Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Addiction - Wikipedia

Addiction - Wikipedia

Uploaded by

Badhon Chandra SarkarOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Addiction - Wikipedia

Addiction - Wikipedia

Uploaded by

Badhon Chandra SarkarCopyright:

Available Formats

Search Wikipedia Search Create account Log in

Wiki Loves Monuments: Photograph a monument, help Wikipedia and win!

Learn more

Addiction 92 languages

Contents [hide] Article Talk Read Edit View history Tools

(Top) From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Definitions

"Addictive" redirects here. For other uses, see Addiction (disambiguation) and Addictive (disambiguation).

Substance addiction

Not to be confused with Psychological dependence.

Behavioral addiction

Addiction is generally a neuropsychological disorder defining pervasive and intense urge to engage

Addiction

Signs and symptoms in maladaptive behaviors providing immediate sensory rewards (e.g. consuming drugs, excessively

Other Addictive behaviour (e.g. substance-use

Screening and assessment gambling), despite their harmful consequences. Dependence is generally an addiction that can names addiction, sexual addiction), dependence,

involve withdrawal issues. Addictive disorder is a category of mental disorders defining important addictive disorder, addiction disorder (e.g.

Causes

intensities of addictions or dependences, which induce functional disabilities. There are no agreed severe substance-use disorder, gambling

Risk factors definitions on these terms – see section on 'definitions'. disorder)

Mechanisms Repetitive drug use alters brain function in ways that perpetuate craving, and weakens (but does not

Diagnosis completely negate) self-control.[1][2] This phenomenon – drugs reshaping brain function – has led to

Prevention an understanding of addiction as a brain disorder with a complex variety of psychosocial as well as

neurobiological (and thus involuntary)[a] factors that are implicated in addiction's development.[3][4][5]

Treatment and management

Classic signs of addiction include compulsive engagement in rewarding stimuli, preoccupation with

Epidemiology

substances or behavior, and continued use despite negative consequences. Habits and patterns

Addiction and the humanities associated with addiction are typically characterized by immediate gratification (short-term

Social scientific models reward),[6][7] coupled with delayed deleterious effects (long-term costs).[4][8] Brain positron emission tomography images that

compare brain metabolism in a healthy individual and

See also Examples of drug (or more generally, substance) addictions include alcoholism, marijuana addiction, an individual with a cocaine addiction

amphetamine addiction, cocaine addiction, nicotine addiction, opioid addiction, and eating or food Specialty Psychiatry, clinical psychology, toxicology,

Endnotes

addiction. Alternatively, behavioral addictions may include gambling addiction, internet addiction, addiction medicine

Notes

social media addiction, video game addiction and sexual addiction. The DSM-5 and ICD-10 only

References recognise gambling addictions as behavioural addictions, but the ICD-11 also recognises gaming addictions.[9]

Further reading

External links

Definitions [ edit ]

Addictions or addictive behaviours, are polysemes defining both a category of mental disorders, neuropsychological symptoms, or merely

maladaptive/harmful habits and lifestyles.[10] A common use of addictions in medicine, is as neuropsychological symptoms defining pervasive/excessive

and intense urges to engage in a category of behavioural compulsions or impulses towards sensory rewards (e.g. alcohol, betel quid, drugs, sex, gambling,

video gaming).[11][12][13][14][15] Addictive disorders or addiction disorders, are mental disorders involving high intensities of addictions (as

neuropsychological symptoms) that induce functional disabilities (i.e. limit subjects' social/family and occupational activities), and whose the two addiction

categories are substance-use addictions and behavioural addictions.[16][10][14][15]

However, there is no agreement on the exact definition of addictions in medicine. Indeed, Volkow et al. (2016) report that the DSM-5 defines addictions as

the most severe degree of the addictive disorders due to pervasive/excessive substance-use or behavioural compulsions/impulses.[17] It is a definition that

many scientific papers and reports use.[18][19][20]

Dependences is also a polyseme defining either neuropsychological symptoms or mental disorders. In the DSM-5, dependences differ from addictions and

can even normally happen without addictions;[21] besides, substance-use dependences are severe stages of substance-use addictions (i.e. mental

disorders) involving withdrawal issues.[22] In the ICD-11, substance-use dependences is a synonym of substance-use addictions (i.e. neuropsychological

symptoms) that can but not necessarily involve withdrawal issues.[23]

Substance addiction [ edit ]

Main article: Substance use disorder

Further information: Substance abuse and Substance-related disorder

Drug addiction [ edit ] Addiction and dependence glossary[3][24][25]

Drug addiction, which belongs to the class of substance-related disorders, is a chronic addiction – a biopsychosocial disorder characterized by persistent

use of drugs (including alcohol) despite substantial harm and adverse

and relapsing brain disorder that features drug seeking and drug abuse, despite their

consequences

harmful effects.[26] This form of addiction changes brain circuitry such that the brain's

addictive drug – psychoactive substances that with repeated use

reward system is compromised,[2] causing functional consequences for stress are associated with significantly higher rates of substance use

management and self-control.[26] Damage to the functions of the organs involved can disorders, due in large part to the drug's effect on brain reward

persist throughout a lifetime and cause death if untreated.[26] Substances involved with systems

dependence – an adaptive state associated with a withdrawal

drug addiction include alcohol, nicotine, marijuana, opioids, cocaine, amphetamines,

syndrome upon cessation of repeated exposure to a stimulus (e.g.,

and even foods with high fat and sugar content.[27][28] Addictions can begin

drug intake)

experimentally in social contexts[29] and can arise from the use of prescribed drug sensitization or reverse tolerance – the escalating effect of a

medications or a variety of other measures.[30] drug resulting from repeated administration at a given dose

drug withdrawal – symptoms that occur upon cessation of repeated

Drug addiction has been shown to work in phenomenological, conditioning (operant and

drug use

classical), cognitive models, and the cue reactivity model. However, no one model physical dependence – dependence that involves persistent

completely illustrates substance abuse.[31] physical–somatic withdrawal symptoms (e.g., fatigue and delirium

tremens)

Risk factors for addiction include:

psychological dependence – dependence socially seen as being

Aggressive behavior (particularly in childhood) extremely mild compared to physical dependence (e.g., With enough

Availability of substance[29] willpower it could be overcome)

reinforcing stimuli – stimuli that increase the probability of repeating

Community economic status

behaviors paired with them

Experimentation[29] rewarding stimuli – stimuli that the brain interprets as intrinsically

Epigenetics positive and desirable or as something to approach

Impulsivity (attentional, motor, or non-planning)[32] sensitization – an amplified response to a stimulus resulting from

repeated exposure to it

Lack of parental supervision[29]

substance use disorder – a condition in which the use of

Lack of peer refusal skills[29] substances leads to clinically and functionally significant impairment

Mental disorders[29] or distress

Method substance is taken[26] tolerance – the diminishing effect of a drug resulting from repeated

administration at a given dose

Usage of substance in youth[29]

· ·

Food addiction [ edit ]

Main article: Food addiction

The diagnostic criteria for food or eating addiction has not been categorized or defined in references such as the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of

Mental Disorders (DSM or DSM-5) and is based on subjective experiences similar to substance use disorders.[33][32] Food addiction may be found in those

with eating disorders, though not all people with eating disorders have food addiction and not all of those with food addiction have a diagnosed eating

disorder.[33] Long-term frequent and excessive consumption of foods high fat, salt, or sugar, such as chocolate, can produce an addiction[34][35] similar to

drugs since they trigger the brain's reward system, such that the individual may desire the same foods to an increasing degree over time.[36][33][32] The

signals sent when consuming highly palatable foods have the ability to counteract the body's signals for fullness and persistent cravings will result.[36]

Those who show signs of food addiction may develop food tolerances, in which they eat more, despite the food becoming less satisfactory.[36]

Chocolate's sweet flavor and pharmacological ingredients are known to create a strong craving or feel 'addictive' by the consumer.[37] A person who has a

strong liking for chocolate may refer to themselves as a chocoholic.

Risk factors for developing food addiction include excessive overeating and impulsivity.[32]

The Yale Food Addiction Scale (YFAS), version 2.0, is the current standard measure for assessing whether an individual exhibits signs and symptoms of

food addiction.[38][33][32] It was developed in 2009 at Yale University on the hypothesis that foods high in fat, sugar, and salt have addictive-like effects

which contribute to problematic eating habits.[39][36] The YFAS is designed to address 11 substance-related and addictive disorders (SRADs) using a 25-

item self-report questionnaire, based on the diagnostic criteria for SRADs as per DSM-5.[40][33] A potential food addiction diagnosis is predicted by the

presence of at least two out of 11 SRADs and a significant impairment to daily activities.[41]

The Barratt Impulsiveness Scale, specifically the BIS-11 scale, and the UPPS-P Impulsive Behavior subscales of Negative Urgency and Lack of

Perseverance have been shown to have relation to food addiction.[32]

Behavioral addiction [ edit ]

Main article: Behavioral addiction

The term behavioral addiction refers to a compulsion to engage in a natural reward – which is a behavior that is inherently rewarding (i.e., desirable or

appealing) – despite adverse consequences.[7][34][35] Preclinical evidence has demonstrated that marked increases in the expression of ΔFosB through

repetitive and excessive exposure to a natural reward induces the same behavioral effects and neuroplasticity as occurs in a drug addiction.[34][42][43][44]

Addiction can exist in the absence of psychotropic drugs, which was popularized by Peele.[45] These are termed behavioral addictions. Such addictions

may be passive or active, but they commonly contain reinforcing features, which are found in most addictions.[45] Sexual behavior, eating, gambling,

playing video games, and shopping are all associated with compulsive behaviors in humans and have been shown to activate the mesolimbic pathway and

other parts of the reward system.[34] Based on this evidence, sexual addiction, gambling addiction, video game addiction, and shopping addiction are

classified accordingly.[34][46]

Sexual [ edit ]

Main article: Sexual addiction

Sexual addiction involves an engagement in excessive, compulsive, or otherwise problematic sexual behavior that persists despite negative physiological,

psychological, social, and occupational consequences.[47] Sexual addiction may be referred to as hypersexuality or compulsive sexual behavior

disorder.[47] The DSM-5 does recognize sexual addiction as a clinical diagnosis.[48] Hypersexuality disorder and internet addiction disorder were among

proposed addictions to the DSM-5, but were later rejected due to the insufficient evidence available in support of the existence of these disorders as

discrete mental health conditions.[49] Reviews of both clinical research in humans and preclinical studies involving ΔFosB have identified compulsive

sexual activity – specifically, any form of sexual intercourse – as an addiction (i.e., sexual addiction).[34][42] Reward cross-sensitization between

amphetamine and sexual activity, meaning that exposure to one increases the desire for both, has been shown to occur as a dopamine dysregulation

syndrome.[34][42][43][44] ΔFosB expression is required for this cross-sensitization effect, which intensifies with the level of ΔFosB expression.[34][43][44]

Gambling [ edit ]

Main articles: Gambling and Problem gambling

Gambling provides a natural reward that is associated with compulsive behavior.[34] Functional neuroimaging evidence shows that gambling activates the

reward system and the mesolimbic pathway in particular.[34][46] It is known that dopamine is involved in learning, motivation, as well as the reward

system.[50][2] The exact role of dopamine in gambling addiction has been debated.[50] Suggested roles for D2, D3, and D4 dopamine receptors, as well as

D3 receptors in the substantia nigra have been found in rat and human models, showing a correlation with the severity of the gambling behavior.[50] This in

turn was linked with greater dopamine release in the dorsal striatum.[50]

Gambling addictions are linked with comorbidities such as mental health disorders, substance abuse, alcohol use disorder, and personality disorders.[51]

Risk factors for gambling addictions include:

Antisocial behavior,

Impulsive personality,[32]

Male,

Sensation seeking,[52]

Substance use, and

Young age.

Gambling addiction has been associated with some personality traits, including: harm avoidance, low self direction, decision making and planning

insufficiencies, impulsivity, as well as sensation seeking individuals.[52] Although some personality traits can be linked with gambling addiction, there is no

general description of individuals addicted to gambling.[52]

Internet [ edit ]

Main article: Internet addiction disorder

Internet addiction does not have any standardized definition, yet there is widespread agreement that this problem exists.[53] Debate over the classification

of problematic internet use considers whether it should be thought of as a behavioral addiction, an impulse control disorder, or an obsessive-compulsive

disorder.[54][55] Others argue that internet addiction should be considered a symptom of an underlying mental health condition and not a disorder in

itself.[56] Internet addiction has been described as "a psychological dependence on the Internet, regardless of the type of activity once logged on."[53]

Problematic internet use may include a preoccupation with the internet and/or digital media, excessive time spent using the internet despite resultant

distress in the individual, increase in the amount of internet use required to achieve the same desired emotional response, loss of control over one's

internet use habits, withdrawal symptoms, and continued problematic internet use despite negative consequences to one's work, social, academic, or

personal life.[57]

Studies conducted in India, United States, Asia, and Europe have identified Internet addiction prevalence rates ranging in value from 1% to 19%, with the

adolescent population having high rates compared to other age groups.[58][59] Prevalence rates have been difficult to establish due to a lack of universally

accepted diagnostic criteria, a lack of diagnostic instruments demonstrating cross-cultural validity and reliability, and existing controversy surrounding the

validity of labeling problematic internet use as an addictive disorder.[60][59] The most common scale used to measure addiction is the Internet Addiction Test

developed by Kimberly Young.[59]

People with internet addiction are likely to have a comorbid psychiatric disorder. Comorbid diagnoses identified alongside internet addiction include

affective mood disorders, anxiety disorders, substance use disorders, and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder.[60]

Video games [ edit ]

Main article: Video game addiction

Video game addiction is characterized by the World Health Organization (WHO) as excessive gaming behavior, potentially prioritized over other interests,

despite the negative consequences that may arise, for a period of at least 12 months.[61] In May 2019, the WHO introduced gaming disorder in the 11th

edition of the International Classification of Diseases.[62] Video game addiction has been shown to be more prevalent in males than females, higher by 2.9

times.[63] It has been suggested that people of younger ages are more prone to become addicted to video games.[63] This may be due to video games

being relatively new, hence the higher prevalence in younger groups.[64] People with certain personalities may be more susceptible to gaming

addictions.[63][65]

Risk factors for video game addiction include:

Male,

Psychopathologies (e.g. ADHD or MDD), and

Social anxiety.[66]

Shopping [ edit ]

Main articles: Shopping addiction and Compulsive buying disorder

Shopping addiction, or compulsive buying disorder (CBD), is the excessive urge to shop or spend, potentially resulting in unwanted consequences.[67]

These consequences can have serious impacts, such as increased consumer debt, negatively affected relationships, increased risk of illegal behavior, and

suicide attempts.[67] Shopping addiction occurs worldwide and has shown a 5.8% prevalence in the United States.[68] Similar to other behavioral

addictions, CBD can be linked to mood disorders, substance use disorders, eating disorders, and other disorders involving a lack of control.[68]

Signs and symptoms [ edit ]

Signs and symptoms of addiction can vary depending on the type of addiction. Symptoms of drug addictions may include:

Continuation of drug use despite the knowledge of consequences[33]

Disregarding financial status when it comes to drug purchases

Ensuring a stable supply of the drug

Experiencing withdrawal symptoms when stopping the drug[69][33]

Needing more of the drug over time to achieve similar effects[33]

Social and work life impacted due to drug use[33]

Unsuccessful attempts to stop drug use[33]

Urge to use drug regularly

Signs and symptoms of addiction may include:

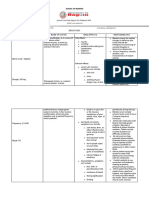

Behavioral Changes Physical Changes Social Changes

Angry and irritable Abnormal pupil size Changes in hobbies

Changes to eating or sleeping habits Bloodshot eyes Changes to financial status (unexplained need for

Changes to personality and attitude Body odor money)

Decreased attendance and performance in workplace or Impaired motor Legal problems related to substance abuse

school setting[33] coordination[70] Sudden changes in friends and associates

Fearful, paranoid and anxious without probable cause[70] Periodic tremors Use of substance despite consequences to personal

Frequently engaging in conflicts (fights, illegal activity) Poor physical appearance relationships[70]

Frequent or sudden changes in mood and temperament Slurred speech

Hiding or in denial of certain behaviors Sudden changes in weight

Lack of motivation

Periodic hyperactivity

Using substances in inappropriate settings

Screening and assessment [ edit ]

Addictions Neuroclinical Assessment [ edit ]

The Addictions Neuroclinical Assessment is used to diagnose addiction disorders. This tool measures three different domains: executive function, incentive

salience, and negative emotionality.[71][72] Executive functioning consists of processes that would be disrupted in addiction.[72] In the context of addiction,

incentive salience determines how one perceives the addictive substance.[72] Increased negative emotional responses have been found with individuals

with addictions.[72]

Tobacco, Alcohol, Prescription Medication, and Other Substance Use (TAPS) [ edit ]

This is a screening and assessment tool in one, assessing commonly used substances. This tool allows for a simple diagnosis, eliminating the need for

several screening and assessment tools, as it includes both TAPS-1 and TAPS-2, screening and assessment tools respectively. The screening component

asks about the frequency of use of the specific substance (tobacco, alcohol, prescription medication, and other).[73] If an individual screens positive, the

second component will begin. This dictates the risk level of the substance.[73]

CRAFFT [ edit ]

The CRAFFT (Car-Relax-Alone-Forget-Family and Friends-Trouble) is a screening tool that is used in medical centers. The CRAFFT is in version 2.1 and

has a version for nicotine and tobacco use called the CRAFFT 2.1+N.[74] This tool is used to identify substance use, substance related driving risk, and

addictions among adolescents. This tool uses a set of questions for different scenarios.[75] In the case of a specific combination of answers, different

question sets can be used to yield a more accurate answer. After the questions, the DSM-5 criteria are used to identify the likelihood of the person having

substance use disorder.[75] After these tests are done, the clinician is to give the "5 RS" of brief counseling.

The five Rs of brief counseling includes:

1. REVIEW screening results

2. RECOMMEND to not use

3. RIDING/DRIVING risk counseling

4. RESPONSE: elicit self-motivational statements

5. REINFORCE self-efficacy[75]

Drug Abuse Screening Test (DAST-10) [ edit ]

The Drug Abuse Screening Test (DAST) is a self-reporting tool that measures problematic substance use.[76] Responses to this test are recorded as yes or

no answers, and scored as a number between zero and 28. Drug abuse or dependence, are indicated by a cut off score of 6.[76] Three versions of this

screening tool are in use: DAST-28, DAST-20, and DAST-10. Each of these instruments are copyrighted by Dr. Harvey A. Skinner.[76]

Alcohol, Smoking, and Substance Involvement Test (ASSIST) [ edit ]

The Alcohol, Smoking, and Substance Involvement Test (ASSIST) is an interview-based questionnaire consisting of eight questions developed by the

WHO.[77] The questions ask about lifetime use; frequency of use; urge to use; frequency of health, financial, social, or legal problems related to use; failure

to perform duties; if anyone has raised concerns over use; attempts to limit or moderate use; and use by injection.[78]

Causes [ edit ]

Personality theories [ edit ]

Main article: Personality theories of addiction

Personality theories of addiction are psychological models that associate personality traits or modes of thinking (i.e., affective states) with an individual's

proclivity for developing an addiction. Data analysis demonstrates that psychological profiles of drug users and non-users have significant differences and

the psychological predisposition to using different drugs may be different.[79] Models of addiction risk that have been proposed in psychology literature

include: an affect dysregulation model of positive and negative psychological affects, the reinforcement sensitivity theory of impulsiveness and behavioral

inhibition, and an impulsivity model of reward sensitization and impulsiveness.[80][81][82][83][84]

Neuropsychology [ edit ]

The transtheoretical model of change (TTM) can point to how someone may be conceptualizing their addiction and the thoughts around it, including not

being aware of their addiction.[85]

Cognitive control and stimulus control, which is associated with operant and classical conditioning, represent opposite processes (i.e., internal vs external

or environmental, respectively) that compete over the control of an individual's elicited behaviors.[86] Cognitive control, and particularly inhibitory control

over behavior, is impaired in both addiction and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder.[87][88] Stimulus-driven behavioral responses (i.e., stimulus control)

that are associated with a particular rewarding stimulus tend to dominate one's behavior in an addiction.[88]

Stimulus control of behavior [ edit ] Operant conditioning Extinction

See also: Stimulus control

In operant conditioning, behavior is Reinforcement Punishment

Increase behavior Decrease behavior

influenced by outside stimulus, such

as a drug. The operant conditioning

theory of learning is useful in Positive reinforcement Positive punishment Negative punishment

understanding why the mood-altering Add appetitive stimulus Negative reinforcement Add noxious stimulus Remove appetitive stimulus

following correct behavior following behavior following behavior

or stimulating consequences of drug

use can reinforce continued use (an

example of positive reinforcement) Escape

Active avoidance

and why the addicted person seeks to Remove noxious stimulus

Behavior avoids noxious stimulus

following correct behavior

avoid withdrawal through continued

use (an example of negative

reinforcement). Stimulus control is using the absence of the stimulus or presence of a reward to influence the resulting behavior.[85]

Cognitive control of behavior [ edit ]

See also: Cognitive control

Cognitive control is the intentional selection of thoughts, behaviors, and emotions, based on our environment. It has been shown that drugs alter the way

our brains function, and its structure.[89][2] Cognitive functions such as learning, memory, and impulse control, are affected by drugs.[89] These effects

promote drug use, as well as hinder the ability to abstain from it.[89] The increase in dopamine release is prominent in drug use, specifically in the ventral

striatum and the nucleus accumbens.[89] Dopamine is responsible for producing pleasurable feelings, as well driving us to perform important life activities.

Addictive drugs cause a significant increase in this reward system, causing a large increase in dopamine signaling as well as increase in reward-seeking

behavior, in turn motivating drug use.[89][2] This promotes the development of a maladaptive drug to stimulus relationship.[90] Early drug use leads to these

maladaptive associations, later affecting cognitive processes used for coping, which are needed to successfully abstain from them.[89][85]

Risk factors [ edit ]

Further information: Addiction vulnerability

A number of genetic and environmental risk factors exist for developing an addiction.[3][91] Genetic and environmental risk factors each account for roughly

half of an individual's risk for developing an addiction;[3] the contribution from epigenetic risk factors to the total risk is unknown.[91] Even in individuals with

a relatively low genetic risk, exposure to sufficiently high doses of an addictive drug for a long period of time (e.g., weeks–months) can result in an

addiction.[3] Adverse childhood events are associated with negative health outcomes, such as substance use disorder. Childhood abuse or exposure to

violent crime is related to developing a mood or anxiety disorder, as well as a substance dependence risk.[92]

Genetic factors [ edit ]

Main articles: Epigenetics of cocaine addiction and Molecular and epigenetic mechanisms of alcoholism

Further information: Alcoholism § Genetic variation, History of drinking, History of smoking, and Prevalence of tobacco use

Genetic factors, along with socio-environmental (e.g., psychosocial) factors, have been established as significant contributors to addiction

vulnerability.[3][91][93][33] Studies done on 350 hospitalized drug-dependent patients showed that over half met the criteria for alcohol abuse, with a role of

familial factors being prevalent.[94] Genetic factors account for 40–60% of the risk factors for alcoholism.[95] Similar rates of heritability for other types of

drug addiction have been indicated, specifically in genes that encode the Alpha5 Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptor.[96] Knestler hypothesized in 1964 that a

gene or group of genes might contribute to predisposition to addiction in several ways. For example, altered levels of a normal protein due to

environmental factors may change the structure or functioning of specific brain neurons during development. These altered brain neurons could affect the

susceptibility of an individual to an initial drug use experience. In support of this hypothesis, animal studies have shown that environmental factors such as

stress can affect an animal's genetic expression.[96]

In humans, twin studies into addiction have provided some of the highest-quality evidence of this link, with results finding that if one twin is affected by

addiction, the other twin is likely to be as well, and to the same substance.[97] Further evidence of a genetic component is research findings from family

studies which suggest that if one family member has a history of addiction, the chances of a relative or close family developing those same habits are

much higher than one who has not been introduced to addiction at a young age.[98]

The data implicating specific genes in the development of drug addiction is mixed for most genes. Many addiction studies that aim to identify specific genes

focus on common variants with an allele frequency of greater than 5% in the general population. When associated with disease, these only confer a small

amount of additional risk with an odds ratio of 1.1–1.3 percent; this has led to the development the rare variant hypothesis, which states that genes with

low frequencies in the population (<1%) confer much greater additional risk in the development of the disease.[99]

Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) are used to examine genetic associations with dependence, addiction, and drug use.[93] These studies rarely

identify genes from proteins previously described via animal knockout models and candidate gene analysis. Instead, large percentages of genes involved

in processes such as cell adhesion are commonly identified. The important effects of endophenotypes are typically not capable of being captured by these

methods. Genes identified in GWAS for drug addiction may be involved either in adjusting brain behavior before drug experiences, subsequent to them, or

both.[100]

Environmental factors [ edit ]

Environmental risk factors for addiction are the experiences of an individual during their lifetime that interact with the individual's genetic composition to

increase or decrease his or her vulnerability to addiction.[3] For example, after the nationwide outbreak of COVID-19, more people quit (vs. started)

smoking; and smokers, on average, reduced the quantity of cigarettes they consumed.[101] More generally, a number of different environmental factors

have been implicated as risk factors for addiction, including various psychosocial stressors. The National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) and studies cite

lack of parental supervision, the prevalence of peer substance use, substance availability, and poverty as risk factors for substance use among children

and adolescents.[102][29] The brain disease model of addiction posits that an individual's exposure to an addictive drug is the most significant environmental

risk factor for addiction.[103] Many researchers, including neuroscientists, indicate that the brain disease model presents a misleading, incomplete, and

potentially detrimental explanation of addiction.[104]

The psychoanalytic theory model defines addiction as a form of defense against feelings of hopelessness and helplessness as well as a symptom of failure

to regulate powerful emotions related to adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), various forms of maltreatment and dysfunction experienced in childhood.

In this case, the addictive substance provides brief but total relief and positive feelings of control.[85] The Adverse Childhood Experiences Study by the

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has shown a strong dose–response relationship between ACEs and numerous health, social, and behavioral

problems throughout a person's lifespan, including substance use disorder.[105] Children's neurological development can be permanently disrupted when

they are chronically exposed to stressful events such as physical, emotional, or sexual abuse, physical or emotional neglect, witnessing violence in the

household, or a parent being incarcerated or having a mental illness. As a result, the child's cognitive functioning or ability to cope with negative or

disruptive emotions may be impaired. Over time, the child may adopt substance use as a coping mechanism or as a result of reduced impulse control,

particularly during adolescence.[105][29][85] Vast amounts of children who experienced abuse have gone on to have some form of addiction in their

adolescence or adult life.[106] This pathway towards addiction that is opened through stressful experiences during childhood can be avoided by a change in

environmental factors throughout an individual's life and opportunities of professional help.[106] If one has friends or peers who engage in drug use

favorably, the chances of them developing an addiction increases. Family conflict and home management is a cause for one to become engaged in alcohol

or other drug use.[107]

Age [ edit ]

Adolescence represents a period of increased vulnerability for developing an addiction.[108] In adolescence, the incentive-rewards systems in the brain

mature well before the cognitive control center. This consequentially grants the incentive-rewards systems a disproportionate amount of power in the

behavioral decision-making process. Therefore, adolescents are increasingly likely to act on their impulses and engage in risky, potentially addicting

behavior before considering the consequences.[109] Not only are adolescents more likely to initiate and maintain drug use, but once addicted they are more

resistant to treatment and more liable to relapse.[110][111]

Most individuals are exposed to and use addictive drugs for the first time during their teenage years.[112] In the United States, there were just over

2.8 million new users of illicit drugs in 2013 (7,800 new users per day);[112] among them, 54.1% were under 18 years of age.[112] In 2011, there were

approximately 20.6 million people in the United States over the age of 12 with an addiction.[113] Over 90% of those with an addiction began drinking,

smoking or using illicit drugs before the age of 18.[113]

Comorbid disorders [ edit ]

Individuals with comorbid (i.e., co-occurring) mental health disorders such as depression, anxiety, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) or post-

traumatic stress disorder are more likely to develop substance use disorders.[114][115][116][29] The NIDA cites early aggressive behavior as a risk factor for

substance use.[102] The National Bureau of Economic Research found that there is a "definite connection between mental illness and the use of addictive

substances" and a majority of mental health patients participate in the use of these substances: 38% alcohol, 44% cocaine, and 40% cigarettes.[117]

Epigenetic [ edit ]

Epigenetics is the study of stable phenotypic changes that do not involve alterations in the DNA sequence.[118] Illicit drug use has been found to cause

epigenetic changes in DNA methylation, as well as chromatin remodeling.[119] The epigenetic state of chromatin may pose as a risk for the development of

substance addictions.[119] It has been found that emotional stressors, as well as social adversities may lead to an initial epigenetic response, which causes

an alteration to the reward-signalling pathways.[119] This change may predispose one to experience a positive response to drug use.[119]

Transgenerational epigenetic inheritance [ edit ]

Main article: Transgenerational epigenetic inheritance

Epigenetic genes and their products (e.g., proteins) are the key components through which environmental influences can affect the genes of an

individual:[91] they serve as the mechanism responsible for transgenerational epigenetic inheritance, a phenomenon in which environmental influences on

the genes of a parent can affect the associated traits and behavioral phenotypes of their offspring (e.g., behavioral responses to environmental stimuli).[91]

In addiction, epigenetic mechanisms play a central role in the pathophysiology of the disease;[3] it has been noted that some of the alterations to the

epigenome which arise through chronic exposure to addictive stimuli during an addiction can be transmitted across generations, in turn affecting the

behavior of one's children (e.g., the child's behavioral responses to addictive drugs and natural rewards).[91][120]

The general classes of epigenetic alterations that have been implicated in transgenerational epigenetic inheritance include DNA methylation, histone

modifications, and downregulation or upregulation of microRNAs.[91] With respect to addiction, more research is needed to determine the specific heritable

epigenetic alterations that arise from various forms of addiction in humans and the corresponding behavioral phenotypes from these epigenetic alterations

that occur in human offspring.[91][120] Based on preclinical evidence from animal research, certain addiction-induced epigenetic alterations in rats can be

transmitted from parent to offspring and produce behavioral phenotypes that decrease the offspring's risk of developing an addiction.[note 1][91] More

generally, the heritable behavioral phenotypes that are derived from addiction-induced epigenetic alterations and transmitted from parent to offspring may

serve to either increase or decrease the offspring's risk of developing an addiction.[91][120]

Mechanisms [ edit ]

Addiction is a disorder of the brain's reward system developing through transcriptional and epigenetic mechanisms as a result of chronically high levels of

exposure to an addictive stimulus (e.g., eating food, the use of cocaine, engagement in sexual activity, participation in high-thrill cultural activities such as

gambling, etc.) over extended time.[3][121][34] DeltaFosB (ΔFosB), a gene transcription factor, is a critical component and common factor in the

development of virtually all forms of behavioral and drug addictions.[121][34][122][35] Two decades of research into ΔFosB's role in addiction have

demonstrated that addiction arises, and the associated compulsive behavior intensifies or attenuates, along with the overexpression of ΔFosB in the D1-

type medium spiny neurons of the nucleus accumbens.[3][121][34][122] Due to the causal relationship between ΔFosB expression and addictions, it is used

preclinically as an addiction biomarker.[3][121][122] ΔFosB expression in these neurons directly and positively regulates drug self-administration and reward

sensitization through positive reinforcement, while decreasing sensitivity to aversion.[note 2][3][121]

Chronic addictive drug use causes alterations in gene

Transcription factor glossary

expression in the mesocorticolimbic

gene expression – the process by which information from a gene is used in the synthesis of a functional

projection.[35][130][131] The most important transcription

gene product such as a protein

factors that produce these alterations are ΔFosB,

transcription – the process of making messenger RNA (mRNA) from a DNA template by RNA polymerase

cAMP response element binding protein (CREB), and transcription factor – a protein that binds to DNA and regulates gene expression by promoting or

nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB).[35] ΔFosB is the most suppressing transcription

significant biomolecular mechanism in addiction transcriptional regulation – controlling the rate of gene transcription for example by helping or hindering

because the overexpression of ΔFosB in the D1-type RNA polymerase binding to DNA

upregulation, activation, or promotion – increase the rate of gene transcription

medium spiny neurons in the nucleus accumbens is

downregulation, repression, or suppression – decrease the rate of gene transcription

necessary and sufficient for many of the neural

coactivator – a protein (or a small molecule) that works with transcription factors to increase the rate of

adaptations and behavioral effects (e.g., expression- gene transcription

dependent increases in drug self-administration and corepressor – a protein (or a small molecule) that works with transcription factors to decrease the rate of

reward sensitization) seen in drug addiction.[35] gene transcription

ΔFosB expression in nucleus accumbens D1-type response element – a specific sequence of DNA that a transcription factor binds to

medium spiny neurons directly and positively · ·

regulates drug self-administration and reward

Signaling cascade in the nucleus accumbens that results in psychostimulant addiction

sensitization through positive reinforcement while

· ·

decreasing sensitivity to aversion.[note 2][3][121] ΔFosB

Note: colored text

has been implicated in mediating addictions to many

contains article links.

different drugs and drug classes, including alcohol, [Color legend 1]

Cav1.2

amphetamine and other substituted amphetamines,

cannabinoids, cocaine, methylphenidate, nicotine,

opiates, phenylcyclidine, and propofol, among NMDAR CaMKII

CaM

others.[121][35][130][132][133] ΔJunD, a transcription

factor, and G9a, a histone methyltransferase, both

PP2B PP1 CREB

oppose the function of ΔFosB and inhibit increases in

its expression.[3][35][134] Increases in nucleus AMPAR

accumbens ΔJunD expression (via viral vector- DARPP-32

ΔFosB

mediated gene transfer) or G9a expression (via DRD1 c-Fos

JunD

pharmacological means) reduces, or with a large Gs

increase can even block, many of the neural and SIRT1

DRD5 AC PKA

behavioral alterations that result from chronic high- HDAC1

dose use of addictive drugs (i.e., the alterations DRD2 Gi/o Nuclear pore

cAMP

mediated by ΔFosB).[122][35]

DRD3 Nuclear membrane

ΔFosB plays an important role in regulating

DRD4

behavioral responses to natural rewards, such as

palatable food, sex, and exercise.[35][135] Natural Plasma membrane

rewards, like drugs of abuse, induce gene expression

of ΔFosB in the nucleus accumbens, and chronic

acquisition of these rewards can result in a similar

pathological addictive state through ΔFosB

overexpression.[34][35][135] Consequently, ΔFosB is

the key transcription factor involved in addictions to

natural rewards (i.e., behavioral addictions) as

cAMP

well;[35][34][135] in particular, ΔFosB in the nucleus

accumbens is critical for the reinforcing effects of This diagram depicts the signaling events in the brain's reward center that are induced by chronic high-

sexual reward.[135] Research on the interaction dose exposure to psychostimulants that increase the concentration of synaptic dopamine, like

amphetamine, methamphetamine, and phenethylamine. Following presynaptic dopamine and glutamate co-

between natural and drug rewards suggests that

release by such psychostimulants,[123][124] postsynaptic receptors for these neurotransmitters trigger internal

dopaminergic psychostimulants (e.g., amphetamine) signaling events through a cAMP-dependent pathway and a calcium-dependent pathway that ultimately

and sexual behavior act on similar biomolecular result in increased CREB phosphorylation.[123][125][126] Phosphorylated CREB increases levels of ΔFosB,

mechanisms to induce ΔFosB in the nucleus which in turn represses the c-Fos gene with the help of corepressors;[123][127][128] c-Fos repression acts as a

molecular switch that enables the accumulation of ΔFosB in the neuron.[129] A highly stable (phosphorylated)

accumbens and possess bidirectional cross- form of ΔFosB, one that persists in neurons for 1–2 months, slowly accumulates following repeated high-

sensitization effects that are mediated through dose exposure to stimulants through this process.[127][128] ΔFosB functions as "one of the master control

ΔFosB.[34][43][44] This phenomenon is notable since, proteins" that produces addiction-related structural changes in the brain, and upon sufficient accumulation,

with the help of its downstream targets (e.g., nuclear factor kappa B), it induces an addictive state.[127][128]

in humans, a dopamine dysregulation syndrome,

characterized by drug-induced compulsive

engagement in natural rewards (specifically, sexual activity, shopping, and gambling), has been observed in some individuals taking dopaminergic

medications.[34]

ΔFosB inhibitors (drugs or treatments that oppose its action) may be an effective treatment for addiction and addictive disorders.[136]

The release of dopamine in the nucleus accumbens plays a role in the reinforcing qualities of many forms of stimuli, including naturally reinforcing stimuli

like palatable food and sex.[137][138][33] Altered dopamine neurotransmission is frequently observed following the development of an addictive state.[34][2] In

humans and lab animals that have developed an addiction, alterations in dopamine or opioid neurotransmission in the nucleus accumbens and other parts

of the striatum are evident.[34] Use of certain drugs (e.g., cocaine) affect cholinergic neurons that innervate the reward system, in turn affecting dopamine

signaling in this region.[139]

Reward system [ edit ]

Main article: Reward system

Mesocorticolimbic pathway [ edit ]

Understanding the pathways in which drugs act and how drugs can alter those ΔFosB accumulation from excessive drug use

pathways is key when examining the biological basis of drug addiction. The reward

pathway, known as the mesolimbic pathway,[2] or its extension, the mesocorticolimbic

pathway, is characterized by the interaction of several areas of the brain.

The projections from the ventral tegmental area (VTA) are a network of

dopaminergic neurons with co-localized postsynaptic glutamate receptors

(AMPAR and NMDAR). These cells respond when stimuli indicative of a reward

are present.[33] The VTA supports learning and sensitization development and

releases dopamine (DA) into the forebrain.[141] These neurons project and

release DA into the nucleus accumbens,[142] through the mesolimbic pathway.

Virtually all drugs causing drug addiction increase the DA release in the

mesolimbic pathway.[143][2]

The nucleus accumbens (NAcc) is one output of the VTA projections. The nucleus

accumbens itself consists mainly of GABAergic medium spiny neurons

(MSNs).[144] The NAcc is associated with acquiring and eliciting conditioned

behaviors, and is involved in the increased sensitivity to drugs as addiction

progresses.[141][32] Overexpression of ΔFosB in the nucleus accumbens is a

necessary common factor in essentially all known forms of addiction;[3] ΔFosB is

a strong positive modulator of positively reinforced behaviors.[3]

The prefrontal cortex, including the anterior cingulate and orbitofrontal

cortices,[145][32] is another VTA output in the mesocorticolimbic pathway; it is

Top: this depicts the initial effects of high dose exposure to an addictive

important for the integration of information which helps determine whether a

drug on gene expression in the nucleus accumbens for various Fos

behavior will be elicited.[146] It is critical for forming associations between the family proteins (i.e., c-Fos, FosB, ΔFosB, Fra1, and Fra2).

rewarding experience of drug use and cues in the environment. Importantly, these Bottom: this illustrates the progressive increase in ΔFosB expression in

the nucleus accumbens following repeated twice daily drug binges,

cues are strong mediators of drug-seeking behavior and can trigger relapse even

where these phosphorylated (35–37 kilodalton) ΔFosB isoforms persist

after months or years of abstinence.[147][2] in the D1-type medium spiny neurons of the nucleus accumbens for up

to 2 months.[128][140]

Other brain structures that are involved in addiction include:

The basolateral amygdala projects into the NAcc and is thought to be important

for motivation.[146]

The hippocampus is involved in drug addiction, because of its role in learning and memory. Much of this evidence stems from investigations showing

that manipulating cells in the hippocampus alters DA levels in NAcc and firing rates of VTA dopaminergic cells.[142]

Role of dopamine and glutamate [ edit ]

Dopamine is the primary neurotransmitter of the reward system in the brain. It plays a role in regulating movement, emotion, cognition, motivation, and

feelings of pleasure.[148] Natural rewards, like eating, as well as recreational drug use cause a release of dopamine, and are associated with the reinforcing

nature of these stimuli.[148][149][33] Nearly all addictive drugs, directly or indirectly, act on the brain's reward system by heightening dopaminergic

activity.[150][2]

Excessive intake of many types of addictive drugs results in repeated release of high amounts of dopamine, which in turn affects the reward pathway

directly through heightened dopamine receptor activation. Prolonged and abnormally high levels of dopamine in the synaptic cleft can induce receptor

downregulation in the neural pathway. Downregulation of mesolimbic dopamine receptors can result in a decrease in the sensitivity to natural

reinforcers.[148]

Drug seeking behavior is induced by glutamatergic projections from the prefrontal cortex to the nucleus accumbens. This idea is supported with data from

experiments showing that drug seeking behavior can be prevented following the inhibition of AMPA glutamate receptors and glutamate release in the

nucleus accumbens.[145]

Reward sensitization [ edit ]

Reward sensitization is a process that causes an Neural and behavioral effects of validated ΔFosB transcriptional targets in the

increase in the amount of reward (specifically, striatum[121][151]

incentive salience[note 5]) that is assigned by the

Target Target

brain to a rewarding stimulus (e.g., a drug). In simple Neural effects Behavioral effects

gene expression

terms, when reward sensitization to a specific

stimulus (e.g., a drug) occurs, an individual's Molecular switch enabling the chronic

c-Fos ↓ –

"wanting" or desire for the stimulus itself and its induction of ΔFosB[note 3]

associated cues increases.[153][152][154] Reward ↓

dynorphin [note 4]

• Downregulation of κ-opioid feedback loop • Increased drug reward

sensitization normally occurs following chronically

high levels of exposure to the stimulus.[2] ΔFosB

• Expansion of NAcc dendritic processes

expression in D1-type medium spiny neurons in the • Increased drug reward

NF-κB ↑ • NF-κB inflammatory response in the NAcc

nucleus accumbens has been shown to directly and • Locomotor sensitization

• NF-κB inflammatory response in the CP

positively regulate reward sensitization involving

drugs and natural rewards.[3][121][122] GluR2 ↑ • Decreased sensitivity to glutamate • Increased drug reward

"Cue-induced wanting" or "cue-triggered wanting", a

• GluR1 synaptic protein phosphorylation Decreased drug reward

form of craving that occurs in addiction, is Cdk5 ↑

• Expansion of NAcc dendritic processes (net effect)

responsible for most of the compulsive behavior that

people with addictions exhibit.[152][154] During the

development of an addiction, the repeated association of otherwise neutral and even non-rewarding stimuli with drug consumption triggers an associative

learning process that causes these previously neutral stimuli to act as conditioned positive reinforcers of addictive drug use (i.e., these stimuli start to

function as drug cues).[152][155][154] As conditioned positive reinforcers of drug use, these previously neutral stimuli are assigned incentive salience (which

manifests as a craving) – sometimes at pathologically high levels due to reward sensitization – which can transfer to the primary reinforcer (e.g., the use of

an addictive drug) with which it was originally paired.[152][155][154]

Research on the interaction between natural and drug rewards suggests that dopaminergic psychostimulants (e.g., amphetamine) and sexual behavior act

on similar biomolecular mechanisms to induce ΔFosB in the nucleus accumbens and possess a bidirectional reward cross-sensitization effect[note 6] that

is mediated through ΔFosB.[34][43][44] In contrast to ΔFosB's reward-sensitizing effect, CREB transcriptional activity decreases user's sensitivity to the

rewarding effects of the substance. CREB transcription in the nucleus accumbens is implicated in psychological dependence and symptoms involving a

lack of pleasure or motivation during drug withdrawal.[3][140][151]

Summary of addiction-related plasticity

Type of reinforcer

Form of neuroplasticity Physical

High fat or Sexual Environmental Sources

or behavioral plasticity Opiates Psychostimulants exercise

sugar food intercourse enrichment

(aerobic)

ΔFosB expression in

nucleus accumbens D1-type ↑ ↑ ↑ ↑ ↑ ↑ [34]

MSNs

Behavioral plasticity

Escalation of intake Yes Yes Yes [34]

Psychostimulant [34]

Yes Not applicable Yes Yes Attenuated Attenuated

cross-sensitization

Psychostimulant [34]

↑ ↑ ↓ ↓ ↓

self-administration

Psychostimulant

conditioned place ↑ ↑ ↓ ↑ ↓ ↑ [34]

preference

Reinstatement of drug- [34]

↑ ↑ ↓ ↓

seeking behavior

Neurochemical plasticity

CREB phosphorylation [34]

↓ ↓ ↓ ↓ ↓

in the nucleus accumbens

Sensitized dopamine

response No Yes No Yes [34]

in the nucleus accumbens

Altered striatal dopamine ↑DRD1, ↓DRD2, ↑DRD1, ↓DRD2, [34]

↓DRD2, ↑DRD3 ↑DRD2 ↑DRD2

signaling ↑DRD3 ↑DRD3

No change or

Altered striatal opioid ↑μ-opioid receptors ↑μ-opioid ↑μ-opioid [34]

↑μ-opioid No change No change

signaling ↑κ-opioid receptors receptors receptors

receptors

↑dynorphin

Changes in striatal opioid [34]

No change: ↑dynorphin ↓enkephalin ↑dynorphin ↑dynorphin

peptides

enkephalin

Mesocorticolimbic synaptic plasticity

Number of dendrites in the [34]

↓ ↑ ↑

nucleus accumbens

Dendritic spine density in [34]

↓ ↑ ↑

the nucleus accumbens

Neuroepigenetic mechanisms [ edit ]

Further information: Neuroepigenetics and Chromatin remodeling

Altered epigenetic regulation of gene expression within the brain's reward system plays a significant and complex role in the development of drug

addiction.[134][156] Addictive drugs are associated with three types of epigenetic modifications within neurons.[134] These are (1) histone modifications, (2)

epigenetic methylation of DNA at CpG sites at (or adjacent to) particular genes, and (3) epigenetic downregulation or upregulation of microRNAs which

have particular target genes.[134][35][156] As an example, while hundreds of genes in the cells of the nucleus accumbens (NAc) exhibit histone modifications

following drug exposure – particularly, altered acetylation and methylation states of histone residues[156] – most other genes in the NAc cells do not show

such changes.[134]

Diagnosis [ edit ]

Further information: Substance use disorder § Diagnosis, and Problem gambling § Diagnosis

Classification [ edit ]

DSM-5 [ edit ]

The fifth edition of the DSM uses the term substance use disorder to refer to a spectrum of drug use-related disorders. The DSM-5 eliminates the terms

abuse and dependence from diagnostic categories, instead using the specifiers of mild, moderate and severe to indicate the extent of disordered use.

These specifiers are determined by the number of diagnostic criteria present in a given case. In the DSM-5, the term drug addiction is synonymous with

severe substance use disorder.[19][25]

The DSM-5 introduced a new diagnostic category for behavioral addictions. Problem gambling is the only condition included in this category in the fifth

edition.[21] Internet gaming disorder is listed as a "condition requiring further study" in the DSM-5.[157]

Past editions have used physical dependence and the associated withdrawal syndrome to identify an addictive state. Physical dependence occurs when

the body has adjusted by incorporating the substance into its "normal" functioning – i.e., attains homeostasis – and therefore physical withdrawal

symptoms occur on cessation of use.[158] Tolerance is the process by which the body continually adapts to the substance and requires increasingly larger

amounts to achieve the original effects. Withdrawal refers to physical and psychological symptoms experienced when reducing or discontinuing a

substance that the body has become dependent on. Symptoms of withdrawal generally include but are not limited to body aches, anxiety, irritability, intense

cravings for the substance, dysphoria, nausea, hallucinations, headaches, cold sweats, tremors, and seizures. During acute physical opioid withdrawal,

symptoms of restless legs syndrome are common and may be profound. This phenomenon originated the idiom "kicking the habit".

Medical researchers who actively study addiction have criticized the DSM classification of addiction for being flawed and involving arbitrary diagnostic

criteria.[159]

ICD-11 [ edit ]

The eleventh revision of the International Classification of Diseases, commonly referred to as ICD-11, conceptualizes diagnosis somewhat differently. ICD-

11 first distinguishes between problems with psychoactive substance use ("Disorders due to substance use") and behavioral addictions ("Disorders due to

addictive behaviours").[15] With regard to psychoactive substances, ICD-11 explains that the included substances initially produce "pleasant or appealing

psychoactive effects that are rewarding and reinforcing with repeated use, [but] with continued use, many of the included substances have the capacity to

produce dependence. They have the potential to cause numerous forms of harm, both to mental and physical health."[160] Instead of the DSM-5 approach

of one diagnosis ("Substance Use Disorder") covering all types of problematic substance use, ICD-11 offers three diagnostic possibilities: 1) Episode of

Harmful Psychoactive Substance Use, 2) Harmful Pattern of Psychoactive Substance Use, and 3) Substance Dependence.[160]

Prevention [ edit ]

Main articles: Harm reduction and Preventive healthcare

Abuse liability [ edit ]

Abuse or addiction liability is the tendency to use drugs in a non-medical situation. This is typically for euphoria, mood changing, or sedation.[161] Abuse

liability is used when the person using the drugs wants something that they otherwise can not obtain. The only way to obtain this is through the use of

drugs. When looking at abuse liability there are a number of determining factors in whether the drug is abused. These factors are: the chemical makeup of

the drug, the effects on the brain, and the age, vulnerability, and the health (mental and physical) of the population being studied.[161] There are a few

drugs with a specific chemical makeup that leads to a high abuse liability. These are: cocaine, heroin, inhalants, marijuana, MDMA (ecstasy),

methamphetamine, PCP, synthetic cannabinoids, synthetic cathinones (bath salts), nicotine (e.g. tobacco), and alcohol.[162]

Treatment and management [ edit ]

See also: Addiction recovery groups, Cognitive behavioral therapy, and Drug rehabilitation

To be effective, treatment for addiction that is pharmacological or biologically based need to be accompanied by other interventions such as cognitive

behavioral therapy (CBT), individual and group psychotherapy, behavior modification strategies, twelve-step programs, and residential treatment

facilities.[163][29] The TTM can be used to determine when treatment can begin and which method will be most effective. If treatment begins too early, it can

cause a person to become defensive and resistant to change.[85]

A biosocial approach to the treatment of addiction brings to the fore the social determinants of illness and wellbeing and considers the dynamic and

reciprocal relationships that exist for, and influence, the individual's experience.[164]

The work of A.V. Schlosser (2018) aims to pronounce the individual lived experiences of women receiving medication-assisted treatment (e.g., methadone,

naltrexone, burprenorphine) in a long-term rehabilitation setting, through a twenty month long ethnographic fieldwork investigation. This person-centered

research shows how the experiences of these women "emerge from stable systems of inequality based in intersectional gender, race, and class

marginalization entangled with processes of intra-action."[165] Viewing addiction treatment through this lens highlights the importance of framing clients'

own bodies as "social flesh". As Schlosser (2018) points out, "client bodies" as well as the "embodied experiences of self and social belonging emerge in

and through the structures, temporalities, and expectations of the treatment centre."[165]

Biotechnologies make up a large portion of the future treatments for addiction[citation needed] including deep-brain stimulation, agonist and antagonist

implants and hapten conjugate vaccines. Vaccinations against addiction specifically overlaps with the belief that memory plays a large role in the damaging

effects of addiction and relapses.[medical citation needed] Hapten conjugate vaccines are designed to block opioid receptors in one area, while allowing other

receptors to behave normally. Essentially, once a high can no longer be achieved in relation to a traumatic event, the relation of drugs to a traumatic

memory can be disconnected and therapy can play a role in treatment.[166]

Behavioral therapy [ edit ]

CBT proposes four assumptions essential to the approach to treatment: addiction is a learned behavior, it emerges in an environmental context, it is

developed and maintained by particular thought patterns and processes, and CBT can be integrated well with other treatment and management

approaches as they all have similar goals.[85] CBT, (e.g., relapse prevention), motivational interviewing, and a community reinforcement approach are

effective interventions with moderate effect sizes.[167]

Interventions focusing on impulsivity and sensation seeking are successful in decreasing substance use.[32] Cue exposure uses ideas from classical

conditioning theory to change the learned behavioral response of someone addicted to a cue or trigger. Contingency management uses ideas from operant

conditioning to use meaningful positive reinforcements to influence addiction behaviors towards sobriety.[85]

Addiction recovery groups draw on different methods and models and rely on the success of vicarious learning, where people imitate behavior they

observe as rewarding among their own social group or status as well as those perceived as being of a higher status.[85]

Substance addiction in children is complex and requires multifacted behavioral therapy. Family therapy and school-based interventions have had minor but

lasting results. Innovative treatments are still needed for areas where relevant therapies are unavailable.[29]

Consistent aerobic exercise, especially endurance exercise (e.g., marathon running), prevents the development of certain drug addictions and is an

effective adjunct treatment for drug addiction, and for psychostimulant addiction in particular.[34][168][169][170][171] Consistent aerobic exercise magnitude-

dependently (i.e., by duration and intensity) reduces drug addiction risk, which appears to occur through the reversal of drug induced addiction-related

neuroplasticity.[34][169] Exercise may prevent the development of drug addiction by altering ΔFosB or c-Fos immunoreactivity in the striatum or other parts

of the reward system.[171] Aerobic exercise decreases drug self-administration, reduces the likelihood of relapse, and induces opposite effects on striatal

dopamine receptor D2 (DRD2) signaling (increased DRD2 density) to those induced by addictions to several drug classes (decreased DRD2

density).[34][169] Consequently, consistent aerobic exercise may lead to better treatment outcomes when used as an adjunct treatment for drug

addiction.[34][169][170]

With a combination of tools such as behavioral therapy, a balanced lifestyle, and individualized relapse plans, relapse is can be more successfully

avoided.[85]

Medication [ edit ]

Alcohol addiction [ edit ]

Main article: Alcoholism

Further information: Alcohol and health and Long-term effects of alcohol

Alcohol, like opioids, can induce a severe state of physical dependence and produce withdrawal symptoms such as delirium tremens. Because of this,

treatment for alcohol addiction usually involves a combined approach dealing with dependence and addiction simultaneously. Benzodiazepines have the

largest and the best evidence base in the treatment of alcohol withdrawal and are considered the gold standard of alcohol detoxification.[172]

Pharmacological treatments for alcohol addiction include drugs like naltrexone (opioid antagonist), disulfiram, acamprosate, and topiramate.[173][174] Rather

than substituting for alcohol, these drugs are intended to affect the desire to drink, either by directly reducing cravings as with acamprosate and topiramate,

or by producing unpleasant effects when alcohol is consumed, as with disulfiram. These drugs can be effective if treatment is maintained, but compliance

can be an issue as patients with disordered alcohol use may forget to take their medication, or discontinue use because of excessive side effects.[175][176]

The opioid antagonist naltrexone has been shown to be an effective treatment for alcoholism, with the effects lasting three to twelve months after the end

of treatment.[177]

Behavioral addictions [ edit ]

This section is transcluded from Behavioral addiction. (edit | history)

Behavioral addiction is a treatable condition. Treatment options include psychotherapy and psychopharmacotherapy (i.e., medications) or a combination of

both. Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is the most common form of psychotherapy used in treating behavioral addictions; it focuses on identifying

patterns that trigger compulsive behavior and making lifestyle changes to promote healthier behaviors. Because cognitive behavioral therapy is considered

a short term therapy, the number of sessions for treatment normally ranges from five to twenty. During the session, therapists will lead patients through the

topics of identifying the issue, becoming aware of one's thoughts surrounding the issue, identifying any negative or false thinking, and reshaping said

negative and false thinking. While CBT does not cure behavioral addiction, it does help with coping with the condition in a healthy way. Currently, there are

no medications approved for treatment of behavioral addictions in general, but some medications used for treatment of drug addiction may also be

beneficial with specific behavioral addictions.[46] Any unrelated psychiatric disorders should be kept under control, and differentiated from the contributing

factors that cause the addiction.

Cannabinoid addiction [ edit ]

Main article: Cannabis addiction

The development of CB1 receptor agonists that have reduced interaction with β-arrestin 2 signaling might be therapeutically useful.[178] As of 2019, there

has been some evidence of effective pharmacological interventions for cannabinoid addiction, but none have been approved.[179]

Nicotine addiction [ edit ]

Main article: Nicotine addiction

Further information: Smoking cessation and Tobacco harm reduction

Another area in which drug treatment has been widely used is in the treatment of nicotine addiction, which usually

involves the use of nicotine replacement therapy, nicotinic receptor antagonists, and/or nicotinic receptor partial

agonists.[180][181] Examples of drugs that act on nicotinic receptors and have been used for treating nicotine

addiction include antagonists like bupropion and the partial agonist varenicline.[180][181] Cytisine, a partial agonist,

is an effective, and affordable cessation treatment for smokers.[182] When access to varenicline and nicotine

replacement therapy is limited (due to availability or cost), cytisine is considered the first line of treatment for Transdermal patch used in nicotine

replacement therapy

smoking cessation.[182]

Opioid addiction [ edit ]

Main article: Opioid use disorder

Further information: Opioid epidemic

Opioids cause physical dependence and treatment typically addresses both dependence and addiction. Physical dependence is treated using replacement

drugs such as buprenorphine (the active ingredient in products such as Suboxone and Subutex) and methadone.[183][184] Although these drugs perpetuate

physical dependence, the goal of opiate maintenance is to provide a measure of control over both pain and cravings. Use of replacement drugs increases

the addicted individual's ability to function normally and eliminates the negative consequences of obtaining controlled substances illicitly. Once a prescribed

dosage is stabilized, treatment enters maintenance or tapering phases. In the United States, opiate replacement therapy is tightly regulated in methadone

clinics and under the DATA 2000 legislation. In some countries, other opioid derivatives such as dihydrocodeine,[185] dihydroetorphine[186] and even

heroin[187][188] are used as substitute drugs for illegal street opiates, with different prescriptions being given depending on the needs of the individual

patient. Baclofen has led to successful reductions of cravings for stimulants, alcohol, and opioids and alleviates alcohol withdrawal syndrome. Many

patients have stated they "became indifferent to alcohol" or "indifferent to cocaine" overnight after starting baclofen therapy.[189] Some studies show the

interconnection between opioid drug detoxification and overdose mortality.[190]

Psychostimulant addiction [ edit ]

There is no effective and FDA- or EMA-approved pharmacotherapy for any form of psychostimulant addiction.[191] Experimental TAAR1-selective agonists

have significant therapeutic potential as a treatment for psychostimulant addictions.[192]

Research [ edit ]

Anti-drug vaccines (active immunizations) for treatment of cocaine and nicotine addictions were successful in animal studies. Vaccines tested on humans

have been shown as safe with mild to moderate side effects, though did not have firm results confirming efficacy despite producing expected

antibodies.[193] Vaccines which use anti-drug monoclonal antibodies (passive immunization) can mitigate drug-induced positive reinforcement by

preventing the drug from moving across the blood–brain barrier.[194] Current[as of?] vaccine-based therapies are only effective in a relatively small subset of

individuals.[194][195] As of November 2015, vaccine-based therapies are being tested in human clinical trials as a treatment for addiction and preventive

measure against drug overdoses involving nicotine, cocaine, and methamphetamine.[194] The study shows that the vaccine may save lives during a drug

overdose. In this instance, the idea is that the body will respond to the vaccine by quickly producing antibodies to prevent the opioids from accessing the

brain.[196]

Since addiction involves abnormalities in glutamate and GABAergic neurotransmission,[197][198] receptors associated with these neurotransmitters (e.g.,

AMPA receptors, NMDA receptors, and GABAB receptors) are potential therapeutic targets for addictions.[197][198][199][200] N-acetylcysteine, which affects

metabotropic glutamate receptors and NMDA receptors, has shown some benefit involving addictions to cocaine, heroin, and cannabinoids.[197] It may be

useful as an adjunct therapy for addictions to amphetamine-type stimulants, but more clinical research is required.[197]

Current medical reviews of research involving lab animals have identified a drug class – class I histone deacetylase inhibitors[note 7] – that indirectly inhibits

the function and further increases in the expression of accumbal ΔFosB by inducing G9a expression in the nucleus accumbens after prolonged

use.[122][134][201][156] These reviews and subsequent preliminary evidence which used oral administration or intraperitoneal administration of the sodium

salt of butyric acid or other class I HDAC inhibitors for an extended period indicate that these drugs have efficacy in reducing addictive behavior in lab

animals[note 8] that have developed addictions to ethanol, psychostimulants (i.e., amphetamine and cocaine), nicotine, and opiates.[134][156][202][203] Few

clinical trials involving humans with addictions and any HDAC class I inhibitors have been conducted to test for treatment efficacy in humans or identify an

optimal dosing regimen.[note 9]

Gene therapy for addiction is an active area of research. One line of gene therapy research involves the use of viral vectors to increase the expression of

dopamine D2 receptor proteins in the brain.[205][206][207][208][209]

Epidemiology [ edit ]

Further information: Countries by alcohol consumption, Opioid epidemic, and Prevalence of tobacco use

Due to cultural variations, the proportion of individuals who develop a drug or behavioral addiction within a specified time period (i.e., the prevalence)

varies over time, by country, and across national population demographics (e.g., by age group, socioeconomic status, etc.).[91] Where addiction is viewed

as unacceptable, there will be fewer people addicted.

Asia [ edit ]

The prevalence of alcohol dependence is not as high as is seen in other regions. In Asia, not only socioeconomic factors but biological factors influence

drinking behavior.[210]

Internet addiction disorder is highest in the Philippines, according to both the IAT (Internet Addiction Test) – 5% and the CIAS-R (Revised Chen Internet

Addiction Scale) – 21%.[211]

Australia [ edit ]

Further information: Alcoholism in rural Australia

The prevalence of substance use disorder among Australians was reported at 5.1% in 2009.[212] In 2019 the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare

conducted a national drug survey that quantified drug use for various types of drugs and demographics.[213] The national[specify] found that in 2019, 11% of

people over 14 years old smoke daily; that 9.9% of those who drink alcohol, which equates to 7.5% of the total population age 14 or older, may qualify as

alcohol dependent; that 17.5% of the 2.4 million people who used cannabis in the last year may have hazardous use or a dependence problem; and that

63.5% of about 300000 recent users of meth and amphetamines were at risk for developing problem use.[213]

Europe [ edit ]

Further information: Alcoholism in Ireland and Alcoholism in Russia

In 2015, the estimated prevalence among the adult population was 18.4% for heavy episodic alcohol use (in the past 30 days); 15.2% for daily tobacco

smoking; and 3.8% for cannabis use, 0.77% for amphetamine use, 0.37% for opioid use, and 0.35% for cocaine use in 2017. The mortality rates for alcohol

and illicit drugs were highest in Eastern Europe.[214] Data shows a downward trend of alcohol use among children 15 years old in most European countries

between 2002 and 2014. First-time alcohol use before the age of 13 was recorded for 28% of European children in 2014.[29]

United States [ edit ]

Further information: Cocaine in the United States, Crack epidemic in the United States, and Opioid epidemic in the United States