Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Music As Therapy Author Kathi J Kemper, Suzanne C Danhauer

Uploaded by

Angel YakOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Music As Therapy Author Kathi J Kemper, Suzanne C Danhauer

Uploaded by

Angel YakCopyright:

Available Formats

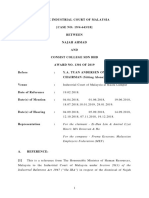

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.

net/publication/264954368

Music as Therapy

Article in Southern Medical Journal · April 2005

DOI: 10.1097/01.SMJ.0000154773.11986.39

CITATIONS READS

202 21,376

2 authors:

Kathi J Kemper Suzanne C Danhauer

The Ohio State University Wake Forest School of Medicine

350 PUBLICATIONS 7,399 CITATIONS 115 PUBLICATIONS 3,196 CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE

Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects:

Burnout in Pediatric Residents View project

Holistic care for children View project

All content following this page was uploaded by Kathi J Kemper on 06 February 2018.

The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file.

Featured CME Topic: Complementary and Alternative Medicine

Music as Therapy

Kathi J. Kemper, MD, MPH, and Suzanne C. Danhauer, PHD

Abstract: Music is widely used to enhance well-being, reduce stress, classical music for the infants. The day shift nurses usu-

and distract patients from unpleasant symptoms. Although there are ally listen to a soft rock music station on the radio, and

wide variations in individual preferences, music appears to exert direct are reluctant to change. The evening and night shift

physiologic effects through the autonomic nervous system. It also has nurses have not played any music. Is there any evidence

indirect effects by modifying caregiver behavior. Music effectively re- that music affects newborn infants? If so, what kind of

duces anxiety and improves mood for medical and surgical patients, for music might be best?

patients in intensive care units and patients undergoing procedures, and Increasing numbers of patients in gastrointestinal

for children as well as adults. Music is a low-cost intervention that often clinics bring their own CD or MP3 players to clinic

reduces surgical, procedural, acute, and chronic pain. Music also im- visits to help them relax during colonoscopy. What is the

proves the quality of life for patients receiving palliative care, enhanc- evidence that music reduces anxiety, improves mood, or

ing a sense of comfort and relaxation. Providing music to caregivers eases the stress associated with procedures? Do all peo-

may be a cost-effective and enjoyable strategy to improve empathy, ple respond the same way to the same kinds of music, or

compassion, and relationship-centered care while not increasing errors should everyone just listen to whatever they like (eg,

or interfering with technical aspects of care. pop and grunge rock for teenagers, classical music or

Key Words: allied health, anxiety, complementary therapy, music,

jazz for adults)?

pain, relaxation, stress

Some of the nurses in the preoperative and postop-

erative areas provide headphones and play New Age

music for their patients. Is there any evidence that music

M usic has been used since ancient times to enhance well-

being and reduce pain and suffering. This article will re-

view the medically relevant effects of music, focusing on pain,

helps reduce pain or enhances wound healing in the

perioperative period?

A harpist volunteers at the local hospice. What role

anxiety, and mood. We will not discuss the use of music to does music have in end-of-life care?

enhance cognitive development (ie, the “Mozart effect”) or for One surgeon prefers to listen to country western

patients with severe developmental delays, dementia, psychiatric while another likes classical. How does listening to mu-

disorders, neurologic disorders, sensory handicaps, or in institu- sic affect clinician or caregiver performance?

tional settings such as correctional facilities or schools, though a

great deal of work has been done in these areas.

Illness, injuries, and hospitalization are stressful. Hospi-

talized patients are susceptible to environmental stressors such

as cold temperatures, noise, and bright lights, in addition to

Cases and Questions

One of the new physicians on staff in your newborn the pain, discomfort, and anxiety associated with their med-

nursery suggests that you start playing recordings of

Key Points

• Music is widely used to promote a sense of well-being

From the Department of Pediatrics and the Department of Internal Medicine,

Section of Hematology and Oncology, Wake Forest University School of and to distract patients from pain and other unpleasant

Medicine, Winston-Salem, NC. symptoms, thoughts, and feelings, while being con-

Supported in part by National Institutes of Health National Center for Com- venient and readily available.

plementary and Alternative Medicine grant R25 AT00538. • Music helps to improve mood and decrease anxiety,

The authors have no commercial or proprietary interest in any aspect of as well as decrease the pain associated with surgery,

music therapy.

medical procedures, and chronic conditions; it also

Reprint requests to Dr. Kathi J. Kemper, Wake Forest University Health

Sciences, Department of Pediatrics, Medical Center Blvd., Winston- helps ease the dying process.

Salem, NC 27157. Email: rfoley@wfubmc.edu • Music may help premature babies to gain weight more

Accepted December 13, 2004. quickly.

Copyright © 2005 by The Southern Medical Association • Music may enhance care-giving behavior.

0038-4348/05/9803-0282

282 © 2005 Southern Medical Association

Featured CME Topic: Complementary and Alternative Medicine

ical conditions and treatments. Stress may interfere with sleep, Music therapy is recognized as an established allied

appetite, digestion, growth, behavior, and wound healing. health profession that uses music to facilitate therapeutic pro-

Stress may also adversely affect the cardiovascular, neuroen- cesses.9 Music therapists are typically musicians who have

docrine, and immune systems, which, in turn, may impair undergone specific training in using music and the therapist’s

recovery, increase risk for adverse effects, and delay hospital self to accomplish therapeutic aims: the restoration, mainte-

discharge.1,2 Recently, the use of structured stimuli has been nance, and improvement of mental and physical health. Mu-

encouraged to reduce stress, using techniques such as regular sic therapists work in a variety of settings as part of the health

cycling of light and dark, massage, and music therapy.3–5 care team. The American Musical Therapy Association has

more than 2,500 members working in hospitals, clinics,

schools, day care centers, hospices, rehabilitation centers, cor-

Definitions rectional facilities, and private practice settings. However,

Environmental sounds that exist without controls for vol-

even in the absence of a professional music therapist, many

ume, duration, or cause/effect relations are perceived as noise.

patients and clinicians listen to or play music to manage

The most well-known adverse effects of exposure to exces-

stress, anxiety, and pain in clinical settings.

sive noise are related to hearing damage; noise also contrib-

Music may have different effects, based on listener char-

utes to fatigue, hyperalerting, insomnia, and decreased appe-

acteristics: age, culture, medical conditions that affect hear-

tite. In mice, exposure to noise leads to physiologic stress,

ing, musical aptitude, and experience. Other factors affecting

manifested as significantly increased airway reactivity and

music influence include elements of the music (tempo, pitch,

increased allergic reactions.6 Among infants hospitalized in

harmony, melody, rhythm), means of delivery (headphones,

the neonatal intensive care unit, excessive noise is correlated

speaker, open air, live versus recorded), setting (group or

with decreases in oxygen saturation and increases in heart

alone), and active versus passive participation.10

rate and sleep disturbances.7

Music is an intentional auditory stimulus with organized

elements including melody, rhythm, harmony, timbre, form, What Does Music Do for Patients?

and style. Repetitive listening allows the listener to identify Music and music therapy may benefit patients directly:

and predict sounds.5 Thus, repeated exposure may enhance physiologically, psychologically, and socioemotionally. Mu-

clinical effects. However, excessive repetition may lead to sic may also affect patients indirectly through its effects on

boredom and irritation. caregiver attitudes and behaviors. With regard to direct phys-

iologic effects, in animals, music changes neuronal activity

with entrainment to musical rhythms in the lateral temporal

Epidemiology lobe and in cortical areas devoted to movement. Steady

Music is ubiquitous in all human cultures and is listened

rhythms entrain respiratory patterns. Listening to classical

to by persons of all ages, races, and ethnic backgrounds. One

music increases heart rate variability, a measure of cardiac

measure of the popularity of a topic is the number of Internet

autonomic balance (in which increased levels reflect less

sites devoted to that topic. Using this metric, music (at 131

stress and greater resilience), whereas listening to noise or

million sites) follows sex (at 185 million sites) in terms of the

rock music decreases heart rate variability (reflecting greater

most popular listings on the Google Internet search engine

stress).11,12 In students engaged in stressful tasks, lower sal-

(search October 22, 2003).8 Not surprisingly, different kinds

ivary cortisol levels are noted in those listening to music

of music appeal to persons of different ages and ethnic back-

compared with control subjects, whose cortisol levels in-

grounds, and the same person may desire different kinds of

creased.13 Music affects mu opiate receptor expression, mor-

music under different circumstances. For example, nursery

phine-6 glucuronide, and interleukin-6 levels in healthy vol-

rhymes may be soothing for toddlers, but hearing the “Ses-

unteers.14 Its effects may be mediated by nitric oxide, but the

ame Street” or “Barney” song several times daily can be

precise mechanisms remain speculative.15

irritating for adolescents or parents. High-tempo contempo-

rary music is often used to increase athletic performance,

whereas baroque music may be preferred for relaxing after a Types of Music

stressful examination, and jazz may be preferred for social- Although there are wide individual and cultural varia-

izing. Recently, specific types of music have been marketed tions in types of music preferred, certain kinds of music ap-

to enhance pediatric development (eg, the Mozart effect), to pear to have consistent physiologic effects.16 In one study, for

address cognitive problems, and to enhance effectiveness of example, adults and teenagers listened to four different types

other complementary therapies such as Reiki and massage. of music: classical, grunge rock, new age, and designer (de-

Although these strategies remain somewhat controversial, mu- signed to enhance a sense of well-being). At baseline and

sic has long been used as a complementary healing therapy to immediately after listening to each kind of music, respon-

soothe patients afflicted with pain, anxiety, and a variety of dents completed a survey of personal feelings. Classical mu-

illnesses and injuries. sic decreased tension but had little effect on other feelings.

Southern Medical Journal • Volume 98, Number 3, March 2005 283

Kemper and Danhauer • Music as Therapy

Listening to grunge rock led to significant increases in hostility, coronary bypass surgery showed a significant improvement

fatigue, sadness, and tension and significant decreases in relax- in mood.30 However, in a study of children undergoing sur-

ation, mental clarity, vigor, and a sense of compassion. With gery, those who listened to music before surgery had similar

new age music, there was a significant increase in relaxation and reduction in anxiety compared with patients receiving usual

reductions in hostility, mental clarity, vigor, and tension. After care and more anxiety than patients who received midazo-

listening to designer music, subjects reported significantly more lam.31 Taken together, these studies generally demonstrate

relaxation, mental clarity, vigor, and compassion and signifi- beneficial effects of music therapy on psychologic outcomes

cantly decreased hostility, sadness, fatigue, and tension. Teen- in surgery patients; no adverse outcomes or side effects have

agers had negative psychological and emotional responses to been reported.

grunge rock music, even when they usually liked listening to it Music also benefits mood in oncology patients. In a sam-

outside the study setting. ple of stem cell transplant patients, those receiving music

therapy reported substantially lower psychologic distress than

a control group, both immediately after the music therapy

Music for Premature Infants

session and during the course of the inpatient stay.32 Among

Among premature infants, lullabies and classical music

cancer patients undergoing radiotherapy, those patients whose

appear to increase weight gain, decrease episodes of oxygen

anxiety level was higher at the start were most likely to ben-

desaturation, decrease distressed behaviors, and increase non-

efit from the music intervention.33 Music therapy can also

nutritive sucking, all of which may decrease length of hos-

improve mood in pediatric oncology patients.34,35 A study of

pital stay.5,17–20 In premature infants, exposure to harp music

patients at a cancer help center compared effects of passively

resulted in significantly lower salivary cortisol levels and

listening to music versus active involvement in improvisation

lower respiratory rates. While listening to music, infants be-

in a group setting. Both of these music groups showed a

come quiet and appear to fall asleep; these decreases in ac-

decreased tension level and shared comments about how mu-

tivity may reduce caloric expenditure, enhance weight gain,

sic affected their mood: “relaxed and uplifted,” “soothing and

and hasten hospital discharge.21 The effects of country west-

relaxing,” “calmed my nerves,” and “felt calm and happy.”36

ern, pop, jazz, and other types of music on premature infants

have not been systematically compared with the effects of In other clinical settings including intensive care units

lullabies and classical music, nor has live music been com- (ICU), music has been shown to reduce patients’ anxiety and

pared directly with recorded music in this setting. depression.26,37–39 One study of patients on mechanical ven-

tilators in the ICU demonstrated that music therapy was more

effective at decreasing anxiety than an uninterrupted rest pe-

Music and Mood in Medical and riod.40 Another RCT of alert patients on mechanical ventila-

Surgical Patients tors randomly assigned to a 30-minute patient-selected music

Providing music on a hospital ward and in perioperative condition or a rest period showed significant between-group

or waiting areas can create a positive milieu for patients, differences on anxiety level, heart rate, and respiration rate as

families, and staff.22–24 Creating such an environment can well as a greater reduction in anxiety in the music group.39

have significant effects on patients’ moods in terms of anx- Music also reduces anxiety associated with unpleasant or

iety, depression, and perceived stress. Furthermore, positive uncomfortable procedures such as bronchoscopy, colposcopy,

physiologic changes such as increased levels of salivary im- and colonoscopy41– 43; providing recorded music can be as or

munoglobulin A and decreased serum cortisol levels often more effective in reducing patients’ anxiety than preoperative

accompany changes in anxiety and stress levels.25 A review teaching, counseling, or relaxation training, while costing far

article of 29 randomized, controlled trials (RCTs) of music less.44,45 For example, an RCT of 198 patients having colonos-

therapy revealed that music helps reduce anxiety in hospital- copy or endoscopy demonstrated that listening to 15 minutes

ized patients.26 of self-selected music before the procedure significantly re-

For example, music can improve mood and reduce anx- duced anxiety compared with a control group.42 Another RCT

iety in surgical patients. In a study of effects of listening to conducted with patients undergoing flexible sigmoidoscopy

music on preoperative anxiety in men undergoing prostate showed a significant decrease in anxiety for the music group

surgery, participants in a music intervention had significantly compared with usual care, controlling for baseline anxiety

reduced anxiety and blood pressure.27 Patients about to un- levels.46 Among patients having day procedures (cytoscopy,

dergo surgery with spinal anesthesia who listened to music cauterization, endoscopy), those who listened to music while

required less sedative to achieve a similar degree of relax- awaiting the procedure reported lower anxiety than a control

ation compared with a control group.28 In a study of 20 group.47

women awaiting breast biopsy, the group that received 20 However, other studies of music therapy in patients un-

minutes of music had less anxiety than usual care patients, dergoing procedures have yielded more equivocal findings.

after controlling for baseline anxiety.29 Similarly, a study of In an RCT of 20 patients awaiting cardiac catheterization,

a music intervention during the postoperative period after those randomly assigned to listen to 20 minutes of preselected

284 © 2005 Southern Medical Association

Featured CME Topic: Complementary and Alternative Medicine

music had significantly lower anxiety than a control group Music has proven effective in reducing pain associated

and also showed a significant reduction in anxiety level, blood with a variety of procedures, including burn debridement,

pressure, and heart rate.48 Similarly, nearly 70% of patients laceration repair, lumbar punctures, insertion of intravenous

enrolled in an RCT of music therapy for cardiac catheteriza- lines, immunizations, and dental procedures.59 – 65 Several

tion reported that music made them feel less tense, more RCTs of music therapy for patients undergoing colonoscopy

relaxed, and safer.49 However, in another RCT of 45 patients or flexible sigmoidoscopy have found that compared with

undergoing cardiac catheterization, music therapy did not sig- patients in control groups, those who listened to music re-

nificantly reduce anxiety, improve mood, or reduce patient ported significantly lower pain levels, less physician-admin-

uncertainty.50 Similarly, in an RCT of 60 patients undergoing istered sedation, and shorter examination times.46,66 – 68

flexible fiberoptic bronchoscopy, no significant between- Music can effectively decrease patients’ perceptions of

group differences between music therapy and control groups and responses to pain during labor and in very young prema-

were demonstrated.51 Likewise, an RCT of 58 cancer patients ture infants as well as other populations of patients with

having unpleasant medical procedures (tissue biopsy, port chronic pain.69,70 Women in labor who listened to soft music

placement/removal) randomly assigned to music therapy or reported substantially less distress related to pain and per-

simple distraction conditions found no significant effects for ceived music as helpful to them.71 Older adults who listened

a music intervention compared with simple distraction.52 to music 20 minutes daily for 2 weeks reported decreased

In summary, there is good evidence for use of music chronic osteoarthritis pain compared with a control group

therapy with surgery patients and cancer patients but mixed whose pain level remained constant.72 The majority of cancer

evidence for use of music therapy with patients having med- patients have at least moderate pain relief from music, and

ical procedures. Perhaps factors that affect the effectiveness music is often offered as an adjunctive therapy in progressive

of music therapy in patients awaiting or undergoing uncom- cancer centers.73,74 A recent pilot study evaluated the impact

fortable procedures include individual differences such as mu- of music therapy on self-reported pain and nausea as well as

sic preferences, initial anxiety level, and level of interest in the time to engraftment among patients undergoing a bone

being distracted from the procedure. Music therapy may offer marrow transplant; in this very ill population, cancer patients

benefit to some patients undergoing these procedures by help- who received music therapy with relaxation imagery reported

ing to divert their attention from potentially unpleasant ex- less pain and nausea and objectively had more rapid engraft-

periences; however, it may be important to tailor the inter- ment of their transplant.75

vention to patient desires and preferences.

Effects on Pain Music in End-of-life Care

Many studies of the effects of music therapy on pain Music therapy can improve the quality of life for dying

relief have had methodologic problems, such as small sample patients.76,77 Music therapy can foster supportive interactions

size, lack of random assignment, and lack of control for pa- between patients and loved ones and help patients connect

tient anesthesia.53,54 These issues notwithstanding, overall with and express emotions in a less threatening manner than

music is a low-cost intervention that is appealing to patients verbal expression. In working with persons who are dying,

and often helps reduce pain.53,54 music may provide a means of transcending patient experi-

Playing music for patients during or after surgery helps ences of physical symptoms and declines.22

reduce pain and use of morphine and other sedatives, anxio- Descriptive and qualitative research provides some data

lytics, and analgesics.55,56 A series of 17 vascular and tho- on benefits of music therapy in end-of-life care. Regarding

racic surgery patients who listened to live harp music showed their experience in a palliative care music therapy program,

substantially decreased pain levels after the music session.23 57% of surveyed patients reported that participation in the

In a study of 311 gynecologic surgery patients, compared program helped them to feel more relaxed or improved their

with usual care, patients who received music, relaxation, or affect.78 Staff members reported that music seemed most ef-

their combination used substantially less patient-controlled fective in the areas of patient satisfaction, stress reduction,

pain medications.57 A similar study of 500 abdominal surgery anxiety reduction, and patient receptivity.78 In a palliative

patients demonstrated that patients receiving music therapy, care music therapy program where patients wrote songs, lyr-

relaxation, or a combination reported significantly lower pain ical themes that emerged included messages to others (posi-

levels than a control group.58 An RCT of 150 patients under- tive feelings and gratitude), self-reflections, compliments (to

going inguinal hernia or varicose vein surgery examined dif- staff, other patients, family, friends), memories, reflections

ferences in pain relief, depending on whether music was on significant others, expression of loss and difficulty related

played during or after surgery; there were significant short- to illness, imagery, and prayers.10

term pain reductions in both music groups compared with a In a study of single-session music interventions for ter-

control group, regardless of whether music was played during minally ill patients, significant pre- to post-session changes

or after surgery.56 were found for pain control, physical comfort, and feelings of

Southern Medical Journal • Volume 98, Number 3, March 2005 285

Kemper and Danhauer • Music as Therapy

relaxation.79 In a study of effects of music therapy on home Resources

hospice patients, patients were randomly assigned to receive

music therapy versus routine hospice care alone77; patients in Books

the music therapy group reported higher quality of life, and Aldridge D, ed. Music Therapy in Palliative Care, and

their quality of life increased with greater numbers of music Music Therapy with Children. Jessica Kingsley Publications,

therapy sessions. London, 1999.

Alvin J, Warwick A. Music Therapy for the Autistic

Child. 2nd edition. Oxford University Press, New York, 1991.

Effects on Clinicians/Caregivers

Music may also affect patients indirectly through its ef- Campbell D. The Mozart Effect. Avon Books, New York,

fects on the perceived environment and on caregivers. For 1997.

example, one study suggested that self-selected music en- Davis WB, Gfeller KE, Thaut MH. An Introduction to

hanced speed and accuracy of surgeons’ performance on a Music Therapy. 2nd edition. McGraw-Hill, Boston, 1999.

stressful nonsurgical task compared with those who did not

Gaynor M. The Healing Power of Sound. Shambhala

listen to music or listened to music selected by the experi-

Publications, Inc, Boston, MA, 1999.

menters.80 Another study of long-term care workers found

that participation in group music therapy sessions yielded less Lane D. Music as Medicine. Harper Collins, New York,

burnout and improved mood.81 A third study suggested that 1994.

parents preferred providing chest percussion for their children

Wigram T, Pedersen IN, Bonde LO. A Comprehensive

with cystic fibrosis if music was played during the treat- Guide to Music Therapy: Theory, Clinical Practice, Research

ment.82 In a survey of staff in a neonatal ICU, staff members and Training. Jessica Kingsley Publications, London, 2002

thought that music could be helpful to patients and would not (note: This book includes two CDs).

increase work-related errors but that having a live musician

might interfere with work flow; staff in this setting strongly Shore R. Baby Teacher: Nurturing Neural Networks From

preferred classical or instrumental music to other types of Birth to Age Five. Scarecrow Press, Kent, England, 2002.

music and preferred recorded to live music.83 Medical schools

are beginning to include music in courses on medical human- Internet sites

ism to promote desirable physician characteristics such as American Music Therapy Association. This page pro-

caring, empathy, respect for human dignity, compassion, and vides an address for asking about music therapists in one’s

fostering relationships.84 geographic area and answers frequently asked questions about

professional music therapy. http://www.musictherapy.org/.

Music Therapy in Palliative Care. http://www.mtabc.com/

Risks and Costs palliative.html.

Music is quite safe, as long as common sense precautions

are used to avoid excessive volume. With the advent of small University Hospitals of Cleveland. Music as Medicine Pro-

boom boxes and personal CD and MP3 players, music is an gram for Pediatrics. http://www.musicasmedicine.com/info/

inexpensive service to provide, even on an individual basis. resc_peds.htm.

To minimize the risk of spreading infectious diseases, pa-

tients may be advised to bring their own headphones (often References

available at discount stores). 1. Watkins A. Mind-Body Medicine. New York, Churchill Livingstone,

1997.

2. Biondi M, Zannino LG. Psychological stress, neuroimmunomodulation,

and susceptibility to infectious diseases in animals and man: a review.

Conclusion Psychother Psychosom 1997;66:3–26.

Music plays a central role in all human cultures. It has 3. Aucott S, Donohue PK, Atkins E, et al. Neurodevelopmental care in the

direct and indirect effects on physiology and clinical symp- NICU. Ment Retard Dev Disabil Res Rev 2002;8:298 –308.

toms. Carefully selected music can reduce stress, enhance a 4. Ferber SG, Kuint J, Weller A, et al. Massage therapy by mothers and

sense of comfort and relaxation, offer distraction from pain, trained professionals enhances weight gain in preterm infants. Early

Hum Dev 2002;67:37– 45.

and enhance clinical performance. Additional research is

5. Standley JM. A meta-analysis of the efficacy of music therapy for pre-

needed to better define its optimal role in comprehensive, mature infants. J Pediatr Nurs 2002;17:107–113.

cost-effective patient care. With such research ongoing, mu-

6. Joachim RA, Quarcoo D, Arck PC, et al. Stress enhances airway reac-

sic therapy appears to be safe and likely helpful to a broad tivity and airway inflammation in an animal model of allergic bronchial

spectrum of patients in diverse clinical situations. asthma. Psychosom Med 2003;65:811– 815.

286 © 2005 Southern Medical Association

Featured CME Topic: Complementary and Alternative Medicine

7. Kellman N. Noise in the intensive care nursery. Neonatal Netw 2002; therapy as a treatment for preoperative anxiety in children: a randomized

21:35– 41. controlled trial. Anesth Analg 2004;98:1260 –1266.

8. Dossey L. Taking note: music, mind, and nature. Altern Ther Health 32. Cassileth BR, Vickers AJ, Magill LA. Music therapy for mood distur-

Med 2003;9:10 –14, 94 –100. bance during hospitalization for autologous stem cell transplantation: a

randomized controlled trial. Cancer 2003;98:2723–2729.

9. Davis WB, Gfeller KE, Thaut MH. An Introduction to Music Therapy.

2nd edition. Boston, McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc, 1999. 33. Smith M, Casey L, Johnson D, et al. Music as a therapeutic intervention

for anxiety in patients receiving radiation therapy. Oncol Nurs Forum

10. Aldridge D. The therapeutic effects of music, in Jonas W, Crawford CC

2001;28:855– 862.

(eds): Healing, Intention and Energy Medicine. London, Churchill Liv-

ingstone, 2003. 34. Barrera ME, Rykov MH, Doyle SL. The effects of interactive music

therapy on hospitalized children with cancer: a pilot study. Psychooncol-

11. Umemura M, Honda K. Influence of music on heart rate variability and ogy 2002;11:379 –388.

comfort: a consideration through comparison of music and noise. J Hum

Ergol (Tokyo) 1998;27:30 –38. 35. Magill L. The use of music therapy to address the suffering in advanced

cancer pain. J Palliat Care 2001;17:167–172.

12. White JM. Effects of relaxing music on cardiac autonomic balance and

anxiety after acute myocardial infarction. Am J Crit Care 1999;8:220 – 36. Burns DS. The effect of the bonny method of guided imagery and music

230. on the mood and life quality of cancer patients. J Music Ther 2001;38:

51– 65.

13. Khalfa S, Bella SD, Roy M, et al. Effects of relaxing music on salivary

cortisol level after psychological stress. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2003;999: 37. Guzzetta CE. Effects of relaxation and music therapy on patients in a

374 –376. coronary care unit with presumptive acute myocardial infarction. Heart

Lung 1989;18:609 – 616.

14. Stefano GB, Zhu W, Cadet P, et al. Music alters constitutively expressed

opiate and cytokine processes in listeners. Med Sci Monit 2004;10: 38. Vickers AJ, Cassileth BR. Unconventional therapies for cancer and can-

MS18 –MS27. cer-related symptoms. Lancet Oncol 2001;2:226 –232.

39. Chlan L. Effectiveness of a music therapy intervention on relaxation and

15. Salamon E, Kim M, Beaulieu J, et al. Sound therapy induced relaxation:

anxiety for patients receiving ventilatory assistance. Heart Lung 1998;

down regulating stress processes and pathologies. Med Sci Monit 2003;

27:169 –176.

9:RA96-RA101.

40. Wong HL, Lopez-Nahas V, Molassiotis A. Effects of music therapy on

16. McCraty R, Barrios-Choplin B, Atkinson M, et al. The effects of dif-

anxiety in ventilator-dependent patients. Heart Lung 2001;30:376 –387.

ferent types of music on mood, tension, and mental clarity. Altern Ther

Health Med 1998;4:75– 84. 41. Chan YM, Lee PW, Ng TY, et al. The use of music to reduce anxiety for

patients undergoing colposcopy: a randomized trial. Gynecol Oncol

17. Collins SK, Kuck K. Music therapy in the neonatal intensive care unit. 2003;91:213–217.

Neonatal Netw 1991;9:23–26.

42. Hayes A, Buffum M, Lanier E, et al. A music intervention to reduce

18. Caine J. The effects of music on the selected stress behaviors, weight, anxiety prior to gastrointestinal procedures. Gastroenterol Nurs 2003;

caloric and formula intake, and length of hospital stay of premature and 26:145–149.

low birth weight neonates in a newborn intensive care unit. J Music Ther

1991;28:180 –192. 43. Dubois JM, Bartter T, Pratter MR. Music improves patient comfort level

during outpatient bronchoscopy. Chest 1995;108:129 –130.

19. Standley JM, Moore RS. Therapeutic effects of music and mother’s

voice on premature infants. Pediatr Nurs 1995;21:509 –512, 574. 44. Augustin P, Hains AA. Effect of music on ambulatory surgery patients’

preoperative anxiety. AORN J 1996;63:750, 753–758.

20. Standley JM. The effect of music and multimodal stimulation on re-

sponses of premature infants in neonatal intensive care. Pediatr Nurs 45. Elliott D. The effects of music and muscle relaxation on patient anxiety

1998;24:532–538. in a coronary care unit. Heart Lung 1994;23:27–35.

46. Chlan L, Evans D, Greenleaf M, et al. Effects of a single music therapy

21. Block S, Jennings D, David L. Live harp music decreases salivary cor-

intervention on anxiety, discomfort, satisfaction, and compliance with

tisol levels in convalescent preterm infants. Pediatr Res 2003;53:469A.

screening guidelines in outpatients undergoing flexible sigmoidoscopy.

22. Aldridge D. Music Therapy in Palliative Care: New Voices. London/ Gastroenterol Nurs 2000;23:148 –156.

Philadelphia, Jessica Kingsley Publishers, 1999.

47. Lee D, Henderson A, Shum D. The effect of music on preprocedure

23. Aragon D, Farris C, Byers JF. The effects of harp music in vascular and anxiety in Hong Kong Chinese day patients. J Clin Nurs 2003;13:297–

thoracic surgical patients. Altern Ther Health Med 2002;8:52–54, 56 – 303.

60. 48. Hamel WJ. The effects of music intervention on anxiety in the patient

24. Shertzer KE, Keck JF. Music and the PACU environment. J Perianesth waiting for cardiac catheterization. Intensive Crit Care Nurs 2001;17:

Nurs 2001;16:90 –102. 279 –285.

25. Urakawa K, Yokoyama K. Can relaxation programs with music enhance 49. Thorgaard B, Henriksen BB, Pedersbaek G, et al. Specially selected

human immune function? J Altern Complement Med 2004;10:605– 606. music in the cardiac laboratory-an important tool for improvement of the

well-being of patients. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs 2004;3:21–26.

26. Evans D. The effectiveness of music as an intervention for hospital

patients: a systematic review. J Adv Nurs 2002;37:8 –18. 50. Colt HG, Powers A, Shanks TG. Effect of music on state anxiety scores

in patients undergoing fiberoptic bronchoscopy. Chest 1999;116:819 –

27. Yung PM, Chui-Kam S, French P, et al. A controlled trial of music and 824.

pre-operative anxiety in Chinese men undergoing transurethral resection

of the prostate. J Adv Nurs 2002;39:352–359. 51. Taylor-Piliae RE, Chair SY. The effect of nursing interventions utilizing

music therapy or sensory information on Chinese patients’ anxiety prior

28. Lepage C, Drolet P, Girard M, et al. Music decreases sedative require- to cardiac catheterization: a pilot study. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs 2002;

ments during spinal anesthesia. Anesth Analg 2001;93:912–916. 1:203–211.

29. Haun M, Mainous RO, Looney SW. Effect of music on anxiety of 52. Kwekkeboom KL. Music versus distraction for procedural pain and

women awaiting breast biopsy. Behav Med 2001;27:127–132. anxiety in patients with cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum 2003;30:433– 440.

30. Barnason S, Zimmerman L, Nieveen J. The effects of music interven- 53. Dunn K. Music and the reduction of post-operative pain. Nurs Stand

tions on anxiety in the patient after coronary artery bypass grafting. 2004;18:33–39.

Heart Lung 1995;24:124 –132. 54. Good M. Effects of relaxation and music on postoperative pain: a re-

31. Kain ZN, Caldwell-Andrews AA, Krivutza DM, et al. Interactive music view. J Adv Nurs 1996;24:905–914.

Southern Medical Journal • Volume 98, Number 3, March 2005 287

Kemper and Danhauer • Music as Therapy

55. Koch ME, Kain ZN, Ayoub C, et al. The sedative and analgesic sparing 70. Joyce BA, Keck JF, Gerkensmeyer J. Evaluation of pain management

effect of music. Anesthesiology 1998;89:300 –306. interventions for neonatal circumcision pain. J Pediatr Health Care

56. Nilsson U, Rawal N, Unosson M. A comparison of intra-operative or 2001;15:105–114.

postoperative exposure to music: a controlled trial of the effects on 71. Phumdoung S, Good M. Music reduces sensation and distress of labor

postoperative pain. Anaesthesia 2003;58:699 –703. pain. Pain Manag Nurs 2003;4:54 – 61.

57. Good M, Anderson GC, Stanton-Hicks M, et al. Relaxation and music 72. McCaffrey R, Freeman E. Effect of music on chronic osteoarthritis pain

reduce pain after gynecologic surgery. Pain Manag Nurs 2002;3:61–70. in older people. J Adv Nurs 2003;44:517–524.

58. Good M, Stanton-Hicks M, Grass JA, et al. Relief of postoperative pain 73. Beck SL. The therapeutic use of music for cancer-related pain. Oncol

with jaw relaxation, music and their combination. Pain 1999;81:163– Nurs Forum 1991;18:1327–1337.

172.

74. Standley JM, Hanser SB. Music therapy research and applications in

59. Fratianne RB, Prensner JD, Huston MJ, et al. The effect of music-based pediatric oncology treatment. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs 1995;12:3–10.

imagery and musical alternate engagement on the burn debridement

process. J Burn Care Rehabil 2001;22:47–53. 75. Sahler O, Hunter B, JL L. The effect of using music therapy with

relaxation imagery in the management of patients undergoing bone mar-

60. Baghdadi ZD. Evaluation of audio analgesia for restorative care in chil- row transplantation: a pilot feasibility study. Alt Ther Health Med 2003;

dren treated using electronic dental anesthesia. J Clin Pediatr Dent 9:70 –74.

2000;25:9 –12.

76. Halstead MT, Roscoe ST. Restoring the spirit at the end of life: music as

61. Hanser SB. Using music therapy as distraction during lumbar punctures. an intervention for oncology nurses. Clin J Oncol Nurs 2002;6:332–336.

J Pediatr Oncol Nurs 1993;10:2.

77. Hilliard RE. The effects of music therapy on the quality and length of

62. Jacobson AF. Intradermal normal saline solution, self-selected music, life of people diagnosed with terminal cancer. J Music Ther 2003;40:

and insertion difficulty effects on intravenous insertion pain. Heart Lung 113–137.

1999;28:114 –122.

78. Gallagher LM, Huston MJ, Nelson KA, et al. Music therapy in palliative

63. Menegazzi JJ, Paris PM, Kersteen CH, et al. A randomized, controlled medicine. Support Care Cancer 2001;9:156 –161.

trial of the use of music during laceration repair. Ann Emerg Med 1991;

20:348 –350. 79. Krout RE. The effects of single-session music therapy interventions on

the observed and self-reported levels of pain control, physical comfort,

64. Prensner JD, Yowler CJ, Smith LF, et al. Music therapy for assistance

and relaxation of hospice patients. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2001;18:

with pain and anxiety management in burn treatment. J Burn Care

383–390.

Rehabil 2001;22:83– 88.

80. Allen K, Blascovich J. Effects of music on cardiovascular reactivity

65. Megel ME, Houser CW, Gleaves LS. Children’s responses to immuni-

among surgeons. JAMA 1994;272:882– 884.

zations: lullabies as a distraction. Issues Compr Pediatr Nurs 1998;21:

129 –145. 81. Bittman B, Bruhn KT, Stevens C, et al. Recreational music-making: a

66. Schiemann U, Gross M, Reuter R, et al. Improved procedure of colonos- cost-effective group interdisciplinary strategy for reducing burnout and

copy under accompanying music therapy. Eur J Med Res 2002;7:131– improving mood states in long-term care workers. Adv Mind Body Med

134. 2003;19:4 –15.

67. Smolen D, Topp R, Singer L. The effect of self-selected music during 82. Grasso MC, Button BM, Allison DJ, et al. Benefits of music therapy as

colonoscopy on anxiety, heart rate, and blood pressure. Appl Nurs Res an adjunct to chest physiotherapy in infants and toddlers with cystic

2002;15:126 –136. fibrosis. Pediatr Pulmonol 2000;29:371–381.

68. Uedo N, Ishikawa H, Morimoto K, et al. Reduction in salivary cortisol 83. Kemper K, Martin K, Block SM, et al. Attitudes and expectations about

level by music therapy during colonoscopic examination. Hepatogastro- music therapy for premature infants among staff in a neonatal intensive

enterology 2004;51:451– 453. care unit. Altern Ther Health Med 2004;10:50 –54.

69. Butt ML, Kisilevsky BS. Music modulates behaviour of premature in- 84. Newell GC, Hanes DJ. Listening to music: the case for its use in teach-

fants following heel lance. Can J Nurs Res 2000;31:17–39. ing medical humanism. Acad Med 2003;78:714 –719.

Criticism is prejudice made plausible.

––Henry Louis Mencken

288 © 2005 Southern Medical Association

View publication stats

You might also like

- Musica Therapy 2005Document8 pagesMusica Therapy 2005GuillermoHernándezNo ratings yet

- Berlin1998 PDFDocument2 pagesBerlin1998 PDFRafael Camilo MayaNo ratings yet

- The Functions of Music TherapyDocument12 pagesThe Functions of Music Therapykeby7mhmNo ratings yet

- Music Therapy Article Revised - Helen GuDocument5 pagesMusic Therapy Article Revised - Helen GuEmanuele MareaNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S1524904216301552 Main PDFDocument8 pages1 s2.0 S1524904216301552 Main PDFgiselle garciaNo ratings yet

- The Effects of Music Therapy in Cardiac Healthcare: Suzanne B. Hanser, Edd, and Susan E. Mandel, MedDocument6 pagesThe Effects of Music Therapy in Cardiac Healthcare: Suzanne B. Hanser, Edd, and Susan E. Mandel, MedmeytiNo ratings yet

- Music Therapy: Other Common Name(s) : None Scientific/medical Name(s) : NoneDocument6 pagesMusic Therapy: Other Common Name(s) : None Scientific/medical Name(s) : NoneLEOW CHIA WAYNo ratings yet

- Healing Through MusicDocument11 pagesHealing Through MusicMiguel MacaroNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S1507136711000617 MainDocument3 pages1 s2.0 S1507136711000617 MainSofia AzevedoNo ratings yet

- Exploring The Effect of Sound and Music On Health in Hospital SettingsDocument3 pagesExploring The Effect of Sound and Music On Health in Hospital SettingsjuringNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Terapi Musik 3Document5 pagesJurnal Terapi Musik 3GITA WIBOWONo ratings yet

- Richardson Music TherapyDocument7 pagesRichardson Music TherapySofia AzevedoNo ratings yet

- Research Paper About Music TherapyDocument4 pagesResearch Paper About Music Therapyafeawldza100% (1)

- The Efficacy of Music Therapy: Judith H. Wakim, Edd, RN, Cne, Stephanie Smith, MSN, Crna, Cherry Guinn, Edd, RNDocument7 pagesThe Efficacy of Music Therapy: Judith H. Wakim, Edd, RN, Cne, Stephanie Smith, MSN, Crna, Cherry Guinn, Edd, RNRiley RilanNo ratings yet

- MTinMedicine DileoDocument10 pagesMTinMedicine DileoFernando OliveiraNo ratings yet

- Music Listening Alleviates Anxiety and Physiological Response in Patiens Receiving Spinal AnesthesiaDocument6 pagesMusic Listening Alleviates Anxiety and Physiological Response in Patiens Receiving Spinal AnesthesiaBobhy ErlankNo ratings yet

- Medical Student Well-Being: An Essential GuideFrom EverandMedical Student Well-Being: An Essential GuideDana ZappettiNo ratings yet

- Accidental Cure: Extraordinary Medicine for Extraordinary PatientsFrom EverandAccidental Cure: Extraordinary Medicine for Extraordinary PatientsNo ratings yet

- Effects of Music On Patient Anxiety: Esther MokDocument6 pagesEffects of Music On Patient Anxiety: Esther Mokwawawa017No ratings yet

- Hanser, Suzanne B - Integrative Health Through Music Therapy - Accompanying The Journey From Illness To Wellness-Palgrave Macmillan (2016)Document297 pagesHanser, Suzanne B - Integrative Health Through Music Therapy - Accompanying The Journey From Illness To Wellness-Palgrave Macmillan (2016)Camila Rocha Ferrari100% (1)

- The Effect of Music Therapy On Anxiety in Patients Who Are Terminally IllDocument10 pagesThe Effect of Music Therapy On Anxiety in Patients Who Are Terminally IllAldy Putra UltrasNo ratings yet

- Complementary Therapies in Clinical Practice: Caroline J. Hollins MartinDocument6 pagesComplementary Therapies in Clinical Practice: Caroline J. Hollins MartinReni Dwi FatmalaNo ratings yet

- MT Role Integrative Oncology - Magill 2006Document3 pagesMT Role Integrative Oncology - Magill 2006Aleja Medina MorenoNo ratings yet

- Music Therapy Strategies For WellnessDocument5 pagesMusic Therapy Strategies For WellnessDaniela RobayoNo ratings yet

- Effects of Music Therapy in Cardiac HealthcareDocument6 pagesEffects of Music Therapy in Cardiac HealthcareIona KalosNo ratings yet

- 0deec529c7b3b0379c000000 PDFDocument10 pages0deec529c7b3b0379c000000 PDFEmaa AmooraNo ratings yet

- Music Therapy Dissertation TopicsDocument8 pagesMusic Therapy Dissertation TopicsWhatIsTheBestPaperWritingServiceCanada100% (1)

- True Wellness for Your Heart: Combine The Best Of Western And Eastern Medicine For Optimal Heart HealthFrom EverandTrue Wellness for Your Heart: Combine The Best Of Western And Eastern Medicine For Optimal Heart HealthNo ratings yet

- The Use of Songs in Music Therapy With Cancer Patients and Their FamiliesDocument13 pagesThe Use of Songs in Music Therapy With Cancer Patients and Their FamiliesSofia AzevedoNo ratings yet

- A Soldier's GardenDocument44 pagesA Soldier's GardendarintwentyfourNo ratings yet

- Ajon Music Therapy PresentationDocument10 pagesAjon Music Therapy Presentationapi-383804230No ratings yet

- Tulio E. Bertorini - Neuromuscular DisordersDocument466 pagesTulio E. Bertorini - Neuromuscular DisordersLeila Gonzalez100% (1)

- Sound Healing: Vibrational Healing With Ohm Tuning Forks: A Practical Application ManualFrom EverandSound Healing: Vibrational Healing With Ohm Tuning Forks: A Practical Application ManualRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (7)

- Art I Go Me Salir A ImportanteDocument8 pagesArt I Go Me Salir A ImportanteEnderson MedeirosNo ratings yet

- Music and HealingDocument10 pagesMusic and HealingThiago PassosNo ratings yet

- Music Therapy: Treatment For Grade 11 Stem Students Who Suffer Stress From Basic CalculusDocument12 pagesMusic Therapy: Treatment For Grade 11 Stem Students Who Suffer Stress From Basic CalculusArvinel L. VileganoNo ratings yet

- Sleep Medicine and Mental Health: A Guide for Psychiatrists and Other Healthcare ProfessionalsFrom EverandSleep Medicine and Mental Health: A Guide for Psychiatrists and Other Healthcare ProfessionalsKarim SedkyNo ratings yet

- Music Intervention For Pain and AnxietyDocument37 pagesMusic Intervention For Pain and AnxietyVebryana RamadhaniaNo ratings yet

- Fulltext - Depression v2 Id1057 PDFDocument3 pagesFulltext - Depression v2 Id1057 PDFandra kurniaNo ratings yet

- Essential of Music TherapyDocument47 pagesEssential of Music TherapyShairuz Caesar Briones Dugay100% (2)

- Music Therapy Thesis StatementDocument5 pagesMusic Therapy Thesis StatementDon Dooley100% (2)

- Fullpapers DENTJ 38 1 11Document4 pagesFullpapers DENTJ 38 1 11Rizal Saeful DrajatNo ratings yet

- Migraine: Emerging Innovations and Treatment OptionsFrom EverandMigraine: Emerging Innovations and Treatment OptionsShalini ShahNo ratings yet

- Explainer - What Is Music TherapyDocument5 pagesExplainer - What Is Music TherapycomprensionlectoracartagenaNo ratings yet

- Effects of Music Therapy On Mood in Stroke Patients: Original ArticleDocument5 pagesEffects of Music Therapy On Mood in Stroke Patients: Original ArticleNURULNo ratings yet

- American Music Therapy Association, IncDocument4 pagesAmerican Music Therapy Association, IncPaolo BertoliniNo ratings yet

- What Is Music TherapyDocument20 pagesWhat Is Music Therapyeve sthNo ratings yet

- Music TherapyDocument7 pagesMusic Therapyzakir2012No ratings yet

- Music Therapy, Volume 4, Number 1, 1984Document13 pagesMusic Therapy, Volume 4, Number 1, 1984Eliso RammouNo ratings yet

- Hartnett - Aine Y4 Thesis Final 2Document33 pagesHartnett - Aine Y4 Thesis Final 2Mike LNo ratings yet

- Music Therapy Thesis IdeasDocument6 pagesMusic Therapy Thesis Ideasykramhiig100% (2)

- Essentials of Radiofrequency Ablation of the Spine and JointsFrom EverandEssentials of Radiofrequency Ablation of the Spine and JointsNo ratings yet

- 15 Music Therapy Activities and ToolsDocument13 pages15 Music Therapy Activities and ToolsNadeem IqbalNo ratings yet

- Music TherapyDocument45 pagesMusic TherapyAlaa OmarNo ratings yet

- 1.1 How Music Therapy Works? (CITATION Cra19 /L 1033)Document5 pages1.1 How Music Therapy Works? (CITATION Cra19 /L 1033)Drishti JoshiNo ratings yet

- Music As A Complementary Therapy in Medical Treatm PDFDocument8 pagesMusic As A Complementary Therapy in Medical Treatm PDFkiranaNo ratings yet

- CEO Speaks 28th JuneDocument2 pagesCEO Speaks 28th Junesoumyadipta.technojalpaiguriNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Terapi Musik 4 InggrisDocument8 pagesJurnal Terapi Musik 4 InggrisExtensi 2 STIKes MKNo ratings yet

- Music, Sound, and Vibration: Music and Science Integrated CurriculumFrom EverandMusic, Sound, and Vibration: Music and Science Integrated CurriculumNo ratings yet

- NajahAhmadv ConsistCollegeSdnBhd (2019) 2LNS1301Document14 pagesNajahAhmadv ConsistCollegeSdnBhd (2019) 2LNS1301Angel YakNo ratings yet

- Industrial Court Case 1Document36 pagesIndustrial Court Case 1Angel YakNo ratings yet

- KMS3084 EL (Industrial Practitioner Reflection)Document1 pageKMS3084 EL (Industrial Practitioner Reflection)Angel YakNo ratings yet

- Scoring Guide - SOSDocument3 pagesScoring Guide - SOSAris Nur AzharNo ratings yet

- Sos 2001Document1 pageSos 2001Angel YakNo ratings yet

- Music Therapy ResearchDocument7 pagesMusic Therapy ResearchALEXNo ratings yet

- KMC4023 Interview QuestionsDocument2 pagesKMC4023 Interview QuestionsAngel YakNo ratings yet

- Admin Circular 12-Service of SummonsDocument1 pageAdmin Circular 12-Service of SummonsbbysheNo ratings yet

- Speakout Language BankDocument7 pagesSpeakout Language BankСаша БулуєвNo ratings yet

- Tutorial Getting Started With Code Aster PDFDocument12 pagesTutorial Getting Started With Code Aster PDFEnriqueNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2Document14 pagesChapter 2Um E AbdulSaboorNo ratings yet

- Uttar Pradesh Universities Act 1973Document73 pagesUttar Pradesh Universities Act 1973ifjosofNo ratings yet

- CR Injector Repair Kits 2016Document32 pagesCR Injector Repair Kits 2016Euro Diesel100% (2)

- Accenture 172199U SAP S4HANA Conversion Brochure US Web PDFDocument8 pagesAccenture 172199U SAP S4HANA Conversion Brochure US Web PDFrajesh2kakkasseryNo ratings yet

- VW Golf 2 Sam Naprawiam PDFDocument3 pagesVW Golf 2 Sam Naprawiam PDFScottNo ratings yet

- Effect of Boron Content On Hot Ductility and Hot Cracking TIG 316L SSDocument10 pagesEffect of Boron Content On Hot Ductility and Hot Cracking TIG 316L SSafnene1No ratings yet

- Oral Communication in Context Quarter 2: Week 1 Module in Communicative Strategies 1Document10 pagesOral Communication in Context Quarter 2: Week 1 Module in Communicative Strategies 1Agatha Sigrid GonzalesNo ratings yet

- Summary of All Sequences For 4MS 2021Document8 pagesSummary of All Sequences For 4MS 2021rohanZorba100% (3)

- Marriage and Divorce Conflicts in The International PerspectiveDocument33 pagesMarriage and Divorce Conflicts in The International PerspectiveAnjani kumarNo ratings yet

- Analgesic ActivityDocument4 pagesAnalgesic ActivitypranaliankitNo ratings yet

- PHNCDocument6 pagesPHNCAmit MangaonkarNo ratings yet

- 5568 AssignmentDocument12 pages5568 AssignmentAtif AliNo ratings yet

- What If The Class Is Very BigDocument2 pagesWhat If The Class Is Very BigCamilo CarantónNo ratings yet

- InvestMemo TemplateDocument6 pagesInvestMemo TemplatealiranagNo ratings yet

- Exercise and Ppismp StudentsDocument6 pagesExercise and Ppismp StudentsLiyana RoseNo ratings yet

- Ra 9048 Implementing RulesDocument9 pagesRa 9048 Implementing RulesToffeeNo ratings yet

- Digital Signal Processing AssignmentDocument5 pagesDigital Signal Processing AssignmentM Faizan FarooqNo ratings yet

- Case Study Method: Dr. Rana Singh MBA (Gold Medalist), Ph. D. 98 11 828 987Document33 pagesCase Study Method: Dr. Rana Singh MBA (Gold Medalist), Ph. D. 98 11 828 987Belur BaxiNo ratings yet

- Mamaoui PassagesDocument21 pagesMamaoui PassagesSennahNo ratings yet

- Newton's Second LawDocument3 pagesNewton's Second LawBHAGWAN SINGHNo ratings yet

- 17PME328E: Process Planning and Cost EstimationDocument48 pages17PME328E: Process Planning and Cost EstimationDeepak MisraNo ratings yet

- PM-KISAN: Details of Eligible and Ineligible FarmersDocument2 pagesPM-KISAN: Details of Eligible and Ineligible Farmerspoun kumarNo ratings yet

- M40 Mix DesignDocument2 pagesM40 Mix DesignHajarath Prasad Abburu100% (1)

- Urban Design ToolsDocument24 pagesUrban Design Toolstanie75% (8)

- Speech VP SaraDocument2 pagesSpeech VP SaraStephanie Dawn MagallanesNo ratings yet

- Eaap Critical Approaches SamplesDocument2 pagesEaap Critical Approaches SamplesAcsana LucmanNo ratings yet

- TestFunda - Puzzles 1Document39 pagesTestFunda - Puzzles 1Gerald KohNo ratings yet