Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Serum Amyloid A (SAA) Screening For General Health and Biosecurity

Uploaded by

mar.llisterriOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Serum Amyloid A (SAA) Screening For General Health and Biosecurity

Uploaded by

mar.llisterriCopyright:

Available Formats

Serum Amyloid A (SAA) Screening for

General Health and Biosecurity

Author: Siddra Hines, DVM, PhD, DACVIM-LA AUG

2020

Relevant Species

Routine equine health exams and

biosecurity strategies utilize screening

methods to detect underlying performance-

limiting issues and potential infectious

disease concerns. The fundamental basis

of this is a good physical exam with rectal

temperature screening, however subclinical

issues may still exist that can become

problematic. Measurement of serum amyloid A (SAA) is a highly effective tool for this purpose and

can identify horses with subclinical disease that would not otherwise be detected.

Any elevation of SAA should be considered abnormal

The normal range of SAA in a healthy horse is generally considered to be less than 20 µg/mL.1,2 It

becomes elevated in acute systemic inflammation, particularly due to viral or bacterial infections,

with bacteria stimulating the greatest SAA production.3-5 SAA is highly sensitive and specific for the

presence or absence of systemic inflammation, more sensitive than WBC count or fibrinogen.1,3,6-8

For the purpose of biosecurity or health screening, any elevation of SAA should be considered

abnormal and trigger further investigation.2,7

SAA may increase even if body temperature is normal

SAA can increase even in the absence of fever9-10, making it exceptionally useful for screening

purposes and to monitor health status. Unlike fever, it will not be significantly affected by NSAID

therapy.7 In one study, SAA was 97.1% sensitive and 97.2% specific to differentiate clinically

abnormal horses (i.e. those who developed infections) from those that were normal when tested

24 hours after air transportation.9 The presence of fever had a sensitivity of just 2.9% at the same

time point, indicating that SAA could identify brewing infections earlier and allow more rapid clinical

intervention.9

page 1 of 3 vmrd.com | Technical library

SAA testing can help prevent and manage infectious disease outbreaks

There is clear value in assessing SAA alongside rectal temperature to identify subclinical disease2,3,9

as part of an efficacious health screening strategy. In terms of biosecurity, disease outbreaks may

be prevented if horses are effectively screened prior to co-mingling at events or when introducing

new horses to a resident population. If an active infectious disease outbreak is occurring, SAA

can help monitor at-risk or exposed horses for development of disease. Horses that have become

infected will have elevated SAA and can be handled appropriately, with additional diagnostics as

indicated.3,4 SAA can also be used to monitor populations that may be at increased risk due to age,

stress, exposure, population density, or other factors.4,8 This could include young horses in intense

training4, hospital populations6, or horses undergoing long-distance travel9.

SAA can identify subclinical problems in outwardly healthy horses

As a general health screening tool, SAA can be very useful to assess the health of a horse prior to

surgery and to monitor for complications afterwards.3,10-12 Testing prior to transport may identify

subtle abnormalities that have the potential to develop into bigger problems with shipping. Testing

horses after transport3,9 allows early recognition of shipping-related infections. SAA screening can

help detect underlying issues during any routine health examination, including pre-purchase or

insurance exams. Although normal (negative) results do not rule out all concerns, a positive result

indicates an active problem that should be investigated.

Normal horses should have little to no SAA

As a general rule, a truly normal horse should have virtually no circulating SAA. SAA increases

minimally or not at all with stress, exercise13,14 or anesthesia4 alone. Barring any confounding factors

(see April 2020 newsletter), elevated SAA in an outwardly healthy horse should always be a trigger

to look deeper into possible causes.

REFERENCES

1

Witkowska- Piłaszewicz OD, Żmigrodzka M, Winnicka A, et al. Serum amyloid A in equine health

and disease. Equine Vet J 2019;51(3):293-298.

2

Radcliffe RM, Buchanan BR, Cook VL, et al. The clinical value of whole blood point-of-

care biomarkers in large animal emergency and critical care medicine. J Vet Emerg Crit Care

2015;25(1):138-151.

3

Jacobsen S, Andersen PH. The acute phase protein serum amyloid A (SAA) as a marker of

inflammation in horses. Equine Vet Educ 2007;19(1):38-46.

4

Pepys MB, Baltz ML, Tennet GA. Serum amyloid A protein (SAA) in horses: objective measurement

of the acute phase response. Equine Vet J 1989;21(2):106-109.

page 2 of 3 vmrd.com | Technical library

5

Hultén C, Demmers S. Serum amyloid A (SAA) as an aid in the management of infectious disease

in the foal: comparison with total leucocyte count, neutrophil count and fibrinogen. Equine Vet J

2002;34(7):693-698.

6

Belgrave RL, Dickey MM, Arheart KL. Assessment of serum amyloid A testing of horses and its

clinical application in a specialized equine practice. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2013;243(1):113-119

7

Hooijberg EH, van der Hoven R, Tichy A, et al. Diagnostic and predictive capability of routine

laboratory tests for the diagnosis and staging of equine inflammatory disease. J Vet Intern Med

2014;38:1587-1593.

8

Anhold H, Candon R, Chan Di-Sien, et al. A comparison of elevated blood parameter values in a

population of thoroughbred racehorses. J Equine Vet Sci 2014;34:651-655.

9

Oertly M, Gerber V, Anhold H, et al. The accuracy of serum amyloid A in determining early

inflammation in horses following long-distance transportation by air, in Proceedings. Am Assoc

Equine Pract 2017;63:460-461.

10

Jacobsen S, Jensen JC, Frei S, et al. Use of serum amyloid A and other acute phase reactants

to monitor the inflammatory response after castration in horses: a field study. Equine Vet J

2005;37(6):552-556.

11

De Cozar M, Sherlock C, Knowles E, et al. Serum amyloid A and plasma fibrinogen concentrations

in horses following emergency exploratory celiotomy. Equine Vet J 2020;52(1):59-66.

12

Aitken MR, Stefanovski D, Southwood LL. Serum amyloid A concentration in postoperative

colic horses and its association with postoperative complications. Vet Surg 2018; 1–9. https://doi.

org/10.1111/vsu.13133

13

Kristensen L. Buhl R, Nostell K, et al. Acute exercise does not induce an acute phase response

(APR) in Standardbred trotters. Can J Vet Res 2014;78(2):97-102.

14

Cywinska A, Witkowski L, Szarska E, et al. Serum amyloid A (SAA) concentration after training

sessions in Arabian race and endurance horses. BMC Vet Res 2013;9:91-97.

page 3 of 3 vmrd.com | Technical library

You might also like

- Robert W. Schrier - Atlas of Diseases of The Kidney Volume 01 PDFDocument316 pagesRobert W. Schrier - Atlas of Diseases of The Kidney Volume 01 PDFAtu Oana100% (3)

- EDUC-5420 - Week 1# Written AssignmentDocument7 pagesEDUC-5420 - Week 1# Written AssignmentShivaniNo ratings yet

- BackgroundDocument3 pagesBackgroundDrashtibahen PatelNo ratings yet

- Pearls of Glaucoma ManagementDocument576 pagesPearls of Glaucoma Managementrobeye100% (1)

- Improving Foal Care With Serum Amyloid A (SAA) Testing - V2-3Document2 pagesImproving Foal Care With Serum Amyloid A (SAA) Testing - V2-3mar.llisterriNo ratings yet

- Unexpected Results and Confounding Factors in Serum Amyloid A (SAA) TestingDocument2 pagesUnexpected Results and Confounding Factors in Serum Amyloid A (SAA) Testingmar.llisterriNo ratings yet

- SAA Colic v10 - 111120Document3 pagesSAA Colic v10 - 111120mar.llisterriNo ratings yet

- Blood Proteins and InflammationDocument13 pagesBlood Proteins and InflammationValentina SuescunNo ratings yet

- Comparison of Serum Amyloid A in Horses With Infectious and Non-Infectious Respiratory DiseasesDocument12 pagesComparison of Serum Amyloid A in Horses With Infectious and Non-Infectious Respiratory DiseasesMarjorie SalgadoNo ratings yet

- Bullone Et Al-2015-Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine PDFDocument5 pagesBullone Et Al-2015-Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine PDFRaul Zurdo Cori CocoNo ratings yet

- Paper ADocument7 pagesPaper AdeltanueveNo ratings yet

- Milk Testing in Small Ruminant Lentivirus Control Programs in GoatsDocument13 pagesMilk Testing in Small Ruminant Lentivirus Control Programs in GoatsJosé Hiram Sánchez GascaNo ratings yet

- 2.05.06 EiaDocument6 pages2.05.06 EiaWormInchNo ratings yet

- Bovine Leukosis Virus (BLV) On U.S. Dairy Operations, 2007: Veterinary ServicesDocument2 pagesBovine Leukosis Virus (BLV) On U.S. Dairy Operations, 2007: Veterinary ServicesMaria CappiNo ratings yet

- No Se Encuentra Asociación Entre El Huevo y Enfermedad Cardiovascular o Alteración de Lípidos o Mayor MortalidadDocument9 pagesNo Se Encuentra Asociación Entre El Huevo y Enfermedad Cardiovascular o Alteración de Lípidos o Mayor MortalidadFranco TormoNo ratings yet

- The Prevalence of Antibodies of Brucella Abortus Dermatophilus Congolensis and Bovine Leukaemia Virus in Nigerian Slaughter CattleDocument4 pagesThe Prevalence of Antibodies of Brucella Abortus Dermatophilus Congolensis and Bovine Leukaemia Virus in Nigerian Slaughter CattleGift MesaNo ratings yet

- Avances en Diagnóstico y Tratamiento en Caballos Con Cólico Agudo e Íleo PostquirúrgicoDocument16 pagesAvances en Diagnóstico y Tratamiento en Caballos Con Cólico Agudo e Íleo PostquirúrgicoValentinaJiménezNo ratings yet

- Lombard JDS 2020 AIPDocument14 pagesLombard JDS 2020 AIPRodolfo Córdoba R.No ratings yet

- HAI Guidelines 2010Document21 pagesHAI Guidelines 2010Mario Suarez MontalvoNo ratings yet

- Diagnostic Testing For Equine Endocrine DiseasesDocument12 pagesDiagnostic Testing For Equine Endocrine DiseasescarvalbienraizNo ratings yet

- Critical Care of The Colic Patient 2023 VepDocument19 pagesCritical Care of The Colic Patient 2023 VepAristoteles Esteban Cine VelazquezNo ratings yet

- Age-Sex Related in Hematological Values of Sandalwood Pony Horses (Equus Caballus) in East Sumba, NTTDocument7 pagesAge-Sex Related in Hematological Values of Sandalwood Pony Horses (Equus Caballus) in East Sumba, NTTmatius markusNo ratings yet

- The Consumption of Milk and Dairy Foods and The IncidenceDocument15 pagesThe Consumption of Milk and Dairy Foods and The IncidenceZNNo ratings yet

- Thrombophilia and Unexplained Pregnancy Loss in Indian PatientsDocument5 pagesThrombophilia and Unexplained Pregnancy Loss in Indian PatientsvenkayammaNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Milk Fever 3Document9 pagesJurnal Milk Fever 3darisNo ratings yet

- Who DiabetesDocument30 pagesWho DiabetesQueret OsoNo ratings yet

- The Role of Acute Phase Proteins in Diagnosis and ManagementDocument6 pagesThe Role of Acute Phase Proteins in Diagnosis and ManagementCabinet VeterinarNo ratings yet

- Serum Concentrations of Selected Proinflammatory Cytokines in Children With Alopecia AreataDocument7 pagesSerum Concentrations of Selected Proinflammatory Cytokines in Children With Alopecia AreataNurfadillah Putri Septiani PattinsonNo ratings yet

- Fetuin-A Levels in Hyperthyroidism.Document5 pagesFetuin-A Levels in Hyperthyroidism.yekimaNo ratings yet

- Hemodynamic Gain Index in WomenDocument5 pagesHemodynamic Gain Index in WomenERIK EDUARDO BRICEÑO GÓMEZNo ratings yet

- Yield of Blood Cultures in Children Presenting With Febrile Illness in A Tertiary Care HospitalDocument5 pagesYield of Blood Cultures in Children Presenting With Febrile Illness in A Tertiary Care Hospitalfaraz.mirza1No ratings yet

- Omega 3 Severidad COVID 19Document3 pagesOmega 3 Severidad COVID 19Carlos MendozaNo ratings yet

- Tabal - NR - Blood Bank & SerologyDocument4 pagesTabal - NR - Blood Bank & SerologyRamses ParconNo ratings yet

- Role of Serum Procalcitonin in Early Diagnosis of Neonatal SepsisDocument5 pagesRole of Serum Procalcitonin in Early Diagnosis of Neonatal SepsisIqbalNo ratings yet

- GlandersinhorseDocument4 pagesGlandersinhorselusitania IkengNo ratings yet

- Canine Diabetes Mellitus Risk Factors A Matched Case-Control StudyDocument5 pagesCanine Diabetes Mellitus Risk Factors A Matched Case-Control StudyLauraJerézTorresNo ratings yet

- Circulating Complexes, Iga: Precipitins, Immune and DeficiencyDocument3 pagesCirculating Complexes, Iga: Precipitins, Immune and Deficiencyroopaljain123No ratings yet

- Association of Serum Uric Acid and Cardiovascular Disease in Healthy AdultsDocument7 pagesAssociation of Serum Uric Acid and Cardiovascular Disease in Healthy Adultsfeti_08No ratings yet

- Predicting and Preventing Autoimmunity, Myth or Reality?: Michal Harel and Yehuda ShoenfeldDocument24 pagesPredicting and Preventing Autoimmunity, Myth or Reality?: Michal Harel and Yehuda ShoenfeldPollyanna MenezesNo ratings yet

- S2 3Document10 pagesS2 3Viviana MontenegroNo ratings yet

- Anti HCVDocument5 pagesAnti HCVFaisal JamshedNo ratings yet

- Prime Elisa Exams Associated ArticlesDocument3 pagesPrime Elisa Exams Associated ArticlesropherpqqrNo ratings yet

- Low 25-Hydroxyvitamin D and Risk of Type 2 Diabetes: A Prospective Cohort Study and MetaanalysisDocument4 pagesLow 25-Hydroxyvitamin D and Risk of Type 2 Diabetes: A Prospective Cohort Study and Metaanalysisfniegas172No ratings yet

- Soluble Urokinase Plasminogen Activator Receptor Predicts Mortality in Patients With Systemic Inflammatory Response SyndromeDocument8 pagesSoluble Urokinase Plasminogen Activator Receptor Predicts Mortality in Patients With Systemic Inflammatory Response SyndromeKartika Rizky LimNo ratings yet

- Serum Amyloid A in Cats With Renal AzotemiaDocument9 pagesSerum Amyloid A in Cats With Renal AzotemiaSilvanNo ratings yet

- Diagnosis of Bovine Anaplasma Marginale in North Western Libya Using Serology and Blood Film Examination - A Comparative StudyDocument14 pagesDiagnosis of Bovine Anaplasma Marginale in North Western Libya Using Serology and Blood Film Examination - A Comparative Studyyudhi arjentiniaNo ratings yet

- MedicineDocument21 pagesMedicineMusic by Martin Al KhaliliNo ratings yet

- Diagnostic Accuracy of Rklo8 Versus rk26 Elisas For Screening of Canine Visceral Leishmaniasis.Document24 pagesDiagnostic Accuracy of Rklo8 Versus rk26 Elisas For Screening of Canine Visceral Leishmaniasis.Homell MCNo ratings yet

- Cost-Benefit Paratuberculosis: Analysis Vaccination Against Dairy CattleDocument5 pagesCost-Benefit Paratuberculosis: Analysis Vaccination Against Dairy CattlearavaNo ratings yet

- Dyv 142Document12 pagesDyv 142FaziNo ratings yet

- (Journal of The American Veterinary Medical Association) in This Issue - June 15, 2017Document2 pages(Journal of The American Veterinary Medical Association) in This Issue - June 15, 2017Eduardo GuevaraNo ratings yet

- Dapus 2-Feigin2005Document9 pagesDapus 2-Feigin2005sri noviyanty yusufNo ratings yet

- Computers: Non-Invasive Sensor Technology For The Development of A Dairy Cattle Health Monitoring SystemDocument11 pagesComputers: Non-Invasive Sensor Technology For The Development of A Dairy Cattle Health Monitoring SystemVeronica HerreraNo ratings yet

- Animals 14 00986Document11 pagesAnimals 14 00986andreza.beatrizNo ratings yet

- Tithy Risk Factors BhalukaDocument10 pagesTithy Risk Factors BhalukaMobin Ibne MokbulNo ratings yet

- 69th AACC Annual Scientific Meeting Abstract eBookFrom Everand69th AACC Annual Scientific Meeting Abstract eBookNo ratings yet

- Archive of SID: Original ArticleDocument5 pagesArchive of SID: Original ArticlehardianNo ratings yet

- Evaluation of Real-Time PCR and Culturing For The Detection of Leptospires in Canine SamplesDocument9 pagesEvaluation of Real-Time PCR and Culturing For The Detection of Leptospires in Canine SamplesraviggNo ratings yet

- Animals 11 00685 v3Document12 pagesAnimals 11 00685 v3Carolina Duque RodriguezNo ratings yet

- Detecting Acute Kidney Injury in Horses by Measuring TheDocument10 pagesDetecting Acute Kidney Injury in Horses by Measuring TheMarilú ValdepeñaNo ratings yet

- The Prevalence of Subclinical Endometritis and Intrauterine Infections in Repeatbreeder CowsDocument20 pagesThe Prevalence of Subclinical Endometritis and Intrauterine Infections in Repeatbreeder CowsMaksar Muhuruna LaodeNo ratings yet

- Diagnosis Brucella TurkeyDocument5 pagesDiagnosis Brucella TurkeyJoshua SmithNo ratings yet

- Epidemiology of Colic 2023 VepDocument18 pagesEpidemiology of Colic 2023 VepAristoteles Esteban Cine VelazquezNo ratings yet

- Walkthrough21 PDFDocument51 pagesWalkthrough21 PDFAnas SantyNo ratings yet

- 524r 16 PreviewDocument4 pages524r 16 Previewosama anterNo ratings yet

- List of ReferencesDocument3 pagesList of ReferencesRave MiradoraNo ratings yet

- Lesson Plan PerdevDocument7 pagesLesson Plan PerdevPatzAlzateParaguyaNo ratings yet

- NJSHA NJABA Collaborative Practice GroupDocument4 pagesNJSHA NJABA Collaborative Practice GroupBruno PontesNo ratings yet

- 2010 - Hepatic Resection For Post-Cholecystectomy Bile Duct Injuries - A Literature ReviewDocument8 pages2010 - Hepatic Resection For Post-Cholecystectomy Bile Duct Injuries - A Literature ReviewBattousaih1No ratings yet

- Ovarian Stimulation Strategies: Maximizing Efficiency in ARTDocument21 pagesOvarian Stimulation Strategies: Maximizing Efficiency in ARTImelda HutagaolNo ratings yet

- Pentavitin - DSMDocument3 pagesPentavitin - DSMRnD Roi SuryaNo ratings yet

- EKG/ECG Study GuideDocument13 pagesEKG/ECG Study GuideSherree HayesNo ratings yet

- Activity 3: Worksheet On Developmental Tasks of Being in Grade 11Document2 pagesActivity 3: Worksheet On Developmental Tasks of Being in Grade 11Ian BoneoNo ratings yet

- Chapter 22: The Thyroid Gland: by Marissa Grotzke, Dev AbrahamDocument21 pagesChapter 22: The Thyroid Gland: by Marissa Grotzke, Dev AbrahamJanielle FajardoNo ratings yet

- EarthquakeDocument3 pagesEarthquakeFranzeine De GuzmanNo ratings yet

- IGen Book ReviewDocument6 pagesIGen Book ReviewPedro RamosNo ratings yet

- Eustachian TubeDocument6 pagesEustachian TubeNaruto_Uchiha777No ratings yet

- ABI Worksheet: Patient Name: Patient ID: DateDocument2 pagesABI Worksheet: Patient Name: Patient ID: Datezaqqi ubaidillahNo ratings yet

- Ravi Kannaiyan: QC Inspection EngineerDocument5 pagesRavi Kannaiyan: QC Inspection EngineerVinoth BalaNo ratings yet

- Gov. Youngkin's Final Budget Presentation Dec 15Document21 pagesGov. Youngkin's Final Budget Presentation Dec 15ABC7NewsNo ratings yet

- Amandeep Kaur Nursing Demonstrator Ionurc, Goindwal Sahib, PunjabDocument20 pagesAmandeep Kaur Nursing Demonstrator Ionurc, Goindwal Sahib, PunjabSanjay Kumar SanjuNo ratings yet

- Utilization of Contraceptives Among Women of Reproductive Ages in Salaga MunicipalityDocument70 pagesUtilization of Contraceptives Among Women of Reproductive Ages in Salaga MunicipalitySeyram RichardNo ratings yet

- Periop TestsDocument13 pagesPeriop TestsJohn Lyndon SayongNo ratings yet

- SJODR 48 555 556 CDocument2 pagesSJODR 48 555 556 Cyasser bedirNo ratings yet

- Mandated Reporter FormDocument2 pagesMandated Reporter FormLex TalamoNo ratings yet

- Common Errors in Dental RadiographyDocument48 pagesCommon Errors in Dental RadiographyDarwin D. J. LimNo ratings yet

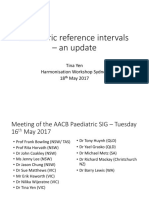

- D2 0905 Paediatric Reference Intervals - An Update - Tina YenDocument25 pagesD2 0905 Paediatric Reference Intervals - An Update - Tina YenkamalNo ratings yet

- Arne Langaskens - HerbalistDocument3 pagesArne Langaskens - HerbalistFilipNo ratings yet

- COVID-19 and A-Dec Dental Equipment Infection Control: Dear Valued CustomerDocument4 pagesCOVID-19 and A-Dec Dental Equipment Infection Control: Dear Valued CustomerAlleirbag KajnitisNo ratings yet

- Cumulative Adversity As A Correlate of Posttraumatic GrowthDocument20 pagesCumulative Adversity As A Correlate of Posttraumatic GrowthLorena RodríguezNo ratings yet