Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Integridad Cientifica 2015

Uploaded by

elisaandreacoboOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Integridad Cientifica 2015

Uploaded by

elisaandreacoboCopyright:

Available Formats

OPINION

published: 03 November 2015

doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01562

Scientific integrity in research

methods

Jordan R. Schoenherr *

Department of Psychology, Carleton University, Ottawa, ON, Canada

Keywords: scientific integrity, ethics, research methods, implicit curriculum, research misconduct

INTRODUCTION

Recent cases of research misconduct have prompted psychologists to suggest that there is too

much vulnerability in the research process (e.g., Simmons et al., 2011; Pashler and Harris, 2012).

Regardless of whether this is the case, ensuring the integrity of a discipline requires a clear

understanding of what conventions and norms define the research process. In what follows, I

consider the research integrity curriculum of North American psychology. In particular, I will

claim that a major impediment to ensuring responsible research practices is an underspecified and

understudied curriculum.

DEFINING CURRICULUM

A general distinction made in the education literature is that between the explicit curriculum and

implicit curriculum (e.g., Posner, 1992; Palomba and Banta, 1999). The explicit curriculum (EC)

consists of the information in courses, textbooks, and workshops that are formally provided to

learners. The EC contains the core concepts, norms, and values of an academic discipline. In that

Edited by: the content of the curriculum is clearly specified, the EC requires that learners achieve mastery of

Lynne D. Roberts, these theories, methods, and analytic skills. The implicit curriculum (IC) consists of the information

Curtin University, Australia that learners acquire throughout their studies that is not included in the explicit curriculum. The

Reviewed by: IC contains information that qualifies the formal curriculum such as exceptions to rules, as well as

Peter James Allen, tacit knowledge or craft skills (e.g., Polanyi, 1958; Latour and Woolgar, 1979; Charlesworth et al.,

Curtin University, Australia 1989). Craft skills can include how to select the “right” research question, how to effectively use

*Correspondence: experimental, analytic, and graphical software, and how to frame publications for acceptance. In

Jordan R. Schoenherr that the IC is ad hoc, it can be considered an apprenticeship that relies on the specific knowledge

jordan.schoenherr@carleton.ca and attention given to the learner by supervisors, mentors, and instructors.

Specialty section:

This article was submitted to

Educational Psychology,

THE STANDARDS OF PSYCHOLOGY

a section of the journal

Frontiers in Psychology Key issues in scientific integrity have been outlined by governmental and non-governmental

organizations in North America. In the United States, governmental standards have been provided

Received: 30 June 2015

by the Office of Research Integrity in terms of the responsible conduct of research (Steneck, 2006).

Accepted: 28 September 2015

Published: 03 November 2015 In Canada, major granting organizations have provided general standards that are conditions

of receiving research funds (Tri-council, 2006). University policies often extend these general

Citation:

Schoenherr JR (2015) Scientific

standards but are highly variable in terms of their content (e.g., Greene et al., 1985; Lind, 2005;

integrity in research methods. Schoenherr and Williams-Jones, 2011). For instance, while data falsification is universally agreed

Front. Psychol. 6:1562. upon as deviant behavior, publication practices are not addressed to the same extent. Explicit and

doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01562 implicit curricula are left to address these concerns.

Frontiers in Psychology | www.frontiersin.org 1 November 2015 | Volume 6 | Article 1562

Schoenherr Scientific integrity in research methods

Professional organizations such as the American features of the psychology curriculum in most academic

Psychological Association (APA) provide standards for institutions. However, whether we consider all academic

responsible research practices to their members. In addition to institutions that were sampled or solely doctoral institutions, it

the five general principles of conduct (beneficence and non- is clear that if these courses address scientific integrity issues then

maleficence, fidelity and responsibility, integrity, justice, and these issues might only be addressed in an inconsistent manner.

respect for people’s rights and dignity), the APA also identifies In a follow-up study conducted by Perlman and McCann

10 guidelines related to scientific integrity (Section 8.10a to 8.15; (2005), they also observed that courses that provide students

American Psychological Association, 2002/2010). These APA with research experience were not obligatory and that there

guidelines address the reporting of research results (fabrication was considerable interdepartmental variability in terms of when

and error correction), plagiarism, publication credit (inclusion these courses were offered. This underscores the importance of

criteria, contributions, and student credit), duplicate publication, considering degree requirements.

data sharing (post-publication and limitations), and roles and A stronger test of the scientific integrity curriculum is

responsibilities of reviewers. Whether, and how, these norms are to consider courses that are included in students’ degree

presented within the curriculum is an open question that I will requirements. In a companion analysis of the structure of

briefly consider below. degrees in psychological science, Perlman and McCann (1999b)

consider what courses were listed as degree requirements in

UNDERGRADUATE CURRICULUM 500 institutions. The majority of institutions listed capstone

(i.e., courses that require integrating knowledge of theory and

The dearth of research on issues related to scientific integrity in methods; 63%) and statistics (58%) as requirements while

psychological science can be contrasted with repeated reviews of research methods courses (40%) and experimental psychology

the psychology curriculum more generally (Henry, 1938; Sanford (38%) were required to a lesser extent. Other courses related to

and Fleishman, 1950; Daniel et al., 1965; Kulik, 1973; Lux and scientific integrity such as psychometrics (9%) and experimental

Daniel, 1978; Scheirer and Rogers, 1985; Cooney and Griffith, design (7%) were degree requirements in the minority of

1994; Perlman and McCann, 2005). For instance, Perlman and institutions. In a comparable manner to their study of courses

McCann (1999a) sampled the course catalogs of 400 institutions offered by institutions (Perlman and McCann, 1999a), Perlman

(evenly split among doctoral, comprehensive, baccalaureate, and and McCann (1999b) also note that degree requirements differed

2-year colleges) from 1961 to 1997 to examine the courses based on the type of institutions. For instance, whereas the

offered by psychology departments. Courses that are provided majority of doctoral institutions required statistics courses (65%),

across institutions provide insight into the family resemblance comprehensive (59%) and baccalaureate institutions (49%) did so

structure of the explicit scientific integrity curriculum within to a lesser extent. The variability in courses offered (Perlman and

psychological science. If scientific integrity is viewed in terms McCann, 1999a) and the extent to which they constitute degree

of appropriate conduct through the planning, implementation, requirements (Perlman and McCann, 1999b) suggest that the EC

analysis, interpretation, and communication of research findings, might only weakly addresses issues of scientific integrity.

identifying courses that likely contain this information provides Further support for curriculum variability is evidenced in

a test for how scientific integrity is presented (Ellis, 1992). the contents of research methods textbooks. Textbooks are a

Thus, courses addressing experimental design, research methods, means to present ideal disciplinary standards in terms of core

statistics, tests and measurement, as well as field experience theories and evidence (e.g., Ash, 1983; Weiten and Wight, 1992;

represent an important starting point for queries into the Zechmeister and Zechmeister, 2000). While research methods

scientific integrity curriculum (see Table 1). textbooks typically discuss issues of design (e.g., distinguishing

Perlman and McCann’s (1999a) study can be interpreted as between dependent and independent variables, participant

evidence that scientific integrity-related courses were recurrent selection, within-, or between-subjects design), scientific integrity

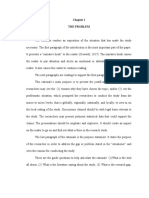

TABLE 1 | Percentage of institutions sampled by Perlman and McCann (1999a) that offer undergraduate curriculum related to scientific integrity either for

all institutions sampled (All) and the subsample of doctoral institutions (DU).

Course related to scientific integrity Year of university samples

1961 1969 1975 1997 DU 1(97–75)

All DU All DU All DU All DU

Tests and measurement 48 84 48 81 51 79 51 68 −11

Statistics 36 74 43 75 46 70 48 72 +2

Experimental 45 84 45 73 39 50 44 57 +7

Field experience – – – – 30 32 30 44 +12

Research methods – – – – 42 34 42 58 +24

Bold numbers reflect values used to obtain difference score. Difference score reflects change in course requirements from 1975 to 1997.

Frontiers in Psychology | www.frontiersin.org 2 November 2015 | Volume 6 | Article 1562

Schoenherr Scientific integrity in research methods

issues (e.g., conflict of interests, data fabrication, publication methods are alluded to in research articles or left to supervisors

practices) might not be included. Importantly, while research and mentors to explicate. As research articles are a genre

ethics is a near ubiquitous feature in research methods textbooks, and limited in the extent to which they can discuss the

these issues are restricted to the treatment of human and research process, much of the scientific integrity curriculum

non-human participants. Although, research methods textbooks is necessarily implicit. It is therefore likely to vary depending

have begun to discuss misconduct, the minority mention the on the competency and experience of faculty members,

APA guidelines that address scientific integrity. For instance, reinforcing the importance of mentorship in education in

an examination of a sample of research methods textbooks general (e.g., Bird, 2001; Paglis et al., 2006; Anderson et al.,

used at the author’s institution (e.g., Smith and Davis, 2003; 2007) and psychology in particular (e.g., Cronan-Hillix et al.,

Shaughnessy et al., 2006; McBurney and White, 2010; Cozby 1986; Clark et al., 2000; Forehand, 2008). Concerns over

and Rawn, 2012; Gravetter and Forzano, 2012; Leary, 2012) the sufficiency of this form of apprenticeship must be

revealed that no textbook included all of these guidelines and addressed.

that there is considerable variability in how many are discussed. Once apprenticeship is recognized as a central feature of

While fabrication, error correction, and plagiarism were the graduate studies, the extent to which psychologists share beliefs

most common forms of misconduct discussed, various aspects about scientific integrity becomes a central concern. However,

of publication credit and data sharing were addressed to a lesser psychologists have been found to disagree over the priority

extent. As with the EC, research methods textbooks used to of APA standards (Seitz and O’Neill, 1996; Hadjistavropoulos

support these courses do not appear to address the issues of et al., 2002) and are inconsistent in their application (Williams

scientific integrity in a comprehensive or consistent manner. This et al., 2012). Similar results have been observed for issues of

leaves the responsibility for scientific integrity education in the scientific integrity. Riordan et al. (1988) examined psychologists’

hands of individual instructors, supervisors, and mentors. perceptions of plagiarism and fabrication. They note that while

fabrication was viewed as more detrimental to a researcher’s

EARLY EXPERIENCES AND GRADUATE career, psychologists believed that university action was more

justified in cases of plagiarism. More recently, John et al. (2012)

MENTORSHIP assessed the prevalence and perceptions of questionable research

practices by psychologists. They found that the manipulation of

It might be argued that many undergraduates neither necessarily

results in an unplanned and unreported manner was a reasonably

seek, nor are considered for, graduate studies. Consequently,

common practice while also being judged to be dishonest by

evaluation of the undergraduate psychology curriculum might

psychologists.

not be the best approach to examining scientific integrity issues.

For instance, while graduate and post-graduate researchers are

concerned with research and publication, undergraduates need

not be instructed in the specific practices required to conduct

CONCLUSIONS

research. This argument reflects specious reasoning. First, higher Psychology is no more susceptible to disagreement over its norms

education is directed toward understanding a research area. than any other science (Ioannidis, 2005; De Vries et al., 2006).

Researchers must understand the basic theories, experimental Consequently, variability of the undergraduate and graduate

methods, and analytic procedures they use directly or indirectly curricula suggests that a more explicit treatment of scientific

(e.g., Schoenherr and Hamstra, 2015). This will minimally integrity issues should be pursued. Despite the possibility that

make students better consumers of scientific knowledge. Second, undergraduate statistics and research methods courses might

both socialization and expertise development require repeated address some of these issues in a general manner, other topics

use of social conventions, declarative knowledge, and technical are not likely to be addressed. This appears to be reflected in the

skill. Given graduate students’ first experience with responsible variable content of research methods textbooks. If departments

research practices occurs within the undergraduate curriculum, are unclear as to whether this is the case, tools such as curriculum

setting an early precedent is necessary. Moreover, as Lovitts matrices (e.g., Levy et al., 1999) can be used to formally evaluate

(2007) has noted in the context of the doctoral dissertation, the features of their curriculum. Curriculum matrices require

explicit conventions are often absent or not communicated that faculty members identify core topics that should be covered

to students. Michell (1997) goes further to claim that “many within a curriculum and assess which courses address this

psychological researchers are ignorant with respect to the information. When course information is plotted on such a grid,

methods they use... the ignorance I refer to is about the logic of gaps are revealed and can then be addressed. In conjunction with

methodological practices,” (p. 356). If true, this suggests graduate the standards of professional organizations, formal policies, and

school is not providing adequate instruction to develop these guidelines can also be developed to ensure greater consistency.

competencies.

A likely cause is revealed when we reflect on the experiences

of graduate students. Much graduate work is based on self- FUNDING

directed learning. While courses are offered in advanced

statistical techniques (e.g., multidimensional scaling, hierarchical This research was supported by funding from the Ottawa

linear modeling, factor analysis), other aspects of research Hospital Research Institute.

Frontiers in Psychology | www.frontiersin.org 3 November 2015 | Volume 6 | Article 1562

Schoenherr Scientific integrity in research methods

REFERENCES Lind, R. A. (2005). Evaluating research misconduct policies at major

research universities: a pilot study. Account. Res. 12, 241–262. doi:

American Psychological Association. (2002/2010). Ethical principles 10.1080/08989620500217560

of psychologists and code of conduct. Am. Psychol. 57, Lovitts, B. E. (ed.). (2007). “The psychology dissertation” in Making the Implicit

1060–1073. Explicit: Faculty’s Performance Expectations for the Dissertation (Sterling, TX:

Anderson, M. S., Horn, A. S., Risbey, K. R., Ronning, E. A., De Vries, R., and Stlyus), 247–270.

Martinson, B. C. (2007). What do mentoring and training in the responsible Lux, D. F., and Daniel, R. S. (1978). Which courses are most frequently listed by

conduct of research have to do with scientists’ misbehavior?: findings from psychology departments? Teach. Psychol. 5, 13–16.

a national survey of NIH-funded scientists. Acad. Med. 82, 853–860. doi: McBurney, D. H., and White, T. L. (2010). Research Methods, 8th Edn.

10.1097/ACM.0b013e31812f764c Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Cengage Learning.

Ash, M. G. (1983). “The self-presentation of a discipline: history of psychology Michell, J. (1997). Quantitative science and the definition of measurement

in the United States between pedagogy and scholarship,” in Functions and in psychology. Br. J. Psychol. 88, 355–383. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-

Uses of Disciplinary Histories, eds L. Graham, W. Lepenies, and P. Weingart 8295.1997.tb02641.x

(Dordrecht: Reidel), 143–189. Paglis, L. L., Green, S. G., and Bauer, T. N. (2006). Does adviser mentoring add

Bird, S. J. (2001). Mentors, advisors and supervisors: their role in teaching value? A longitudinal study of mentoring in doctoral student outcomes. Res.

responsible research conduct. Sci. Eng. Ethics 7, 455–468. doi: 10.1007/s11948- High. Educ. 47, 451–476. doi: 10.1007/s11162-005-9003-2

001-0002-1 Palomba, C., and Banta, T. (1999). Curriculum Assessment Essentials: Planning,

Charlesworth, M., Farrall, L., Stokes, T., and Turnbull, D. (1989). Life Among The Implementing & Improving Assessment in Higher Education. San Francisco, CA:

Scientists. Melbourne: Oxford University Press. Jossey-Bass.

Clark, R. A., Harden, S. L., and Johnson, W. B. (2000). Mentor Pashler, H., and Harris, C. R. (2012). Is the replicability crisis overblown?

relationships in clinical psychology doctoral training: results of a national Three arguments examined. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 7, 531–536. doi:

survey. Teach. Psychol. 27, 262–268. doi: 10.1207/S15328023TOP2 10.1177/1745691612463401

704_04 Perlman, B., and McCann, L. I. (1999a). The most frequently listed

Cooney, B. R., and Griffith, D. M. (1994). The 1992.1993 Undergraduate courses in the undergraduate psychology curriculum. Teach. Psychol. 26,

Department Survey. Washington, DC: American Psychological 177–182.

Association. Perlman, B., and McCann, L. I. (1999b). The structure of the psychology

Cozby, P. C., and Rawn, C. D. (2012). Methods in Behavioural Research, Canadian undergraduate curriculum. Teach. Psychol. 26, 171–176.

Edition. McGraw-Hill Ryerson. Perlman, B., and McCann, L. I. (2005). Undergraduate research experiences in

Cronan-Hillix, T., Gensheimer, L. K., Cronan-Hillix, W. A., and Davidson, W. Psychology: a national study of courses and curricula. Teach. Psychol. 32, 5–14.

S. (1986). Students’ views of mentors in psychology graduate training. Teach. doi: 10.1207/s15328023top3201_2

Psychol. 13, 123–127. doi: 10.1207/s15328023top1303_5 Polanyi, M. (1958). Personal Knowledge: Toward a Post-Critical Philosophy.

Daniel, R. S., Dunham, P. J., and Morris, C. J. Jr. (1965). Undergraduate courses in Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

psychology; 14 years later. Psychol. Rec. 15, 25–31. Posner, G. J. (1992). Analyzing the Curriculum. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill, Inc.

De Vries, R., Andersen, M. S., and Martinson, B. C. (2006). Normal misbehaviour: Riordan, C. A., Marlin, N. A., and Gidwani, C. (1988). Accounts offered

scientists talk about the ethics of research. J. Empir. Res. Hum. Res. Ethics 1, for unethical Research practices: effects on the evaluations of acts

43–50. doi: 10.1525/jer.2006.1.1.43 and actors. J. Soc. Psychol. 128, 495–505. doi: 10.1080/00224545.1988.

Ellis, H. C. (1992). Graduate education in psychology: past, present, and future. 9713769

Am. Psychol. 47, 570–576. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.47.4.570 Sanford, F. H., and Fleishman, E. A. (1950). A survey of undergraduate psychology

Forehand, R. L. (2008). The art and science of mentoring in psychology: a necessary courses in American colleges and universities. Am. Psychol. 5, 33–37.

practice to ensure our future. Am. Psychol. 63, 744–755. doi: 10.1037/0003- Scheirer, C. J., and Rogers, A. M. (1985). The Undergraduate Psychology

066X.63.8.744 Curriculum: 1984. Washington, DC: American Psychological

Gravetter, F. J., and Forzano, L. B. (2012). Research Methods for the Behavioral Association.

Sciences, 4th Edn. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Cengage Learning. Schoenherr, J. R., and Hamstra, S. J. (2015). Psychometrics and its discontents: a

Greene, P. J., Durch, J. S., Horwitz, W., and Hooper, V. (1985). Policies for historical perspective on the discourse of the measurement tradition. Advan.

responding to allegations of fraud in research. Minerva 23, 203–215. doi: Health Sci. Educ. doi: 10.1007/s10459-015-9623-z. [Epub ahead of print].

10.1007/BF01099942 Schoenherr, J., and Williams-Jones, B. (2011). Research integrity/misconduct

Hadjistavropoulos, T., Malloy, D. C., Sharpe, D., Green, S. M., and Fuchs- policies of Canadian universities. Can. J. High. Educ. 41, 1–17.

Lacelle, S. (2002). The relative importance of the ethical principles adopted Seitz, J., and O’Neill, P. (1996). Ethical decision-making and the code of ethics

by the American Psychological Association. Can. Psychol. 43, 254–259. doi: of the Canadian Psychological Association. Can. Psychol. 37, 21–30. doi:

10.1037/h0086921 10.1037/0708-5591.37.1.23

Henry, E. R. (1938). A survey of courses in psychology offered by undergraduate Shaughnessy, J. J., Zechmeister, E. B., and Zechmeister, J. S. (2006). Research

colleges of liberal arts. Psychol. Bullet. 35, 430–435. doi: 10.1037/h00 Methods in Psychology, 7th Edn. New York, NY: McGrawHill.

59009 Simmons, J. P., Nelson, L. D., and Simonsohn, U. (2011). False-positive

Ioannidis, J. P. A. (2005). Why most published research findings are false. PLoS psychology: undisclosed flexibility in data collection and analysis allows

Med. 2:e124. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0020124 presenting anything as significant. Psychol. Sci. 22, 1359–1366. doi:

John, L. K., Loewenstein, G., and Prelec, D. (2012). Measuring the prevalence of 10.1177/0956797611417632

questionable research practices with incentives for truth telling. Psychol. Sci. 23, Smith, R. A., and Davis, S. F. (2003). The Psychologist as Detective, 3rd Edn.

524–532. doi: 10.1177/0956797611430953 Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall.

Kulik, J. A. (1973). Undergraduate Education in Psychology. Washington, DC: Steneck, N. (2006). Fostering integrity in research: definitions, current knowledge,

American Psychological Association. and future directions. Sci. Eng. Ethics 12, 53–74. doi: 10.1007/s11948-006-

Latour, B., and Woolgar, S. (1979). Laboratory Life: The Construction of Scientific 0006-y

Facts. Princeton: Princeton University Press. Tri-council. (2006). Tri-Council Policy Statement: Integrity in Research and

Leary, M. R. (2012). Introduction to Behavioral Research Methods, 6th Edn. Scholarship. Available online at: http://www.nserc.gc.ca/professors_e.asp?nav=

New York, NY: Pearson. profnav&lbi=p9

Levy, J., Burton, G., Mickler, S., and Vigorito, M. (1999). A curriculum matrix for Weiten, W., and Wight, R. D. (1992). “Portraits of a discipline: an examination

psychology program review. Teach. Psychol. 26, 291–294. of introductory psychology textbooks in America,” in Teaching Psychology

Frontiers in Psychology | www.frontiersin.org 4 November 2015 | Volume 6 | Article 1562

Schoenherr Scientific integrity in research methods

in America: A History, eds A. E. Puente, J. R. Matthews, and C. L. Brewer Conflict of Interest Statement: The author declares that the research was

(Washington, DC: American Psychological Association), 453–504. conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could

Williams, J., Hadjistavropoulos, T., Malloy, D. C., Gagnon, M., Sharpe, D., and be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Fuchs-Lacelle, S. (2012). A mixed methods investigation of the effects of

ranking ethical principles on decision making: implications for the canadian Copyright © 2015 Schoenherr. This is an open-access article distributed under the

code of ethics for psychologists. Can. Psychol. 53, 204–216. doi: 10.1037/a00 terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or

27624 reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor

Zechmeister, J. S., and Zechmeister, E. B. (2000). Introductory textbooks are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance

and psychology’s core concepts. Teach. Psychol. 27, 6–11. doi: with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted

10.1207/S15328023TOP2701_1 which does not comply with these terms.

Frontiers in Psychology | www.frontiersin.org 5 November 2015 | Volume 6 | Article 1562

You might also like

- Choosing a Research Method, Scientific Inquiry:: Complete Process with Qualitative & Quantitative Design ExamplesFrom EverandChoosing a Research Method, Scientific Inquiry:: Complete Process with Qualitative & Quantitative Design ExamplesNo ratings yet

- Standards From AERADocument8 pagesStandards From AERAJoon AlpineNo ratings yet

- Integrating Critical Thinking Into The CurriculumDocument9 pagesIntegrating Critical Thinking Into The Curriculumapi-276941568No ratings yet

- Tang Research Ethics CourseDocument17 pagesTang Research Ethics CourseIonCotrutaNo ratings yet

- Research Philosophy and Annotated CV - Submitted-2018-01-25t15 - 39 - 05.503ZDocument31 pagesResearch Philosophy and Annotated CV - Submitted-2018-01-25t15 - 39 - 05.503Zahsan nizamiNo ratings yet

- Presenting The Research ProblemDocument59 pagesPresenting The Research ProblemthinagaranNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2 - Group 1 - Literature Review Framework Theory and Etc.Document12 pagesChapter 2 - Group 1 - Literature Review Framework Theory and Etc.Aikie KunnNo ratings yet

- PR1 NatureDocument57 pagesPR1 NaturenanaNo ratings yet

- Santos, Nerissa - Final Exam Quanti ResearchDocument8 pagesSantos, Nerissa - Final Exam Quanti ResearchNerissa SantosNo ratings yet

- 12ERv35n6 Standard4ReportDocument8 pages12ERv35n6 Standard4ReportMaca ConsumistaNo ratings yet

- Criteria For Qualitative Research in PsychologyDocument13 pagesCriteria For Qualitative Research in PsychologyRoberto Garcia Jr.No ratings yet

- The Scientifically Minded Psychologist Science As A Core CompetencyDocument11 pagesThe Scientifically Minded Psychologist Science As A Core CompetencyPaula Manalo-SuliguinNo ratings yet

- The Internal Audit As Tool To Enhance The Quality of Qualitative ResearchDocument15 pagesThe Internal Audit As Tool To Enhance The Quality of Qualitative ResearchEvantheNo ratings yet

- Chism Douglas Hilson Qualitative Research Basics A Guide For Engineering EducatorsDocument69 pagesChism Douglas Hilson Qualitative Research Basics A Guide For Engineering EducatorsVictorNo ratings yet

- AERA - Standards1Document8 pagesAERA - Standards120041434 Lê Thanh LoanNo ratings yet

- 2019 Article 898Document9 pages2019 Article 898SM199021No ratings yet

- Criteria For Qualitative Research in PsychologyDocument13 pagesCriteria For Qualitative Research in PsychologyPaula Andrea Rodriguez AbrilNo ratings yet

- Measuring Scientific Reasoning A Review of Test InstrumentsDocument25 pagesMeasuring Scientific Reasoning A Review of Test InstrumentsDevi MonicaNo ratings yet

- Thesis Guide Proposal GIGIDocument47 pagesThesis Guide Proposal GIGImaria erika100% (5)

- Research Ethics in Dissertations: Ethical Issues and Complexity of ReasoningDocument8 pagesResearch Ethics in Dissertations: Ethical Issues and Complexity of ReasoningDamian CarlaNo ratings yet

- Elliott Fischer Rennie 1999Document15 pagesElliott Fischer Rennie 1999pranabdahalNo ratings yet

- Original PDF Research Methods in Psychology Evaluating A World of Information 3rd Edition PDFDocument42 pagesOriginal PDF Research Methods in Psychology Evaluating A World of Information 3rd Edition PDFlynn.vaughan848100% (33)

- Actions and Techniques in Supervision, Mentorships and Tutorial Activities To Foster Doctoral Study Success: A Scoping Literature ReviewDocument11 pagesActions and Techniques in Supervision, Mentorships and Tutorial Activities To Foster Doctoral Study Success: A Scoping Literature ReviewIRFANNo ratings yet

- JSS Hughes Davis Imenda2019Document13 pagesJSS Hughes Davis Imenda2019John Raizen Grutas CelestinoNo ratings yet

- Szostak, R. The Intersdispnarity Research ProcessDocument18 pagesSzostak, R. The Intersdispnarity Research ProcessAntara AdachiNo ratings yet

- Research MethodologyDocument33 pagesResearch MethodologyFelisberto BilaNo ratings yet

- Rigor in Qualitative Research: Rigor and Quality CriteriaDocument9 pagesRigor in Qualitative Research: Rigor and Quality CriteriaRanda NorayNo ratings yet

- Qualitative Research in Counseling Psychology A PRDocument12 pagesQualitative Research in Counseling Psychology A PRAayushi PillaiNo ratings yet

- Advances in Health Sciences Education: Standards For An Acceptable ManuscriptDocument14 pagesAdvances in Health Sciences Education: Standards For An Acceptable ManuscriptRiry AmbarsaryNo ratings yet

- Nature and Hows of ResearchDocument79 pagesNature and Hows of ResearchLennie DiazNo ratings yet

- 1994 Kvale-Ten Standard Objections To Qualitative InterviewsDocument27 pages1994 Kvale-Ten Standard Objections To Qualitative Interviewsshadow-aicleNo ratings yet

- Qualitative Research Synthesis and ReflectionDocument20 pagesQualitative Research Synthesis and ReflectionDun SusuNo ratings yet

- IMRAD Guidelines On How To Craft Chapter 1 5Document14 pagesIMRAD Guidelines On How To Craft Chapter 1 5Cupcake BabeNo ratings yet

- Ponterroto (2005) Qualitative Research in Counseling Psychology - A Primer On Research Paradigms and Philosophy of Science (1) - 1Document11 pagesPonterroto (2005) Qualitative Research in Counseling Psychology - A Primer On Research Paradigms and Philosophy of Science (1) - 1Brigette Lee BorromeNo ratings yet

- Grounding Knowledge and Normative Valuat PDFDocument26 pagesGrounding Knowledge and Normative Valuat PDFIlijaNo ratings yet

- Integrating Formative Assessment and Feedback Into Scientific Theory Building Practices and InstructionDocument18 pagesIntegrating Formative Assessment and Feedback Into Scientific Theory Building Practices and InstructionMaria GuNo ratings yet

- Clase 1 - Qualitative Research in Psychology Ian ParkerDocument13 pagesClase 1 - Qualitative Research in Psychology Ian ParkerIan AguayoNo ratings yet

- Research Proposal Sample OutlineDocument17 pagesResearch Proposal Sample OutlineGuidance and Counseling OfficeNo ratings yet

- Durham Research OnlineDocument37 pagesDurham Research OnlineBibek KandelNo ratings yet

- Theoretical and Conceptual Framework 1Document7 pagesTheoretical and Conceptual Framework 1MERCY ABOCNo ratings yet

- Honesty in Critically Re Ective Essays: An Analysis of Student PracticeDocument11 pagesHonesty in Critically Re Ective Essays: An Analysis of Student PracticeniravNo ratings yet

- Lecture 3 Research Problem, Question, PurposeDocument40 pagesLecture 3 Research Problem, Question, Purposesinuaish syaNo ratings yet

- Hanson Qualitative Research Methods For Medical Educators AcadPediatr 2011Document12 pagesHanson Qualitative Research Methods For Medical Educators AcadPediatr 2011hdh44vgcmdNo ratings yet

- PR 1.1 What Is ResearchDocument9 pagesPR 1.1 What Is ResearchAizel Joyce DomingoNo ratings yet

- Module The Research Proposal PDFDocument14 pagesModule The Research Proposal PDFmalinda100% (1)

- Interdisciplinary Research Process and Theory (Allen F. Repko Richard (Rick) Szostak) (Z-Library)Document727 pagesInterdisciplinary Research Process and Theory (Allen F. Repko Richard (Rick) Szostak) (Z-Library)Hảo Nguyễn Thị100% (1)

- Malterud-2001-Qualitative Research - Standards, Challenges, and Guidelines PDFDocument6 pagesMalterud-2001-Qualitative Research - Standards, Challenges, and Guidelines PDFJeronimo SantosNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2Document24 pagesChapter 2bamalambNo ratings yet

- Qualitative Research Methods For Medical Educators. - 2011Document12 pagesQualitative Research Methods For Medical Educators. - 2011shodhgangaNo ratings yet

- Practice: Critically Appraising Qualitative ResearchDocument6 pagesPractice: Critically Appraising Qualitative ResearchNurma DiahNo ratings yet

- Embarking On Research in The Social Sciences: Understanding The Foundational ConceptsDocument15 pagesEmbarking On Research in The Social Sciences: Understanding The Foundational ConceptsPhạm Quang ThiênNo ratings yet

- Guidelines On How To Craft Chapter 1 5Document26 pagesGuidelines On How To Craft Chapter 1 5Madison Azalea Donatelli HernandezNo ratings yet

- 1 PBDocument17 pages1 PBAntenehNo ratings yet

- Methods of Research ReviewerDocument10 pagesMethods of Research ReviewerCorazon R. LabasanoNo ratings yet

- Module 07 - Conceptual FrameworkDocument18 pagesModule 07 - Conceptual FrameworksunnyNo ratings yet

- Arm Module 6Document5 pagesArm Module 6Angela Tibagacay CaballeroNo ratings yet

- Thesis For Critical Evaluation EssayDocument9 pagesThesis For Critical Evaluation Essayelizabethtemburubellevue100% (2)

- Integrity in Qualitative ResearchDocument12 pagesIntegrity in Qualitative ResearchScott OstrowNo ratings yet

- Resonance UnlockedDocument5 pagesResonance UnlockedgjjgNo ratings yet

- Issue: 3D at Depth: The Future Is GreenDocument72 pagesIssue: 3D at Depth: The Future Is GreenPepeNo ratings yet

- م م م م م م م م Kkkk אلد אلد אلد אلد א א א א Llll دאوאدא دאوאدא دאوאدא دאوאدאDocument47 pagesم م م م م م م م Kkkk אلد אلد אلد אلد א א א א Llll دאوאدא دאوאدא دאوאدא دאوאدאYoucef kahlrsNo ratings yet

- PB Arang Aktif 11032020 BDocument2 pagesPB Arang Aktif 11032020 BSiti Sarifa YusuffNo ratings yet

- 4.4.1.4 DLL - ENGLISH-6 - Q4 - W4.docx Version 1Document13 pages4.4.1.4 DLL - ENGLISH-6 - Q4 - W4.docx Version 1Gie Escoto Ocampo100% (1)

- Zero Gravity ManufacturingDocument17 pagesZero Gravity Manufacturingsunny sunnyNo ratings yet

- Third Generation D.O. Probes: Oxyguard Quick Guide Do ProbesDocument1 pageThird Generation D.O. Probes: Oxyguard Quick Guide Do ProbesGregorio JofréNo ratings yet

- KepemimpinanDocument11 pagesKepemimpinanAditio PratamNo ratings yet

- Living in A Dream WorldDocument8 pagesLiving in A Dream WorldTrọng Nguyễn DuyNo ratings yet

- Engineering Maths 4 SyllabusDocument3 pagesEngineering Maths 4 SyllabusRanjan NayakNo ratings yet

- Conflicted City: Hypergrowth, Urban Renewal and Urbanization in IstanbulDocument45 pagesConflicted City: Hypergrowth, Urban Renewal and Urbanization in IstanbulElif Simge FettahoğluNo ratings yet

- Partial Blockage Detection in Underground Pipe Based On Guided Wave&semi-Supervised LearningDocument3 pagesPartial Blockage Detection in Underground Pipe Based On Guided Wave&semi-Supervised Learningrakesh cNo ratings yet

- N3001 Replacement Procedures-Rev 1.40Document212 pagesN3001 Replacement Procedures-Rev 1.40Anthony mcNo ratings yet

- New Challenge in Tap Hole Practices at H Blast Furnace Tata Steel. FinalDocument9 pagesNew Challenge in Tap Hole Practices at H Blast Furnace Tata Steel. FinalSaumit Pal100% (1)

- 1969 Book InternationalCompendiumOfNumerDocument316 pages1969 Book InternationalCompendiumOfNumerRemigiusz DąbrowskiNo ratings yet

- Mark Scheme (Results) January 2020: Pearson Edexcel International GCSE in Physics (4PH1) Paper 2PDocument12 pagesMark Scheme (Results) January 2020: Pearson Edexcel International GCSE in Physics (4PH1) Paper 2PNairit80% (5)

- Lecture Notes. Mathematics in The Modern WorldDocument4 pagesLecture Notes. Mathematics in The Modern WorldEmmanuelle Kate Magpayo - 1ANo ratings yet

- On NCVET FunctioningDocument35 pagesOn NCVET Functioningsingh.darshan9100% (2)

- Nearly Complete Spray Cap List .Document8 pagesNearly Complete Spray Cap List .Жиганов Володимир Андрійович 1АКІТ 18-БNo ratings yet

- Pas 8811 2017Document42 pagesPas 8811 2017Mohammed HafizNo ratings yet

- 2 VCA ETT 2017 Training v2 0 - EnglishDocument129 pages2 VCA ETT 2017 Training v2 0 - EnglishMassimo FumarolaNo ratings yet

- Document 1-DoneDocument12 pagesDocument 1-DoneDee GeneliaNo ratings yet

- Contoh Sterilefiltration Pada Viral Vaccine Live AtenuatedDocument10 pagesContoh Sterilefiltration Pada Viral Vaccine Live Atenuatedkomang inggasNo ratings yet

- SK Pradhan ObituaryDocument1 pageSK Pradhan Obituarysunil_vaman_joshiNo ratings yet

- Chilling & Freezing: Dr. Tanya Luva SwerDocument35 pagesChilling & Freezing: Dr. Tanya Luva SwerPratyusha DNo ratings yet

- Pump LossesDocument15 pagesPump LossesMuhammad afzal100% (1)

- (Discontinued ) : ASTM A353 Alloy SteelDocument1 page(Discontinued ) : ASTM A353 Alloy SteelDhanyajaNo ratings yet

- Crack The Millionaire CodeDocument32 pagesCrack The Millionaire Coderusst2100% (1)

- EMCO F1 ManualDocument308 pagesEMCO F1 ManualClinton Koo100% (1)

- Some Books For Stat 602XDocument1 pageSome Books For Stat 602XAmit SharmaNo ratings yet

- Love Life: How to Raise Your Standards, Find Your Person, and Live Happily (No Matter What)From EverandLove Life: How to Raise Your Standards, Find Your Person, and Live Happily (No Matter What)Rating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (1)

- ADHD is Awesome: A Guide to (Mostly) Thriving with ADHDFrom EverandADHD is Awesome: A Guide to (Mostly) Thriving with ADHDRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (3)

- The Age of Magical Overthinking: Notes on Modern IrrationalityFrom EverandThe Age of Magical Overthinking: Notes on Modern IrrationalityRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (30)

- LIT: Life Ignition Tools: Use Nature's Playbook to Energize Your Brain, Spark Ideas, and Ignite ActionFrom EverandLIT: Life Ignition Tools: Use Nature's Playbook to Energize Your Brain, Spark Ideas, and Ignite ActionRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (404)

- Raising Good Humans: A Mindful Guide to Breaking the Cycle of Reactive Parenting and Raising Kind, Confident KidsFrom EverandRaising Good Humans: A Mindful Guide to Breaking the Cycle of Reactive Parenting and Raising Kind, Confident KidsRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (170)

- By the Time You Read This: The Space between Cheslie's Smile and Mental Illness—Her Story in Her Own WordsFrom EverandBy the Time You Read This: The Space between Cheslie's Smile and Mental Illness—Her Story in Her Own WordsNo ratings yet

- The Ritual Effect: From Habit to Ritual, Harness the Surprising Power of Everyday ActionsFrom EverandThe Ritual Effect: From Habit to Ritual, Harness the Surprising Power of Everyday ActionsRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (4)

- The Body Keeps the Score by Bessel Van der Kolk, M.D. - Book Summary: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of TraumaFrom EverandThe Body Keeps the Score by Bessel Van der Kolk, M.D. - Book Summary: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of TraumaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Raising Mentally Strong Kids: How to Combine the Power of Neuroscience with Love and Logic to Grow Confident, Kind, Responsible, and Resilient Children and Young AdultsFrom EverandRaising Mentally Strong Kids: How to Combine the Power of Neuroscience with Love and Logic to Grow Confident, Kind, Responsible, and Resilient Children and Young AdultsRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Summary: The Psychology of Money: Timeless Lessons on Wealth, Greed, and Happiness by Morgan Housel: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedFrom EverandSummary: The Psychology of Money: Timeless Lessons on Wealth, Greed, and Happiness by Morgan Housel: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (81)

- Think This, Not That: 12 Mindshifts to Breakthrough Limiting Beliefs and Become Who You Were Born to BeFrom EverandThink This, Not That: 12 Mindshifts to Breakthrough Limiting Beliefs and Become Who You Were Born to BeRating: 2 out of 5 stars2/5 (1)

- The Marshmallow Test: Mastering Self-ControlFrom EverandThe Marshmallow Test: Mastering Self-ControlRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (59)

- Manipulation: The Ultimate Guide To Influence People with Persuasion, Mind Control and NLP With Highly Effective Manipulation TechniquesFrom EverandManipulation: The Ultimate Guide To Influence People with Persuasion, Mind Control and NLP With Highly Effective Manipulation TechniquesRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (1412)

- Cult, A Love Story: Ten Years Inside a Canadian Cult and the Subsequent Long Road of RecoveryFrom EverandCult, A Love Story: Ten Years Inside a Canadian Cult and the Subsequent Long Road of RecoveryRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Why We Die: The New Science of Aging and the Quest for ImmortalityFrom EverandWhy We Die: The New Science of Aging and the Quest for ImmortalityRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5)

- Summary: Thinking, Fast and Slow: by Daniel Kahneman: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedFrom EverandSummary: Thinking, Fast and Slow: by Daniel Kahneman: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (61)

- Dark Psychology & Manipulation: Discover How To Analyze People and Master Human Behaviour Using Emotional Influence Techniques, Body Language Secrets, Covert NLP, Speed Reading, and Hypnosis.From EverandDark Psychology & Manipulation: Discover How To Analyze People and Master Human Behaviour Using Emotional Influence Techniques, Body Language Secrets, Covert NLP, Speed Reading, and Hypnosis.Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (110)

- Troubled: The Failed Promise of America’s Behavioral Treatment ProgramsFrom EverandTroubled: The Failed Promise of America’s Behavioral Treatment ProgramsRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (2)

- Mindset by Carol S. Dweck - Book Summary: The New Psychology of SuccessFrom EverandMindset by Carol S. Dweck - Book Summary: The New Psychology of SuccessRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (328)

- The Secret of the Golden Flower: A Chinese Book Of LifeFrom EverandThe Secret of the Golden Flower: A Chinese Book Of LifeRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (4)

- Summary: Limitless: Upgrade Your Brain, Learn Anything Faster, and Unlock Your Exceptional Life By Jim Kwik: Key Takeaways, Summary and AnalysisFrom EverandSummary: Limitless: Upgrade Your Brain, Learn Anything Faster, and Unlock Your Exceptional Life By Jim Kwik: Key Takeaways, Summary and AnalysisRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (8)

- Empath: The Survival Guide For Highly Sensitive People: Protect Yourself From Narcissists & Toxic Relationships. Discover How to Stop Absorbing Other People's PainFrom EverandEmpath: The Survival Guide For Highly Sensitive People: Protect Yourself From Narcissists & Toxic Relationships. Discover How to Stop Absorbing Other People's PainRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (95)

- The Garden Within: Where the War with Your Emotions Ends and Your Most Powerful Life BeginsFrom EverandThe Garden Within: Where the War with Your Emotions Ends and Your Most Powerful Life BeginsNo ratings yet

- The Courage Habit: How to Accept Your Fears, Release the Past, and Live Your Courageous LifeFrom EverandThe Courage Habit: How to Accept Your Fears, Release the Past, and Live Your Courageous LifeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (253)

- Outlive: The Science and Art of Longevity by Peter Attia: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisFrom EverandOutlive: The Science and Art of Longevity by Peter Attia: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- When the Body Says No by Gabor Maté: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisFrom EverandWhen the Body Says No by Gabor Maté: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2)