

Ogden, C. K., and I. A. Richards. 1923. The Meaning of

Thought and of the Science of Symbolism. Oxford

The Accounting Review Ό i I American

Accounting

January 2014 v A"°C'*tk>"

This content downloaded from

202.174.120.210 on Thu, 11 Jan 2024 16:19:37 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

26 Ball and Brown

Ohlson, J. A. 1991. The

Contemporary Accoun

Schipper, K. 1994. Acade

(4): 61-73.

Sloan, R. G. 1996. Do st

earnings? The Account

Smith Bamber, L., T. E.

know? A case study o

Organizations and Soci

Watts, R. L. 1977. Corp

Australian Journal of

Watts, R. L., and J. L. Z

standards. The Accoun

Wheeler, J. T. 1970. Acc

γΡΛΐ American

W ÎSSSmiS! The Accounting Review

January 2014

This content downloaded from

202.174.120.210 on Thu, 11 Jan 2024 16:19:37 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

You might also like

- A Short History of Financial Ratio AnalysisDocument12 pagesA Short History of Financial Ratio AnalysisShweta work100% (1)

- Designing Social Inquiry: Scientific Inference in Qualitative Research, New EditionFrom EverandDesigning Social Inquiry: Scientific Inference in Qualitative Research, New EditionRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (15)

- PICOT Question GRADEDDocument6 pagesPICOT Question GRADEDkeybateNo ratings yet

- Money in A Theory of Finance, Gurley PDFDocument385 pagesMoney in A Theory of Finance, Gurley PDFShrishailamalikarjun100% (1)

- Hans Gûnther - The Religious Attitudes of The Indo-EuropeansDocument106 pagesHans Gûnther - The Religious Attitudes of The Indo-EuropeansJuanito y Don Francisco100% (1)

- Tugas Pertemuan 1Document27 pagesTugas Pertemuan 1Pranidya MuhammadNo ratings yet

- Ball and Brown (1968) - A RetrospectiveDocument45 pagesBall and Brown (1968) - A RetrospectivelupavNo ratings yet

- Ball PDFDocument44 pagesBall PDFMariene Resende CunhaNo ratings yet

- Do We Really Know What We Think We KnowDocument27 pagesDo We Really Know What We Think We KnowvaniamarNo ratings yet

- Ball and BrownDocument2 pagesBall and BrownTamer Shurafa Abu AhmedNo ratings yet

- Whither Accounting Research?: Anthony G. HopwoodDocument10 pagesWhither Accounting Research?: Anthony G. HopwoodnurulNo ratings yet

- How the Financial Crisis and Great Recession Affected Higher EducationFrom EverandHow the Financial Crisis and Great Recession Affected Higher EducationNo ratings yet

- Housing and Mortgage Markets in Historical PerspectiveFrom EverandHousing and Mortgage Markets in Historical PerspectiveEugene N. WhiteNo ratings yet

- 2020-10-20 SLC MinutesDocument12 pages2020-10-20 SLC MinutestaeraNo ratings yet

- Back Matter Source: World Policy Journal, Vol. 26, No. 2 (Summer, 2009) Published By: Duke University Press Accessed: 07-02-2019 06:41 UTCDocument14 pagesBack Matter Source: World Policy Journal, Vol. 26, No. 2 (Summer, 2009) Published By: Duke University Press Accessed: 07-02-2019 06:41 UTCPen ValkyrieNo ratings yet

- Concerned Alumni Report 2023Document75 pagesConcerned Alumni Report 2023cpugh100% (1)

- Speculative Bubbles and Bitcoin Market: Empirical Investigation by GS-ADF and MS-ADF TestsDocument30 pagesSpeculative Bubbles and Bitcoin Market: Empirical Investigation by GS-ADF and MS-ADF TestsQuỳnh NguyễnNo ratings yet

- F MangDocument49 pagesF MangShahbaz ToriNo ratings yet

- Fundamentalist Xian Belief EnvironmentDocument82 pagesFundamentalist Xian Belief EnvironmentJoEllyn AndersonNo ratings yet

- Mapping The Literature On Credit Unions A Bibliometric Investigation Grounded in Scopus and Web of ScienceScientometricsDocument32 pagesMapping The Literature On Credit Unions A Bibliometric Investigation Grounded in Scopus and Web of ScienceScientometricsFauzan AdhimNo ratings yet

- Bhopal in The Federal Courts - How Indian Victims Failed To Get JuDocument45 pagesBhopal in The Federal Courts - How Indian Victims Failed To Get JuAnonymous OstrichNo ratings yet

- Philosophical Foundations of Climate Change Policy Joseph Heath All ChapterDocument67 pagesPhilosophical Foundations of Climate Change Policy Joseph Heath All Chaptermonica.murray732100% (7)

- The Proposal EconomyDocument23 pagesThe Proposal EconomyZina LaouarNo ratings yet

- A Historical Analysis of How Preach My Gospel Came To BeDocument157 pagesA Historical Analysis of How Preach My Gospel Came To BeKarissa MorrisNo ratings yet

- Schultz Elliott OBrien - 2014 - Regional Journal in Soc TAS Online First Author PDFDocument15 pagesSchultz Elliott OBrien - 2014 - Regional Journal in Soc TAS Online First Author PDFKesthara VikasaNo ratings yet

- 1997 - Buhr - Accounting, A Multiparadigmatic Science - Book ReviewDocument4 pages1997 - Buhr - Accounting, A Multiparadigmatic Science - Book ReviewDaisy KusumaningtyasNo ratings yet

- Wiley, Accounting Research Center, Booth School of Business, University of Chicago Journal of Accounting ResearchDocument4 pagesWiley, Accounting Research Center, Booth School of Business, University of Chicago Journal of Accounting ResearchAli MaksumNo ratings yet

- 09-10 AnnualReportDocument81 pages09-10 AnnualReportphilosophicusNo ratings yet

- College Choices: The Economics of Where to Go, When to Go, and How to Pay for ItFrom EverandCollege Choices: The Economics of Where to Go, When to Go, and How to Pay for ItNo ratings yet

- Topics in Empirical International Economics: A Festschrift in Honor of Robert E. LipseyFrom EverandTopics in Empirical International Economics: A Festschrift in Honor of Robert E. LipseyNo ratings yet

- An Accounting HistoriographyDocument24 pagesAn Accounting HistoriographysablcsNo ratings yet

- Rules and Restraint: Government Spending and the Design of InstitutionsFrom EverandRules and Restraint: Government Spending and the Design of InstitutionsNo ratings yet

- The Great Inflation: The Rebirth of Modern Central BankingFrom EverandThe Great Inflation: The Rebirth of Modern Central BankingNo ratings yet

- Report On Interculturality - Khlifi RattrapageDocument15 pagesReport On Interculturality - Khlifi RattrapageMohamed KhlifiNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S1045235422000661 MainDocument10 pages1 s2.0 S1045235422000661 MainMuhammad IchsanNo ratings yet

- Organizations, Civil Society, and the Roots of DevelopmentFrom EverandOrganizations, Civil Society, and the Roots of DevelopmentNo ratings yet

- The Roles of Immigrants and Foreign Students in US Science, Innovation, and EntrepreneurshipFrom EverandThe Roles of Immigrants and Foreign Students in US Science, Innovation, and EntrepreneurshipIna GanguliNo ratings yet