Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Romano 2016

Romano 2016

Uploaded by

atl.mrtnz1982Original Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Romano 2016

Romano 2016

Uploaded by

atl.mrtnz1982Copyright:

Available Formats

Ital. J. Geosci., Vol. 135, No. 1 (2016), pp. 95-108, 5 figs. (doi: 10.3301/IJG.2015.

01)

© Società Geologica Italiana, Roma 2016

“Per tremoto o per sostegno manco”:

The Geology of Dante Alighieri’s Inferno

MARCO ROMANO (*)

ABSTRACT fourteenth century, ranging from theology, philosophy,

natural science, medicine, politics, ethics, geography,

The purpose of the present paper is to analyse the geological

elements and references found in Dante Alighieri’s Inferno, which astronomy, literature and the arts, bringing authors such

have never been treated in complete and comprehensive manner. as OSSOLA (2012) to define this work as the most crowded

Dante used wisely and in a unique manner the elements of nature, medieval encyclopaedia. In addition to a careful references

especially of landscape, to build the material foundation on which to astronomy (e.g. ANTONELLI, 1865; SANTI, 1915; MANZI,

the fiction of the underworld journey is based. Specific kinds of

rocks, steep cliffs, landslide bodies, lakes of hydrothermal water, 1917; GIZZI, 1974; PECORARO, 1987) between the lines of

waterfalls, become basic material in the hands of the Florentine the Divine Comedy it is possible to find refined references

poet, on which to base metaphors and similes. to medicine (see CERBO, 2001), the organization of living

In Dante’s Inferno there are references to hydrogeology, earth- beings with particular reference to the behaviour of

quakes, mountain structures, deposition of travertine, landscape

modelling, meteorological phenomena, structure of the Earth and of several animals, considered as primary source materials

the entire cosmos. The grandeur and mastery of Dante lies in being for metaphors and similes and therefore often used with

able to communicate, in short lines, the strong separation between ethical implications. This tight integration between

scientific facts of natural phenomena and their use for aesthetic, poetry and science, between sublime lines and natural

poetic, political, and even ethical purposes. In dealing with complex

issues such as the “geophysical equilibrium” and the reason for the world, has led RICCI (1914) to state that, after the ancient

current distribution of land and ocean, Dante does not simply accept world poets, the deep impression exercised on the human

the theories of Aristotle (as stated by several exegetes) but shows a mind by nature essentially begins with Dante.

critical and deep analysis in the field of geology sensu lato, considering The present paper focuses on one of the scientific

and preferring the phenomenal datum to the abstract theories. The

work of Dante and his contemporaries did not impersonate the aspects treated by Dante in his Inferno, and in particular

“dark period” for science, as found in many interpretations of the on the geological issues that have never been considered

Middle Ages, but the cultural context where those questions were in total and organic way in the exegesis found in litera-

posed which served as foundation and propellant for the subsequent ture. The geological subject is here understood sensu lato,

“scientific revolution”.

including a brief mention of the cosmological system,

processes and products shaping the landscape, shape and

KEY WORDS: Dante, Divine Comedy, Geology, Ptolemy,

structure of the Earth, earthquakes, types of rocks directly

Aristotle.

mentioned and some atmospheric phenomena.

According to INGLESE (2002), Dante in his work is

conscious of integrating the philosophy of Aristotle with

INTRODUCTION

the rational basis of Christian thought (an attempt already

present in Albertus Magnus and Thomas Aquinas). Many

“But it’s useless for me to tend to inadequately express

of the interpretations that could be called “geological”

spectacles of such type. Just one pen could paint them: that

sensu lato present in the Commedia are a direct legacy of

of Dante! Great pity that the Florentine poet, instead of

the Aristotelian thought (e.g. Metereologica, ARISTOTLE,

microscopic irregularities of the Apennines, has not known

2000), made available for translation and then by a new

the colossal and sublime horrors of the Alps! What images

interest in ancient world knowledge starting from the

and brushstrokes would have drawn that fine observer of

twelfth and thirteenth centuries. From the combination

nature, which so deeply felt all the more recondite nature

of the Aristotelian-Ptolemaic system and the revealed truth

beauties” (quotation in STOPPANI, 1865). With these words

of the Bible, we find, in the thought of Dante, references

Quintino Sella (1827-1884) geologist, mountaineer and

to a universe entirely created by God, with an Earth that

politician of the Reign of Italy (fig. 1), faced with the geo-

is only 6500 years old (see GIZZI, 1974; nothing could be

logical spectacle of an alpine landscape, goes back with

farther from the concept of “deep time”, major milestone

his mind to the monumental work by Dante, emphasizing

of the geological thought), where earthquakes and oroge-

the ability of the Florentine Poet to translate, into immor-

nesis are caused by the exhalation of the subterranean

tal lines, the most disparate elements of the natural

vapours, the emerged lands are concentrated in the

world. Dante’s Divine Comedy represents a true holistic

northern hemisphere, while the southern hemisphere is

compendium of human knowledge at the beginning of the

occupied entirely by the ocean.

These geological interpretations must be evaluated

within the context in which they were conceived. It is

(*) Dipartimento di Scienze della Terra, “Sapienza” Università di sufficient to consider that the first meaningful and

Roma, P.le A. Moro, 5 - 00185 Rome, Italy. Corresponding author organic reasoning in the field of geology can be traced

e-mail: marco.romano@uniroma1.it back to the genius of Leonardo Da Vinci (see DE

Downloaded from https://pubs.geoscienceworld.org/italianjgeo/article-pdf/135/1/95/3005102/95.pdf

by Univ of Newcastle user

96 M. ROMANO

attitude that perhaps reached its peak with John Wood-

ward (see SARTI, 1988, 2002; VAI, 2003a).

The geological references in Dante’s Inferno should

be read in those specific circumstances and historical

context. As convincingly anticipated by GORTANI (1932)

and highlighted by GRANT (2001), we must avoid the

usual interpretation of the Middle Ages as the Dark Ages

for science to which oppose, as perfect antipode, the

scientific revolution characterizing the sixteenth and

seventeenth centuries. Actually, the work of natural

philosophers between the twelfth and fourteenth cen-

turies has in some way built the substrate, the essential

foundation without which no kind of scientific revolu-

tion could have arisen two or three centuries later in

Western Europe (GRANT, 2001). Among the essential ele-

ments that make the period between the twelfth and

fourteenth centuries crucial to the subsequent develop-

ment of modern science, GRANT (2001) calls into question

the many translations of Arabic and Greek languages into

Latin and the birth of medieval universities. Related to

this last point is the emergence of a class of theologian-

natural philosophers and the acceptance, by the church,

that the works and theories of Aristotle could be studied

and rehearsed. On the basis of this cultural substrate,

where a critical analysis of the problems of natural phi-

losophy overcame the passive acceptance of dogma,

GRANT (2001, p. 111) correctly states: “The scientific revo-

lution was not the result of new questions put to nature in

place of medieval questions. It was, at least initially, more a

matter of finding new answers to old questions, answers

that came, more and more, to include experiments, which

were exceptional occurrences in the Middle Ages” (see also

GRANT, 1997, 2004, 2008, 2011).

The work of Dante should be read and interpreted in

the light of all the above, and in this sense the geological

elements detectable in Dante’s Inferno will be treated.

Fig. 1 - Quintino Sella (1827-1884) geologist, mountaineer and politician The English translation chosen for Dante’s lines is

of the Reign of Italy (from the archive of the Italian Geological Society). that by Mark Musa for The Indiana Critical Edition

(1995) which sometimes is truly inadequate. The transla-

tions of the lines taken from this volume are reported in

LORENZO, 1920; VAI, 1986, 1995, 2003a, 2003b), about a italics. In some cases it has been necessary to give a literal

century after Dante’s death. To see the term “geology” translation of the text, in order to maintain the original

appear in literature for the first time we have to wait the meaning intended by Dante (translations not in italics).

work by Ulisse Aldrovandi in 1603 (VAI, 1995, 2003c;

VAI & CAVAZZA, 2006). Until the end of the seventeenth

century there is still a vigorous debate about the true THE STRUCTURE OF THE EARTH IN DANTE

nature of fossils, with a numerous faction who still

strongly supports the inorganic origin (see NELSON, “Scientific” knowledge at the time of Dante regarded

1968; ACCORDI, 1975, 1976, 1978; SARTI, 1988, 2003; the Earth as a perfect sphere (see ALEXANDER, 1986) with

MORELLO, 2003; VAI, 2003a; LUZZINI, 2009; ROMANO, a circumference of 20,400 miles and a radius of 3250 miles

2013, 2015). Only in 1669 (i.e. 350 years after Dante’s (these are the measures that Dante himself provides

work) the Prodromus by STENO (2010) will introduce directly in the Convivio, see DE MARZO, 1864; BOYDE,

the principles of superposition and original horizonta- 1984), a value reasonably close to those currently

lity of strata (although according to VAI, 1986, 1995 accepted. According to PECORARO (1987), the measures

however, they were already present in Leonardo’s note- used by Dante are not those of Eratosthenes but those of

books). Even at the end of the seventeenth century, Claudius Ptolemy, in agreement with the studies of Posi-

especially in England, the different “Sacred theories of donius and Marinus Of Tyre.

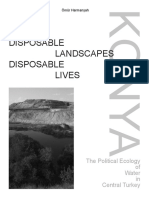

the Earth” or “Theological philosophical systems” such The poet places his Inferno in the northern hemi-

as those of Thomas Burnet (1635-1715), John Ray sphere, and imagine it as an inverted cone, placed

(1627-1705) and William Whinston (1666-1753), found beneath Jerusalem, which gradually narrows reaching its

wide dissemination, with the direct observation of geo- apex in the centre of the Earth (fig. 2). The general struc-

logical phenomena often avoided or discarded alto- ture that can be reconstructed from the hints in the lines

gether, in order to reconcile geological theories with the of the Poet is a kind of real stepped amphitheatre

Holy Scriptures. Such treaties were often studded with (MANCINI, 1861), divided into nine circles gradually less

several quotations from the “Fathers of the Church”, an extensive, which terminate in the deep well of Cogito at

Downloaded from https://pubs.geoscienceworld.org/italianjgeo/article-pdf/135/1/95/3005102/95.pdf

by Univ of Newcastle user

“PER TREMOTO O PER SOSTEGNO MANCO”: THE GEOLOGY OF DANTE ALIGHIERI’S INFERNO 97

the centre of the Earth. In this point, embedded, lies

Lucifer, who for a half projects towards the northern

hemisphere and from the navel (considered to be the

exact centre of the Earth in GIZZI, 1974) downward in the

southern one. According to INGLESE (2002) the position

of Lucifer at the centre of the Earth was common in

several theologians, among which certainly William Of

Auvergne. Prolonging the axis passing through Jerusalem

(actually through Mount Zion according to the analysis

by PECORARO, 1987) with the centre of the Earth, would

reach the point in the southern hemisphere where the

mountain of Purgatory lies entirely surrounded by the

ocean. The Purgatory will be reached by Dante and Virgil

through the natural burella, underground route that leads,

more or less in a straight line, from the legs of Lucifer to

the base of the mountain of Purgatory. In this regard, the

real interpretative revolution carried out by Dante is rep-

resented by removing the Purgatory from the underworld,

as differently found in the legend of the descent of the

Irish knight Owain (narrated in the Chanonica maiora by

Mattheus Parisius and in the Tractatus de Purgatorio

sancti Patricii by Henry Of Saltrey) in the fissure open by

St. Patrick, and make it a sort of stairway to Heaven (DI

FONZO, 1999). In the vision of Dante only the northern

hemisphere is occupied by land mass and is inhabited as

he could not yet have knowledge of Australia, America,

and south-central Africa. The land mass in the northern

hemisphere, represented by Europe, Asia and Africa, con-

stituted the so-called “gran secca” (‘large shoal’), with an

approximately semi-circular profile. The area, believed

inhabited, was enclosed by the triangle which had as its

vertices the “Isole Fortunate” (ancient name for Canary

Islands), the peninsula of Malacca (WSW of peninsular

Malaysia) and the modern Iceland (called Tule at the time

of Dante, see MANZI, 1917). The southern hemisphere was

imagined entirely occupied by the waters of the great

ocean. Dante borrows part of this subdivision directly

from Aristotle who considered the northern hemisphere

as inferior and seat of generatio and corruptio, while the Fig. 2 - Representation of the Inferno as an inverted cone, which

gradually narrows reaching its apex in the centre of the Earth and

southern hemisphere, where Dante places the mountain of divided into nine gradually less extensive circles (from PERTICARI &

Purgatory, was considered nobler (the same conception is MONTI, 1825, p. 2).

also found in Albertus Magnus, see ALEXANDER, 1986).

Differently from the Convivio and Questio de aqua et

terra, which have been conceived as works in prose with The sphere (‘ciel’) of which Dante speaks in these lines

their own organic unity and continuity in the presenta- is that of the Moon, or the heaven, which, in the Ptole-

tion, treatment and resolution of the concepts, the cosmo- maic system, appears to be the closest to the Earth and

logical elements of the Divine Comedy are widespread then the first which includes human beings, considered,

and often hidden behind short lines, sometimes only in agreement with the scala naturae, higher living

hinted to whet the curiosity of the educated reader. beings that “exceed” any other organisms (see also

Starting as early as Canto I, we find the famous GIZZI, 1974 and SAPEGNO, 1983). In the same Canto, a

lines (16-17): “guardai in alto, e vidi le sue spalle/ vestite little further down we find (lines 82-83): “Ma dimmi la

già de’ raggi del pianeta/ che mena dritto altrui per ogni cagion che non ti guardi/ dello scender qua giuso in

calle.” (I raised my head and saw the hilltop shawled/ in questo centro” (But tell me how you dared to make this

morning rays of light sent from the planet/ that leads men journey/ all the way down to this point of spacelessness).

straight ahead on every road). Calling the Sun “planet”, With the expression “questo centro” (literally “in this

that is, a body performing revolutions around the Earth, centre”), Dante means the Inferno, still in agreement

Dante immediately makes us understand his choice of with the cosmology reported briefly above, which saw

the Ptolemaic-Aristotelian system (albeit with some the Earth as the immobile centre of the Universe and

substantial changes and personal interpretations), as the Inferno as the centre of the same Earth. Equally at

cosmological structure of reference. In Canto II, starting Canto XXXII the Poet writes from line 7: “ché non è

with line 76 the Poet writes: “O donna di virtù, sola per impresa da pigliare a gabbo/ discriver fondo a tutto l’uni-

cui/ l’umana spezie eccede ogni contento/ di quel ciel c’ha verso,” (To talk about the bottom of the universe/ the way

minor li cerchi sui,” (O Lady of Grace, through whom it truly is, is no child’s play), thus underlining once again

alone mankind/ may go beyond all worldly things con- the identification of the bottom of the Inferno as the

tained/ within the sphere that makes the smallest circle). absolute centre of the cosmos.

Downloaded from https://pubs.geoscienceworld.org/italianjgeo/article-pdf/135/1/95/3005102/95.pdf

by Univ of Newcastle user

98 M. ROMANO

In Canto V we find a brief reference to the structure volse la testa ov’elli avea le zanche,/ e aggrappossi al pel

conceived by Dante for his Inferno, as an inverted cone com’uom che sale,/ sì che ’n inferno i’ credea tornar anche.

amphitheatre. From line 1: “Così discesi del cerchio pri- (When we had reached the point exactly where/ the thigh

maio/ giù nel secondo, che men luogo cinghia,” (This way I begins, right at the haunch’s curve,/ my guide with strain

went, descending from the first/ into the second circle, that and force of every muscle,/ turned his head toward the

holds less space). From the lines it is possible to go back shaggy shanks of Dis,/ and grabbed the hair as if about to

to the abyss imagined by the Poet, with circular steps, climb-/ I thought that we were heading back to Hell.).

which are narrowed proceeding downward (towards the

edge of the cone). At the end of Canto XXXIV and then of the entire

In Canto XXVI we find the immortal lines of the Cantica, Dante explains through the words of Virgil the

“mad flight” (“folle volo”) of Ulysses, which prompted his formation of the Inferno and of the mountain of Purga-

thirst for knowledge towards the unknown beyond the tory (from line 121):

Pillars of Hercules (from line 112): Da questa parte cadde giù dal cielo;/ e la terra, che pria

di qua si sporse,/ per paura di lui fe’ del mar velo,/ e venne

“O frati”, dissi “che per cento milia/ perigli siete giunti all’emisperio nostro; e forse/ per fuggir lui lasciò qui luogo

all’occidente,/ a questa tanto picciola vigilia/ de’ nostri sensi voto/ quella ch’appar di qua, e su ricorse». (When he fell

ch’è del rimanente,/ non vogliate negar l’esperienza,/ di retro from the heavens on this side,/ all of the land that once was

al sol, del mondo sanza gente. (‘Brothers, ’I said, ‘who spread out here,/ alarmed by his plunge, took cover beneath

through a hundred thousand/ perils have made your way to the sea,/ and moved to our hemisphere; with equal fear/ the

reach the West,/ during this so brief vigil of our senses/ that mountain-land, piled up on this side, fled/ and made this

is still reserved for us do not deny/ yourself experience of cavern here when it rushed upward.).

what there is beyond,/ behind the sun, in the world they call

unpeopled). When he was expelled from the Empyrean, Lucifer

fell on the northern hemisphere (“da questa parte”, on this

In this case, talking about the “mondo sanza gente” side). The land emerging from the surface of the sea

(unpeopled world) Dante refers to the structure of the shrank back “for fear” of the fallen angel forming the

Earth known at his time (see above), inhabited only in the cavity of the Inferno in the shape of an inverted cone (as

northern hemisphere where the “gran secca” was posi- for the impact of a large asteroid). The land moved from

tioned, while it was considered covered by a vast ocean in the impact flowed to the opposite hemisphere (southern

the southern hemisphere (hypothesis clearly stated in the hemisphere) going to form the mountain of Purgatory

Convivio, SAPEGNO, 1983). (see SAPEGNO, 1983; PETROCCHI, 1989; OSSOLA, 2012).

In Canto XXXII Dante speaks of the centre of the

Inferno (from his viewpoint also the centre of the Uni-

verse) and refers to the physical law according to which

GEOMORPHOLOGICAL AND METEOROLOGICAL

all the weights are attracted towards the centre of the

ELEMENTS USED AS SIMILES AND ALLEGORIES

Earth (lines 73 and 74): “E mentre ch’andavamo inver lo

mezzo/ al quale ogni gravezza si rauna,” (While we were get-

The importance of places and the contextualization of

ting closer to the center/ of the universe where all weights

the scene are fundamental elements of the poetic tale.

must converge). A reference to this topic is also found

Dante seems to use real geomorphological metaphors,

starting from line 109 in Canto XXXIV:

using elements of the landscape to transmit the contents of

Di là fosti cotanto quant’io scesi;/ quand’io mi volsi, tu his poetic fiction. Starting from line 13 of Canto I, we find:

passasti ’l punto/ al qual si traggon d’ogni parte i pesi./ E se’ Ma poi ch’i’ fui al piè d’un colle giunto,/ là dove termi-

or sotto l’emisperio giunto/ ch’è contraposto a quel che la nava quella valle/ che m’avea di paura il cor compunto,”

gran secca/ coverchia, e sotto ’l cui colmo consunto/ fu (but when I found myself at the foot of a hill,/ at the edge of

l’uom che nacque e visse senza pecca:/ tu hai i piedi in su the wood’s beginning, down in the valley,/ where I first felt

picciola spera/ che l’altra faccia fa della Giudecca. (and you my heart plunged deep in fear,). In this case, the

were there as long as I moved downward/ but, when I dichotomy is identified by “quella valle” (the valley) which

turned myself, you passed the point/ to which all weight represents the famous “selva oscura” (dark woods) of the

from every part is drawn./ Now you are standing beneath incipit, and the “colle” (hill) also called “dilettuoso monte”

the hemisphere/ which is opposite the side covered by land,/ (joyous mountain). From a symbolic point of view, in all

where at the central point was sacrificed/ the Man whose the classical commentaries to the Commedia the “selva”

birth and life were free of sin./ You have both feet upon a (dark wood) represents a condition of moral and intellec-

little sphere/ whose other side Judecca occupies;). tual aberration, while “il colle” (the hill) represents the

From the original lines, we learn that Dante fell clinging orderly and virtuous life (see also DE MARZO, 1864; GIZZI,

to Virgil along the body of Lucifer toward the midpoint of 1974; PETROCCHI, 1989; INGLESE, 2002). The ascent of

his monstrous body, or centre of the Earth, represented, the hill would then represent a sort of road to recovery

according to SAPEGNO (1983), by the head of the femur. and redemption.

Once past this point, the two pilgrims are already in the Starting from line 76 of the same Canto, the poet

southern hemisphere; then the centre of the Earth, mis- mentions again the “dilettuoso monte” (joyous mountain):

takenly considered the point where the gravity is greatest,

begins to attract Virgil, who tries to climb painfully Ma tu perché ritorni a tanta noia?/ perché non sali il

toward the mountain of Purgatory (from line 76): dilettoso monte/ ch’è principio e cagion di tutta gioia?»/

«Or se’ tu quel Virgilio e quella fonte/ che spandi di parlar sì

Quando noi fummo là dove la coscia/ si volge, a punto largo fiume?» (But why retreat to so much misery?/ Why

in sul grosso dell’anche,/ lo duca, con fatica e con angoscia,/ aren’t you climbing up this joyous mountain,/ the begin-

Downloaded from https://pubs.geoscienceworld.org/italianjgeo/article-pdf/135/1/95/3005102/95.pdf

by Univ of Newcastle user

“PER TREMOTO O PER SOSTEGNO MANCO”: THE GEOLOGY OF DANTE ALIGHIERI’S INFERNO 99

ning and the source of all man’s bliss?/ “Are you then Virgil, In this case, the poet alludes to the crossing of the

are you then that fount/ from which pours forth so rich a Libyan Desert carried out by the army of Cato Of Utica,

stream of words?”). with references taken directly from Lucan (SAPEGNO,

1983). The sand, then, is not accidental or imaginary, but

In addition to the dichotomy dark wood/joyous it is precisely the one characterizing the Libyan desert,

mountain (“selva/dilettoso monte”), in these lines we find read and imagined by the poet probably referring to the

a second allegory derived from the natural landscape. classic texts.

Dante, in fact, compares the talkativeness of his Master In Canto XXIII, Dante refers to a true landslide mass

and guardian Virgil to the spring of a large river, clearly resting on the side of the “bolgia”. From line 133 we find:

conveying the idea of words that literally flow like water.

In Canto II, Virgil says, addressing Beatrice: Rispuose adunque: «Piú che tu non speri/ s’appressa un

non odi tu la pièta del suo pianto?/ non vedi tu la morte sasso che dalla gran cerchia/ si move e varca tutt’i vallon

che ’l combatte/ sulla fiumana onde ’l mar non ha vanto? feri,/ salvo che ’n questo è rotto e nol coperchia:/ montar

(Do you not hear the pity of his weeping,/ do you not see potrete su per la ruina,/ che giace in costa e nel fondo soper-

what death it is that threatens him/ along the river the sea chia». (He answered: “Closer than you might expect,/ a

shall never conquer?). ridge jutting out from the base of the great circle/ extends,

and bridges every hideous ditch/ except this one whose arch

In this case the “fiumana” (river flood) is none of the is totally smashed/ and crosses nowhere; but you can climb

infernal rivers in particular (Acheron, Styx, Phlegethon up/ its massive ruins that slope against this bank”).

and Cogito), but represents evil and sin in general. The

Poet once again uses a naturalistic metaphor, stating In this scene, Virgil asks the devils about a passage that

that the river in question is so bloated and powerful would allow the two pilgrims to get out from the “Bolgia”,

that even the mighty waves of the ocean cannot get the without the help of demons. The demon (Malacoda) then

better of it. talks to them about the “ruina”, or a landslide mass that

In the famous Canto V, that narrates the tragic story form a much less steep slope. This geomorphological

of two lovers Paolo and Francesca from Rimini, in order accident can help the passage of two travellers, working

to describe and contextualize Francesca’s native place, as a more gentle connection for the slope.

the poet says (from line 97): Beyond the examples quoted at length above, Dante,

in several passages of his Inferno, mentions and uses real

Siede la terra dove nata fui/ sulla marina dove ’l Po landscapes of the peninsula, seen during his exile or

discende/ per aver pace co’ seguaci sui. (The place where I was otherwise read and known through the literature. Spe-

born lies on the shore/ where the river Po with its attendant cific references to the landscape and to geological-geo-

streams/ descends to seek its final resting place.). morphological structures can be found-among others:

With “la terra” (the place) the Poet refers to the city of (i) in Canto XVI, where Dante describes the waterfalls of

Rimini, while the “marina” (the shore) indicates the the River Montone near San Benedetto dell’Alpe in the

Adriatic coast. Once again Dante uses a geomorphologi- Romagna Apennines; (ii) in Canto XX, where he describes

cal-hydrogeological picture at a time of great poetry, to the alpine zone between Val Camonica and the locality of

contextualize a scene of the narrative. Garda; (iii) again in Canto XX (from line 73) with a

Other elements and geomorphological processes of detailed description of swampy areas along the course of

the landscape, used as a source of allegory and metaphor, the Mincio River. In Canto XXVIII starting from line 74,

are found in Canto VII (starting from line 22) where the Poet makes direct reference to the Po plain: “se mai

Dante vividly describes the avaricious and the prodigals, torni a veder lo dolce piano/ che da Vercelli a Marcabò

who are forced to come from opposite directions and dichina.” (should you return to see the gentle plain/ declining

collide against each other: from Vercelli to Macabò). Dante conveys a clear picture of

the whole extent of the plain, which spreads from Vercelli

Come fa l’onda là sovra Cariddi,/ che si frange con to the castle of Macabò, built by the Venetians in the

quella in cui s’intoppa,/ così convien che qui la gente riddi. mouth of the Po Primario and holding a defensive func-

(As every wave Charybdis whirls to sea/ comes crashing tion for ships trading between Ferrara and Ravenna. In

against its counter-current wave,/ so these folk here must Canto XXXII, describing the bottom of the Hell (the cen-

dance their roundelay.). tre of created universe) occupied by the frozen lake of

The natural phenomenon used for similarity is the Cogito, the Poet refers to the Danube and the Don, and

“clash” of the waves of the Ionian Sea against those of the mentions the skies of Russia. Dante asserts that the ice

Tyrrhenian Sea in the Strait of Messina, among the that held the lake in a clamp was so thick and hard that it

“gorges” of Scylla and Charybdis. Such phenomenon was would not have cracked even if a whole mountain had

already described in Virgil’s Aeneid (1783), in Ovid’s fallen into the lake (from line 22):

Metamorphoses (1587) and in Lucan (SAPEGNO, 1983). Per ch’io mi volsi, e vidimi davante/ e sotto i piedi un

In Canto XIV Dante speaks of the blasphemers, the lago che per gelo/ avea di vetro e non d’acqua sembiante./

deniers of the gods, sodomites and usurers. The desolate Non fece al corso suo sí grosso velo/ di verno la Danoia in

landscape, represented by an immense desert of sand, is Osterlicchi,/ né Tanaí là sotto il freddo cielo,/ com’era quivi;

again borrowed from the real landscape: che se Tambernicchi/ vi fosse su caduto, o Pietrapana,/ non

Lo spazzo era una rena arida e spessa,/ non d’altra foggia avría pur dall’orlo fatto cricchi. (At that I turned around and

fatta che colei/ che fu da’ piè di Caton già soppressa. (This saw before me/ a lake of ice stretching beneath my feet,/ more

wasteland was a dry expanse of sand,/ thick, burning sand, like a sheet of glass than frozen water./ In the depths of Au-

no different from the kind/ that Cato’s feet packed down in stria’s wintertime, the Danube/ never in all its course showed

other times.). ice so thick, /nor did the Don beneath its frigid sky,/ as this

Downloaded from https://pubs.geoscienceworld.org/italianjgeo/article-pdf/135/1/95/3005102/95.pdf

by Univ of Newcastle user

100 M. ROMANO

superbo,/ e fa fuggir le fiere e li pastori. (and then, above the

filthy swell, approaching,/ a blast of sound, shot through

with fear, exploded,/ making both shores of Hell begin to

tremble;/ it sounded like one of those violent winds,/ born

from the clash of counter-temperatures,/ that tear through

forests; raging on unchecked/ it splits and rips and carries

off the branches/ and proudly whips the dust up in its path/

and makes the beasts and shepherds flee its course!).

With the expression “impetuoso per li avversi ardori”

(violent… …for clash of counter-temperatures) Dante

refers to the generation and increase in intensity of the

wind that is attracted to the areas of rarefied hot air and

with intensity that increases as the thermal imbalance

between the two atmospheric conditions. Even this simi-

larity finds precedents in the classical sources, particu-

larly in Virgil (Aeneid), Statius and Lucan and already

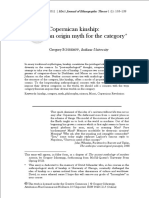

Fig. 3 - “Pania della Croce” in the Apuan Alps (the highest peak in finds a “scientific” explanation in Aristotle (see SAPE-

the “Gruppo delle Panie”) view from the “Voltoline” paths, which GNO, 1983).

leads from Levigliani to Mosceta (photo by Luca Pandolfi).

Still in reference to the wind, in Canto XXXIII the pil-

grim Dante feels a strong wind in proximity of Cogito

(from line 100):

crust here; for it Mount Tambernic/ or Pietrapana would crash

down upon it/ not even at its edges would a crack creak.). E avvegna che, sí come d’un callo,/ per la freddura ciascun

sentimento/ cessato avesse del mio viso stallo,/ già mi parea

From SAPEGNO (1983) we know that, with the term sentir alquanto vento:/ per ch’io: «Maestro mio, questo chi

“Tambernicchi”, Torraca (a popular commentator of the move?/ non è qua giú ogne vapore spento?»/ Ed elli a me:

Commedia) indicated Mount Tambura in the Apuan Alps, «Avaccio sarai dove/ di ciò ti farà l’occhio la risposta,/

which is known in the ancient texts as “Stamberlicchi”. veggendo la cagion che ’l fiato piove». (Although the bitter

SAPEGNO (1983) identifies “Pietra Pana” (‘Pietra Apuana’) coldness of the dark/ had driven all sensation from my face,/

with the present-day Pania della Croce (fig. 3) which as though it were not tender skin but callous,/ I thought I felt

belongs to the same mountain range. the air begin to blow,/ and I: “What causes such a wind, my

As already highlighted by BOYDE (1984), the numerous master?/ I thought no heath could reach into these depths”./

meteorological reminders in the Divine Comedy are drawn And he to me: “Before long you will be/ where your own

primarily from the Metereologica of ARISTOTLE (2000), eyes can answer for themselves,/ when they will see what

without major changes in the interpretations. On the keeps this wind in motion”.).

other hand, as regards the processes and phenomena

which essentially include condensation and evaporation, The Poet is amazed to find a wind in the centre of

theories and explanations provided by Aristotle do not the earth, and then in the centre of the universe in the

basically differ much from the current interpretation. Aristotelian-Ptolemaic system. In accordance with the

Going back to Dante’s Inferno, in Canto V, starting from knowledge of his time, and probably from the reading of

line 31, we find: texts by Ristoro D’Arezzo (see SAPEGNO, 1983), Dante

knows that no wind might blow in the centre of the

La bufera infernal, che mai non resta,/ mena li spirti

Earth, since the Sun’s heat, that raises from the soil the

con la sua rapina:/ voltando e percotendo li molesta. (The

vapours necessary to produce the movement of air, can-

infernal storm, eternal in its rage,/ sweeps and drives the

not get there. The poet once again resorts to poetic inven-

spirits with its blast:/ it whirls them, lashing them with

tion, attributing the wind to the flapping of the colossal

punishment.).

wings of Lucifer, thus proving once again his ability to

With only three lines, the poet succeeds in highlight- skilfully use the data and the scientific knowledge of his

ing a fundamental fact: the infernal storm “mai non time within the narrative texture (and in support of com-

resta”, that is, it never stops and never allows objects pletely fantastic elements such as the flapping of wings of

taken in charge to rest, in opposition to the real storm, the Fallen Angel).

the one observable in the natural world. Then, through

his poetic invention Dante utilizes natural phenomena

and makes them supernatural to his liking, as an instru- STRICTLY GEOLOGICAL REFERENCES

ment of his imaginary construction, however providing,

between the lines, the indication on the actual operation Among the several references to geological processes

and performance of the processes in nature. and products in the Inferno, definitely some of the best

In Canto IX, starting from line 64, the Poet describes, known are those to the earthquakes and seismic pheno-

we might say “scientifically”, the classic phenomenon of a mena in general.

summertime hurricane: The first direct reference is found in the end of Canto

E già venía su per le torbide onde/ un fracasso d’un III, after meeting with Charon, the boatman of Hell who

suon, pien di spavento,/ per che tremavano amendue le collects the shadows in his boat to ferry them across the

sponde,/ non altrimenti fatto che d’un vento/ impetuoso per river. Charon refuses to allow Dante to pass, alive among

li avversi ardori,/ che fier la selva e senz’alcun rattento/ li the dead, and immediately after such denial we find

rami schianta, abbatte e porta fori;/ dinanzi polveroso va (from line 130):

Downloaded from https://pubs.geoscienceworld.org/italianjgeo/article-pdf/135/1/95/3005102/95.pdf

by Univ of Newcastle user

“PER TREMOTO O PER SOSTEGNO MANCO”: THE GEOLOGY OF DANTE ALIGHIERI’S INFERNO 101

Finito questo, la buia campagna/ tremò sí forte, che Fialetre or Ephialtes – one of the giants who attempted

dello spavento/ la mente di sudore ancor mi bagna./ La terra the rebellious climb against Jupiter (found in Virgil and

lagrimosa diede vento,/ che balenò una luce vermiglia/ la Horace, see SAPEGNO, 1983) – the poet states that no

qual mi vinse ciascun sentimento;/ e caddi come l’uom che earthquake was so powerful as the jerky and energetic

’l sonno piglia. (He finished speaking, and the grim terrain/ movement of the giant.

shook violently; and the fright it gave me/ even now in In Canto XII, we find the famous passage of the

recollection makes me sweat./ Out of the tear-drenched land Lavini di Marco, a group of Holocene landslides (OROM-

a wind arose/ which blasted forth into a reddish light,/ BELLI & SAURO, 1988) between Rovereto and Serravalle

knocking my senses out of me completely,/ and I fell as one all’Adige (fig. 4) – placed along the western slope of

falls tired into sleep.). Mt. Zugna Torta – with a volume of about 2×108 m3 and a

covered area of ~6.8 km2 (MARTIN et alii, 2014). MARTIN

The poet describes a real earthquake, and adds et alii. (2014) have calculated a mean age for the Lavini di

another particular (the unleashed wind) which we Marco and Costa Stenda rockslides of 3000 ± 400 years

might call “pseudo-scientific” (but see GUIDOBONI & BP, considering the two slides as simultaneous.

VALENSISE, 2013), linked to the conception and know- The two travellers of Hell are coming down for a

ledge of seismic phenomena in the time of Dante, steep and crumbling walk, that in Dante evokes the image

when seismic phenomena were considered to be driven of the Adige valley. The Poet writes (from line 1):

only by vapours or underground winds. Such theory is

already found in “La Composizione del Mondo” by Era lo loco ov’a scender la riva/ venimmo, alpestro e, per

Ristoro D’AREZZO (1859) published for the first time in quel che v’er’anco,/ tal, ch’ogni vista ne sarebbe schiva./ Qual

1282, and can be traced back to the Arab physician Avi- è quella ruina che nel fianco/ di qua da Trento l’Adige per-

cenna (Ibn Sing, 980-1037), who essentially re-elabo- cosse,/ o per tremoto o per sostegno manco,/ che da cima del

rated the theories expounded by Aristotle. According to monte, onde si mosse,/ al piano è sí la roccia discoscesa,/

ALEXANDER (1986) echoes of such a theory are also ch’alcuna via darebbe a chi su fosse;/ cotal di quel burrato

found in Albertus Magnus and in Ovid. As stated era la scesa; (Not only was that place, where we had come/ to

in BOYDE (1984), in Aristotle these phenomena are descend, craggy, but there was something there/ that made

explained by the theory of “dry exhalations”. According the scene appalling to the eye./ Like the ruins this side of

to such a theory, heat can change both the ground into Trent left by the landslide/ an earthquake or erosion must

dry gas and the water into wet gas. It follows, then, have caused it/ that hit the Adige on its left bank,/ when, form

that if the heat of the sun is sufficient, it can equally the mountain’s top where the slide began/ to the plain below,

produce dry gas and wet gas. According to Aristotle, dry the shattered rocks slipped down,/ shaping a path for a diffi-

exhalations may be generated underground (it is also cult descent/ so was the slope of our ravine’s formation.).

expected that wet exhalations reach the underground As pointed out by SAPEGNO (1983), the term “alpestro”

from the surface) and their passage through the “veins” indicates in Dante a “mountain” in a generic way, without

of the earth would cause earthquakes. Depending on necessarily referring to the alpine system (indeed in some

the feasibility of the passages in the subsoil, the inten- passages it is used to indicate precisely the Apennines; in

sity of the earthquake will be higher or lower and the some cases with the Apennines he instead means the

phenomenon may also occur with the movement of Alps). With regard to the interpretation of landslides at

water and stones. Rovereto, according to SAPEGNO (1983), Dante used as a

The second direct reference to the earthquakes is source a work by Albertus Magnus where the author spoke

found in Canto XXI. Virgil interrogates the demon Mala- of the possible phenomena that trigger landslides, including

coda to find a passage to leave the fifth “Bolgia”. The water erosion (“per sostegno manco”) or earthquakes (“per

demon mixes a series of partial truths and lies and refers tremoto”). Albertus Magnus cites the example of the Lavini

to the two poets that, even if the pass is collapsed, there di Marco and is inclined to consider the erosion that

is a viable passage nearby. Actually this last results in undermines the rocks at their base, rather than a seismic

a lie, since all the arcs above the sixth “Bolgia” collapsed event (SAPEGNO, 1983). It should be emphasized once

at the same time due to the earthquake that, as one will again that, while within the context of the underworld,

discover later, was caused by the death of Christ. From and then of the poetic fiction, the ruin on which the

line 112 we find: pilgrims walk is attributed to a supernatural phenomenon

Ier, piú oltre cinqu’ore che quest’otta,/ mille dugento (the earthquake caused by the death of Christ), in speak-

con sessanta sei/ anni compié che qui la via fu rotta. (Five ing of the real world (the area of Rovereto) Dante once

hours more and it will be one thousand,/ two hundred again provides the interpretations given by the science of

sixty-six years and a day/ since the bridge-way here fell his time, remarking implicitly the difference between

crumbling to the ground.). poetic imagination and phenomenological reality. Starting

from line 28 of the same Canto we find:

In this case Dante provides an important time refe- Cosí prendemmo via giú per lo scarco/ di quelle pietre,

rence for the “seismic phenomenon”. 1266 years and one che spesso moviènsi/ sotto i miei piedi per lo novo carco.

day (minus five hours) have passed since the earthquake (And so we made our way down through the ruins/ of

of Christ’s death caused the collapse of the bridge in the rocks, which often I felt shift and tilt/ beneath my feet from

sixth “Bolgia”. According to some authors (e.g. GIZZI, weight they were not used to.).

1974; SAPEGNO, 1983), this is a key element in support of

interpreters who make Dante’s journey into the under- The poet admirably succeeds in giving the idea of the

world to start in 1300, the anniversary of the death of landslide body, with blocks disconnected from each other

Christ. Another reference to the earthquake is found in which move under his feet. In fact Dante, being alive, can

Canto XXXI starting from line 106, where, speaking of still impress a weight on those stones which have not

Downloaded from https://pubs.geoscienceworld.org/italianjgeo/article-pdf/135/1/95/3005102/95.pdf

by Univ of Newcastle user

102 M. ROMANO

Fig. 4 - The group of Holocene landslides known as “Lavini di Marco” between Rovereto and Serravalle all’Adige: A) and B) Examples of

detachment niche; C) and D) Landslide mass (photos by Massimo Bernardi).

moved anymore since the fall. In the lines that follow, the words of the author “slept a sleep of almost five centuries”

poet sets out clearly the connection between the ruin and (“dormì un sonno di quasi cinque secoli”), with a single

the earthquake connected to the death of Christ. eruption recorded in 1139. With regard to Etna, STOPPANI

Strangely, in Dante’s Inferno there are scarce references (1865) reports that a highly energetic eruption took place

to volcanoes and related phenomena, as one might instead in 1321, the exact year of Dante’s death, or perhaps in 1323

expect considering the classic iconography of the under- as indicated by Gemmellaro (see STOPPANI, 1865).

world dominated by fire. In Canto XII, the poet writes of Again in Canto XIV Dante and Virgil pass through the

the bubbling Phlegethon river, but describes it as a river of sandy desert (“rena arida e spessa”) walking along the

boiling blood. Even though the description could in all bank of a bubbling stream, which derives from Phlegethon

respects remind us of a river of bubbling lava, however, (from line 76):

there is no direct reference to volcanoes. SAPEGNO (1983)

finds a recall and a memory in Virgil’s Aeneid (1783), Tacendo divenimmo là ’ve spiccia/ fuor della selva un

where the Phlegethon is represented by a stream of real picciol fiumicello,/ lo cui rossore ancor mi raccapriccia./

fire. Differently, a direct reference to the volcanoes in the Quale del Bulicame esce ruscello/ che parton poi tra lor le

Inferno is found in Canto XIV where Dante speaks of the pettatrici,/ tal per la rena giú sen giva quello./ Lo fondo suo

Cyclops, who, according to mythology, worked with Vul- ed ambo le pendici/ fatt’era ’n pietra, e’ margini da lato;/ per

can in the forge of Mongibello, ancient name that indicated ch’io m’accorsi che ’passo era lici. (Without exchanging

the Etna volcano. Even in agreement with STOPPANI words we reached a place/ where a narrow stream came

(1865), very likely the direct observation of volcanic gushing from the woods/ its reddish water still runs fear

eruptions would have no doubt helped Dante to represent through me!;/ like the one that issues from the Bulicame,/

the fires of City of Dis and the nature of the boiling whose waters are shared by prostitutes downstream,/ it

Phlegethon with a greater evocative force. According to the wore its way across the desert sand./ This river’s bed and

author, the century of the Florentine Poet coincides with a banks were made of stone,/ so were the tops on both its

phase of rest in the activity of Vesuvius, which, in the sides; and then/ I understood this was our way across.).

Downloaded from https://pubs.geoscienceworld.org/italianjgeo/article-pdf/135/1/95/3005102/95.pdf

by Univ of Newcastle user

“PER TREMOTO O PER SOSTEGNO MANCO”: THE GEOLOGY OF DANTE ALIGHIERI’S INFERNO 103

Here the Poet again uses a real geological setting to

explain to the reader the characteristics of the infernal

stream, immediately giving a clear and instant picture of

what is in front of the two pilgrims of the underworld. Dante,

in fact, mentions the well-known hot springs located near

Viterbo, known by the name of Bullicame (fig. 5). In addition

to bubbling water, typical of sulphurous environments, the

Poet provides another interesting geological evidence.

Describing the infernal stream, the Poet says that, as

for the Bullicame, the bottom and the edges were made of

stone (“Fatt’era ’n pietra, e’ margini da lato”), thus resulting

hardened compared to the sandy sediment just crossed by

the two travellers. In relation to this element, SAPEGNO

(1983) considers absurd the interpretation that the edges

had become as hard as stone due to the incrustations

deposited by the “vermilion boiling”, and deems it not con-

ceivable from the scientific point of view. However, this

seems to be just the correct explanation, since the edges of

the Bullicame active thermal spring are exactly formed by

encrustations of hydrothermal travertine (defined “calcare

incrostante” in STOPPANI, 1915), with deposition of carbonate

catalysed by the action of microbiological activity (see

FOLK, 1993; DI BENEDETTO et alii, 2011). In agreement

with this interpretation of the poetic passage, FOLK (1993)

claims, referring to the lines of the Inferno given above:

“surely one of the earliest described examples of carbonate

diagenesis” (1993, p. 990). Dante once again surprises us,

since he is much closer to the scientific reality of the phe-

nomenon than his modern exegetes.

Returning to the hydrogeological field, in Canto XV,

to describe the hardness of the infernal banks on which

the two travellers are walking, the Poet mentions the

dams built by the Flemish against the impetuosity of the

ocean and levees erected along the river Brenta by the

Paduans, to defend themselves from the floods triggered

by melting snow in spring (from line 1):

Ora cen porta l’un de’ duri margini;/ e ’l fummo del

ruscel di sopra aduggia,/ sí che dal foco salva l’acqua e li

argini./ Quale i Fimminghi tra Guizzante e Bruggia,/

temendo il fiotto che ’nver lor s’avventa,/ fanno lo schermo

perché ’l mar si fuggia;/ e quale i Padoan lungo la Brenta,/

per difender lor ville e lor castelli,/ anzi che Chiarentana il

caldo senta; (Now one of those stone margins bears us on/

and the river’s vapors hover like a shade,/ sheltering the

banks and water from the flames./ As the Flemings, living

with the constant threat/ of flood tides rushing in between

Wissant/ and Bruges, build their dikes to force the sea

back;/ as the Paduans build theirs on the shores of Brenta/

to protect their town and homes before warm weather/

turns Chiarentana’s snow to rushing water;).

According to SAPEGNO (1983), Dante had probably

never directly seen the dams of Flanders. The poet could

have used the more familiar image evoked by the bank of

the Brenta, and then extended his poetic imagination to

the areas of Flanders. For its incisive character, this

episode of the Inferno captures also the interest of

Charles Lyell, which makes mention of it in the part of

Fig. 5 - The Bullicame active thermal spring near Viterbo (central

Italy): A) and B) One of the hydrothermal pools; the “hardened” edges

described by Dante are clearly visible, made of hydrothermal travertine

encrustations; C) A particular of the hydrothermal travertine deposit

(photos by Valentina Rossi).

Downloaded from https://pubs.geoscienceworld.org/italianjgeo/article-pdf/135/1/95/3005102/95.pdf

by Univ of Newcastle user

104 M. ROMANO

his Principles which deals of hydrogeology and river regu- stratigraphic term are already found in the Musaeum

lation in the broad sense (see below). Metallicum by Ulisse Aldrovandi (published posthu-

In Canto XIX, Dante and Virgil observe at the third mously in 1648, see VAI & CAVAZZA, 2006) and in a 1768

“Bolgia” the simonists – those who sold sacred things for work by Giovanni Targioni Tozzetti (see below). Thus,

cash in life, in imitation of Simon Magus – driven into the probably in Dante is found one of the first – if not exactly

ground upside down. Dante is attracted to the hole the first – written references to the geological term.

assigned to the Popes, where for the moment Nicholas The English translation is therefore unsatisfactory, con-

III, which led to the illegal enrichment of the Orsini fam- sidering the term “macigno” as simply “rock” and thus

ily, remains upside down. Soon his place will be taken by losing its true shade of meaning.

Boniface VIII (who will then be replaced by Clement V) In Dante’s Inferno could not absolutely miss a reference

and Nicholas III will slide down where the previous to the famous Carrara marble. The poet mentions it in

simonist popes are. From line 73 we find: Canto XX where, in the fourth Bolgia, the magicians, sooth-

Di sotto al capo mio son li altri tratti/ che precedetter me sayers and astrologers are punished. From line 46 we find:

simoneggiando,/ per le fessure della pietra piatti. (Beneath my Aronta è quei ch’al ventre li s’atterga,/ che ne’ monti di

head are pushed down all the others/ who came, sinning in Luni, dove ronca/ lo Carrarese che di sotto alberga,/ ebbe

simony, before me,/ squeezed tightly in the fissures of the rock). tra’ bianchi marmi la spelonca/ per sua dimora onde a

guardar le stelle/ e ’l mar non li era la veduta tronca. (Back-

As reported by Dante, the old popes, once slipped ing up to this one’s chest comes Aruns/ who, in the hills of

down, are arranged horizontally between the rocks. With Luni, worked by peasants/ of Carrara dwelling in the val-

the term “piatti” SAPEGNO (1983) means “flat” between ley’s plain,/ lived in white marble cut into a cave,/ and from

the fissures of the rocks (not squeezed as in the transla- this site where nothing blocked his view/ he could observe

tion by MUSA (1995). It is likely, however, that even using the sea and stars with ease.).

the term “fissures”, Dante had actually in mind any kind

of fissures breaking the rocks. Aronte or Arunte is the Etruscan who predicted the

war between Pompey and Caesar and the victory of the

latter, while “Luni” represents the ancient Etruscan town

REFERENCES TO SPECIFIC TYPES OF ROCKS situated at the mouth of the Magra River from which

Lunigiana took its name. The interesting term is “ronca”

Although geological elements of the landscape, inclu- that would indicate the activity of deforesting and tilling

ding the types of sediment or rock walls and ravines of the land occupied by the people of Carrara, when the

the infernal amphitheatre, continuously recur as a struc- marble industry had not yet reached its importance

tural element of Dante’s construction, in some cases a (see SAPEGNO, 1983). In fact, the metamorphic limestone

direct reference is made to particular kinds of rocks that is not quoted as carved stone, but as a constituent of

characterize the Italian territory. For example, in Canto the cave of Arunte, in a still wild and rugged landscape.

XV the Poet, launching a historic invective against his Among the rocks mentioned in the Inferno, in Canto

Florence (and in particular against the Florentines) by XXIV we find reference to the “elitropia” or “eliotropio”

which he was exiled and forced to flee, states (from line 61): (heliotrope). Dante and Virgil arrive at the top of the “Bol-

Ma quello ingrato popolo maligno/ che discese di Fiesole gia” embankment, and, looking down, see the spectacle of

ab antico,/ e tiene ancor del monte e del macigno (But that snakes tangled in large quantities; among the snakes, naked

ungrateful and malignant race/ which descended from Fiesole and frightened, roams the race of robbers. From line 91:

of old,/ and still have rock and mountain in their blood,). Tra questa cruda e tristissima copia/ correan genti nude

e spaventate,/ senza sperar pertugio o elitropia:/ con serpi le

In this famous passage, the Poet mentions the term man dietro avean legate; (Within this cruel and bitterest

“macigno” most likely to denote a characteristic element abundance/ people ran terrified and naked, hopeless/ of

of the landscape in which the “ungrateful” Florentine finding hiding-holes or heliotrope./ Their hands were tied

people lived, and follows the legend that Florence was behind their backs with serpents).

founded by the Romans after the destruction of Fiesole

which had chosen to side with the faction of Catiline. In the lapidary, the heliotrope (or Lapis Heliotropius

SAPEGNO (1983), using the exegesis of Boccaccio, considers in CORSI, 1828) – a variety of chalcedony, i.e. compact

the term “macigno” as an attribute and not as a noun, i.e. microcrystalline quartz – was referred to as a stone, having

to indicate the hard and not pliable character of the civil the virtue of making those who possessed it invisible and

custom. Actually, it is not to be ruled out that, by men- heal from the venom of snakes. We find references to the

tioning the term “monte” first, Dante refers precisely to heliotrope in Pliny (see CORSI, 1828), in Boccaccio in the

the kind of rocks represented by large outcrops in the “Novella di Calandrino” and in the Decameron, and it is

Tuscan territory (but also in Liguria, Emilia Romagna, mentioned several times in works on natural history or of

Umbria and Lazio). “Macigno” is in fact a classic term strictly geological issue (e.g. BOSSI, 1795, 1819; BRU-

of Italian lithostratigraphy, which indicates a very thick GNATELLI, 1796; BROCCHI, 1811; CORSI, 1828; WINCKEL-

succession – up to 3000 m – formed in large part by fine MANN, 1831; CATULLO, 1833).

to very coarse silicoclastic sandstone. These deposits are

now formally referred to as Macigno Formation, with a

Late Rupelian to Medium-Late Aquitanian age (FALORNI, REFERENCES TO DANTE’S INFERNO

2014). According to FALORNI (2014) the use of the term is IN THE GEOLOGICAL LITERATURE

very old, with the use in the official cartography as early

as the first edition of the Foglio 97 by Lotti and Zaccagna References to the Divine Comedy and in particular to

in 1903. In fact, references to the “Macigno” as a litho- Dante’s Inferno are found in several works dealing with

Downloaded from https://pubs.geoscienceworld.org/italianjgeo/article-pdf/135/1/95/3005102/95.pdf

by Univ of Newcastle user

“PER TREMOTO O PER SOSTEGNO MANCO”: THE GEOLOGY OF DANTE ALIGHIERI’S INFERNO 105

naturalistic or strictly geological issues. An exhaustive attempt to reconcile the new discoveries of the geology of

search in these terms is almost impossible and is beyond his time with the revealed truth of the Sacred Scriptures

the scope of the present paper. Only a few examples will (see ROMANO, 2015).

then be provided with direct quotation to Dante’s work, In describing the hydrographical status of the River

basically between the 18th and 19th centuries. Adige, and the alleged diversion of the watercourse over

Although GARBASSO (1916) argues that the 18th cen- time, Tommaso Antonio CATULLO (1834, p. 26) mentions

tury did not understand Dante and that only during the once again the Dantesque ruin of Lavini di Marco, argu-

19th century the Divine Comedy became the object of ing that the enormous mass of the landslide must have

passionate study by scientists (see also FRIEDERICH, substantially changed the course of the river.

1949 and PETROCCHI, 1989 for the decline of Dante’s References to the Divina Commedia are also found in

fortunes between the end of the 16th and the beginning the famous Principles of Geology. Charles Lyell spent a lot

of the 18th century), some references to the Florentine of time in Italy (VAI, 2009, p. 197) and thoroughly knew

Poet are found in the work of Italian scientists of the the work of Dante. Very likely, Lyell was introduced into

18th century. the world of the Florentine poet almost by osmosis, since

A first reference is found in Antonio VALLISNERI his father translated and commented DANTE’s Vita Nova

(1721) where, in disagreement with the theory of a single and Convivio, including in his comments also long discus-

flood (see VAI, 2003a; LUZZINI, 2009; ROMANO, 2013, sions on the Divine Comedy (LYELL, 1842). A first reference

2015), he states that the plants and trees often found to Dante is found in the historical account of the Princi-

buried underground need not necessarily be linked to a ples (1867, tenth edition), and in particular in the section

deluge or flood, but may have been swept away and that considers the contributions in geology by James Hut-

buried even by landslide movements (defined “lavine” or ton. According to Lyell, one of the major contributions of

“ammottamenti” in the original text, VALLISNERI, 1721, the Scottish geologist is the recognition of the granite as

p. 53). In this regard, Vallisneri literally quotes the lines an intrusive rock and not as a sedimentary rock. As

of Dante of Canto XXII already discussed above. reported by Lyell, Vallisneri brought to light that certain

Another reference is found in Targioni TOZZETTI types of rock were completely deprived of organic

(1768) where, speaking of the hardness of different types remains, and so were interpreted as deposits formed

of rocks in Tuscany, the author states that the hardest before the creation of living beings (such rocks were

ones are defined “Forti” or “Macigni”, remarking that the called “primitive”). Concerning this hypothesis, LYELL

last term had already been used by Dante in his Inferno. (1867, p. 76) wrote: “The same tenet was an article of faith

In the text Targioni Tozzetti quotes literally from the pas- in the school of Freyberg: and if anyone ventured to doubt

sage pronounced by Brunetto Latini (Dante’s teacher and the possibility of our being enabled to carry back our

mentor) in Canto XV of Inferno, already discussed above, researches to the creation of the present order of things,

and says that the term “Macigno” is very old and with the granitic rocks were triumphantly appealed to. On

such a word were indicated, for many centuries, the them seemed written, in legible characters, the memorable

“Pietre di Fiesole” (Stones of Fiesole). In the same work inscription: “Dinanzi a me non fuor cose create/ se non

Targioni Tozzetti speaks of the locality “Bagni di Monte eterne’ ” (Before me nothing but eternal things/ were made,).

S. Giuliano” once called “Monte Pisano”, of which, in The famous lines of Dante’s Inferno are then used by Lyell

agreement with the author, Dante speaks in Canto as metaphorical warning for those who dared question

XXXIII of the Inferno (from line 28): “Questi pareva a me the primitive character of the granitic rocks, before the

maestro e donno,/ cacciando il lupo e’ lupicini al monte/ crucial contribution of Hutton.

per che i Pisan veder Lucca non ponno.” (I dreamed of this A second reference to the Inferno in the Principles is

one here as lord and huntsman,/ pursuing the wolf and the found in the section where Lyell writes about the practice

wolf-cubs up the mountain/ which blocks the sight of of river embankment, using as an example the rivers Po

Lucca from the Pisan). Even according to SAPEGNO and Adige. The author reports that the Po and the Adige

(1983), the “monte” (mountain) would represent the over time have changed several times their course and, to

Monte Pisano or of S. Giuliano. prevent flooding and destruction of countries, a general

In 1824 Antonio Bellenghi publishes his “Ricerche system of embankment has been adopted, with the major

sulla Geologia” (Research on Geology) in which he accepts rivers and their tributaries “now confined between high

the hypothesis of species extinctions – already present in artificial banks” (1867, p. 423). However, explains Lyell,

BROCCHI (1814) – and considers catastrophic events, although a greater portion of sediment reaches the sea

with a complete extinction followed by new creations of with such a system, part of the sediment that naturally

species (see ROMANO, 2015). As already seen in VALLI- would be deposited for flooding in the alluvial plain are

SNERI (1721), also BELLENGHI (1824) criticizes the instead deposited on the bottom of the channel, thus

hypothesis of a single deluge, and uses the ammonites as decreasing its section. So, in order to prevent the

elements that indicate, necessarily, marine deposits older enlarged rivers to overflow with catastrophic results with

than “mosaic flood” (ROMANO, 2015). BELLENGHI uses a the arrival of spring, it is necessary to further raise the

line from Dante’s Inferno as an opening of his work: “è chi embankments. According to Lyell the practice of embank-

creda/ più volte il mondo in caòs converso;” (whereby, ment was adopted in Italy as early as the thirteenth cen-

some have maintained, the world/ has more than once tury, and, as proof of his claim, he cites the passage of

renewed itself in chaos; Inferno, Canto XII). The term Dante’s Inferno – already described above – in which the

“chaos” is probably mentioned to allude and put the right poet speaks of the dams built by the Flemish and by the

emphasis on the various catastrophic periods, needed to Paduans along the river Brenta (Inferno, XV, 1-9).

get rid of some species and make others appear, as acts of Numerous and repeated citations and references to

deliberate creation (theistic conception). All the intel- Dante’s Inferno are found in the famous work “Il Bel

lectual efforts of the author are aimed, essentially, at an Paese” by the priest, geologist and Italian patriot Antonio

Downloaded from https://pubs.geoscienceworld.org/italianjgeo/article-pdf/135/1/95/3005102/95.pdf

by Univ of Newcastle user

106 M. ROMANO

STOPPANI (1915, first edition published in 1876). In the to the underworld is based. The grandeur and mastery of

work, organized in the form of 32 educational conversa- Dante lies precisely in being able to communicate, in

tions about geology and natural sciences in front of a fire- short lines, or with a minimum sequence of words, the

place, Stoppani displays, from north to south, all the natu- strong separation between scientific facts of the natural

ralistic and landscape beauties of Italy, using in several phenomena and their licentious use for aesthetic, poetic,

passages direct quotations of Dante’s lines. We could even political, and even ethical purposes. In the famous Canto

say that, for various conversations, the author seems XII, Dante ascribes the collapse of the landslide in Hell

almost to follow the route envisioned by the Florentine (“ruina”) to the earthquake occurred at the death of

Poet, reporting the real places used by Dante as similari- Christ. However, speaking of landslides in the real world,

ties for his Comedy. The quotations are really numerous in particular of the area of Lavini di Marco, by the simple

and only a few will be listed here: (i) describing a land- phrase “per tremoto o per sostegno manco” (an earthquake

slide, Stoppani refers to the Dantesque ruin of Canto XII; or failed support), he immediately made it clear that the

(ii) writing of a meeting of the Italian Alpine Club (of scientific interpretation of this phenomenon may be

which he was the first president) during which it was related to two different processes: the earthquake on the

necessary to cross a lake, the author cites the boat of one hand, and the fall by gravity due to the erosion of the

Charon and the episode of Canto III; (iii) mentioning slope base on the other hand (thus not considering at all

some frogs that had got frozen in a vase where they were the supernatural cause). Similarly in Canto V, with the

put for an experiment, he cites the damned that Dante expression “La bufera infernal, che mai non resta” (The

imagined frozen and completely immersed in the ice of infernal storm, eternal in its rage) he wishes to emphasize

the Giudecca in Canto XXXIV; (iv) he mentions several the supernatural character of the storm of the under-

times the lines of Count Ugolino talking about the world, opposing to it the storms of the real world, that do

cramped cabin of a steamer and about the island of Gor- not continue indefinitely but find an end with the chang-

gona; (v) treating of pitch and oils, in particular in rela- ing weather conditions. As a further and last example, we

tion to the Lesser Antilles, Stoppani literally mentions can mention the wind felt by Dante in Canto XXXIII. The

and quotes the famous passage of the arsenal of Venice in Poet says astonished: «Maestro mio, questo chi move?/ non

Canto XXI (the episode is also mentioned on p. 297, when è qua giù ogne vapore spento?» (“What causes such a wind,

the author speaks of “mud volcanoes”); (vi) treating of my master?/ I thought no heath could reach into these

Carrara marble, he quotes the famous passage of the depths”). Dante clearly shows to know the “scientific”

Inferno about the cave Aurunte. interpretation of Aristotle, who saw the wind as an essen-

The Italian geologist and paleontologist Paolo Euge- tially superficial phenomenon, where the heat of the sun

nio Vinassa de Regny (1871-1957) in addition to the great can warm air masses differently triggering their move-

contribution in the field of earth sciences and natural ments. In the centre of the Earth, away from the heat of

sciences – with hundreds of publications ranging from the Sun, these processes cannot be activated and Dante

geochemistry to botany – was also a literary critic of resorts to the supernatural explanation of the fluttering

The Divine Comedy by Dante, with works that are still wings of Lucifer. However, notice again, the Poet resorts

reprinted. The best known contribution in this area is the to this imaginative invention only after clearly showing

volume “Dante e Pitagora” (VINASSA DE REGNY, 2013) his knowledge of the scientific explanation of the natural

where the author discusses in depth the Pythagorean phenomenon.

legacy in the work of Dante and meaning, in the poem, of Although in some interpretations or text passages

the magical symbolism associated to the numbers. Dante’s work may even sound ridiculous compared with

current knowledge in geology, we cannot afford the luxury

of being superficial. For example, the explanation of the

CONCLUDING REMARKS formation of the Hell cavity and of the Mountain of Pur-

gatory due to the falling of Lucifer, with the land moving

In the present paper, the geological elements and for “fear” of the rebel, might seem laughable, and could

references found in Dante’s Inferno have been briefly lead to the conclusion that Dante, after all, has never

treated, showing, once again, what an impressive work really tackled the problem of the structure of the Earth

the Divine Comedy is, a titanic and kaleidoscopic work and why the ocean and sea have different distributions.

able to embrace all human knowledge at the beginning of Nothing could be farther from the truth. DANTE philoso-

the fourteenth century. Speaking of the geological topic pher – and especially we could say natural philosopher –

sensu lato, in Dante’s Inferno there are references to in the Convivio (ALIGHIERI, 1986) and even more in Que-

hydrogeology, earthquakes, structure of the mountains, stio de aqua et terra (ALIGHIERI, 1986) directly and deeply

deposition of travertine and hydrothermal water, land- addresses the issue of the structure of the Earth and of

scape modelling and landslide events, as well as to the the distribution of emerged land and sea. According to

most diverse meteorological phenomena, to specific types the Aristotelian theories, the ground, heavier than air and

of rock, to the structure of the Earth and even of the water, had to go down to the centre of the Earth, and

entire cosmos. All these elements are not reported in long form a perfect concentric sphere with no gaps. However,

and tedious academic discourse, but are embedded in this theory was strongly falsified by observation of the

poetic lines of rare refinement and beauty, often only real world, where land and oceans alternate each other

mentioned in order to stimulate the curiosity of those (and where the water, considered lighter, and then form-

who want to grasp their deeper meaning. ing a sphere set higher, is often topographically much

Dante used wisely and in a unique way the elements lower in relation to land). In his reconstructions and

of the natural world and of the landscape seen around interpretations, Dante insists on the principle of “geocen-

Florence and while travelling during his exile, to build the tric equilibrium”, where volumes and voids on the two

foundational material on which the fiction of the journey opposite hemispheres must be specular in order to com-

Downloaded from https://pubs.geoscienceworld.org/italianjgeo/article-pdf/135/1/95/3005102/95.pdf

by Univ of Newcastle user

“PER TREMOTO O PER SOSTEGNO MANCO”: THE GEOLOGY OF DANTE ALIGHIERI’S INFERNO 107

pletely offset each other (see PECORARO, 1987 for a com- ANTONELLI G. (1865) - Sulle dottrine astronomiche della Divina Com-

plete discussion on this topic; it is natural to think of the media, Ragionamenti. Firenze, Tipografia Calasanziana. 96 pp.

modern theory of isostasy, although a too close relation- ARISTOTELE (2000) - Meteorologica. Lampi di Stampa. 192 pp.

ship could be misleading; see also VAI, 2006). In the BELLENGHI A. (1824) - Ricerche sulla geologia. Rovereto, dall’I.R.

model of “geocentric equilibrium”, the land concentrated Stamperia Marchesani. 124 pp.

in one hemisphere represented a serious problem since BOSSI L. (1795) - Spiegazione di una raccolta di gemme incise dagli

antichi, con osservazioni riguardanti la Religione, i Costumi e la

there was not an equivalent mass in the opposite hemi- Storia dell’Arte degli Antichi Popoli. Milano, nel’Imperial Monist.

sphere as balancing mass (as already stated, the southern Di s. Ambrogio Magg. 488 pp.

hemisphere was considered completely filled by the BOSSI L. (1819) - Dizionario portatile di geologia, litologia e mineralogia.

ocean). In order to explain this imbalance, Dante resorts Milano, presso Gio. Pietro Giegler. 428 pp.

to the attraction of the Fixed Stars, which would have BOYDE P. (1984) - L’uomo nel cosmo. Filosofia della natura e poesia

caused, with their traction, the lifting of the lands in the in Dante. Bologna, il Mulino. 485 pp.

northern hemisphere (even in that case the mind goes to BROCCHI G. (1811) - Memoria mineralogica sulla Valle di Fassa in

current theories of solid tides and to the influence of the Tirolo. Milano, per Giovanni Silvestri. 233 pp.

Moon and Sun on plate tectonics and geodynamics; see BROCCHI G. (1814) - Conchiologia Fossile Subapennina con Osserva-

RIGUZZI et alii, 2010; DOGLIONI et alii, 2011). This example zioni Geologiche sugli Apennini e sul Suolo Adiacente. 2 vols.

indicates how Dante does not simply accept the theories Milano, Stamperia Reale. 240 pp.

of Aristotle, using and transmitting them in his writings, BRUGNATELLI L. (1796) - Elementi di chimica appoggiati alle più recenti

scoperte chimiche e farmaceutiche. Pavia, presso Baldassare

but analyses deeply and critically the issues related to Comino. 255 pp.

geology sensu lato, considering and preferring the phe-

CATULLO T.A. (1833) - Elementi di mineralogia applicati alla medicina

nomenal datum (e.g. the actual distribution of dry land e alla farmacia. Volume I. Padova, coi Tipi della Minerva. 272 pp.

and of the ocean compared to the model of Aristotle’s CATULLO T.A. (1834) - Osservazioni sopra i terreni postdiluviani delle

concentric spheres) to the completely abstract theories. provincie austro-venete. Padova, coi Tipi della Minerva. 95 pp.

Concluding, the monumental work of the Divine CENTOFANTI S. (1838) - Un preludio al corso di lezioni su Dante Alighieri.

Comedy is a window open on the 14th century, on how Firenze, coi Tipi della Galileiana. 51 pp.

the authors of that period assimilated the knowledge of CERBO A. (2001) - Poesia e scienza del corpo nella Divina Commedia.

the philosophers of the ancient world, and how new Napoli, Libreria Dante & Descartes. 168 pp.

thoughts and new bases formed the necessary foundation CORSI F. (1828) - Delle Pietre Antiche. Roma, Da’ Torchi di Giuseppe

for subsequent scientific revolution. Salvucci e Figlio. 432 pp.

As our predecessor Quintino Sella, in front of a geo- DE LORENZO G. (1920) - Leonardo da Vinci e la Geologia. Bologna,

logical landscape admirably described by the pen of Nicola Zanichelli. 195 pp.

Dante, we will whisper the immortal lines of the summo DE MARZO A.G. (1864) - Commento su la Divina Commedia di Dante

poeta, having in mind the scientific explanation of the Alighieri. Firenze, Grazzini Giannini e C., 1120 pp.