Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Jurnal 3

Uploaded by

Reza ChandraOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Jurnal 3

Uploaded by

Reza ChandraCopyright:

Available Formats

www.nature.

com/bdjopen

ARTICLE OPEN

Professionalism in dentistry: deconstructing common

terminology

1✉ 1 1

Andrew Trathen , Sasha Scambler and Jennifer E. Gallagher

© Crown 2022

BACKGROUND: There is a social expectation that dentists demonstrate professionalism. Although the General Dental Council puts

it at the heart of their regulatory agenda, there is not yet consensus on the meaning and implications of the term.

OBJECTIVE: To explore practising dentists’ understanding of the character traits commonly associated with professionalism and

what these mean in practice.

METHOD: Constructivist grounded theory was employed throughout this study. Qualitative, in-depth interviews were conducted

with dental professionals in England recruited through theoretical sampling to saturation point. Interviews used a topic guide

informed by the literature, and analysis was conducted through constant comparison during data collection.

RESULTS: The study found that traits commonly associated with professionalism in the literature were difficult for dentists to define

clearly or operationalise in a clinical setting. There was disagreement over how some traits should be understood, and it was

1234567890();,:

unclear to participants how, or indeed if, the listed traits were directly relevant to practice in their current form.

CONCLUSION: Rather than expecting unconditional adherence to an externally imposed definition, further exploration is required

to understand how health professionals make sense of professionalism by reference to their lived experiences and worldviews.

IN BRIEF:

● Institutional expectations of professionalism, defined through character traits and behaviours, do not appear to map neatly on

to the experiences of dental professionals.

● Straightforward, apparently uncontroversial terms elicited a wide range of responses, including disagreement. This brought in

to question whether achieving consensus is possible.

● Analysing how our respondents understood the terms by reference to the meanings they constructed from lived experience

offers deeper insights.

BDJ Open (2022)8:21 ; https://doi.org/10.1038/s41405-022-00105-9

INTRODUCTION Most substantive efforts at understanding and promoting

The healthcare perspective on professionalism recognises an professionalism in healthcare have taken the approach advocated

ethical duty to the people that the professions serve and building by Inui [1]. This involves formulating lists of attributes and

a shared set of values is considered an important part of fulfilling codifying them into a set of guidelines for professionalism [10–12],

this duty [1]. One of the persistent and intractable difficulties of and the discourse around this tends to be institutionalised [13].

trying to use professionalism in this way is that it is dependent on Educators at universities and working groups at national associa-

reaching consensus over what the values and behaviours that tions and colleges expend resources on the professionalism

constitute professionalism should be. Reaching a shared under- project. Over time, this has led to the development of a range of

standing has been difficult, but there is broad agreement that definitions based on character traits seen as related to profession-

some basic principles such as putting the needs of the patient alism in a health environment [14].

first, learning, and being virtuous should be taught, with many These lists of character attributes portray the ‘ideal’ healthcare

also citing the need for assessment and measurement [2]. professional. This functionalist [15], aspirational, ideal-archetype

As in other areas of healthcare, professionalism in dentistry has model of professionalism has cross-cultural applicability [16–18],

received significant attention through the years [3–7], with efforts and is useful for teaching undergraduates, as they will have very

usually directed at trying to clarify what the term means, and how limited experience of practice and will be developing their

it should be operationalised by practitioners, educators, and professional worldviews both formally and informally [19, 20].

regulators [8, 9]. The work reflects a similar long-term effort in However, as a recently graduated dentist gains experience in

medicine to deepen our understanding of what the term means, practice outside the relatively protected world of their training

and how it is valuable to patients and healthcare professionals. institution, they may see professional ideals learned as an

Faculty of Dentistry, Oral & Craniofacial Sciences, Centre for Host Microbiome Interactions, King’s College London, London, UK. ✉email: andrew.3.trathen@kcl.ac.uk

1

Received: 24 December 2021 Accepted: 11 January 2022

A. Trathen et al.

2

undergraduate through a different lens. A host of factors will private practitioners who had reservations about how NHS care was

influence how they understand their professional role and the delivered in the UK. A later phase of theoretical sampling sought dentists

duties they have, beyond the formalised standards and guidelines who moved away from a primary care environment to explore their

set by universities, Royal Colleges, and the General Dental Council. reasons for doing so. Data were collected between 2012 and 2015, with a

If we try to remedy this by moving away from the ideal- final period of collection in 2017.

We adopted the CGT method as described by Charmaz [28, 31, 32]. This

archetype model, things become more nebulous. It potentially method is well suited for generating novel theory, and ensures it emerges

leaves professionalism as “an umbrella that covers a host of from and remains linked to the data [33]. The constructivist component

complex, somewhat interconnected important ideas that comprise a emphasises the socially constructed frameworks that individuals use to

tangle of elements” [21]. Bundled into this are less virtuous issues make sense of their lived experiences. Interviews used a topic guide

linked to preserving the income and status of the profession. This informed by the literature [34]. This was piloted with two respondents and

corresponds to decades of sociological literature that understands revised in light of the results for subsequent interviews. Initial questions

professionalism in terms of power relations and as a method of explored respondent understandings of terms used in the RCP definition of

labour division [22–24]. High income, autonomy and status require professionalism [11]. Interviews were audio recorded with field notes

taken, and the data transcribed. Duration ranged between approximately

that the profession commits to giving something back to society

45 and 80 min. Data were recorded and coded using NVivo 10 and Word

in return [25], and one view is that institutionalised professional software. Transcriptions were subject to a three-stage coding process.

codes are an effort to demonstrate that they can be trusted to do Initial coding was done tentatively line by line, converting data into

so. The Royal College of Physicians 2005 definition of profession- gerunds (‘doing’ words). Next, focused coding highlighted the most

alism [11], incorporates character traits which include: important codes and filtered irrelevant ones. The final stage was

theoretical coding, at which point codes were grouped together to

● Integrity generate higher level categories from which theory could be derived [28].

● Compassion Ethics permission was granted by the King’s College London Research

● Excellence Ethics Committee (reference BDM/11/12-27, LRS-17/18-5297).

● Reliability In total, 24 dental professionals consented to participate in one-to-one

● Altruism interviews. The age of respondents ranged from 27 to 57 years; 14 were

● Continuous improvement male and 10 female; 9 were early, 11 mid and 4 in late career stages. Two

● Working in partnership with members of the wider informants were DCPs and the remainder dentists. Of these, two worked in

secondary care (one senior consultant and one senior house officer (SHO)

healthcare team.

in restorative dentistry and dental public health) and they received fixed

salaries. The remainder were general dental practitioners, 7 exclusively

This list, they explicitly state: “underpins the trust the public has”. private and 13 NHS (also doing variable amounts of private work). Two had

the experience of working in corporate-owned practices. One was in the

In a 2009 paper [8], Trathen and Gallagher argue that this

process of changing career from dentistry to medicine, moving from MBBS

definition, although originally developed within medicine, could to foundation training. 18 respondents were based in greater London, two

potentially be transferable to dentistry because it comes from a of whom operated from central London postcodes. Two came from

UK institution, and represents the views of leaders and policy surrounding counties of Hertfordshire and Surrey. Three came from further

influencers within the field of healthcare. As such it provided a north in England: Nottingham, Sheffield, and Newcastle.

convenient starting point to develop further research into the One had training and experience in an EU country before becoming a

subject. The paper also proposed that the business angle of dentist in a high-needs area of London. Larger practices indicate they had

healthcare, neglected by research on professionalism in medicine five or more surgeries within the practice.

in the UK context, needed to be examined in light of the way An overview of respondents’ details is presented in Table 1.

dental care is organised in the UK, with co-payments and a mix of

private and NHS practice. This is of particular relevance if, as Welie

suggests, dentistry as a profession and as a business are not RESULTS

commensurate [26]. The results presented here reflect the responses of working dental

The Royal College of Physicians (RCP) list provided a way to professionals to the RCP character traits defined as comprising

initiate a discussion and allowed us to explore the extent to which professionalism within a healthcare setting. The traits were

the discourse of organisations, and the character trait lists that integrity, compassion, excellence, reliability, altruism, continuous

emerge from them, correlate to the ways dentists understand and improvement, and working with the health team. Each trait was

enact professionalism in practice [27]. Taking this as a starting presented within the interview and participants were asked what

point, this paper presents the findings from a qualitative study the term meant to them and how and if it was relevant to their

exploring dentists’ understanding of these character traits. These practice. Each term is taken in turn below and the views of

findings form a single strand of a far more expansive grounded participants are illustrated with quotes. Quotes are attributed as:

theory study which aimed to answer the research question, what respondent designation/male or female/workplace setting/tran-

does dental professionalism mean in practice? scription line number (e.g., G1f/NHS/l.100).

Integrity

METHOD There was some uncertainty around the word integrity and its

Constructivist grounded theory (CGT) [28] was employed to conduct and meaning. Most were familiar with the term, but some were either

analyse qualitative, depth interviews with dental professionals in England. unsure about its exact meaning or how to interpret it in the light

A stratified sample of dental professionals practising around London and of professionalism. All of the participants who were comfortable

the north of England were approached to participate in one-to-one with the term saw it as a character trait. For some this was related

interviews by email. All interview participants worked within the UK dental predominantly to trust and honesty:

system, a cross section of National Health Service (NHS) primary and

secondary care and private practice.

The initial phase of sampling purposively aimed to vary role, practice

You need professional integrity because you need your patients to

type (NHS/Private), and patient demographics to represent the different completely trust in you. I guess your whole character is a build-up

contexts in which dentistry is delivered. Theoretical sampling was of this. From your appearance to the way you talk, your accent,

employed for later interviews to ensure saturation of categories and everything is really, will support integrity (G18m/NHS/l.179−185)

develop the emergent theory [29, 30]. Three significant phases of

theoretical sampling involved firstly dentists and dental care professionals Alongside trust, the term honesty repeatedly occurred when

(DCPs) to explore and contrast perspectives, before refocusing towards participants tried to explain how they understood integrity,

BDJ Open (2022)8:21

A. Trathen et al.

3

Whilst no informants considered integrity to be a bad thing

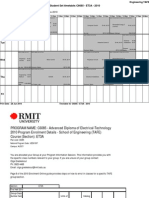

Table 1. Respondent characteristics.

per se, there were varying views about its relevance to

Respondent Gender Career stage Position professionalism or to dentistry.

designation

D1 F Mid DCP It’s not the utmost thing I would say is the key thing for a dentist

to be. (G3m/NHS/l.116−118)

D2 M Late DCP

S1 M Late Secondary care I would say it’s important I would not say it’s the most important,

S2 M Early Secondary care but I do think it’s important…I’ve heard it used, but not really

G1 F Early NHS that much in dentistry I guess. (G16f/NHS/l.109−116)

G2 M Early NHS

What is clear from this is that there is some confusion about

G3 M Late NHS what integrity means and how it might apply to dental practice.

G4 M Mid NHS The implication of this is that if ‘integrity’ is a social or regulatory

G5 M Mid NHS demand, its interpretation in practice is unlikely to be consistent

or straightforward.

G6 M Mid Private

G7 M Mid Private Compassion

G8 F Mid Private There was a broad, shared understanding of the term compassion.

G9 F Early NHS Views on its applicability to dentistry were varied, however,

ranging from a suspicion that it was too strong a word to apply to

G10 M Early Private

dental practice, to a belief that a dentist would be in the wrong

G11 F Mid Private job if they did not have it.

G12 F Late NHS Pain was frequently mentioned when discussing the need for

G13 F Mid NHS compassion. This involved the importance of recognising the pain

that somebody else is in, and seeking to alleviate it, and tied

G14 M Mid Private

compassion to empathy.

G15 M Mid NHS

G16 F Early NHS If a patient comes in in pain or if a patient comes in that is upset

G17 F Mid Private with the work that you’ve done or something like that, you need

to be compassionate in putting their feelings and their situation

G18 M Early NHS

first before yourself. (G10m/private/l.963−968)

G19 F Early NHS/medic

G20 M Early NHS This was also perceived as potentially problematic by some

D dental care professional; S Secondary care; G general dental practitioner. participants because it added complexity to the issue of

discussing fees; there were several ethical factors pulling in

and in many cases, the terms appeared to be almost different directions when navigating such situations.

synonymous. Descriptions such as ‘transparent’, ‘reputation’

and ‘being a person of their word’ were used to describe The difficult point actually on that one is when a patient comes in

integrity in this way. with raging toothache and all they want is for you to take away

For other participants integrity was related to being reliable; their pain and there is something that’s very uncomfortable

doing what you say you will do, sticking to your values. In the about talking money before taking away their pain. Because it

words of one participant: sounds like well if you give me this much money, I’ll take away

your pain. Whereas actually the reality is you’re going to take

away their pain and sometimes in that situation you almost have

being true to yourself… and your values (G8f/private/l.775). a kind of feel your way about whether they can accept your fees

and you usually end up under-charging them if you don’t think

She also pointed out that to have integrity the values you stand they can because you have to get rid of the pain first. (G11f/

by should be good, and that may not necessarily be so. private/l.425−447)

…you could have really bad values and be true to them wouldn’t This is a clear example of the divergence between medicine and

you and you could be a scoundrel so yes no. (G8f/private/l.778) dentistry in the UK context, with the co-payment element of

dentistry requiring conversations about money which do not

Two respondents provided examples to illustrate their percep- routinely take place in medicine. The outcome of this was that,

tion of integrity as ‘doing what is best for your patient’. In the whilst compassion itself was seen as a virtue, when considered in

context of private practice, they used examples where choices the context of professionalism many participants felt that it could

could be made in clinical situations that would all be reasonable. have a detrimental effect if taken too far, for both dentist and

They felt that where one option would be financially more patient.

rewarding, choosing the other when they felt it best was a good

example of integrity. There appeared to be competing demands You need a degree of compassion, but I think some people can

on the respondents’ decision making. get a bit over the top… it’s a fine balance I think.” (G2m/NHS/

l.321−325)

Let’s say you need a crown … shall we go for white crown or gold

crown or something like that. Now I might get more money if I Another respondent felt that compassion was too strong a word

get a white crown off you but it’s my obligation to you to say for dentistry, and that empathy was better. She felt that this

gold is the best material… give you all the information to not do implied being able to consider other people’s feelings without

that (G10m/private/l.548−556) becoming too drawn into their circumstances.

BDJ Open (2022)8:21

A. Trathen et al.

4

Altruism They’re like, Mr X never did that. They love him. They’re not upset

Altruism proved to be one of the least well-understood terms with me, they’re almost intrigued. They’re like, “oh what’s she

amongst participants in this study. In interviews where they were going to do next?” (G9f/NHS/l.1095−1100)

unfamiliar with the word, altruism was explained as ‘putting the

needs of others before your own’. Generally, the examples given She suggested that patients were quite forgiving of their old

were things such as staying later to help emergency patients or dentist, suggesting that their relationship with him was more

making an extra call to a colleague to double check a patient is important than the technical aspects of the examination they

being managed well. received.

Some people felt that altruism meant doing something for no

reward, which was not considered appropriate. Participants …he’s actually almost become a permanent member of their

expected to be ‘paid properly’ for what they do. extended family and they love him even though deep down, they

don’t think he’s probably kept up with [contemporary dental care]

I obviously believe that professionalism should be paid properly, … well, they still think he’s professional. (G9f/NHS/l.1095−1100)

and the word ‘altruism’ is more doing it without any rewards. I do

believe that it should be rewarded, but yeah, I agree with the There is an irony that the one term that was uncontroversial to

word altruism, yeah. (G3m/NHS/l.66−71) dentists (despite different understandings and degree of per-

ceived importance) was perhaps less important to patients than

This led to accounts, as above, where answers were contra- some of the other traits that had little consensus.

dictory, suggesting a discordance between actual beliefs and what

participants felt they ‘should’ say. When it was put to people that Excellence

one possible form of altruism would be to lower fees for patients, The idea or trait of excellence created some confusion. Much of

the consensus was that this was not something that should be this stemmed from the perceived logical inconsistency of using

expected of a dentist. It was repeatedly explained that dentists this term as a professional attribute, as well as questions over what

have to make money and run successful businesses. precisely excellence was supposed to cover and what it might

look like. One participant responded to the use of the term with a

And it’s a business at the end of the day […], we all run a barrage of questions seeking to clarify what exactly was being

business and that, I suppose is an individual thing. (G10m/ referring to.

private/l.994−1004)

You can’t measure it. Having excellent habits would lead … does

Building on this, the idea that working in the NHS is ‘charity’, it lead to excellence? What is excellence? It’s outstanding, isn’t it

and thus altruistic, emerged repeatedly in the accounts of … how can you all be outstanding? Kind of a contradiction …

participants. We all have to have a minimum level of excellence. Is it excellent

to pass exams? (G9f/NHS/l.1233−1241)

I mean, to be honest I would think that the NHS is a bit of

altruism […] Because I would say that the NHS doesn’t financially If excellence is taken as a superlative it was noted that it would

benefit dentists as much as private healthcare does. (G20m/NHS/ then, by definition, be impossible for everyone to reach an

l.349−354) excellent standard; excellence implies being better than average.

Thus, a more pragmatic attitude was thought to be acceptance

This idea is repeated almost exactly by another respondent. that an average dentist will be average, but that they should

aspire to excellence and work towards it, making efforts to

Well, the NHS system […] sometimes you are having to do more continually improve and avoid stagnating.

work than probably you are paid for I guess so sometimes that’s

when I’d probably use that word altruistic because that’s when If the dentist doing the work strives to make it excellent then I

you’re putting the needs of others before your own, so that is think that’s sort of really the major part (G3m/NHS/l.364−367)

where I’d probably apply that word. (G16f/NHS/l.219−228)

Many respondents felt that excellence was an ‘ideal’ or

Again, this raises interesting points of divergence between something that was ‘aspirational’ rather than a required endpoint

dentistry and medicine around the roles of business and for all, thus making the inclusion of excellence in the definition of

remuneration in the delivery of care. professionalism problematic without some kind of clarification.

Continuous improvement Partnership with the healthcare team

Of all the characteristics discussed, the only one to have consistent ‘Partnership with the healthcare team,’ needed further clarification

agreement was the concept of continuous improvement. No for nearly every interview. Even when clarification was provided,

clarifications were asked for and there was agreement that it is however, there was disagreement about what a ‘good’ partnership

important. Variation came in how the respondents felt it should be would look like. Participants tended not to assess the appro-

put into practice. priateness of the words themselves, but rather discussed

Change was an important theme that emerged when discussing experiences of working with others. For some, an emphasis on

continuous improvement. Some examples were given of older leadership and hierarchy emerged; for others, they described the

dentists who had not kept up with contemporary issues, which importance of collaboration and non-hierarchal relationships. For

was seen as a problem. some, interpersonal relationships were most important.

I think at the very least pick up dental update [a dental Reliability

magazine] come on. It costs 80 pound a year. (G2m/NHS/l.583 Finally, all respondents felt that reliability was an important part of

−589) professionalism, but some suggested it was less important than

other traits.

One participant described how she took over from another

dentist who tended not to do things she considered fairly basic. She …to a certain extent you of course need a bit of reliability, you

described the surprise of the patients at the changes she made. can’t just not be there when you say you will be there and things

BDJ Open (2022)8:21

A. Trathen et al.

5

like that for patients. On the other hand, I wouldn’t say that if Although we are not suggesting that the respondents are

you’re not reliable then you’re not professional. I don’t think that deliberately deconstructing these words with a literary precision,

comes in (G3m/NHS/l.647−654) the process of discussing the words in the semi-structured

interview format continually subverted the idea that these words

Again, reliability was understood in different ways with some are mutually intelligible, let alone agreed upon. Respondents were

participants relating it to personal behaviours such as punctuality only able to create meaning by incorporating them into an

and following through on your word, while others linked it solely experiential framework comprised of their working experiences,

to the consistency of one’s clinical work. beliefs, and worldviews—they constructed their own meanings.

What can clearly be seen from the responses to this list is that They each had their own social-professional constructs. And there

all but one trait is understood in a variety of, sometimes was much more variation than we anticipated.

contradictory, ways. In addition, the relative importance of the This process is recognisable through the paradigm of social

traits varies between participants. constructivism, the idea that knowledge and understanding for an

This has profound implications for discussions about profes- individual develops from their interactions with culture and

sional practice in a dental setting. It seems that an externally society. It is a foundational principle of the ‘constructivist’

imposed set of traits and behaviours is conceptually challenging grounded theory method used for the study.

to apply to real-world practice, because a shared framework of The limitations of the word-based, functionalist understanding

understanding and application does not appear to exist. of professionalism [37] emerged early in the research process, and

the insight began to explain why efforts to define professionalism

over years and decades have struggled. Words used to describe

DISCUSSION professionalism are not, and likely could not, be agreed upon to

As a grounded theory study, it is important to be clear on what make a conventional operational definition.

type of knowledge this research is and is not capable of providing Although the social-professional constructs of the respondents

us, and what sort of ‘reality’ we are trying to capture. Constructivist needed to be internally coherent (i.e., a person will need to avoid

grounded theory (CGT) was consciously selected with these the dissonance of conflicting beliefs/ideas), the constructs of any

epistemological and ontological questions in mind. two individuals are going to be different. The lived experiences

Ontologically, our presupposition is that when asking what that are drawn upon to create these constructs are always going

professionalism means in practice, the answer will not be to be unique.

something that exists independently from the mind; we can only Tackling our research question by trying to understand the

interpret the question by reference to the viewpoints of respondents’ social-professional constructs allowed us to develop

individuals. Epistemologically, the design of the study does not a much more far-reaching, context-based conception of what

seek to achieve a fully representative sample of these individuals professionalism means. This is the core of an explanatory

through geography, sample size etc; rather it followed the needs grounded theory that is capable of accounting for the lack of

of the emergent theory. Instead of attempting to acquire agreement observed around institutionally defined terms.

generalisable truths, it sought to create an explanatory framework One accepted limitation of this study is the use of a single

that more comprehensively elucidates certain elements of the definition provided by the Royal College of Physicians in 2005 [11].

social world, specifically, what dental professionalism means in However, there was a clear rationale for doing do. First, it is, as an

practice. ideal-archetype model, based on listed traits characteristic of the

The findings of this study demonstrate the limitations of using structural-functionalist definitions common to professionalism

solely word-based character traits to understand and define discourse in healthcare and the earlier sociology of the professions

professionalism within dentistry. Even words which superficially [37]. Second, it came from a UK institution and had national

seem uncontroversial elicited a wide range of, sometimes relevance. Third, it represented the contemporary views of leaders

opposing, views. and policy influencers within the field of healthcare at the time

A typical criticism levelled at the professionalism discourse is when we embarked on the research. Thus, in summary, we

the contention that the words used to mark out the character consider that it has provided a useful starting point to develop

traits are so vague and abstract that they are almost impossible to further research on this important subject for the dental context

disagree with [21]. But the findings suggest that this isn’t the case. [8].

There is disagreement, leading to a much more intractable Although it is merely the initial research findings, rather than

problem - even where there was a degree of shared under- the full grounded theory in this paper, the findings we present

standing of the traits, there was disagreement over whether the endorse concerns articulated by other authors who suggest the

words should be part of a definition of professionalism at all. For need for alternative approaches to the ‘immutable’ language used

example, participants did not just disagree on the meaning of the in the discourse of professionalism [38–40]. Our study raises the

term ‘altruism’, they also disagreed on whether such a concept is possibility that reaching a shared understanding may be

appropriate to the practice of dentistry. insurmountably difficult if that understanding is contextually

Part of this undoubtedly arises from a fundamental problem of and cognitively bounded.

creating shared intersubjective understanding of language. The

CGT method used for this study provides particularly useful insight

into the nature of this problem. CGT aims to get close to how CONCLUSION

respondents understand their social world. By presenting them A different approach to understanding and operationalising

with institutionally selected terms that are deemed to form professionalism is needed. One line of reasoning in the literature

professionalism, declared by fiat, we are forcing the participants to suggests that professionalism is not ‘an absolute but constructed in

make sense of words and ideas constructed by someone else. the interaction of individual and context’ [41]. Whilst researchers

When we discussed these words, participants had to deconstruct have moved discussion forwards and recognise the need for

them, in a literary sense. context [40, 42], we are still largely reliant on functionalist lists of

In literary criticism and philosophy, deconstruction unpicks character traits in discussions of professionalism that describe an

language that has been formulated into a closed configuration or ideal-archetype. These remain at the core of curricula designed to

is axiomatic, particularly when it concerns ideas that are purported teach future dentists what is expected of them as professionals.

to be absolute, fixed, and necessary [35, 36]. The institutional RCP However, understanding practitioners working outside of this

definition of professionalism fits these criteria. protected academic environment brings in to question how useful

BDJ Open (2022)8:21

A. Trathen et al.

6

this idealistic approach actually is, as it does not map neatly on to 30. Conlon C, Timonen V, Elliott-O’Dare C, O’Keeffe S, Foley G. Confused about

the varied and often surprising data we collected, and it does not theoretical sampling? Engaging theoretical sampling in diverse grounded theory

appear to reflect the lived realities of our respondents. studies. Qual. Health Res. 2020;30:947–59.

Complexity and context are key to developing a theory that is 31. Charmaz K. The power and potential of grounded theory. University of Leicester:

Medical Sociology Online; 2012.

useful, intellectual and practical for professionalism in healthcare

32. Gibson B, Hartman J. Rediscovering grounded theory. London: SAGE, 2014.

and dentistry [43]. Engaging with the social-professional con- 33. Foley G, Timonen V. Using grounded theory method to capture and analyze

structs which individuals rely on to understand their social world is health care experiences. Health Serv Res. 2015;50:1195–210.

one route to achieving this. 34. King N, Horrocks C. Interviews in qualitative research. London: SAGE, 2010.

35. Turner C. Deconstructing transitional justice. Law Crit. 2013;24:193–209.

36. Turner C. Jacques Derrida: Deconstruction. Critical Legal Thinking. 2016. Available

REFERENCES at: https://criticallegalthinking.com/2016/05/27/jacques-derrida-deconstruction

1. Inui TS. A Flag in the Wind: Educating for Professionalism in Medicine. (accessed 16 July 2020).

Washington, DC: Association of American Medical Colleges, 2003. 37. Saks M. Defining a profession: The role of knowledge and expertise. Professions

2. Zijlstra-Shaw S, Roberts TE, Robinson PG. Perceptions of professionalism in and Professionalism. 2012;2.

dentistry - a qualitative study. Br Dent J. 2013;215:e18. 38. Wear D, Nixon LL. Literary inquiry and professional development in medicine:

3. Dunning JM. Dentistry at the crossroads: a study of professionalism. Am J Public against abstractions. Perspect Biol Med. 2002;45:104–24.

Health 1982;72:651–2. 39. Wear D, Kuczewski MG. The professionalism movement: can we pause? Am J

4. American Board of Internal Medicine. Project professionalism. Philadelphia, PA: Bioeth. 2004;4:1–10.

American Board of Internal Medicine, 1995. 40. Wynia MK, Papadakis MA, Sullivan WM, Hafferty FW. More than a list of values

5. Swick HM. Toward a normative definition of medical professionalism. Acad Med. and desired behaviors: a foundational understanding of medical professionalism.

2000;75:612–6. Acad Med. 2014;89:712–4.

6. D’Cunha J. Professionalism in medicine: are we closer to unifying principles? 41. Castellani B, Hafferty FW. The complexities of medical professionalism. In Wear D,

Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2010;22:111–2. Aultman J M, (eds). Professionalism in medicine: critical perspectives: Springer,

7. Phillips R, Bazemore AW, Newton WP, Byyny R. Medical professionalism: a con- 2006. pp 3-23.

tract with society. Pharos. 2019:2–7. 42. Zijlstra-Shaw S, Roberts T, G Robinson P. Evaluation of an assessment system for

8. Trathen A, Gallagher JE. Dental professionalism: definitions and debate. Br Dent J. professionalism amongst dental students. Eur J Dent Educ. 2016;21:e89–e100.

2009;206:249–53. 43. Morrow G, Burford B, Rothwell C, Carter M, McLachlan J, Illing J. Professionalism in

9. Zijlstra-Shaw S, Robinson PG, Roberts T. Assessing professionalism within dental healthcare professionals. London: Health & Care Professions Council, 2014.

education; the need for a definition. Eur. J. Dent. Educ. 2011;15:1–9.

10. American Board of Internal Medicine Foundation, American College of

Physicians-American Society of Internal Medicine, European Federation of Inter- AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

nal Medicine. Medical professionalism in the new millennium: a physician charter. AT and JEG conceived the original project. AT supported by JEG and SS designed the

Ann Intern Med. 2002;136:243–6. research. AT conducted the fieldwork and undertook the analysis for his doctoral

11. Royal College of Physicians. Doctors in society: Medical professionalism in a research. JEG and SS advised on analysis and interpretation of the findings. AT

changing world. Report of a Working Party of the Royal College of Physicians of drafted the manuscript. All authors contributed to revision of the manuscript and

London. London: RCP, 2005. approved the final version.

12. American Dental Education Association. ADEA Statement on professionalism in

dental education. ADEA; 2009.

13. Hafferty F, Levinson D. Moving beyond nostalgia and motives: towards a complexity

science view of medical professionalism. Perspect Biol Med. 2008;51:599–615.

FUNDING

This research was funded in part by the Wellcome Trust [Grant Number 095886/Z/11/

14. Birden H, Glass N, Wilson I, Harrison M, Usherwood T, Nass D. Defining pro-

Z] which provided a Clinical Fellowship in Biomedical Ethics for Dr. Andrew Trathen

fessionalism in medical education: a systematic review. Med Teach. 2014;36:47–61.

(AT) to undertake this research.

15. Saks M. Professions and power: A review of theories of professions and power. In

Dent M, Bourgeault IL, Denis J-L, Kuhlmann E, (eds). The Routledge Companion to

the Professions and Professionalism. New York, NY: Routledge, 2016. 85–91.

16. Chandratilake M, McAleer S, Gibson J. Cultural similarities and differences in COMPETING INTERESTS

medical professionalism: a multi-region study. Med Educ. 2012;46:257–66. The authors declare no competing interests.

17. Haque M, Zulkifli Z, Haque SZ, Kamal ZM, Salam A, Bhagat V. et al. Professionalism

perspectives among medical students of a novel medical graduate school in

Malaysia. Adv Med Educ Pract.2016;7:407 ADDITIONAL INFORMATION

18. Jacob L, Ramachandran G. Professionalism in medical school. Quest Int J Med Correspondence and requests for materials should be addressed to Andrew Trathen.

Health Sci. 2019;2:13–5.

19. Masella RS. The hidden curriculum: value added in dental education. J Dent Educ. Reprints and permission information is available at http://www.nature.com/

2006;70:279–83. reprints

20. van Mook WN, de Grave WS, van Luijk SJ, O'Sullivan H, Wass V, Schuwirth LW.

et al. Training and learning professionalism in the medical school curriculum: Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims

current considerations. Eur J Intern Med.2009;20:e96–e100. in published maps and institutional affiliations.

21. Erde EL. Professionalism’s facets: ambiguity, ambivalence, and nostalgia. J Med

Philos. 2008;33:6–26.

22. Larson MS. The rise of professionalism: Monopolies of competence and sheltered

markets. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction, 2013. Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons

23. Abbott A. The system of professions: An essay on the division of expert labor. Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing,

Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1988. adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give

24. Macdonald KM. The sociology of the professions. London: SAGE, 1995. appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative

25. Holden ACL. Dentistry’s social contract and the loss of professionalism. Aust Dent Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party

J. 2017;62:79–83. material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless

26. Welie JV. Is dentistry a profession? Part 3. Future challenges. J Can Dent Assoc indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the

(Tor.) 2004;70:675–8. article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory

27. Shirley JL, Padgett SM. An analysis of the discourse of professionalism. In Wear D, regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly

Aultman J M, (eds). Professionalism in medicine: critical perspectives. Boston, MA: from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.

Springer, 2006. 25–41. org/licenses/by/4.0/.

28. Charmaz K. Constructing grounded theory. 2nd ed. London: SAGE, 2014.

29. Draucker CB, Martsolf DS, Ross R, Rusk TB. Theoretical sampling and category

development in grounded theory. Qual Health Res. 2007;17:1137–48. © Crown 2022

BDJ Open (2022)8:21

You might also like

- ASV PT30 Parts ManualDocument23 pagesASV PT30 Parts ManualTrevorNo ratings yet

- Fracture Toughness & FatigueDocument15 pagesFracture Toughness & FatigueFrancis Paulo Cruz100% (1)

- Chipman TransmissionLines TextDocument244 pagesChipman TransmissionLines TextMau Gar Ec83% (6)

- Adult & Continuing Professional Education Practices: Cpe Among Professional ProvidersFrom EverandAdult & Continuing Professional Education Practices: Cpe Among Professional ProvidersNo ratings yet

- Dissertation Report (268526)Document15 pagesDissertation Report (268526)jeree100% (1)

- Laghu Parashari Siddhanta Jyotish Vedic AstrologyDocument3 pagesLaghu Parashari Siddhanta Jyotish Vedic AstrologyEeranki Subrahmanya sarma(E.S.Rao)No ratings yet

- Business AgilityDocument40 pagesBusiness Agilityqtrang_1911No ratings yet

- Multidisciplinary Collaboration in Development of Individual Education PlansDocument22 pagesMultidisciplinary Collaboration in Development of Individual Education PlansSiti Nadiah Othman100% (1)

- Holden 2020Document3 pagesHolden 2020Chris MartinNo ratings yet

- 15 Teaching and Assessing Professionalism in The Indian ContextDocument8 pages15 Teaching and Assessing Professionalism in The Indian ContextSubianandNo ratings yet

- MorganDocument14 pagesMorganAlessandra MoraisNo ratings yet

- 566-Article Text-3893-1-10-20190228Document17 pages566-Article Text-3893-1-10-20190228Neha SharmaNo ratings yet

- Global LeadershipDocument8 pagesGlobal LeadershipKrishna septian D UNo ratings yet

- Interprofessional EducationDocument12 pagesInterprofessional EducationAida TantriNo ratings yet

- Adams 2020Document11 pagesAdams 2020ShaAngNo ratings yet

- Customer Engagement by Brodie Et Al.Document21 pagesCustomer Engagement by Brodie Et Al.Roedy Jr.No ratings yet

- Knowledge Restructuring Through Case Processing The Key 2020 Educational RDocument31 pagesKnowledge Restructuring Through Case Processing The Key 2020 Educational RYogeshNo ratings yet

- Review IPCP Blok 4.5 2021Document25 pagesReview IPCP Blok 4.5 2021alyaNo ratings yet

- NEBDN National Diploma Syllabus 2020 Website Version V2Document59 pagesNEBDN National Diploma Syllabus 2020 Website Version V2Third HarmonyNo ratings yet

- Ethical Considerations in Clinical Supervision: Components of Effective Clinical Supervision Across An Interprofessional TeamDocument13 pagesEthical Considerations in Clinical Supervision: Components of Effective Clinical Supervision Across An Interprofessional Teamapi-681819056No ratings yet

- An Assessment of Construction Professionals' Level of Compliance To Ethical Standards in The Nigerian Construction IndustryDocument20 pagesAn Assessment of Construction Professionals' Level of Compliance To Ethical Standards in The Nigerian Construction IndustryDavid MugaggaNo ratings yet

- Jox 002Document20 pagesJox 002aanya guptaNo ratings yet

- Discovering Professionalism Through Guided ReflectionDocument8 pagesDiscovering Professionalism Through Guided ReflectionArdya LucitaNo ratings yet

- Discovering Professionalism Through Guided Reflection (Medical Teacher 2006)Document9 pagesDiscovering Professionalism Through Guided Reflection (Medical Teacher 2006)amy.hartinNo ratings yet

- Development of Conceptual Bases of The Employee Life Cycle Within An OrganizationDocument14 pagesDevelopment of Conceptual Bases of The Employee Life Cycle Within An OrganizationMun MunNo ratings yet

- Professionalism in Healthcare Professionals: Research ReportDocument68 pagesProfessionalism in Healthcare Professionals: Research ReportSueNo ratings yet

- HR Strategic PlanDocument11 pagesHR Strategic PlanAbdul MalikNo ratings yet

- Soft Skills Hard Skills and Practice IdentityDocument6 pagesSoft Skills Hard Skills and Practice IdentitySarah GracyntiaNo ratings yet

- NURS FPX 6111 Assessment 1 Course Definition and Alignment TableDocument6 pagesNURS FPX 6111 Assessment 1 Course Definition and Alignment TableEmma WatsonNo ratings yet

- Assessment of Knowledge, Attitude and Practices Regarding Bioethics Among Students in Dental Institutes of PunjabDocument7 pagesAssessment of Knowledge, Attitude and Practices Regarding Bioethics Among Students in Dental Institutes of PunjabIJAR JOURNALNo ratings yet

- Admin,+18+ +7366 OJS+ +C+ +Dr+Gulmina+Saeed+OrakzaiDocument7 pagesAdmin,+18+ +7366 OJS+ +C+ +Dr+Gulmina+Saeed+OrakzaiTún Trần AnhNo ratings yet

- Leadership in Interprofessional Collaboration in Health CareDocument12 pagesLeadership in Interprofessional Collaboration in Health Careelwanelyas000No ratings yet

- Professionalism and Ethics - A Quantity Surveying PerspectiveDocument10 pagesProfessionalism and Ethics - A Quantity Surveying PerspectiveKarutama SelarasNo ratings yet

- Good Professional Practice For Biomedical ScientistsDocument6 pagesGood Professional Practice For Biomedical ScientistsErick InsuastiNo ratings yet

- Angust Et Al 2012Document12 pagesAngust Et Al 2012Sebastian WallotNo ratings yet

- AMEE Guide No 14 Outcome Based Education Part 5 From Competency To Meta Competency A Model For The Specification of Learning OutcomesDocument8 pagesAMEE Guide No 14 Outcome Based Education Part 5 From Competency To Meta Competency A Model For The Specification of Learning OutcomesHamad AlshabiNo ratings yet

- Interprofessional Education For Collaborative, Patient-Centred PracticeDocument7 pagesInterprofessional Education For Collaborative, Patient-Centred PracticeWahyu WijayantoNo ratings yet

- Chapter 21 - Future Directions of ODDocument4 pagesChapter 21 - Future Directions of ODAzael May PenaroyoNo ratings yet

- Dental Professionalism Defi Nitions andDocument5 pagesDental Professionalism Defi Nitions andP?TR�NJEI BOGDAN- ALEXANDRUNo ratings yet

- Research Methodology in Dentistry: Part I - The Essentials and Relevance of ResearchDocument8 pagesResearch Methodology in Dentistry: Part I - The Essentials and Relevance of ResearchRomNo ratings yet

- Beyond Rigour and Relevance: A Critical Realist Approach To Business EducationDocument15 pagesBeyond Rigour and Relevance: A Critical Realist Approach To Business EducationKhoulita CherifNo ratings yet

- Career Research Paper Draft 2Document2 pagesCareer Research Paper Draft 2shidlershotNo ratings yet

- A Best Evidence Systematic Review of Interprofessional Education BEME Guide No 9Document18 pagesA Best Evidence Systematic Review of Interprofessional Education BEME Guide No 9NAYITA_LUCERONo ratings yet

- Competency-Based Medical Education Implications FoDocument6 pagesCompetency-Based Medical Education Implications FoSubianandNo ratings yet

- A Conceptual Map of The Lean Nomenclature: Comparing Expert Classification To The Lean LiteratureDocument16 pagesA Conceptual Map of The Lean Nomenclature: Comparing Expert Classification To The Lean LiteratureMohammed SirelkhatimNo ratings yet

- Management Commitment To Service Quality and Service Recovery Performance: A Study of Frontline Employees in Public and Private HospitalsDocument21 pagesManagement Commitment To Service Quality and Service Recovery Performance: A Study of Frontline Employees in Public and Private HospitalsMentariNo ratings yet

- A Complex View of Professional Competence: Amanda - Torr@weltec - Ac.nzDocument16 pagesA Complex View of Professional Competence: Amanda - Torr@weltec - Ac.nzDEVINA GURRIAHNo ratings yet

- Group 9 Research IntroductionDocument4 pagesGroup 9 Research IntroductionEthan AbadNo ratings yet

- ELSEVIER - 40% The Ethics of Care and Wellbeing in Project Business From Instrumentality To RelationalityDocument6 pagesELSEVIER - 40% The Ethics of Care and Wellbeing in Project Business From Instrumentality To Relationalitydyah.yesica30No ratings yet

- The Value of Academic Research: Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly April 2003Document11 pagesThe Value of Academic Research: Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly April 2003WylieNo ratings yet

- Adverbios en Ingles 3Document6 pagesAdverbios en Ingles 3Carlos DNo ratings yet

- Maturity of PM - Cooke-DavisDocument8 pagesMaturity of PM - Cooke-DavisstringmainNo ratings yet

- Lean ServicesDocument23 pagesLean ServicesJawath BinaNo ratings yet

- How Do Business Model and Health Technology Design Influence EachotherDocument14 pagesHow Do Business Model and Health Technology Design Influence EachotherGopinath KrishnanNo ratings yet

- Australian Dental Journal Volume 59 Issue 42014 Doi 10Document8 pagesAustralian Dental Journal Volume 59 Issue 42014 Doi 10Shinta PurnamasariNo ratings yet

- Assignment Front SheetDocument6 pagesAssignment Front Sheethossain alviNo ratings yet

- Evaluating The Effectiveness of The On The Job Chapter 1 2 FinalDocument10 pagesEvaluating The Effectiveness of The On The Job Chapter 1 2 FinalApollo Simon T. TancincoNo ratings yet

- How To Write Articles That AreDocument6 pagesHow To Write Articles That Aretelto25No ratings yet

- What Is Professionalism in Occupational Therapy? A Concept AnalysisDocument14 pagesWhat Is Professionalism in Occupational Therapy? A Concept AnalysisNataliaNo ratings yet

- The Valueof Academic Research Piccoliand WagnerDocument11 pagesThe Valueof Academic Research Piccoliand Wagnerالمصرية للاعمال الكهربيةNo ratings yet

- Revision Sistematica Preparacion A La Practica Dental 2018Document9 pagesRevision Sistematica Preparacion A La Practica Dental 2018Chris MartinNo ratings yet

- Doctor Degree ThesisDocument10 pagesDoctor Degree Thesiswendyfoxdesmoines100% (2)

- Linking Environmental LCM and Knowledge Management: The Case of A Multinational CorporationDocument4 pagesLinking Environmental LCM and Knowledge Management: The Case of A Multinational CorporationJose SantosNo ratings yet

- Secrets to Success in Industry Careers: Essential Skills for Science and BusinessFrom EverandSecrets to Success in Industry Careers: Essential Skills for Science and BusinessNo ratings yet

- Materi Tambahan Hipersensitivitas DentinDocument73 pagesMateri Tambahan Hipersensitivitas DentinReza ChandraNo ratings yet

- RKG 5 Indah BayDocument3 pagesRKG 5 Indah BayReza ChandraNo ratings yet

- Cleft Lip and PlateDocument3 pagesCleft Lip and PlateReza ChandraNo ratings yet

- Present and Past Tense ExerciseDocument1 pagePresent and Past Tense ExerciseReza ChandraNo ratings yet

- Tugas Rkg-5 Anomali Gigi Dentinogenesis Imperfecta: Nama: Jessi Miranda NIM: 04031281621032Document3 pagesTugas Rkg-5 Anomali Gigi Dentinogenesis Imperfecta: Nama: Jessi Miranda NIM: 04031281621032Reza ChandraNo ratings yet

- Amelogenesis Imperfecta: Ovilia Andaresta Asrultania 04031181621015Document3 pagesAmelogenesis Imperfecta: Ovilia Andaresta Asrultania 04031181621015Reza ChandraNo ratings yet

- Interpretasi Lesi Osteoradionekrosis: NAMA: Saphira Pramudita NIM: 04031281621037Document3 pagesInterpretasi Lesi Osteoradionekrosis: NAMA: Saphira Pramudita NIM: 04031281621037Reza ChandraNo ratings yet

- Interpretasi Supernumerary Teeth Pada Dua Foto Radiografis PanoramikDocument3 pagesInterpretasi Supernumerary Teeth Pada Dua Foto Radiografis PanoramikReza ChandraNo ratings yet

- Dental Management in Patients With Antiplatelet Therapy: A Systematic ReviewDocument7 pagesDental Management in Patients With Antiplatelet Therapy: A Systematic ReviewReza ChandraNo ratings yet

- Macrodontia: Indah Pratiwi Bay 04031181621019Document3 pagesMacrodontia: Indah Pratiwi Bay 04031181621019Reza ChandraNo ratings yet

- IndianJOralSci7151-2459446 064954Document3 pagesIndianJOralSci7151-2459446 064954Reza ChandraNo ratings yet

- RKG PULP SCLEROSIS - Intan Mulia WulandariDocument3 pagesRKG PULP SCLEROSIS - Intan Mulia WulandariReza ChandraNo ratings yet

- Cleft Lip and PlateDocument3 pagesCleft Lip and PlateReza ChandraNo ratings yet

- Overseas Filipino WorkerDocument2 pagesOverseas Filipino WorkerMonica HermoNo ratings yet

- Download full chapter Java 8 Pocket Guide Instant Help For Java Programmers 1St Edition Liguori Robert Liguori Patricia pdf docxDocument53 pagesDownload full chapter Java 8 Pocket Guide Instant Help For Java Programmers 1St Edition Liguori Robert Liguori Patricia pdf docxmatthew.wise167No ratings yet

- 2908F W17 Outline KazmierskiDocument8 pages2908F W17 Outline KazmierskijoeNo ratings yet

- Main Switch - IsolatorDocument32 pagesMain Switch - IsolatorTú Nguyễn ĐứcNo ratings yet

- Guias de Inspeccion Cheyenne IIDocument23 pagesGuias de Inspeccion Cheyenne IIesedgar100% (1)

- Ba40-Ba80-Ba160 Anten RFI OmniDocument1 pageBa40-Ba80-Ba160 Anten RFI OmniBao Quoc MaiNo ratings yet

- QUARTER 4 W1 ENGLISH9 MELCS BASED DLL Complete Edited 6Document13 pagesQUARTER 4 W1 ENGLISH9 MELCS BASED DLL Complete Edited 6glorelyvc.moratalla22No ratings yet

- Transformer Models: An Introduction and CatalogDocument67 pagesTransformer Models: An Introduction and Catalogklaus peterNo ratings yet

- S-AV35A: ・ Power Gain: 35 dB (Min.) ・ Total Efficiency: 50% (Min.) ΩDocument6 pagesS-AV35A: ・ Power Gain: 35 dB (Min.) ・ Total Efficiency: 50% (Min.) Ωdjoko susantoNo ratings yet

- Verano Enero - San Marco - Sem (2-Exse)Document11 pagesVerano Enero - San Marco - Sem (2-Exse)Marco CarbajalNo ratings yet

- Science 7 DLPDocument6 pagesScience 7 DLPMary Apostol0% (1)

- Directives: (Text With EEA Relevance)Document32 pagesDirectives: (Text With EEA Relevance)CogerNo ratings yet

- Locating The CaribbeanDocument48 pagesLocating The CaribbeanNyoshi CaballeroNo ratings yet

- Single Phase Diode Rectifiers: Experiment 2Document12 pagesSingle Phase Diode Rectifiers: Experiment 2Noona MigleiNo ratings yet

- Global Commands: Company of Heroes Install CodeDocument20 pagesGlobal Commands: Company of Heroes Install CodeObed RegaladoNo ratings yet

- C6085 - Et3aDocument2 pagesC6085 - Et3aCu TiNo ratings yet

- 1902 - Rayleigh - On The Distillation of Binary MixturesDocument17 pages1902 - Rayleigh - On The Distillation of Binary MixturesmontoyazumaetaNo ratings yet

- Zeroth Law of Thermodynamics MCQ Quiz - Objective Question With Answer For Zeroth Law of Thermodynamics - Download Free PDFDocument34 pagesZeroth Law of Thermodynamics MCQ Quiz - Objective Question With Answer For Zeroth Law of Thermodynamics - Download Free PDFVinayak SavarkarNo ratings yet

- Modern Anaesthetic MachinesDocument4 pagesModern Anaesthetic MachinesSanj.etcNo ratings yet

- DLL - Q4 Week 2Document6 pagesDLL - Q4 Week 2Elizabeth AsuncionNo ratings yet

- C# Books, .NET Books, ASP - NET Books, VB - NET BooksDocument5 pagesC# Books, .NET Books, ASP - NET Books, VB - NET BooksSlavica ZivkovicNo ratings yet

- Siprotec 4 Und Siprotec Compact: Service Information FirmwareupdateDocument45 pagesSiprotec 4 Und Siprotec Compact: Service Information FirmwareupdateAbhishek RajputNo ratings yet

- Gambing, Chermae Shane Fe B. - Video Analysis On Taghoy Sa DilimDocument3 pagesGambing, Chermae Shane Fe B. - Video Analysis On Taghoy Sa DilimchermaeshanefegambingNo ratings yet

- Ultra Filling Spheres: by Beauty CreationsDocument8 pagesUltra Filling Spheres: by Beauty CreationsPel ArtNo ratings yet

- Assignment 1-1Document3 pagesAssignment 1-1muhaba AdegeNo ratings yet