Professional Documents

Culture Documents

3 Valmonte V de Villa, 178 SCRA 211 1989 Privacy of Communication

Uploaded by

Rukmini Dasi Rosemary GuevaraOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

3 Valmonte V de Villa, 178 SCRA 211 1989 Privacy of Communication

Uploaded by

Rukmini Dasi Rosemary GuevaraCopyright:

Available Formats

3. Valmonte v.

De Villa, 178 SCRA 211 (1989)_ Privacy of communication and correspondence

Facts:

This case involves a petition for prohibition filed by Ricardo C. Valmonte and the Union of Lawyers and Advocates for

People's Rights (ULAP) against General Renato de Villa and the National Capital Region District Command (NCRDC). The

NCRDC had activated checkpoints in various parts of Valenzuela, Metro Manila as part of its duty to maintain peace and

order. The petitioners argue that these checkpoints violate their constitutional rights as they are subjected to regular

searches and check-ups without a search warrant or court order. They also cite an incident where a person was allegedly

shot by the military manning the checkpoint for refusing to submit to the search. The petitioners seek the declaration of

checkpoints as unconstitutional and the dismantling and banning of the same, or alternatively, the formulation of

guidelines for the implementation of checkpoints to protect the people.

Issue:

The main issue raised in this case is whether the installation of checkpoints without a search warrant or court order

violates the constitutional right against unreasonable searches and seizures.

Ruling:

The Supreme Court dismissed the petition, ruling that the checkpoints in question are not per se illegal. The Court held

that the petitioners' concern for their safety and apprehension at being harassed by the military manning the

checkpoints are not sufficient grounds to declare the checkpoints as unconstitutional. The Court emphasized that not all

searches and seizures are prohibited, and the reasonableness of a search is determined on a case-by-case basis. In this

case, the Court found that there was no proof presented to show specific violations of the petitioners' rights against

unlawful search and seizure. The Court also considered the checkpoints as a security measure to establish effective

territorial defense and maintain peace and order, especially in light of the insurgency movement in urban centers.

Ratio:

The Court's decision is based on the interpretation of the constitutional right against unreasonable searches and

seizures. The Court held that the right is personal to the aggrieved party and can only be invoked by those whose rights

have been infringed or threatened to be infringed. The Court also emphasized that the reasonableness of a search is

determined by considering the circumstances involved in each case. In this case, the Court found that the installation of

checkpoints without a search warrant or court order is not per se illegal. The Court considered the purpose of the

checkpoints, which is to establish effective territorial defense and maintain peace and order, particularly in areas with

insurgency movements. The Court also noted that the petitioners failed to provide evidence of specific violations of their

rights against unlawful search and seizure. Therefore, the Court concluded that the checkpoints in question are

reasonable and constitutional.

SARMIENTO, J., dissenting:

1. CONSTITUTIONAL LAW.; SEARCH AND SEIZURE; BURDEN OF PROVING REASONABLENESS INCUMBENT UPON THE STATE. While

the right against unreasonable searches and seizures, as my brethren advance, is a right personal to the aggrieved party, the

petitioners, precisely, have come to Court because they had been, or had felt, aggrieved. I submit that in that event, the burden is

the State's, to demonstrate the reasonableness of the search. The petitioners, Ricardo Valmonte in particular, need not, therefore,

have illustrated the "details of the incident" (Resolution, supra, 4) in all their gore and gruesomeness.

2. ID.; ID.; ABSENCE ALONE OF A SEARCH WARRANT MAKES CHECKPOINT SEARCHES UNREASONABLE. The absence alone of a

search warrant, as I have averred, makes checkpoint searches unreasonable, and by itself, subject to constitutional challenges.

(Supra.) As it is, "checkpoints", have become "search warrants" unto themselves a roving one at that.

3. ID.; ID.; CASE AT BAR NOT SIMPLY A POLICEMAN ON THE BEAT. The American cases the majority refers to involve routine

checks compelled by "probable cause". What we have here, however, is not simply a policeman on the beat but armed men, CAFGU

or Alsa Masa, who hold the power of life or death over the citizenry, who fire with no provocation and without batting an eyelash.

They likewise shoot you simply because they do not like your face.

You might also like

- An Inexplicable Deception: A State Corruption of JusticeFrom EverandAn Inexplicable Deception: A State Corruption of JusticeNo ratings yet

- Valmonte Vs de VillaDocument3 pagesValmonte Vs de VillaRean Raphaelle Gonzales100% (1)

- SEC 2, ART. III, VALMONTE vs DE VILLA 1Document3 pagesSEC 2, ART. III, VALMONTE vs DE VILLA 1Su Kings AbetoNo ratings yet

- Consti 2 Case Digests 2Document15 pagesConsti 2 Case Digests 2Cess LamsinNo ratings yet

- Valmonte v. De Villa - Military Checkpoints Do Not Violate Search and Seizure RightsDocument2 pagesValmonte v. De Villa - Military Checkpoints Do Not Violate Search and Seizure RightsMaria Cherrylen Castor Quijada100% (2)

- Valmonte Vs de Villa - CheckpointDocument4 pagesValmonte Vs de Villa - Checkpointfootsock.kierNo ratings yet

- Unreasonable Search and Seizure Cases.Document217 pagesUnreasonable Search and Seizure Cases.arsalle2014No ratings yet

- Petitioners vs. vs. Respondents Ricardo C. Valmonte: en BancDocument6 pagesPetitioners vs. vs. Respondents Ricardo C. Valmonte: en BancChristian VillarNo ratings yet

- Valmonte v. de VillaDocument2 pagesValmonte v. de VillaEunice Valeriano GuadalopeNo ratings yet

- Cases Part 1Document99 pagesCases Part 1Conrad Lark Anthony RamirezNo ratings yet

- People v. TudtudDocument34 pagesPeople v. TudtudlabellejolieNo ratings yet

- Valmonte vs. de Villa GR No. 83988Document7 pagesValmonte vs. de Villa GR No. 83988Raymond BulosNo ratings yet

- Valmonte vs. de VillaDocument7 pagesValmonte vs. de VillaFe PortabesNo ratings yet

- P4E de Villa v. Belmonte, GR 83988, 24 May 1990Document2 pagesP4E de Villa v. Belmonte, GR 83988, 24 May 1990Hanna Mari Carmela FloresNo ratings yet

- B. Digest Tapuz Vs Del RosarioDocument3 pagesB. Digest Tapuz Vs Del RosarioWhoopi Jane MagdozaNo ratings yet

- Page 9 Part 1 DigestsDocument10 pagesPage 9 Part 1 DigestsAysNo ratings yet

- Valmonte CaseDocument27 pagesValmonte Casejane_rocketsNo ratings yet

- Roan Vs GonzalesDocument4 pagesRoan Vs GonzalesMar DevelosNo ratings yet

- Tapuz V Del RosarioDocument7 pagesTapuz V Del RosarioRizza MoradaNo ratings yet

- Arts 2 10 FULL TEXTDocument585 pagesArts 2 10 FULL TEXTxxsunflowerxxNo ratings yet

- The Checkpoints Case: Valmonte v. de Villa, G.R. No. 83988 September 29, 1989 (173 SCRA 211)Document3 pagesThe Checkpoints Case: Valmonte v. de Villa, G.R. No. 83988 September 29, 1989 (173 SCRA 211)Bryan Yabo RubioNo ratings yet

- Valmonte V de VillaDocument4 pagesValmonte V de VillaChelle BelenzoNo ratings yet

- Valmonte vs. de Villa 92989Document7 pagesValmonte vs. de Villa 92989Karl Rigo AndrinoNo ratings yet

- Manalili-Dizon vs. CADocument25 pagesManalili-Dizon vs. CAArthur TalastasNo ratings yet

- Constitutional Law Ii Cases OshikoshDocument40 pagesConstitutional Law Ii Cases OshikoshFrancess Mae AlonzoNo ratings yet

- People v. TudtudDocument34 pagesPeople v. TudtudBeverly De la CruzNo ratings yet

- Stonehill v. DioknoDocument18 pagesStonehill v. DioknojrNo ratings yet

- Valmonte vs. de VillaDocument3 pagesValmonte vs. de VillaLyka Lim PascuaNo ratings yet

- Arrest, Search and SeizureDocument37 pagesArrest, Search and SeizureBer Sib JosNo ratings yet

- Valmonte V. de VillaDocument6 pagesValmonte V. de VillaLeanne NovillaNo ratings yet

- Final DigestDocument8 pagesFinal DigestMonika LangngagNo ratings yet

- Valmonte Vs Villa Case DigestDocument7 pagesValmonte Vs Villa Case DigestKristanne Louise YuNo ratings yet

- 2003-People v. TudtudDocument38 pages2003-People v. TudtudJames PabonitaNo ratings yet

- CivPro Digest 10242020Document40 pagesCivPro Digest 10242020Lorenzo CzarNo ratings yet

- Japanese Tourist Kidnapping Case Tried in Manila CourtDocument21 pagesJapanese Tourist Kidnapping Case Tried in Manila CourtShella Landayan100% (1)

- 192 Manalili v. CA - 280 SCRA 400Document20 pages192 Manalili v. CA - 280 SCRA 400Jeunice VillanuevaNo ratings yet

- LIM V. CA Case DigestDocument79 pagesLIM V. CA Case DigestWarren Codoy ApellidoNo ratings yet

- Searches and SeizuresDocument42 pagesSearches and SeizuresArnel Gaballo AwingNo ratings yet

- David Vs ArroyoDocument42 pagesDavid Vs ArroyoKarina Katerin BertesNo ratings yet

- People v. Libnao y KittenDocument10 pagesPeople v. Libnao y KittenJasmin ApostolesNo ratings yet

- Search WarrantDocument11 pagesSearch WarrantArrha De LeonNo ratings yet

- Introduction to Law Reviewer Part 2: Prospectivity, Ex Post Facto Laws, and Checkpoints CaseDocument43 pagesIntroduction to Law Reviewer Part 2: Prospectivity, Ex Post Facto Laws, and Checkpoints CaseRobert RoblesNo ratings yet

- Bill of Rights PresentationDocument42 pagesBill of Rights PresentationTreasNo ratings yet

- Due Process of Law and Equal Protection of the Laws in Philippine JurisprudenceDocument18 pagesDue Process of Law and Equal Protection of the Laws in Philippine JurisprudenceMaria Fiona Duran MerquitaNo ratings yet

- Police Fail to Uphold Rights in Custodial InterrogationsDocument27 pagesPolice Fail to Uphold Rights in Custodial InterrogationsKimberly GangoNo ratings yet

- 10 Manalili v. CADocument22 pages10 Manalili v. CAKathleen Kae EndozoNo ratings yet

- Constitutionality of Checkpoint andDocument21 pagesConstitutionality of Checkpoint andjiggerNo ratings yet

- 1 Valmonte Vs de VillaDocument8 pages1 Valmonte Vs de VillaRachel CayangaoNo ratings yet

- Stonehill v. DioknoDocument2 pagesStonehill v. DioknoAnjNo ratings yet

- Supreme Court Rules on Validity of Warrantless Arrest in Hot PursuitDocument5 pagesSupreme Court Rules on Validity of Warrantless Arrest in Hot PursuitLylo BesaresNo ratings yet

- People vs. Andre Marti (1991) case summaryDocument4 pagesPeople vs. Andre Marti (1991) case summaryAtorni JupiterNo ratings yet

- Consti Review Case DigestDocument201 pagesConsti Review Case DigestPiaRuela100% (1)

- Military Court Martial Proceedings Regarding 1989 CoupDocument4 pagesMilitary Court Martial Proceedings Regarding 1989 CoupErica NolanNo ratings yet

- Supreme Court: Valmonte v. de Villa G.R. No. 83988Document4 pagesSupreme Court: Valmonte v. de Villa G.R. No. 83988Jopan SJNo ratings yet

- Dela Cruz v. PeopleDocument58 pagesDela Cruz v. PeopleAira Marie M. AndalNo ratings yet

- 13 - Saluday V PeopleDocument29 pages13 - Saluday V PeopleMay QuilitNo ratings yet

- People'S Journal Et. Al. vs. Francis Thoenen (Freedom of Expression, Libel and National Security)Document4 pagesPeople'S Journal Et. Al. vs. Francis Thoenen (Freedom of Expression, Libel and National Security)Parity Lugangis Nga-awan IIINo ratings yet

- Searches and Seizures under the Philippine ConstitutionDocument4 pagesSearches and Seizures under the Philippine ConstitutionCamella AgatepNo ratings yet

- Bar Review Companion: Remedial Law: Anvil Law Books Series, #2From EverandBar Review Companion: Remedial Law: Anvil Law Books Series, #2Rating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (2)

- Agabon vs. NLRCDocument3 pagesAgabon vs. NLRCRukmini Dasi Rosemary GuevaraNo ratings yet

- People vs. Yambot, 343 SCRA 20, G.R. No. 120350 October 13, 2000Document3 pagesPeople vs. Yambot, 343 SCRA 20, G.R. No. 120350 October 13, 2000Rukmini Dasi Rosemary GuevaraNo ratings yet

- 199 BONBON Apo Fruits Corporation vs. Land Bank of The Philippines, 859 SCRA 620, G.R. Nos. 217985-86 March 21, 2018Document2 pages199 BONBON Apo Fruits Corporation vs. Land Bank of The Philippines, 859 SCRA 620, G.R. Nos. 217985-86 March 21, 2018Rukmini Dasi Rosemary GuevaraNo ratings yet

- Villa Ignacio v. Gutierrez GR No 93092Document2 pagesVilla Ignacio v. Gutierrez GR No 93092Rukmini Dasi Rosemary GuevaraNo ratings yet

- Mendoza v. COMELECDocument2 pagesMendoza v. COMELECRukmini Dasi Rosemary GuevaraNo ratings yet

- People v. MartiDocument2 pagesPeople v. MartiRukmini Dasi Rosemary GuevaraNo ratings yet

- Dela Cruz v. People of The PhilippinesDocument2 pagesDela Cruz v. People of The PhilippinesRukmini Dasi Rosemary GuevaraNo ratings yet

- 205 FACTOR Knecht vs. Court of AppealsDocument4 pages205 FACTOR Knecht vs. Court of AppealsRukmini Dasi Rosemary GuevaraNo ratings yet

- Yared vs. Land Bank of The Philippines, 853 SCRA 28, G.R. No. 213945 January 24, 2018Document2 pagesYared vs. Land Bank of The Philippines, 853 SCRA 28, G.R. No. 213945 January 24, 2018Rukmini Dasi Rosemary GuevaraNo ratings yet

- Angeles University Foundation vs. City of Angeles, 675 SCRA 359, G.R. No. 189999Document2 pagesAngeles University Foundation vs. City of Angeles, 675 SCRA 359, G.R. No. 189999Rukmini Dasi Rosemary GuevaraNo ratings yet

- LBP v. DalautaDocument2 pagesLBP v. DalautaRukmini Dasi Rosemary GuevaraNo ratings yet

- Evasco vs. MontanezDocument1 pageEvasco vs. MontanezRukmini Dasi Rosemary GuevaraNo ratings yet

- Yrasuegui v. Philippine AirlinesDocument2 pagesYrasuegui v. Philippine AirlinesRukmini Dasi Rosemary GuevaraNo ratings yet

- 038 JUSAY Municipality of Parañaque v. VM Realty CorporationDocument2 pages038 JUSAY Municipality of Parañaque v. VM Realty CorporationRukmini Dasi Rosemary GuevaraNo ratings yet

- 437 TAN Republic V Go Pei HungDocument2 pages437 TAN Republic V Go Pei HungRukmini Dasi Rosemary GuevaraNo ratings yet

- The Manila Banking Corporation v. BCDADocument2 pagesThe Manila Banking Corporation v. BCDARukmini Dasi Rosemary GuevaraNo ratings yet

- Manapat vs. CADocument2 pagesManapat vs. CARukmini Dasi Rosemary GuevaraNo ratings yet

- 437 TAN Republic V Go Pei HungDocument2 pages437 TAN Republic V Go Pei HungRukmini Dasi Rosemary GuevaraNo ratings yet

- Re - Application For Admission To The Philippine Bar Vicente D. ChingDocument2 pagesRe - Application For Admission To The Philippine Bar Vicente D. ChingRukmini Dasi Rosemary GuevaraNo ratings yet

- Tan v. CrisologoDocument2 pagesTan v. CrisologoRukmini Dasi Rosemary GuevaraNo ratings yet

- Tan v. CrisologoDocument2 pagesTan v. CrisologoRukmini Dasi Rosemary GuevaraNo ratings yet

- JUSAY Gaanan v. IACDocument2 pagesJUSAY Gaanan v. IACRukmini Dasi Rosemary GuevaraNo ratings yet

- Alib vs. Labayen, 360 SCRA 29, A.M. No. RTJ-00-1576 June 28, 2001Document2 pagesAlib vs. Labayen, 360 SCRA 29, A.M. No. RTJ-00-1576 June 28, 2001Rukmini Dasi Rosemary GuevaraNo ratings yet

- TRINIDAD CIR V AlgueDocument2 pagesTRINIDAD CIR V AlgueRukmini Dasi Rosemary GuevaraNo ratings yet

- Lto v. City of ButuanDocument2 pagesLto v. City of ButuanRukmini Dasi Rosemary GuevaraNo ratings yet

- Samahan NG Mga Progresibong Kabataan (SPARK) V QCDocument3 pagesSamahan NG Mga Progresibong Kabataan (SPARK) V QCRukmini Dasi Rosemary GuevaraNo ratings yet

- IDEALS vs. PowerDocument2 pagesIDEALS vs. PowerRukmini Dasi Rosemary GuevaraNo ratings yet

- COCOFED v. RepublicDocument2 pagesCOCOFED v. RepublicRukmini Dasi Rosemary GuevaraNo ratings yet

- Essential Points On Persons Criminally LiableDocument12 pagesEssential Points On Persons Criminally LiableRukmini Dasi Rosemary GuevaraNo ratings yet

- Essential Points On Stages of ExecutionDocument7 pagesEssential Points On Stages of ExecutionRukmini Dasi Rosemary GuevaraNo ratings yet

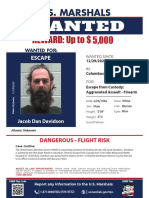

- Davidson USMS Reward PosterDocument1 pageDavidson USMS Reward PosterWSYX/WTTENo ratings yet

- Hao v. Andres: Syllabus Topic: ReplevinDocument4 pagesHao v. Andres: Syllabus Topic: ReplevinMyco Memo100% (1)

- Racine County Sheriff'S Office: Update Jail Death Ruled Accidental OverdoseDocument4 pagesRacine County Sheriff'S Office: Update Jail Death Ruled Accidental OverdoseTMJ4 NewsNo ratings yet

- DOT5 Employee ORGANIZATION CHARTDocument15 pagesDOT5 Employee ORGANIZATION CHARTAzmotulla RionNo ratings yet

- Buckeye Institute - Local Salary-EastlakeDocument5 pagesBuckeye Institute - Local Salary-EastlakelakecountyohNo ratings yet

- Crime Scence Investigation and ReconstructionDocument57 pagesCrime Scence Investigation and ReconstructionMut4nt TVNo ratings yet

- Michael Jacobs v. Eric Leon, Et Al.Document22 pagesMichael Jacobs v. Eric Leon, Et Al.Michael_Roberts2019No ratings yet

- People v. Bolasa (Digest)Document2 pagesPeople v. Bolasa (Digest)mizzelo100% (1)

- Cops Discover Shopping Cart Serial Killler's' FIFTH Victim After Missing Woman's Body Is Found in A Cart Covered With A Blanket in Washington DCDocument3 pagesCops Discover Shopping Cart Serial Killler's' FIFTH Victim After Missing Woman's Body Is Found in A Cart Covered With A Blanket in Washington DCHalimatus Sa'diyahNo ratings yet

- Fingerprinting MB WorkbookDocument4 pagesFingerprinting MB WorkbookO Choate100% (1)

- Results: The Record Is Based On A Search Using LastDocument3 pagesResults: The Record Is Based On A Search Using LastNews10NBCNo ratings yet

- Tambasen v. PeopleDocument4 pagesTambasen v. PeopleTin SagmonNo ratings yet

- Bus Services Operational ReportDocument2 pagesBus Services Operational ReportLazarus Kadett NdivayeleNo ratings yet

- Bayan v. Ermita (CPR), G.R. No. 169838, April 20, 2006Document22 pagesBayan v. Ermita (CPR), G.R. No. 169838, April 20, 2006Lourd CellNo ratings yet

- Monroe County Jail Investigation 05.13.20Document2 pagesMonroe County Jail Investigation 05.13.20Exsar MisaelNo ratings yet

- Search Warrant OperationDocument56 pagesSearch Warrant OperationKakal D'GreatNo ratings yet

- Kuhlmann Weingart COPA FindingsDocument29 pagesKuhlmann Weingart COPA FindingsTodd FeurerNo ratings yet

- The Rich Get Richer and The Poor Get PrisonDocument2 pagesThe Rich Get Richer and The Poor Get PrisondennokimNo ratings yet

- Forensic 2-PERSONAL-IDENTIFICATION-BY-CLBNDocument15 pagesForensic 2-PERSONAL-IDENTIFICATION-BY-CLBNLombroso's followerNo ratings yet

- News Articles 30Document19 pagesNews Articles 30alan_mockNo ratings yet

- Ivonne Roman ResumeDocument5 pagesIvonne Roman ResumeWSYX/WTTENo ratings yet

- Midterm Module No. 1: SEPTEMBER 28, 2021Document11 pagesMidterm Module No. 1: SEPTEMBER 28, 2021Jan RendorNo ratings yet

- Below Is A Sample Format of A Police Blotter Page: Entry No. Date Time Events/Incidents DispositionDocument6 pagesBelow Is A Sample Format of A Police Blotter Page: Entry No. Date Time Events/Incidents Disposition3ARendal, JTNo ratings yet

- (Applicable To LD) : Narrator Scene 1Document3 pages(Applicable To LD) : Narrator Scene 1netbuddy100% (1)

- Contact No. of Asansol-Durgapur Police CommissionerateDocument5 pagesContact No. of Asansol-Durgapur Police CommissionerateSudeshna PandeNo ratings yet

- Classification of PenaltiesDocument3 pagesClassification of PenaltiesMitch Rapp0% (3)

- Pad101 Group AssignmentDocument15 pagesPad101 Group Assignmentyasinhafiz1220No ratings yet

- NYPD Lieutenant Acquitted of Beating Girlfriend After OrgyDocument1 pageNYPD Lieutenant Acquitted of Beating Girlfriend After Orgyedwinbramosmac.comNo ratings yet

- Yuri Bezmenov: The Life and Legacy of the Influential KGB InformantDocument74 pagesYuri Bezmenov: The Life and Legacy of the Influential KGB InformantRajshreyash AdhavNo ratings yet

- The DEA's Powerful Presence and Sovereignty Challenges in MexicoDocument18 pagesThe DEA's Powerful Presence and Sovereignty Challenges in MexicoEsteban Lucio RuizNo ratings yet