Professional Documents

Culture Documents

ca chủ tịch Schreber

Uploaded by

Anh MinhCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

ca chủ tịch Schreber

Uploaded by

Anh MinhCopyright:

Available Formats

Inside the Mind of Daniel Schreber

A look at Sigmund Freud's interpretation of Daniel Schreber's

fantasies detailed in Memoirs of My Nervous Illness.

One well known case examined by psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud was

that of Dr. Daniel Schreber (1842-1911), an ambitious German judge

who, as well as battling through numerous periods of illness, stood for

election and published his own case history as a book which would

become an influential talking point in psychology.

Although Freud’s published case histories were usually derived from

clients whom he saw at his own practise, he never treated Daniel

Schreber, and the two are not believed to have consulted one another

given that the latter’s symptoms would normally have led to

hospitalisation rather than consultations at a clinic such as that of Freud.

Instead, Freud read of his experience in his 1903 publication, Memoirs of

My Nervous Illness and published his own analysis of Schreber eight

years later in Notes upon an autobiographical account of a case of

paranoia (dementia paranoides) (1911). In the later publication, Freud

invoked his own ideas which would eventually form the basis of

the psychodynamic approach in psychology.

Daniel Paul Schreber was born in Leipzig, Germany in 1842, the second

of five children of Pauline and Daniel Gottlieb Moritz Schreber (1808-

1861), the latter being a renowned physician who would become the

director of a sanitorium in Leipzig in 1844. An intelligent man, he

followed his older brother, Gustav, into the legal profession, with both

brothers becoming judges.

Mental illness, however, troubled the family - Daniel’s brother would

eventually commit suicide in 1877, whilst his father suffered from long-

term depression prior to his death in 1861.

Daniel himself would suffer from mental illnesses on numerous occasions

throughout his life, leading to him being institutionalised for at least two

times.

Although Freud based his analysis primarily on Schreber’s second period

of illness, he also mentioned in his book a prior duration of illness. After

running as a candidate in the Reichstag elections of 1884, Schreber was

defeated - a result which he found difficult to accept. He sought help from

Paul Flechsig (1847-1929), a professor of psychiatry at the University of

Leipzig. After six months of treatment at Professor Flechsig’s clinic,

Schreber appeared to make a full recovery from a case of “hypochondria”

and consultations ended in 1885. Schreber’s second period of illness,

however, would see a return to the psychiatrist.

On October 1st, 1893, Schreber took up a new position as the Senate

president of an Oberlandesgericht court in Dresden. After receiving prior

notice of his new position, he had began to experience dreams in which

his initial problems would return.

Schreber recalled one memorable occasion on which he was laid in a

half-asleep state, when a thought came to him:

“after all it really must be very nice to be a woman

submitting to the act of copulation.” (Freud, 1911)1

Less than a month after beginning his new position at a Dresden court,

Schreber returned to Professor Flechsig complaining of “sleeplessness”.

Once with Flechsig, however, Schreber’s earlier hypochondria also

reemerged. He became over-sensitive to both light and audio stimulation,

whilst experiencing fantasies of a morbid nature, such as that he was

suffering from a plague. He would sit completely still for hours at a time

in a “hallucinatory stupor”, and described believing that he was able to

communicate directly with God, experiencing ideas of a religious nature,

such as a belief that he was hearing religious-themed music.

Schreber also expressed a belief that an onus was on him to save the

world, but that this could only be achieved by him being transformed into

a woman, creating a new population after being impregnated by God.

The persistence of his experiences led Schreber to attempt suicide by

various means, including trying to drown himself in a bath, but he failed.

He began to blame Professor Flechsig for his problems and referred to

him as a “soul murderer”.

Schreber was eventually moved between hospitals until he ended up in

Sonnenstein Castle, which served as an asylum at the time. His carers

noted a dualism to Schreber’s personality. On the one hand, he was able

to engage in polite conversation and possessed a keen intellect. At the

same time, however, he accepted his own fantasies.

Freud’s Views on Schreber

In an extensive critique of Schreber’s account of his illness, Freud noted

how religious themes permeated many of the man’s experiences - in

particular, his emasculation fantasy. Schreber was himself, Freud

recalled, not a particularly religious man, taking an agnostic view of

religious affairs. However, prior to his illness, he had begun to experience

religious doubts - unusual for a man who placed no great importance on

spiritual affairs. Freud asserted that his religious fantasies and a belief in

the need to be emasculated in order to save the world formed part of a

“redeemer delusion”, whereby a person feels that they have been assigned

a religious role of ‘redeemer’.

But why did Schreber feel the need to be turned into a woman?

Freud interpreted this desire as an “emasculation fantasy” which satisfied

Schreber’s innate “homosexual impulses”, citing the author’s claim to

have cross dressed privately in the past. The psychoanalyst believed that

these feelings extended towards his father and brother, but voices that

Schreber heard tauntingly calling him “Miss Schreber” may have

indicated a sense of guilt for experiencing these desires.

According to Freud’s psychodynamic theory, desires which a person feels

guilt for experiencing tend to be repressed, but remain in the

subconscious mind. These repressed desires surface as a “wish fantasy”

with ideas of emasculation, whereby Schreber’s homosexual desires are

fulfilled.

Freud also attached significance to the breakdown in patient-doctor

relationship between Schreber and his initial therapist, Professor Flechsig.

Why, asked Freud, had the patient turned against Flechsig during their

second set of consultations after the professor had helped him to recover

from his first period illness? Did Schreber also experience desires

towards Flechsig? Freud proposed that Schreber’s distrust towards the

professor was a result of transference - that his feelings towards a family

member had been transferred and directed towards Flechsig.

Freud described how transference occurred in two forms. Firstly, Flechsig

may have merely represented his older brother, Gustav, whom Freud

believed Schreber had experienced repressed feelings towards. His

accusation that Flechsig was a “soul murderer” was perhaps not then

directed towards the professor himself, but rather his brother.

As Schreber would have felt it to be unacceptable to express his repressed

feelings explicitly towards Flechsig, we see in his fantasy a desire to

copulate instead with a third party, God. However, Freud noted that the

uncommon attributes of God as described by Schreiber resembled his

impression of his father, and suggested a second occurrence of

transference between the two.

Schreber wrote Memoirs of My Nervous Illness in which he detailed his

experiences whilst in hospital, but remained in care until his release in

1902, and his book was published in 1902. However, following his

mother’s death in 1907, he was again confined to an asylum where he

would remain until his own death in 1911.1

You might also like

- Group Psychology and The Analysis of The Ego: Illustrated & Psychology Glossary & Index Added InsideFrom EverandGroup Psychology and The Analysis of The Ego: Illustrated & Psychology Glossary & Index Added InsideNo ratings yet

- The Legacies of Schreber and FreudDocument26 pagesThe Legacies of Schreber and Freudjimmi spendloveNo ratings yet

- Sigmund Freud: Inventor of the Modern MindFrom EverandSigmund Freud: Inventor of the Modern MindRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (7)

- Trastorno PersonalidadDocument14 pagesTrastorno PersonalidadAura LolaNo ratings yet

- Freud and RyleDocument44 pagesFreud and Rylerustie espiritu100% (1)

- FreudDocument19 pagesFreudjkmil100% (2)

- Schreber, Daniel Paul - Memoirs of My Nervous Illness (OCR)Document242 pagesSchreber, Daniel Paul - Memoirs of My Nervous Illness (OCR)johnsmithxx92% (12)

- Psycho-Analytic Notes on an Autobiographical Account of a Case of Paranoia (Dementia Paranoides)From EverandPsycho-Analytic Notes on an Autobiographical Account of a Case of Paranoia (Dementia Paranoides)No ratings yet

- Freud, Sigmund - Internet Encyclopedia of PhilosophyDocument19 pagesFreud, Sigmund - Internet Encyclopedia of PhilosophyozuluokeoluchukwuNo ratings yet

- Sigmund FreudDocument36 pagesSigmund FreudFrance Louie Jutiz100% (2)

- Sigmund Freud: Development of PsychoanalysisDocument3 pagesSigmund Freud: Development of PsychoanalysisRoibu Andrei ClaudiuNo ratings yet

- The Psychiatric Study of Jesus: Exposition and CriticismFrom EverandThe Psychiatric Study of Jesus: Exposition and CriticismRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Sigmund Freud 2Document4 pagesSigmund Freud 2carlo anganaNo ratings yet

- Beyond the Pleasure Principle (Barnes & Noble Library of Essential Reading)From EverandBeyond the Pleasure Principle (Barnes & Noble Library of Essential Reading)No ratings yet

- Biography of Sigmund FreudDocument5 pagesBiography of Sigmund FreudshairanicolecabuenasNo ratings yet

- Sigmund FreuddDocument14 pagesSigmund FreuddJoeyjr LoricaNo ratings yet

- Psychology ProjectDocument9 pagesPsychology Projectapi-466389950No ratings yet

- The Mother's Signature: A Journal of DreamsFrom EverandThe Mother's Signature: A Journal of DreamsRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Sigmund Freud: Navigation Search Freud (Disambiguation)Document19 pagesSigmund Freud: Navigation Search Freud (Disambiguation)sanda3k100% (1)

- Sigmund Freud TheoryDocument5 pagesSigmund Freud Theorykarthikeyan100% (1)

- William G. Niederland - The Schreber Case - Psychoanalytic Profile of A Paranoid Personality-Routledge (1984) PDFDocument197 pagesWilliam G. Niederland - The Schreber Case - Psychoanalytic Profile of A Paranoid Personality-Routledge (1984) PDFJackob MimixNo ratings yet

- Diss 1 3 7 OCR Rev PDFDocument5 pagesDiss 1 3 7 OCR Rev PDFKunotamashi KanakacheroNo ratings yet

- Adam Phillips Becoming Freud IntroDocument12 pagesAdam Phillips Becoming Freud IntroedifyingNo ratings yet

- Sigmund Freud (1856-1939) : Father of Psychoanalysis: Medicine in StampsDocument2 pagesSigmund Freud (1856-1939) : Father of Psychoanalysis: Medicine in StampsUlfi KhoiriyahNo ratings yet

- Biography of Sigmund FreudDocument2 pagesBiography of Sigmund Freudsladjana11No ratings yet

- Wilhelm ReichDocument12 pagesWilhelm Reichblahedu100% (1)

- 002Document16 pages002Carlos Patricio Ortega SuárezNo ratings yet

- Freud'S Analysis of A.B., A PSYCHOTIC MAN, 1925-1930Document16 pagesFreud'S Analysis of A.B., A PSYCHOTIC MAN, 1925-1930Iván AndreeNo ratings yet

- Locaylocay, James A. Btled 1-He Child Adolescent and Development October 5,2020Document3 pagesLocaylocay, James A. Btled 1-He Child Adolescent and Development October 5,2020James Arcenal LocaylocayNo ratings yet

- The Introduction of Sigmund FreudDocument7 pagesThe Introduction of Sigmund FreudDarwin Monticer ButanilanNo ratings yet

- Rashab and The PsychoanalystDocument31 pagesRashab and The PsychoanalystroadfiddlerNo ratings yet

- Psychodynamic TheoriesDocument76 pagesPsychodynamic TheoriesmaerucelNo ratings yet

- Sigmund FreudDocument39 pagesSigmund FreudHanis RazakNo ratings yet

- Abraham MaslowDocument14 pagesAbraham Maslowdusty kawiNo ratings yet

- Assignment 1Document11 pagesAssignment 1David EkpoNo ratings yet

- ReichDocument22 pagesReichDileep EdaraNo ratings yet

- Carl Jung: Early Life and CareerDocument9 pagesCarl Jung: Early Life and CareerReinhärt DräkkNo ratings yet

- The Interpretation of Dreams PDFDocument3 pagesThe Interpretation of Dreams PDFThiNo ratings yet

- Freud vs. HorneyDocument6 pagesFreud vs. Horneygag412100% (1)

- Attachment and SchizophreniaDocument5 pagesAttachment and SchizophreniaAntonio TariNo ratings yet

- New Microsoft Office Word DocumentDocument78 pagesNew Microsoft Office Word DocumentNivya GaneshNo ratings yet

- Dream PsychologyDocument127 pagesDream PsychologySebastian D. GhigoNo ratings yet

- Why Interesting?: Sigmund FreudDocument15 pagesWhy Interesting?: Sigmund FreudElaine ManongsongNo ratings yet

- Dr. Wilhelm Reich (March 24, 1897 - November 3, 1957)Document11 pagesDr. Wilhelm Reich (March 24, 1897 - November 3, 1957)Jared YairNo ratings yet

- Frankl Personality TheoryDocument17 pagesFrankl Personality TheoryAnthony SiNo ratings yet

- Freud Psychoanalytic TheoryDocument11 pagesFreud Psychoanalytic TheoryALONSO PANDANA100% (1)

- Sigmund Freud - Dream PsychologyDocument127 pagesSigmund Freud - Dream PsychologyIrisAnneNo ratings yet

- Freud: Dasar Bawah Sadar Dari Pikiran: C H A P T E RDocument41 pagesFreud: Dasar Bawah Sadar Dari Pikiran: C H A P T E REvan BastianNo ratings yet

- Sigmund Freud - Institute of PsychoanalysisDocument3 pagesSigmund Freud - Institute of PsychoanalysisozuluokeoluchukwuNo ratings yet

- Viktor Frankl: Dr. C. George BoereeDocument14 pagesViktor Frankl: Dr. C. George BoereeDaniel DragneNo ratings yet

- FreudDocument26 pagesFreudEmmanuel S. CaliwanNo ratings yet

- Psychoanalytic TheoryDocument25 pagesPsychoanalytic TheoryHamoda DibeNo ratings yet

- Freud's 'On Narcissism - An Introduction' - Philip CrockattDocument18 pagesFreud's 'On Narcissism - An Introduction' - Philip CrockattvgimbeNo ratings yet

- Ket-Reading 4aDocument3 pagesKet-Reading 4aAnh Minh100% (1)

- Ket - Reading 1Document6 pagesKet - Reading 1Anh MinhNo ratings yet

- Reading and Writing: PART 1. Choose The Correct AnswerDocument5 pagesReading and Writing: PART 1. Choose The Correct AnswerAnh MinhNo ratings yet

- Family 1 PICTURESDocument146 pagesFamily 1 PICTURESAnh MinhNo ratings yet

- Family 2 - PICTURESDocument175 pagesFamily 2 - PICTURESAnh MinhNo ratings yet

- Taper Lock BushesDocument4 pagesTaper Lock BushesGopi NathNo ratings yet

- Yamaha r6 Yec Kit ManualDocument2 pagesYamaha r6 Yec Kit ManualAlexander0% (1)

- Lec 8-10Document5 pagesLec 8-10osamamahmood333No ratings yet

- NDTDocument2 pagesNDTRoop Sathya kumarNo ratings yet

- Varaah KavachDocument7 pagesVaraah KavachBalagei Nagarajan100% (1)

- Column c4 From 3rd FloorDocument1 pageColumn c4 From 3rd Floor1man1bookNo ratings yet

- Daoyin Physical Calisthenics in The Internal Arts by Sifu Bob Robert Downey Lavericia CopelandDocument100 pagesDaoyin Physical Calisthenics in The Internal Arts by Sifu Bob Robert Downey Lavericia CopelandDragonfly HeilungNo ratings yet

- Texas Instruments FootprintsDocument7 pagesTexas Instruments FootprintsSteve SmithNo ratings yet

- 1 Name of Work:-Improvement of Epum Road (Northern Side) Connecting With Imphal-Saikul Road I/c Pucca DrainDocument1 page1 Name of Work:-Improvement of Epum Road (Northern Side) Connecting With Imphal-Saikul Road I/c Pucca DrainHemam PrasantaNo ratings yet

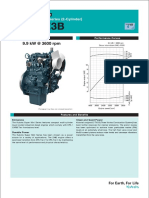

- z482 E3b en (3a2)Document2 pagesz482 E3b en (3a2)Gerencia General ServicesNo ratings yet

- Marriage HalldocxDocument50 pagesMarriage HalldocxBalaji Kamalakannan100% (2)

- Monthly Exam Part I Aurora English Course 1 (KD 1, KD2, PKD3)Document20 pagesMonthly Exam Part I Aurora English Course 1 (KD 1, KD2, PKD3)winda septiaraNo ratings yet

- Tim Ingold - From The Transmission of Representations To The Education of Attention PDFDocument26 pagesTim Ingold - From The Transmission of Representations To The Education of Attention PDFtomasfeza5210100% (1)

- Hygiene PassportDocument133 pagesHygiene PassportAsanga MalNo ratings yet

- Latihan Soal BlankDocument8 pagesLatihan Soal BlankDanbooNo ratings yet

- Over Current & Earth Fault RelayDocument2 pagesOver Current & Earth Fault RelayDave Chaudhury67% (6)

- Cateora2ce IM Ch012Document9 pagesCateora2ce IM Ch012Priya ShiniNo ratings yet

- Neuromuscular Diseases. ALSDocument7 pagesNeuromuscular Diseases. ALSjalan_zNo ratings yet

- Business Model Navigator Whitepaper - 2019Document9 pagesBusiness Model Navigator Whitepaper - 2019Zaw Ye HtikeNo ratings yet

- English 8 - B TR Và Nâng CaoDocument150 pagesEnglish 8 - B TR Và Nâng CaohhNo ratings yet

- Group Collaborative Activity TaskonomyDocument2 pagesGroup Collaborative Activity TaskonomyTweeky SaureNo ratings yet

- Deva Surya - 19MF02Document30 pagesDeva Surya - 19MF02SaravananNo ratings yet

- KZPOWER Perkins Stamford Genset Range CatalogueDocument2 pagesKZPOWER Perkins Stamford Genset Range CatalogueWiratama TambunanNo ratings yet

- BHLP Year Long Plan Required English Medium 2023 24 Batch Final 991676721629413Document3 pagesBHLP Year Long Plan Required English Medium 2023 24 Batch Final 991676721629413A V GamingNo ratings yet

- AC350 Specs UsDocument18 pagesAC350 Specs Uskloic1980100% (1)

- Nicotine From CigarettesDocument2 pagesNicotine From CigarettesAditya Agarwal100% (1)

- Data Sheet: W-Series WSI 6/LD 10-36V DC/ACDocument12 pagesData Sheet: W-Series WSI 6/LD 10-36V DC/ACLUIS FELIPE LIZCANO MARINNo ratings yet

- Sermo 13 de Tempore (2 Feb in Praes)Document1 pageSermo 13 de Tempore (2 Feb in Praes)GeorgesEdouardNo ratings yet

- Vol07 1 PDFDocument275 pagesVol07 1 PDFRurintana Nalendra WarnaNo ratings yet

- Age ProblemDocument31 pagesAge ProblemKenny CantilaNo ratings yet

- 12 Rules for Life by Jordan B. Peterson - Book Summary: An Antidote to ChaosFrom Everand12 Rules for Life by Jordan B. Peterson - Book Summary: An Antidote to ChaosRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (207)

- The Stoic Mindset: Living the Ten Principles of StoicismFrom EverandThe Stoic Mindset: Living the Ten Principles of StoicismRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (3)

- Summary: The Laws of Human Nature: by Robert Greene: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisFrom EverandSummary: The Laws of Human Nature: by Robert Greene: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (30)

- Stoicism: How to Use Stoic Philosophy to Find Inner Peace and HappinessFrom EverandStoicism: How to Use Stoic Philosophy to Find Inner Peace and HappinessRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (84)

- The Secret Teachings Of All Ages: AN ENCYCLOPEDIC OUTLINE OF MASONIC, HERMETIC, QABBALISTIC AND ROSICRUCIAN SYMBOLICAL PHILOSOPHYFrom EverandThe Secret Teachings Of All Ages: AN ENCYCLOPEDIC OUTLINE OF MASONIC, HERMETIC, QABBALISTIC AND ROSICRUCIAN SYMBOLICAL PHILOSOPHYRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (4)

- The Three Waves of Volunteers & The New EarthFrom EverandThe Three Waves of Volunteers & The New EarthRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (179)

- The Emperor's Handbook: A New Translation of The MeditationsFrom EverandThe Emperor's Handbook: A New Translation of The MeditationsRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (8)

- Stoicism The Art of Happiness: How the Stoic Philosophy Works, Living a Good Life, Finding Calm and Managing Your Emotions in a Turbulent World. New VersionFrom EverandStoicism The Art of Happiness: How the Stoic Philosophy Works, Living a Good Life, Finding Calm and Managing Your Emotions in a Turbulent World. New VersionRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (51)

- Summary: How to Know a Person: The Art of Seeing Others Deeply and Being Deeply Seen By David Brooks: Key Takeaways, Summary and AnalysisFrom EverandSummary: How to Know a Person: The Art of Seeing Others Deeply and Being Deeply Seen By David Brooks: Key Takeaways, Summary and AnalysisRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (4)

- How to Destroy America in Three Easy StepsFrom EverandHow to Destroy America in Three Easy StepsRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (21)

- How States Think: The Rationality of Foreign PolicyFrom EverandHow States Think: The Rationality of Foreign PolicyRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (7)

- The Authoritarian Moment: How the Left Weaponized America's Institutions Against DissentFrom EverandThe Authoritarian Moment: How the Left Weaponized America's Institutions Against DissentRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (17)

- It's Easier Than You Think: The Buddhist Way to HappinessFrom EverandIt's Easier Than You Think: The Buddhist Way to HappinessRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (60)

- Meditations, On the Shortness of Life, The Enchiridion of Epictetus: The Ultimate Stoicism CollectionFrom EverandMeditations, On the Shortness of Life, The Enchiridion of Epictetus: The Ultimate Stoicism CollectionRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (15)

- Why Buddhism is True: The Science and Philosophy of Meditation and EnlightenmentFrom EverandWhy Buddhism is True: The Science and Philosophy of Meditation and EnlightenmentRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (753)

- There Is a God: How the World's Most Notorious Atheist Changed His MindFrom EverandThere Is a God: How the World's Most Notorious Atheist Changed His MindRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (71)

- The Courage to Be Happy: Discover the Power of Positive Psychology and Choose Happiness Every DayFrom EverandThe Courage to Be Happy: Discover the Power of Positive Psychology and Choose Happiness Every DayRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (215)

- Summary of Man's Search for Meaning by Viktor E. FranklFrom EverandSummary of Man's Search for Meaning by Viktor E. FranklRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (101)

- You Are Not Special: And Other EncouragementsFrom EverandYou Are Not Special: And Other EncouragementsRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (6)

- A Short History of Modern Philosophy: From Descartes to WittgensteinFrom EverandA Short History of Modern Philosophy: From Descartes to WittgensteinRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (2)