Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Correlation Between Modified LEMON Score and Intub

Uploaded by

Esteban TapiaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Correlation Between Modified LEMON Score and Intub

Uploaded by

Esteban TapiaCopyright:

Available Formats

Ji et al.

World Journal of Emergency Surgery (2018) 13:33

https://doi.org/10.1186/s13017-018-0195-0

RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access

Correlation between modified LEMON

score and intubation difficulty in adult

trauma patients undergoing emergency

surgery

Sung-Mi Ji1, Eun-Jin Moon2, Tae-Jun Kim2, Jae-Woo Yi2, Hyungseok Seo2* and Bong-Jae Lee2

Abstract

Background: Prediction of difficult airway is critical in the airway management of trauma patients. A LEMON

method which consists of following assessments; Look-Evaluate-Mallampati-Obstruction-Neck mobility is a fast and

easy technique to evaluate patients’ airways in the emergency situation. And a modified LEMON method, which

excludes the Mallampati classification from the original LEMON score, also can be used clinically. We investigated

the relationship between modified LEMON score and intubation difficulty score in adult trauma patients undergoing

emergency surgery.

Methods: We retrospectively reviewed electronic medical records of 114 adult trauma patients who underwent

emergency surgery under general anesthesia. All patients’ airways were evaluated according to the modified LEMON

method before anesthesia induction and after tracheal intubation; the intubating doctor self-reported the intubation

difficulty scale (IDS) score. A difficult intubation group was defined as patients who had IDS scores > 5.

Results: The modified LEMON score was significantly correlated with the IDS score (P < 0.001). The difficult intubation

group showed higher modified LEMON score than the non-difficult intubation group (3 [2-5] vs. 2 [1-3], respectively,

P = 0.017). Limited neck mobility was the only independent predictor of intubation difficulty (odds ratio, 6.15; P = 0.002).

Conclusion: The modified LEMON score is correlated with difficult intubation in adult trauma patients undergoing

emergency surgery.

Keywords: Airway, Difficult intubation, Emergency surgery, LEMON score, Trauma

Background airway securing devices or experienced staffs, such a

Successful airway securement by an experienced phys- situation that some devices or staffs are unavailable tem-

ician is crucial in the management of trauma patient [1]. porarily can be possible. Thus, prediction of the difficult

However, compared with other types of patients requir- airway and preparing appropriate device or staffs is crit-

ing tracheal intubation, trauma patients have a higher ical in the airway management of trauma patients.

risk of intubation difficulty [2]. In trauma patients re- Conventional tools for predicting difficult airway, such

quiring emergency surgery, there may not have enough as the Mallampati score, have a limited application in

time to evaluate patient’s airway, thereby being an in- trauma patients [3]. The LEMON method, which

creased risk of the unanticipated difficult airway. Fur- consists of following assessments: Look-Evaluate-Mal-

thermore, because of the limited number of advanced lampati-Obstruction-Neck mobility, can be used to pre-

dict difficult intubation in the emergency setting [4], and

the modified LEMON score (also called “LEON” score),

* Correspondence: seohyungseok@gmail.com

2

Department of Anesthesiology and Pain Medicine, Kyung Hee University

which excludes the Mallampati classification from the

Hospital at Gangdong, College of Medicine, Kyung Hee University, Seoul original LEMON score, has been developed for the iden-

05278, South Korea tification of difficult airways [5].

Full list of author information is available at the end of the article

© The Author(s). 2018 Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0

International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and

reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to

the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver

(http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Content courtesy of Springer Nature, terms of use apply. Rights reserved.

Ji et al. World Journal of Emergency Surgery (2018) 13:33 Page 2 of 6

In the present study, we retrospectively investigated according to the institution’s routine clinical practice.

the ability of the LEON score to predict intubation diffi- Anesthesia was induced with propofol (1 to 2 mg/kg)

culty by assessing the correlation between the LEON and maintained with volatile anesthetics, such as sevo-

score and intubation difficulty score in adult trauma pa- flurane or desflurane. Target-controlled infusions of

tients undergoing emergency surgery. propofol and remifentanil were used. A neuromuscular

blocking agent (NMBA), rocuronium bromide (0.6 mg/kg),

Methods was administered to facilitate tracheal intubation.

Patients Initially, tracheal intubation was performed by using a

After the approval of the institutional review board direct laryngoscope or video laryngoscope based on the

(approval number: 2016-11-014), electronic medical re- intubating doctor’s choice; however, a lightwand device

cords of adult trauma patients who underwent emer- or fiberoptic bronchoscopy was also used in cases of

gency surgery under general anesthesia in an operating failed first attempt or difficult intubation. After tracheal

theater between March 2016 and August 2016 were intubation, the intubating doctor self-reported in the

reviewed retrospectively. Patients who were already electronic medical records using the intubation diffi-

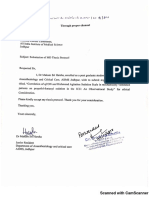

intubated before anesthesia induction or underwent culty scale (IDS; Fig. 1, right) as follows: N1, the num-

surgical procedures under regional anesthesia were ber of supplementary intubation attempts; N2, the

excluded. number of supplementary operators; N3, the number of

alternative intubation techniques used; N4, glottic ex-

Data collection posure as defined by the Cormack and Lehane grade

All patients’ airways were evaluated by the well-trained (grade 1, N4 = 0; grade 2, N4 = 1; grade 3, N4 = 2; grade

residents or attending members of staff of the 4, N4 = 3); N5, the lifting force applied during laryngos-

anesthesia department before anesthesia induction. Pa- copy (N5 = 1 if a subjectively increased lifting force was

tient’s airway assessment was performed according to required); N6, external laryngeal pressure to improve

the LEON method (Fig. 1, left) as follows: (1) Look, glottic exposure (N6 = 1 if external laryngeal pressure

look at the patient externally for characteristics that are was required); and N7, position of the vocal cords at

known to cause difficult laryngoscopy, intubation, or intubation (N7 = 0 if vocal cords in abduction or

ventilation—in the LEON method, “Look” criteria as- were not visualized; N7 = 1 if vocal cords in adduc-

sesses for presence of four features (facial trauma, large tion or blocking the tube passage). The IDS score is

incisors, beard or mustaches, and large tongue); (2) the sum of N1 through N7. An IDS score between 1

evaluate the 3-3-2 rule—assess the alignment of the and 5 represents slight difficulty, and IDS score > 5

pharyngeal, laryngeal, and oral axes; (3) obstruction— represents moderate to major difficulty. In the present

presence of any conditions that can cause airway ob- study, patients were divided into the difficult intub-

struction; and (4) neck mobility—assess for the pres- ation group (group D) and non-difficult intubation

ence of limited neck mobility or use of a hard neck group (group ND) according to whether their IDS

collar immobilizer. General anesthesia was performed score was > 5 or ≤ 5.

Fig. 1 Modified LEMON (LEON) score and intubation difficulty scale score

Content courtesy of Springer Nature, terms of use apply. Rights reserved.

Ji et al. World Journal of Emergency Surgery (2018) 13:33 Page 3 of 6

Statistical analysis time was also longer in group D than in group ND (50

All analyses were performed using MedCalc® 16.2 [27–80] vs. 17 [13–25] seconds, P < 0.001).

(MedCalc Software, Ostend, Belgium). Continuous vari- The LEON score was higher in group D than in group

ables were compared using the Student’s t test or ND (3 [2–5] vs. 2 [1–3], P = 0.017) (Fig. 2). The inci-

Mann-Whitney U test. Categorical variables were ana- dence of difficult intubation tended to increase as the

lyzed using a chi-square test, and the Cochran-Armitage LEON score increased (P = 0.005). The logistic regres-

test was used for trend analysis. Correlation between the sion analysis showed that the LEON score showed a sig-

LEON score and IDS was calculated using the Spear- nificant correlation with intubation difficulty (odds ratio,

man’s rank correlation. To determine the relationship 1.55; 95% confidence interval, 1.12–2.14, P = 0.008).

between one dependent factor and one or more inde- Among the variables in the LEON score, limited neck

pendent factors, a logistic regression analysis was per- mobility was the only independent predictor of intub-

formed. Data are expressed as means ± standard ation difficulty (odds ratio, 6.15: 95% confidence interval,

deviations, medians [interquartile ranges], or number 1.909–19.819; P = 0.002) (Table 2).

(%). P < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Discussion

Results In the present study, we found that the LEON score corre-

During study period, a total of 114 cases were reviewed. lated with the intubation difficulty and a LEON score of

Patients’ characteristics are shown in Table 1. There ≥3 could predict intubation difficulty in trauma patients.

were no differences with respect to the demographic Airway management is a challenging issue in adult

data and type of injury between group D and group ND. trauma patients. Trauma patients may present with a

There was no patient who had unsuccessful intubation. variety of airway difficulties, ranging from promptly

Direct laryngoscope, video laryngoscope, lightwand de- recognized to unanticipated difficult airways [6]. More-

vice, and fiberoptic bronchoscope were used in 96, 17, 5, over, most of trauma patients requiring emergency sur-

and 5 patients (84, 15, 4, and 4%, respectively). gery do not have adequate time to undergo full

The LEON score was significantly correlated with the IDS preoperative airway evaluation; thus, they can be at an

score (Spearman’s correlation coefficient: 0.333, P < 0.001). increased risk of unanticipated difficult airway. [4, 7]

The IDS score was 6 [6, 7] in group D, and it was 1 Therefore, it is crucial to be able to conduct a prompt

[0–3] in group ND (P < 0.001). The Cormack-Lehane assessment of the airway and predict difficult intub-

grade was significantly higher in group D than in group ation. The LEMON score has been effectively used in

ND (3 [3, 4] vs. 1 [1, 2], P < 0.001). The number of in- emergency departments to predict difficult intubation

tubation attempts was higher in group D than in group because it can be determined based on the patient’s ap-

ND (2 [1, 2] vs. 1 [1], P < 0.001). The median intubation pearance and observer’s fingerbreadth, and it does not

Table 1 Patients’ characteristics

Variables Overall Group ND (n = 96) Group D (n = 18) P

Age (year) 53 [38–61] 52 [18–83] 56 [19–84] 0.492

Sex (male %) 87 (76.3%) 73 (76.0%) 14 (77.8%) 0.874

Height (cm) 168.0 [162.8–175.0] 168.5 [163.0–175.0] 168.0 [159.5–174.3] 0.969

Weight (kg) 68.5 [57.0–75.0] 68.0 [57.0–75.0] 70.0 [57.3–75.8] 0.676

2

BMI (kg/m ) 23.4 [21.1–25.1] 23.3 [21.0–25.1] 24.0 [22.3–25.7] 0.616

Type of injury

Head and neck 34 (29.8%) 28 (29.2%) 6 (33.3%) 0.728

Chest 7 (6.1%) 6 (6.2%) 1 (5.6%) 0.923

Abdomen 7 (6.1%) 5 (5.2%) 2 (11.1%) 0.341

Spine 10 (8.8%) 8 (8.3%) 2 (11.1%) 0.701

Pelvis 4 (3.5%) 4 (4.2%) 0 (0%) 0.378

Extremities 52 (45.6%) 45 (46.9%) 7 (38.9%) 0.534

Data are expressed as medians [IQRs] or numbers (%)

Group ND: patients show intubation difficulty score ≤ 4

Group D: patients show intubation difficulty score > 5

Head and neck injury includes trauma to the head, facial area, and cervical spine

Spine injury indicates injury of thoracic and lumbar vertebra with/without neurologic complication

BMI body mass index

Content courtesy of Springer Nature, terms of use apply. Rights reserved.

Ji et al. World Journal of Emergency Surgery (2018) 13:33 Page 4 of 6

Fig. 2 Comparison of the modified LEMON (LEON) scores between group ND and group D. Patients in group ND shows intubation difficulty

score ≤ 4 and patients in group D shows > 5. The modified LEMON score was 2 [1–3] in group ND and 3 [2–5] in group D (P = 0.017)

require special cut-off values or additional measure- intubation as IDS score > 5 [2, 10]. By using the IDS,

ment tools [5, 8]. The Mallampati score component in the severity of difficult intubation could be quantified;

the LEMON score is difficult to assess in trauma pa- this enabled an analysis of the correlation between

tient [7]; therefore, the LEON score, which excludes the LEON score and intubation difficulty, which can sug-

Mallampati score, has been used effectively in clinical gest a cut-off value of LEON score in predicting diffi-

situations [5, 9]. Although the LEON score has been cult intubation.

validated and widely used in emergency departments, It has been previously well-validated that the LEON

the definitions of difficult intubation in previous studies score can effectively predict difficult intubation in the

were ambiguous (i.e., difficult tracheal intubation: tra- emergency department [9]. However, comparing with

cheal intubation that requires multiple attempts in the previous report that showed the median value of the

presence or absence of tracheal pathology). In the LEON score was 1 in both the easy and difficult intub-

present study, we used the IDS and defined a difficult ation group [5], our results showed that the median

Table 2 The incidence of each variables of modified LEMON (LEON) score and the correlation of each variables with the intubation

difficulty

Variables Overall Group ND (n = 96) Group D (n = 18) Odds ratio 95% Confidence interval P

Facial trauma, n (%) 32 (28.1%) 27 (281%) 5 (27.8%) 0.983 0.320–3.022 0.976

Large incisors, n (%) 9 (7.9%) 6 (6.2%) 3 (16.7%) 3.000 0.676–13.309 0.148

Beard or mustache, n (%) 17 (14.9%) 12 (12.5%) 5 (27.8%) 2.692 0.814–8.900 0.105

Large tongue, n (%) 16 (14.0%) 11 (11.5%) 5 (27.8%) 2.972 0.888–9.943 0.077

Inter-incisor distance < 3 FBs, n (%) 49 (43.0%) 39 (40.6%) 10 (55.6%) 1.827 0.662–5.041 0.245

Hyoid-to-mental distance < 3 FBs, n (%) 33 (28.9%) 28 (29.2%) 5 (27.8%) 0.934 0.304–2.867 0.905

Thyroid-to-hyoid distance < 2 FBs, n (%) 48 (42.1%) 39 (40.6%) 9 (50.0%) 1.462 0.533–4.012 0.461

Obstruction signs, n (%) 30 (26.3%) 22 (22.9%) 8 (44.4%) 2.691 0.947–7.647 0.063

Limited neck mobility, n (%) 16 (14.0%) 9 (9.4%) 7 (38.9%) a

6.152 1.909–19.821 0.002

a

P = 0.001 compared with group ND

Group ND indicates patients show intubation difficulty score ≤ 4 and group D indicates patients show intubation difficulty score > 5

P value indicates the significance of univariable logistic regression between each variables and intubation difficulty

Obstruction signs indicate the presence of any conditions such as epiglottitis, peritonsillar abscess, sleep apnea, or upper airway trauma

FB finger breadth

Content courtesy of Springer Nature, terms of use apply. Rights reserved.

Ji et al. World Journal of Emergency Surgery (2018) 13:33 Page 5 of 6

value of the LEON score was 3 in the difficult intub- Conclusion

ation group and 2 in the non-difficult intubation group. The LEON score may be used as one of the evidence

Moreover, our results showed that limited neck mobil- predicting difficult airway, thereby being helpful to in-

ity is an independent predictor of difficult intubation; crease safety in the airway management of adult

this is in contrast with the results of a previous study trauma patients undergoing emergency surgery. A pa-

that showed the thyroid-to-hyoid distance was not an tient with LEON score ≥ 3 may have the possibility of

independent predictor of difficult intubation. We difficult intubation, and even in using video laryngos-

thought that this difference may be because of our copy, the limited neck mobility may contribute to the

study population, particularly the high proportion of intubation difficulty.

patients with head and neck injury. Head and neck in-

Abbreviation

jury is frequently associated with cervical spine injury IDS: Intubation difficulty scale; NMBA: Neuromuscular blocking agent

[11, 12], and neck immobilization should be considered

even without a definite cervical spine injury [13]. The Funding

point in the criteria of limited neck mobility may have There are no funding sources for the present case report.

contributed to a higher LEON score in this study than Availability of data and materials

that reported in the previous study. Moreover, limited The datasets of the current study are available from the corresponding author

neck mobility, which was found to be an independent on reasonable request.

predictor of difficult intubation in the present study,

Authors’ contributions

may also provide evidence supporting the importance SMJ contributed in the interpretation of the data and drafting of the manuscript.

of neck mobility in the airway management of trauma EJM took part in the data analysis and critical revision. TJK had a hand in the data

patients. The thyroid-to-hyoid distance, despite its interpretation and statistical analysis. HS played a part in the study concept and

design, interpretation of the data, statistical analysis, critical revision of the

clinical significance in a previous study [5], did not sig- manuscript, and study supervision. JWY and BJL helped in the study concept,

nificantly contribute the difficult intubation in this critical revision, and study supervision. All authors read and approved the final

study, and the use of video laryngoscope may have af- manuscript.

fected this observation. Compared with direct laryngo- Ethics approval and consent to participate

scope, a video laryngoscope can provide an extended The present study was approved by Dankook University Hospital Institutional

view in the vertical plane, which offers an advantage in Review Board (approval number: 2016-11-014). A written informed consent

from the patient was waived because the present study was performed

cases of an anteriorly placed larynx [14]. A video laryn- retrospectively.

goscope was used for the initial intubation attempt in

15% of the subjects, which may be large enough to at- Consent for publication

A written informed consent from the participants for publication of this article

tenuate the influence of the thyroid-to-hyoid distance

and any accompanying tables/images was waived.

in tracheal intubation.

This study has several limitations. First, the study Competing interests

was conducted with a retrospective design via analysis The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

of electronic medical records. Although the intubating

doctor recorded the intubation information right after Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published

the induction of anesthesia, the data may have been maps and institutional affiliations.

unreliable because they were self-reported data. More-

over, because the initial intubation device can be se- Author details

1

Department of Anesthesiology and Pain Medicine, College of Medicine,

lected by intubator’s choice, a selection bias may Dankook University, Cheonan, South Korea. 2Department of Anesthesiology

affect the result. A relatively small population for a and Pain Medicine, Kyung Hee University Hospital at Gangdong, College of

retrospective study also contributes to the result. Medicine, Kyung Hee University, Seoul 05278, South Korea.

Second, the results of the present study do not reflect Received: 29 May 2018 Accepted: 17 July 2018

patients with very severe and complex traumatic in-

juries that require immediate airway access. Because

we evaluated patients undergoing emergency surgery References

1. Langeron O, Birenbaum A, Amour J. Airway management in trauma.

in the operating theater, patients who underwent im- Minerva Anestesiol. 2009;75:307–11.

mediate tracheal intubation in the emergency depart- 2. Adnet F, Racine SX, Borron SW, Clemessy JL, Fournier JL, Lapostolle F, Cupa

ment were not included. Third, we used NMBA to M. A survey of tracheal intubation difficulty in the operating room: a

prospective observational study. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2001;45:327–32.

facilitate tracheal intubation in the present study. 3. Levitan RM, Everett WW, Ochroch EA. Limitations of difficult airway

Since NMBA can provide the relaxation of soft tissues prediction in patients intubated in the emergency department. Ann Emerg

and comfortable condition without patient move- Med. 2004;44:307–13.

4. Reed MJ, Dunn MJ, McKeown DW. Can an airway assessment score predict

ments, the IDS score can be differed in clinical situa- difficulty at intubation in the emergency department? Emerg Med J. 2005;

tions of tracheal intubation without NMBA. 22:99–102.

Content courtesy of Springer Nature, terms of use apply. Rights reserved.

Ji et al. World Journal of Emergency Surgery (2018) 13:33 Page 6 of 6

5. Soyuncu S, Eken C, Cete Y, Bektas F, Akcimen M. Determination of difficult

intubation in the ED. Am J Emerg Med. 2009;27:905–10.

6. Walls RM. Management of the difficult airway in the trauma patient. Emerg

Med Clin North Am. 1998;16:45–61.

7. Bair AE, Caravelli R, Tyler K, Laurin EG. Feasibility of the preoperative

Mallampati airway assessment in emergency department patients. J Emerg

Med. 2010;38:677–80.

8. Mayglothling J, Duane TM, Gibbs M, McCunn M, Legome E, Eastman AL,

Whelan J, Shah KH. Eastern Association for the Surgery of T. Emergency

tracheal intubation immediately following traumatic injury: an Eastern

Association for the Surgery of Trauma practice management guideline. J

Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2012;73:S333–40.

9. Hagiwara Y, Watase H, Okamoto H, Goto T, Hasegawa K. Japanese

emergency medicine network I. Prospective validation of the modified

LEMON criteria to predict difficult intubation in the ED. Am J Emerg Med.

2015;33:1492–6.

10. Adnet F, Borron SW, Racine SX, Clemessy JL, Fournier JL, Plaisance P,

Lapandry C. The intubation difficulty scale (IDS): proposal and evaluation of

a new score characterizing the complexity of endotracheal intubation.

Anesthesiology. 1997;87:1290–7.

11. Hackl W, Hausberger K, Sailer R, Ulmer H, Gassner R. Prevalence of cervical

spine injuries in patients with facial trauma. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol

Oral Radiol Endod. 2001;92:370–6.

12. Mukherjee S, Abhinav K, Revington PJ. A review of cervical spine injury

associated with maxillofacial trauma at a UK tertiary referral centre. Ann R

Coll Surg Engl. 2015;97:66–72.

13. Austin N, Krishnamoorthy V, Dagal A. Airway management in cervical spine

injury. Int J Crit Illn Inj Sci. 2014;4:50–6.

14. Sulser S, Ubmann D, Schlaepfer M, Brueesch M, Goliasch G, Seifert B, Spahn

DR, Ruetzler K. C-MAC videolaryngoscope compared with direct

laryngoscopy for rapid sequence intubation in an emergency department: a

randomised clinical trial. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2016;33:943–8.

Content courtesy of Springer Nature, terms of use apply. Rights reserved.

Terms and Conditions

Springer Nature journal content, brought to you courtesy of Springer Nature Customer Service Center GmbH (“Springer Nature”).

Springer Nature supports a reasonable amount of sharing of research papers by authors, subscribers and authorised users (“Users”), for small-

scale personal, non-commercial use provided that all copyright, trade and service marks and other proprietary notices are maintained. By

accessing, sharing, receiving or otherwise using the Springer Nature journal content you agree to these terms of use (“Terms”). For these

purposes, Springer Nature considers academic use (by researchers and students) to be non-commercial.

These Terms are supplementary and will apply in addition to any applicable website terms and conditions, a relevant site licence or a personal

subscription. These Terms will prevail over any conflict or ambiguity with regards to the relevant terms, a site licence or a personal subscription

(to the extent of the conflict or ambiguity only). For Creative Commons-licensed articles, the terms of the Creative Commons license used will

apply.

We collect and use personal data to provide access to the Springer Nature journal content. We may also use these personal data internally within

ResearchGate and Springer Nature and as agreed share it, in an anonymised way, for purposes of tracking, analysis and reporting. We will not

otherwise disclose your personal data outside the ResearchGate or the Springer Nature group of companies unless we have your permission as

detailed in the Privacy Policy.

While Users may use the Springer Nature journal content for small scale, personal non-commercial use, it is important to note that Users may

not:

1. use such content for the purpose of providing other users with access on a regular or large scale basis or as a means to circumvent access

control;

2. use such content where to do so would be considered a criminal or statutory offence in any jurisdiction, or gives rise to civil liability, or is

otherwise unlawful;

3. falsely or misleadingly imply or suggest endorsement, approval , sponsorship, or association unless explicitly agreed to by Springer Nature in

writing;

4. use bots or other automated methods to access the content or redirect messages

5. override any security feature or exclusionary protocol; or

6. share the content in order to create substitute for Springer Nature products or services or a systematic database of Springer Nature journal

content.

In line with the restriction against commercial use, Springer Nature does not permit the creation of a product or service that creates revenue,

royalties, rent or income from our content or its inclusion as part of a paid for service or for other commercial gain. Springer Nature journal

content cannot be used for inter-library loans and librarians may not upload Springer Nature journal content on a large scale into their, or any

other, institutional repository.

These terms of use are reviewed regularly and may be amended at any time. Springer Nature is not obligated to publish any information or

content on this website and may remove it or features or functionality at our sole discretion, at any time with or without notice. Springer Nature

may revoke this licence to you at any time and remove access to any copies of the Springer Nature journal content which have been saved.

To the fullest extent permitted by law, Springer Nature makes no warranties, representations or guarantees to Users, either express or implied

with respect to the Springer nature journal content and all parties disclaim and waive any implied warranties or warranties imposed by law,

including merchantability or fitness for any particular purpose.

Please note that these rights do not automatically extend to content, data or other material published by Springer Nature that may be licensed

from third parties.

If you would like to use or distribute our Springer Nature journal content to a wider audience or on a regular basis or in any other manner not

expressly permitted by these Terms, please contact Springer Nature at

onlineservice@springernature.com

You might also like

- Jurnal Wulan Mulyani 21360095Document18 pagesJurnal Wulan Mulyani 21360095Rizki DamayantiNo ratings yet

- Comparison of MMS and CL GradingDocument8 pagesComparison of MMS and CL GradingIndhu SubbuNo ratings yet

- Sakle S 2017Document9 pagesSakle S 2017AldyUmasangadjiNo ratings yet

- Ulbt X Mallampati Preditor de VadDocument6 pagesUlbt X Mallampati Preditor de VadAndre RibeiroNo ratings yet

- Imedpub Journals 2018 2018Document6 pagesImedpub Journals 2018 2018jemyNo ratings yet

- Document PDFDocument7 pagesDocument PDFsiti hazard aldinaNo ratings yet

- Studyprotocol Open Access: Sung Hye Byun, Soo Jin Kim and Eugene KimDocument7 pagesStudyprotocol Open Access: Sung Hye Byun, Soo Jin Kim and Eugene Kimsiti hazard aldinaNo ratings yet

- Proceedings of Singapore Healthcare 2016 Wong 19 26Document8 pagesProceedings of Singapore Healthcare 2016 Wong 19 26Aristiyan LuthfiNo ratings yet

- NehshebajakaDocument14 pagesNehshebajakanuraenikhasanah98No ratings yet

- s13049 019 0599 1 PDFDocument9 pagess13049 019 0599 1 PDFDeby WicaksonoNo ratings yet

- Difficult Airway Management During Anesthesia A Review of The Incidence and SolutionsDocument6 pagesDifficult Airway Management During Anesthesia A Review of The Incidence and SolutionsSudar Pecinta ParawaliNo ratings yet

- LEMON Eur J Emerg Med 2005Document4 pagesLEMON Eur J Emerg Med 2005TGB LEGENDNo ratings yet

- Art 12Document8 pagesArt 12Gabriela GarciaNo ratings yet

- Airway Management For Induction of General Anesthesia - UpToDate - Be4225b0Document31 pagesAirway Management For Induction of General Anesthesia - UpToDate - Be4225b0Nitin TrivediNo ratings yet

- Jurding WulanDocument10 pagesJurding Wulanmaudi fitriantiNo ratings yet

- PIIS0007091218300400Document13 pagesPIIS0007091218300400Marina BotrasNo ratings yet

- 10 1111@anae 12955Document10 pages10 1111@anae 12955Cuenta LastNo ratings yet

- Predictor Difficult Intubation BJADocument0 pagesPredictor Difficult Intubation BJALovely GaluhNo ratings yet

- Early Identification of Patients at Risk For Difficult Intubation in The Intensive Care UnitDocument9 pagesEarly Identification of Patients at Risk For Difficult Intubation in The Intensive Care UnitAlfredoNoriegaPonceeNo ratings yet

- Jurnal KardioDocument5 pagesJurnal KardiomadeNo ratings yet

- A Retrospective Study of Success, Failure, and Time Needed To Perform Awake IntubationDocument10 pagesA Retrospective Study of Success, Failure, and Time Needed To Perform Awake IntubationAinun RamadaniNo ratings yet

- Awake Laser Laryngeal Stenosis Surgery, 2020Document5 pagesAwake Laser Laryngeal Stenosis Surgery, 2020Araceli BarreraNo ratings yet

- A Comparison of Postoperative Respiratory Complications Associated With The Use of Desflurane and Sevoflurane: A Single-Centre Cohort StudyDocument9 pagesA Comparison of Postoperative Respiratory Complications Associated With The Use of Desflurane and Sevoflurane: A Single-Centre Cohort StudyPaloma LizardiNo ratings yet

- Nej MR A 1916801Document12 pagesNej MR A 1916801bagholderNo ratings yet

- Emergency Inguinal Hernia Repair Under Local Anesthesia: A 5-Year Experience in A Teaching HospitalDocument5 pagesEmergency Inguinal Hernia Repair Under Local Anesthesia: A 5-Year Experience in A Teaching HospitalleonardoNo ratings yet

- Articulo en InglesDocument20 pagesArticulo en InglesJavier VivarNo ratings yet

- Predicting Difficult Airways 2009Document4 pagesPredicting Difficult Airways 2009Ricardo RiosNo ratings yet

- DISEDocument4 pagesDISEMichael ANo ratings yet

- Medicine: Airway Management in Patients With Deep Neck InfectionsDocument6 pagesMedicine: Airway Management in Patients With Deep Neck InfectionsJavier VolinierNo ratings yet

- Validation of Modified Mallampati Test With Addition of Thyromental Distance and Sternomental Distance To Predict Difficult Endotracheal Intubation in AdultsDocument5 pagesValidation of Modified Mallampati Test With Addition of Thyromental Distance and Sternomental Distance To Predict Difficult Endotracheal Intubation in AdultsEugenio Daniel Martinez HurtadoNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0104001421002724 MainDocument7 pages1 s2.0 S0104001421002724 MainjjmoralesbNo ratings yet

- DR Makam Sri Harsha ThesisDocument33 pagesDR Makam Sri Harsha ThesissumitNo ratings yet

- Prediction of Successful De-Cannulation of Tracheostomised Patients in Medical Intensive Care UnitsDocument10 pagesPrediction of Successful De-Cannulation of Tracheostomised Patients in Medical Intensive Care UnitsjesaloftNo ratings yet

- JURNALDocument6 pagesJURNALPutu erwanNo ratings yet

- Transtracheal LidocaineDocument4 pagesTranstracheal LidocaineaksinuNo ratings yet

- 5 - General Considerations of Anesthesia and Management of The Difficult AirwayDocument27 pages5 - General Considerations of Anesthesia and Management of The Difficult AirwayMauricio Ruiz MoralesNo ratings yet

- 2011 - Preoperative Endoscopic Airway Examination (PEAE) Provides Superior Airway Information and May Reduce The Use of Unnecessary Awake Ion - MylenaDocument6 pages2011 - Preoperative Endoscopic Airway Examination (PEAE) Provides Superior Airway Information and May Reduce The Use of Unnecessary Awake Ion - MylenaMirella Andraous100% (1)

- The Comparison Between LMA-S and ETT With Respect To Adequacy of Ventilation in Patients Undergoing Laparoscopic CholecDocument8 pagesThe Comparison Between LMA-S and ETT With Respect To Adequacy of Ventilation in Patients Undergoing Laparoscopic CholecGek DewiNo ratings yet

- Journal Homepage: - : IntroductionDocument7 pagesJournal Homepage: - : IntroductionIJAR JOURNALNo ratings yet

- Electromyography in Children's Laryngeal Mobility Disorders: A Proposed Grading SystemDocument6 pagesElectromyography in Children's Laryngeal Mobility Disorders: A Proposed Grading SystemQonita Aizati QomaruddinNo ratings yet

- Primary Management of PolytraumaFrom EverandPrimary Management of PolytraumaSuk-Kyung HongNo ratings yet

- Direct and Indirect Laryngoscopy: Equipment and Techniques: Stephen R Collins MDDocument15 pagesDirect and Indirect Laryngoscopy: Equipment and Techniques: Stephen R Collins MDnessiedgieNo ratings yet

- Paper Reintubación Variable Sexo y EdadDocument5 pagesPaper Reintubación Variable Sexo y EdadAres Kinesiology TapeNo ratings yet

- Extubacion en NeurocriticoDocument3 pagesExtubacion en NeurocriticoJuan Soto FarfanNo ratings yet

- Anesthetics and Anesthesiology: ClinmedDocument6 pagesAnesthetics and Anesthesiology: ClinmednadaNo ratings yet

- Journal PDFDocument6 pagesJournal PDFmuhammadfahmanNo ratings yet

- Endoscopic Evaluation of Adenoids: Reproducibility Analysis of Current MethodsDocument5 pagesEndoscopic Evaluation of Adenoids: Reproducibility Analysis of Current MethodsLucky PratamaNo ratings yet

- 3423 Emergency Tracheal Intubations at A University HospitalDocument7 pages3423 Emergency Tracheal Intubations at A University HospitalAnaNo ratings yet

- DR Koti Prem, PublicationDocument4 pagesDR Koti Prem, Publicationprem kotiNo ratings yet

- JAnaesthClinPharmacol371114-28986 000449Document5 pagesJAnaesthClinPharmacol371114-28986 000449Ferdy RahadiyanNo ratings yet

- Lower Eyelid Complications Associated With Transconjunctival Versus Subciliary Approaches To Orbital Floor FracturesDocument5 pagesLower Eyelid Complications Associated With Transconjunctival Versus Subciliary Approaches To Orbital Floor Fracturesstoia_sebiNo ratings yet

- Extubation in Neurocritical Care Patients: Lesson Learned: Understanding The DiseaseDocument3 pagesExtubation in Neurocritical Care Patients: Lesson Learned: Understanding The DiseaseIsabel VillalobosNo ratings yet

- Difficult Airway Management in The Intensive Care UnitDocument10 pagesDifficult Airway Management in The Intensive Care UnitcedivadeniaNo ratings yet

- Journal 5Document8 pagesJournal 5Nydia OngaliaNo ratings yet

- Predictionof Difficult AirwayDocument6 pagesPredictionof Difficult AirwayjemyNo ratings yet

- 2015 Article 815Document16 pages2015 Article 815silvia silalahiNo ratings yet

- Development of A Modified Swallowing Screening TooDocument7 pagesDevelopment of A Modified Swallowing Screening TooNADISH MANZOORNo ratings yet

- IndianJAnaesth572170-2964618 081406Document5 pagesIndianJAnaesth572170-2964618 081406Tanuja DasariNo ratings yet

- Assessment of Diaphragmatic Dysfunction in The Critically Ill PatientDocument10 pagesAssessment of Diaphragmatic Dysfunction in The Critically Ill PatientmrwgNo ratings yet

- Manejo de La Via Aerea Dificil 2021nejmDocument12 pagesManejo de La Via Aerea Dificil 2021nejmMartha Isabel BurgosNo ratings yet

- Production and Control of Coagulation Proteins For Factor X Activation in Human Endothelial Cells and FibroblastsDocument19 pagesProduction and Control of Coagulation Proteins For Factor X Activation in Human Endothelial Cells and FibroblastsEsteban TapiaNo ratings yet

- AHA Guideline STEMI 2013 PDFDocument64 pagesAHA Guideline STEMI 2013 PDFkiyoeugraNo ratings yet

- Contemporary Reviews in Cardiovascular Medicine: Inotropes and VasopressorsDocument10 pagesContemporary Reviews in Cardiovascular Medicine: Inotropes and VasopressorsMarlin Berliannanda TawayNo ratings yet

- Fimmu 13 921864Document17 pagesFimmu 13 921864Esteban TapiaNo ratings yet

- Balanced OcclusionDocument30 pagesBalanced OcclusionSweet SumanNo ratings yet

- Final - ECE - 140 - Booklet - Week 1 To 4Document59 pagesFinal - ECE - 140 - Booklet - Week 1 To 4Talwinder SinghNo ratings yet

- Jsa For RadiographyDocument3 pagesJsa For Radiographyjithin shankarNo ratings yet

- Gap Analysis, Action Taken & PrioritizationDocument18 pagesGap Analysis, Action Taken & PrioritizationZothankhumaNo ratings yet

- IEP Example ElementaryDocument13 pagesIEP Example ElementaryArthur DumanayosNo ratings yet

- Milk and Dairy Products EngDocument2 pagesMilk and Dairy Products EngSar OyaNo ratings yet

- Amity Park Walkthrough Version 0.7.3 2Document36 pagesAmity Park Walkthrough Version 0.7.3 2Sayak SahaNo ratings yet

- Pathways Rw3 2e U8 TestDocument12 pagesPathways Rw3 2e U8 TestdieuanhNo ratings yet

- Subtypes of Reading DisabilityDocument2 pagesSubtypes of Reading DisabilitySAIF K.QNo ratings yet

- Final SB BTDocument85 pagesFinal SB BTNgan Tran Nguyen ThuyNo ratings yet

- Result of Mizoram Civil Services (Combined Competitive) Main Examination, 2023Document5 pagesResult of Mizoram Civil Services (Combined Competitive) Main Examination, 2023llalhlantharaNo ratings yet

- Medication-Assisted Treatment (MAT) in The Emergency DepartmentDocument79 pagesMedication-Assisted Treatment (MAT) in The Emergency DepartmentPedro Carlos Martinez SuarezNo ratings yet

- Cryolite EngDocument11 pagesCryolite EngShiva RajNo ratings yet

- IELTS Reading - Target #1: Contributed by Rad Danesh Thursday, 10 May 2007 Last Updated Wednesday, 16 May 2007Document2 pagesIELTS Reading - Target #1: Contributed by Rad Danesh Thursday, 10 May 2007 Last Updated Wednesday, 16 May 2007Ibrahim FikryNo ratings yet

- 023 Procedure Equipment MaintenanceDocument6 pages023 Procedure Equipment MaintenanceHSE CERI100% (1)

- Authorized Test Center - Policies and Procedures PDFDocument365 pagesAuthorized Test Center - Policies and Procedures PDFNarra Venkata KrishnaNo ratings yet

- CHN SIMULATION DUTY Family N Community ProblemDocument1 pageCHN SIMULATION DUTY Family N Community Problemann camposNo ratings yet

- Rape Epidemic in India - Woman and Criminal Law Project ReportDocument12 pagesRape Epidemic in India - Woman and Criminal Law Project ReportNimisha SajekarNo ratings yet

- Col Zulfiquer Ahmed Amin: M Phil (HHM), MPH (HM), PGD (Health Economics), MBBS Armed Forces Medical Institute (AFMI)Document60 pagesCol Zulfiquer Ahmed Amin: M Phil (HHM), MPH (HM), PGD (Health Economics), MBBS Armed Forces Medical Institute (AFMI)Manav Suman SinghNo ratings yet

- Basic Sentence PatternsDocument54 pagesBasic Sentence PatternsAmalina ShadrinaNo ratings yet

- Konsumsi Fast Food Dan Kuantitas Tidur Sebagai Faktor Risiko Obesitas Siswa SMA Institut Indonesia SemarangDocument8 pagesKonsumsi Fast Food Dan Kuantitas Tidur Sebagai Faktor Risiko Obesitas Siswa SMA Institut Indonesia SemarangTEDY TEDYNo ratings yet

- Music Therapy For Preterm Infants and Their Parents: A Cluster-Randomized Controlled Trial ProtocolDocument24 pagesMusic Therapy For Preterm Infants and Their Parents: A Cluster-Randomized Controlled Trial ProtocolDaniele PendezaNo ratings yet

- Ce PDFDocument274 pagesCe PDFbhargavi deviNo ratings yet

- Clean Up and Flourish or Pile Up and PerishDocument30 pagesClean Up and Flourish or Pile Up and Perishnehabhilare100% (1)

- Jurnal InggrisDocument7 pagesJurnal InggrisKomariahNo ratings yet

- Inside Reading 1 Answer KeyDocument45 pagesInside Reading 1 Answer KeyKarie A. Houston67% (6)

- Grief Death and Dying HandoutDocument8 pagesGrief Death and Dying HandoutNikki AngNo ratings yet

- Risk Assessment and Method Statement Hollowcore Plank Installation With CraneDocument17 pagesRisk Assessment and Method Statement Hollowcore Plank Installation With CraneA123Y123No ratings yet

- Presentation On: "How Civility and Courtesy at The Workplace Impact The Productivity of An Organization."Document8 pagesPresentation On: "How Civility and Courtesy at The Workplace Impact The Productivity of An Organization."Mukul PandeyNo ratings yet

- Manila Emergency HotlinesDocument2 pagesManila Emergency HotlinesHarlem AgnoteNo ratings yet