Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The House of The Dead

Uploaded by

lilygodsteinOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

The House of The Dead

Uploaded by

lilygodsteinCopyright:

Available Formats

The House of the Dead

“If you only read the books that everyone else is reading, you can only think what everyone

else is thinking.”

― Haruki Murakami, Norwegian Wood

A book that merely lets us take pleasure in it is not an exemplification of a good book at all. An

excellent book keeps us enamored from beginning to end, as well as persists us in contemplating

critically about the author’s point of view, principles, and impressions that lie beneath the multitude

of words the book retains. And one such work that has enthralled many well-known authors and

philosophers is Fyodor Dostoyevsky’s “The House of the Dead,” with its bleak yet morbidly

fascinating descriptive prose.

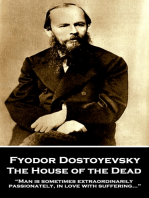

Fyodor Mikhailovich Dostoyevsky was a Russian

novelist, short story writer, essayist, and journalist.

Throughout his life, he authored a great deal of

literature and journalism, but his books' dramatic

structure and psychological nuance have helped him

become most well-known. His debut book, "Poor

Folk," brought him immediate acclaim and allowed

him to join the Saint Petersburg literary community

However, he was imprisoned in 1849 for belonging

to The Petrashevsky Circle, a radical intellectual

discussion club that studied outlawed literature that

was critical of Tsarist Russia. After being

imprisoned for 4 years in a Siberian prison camp,

followed by 6 years of compulsory military service

in exile, he was released and went on to compose

"Notes from the House of the Dead" in sections

between 1860 and 1862.

“The House of the Dead” is mainly Dostoyevsky’s

prison experience in the guise of a convict named

Alexander Petrovich Goryanchikov, imprisoned ten years for murdering his own wife. But the

book is more than just a straightforward semi-autobiography. The book is a peculiar kind of writing

that seamlessly flips between several genres, including factual, philosophical, autobiographical,

documentary, novel, and social tract. The many genres combine to create a striking image of the

"peculiar world" of the prison, as Dostoyevsky refers to it.

There are more hues and facades to life than just black and white, like two sides of a coin. It can

appear pure red, blue, or lavender at different times. And like an octagonal shape, it comprises

multiple planes. And in this book, Dostoyevsky expresses this very notion. Despite the fact that

the prison was populated with individuals who had committed heinous crimes, some goodness

remained in them despite their offense and sentence. Being guilty of a crime and not feeling guilty

regarding it does not render one either good or bad. It all depends on the viewpoint and perspective.

Someone can be harsh or nice at times, impolite or courteous, or even a criminal or saint. Although

the jail is harsh, its inmates are not necessarily vicious. In the midst of death, Goryanchikov found

hope and life in gestures of compassion and love. Convicts extending assistance to one another,

prisoners fostering animals, widows offering charity to the prisoners, doctors providing kindness

to the inmates—these insignificant acts do not mitigate prison’s darkness, but they permit the

human soul to survive with some semblance of hope.

Of course, there are lovely philosophical musings – a signature trait of Dostoyevsky’s works. In

addition to other complex subjects, the narrator muses about the nature of freedom, the significance

of hope, the disparity in penalties for the same offense, the discrepancy between appearance and

reality, and free will. Through Goryanchikov, Dostoyevsky offers an account of prison life that is

profoundly dehumanizing. He believes in humanity, in treating convicts as they are – human

beings. As he said in the book,

“Every man, whoever he may be and however humiliated, still requires, even if instinctively, even

if unconsciously, respect for his human dignity. The prisoner himself knows that he is a prisoner,

an outcast, and he knows his place before his superior; but no brands, no fetters will make him

forget that he is a human being. And since he is in fact a human being, it follows that he must be

treated as a human being.”

The novel makes readers consider Goriyanchikov's query: How are our neighbors' souls being

shaped by prisons? Furthermore, who is making notes? The book portrayed a vivid picture of a

world in which convicts are tormented by boredom, loneliness, insanity, despair, and a lack of

freedom—and all of this while being shackled. Yet, the book is no mere catalogue of prison’s

hardships.

“Here was the house of the living dead, a life like none other upon earth.”

“The House of the Dead” is a powerful novel of redemption, exploring one man’s spiritual and

moral death and the miracle of his gradual reawakening. The book isn’t an easy read; it is slow-

paced and sometimes monotonous. Moreover, it slightly deviated from Dostoyevsky’s famous

format. In comparison to Dostoyevsky’s other books, “The House of the Dead” is simple and

lacks dramatics. But the book lives up to its title. Despite having an ending, the book leaves the

reader ambiguous, thinking about the morbid yet fascinating nature of life—inside prison or

outside prison. Definitely a Dostoyevsky!

Tasfia Tabassum

Department of English

48th batch

BAERF48223028

You might also like

- European Lit Assignment 1Document9 pagesEuropean Lit Assignment 1George KengaNo ratings yet

- DostoevskyDocument2 pagesDostoevskyapi-276757735No ratings yet

- C&P Complete Final DraftDocument16 pagesC&P Complete Final DraftMason HarperNo ratings yet

- Assignment On Crime and PunishmentDocument21 pagesAssignment On Crime and Punishmentmaryam.fatimalkoNo ratings yet

- 17578-Texto Del Artículo-50565-1-10-20201215Document9 pages17578-Texto Del Artículo-50565-1-10-20201215Nenad VujosevicNo ratings yet

- Notes From Underground - Dostoevsky SDocument7 pagesNotes From Underground - Dostoevsky SratiguanaNo ratings yet

- The Ridiculous Jew: The Exploitation and Transformation of a Stereotype in Gogol, Turgenev, and DostoevskyFrom EverandThe Ridiculous Jew: The Exploitation and Transformation of a Stereotype in Gogol, Turgenev, and DostoevskyNo ratings yet

- The House of the Dead: “Man is sometimes extraordinarily, passionately, in love with suffering...”From EverandThe House of the Dead: “Man is sometimes extraordinarily, passionately, in love with suffering...”No ratings yet

- Module II Essay2Document8 pagesModule II Essay2Rosie MuraviowNo ratings yet

- Haunted by Christ: Modern Writers and the Struggle for FaithFrom EverandHaunted by Christ: Modern Writers and the Struggle for FaithRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (2)

- Book Analysis: Crime and PunishmentDocument6 pagesBook Analysis: Crime and PunishmentComputer Guru100% (5)

- Gallagher, J.-Dostoevsky As PhilosopherDocument16 pagesGallagher, J.-Dostoevsky As PhilosopherDaniel Augusto García PorrasNo ratings yet

- The Legacy of Fyodor DostoyevksyDocument6 pagesThe Legacy of Fyodor DostoyevksyJesus MolinaNo ratings yet

- III. Russian Literature: Fathers and Sons (1862), in Which Is Portrayed The Conflict BetweenDocument33 pagesIII. Russian Literature: Fathers and Sons (1862), in Which Is Portrayed The Conflict Betweenvirgomeenu100% (2)

- Dostoevsky As Philosopher - Lecture by Prof. Jay GallagherDocument17 pagesDostoevsky As Philosopher - Lecture by Prof. Jay Gallaghergnomgnot7671No ratings yet

- The Stranger Within - Dostoevsky's UndergroundDocument13 pagesThe Stranger Within - Dostoevsky's Undergroundadrian duarte diazNo ratings yet

- Nabokov CNPDocument3 pagesNabokov CNPنسيم نسيمانيNo ratings yet

- Fyodor Dostoevsky - Quotes Collection: Biography, Achievements And Life LessonsFrom EverandFyodor Dostoevsky - Quotes Collection: Biography, Achievements And Life LessonsNo ratings yet

- DostoevskyDocument116 pagesDostoevskycalu balanNo ratings yet

- Crime and Punishment-Fyodor DostoevskyDocument353 pagesCrime and Punishment-Fyodor DostoevskysubstareNo ratings yet

- Fyodor Dostoevsk1Document6 pagesFyodor Dostoevsk1nayabNo ratings yet

- The Stranger Within. Dostoevsky's UndergroundDocument14 pagesThe Stranger Within. Dostoevsky's UndergroundIleanaNo ratings yet

- Nikolai Gogol: 4 books in English translationFrom EverandNikolai Gogol: 4 books in English translationRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1524)

- Dostoyevsky Crime and PunishmentDocument452 pagesDostoyevsky Crime and PunishmentEl SheikhNo ratings yet

- Giving the Devil His Due: Demonic Authority in the Fiction of Flannery O’Connor and Fyodor DostoevskyFrom EverandGiving the Devil His Due: Demonic Authority in the Fiction of Flannery O’Connor and Fyodor DostoevskyNo ratings yet

- Christian View of Crime and PunishmentDocument9 pagesChristian View of Crime and PunishmentMi GasparNo ratings yet

- Essential Novelists - Nikolai Gogol: the foundations of Russian realismFrom EverandEssential Novelists - Nikolai Gogol: the foundations of Russian realismNo ratings yet

- Bardach & Gleeson - Surviving Freedom After The Gulag (2003)Document295 pagesBardach & Gleeson - Surviving Freedom After The Gulag (2003)Peter Lenghart LackovicNo ratings yet

- Fyodor Dost Eve SkyDocument3 pagesFyodor Dost Eve SkyangelaNo ratings yet

- Dostoevsky, F - Crime and Punishment (Random, 1992)Document329 pagesDostoevsky, F - Crime and Punishment (Random, 1992)Kamijo Yoitsu100% (1)

- The Master and Margarita by Mikhail Bulgakov (Book Analysis): Detailed Summary, Analysis and Reading GuideFrom EverandThe Master and Margarita by Mikhail Bulgakov (Book Analysis): Detailed Summary, Analysis and Reading GuideNo ratings yet

- Crime and PunishmentDocument12 pagesCrime and Punishmentsobia faryadaliNo ratings yet

- Reading List For Books Behind Bars Course Described in Slavfile Summer 2013 Required ReadingsDocument4 pagesReading List For Books Behind Bars Course Described in Slavfile Summer 2013 Required ReadingsGalina RaffNo ratings yet

- The House of the Dead and Poor Folk (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)From EverandThe House of the Dead and Poor Folk (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)No ratings yet

- Modern Movements in European Philosophy Final ProjectDocument12 pagesModern Movements in European Philosophy Final ProjectAmna AhadNo ratings yet

- Peculiarities of The Intellectual NovelDocument3 pagesPeculiarities of The Intellectual NovelresearchparksNo ratings yet

- Dostoyevsky Torments and ThemesDocument30 pagesDostoyevsky Torments and ThemesReginald RakeNo ratings yet

- Literary Genres QuizDocument1 pageLiterary Genres QuizCATHERINE MAE GUBATANANo ratings yet

- 21st OED Exam 2nd QuarterDocument5 pages21st OED Exam 2nd QuarterCijes100% (1)

- DDocument6 pagesDLuca CavagnoliNo ratings yet

- Lord Randal WorksheetDocument2 pagesLord Randal WorksheetNynn Juliana GumbaoNo ratings yet

- (Book 2) Story Maps - 12 Great ScreenplaysDocument96 pages(Book 2) Story Maps - 12 Great ScreenplaysNgoc Huy Dang100% (3)

- Alleged Quotations From The Necronomicon Al Azif of The Mad Arab Abdul AlhazredDocument22 pagesAlleged Quotations From The Necronomicon Al Azif of The Mad Arab Abdul AlhazredxdarbyNo ratings yet

- Simple Past and Past ContinuousDocument4 pagesSimple Past and Past Continuousleni tiwiyantiNo ratings yet

- Midterm-Int-05 Ana Paula VieraDocument4 pagesMidterm-Int-05 Ana Paula VieraVIERA RAMOS ANA PAULANo ratings yet

- Pale Fire'S Black Crown: James RameyDocument18 pagesPale Fire'S Black Crown: James RameyAlin M. MateiNo ratings yet

- Harry Potter and The Sorcerer's Stone: Importance of Archetypal CharactersDocument1 pageHarry Potter and The Sorcerer's Stone: Importance of Archetypal CharactersChristine SuarezNo ratings yet

- 2 - Kalpanas CycleDocument20 pages2 - Kalpanas CyclePRAMIT SENGUPTANo ratings yet

- Lesson2 Present Simple NouDocument3 pagesLesson2 Present Simple NouLaura Mihaela BudeaNo ratings yet

- Deca HurinovaDocument20 pagesDeca HurinovaBetondo BetonaNo ratings yet

- ExilesDocument2 pagesExilesRio PramanaNo ratings yet

- PRL 1 ELC 151 Reading Log ELC151Document2 pagesPRL 1 ELC 151 Reading Log ELC151Mohd Azmezanshah Bin SezwanNo ratings yet

- Grade 3: Student BookletDocument17 pagesGrade 3: Student BookletBala GiridharNo ratings yet

- SP 19Document73 pagesSP 19Barbie Turic100% (1)

- Cheat PokemonDocument59 pagesCheat Pokemonnada zakiahNo ratings yet

- Theory of Translation - Vanuhi KhachatrianDocument2 pagesTheory of Translation - Vanuhi KhachatrianVanuhi KhachatrianNo ratings yet

- What Makes A Detective - Character in Detective FictionDocument20 pagesWhat Makes A Detective - Character in Detective FictionSecret SecretNo ratings yet

- Lesson 4.7 - Philippine LiteratureDocument24 pagesLesson 4.7 - Philippine LiteratureAlyssa BobadillaNo ratings yet

- City of The RatsDocument10 pagesCity of The RatsLucy HeartfilliaNo ratings yet

- Made by - Subhaasish Agrawal 8BDocument5 pagesMade by - Subhaasish Agrawal 8BSubhaasish AgrawalNo ratings yet

- Birthday BonanzaDocument3 pagesBirthday BonanzaCloonyNo ratings yet

- Smallville - 2x09 - Dichotic - Dvdrip.enDocument39 pagesSmallville - 2x09 - Dichotic - Dvdrip.enSANEPAR PRIVATIZAÇÃO JÁNo ratings yet

- Bixby OdtDocument3 pagesBixby OdtIrene CasellasNo ratings yet

- Explain!: The Two Main Divisions of Literature: Prose and PoetryDocument5 pagesExplain!: The Two Main Divisions of Literature: Prose and PoetryAubrey MalacasNo ratings yet

- Đề Luyện Thi Học Sinh Giỏi Anh 9: I. Choose the best answer among A, B, C or D: (15 points)Document4 pagesĐề Luyện Thi Học Sinh Giỏi Anh 9: I. Choose the best answer among A, B, C or D: (15 points)tranNo ratings yet

- The Tell Tale Heart Research PaperDocument7 pagesThe Tell Tale Heart Research PaperLAYLA •No ratings yet

- Harry Potter and The Order of The Phoenix Ch. 1-5Document2 pagesHarry Potter and The Order of The Phoenix Ch. 1-5Vicky ZuritaNo ratings yet