Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Otero Et Al 2011 Elevated Alkaline Phosphatase in Children An Algorithm To Determine When A Wait and See Approach Is

Uploaded by

mokgabisengOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Otero Et Al 2011 Elevated Alkaline Phosphatase in Children An Algorithm To Determine When A Wait and See Approach Is

Uploaded by

mokgabisengCopyright:

Available Formats

Clinical Medicine Insights: Pediatrics

Open Access

Full open access to this and

thousands of other papers at

T e c h n ical A d v a n c e

http://www.la-press.com.

Elevated Alkaline Phosphatase in Children: An Algorithm

to Determine When a “Wait and See” Approach is Optimal

Jaclyn L. Otero1, Regino P. González-Peralta2, Joel M. Andres2, Christopher D. Jolley2,

Don A. Novak2 and Allah Haafiz2

Division of Pediatric Education and Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition, University of Florida,

1

PO Box 100296, Gainesville, Florida 32610-0296, USA. 2Department of Pediatrics, University of Florida, PO Box 100296,

Gainesville, Florida 32610-0296, USA. Corresponding author email: haafiab@peds.ufl.edu

Abstract: Due to the possibility of underlying hepatobiliaryor bone diseases, the diagnostic work up of a child with elevated alkaline

phosphatase (AP) levels can be quite costly. In a significant proportion of these patients, elevated AP is benign, requiring no intervention:

hence, known as transient hyperphosphatasemia (THP) of infants and children. A 27-month old previously healthy Caucasian female was

found to have isolated elevation of AP four weeks after the initial symptoms of acute gastroenteritis. One month later, when seen in hepa-

tobiliary clinic, signs and symptoms of gastrointestinal, hepatobiliary, or bone disease were absent and physical examination was normal.

The diagnosis of THP was made, and, as anticipated, AP levels normalized after four months. Using this case as an example, we suggest

an algorithm that can be utilized as a guide in a primary care setting to arrive at the diagnosis of THP and avoid further tests or referrals.

Keywords: hyperphosphatasemia, abnormal liver enzymes, gamma-glutamyl transferase, 25-OH-vitamin-D

Clinical Medicine Insights: Pediatrics 2011:5 15–18

doi: 10.4137/CMPed.S6872

This article is available from http://www.la-press.com.

© the author(s), publisher and licensee Libertas Academica Ltd.

This is an open access article. Unrestricted non-commercial use is permitted provided the original work is properly cited.

Clinical Medicine Insights: Pediatrics 2011:5 15

Otero et al

Introduction gastroenteritis resolved in one week, mild loose stools

It is relatively common for primary care physicians to persisted for a month prompting blood tests performed

encounter children with elevated alkaline phosphatase by the primary care physician. These indicated WBC

(AP) levels. Given the possibility of underlying asymp- 6.9 × 109 cells per liter, hemoglobin 11.9 g/dl, platelet

tomatic hepatobiliary diseases, these patients are usu- count 372 × 109 per liter, neutrophil count 34.1%, lym-

ally referred to either a pediatric gastroenterologist or phocytes 50.7%, monocytes 13.4%, eosinophils 1.4%,

a hepatologist for evaluation and management. Simi- basophils 0.4%, and erythrocyte sedimentation rate

larly, to determine the cause, apart from referral to a 4 mm/h. Biochemical investigations revealed sodium

specialist, the diagnostic work-up can be quite costly, 142 mmol/L, potassium 4.9 mmol/L, bicarbonate

reflecting the broad scope of hepatobiliary and skel- 23 mmol/L, chloride 103 mmol/L, magnesium 1.9 mg/

etal diseases known to be associated with AP eleva- dl, phosphate 4.4 mg/dl, calcium 9.9 mg/dl, creatinine

tion. Importantly, in a significant proportion of these 0.37 mg/dl. The hepatic biochemical tests were normal

patients, elevated AP is benign, and gradually resolves with a total protein 6.4 g/dl, albumin 4.4 g/dl, aspar-

without intervention, questioning the rationale for an tate transaminase 37 U/L (0–37), alanine transaminase

exhaustive evaluation of every patient with this bio- 17 U/L (0–41), and gamma-glutamyl transferase 9 U/L

chemical abnormality. The benign elevation of AP is (5–61). Alkaline phosphatase was abnormal at 1510 U/L

referred to as transient hyperphosphatasemia (THP), (61–320); the isoenzyme fractionation revealed liver-

a condition most commonly observed in infants and specific-AP-activity of 374 U/L and bone-specific-

children younger than 5 years of age without evidence AP-activity of 456 U/L. Calcidiol (25-OH-vitamin-D)

of bone, gastrointestinal or liver disease on history, level was 49.7 ng/ml (30–100).

physical examination or laboratory investigations. When the patient was seen at the hepatobiliary

Furthermore, this condition has no long-term adverse clinic, signs and symptoms of liver or bone disease

consequences.1,2 Because the epidemiology of THP is such as conjunctival icterus, dermal jaundice, pale

not well understood and clear guidelines for evaluating stools, dark urine, pruritus, easy bruising or bleeding,

this problem are lacking, THP is usually diagnosed by limping, bone pain, or weight loss were not encoun-

excluding other diseases, which, may require exten- tered during or after this acute illness. Past medical,

sive biochemical and radiographic studies, all adding family and social histories were negative. On physi-

significant costs for the health care system. Herein, cal examination, she was a well nourished female

with the help of an illustrative example, we suggest with normal vital signs and both weight and height

a clinical algorithm outlining minimum tests for the between the 25–50th percentile. There were no dys-

diagnosis and management of a patient with THP morphic features, skeletal abnormalities, bony ten-

avoiding unnecessary investigations and referral to a derness, conjunctivalicterus, hepatosplenomegaly or

specialist. Although the discussion is relevant to pedi- any other stigmata of chronic liver or bone disease.

atric gastroenterologists, the main objective of the A month after the first determination, AP level had

paper is to help the primary care physician determine declined to 830 U/L. After the careful history, exami-

when a “wait and see” approach is optimal, and when nation and review of the above studies, the diagnosis

a referral to a specialist becomes necessary in the set- of THP was made and no further investigations were

ting of a child with elevated AP. deemed necessary. As expected AP level normalized

at four months (243 U/L; normal less than 282).

Illustrative Case

A 27-month old previously healthy Caucasian female Discussion

presented to the Pediatric Hepatobiliary Clinic for Due to the typical age, normal physical examination,

evaluation and management of elevated serum AP and elevation of both liver and bone-specific AP-isoen-

concentration. Two months before her gastrointesti- zymes the diagnosis of THP was made according to the

nal clinic visit, she had vomiting and diarrhea consis- commonly used criteria.3 Because no tests were done

tent with acute viral gastroenteritis which gradually at the onset of gastroenteritis coupled with relatively

resolved spontaneously without any specific therapy short half life of AP (seven days) we were unable to

or sequelae. Although most of the symptoms of acute establish a definitive link between gastroenteritis and

16 Clinical Medicine Insights: Pediatrics 2011:5

Transient hyperphosphatasemia

elevated AP levels. Interestingly, apart from well than the normal adult values. Secondly, although the

known elevation of liver and bone-specific AP-isoen- prevalence and risk factors remain ill defined, THP

zymes, a rise in intestinal AP-isoenzyme has also is relatively common condition in children younger

been documented albeit in a minority of patients with than five years of age. For example, up to 1.5% of

THP.4 However, because intestinal isoenzymefraction healthy Finnish infants and toddlers were reported to

was not assessed, we can only postulate that elevation have THP in a prospective study.6 Finally, where as

of total AP activity was partly due to intestinal isoen- the biochemical mechanisms of pathologic elevations

zyme. Indeed acute gastroenteritis has been suggested of AP can be delineated in most cases, the underly-

to be a risk factor for THP.5 The family was reassured ing patho-physiological mechanisms of THP remain

and further investigations were not carried out. Nor- elusive: therefore, even with extensive investigations,

malization of AP in four months supported our initial establishment of the underlying etiology is generally

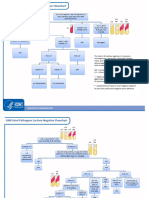

impression of THP. We suggest an easy to use clini- not possible. Therefore, when the criteria utilized in

cal algorithm (Fig. 1) for primary care physicians as this and earlier reports are met, additional investiga-

a guide to determine when further work-up or referral tions are neither evidence based nor necessary, given

to a gastroenterologist can be deferred. the spontaneous and uneventful resolution of this

AP is present in many tissues throughout the body: condition in a few months.7 In the primary care set-

therefore, serum AP level represents the collective ting, the emphasis should be on clinical assessment

activity of a group of enzymes which catalyze the supplemented by limited laboratory investigations as

hydrolysis of organic phosphate esters. Most of the outlined in the algorithm (Fig. 1).

circulating AP is, however, derived from liver; bone; The history should focus on symptoms of liver,

intestinal tract; and kidneys. When investigating intestinal, renal, and bone diseases with careful evalu-

the cause of abnormal values of AP, several physi- ations of any drug administrations─prescribed as well

ological factors pertinent to infants and children are as over the counter. Specific inquiries should be made

important to understand. First, the reference AP levels about the use of anticonvulsants such as Phenobarbital,

gradually rise during the first decade and the peak Phenytoin or Carbamazepine.8–10 Symptoms of

values (in early teens) are three to four times higher anorexia, fatigue, fever, and weight loss should prompt

Elevated AP

History and physical examination

HFP, GGT or 5´ NT, AP-isoenzymes

Ca/P, PTH, Vitamin-D, BUN and creatinine

L-AP elevated Both L-AP and B-AP elevated

B-AP elevated

S/S of liver disease Age < 5 years

Normal GGT

Raised GGT Normal H & P

S/S of bone disease

Abnormal HFP Normal HFP and GGT

Refer to Work up for bone Suspect THF

gastro enterology diseases

Repeat AP in 4

months

Figure 1. Algorithm for the assessment and management of a child with isolated elevated serum alkaline phosphatase in the primary care setting.

Abbreviations: GGT, γ-glutamyltranspeptidase; L-AP, liver-specific alkaline phosphatase; B-AP, bone-specific alkaline phosphatase; 5′NT, 5′-nucleotidase;

HFP, hepatic function panel; THP, transient hyper-alkaline phosphatemia; Ca/P, calcium/phosphorus; PTH, parathyroid hormone.

Clinical Medicine Insights: Pediatrics 2011:5 17

Otero et al

further evaluation of possible underlying pathological Publication of this article was funded in part by the

conditions. For example, specific enquiries should be University of Florida Open-Access Publishing Fund.

made about risk factors for rickets such as prematurity,

exposure to sunlight, duration of breast feeding and References

whether or not the child has been consuming adequate 1. Huh SY, Feldman HA, Cox JE, Gordon CM. Prevalence of transient

hyperphosphatasemia among healthy infants and toddlers. Pediatrics. 2009;

quantities of vitamin-D fortified formula. Symptoms 124:703–9.

indicative of hepatobiliary disease such as dark colored 2. Holt PA, Steel AE, Armstrong AM. Transient hyperphosphatasaemia of

infancy following rotavirus infection. J Infect. 1984;9:283–5.

urine, pruritis, bruising and steatorrhea should be care- 3. Kraut JR, Metrick M, Maxwell NR, Kaplan MM. Isoenzyme studies in

fully elicited. A thorough physical examination should transient hyperphosphatasemia of infancy. Ten new cases and a review of the

literature. Am J Dis Child. 1985;139:736–40.

be completed─searching for signs of underlying hepa- 4. Behulova D, Bzduch V, Holesova D, Vasilenkova A, Ponec J. Transient

tobiliary dysfunction such as icterus, clubbing, hepato- hyperphosphatasemia of infancy and childhood: study of 194 cases. Clin

splenomegaly, ascites, palmar erythema, and spider Chem. 2000;46:1868–9.

5. Stein P, Rosalki SB, Foo AY, Hjelm M. Transient hyperphosphatasemia of

telangiectasia. Similarly signs of rickets (swelling at infancy and early childhood: clinical and biochemical features of 21 cases

the costo-chondral junction and long bones) should and literature review. Clin Chem. 1987;33:313–8.

6. Asanti R, Hultin H, Visakorpi JK. Serum alkaline, phosphatase in healthy

be carefully looked for. Apart from the hepatic func- infants. Occurrence of abnormally high values without known cause. Ann

tion panel, laboratory testing should include gamma- Paediatr Fenn. 1966;12:139–42.

glutamyltranspeptidaseor 5’-nucleotidase to determine 7. Kutilek S, Bayer M, Markova D. Prospective follow-up of children with

transient hyperphosphatasemia. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 1997;36:491–2.

if AP elevation is the result of underlying hepatobil- 8. Morijiri Y, Sato T. Factors causing rickets in institutionalised handicapped children

iary disease. Likewise, calcium, phosphorus, parathy- on anticonvulsant therapy. Archives of Disease in Childhood. 1981; 56:446–9.

9. Valmadrid C, Voorhees C, Litt B, Schneyer CR. Practice Patterns of Neurol-

roid hormone, vitamin D level, blood urea nitrogen ogists Regarding Bone and Mineral Effects of Antiepileptic Drug Therapy.

and creatinine should be assessed. If these tests yield Archives of Neurology. 2001;58:1369–74.

normal results, then further evaluation can be withheld 10. Nicolaidou P, Georgouli H, Kotsalis H, Matsinos Y, Papadopoulou A,

Fretzayas A, et al. Effects of Anticonvulsant Therapy on Vitamin D Status

for three to four months, by which time AP concen- in Children: Prospective Monitoring Study. Journal of Child Neurology.

tration should be repeated. Given the benign nature of 2006;21:205–210.

this entity, rechecking AP earlier than four months is

unnecessary. Although the suggested four month inter- Publish with Libertas Academica and

val for the follow up determination of AP is arbitrary, every scientist working in your field can

we recommend waiting this long to be consistent with read your article

widely accepted definition of THP.3 In conclusion,

“I would like to say that this is the most author-friendly

THPis a relatively common condition among healthy editing process I have experienced in over 150

infants and toddlers which resolves without any publications. Thank you most sincerely.”

intervention. Extensive work up or referral to a special-

ist can be avoided by following an easy use algorithm “The communication between your staff and me has

with emphasis on history and physical examination. It been terrific. Whenever progress is made with the

is understood that based on the unique local expertise manuscript, I receive notice. Quite honestly, I’ve

never had such complete communication with a

and access to follow up care, primary care physicians journal.”

can utilize this algorithm to custom design the care of

an individual patient. “LA is different, and hopefully represents a kind of

scientific publication machinery that removes the

Disclosure hurdles from free flow of scientific thought.”

This manuscript has been read and approved by all

Your paper will be:

authors. This paper is unique and is not under consid-

• Available to your entire community

eration by any other publication and has not been pub-

free of charge

lished elsewhere. The authors and peer reviewers of this • Fairly and quickly peer reviewed

paper report no conflicts of interest. The authors confirm • Yours! You retain copyright

that they have permission to reproduce any copyrighted

material. This work was exempt from approval by the http://www.la-press.com

Institutional Review Boards of the University of Florida.

18 Clinical Medicine Insights: Pediatrics 2011:5

You might also like

- Complementary and Alternative Medical Lab Testing Part 9: GynecologyFrom EverandComplementary and Alternative Medical Lab Testing Part 9: GynecologyNo ratings yet

- Acute Liver Failure in Children 2008Document15 pagesAcute Liver Failure in Children 2008nevermore11No ratings yet

- Typhoid Fever With Acute Pancreatitis in A Five-Year-Old ChildDocument2 pagesTyphoid Fever With Acute Pancreatitis in A Five-Year-Old Childnurma alkindiNo ratings yet

- Congenital Hyperinsulinism: A Practical Guide to Diagnosis and ManagementFrom EverandCongenital Hyperinsulinism: A Practical Guide to Diagnosis and ManagementDiva D. De León-CrutchlowNo ratings yet

- Thai Infant Case Report of Classical GalactosemiaDocument6 pagesThai Infant Case Report of Classical GalactosemiaReuben JosephNo ratings yet

- AASLD Position Paper The Management of Acute Liver FailureDocument19 pagesAASLD Position Paper The Management of Acute Liver FailurePhan Nguyễn Đại NghĩaNo ratings yet

- Acute Liver Failure in Children Management - UpToDateDocument20 pagesAcute Liver Failure in Children Management - UpToDateZeliha TürksavulNo ratings yet

- Squires 2013Document8 pagesSquires 2013Thinh NguyenNo ratings yet

- Neonatal Vomiting Due to Pyloric Stenosis and Congenital Nephrotic SyndromeDocument5 pagesNeonatal Vomiting Due to Pyloric Stenosis and Congenital Nephrotic SyndromeHanny RusliNo ratings yet

- Causes and evaluation of acute liver failure in childrenDocument31 pagesCauses and evaluation of acute liver failure in childrenBhargav YagnikNo ratings yet

- 1 Predict NeoDocument5 pages1 Predict NeoGary Carhuamaca LopezNo ratings yet

- Clinical Case Study: Questions To ConsiderDocument3 pagesClinical Case Study: Questions To Considerالشهيد محمدNo ratings yet

- Early Feeding in Acute Pancreatitis in Children A Randomized Controlled TrialDocument9 pagesEarly Feeding in Acute Pancreatitis in Children A Randomized Controlled TrialvalenciaNo ratings yet

- Lancet Article PDFDocument5 pagesLancet Article PDFBrandy GarciaNo ratings yet

- Materials and MethodsDocument3 pagesMaterials and MethodssurtitejoNo ratings yet

- Guideline For The Evaluation of Cholestatic.23Document15 pagesGuideline For The Evaluation of Cholestatic.23Yuliawati HarunaNo ratings yet

- American Academy of Pediatrics Metabolic Disorders 2014 Practice TestDocument43 pagesAmerican Academy of Pediatrics Metabolic Disorders 2014 Practice TestPrabu KumarNo ratings yet

- Jurnal AKIDocument7 pagesJurnal AKIAnonymous Vz9teLNo ratings yet

- Pattern of Elevated Serum Alkaline Phosphatase (ALP) Levels in Hospitalized PatientsDocument7 pagesPattern of Elevated Serum Alkaline Phosphatase (ALP) Levels in Hospitalized PatientsDannyNo ratings yet

- Acute Fatty Liver of Pregnancy Recovery TimesDocument7 pagesAcute Fatty Liver of Pregnancy Recovery TimesJulio Alejandro PeñaNo ratings yet

- Dog - US Evaluation of Severity of Pancreatitis - Clinician's BriefDocument3 pagesDog - US Evaluation of Severity of Pancreatitis - Clinician's BriefvetthamilNo ratings yet

- 004 LabsDiagnosticsManualDocument64 pages004 LabsDiagnosticsManualRaju Niraula100% (1)

- Gastritis AutoinmunrDocument15 pagesGastritis Autoinmunrfiolit13No ratings yet

- Maple Syrup Urine Disease Case StudyDocument5 pagesMaple Syrup Urine Disease Case StudyMaria ClaraNo ratings yet

- Early - and Late-Onset Preeclampsia A ComprehensiveDocument10 pagesEarly - and Late-Onset Preeclampsia A ComprehensiveEriekafebriayana RNo ratings yet

- A Case Report On Intrahepatic Cholestasis of PregnancyDocument4 pagesA Case Report On Intrahepatic Cholestasis of PregnancyEditor IJTSRDNo ratings yet

- When Is It OK to Sedate a Child Who Just AteDocument7 pagesWhen Is It OK to Sedate a Child Who Just AteNADIA VICUÑANo ratings yet

- Acute Liver Failure in Children CoolDocument9 pagesAcute Liver Failure in Children CoolIvan Licon100% (1)

- Conjugated Hyperbilirubinemia in The Neonatal Intensive Care UnitDocument9 pagesConjugated Hyperbilirubinemia in The Neonatal Intensive Care UnitIvan HoNo ratings yet

- International Reports: Incidence of Hepatotoxicity Due To Antitubercular Medicines and Assessment of Risk FactorsDocument6 pagesInternational Reports: Incidence of Hepatotoxicity Due To Antitubercular Medicines and Assessment of Risk FactorsWelki VernandoNo ratings yet

- Constipation: Beyond The Old ParadigmsDocument18 pagesConstipation: Beyond The Old ParadigmsJhonatan Efraín López CarbajalNo ratings yet

- 2014 Guideline For The Evaluation of Cholestatic Jaundice in InfantsDocument61 pages2014 Guideline For The Evaluation of Cholestatic Jaundice in InfantsHenry BarberenaNo ratings yet

- Reviews Advances in Pediatric Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver DiseaseDocument12 pagesReviews Advances in Pediatric Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver DiseasehansenpanjaitanNo ratings yet

- The Philippine Thyroid Disorder Prevalence StudyDocument7 pagesThe Philippine Thyroid Disorder Prevalence StudyCharmaine SolimanNo ratings yet

- Electronicfetal Monitoring:Past, Present, Andfuture: Molly J. Stout,, Alison G. CahillDocument16 pagesElectronicfetal Monitoring:Past, Present, Andfuture: Molly J. Stout,, Alison G. CahillGinecólogo Oncólogo Danilo Baltazar ChaconNo ratings yet

- Gastroesophageal Reflux in Children An Updated ReviewDocument12 pagesGastroesophageal Reflux in Children An Updated ReviewAndhika D100% (1)

- 1543-2165-134 6 815 PDFDocument11 pages1543-2165-134 6 815 PDFmmigod666No ratings yet

- Medical Management of Acute Liver FailureDocument19 pagesMedical Management of Acute Liver Failure4rqph7xnf2No ratings yet

- 84mother ArticleDocument7 pages84mother ArticleGAYATHIRINo ratings yet

- RM - Article 1Document3 pagesRM - Article 1SIVARAM E MBA (HOSPITAL & HEALTH SYSTEMS MANAGEMENT)No ratings yet

- Chronic Hepatitis CAHDocument6 pagesChronic Hepatitis CAHHeny HenthonkNo ratings yet

- The Pubertal Presentation of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome PCOS 2002 Fertility and SterilityDocument1 pageThe Pubertal Presentation of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome PCOS 2002 Fertility and SterilityfujimeisterNo ratings yet

- Will Hyperbilirubinemic Neonates Ever Benefit From.28 PDFDocument4 pagesWill Hyperbilirubinemic Neonates Ever Benefit From.28 PDFmagreaNo ratings yet

- Omega-3 Fatty Acids Therapy in Children With Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: A Randomized Controlled TrialDocument9 pagesOmega-3 Fatty Acids Therapy in Children With Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: A Randomized Controlled TrialSardono WidinugrohoNo ratings yet

- Relationship of Serum Uric Acid Level With Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease and Its in Ammation Progression in Non-Obese AdultsDocument9 pagesRelationship of Serum Uric Acid Level With Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease and Its in Ammation Progression in Non-Obese AdultssyifaNo ratings yet

- Acute Liver Failure in Cuban ChildrenDocument7 pagesAcute Liver Failure in Cuban Childrennevermore11No ratings yet

- KolestasisDocument10 pagesKolestasisNur Ainatun NadrahNo ratings yet

- 10 6133@apjcn 2015 24 1 07Document9 pages10 6133@apjcn 2015 24 1 07Lilik FitrianaNo ratings yet

- Update On The Evaluation and Management of Functional DyspepsiaDocument7 pagesUpdate On The Evaluation and Management of Functional DyspepsiaDenuna EnjanaNo ratings yet

- Acute PancreatitisDocument9 pagesAcute PancreatitisJayari Cendana PutraNo ratings yet

- Bouch Lario To U 2014 GGGDocument7 pagesBouch Lario To U 2014 GGGJack ButcherNo ratings yet

- Nelson2013 Ajog PDFDocument7 pagesNelson2013 Ajog PDFsaryindrianyNo ratings yet

- Aplastic Anemia Case Study FINALDocument53 pagesAplastic Anemia Case Study FINALMatthew Rich Laguitao Cortes100% (6)

- Diagnostico Gastropatias CronicasDocument18 pagesDiagnostico Gastropatias CronicasmariaNo ratings yet

- RajaniDocument8 pagesRajaniArnette Castro de GuzmanNo ratings yet

- Management of Acute Gastroenteritis in Children: Pathophysiology in The UKDocument6 pagesManagement of Acute Gastroenteritis in Children: Pathophysiology in The UKMarnia SulfianaNo ratings yet

- Jurnal BreastDocument4 pagesJurnal BreastCarolin WijayaNo ratings yet

- Yield of laboratory testing in pediatric ketogenic diet patientsDocument19 pagesYield of laboratory testing in pediatric ketogenic diet patientsMarcin CiekalskiNo ratings yet

- Case Hernia2Document19 pagesCase Hernia2ejkohNo ratings yet

- Mother's HatredDocument835 pagesMother's HatredXoliswa Nakedi0% (1)

- Vale FormDocument1 pageVale FormRANDY BAOGBOGNo ratings yet

- Tle - He-Dressmaking: Seven / Eight ThreeDocument4 pagesTle - He-Dressmaking: Seven / Eight Threehyndo plasamNo ratings yet

- Pool Paint Safety Data SheetDocument9 pagesPool Paint Safety Data SheetNicholson Vhenz UyNo ratings yet

- Effects of A Capacitive-Resistive Electric Transfer Therapy OnDocument8 pagesEffects of A Capacitive-Resistive Electric Transfer Therapy OnAnna Lygia LunardiNo ratings yet

- MSDS DDDocument2 pagesMSDS DDBaher SaidNo ratings yet

- AL CIERRE DE Julio Del 2021: Barra COD AlfabetaDocument2 pagesAL CIERRE DE Julio Del 2021: Barra COD AlfabetaBrian Javier GomezNo ratings yet

- Vague X The Skateboard Physiotherapist - Isolation GuideDocument12 pagesVague X The Skateboard Physiotherapist - Isolation GuideKiko Lorman AlvarezNo ratings yet

- (24513105 - BANTAO Journal) Oral and Salivary Changes in Patients With Chronic Kidney DiseaseDocument6 pages(24513105 - BANTAO Journal) Oral and Salivary Changes in Patients With Chronic Kidney DiseaseVera Radojkova NikolovskaNo ratings yet

- Appointment - CR22 Crane Operator - 2021Document2 pagesAppointment - CR22 Crane Operator - 2021carlthiahNo ratings yet

- Bionic Final PDFDocument4 pagesBionic Final PDFJasmine RaoNo ratings yet

- CrossFit®-Injury Prevalence and Main Risk Factors (Curiosidade)Document5 pagesCrossFit®-Injury Prevalence and Main Risk Factors (Curiosidade)TUTOR PAULO EDUARDO REDKVANo ratings yet

- MCN ReviewerDocument3 pagesMCN ReviewerJunghoon YangParkNo ratings yet

- Sub-Adventitial Divestment Technique For Resecting Artery-Involved Pancreatic Cancer: A Retrospective Cohort StudyDocument11 pagesSub-Adventitial Divestment Technique For Resecting Artery-Involved Pancreatic Cancer: A Retrospective Cohort StudyMatias Jurado ChaconNo ratings yet

- SR No. District Name Address Contact NoDocument3 pagesSR No. District Name Address Contact Nochirag sabhayaNo ratings yet

- The Application of CAD CAM Technology in DentistryDocument13 pagesThe Application of CAD CAM Technology in DentistryMihaela Vasiliu0% (1)

- Broselow Pediatric Emergency TapeDocument13 pagesBroselow Pediatric Emergency TapePaulo KaleNo ratings yet

- Concept Map - SepsisDocument9 pagesConcept Map - SepsismarkyabresNo ratings yet

- India 2030 PDFDocument188 pagesIndia 2030 PDFGray HouserNo ratings yet

- CS14396 XimenaParra Advanced Management of WHS A2 MyapchubDocument6 pagesCS14396 XimenaParra Advanced Management of WHS A2 MyapchubXimena ParraNo ratings yet

- GTLMH student evaluationDocument2 pagesGTLMH student evaluationabcalagoNo ratings yet

- Burn - Daily Physical AssessmentDocument8 pagesBurn - Daily Physical AssessmentkrishcelNo ratings yet

- Clinical Reasoning Evaluation Simulation Tool (CREST)Document3 pagesClinical Reasoning Evaluation Simulation Tool (CREST)BenToNo ratings yet

- Rts Medicines 7778-1Document79 pagesRts Medicines 7778-1sam yadavNo ratings yet

- CareGroup Case Study QuestionsDocument1 pageCareGroup Case Study QuestionsEnrica Melissa PanjaitanNo ratings yet

- GNR Stool Pathogens Lactose Negative FlowchartDocument2 pagesGNR Stool Pathogens Lactose Negative FlowchartKeithNo ratings yet

- Solicitud de Material (Actualizado Al 01 de Diciembre 2020) Teleredes 1Document151 pagesSolicitud de Material (Actualizado Al 01 de Diciembre 2020) Teleredes 1Jjdfyiseth AmayajjdfNo ratings yet

- Ik Gujral Punjab Technical University Jalandhar, Kapurthala: Sess Sem Sub Code Sub Title Course/BranchDocument178 pagesIk Gujral Punjab Technical University Jalandhar, Kapurthala: Sess Sem Sub Code Sub Title Course/BranchMohit KaundalNo ratings yet

- Adherence To Nucleos (T) Ide Analogue PDFDocument8 pagesAdherence To Nucleos (T) Ide Analogue PDFVirgo WNo ratings yet

- TOS g78 Crop ProductionDocument1 pageTOS g78 Crop ProductionRommel Lim BasalloteNo ratings yet

- LIT: Life Ignition Tools: Use Nature's Playbook to Energize Your Brain, Spark Ideas, and Ignite ActionFrom EverandLIT: Life Ignition Tools: Use Nature's Playbook to Energize Your Brain, Spark Ideas, and Ignite ActionRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (402)

- The Age of Magical Overthinking: Notes on Modern IrrationalityFrom EverandThe Age of Magical Overthinking: Notes on Modern IrrationalityRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (15)

- Think This, Not That: 12 Mindshifts to Breakthrough Limiting Beliefs and Become Who You Were Born to BeFrom EverandThink This, Not That: 12 Mindshifts to Breakthrough Limiting Beliefs and Become Who You Were Born to BeNo ratings yet

- Raising Mentally Strong Kids: How to Combine the Power of Neuroscience with Love and Logic to Grow Confident, Kind, Responsible, and Resilient Children and Young AdultsFrom EverandRaising Mentally Strong Kids: How to Combine the Power of Neuroscience with Love and Logic to Grow Confident, Kind, Responsible, and Resilient Children and Young AdultsRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- The Obesity Code: Unlocking the Secrets of Weight LossFrom EverandThe Obesity Code: Unlocking the Secrets of Weight LossRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (4)

- By the Time You Read This: The Space between Cheslie's Smile and Mental Illness—Her Story in Her Own WordsFrom EverandBy the Time You Read This: The Space between Cheslie's Smile and Mental Illness—Her Story in Her Own WordsNo ratings yet

- Raising Good Humans: A Mindful Guide to Breaking the Cycle of Reactive Parenting and Raising Kind, Confident KidsFrom EverandRaising Good Humans: A Mindful Guide to Breaking the Cycle of Reactive Parenting and Raising Kind, Confident KidsRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (169)

- Why We Die: The New Science of Aging and the Quest for ImmortalityFrom EverandWhy We Die: The New Science of Aging and the Quest for ImmortalityRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (3)

- Summary: The Psychology of Money: Timeless Lessons on Wealth, Greed, and Happiness by Morgan Housel: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedFrom EverandSummary: The Psychology of Money: Timeless Lessons on Wealth, Greed, and Happiness by Morgan Housel: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (78)

- The Happiness Trap: How to Stop Struggling and Start LivingFrom EverandThe Happiness Trap: How to Stop Struggling and Start LivingRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- The Ritual Effect: From Habit to Ritual, Harness the Surprising Power of Everyday ActionsFrom EverandThe Ritual Effect: From Habit to Ritual, Harness the Surprising Power of Everyday ActionsRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (3)

- Summary: Outlive: The Science and Art of Longevity by Peter Attia MD, With Bill Gifford: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisFrom EverandSummary: Outlive: The Science and Art of Longevity by Peter Attia MD, With Bill Gifford: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (42)

- Dark Psychology & Manipulation: Discover How To Analyze People and Master Human Behaviour Using Emotional Influence Techniques, Body Language Secrets, Covert NLP, Speed Reading, and Hypnosis.From EverandDark Psychology & Manipulation: Discover How To Analyze People and Master Human Behaviour Using Emotional Influence Techniques, Body Language Secrets, Covert NLP, Speed Reading, and Hypnosis.Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (110)

- Techniques Exercises And Tricks For Memory ImprovementFrom EverandTechniques Exercises And Tricks For Memory ImprovementRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (40)

- The Ultimate Guide To Memory Improvement TechniquesFrom EverandThe Ultimate Guide To Memory Improvement TechniquesRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (34)

- Roxane Gay & Everand Originals: My Year of Psychedelics: Lessons on Better LivingFrom EverandRoxane Gay & Everand Originals: My Year of Psychedelics: Lessons on Better LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (33)

- Outlive: The Science and Art of Longevity by Peter Attia: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisFrom EverandOutlive: The Science and Art of Longevity by Peter Attia: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Summary: It Didn't Start with You: How Inherited Family Trauma Shapes Who We Are and How to End the Cycle By Mark Wolynn: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisFrom EverandSummary: It Didn't Start with You: How Inherited Family Trauma Shapes Who We Are and How to End the Cycle By Mark Wolynn: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (3)

- Cult, A Love Story: Ten Years Inside a Canadian Cult and the Subsequent Long Road of RecoveryFrom EverandCult, A Love Story: Ten Years Inside a Canadian Cult and the Subsequent Long Road of RecoveryRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (44)

- The Body Keeps the Score by Bessel Van der Kolk, M.D. - Book Summary: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of TraumaFrom EverandThe Body Keeps the Score by Bessel Van der Kolk, M.D. - Book Summary: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of TraumaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Tennis Partner: A Doctor's Story of Friendship and LossFrom EverandThe Tennis Partner: A Doctor's Story of Friendship and LossRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (4)

- Mindset by Carol S. Dweck - Book Summary: The New Psychology of SuccessFrom EverandMindset by Carol S. Dweck - Book Summary: The New Psychology of SuccessRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (328)

- Roxane Gay & Everand Originals: My Year of Psychedelics: Lessons on Better LivingFrom EverandRoxane Gay & Everand Originals: My Year of Psychedelics: Lessons on Better LivingRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (5)