Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Nwanguma 2013

Uploaded by

elhaririolayaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Nwanguma 2013

Uploaded by

elhaririolayaCopyright:

Available Formats

Journal of Human Nutrition and Dietetics

NUTRITIONAL SCIENCE

Salt (sodium chloride) content of retail samples of Nigerian

white bread: implications for the daily salt intake of

normotensive and hypertensive adults

B. C. Nwanguma & C. H. Okorie

University of Nigeria, Department of Biochemistry, Enugu State, Nigeria

Keywords Abstract

bread, hypertension, Nigeria, salt, sodium,

sodium chloride. Background: Bread has been identified as a major contributor to the exces-

sive salt (sodium chloride) intake of consumers in many countries, some of

Correspondence which have very high incidences of hypertension and related cardiovascular

B. C. Nwanguma, University of Nigeria, complications, such as stroke. This has prompted a global rise in interest in

Department of Biochemistry, Nsukka Campus,

the salt content of breads produced and consumed in many other countries.

Enugu State 410001, Nigeria.

Methods: The sodium contents of retail samples of 100 brands of Nigerian

Tel: +234-8063655062

E-mail: bennett.nwanguma@unn.edu.ng white bread were determined by photometry with a view to estimating the

relative contribution of bread to the recommended daily sodium intake of

How to cite this article both normotensive and hypertensive adults in the country.

Nwanguma B.C. & Okorie C.H. (2013) Salt Results: The salt content of the bread samples varied extensively, ranging

(sodium chloride) content of retail samples of from 0.51 g per 100 g (0.51%) to 1.8 g per 100 g (1.8%). The average salt

Nigerian white bread: implications for the daily content was 1.36 g per 100 g. Based on an estimated consumption of six

salt intake of normotensive and hypertensive

slices of bread (about 180 g) per meal of bread, this equates to a daily

adults. J Hum Nutr Diet. 26, 488–493

intake of between 0.99 g and 3.33 g of salt from bread alone. This repre-

doi:10.1111/jhn.12038

sents between 19.8% and 66.6% of the recommended daily allowance of 5 g

for normotensive adults, and between 24.75% and 83.25% of the recom-

mended daily allowance of 4 g for hypertensive adults.

Conclusions: The consumption of some brands of bread by normotensive

and hypertensive adults puts them at great risk of exceeding their recom-

mended daily allowance for salt. Thus, there is an urgent need to regulate

the amount of salt added to bread. In the interim, compelling bakers to

declare the salt content of their products on the packaging could help

consumers, especially hypertensive adults, avoid brands with a high salt

content.

Katan, 2004; WHO, 2008, 2011). Excessive salt intake has

Introduction

also been associated with increased risks of colon cancer

Salt (sodium chloride) is a major source of sodium in (Riboli & Norat, 2001; Hu et al., 2011), osteoporosis

human nutrition. Its intake in excess of physiological (Candarella et al., 2009) and kidney stones (Nouvenne

needs and above the recommended daily intake is a com- et al., 2010). Achieving population-wide reductions in salt

mon occurrence around the world (Elliot & Brown, intake is therefore an important public health priority in

2007), and is an important modifiable risk factor for many countries (Webster et al., 2011).

hypertension and related cardiovascular complications, Reducing the salt content of processed foods has been

such as stroke [World Health Organization (WHO), recognised as a feasible and more effective strategy for

2003; Yusuf et al., 2004], which presently account for a reducing daily salt intake than simply reducing the

very significant proportion of deaths as a result of non- amount of salt added during cooking or on the table

communicable diseases in many countries (Reddy & (WHO, 2007). This is based on the realisation that

ª 2013 The Authors

488 Journal of Human Nutrition and Dietetics ª 2013 The British Dietetic Association Ltd.

B. C. Nwanguma and C. H. Okorie Salt content of Nigerian white bread

processed foods are major contributors to the daily salt Services (HHS) & the US Department of Agriculture

intake of populations, with processed meat, bread and (USDA), 2005; Cotugna & Wolpert, 2011].

bakery products, dairy and cereal products often listed The present study aimed to determine the salt content

amongst the top five saltiest processed foods. (Webster of retail samples of white bread available in Nigeria, com-

et al., 2010; Ni Mhurchu et al., 2011; Woodward et al., prising a country of approximately 160 million people,

2012). Unfortunatley, consumers are often unaware of the where bread is a very popular food item on the breakfast

salt content of some of these processed foods that they menu. The results obtained from the study would help

consume regularly. This so-called ‘hidden salt’ has been predict the contribution of bread to the recommended

reported to contribute up to 95% of the salt intake of daily salt intake of Nigerians, which, at 9.6 g per day

some people, especially in countries where processed (Sanusi et al., 2011), far exceeds the average recom-

foods are widely consumed (Anderson et al., 2010). mended daily allowance (RDA) of less than 5.0 g per day

The unexpected inclusion in the list of very salty pro- (WHO, 2011). Further justification for the study comes

cessed foods is bread, a widely consumed food, whose from recent reports of relatively higher prevalence of

salt concentration is often not obvious from the taste. hypertension in South-Eastern Nigeria, where the present

Thus, unknown to many bread eaters, the concentration study was conducted (Ahaneku et al., 2011).

of salt found in bread often exceeds the recommended

benchmark. In a recent study of the sodium content of

Materials and methods

processed foods in UK, Ni Mhurchu et al. (2011)

reported sodium concentrations of up to 1200 mg per Collection and identification

100 g (equivalent to 3.0 g of salt per 100 g of bread) in Retail samples of 100 brands of white bread made from

some brands of bread. Thus, because of their popularity wheat flour, representing the major brands regularly sup-

with both children and adults, bread and other bakery plied to selected retail outlets were purchased from 10

products have been reported to contribute up to one- standard retail outlets in Nsukka and Enugu towns, both

quarter of the dietary salt intake in some countries in Enugu State in South-Eastern Nigeria, were used for

(Grimes et al., 2008, 2011; Ni Mhurchu et al., 2011; the present study. All samples were bought fresh within

Villani et al., 2012; Woodward et al., 2012). This realisa- 24 h of supply by the bakeries, and the salt content of

tion has now prompted many developed countries to each sample was determined within 24 h of purchase.

identify bread as an important target for population-wide Samples were assigned code sample numbers that identi-

salt reduction programmes (Girgis et al., 2003; WHO, fied both the brand and the retail point of purchase.

2010; Ferrante et al., 2011; Legowski & Legetic, 2011). A

salt concentration of 1.1 g per 100 g of bread (equivalent

Preparation of bread samples

to 440 mg of sodium per 100 g of bread) is the recom-

mended limit in Australia and New Zealand, whereas the The labelled bread samples were first dried in an oven set

Food Standards Agency of the UK recently set an even at a temperature of 60 °C for 24 h. Thereafter, test por-

lower salt limit of 1.0 g per 100 g of bread (the equiva- tions were subjected to dry digestion (ashing) using 25%

lent of 400 mg of sodium per 100 g of bread) as target HNO3 at a temperature of 450 °C.

for bakers to meet by August 2012 (Food Standards

Agency, 2011). Bread is now regularly included in the list

Determination of sodium

of salty processed foods in many countries (Webster

et al., 2010; Ni Mhurchu et al., 2011), and is extensively The sodium content of the ashed samples was determined

consumed as a snack or a formal meal in Nigeria (Emeje by flame photometry (Castenheira et al., 2009). The

et al., 2010). However, the subject of excessive salt con- sodium chloride equivalent was obtained by multiplying

tent of bread and its relative contribution to the daily salt the sodium concentration by 2.5. Estimates of salt intake

intake of consumers is yet to be recognised and given from bread were obtained by calculating the mean salt

appropriate attention as a public health issue in many content per slice of bread, and determining the average

countries, including Nigeria, despite reports of rising number of slices eaten by Nigerian adults per meal and,

incidences of hypertension and related cardiovascular thus, overall salt intake from bread.

complications. Consequently, bread eaters in Nigeria,

including those on prescribed low-salt diets, may inadver-

Results

tently continue to exceed the recommended daily salt

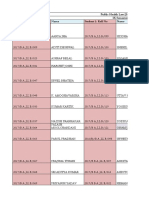

intake, which has been set at less than 5 g and 4 g for The results of the survey on the salt content of retail sam-

normotensive and hypertensive adults, respectively ples of bread are shown in Fig. 1. The lowest concentra-

[WHO, 2003; US Department of Health & Human tion of salt observed was 0.51 g per 100 g (equivalent of

ª 2013 The Authors

Journal of Human Nutrition and Dietetics ª 2013 The British Dietetic Association Ltd. 489

Salt content of Nigerian white bread B. C. Nwanguma and C. H. Okorie

mined average consumption of six slices of bread, with

each slice weighing 30 g. The estimated average intake

from the samples analysed range from 0.99 g from the

consumption of the samples in salt band A to 3.33 g

from the consumption of samples in salt band N.

Discussion

The salt content of bread is fast becoming an important

parameter for assessing the quality and safety of bread,

especially in countries such as the UK where upper limits

have been set for the amount of salt to be allowed in

bread (Food Standards Agency, 2011)

The salt content of the retail samples of white bread

Figure 1 Scatterplot of the salt content of retail samples of bread

(g per 100 g). analysed in the present study varied rather widely (Fig. 1),

ranging from as low as 0.51 g per 100 g (sodium equiva-

204 mg of sodium per 100 g of bread), whereas the high- lent = 204 mg per 100 g) to as high as 1.8 g per 100 g

est concentration was 1.8 g per 100 g (equivalent of (sodium equivalent = 720 mg per 100 g). Only 57% of

700 mg of sodium per 100 g of bread). The average salt the bread samples analysed fell below the limit of 1.0 g

concentration of the brands investigated was 1.36 g per per 100 g set recently by the Food Standards Agency.

100 g. This is equivalent to an average sodium concentra- Concentrations of salt comparable to the ones observed

tion of 0.544 g per 100 g of bread. Based on these values, in the present study have been reported in other

the brands were classified into 14 salt bands, ‘A’ to ‘N’, countries (Grimes et al., 2008). In addition, Ferrante

differing by 0.1 g of salt. et al. (2011) recently reported a much higher average salt

Only 57% of the breads sampled had salt contents concentration of 2.0 g per 100 g in breads consumed in

equal to or below the upper limit of 1.1 mg per 100 g Argentina, whereas Castanheira et al. (2009) also reported

recommended in many countries. The estimated salt values of up to 1.8 g per 100 g in Portuguese bread.

intakes from bread samples in the different salt bands are Although such high levels of salt are more likely to be

shown in Table 1. The calculations are based on predeter- found in countries with no legislation limiting the

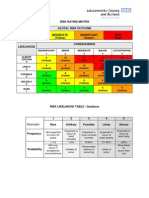

Table 1 The estimated salt content of bread and contribution to recommended daily intakes of normotensive and hypertensive adults

Percentage of Percentage of

Range of salt in Median salt content Average salt content Salt intake per salt RDA for salt RDA for

100 g of of breads in each per slice of bread meal of six normotensive hypertensive

Salt band bread (g) n band (g per 100 g) weighing 30 g (g)* slices (g) adults (%)† adults (%)‡

A 0.51–0.60 5 0.55 0.17 0.99 19.8 24.75

B 0.61–0.70 8 0.65 0.20 1.17 23.4 29.25

C 0.71–0.80 9 0.75 0.23 1.35 27.0 33.75

D 0.81–0.90 10 0.85 0.26 1.53 30.6 38.25

E 0.91–1.0 11 0.95 0.29 1.71 34.2 42.75

F 1.01–1.1 10 1.05 0.32 1.89 37.8 47.25

G 1.11–1.2 6 1.15 0.35 2.07 41.4 51.75

H 1.21–1.3 8 1.25 0.38 2.25 45.0 56.25

I 1.31–1.4 13 1.35 0.41 2.43 48.6 60.75

J 1.41–1.5 10 1.45 0.44 2.61 52.2 65.25

K 1.51–1.6 6 1.55 0.47 2.79 55.8 69.75

L 1.61–1.7 1 1.65 0.50 2.97 59.4 74.25

M 1.71–1.8 2 1.75 0.53 3.15 63.0 78.75

N 1.81–1.9 1 1.85 0.56 3.33 66.6 83.25

*Based on the median salt concentration in each salt band.

†

Based on a RDA of 5 g per day for normotensive adults.

‡

Based on a RDA of 4 g per day for hypertensive adults [US Department of Health & Human Services (HHS) & the US Department of Agriculture

(USDA), 2005; Cotugna & Wolpert, 2011].

RDA, recommended daily allowance.

ª 2013 The Authors

490 Journal of Human Nutrition and Dietetics ª 2013 The British Dietetic Association Ltd.

B. C. Nwanguma and C. H. Okorie Salt content of Nigerian white bread

amount of salt added to bread, comparable levels of salt parameters may not be affected drastically. For example,

could also be present in breads sold in countries such as Lynch et al. (2009) observed a decrease in the resistance

the UK and Australia where compliance with recom- of dough to extension but observed that no changes on

mended salt limits is voluntary (Dunford et al., 2011; Ni the structural properties of the bread occurred when the

Mhurchu et al., 2011). This is because, in the absence of salt concentration of dough was reduced from 1.2% to

mandatory legislations, bakers would prefer to add as 0.6% and 0.3%. In addition, the fact that the salt content

much salt as they consider necessary to achieve the dough of 57% of the bread samples analysed in the present study

of desired quality and, more importantly, satisfy the taste fell within the recommended limit implies that it is possi-

preferences of consumers. ble to produce bread with much lower concentrations.

Based on the concentration of salt present in the analy- The possibility of partially replacing sodium chloride

sed samples, the contribution of bread to the recom- with salts of potassium, magnesium and calcium, which

mended daily intake of salt varies from 0.99 g (for bread do not pose similar health risks as NaCl, as well as the

containing about 0.55 g of salt per 100 g of bread) to use of technology to enhance saltiness at the same time as

3.33 g (for bread containing 1.85 g of salt per 100 g of reducing the actual salt content of bread, has also been

bread). These values translate to 19.8% and 66.6% of the suggested (Charlton et al., 2007; Noort et al., 2010,

new salt RDA of 5 g per day for normotensive adults, 2011). This currently constitutes an important aspect of

respectively (Table 1). Similarly, these quantities of salt on-going research on the subject of salt reduction in

would amount to between 24.75% and 83.25% of the bread (Kaur et al., 2011).

RDA of salt for hypertensive adults, respectively. Even Considering the popularity of bread in Nigeria, and the

when the widely recommended concentration of 1.1 g of risk of exceeding the recommended daily intake for salt

salt per 100 g of bread is achieved, the salt consumption through the consumption of brands of bread with high

from six slices of bread weighing 30 g each would be salt content, a reduction in the salt content of bread

approximately 2 g. This equates to approximately 50% of would bring about the desired reduction in the the salt

the daily salt intake of 4 g recommended for hypertensive consumption of Nigerians. For any such salt-reduction

adults or adults aged >51 years. programme to succeed, compliance must be enforced in

Although the salt content of some brands of bread fell addition to compelling bread manufacturers to declare

well within the limit of 1.0 g per 100 g (in the UK) or the salt content of their products (Pietinen et al., 2007).

1.1 g per 100 g (in Australia), there is an urgent need to There will be need also to increase the awareness of peo-

reduce the amount of salt added to some of the brands. ple on the presence of ‘hidden salt’ in many processed

The approach currently advocated is a stepwise or foods, as well as the potential health benefits of reduced

gradual reduction, so that consumers who may already be salt intake (Ireland et al., 2010).

used to current salt levels in bread are not put off by the Because bread is easily the most widely consumed pro-

sudden change in taste or saltiness that would result from cessed food in Nigeria, producing breads with low salt

a drastic drop (Girgis et al., 2003; Henney et al., 2010). content would translate into a significant reduction in

Some countries, notably the UK and Australia, have population-wide consumption of salt (Cobiac et al., 2010;

already achieved significant reductions in the salt content He & Macgregor, 2010; He et al., 2010). Hopefully, this

of bread by this approach. Recent studies on the con- would result in a reduction of the incidence of hyperten-

sumer acceptance of low-salt bread have also demon- sion and related cardiovascular complications currently

strated that such gradual reductions can be accomplished associated with the consumption of salt in excess of the rec-

over a short period, while largely retaining consumer ommended daily amounts for the different population

acceptance (Girgis et al., 2003; Bolhuis et al., 2011; Ferr- groups.

ante et al., 2011). As expected, the implications of such

reductions on the nonsensory properties of bread have

also been the subject of on-going investigation. The salt Conflict of interest, source of funding and

added to dough serves essentially to control the fermenta- authorship

tion action of yeast, to strengthen the dough and to pro- The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

vide a uniform texture in the finished bread (Lynch et al., No specific funding was received from any funding

2009). In addition, salt serves as a preservative against organization towards the conduct of the studies.

microbial growth (Samapundo et al., 2010). These make

BCN and CHO contributed fully to the final design and

salt almost an indispensable ingredient in baking. Results

experimentation.

from studies already conducted on the possible conse-

Both authors critically reviewed the manuscript and

quences of such reductions on some of the desirable qual-

approved the final version submitted for publication.

ities of dough and bread demonstrate that these

ª 2013 The Authors

Journal of Human Nutrition and Dietetics ª 2013 The British Dietetic Association Ltd. 491

Salt content of Nigerian white bread B. C. Nwanguma and C. H. Okorie

Australian food products. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 43,

References

2219–2229.

Ahaneku, G.I., Osuji, C.U., Anisiuba, B.C., Ikeh, V.O., Grimes, C.A., Campbell, K.J., Riddell, L.J. & Nowson, C.A.

Oguejiofor, O.C. & Ahaneku, J.E. (2011) Evaluation of (2011) Sources of sodium in Australian children’s diets and

blood pressure and indices of obesity in a typical rural effect of the application of sodium targets to food products

community in eastern Nigeria. Ann. Afr. Med. 10, 120–126. to reduce sodium intake. Br J Nurr. 105, 468–477.

Anderson, C.A., Appel, L.J., Okuda N., B., I. J., C., Q., Z. & L., He, F.J. & Macgregor, G.A. (2010) Reducing salt intake

et al. (2010) Dietary sources of sodium in China, Japan, the worldwide: from evidence to implementation. Prog.

United Kingdom and the United States, women and men Cardiovasc. Dis. 52, 363–382.

aged 40–59 years: the INTERMAP study. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. He, F.J., Jenner, K.H. & Macgregor, G.A. (2010) WASH –

110, 736–745. World action on salt and health. Kidney Int. 78, 745–

Bolhuis, D.P., Temme, E.H., Koeman, F.T., Noort, M.W., 753.

Kremmer, S. & Jansse, A.M. (2011) A salt reduction of 50% Henney, J.E., Taylor, C.L. & Boon, C.S. (eds). (2010).

in bread does not decrease bread consumption or increase Strategies to Reduce Sodium Intake in the United States.

sodium intake by the choice of sandwich fillings. J. Nutr. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

141, 2249–2255. Hu, J., Vecchia, C., Morrison, H., Negri, E. & Mery, L. (2011)

Candarella, R., Vesani, F., Rizzoli, E. & Franucci, M. (2009) Salt, processed meat and the risk of cancer. Eur. J. Cancer

Salt intake, hypertension and osteoporosis. J. Endocrinol. Prev. 20, 132–139.

Invest. 32, 15–20. Ireland, D., Clifton, P.M. & Keogh, J.B. (2010) Achieving the

Castanheira, I., Figueiredo, C., Catarina, A., Coelho, I., Silva, salt intake target of 6 g per day in the current food supply

A.T., Santaiago, S., Fontes, T., Mota, C. & Calhau, M.A. in free-living adults using two dietary education strategies.

(2009) Sampling of bread for added sodium as determined J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 110, 763–767.

by flame photometry. Food Chem. 113, 621–628. Kaur, A., Bala, R., Singh, B. & Rehal, J. (2011) Effect of

Charlton, K.E., Macgregor, E., Vorster, N.H., Levitt, N.S. & replacement of sodium chloride with mineral salts in

Steyn, K. (2007) Partial replacement of NaCl can be rheological characteristics of wheat flour. Am. J. Food

achieved with potassium, magnesium and calcium salts in Technol. 6, 674–684.

brown bread. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 58, 508–521. Legowski, B. & Legetic, B. (2011) How three countries in the

Cobiac, L.J., Vos, T. & Veerman, J.L. (2010) Cost-effectiveness Americas are fortifying dietary salt reduction: a north and

of interventions to reduce dietary salt intake. Heart 96, south perspective. Health Policy 102, 26–33.

1920–1925. Lynch, E.J., Bello, F.D., Sheehan, E.M., Cashman, K.D. &

Cotugna, N. & Wolpert, S. (2011) Sodium recommendation Arendt, E.K. (2009) Fundamental studies on the reduction

for special populations and the resulting implication. of salt on dough and bread characteristics. Food Res. Int. 42,

J. Community Health 36, 874–882. 885–891.

Dunford, E.K., Eyles, H., Mhurchu, C.N., Webster, J.L. & Neal, Ni Mhurchu, C., Capelin, C., Dunford, E.K., Webster, J.L.,

B.C. (2011) Changes in the sodium content of bread in Neal, B.C. & Jebb, S.A. (2011) Sodium content of processed

Australia and New Zealand between 2007 and 2011: foods in the United Kingdom: analysis of 44,000 foods

implications for polcy. Med. J. Aust. 195, 346–349. purchased by 21,000 households. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 93, 594–

Elliot, P. & Brown, I. (2007) Sodium Intakes around the World. 600.

Geneva: WHO. Noort, M.W.J., Bult, J.H.F., Stieger, M. & Hamer, R.J. (2010)

Emeje, M.O., Ofoefule, S.I., Nnaji, A.C., Ofoefule, A.I. & Saltiness enhancement in bread by inhomogeneous spatial

Brwon, S.A. (2010) Assessment of bread safety in Nigeria: distribution of sodium chloride. J. Cereal Chemist. 52, 372–

quantitative determination of potassium bromated and lead. 386.

African J. Food Sc. 4, 394–397. Noort, M.W.J., Bult, J.H.F. & Stieger, M. (2011) Saltiness

Ferrante, D., Apro, N., Ferreira, V. & Virgolini, M. (2011) enhancement by taste contrast in bread prepared with

Feasibility of salt reduction in processed foods in Argentina. encapsulated salt. J. Cereal Sci. 55, 218–225.

Rev. Panam. Salud Publica 29, 69–75. Nouvenne, A., Meschi, T., Prati, B., Guerra, A., Allergi, F.,

Food Standards Agency. (2011) Reducing Salt in Bread. A Vezzoli, G., Soldati, L., Gambaro, G., Moggiore, U. &

Quick Guide for Craft Bakers. Available at: http://www.food. Borghi, L. (2010) Effects of a low-salt diet on idiopathic

gov.uk (accessed on 28 December 2011). hypercalciuria in calcium-oxalate stone formers: a 3-mo

Girgis, S., Neal, B., Prescott, J., Prendergast, J., Dumbrell, S., randomized controlled trial. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 91, 565–

Turner, C. & Woodward, M. (2003) A one-quarter 570.

reduction in the salt content of bread can be made without Pietinen, P., Valsta, L.M., Hirvonen, T. & Sinkko, H. (2007)

detection. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 57, 616–620. Labelling the salt content in foods: a useful tool in

Grimes, C.A., Nowson, C.A. & Lawrence, M. (2008) An reducing sodium intake in Finland. Public Health Nutr. 11,

evaluation of the reported sodium content of 335–340.

ª 2013 The Authors

492 Journal of Human Nutrition and Dietetics ª 2013 The British Dietetic Association Ltd.

B. C. Nwanguma and C. H. Okorie Salt content of Nigerian white bread

Reddy, K.S. & Katan, M.B. (2004) Diet, nutrition and the Webster, J.L., Dunford, E.K., Hawkes, C. & Neal, B.C. (2011)

prevention of hypertension and cardiovascular diseases. Salt reduction initiatives around the world. J. Hypertens.,

Public Health Nutr. 7, 167–186. 2011, 1043–1050.

Riboli, E. & Norat, T. (2001) Cancer prevention and World Health Organization. (2003) WHO Technical Report

diet: opportunities in Europe. Public Health Nutr. 4, Series. Diet, Nutrition and the Prevention of Chronic Disease.

475–484. Report of a Joint WHO/FAO Report Consultation 916.

Samapundo, S., Deschuffeleer, N., Van-Laere, D., De-Leyn, Geneva: World Health Organization.

I. & Devleghere, F. (2010) Effect of NaCl reduction and World Health Organization. (2004) The Global Burden of

replacement on the growth of fungi important to the Disease. 2004 Update. Geneva: World Health Organization.

spoilage of bread. Food Microbiol. 27:749–756. World Health Organization. (2007) The Effectiveness and Costs

Sanusi, R.A., Clafos, L.E., Ketiku, A.O., Akinlade, K.S., Kuti, of Population Interventions to Reduce Salt Consumption.

M., Oduwole, O.O. & Onyeaghala, A.A. (2005) Dietary salt Geneva: World Health Organization.

intakes in adult Nigerians using 24-h sodium excretion World Health Organization. (2010) Creating the Enabling

method. Eur. J. Scientific Research 6, 5–11. Environment for Population-Based Salt Reduction Strategies.

US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) and the Geneva: World Health Organization.

US Department of Agriculture (USDA). (2005) Dietary World Health Organization. (2011) Noncommunicable Diseases

Guideline for Americans, 6th edn. Washington, DC: US Country Profile 2011. Geneva: World Health Organization.

Government Printing Office. Woodward, E., Eyles, H. & Ni Mhurchu, C. (2012) Key

Villani, A.M., Clifton, P.M. & Keogh, J.B. (2012) Sodium intake opportunities for sodium reduction in New Zealand

and excretion in individuals with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a processed foods. Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health 36, 84–89.

cross-sectional analysis of overweight and obese males and Yusuf, S., Hawken, S., Ounpuu, S., Dans, T., Avezum, A., Lanas,

females in Australia. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 25, 120–139. F., McQueen, M., Budaj, A., Pais, P., Varigos, J. & Lisheng, L.

Webster, J., Dunford, E. & Neal, B. (2010) A systematic survey (2004) Effect of potentially modifiable risk factors associated

of the sodium contents of processed foods. Am. J. Clin. with myocardial infarction in 52 countries (the INTERHEART

Nutr. 91, 413–420. study): case–control study. Lancet 364, 937–952.

ª 2013 The Authors

Journal of Human Nutrition and Dietetics ª 2013 The British Dietetic Association Ltd. 493

You might also like

- Castanheira 2009Document8 pagesCastanheira 2009elhaririolayaNo ratings yet

- Salt Reduction Programme - Ireland 2003-2011Document13 pagesSalt Reduction Programme - Ireland 2003-2011api-589048135No ratings yet

- Sodium Content of Processed Foods in Brunei Darussalam: Zakaria Kamis, Roseyati Yaakub, Sok King Ong, Norhayati KassimDocument12 pagesSodium Content of Processed Foods in Brunei Darussalam: Zakaria Kamis, Roseyati Yaakub, Sok King Ong, Norhayati KassimAghniaNo ratings yet

- Salt Intake and Hypertension, 2014Document12 pagesSalt Intake and Hypertension, 2014Hanna NémethNo ratings yet

- Conroy2019 KornetDocument10 pagesConroy2019 KornetyooNa. hmdNo ratings yet

- Proposal 2017Document22 pagesProposal 2017Mercy MashaoNo ratings yet

- Geron Term PaperDocument11 pagesGeron Term PaperKit LaraNo ratings yet

- DurumDocument7 pagesDurumEsra MarpaungNo ratings yet

- AC Sal 2012Document7 pagesAC Sal 2012Genesis VelizNo ratings yet

- Is Too Much Salt Harmful? Yes: Pediatric Nephrology (2020) 35:1777-1785Document9 pagesIs Too Much Salt Harmful? Yes: Pediatric Nephrology (2020) 35:1777-1785Carolina RiveraNo ratings yet

- Salt Olderpopulation Factsheet FinalDocument2 pagesSalt Olderpopulation Factsheet FinalVette Angelikka Dela CruzNo ratings yet

- Project (Chapter 4 and 5 Corrected)Document80 pagesProject (Chapter 4 and 5 Corrected)Hannah AdejugbagbeNo ratings yet

- Innovative Food Science and Emerging Technologies: SciencedirectDocument10 pagesInnovative Food Science and Emerging Technologies: SciencedirectMayara FigueiredoNo ratings yet

- SodiumIntake 2Document13 pagesSodiumIntake 2Marisol MancillaNo ratings yet

- Maluly Et Al 2017-MSG As A Tool To Reduce Sodium in FoodstuffsDocument10 pagesMaluly Et Al 2017-MSG As A Tool To Reduce Sodium in FoodstuffsreyesfgrNo ratings yet

- Bahadoran 2016 - Nitrate and Nitrite Content of Vegetables Fruits Grains Legumes Dairy Products Meats and Processed MeatsDocument13 pagesBahadoran 2016 - Nitrate and Nitrite Content of Vegetables Fruits Grains Legumes Dairy Products Meats and Processed MeatsaenesiotoriNo ratings yet

- The Danish Investigation On Iodine Intake and Thyroid Disease, Danthyr: Status and PerspectivesDocument10 pagesThe Danish Investigation On Iodine Intake and Thyroid Disease, Danthyr: Status and PerspectivesErika Lisseth Saldarriaga GonzálezNo ratings yet

- Trends in Dietary Salt Sources in Japanese Adults Data From The 2007 2019 National Health and Nutrition SurveyDocument14 pagesTrends in Dietary Salt Sources in Japanese Adults Data From The 2007 2019 National Health and Nutrition SurveyatboreNo ratings yet

- Sugar and Health: A Food-Based Dietary Guideline For South AfricaDocument5 pagesSugar and Health: A Food-Based Dietary Guideline For South AfricaCristian OneaNo ratings yet

- Journal of Food Composition and Analysis: W. Becker, L. Jorhem, B. Sundstro M, K. Petersson GraweDocument9 pagesJournal of Food Composition and Analysis: W. Becker, L. Jorhem, B. Sundstro M, K. Petersson GraweJelmir AndradeNo ratings yet

- Assessment of Quantity of Salt Consumption Among Hypertensive Patients in A Rural Set Up of Thiruvallur DistrictDocument5 pagesAssessment of Quantity of Salt Consumption Among Hypertensive Patients in A Rural Set Up of Thiruvallur DistrictAnonymous izrFWiQNo ratings yet

- Wu 2019Document8 pagesWu 2019An PhanNo ratings yet

- 10.1007@978 3 030 11530 26Document21 pages10.1007@978 3 030 11530 26bellalaNo ratings yet

- Out 2Document7 pagesOut 2Elisa KartikaNo ratings yet

- Enhancing The Nutritional Value of Gluten-Free Cookies With InulinDocument5 pagesEnhancing The Nutritional Value of Gluten-Free Cookies With InulinRadwan AjoNo ratings yet

- Genetically Modified Foods Pathway To Food SecuritDocument6 pagesGenetically Modified Foods Pathway To Food SecuritSkittlessmannNo ratings yet

- SaltDocument4 pagesSaltMuna HassaneinNo ratings yet

- Hubungan Pola Makan Fast Food Dengan Kejadian Hipertensi Pada Usia Produktif Di Dusun Tegal Ngijon Sumber Agung Moyudan Sleman YogyakartaDocument12 pagesHubungan Pola Makan Fast Food Dengan Kejadian Hipertensi Pada Usia Produktif Di Dusun Tegal Ngijon Sumber Agung Moyudan Sleman YogyakartaNur AwaliaNo ratings yet

- Ajol File Journals - 414 - Articles - 230929 - Submission - Proof - 230929 4933 560464 1 10 20220831Document4 pagesAjol File Journals - 414 - Articles - 230929 - Submission - Proof - 230929 4933 560464 1 10 20220831elhaririolayaNo ratings yet

- Compara GuiasDocument17 pagesCompara GuiasMari BuôgoNo ratings yet

- The Ideal Okinawa Diet Cookbook; The Superb Diet Guide To Eating Like The World's Healthiest People For A Lifelong With Nutritious RecipesFrom EverandThe Ideal Okinawa Diet Cookbook; The Superb Diet Guide To Eating Like The World's Healthiest People For A Lifelong With Nutritious RecipesNo ratings yet

- Salt Intake Reduction Using Umami Substance Incorporated Food A Secondary Analysis of Nhanes 20172018 DataDocument8 pagesSalt Intake Reduction Using Umami Substance Incorporated Food A Secondary Analysis of Nhanes 20172018 DataChangle LiNo ratings yet

- 205 452 1 SMDocument10 pages205 452 1 SMRurin WidaNo ratings yet

- 532 East African Medical Journal: October 2003Document8 pages532 East African Medical Journal: October 2003Madhusudhana MvNo ratings yet

- A Study of Salt Content of Different Bread Types MDocument11 pagesA Study of Salt Content of Different Bread Types MelhaririolayaNo ratings yet

- 1975-Article Text-6120-1-10-20200701 PDFDocument9 pages1975-Article Text-6120-1-10-20200701 PDFMohamad Syu'ib SyaukatNo ratings yet

- Bacteriological Quality and Safety of Street Vended Foods in Delta State, NigeriaDocument6 pagesBacteriological Quality and Safety of Street Vended Foods in Delta State, NigeriaAlexander DeckerNo ratings yet

- The Nutrition Society - Global Trends in Added Sugars and Non Nutritive Sweetener Use in The Packaged Food SupplyDocument39 pagesThe Nutrition Society - Global Trends in Added Sugars and Non Nutritive Sweetener Use in The Packaged Food SupplyChalida HayulaniNo ratings yet

- Balan 2013Document7 pagesBalan 2013VAIDEHI ULAGANATHANNo ratings yet

- Association of Kidney Stone Disease With Dietary FactorsDocument10 pagesAssociation of Kidney Stone Disease With Dietary Factorsrashid nuñezNo ratings yet

- Prevalence and Risk Factors of Kidney Stone-ArticleDocument6 pagesPrevalence and Risk Factors of Kidney Stone-ArticleReesky Nanda Rockn'rollNo ratings yet

- Knowledge Attitude and Behavior Toward Dietary SalDocument8 pagesKnowledge Attitude and Behavior Toward Dietary SalLili Resta SeptianaNo ratings yet

- International Journal of Food Microbiology: A B A B C BDocument11 pagesInternational Journal of Food Microbiology: A B A B C Bmaraki998No ratings yet

- HIPERTENSIDocument10 pagesHIPERTENSIYulia Resi AndiniNo ratings yet

- The Sugar Controversy: Fernando Vio and Ricardo UauyDocument12 pagesThe Sugar Controversy: Fernando Vio and Ricardo UauyErika MaeNo ratings yet

- This Author's PDF Version Corresponds To The Article As It Appeared Upon Acceptance. Fully Formatted PDF Versions Will Be Made Available SoonDocument18 pagesThis Author's PDF Version Corresponds To The Article As It Appeared Upon Acceptance. Fully Formatted PDF Versions Will Be Made Available SoonmdmkiNo ratings yet

- Fast-Food Consumers in Singapore: Demographic Profile, Diet Quality and Weight StatusDocument9 pagesFast-Food Consumers in Singapore: Demographic Profile, Diet Quality and Weight StatusChynna CarlosNo ratings yet

- Accepted Manuscript: 10.1016/j.jcs.2016.10.010Document33 pagesAccepted Manuscript: 10.1016/j.jcs.2016.10.010anuNo ratings yet

- Knowledge, Attitudes and Practices of Food Hygiene Among Mobile Food Ven1ors in - 1Document17 pagesKnowledge, Attitudes and Practices of Food Hygiene Among Mobile Food Ven1ors in - 1Samson ArimatheaNo ratings yet

- Obesity, Nutrition, and Physical ActivityDocument16 pagesObesity, Nutrition, and Physical Activitymantopt6No ratings yet

- 10 1016@j Foodres 2017 10 039 PDFDocument24 pages10 1016@j Foodres 2017 10 039 PDFfranklinNo ratings yet

- Glycaemic Index and Glycaemic Load Values of Comme PDFDocument10 pagesGlycaemic Index and Glycaemic Load Values of Comme PDFcklconNo ratings yet

- Ajfn 3 3 167 175Document9 pagesAjfn 3 3 167 175M. YunusNo ratings yet

- Effects of Long-Term Consumption of High FructoseDocument7 pagesEffects of Long-Term Consumption of High FructoseVali[; x]No ratings yet

- Determination of Nitrate and Nitrite Levels in Infant Foods Marketed in Southern ItalyDocument7 pagesDetermination of Nitrate and Nitrite Levels in Infant Foods Marketed in Southern Italysamuel tralalaNo ratings yet

- The Role of Diet in The Management of Gout A Comparison of Knowledge and Attitudes To Current EvidenceDocument9 pagesThe Role of Diet in The Management of Gout A Comparison of Knowledge and Attitudes To Current Evidencedea anugerahNo ratings yet

- Jepretan Layar 2022-09-11 Pada 23.33.42 PDFDocument7 pagesJepretan Layar 2022-09-11 Pada 23.33.42 PDFAbdullah Nafi' ThohirNo ratings yet

- Development and Nutritional Assessment of Red Rice Oryza Longistaminata Based MuffinsDocument9 pagesDevelopment and Nutritional Assessment of Red Rice Oryza Longistaminata Based MuffinsEditor IJTSRDNo ratings yet

- The Relationship of Basic Conditioning Factors Knowledge Self-C .Document203 pagesThe Relationship of Basic Conditioning Factors Knowledge Self-C .MarjukiNo ratings yet

- Glycemic Index and Glycemic Load of Tropical Fruits and The Potential Risk For Chronic DiseasesDocument8 pagesGlycemic Index and Glycemic Load of Tropical Fruits and The Potential Risk For Chronic DiseasesDan NguyenNo ratings yet

- HUMSS - Disciplines and Ideas in The Social Sciences CGDocument1 pageHUMSS - Disciplines and Ideas in The Social Sciences CGDan LiwanagNo ratings yet

- Snake Bite SOPDocument5 pagesSnake Bite SOPRaza Muhammad SoomroNo ratings yet

- Vaccination BOON or BANEDocument5 pagesVaccination BOON or BANERushil BhandariNo ratings yet

- Different Committees in The HospitalDocument8 pagesDifferent Committees in The HospitalShehnaz SheikhNo ratings yet

- ELC - Assignment Cover SheetDocument4 pagesELC - Assignment Cover Sheetbharti guptaNo ratings yet

- Example of A NHS Risk Rating MatrixDocument2 pagesExample of A NHS Risk Rating MatrixRochady SetiantoNo ratings yet

- Blood and Tissue Flagellates BSCDocument27 pagesBlood and Tissue Flagellates BSCSisay FentaNo ratings yet

- Antibiotics ResistanceDocument8 pagesAntibiotics ResistanceboredtarteelNo ratings yet

- Synthesis PaperDocument7 pagesSynthesis Paperapi-379148533No ratings yet

- SR - Hse Officer (8104)Document5 pagesSR - Hse Officer (8104)Nijo Joseph100% (1)

- Typology of Nursing Problems in Family Nursing PracticeDocument4 pagesTypology of Nursing Problems in Family Nursing PracticeLeah Abdul KabibNo ratings yet

- TEACHER Healthy Diet American English Upper Intermediate Advanced GroupDocument4 pagesTEACHER Healthy Diet American English Upper Intermediate Advanced GroupMarcus SabiniNo ratings yet

- Nutritional Knowledge Among Malaysian ElderlyDocument12 pagesNutritional Knowledge Among Malaysian ElderlyNoor Khairul AzwanNo ratings yet

- Polytechnic of Health Denpasar Is An Institution of Higher Education Official of The Department of Health Which Is The Technical Implementation UnitDocument1 pagePolytechnic of Health Denpasar Is An Institution of Higher Education Official of The Department of Health Which Is The Technical Implementation UnitDewi PradnyaniNo ratings yet

- 5e-Schneider 2302 Chapter 7 MainDocument16 pages5e-Schneider 2302 Chapter 7 MainMeni GeorgopoulouNo ratings yet

- Fragility of MarriageDocument10 pagesFragility of MarriageMichelleNo ratings yet

- StressDocument4 pagesStressPinky Juntilla RuizNo ratings yet

- Company Name: Aims Industries LTDDocument40 pagesCompany Name: Aims Industries LTDkishoreNo ratings yet

- Clinical Leaflet - QUS - v2Document2 pagesClinical Leaflet - QUS - v2ultrasound tomNo ratings yet

- Topic ListDocument6 pagesTopic ListEdwinNo ratings yet

- Peran Perawat KomDocument27 pagesPeran Perawat Komwahyu febriantoNo ratings yet

- 2008 04 Lecture 1 Interface Dermatitis FrishbergDocument6 pages2008 04 Lecture 1 Interface Dermatitis FrishbergYudistra R ShafarlyNo ratings yet

- (Yabanci Dil Testi) : T.C. Millî Eğitim Bakanliği Ölçme, Değerlendirme Ve Sinav Hizmetleri Genel MüdürlüğüDocument22 pages(Yabanci Dil Testi) : T.C. Millî Eğitim Bakanliği Ölçme, Değerlendirme Ve Sinav Hizmetleri Genel Müdürlüğücem kayaNo ratings yet

- Teacher EducationDocument32 pagesTeacher Educationsoumya satheshNo ratings yet

- Musculoskeletal Clinical Translation FrameworkDocument1 pageMusculoskeletal Clinical Translation FrameworkRafaelNo ratings yet

- Test Bank For Health Psychology Biopsychosocial Interactions 9th Edition Edward P Sarafino Timothy W SmithDocument37 pagesTest Bank For Health Psychology Biopsychosocial Interactions 9th Edition Edward P Sarafino Timothy W Smithsequelundam6h17s100% (13)

- Written Assignment Principles of Applied RehabilitationDocument17 pagesWritten Assignment Principles of Applied RehabilitationRuqaiyah RahmanNo ratings yet

- Regional Victoria's RoadmapDocument12 pagesRegional Victoria's RoadmapTara CosoletoNo ratings yet

- Set C QP Eng Xii 23-24Document11 pagesSet C QP Eng Xii 23-24mafiajack21No ratings yet

- EFT GuideDocument11 pagesEFT Guidenokaion19% (26)