Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Indian School Provided by Sir Akhyar Ahmad

Uploaded by

Kamran AbdullahCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Indian School Provided by Sir Akhyar Ahmad

Uploaded by

Kamran AbdullahCopyright:

Available Formats

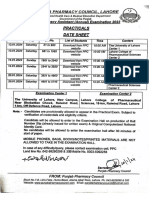

Research Paper

An Ethnographic Contemporary Education Dialogue

10(2) 163–195

Study of Disciplinary © 2013 Education Dialogue Trust

SAGE Publications

and Pedagogic Los Angeles, London,

New Delhi, Singapore,

Practices in a Washington DC

DOI: 10.1177/0973184913484996

Primary Class http://ced.sagepub.com

Suvasini Iyer

Abstract

The article presents an ethnographic study conducted in a class in a

government-run primary school in Delhi.

It was found that a chief concern in the school was that of disciplin-

ing children. In the observed class, this took the shape of controlling

children’s bodies and motor movements. It is argued that through disci-

plining, teachers were striving to create docile and obedient bodies. In

addition, disciplining was also aimed at reforming children.

The pedagogic practices were also observed to further the agenda of

reforming children. Learning was construed as no more than a set of

motor skills. Learning was seen as a passive, silent and individual activ-

ity. It is argued that the pedagogic practices employed by the teachers

served to cast a normalising gaze on the children, and to differentiate

between them along a moral–scholastic dimension. When seen through

a Foucauldian lens, it appeared that the purpose of pedagogic activity in

the observed class was to maintain surveillance.

It was found that while children actively negotiated with the prevailing

culture, they nevertheless remained bound by the dominant norms.

Keywords

Discipline, Foucault, pedagogy, classroom ethnography, reform, Krishna

Kumar, order, primary class, symbolic Interactionism, surveillance

Suvasini Iyer is Faculty at the Department of Elementary Education, Miranda

House, University of Delhi, Delhi, India. Her research interests include

studying classroom processes, children’s play and history of school education.

E-mail: c.suvasini@gmail.com

164 Suvasini Iyer

Introduction

The study presented here was conducted in 1999–2001 as part of the

author’s M.Phil. studies in Delhi University.1 It is an ethnographic study

of Class 3 in a government-run school in Delhi. The school selected for

the study was chosen because of the prior knowledge that regular teach-

ing took place in the school. Within the hierarchy of government-run

schools in Delhi, this school can be placed in the higher tiers of the sys-

tem. It operated from a two-storied building, with primary classes being

held on the ground floor. There were separate rooms for each class, in

addition to a separate principal’s room and a room for conducting admin-

istrative work. A large playground, lined with tall trees, surrounded the

school building. Morning assembly and school functions were held here.

The classrooms were well furnished, with adequate blackboards, desks,

chairs and cupboards. The school had a library as well as a computer

room.

There were a total of 800 children enrolled in the school, of which

around 75 per cent were children of government employees. Many chil-

dren were from families with an annual income of less than `50,000. The

school charged no tuition fees; additional support in terms of free uni-

forms and books was provided for children from groups with lower

socio-economic status. Children were given refreshments every day,

either biscuits or fruits.2

The Class 3 in which fieldwork was conducted had a total of 43 chil-

dren, of which 14 were girls. They were in the age group of 8–9 years.

Around half of them were getting aid from the school in terms of free-

ships. The children were largely from families from the Hindi-speaking

belt of north India.

The two teachers who were primarily responsible for the class were

from a higher socio-economic background as compared to their students.

Their own children studied in private schools.

Five subjects were taught in the class—English, Hindi, Mathematics,

Science and Social Studies. Music and Physical Training were also part

of the curriculum, but had a peripheral status.3

The daily routine in the school began at 8:45 AM with morning assem-

bly for which the children gathered in the playground. After this, the

children returned to their classroom and the teacher took the attendance

roll call. There were seven periods in a day, of 35 minutes each. The

Contemporary Education Dialogue, 10, 2 (2013): 163–195

Disciplinary and Pedagogic Practices in a Primary Class 165

lunch break was for 25 minutes. During recess, children would spend

time playing in and strolling around the playground. At 1:45 PM, children

would disperse for the day.

Theoretical Background

The primary objective of the study was to produce an internally consistent

narrative that would retain the complexity of the data. Simultaneously, an

attempt was made to ‘make sense’ of the participants’ actions by locating

the data within larger societal contexts, and by relating these data to exist-

ing theoretical literature. Some of the theoretical perspectives that were

employed for the analyses are discussed next. It must be pointed out here

that the purpose of analysis was not to ascertain the validity of a particular

theory or to test it out in the field. Theories were employed to create a nar-

rative that would be more than merely a descriptive account of the field.

The research was oriented along the methodological–theoretical per-

spective of Symbolic Interactionism (Berger and Luckmann, 1967;

Blackledge and Hunt, 1985, pp. 233–248). Within the Symbolic

Interactionist perspective, the classroom is construed to be a social space

in which ‘shared definitions of situations’ are evolved through negotia-

tions. Unequal power relations have a bearing on the negotiations, and

the more powerful actors may impose their perspectives (and the less

powerful may resist). In classroom situations, it is likely that the teacher

is more powerful than the students, and among the students, power may

be unequal and may be continually contested. Symbolic Interactionist

theory considers the negotiations between actors to be ongoing and

dynamic, and never permanently settled.

The present study drew upon the tenets of Symbolic Interactionism in

specific ways. First, it did not make any a priori assumption regarding

class differences at work, or regarding structural determinants. The start-

ing point for the analysis was the observational data. Second, the analy-

sis attempted to uncover ‘the meaning of the situation’, in this case, the

ongoing classroom interactions.

It is pertinent to note at this point an important aspect of the interac-

tions in the classroom. The teacher–student interactions appeared to the

researcher to be fragmented, discontinuous and highly ritualised.4 Often it

appeared that ‘meaning’ was a missing element in the conversations. Such

Contemporary Education Dialogue, 10, 2 (2013): 163–195

166 Suvasini Iyer

interactions posed a problem in analysis. Teachers, therefore, have been

‘explained’ to be tacitly executing pedagogies. In (the researcher) taking

such a stance, the teachers have been presented as if lacking in agency.

Therefore, while the analysis was guided by the perspective of

Symbolic Interactionism, its limitations in terms of not adequately con-

sidering the participants’ perspectives remain. It is with such caveats that

the analytic narrative must be read. The narrative presented next must

therefore be seen as a partial, not a complete or an exhaustive account of

classroom processes. The analysis gives primacy to the dominant activi-

ties in the classroom, which were invariably initiated and controlled by

the teacher. Further, it presents the teachers as if they constituted a singu-

lar entity, and differences between children are also not brought out. In

considering only the classroom interactive space, the individual teach-

ers’ voices, to an extent, have also been omitted.

The second chief strand of analysis draws upon the work of Michael

Foucault, primarily his book, Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the

Prison. According to Foucault, there emerged in the early periods of

European modernity, new forms of exercise of power and subjugation of

the masses. By their very nature, these forms of control were built into

the institutions that emerged in this period—the prison, the hospital and

modern mass schooling systems.5 All these institutions, according to

Foucault, had one thing in common: they sought to control the multi-

tudes. This new form of control directly targeted the body of the indi-

vidual. Parallel to the development of these institutions, there also

emerged new scientific ways of understanding the body that made it pos-

sible to control and regulate the body like never before. The purpose of

such control was twofold—to increase the economic utility of the body

and to make it obedient and docile. In this modern form of power, an

infinitesimal control came to be exercised over the active body—on its

movements, gestures, attitudes and its rapidity (speed). There is an ‘unin-

terrupted, constant coercion ... and is exercised according to a codifica-

tion that partitions as closely as possible time, space, movement’

(Foucault, 1977, p. 137). Interestingly, the methods through which such

ubiquitous control was achieved were called ‘disciplines’.

Within the machinery of the emerging school system, discipline

attempted to create ‘docile bodies’. In the course of time, disciplinary

control gained rapid currency and came to dominate the schooling

system. Surveillance, the key to the exercise of disciplinary power, was

Contemporary Education Dialogue, 10, 2 (2013): 163–195

Disciplinary and Pedagogic Practices in a Primary Class 167

integrated into the architecture as well as the pedagogic practices of these

early modern European schools. Schools were constructed as enclosed

spaces. The detailed and specific spatial organisation of the school was

aimed at locating individuals, and at establishing individual presences

and absences. Efficient supervision of the conduct of each individual

was a primary objective.

Integrated into the teaching and learning relationship was a supervi-

sory system; disciplining was woven into the pedagogic act. ‘Officers’

were appointed from amongst the pupils who were assigned teaching

tasks and also had to keep an eye on other children, and make note of

their errant behaviour. Therefore, ‘... a relation of surveillance, defined

and regulated (was) inscribed at the heart of the teaching practice, not as

an additional or adjacent part, but as a mechanism that is inherent to it

and which increases its efficiency’ (Foucault, 1977, p. 176).

In the present study, Foucault’s observations about disciplining and

surveillance in the schooling system are used to explain the observed

classroom interactions.

Finally, the analysis has also drawn upon the various writings of

Kumar (1992) on pedagogic practices in the Indian classroom. This has

helped make sense of the ethnographic data by linking them up to the

wider Indian social and historical context.

The research was done within the broad paradigm of the interpretive

framework (Blackledge and Hunt, 1985, pp. 233–248; Geertz, 1973). Data

collection consisted of unstructured observations in the classroom and in

the playground, during subject-teaching classes, free periods, lunch breaks

and school assemblies. The researcher also engaged in informal conversa-

tions with the participants, and conducted semi-structured interviews. The

fieldwork, which was spread over six months, consisted of over 36 hours

of observations.

Data analysis was guided by the techniques of Grounded Theory

(Strauss, 1987). To begin with, some portions of the field notes were

analysed in detail (line-by-line coding). Codes were defined and the

more abstract categories were evolved from the data. After the initial

establishment of codes, large chunks of data were placed along these

codes. Thereafter, linkages were drawn between various categories. For

example, one category ‘Child asks query’ was related to the category

‘Teacher maintains order in the classroom’. Making strong linkages

between categories helped create a conceptually dense analysis. Extensive

Contemporary Education Dialogue, 10, 2 (2013): 163–195

168 Suvasini Iyer

memos were written for each category. Through this, an attempt was

made to theorise about the data. The aim was to generate an internally

consistent narrative that would retain the complexity of the field situa-

tion, and also simultaneously engage with the disciplinary knowledge in

the social sciences and in education.

The analysis begins by unveiling the culture of discipline that was at

the core of life in the classroom.

The Culture of Discipline

Discipline as Maintaining Order

In the observed school, it appeared that maintaining discipline was val-

ued as an end in itself. Further, disciplining was understood as children

maintaining ‘physical order’. One of the practices followed in the school

was of marking classes for their orderliness. On one occasion, when the

children of the class under study stormed out of the room on hearing the

bell for the physical training (P.T.) period, their teacher reproached them.

She said, ‘Children of 4th and 5th classes maintain proper discipline.6 They

walk out of the class and walk back in [in single] lines. No one comes to

know that children are moving about’. She instructed them to do the

same, and cautioned that she would keep a check on them through the

day. The P.T. teacher, who also conducted regular drills in the morning

assembly, was an articulate spokeswoman of the disciplinary ethos of the

school. She was of the extreme opinion that ‘If teachers can’t control,

how will they teach children?’ Other teachers also agreed that control-

ling children was central to the task of teaching. These findings find

resonance in Kumar’s observations that Indian teachers show an unusual

and exaggerated concern for maintaining order amongst their students.

He further notes that Indian teachers perceive this order in a rather nar-

row and confined sense (Kumar, 1991, pp. 11–19).

Discipline as a Response to Class Size

It may be argued that excessive concern with maintaining physical order

was a managerial response to a large class of over 40 children. The

Contemporary Education Dialogue, 10, 2 (2013): 163–195

Disciplinary and Pedagogic Practices in a Primary Class 169

simultaneous presence of a large number of young children can make

unique demands on the teacher. At the very least, a teacher would have

to ensure that conditions are conducive for learning for each student. For

example, during a test, Ms Sudha7 had to ensure that the blackboard was

visible to all children (since the questions were written on the board).

She could not allow children to stand or sit as they pleased. In a social

studies class, Varun sought the teacher’s permission to stand and write

with the copy8 on his desk. Ms Das refused, as this would block the other

children’s view of the board.

The pressure to maintain order became particularly acute when class-

room activity consisted of individual work. Children worked at different

paces, and could become restless when their assigned work was finished.

When some children completed their tests before others, teachers urged

them to check their papers or revise for the next test, lest they break

loose. Such classes could be very trying for the teacher. In one such

class, where the children were copying down answers from the board,

Ms Dutt said resignedly, ‘Those who have not finished will not come to

me. Those who have finished will also not come to me’ (for checking the

copies).

The argument discussed above is in line with the observations of a

study in the U.K. by Galton et al. (1980) in which they found that in

classrooms of more than 30 children, teachers often took up managerial

roles when children were engaged in individualised tasks. During these

phases, their urgent and immediate aim was to keep the class busy. Goals

of progressive education—allowing the child to discover things for her-

self and stimulating this activity by probing and questioning the child—

took a backseat.

Therefore, it may be stated that the pursuit of ‘physical order’ was in

part the result of the large size of the class with which teachers had to

work.

Discipline as a Consequence of Disengagement

Teachers were seemingly disengaged from their work. They were found

to be divorced from, and disinterested in, their work. They seldom pos-

sessed copies of textbooks, despite their having to transact the text

through the year. The common practice was to ask children to lend a

Contemporary Education Dialogue, 10, 2 (2013): 163–195

170 Suvasini Iyer

textbook for the immediate period. When, in January 2000, the researcher

asked Ms Sudha for the half-yearly answer sheets (the examination was

held in December 1999), she replied nonchalantly, ‘I have thrown them

away for raddi’ (disposed them of as rubbish).

The above-mentioned observations may be better understood by

examining the historical development of the (school) teaching profes-

sion in our country. According to Kumar (1991, pp. 47–93), colonial rule

led to a systematic erosion of the school teacher’s professional and social

status and epistemic autonomy, all of which were enjoyed by the teacher

in the pre-colonial indigenous school. The British introduced a central-

ised and bureaucratically controlled system of education, where the

teacher became no more than a salaried employee of the state, and, fur-

ther was placed at the lowest rung of the bureaucratic ladder. Introduction

of an alien curriculum, a foreign language (English) as a medium of

instruction, and bureaucratised, impersonal examinations further eroded

the teacher’s epistemic autonomy. In this scenario, which constituted a

marked break from earlier traditions of school education, the teacher’s

role was reduced to the execution of pre-formulated syllabi using

textbooks.

According to Kumar, this led to the teacher defining her task as pri-

marily one of ‘maintaining order in [the] classroom to facilitate safe and

speedy delivery of the prescribed content’ (Kumar, 1991, p. 85).

Such a perspective helps explain the teachers’ disengagement from

the epistemic component of their work, and their parallel preoccupation

with disciplining, both observed in the study. The teachers’ definition of

their task as one of disciplining children and maintaining order in the

classroom may, therefore, be a ‘norm’ in our country, with its origins in

specific historical events. Deprived of an opportunity to imbue with per-

sonal meaning what they taught, and how they went about it, they were

compelled to define their task as that of maintaining order and gaining

control.

However, the factors discussed earlier do not explain why the mean-

ing of discipline assumed a narrow definition such as ‘regulating chil-

dren’s bodies’. It is argued in the next section that such a definition of

discipline partly resulted from the age-related characteristics of the chil-

dren, which were interpreted by the teachers as requiring ‘bodily

regulation’.

Contemporary Education Dialogue, 10, 2 (2013): 163–195

Disciplinary and Pedagogic Practices in a Primary Class 171

Creating Docile and Obedient Bodies

Children were Physically Restless/Their Symbolic Activities were ‘immature’

The children observed had a conspicuous ‘physical presence’. They had

abundant physical energy and showed quick changes in their attention

and behaviour. Their spontaneous activities were predominantly physi-

cal, such as hurling pencils with rubber-band slings and bursting paper

‘patakas’ to produce a loud noise (blowing paper bags), and revealed an

immersion in the present moment. A rat crossing the playground (the

playground could be seen from the windows) or a rain worm crawling

across the floor could throw the class into disarray. Even their play

tended to be physical, and of short duration, as is evident in the following

example.

During the lunch break, at 11:35 AM, Jyoti, Prerana, Parul, Preranarani

and Poonam were seen playing on a mound of sand, running up and

down. Soon they changed to khikli, a game in which two girls hold hands

and spin around speedily; the movement is physically exhilarating. After

this, they shifted to rotating individually, with their arms spread out hori-

zontally. They then changed the game to ‘cat and mouse’ where one girl

became the ‘pivot’ and two girls, holding the hands of the first girl,

swung about, with the ‘cat’ chasing the ‘mouse’.9 All this transpired

between 11:35 AM and 11:45 AM.

The children were characterised by physical vitality and restlessness.

Also, these children did not demonstrate any adult-like symbolic activi-

ties. This was evident in their language usages and brief exchanges. Their

conversations stemmed from the present and were at times aimed at

directing their own activities. Their voyages into any symbolic realm

were observed to be short-lived.

The conversations that the children had were rarely long-winded dis-

cussions. They stemmed from the present and tended to be of rather short

duration. In one event, Reema and some boys were engrossed in observ-

ing an insect, which had made a groove on the classroom wall, which it

had made into its home, and where it had laid its eggs.

Pranav: ‘Ma’am, she has her own children!’

‘What is it?’

‘Bee.’

Contemporary Education Dialogue, 10, 2 (2013): 163–195

172 Suvasini Iyer

Reema came closer to inspect the eggs, plucked out some eggs, threw

them to the floor, and mercilessly crushed them underfoot.

Reema, tum par paap chad jayega (Reema, ill fate will befall you [because

you have committed a sin]).

Pranav: ‘Ma’am, butterfly’s child—Reema has . . .’

Reema then asked Alok: ‘Do you know how the egg was?’

Atul was infected by the enthusiasm of the other children: ‘Egg, egg’, he

repeated.

Reema: ‘It was her child. It was small. Here, push it’. She ruthlessly shoved

paper into the groove, stuffing it completely.

Teachers’ Constructions of Children’s Characteristics

The teachers, too, referred to these characteristics—physical restlessness

and lack of mental perseverance—in their construction of their students’

characteristics and abilities. The implicit ‘theories’ employed by these

teachers may be placed in perspective by referring to Olson and Bruner’s

ideas of folk psychology and folk pedagogy (Olson and Bruner, 1996).

They argue that teachers’ pedagogies are derived not from formal theo-

retical knowledge but instead stem from cultural constructions of the

child.

In the observed milieu, teachers’ constructions revealed that they dif-

ferentiated between younger and older children. They perceived (although

not in the refined vocabulary of formal disciplinary knowledge) that

younger children are more physically present and less mature mentally,

as compared to older children. This was implicit in Ms Sudha’s remark

that ‘Older children are able to understand’. A differentiation between

younger and older children was also implicit in her remark that there are

different kinds of disciplinary problems with older children—telling lies,

not doing their homework and not informing parents. Other teachers also

lamented that younger children (when compared to older children) are

difficult to control.

Young children were seen as ‘difficult to control’ and as ‘unable to

understand’. Their physical vitality and short attention spans were inter-

preted as problems that required the regulation of their bodies. The Indian

teachers’ concern with maintaining order (Kumar, 1991) took on a rather

limited meaning in the classroom setting—demanding that children main-

tain normative body postures and behaviour. The fixation on ensuring and

Contemporary Education Dialogue, 10, 2 (2013): 163–195

Disciplinary and Pedagogic Practices in a Primary Class 173

exercising physical control was manifested in the following ritualistic

interaction between teacher and children:

Ms Dutt, the Hindi teacher, asked the students of 3rd B,10 ‘Good chil-

dren how?’

The students immediately responded, ‘Like this’. They promptly

assumed attentive postures, with folded arms and straight backs, and

faced the teacher with a watchful guard.

Ms Sudha entered 3rd B and conducted the following exercise:

‘Raise hands’.

The children raised their hands.

‘Clapping’.

The children clapped together.

‘Up down, up down’.

The children swing their arms up and down.

‘Sit down’.

The children sat.

Bernstein (1982) argued that rituals in school embody and transmit

the value system of the school. The above-mentioned rituals reveal that

the value system of the school was one of maintaining ‘physical order’.

It must be noted that the rituals were physical exercises directly focusing

on the ‘physical body’. They were blunt in asking children to rehearse

physical and motoric ‘propriety’.

These rituals also served a consensual function. In enacting such ritu-

als, individual students were likely to experience a sense of belonging to

the group. They served an important socialising function in that acting

out such rituals socialised the children into the ethos of the school.

Bernstein (1982) argued that socialisation through rituals is deep, because

it operates at a tacit, primeval level. That the children had come to share

the teachers’ definition of discipline was revealed when the teachers pro-

nounced ‘3rd B’ in a sufficiently menacing tone. The children would

assume the required postures, and order would be restored in the class-

room, at least for a while.

Central to the teachers’ constructions of children was the idea of the

‘child as a physical being’. These constructions were revealed in the

above-mentioned rituals, which served to regulate children’s bodies. In

the teachers’ construal, the child’s mental existence was largely absent

or was reduced to insignificance. It was observed that disciplinary

Contemporary Education Dialogue, 10, 2 (2013): 163–195

174 Suvasini Iyer

transgressions were also treated by resorting to physical punishment.

When Ms Sudha found Lokesh, Alok and Rahul talking, she became

furious and pulled Lokesh’s ear and slapped him. She ordered him to

assume the pose of a murga (the individual assumes a squatting position

while simultaneously holding both ears; the position imposes consider-

able strain on the body; the word murga means cock in Hindi; it is used

here in a derogatory sense) outside the class. In urging children to con-

duct themselves properly, never, not even once during the course of the

study, were teachers seen asking the children to contemplate the matter

of why they were being asked to conform to certain expectations or why

they were being punished. This strengthens the argument that for the

teachers, the children were more physical beings than thinking beings.

Through the incipient legitimisation inherent in such mutual interac-

tions, the children were socialised into the ‘teachers’ definitions of order’

(Berger and Luckmann, 1967, p. 112).

When seen from a Foucauldian perspective, one may conclude that

the teachers’ efforts were indeed aimed at controlling children’s bodies

and behaviour. Disciplining sought to create docile and obedient bodies.

Teachers construed children and children’s behaviour solely through

such a disciplinary lens. Foucault wrote that disciplinary control seeks

blind obedience; no rationale is provided for why a specific, artificial

behaviour is demanded, instilled or imposed. That the teachers observed

in the study never sought to provide any explanation, never sought to

bring into the sphere of ‘rational discussion’ the reasons for their demands

for discipline, makes sense when interpreted in this light. The ritual of

‘achhe bachhe kaise’ is also indicative that blind obedience was sought

from children.

The following section further elaborates the teachers’ constructions of

children. It is argued that the ‘hidden agenda’ behind the need to discipline

children was to reform them. Such an argument explains why teachers

used the phrase ‘good children’ in enacting the above-mentioned rituals.11

Disciplining to Reform

In this section, it is argued that central to the practice of disciplining

children was an attempt to reform children. According to Kumar, moral

upliftment was one of the concerns of the British when they established

Contemporary Education Dialogue, 10, 2 (2013): 163–195

Disciplinary and Pedagogic Practices in a Primary Class 175

schools in India (Kumar, 1991, pp. 26–43).12 The discourse of moral

upliftment also contained latent evangelical intentions; moral influence

through English education ‘was a euphemism for Christian ethics’

(Kumar, 1991, p. 33). Further, Kumar argues that Indian intellectuals and

social reformers also began to perceive the uneducated masses in the

same light as the colonisers. This was in no small measure also due to the

fact that the educated elite also came from the upper castes and/or upper

classes. Such a historical perspective helps in understanding the teach-

ers’ agenda of reforming the children.

The children in the class often did odd jobs for the teacher and for the

class. Ms Sudha would ask the children to fill up her water bottle, to keep

her lunch box in the staffroom, and to rearrange the chairs so that the

researcher could sit. It was clear that this was the accepted norm in the

class. On 16 September 1999, the few children who had come to school

(the term examinations had ended just the day before) spent a consider-

able amount of time cleaning the room with brooms and dusters. Rahul

even wiped Ms Sudha’s bag with a wet duster. The children also distrib-

uted the mid-day snack, carried notebooks for the teacher and brought

chalk boxes from the staffroom.

The researcher never saw any child protest. On the contrary, the chil-

dren appeared eager to engage in such work. Such a response on the part

of the children may be because, in general, the teacher–child relationship

lacked intimacy, and classroom life rendered the child anonymous.

Teachers threw copies at children after correction, did not know their

names, and mistook one child for another. The large class size and the

presence of many subject teachers (as opposed to one teacher teaching

all the subjects) exacerbated this sense of anonymity. It is argued that the

children did such jobs for the teachers as it offered them temporary relief

from anonymity, and bestowed on a child a monitor-like status for a short

while.13

The relative class difference between the teachers and the students

perhaps contributed to the creation and maintenance of such a culture.14

Whatever may be the reason, the consequences were clear—doing phys-

ical work was in line with, and further strengthened, the teachers’ notion

of children as do-ers.

Another dimension in the teachers’ construction was that of ganda–

acchcha, which in Hindi connoted the binary of bad–dirty–disgusting—

good. Teachers used derogatory terms for children, often labelling

Contemporary Education Dialogue, 10, 2 (2013): 163–195

176 Suvasini Iyer

children as gande. Teachers often announced in class that the children

were en masse gande. Ms Sudha, while taking an English test, pro-

nounced for no apparent reason, ‘How gande these children are, no?’

Individual children were also thus spotted. One teacher hit Reema on the

head with a book and said, ‘Complete idiot’. When Sriram hesitated in

reading, Ms Sudha scorned him: ‘Where do such namuneys come from?’

Teachers also openly expressed disgust, sarcasm, scorn and other nega-

tive feelings towards children. When Rahul got up to offer his seat to me,

Ms Sudha jeered at him: ‘Rahul . . . he also . . . is trying to become a

hero’. Once Ms Sudha remarked, ‘This Rahul, Sumit, Manoj, they are

nalayak [completely worthless, no good]’.

Implicit in such labelling of children was the understanding that the

teachers’ own pedagogy would reform the children. Disciplining chil-

dren was necessary to cleanse them of their ‘ganda-ness’. Giving marks

for orderliness thus made sense, as children had indeed earned them, by

showcasing their ‘goodness’. Such an argument is supported by the fol-

lowing example, where a teacher explicitly explained how good children

behaved: ‘Class 4th is very quiet. Children there are very good. Good

children do work and sit quietly’. Good children were disciplined. This

also explains the use of the phrase achche bachche (good children) in the

rituals conducted by the teachers.15

A Foucauldian line of analysis can expediently explain the teachers’

efforts at reforming children. According to Foucault, reform was at the

core of disciplining activity in early modern schools in Europe.

Foucault argues that at the heart of the disciplinary power exercised in

early modern schools was a judicial-penal system, wherein judgments

were passed on lapses such as (a) misuse of time/idleness; (b) failure to

perform an activity due to inattention, negligence or lack of zeal; (c)

improper behaviour such as disobedience; (d) inappropriate usage of

speech such as idle talk and (e) non-maintenance of the body such as

lack of cleanliness (Foucault, 1977, p. 178). Within this juridical system,

anything that was non-conforming became punishable. Offences included

not only behavioural infractions but also the inability to carry out

assigned tasks. The nature of punishment within this system was a form

of corrective training; the punishment purported to rectify the defects for

which the punishment was administered in the first place. For example,

a child who had not produced written work would be punished by being

ordered to do the written work many more times.

Contemporary Education Dialogue, 10, 2 (2013): 163–195

Disciplinary and Pedagogic Practices in a Primary Class 177

Within this penal system, all of a pupil’s behaviour was placed

between the two poles of good and evil. The purview of the system was

totalistic. Such a system differentiated not only the behaviour along the

good–bad/evil axis, but pupils themselves were also differentiated along

the good–bad/evil axis. Further, as noted by Ariès (1962, pp. 241–268),

in early modern Europe, childhood was construed as a stage of weak-

ness, and the practice of humiliating children was widespread. This was

institutionalised in schools. Corporal punishment became common.

Constructing the Meaning of Teaching–Learning

Classroom culture plays an important role in giving shape to the mean-

ing of subject-knowledge as received by children (Kumar, 1991, pp.

21–22, 117–130; Kumar, 1992, pp. 23–43). This is because for a child it

is through the regular and daily participation in activities involved in

learning a subject that the ‘structure of the discipline’ of that subject is

internally constructed (Schubauer-Leoni et al., 1989). The classroom

culture and the specific pedagogic practices that are followed are central

to this process of defining the meaning of a subject for the student.

In the observed class, the ‘hidden’ objective of teaching was found to

be that of reforming the children.

Teaching as Reform

In the observed class, it was not possible to distinguish between episodes

of teaching and episodes of disciplining. The processes of disciplining

and syllabus transaction were neither temporally separable (occurring

during different time periods) nor spatially separable (occurring at dif-

ferent sites). In the daily flow of classroom life, teachers would smoothly

shift from one to the other. Subject teaching was generously sprinkled

with disciplinary injunctions. Ms Dutt paused her music lesson to ‘teach’

children discipline. ‘Today, I will teach you to sit quietly. Fold your arms,

fold your hands’. Disciplining children and transacting syllabi work

were so fused together in teacher–student interactions that they seemed

to be part of the same semantic category. For example, quarrels amongst

children were addressed by alluding to work, rather than addressing the

Contemporary Education Dialogue, 10, 2 (2013): 163–195

178 Suvasini Iyer

actual issue that had led to the quarrel. When a boy beat up another boy,

the teacher demanded of the offender, ‘Why did you beat him? Do you

come to school to fight? Why isn’t your work over?’ She slapped him

and said, ‘Say sorry’. The focus was on work; the actual issue of the

conflict was not taken up. When children violated disciplinary codes, it

was by referring to work (questioning the children’s motives for coming

to school) that teachers often addressed the issue. When a child com-

plained about Anirudh, ‘Ma’am, Anirudh is playing with a piano (a mini-

ature toy Casio)’. Ms Sudha demanded of him, ‘Do you come here to

study or what?’ For the teachers, discipline and work constituted the

same thing. It will be seen subsequently that as with disciplining, in

teaching subjects, too, teachers focused on children as ‘do-ers’,16 and

sought to reform them.

Teachers labelled as gande bachche those children who did not score

well in tests and examinations. They viewed these children in an

extremely poor light. When Ms Sudha was returning corrected test cop-

ies to children (by way of throwing the copies at them), she shouted at

Reema, ‘Gandi bachchi, bad girl. Reema Sharma, [you] have not studied

at all’. When Prashant, a top-ranking student, produced ‘incomplete

work’, Ms Sudha lambasted him. Among other things, she also loudly

exclaimed, ‘Sits at the back, so doesn’t work. He is becoming ganda’.

Poor academic performance hinted at the child’s indolence and sloth,

attributes of his/her ‘ganda-ness’.

The choice of high performers as monitors, to assist the teacher in

disciplining the class, also indicated that notions of discipline and class-

room learning were closely knit. Doing well in examinations was reason

enough to elevate a child to a position where he was chosen to oversee

the behaviour of his classmates. Soon after the first-term examinations,

Ms Sudha reappointed the class monitors. After an exchange of good-

morning greetings, she announced,

I am appointing two monitors from [among the] boys. When I am not in class,

he [referring to the first monitor] will mind17 the class. If he is absent, then

the second monitor will mind. From [among the] girls also, there will be two

[monitors]. Now sit down and show me your faces.

With these remarks, the class was ushered into the selection proceed-

ings. Ms Sudha appointed Prashant and Priyank as monitors no. 1 and

Contemporary Education Dialogue, 10, 2 (2013): 163–195

Disciplinary and Pedagogic Practices in a Primary Class 179

no. 2 respectively. They replaced Rahul who had been the class monitor

until then. While selecting girl monitors, Ms Sudha paused for a long

moment before announcing her decision, ‘From [among the] girls,

number 1 is . . .’ The class was abuzz with whispers, ‘Preeti, Preeti . . .’

Ms Sudha chose Gita as monitor no. 1 and Sonali as monitor no. 2. Preeti

was selected as monitor no. 3.

All the appointments were based on high performance in the recent

examinations. Rahul had been stripped off his monitorship because he

had scored poorly in the examinations. The children’s expectation that

Preeti would be appointed as a monitor was also in keeping with this

norm.

Teaching was the epistemological component of the larger agenda of

reform through discipline. Poor academic performance was frowned

upon because it was perceived to be indicative of a child’s lack of effort.

Teachers ‘explained’ poor scores in tests and examinations in terms of a

lack of hard work (does not study) and of the child slipping back into

‘ganda-ness’. In the following sections, it will be seen that teachers con-

structed learning as a silent activity and laid much emphasis on motoric

work and physical labour, that is, drill and practice (which contemporary

theories would consider peripheral, even inconsequential, to learning).

This was consistent with the teachers’ construal of the children as ‘doers’.

There was no mention of thinking, or even of memorising. Indeed,

Ms Sudha explained a girl’s failure in examinations as the result of her

thinking excessively. She said, ‘Prerana does not have any time off from

thinking . . .’ (Usse toh sochne se phursat nahi).

The above-mentioned observations fit in with Foucault’s observations

that discipline was an integral part of the pedagogic exercise in early

modern European schools. The specific practices observed in the study

match with Foucault’s descriptions. According to him, one of the

methods through which disciplinary power is asserted is by

differentiating the students and fitting them into a system of ranks. The

rank of a pupil is indicative of his position within the hierarchy.

Through this process, a hierarchy of ranking is developed, and there is

a distribution of values and merits. Different classes of ranks exist

(from the ‘very good’ rank to the ‘shameful’ rank). By ranking children

thus, they are subject to comparison and hierarchisation. A normalising

gaze is cast upon the pupils, and the abnormal, the deficient and the

deviant are also produced. Such a practice differentiates between pupils

Contemporary Education Dialogue, 10, 2 (2013): 163–195

180 Suvasini Iyer

and further distributes them. The system compels the pupils to conform.

In the observed class, children were ranked along an axis of ‘achche–

gande’, in which the moral-disciplinary dimension of their selves was

confounded with their scholastic performance.

The monitorial system observed in the class (which is also a common-

place practice in Indian schools)18 also recalls Foucault’s description of

surveillance systems that were inbuilt in the pedagogic practices estab-

lished in schools in early modern Europe. Children who scored high in

examinations occupied higher ranks and were therefore recruited as

monitors to keep an eye on other, lower ranking children. Surveillance

was entrenched in the system. All aspects of children’s behaviour were

judged. The normalising gaze left nothing outside of its purview.

Copy-keeping, Neatness and Speed

‘Copy’ was the term employed to refer to notebooks used by children.19

The category ‘copy-keeping’, which emerged during the analysis, sub-

sumed teacher–pupil interactions concerned with the maintenance of

copies. In the observed class, teachers fussed over the meticulous main-

tenance of copies. For children, the conventions of copy-keeping consti-

tuted an integral part of their subject-learning.

Writing was the primary method by which children learned their sub-

jects. It was hence necessary for children to have something on which to

write. At the least, teachers had to ensure that children had something on

which they could write. But the requirements of copy-keeping went

beyond this. Children were asked to possess individual copies for differ-

ent subjects. For each subject, the type of notebook was specified: sin-

gle-lined notebook for Hindi, social studies and science; square-lined

notebook for mathematics and four-lined notebook for English. Even the

size of the copy was specified. Within the study of a subject, different

copies were required for different purposes—class work, homework and

tests. Copies had to be covered with paper, and the student’s name had to

be written on the cover. Teachers could be inflexible, refusing to check

work if it had not been done on the required copy.

In addition, teachers demanded that children follow rigid procedures.

Before starting class work, children had to write the date and inscribe the

heading ‘class work’. Further, they had to write the ‘lesson name’, the

Contemporary Education Dialogue, 10, 2 (2013): 163–195

Disciplinary and Pedagogic Practices in a Primary Class 181

question number as specified in the book or on the blackboard and draw

lines to demarcate one question-and-answer from the next. Teachers

were likely to take serious note of any failure on the part of the children

to follow these norms. When Prashant did not have the date and ‘test’

written on his copy, Ms Sudha slapped him and said, ‘It is the worst error

(that a child could possibly commit)’. Children took these regulations

seriously and were eager to follow them correctly. They queried the

teacher about the order in which the questions are to be answered, and

whether lines should be drawn after each answer. If for some reason a

child did not possess the required notebook, she would tell the teacher

and consult her on what to do. For both the teachers and the students, the

fuss over the copies went beyond the requirements of expediency. It is

the exaggerated concern with such matters (and the relative absence of

concern with ‘real’ learning issues) that is underlined here.

The teachers also overemphasised the importance of neatness of work

and speed. When children were doing their class-work, Ms Dutt moved

around the classroom overseeing their work. Some of her comments on

children’s writing were:

‘The writing should be good . . .’

‘It is written very badly. Work hard. Come back to me after writing beauti-

fully . . .’

In one instance, Ms Sudha refused to check Girish’s copy: ‘I cannot check it

. . . dirty copy’.

Teachers also appeared in a tremendous rush to finish teaching their

quota of the syllabus. Ms Sudha once told her class, ‘I thought I would

finish the fraction chart, you people are so slow . . .’ (the children had not

finished their mathematics test). Ms Das was always in a hurry.

Immediately on entering the classroom, she would take off: ‘Page number

75, page number 75, get me a chalk. Come on, quick’. For teachers to

succeed at completing their work quickly, it was imperative that children

should also increase their pace. Teachers would prod the children to

hurry up. When Sahil was a little slow to begin his English reading,

Ms Sudha was annoyed: ‘Sahil-ji, come on quick. I have to teach also’.

Children were repeatedly urged to work faster: ‘Work quickly, good’.

‘Children, is everyone’s work over? No? Come on, quick, quick’. Speed

was at times emphasised over the actual work itself. Even though some

Contemporary Education Dialogue, 10, 2 (2013): 163–195

182 Suvasini Iyer

children had not completed their tests, Ms Sudha started with the next

activity. ‘Insufficient blackboard space’ was often the immediate cause

for the rush. Teachers often threatened to rub off what was written on the

blackboard and pressed the children to work faster: ‘Quickly, quickly,

note down. I am rubbing off’.

Speed was also an integral part of testing children. Completing the

test within the given time was more important than finishing the task, as

Ms Sudha declared, ‘In two minutes, I will snatch the copies whether a

person’s work is done or not’. She was not joking. There was soon a tus-

sle, as copies were literally snatched away from the children. She

assigned this task to some children who had already finished their test.

Ms Sudha said, ‘How many children’s tests are over? Raise hands. I am

taking away the copies . . . come on . . . .’ Priyank, Gita and Preeti

assisted her, and took away the copies of the other children.

The requirements of copy keeping—neatness, the mandatory tagging

of work with markers such as date and lesson-name, and speedy comple-

tion of work—were intrinsic to everyday activities through which chil-

dren constructed the meaning of classroom learning. Learning became a

set of ‘to do’ skills. In turn, learners became do-ers. In the absence of any

emphasis on mental activity, learning was reduced to a set of atomised

and meaningless actions. The preoccupation with atomised, physical

skills, which construed the learners as do-ers, is consistent with the (ear-

lier discussed) teachers’ foci on children’s bodily selves.

The practices described above also bear similarities to Foucault’s

descriptions of early modern European schools. One of the characteristic

features of the modern elementary school was that it introduced a new

economy of time. Marking a break from earlier traditions, the modern

school system sought to utilise time to the maximum. It worked on the

principle of extracting the maximum amount of work from the smallest

fragment of time. Underpinning this value of the full and productive uti-

lisation of time was the pious notion that it is forbidden by God to waste

time. Pedagogy therefore also sought to regulate work towards an opti-

mum speed. Executing work quickly was an aim of modern schools, and

speed was therefore a virtue.

Under the earlier traditional system of apprenticeship in pre-modern

Europe, the pedagogic arrangement was that a pupil worked for a few

minutes with the master, while the other students remained unattended

and/or idle. In the newer spatial arrangement in the modern school,

Contemporary Education Dialogue, 10, 2 (2013): 163–195

Disciplinary and Pedagogic Practices in a Primary Class 183

where each individual was assigned a specific place, it became possible

for the teacher to simultaneously supervise the work of all individuals.

This made it possible for the pupils to be engaged in work through the

entire duration of the school day.

Another feature of the modern school system was the introduction of

a rigid time schedule. While previously time maintenance had been prac-

tised by religious orders in Europe, in the machinery of the modern

school, the counting of time increased in minutiae, that is, the unit for the

measurement of time became increasingly smaller; time began to be

counted not in hours, but in minutes and seconds. Activities were required

to be executed in a time-bound fashion. Foucault cites an example of a

timetable that was suggested in the early nineteenth century for the

‘mutual improvement of schools’: 8.45 entrance of the monitor, 8.52 the

monitor summons, 8.56 entrance of the children and prayer, and so on

(Foucault, 1977, p. 150). More precise measurement of time made pos-

sible more precise surveillance.

Precise measurement of time also made possible the elaboration of

the pupil’s activity. It could be broken down into chronological steps,

and each step could be assigned a duration, a direction, and an aptitude,

and the order of succession of the steps could be established. For exam-

ple, good handwriting was sought to be achieved by placing the body

parts in specific positions and by operating the body via calculated move-

ments that obeyed an order in time. The relation between the body and

its object (the object it handled and operated upon) was also articulated,

for example, the way in which the pen must be held.

Ariès (1962, pp. 286–314)20 provides a brief history of curriculum

change over the period when modern education was becoming wide-

spread. His descriptions corroborate Foucault’s arguments. For the

purposes of the present study, it is interesting to note that writing was

considered a specialised skill, which remained the preserve of tradi-

tional writers (scribes or scriveners) for a long time. ‘Elementary

schools’ were not permitted to teach it even while they taught children

how to read (Ariès, 1962, pp. 294–297).21 Writing was considered

craftsmanship, and copying by hand and calligraphic writing were

regarded as important to this craft.22 The exaggerated concern with

neatness and beautiful handwriting noted in the present study may have

had its origins in historical circumstances such as those described

earlier.

Contemporary Education Dialogue, 10, 2 (2013): 163–195

184 Suvasini Iyer

Learning as a Silent Activity

In the observed class, learning required children to be silent. The follow-

ing observations support such an understanding. Children could often be

seen in conversation about topics arising from/related to ongoing teach-

ing. On one occasion, Preranarani and two boys were examining the

directions on a map given in the social studies book. Even as Jyoti and

Poonam were working on the social studies class work (chapter: Our

Helpers), they jointly identified the illustration on the page as ‘A

Postman’. They continued to work and talk alongside.

Educationists would argue that such interaction should be encouraged

and utilised for learning (Kumar, 2000; Tudge, 1990). However, in the

observed classroom, children’s voices were the equivalent of white noise

to the teachers’ ears. Teachers did not know what children were really

talking about. They were largely ignorant about the finer nuances of chil-

dren’s talk, a fallout of their indifferent and distant relationship with chil-

dren. This resulted in a lack of differentiation between which talk was

beneficial for learning and which needed recourse to disciplinary action.

They, therefore, reacted to all conversations (including those related to

syllabi learning) with a call for quiet and restoration of order in the class-

room. This translated into creating a repressive regime in the classroom,

silencing even the children’s efforts at negotiating actively with their

work. Passivity was imposed on children, and work was constructed as a

silent activity. As children were writing answers (the subject was Hindi),

Ms Dutt walked around the classroom, ordering the children, ‘No talk-

ing. It is bad to talk. Make pictures without talking. You have to work.

Make [pictures]. Do your work.’

The requirement for silence became very pronounced during tests

when no interaction, with the exception of keeping a check on other stu-

dents, was permitted. Ms Sudha changed the seating arrangement during

an English test to ensure that the children did not interact, ‘Preeti, sit in

the centre. Pranav sit with Akansha. Why do you talk so much? Does

anyone talk during a test?’

Coupling learning with silence created a definition of learning as an

act of individual engagement. Teachers went beyond this, sometimes

even directly encouraging children to be competitive. Ms Sudha coun-

selled a boy during an English test, ‘You hide your work. Otherwise you

will get less [marks], others will get more marks’. Further, classroom

Contemporary Education Dialogue, 10, 2 (2013): 163–195

Disciplinary and Pedagogic Practices in a Primary Class 185

learning was constructed as competitive through the practice of ranking

children on a comparative scale, a scheme that Kohn (1986, pp. 3–5)

defines as a ‘mutually exclusive goal attainment system’. One child get-

ting a high rank necessitated that others got lower ranks. In Kohn’s anal-

ysis, when competition is built into the very structure of the situation, an

artificial scarcity is created. In the context of the observed classroom,

ranking the children created a scarcity of all (referring to various sym-

bolic commodities) that was associated with marks, for example, good-

ness of character, which was very closely associated with obtaining high

marks.

The emphasis that the observed teachers laid on examinations and

on individual performance can be seen to concur with the Foucauldian

understanding that because examinations combine surveillance as

well as the normalising judgement, they have come to occupy a cen-

tral role in the modern schooling institution. While in earlier systems

of guild-apprenticeship, the examination would mark the end of appren-

ticeship, under the new school system in early modern Europe, the

examination was woven into the fabric of the school system. The exam-

ination enabled the teacher to create a specific normative knowledge

about the pupils.

Foucault observed that through examinations, a knowledge base about

individual pupils, their aptitude, and their evolution is developed. Further,

individual pupils are compared, and a science of the normal distribution

of individuals is invented. The examination, therefore, serves to further

subjugate the pupils, and now does so through a discourse that is pur-

portedly scientific.

Therefore, it is not surprising that in the observed setting tests were

construed as individualistic and competitive. Their purpose was to inform

the teachers about the students’ academic or scholastic performance, so

as to ‘scientifically’ differentiate among them.

The Use of the Blackboard

The use of the blackboard is also a measure of how learning was con-

structed in the set-up. The date was written on it every day. The home-

work was also listed on the blackboard. During tests, teachers wrote the

Contemporary Education Dialogue, 10, 2 (2013): 163–195

186 Suvasini Iyer

questions on the board, which children answered individually in their

notebooks. For class work, teachers wrote down the questions and

answers, which children were required to copy down. Any active usage

of the blackboard on the part of the children was limited to asking the

teacher what was written on the board. These observations further indi-

cate how children were rendered passive in the process of acquiring

knowledge in the school.

Subject Pedagogies for Teaching English and Hindi

English was taught using Hindi as the medium of pedagogic communi-

cation. For each chapter, the teacher first explained the meaning of dif-

ficult words, which were given at the beginning of the chapter. This was

followed by the children reading the chapter. The teacher then explained

the lesson and the exercises. Finally, the children wrote answers to the

questions given in the exercises, copying them from the board, where the

teacher had written them.

At every level—the reading of the chapter and the giving of explana-

tions of the chapter and of the exercises—the emphasis was solely on

explaining the meaning of isolated, individual words and the mechanical

algorithms of sentence construction. Children were literally taught ‘how to’

make sentences. There was a conspicuous absence of any attempt to explore

the meaning of the text, as can be seen from the following description.

Ms Sudha was explaining the meaning of the sentences: Once there

was a donkey. He was very lazy. He didn’t like work. One day, he looked

up at the sky. (Central Institute of English, 1972, Lesson 2)

Teacher: Donkey kisse kahte hain? (Who/what is called a donkey?)

Children: Gadha (the Hindi word for donkey).

Teacher: ‘Was’ past hai ya present? (Is ‘was’ used for the past tense or is it

used for the present tense?)

Children: Past.

Teacher: Ek donkey hai ya tha? Kaam karna accha nahi lagta. Kanha dekha?

(A donkey is there or was there? He didn’t like to work. Where did he look?)

The fragmentation of language into meaningless entities and dispa-

rate words and phrases was clearly visible when children were explicitly

Contemporary Education Dialogue, 10, 2 (2013): 163–195

Disciplinary and Pedagogic Practices in a Primary Class 187

told to read by breaking the text (tod-tod ke pado). That this rendered the

text incomprehensible was not a pedagogic concern.

The teaching of Hindi was less reductionist than the teaching of

English. For example, while explaining the meaning of the text and of

the exercises, the teacher went beyond the text to include the children’s

experiences. Text reading was less fragmented than the reading of

English. However, it was the teachers who interpreted the texts. Children’s

participation was limited to gauging their comprehension of what the

teacher had already defined as ‘the knowledge’. Children were given

‘ready-made’ knowledge and then tested on their accumulation of this

knowledge. The following is an example of the teacher explaining an

excerpt from the Hindi text:23

The farmer held some plants and announced, ‘The neighbours have

not come even today. The wheat has ripened even more. I will send my

brothers tomorrow for harvesting them. Come, my son, let us tell them ...’

(Ludra and Verma, 1987, p. 7).

In explaining the above-mentioned passage, Ms Dutt posed the ques-

tion, ‘One’s brother can still be trusted. Whom shall I tell?’

The children replied, ‘Brother’.

When discussing questions from the text, she asked the children,

‘When no one came to help with the harvesting, to whom did the farmer

go?’

The children replied, ‘He went to his brother’.

The pedagogies employed in teaching a subject play an important role

in mediating the meaning of the subject matter for the students (Edwards,

1990; Edwards and Mercer, 1991). Schubauer-Leoni et al. (1989) argues

that scholastic subject matter cannot be considered ‘in abstracto’. Pupils

do not interact with knowledge as an abstract entity. Rather, they con-

struct the ‘meaning’ of the subject through the tasks they undertake in

learning the subject. For the children observed in the classroom, it was in

the fragmented reading of the chapters, listening to teachers’ explana-

tions, ‘knowing’ the correct answers to the questions and copying down

the answers from the blackboard, that the meaning of ‘Hindi’ and

‘English’ was construed. These teaching practices rendered a reduction-

ist interpretation of the subjects. They broke down ‘language’ into a set

of ‘to-do skills’ and a body of inert knowledge that had to be acquired.

This was especially true in the case of English. Children’s role vis-à-vis

this knowledge was that of being passive receivers.

Contemporary Education Dialogue, 10, 2 (2013): 163–195

188 Suvasini Iyer

Next, the following aspects of pedagogy observed in the classroom

are compared with Foucault’s descriptions: copying from the blackboard

and a teaching method that rendered the subject as atomised and that con-

strued learning in terms of behavioural actions alone (a pedagogy that did

not expect the learners to engage with the meaning of the material).

Copying was a common practice in early modern European schools

(copying catechisms in school) and was central to the craftsmanship of

writing. Copying was also a practice prevalent in indigenous pre-British

Indian education, where children copied from religious texts (Nurullah

and Naik, 1951, pp.1–50). In both European and Indian indigenous edu-

cation, reproducing a written text (copying) was central to the develop-

ment of the skill of writing. Therefore, it may be argued that the practice

of copying had antecedents in both the Indian indigenous school system

and in early modern European schooling.

Foucault observes that in the modern European school, parallel to the

meticulous breakdown of time, programmes were organised and

sequenced according to an increasing level of difficulty, and the move-

ment of individuals through the sequence of programmes was noted and

controlled. Such pedagogy meticulously broke down the subject being

taught into its simplest elements, and hierarchised each stage into small

steps. Foucault provides an example in which the process of learning to

read is broken down into seven levels—the first for those who are begin-

ning to learn the letters, the second for those who are learning to spell,

and so on.24 Further subdivisions were introduced to deal with a large

group of students. Such a meticulous articulation of the subject matter,

by breaking it down into a series of steps, also enabled an analogous

organisation of children according to their levels. All this made possible

greater control and surveillance.

In the present study, it was seen that subject learning was broken into

a series of atomised activities. While such reduction rendered the subject

meaningless, it nevertheless made it possible to specify the exact behav-

iour (or utterance) required of children. Such a practice bears a similarity

to Foucault’s descriptions. The outcome of such pedagogy was that it

rendered children as ‘do-ers’, and learning as a set of to-do skills, thereby

enabling greater surveillance and control over children.

The pedagogy observed in the school also did not make any demand on

the learner to engage with the meaning of the text or learning material.

This, too, may be better understood by taking a historical perspective.

Contemporary Education Dialogue, 10, 2 (2013): 163–195

Disciplinary and Pedagogic Practices in a Primary Class 189

Seeking individual interpretations of texts was not a feature of indigenous

Indian schools. In the Western world, too, deriving meaning from texts

was a phenomenon seen only in the post-Enlightenment period (Kumar,

1991, pp. 47–70).

It may thus be concluded that the pedagogic practices observed in the

present study in their near entirety closely resemble the descriptions

given by Foucault.

Children’s Negotiation with the Classroom Culture

Children were ‘bound by the semantic categories’ provided by the teach-

ers. They used them to label each other and to assess themselves. One

boy asked the researcher if Ms Sudha was making a list of achche bac-

che (good children). He wanted to know if his name figured in the list.

His definition of gande bacche included ‘those who do not study’.

The interaction between monitors and other students also seemed to

mirror the teacher–student interaction. One monitor admonished an

errant child, ‘One stands and drinks water, or does one sit and drink

water?’ Children also ascribed the teacher’s status to the monitors, seek-

ing clarifications from them and complaining to them about other chil-

dren. When Varun was monitoring, Priyank pointed out to him, ‘Varun,

you are minding. [See] who is talking with Preeti’.

Theorists such as Mead argue that the child’s early life is critical in

developing a sense of self as well as a sense of what constitutes the world

(Berger and Luckmann, 1967; Mead, 1964, pp. 199–246). It is through

day-to-day interaction with significant others that such a sense is devel-

oped. In the observed class, the children’s use of markers such as gande

bachhe as well as their reproduction of dominant values in spontaneous

interaction are both suggestive of their appropriation of the normative

values of their class.

Concluding Remarks

It may be concluded that in the observed class, disciplining and teaching

practices sought to create docile and obedient bodies. The surveillance of

Contemporary Education Dialogue, 10, 2 (2013): 163–195

190 Suvasini Iyer

children was integrated into the pedagogic activities of the teachers. In this

section, the implications and significance of these findings are discussed.

Before doing so, it must be noted that the above-discussed analysis is

based on a limited sample. The Indian schooling system is vast and

diverse, and different categories of schools exist, catering to different

strata of the population. The varied school system also incorporates a

variety of practices. Therefore, based on such limited ethnographic data,

it is not possible to comment on the pedagogic practices of Indian schools

and classes in general. With this cautionary note, an attempt is made here

to further understand the chief finding of the study, namely that peda-

gogic practices in an Indian classroom in contemporary times bear con-

siderable similarity to the descriptions of school systems in early modern

Europe given by Foucault and Ariès.

While the findings of the study cannot be taken to represent Indian

classrooms, it is nevertheless useful to note that similar observations have

been made by others. In her study on village primary schools in a location

on the outskirts of Delhi, Sarangapani (2003) found that success or failure

was seen as an attribute of a child’s cognitive–moral make-up. In the dis-

course of the school, the two were conjoined. Failure to perform assigned

tasks could lead to punitive action. Success in performing school tasks

could be rewarded by the appointment of such students as monitors, who

were given temporary moral-disciplinary rights over the other children.

Kumar’s (1991) comments on pedagogy and disciplinary practices in

Indian schools also resonate with the findings of the present study.

Therefore, it may be concluded that the observations made in the

present study are not altogether unique. Others have also noted similar

practices in other schools and among other teachers. Furthermore, if one

examines certain English words used in the classroom, it leads one to

infer that the practices they invoke cannot be unique to the classroom

observed. These words are discipline, control, monitor, copy and mind.

Simply put, the specific teachers observed could not have invented them;

they drew from the pool of shared language available in the shared cul-

ture. Moreover, a deeper probing into the meaning of these words in

colloquial usage reveals, in fact, that they connote meanings and inten-

tions that were prevalent in the early modern European school system (as

described in the writings of Foucault and Ariès). This strengthens the

conclusion that the similarities in the pedagogic practices observed in the

school and those noted by Foucault and Ariès are not coincidental.

Contemporary Education Dialogue, 10, 2 (2013): 163–195

Disciplinary and Pedagogic Practices in a Primary Class 191

An argument that has been considered at various points in the article

is whether the disciplinary and pedagogic practices are, as Kumar argues,

in continuity with pedagogic practices that came to dominate Indian

schools as an outcome of (a) specific British administrative policies and

(b) the civilising and reforming mission that underlay British educational

efforts. The present study hints at an additional nuance to the above-

mentioned understanding, which is perhaps worth further exploration.

Specifically, the study argues that

a. Disciplining should be seen not as an isolated concern. In the

school observed, disciplining was integral to a pedagogy that was

geared towards maintaining surveillance.

b. A Foucauldian perspective is helpful in understanding pedagogic

practices.

c. The complete package of specific pedagogic practices that was

observed in the study—an overemphasis on discipline, a focus on

maintaining physical order and bodily control, an agenda of

reforming children, the integration of discipline with subject

teaching-learning, the fuss over neatness and speed, and the

stress on atomised skills and inert knowledge within the subject

pedagogies—may have been positively and directly inherited

from the schooling practices of early modern Western Europe,

rather than being an indirect and adjunct consequence of British

administrative policies. Specifically, when Europeans set up

schools in India, they may have brought with them pedagogic

practices prevalent in their countries. These may have continued

to last even till contemporary times. Such practices may not

‘make sense’ when seen through a contemporary lens, especially

if the latter is informed by liberal–rational–humanist perspec-

tives. However, in their day and time, they may have appeared to

be sensible, even natural.

One question arises here: why has such pedagogy continued to persist

over a span of more than a century? Or, why have the waves of progres-

sive pedagogy not led to the gradual extinction of the older pedagogy?

While these are important questions, finding answers to them remains

beyond the scope of this study. The article has, however, provided a new

perspective within which to posit these questions.

Contemporary Education Dialogue, 10, 2 (2013): 163–195

192 Suvasini Iyer

For the moment, it would suffice to conclude by noting that in the

observed class, the pedagogies were directed towards creating obedient

and docile bodies. A normalising gaze had been cast over the children.

Children, in turn, were found to have internalised the normative gaze.

Notes

1. The study was undertaken under the supervision of Professor Poonam Batra.

A complete copy of the thesis, titled ‘Evolving a framework for classroom

inquiry with a specific focus on teaching-learning processes’, may be

obtained from the library at the Central Institute of Education, Department

of Education, University of Delhi (Suvasini, 2001). I thank Professor Batra

and two anonymous reviewers for their comments and suggestions on the

article. I also thank Mr Saswata Ghosh for useful discussions on Foucault.

2. At the time the study was conducted, it was not yet obligatory for schools

to provide cooked meals to children. Under the National Programme for

Nutritional Support to Primary Education, launched in 1995, government

schools in Delhi provided children with ready-to-eat food items such as

biscuits and seasonal fruits (Sharma et al., 2006).

3. The textbook used for teaching English was Book Three, Special Series of

the English Reader Let’s Learn English, prepared by the Central Institute

of English, Hyderabad in 1972. For the other subjects, NCERT (National

Council of Educational Research and Training) books were used. The various

guiding objectives of the books included teaching of language structure and

vocabulary (English textbook); training the child to think, reason, analyse

and articulate logically (Mathematics textbook, NCERT, 1987); inculcating

values such as a sense of responsibility for the group and reverence for

teachers (Hindi textbook, Ludra and Verma, 1987); and understanding and