Professional Documents

Culture Documents

IJAIR_3289_FINAL

Uploaded by

DANRHEY BALUSDANCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

IJAIR_3289_FINAL

Uploaded by

DANRHEY BALUSDANCopyright:

Available Formats

International Journal of Agriculture Innovations and Research

Volume 9, Issue 6, ISSN (Online) 2319-1473

Manuscript Processing Details (dd/mm/yyyy):

Received: 31/12/2020 | Accepted on: 05/05/2021 | Published: 22/05/2021

Cost-Economic Analysis of Carrot Production in

Hisar District of Haryana

Dr. Promilakrishna Chahal

Assistant Scientist, FRM, COHS, Chaudhary Charan Singh Haryana Agricultural University, Hisar, Haryana,

India.

Abstract – The present study was conducted to examine carrot production farming as well as to analyze the

economic involvement and benefit received by the farmers. The research was undertaken in Behbalpur village of the

Hisar district of Haryana, which was selected purposively on basis of high producers of carrot in Hisar district from

which 30 carrot growers were randomly selected from the village. The study found that total expenditure in carrot

production was Rs. 58,472 (tractor) and Rs 63,222 (labour) in one acre of agricultural land. Maximum expenditure

was noticed in collecting carrot, separating green activities (Rs. 12,000), which were done after harvesting followed by

harvesting (Rs. 9,500) and irrigation (Rs. 5,072). The total production of carrot in one-acre land was 11,250kg which

was equal to 112.5 quintals. Gross return in one-acre carrot production was Rs. 1,35,000 with a net return of Rs.

76,528 (if harvesting was done by tractor) and 71,778 (if harvesting was done by labour). So based on this economic

analysis, the benefit-cost ratio was 1.76 (by tractor) and 1.88 (by labour), respectively. The major production

problems faced by the farmers in carrot farming were high fuel costs ( x = 4.3), breakdown of irrigation systems ( x =

3.9) and pests and diseases ( x = 3.4). Regarding marketing problems of carrot, farmers were found to be facing

problems related to poor communication with traders ( x = 4.2), and poor understanding among farmers ( x = 4.1)

and high competition with importers ( x = 3.9).

Keywords – Cost-Economy, Benefit, Carrot Growers, Harvesting.

I. INTRODUCTION

Carrot is an important vegetable because of its large yield per unit area and its increasing importance as

human food. It is orange-yellow, which adds attractiveness to foods on a plate, and makes them rich in carotene;

a precursor of vitamin A. It contains abundant amounts of nutrients such as protein, carbohydrate, fibre, vitamin

A, potassium, and sodium (Ahmad et al., 2005). Carrot, like other vegetables, is a short duration crop and the

farming community earns enormous profits through its cultivation. The farmers had a small chunk of land

holdings and surplus family labour to earn a huge amount of profit by growing this vegetable because the carrot

crop requires less amount of inputs and plant protection measures. The duration of the carrot crop is 90 to 100

days or 3 months which may vary according to the seed selected for sowing. The required seed rate for carrot

farming is 2 kg carrot seed per acre. The farmer can expect a yield of 7 to 8 tons or 7000 to 8000 kg from 1-acre

carrot farming. The carrot grower can immediately send to the nearest vegetable market for selling within 3 to 4

days after harvesting. However, if the carrots are stored post-harvest, they can remain fresh for up to 3 to 4

months or 100 days if stored at 0 to 4.4 degree Celsius, (Reddy, 2019). As carrots are grown both in rural and

urban areas, their potential for generating employment is an added advantage to improve the economic

conditions of the weaker segment of the society. The leaves of this crop are also used as fodder for farm

animals. This is an additional advantage, as at times the supply of fodder is scarce in the region. Thus it is multi-

dimensional activity and can serve the economy in various ways due to its higher yield potential, higher return,

high nutritional value and highly labour-intensive attributes (Tahir and Altaf, 2013). So, the present study was

planned to assess the present status of the carrot cultivation in the Hisar district of Haryana, identify the

Copyright © 2021 IJAIR, All right reserved

385

International Journal of Agriculture Innovations and Research

Volume 9, Issue 6, ISSN (Online) 2319-1473

problems of the farmers, production, and yield of carrots, and study the socio-economic conditions as well as

production and marketing problems of the carrot farming community.

II. METHODOLOGY

For this study, Behbalpur village of Hisar district was purposively selected with the consultation of the

Directorate of Research, CCSHAU, Hisar. A total of 30 farmers (male and female), were taken by using a

random sampling technique. A well-structured and field pre-tested comprehensive interviewing schedule was

used for the collection of detailed information on various aspects of carrot crop production. Survey data

contained information on the socio-economic characteristics of the farmers, activities involved in carrot

production and input-output quantities. For economic analysis, the Benefit-cost ratio was used to determine the

profitability of carrot growing. A simple budgeting technique has been employed to estimate the cost and returns

of carrot production. Carrot cost of production was estimated by incorporating all costs such as Field preparation

cost (FPCc), Sowing cost (Sc), Fertilization cost (Fc), line making cost (LMc), Bed making cost (BMc),

Irrigation cost (Ic), Pesticides cost (PCc), Harvesting cost (HRVc) Collecting carrot, (Cc) separating green

(CcSGc), Transportation cost (TPc) and Washing cost (Wc)

The variable cost (VCc) for carrot production was calculated by the following expression; VCc = FPc+ Sc+

Fc+ LMc+ BMc+ Ic+ PCc+Wc+ HRVc+ CcSGc+Pc+ TPc+ Wc

Further, the total cost was calculated by incorporating land rent (LRc) in variable cost. Miscellaneous cost

includes farmyard manure cost, weeding cost and pesticide cost. The estimated expression is given below: TPc

= VCc+ LRc

In the next step, the gross revenue (GRc) of carrot production was calculated by multiplying gross yield/acre

(GYa) with price/kg (PpK ) received by carrot growers. GRc = GYa×PpK

Furthermore, net returns to carrot growers were estimated by the following expression. NRc = GRc-TCc

Furthermore, the benefit-cost ratio was calculated to estimate the return on per rupee investment through the

division of revenues to the total cost. BCR = GR/NR

Table 1. Benefit-cost ratio of carrot production (one acre).

Variable Particular

Total production (TPc) variable cost (VCc)+ land rent cost (LRc)

Gross return (GR) gross yield/acre (GYa) × price/kg (PpK )

Net Return (NR) Gross return (GR)- Total cost (Tc)

Benefit cost ratio (BCR) Gross return (GR) / Net Return NR

All the analyses were done based on per acre because of the ease of computation and availability and nature

of data. For statistical analysis frequency, percentage and weighted means were used for giving data a

significant shape.

III. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The present study was conducted to find out the existing condition of carrot farming in Haryana. The present

study was conducted on 30 farmers (43.3 % male and 56.7 % female) who were found to be engaged in the

Copyright © 2021 IJAIR, All right reserved

386

International Journal of Agriculture Innovations and Research

Volume 9, Issue 6, ISSN (Online) 2319-1473

carrot production system. Similar results were obtained by Joshi and Kalauni (2018) that greater numbers of

females i.e. 58.75% were involved in agriculture than compared to men (32.5%) in vegetable farming. The data

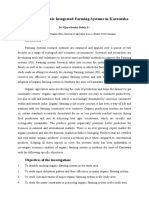

in Fig.1 show that 60.0 per cent of respondents belonged to the age group of 32-42 years; followed by 23.3 per

cent having age between 42.1- 53 years and 16.7 per cent were between the ages of 53.1-63 years. Data

regarding the education of the respondents’ shows that one-third of the respondents (33.3%) were having

education up to high school, followed by matric (26.7 per cent) and bachelor degree (16.7 %). A few per cent of

the respondents were having the education of middle (13.3 %) and master (10.0 %). Maximum respondents

(93.3 %) were having farming as their main occupation. Only 6.7 per cent of respondents were found to be

involved in a government job with farming. The majority of the respondents (86.7 per cent) were having a land

area of 2.5-10.0 acres followed by 10.0 per cent and 3.3 per cent were having an agricultural land area of 10.1-

18.5 acres and 18.6-25.0 acres, respectively. Findings in the table further reflect that more than fifty per cent

respondents (60.0%) were having carrot production on 1.6acres to 2.5 acres of land followed by 26.7 per cent

farmers were having 0.5-1.5 acres of land under carrot production and 13.3 per cent farmers were found to be

producing carrot on 2.5-4.0 acres of agricultural land.

93.3

86.7

56.7 60 60

Percentage

43.3

33.3

23.3 26.7 26.7

16.7 13.3 16.7 13.3

10 6.7 10

3.3

Male

42.1-53

53.1-63

Matric

2.5-10.0

32-42

Female

Govt. Job

18.6-25.0

Middle

10.1.-18.5

0.5-1.5

1.6-2.5

2.5-4.0

Farming

Master

Bachelor

High school

Gender Age (in years) Education Main Land owned (acre) Area of carrot grown

occupation (acre)

Fig. 1. Personal profile of respondents.

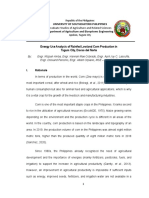

As Fig. 2 shows in carrot production 14 activities were included as; field preparation, sowing, line making,

bed making, irrigation, fertilizing, weeding, pesticides spray, harvesting, collection of carrot, separating green,

packing, transportation and washing. Time requirement and labour involvement in each activity were different.

Many of the activities were labour intensive like; weeding, harvesting, collection of carrot, separating the green

from carrot, loading and irrigation.

Table 2 shows the time required for each activity. Findings show that field preparation, sowing, line making,

bed making and fertilizing were done in the first three days. Result depict that irrigation was done throughout

the cropping season of carrot by an interval of 7-10 days. Total 7-8 times irrigation was required by the crop for

proper growth. The weeding process (up to 10 days) was done after 22 days of sowing and which found to be

continuing up to 30 days of the cropping season. Pesticide spray was done just after the weeding activity to

control the weeds. The last six tasks including; harvesting, collection of carrot, separating green, packing,

transportation and washing required 8-10 days depended on the method of harvesting was used. As per findings,

Copyright © 2021 IJAIR, All right reserved

387

International Journal of Agriculture Innovations and Research

Volume 9, Issue 6, ISSN (Online) 2319-1473

carrot farming was found to be an 85-90 days crop. According to the project report of Reddy, 2019 the duration

of carrot crop was 90-100 days or 3 months which may vary according to seed selected for sowing.

Fig. 2. Activities involved in carrot production.

Table 2. Time involvement in each activity.

10- 13- 16- 19- 22- 25- 28- 31- 34- 37- 40- 43- 46- 49- 52- 55- 58- 61- 64- 67- 70- 73- 76- 79- 82- 85- 88-

1-3 4-6 7-9

12 15 18 21 24 27 30 33 36 39 42 45 48 51 54 57 60 63 66 69 72 75 78 81 84 87 90

Field

preparation

Sowing

Line making

Bed making

Irrigation

Fertilizers

Weeding

Pesticides

Harvesting

Collecting

carrot

Separating

green

Packing

Transportati-

-on

Washing

Data in Fig. 3 revealed that carrot farming activities were mostly done by male respondents but two activities

(weeding and separating) were only performed by female respondents. Besides this majority of females, farmers

were found to be involved in weeding (57.7%), collecting carrot (57.7%), separating green (57.7%),

packing/loading (57.7%) and harvesting (26.7%). As per findings, labour-intensive activities were mainly done

by female farmers/ respondents. Females were found to involve more in transplanting (83.8%) and cleaning and

harvesting (83.8%) activities, which are considered to be less skilled (Joshi and Kalauni 2018). Activities that

required outdoor communication, decision making and marketing were found to be done by male respondents.

Similarly, Zewdu et al. (2016) revealed that in most cases, men are the heads of households and are therefore the

principal decision-makers in the household however some consultation with women may take place.

Mrunaliniand and Snehalatha, (2010) found that the role of women in crop production was more active by their

Copyright © 2021 IJAIR, All right reserved

388

International Journal of Agriculture Innovations and Research

Volume 9, Issue 6, ISSN (Online) 2319-1473

total share in activities. This is because 37 per cent of activities are performed by women either exclusively or

by their domination of number. Whereas the men exclusive or domination by number was seen in only 26 per

cent of crop activities. UN (2015) found that though most of the men are performing the job they are informally

involved in agricultural activities. And they become the principal decision-makers of the overall activities

including agriculture.

70

60

50

Percenatge

40 Male

30 Female

20

10

0

0 2 4 6 8 10 12 14 16

Activities

Fig. 3. Involvement pattern of respondents in carrot production.

The input used and cost of carrot production in a one-acre land,

1. Field Preparation (Fc):

For carrot production, agricultural land was prepared accordingly. Two ploughings were given and ridges and

furrows were formed at 30 cm spacing. The cost for the field includes tractor cost and labour cost was Rs.

2500/-.

2. Sowing (Sc):

Sowing was done manually (by hand) by farmers. For a one-acre land total of 8 kg carrot seeds were required.

The rate of seeds was Rs. 250/kg, and total Rs. 2000/- were spend on seeds. August-September is the best time

for sowing carrots (Anonymous, 2018).

3. Fertilizers (Fc):

One packet of each; DAP, Zinc and Sulphur were used in a one-acre area of carrot production. The first

application of fertilizer (DAP-45 kg) was found to be done at the time of sowing. Then carrot farming required

the application of Zinc and Sulphur fertilizers when the top head of the crop reached 3 inches tall. Total

expenditure on fertilizers was Rs. 2700 per acre.

4. Line making (Lc):

After sowing seed and fertilizing the land, lines were made by tractor in carrot production field; a total of 96

lines were made in one acre of land which cost was Rs. 500.

5. Bed Making (BMc):

A raised bed provides carrot with perfect soil condition to reach their full potential. This activity was done by

labour. It requires two workers for two days with the cost of Rs. 250/- per worker per day. So the total cost of

bed making was Rs. 1000/-.

Copyright © 2021 IJAIR, All right reserved

389

International Journal of Agriculture Innovations and Research

Volume 9, Issue 6, ISSN (Online) 2319-1473

6. Irrigation (Ic):

About a week after plantation/sowing the seeds, the first irrigation was done. After then irrigation was

required at an interval of every 10-12 days throughout the carrot production system. Total eight times irrigation

was done in carrot crop. Carrot farming required about an inch of water per week to reach its full production.

Water at least one inch per week to start, then two inches as roots mature (Stillman et al., 2018). The total cost

(Rs. 5072) included diesel charge and labour wages for irrigating.

7. Weeding (Wc):

The unwanted plants that grow in-between crops were called weeds. The process of removal of such

unwanted plants is called weeding. After cultivation, weeding is to be done in 15 days. Thinning and earthing up

should be given on the 30th day, (Reddy, 2015) Weeding in carrot farming was mainly done by female labour

usually after 20 days of sowing. For one acre 4 labours were required for 3 days. The total cost was Rs. 2000.

8. Pesticides (Pc):

There were many pests attack and diseases were found in carrot crop like carrot rust, damping off, black root,

bacterial leaf blight, white mould, beetle etc. For controlling these pests and diseases pesticides spray was done

in carrot crop just after the weeding process. The farmers were found to be applying pesticide once in a crop,

which charged Rs. 550 (including labour).

9. Harvesting (HRVc):

Harvesting was found to be done after 81 days of sowing. Harvesting was done in two ways; machine

(tractor) or manually (labour). The cost for both was different. The cost of harvesting through tractor was Rs.

4750 and manually was Rs. 9500.

Table 3. The input used and cost of carrot production in one-acre land.

Sr. No Particular Unit Quantity Rate (Rs.) Cost (Rs.)

1 Field preparation (FPc) Total Hours - - 2,500

2 Sowing (Sc) Kg 8 kg 250 2,000

Fertilizers (Fc) Labour 3 250

DAP Kg 45 1250 750

3

Zink Kg 5 350 1,950

Sulphur Kg 5 350

4 Line making (Lc) Tractor - - 500

Bed making (BMc) Total Hours 4

5 250 1,000

Labour 4

Irrigation (Ic) Diesel 48 64 3,072

6

Labor 8 250 2,000

Pesticides (PCc) Cost 300 550

7

Labor 1 250

Copyright © 2021 IJAIR, All right reserved

390

International Journal of Agriculture Innovations and Research

Volume 9, Issue 6, ISSN (Online) 2319-1473

Sr. No Particular Unit Quantity Rate (Rs.) Cost (Rs.)

Weeding (Wc) Days 3 3,000

8

Labor 4 250

9 Harvesting (HRVc) Tractor* 95 50 4,750

Labor** 95 100 9,500

Collecting carrot, Labor 5 300 6,000

10

Day 2

Separating green (CcSGc) Labor 5 300 6,000

11

Day 2

12 Packing (Pc) and loading Packet (bori) 300 16 4,800

13 Transportation (TPc) Tractor 4 500 2,000

14 Washing (Wc) Machine 300 22 6,600

15 land rent (LRc) 1 acre 6 months 11,000

Total Production cost (TPc) Tractor* 58,472

15

Labor** 63,222

*Tractor was used for harvesting the carrot **labour was used to harvest the carrot from the field.

1. Collecting Carrot, Separating Green and Packing (CcSGc):

For doing after harvesting carrot activities (Collecting carrot, separating green and packing) on one acre of

land 10 labours were required for 10 days. The total cost for these three activities was Rs. 16,800, which

included labour charge for 4 days and the cost of packing material (Bori). A total of 250 bags were made and

each was having 45 kg of carrot. So the total production of carrot was 11,250 kg (112.5 Quintal) in one care of

farming.

2. Transportation (Tc):

Total cost of transportation was Rs. 2000, which was the tractor charge for 4 trips.

3. Washing (Wc):

Done by machine with charges of Rs. 22 per package. So the total cost was Rs. 6600 for cleaning the carrot.

4. Total Production Cost (TPc):

Total production of carrot in one-acre land was Rs. 47,472 (by using the tractor for harvesting) and 52,222

(harvesting done by labour).

As per a study done by Naik and Kannan, 2018, the cost of carrot cultivation on an acre was estimated as Rs.

38,871 which included total fixed cost and variable cost. The average yield per acre was found to be 150q/ha

which was sold out at the rate of Rs 10 per kg. For this total income in an acre, carrot production was 1,50,000.

The benefit-cost ratio was estimated to be 2.85:1.

Table 4 gives a clear picture of the benefit-cost ratio of the carrot production system. As per findings, it was f-

Copyright © 2021 IJAIR, All right reserved

391

International Journal of Agriculture Innovations and Research

Volume 9, Issue 6, ISSN (Online) 2319-1473

-ound that the total production of carrot on one acre was 11,250 kg (112.5 Quintal) which was Rs. 1,35,000 as a

gross return. Because the harvesting was done by two methods; tractor and manually, so the calculation of the

benefit-cost ratio was also done according to both way. Net return in term of rupees was Rs. 76,528 (by tractor)

and Rs. 71,778 (manually). As per the calculation of the benefit-cost ratio, the BC ratio was 1.76 and 1.88 by

tractor and manually, respectively. Inline, similar results were obtained by Mahmood et al. (2017) in his

research on ‘Profitability Analysis of Carrot Production in Selected Districts of Punjab’ that overall yield

production was 10780.0kg/acre with price/kg of Rs. 11.81. Overall average gross revenue attained by carrot

growers in carrot farming was Rs. 158235.58/acre with net revenue of Rs. 66436.17/acre and benefit-cost ratio

of Rs. 1.64/rupee investment. The study postulated that the gross return of carrot production is significantly

affected by human labour, tillage operation, seeds, fertilizers, irrigation, insecticide and manure.

Table 5. The benefit-cost ratio of carrot production (one acre).

Variable Particular Output

Total production Total production of carrot per acre 11,250 kg (112.5 Quintal)

Gross return (GR) Gross yield/acre (GYa) ×price/kg (PpKc ) 11.250X12=Rs. 1,35,000

1,35,000-58,472=76,528 (by tractor)

Net Return (NR) Gross return (GR)- Total cost (TCc)

1,35,000-63,222=71,778 (labour)

1.76 (by tractor)

Benefit cost ratio (BCR) Gross return (GR) / Net Return NR

1.88 (by labour)

Eight problems in horticultural production were identified and were ranked according to their seriousness. As

per findings high fuel costs ( x = 4.3), breakdown of irrigation systems ( x = 3.9) and pests and diseases ( x =

3.4) were the major production problems in the carrot production system with a rank of I, II and III,

respectively. Data further revealed that insufficient infrastructure, lack of finance, high input costs, poor access

to inputs and poor soil fertility were also the problems faced by farmers during the production system of carrot.

Table 6. Problems faced by farmers in carrot production.

Weighted Weighted

Variable Rank Variable Rank

Mean Mean

High fuel costs 4.3 I Poor communication with traders 4.2 I

Breakdown of irrigation system 3.9 II Poor understanding among farmers 4.1 II

Production Problem

Marketing problem

Pest and disease 3.4 III High competition with imports 3.9 III

Insufficient production 3.2 IV Poor marketing infrastructure 3.8 IV

Lack of finance 3.1 V Lack of marketing skill 3.1 V

High input cost 2.9 VI Lack of knowledge 2.8 VI

Poor access to input 2.5 VII High transportation cost 2.2 VII

Poor soil fertility 1.7 VIII Inadequate demand produce 1.9 VIII

Problems about the marketing system represent that major problems faced by farmers were poor

communication with traders, poor understanding among farmers and high competition with imports with

weighted mean scores of x = 4.2, x = 4.1 and x = 3.9 respectively. Findings show that Poor marketing

Copyright © 2021 IJAIR, All right reserved

392

International Journal of Agriculture Innovations and Research

Volume 9, Issue 6, ISSN (Online) 2319-1473

infrastructure ( x = 3.8), Lack of marketing skill ( x = 3.1), Lack of knowledge ( x = 2.8), High transportation

cost ( x = 2.2) and Inadequate demand for produce ( x = 1.9). The major problems faced by growers in the

production of carrot were reported as quality seed, insect pest and disease, lack of institutional credit, shortage

of irrigation, scarcity of labour, lack of remunerative price, price fluctuation and pricing not according to

quality, (Singh, 2006).

IV. SUMMARY AND CONCLUSION

As per the present study, carrot farming was the major crop of Behbalpur village, in which maximum farmer

was found to be involved. Carrot farming was found to be a 90 days crop by involving a series of activities

including; field preparation, sowing, line making, bed making, irrigation, fertilizing, weeding, pesticides spray,

harvesting, collection of carrot, separating green, packing, transportation and washing. Most carrot production

activities were labour intensive and required high attention starting from sowing till harvesting. As per the study

the maximum cost of found to be involved in harvesting (Rs. 9,500/-), washing (Rs. 6,600/-) collecting and

separating green (Rs. 6,000 in each) and packing and loading (Rs. 4,800/-). By including land rent and cost of

all activities, the total production cost of carrot production in one-acre land was Rs. 63,222/-. The economic

analysis however indicates that carrot farming is a profitable business and promises the farmers a return of Rs.

1.88 per rupee investment. Major problems faced by farmers in carrot farming were poor communication with

traders, poor understanding among farmers and high competition with imports (Lisenda, 2007).

REFERENCES

[1] Ahmad, B., Hassan, S., Bakhsh, K. Factors affecting yield and profitability of carrot in two districts of Punjab. International Journal of

Agriculture & Biology, 2005:7(5):794–798.

[2] Joshi, A. and Kalauni, D. 2018. Gender role in vegetable production in rural farming system of Kanchanpur, Nepal Saarc. J. Agri.,

2018: 16(2): 109-118.

[3] Lisenda, L. 2007. Horticultural study on fresh fruit and vegetables in Botswana.Unpublished Report.2007. Local Enterprise Aut hority,

Botswana

[4] Mahmood, I., Assan, S., Bashir A., Qasim, M. and Ahmad, N. 2017. Profitability analysis of carrot production in selected districts of

Punjab, Pakistan: An empirical Investigation, 2017.

[5] Mrunalini, A. and C Snehalatha, C. Drudgery experiences of gender in crop production activities J Agri. Sci., 2010:1(1): 49-51.

[6] Naik, H., Kannan. M. 2018. Cost of cultivation. Temperate vegetable, 2018. Retrieved on June 22, 20 http://ecoursesonline.iasri.res.in/

mod/page/view.php?id=12200

[7] Reddy, J. Carrot farming: Income, Cost, Profit, Project report. Agri. Garming. 2019. Retrieved on June 19, 20 https://www.agri

farming.in/carrot-farming-income-cost-profit-project-report

[8] Reddy, J. Carrot farming: techniques, tips and ideas. Agri farming.2015. Retrieved on June 23, 20 https://www.agrifarming.in/carrot-

farming

[9] Singh, M. 2006. An Economic analysis of production and marketing of vegetable crops in Hisar district of Haryana.(M.Scdissertation),

CCS Haryana Agricultural University, Hisar.2006. https://krishikosh.egranth.ac.in/handle/1/88160

[10] Stillman, J., Hale, J. D., Burnett, J., Stonehill, H., Perreault, S., Boeckmann, C. 2018. How to plant, Grow, and Harvest carrots,

Growing carrots. The old farmer’s almanac.2018. https://www.almanac.com/plant/carrots

[11] Tahir A. and Altaf, Z. 2013. Determinants of income from vegetables production: A comparative study of normal and off-season

vegetables in Abbottabad. Pakistan Journal of Agricultural Research, 2013:26(1):24-31.

[12] UN. 2015. The World’s Women 2015 trends and statistics. Department of Economic and Social Affairs, 2015. New York, United

Nations.

[13] Zewdu, A., Zenebe, G., Abraha, B., Abadi, T., Gidey, N. 2016. Assessment of the Gender role in agricultural activities at Damota

Kebele of Haramaya District, Eastern Hararghe Zone, Ethiopia. Journal of Culture, Society and Development 2016: 26: 20-26.

AUTHOR’S PROFILE

Dr. Promilakrishna Chahal, Presently working as Assistant Scientist in the Department of Family Resource

Management, CCS Haryana Agriculture University, Hisar. She has working experience of 7 years in teaching and

research and published many research papers in national and international journals. She is a Member of the Editorial/

Advisory Board Of “Journal of Shrinkhala” (ISSN: 2321-290X) UGC approved and “Agriculture Letters (ISSN: 2582-

6522)” A monthly peer-reviewed newsletter for agriculture and allied sciences. She is working under two projects of

AICRP (All India Coordinating Research Project) on women in agriculture.

Copyright © 2021 IJAIR, All right reserved

393

You might also like

- Tle 10 - Summative Test - SecondDocument2 pagesTle 10 - Summative Test - SecondMariel Lopez - Madrideo100% (3)

- Neem Cultivation Techniques and UsesDocument9 pagesNeem Cultivation Techniques and UsesmandaremNo ratings yet

- Potato ProductionDocument42 pagesPotato ProductionsccscienceNo ratings yet

- NCERT Science VIII BookDocument260 pagesNCERT Science VIII Booknikhilam.com77% (26)

- CashewDocument18 pagesCashewAloy Dela CruzNo ratings yet

- DSSAT Modelling For Dryland SystemsDocument28 pagesDSSAT Modelling For Dryland SystemsBarani Agriculture BaraniNo ratings yet

- Costs and Returns of Major Cropping Systems in Northern Transition Zone of KarnatakaDocument4 pagesCosts and Returns of Major Cropping Systems in Northern Transition Zone of KarnatakaDhungana SuryamaniNo ratings yet

- Precision Agriculture Adoption: Challenges of Indian AgricultureDocument8 pagesPrecision Agriculture Adoption: Challenges of Indian AgriculturePrajwal PatilNo ratings yet

- Performance of Green Bean (Phaseolus Vulgaris L.) Varieties in Response To Poultry Manure in Sudan Savanna of Nigeria-IJRASETDocument9 pagesPerformance of Green Bean (Phaseolus Vulgaris L.) Varieties in Response To Poultry Manure in Sudan Savanna of Nigeria-IJRASETIJRASETPublicationsNo ratings yet

- 09 RK VishwakarmaDocument13 pages09 RK VishwakarmaM. Bayu MarioNo ratings yet

- Agronomic Performance and Yield of Hybrid Rice GenDocument10 pagesAgronomic Performance and Yield of Hybrid Rice GengagaNo ratings yet

- An Economic Analysis of Cabbage Production: March 2022Document8 pagesAn Economic Analysis of Cabbage Production: March 2022Teshome H/GebrealNo ratings yet

- Binamoog-8 PaperDocument4 pagesBinamoog-8 PaperKrishibid Syful IslamNo ratings yet

- Commercial Hybrid Seed Production Impacts on Tomato, Okra FarmersDocument18 pagesCommercial Hybrid Seed Production Impacts on Tomato, Okra FarmersArgus EyedNo ratings yet

- To Study About Production and Economics Analysis of Major Vegetable Crops in K.V.K Purnea BiharDocument3 pagesTo Study About Production and Economics Analysis of Major Vegetable Crops in K.V.K Purnea BiharEditor IJTSRDNo ratings yet

- Farmers' Perception On Potato Pests and Yield Loss Assessment by Red Ant and White Grub On Potato in Ramechhap, NepalDocument17 pagesFarmers' Perception On Potato Pests and Yield Loss Assessment by Red Ant and White Grub On Potato in Ramechhap, Nepaldiyogkarki3No ratings yet

- FIX Jurnal Robiatul Adawiyah Analisis Keuntungan Usahatani Kentang Dan Faktor Yang Mempengaruhinya Di Kab Kerinci 2022 SibatikDocument24 pagesFIX Jurnal Robiatul Adawiyah Analisis Keuntungan Usahatani Kentang Dan Faktor Yang Mempengaruhinya Di Kab Kerinci 2022 SibatikUsman JayadiNo ratings yet

- S. Senthilkumar2, Et AlDocument8 pagesS. Senthilkumar2, Et Alabhiabhi8549850904No ratings yet

- Measuring Technical Efficiency of Bottle Gourd and Brinjal Farming in Dhaka District of Bangladesh: Stochastic Frontier ApproachDocument7 pagesMeasuring Technical Efficiency of Bottle Gourd and Brinjal Farming in Dhaka District of Bangladesh: Stochastic Frontier ApproachShailendra RajanNo ratings yet

- A Study On Organic Integrated Farming Systems in Karnataka: Objectives of The InvestigationDocument6 pagesA Study On Organic Integrated Farming Systems in Karnataka: Objectives of The InvestigationVijaychandra ReddyNo ratings yet

- Economics of Potato Cultivation in Jaunpur and Ghazipur District of Eastern Uttar PradeshDocument4 pagesEconomics of Potato Cultivation in Jaunpur and Ghazipur District of Eastern Uttar PradeshRamratanSinghNo ratings yet

- Is Potato Market Efficient in Ethiopia? Evidence From Farta District of Amhara RegionDocument13 pagesIs Potato Market Efficient in Ethiopia? Evidence From Farta District of Amhara RegionHasrat ArjjumendNo ratings yet

- 16IJASRAUG201916Document12 pages16IJASRAUG201916TJPRC PublicationsNo ratings yet

- Ijara 4889Document5 pagesIjara 4889Allen AlbertNo ratings yet

- EnergyBudgetingPaperIJAS8961017 22Document7 pagesEnergyBudgetingPaperIJAS8961017 22Harlet EsquivelNo ratings yet

- Diversification of Cropping Systems ForDocument10 pagesDiversification of Cropping Systems Forkhbjv bdhbebheNo ratings yet

- Mitikuetal 2022Document28 pagesMitikuetal 2022yonas ashenafiNo ratings yet

- 14-Rajdeep-Singh (2)Document7 pages14-Rajdeep-Singh (2)Gagandeep GillNo ratings yet

- Tomato Cultivation EconomicsDocument9 pagesTomato Cultivation EconomicsMaes SamNo ratings yet

- 144 Jbar Productivity and Profitability of Mandarin Cultivation in Selected Areas of Bangladesh PDFDocument9 pages144 Jbar Productivity and Profitability of Mandarin Cultivation in Selected Areas of Bangladesh PDFAkm Golam Kausar KanchanNo ratings yet

- Admin,+14395 52353 1 CEDocument10 pagesAdmin,+14395 52353 1 CEMark James B. LaysonNo ratings yet

- Sustainability of Rice Cultivation in India: December 2020Document4 pagesSustainability of Rice Cultivation in India: December 2020raghavNo ratings yet

- A Comparison of Cabbage Crop Growth Parameters and Harvest Maturity Indices Under Different Planting Methods, With An Emphasis On Mechanical HarvestingDocument5 pagesA Comparison of Cabbage Crop Growth Parameters and Harvest Maturity Indices Under Different Planting Methods, With An Emphasis On Mechanical HarvestingShailendra RajanNo ratings yet

- Enhancing Onion Productivity Through Integrated Crop Management PracticesDocument3 pagesEnhancing Onion Productivity Through Integrated Crop Management PracticesPreeti HiremathNo ratings yet

- Feasibility Analysis of Cassava Farming Income inDocument7 pagesFeasibility Analysis of Cassava Farming Income inMartine Debbie CorreNo ratings yet

- 14IJASRDEC201814Document10 pages14IJASRDEC201814TJPRC PublicationsNo ratings yet

- Paper Ijas SKR 2019Document9 pagesPaper Ijas SKR 2019AmanNo ratings yet

- Research Article: Mehran Ahmad, Syed Attaullah Shah and Shahid AliDocument11 pagesResearch Article: Mehran Ahmad, Syed Attaullah Shah and Shahid AliM AsifNo ratings yet

- Genetic Variability, Heritability and Genetic Advance in Potato (Solanum Tuberosum L.) For Processing Quality, Yield and Yield Related TraitsDocument9 pagesGenetic Variability, Heritability and Genetic Advance in Potato (Solanum Tuberosum L.) For Processing Quality, Yield and Yield Related TraitsPremier PublishersNo ratings yet

- Farmers' Perception and Adoption of Agroforestry Practices in Faridpur District of BangladeshDocument8 pagesFarmers' Perception and Adoption of Agroforestry Practices in Faridpur District of BangladeshIJEAB JournalNo ratings yet

- JHassan FHoque Elsevier Economics Paper 15sept22Document9 pagesJHassan FHoque Elsevier Economics Paper 15sept22AranNo ratings yet

- Gokula Preethas & Amarnath. J. S Gokula Preethas & Amarnath. J. SDocument10 pagesGokula Preethas & Amarnath. J. S Gokula Preethas & Amarnath. J. STJPRC PublicationsNo ratings yet

- Resource Use Efficiency of Hybrid Maize Production in Chhindwara District of Madhya PradeshDocument10 pagesResource Use Efficiency of Hybrid Maize Production in Chhindwara District of Madhya PradeshImpact JournalsNo ratings yet

- 17 Arun PanditDocument12 pages17 Arun PanditARIVALAGAN DURGANo ratings yet

- Energy Use Analysis of Rainfed Lowland Corn Production in Tagum CityDocument29 pagesEnergy Use Analysis of Rainfed Lowland Corn Production in Tagum CityApril Joy LascuñaNo ratings yet

- Influence of Row Spacing On The Grain Yield and The Yield Component of Wheat Triticum Aestivum L.Document5 pagesInfluence of Row Spacing On The Grain Yield and The Yield Component of Wheat Triticum Aestivum L.Editor IJTSRDNo ratings yet

- Farmers' Perspective About Organic Manure Production and Utilization in Dakshina Kannada, IndiaDocument10 pagesFarmers' Perspective About Organic Manure Production and Utilization in Dakshina Kannada, IndiaDukuziyaturemye PierreNo ratings yet

- Impact of Frontline Demonstration On Productivity and Profitability of Tenai Variety Co 7Document3 pagesImpact of Frontline Demonstration On Productivity and Profitability of Tenai Variety Co 7IJAR JOURNALNo ratings yet

- Modelling of The Contribution of Different Blended Fertilizers To Potato Production in Basketo Special Woreda, Gamo-Gofa Zone, EthiopiaDocument11 pagesModelling of The Contribution of Different Blended Fertilizers To Potato Production in Basketo Special Woreda, Gamo-Gofa Zone, EthiopiaHasrat ArjjumendNo ratings yet

- Economics of Organic Farming vs Conventional Farming in KarnatakaDocument8 pagesEconomics of Organic Farming vs Conventional Farming in KarnatakaPradeep patilNo ratings yet

- Assessment of Input Output TransformatioDocument6 pagesAssessment of Input Output Transformatiomontebarrett11No ratings yet

- 6452 23252 1 PB PDFDocument11 pages6452 23252 1 PB PDFIbna Mursalin ShakilNo ratings yet

- Technical Efficiency and Its Determinants in Potato Production, Evidence From Punjab, Pakistan Abedullah, Khuda Bakhsh and Bashir AhmadDocument22 pagesTechnical Efficiency and Its Determinants in Potato Production, Evidence From Punjab, Pakistan Abedullah, Khuda Bakhsh and Bashir AhmadHassam ShahidNo ratings yet

- Costs and Returns Analysis of Groundnut in Koppal and Ballari DistrictsDocument4 pagesCosts and Returns Analysis of Groundnut in Koppal and Ballari DistrictsInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- IJASRFEB20175Document14 pagesIJASRFEB20175TJPRC PublicationsNo ratings yet

- NR 04 04 01 Behzadetal m00267Document12 pagesNR 04 04 01 Behzadetal m00267Hasrat ArjjumendNo ratings yet

- Economicsof Chilli Productionin IndiaDocument5 pagesEconomicsof Chilli Productionin IndiaABHINAV VIVEKNo ratings yet

- Economic Efficiency Analysis of Smallholder Sorghum Producers in West Hararghe Zone, Ethiopia.Document8 pagesEconomic Efficiency Analysis of Smallholder Sorghum Producers in West Hararghe Zone, Ethiopia.Premier PublishersNo ratings yet

- An Estimation of Technical Efficiency of Garlic Production in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa PakistanDocument10 pagesAn Estimation of Technical Efficiency of Garlic Production in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Pakistanazni herasaNo ratings yet

- Estimation of Farm Level Technical Efficiency in Smallscale Swamp Rice Production in Cross River State of Nigeria: A Stochastic Frontier ApproachDocument6 pagesEstimation of Farm Level Technical Efficiency in Smallscale Swamp Rice Production in Cross River State of Nigeria: A Stochastic Frontier ApproachUwaisuAdamNo ratings yet

- Effect of Spacing and Training On Growth and Yield of Polyhouse Grown Hybrid Cucumber (Cucumis Sativus L.)Document10 pagesEffect of Spacing and Training On Growth and Yield of Polyhouse Grown Hybrid Cucumber (Cucumis Sativus L.)Daysi BustamanteNo ratings yet

- The Public and Private Benefits From Organic Farming in PakistanDocument32 pagesThe Public and Private Benefits From Organic Farming in PakistansdsNo ratings yet

- Problems and Constraints in Banana Cultivation: A Case Study in Bhagalpur District of Bihar, IndiaDocument9 pagesProblems and Constraints in Banana Cultivation: A Case Study in Bhagalpur District of Bihar, IndiaVasan MohanNo ratings yet

- Effect of Fertigation On Growth, Yield and Quality of Okra (Abelmoschusesculentus L. Moench)Document6 pagesEffect of Fertigation On Growth, Yield and Quality of Okra (Abelmoschusesculentus L. Moench)Editor IJTSRDNo ratings yet

- Guidelines for Grazing and Livestock MonitoringFrom EverandGuidelines for Grazing and Livestock MonitoringNo ratings yet

- Winter Crop Variety Sowing GuideDocument128 pagesWinter Crop Variety Sowing GuideNath ChNo ratings yet

- Evaluation of The Cross-Pollination in Maize (Zea Mays L.) Synthetic Varieties Grown in The High Guinean Savannah Zone ConditionsDocument9 pagesEvaluation of The Cross-Pollination in Maize (Zea Mays L.) Synthetic Varieties Grown in The High Guinean Savannah Zone ConditionsMamta AgarwalNo ratings yet

- Universal Herbal or Botanical, Medical and Agricultural Containing An Account of All Known Plants in The World. 1824Document1,062 pagesUniversal Herbal or Botanical, Medical and Agricultural Containing An Account of All Known Plants in The World. 1824Guillermo BenítezNo ratings yet

- Lecture 5 Farming System Components-Cropping SystemsDocument31 pagesLecture 5 Farming System Components-Cropping SystemsTabasum BhatNo ratings yet

- Adventa India LTDDocument39 pagesAdventa India LTDkamal_jaipurNo ratings yet

- Bhendi CultivationDocument10 pagesBhendi CultivationRajkumar DurairajNo ratings yet

- 12 16Document49 pages12 16Richard Torzar0% (1)

- AGRICULTUREDocument51 pagesAGRICULTUREQueen Labado DariaganNo ratings yet

- Operational Manual For Turbo Happy Seeder: (Technology For Mana1Fnj Residues With Envlronmental Stewardship)Document37 pagesOperational Manual For Turbo Happy Seeder: (Technology For Mana1Fnj Residues With Envlronmental Stewardship)Karthic MannarNo ratings yet

- TLE HO10 w5Document4 pagesTLE HO10 w5Argonaut DrakeNo ratings yet

- Safed MusliDocument8 pagesSafed Muslimetro1cupidNo ratings yet

- VGSC221 Practical ManualDocument60 pagesVGSC221 Practical ManualSandeep GunalanNo ratings yet

- Grade 6: Elementary Agriculture Teacher'S NoteDocument32 pagesGrade 6: Elementary Agriculture Teacher'S NoteJB Mangundu100% (1)

- Afa Agri-Crop 9 q2w3Document20 pagesAfa Agri-Crop 9 q2w3angeles cilot100% (1)

- Rural agricultural work experience reportDocument84 pagesRural agricultural work experience reportsai thesis100% (1)

- Lettuce Seed Germination GuideDocument2 pagesLettuce Seed Germination GuidehyperviperNo ratings yet

- 2015-16-Minimum Rates of Wages Rates - TailoringDocument183 pages2015-16-Minimum Rates of Wages Rates - TailoringJasjit SodhiNo ratings yet

- Biofert 4 PDFDocument4 pagesBiofert 4 PDFel hanyNo ratings yet

- Acacia Mangium Ecology, Silviculture and ProductivityDocument26 pagesAcacia Mangium Ecology, Silviculture and Productivitystalin13No ratings yet

- Effects of Different Mulching Materials On The Growth Performance of Okra in MaiduguriDocument5 pagesEffects of Different Mulching Materials On The Growth Performance of Okra in MaiduguriOliver TalipNo ratings yet

- Agriculture Equipment for FarmingDocument36 pagesAgriculture Equipment for Farmingvinay muleyNo ratings yet

- Agroforestry - A Viable Option For Crop Diversification in Punjab in EnglishDocument28 pagesAgroforestry - A Viable Option For Crop Diversification in Punjab in EnglishSahil SinghNo ratings yet

- 2008 تطبيقات تقنيات المغناطيسية فى معالجة مياه الآبار المالحة لأستخدامها فى الرى تحت الظروفDocument11 pages2008 تطبيقات تقنيات المغناطيسية فى معالجة مياه الآبار المالحة لأستخدامها فى الرى تحت الظروفMUHAMMED ALSUVAİDNo ratings yet

- QF - Commercial HorticultureDocument14 pagesQF - Commercial Horticulturebepcor.orgNo ratings yet

- Growing tropical plants from seedDocument1 pageGrowing tropical plants from seedgargsanNo ratings yet