Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Chapter 7. Asset Market. Overheads. F2016

Chapter 7. Asset Market. Overheads. F2016

Uploaded by

sutoraifuviiOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Chapter 7. Asset Market. Overheads. F2016

Chapter 7. Asset Market. Overheads. F2016

Uploaded by

sutoraifuviiCopyright:

Available Formats

Chapter 7: The Asset Market, Money and Prices: Abel, Bernanke, Croushore, Kneebone

Economics 303: OVERHEADS: D. McClintock

Chapter 7

The Asset Market, Money and Prices

Table of Contents

7.1 What is Money?

- Early Money

- Functions of Money

- Measuring Money: The Monetary Aggregates

7.2 Portfolio Allocation and the Demand for Assets

- Expected Return, Risk and Liquidity

- Time to Maturity

- Types of Assets and Their Characteristics

- Asset Demand

7.3 The Demand for Money

- The Price Level

- Real Income

- Interest Rates

- The Money Demand Function

- Other Factors Affecting Money Demand

- Elasticities of Money Demand

- Velocity and the Quantity Theory of Money

7.4 Asset Market Equilibrium

- Asset Market Equilibrium

7.5 Money Growth and Inflation

- Inflation Equation

- The Expected Inflation Rate and The Nominal Interest Rate

Intellectual property of Douglas McClintock and authors cited above Page 1

Chapter 7: The Asset Market, Money and Prices: Abel, Bernanke, Croushore, Kneebone

Economics 303: OVERHEADS: D. McClintock

7.1 What is Money?

In economics, the meaning of money is different from its everyday meaning.

People often say money when they mean income or wealth. Some people may say,

he makes a lot of money or, she has a lot of money.

In this context, they actually mean income in the first example and wealth in the

second.

In economics, money refers specifically to assets that are widely used and

accepted as payment.

Historically, the forms of money have ranged from beads to shells to gold

and silver and in some cases, cigarettes. Goods that are used as money but

have another purpose (such as cigarettes, beaver pelts, gold and silver) is

known as commodity money.

Money is the most universal and most efficient system of trust ever devised.

(see the book Sapiens by Yuval Harari, page 180)

First Money

According to many scholars, it is widely agreed that barley was first commodity to

be used as money. It is known as Sumerian Barley money, which was used about

3000 - 3500 BC in Sumer, which is now part of Turkey.

(It is interesting to note that the Sumerians are credited with the first written word

and the invention of the wheel.)

Barley money was simply barley, where fixed amount of barley grains were used

for the purchase of goods and services. The most common measurement was the

sila (approx. 0.82 of a litre) and even wages were set in silas.

Problem: Inconvenient. Mold, mice and making large purchases would be difficult.

Intellectual property of Douglas McClintock and authors cited above Page 2

Chapter 7: The Asset Market, Money and Prices: Abel, Bernanke, Croushore, Kneebone

Economics 303: OVERHEADS: D. McClintock

Early Non-intrinsic money – shekels and coins

The real gain in monetary history took place when people gained trust in

money that lacked inherent value, (i.e. eat it ,drink it or wear it) but was

easier to store and transport. That was the silver shekel.

The silver shekel appeared in Mesopotamia around 2500 to 3000

BC.

The silver shekel was not a coin but rather 8.33 grams of silver.

This was much easier than handling barley and shekels were used

for thousands of years.

Intellectual property of Douglas McClintock and authors cited above Page 3

Chapter 7: The Asset Market, Money and Prices: Abel, Bernanke, Croushore, Kneebone

Economics 303: OVERHEADS: D. McClintock

Coins

Sumerians (the first known culture to use coins as money – were also credited with

the invention of the wheel and the first written word. (for accounting purposes)

Lydian coins

Lydian Lion and an ancient Lydian coin

The Lydian Lion head can be viewed in the British Museum in London, England

Intellectual property of Douglas McClintock and authors cited above Page 4

Chapter 7: The Asset Market, Money and Prices: Abel, Bernanke, Croushore, Kneebone

Economics 303: OVERHEADS: D. McClintock

Island of Yap (Stone Money)

Source: Google, Island of Yap Stone Money. August 2016.

Intellectual property of Douglas McClintock and authors cited above Page 5

Chapter 7: The Asset Market, Money and Prices: Abel, Bernanke, Croushore, Kneebone

Economics 303: OVERHEADS: D. McClintock

FUNCTIONS OF MONEY

Money has three useful functions in an economy

1. Medium of Exchange

The medium of exchange means that money is used for making transactions.

In an economy with no money, trading takes the form of barter, which is the direct

exchange of certain goods for other goods.

Barter is Inefficient – an example

Suppose I want to take my girlfriend out for a very romantic meal. I would first

have to find a restauranteur who is willing to trade a meal for an economics lecture

– which might not be easy to do.

Money makes searching for the perfect trading partner unnecessary. With an

economy that uses money, I do not have to find a restaurant owner who is hungry

for knowledge.

Instead, I can give a lecture to young, very smart students and then use that money

to buy a meal. Money is therefore used as a medium of exchange as the

restauranteur will accept money for the meal. You can see that people can trade

with much less time and effort.

It also allows people to specialize.

Intellectual property of Douglas McClintock and authors cited above Page 6

Chapter 7: The Asset Market, Money and Prices: Abel, Bernanke, Croushore, Kneebone

Economics 303: OVERHEADS: D. McClintock

The number of relative prices (or exchange rates)

# of possible exchanges = N (N-1)/2 where N = # number of goods to be traded.

2. Unit of Account

As a unit of account, money is the basic unit for measuring economic value.

In Canada, virtually all prices, wages, asset values and debts are expressed in

dollars.

In the UK, these prices are expressed in terms of sterling pounds and in Australia,

Australian dollars as an example.

A currency that is used as a unit of account also applies that there is no loss of

value if smaller denominations are used.

3. Store of Value

As an asset, money is a way of holding wealth. If a local currency did not have a

store of value than citizens would start to use a different currency and the local

currency would cease to exist. (or used very infrequently)

Many assets have a store of value but money is the most liquid.

Liquidity means the ease or speed in which an asset can be converted as a medium

of exchange. Although bonds, term deposits, cars and houses also have a store of

value, it is difficult (and some can be expensive) to convert these assets as a

medium of exchange. As a result, money is the most liquid.

Intellectual property of Douglas McClintock and authors cited above Page 7

Chapter 7: The Asset Market, Money and Prices: Abel, Bernanke, Croushore, Kneebone

Economics 303: OVERHEADS: D. McClintock

MEASURING MONEY: THE MONETARY AGGREGATES

M1+ (Money Aggregate)

M1+ is the narrowest definition of the money supply.

M1+ is made up of currency in circulation (currency not held my banks) and

chequable deposits in personal and non-personal (businesses and corporations)

deposits. These include deposits at Credit Unions, Mortgage and Trust Companies,

Caisse Populaires and the large chartered banks.

M1+ is perhaps the closest counterpart to the theoretical definition of money

because all its components are actively used and widely accepted for making

payments.

Table 7.1

The Canadian Monetary Aggregates (November 2013)

M1+ $644.7 billion

Currency $64.7 billion

Chequable deposits $582.0 billion

M2 $1,232.0 billion

M1+ $644.7 billion

Personal savings deposits 548.5 billion

M3 $1,747.6 billion

M2 $1,232.0 billion

Non-personal term deposits $274.8 billion

Foreign currency deposits of residents $251.0 billion

Intellectual property of Douglas McClintock and authors cited above Page 8

Chapter 7: The Asset Market, Money and Prices: Abel, Bernanke, Croushore, Kneebone

Economics 303: OVERHEADS: D. McClintock

M2 is a more broadly defined measure of the money supply.

M2 includes M1 but also includes personal and non –personal non-chequable

deposits. These are savings accounts for firms and individuals. As cheques cannot

be written on these deposits, they are less convenient as a medium of exchange so

they are a little less “money like”. (Able, Bernanke et. Al)

M3 includes non-personal term deposits by firms. Term deposits pay a higher rate

of interest and there is usually a high penalty if the money is withdrawn before the

maturity date. Once again, money held as M3 is less convenient to use as a

medium of exchange than either M1+ or M2 making M3 a more broadly defined

definition of the money supply.

Intellectual property of Douglas McClintock and authors cited above Page 9

Chapter 7: The Asset Market, Money and Prices: Abel, Bernanke, Croushore, Kneebone

Economics 303: OVERHEADS: D. McClintock

The Money Supply

The money supply is the amount of money available in an economy. In modern

economies, the money supply is partially determined by the central bank – The

Bank of Canada in Canada.

The Bank of Canada can increase or decrease the money supply in two important

ways.1) through open market operations and 2) lending to financial institutions

from its Standing Liquidity Facility.

OMO

Open market operations is when the B of C buys and sells securities with the

Primary Dealers, who are financial institutions that are allowed to buy and

sell with the B of C at the weekly bond auction.

These financial institutions have large portfolios of securities that come from

their own portfolio and bonds from the public.

The B of C also uses open market operations to keep the key overnight

lending rate within the a 50 basis point range that is established by the Bank

of Canada.

This overnight lending rate is the short term overnight rate (or band) that

financial institutions can lend or borrow from each other.

The Standing Liquidity Facility

The Standing Liquidity Facility was established after the near collapse of the

world financial system in 2008 and it provides short term financing for

financial institutions.

If these financial institutions find themselves short of cash reserves, they can

borrow from Standing Liquidity Facility for a period of 6 months and extend

these loans if deemed necessary. (usually for another 6 months)

Intellectual property of Douglas McClintock and authors cited above Page 10

Chapter 7: The Asset Market, Money and Prices: Abel, Bernanke, Croushore, Kneebone

Economics 303: OVERHEADS: D. McClintock

Bank of Canada’s Updated Definition of the Money Aggregates – 2016

Macroeconomics 203

Money Supply Diagram

Money Supply

(dollars x 1,000,000)

Narrow Definition of the Money Supply

$1,213,538

Non-chequing

accounts

( savings

accounts)

excluding fixed

term deposits

held at

Chartered banks,

TML,

CU

Caisse

Populaires

$824,228

Currency outside

banks

+

chequing accounts TML = Trust, Mortgage and

held at Loan Companies

Chartered banks, CU = Credit Unions

Trust and Mortgage CP = Caisse Populaires

Loan Companies,

Credit Unions and M1+

Caisse Populaires

Diagrams not to scale

M1+ M1++

Note: Dollar amounts obtained from Stats Canada, Table 176-0020. These amounts are for January

2016.

Intellectual property of Douglas McClintock and authors cited above Page 11

Chapter 7: The Asset Market, Money and Prices: Abel, Bernanke, Croushore, Kneebone

Economics 303: OVERHEADS: D. McClintock

Macroeconomics 203

Money Supply Diagram

Money Supply

(dollars x 1,000,000)

$2,745,019*

Broad Definition of the Money Supply

Canada Savings

Bonds, non-money

mutual funds

$1,772751*

personal deposits

(including term

deposits)

+

Bank non-personal

demand

and

notice

Deposits

At

TML

CU

CP

Life Insurance

Annuities

+

Money Market

Mutual Funds

$1,391,083

Currency outside

banks

+

Chartered Bank M2

personal deposits

(including term

deposits)

+

Bank non-personal

demand

and

notice

deposits

M2 M2+ M2++

Note: Dollar amounts obtained from Stats Canada, Table 176-0020. (January 2016)

* December 2015.

Diagrams not to scale

Intellectual property of Douglas McClintock and authors cited above Page 12

Chapter 7: The Asset Market, Money and Prices: Abel, Bernanke, Croushore, Kneebone

Economics 303: OVERHEADS: D. McClintock

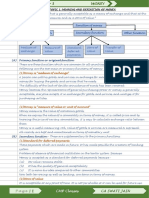

Portfolio Allocation and the Demand for Assets

Our next goal is to understand how people determine the amount of money they

choose to hold. There are many different asset classes and money is just one of

them.

The decision about which assets and how much of each asset to hold is called the

portfolio allocation decision.

The portfolio allocation decision can be quite complex but it determines the mix of

assets one should hold to maximize their returns (and minimize risk) over a given

period. The study of portfolio allocation is called financial economics.

Expected Return

Although future returns are not known with certainty, the holders of wealth must

base their portfolio allocations based on expected returns. With everything else

being equal, the higher an asset’s expected return, the more desirable the asset is

and the more of its holders of wealth will want to own it.

Risk

The uncertainty about the return of an asset is the second important characteristic

of an asset. An asset or a portfolio of assets has a high risk if there is a significant

chance that the actual return of the asset will be significantly different from the

expected return.

Investing in a new start-up company has a significantly higher risk that a blue chip

company that has been around for a long time. (E.g. Microsoft, Bell Canada, TD

Bank, Proctor Gamble etc.)

The risk of an asset is often determined by the price movement of the asset around

the price movement of the market. If the stock price fluctuates widely relative to

the market, it has a high beta and the stock is riskier than the stock market. If stock

has a beta of 1.2, it is 20% riskier than the market. If the beta of the stock is 0.8, it

is approx. 80% less risky than the market. A stock with a high beta has much more

price volatility relative to the market than a stock with a low Beta.

Intellectual property of Douglas McClintock and authors cited above Page 13

Chapter 7: The Asset Market, Money and Prices: Abel, Bernanke, Croushore, Kneebone

Economics 303: OVERHEADS: D. McClintock

Liquidity

As mentioned earlier, liquidity is the ease or speed in which an asset can be

converted to a medium of exchange. Money is the most liquid since it can be used

immediately to make purchases of goods and services.

Time to Maturity

Time to maturity is an important characteristic in determining the risk/reward

trade-off. Generally speaking, the longer the maturity date of the asset (such as a

bond) the higher the return on the asset. The investor will want to be compensated

with a higher interest rate if he/she has to hold on to the asset longer than say, a

shorter term bond.

The longer term bond is more risky because the company may go bankrupt, or

have financial difficulties in making these future payments. In addition, people

generally want consumption to occur earlier than later so they have to be

compensated for future consumption.

Intellectual property of Douglas McClintock and authors cited above Page 14

Chapter 7: The Asset Market, Money and Prices: Abel, Bernanke, Croushore, Kneebone

Economics 303: OVERHEADS: D. McClintock

THE DEMAND FOR MONEY

The demand for money is the amount of cash or chequing accounts that people

choose to hold in their portfolios. Choosing how much money to hold is therefore

part of a broader portfolio allocation decision.

In general, the demand for money (like other assets) depends on the expected

return, risk, liquidity. In practice, two features of money are important:

1) Money is the most liquid of all assets

2) Money give a very low (or zero) rate of return.

Since money has a very low rate of return, the low rate of return relative to other

assets is the major cost of holding money.

The macroeconomic variables that have the greatest effects on money demand are

the price level, real income and interest rates. Higher prices or incomes increase

people’s need for liquidity and thus, raise money demand. Interest rates affect

money demand through the expected return channel.

The higher the interest rate paid on alternative investments (say government bonds)

the more people will want to switch from money to those alternative assets such as

bonds.

THE MONEY DEMAND FUNCTION

The money demand function can be expressed as:

Md = P x L(Y, i)

Where Md = the aggregate demand for money, in nominal terms

P = the general price level (say CPI)

L= function relating money demand to real income and the nominal interest rate.

Y = real income or output

i = the nominal interest rate earned by alternative nonmonetary assets. (Govt

bonds)

Intellectual property of Douglas McClintock and authors cited above Page 15

Chapter 7: The Asset Market, Money and Prices: Abel, Bernanke, Croushore, Kneebone

Economics 303: OVERHEADS: D. McClintock

Recall

Md = P x L(Y, i)

Therefore,

Md = PL(Y, i) (equation 7.1 in text)

The equation above indicates that for any price level P, money demand depends

(through the function L) on the level, real income Y (or output) and the nominal

interest rate on non-monetary assets. (Such as bonds, term deposits, other assets

etc.)

The equation states that there is a proportional relationship between the demand for

money and the price level. Hence, if the price level doubles (and real output and

the interest rate remained unchanged) the nominal demand for money will double.

In the equation above “i” is the nominal interest rate. Because the nominal interest

rate has two components, the real interest rate plus the expected rate of inflation,

i = r + πe.

It is assumed that the interest on money (money assets) is zero since the interest

rate on holding cash in your pocket is zero but also, the interest rate on money in

chequing accounts would be very small. Thus this assumption is reasonable.

The equation above says that any price level P, Md is positively related to real

output (as economic activity increases, people want to hold more money for

payments and transactions) and negatively related to the nominal interest rate on

non-monetary assets.

If the interest rate, say on bonds or other assets increase, the opportunity cost of

holding money increases so the demand for money falls.

Intellectual property of Douglas McClintock and authors cited above Page 16

Chapter 7: The Asset Market, Money and Prices: Abel, Bernanke, Croushore, Kneebone

Economics 303: OVERHEADS: D. McClintock

Real Money Demand

Sometimes it is more convenient to express the nominal demand for money in

terms of the real demand for money.

The nominal demand for money is the amount of dollars that people wish to hold

as money where the real demand for money represents the amount of money

demanded in terms of the goods and services it will buy.

This is why the real demand for money is sometimes called the demand for real

balances.

Recall:

Md = PL(Y, i) or

Md = PL(Y, r + πe) (equation 7.2)

By rearranging

Md/P = L(Y, r + πe) (equation 7.3) (Money Demand Function)

The equation states that real money demand if related to real output and the

nominal interest rate.

This equation states that if real income increases (and the price level and nominal

interest rates do not change) then real money demand will increase.

Or

If the price level doubles, (and nominal money demand and interest rates does not

change) then real output Y will fall.

Intellectual property of Douglas McClintock and authors cited above Page 17

Chapter 7: The Asset Market, Money and Prices: Abel, Bernanke, Croushore, Kneebone

Economics 303: OVERHEADS: D. McClintock

Other Factors Affecting Money Demand

The money demand function in the previous pages captures the main

macroeconomic determinants. However there are other determinants that also

affect money demand.

Wealth: When wealth increases, this will also increase money demand. Wealth can

increase if their balance sheet increases, say through an increase in real estate

holdings, their stock market portfolio, bond holdings or a combination of these

assets.

However, economists feel that the wealth effect on money demand will be small.

Holding income and the level of transactions constant, a holder of wealth will have

little incentive to hold more money. However, the level of transactions will

obviously increase so in this respect, money demand will increase.

Risk: Money itself usually pays a fixed rate of interest (cash pays a zero interest

rate) so holding money itself isn’t risky.

Yet, in periods of rapid inflation the holding of money can be very risky. In this

case, people will want to switch their holdings into more inflation-proof assets

such as real estate, consumer goods and gold. Money demand in this case would

fall.

On the other hand, if people feel there is a bubble (in the stock market or in real

estate – so there is more risk in these markets) people may want to hold more cash)

Liquidity of Alternative Assets: The quickly and easily alternative assets can be

converted into cash, the less need there is to hold money. Today, we have

electronic trading accounts where a person can sell financial assets very quickly to

access cash. Furthermore, the introduction of financial lines of credit and

innovative life insurance policies, people have access to cash very quickly. These

are other reasons why the demand for money is less.

Intellectual property of Douglas McClintock and authors cited above Page 18

Chapter 7: The Asset Market, Money and Prices: Abel, Bernanke, Croushore, Kneebone

Economics 303: OVERHEADS: D. McClintock

Payment Technologies

The way we do banking and make payments has changed dramatically in the last

10 years. When I was working up north in the late 1970’ and early 1980’s, we had

to physically go to the bank to get cash or we went without.

Nowadays, we can use credit cards, ATM’s or web-banking to make payments.

Because we can access this new technology so easily, we don’t have to have as

much money in our chequing accounts or on our persons to make payments and

transactions. For this reason, the demand for money is less. As technology and

innovation becomes more sophisticated, it is possible that the demand for

traditional forms of money will be close to zero.

Intellectual property of Douglas McClintock and authors cited above Page 19

Chapter 7: The Asset Market, Money and Prices: Abel, Bernanke, Croushore, Kneebone

Economics 303: OVERHEADS: D. McClintock

MACROECONOMIC DETERMINANTS OF THE DEMAND FOR MONEY

All else equal Causes Money Demand Reason

An increase in to

Price level P Rise Proportionally The double of prices doubles

the number of dollars needed

for (same) transactions

Real Income Y Rise less than proportionally Higher real income implies

more transactions and thus

greater demand for liquidity.

As real income increases, not

all this money would be used

for transactions so money

demand rises less than

proportionally.

Nominal interest rate (i) and Fall Higher interest rates means

real interest rate higher returns on alternative

i = r + πe investments so people switch

away from money

Nominal interest rate on Rise A higher return on money

money makes people want to hold

more money. However,

money usually earns a very

low interest rate and cash -

zero

Wealth Rise Part of an increase in wealth

may be held in the form of

money

Risk Rise, if risk of alternative Higher risk of alternative

assets increase assets makes money more

attractive. (stock market or

real estate bubble)

Liquidity of Alternative Fall If alternative assets become

Assets more liquid, people will want

to hold less money.

Efficiency of Payment Fall People can operate with less

Technologies money

Intellectual property of Douglas McClintock and authors cited above Page 20

Chapter 7: The Asset Market, Money and Prices: Abel, Bernanke, Croushore, Kneebone

Economics 303: OVERHEADS: D. McClintock

ELASTICITIES OF MONEY DEMAND

Income elasticity of money demand

Income elasticity of money demand is the percentage change of money demand

resulting from a 1% increase in real income. For example, if the income elasticity

of money demand is 2/3, a 3 percent increase in real income will increase money

demand by 2% (2/3 by 3% = 2%)

Similarly, the interest elasticity of money demand is the percentage change in

money demand resulting from a 1% increase in the interest rate.

When working with the interest elasticity of money demand, we have to be careful

and to avoid a potential pitfall. To illustrate, suppose that the interest rate increases

from 5% to 6% per year. The interest rate has gone up my 1%.

However, the percentage change is much more than 1%. The percentage change is

actually 20% (1/5 = 0.20 or 20%). If the interest elasticity of money demand is -

0.1, an increase of the interest rate from 5% to 6% reduces money demand by

2%.(-0.1x20% = -2.0%) Note, that if the interest elasticity of money demand is

negative, an increase in the interest rate reduces money demand.

What are the actual values of the income elasticity and interest elasticity of money

demand?

Income elasticity of money demand is around +0.5. A positive income elasticity

implies money demand rises as real income rises. An income elasticity of less than

one (0.5 is less than one) implies that money demand rises less than proportionally

with real income.

Interest elasticity of money demand is about -0.3. A negative value for the interest

elasticity of money demand implies that as the interest rate rises, money demand

falls. In other words, as the interest rate of nonmonetary assets increase (bonds,

term deposits, stocks) people reduce their holdings of money. (As the theory

predicts)

Intellectual property of Douglas McClintock and authors cited above Page 21

Chapter 7: The Asset Market, Money and Prices: Abel, Bernanke, Croushore, Kneebone

Economics 303: OVERHEADS: D. McClintock

VELOCITY AND THE QUANTITY THEORY OF MONEY

Recall from econ 203 that velocity means the number of time that money is used (r

turns over) each period, such as a year.

Velocity can be measure by taking nominal GDP and dividing it by the money

supply. Most measurements use M1+ and M2 as measurements for the money

supply.

Recall from Econ 203: M x V = P x Y

V = (Nom GDP)/nominal money stock

Equals: V = (PxY)/M where PxY is the price level x real GDP = nominal GDP

The concept of velocity comes from one of the earliest theories of money demand,

the quantity theory of money. (Irving Fisher, 1911)

The quantity theory of money asserts that real money demand is proportional to real

income, or

Md/P = kY

Where Md/P is real money demand, Y is real income and k is a constant

The real money demand function L(Y, r + πe) takes the simple form of kY. This

way of writing money demand is based on the strong assumption that velocity is

constant, 1/k – and does not depend on income or interest rates.

Insert figure 7.2 (page 220)

Intellectual property of Douglas McClintock and authors cited above Page 22

Chapter 7: The Asset Market, Money and Prices: Abel, Bernanke, Croushore, Kneebone

Economics 303: OVERHEADS: D. McClintock

However, observations over many years have shown that velocity is not constant.

Why?

1) The popularity of new interest bearing chequing accounts raised the demand

for demand for m1+, which lowers the velocity. (Recall [(PxY)/M] is the

velocity and the denominator M increases at any given level of GDP.

2) But in addition, the quantity theory of money’s assumption that interest rates

do not affect money demand has been refuted by most empirical studies. If

so, this would cause a fall in the velocity of M1+. (Page 221)

(As interest rates fell during the 1990’s and 2000’s, this increased people’s

willingness to hold low interest or zero-interest money, which raised the

demand for M1+ and lower the velocity.)

3) M2 velocity has shown to be more stable. It shows a gradual downward

trend over the period 1975 to 1993 before levelling off. However, M2’s

velocity has been somewhat unpredictable over short periods and most

economists would be reluctant to say it was constant.

Intellectual property of Douglas McClintock and authors cited above Page 23

Chapter 7: The Asset Market, Money and Prices: Abel, Bernanke, Croushore, Kneebone

Economics 303: OVERHEADS: D. McClintock

ASSET MARKET EQUILIBRIUM (page 221)

In this section, we are going to show that the asset market is in equilibrium when

the demand for money equals the supply of money. Remember that we are looking

at the economy in aggregate and not individual markets, such as the labour market

or the market for individual goods and services.

Recall that the asset market is actually a set of markets, in which real and financial

assets are traded. The demand for any asset (say gov’t bonds) is the quantity of the

asset that holders of wealth want in their portfolios. The demand for each asset

depends on the rate of return, risk and liquidity to other assets.

The supply of each asset is the quantity of that asset that is available. At any given

time, the supplies of individual assets are typically fixed, although over time asset

supplies change (gov’t can issue new bonds, firm’s issues new shares, firms mint

more gold, and so on)

Therefore, the asset market is in equilibrium when the quantities of each asset that

holders of wealth demand equal the (fixed) supply of that asset.

Assumptions

In this section, Bernanke and Kneebone adopt an aggregation assumption n in the

asset market. This assumes that all assets may be grouped into two categories,

money and non-monetary assets. (such as bonds – since bonds are interest bearing

assets)

Money includes cash and chequing accounts – or any asset that can be readily used

as a form of payment. All money is assumed to have the same risk and liquidity

and pay the same nominal interest rate.

The fixed nominal money supply of money is M.

Nonmonetary assets include all other assets other than money, such as bonds,

stocks, foreign bank accounts, land and so on. All nonmonetary assets are assumed

to have the same risk and pay the nominal interest rate of r + πe, where r is the

expected real interest rate and πe is the expected inflation rate.

The fixed nominal supply of nonmonetary assets is NM.

Intellectual property of Douglas McClintock and authors cited above Page 24

Chapter 7: The Asset Market, Money and Prices: Abel, Bernanke, Croushore, Kneebone

Economics 303: OVERHEADS: D. McClintock

Although the assumption that assets can be aggregated in to two types ignores

many interesting differences among assets, it greatly simplifies our analysis and

had proven very useful. (Page 222) One immediate benefit of making this

assumption is that if we allow for two types of assets:

“The asset market equilibrium reduces to the conditions that the quantity of

money supplied equals the quantity of money demanded.”

Let’s demonstrate.

Let’s look at the portfolio allocation of someone named Andre De Grasse.

Andre has a fixed amount of wealth that he allocates between money and

nonmonetary assets. (Such as land, bonds or stocks – where assuming that his

running skills are not an asset but rather, a skill to be used later to make gold)

If “md” is the nominal amount of money and “nmd” is the nominal amount of

nonmonetary assets that Andre wants to hold, the sum of Andre’s desired money

holdings and his desired holdings of nonmonetary assets must be his total wealth,

Or

md + nmd = Andre’s total nominal wealth

This equation has to be true for every holder of wealth in the economy.

If we sum this across all holders of wealth in the econo

Md + NMd = Aggregate nominal wealth (equation 7.6)

The equation above states that total nominal wealth in an economy is the sum of

the total demand for money in an economy plus the total demand for nonmonetary

assets.

Intellectual property of Douglas McClintock and authors cited above Page 25

Chapter 7: The Asset Market, Money and Prices: Abel, Bernanke, Croushore, Kneebone

Economics 303: OVERHEADS: D. McClintock

Total Supplies of Money to Aggregate Wealth

Because money and nonmonetary assets are the only assets in the economy,

aggregate nominal wealth equals the supply of money M plus the supply of

nonmonetary assets NM or

M + NM = aggregate nominal wealth (equation 7.7)

Finally, if we subtract equation 7.6 from 7.7, we get

(M + NM) – (Md + NMd)

Equals

(Md – M) + (NMd – NM) = 0

Md – M is the excess demand for money – or the amount that money demand

exceeds money supply and NMd – NM is the excess demand for nonmonetary

assets.

Now suppose demand for money (Md) equals the supply of money (M) so the

excess demand for money Md – M = 0. Then the if demand and supply of

nonmonetary assets (NMd – Nm) must also be zero.

By definition, if quantity supplied and demanded are equal for each type of asset,

the asset market is in equilibrium.

Intellectual property of Douglas McClintock and authors cited above Page 26

Chapter 7: The Asset Market, Money and Prices: Abel, Bernanke, Croushore, Kneebone

Economics 303: OVERHEADS: D. McClintock

ASSET MARKET EQUILIBRIUM

Equilibrium in the asset market is when the quantity of money supplied equals the

quantity of money demanded. This condition is valid whether money supply and

demand are expressed in nominal terms or real terms.

In real terms, recall

M/P = L(Y, r + πe) (Equation 7.9)

The left-hand side is the money supply expressed in real terms. The right-hand side

is the same is the real demand for money Md/P, (and equation 7.9), which states

that the real quantity of money supplied equals the real quantity of money

demanded. This means the asset market is in equilibrium.

Recall that the nominal money supply (M) is determined, in part, by the Bank of

Canada through its open market operations and we treat the expected rate of

inflation (πe ) as fixed. This leaves three variables in the asset market condition

whose values we have not yet specified – that is output Y, the real interest rate and

the price level.(Note: the text assumes at this stage that we are at full employment)

By rearranging the above equation

P = M /L(Y, r + πe ) (equation 7.10)

According to this equation, the economy’s Price level equals the ratio of the

nominal money supply (M) to real demand for money L(Y, r + πe ).

For given values of real output Y, the real interest rate “r” and the expected rate of

inflation, the real demand for money is fixed.

Therefore, the Price level is proportional to the nominal money supply.

This means that if the central bank doubled the money supply, the price level

would double if the other factors remained constant. (fixed)

Intellectual property of Douglas McClintock and authors cited above Page 27

Chapter 7: The Asset Market, Money and Prices: Abel, Bernanke, Croushore, Kneebone

Economics 303: OVERHEADS: D. McClintock

The existence of a close link between the money supply and the price level in an

economy is one of the oldest and most reliable conclusions about macroeconomic

behaviour , having been recognized in some form for hundreds if not thousands of

years. (page 224)

In sum, if people hold money or non-monetary assets. (and we lump all non-

monetary assets under the heading of bonds – since these are interest bearing

assets) then if the money market is in equilibrium, then the non-monetary asset

market must be in equilibrium.

Intellectual property of Douglas McClintock and authors cited above Page 28

You might also like

- NYAM Session Full GuideDocument7 pagesNYAM Session Full Guidedjstro15No ratings yet

- Macroeconomics 9th Edition Abel Solutions ManualDocument20 pagesMacroeconomics 9th Edition Abel Solutions Manualvanessagill15102000sgd100% (38)

- Introduction On MoneyDocument34 pagesIntroduction On MoneyJoseph sunday CarballoNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2: The Demand For Money: Learning ObjectivesDocument12 pagesChapter 2: The Demand For Money: Learning Objectivestech damnNo ratings yet

- Money in The Modern Economy: An IntroductionDocument10 pagesMoney in The Modern Economy: An IntroductionShyam SunderNo ratings yet

- The History of MoneyDocument4 pagesThe History of MoneySultanaQuaderNo ratings yet

- Evolution of MoneyDocument14 pagesEvolution of MoneyRiyaz KhanNo ratings yet

- Reading Lesson 10Document25 pagesReading Lesson 10AnshumanNo ratings yet

- Money and BankingDocument18 pagesMoney and BankingAnnu BidhanNo ratings yet

- Advantages of Owning The Printing Press WrayDocument27 pagesAdvantages of Owning The Printing Press WrayContra_hourNo ratings yet

- Monetary EconomicsDocument44 pagesMonetary EconomicsKintu GeraldNo ratings yet

- Money and Banking: 1. Write A Short Note On Evolution of MoneyDocument5 pagesMoney and Banking: 1. Write A Short Note On Evolution of MoneyShreyash HemromNo ratings yet

- What Is Money?: Mike MoffattDocument6 pagesWhat Is Money?: Mike MoffattJane QuintosNo ratings yet

- Evolution of CurrenciesDocument4 pagesEvolution of CurrenciesViswa KNo ratings yet

- The Nature and Functions of MoneyDocument18 pagesThe Nature and Functions of MoneyCafe MusicNo ratings yet

- Baye Janson Unit 1 Part 1Document28 pagesBaye Janson Unit 1 Part 1Sudhanshu Sharma bchd21No ratings yet

- Unit-1 (Complete) Money Nature Functions and SignificanceDocument12 pagesUnit-1 (Complete) Money Nature Functions and Significanceujjwal kumar 2106No ratings yet

- Lesson 2 LectureDocument17 pagesLesson 2 LectureQueeny CuraNo ratings yet

- Taming Wildcat StablecoinsDocument49 pagesTaming Wildcat StablecoinsForkLogNo ratings yet

- Chapter 3Document8 pagesChapter 3Jr AkongaNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1Document18 pagesChapter 1Mrku HyleNo ratings yet

- 1lmd - Test 01 - Money - 2nd VersionDocument6 pages1lmd - Test 01 - Money - 2nd Versionimen DEBBANo ratings yet

- What Is MoneyDocument6 pagesWhat Is MoneyAdriana Mantaluţa100% (1)

- Exercise 10: Monetary Policy: M1 Vs M2Document3 pagesExercise 10: Monetary Policy: M1 Vs M2Kenon Joseph HinanayNo ratings yet

- The Evolution of MoneyDocument7 pagesThe Evolution of MoneyHà Nhi LêNo ratings yet

- GE Money and BankingDocument110 pagesGE Money and BankingBabita DeviNo ratings yet

- LI Money Concept Function and NatureDocument24 pagesLI Money Concept Function and Naturenainagoswami2004No ratings yet

- Hayek Money by AmetranoDocument51 pagesHayek Money by AmetranoYousef abachirNo ratings yet

- Haircut (PR1)Document17 pagesHaircut (PR1)Monaliza ObusanNo ratings yet

- Problem Set 1Document9 pagesProblem Set 1RibuNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2: The Demand For Money: Learning ObjectivesDocument12 pagesChapter 2: The Demand For Money: Learning Objectiveskaps2385No ratings yet

- Wiley Canadian Economics AssociationDocument20 pagesWiley Canadian Economics AssociationsauravjhaNo ratings yet

- Group4 - Financial MarketsDocument61 pagesGroup4 - Financial MarketsMarie Pearl NarioNo ratings yet

- Macroeconomics 9th Edition Abel Solutions Manual DownloadDocument20 pagesMacroeconomics 9th Edition Abel Solutions Manual DownloadMichael Nickens100% (21)

- Paper 1Document14 pagesPaper 1wzq0308chnNo ratings yet

- Chapter 123 MonetaryDocument8 pagesChapter 123 MonetaryMarlyn T. EscabarteNo ratings yet

- Lecture 7Document4 pagesLecture 7messi csgoNo ratings yet

- Money in MacroeconomicsDocument16 pagesMoney in MacroeconomicsJoab Dan Valdivia CoriaNo ratings yet

- Its Time To Talk About Money Speech by Jon CunliffeDocument13 pagesIts Time To Talk About Money Speech by Jon CunliffeHao WangNo ratings yet

- Lu 2 - CH14Document50 pagesLu 2 - CH14bison3216No ratings yet

- Money: Naturb Functions Significance: Unit ANDDocument10 pagesMoney: Naturb Functions Significance: Unit ANDMadhu kumarNo ratings yet

- Money PDFDocument26 pagesMoney PDFDevaang ShuklaNo ratings yet

- Ii. Comprehension A) Give Answers To The Following Questions: 1. What Is Money and What Do You Know About Its History?Document4 pagesIi. Comprehension A) Give Answers To The Following Questions: 1. What Is Money and What Do You Know About Its History?Anastasia PintescuNo ratings yet

- Mathematics in The Modern World First ModulePDF 2Document13 pagesMathematics in The Modern World First ModulePDF 2jecille magalongNo ratings yet

- How To Travel HimachalDocument15 pagesHow To Travel HimachalShubham ChoudharyNo ratings yet

- History of MoneyDocument6 pagesHistory of MoneySukumar NandiNo ratings yet

- (133-137) Ae-111 (Assignment)Document18 pages(133-137) Ae-111 (Assignment)Asutosh PanigrahiNo ratings yet

- Fiat Money: Confusing The Form of Money With Its Social ContentDocument26 pagesFiat Money: Confusing The Form of Money With Its Social ContentfelipejvcNo ratings yet

- Philosophy of Money and Finance (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy)Document32 pagesPhilosophy of Money and Finance (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy)hallnote08No ratings yet

- 1 - What Is MoneyDocument12 pages1 - What Is MoneyxombakaNo ratings yet

- What Is MoneyDocument11 pagesWhat Is MoneySufyan ButtNo ratings yet

- MoneyDocument6 pagesMoneyMD. IBRAHIM KHOLILULLAHNo ratings yet

- Money in MacroeconomicsDocument14 pagesMoney in MacroeconomicsAmir KhanNo ratings yet

- What Is MoneyDocument9 pagesWhat Is Moneymariya0% (1)

- Solution Manual For Money Banking Financial Markets and Institutions 1st Edition Brandl 0538748575 9780538748575Document36 pagesSolution Manual For Money Banking Financial Markets and Institutions 1st Edition Brandl 0538748575 9780538748575christianjenkinsgzwkqyeafc100% (25)

- Money Banking Financial Markets and Institutions 1st Edition Brandl Solution ManualDocument5 pagesMoney Banking Financial Markets and Institutions 1st Edition Brandl Solution Manualmichael100% (32)

- Full Download Introduction To Finance Markets Investments and Financial Management 14th Edition Melicher Solutions ManualDocument36 pagesFull Download Introduction To Finance Markets Investments and Financial Management 14th Edition Melicher Solutions Manualbeveridgetamera1544100% (33)

- Evolution of MoneyDocument2 pagesEvolution of MoneytashfeenNo ratings yet

- Exploring The Fascinating World of MoneyDocument8 pagesExploring The Fascinating World of MoneyAfiq HaikalNo ratings yet

- CRYPTOCURRENCY empowers Global Financial SystemsFrom EverandCRYPTOCURRENCY empowers Global Financial SystemsNo ratings yet

- Bitcoin and Cryptocurrency Technologies: The Ultimate Guide to Everything You Need to Know About CryptocurrenciesFrom EverandBitcoin and Cryptocurrency Technologies: The Ultimate Guide to Everything You Need to Know About CryptocurrenciesNo ratings yet

- How To Make A Profit WorksheetDocument4 pagesHow To Make A Profit WorksheetivanjonahmuwayaNo ratings yet

- Checking SummaryDocument4 pagesChecking SummaryIrnes BainNo ratings yet

- Features of Export MarketingDocument3 pagesFeatures of Export MarketingThunder 17No ratings yet

- Veet Facing Cultural Challenges in Pakistan: Srinidhi Naeital AnuragDocument16 pagesVeet Facing Cultural Challenges in Pakistan: Srinidhi Naeital AnuragKOTHAMASU STSS SRINIDHI VU21MGMT0500001No ratings yet

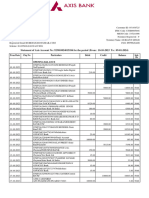

- Account STMT XX5184 09012024Document7 pagesAccount STMT XX5184 09012024Praveen SainiNo ratings yet

- Your Bank Statement Is Ready 2Document53 pagesYour Bank Statement Is Ready 2mariakylie99No ratings yet

- Corporate FinanceDocument3 pagesCorporate Financezairulp1No ratings yet

- Simple Loan Calculator and Amortization Table1Document7 pagesSimple Loan Calculator and Amortization Table1Justine Jay Chatto AlderiteNo ratings yet

- KIM - Kotak Multicap FundDocument34 pagesKIM - Kotak Multicap FunddrstudyteamNo ratings yet

- Chapter 4 MarketingDocument14 pagesChapter 4 MarketingKelly Bianca MontesclarosNo ratings yet

- Krishna File 2Document18 pagesKrishna File 2Ali AhmadNo ratings yet

- Accounting For Share CapitalDocument86 pagesAccounting For Share CapitalJPS JNo ratings yet

- Management of Business TextbookDocument83 pagesManagement of Business TextbookSammy Wizz100% (1)

- 3.business Model and Pricing in Saas: @navdeep - RedefineDocument46 pages3.business Model and Pricing in Saas: @navdeep - RedefineJay ar100% (1)

- 3.1 Modern Firm Based Theories Similarity To PorterDocument40 pages3.1 Modern Firm Based Theories Similarity To Portermargarita vargasNo ratings yet

- Commodities As An Asset Class Essays On Inflation The Paradox of Gold and The Impact of Crypto Alan G Futerman Full ChapterDocument68 pagesCommodities As An Asset Class Essays On Inflation The Paradox of Gold and The Impact of Crypto Alan G Futerman Full Chapterwilliam.byrant522100% (8)

- Tugas 03 - Kunci JawabanDocument5 pagesTugas 03 - Kunci JawabanMantraDebosaNo ratings yet

- HLF409 ConformityNewSubsequentHousingAvailment V03 PDFDocument1 pageHLF409 ConformityNewSubsequentHousingAvailment V03 PDFjonathan magdatoNo ratings yet

- Afar Concept Review Notes Part 1Document13 pagesAfar Concept Review Notes Part 1Alexis SosingNo ratings yet

- ABHADocument30 pagesABHANehal DarvadeNo ratings yet

- Quiz #2 - BreakevenDocument1 pageQuiz #2 - BreakevenNelzen GarayNo ratings yet

- Proposed Loan Terms: Congratulations Dominic Szathmari JR and Mirela SzathmariDocument2 pagesProposed Loan Terms: Congratulations Dominic Szathmari JR and Mirela SzathmariMirela SzathmariNo ratings yet

- E Sign DocDocument26 pagesE Sign DocShaik ShabanaNo ratings yet

- Case Study 1 AnswerDocument4 pagesCase Study 1 AnswerSharNo ratings yet

- English For ManagementDocument11 pagesEnglish For ManagementRifha EviliaNo ratings yet

- ISSUE OF DEBENTURES REVISION QUESTIONS - SolnDocument18 pagesISSUE OF DEBENTURES REVISION QUESTIONS - Solnlalitha sureshNo ratings yet

- Defining Your Strategic Asset AllocationDocument15 pagesDefining Your Strategic Asset AllocationIKER YRIGOYENNo ratings yet

- Corporate Governance Kelompok 2Document16 pagesCorporate Governance Kelompok 2Nabillah ANo ratings yet

- Commerce Project Sem4Document10 pagesCommerce Project Sem4Sahil ParmarNo ratings yet