Professional Documents

Culture Documents

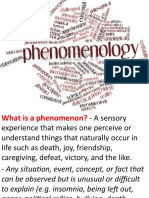

Phenomenology

Uploaded by

Zul FiqryOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Phenomenology

Uploaded by

Zul FiqryCopyright:

Available Formats

Methodologies: Phenomenology

PHENOMENOLOGY

In the literature, phenomenology is often contrasted with positivist inspired approaches in research.

Positivism is associated with the idea of their being objective, independent realities which we can

investigate using scientific methods. Phenomenology, on the other hand, is rooted in a philosophical

tradition in which it is argued meanings attached to our lived-experiences in the world are social

creations, and that perceptions of reality are social constructions. Viewed through this lens, the

social world exists only through the way it is experienced and interpreted by people, including

researchers. Furthermore, it opens up the possibility of people and groups of people seeing things

differently at different times in different circumstances, and a realisation that perceptions of reality

vary from situation to situation and culture to culture. In other words, we create personal, shared

and sometimes-competing perceptions of reality when interacting with one another in social

settings.

The notion, therefore, of phenomena being independent of human sense making, which we can

investigate using scientific methods, is challenged from a phenomenological viewpoint. Instead,

phenomenologists focus their attention on the perceptions of people concerning their experiences

and the meanings they ascribe to them, their attitudes and beliefs, and their feelings and emotions in

the light of those experiences.

As with any of the approaches used in qualitative research, there are many versions of

phenomenology, and arguments over what can, and cannot, be described as ‘true’ versions.

Commenting on these arguments, Denscombe (2010) identifies two basic traditions in

phenomenology: a European and a North American version.

The roots of the European version are to be found in the discipline of philosophy, and, in

particular, the work of Edmund Husserl. The ‘transcendental’ phenomenological approach

advocated by Husserl (1931) aims to uncover the underlying fundamental aspects of human

experience. Although different in a number of ways, the traditions of ‘existential phenomenology’

(Sartre, 1956) and ‘hermeneutic phenomenology’ (Heideger, 1962) share the same concern with

investigating the essence of human experience. Traditionally, this European approach is concerned

with fundamental philosophical questions about ‘being in the world’ and the meaning of everyday

life. It is for this reason that investigations into individual instances of lived experience are often

treated as the starting point for, or are part of, a wider investigation that is about getting a clearer

understanding of the essential qualities of particular experiences, which exist at a more general

level.

Tony Leach 2014

York St John University

Methodologies: Phenomenology

In contrast, the North American version of phenomenology is rooted in the disciplines of

sociology, psychology, education, business studies and health studies, and the tradition of social

phenomenology (Shultz, 1962, and 1967). Within this tradition, the focus of attention is on the

mental processes through which people make sense of their experiences. This approach is

concerned with the way we interpret and assign meanings to our experience rather than with

discovering the essence of human experience, as in the European tradition.

Unlike the European approach in phenomenological research, the practice of describing

individual experience and what it means to that person, rather than attempting to uncover the more

general essence of the experience, is accepted in North American phenomenology. According to

Denscombe (2010), in this version of phenomenology:

The experiences of the individual are taken as significant data in their own right, not something to be put

to one side in order to identify the universal essence of the phenomenon

The importance of the differences between the two approaches in phenomenological research

means the researcher should always be clear about the purpose and ultimate goal of the

investigation and the way in which the phenomenon of human experience will be described

WHAT PHENOMENOLOGIST’S DO

The researcher’s task is to try to penetrate, as deeply as possible, the participant’s internal,

personal world, and to try to understand their experiences as completely as possible (Hayes

2000:188). Understandably, this involves establishing a trusting relationship so that the participant

can feel comfortable when openly talking about their experiences and the meanings they attach to

them.

The preferred method when gathering data is to use tape-recorded, unstructured interviews

(Denscombe 2010). Typically, in phenomenological research, interviews take one hour or more to

complete, and this is necessary when the object is to explore matters in depth. This length of time

means there is usually sufficient opportunity for the interviewee to talk about issues which he, or

she, feels are important, and to provide an account of their experiences. In a lengthy interview, there

is also time for the researcher to check, when necessary, that he, or she, is hearing what the

interviewee actually wants to put across.

Once the data has been collected and transcribed, the analysis is conducted using a four-stage

process (Hayes 2000:189-194). The first step for the researcher is to reflect on and acknowledge

his, or her, prior knowledge, presuppositions and biases concerning the phenomenon, and to put

them to one side so that the analysis can uncover the meanings of the phenomenon from the

participant’s perspective. This process is called bracketing, and when working in this way, it is not

possible to be totally free of bias. However, consciously bringing to the surface and acknowledging

Tony Leach 2014

York St John University

Methodologies: Phenomenology

one’s prior knowledge and presuppositions does mean the researcher can take steps to control its

influence. According to Hayes (2000:189) bracketing frequently:

Leads to the focus of the research being reformulated, and it often helps the researcher to clarify their own

perceptions in a helpful way.

The second stage is when the researcher needs to decide which parts of the experience to

concentrate on, and which not to concentrate on, in the study. Other choices have to be made as

well during this stage. This involves decisions over which experiences should be the focus of

attention and included, and which methods to use when structuring the participant’s experiences and

recording them. This is why the earlier process of bracketing is so important. The insights and

understandings gained during that early stage are necessary when decisions are taken about the

continued direction and structure of the research. For example, becoming aware of the importance

of a particular part of the experience, as described by the participants, may result in the researcher

deciding to focus on that aspect of the participant’s experience.

The third stage of the analysis is about intuiting which involves the researcher deciding on and

adopting a particular mental approach when interacting with the data. Putting to one-side previous

assumptions and beliefs, the researcher sets out to explore the phenomenon in as open-minded a

way as possible. Commenting on this process, Hayes (2000:190) suggests it is about

acknowledging the importance of the participant’s subjective experience, which cannot be

understood from the outside, and, therefore, investigated using objective means:

The researcher needs to be able to feel what it would be like to be that person, or rather, to live in that

person’s world.

The phenomenologist’s stance is that these experiences can only be uncovered and appreciated as

far as possible when using a combination of intuition, empathy, imagination and open-mindedness

(Hayes 2000:190). The process of reading and re-reading the interview transcripts is an iterative

one. Over time, the aim is to develop a sense of understanding of the person’s point of view. In

terms of organisation, the process of coding and analysing the data and uncovering themes can be

similar to the one used in grounded theory analysis (see the course notes on grounded theory).

In the final stage of the analysis, and working in a way similar to the one used by an

ethnographer, the phenomenologist uses the participant’s descriptions of the experiences in such a

way that they are drawn together to make intuitive sense to other people. This is a way of testing

whether the researcher’s descriptive insights concerning the meanings people ascribe to their

experiences are appropriate or not. Another test is to check with the respondents to see whether or

not they feel the account of their experiences is valid or not.

In phenomenological research there are internal and external tests of validity. Internal validity

involves comparing the researcher’s account of the participant’s experiences with what the

participants have said during the interviews to see whether they match, or not. External validity is

Tony Leach 2014

York St John University

Methodologies: Phenomenology

achieved when the research participant considers whether or not the researcher’s final account of

their lived-experiences is a true reflection of how they see things. Obtaining the participant’s

subjective agreement concerning the validity of the account is entirely consistent with the principles

of phenomenological research.

Tony Leach 2014

York St John University

Methodologies: Phenomenology

EXAMPLES OF RESEARCH USING A PHENOMENOLOGICAL APPROACH

Examples of experiences, which can be explored using a phenomenological approach, are

investigating the experience, the essence of:

1. being bullied, focusing on the essential features of that experience;

2. a learning disability;

3. terminal illness;

4. anorexia;

5. exam stress;

6. finding a job and starting a career after graduation.

ADVANTAGES AND DISADVANTAGES OF PHENOMENOLOGY

Denscombe (2008:85-86) lists the following advantages and disadvantages when using this

approach:

ADVANTAGES

It offers the prospect of obtaining authentic, in-depth accounts of complex phenomena as

experienced by individuals and group of people;

It is a humanistic style of research that pays attention to the lived-experiences of people in the

everyday world;

It is suited to small-scale research because it is reliant on in-depth interviews which can be

undertaken in specific localities; such as, hospitals, schools or businesses, and when funding is

short and the researcher is the main resource;

The resulting descriptions of people’s experiences are potentially of interest to a wider range of

readers.

DISADVANTAGES

It is claimed the approach is subjective and lacks scientific rigor. Since the approach is, by

definition, a way of delivering subjective accounts of people’s lived-experiences, there are no

objective measures of reliability or representativeness for the researcher to use when working in

this way;

Critics claim is it is primarily concerned with providing descriptions rather than explanations.;

Tony Leach 2014

York St John University

Methodologies: Phenomenology

Because phenomenological research tends to be concerned with small rather than large number

of instances, generalisations based on the findings cannot be drawn;

Critics claim the approach causes researchers to focus on mundane, trivial and relatively

unimportant subjective issues rather than the big issues of the day;

Critics argue that it is not possible for us to suspend entirely our presuppositions when

considering the views and opinions of other people.

REPORTING APPROACHES: GENERAL STRUCTURE OF STUDY

Purpose – describing the “essence” of the experience

Introduction (problem, questions)

Research procedures (a phenomenology and philosophical assumptions, data collection,

analysis, outcomes)

Significant statements

Meaning of statements

Themes of meanings

Exhaustive description of phenomenon

REFERENCES

Denscombe, M. (2010)) The Good Research Guide for small-scale social research projects, 3rd edition.

Maidenhead: OUP/McGraw-Hill Education.

Hayes, N. (2000) Doing Psychological Research: Gathering and analysing data. Buckingham: Open

University Press.

Tony Leach 2014

York St John University

You might also like

- Method or Madness: Transcendental Phenomenology As Knowledge CreatorDocument41 pagesMethod or Madness: Transcendental Phenomenology As Knowledge CreatorPsychologyEnergyNo ratings yet

- Phenomenological Research and Ethnographic ResearchDocument4 pagesPhenomenological Research and Ethnographic ResearchLinn LattNo ratings yet

- Phenomenological Research PDFDocument5 pagesPhenomenological Research PDFrebellin100% (1)

- Unit 4 Qualitative ResearchDocument36 pagesUnit 4 Qualitative Researchbemina jaNo ratings yet

- PHENOMENOLOGICAL-STUDY ResearchDocument13 pagesPHENOMENOLOGICAL-STUDY ResearchLoren KayeNo ratings yet

- Qulitative DesignDocument10 pagesQulitative DesignAmanda ScarletNo ratings yet

- PHENOMENOLOGYDocument17 pagesPHENOMENOLOGYSheila Mae LiraNo ratings yet

- Byrne - Understanding Life Experiences... - 1Document3 pagesByrne - Understanding Life Experiences... - 1Ericson MitraNo ratings yet

- FenomenologiDocument15 pagesFenomenologiyola amanthaNo ratings yet

- The Phenomenological InterviewDocument7 pagesThe Phenomenological InterviewJavier González PáezNo ratings yet

- A Synthesis of Ethnographic ResearchDocument13 pagesA Synthesis of Ethnographic ResearchRhoderick RiveraNo ratings yet

- Research and MethodologiesDocument3 pagesResearch and MethodologiesMishe MeeNo ratings yet

- Unit 1Document22 pagesUnit 1Archana PokharelNo ratings yet

- Philosophy Activity Sheet 2Document16 pagesPhilosophy Activity Sheet 2Kyle Torres AnchetaNo ratings yet

- Brady Ways of Knowing Paper Bds 1Document12 pagesBrady Ways of Knowing Paper Bds 1api-456699912No ratings yet

- The Positivism ParadigmDocument10 pagesThe Positivism Paradigmhadjira chigaraNo ratings yet

- Qualitative Research Methodology: PhenomenologyDocument23 pagesQualitative Research Methodology: PhenomenologyGANo ratings yet

- Worksheet 2Document4 pagesWorksheet 2Martina Rial BisNo ratings yet

- Week3 - Nursing ResearchDocument34 pagesWeek3 - Nursing Researchnokhochi55No ratings yet

- Origin of Research Based On PhilosophyDocument6 pagesOrigin of Research Based On Philosophysudeshna86100% (1)

- Approaches of Qualitative ResearchDocument8 pagesApproaches of Qualitative ResearchDr. Nisanth.P.M100% (1)

- Comparing and Contrasting The Interpretive and Social Constructivist Paradigms in Terms of OntologyDocument10 pagesComparing and Contrasting The Interpretive and Social Constructivist Paradigms in Terms of OntologyMrCalvinCalvinCalvin100% (1)

- Filed Methods in Psych, ReviewerDocument32 pagesFiled Methods in Psych, ReviewerKrisha Avorque100% (1)

- Research ParadigmsDocument4 pagesResearch ParadigmsMa rouaNo ratings yet

- Lesson Plan HandwashingDocument4 pagesLesson Plan HandwashingDan Lhery Susano GregoriousNo ratings yet

- CNUR850, Module 5 - Learning ObjectivesDocument5 pagesCNUR850, Module 5 - Learning ObjectiveskNo ratings yet

- Critical Analysis of Different Paradigms in The Field of Social ResearchDocument15 pagesCritical Analysis of Different Paradigms in The Field of Social Researchscribd1No ratings yet

- PhenomenologyDocument7 pagesPhenomenologyJES LOVE TORRESNo ratings yet

- Organic Inquiry Toward Research in Partnership With SpiritDocument24 pagesOrganic Inquiry Toward Research in Partnership With SpiritMoonRayPearlNo ratings yet

- Interpretivism and PostivismDocument3 pagesInterpretivism and PostivismRajeev AppuNo ratings yet

- Study Guide 11 - Research StrategiesDocument8 pagesStudy Guide 11 - Research Strategiestheresa balaticoNo ratings yet

- 06-Abid - Q. ResearchDocument29 pages06-Abid - Q. ResearchAbid AliNo ratings yet

- Phenomenology: A Philosophy and Method of InquiryDocument8 pagesPhenomenology: A Philosophy and Method of InquirygoonmikeNo ratings yet

- A Synthesis of Ethnographic Research By: Michael Genzuk, PH.DDocument11 pagesA Synthesis of Ethnographic Research By: Michael Genzuk, PH.DangelaborbaNo ratings yet

- A Synthesis of Ethnographic ResearchDocument21 pagesA Synthesis of Ethnographic ResearchtshanexyNo ratings yet

- Arthur FrederickDocument5 pagesArthur FrederickFrederick ArthurNo ratings yet

- Des vs. Interpretative PhenoDocument28 pagesDes vs. Interpretative PhenoMarwin ObmergaNo ratings yet

- Types of Qualitative Research - SubmitDocument25 pagesTypes of Qualitative Research - SubmitZandi Er NomoNo ratings yet

- Module 2Document13 pagesModule 2Johan S BenNo ratings yet

- Qualitative ResearchDocument5 pagesQualitative Researchamir sohailNo ratings yet

- Advanced Qualitative Research TechniquesDocument19 pagesAdvanced Qualitative Research Techniqueswaqas farooqNo ratings yet

- Advanced Research Methodology 2Document18 pagesAdvanced Research Methodology 2Raquibul Hassan100% (1)

- Task 1 Research Approaches and PhilosophiesDocument21 pagesTask 1 Research Approaches and Philosophiesyogo camlusNo ratings yet

- EmpiricismDocument8 pagesEmpiricismjuliusondieki34No ratings yet

- Presented by Natasha Arthurton and Marni Gavritsas Long Island University, C.W. PostDocument18 pagesPresented by Natasha Arthurton and Marni Gavritsas Long Island University, C.W. PostMaria Alexandra Joy BonnevieNo ratings yet

- Critical Theory ParadigmsDocument8 pagesCritical Theory ParadigmsShaziaNo ratings yet

- Research PhilosophyDocument12 pagesResearch PhilosophyJarhan Azeem92% (12)

- Group 2 Phenomenological StudyDocument25 pagesGroup 2 Phenomenological StudyNecheal BaayNo ratings yet

- Women in Bangladesh Civil Service: Mystique of Their DevelopmentDocument13 pagesWomen in Bangladesh Civil Service: Mystique of Their DevelopmentHasina Akter EvaNo ratings yet

- Notes On PhenomenologyDocument5 pagesNotes On PhenomenologyDon Chiaw ManongdoNo ratings yet

- 5 Types of Qualitative ResearchDocument7 pages5 Types of Qualitative ResearchJennifer Gonzales-CabanillaNo ratings yet

- 5 Types of Qualitative ResearchDocument7 pages5 Types of Qualitative ResearchJennifer Gonzales-CabanillaNo ratings yet

- A Guide To OntologyDocument4 pagesA Guide To OntologyihsanNo ratings yet

- Arp 01Document8 pagesArp 01Brandy M. TwilleyNo ratings yet

- Basic Interpretive Design-1Document10 pagesBasic Interpretive Design-1Gitaayu ardiawantanaputriNo ratings yet

- Ecological Engagement: Urie Bronfenbrenner’s Method to Study Human DevelopmentFrom EverandEcological Engagement: Urie Bronfenbrenner’s Method to Study Human DevelopmentSilvia Helena KollerNo ratings yet

- Projective Psychology - Clinical Approaches To The Total PersonalityFrom EverandProjective Psychology - Clinical Approaches To The Total PersonalityNo ratings yet

- Meaningful Work: Viktor Frankl’s Legacy for the 21st CenturyFrom EverandMeaningful Work: Viktor Frankl’s Legacy for the 21st CenturyNo ratings yet

- HR Digital Transformation Guide AIHRDocument49 pagesHR Digital Transformation Guide AIHRSandeepGambhir100% (6)

- Fs2 Episode 3Document4 pagesFs2 Episode 3Delos Santos Gleycelyn L.No ratings yet

- Meeting 4-Phrasal VerbDocument8 pagesMeeting 4-Phrasal VerbLuthfi DioNo ratings yet

- Lucid Source InternshipDocument4 pagesLucid Source InternshipBlank UserNo ratings yet

- Plastic Tape Casting Lesson PlanDocument2 pagesPlastic Tape Casting Lesson Planeyvaught0% (1)

- Martin Krampen - Children's Drawings - Iconic Coding of The EnvironmentDocument239 pagesMartin Krampen - Children's Drawings - Iconic Coding of The Environmentziropadja100% (1)

- 9 Ways To Stop Absorbing Other People's Negative EmotionsDocument388 pages9 Ways To Stop Absorbing Other People's Negative EmotionsbabanpNo ratings yet

- The Effectiveness of Enrichment Activities Program Based On Educational Techniques On The Quality of Mathematics Outcomes For Third Grade Primary Students in JordanDocument14 pagesThe Effectiveness of Enrichment Activities Program Based On Educational Techniques On The Quality of Mathematics Outcomes For Third Grade Primary Students in JordanDINO DIZONNo ratings yet

- 76 Bulgarian PhrasesDocument7 pages76 Bulgarian PhrasesVIDEOONLINETRANSLATION translatorNo ratings yet

- DLL rwW2Document2 pagesDLL rwW2Nors CruzNo ratings yet

- Employee Evaluation: Why Employers Use Employee EvaluationsDocument12 pagesEmployee Evaluation: Why Employers Use Employee EvaluationsnathiyaNo ratings yet

- Esp Test Grade 7Document2 pagesEsp Test Grade 7DanielLarryAquino100% (1)

- Personality Types: By: Abdulrahman B. Amlih, RNDocument13 pagesPersonality Types: By: Abdulrahman B. Amlih, RNAbuMaryamBurahimAmlihNo ratings yet

- EF3e Beg Filetest 11 Answerkey 000Document4 pagesEF3e Beg Filetest 11 Answerkey 000Williams M. Gamarra ArateaNo ratings yet

- Participant Observation and NonDocument4 pagesParticipant Observation and NonWondwosen TilahunNo ratings yet

- WWLP AssignmentDocument27 pagesWWLP AssignmentnileshdilushanNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1: Introduction To Human Resource ManagementDocument17 pagesChapter 1: Introduction To Human Resource ManagementLâm Trần TrúcNo ratings yet

- Unit 1 (Purposive Communication)Document13 pagesUnit 1 (Purposive Communication)Christine100% (2)

- Standard-Based Curriculum Report HandoutDocument5 pagesStandard-Based Curriculum Report HandoutMimi LabindaoNo ratings yet

- One More Example : Why "Get"?Document6 pagesOne More Example : Why "Get"?Marina100% (1)

- Personalized Customer Churn Analysis With LSTMDocument5 pagesPersonalized Customer Churn Analysis With LSTMUmitNo ratings yet

- Material 1 and 2Document14 pagesMaterial 1 and 2citra kusuma dewiNo ratings yet

- Development of Student's Academic Performance Prediction ModelDocument16 pagesDevelopment of Student's Academic Performance Prediction ModelopepolawalNo ratings yet

- Learning Theory and Lesson PlanningDocument23 pagesLearning Theory and Lesson PlanningMcCormick_Daniel93% (14)

- Epistemology and Spiritual AuthorityDocument219 pagesEpistemology and Spiritual Authoritychetanpandey100% (1)

- Personalized Learning PlanDocument1 pagePersonalized Learning PlanSheena Claire dela PeñaNo ratings yet

- Emotional IntelligenceDocument11 pagesEmotional IntelligenceAjay MishraNo ratings yet

- A Rough Guide To IciBemba PDFDocument19 pagesA Rough Guide To IciBemba PDFjezNo ratings yet

- 4.1. Materi Leadership Journey - Pemimpin Membentuk Budaya - HLP#2Document29 pages4.1. Materi Leadership Journey - Pemimpin Membentuk Budaya - HLP#2emyNo ratings yet

- Machine Learning For Efficient Assessment and Prediction of Human (1127) PDFDocument6 pagesMachine Learning For Efficient Assessment and Prediction of Human (1127) PDFSai PrakashNo ratings yet