Professional Documents

Culture Documents

(2015) End-Of-Life-Care-Research-In-Hong-Kong-A-Systematic-Review-Of-Peer-Reviewed-Publications

Uploaded by

charmyshkuOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

(2015) End-Of-Life-Care-Research-In-Hong-Kong-A-Systematic-Review-Of-Peer-Reviewed-Publications

Uploaded by

charmyshkuCopyright:

Available Formats

Palliative and Supportive Care (2015), 13, 1711 –1720.

# Cambridge University Press, 2015 1478-9515/15

doi:10.1017/S1478951515000802

End-of-life care research in Hong Kong: A systematic

review of peer-reviewed publications

CHONG-WEN WANG PH.D., AND CECILIA L.W. CHAN, PH.D.

Centre on Behavioral Health, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong

(RECEIVED April 6, 2015; ACCEPTED April 15, 2015)

ABSTRACT

Objective: This systematic review aimed to examine end-of-life (EoL) care research undertaken

in an Eastern cultural context—Hong Kong—with the hope of better informing EoL care

professionals and policy makers and providing lessons for other countries or areas that share

similar EoL care challenges.

Method: Eight databases were searched from their respective inception through to August of

2014. All of the resulting studies conducted in Hong Kong and relevant to EoL care or palliative

care were examined. The included studies were assessed with respect to study design, care

settings, participants, research themes, and major findings.

Results: Some 107 publications published between 1991 and 2014 were identified. These

studies were undertaken at a range of places by different professionals. Of the total, 44 were led

by physicians, 36 by nurses, 17 by social workers, and 10 by other professionals. Participants

included both inpatients and outpatients with different illnesses, nursing home residents, older

community-dwelling adults, deceased individuals, care staff, and informal caregivers. A total of

13 research themes were identified: (1) attitudes to or perceptions of death and dying; (2)

utilization of healthcare services, (3) physical symptoms or medical problems; (4) death anxiety

or mental health issues; (5) quality of life; (6) advance directives or advance care planning; (7)

supportive care needs, (8) decision making; (9) spirituality; (10) cost-effectiveness or utility

studies; (11) care professionals’ education and training; (12) informal caregivers’ perceptions

and experience; and (13) scale development or validation.

Significance of results: While there has been a wide and diverse range of research activities in

Hong Kong, EoL care services at primary care settings should be strengthened. Some priority

areas for further research are recommended.

KEYWORDS: End of life, Palliative care, Research, Systematic review, Hong Kong

INTRODUCTION care quality, knowledge and skills, competency, deci-

sion making, and psychosocial and spiritual con-

EoL care is an important aspect of healthcare

cerns. Given the nature of terminal illnesses,

worldwide that is becoming increasingly more vital

palliative care rather than curative care at the end

and is emphasized by healthcare and social care

of life has been highlighted and promoted in recent

professionals, dying persons, family members, and

years, which is an approach that can improve the

the general public (Department of Health, 2008).

quality of life (QoL) of patients and their families fac-

However, many issues and challenges may exist

ing the problems associated with a life-threatening

in providing quality EoL care to individuals with a

illness through prevention and relief of suffering as

terminal illness, including accessibility, coverage,

well as treatment of pain and other physical, psycho-

social, and spiritual problems (WHO, 2002). With the

Address correspondence and reprint requests to: Chong-Wen rapidly aging population, improving EoL care has be-

Wang, Centre on Behavioral Health, The University of Hong

Kong, 5 Sassoon Road, Pokfulam, Hong Kong. E-mail: wangcw@ come a priority of public policy and healthcare strat-

hku.hk egies in many countries (Department of Health,

1711

https://doi.org/10.1017/S1478951515000802 Published online by Cambridge University Press

1712 Wang & Chan

2008; 2011; Giovanni, 2012), not so much from a cost “terminal care,” “end-of-life care,” “advance directive,”

perspective but more in terms of quality (Carlson, “advance care plan,” “dying,” “death,” “end of life,”

2010). “terminal,” “terminally ill,” “palliative,” “hospice,”

Hong Kong is a highly developed metropolitan “Chinese,” and “Hong Kong.” We searched the elec-

area. However, a report by the Economist Intelli- tronic databases for titles and abstracts containing

gence Unit (2010) indicates that the quality of death these terms. No limits were imposed on participant

in Hong Kong ranks 20th among 40 selected loca- characteristics, research design, outcome measures,

tions from around the world. So there is plenty of or language. In addition, Google Scholar was searched

room for improvement. Hong Kong is also embracing using Chinese translations of the aforementioned

a rapidly aging population with limited resources. terms for relevant articles published in Chinese. The

The number of persons aged 65 and above accounts reference lists of all included studies and other

for 13% of its population, and this number is expected archives of the located publications were searched by

to increase to 30% by 2041 (Census and Statistics De- hand for further relevant articles.

partment, 2014). Compared to 2011, Hong Kong’s el-

derly dependency ratio will double by the year 2026 Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

(18.8 vs. 37.5%) and almost triple by the year 2041

Given the volume of documents initially generated,

(54.9%) (Cheng et al., 2013). Demand for long-term

the search was restricted to full-text articles that

care services will rise considerably for the foresee-

were published or might be published in peer-

able future (Social Work Department, 2013). In-

reviewed journals. Publications were selected based

creased numbers of older persons and extended life

on the following inclusion criteria: (1) original stud-

expectancy coupled with the impact of chronic illness

ies relevant to EoL care or palliative care; (2) studies

on individuals’ physical, psychological, and social

conducted among Chinese participants in Hong

well-being suggest that the demand for EoL pallia-

Kong; (3) unpublished theses examined by reviewers;

tive care services will increase not only in terms of

and (4) research outputs with either qualitative or

quantity but also quality (Williams et al., 2010).

quantitative data. In order to maximize the type

Though there are many cases of clinically relevant,

and range of relevant research, studies drawing on

collaborative, interdisciplinary, and strategic ap-

subsamples in Hong Kong were also included. The

proaches to palliative care research in Hong Kong,

exclusion criteria included: (1) nonoriginal publica-

this information is greatly fragmented. To inform

tions such as editorials, commentaries, newsletters,

evidence-based practice and policy making, an exam-

literature reviews, and discussion documents; (2) bi-

ination of the available evidence generated from sci-

omedical studies; (3) studies on animals; (4) studies

entific research conducted in the region seems

on mortality and associated factors; (5) studies nei-

necessary, since the state of EoL care research is

ther related to death and dying nor caregiving; (6)

closely linked to the development of EoL care services

studies on bereavement or grief that occurred after

(Sigurdardottir et al., 2010).

death; (7) studies conducted among Chinese outside

The purpose of our review was thus to provide a

of Hong Kong; (8) case reports or conference proceed-

systematic and thematic analysis of peer-reviewed

ings; and (9) duplicates.

journal articles that describe EoL care or palliative

care studies undertaken in Hong Kong and to exam-

Data Extraction

ine the characteristics of the studies in terms of

venue, sample, research methodology, and outcomes. All references generated through the searches were

Not only would such an analysis be helpful for exported into EndNote, and duplicates were elimi-

improving EoL care services and identifying priority nated. The titles and abstracts were manually re-

areas for future research, but the findings may pro- viewed. Irrelevant items were excluded according to

vide lessons for other regions or nations that share the exclusion criteria. If a reference was potentially

similar EoL care challenges. eligible for inclusion, the full text was retrieved for

further screening. For each of the included studies,

data were extracted onto a customized data-extraction

METHODS

sheet, including the following information: research

aims, study design, participants, sample size, outcome

Search Strategy

measures (where applicable), and major findings.

The following electronic databases were searched The included studies were categorized according to

from their respective inception through August of the types of study design, samples, and outcomes

2014: AMED, CINAHL, PubMed, MEDLINE, SocIN- or research themes. Given that some studies

DEX, PsychINFO, and Web of Science. The search may have had multiple themes, the primary aim

terms used included: “palliative care,” “hospice care,” and major outcomes of the study were utilized for

https://doi.org/10.1017/S1478951515000802 Published online by Cambridge University Press

End-of-life care research in Hong Kong 1713

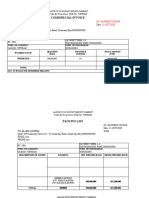

Fig. 1. Selection process for included studies.

categorization. A very few studies were allocated into and focus-group interviews. The vast majority of

multiple categories. Where uncertainty existed, the included studies were descriptive. Such studies in-

full text of the article was carefully reexamined and cluded qualitative studies, cross-sectional surveys,

recategorized. longitudinal surveys, retrospective data analyses,

and clinical data mining. Some 19 studies evaluated

the effectiveness of different intervention or educa-

RESULTS

tion programs, of which 9 focused on healthcare

Our searches identified 595 potentially relevant pub- delivery or services, 5 on supportive care, 2 on

lications, and 452 records were removed after screen- psychoeducation, and 3 on education and training.

ing the titles and abstracts. Full reports of 143 These studies included single-arm studies, con-

publications pertaining to EoL care or palliative trolled trials, some retrospective studies or audits,

care issues were acquired, and 36 articles were fur- and a few qualitative studies.

ther excluded as they were nonoriginal publications, A range of samples were investigated in the in-

studies not related to EoL care, or studies outside of cluded studies, including both inpatients and outpa-

Hong Kong. Consequently, 107 articles were included tients with different illnesses (most of the studies

for the final review (Figure 1). focused on cancer and a small number on noncancer

Figure 2 depicts the number of publications in dif- illnesses, including end-stage renal disease, chronic

ferent years. Of the included studies, 44 were led by obstructive pulmonary disease, and acute myeloid

physicians, 36 by nurses, 17 social workers, and 10 leukemia), care home residents, older community-

by other professionals (including psychologists, dwelling adults, deceased individuals, healthcare

physical therapies, occupational therapies, and professionals or students, and family caregivers

counselors) (Figure 3). In terms of research design, (Table 2). There was wide variation in terms of sam-

72 studies were quantitative and 30 qualitative ple size. For qualitative studies, sample sizes ranged

in nature (Table 1). Five studies were conducted from 6 to 96, with a median of 23. For quantitative

with mixed methods. Questionnaire surveys and studies, the sample sizes ranged between 10 and

clinical records were the primary quantitative re- 2874, with a median of 121. These studies were

search methods employed, while the most frequent- undertaken in a broad spectrum of settings, includ-

ly employed qualitative methods were individual ing hospitals, hospice units, nursing homes, care

https://doi.org/10.1017/S1478951515000802 Published online by Cambridge University Press

1714 Wang & Chan

Fig. 2. Number of publications in different years.

homes, the community or homes, and generalist and reported the presence of suicidality (Cheng et al.,

specialist services. 2014a). Some patients might be situated in a “sup-

Table 3 presents the research themes that port paradox,” in which they desire family support

emerged in the included studies, which were based but also worry about care burden on family members

on research focuses and primary outcome measures. (Chan et al., 2009). Some 12 studies examined the

As can be seen, 13 themes could be identified. Specif- QoL of patients with terminal illnesses in different

ically, 18 studies examined physical symptoms or settings. Overall, the results indicated substantially

medical/functional problems, with pain and fatigue impaired quality of life among terminally ill patients,

being the two most common symptoms. Some 14 with two domains (physical symptoms and existen-

studies examined older adults’ attitudes to or percep- tial distress) scoring particularly low (Yan & Cheng,

tions about death and dying, most with a qualitative 2006). Four additional studies focused on validation

research design. The research concepts emerged in of QoL or psychological well-being scales.

these studies included “good death,” “dying with dig- Nine studies examined the preference for advance

nity,” “expected beneficial outcomes from palliative directives (ADs) or advance care planning (ACP)

care,” “end-of-life choices,” “life-sustaining treat- among institutionalized and noninstitutionalized

ments,” and “emotional states.” Nine studies exam- older persons and medical students. The findings

ined death anxiety or mental health problems suggested that 96% of nursing home residents (Chu

among terminally ill patients or community-dwelling et al., 2011a) and 81% of elderly inpatients with

older adults. The findings indicated that cancer pa- chronic disease (Ting & Mok, 2011) had not previous-

tients had either very high or very low death anxiety ly heard of the term “advance directive.” However,

levels (Ho & Shiu, 1995). A high level of death anxi- 87.9% of nursing home residents preferred to have

ety was associated with younger age (Wu et al.,

2002). Patients who did not have a clear awareness

of their prognosis were more likely to experience anx- Table 1. Research methods applied in the included

iety and difficulty communicating with family mem- studies

bers (Chan, 2011). Depressive symptoms were

evident among 43.9% of the patients. Up to 46.3% Study Design Number of Studies

Qualitative study 30

Quantitative study 77*

Cross-sectional survey 31

Longitudinal survey 6

Prospective study 5

Clinical data mining 5

Retrospective study 19

or clinical data analysis

Single-arm trial 6

Controlled clinical trial 4

Fig. 3. Number of studies led by different care professionals. *Including five studies with mixed-methods design.

https://doi.org/10.1017/S1478951515000802 Published online by Cambridge University Press

End-of-life care research in Hong Kong 1715

Table 2. Participants in the included studies A total of 14 studies examined healthcare staff

and students’ knowledge, beliefs, and experiences.

Number of The research themes merged in the field included a

Participants Studies problem-based learning approach for nurse students,

Cancer patients 42* the experiences of nurses caring for dying patients,

Noncancer patients with 5* nurse –patient relationships, medical students’ atti-

chronic illnesses tudes toward EoL decisions, knowledge and attitudes

Patients with end-stage renal 7 of all ranks of old age home staff (nurses, physiother-

disease

Patients with dementia 2 apists, occupational therapists, and social workers),

Patients with chronic obstructive 1 beliefs about death and dying or EoL care preferences

pulmonary disease among social work students, and the emotional com-

Patients with acute myeloid leukemia 1 petence of social workers. Seven studies examined

Nursing home or long-term 14 the experience or perceptions of family caregivers of

care residents

Deceased individuals 7 patients with a terminal illness. Other research

Community older adults 5 themes included supportive care needs, decision

Care professionals 17 making, spirituality, and cost-effectiveness (Table 3).

Family caregivers 9

*Including three studies on both cancer and noncancer DISCUSSION

patients. Our systematic review was the first to summarize EoL

care research conducted within an Eastern cultural

ADs regarding future medical treatment (Chu et al., context. The results of this review will add additional

2011a; 2011b), and 78% of community-dwelling older information to the findings of a recent pan-European

persons with multiple medical problems accepted survey across 41 countries (Sigurdardottir et al.,

ACP (Tsang et al., 2013). About half (49%) of elderly 2010) and a systematic review of palliative care re-

inpatients with chronic disease said they would con- search in Ireland, where the quality of death ranks

sider using an AD if it was legalized in Hong Kong fourth globally (McIlfatrick & Murphy, 2013).

(Ting & Mok, 2011). Among patients with advanced In our review, a diverse range of research activities

malignancy who were newly referred to the hospice relevant to EoL care were identified. These research

service (Wong et al., 2012), 63% had ADs, while activities were undertaken at different locations, us-

37% did not. The vast majority of medical students ing a range of methods, for varied subjects, with a

(90%) felt that their knowledge of ADs was inade- wide range of outcome measures. This diversity is in-

quate, and 90% of students felt unprepared to deal dicative of the different disciplines involved in EoL

with ADs and EoL issues (Siu et al., 2010). care research. Such diversity could be considered as

a strength rather than a weakness (McIlfatrick &

Table 3. Research themes that emerged from the Murphy, 2013). With a mixture of findings and per-

included studies spectives from different disciplines, evidence-based

policy making might be better informed, evidence-

Outcomes or research themes Number of Studies based guidelines to inform clinical practice could be

Physical symptoms or functional 18

developed, and healthcare services and social re-

problems sources could be mobilized.

Attitudes to or perceptions of death 14

and dying EoL Care Research in Hospital Settings

Utilization of healthcare services 13

Quality of life 12 Our review indicated that palliative care services

Death anxiety or mental health 9 played an important role in improving EoL care in

problems

Advance directives or ethical issues 9 Hong Kong and had been successful in maintaining

Supportive care needs 2 patients’ QoL during the process of dying since the de-

Decision making 2 velopment of the local hospice service in 1987 (Tse

Spirituality 2 et al., 2007; Lo et al., 2002). Seven strategies were im-

Cost-effectiveness and utility studies 2 plemented between 2004 and 2009 to optimize the use

Care staff and students’ knowledge, 14

beliefs, and experiences of inpatient beds due to the increasing need for palli-

Informal caregivers’ perceptions and 7 ative care services (Lam et al., 2011). An integrated

experience EoL care pathway modified from the Liverpool Care

Scale validation or development 4 Pathway for the Dying Patient was implemented in

Hong Kong in 2007. It improved the quality of care

https://doi.org/10.1017/S1478951515000802 Published online by Cambridge University Press

1716 Wang & Chan

in both palliative care units (Lo et al., 2009) and acute- are often avoided because of the fear that such discus-

care hospital settings (Siu et al., 2011). A collaborative sions could hasten the pace of dying or cause death

model of care was established in 2011 between the prematurely (Xu, 2007). It goes without saying that

acute geriatrics unit and the palliative medical unit this taboo may be a barrier to delivering EoL care in

in response to the growing palliative care needs the community. Consequently, many of the included

among older adults (Cheng et al., 2014b). studies conducted in the community focus on the atti-

According to a study conducted in 2010, palliative tudes to or perceptions about death and dying. The

care services covered 79.2% of cancer patients but findings of these studies may be essential to finding

only 1.4% of noncancer patients in Hong Kong (Lau the best way to change people’s attitudes and beliefs

et al., 2010). Compared to some other countries, pal- and improve the quality of dying and death.

liative care for noncancer patients lags far behind in Unlike other countries, where the proportions of

Hong Kong (Lau et al., 2010). In the United States, death and dying occurring at home range from 17%

63.1% of hospice admissions in 2012 were noncancer in Japan to 89% in Albania (Broad et al., 2013), few

patients (National Hospice and Palliative Care Orga- natural and expected deaths occur at home in Hong

nization, 2013). In the United Kingdom, noncancer Kong. There are various potential barriers to individ-

diagnoses accounted for 11% of all hospice admis- uals dying at home here, including the crowded living

sions in 2011 – 2012 (National Council for Palliative environment, the perceived threat to real estate val-

Care, 2013). There seems to be a pressing need to de- ues if death occurs at home, and social and cultural

velop palliative care services for terminally ill non- taboos (Luk et al., 2011), not to mention legal encum-

cancer patients in Hong Kong. Given the greater brances (Tong, 2014). Accordingly, studies on deliver-

prevalence of chronic terminal illnesses with extend- ing EoL care in the home setting and relevant

ed dying trajectories, such measures could economize supportive care programs are very limited in Hong

the use of healthcare resources. Though there are Kong. In 2000, Wong and colleagues (2004) launched

some practical barriers to implementing palliative a home care program from a hospital palliative care

care for patients with noncancer terminal illnesses, unit. Some 32 dying patients were recruited who

it may be possible to improve the quality of EoL were receiving home care and were followed until

care for these patients by means of staff education death. Their physical symptoms were generally well

and training, formulation of practical guidelines, es- controlled, while the psychological aspects caused

tablishment of care pathways, and systemic changes, the most concern for patients, families, and health-

without expenditure of additional resources (Woo care professionals. The mean number of home visits

et al., 2011a; 2011b). None of the included studies fo- was 6.1, with a range of 1–21 and a mean time spent

cused on EoL care for children, younger adults, or on each patient of 9.9 hours (range 2–38). However,

persons with intellectual disabilities or psychiatric few such programs or similar studies have been re-

illnesses. Further studies on specific groups of people ported since then. In recent years, some palliative

with life-limiting illnesses are certainly warranted. home visits and palliative day care services have

In Hong Kong, nearly all older adults with termi- been provided by the Hospital Authority of Hong

nal diseases received EoL care in hospital settings, Kong. The conditions under which these services

and most of them died at the hospital (Chu et al., were provided and the problems for which the home

2011b). This situation may be unique. According to visits and day care services were offered remain

a systematic review, the proportions of dying and poorly understood, though. It is also unclear whether

deaths occurring at hospitals in other countries these services met the EoL care needs or demands in

range from 11% in Albania to 78% in Japan (Broad the home settings. More study of these aspects is

et al., 2013). Given the high cost of medical care definitely required.

and the increased burden induced by the aging pop-

ulation, the hospital-inclined model of EoL care

EoL Care Research in Residential Care

may not be sustainable. Perhaps it will be necessary

Settings

for the government of Hong Kong to make an effort to

reduce the proportion of hospital deaths. Currently, about 7% of the older population in Hong

Kong is cared for in residential care homes (Census

and Statistics Department, 2009). These patients

EoL Care Research in the Community

tend to be frail, with multiple comorbidities, depen-

In traditional Chinese society, death is a taboo subject. dent, and cognitively impaired (Woo & Chau, 2009).

It is believed that talking about death in daily life, However, 33.5% of all deaths are care home residents

mentioning it in conversation, and sharing fears of (Hospital Authority of Hong Kong, 2013). Unlike oth-

death may bring bad luck (Xu, 2007; Hsu, 2009). er countries, the laws of Hong Kong have made dying

Even for those who are dying, discussions about death at home the exception rather than the rule, and care

https://doi.org/10.1017/S1478951515000802 Published online by Cambridge University Press

End-of-life care research in Hong Kong 1717

home residents usually die in hospital (Tong, 2014). rective” is a term generally used in medical settings

As a result, as death approaches or one’s physical to refer to decision making on such life-sustaining

condition becomes unstable, the resident undergoes therapies as cardiopulmonary resuscitation, artifi-

frequent transitions between hospital and care facil- cial ventilation, oral or intravenous antibiotics, and

ity (Lee et al., 2013). The residents are usually trans- artificial fluids or nutrition. “Advance care planning”

ferred to emergency rooms and then acute medical is a concept that allows individuals to choose whether

wards, followed by transfer to an extended-care or not to be hospitalized (Silveira et al., 2014). Ac-

unit if indicated. A new model has been introduced cording to ACP, individuals can decide how they are

recently, where older nursing home residents are to be cared for, where they are to be cared for, and

transferred to an extended-care unit either directly where they will die. Of the nine relevant studies

through liaison with the Community Geriatrics Out- examined in our review, most focused on ADs. A

reach Service (pathway A) or from the emergency form of ACP was recently introduced in Hong Kong

room (pathway B) according to their advance care where the patient is given a choice of whether or

plans. The evidence indicates that 39% could be ad- not to be transferred to an acute-care hospital in

mitted to the extended-care unit through the new case of deterioration while residing in a care facility

pathways, with their survival and quality of care un- (Hui et al., 2014).

compromised and intact (Hui et al., 2014). A law regulating ADs has been available for more

In Hong Kong, about 35% of respondents prefer than two decades in such countries as Australia,

EoL care or to die in their care homes (Chu et al., Canada, the United Kingdom, the United States,

2011a; 2011b; 2014). EoL care service in the care and Singapore (Chu et al., 2011a; 2011b; Ting &

home setting was begun in Hong Kong in 2000 Mok, 2011). However, there is no case law on the va-

(Chu et al., 2013). The average length of stay in hos- lidity of an AD in Hong Kong (Chu et al., 2011a). Con-

pital during the last 30 days of life was only 1.3 days sequently, relevant studies conducted in Hong Kong

for residents receiving EoL care, compared to an av- focus only on knowledge, attitudes, and preference

erage of 16 days for residents not receiving EoL for ADs or ACP. In the United States, the proportion

care (Chu et al., 2013). Unfortunately, EoL care ser- of decedents with an AD has increased from 47% in

vices have not yet been generalized among care 2000 to 72% in 2010 (Silveira et al., 2014). However,

homes in Hong Kong. Well-known barriers to good awareness of ADs or ACP is still poor among the el-

EoL care in the care home setting include inadequate derly population of Hong Kong, as demonstrated in

staffing; a lack of supervision; inadequate knowledge our review. More programs and research on promo-

regarding EoL care issues among staff, residents, tion and implementation of the concepts of ADs and

and family members; and interference caused by ACP in different patient groups and for different

the personal attitudes and beliefs of staff members end-stage illnesses are surely necessary. Apart from

about death and dying (Lee et al., 2013; Lo et al., studying the uptake and associated contributory fac-

2010; Mak et al., 2013). Both the availability of a doc- tors for ADs, the effectiveness of AD implementation

tor and the attitudes of nursing home staff members strategies and their impact on hospitalizations and

are also important factors (Chu et al., 2014). To date, medical expenditure should be investigated (see

intervention or education programs to overcome Chu, 2012). Because of the uncertainty with ADs,

these barriers are still limited. More relevant studies many patients and older adults are uncertain about

are warranted. Appropriate health policy to promote their end-of life care preferences and prefer their

implementation of community EoL care among elder- physician to be their surrogate (Chan & Pan, 2007),

ly people living in subsidized old age homes are also which places a great burden on physicians. There is

needed. A local study suggested that the early (28 a need to reconsider AD legislation to facilitate im-

days) unplanned readmission rate to acute medical plementation of the practice among older adults or

units of public hospitals among institutionalized patients with a terminal illness in Hong Kong. This

older people is twice (36 vs. 18%) that of those living would constitute a major step toward improving

in the community (Hui et al., 2014). Developing EoL and promoting the quality and dignity of death and

care programs in care home settings could lead to a dying.

large reduction in unplanned hospital readmissions

and lowered hospital care costs (Chu et al., 2011b).

Family Caregivers and Care Staff

The evidence indicated that 95% of informal caregiv-

ADs and ACP

ers in Hong Kong perceive difficulties in rendering

Most EoL care preferences can be indicated in ad- care for terminally ill patients (Loke et al., 2003),

vance in the form of ADs or ACP. ADs and ACP are and the younger the caregiver, the more difficulty

two different but overlapping concepts. “Advance di- he or she may experience (Chan & Chang, 2000).

https://doi.org/10.1017/S1478951515000802 Published online by Cambridge University Press

1718 Wang & Chan

Although traditional filial beliefs provide motivation used different terminology in their titles and abstracts

for family caregiving, the regrets that come with un- but were in fact relevant. Another limitation of our

fulfilled filial responsibilities may create emotional review may be that exclusion of non-peer-reviewed

distress among adult Chinese caregivers (Chan publications may have resulted in over- or underrepre-

et al., 2012). The evidence also indicated insufficient sentation of certain themes. Such limitations are also

knowledge and skills necessary for palliative care notable in other reviews (McIlfatrick & Murphy,

among some care staff and relevant students. Thus, 2013).

more supportive programs for family caregivers and

educational programs for relevant care staff, espe-

cially those working in care homes, are certainly

CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

required.

Our review not only demonstrated a wide and di-

Methodological Issues for the Included verse range of research activities related to EoL

Studies care, but it also indicated that EoL care services

at primary care settings are underdeveloped in

Among the included studies, some methodological Hong Kong. As reported by the Economist Intelli-

issues were identified. First, most of the included gence Unit (2010), the quality of EoL care in Hong

studies were descriptive. Of the limited number of Kong is quite good, but the scores on three other in-

intervention-oriented studies, many were conducted dicators (basic EoL care environment, availability of

without a control group. The number of randomized EoL care, and cost of EoL care) of the Quality of

controlled trials was particularly limited (only two). Death Index were much lower. With a growing el-

Second, there was a wide variation in sample size derly population, an increase in the prevalence of

among the included studies, and few of them justi- chronic illness, and increased medical expenditures,

fied the small sample size. Small samples most like- the care burden on our healthcare system is increas-

ly are not representative, and the results obtained ing rapidly. There is a pressing need to move from a

are often biased. Third, there was a significant dif- hospital-inclined model to a community-shared

ference in care delivery related to the nature of model of care so as to design an integrated EoL

the samples in studies conducted in different set- care system involving hospitals, the long-term care

tings by different professionals. Unlike the overem- sector, and families. Although EoL care services in

phasis on needs-based palliative care research in primary care settings are also underdeveloped in

Ireland (McIlfatrick & Murphy, 2013), the number European countries (Murray et al., 2015) and in oth-

of needs-based EoL care studies (especially in pri- er regions, the challenges may be significantly

mary care settings) seems to be insufficient in greater in Hong Kong because of its lack of infra-

Hong Kong. Studies on the economic aspects are structure and the cultural barriers. The increased

also limited. Finally, numerous outcomes were as- need for EoL palliative care will result in a greater

sessed with a range of measures. This is a strength need for research in this area.

for the research agenda as a whole but a limitation On the basis of evidence summarized in the pre-

for psychosocial and mental health studies. Some sent review, several research priorities specific to

psychometric outcome measures may not be cultur- EoL care in Hong Kong are recommended. First,

ally sensitive, as they were developed in a Western there is a need to initiate studies to establish models

cultural context. Thus, interpretation of the results and components of EoL care in the community in

of particular studies should be undertaken cau- order to improve service delivery and optimize the

tiously. Recognized standard, valid, culturally appli- quality of life and quality of death for terminally ill

cable, and reliable measures are required for patients. Second, there is a need for studies to explore

further studies. the best strategies for collaboration between the med-

ical and social care sectors. Third, more vigorously

designed evaluation studies or interventional pro-

LIMITATIONS OF THIS REVIEW

grams are needed in order to provide reliable scien-

In our systematic review, study quality was not tific evidence. In addition, studies on the economics

ranked for the included studies due to the heteroge- of EoL care are also warranted, as the importance

neity of research designs. We regarded the quality of the economic aspects of EoL care research cannot

of all included studies, however, as acceptable since be underestimated. This is of great significance with-

they were published after going through the peer- in the context of rising healthcare costs. Finally, fu-

review process. A major limitation of our review ture studies could extend palliative care services to

may be that the keywords we employed to select pub- the earlier stages of terminal illness and for a wider

lications may not have captured all the studies that range of conditions.

https://doi.org/10.1017/S1478951515000802 Published online by Cambridge University Press

End-of-life care research in Hong Kong 1719

CONFLICTS OF INTERESTS Chu, L.W., Luk, J.K., Hui, E., et al. (2011a). Advance direc-

tive and end-of-life care preferences among Chinese

The authors hereby state that they have no conflicts nursing home residents in Hong Kong. Journal of the

of interest to declare. American Medical Directors Association, 12, 143– 152.

Chu, L.W., McGhee, S.M., Luk, J.K., et al. (2011b). Advance

directives and preference of old age home residents for

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS community model of end-of-life care in Hong Kong.

Hong Kong Medical Journal, 17(Suppl. 3), 13–15.

No funding was received for our study. The authors would Chu, L.W., So, J.C., Wong, L.C., et al. (2014). Community

like to thank Dr. Rainbow Ho and Dr. Christine Fang end-of-life care among Chinese older adults living in

for their support and to acknowledge the assistance of nursing homes. Geriatrics & Gerontology International,

Ms. Yee-Wa Hong for searching the electronic databases. 14(2), 273 – 284.

Chu, W.W. & Christine, Y. (2013). Evaluation of end-of-life

care service in a nursing home in Hong Kong, 2000–

REFERENCES 2013: The clinical profile and hospital utilization. Asia

Pacific Regional Conference on End-of-Life and Pallia-

Broad, J.B., Gott, M., Kim, H., et al. (2013). Where do peo- tive Care in Long-Term Care Settings.

ple die? An international comparison of the percentage Department of Health (2008). End-of-life care strategy:

of deaths occurring in hospital and residential aged Promoting high-quality care for all adults at the end of

care settings in 45 populations, using published and life. London: Department of Health.

available statistics. International Journal of Public Department of Health and Ageing (2011). Supporting Aus-

Health, 58, 257 –267. tralians to live well at the end of life: National Palliative

Carlson, J. (2010). Not finished yet: Coalition wants end-of- Care Strategy 2010. Canberra: Department of Health

life care to be a priority. Modern Healthcare, 40, 17. and Ageing.

Census and Statistics Department (2014). Hong Kong Economist Intelligence Unit (2010). The quality of death:

monthly digest of statistics. Hong Kong: The Govern- Ranking end-of-life care across the world. Singapore:

ment of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region. Lien Foundation.

Census and Statistics Department (2009). Thematic house- Giovanni, L.A. (2012). End-of-life care in the United States:

hold survey. Report No. 40. Hong Kong: The Govern- Current reality and future promise: A policy review.

ment of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region. Nursing Economics, 30, 127 –135.

Chan, C.L., Ho, A.H., Leung, P.P., et al. (2012). The bless- Ho, S.M.Y. & Shiu, W.C.T. (1995). Death anxiety and coping

ings and the curses of filial piety on dignity at the end mechanism of Chinese cancer patients. Omega, 31,

of life: Lived experience of Hong Kong Chinese adult 59–65.

children caregivers. Journal of Ethnic and Cultural Hsu, C.-Y., O’Connor, M., & Lee, S. (2009). Understanding

Diversity in Social Work, 21, 277– 296. of death and dying for people of Chinese origin. Death

Chan, C.W. & Chang, A.M. (2000). Experience of palliative Studies, 33, 153 –174.

home care according to caregivers’ and patients’ ages in Hui, E., Ma, H.M., Tang, W.H., et al. (2014). A new model

Hong Kong Chinese people. Oncology Nursing Forum, for end-of-life care in nursing homes. Journal of the

27, 1601– 1605. American Medical Directors Association, 15, 287– 289.

Chan, H.Y. & Pang, S.M. (2007). Quality-of-life concerns Lau, K.S., Tse, D.M., Tsan Chen, T.W., et al. (2010). Com-

and end-of-life care preferences of aged persons in paring noncancer and cancer deaths in Hong Kong: A

long-term care facilities. Journal of Clinical Nursing, retrospective review. Journal of Pain and Symptom

16, 2158– 2166. Management, 40, 704– 714.

Chan, W.C. (2011). Being aware of the prognosis: How does Lam, P.T., Ma, S.Y., Ng, H.Y., et al. (2011). Service outcomes

it relate to palliative care patients’ anxiety and commu- six years after implementing strategies in optimizing

nication difficulty with family members in the Hong bed utilization at a palliative care unit. Progress in Pal-

Kong Chinese context? Journal of Palliative Medicine, liative Care, 19, 109 –113.

14, 997 –1003. Lee, J., Cheng, J., Au, K.-M., et al. (2013). Improving the

Chan, W.C., Epstein, I., Reese, D., et al. (2009). Family quality of end-of-life care in long-term care institutions.

predictors of psychosocial outcomes among Hong Kong Journal of Palliative Medicine, 16, 1268– 1274.

Chinese cancer patients in palliative care: Living and Lo, R.S., Woo, J., Zhoc, K.C., et al. (2002). Quality of life

dying with the “support paradox.” Social Work in Health of palliative care patients in the last two weeks of

Care, 48, 519 –532. life. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 24,

Cheng, H.W.B., Chan, K.Y., Sham, M.K.M., et al. (2014a). 388 –397.

Symptom burden, depression, and suicidality in Chinese Lo, R.S., Kwan, B.H., Lau, K.P., et al. (2010). The needs,

elderly patients suffering from advanced cancer. Journal current knowledge, and attitudes of care staff toward

of Palliative Medicine, 17, 10. the implementation of palliative care in old age homes.

Cheng, H.W., Li, C.W., Chan, K.Y., et al. (2014b). Bringing The American Journal of Hospice & Palliative Care,

palliative care into geriatrics in a Chinese culture 27, 266 –271.

society: Results of a collaborative model between pallia- Lo, S.H., Chan, C.Y., Chan, C.H., et al. (2009). The imple-

tive medicine and geriatrics unit in Hong Kong. Journal mentation of an end-of-life integrated care pathway in

of the American Geriatrics Society, 62, 779– 781. a Chinese population. International Journal of Pallia-

Cheng, S.T., Lum, T., Lam, L.C., et al. (2013). Hong Kong: tive Nursing, 15, 384– 388.

Embracing a fast aging society with limited welfare. Loke, A.Y., Liu, C.F. & Szeto, Y. (2003). The difficulties

The Gerontologist, 53, 527 –533. faced by informal caregivers of patients with terminal

Chu, L. (2012). One step forward for advance directives in cancer in Hong Kong and the available social support.

Hong Kong. Hong Kong Medical Journal, 18, 176. Cancer Nursing, 26, 276– 283.

https://doi.org/10.1017/S1478951515000802 Published online by Cambridge University Press

1720 Wang & Chan

Luk, J.K.H., Liu, A., Beh, P. & Chan, F.H.W. (2011). End-of- elders with chronic. Hong Kong Medical Journal,

life care in Hong Kong. Asian Journal of Gerontology & 17(2), 105 –111.

Geriatrics, 6, 103 –106. Tong, K.-W. (2014). Good death through control over place of

Mak, Y.W., Chiang, V.C. & Chui, W.T. (2013). Experiences death? A snapshot in Hong Kong. In Community care in

and perceptions of nurses caring for dying patients Hong Kong: Current practices. Research studies and

and families in the acute medical admission setting. In- future directions. K.-W. Tong & K.N. Fong (eds.), pp.

ternational Journal of Palliative Nursing, 19, 423–431. 169– 208. Hong Kong: City University of Hong Kong

McIlfatrick, S.J. & Murphy, T. (2013). Palliative care Press.

research on the island of Ireland over the last decade: Tsang, M., Yeung, K., Wong, K., et al. (2013). Cross-section-

A systematic review and thematic analysis of peer- al survey on advance care planning acceptance and end-

reviewed publications. BMC Palliative Care, 12, 33. of-life care preferences among community-dwelling

Murray, S.A., Firth, A., Schneider, N., et al. (2015). Promot- elderly with complex medical problems and their carers.

ing palliative care in the community: Production of the BMJ Supportive & Palliative Care, 3, 258– 259.

primary palliative care toolkit by the European Associa- Tse, D.M., Chan, K.S., Lam, W.M., et al. (2007). The impact

tion of Palliative Care Taskforce in primary palliative of palliative care on cancer deaths in Hong Kong: A

care. Palliative Medicine, 29, 101 –111. retrospective study of 494 cancer deaths. Palliative Med-

National Council for Palliative Care (2013). National sur- icine, 21, 425 –433.

vey of patient activity data for specialist palliative care Williams, A.M., Crooks, V.A., Whitfield, K., et al. (2010).

services: MDS full report for the year 2011– 2012. Avail- Tracking the evolution of hospice palliative care in

able from http://www.endoflifecare-intelligence.org. Canada: A comparative case study analysis of seven

uk/resources/publications/patient_activity_data. provinces. BMC Health Services Research, 10, 147.

National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization (2013). Wong, F.K., Liu, C.F., Szeto, Y., et al. (2004). Health

NHPCO facts and figures: Hospice care in America. Avail- problems encountered by dying patients receiving

able from http://www.nhpco.org/sites/default/files/pub palliative home care until death. Cancer Nursing, 27,

lic/Statistics_Research/2013_Facts_Figures.pdf. 244– 251.

Hospital Authority of Hong Kong (2013). Hospital authority Wong, S., Lo, S., Chan, C., et al. (2012). Is it feasible to dis-

statistical report 2011–2012. Available from http://www. cuss an advance directive with a Chinese patient with

ha.org.hk/upload/publication_15/471.pdf. advanced malignancy? A prospective cohort study.

Sigurdardottir, K.R., Haugen, D.F., van der Rijt, C.C., et al. Hong Kong Medical Journal, 18(3), 178– 185.

(2010). Clinical priorities, barriers and solutions in Woo, J. & Chau, P.P. (2009). Aging in Hong Kong: The insti-

end-of-life cancer care research across Europe: Report tutional population. Journal of the American Medical

from a workshop. European Journal of Cancer, 46, Directors Association, 10, 478– 485.

1815– 1822. Woo, J., Cheng, J.O., Lee, J., et al. (2011a). Evaluation of

Silveira, M.J., Wiitala, W. & Piette, J. (2014). Advance di- a continuous quality improvement initiative for end-of-

rective completion by elderly Americans: A decade of life care for older noncancer patients. Journal of the

change. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 62, American Medical Directors Association, 12(2), 105–113.

706 –710. Woo, J., Lo, R., Cheng, J.O., et al. (2011b). Quality of end-of-

Siu, M.W., Cheung, T.Y., Chiu, M.M., et al. (2010). The pre- life care for non-cancer patients in a non-acute hospital.

paredness of Hong Kong medical students towards ad- Journal of Clinical Nursing, 20, 1834–1841.

vance directives and end-of-life issues. East Asian World Health Organization (WHO) (2002). Innovative

Archives of Psychiatry, 20(4), 155 –162. care for chronic conditions: Building blocks for action.

Siu, S.W., Liu, R.K., Cheung, K.W., et al. (2011). End-of-life Global report on noncommunicable diseases and mental

care for Chinese patients in an acute care ward setting: health. Geneva: WHO Press.

Experience in an oncology ward and report on a pilot Wu, A.M., Tang, C.S. & Kwok, T.C. (2002). Death anxiety

project on the use of an integrated care pathway. Pallia- among Chinese elderly people in Hong Kong. Journal

tive Medicine, 25, 664 –665. of Aging and Health, 14, 42–56.

Social Work Department (2013). Overview of residential Xu, Y. (2007). Death and dying in the Chinese Culture:

care services for elders. Available from http://www. Implications for health care practice. Home Health

swd.gov.hk/en/index/site_pubsvc/page_elderly/sub_ Care Management & Practice, 19, 412 –414.

residentia/id_overviewon/. Yan, S. & Cheng, K.F. (2006). Quality of life of patients with

Ting, F.H. & Mok, E. (2011). Advance directives and life- terminal cancer receiving palliative home care. Journal

sustaining treatment: Attitudes of Hong Kong Chinese of Palliative Care, 22, 261– 266.

https://doi.org/10.1017/S1478951515000802 Published online by Cambridge University Press

You might also like

- 1 s2.0 S1386505617300126 MainDocument14 pages1 s2.0 S1386505617300126 MainDyl DuckNo ratings yet

- Assessing Quality of Life in Older Adults: Psychometric Properties of The Opqol-Brief Questionnaire in A Nursing Home PopulationDocument14 pagesAssessing Quality of Life in Older Adults: Psychometric Properties of The Opqol-Brief Questionnaire in A Nursing Home PopulationRomy HidayatNo ratings yet

- BNur General - Paper 1 - Assignment - Qualitative Grounded Theory Rebuilding and Guiding A Care Community A Grounded Theory of End of LifeDocument10 pagesBNur General - Paper 1 - Assignment - Qualitative Grounded Theory Rebuilding and Guiding A Care Community A Grounded Theory of End of LifeywnngdchjbNo ratings yet

- An Integrated Review of Evidence-Based Healthcare Design For Healing Environments Focusing On Longterm Care FacilitiesDocument16 pagesAn Integrated Review of Evidence-Based Healthcare Design For Healing Environments Focusing On Longterm Care FacilitiesAmira EsamNo ratings yet

- JURNAL Indarwati 13Document10 pagesJURNAL Indarwati 13atika rahmawatiNo ratings yet

- Is Health Literacy of Family Carers Associated With Carer Burden, Quality of Life, and Time Spent On Informal Care For Older Persons Living With DementiaDocument16 pagesIs Health Literacy of Family Carers Associated With Carer Burden, Quality of Life, and Time Spent On Informal Care For Older Persons Living With DementiaCristina MPNo ratings yet

- Nurses' Knowledge About End-of-Life Care: Where Are We?Document6 pagesNurses' Knowledge About End-of-Life Care: Where Are We?Ritika AgarwalNo ratings yet

- Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment: British Journal of Hospital Medicine (London, England: 2005) August 2014Document5 pagesComprehensive Geriatric Assessment: British Journal of Hospital Medicine (London, England: 2005) August 2014FadhilannisaNo ratings yet

- Tan 2021Document19 pagesTan 2021Sara Juliana Rosero MedinaNo ratings yet

- Cejas Et Al. - Quality of Life-CI: Development of An Early Childhood Parent-Proxy & Adolescent VersionDocument28 pagesCejas Et Al. - Quality of Life-CI: Development of An Early Childhood Parent-Proxy & Adolescent VersionPablo VasquezNo ratings yet

- FMPCR Art 35839-10Document5 pagesFMPCR Art 35839-10Dave PchoNo ratings yet

- Incorporating Bioethics Education into School CurriculumsFrom EverandIncorporating Bioethics Education into School CurriculumsNo ratings yet

- Journal of Fluency Disorders: Alice K. Hart, Lauren J. Breen, Janet M. BeilbyDocument19 pagesJournal of Fluency Disorders: Alice K. Hart, Lauren J. Breen, Janet M. BeilbyasyaNo ratings yet

- Ifedayo Alatise Annotated Bibliography PPN201.Document8 pagesIfedayo Alatise Annotated Bibliography PPN201.diekola ridwanNo ratings yet

- Systemic Delivery Technologies in Anti-Aging Medicine: Methods and ApplicationsFrom EverandSystemic Delivery Technologies in Anti-Aging Medicine: Methods and ApplicationsNo ratings yet

- Poscia 2018Document12 pagesPoscia 2018Febria Rike ErlianaNo ratings yet

- Home-Based Care: A Need Assessment of People Living With HIV Infection in Bandung, IndonesiaDocument9 pagesHome-Based Care: A Need Assessment of People Living With HIV Infection in Bandung, IndonesiaLiza Marie Cayetano AdarneNo ratings yet

- Can I Play A Concept Analysis of Participation in Children With DisabilitiesDocument16 pagesCan I Play A Concept Analysis of Participation in Children With DisabilitiesjcpaterninaNo ratings yet

- Healthy Ageing Literature Review 2012Document9 pagesHealthy Ageing Literature Review 2012ygivrcxgf100% (1)

- Healthcare Service in Hong Kong and Its Challenges: China PerspectivesDocument9 pagesHealthcare Service in Hong Kong and Its Challenges: China PerspectivesGrace LNo ratings yet

- Covelli 2016Document9 pagesCovelli 2016Livea Sant'AnaNo ratings yet

- The Lancet Regional Health - Western Pacific: Research PaperDocument14 pagesThe Lancet Regional Health - Western Pacific: Research PaperwdcwweqwdsNo ratings yet

- Quality of Life in Persons With Intellectual Disabilities and Mental Health Problems: An Explorative StudyDocument9 pagesQuality of Life in Persons With Intellectual Disabilities and Mental Health Problems: An Explorative StudyRaquelMaiaNo ratings yet

- Fpubh 12 1329916Document9 pagesFpubh 12 1329916drabellollinasNo ratings yet

- European Journal of Internal MedicineDocument7 pagesEuropean Journal of Internal MedicineAlejandro CardonaNo ratings yet

- Burden of Caregiving For Strok PDFDocument10 pagesBurden of Caregiving For Strok PDFana irianiNo ratings yet

- 182 604 1 PBDocument10 pages182 604 1 PBAngel Nikiyuluw100% (1)

- Health Care Transition: Building a Program for Adolescents and Young Adults with Chronic Illness and DisabilityFrom EverandHealth Care Transition: Building a Program for Adolescents and Young Adults with Chronic Illness and DisabilityAlbert C. HergenroederNo ratings yet

- Lee2017 Factors Influencing Attitude ADDocument7 pagesLee2017 Factors Influencing Attitude ADdrabellollinasNo ratings yet

- Fpubh 11 1131031Document11 pagesFpubh 11 1131031Gaith FekiNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0167494323000985 MainDocument8 pages1 s2.0 S0167494323000985 Mainxia weitaoNo ratings yet

- Traduzir Politicas de Saude Cuidados PaliativosDocument17 pagesTraduzir Politicas de Saude Cuidados PaliativosJoana Brazão CachuloNo ratings yet

- Acceptance and Valued Living As Critical Appraisal and Coping Strengths For Caregivers Dealing With Terminal Illness and BereavementDocument10 pagesAcceptance and Valued Living As Critical Appraisal and Coping Strengths For Caregivers Dealing With Terminal Illness and BereavementPaula Catalina Mendoza PrietoNo ratings yet

- Kuru Et Al-2016-Journal of Clinical NursingDocument28 pagesKuru Et Al-2016-Journal of Clinical NursingFernandoCedroNo ratings yet

- Hommel 2015 PDFDocument7 pagesHommel 2015 PDFpaula cuervoNo ratings yet

- Quality of Life of The Elderly: A Comparison Between Community-Dwelling Elderly and in Social Welfare InstitutionsDocument5 pagesQuality of Life of The Elderly: A Comparison Between Community-Dwelling Elderly and in Social Welfare InstitutionsHesty PakidingNo ratings yet

- ¿Difieren Los Determinantes de La Calidad de Vida en Las Personas Mayores Que Viven en La Comunidad y en Residencias de Ancianos ORIGINALDocument12 pages¿Difieren Los Determinantes de La Calidad de Vida en Las Personas Mayores Que Viven en La Comunidad y en Residencias de Ancianos ORIGINALEvelia Ines Zaragoza CasanovaNo ratings yet

- Can I Play A Concept Analysis of Participation in Children With DisabilitiesDocument16 pagesCan I Play A Concept Analysis of Participation in Children With DisabilitiesEmi MedinaNo ratings yet

- TaiwanDocument11 pagesTaiwanbin linNo ratings yet

- The Chinese Version of The World Health Organization Quality of Life Instrument-Older Adults Module (WHOQOL-OLD) : Psychometric EvaluationDocument8 pagesThe Chinese Version of The World Health Organization Quality of Life Instrument-Older Adults Module (WHOQOL-OLD) : Psychometric EvaluationSyed ShahNo ratings yet

- The Effects of A Virtual Reality Rehabilitation Task On Elderly Subjects - An Experimental Study Using Multimodal DataDocument9 pagesThe Effects of A Virtual Reality Rehabilitation Task On Elderly Subjects - An Experimental Study Using Multimodal DataAgus SGNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Tugas InggrisDocument8 pagesJurnal Tugas InggrisTriska YuanaNo ratings yet

- Nurses ' Practice Environment and Their Job Satisfaction: A Study On Nurses Caring For Older Adults in ShanghaiDocument13 pagesNurses ' Practice Environment and Their Job Satisfaction: A Study On Nurses Caring For Older Adults in ShanghaiAzzalfaAftaniNo ratings yet

- Applied Nursing Research: A B A ADocument5 pagesApplied Nursing Research: A B A AHüseyin GürerNo ratings yet

- Living with Dementia: Neuroethical Issues and International PerspectivesFrom EverandLiving with Dementia: Neuroethical Issues and International PerspectivesVeljko DubljevićNo ratings yet

- The Cult and Science of Public Health: A Sociological InvestigationFrom EverandThe Cult and Science of Public Health: A Sociological InvestigationNo ratings yet

- Finding the Path in Alzheimer’s Disease: Early Diagnosis to Ongoing Collaborative CareFrom EverandFinding the Path in Alzheimer’s Disease: Early Diagnosis to Ongoing Collaborative CareNo ratings yet

- Trends and Hotspots of Family Nursing Research Based On Web of Science: A Bibliometric AnalysisDocument10 pagesTrends and Hotspots of Family Nursing Research Based On Web of Science: A Bibliometric AnalysisVia Eliadora TogatoropNo ratings yet

- Evidence On The Contribution of CommunityDocument20 pagesEvidence On The Contribution of CommunityGintarė AmalevičiūtėNo ratings yet

- Psychosocial Well-Being After Kidney Transplantation: A Matched-Pair Case-Control StudyDocument8 pagesPsychosocial Well-Being After Kidney Transplantation: A Matched-Pair Case-Control StudychoyNo ratings yet

- Chapters 1 To 2. Incomplete. Please Double CheckDocument19 pagesChapters 1 To 2. Incomplete. Please Double CheckajdgafjsdgaNo ratings yet

- Active Ageing An Empirical Approach To The WHO ModDocument11 pagesActive Ageing An Empirical Approach To The WHO ModJust a GirlNo ratings yet

- Research Article5Document8 pagesResearch Article5Marinel MirasNo ratings yet

- Titulo 3Document11 pagesTitulo 3StéphanieLyanieNo ratings yet

- Quality of Life in Glaucoma: A Review of The LiteratureDocument23 pagesQuality of Life in Glaucoma: A Review of The LiteratureMakhda Nurfatmala LNo ratings yet

- Examination of Telemental Health Practices in Caregivers of Children and Adolescents With Mental Illnesses A Systematic ReviewDocument14 pagesExamination of Telemental Health Practices in Caregivers of Children and Adolescents With Mental Illnesses A Systematic ReviewMushlih RidhoNo ratings yet

- The Effectiveness of A Group Based Otago Exercise Program On Phy - 2023 - Geriat PDFDocument14 pagesThe Effectiveness of A Group Based Otago Exercise Program On Phy - 2023 - Geriat PDFJefrioSuyantoNo ratings yet

- Palliative Nursing Care As Applied To Geriatric An PDFDocument6 pagesPalliative Nursing Care As Applied To Geriatric An PDFVILLEJO JHOVIALENNo ratings yet

- Journal of Clinical Nursing - 2023 - Lafiatoglou - Older Adults Lived Experiences of Physical Rehabilitation For AcquiredDocument16 pagesJournal of Clinical Nursing - 2023 - Lafiatoglou - Older Adults Lived Experiences of Physical Rehabilitation For AcquiredIoanna ZygouriNo ratings yet

- Effects of Facilitated Family Case Conferencing For Advanced Dementia - A Cluster Randomised Clinical Trial.Document16 pagesEffects of Facilitated Family Case Conferencing For Advanced Dementia - A Cluster Randomised Clinical Trial.charmyshkuNo ratings yet

- EAPC White Paper On Outcome MeasurementDocument17 pagesEAPC White Paper On Outcome MeasurementcharmyshkuNo ratings yet

- Using Palliative Leaders in Facilities To Transform Care For People With Alzheimer's Disease (UPLIFT-AD) - Protocol of A Palliative Care Clinical Trial in Nursing HomesDocument10 pagesUsing Palliative Leaders in Facilities To Transform Care For People With Alzheimer's Disease (UPLIFT-AD) - Protocol of A Palliative Care Clinical Trial in Nursing HomescharmyshkuNo ratings yet

- Kaasalainen 2020 Current Issues With Implementing A Palliative Approach in Long Term Care Where Do We Go From HereDocument3 pagesKaasalainen 2020 Current Issues With Implementing A Palliative Approach in Long Term Care Where Do We Go From HerecharmyshkuNo ratings yet

- Effectiveness and Cost-Effectiveness of Home Palliative Care Services For Adults With Advanced Illness and Their CaregiversDocument232 pagesEffectiveness and Cost-Effectiveness of Home Palliative Care Services For Adults With Advanced Illness and Their CaregiverscharmyshkuNo ratings yet

- Effects of A Transitional Palliative Care Model On Patients With End-Stage Heart Failure - A Randomised Controlled TrialDocument9 pagesEffects of A Transitional Palliative Care Model On Patients With End-Stage Heart Failure - A Randomised Controlled TrialcharmyshkuNo ratings yet

- JHKGS9612 P 009Document5 pagesJHKGS9612 P 009charmyshkuNo ratings yet

- SERIOUS ILLNESS COMMUNICATION PROJECT - ProtocolDocument142 pagesSERIOUS ILLNESS COMMUNICATION PROJECT - ProtocolcharmyshkuNo ratings yet

- The Impact of Need-Based Care On Formal Caregivers' Wellbeing in Nursing Homes - A Cluster Randomized Controlled TrialDocument10 pagesThe Impact of Need-Based Care On Formal Caregivers' Wellbeing in Nursing Homes - A Cluster Randomized Controlled TrialcharmyshkuNo ratings yet

- An Electronic Adherence Measurement Intervention To Reduce Clinical Inertia in The Treatment of Uncontrolled Hypertension - The MATCH Cluster Randomized Clinical TrialDocument7 pagesAn Electronic Adherence Measurement Intervention To Reduce Clinical Inertia in The Treatment of Uncontrolled Hypertension - The MATCH Cluster Randomized Clinical TrialcharmyshkuNo ratings yet

- The Effects of Advance Care Planning Intervention On Nursing Home Residents - A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomised Controlled TrialsDocument10 pagesThe Effects of Advance Care Planning Intervention On Nursing Home Residents - A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomised Controlled TrialscharmyshkuNo ratings yet

- Criteria For Selecting Implementation Science Theories and Frameworks: Results From An International SurveyDocument9 pagesCriteria For Selecting Implementation Science Theories and Frameworks: Results From An International SurveyAngellaNo ratings yet

- The RESOLVE PCOM Implementation StrategyDocument9 pagesThe RESOLVE PCOM Implementation StrategycharmyshkuNo ratings yet

- Adherence To Key Recommendations For Design and Analysis of Stepped-Wedge Cluster Randomized Trials - A Review of Trials Published 2016-2022Document12 pagesAdherence To Key Recommendations For Design and Analysis of Stepped-Wedge Cluster Randomized Trials - A Review of Trials Published 2016-2022charmyshkuNo ratings yet

- BMJ g1687 FullDocument12 pagesBMJ g1687 FullJaumeNo ratings yet

- Impact of Nursing Home Palliative Care Teams On End-of-Life Outcomes - A Randomized Controlled TrialDocument8 pagesImpact of Nursing Home Palliative Care Teams On End-of-Life Outcomes - A Randomized Controlled TrialcharmyshkuNo ratings yet

- 2020, JCO - disseminationandImplementationofPalliative CareinOncologyDocument8 pages2020, JCO - disseminationandImplementationofPalliative CareinOncologycharmyshkuNo ratings yet

- 17538068.2022 - 複製Document13 pages17538068.2022 - 複製cindy8127No ratings yet

- (2023) JAMDATiming of Goals of Care Discussions in Nursing Homes - A Systematic ReviewDocument11 pages(2023) JAMDATiming of Goals of Care Discussions in Nursing Homes - A Systematic ReviewcharmyshkuNo ratings yet

- Improved Quality of Death and Dying in Care Homes - A Palliative Care Stepped Wedge Randomized Control Trial in AustraliaDocument8 pagesImproved Quality of Death and Dying in Care Homes - A Palliative Care Stepped Wedge Randomized Control Trial in AustraliacharmyshkuNo ratings yet

- 2020, JCO - disseminationandImplementationofPalliative CareinOncologyDocument8 pages2020, JCO - disseminationandImplementationofPalliative CareinOncologycharmyshkuNo ratings yet

- Improved Quality of Death and Dying in Care Homes - A Palliative Care Stepped Wedge Randomized Control Trial in Australia (Protocal)Document34 pagesImproved Quality of Death and Dying in Care Homes - A Palliative Care Stepped Wedge Randomized Control Trial in Australia (Protocal)charmyshkuNo ratings yet

- 2004 - GREENHALGH - Diffusion of Innovations in Service Organizations Systematic Review andDocument49 pages2004 - GREENHALGH - Diffusion of Innovations in Service Organizations Systematic Review andcharmyshkuNo ratings yet

- Ingredients For Change: Revisiting A Conceptual Framework: ViewpointDocument7 pagesIngredients For Change: Revisiting A Conceptual Framework: Viewpointujangketul62No ratings yet

- s12904 021 00847 7Document9 pagess12904 021 00847 7charmyshkuNo ratings yet

- Stepped Wedged Cluster Randomised TrialDocument7 pagesStepped Wedged Cluster Randomised Trialshariff gutierrezNo ratings yet

- Stepped Wedged Cluster Randomised TrialDocument7 pagesStepped Wedged Cluster Randomised Trialshariff gutierrezNo ratings yet

- Laboratory Manual For Microbiology Fundamentals A Clinical Approach 4Th Edition Susan Finazzo Full ChapterDocument51 pagesLaboratory Manual For Microbiology Fundamentals A Clinical Approach 4Th Edition Susan Finazzo Full Chapterlinda.ferguson121100% (7)

- ISO 27001 MindmapsDocument6 pagesISO 27001 MindmapsYagnesh VyasNo ratings yet

- Alabama Religious Exemption AdvisoryDocument1 pageAlabama Religious Exemption AdvisoryABC 33/40No ratings yet

- Problems Associated With The Use of Compaction Grout For SinkholeDocument4 pagesProblems Associated With The Use of Compaction Grout For SinkholeVetriselvan ArumugamNo ratings yet

- List of Grocery Importers in Austria Europe PDF FreeDocument11 pagesList of Grocery Importers in Austria Europe PDF FreeEmpy SumardiNo ratings yet

- Grade 12 - Biology Resource BookDocument245 pagesGrade 12 - Biology Resource BookMali100% (6)

- MSC Nursing Approved Thesis Topics 2009-12Document32 pagesMSC Nursing Approved Thesis Topics 2009-12Anonymous 4L20Vx60% (5)

- Digital Portable 4.0/8.0 KW Dragon LW System Digital Portable 4.0/8.0 KW Dragon LW SystemDocument8 pagesDigital Portable 4.0/8.0 KW Dragon LW System Digital Portable 4.0/8.0 KW Dragon LW Systemteacher_17No ratings yet

- Food Safety and Standards Act, 2006Document23 pagesFood Safety and Standards Act, 2006Deepam TandonNo ratings yet

- SECTION 03310-1 Portland Cement Rev 1Document10 pagesSECTION 03310-1 Portland Cement Rev 1Abdalrahman AntariNo ratings yet

- Substation Basic PDFDocument6 pagesSubstation Basic PDFSaraswatapalitNo ratings yet

- Problems SetDocument10 pagesProblems SetSajith KurianNo ratings yet

- Narayani and Soham Remedies by Jaco Malan Descriptions & RatesDocument40 pagesNarayani and Soham Remedies by Jaco Malan Descriptions & RatesAlex VimanNo ratings yet

- CHEM 333: Lab Experiment 5: Introduction To Chromatography : Thin Layer and High Performance Liquid ChromatographyDocument5 pagesCHEM 333: Lab Experiment 5: Introduction To Chromatography : Thin Layer and High Performance Liquid ChromatographymanurihimalshaNo ratings yet

- BSNL KERALA Executives and Non Executives Health Insurance Policy 2021-22Document3 pagesBSNL KERALA Executives and Non Executives Health Insurance Policy 2021-22Vikramjeet MannNo ratings yet

- Oil Palm Fractions Derivatives Web PDFDocument6 pagesOil Palm Fractions Derivatives Web PDFIan RidzuanNo ratings yet

- Professional DevelopmentDocument1 pageProfessional Developmentapi-488745276No ratings yet

- Buoyancy Calculation Report For 10INCH PipelineDocument7 pagesBuoyancy Calculation Report For 10INCH PipelineEmmanuel LawrenceNo ratings yet

- Distance Learning in Clinical MedicalDocument7 pagesDistance Learning in Clinical MedicalGeraldine Junchaya CastillaNo ratings yet

- Invoice, packing list mẫuDocument2 pagesInvoice, packing list mẫuPHI BUI MINHNo ratings yet

- Tutorial SessionDocument5 pagesTutorial SessionKhánh LinhNo ratings yet

- 1978 - Behavior Analysis and Behavior Modification - Mallot, Tillema & Glenn PDFDocument499 pages1978 - Behavior Analysis and Behavior Modification - Mallot, Tillema & Glenn PDFKrusovice15No ratings yet

- Banana Disease 2 PDFDocument4 pagesBanana Disease 2 PDFAlimohammad YavariNo ratings yet

- FilterFlow Cartridge Installation GuideDocument8 pagesFilterFlow Cartridge Installation GuideSilver FoxNo ratings yet

- Anesthesiology GuideDocument4 pagesAnesthesiology GuideGeorge Wang100% (1)

- Structure of AtomDocument90 pagesStructure of Atomnazaatul aaklimaNo ratings yet

- 2019 PSRANM Conference Program FinalDocument24 pages2019 PSRANM Conference Program FinalKimmie JordanNo ratings yet

- Homework #3Document2 pagesHomework #3RobbieNo ratings yet

- First Communion: You Are The VoiceDocument10 pagesFirst Communion: You Are The VoiceErnesto Albeus Villarete Jr.No ratings yet

- EpidemiologyDocument26 pagesEpidemiologymohildasadiaNo ratings yet