Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Global Burden of Cancers

Uploaded by

MartinaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Global Burden of Cancers

Uploaded by

MartinaCopyright:

Available Formats

Articles

Global burden of cancers attributable to infections in 2012:

a synthetic analysis

Martyn Plummer*, Catherine de Martel*, Jerome Vignat, Jacques Ferlay, Freddie Bray, Silvia Franceschi

Summary

Background Infections with certain viruses, bacteria, and parasites are strong risk factors for specific cancers. As new Lancet Glob Health 2016;

cancer statistics and epidemiological findings have accumulated in the past 5 years, we aimed to assess the causal 4: e609–16

involvement of the main carcinogenic agents in different cancer types for the year 2012. Published Online

July 25, 2016

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/

Methods We considered ten infectious agents classified as carcinogenic to human beings by the International Agency S2214-109X(16)30143-7

for Research on Cancer. We calculated the number of new cancer cases in 2012 attributable to infections by country, See Comment page e580

by combining cancer incidence estimates (from GLOBOCAN 2012) with estimates of attributable fraction (AF) for the *Contributed equally

infectious agents. AF estimates were calculated from the prevalence of infection in cancer cases and the relative risk

International Agency for

for the infection (for some sites). Estimates of infection prevalence, relative risk, and corresponding 95% CIs for AF Research on Cancer,

were obtained from systematic reviews and pooled analyses. 69372 Lyon Cedex 08, France

(M Plummer PhD,

C de Martel MD, J Vignat MSc,

Findings Of 14 million new cancer cases in 2012, 2·2 million (15·4%) were attributable to carcinogenic infections. The J Ferlay ME, F Bray PhD,

most important infectious agents worldwide were Helicobacter pylori (770 000 cases), human papillomavirus (640 000), S Franceschi MD)

hepatitis B virus (420 000), hepatitis C virus (170 000), and Epstein-Barr virus (120 000). Kaposi’s sarcoma was the Correspondence to:

second largest contributor to the cancer burden in sub-Saharan Africa. The AFs for infection varied by country and Dr Martyn Plummer,

development status—from less than 5% in the USA, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and some countries in western International Agency for

Research on Cancer,

and northern Europe to more than 50% in some countries in sub-Saharan Africa.

69372 Lyon Cedex 08, France

plummerm@iarc.fr

Interpretation A large potential exists for reducing the burden of cancer caused by infections. Socioeconomic

development is associated with a decrease in infection-associated cancers; however, to reduce the incidence of these

cancers without delay, population-based vaccination and screen-and-treat programmes should be made accessible

and available.

Funding Fondation de France.

Copyright © The Author(s). Published by Elsevier Ltd. This is an Open Access article under the CC BY-NC-ND license.

Introduction (HPV; types 16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58, and

Carcinogenic infections are an important cause of cancer, 59—known collectively as high-risk types), Epstein-Barr

particularly in less developed countries. Their virus (EBV), human herpesvirus type 8 (HHV-8; also

contribution to the global burden of cancer has been known as Kaposi’s sarcoma herpesvirus), human T-cell

periodically assessed in a series of publications for 1990, lymphotropic virus type 1 (HTLV-1), Opisthorchis viverrini,

2002, and 2008.1–3 In 2008, 16·1% of all cancers worldwide Clonorchis sinensis, and Schistosoma haematobium.5 Among

were estimated to be attributable to infections, with these agents, HIV is unique in attributable risk

substantial variation between geographical regions from calculations because, at the best of current knowledge,

3·3% in Australia to 32·7% in sub-Saharan Africa.1 Here, HIV has been shown to increase cancer risk only in

we update these statistics for the year 2012 using combination with other carcinogenic infectious agents;5

estimates of global cancer incidence from GLOBOCAN therefore, we chose to attribute cancers in HIV-positive

20124 and new estimates of population attributable people to the co-infection. In 2015, we estimated that in

fractions, hereafter referred to as attributable fractions the combined antiretroviral therapy era, 40% of cancers

(AFs), for infectious agents derived from a review of occurring in HIV-positive people in the USA are

reports published in the past 20 years. attributable to infections.6 However, essential information

on the number of HIV-infected individuals and cancer

Methods incidence among them is lacking in most countries.

Infectious agents Consistent with our previous report,1 we could not

11 infectious agents have been classified as well established accurately estimate the contribution of HIV to the fraction

(group 1) carcinogenic agents in human beings by the of infection-attributable cancers.

International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC): Therefore, we considered the ten infectious agents other

Helicobacter pylori, hepatitis B virus (HBV), hepatitis C than HIV and the associated cancer types (table 1). A few

virus (HCV), HIV type 1 (HIV-1), human papillomavirus cancer types or subtypes were added to those established

www.thelancet.com/lancetgh Vol 4 September 2016 e609

Articles

Research in context

Evidence before this study improving on the previous report by using the most recent

Evidence on the association between infection and cancer was data and giving more details of individual country estimates

comprehensively reviewed by an expert working group of the and analysis by level of socioeconomic development. The

International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) in 2009. On fraction of all cancers attributable to infection varies greatly

the basis of these expert reviews, we published estimates of the between countries, with an important negative association

global burden of cancer due to infection for the year 2008. To between population attributable fraction and level of

estimate the strength of the associations between specific socioeconomic development. Despite this association, some

infection and cancer types in terms of population attributable highly developed countries continue to show a large burden of

fraction, we used published meta-analyses where possible and did infection-attributable cancer because of the long interval

our own systematic reviews when necessary. Since then, new between infection acquisition and cancer development.

cancer incidence estimates have become available from

Implications of all the available evidence

GLOBOCAN for the year 2012 and from many new epidemiological

The global burden of infection-attributable cancer is mainly on

studies, including better evidence on the involvement of human

less developed countries. To reduce this burden, vaccination or

papillomavirus in cancers of the head and neck and Helicobacter

screening programmes used in more developed countries

pylori in gastric cancer, notably gastric cardia cancer.

should become more widely available.

Added value of this study

In this study, we synthesised the available data to present an

updated picture of cancer and infection burden worldwide,

by an expert working group convened by the IARC.5 In very high HDI.12 We also created a dichotomous HDI

high-risk areas for H pylori infection and gastric cancer in classification by combining countries with low and

east Asia, evidence shows that a subset of cancers of the medium HDI into less developed countries, and

gastric cardia arise from severe atrophic gastritis due to countries with high and very high HDI into more

H pylori along a pathway similar to that of non-cardia developed countries. In some instances, China was

gastric cancer.7 Additionally, recent case series8,9 that used shown separately from other medium-HDI countries

detection of viral oncoproteins E6 and E7 (ie, PCR with E6 because of the large size of its population and cancer

or E7 mRNA, the gold standard for detecting the presence burden (accounting for 3·1 million [60%] of the

of actively transcribing virus in cancer tissues) now allow 5·2 million cancer cases in medium-HDI countries)4 and

the attribution of a small proportion of cancers of the oral because changes in HDI methodology have classified

cavity and larynx to HPV. Other methodological changes China as a high-HDI country since 2014.13

from the previous reports included updating of the fraction

of non-cardia gastric cancer attributable to H pylori using Statistical analysis

data from immunoblot, a more sensitive method than The AF for carcinogenic infections is the proportion of

ELISA in the detection of H pylori infection.10 We also used new cancer cases that would have been prevented in a

data from a meta-analysis of the worldwide distribution of population if all infections had been avoided or

HBV and HCV in hepatocellular carcinoma11 to obtain successfully treated before they caused cancer. Briefly, for

improved and separate estimates of liver cancer attributable HPV in cervical cancer, HTLV-1 in adult T-cell leukaemia

to the two viruses. and lymphoma, and HHV-8 in Kaposi’s sarcoma, 100% of

See Online for appendix cancers are attributed to the infection (table 1; see appendix

Geographical areas for detailed methods).5 For HPV at other cancer sites and

Using data from GLOBOCAN 2012,4 we estimated the EBV-related cancers, the prevalence of viral transcripts in

number of new cancer cases due to infections by country tumour cells in cases from case series and case-control

and then aggregated these estimates into eight studies was used to estimate the AF. For H pylori, HBV,

geographical regions based on the UN classification: sub- and HCV, AF estimates were based on the prevalence in

Saharan Africa, north Africa and west Asia, central Asia, cases adjusted by the relative risk as previously described.1

east Asia, Latin America, North America, Europe, and For rare cancers caused by parasites in endemic areas,

Oceania.1 We also aggregated results by the 2012 Human specific methods were used as before,1 because of the

Development Index (HDI),12 a composite indicator of life dearth of available data (appendix).

expectancy, education, and gross domestic product per We derived 95% CIs for the AF estimates from random-

person. 187 countries were divided by quartiles of HDI effects meta-analysis of infection prevalence in case series

distribution into four groups, each with an equal number (HPV and EBV). When the AF also depended on relative

of countries (although with substantially different risk estimates (ie, for H pylori, HBV, and HCV), the

population sizes) and labelled as low, medium, high, and 95% CI accounted for the uncertainty in both prevalence

e610 www.thelancet.com/lancetgh Vol 4 September 2016

Articles

Type of studies used for AF Laboratory method Population and AF (95% CI)

estimation

Helicobacter pylori*

Non-cardia gastric carcinoma† (C16.1–9) Cohort Immunoblot World: 89% (79–94)

Gastric cardia carcinoma† (C16.0) Cohort ELISA East Asia: 29% (10–45)

Gastric non-Hodgkin lymphoma† (C82–85, C96) Cohort and case-control ELISA World: 74% (43–86)

Hepatitis B virus*

Liver cancer (C22) Cohort, case-control, and case series HBsAg World: NS‡

Hepatitis C virus*

Liver cancer (C22) Cohort, case-control, and case series ELISA (second or third generation) World: NS‡

Non-Hodgkin lymphomas† (C82–85, C96) Cohort and case-control ELISA (second or third generation) Low-risk countries: 1·7% (1·5–2·1)

High-risk countries: 9·8% (8·2–12·0)

Egypt: 24% (20–28)

HPV (high-risk types)§

Cervix uteri carcinoma (C53) Case-control DNA PCR World: 100%

Penile carcinoma† (C60) Case-control DNA PCR World: 51% (47–55)

Anal carcinoma† (C21) Case-control DNA PCR with p16INK4A World: 88% (85–91)

Vulvar carcinoma† (C51) Case-control DNA PCR with p16INK4A Age 15–54 years: 48% (42–54)

Age 55–64 years: 28% (23–33)

Age ≥65 years: 15% (11–18)

Vaginal carcinoma† (C52) Case-control DNA PCR World: 78% (68–86)

Carcinoma of the oropharynx, including tonsils Case-control PCR for DNA and HPV E6/E7 mRNA expression North America: 51% (41–57)

and base of tongue† (C01, C09–10) Northwest Europe: 42% (34–47)

East Europe: 50% (39–57)

South Europe: 24% (17–30)

China: 23% (17–27)

Japan: 46% (39–59)

India: 22% (5–44)

South Korea: 60% (46–70)

Australia: 41% (32–47)

Elsewhere: 13% (5–23)

Cancer of the oral cavity† (C02–06) Case-control PCR for DNA and HPV E6/E7 mRNA expression World: 4·3% (3·2–5·7)

Laryngeal cancer (C32) Case-control PCR for DNA and HPV E6/E7 mRNA expression World: 4·6% (3·3–6·1)

EBV§

Hodgkin’s lymphoma (C81) Cohort and case-control In-situ hybridisation of EBV-encoded small RNAs and Africa: 74% (65–82)

EBV latent membrane protein 1 Latin America: 60% (54–67)

Asia: 56% (52–60)

Europe: 36% (32–39)

North America: 32% (25–39)

Australia: 29% (10–58)

Burkitt’s lymphoma† (C83.7) Case-control and case series In-situ hybridisation of EBV-encoded small RNAs and Sub-Saharan Africa: 100%

Epstein-Barr nuclear antigen 4 USA and Europe: 20%

Elsewhere: 30%

Nasopharyngeal carcinoma (C11) Case-control and case series In-situ hybridisation of EBV-encoded small RNAs High-incidence countries: 100%

Low-incidence countries: 80%

Human herpesvirus type 8§

Kaposi’s sarcoma (C46) Not applicable DNA PCR World: 100%

Human T-cell lymphotropic virus*

Adult T-cell leukaemia and lymphoma† (C91.5) Not applicable Immunoblot World: 100%

Opisthorchis viverrini and Clonorchis sinensis

Bile duct cancer† (C22.1) Case-control Various Endemic areas in southeast Asia: NA¶

Schistosoma haematobium

Bladder carcinoma (C67) Case-control Various Endemic areas in Africa: 41% (36–48)

AF=attributable fraction. HPV=human papillomavirus. EBV=Epstein-Barr virus. *In sera. †These subtypes were not directly available in GLOBOCAN 2012; therefore, data from the Cancer Incidence in

Five Continents (CI5-X) database were used to estimate the corresponding incidence. ‡NS=not shown because country-specific estimates were used (appendix). §In cancer tissue. ¶NA=not available because a

different method was used to calculate AF.

Table 1: General methods for the calculation of the AFs of infectious agents, by cancer type (International Classification of Diseases-10 code)

www.thelancet.com/lancetgh Vol 4 September 2016 e611

Articles

and relative risks. These estimates were combined using all the data in the study and had final responsibility for

a Bayesian perspective and calculated using Monte Carlo the decision to submit for publication.

methods and R software (version 3.1.1; appendix pp 1–2).14

Results

Role of the funding source Of the estimated 14 million new cancer cases worldwide

The funder of the study had no role in study design, data in 2012, 2·2 million (15·4%) were attributable to infection

collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of (table 2). AFs varied by region from 4·0% in North

the report. The corresponding author had full access to America to 31·3% in sub-Saharan Africa. AF was highest

in low-HDI countries and medium-HDI countries, and

lowest in countries with very high HDI (table 2). Two-

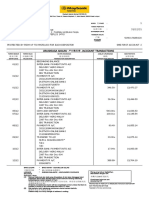

Number of new Number Attributable fraction (%)

cases attributable to

thirds of infection-attributable cancers (1·4 million cases)

infection occurred in less developed countries (table 2).

Worldwide 14 000 000 2 200 000 15·4% In 2012, the AFs of infection-related cancers were less

Africa than 5% in the USA, Canada, Australia, New Zealand,

Sub-Saharan Africa 630 000 200 000 31·3% and some countries in northern and western Europe, but

North Africa and west Asia 540 000 70 000 13·1% more than 40% in several countries in sub-Saharan

Asia Africa and in Mongolia (figure 1). The AF by country

Central Asia 1 500 000 290 000 19·4%

ranged from 3·6% in Sweden to more than 50% in

East Asia 4 900 000 1 100 000 22·8%

Malawi and Mozambique (appendix pp 22–26).

America

H pylori, HPV, HBV, and HCV were together

Latin America 1 100 000 160 000 14·4%

responsible for 2·0 million new cancer cases worldwide

in 2012 (table 3), with H pylori being the largest

North America 1 800 000 72 000 4·0%

contributor. The high burden of HPV-attributable cancer

Europe 3 400 000 250 000 7·2%

(predominantly cervical cancer) in women almost exactly

Oceania 160 000 7600 4·9%

counterbalanced the excess in men for all other infections,

Human Development Index

so that overall the numbers of cancers attributable to all

Very high 5 700 000 430 000 7·6%

infections were similar for both sexes (1·1 million each;

High 2 200 000 290 000 13·2%

table 3). According to GLOBOCAN 2012,4 64% of all

Medium 5 200 000 1 200 000 23·0%

cancers occur before age 70 years (which is the same age

Low 940 000 240 000 25·3%

limit that has been used by WHO since 201015 to define

Level of development

premature death from non-communicable diseases), but

More developed regions 7 900 000 730 000 9·2%

the corresponding proportion of such cancers was

Less developed regions 6 200 000 1 400 000 23·4%

considerably higher for cancers caused by HPV (86%),

Numbers of cases rounded to two significant figures. EBV (88%), and HHV-8 (90%) than for other cancers,

such as those caused by H pylori (57%; table 3).

Table 2: Number of new cancer cases in 2012 attributable to infectious agents, by geographical region

The burden of cancers attributable to infections was

and level of development

dominated by cancers of the stomach, liver, and cervix

Attributable fraction

<5%

5–9%

10–19%

20–29%

30–39%

≥40%

Figure 1: Attributable fraction of cancer related to infection, 2012

e612 www.thelancet.com/lancetgh Vol 4 September 2016

Articles

Number of Proportion of Number of new cases Number of new cases attributable

new cases new cases attributable to infection by age group

attributable to to infection by sex

each infectious

agent (%)

Males Females <50 years 50–69 years ≥70 years

Helicobacter pylori 770 000 35·4% 500 000 270 000 91 000 340 000 330 000

Human papillomavirus 640 000 29·5% 66 000 570 000 270 000 280 000 90 000

Hepatitis B virus 420 000 19·2% 300 000 120 000 84 000 190 000 140 000

Hepatitis C virus 170 000 7·8% 110 000 55 000 26 000 76 000 66 000

Epstein-Barr virus 120 000 5·5% 80 000 40 000 61 000 44 000 14 000

Human herpesvirus type 8 44 000 2·0% 29 000 15 000 32 000 7600 4500

Schistosoma haematobium 7000 0·3% 4900 2200 1300 3700 2100

Human T-cell lymphotropic virus, type 1 3000 0·1% 1700 1200 630 1200 1200

Opisthorchis viverrini or Clonorchis sinensis 1300 0·1% 820 470 130 670 490

All infectious agents 2 200 000 100·0% 1 100 000 1 100 000 570 000 950 000 650 000

Numbers of cases rounded to two significant figures.

Table 3: Number of new cancer cases in 2012 attributable to infection, by infectious agent

(table 4)—ie, the fifth, sixth, and seventh most common

Number of Number of Attributable

cancers worldwide, respectively, after lung, breast, new cases new cases fraction

colorectal, and prostate cancers.4 These cancer types also attributable

had very high infection-related AFs: 89·0% of non-cardia to infectious

agents

gastric cancer was attributable to H pylori, 73·4% of liver

cancer was attributable to HBV and HCV (a small Carcinoma

number of intrahepatic bile duct cancers caused by liver Non-cardia gastric 820 000 730 000 89·0%

flukes were also included), and 100·0% of cervical cancer Cardia gastric 130 000 23 000 17·8%

was caused by HPV. The global burden of HPV- Liver 780 000 570 000 73·4%

attributable cancer other than cervical cancer Cervix uteri 530 000 530 000 100·0%

(113 000 cases) was substantially lower than that of Vulva 34 000 8500 24·9%

cervical cancer (530 000 cases). Anus 40 000 35 000 88·0%

Figure 2 shows the total number of cancer cases by Penis 26 000 13 000 51·0%

cause, the burden of cancer attributable to infection by Vagina 15 000 12 000 78·0%

HDI (AF), and the proportion of cases attributable to Oropharynx 96 000 29 000 30·8%

each infectious agent. Low-HDI countries were the only Oral cavity 200 000 8700 4·3%

category that had a high proportion of HHV-8-related Larynx 160 000 7200 4·6%

cancers (14%, compared with 2% worldwide). Apart from Nasopharynx 87 000 83 000 95·5%

the burden of HHV-8-related cancers, low-HDI and Bladder 430 000 7000 1·6%

medium-HDI countries (excluding China) had a similar Lymphoma and leukaemia

range of infection-attributable cancers. China had a Hodgkin’s lymphoma 66 000 32 000 49·1%

unique pattern of such cancers, with a low proportion of Gastric non-Hodgkin 18 000 13 000 74·1%

HPV-attributable cancers and a high proportion of lymphoma

cancers caused by HBV and H pylori. H pylori also had an Burkitt’s lymphoma 9100 4700 52·2%

important contribution to the cancer burden in countries HCV-associated non- 360 000 13 000 3·6%

with high and very high HDIs. Whereas HBV Hodgkin lymphoma

predominates over HCV as a cause of liver cancer in low- Adult T-cell leukaemia 3000 3000 100·0%

and lymphoma

HDI and medium-HDI countries, HBV and HCV have

Sarcoma

similar contributions to the cancer burden in high-HDI

countries, and HCV predominates in countries with very Kaposi’s sarcoma 44 000 44 000 100·0%

high HDI. All infection-related 3 800 000 2 200 000 56·5%

cancer types

In both less developed and more developed countries,

the AFs were generally higher in younger age groups, Numbers rounded to two significant digits. HCV=hepatitis C virus.

peaking in people aged 40–45 years, except for women in

Table 4: Number of new cancer cases in 2012 attributable to infectious

more developed countries where the peak was in people agents, by cancer type

younger than 40 years (figure 3).

www.thelancet.com/lancetgh Vol 4 September 2016 e613

Articles

The ratio of liver cancers attributable to HBV and HCV

A

6000 Helicobacter pylori

varied substantially with HDI. Although HBV was more

Human papillomavirus important than HCV as a cause of cancer in low-HDI

Hepatitis B virus and medium-HDI countries, the opposite was true in

Hepatitis C virus

5000

Epstein-Barr virus countries with high and very high HDIs because of the

Human herpesvirus type 8 especially early spread of HCV in some countries with

Number of cancer cases (thousands)

Other infectious agents

4000 Not attributable to infection

very high HDI (eg, in 1930s in Japan) and the

diminishing prevalence of HBV with increasing HDI

(figure 2). Of note, the prevalence of HCV in the general

3000 population varied greatly between countries because of

differences in the presence and timing of mass episodes

2000

of iatrogenic transmission and, more recently,

AF=21·5% AF=24·2% AF=13·2% AF=7·6%

intravenous drug use.11,17

HPV caused more than half of all infection-attributable

1000 cancers in women worldwide. In low-HDI countries, it

AF=25·3%

accounted for half of infection-attributable cancers in

0

both sexes combined. Elevated rates of cervical cancer

resulted from poor screening and treatment of

B precancerous cervical lesions, in combination with high

prevalence of HPV and HIV infections.18

100

HHV-8 accounted for only 2% of infection-attributable

cancers worldwide, but in low-HDI countries this

Proportion of cancer cases attributable to infection (%)

proportion was 14%. Kaposi’s sarcoma mainly affects

80

individuals younger than 50 years and continues to be a

major public health concern in Africa, where HHV-8 is

endemic and large numbers of HIV-infected individuals

60

have late or no access to combined antiretroviral therapy.19

This Article is part of a periodic series of publications

assessing the burden of cancer due to infection.1–3,6

40

Worldwide, the AF for 2012 (15%) is similar to previous

estimates for 2008 (16%),1 2002 (18%),2 and 1990 (16%).3

However, these estimates are not directly comparable. Each

20

publication in this series represents a snapshot of the state

of knowledge at the time of publication, and the cancer data

sources and methods have both evolved with time.

0

Low HDI Medium HDI China High HDI Very high Major improvements over the previous report for 2008

(excluding HDI include AF estimates for individual countries, the re-

China)

assessment of the AFs of some major infections, and the

Figure 2: (A) Total number of cancer cases (by cause) and (B) proportion of addition of confidence intervals. We were able to separate

cancer cases attributable to different infectious agents, 2012 data for liver cancers attributable to HBV and HCV on the

AF=attributable fraction. HDI=Human Development Index.

basis of results from a systematic review in 2015.11 Other

reviews in the past 5 years have allowed more accurate

Discussion estimates of AFs using, for instance, prospective studies

In 2012, around 15% of cancer cases worldwide were of H pylori and non-cardia gastric cancer10 and updated

attributable to infectious agents. Two-thirds of infection- meta-analyses of Epstein-Barr virus infection prevalence

attributable cancers occurred in less developed countries, in Hodgkin’s lymphoma.20 For HPV in cancers of the head

in which infections accounted for nearly one in four and neck, multinational case series8,9 have added valuable

cancers. The main infectious agents contributing to the additional evidence of causality (appendix pp 5–6, 13–15).

cancer burden were H pylori, HPV, HBV, and HCV, An important improvement is the calculation of

which together accounted for 92% of all infection- country-level and HDI-level estimates of the burden

attributable cancers worldwide. of cancer attributable to infection. The distinct patterns

H pylori was the most important infectious cause of of cancer incidence by HDI were previously analysed by

cancer in countries with high and very high HDIs. Of note, Bray and colleagues,21 who noted that rapid societal and

the very high incidence of stomach cancers in Japan and socioeconomic transition in many countries means that

Korea is accompanied by an unusually good prognosis, any reductions in infection-related cancers are offset by

because of the intensive search for gastric lesions through an increasing number of new cases that are more

national endoscopic screening programmes.16 associated with reproductive, dietary, and hormonal

e614 www.thelancet.com/lancetgh Vol 4 September 2016

Articles

factors. AFs of cancers caused by infection were low in Women in less developed regions

35

countries with very high HDIs, but exceptions exist, Men in less developed regions

mainly because of a large burden of gastric and liver 30

Women in more developed regions

Men in more developed regions

cancer in, for example, Japan and Korea (AFs around

20% in both countries). Other countries with very high 25

Attributable fraction (%)

HDIs, notably those in Latin America and the Middle

East, had AFs of more than 10% (appendix pp 22–26). 20

These examples show that a substantial delay might exist

between socioeconomic development and reduction in 15

the proportion of infection-attributable cancers.

The main limitations of our study are associated with the 10

scarcity of representative data for infection prevalence and

of high-quality cancer registration in many populations, as 5

well as the difficulty in characterising the full degree of

uncertainty of our estimates. The 95% CIs for AF estimates 0

in table 1 represent the substantial strength of the <40 40–44 45–49 50–54 55–59 60–64 65–69 ≥70

association of individual infections with specific cancer Age (years)

types from meta-analyses or pooled data, but associations Figure 3: Proportion of cancer cases in 2012 attributable to infection, by sex, age group, and development

with other less well studied cancer types or subtypes status

remain less clear. For example, non-Hodgkin lymphoma

cases were considered together as attributable to HCV, immunisation programmes.24 Vaccination has been

although the association might vary with histological shown to prevent liver cancer in children and young

subtypes. Furthermore, few data exist for EBV presence by adults in Taiwan since it was introduced in 1984.25 The

non-Hodgkin lymphoma subtype in immunocompetent timely delivery of a vaccine dose within 24 h of birth has

populations, even though 5–10% of all non-Hodgkin become a performance measure for HBV immunisation

lymphoma cases might be attributable to EBV (appendix programmes.26 A birth dose had been introduced in

p 7). Another possible example of underestimation of the 96 countries by 2014, and the global coverage was

AFs is those for H pylori and gastric cardia cancer outside estimated at 38%, reaching 80% in the western Pacific,

east Asia, the only region where relevant data were but only 10% in Africa.24

available. Most importantly, the numbers of cases In the past 10 years, most countries in Europe and the

attributable to infection were derived from incidence Americas, as well as Australia, have introduced national

estimates from GLOBOCAN 2012,4 which does not give a HPV vaccination programmes targeting adolescent girls,

quantitative assessment of uncertainty. For individual but coverage varies vastly from less than 30% to more than

countries, however, the alphanumeric quality score from 80%.27 Large efforts are necessary to improve coverage and

GLOBOCAN—which describes the quality and coverage bring HPV vaccination to less developed countries in sub-

of incidence data (A–G) and the accuracy of the methods Saharan Africa and Asia. Vaccination programmes with a

used to estimate incidence (1–9; appendix p 26)—provides coverage of at least 80% have been shown to be achievable

a useful qualitative assessment of the uncertainty of the in less developed countries such as Rwanda and Bhutan.

incidence estimates. Countries with the highest score (A1) Gavi, The Vaccine Alliance, is bringing relatively low-cost

should generally have accurate incidence estimates, HPV vaccines to dozens of additional countries with few

whereas estimates for countries with the lowest score (G9) financial resources.27 The screening of women older than

represent a best guess in the complete absence of country- 30 years, possibly with affordable rapid HPV tests, has also

specific data. Special caution should be used for countries been endorsed by WHO.28

that showed very high AFs for infection, as this finding A national HCV screen-and-treat programme of

might be due to incomplete registration of cancers that are individuals born between 1945 and 1965 has been

not associated with infections.22 launched in the USA, taking advantage of highly effective

Our findings suggest that the potential for reducing the but still very expensive new antiviral treatments.23 A

burden of cancer is large. However, the proportion of global reduction in liver cancer caused by HCV and HBV

preventable cancers might be considerably lower than will depend on the identification and appropriate referral

the AF and will depend on the resources available for the of individuals at risk, and on the widespread delivery and

implementation of large-scale interventions. It is affordability of these new treatments in different

encouraging that highly effective prophylactic vaccines countries.29

(against HBV and HPV) and screen-and-treat strategies Early initiation of combined antiretroviral therapy is

(for HPV and HCV) exist and are being implemented in associated with massive reductions in the risk of

some countries.18,23 developing Kaposi’s sarcoma.30 The 2015 WHO clinical

As of 2014, 184 countries had incorporated the HBV guidelines31 recommend the initiation of combined anti-

vaccine as an integral part of their national infant retroviral therapy in all HIV-positive individuals

www.thelancet.com/lancetgh Vol 4 September 2016 e615

Articles

regardless of clinical stage or CD4-positive cell count. 9 Ndiaye C, Mena M, Alemany L, et al. HPV DNA, E6/E7 mRNA, and

This strategy has the potential to prevent most cases of p16INK4a detection in head and neck cancers: a systematic review and

meta-analysis. Lancet Oncol 2014; 15: 1319–31.

Kaposi’s sarcoma and possibly a fraction of HPV- 10 Plummer M, Franceschi S, Vignat J, Forman D, de Martel C.

associated cancer in sub-Saharan Africa.32 Global burden of gastric cancer attributable to Helicobacter pylori.

Last but not least, our results highlight the continuing Int J Cancer 2015; 136: 487–90.

11 de Martel C, Maucort-Boulch D, Plummer M, Franceschi S.

importance of H pylori as an infectious cause of cancer in Worldwide relative contribution of hepatitis B and C viruses in

many world regions, including some more developed hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology 2015; 62: 1190–200.

countries. Anti-H pylori therapy has been overlooked as a 12 Human Development Report 2013: the rise of the south: human

progress in a diverse world. New York: UN Development Program,

strategy for cancer prevention because of concerns about 2013. http://hdr.undp.org/en/2013-report (accessed May 20, 2015).

the widespread use of antibiotics and the possibility that 13 Human Development Report 2015: work for human development.

H pylori eradication might increase the risk of oesophageal New York: UN Development Program, 2015. http://hdr.undp.org/

cancer.7 Nevertheless, an IARC working group has en/2015-report (accessed May 20, 2015).

14 Roberts CP, Casella G. Monte Carlo statistical methods. New York:

recommended that countries explore the possibility of Springer-Verlage, 2004.

introducing population-based H pylori screening and 15 WHO. Global status report on noncommunicable diseases 2010.

treatment programmes for gastric cancer control.33 Annex 5: core indicators for consideration as part of the framework

for NCD surveillance. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2011.

In conclusion, carcinogenic infections remain an

16 Shin HR, Shin A, Woo H, et al. Prevention of infection-related

important cause of cancer worldwide, especially in less cancers in the WHO western Pacific region. Jpn J Clin Oncol 2016;

developed countries. For several of the infections we 46: 13–22.

assessed, with the exception of sexually transmitted 17 Bruggmann P, Berg T, Ovrehus AL, et al. Historical epidemiology

of hepatitis C virus (HCV) in selected countries. J Viral Hepat 2014;

HPV,18 socioeconomic development is associated with a 21 (suppl 1): 5–33.

reduction in transmission or in progression to cancer. 18 Crosbie EJ, Einstein MH, Franceschi S, Kitchener HC.

However, socioeconomic development is not sufficient to Human papillomavirus and cervical cancer. Lancet 2013; 382: 889–99.

19 Robey RC, Bower M. Facing up to the ongoing challenge of Kaposi’s

reduce the infection-associated cancer burden, unless sarcoma. Curr Opin Infect Dis 2015; 28: 31–40.

population-based interventions similar to those 20 Lee JH, Kim Y, Choi JW, Kim YS. Prevalence and prognostic

implemented in some countries with very high HDIs are significance of Epstein-Barr virus infection in classical Hodgkin’s

prioritised and made cost-effective in the rest of lymphoma: a meta-analysis. Arch Med Res 2014; 45: 417–31.

21 Bray F, Jemal A, Grey N, Ferlay J, Forman D. Global cancer

the world. transitions according to the Human Development Index (2008–2030):

Contributors a population-based study. Lancet Oncol 2012; 13: 790–801.

SF, MP, and CdM conceived and designed the study. JF provided cancer 22 Shimakawa Y, Bah E, Wild CP, Hall AJ. Evaluation of data quality at

incidence estimates adapted from the GLOBOCAN 2012 database. MP, JV, the Gambia national cancer registry. Int J Cancer 2013; 132: 658–65.

and FB collected and analysed the data collection. CdM and MP drafted the 23 Smith BD, Beckett GA, Yartel A, Holtzman D, Patel N, Ward JW.

manuscript. All authors contributed to the interpretation of data and Previous exposure to HCV among persons born during 1945–1965:

approved the final manuscript. prevalence and predictors, United States, 1999–2008.

Am J Public Health 2014; 104: 474–81.

Declaration of interests 24 WHO. Global immunization data 2015. Geneva: World Health

We declare no competing interests. Organization, 2015. http://www.who.int/immunization/monitoring_

surveillance/Global_Immunization_Data.pdf (accessed Nov 23, 2015).

Acknowledgments

25 Hung GY, Horng JL, Yen HJ, Lee CY, Lin LY. Changing incidence

CdM acknowledges funding from the Fondation de France (grant

patterns of hepatocellular carcinoma among age groups in Taiwan.

number 00039621).

J Hepatol 2015; 63: 1390–96.

References 26 WHO Publication. Hepatitis B vaccines: WHO position

1 de Martel C, Ferlay J, Franceschi S, et al. Global burden of cancers paper—recommendations. Vaccine 2010; 28: 589–90.

attributable to infections in 2008: a review and synthetic analysis. 27 Hanson CM, Eckert L, Bloem P, Cernuschi T. Gavi HPV programs:

Lancet Oncol 2012; 13: 607–15. application to implementation. Vaccines (Basel) 2015; 3: 408–19.

2 Parkin DM. The global health burden of infection-associated 28 Human papillomavirus vaccines: WHO position paper, October 2014.

cancers in the year 2002. Int J Cancer 2006; 118: 3030–44. Wkly Epidemiol Rec 2014; 89: 465–91.

3 Pisani P, Parkin DM, Munoz N, Ferlay J. Cancer and infection: 29 WHO. WHO guidelines approved by the Guidelines Review

estimates of the attributable fraction in 1990. Committee. Guidelines for the prevention, care and treatment of

Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 1997; 6: 387–400. persons with chronic hepatitis B infection. Geneva: World Health

4 Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Ervik M, et al. GLOBOCAN 2012 v1.0, Organization, 2015.

Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: IARC CancerBase 30 Bohlius J, Valeri F, Maskew M, et al. Kaposi’s sarcoma in

no. 11. 2013. Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer. HIV-infected patients in South Africa: multicohort study in the

http://GLOBOCAN.iarc.fr (accessed May 12, 2015). antiretroviral therapy era. Int J Cancer 2014; 135: 2644–52.

5 IARC. Biological agents. IARC Monogr Eval Carcinog Risks Hum 31 WHO. Policy brief: consolidated guidelines on the use of

2012; 100B: 1–475. http://monographs.iarc.fr/ENG/Monographs/ antiretroviral drugs for treating and preventing HIV infection:

vol100B/index.php (accessed May 12, 2015). what’s new. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2015. http://

6 de Martel C, Shiels MS, Franceschi S, et al. Cancers attributable to www.who.int/iris/handle/10665/198064 (accessed June 15, 2016).

infections among adults with HIV in the United States. AIDS 2015; 32 Clifford GM, de Vuyst H, Tenet V, Plummer M, Tully S,

29: 2173–81. Franceschi S. Effect of HIV infection on human papillomavirus

7 IARC Helicobacter pylori Working Group. Helicobacter pylori types causing invasive cervical cancer in Africa.

eradication as a strategy for preventing gastric cancer. IARC J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2016; published online June 15.

Working Group Reports No. 8. Lyon, France: International Agency DOI:10.1097/QAI.0000000000001113.

for Research on Cancer, 2014. https://www.iarc.fr/en/publications/ 33 Herrero R, Park JY, Forman D. The fight against gastric cancer—

pdfs-online/wrk/wrk8/index.php (accessed May 18, 2015). the IARC Working Group report. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol

8 Combes JD, Franceschi S. Role of human papillomavirus in non- 2014; 28: 1107–14.

oropharyngeal head and neck cancers. Oral Oncol 2014; 50: 370–79.

e616 www.thelancet.com/lancetgh Vol 4 September 2016

You might also like

- Global Burden of Cancers Attributable To Infections in 2008: A Review and Synthetic AnalysisDocument9 pagesGlobal Burden of Cancers Attributable To Infections in 2008: A Review and Synthetic AnalysisSabrina ParenteNo ratings yet

- Chlamaydia Molecular CharacterizationDocument7 pagesChlamaydia Molecular CharacterizationMulatuNo ratings yet

- Prevention of Inection Related Tumor Bgr054Document9 pagesPrevention of Inection Related Tumor Bgr054heruNo ratings yet

- Epidemiology and Risk Factors For Invasive CandidiasisDocument11 pagesEpidemiology and Risk Factors For Invasive Candidiasisrk_solomonNo ratings yet

- Priority COVID-19 Vaccination For Patients With Cancer While Vaccine Supply Is LimitedDocument14 pagesPriority COVID-19 Vaccination For Patients With Cancer While Vaccine Supply Is LimiteddanielNo ratings yet

- HIV Epidemiology Among Female Sex Workers and Their Clients in The Middle East and North Africa: Systematic Review, Meta-Analyses, and Meta-RegressionsDocument30 pagesHIV Epidemiology Among Female Sex Workers and Their Clients in The Middle East and North Africa: Systematic Review, Meta-Analyses, and Meta-RegressionsLuís MiguelNo ratings yet

- Review ArticleDocument12 pagesReview ArticleNoka YogaNo ratings yet

- Neumo8 Lecturas TBC SeminarioDocument15 pagesNeumo8 Lecturas TBC SeminarioMercedes Johanny Ortiz ChinguelNo ratings yet

- Papillomavirus Research: SciencedirectDocument17 pagesPapillomavirus Research: SciencedirectIvanes IgorNo ratings yet

- Ijc 25396Document9 pagesIjc 25396behanges71No ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S2666679022000040 MainDocument14 pages1 s2.0 S2666679022000040 MainRahmayantiYuliaNo ratings yet

- Arc, 2022Document28 pagesArc, 2022MARIA FERNANDA OLIVEIRA SOARESNo ratings yet

- Hepatocellular Carcinoma in HIV Positive PatientsDocument14 pagesHepatocellular Carcinoma in HIV Positive PatientsBayarbaatar BoldNo ratings yet

- E1317 The Incidence and Mortality of Ovarian Cancer Its Association With Body Mass Index and Human Development Index An Ecological StudyDocument12 pagesE1317 The Incidence and Mortality of Ovarian Cancer Its Association With Body Mass Index and Human Development Index An Ecological StudyDian Putri NingsihNo ratings yet

- Re Ections On 40 Years of AIDS: PerspectiveDocument8 pagesRe Ections On 40 Years of AIDS: PerspectiveANGEL OMAR SANTANA AVILANo ratings yet

- Global Cancer Statistics 2018 - GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide For 36 Cancers in 185 CountriesDocument32 pagesGlobal Cancer Statistics 2018 - GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide For 36 Cancers in 185 CountriesGlauber MacielNo ratings yet

- Ali2019 Article BurdenAndGenotypeDistributionO PDFDocument9 pagesAli2019 Article BurdenAndGenotypeDistributionO PDFDhimas MuhammadNo ratings yet

- Fruits and Vegetables and Cervical Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-AnalysisDocument14 pagesFruits and Vegetables and Cervical Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-AnalysisSf AkhadiyatiNo ratings yet

- Human Papillomavirus InfectionDocument78 pagesHuman Papillomavirus InfectionJoaquín PeñaNo ratings yet

- Carol E. 2015Document12 pagesCarol E. 2015Andrea QuillupanguiNo ratings yet

- Global Cancer Transitions According To The Human Development Index (2008-2030) : A Population-Based StudyDocument12 pagesGlobal Cancer Transitions According To The Human Development Index (2008-2030) : A Population-Based StudyLis RibeiroNo ratings yet

- Fatema Alzahraa Samy Amin Molecular Markers PredictingDocument10 pagesFatema Alzahraa Samy Amin Molecular Markers PredictingtomniucNo ratings yet

- Stis in SwazilandDocument12 pagesStis in SwazilandMuhammad FansyuriNo ratings yet

- Prevalence and Incidence of Genital Warts and Cervical Human Papillomavirus Infections in Nigerian WomenDocument10 pagesPrevalence and Incidence of Genital Warts and Cervical Human Papillomavirus Infections in Nigerian WomenRiszki_03No ratings yet

- Resistencia BacterianaDocument27 pagesResistencia BacterianaSMIBA MedicinaNo ratings yet

- Global Cancer Incidences, Causes and Future PredictionsDocument6 pagesGlobal Cancer Incidences, Causes and Future PredictionsJorge BriseñoNo ratings yet

- Global Burden of Bacterial Antimicrobial Resistance in 2019 A Systematic AnalysisDocument27 pagesGlobal Burden of Bacterial Antimicrobial Resistance in 2019 A Systematic AnalysisMarco OliveiraNo ratings yet

- Global Cancer Transitions According To The Human Development Index (2008-2030) A Population-Based StudyDocument12 pagesGlobal Cancer Transitions According To The Human Development Index (2008-2030) A Population-Based StudyCristian Gutiérrez VeraNo ratings yet

- HPV Types in 115789 HPV-pos Women - A Meta-Analysis From Cervical Infection To CancerDocument11 pagesHPV Types in 115789 HPV-pos Women - A Meta-Analysis From Cervical Infection To CancerKen WayNo ratings yet

- JAMA Oncology - : Original InvestigationDocument20 pagesJAMA Oncology - : Original InvestigationMuhammad SyukriNo ratings yet

- Historia Natural Del HPVDocument5 pagesHistoria Natural Del HPVpatologiacervicalupcNo ratings yet

- Meng Yin Wu 2020Document9 pagesMeng Yin Wu 2020Ryan PratamaNo ratings yet

- Articulo 5Document15 pagesArticulo 5kevinNo ratings yet

- Antiretroviral Therapy For Prevention of HIV Transmission: Implications For EuropeDocument23 pagesAntiretroviral Therapy For Prevention of HIV Transmission: Implications For EuropenukarevaNo ratings yet

- A Modifiable Risk Factors Atlas of Lung Cancer A MendelianDocument17 pagesA Modifiable Risk Factors Atlas of Lung Cancer A MendeliangiziklinikfkudayanaNo ratings yet

- Global Cancer Incidence and Mortality Rates and Trends - An UpdateDocument13 pagesGlobal Cancer Incidence and Mortality Rates and Trends - An UpdateBogdan HateganNo ratings yet

- Jurnal ReadingDocument12 pagesJurnal ReadingRenaldo tegar Prasetyo.DNo ratings yet

- 2020 06 23 20111419v2 Full PDFDocument17 pages2020 06 23 20111419v2 Full PDFFelipe BrandãoNo ratings yet

- Fitzmaurice - 2019 - Carga GlobalDocument20 pagesFitzmaurice - 2019 - Carga GlobalAdriana VargasNo ratings yet

- Using HPV Prevalence To Predict Cervical Cancer IncidenceDocument6 pagesUsing HPV Prevalence To Predict Cervical Cancer Incidencenyoman2No ratings yet

- IJC 9999 NaDocument29 pagesIJC 9999 NaSimona VisanNo ratings yet

- Civ813 PDFDocument7 pagesCiv813 PDFzevillaNo ratings yet

- Review Article: Chagas' Disease: Pregnancy and Congenital TransmissionDocument11 pagesReview Article: Chagas' Disease: Pregnancy and Congenital Transmissiondiaa skamNo ratings yet

- Ale Many 2014Document37 pagesAle Many 2014Tatiane RibeiroNo ratings yet

- CA A Cancer J Clinicians - 2018 - Bray - Global Cancer Statistics 2018 GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and MortalityDocument31 pagesCA A Cancer J Clinicians - 2018 - Bray - Global Cancer Statistics 2018 GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and MortalityAngelia Adinda AnggonoNo ratings yet

- Tuberculosis Vih EthiopiaDocument9 pagesTuberculosis Vih Ethiopiajulma1306No ratings yet

- Human Papillomavirus-Associated Cancers in Patients With Human Immunodeficiency Virus Infection and Acquired Immunodeficiency SyndromeDocument11 pagesHuman Papillomavirus-Associated Cancers in Patients With Human Immunodeficiency Virus Infection and Acquired Immunodeficiency SyndromeKerin ArdyNo ratings yet

- 1279 2020 Article 49Document9 pages1279 2020 Article 49mimiNo ratings yet

- VasavanSharangi Assign2Document11 pagesVasavanSharangi Assign2sharangiivNo ratings yet

- WA0054mmmDocument4 pagesWA0054mmmA HNo ratings yet

- ReferatDocument18 pagesReferatFannyNo ratings yet

- Articles: BackgroundDocument15 pagesArticles: BackgroundRajnish Ranjan PrasadNo ratings yet

- TB NewDocument6 pagesTB NewTirza StevanyNo ratings yet

- Research Paper On h1n1 VirusDocument5 pagesResearch Paper On h1n1 Viruszijkchbkf100% (1)

- P Reddy SAJS 2017Document6 pagesP Reddy SAJS 2017Sumayyah EbrahimNo ratings yet

- Project Proposal Charera CPDocument27 pagesProject Proposal Charera CPClifford ChareraNo ratings yet

- Managing Patients With Hematological Malignancies During COVID 19 PandemicDocument8 pagesManaging Patients With Hematological Malignancies During COVID 19 PandemicSONIA MARLENE HUARACHE HERRERANo ratings yet

- Esmo. Cancer de AnoDocument11 pagesEsmo. Cancer de AnoCarlos Cruz RNo ratings yet

- 1722 FullDocument7 pages1722 FullAbbasIbraheemNo ratings yet

- A Comparative Proteomic Analysis of Erinacine A's Inhibition of Gastric Cancer Cell Viability and InvasivenessDocument14 pagesA Comparative Proteomic Analysis of Erinacine A's Inhibition of Gastric Cancer Cell Viability and InvasivenessMartinaNo ratings yet

- Microbiome in Sjögren's Syndrome - Here We AreDocument2 pagesMicrobiome in Sjögren's Syndrome - Here We AreMartinaNo ratings yet

- Widespread Protein Lysine Acetylation in Gut Microbiome and Its Alterations in Patients With Crohn's DiseaseDocument12 pagesWidespread Protein Lysine Acetylation in Gut Microbiome and Its Alterations in Patients With Crohn's DiseaseMartinaNo ratings yet

- The Relationship Between Fecal Bile Acids and Microbiome CounityDocument12 pagesThe Relationship Between Fecal Bile Acids and Microbiome CounityMartinaNo ratings yet

- Safety, Clinical Response, and Microbiome Findings Following Fecal Microbiota Transplant in Children With Inflammatory Bowel DiseaseDocument12 pagesSafety, Clinical Response, and Microbiome Findings Following Fecal Microbiota Transplant in Children With Inflammatory Bowel DiseaseMartinaNo ratings yet

- Iron Fortification Adversely Affects The Gut ..Document12 pagesIron Fortification Adversely Affects The Gut ..MartinaNo ratings yet

- A Microbiome Foundation For The Study of Crohn's DiseaseDocument4 pagesA Microbiome Foundation For The Study of Crohn's DiseaseMartinaNo ratings yet

- The Microbiome and Hepatocellular CarcinomaDocument29 pagesThe Microbiome and Hepatocellular CarcinomaMartinaNo ratings yet

- Blastocystis Gut MicrobiomeDocument18 pagesBlastocystis Gut MicrobiomeFreddy FranklinNo ratings yet

- Decreased Fecal Calprotectin Levels in Cystic Fibrosis Patients After Antibiotic Treatment For Respiratory ExacerbationDocument3 pagesDecreased Fecal Calprotectin Levels in Cystic Fibrosis Patients After Antibiotic Treatment For Respiratory ExacerbationMartinaNo ratings yet

- Fecal Calprotectin and Fecal Indole Predict Outcome of FecalDocument4 pagesFecal Calprotectin and Fecal Indole Predict Outcome of FecalMartinaNo ratings yet

- Fecal Microbiota Transplant For Crohn Disease - ADocument8 pagesFecal Microbiota Transplant For Crohn Disease - AMartinaNo ratings yet

- Carbohydrate (HC), Mediterranean (MD) and Western (WD) Diets. HC WasDocument2 pagesCarbohydrate (HC), Mediterranean (MD) and Western (WD) Diets. HC WasMartinaNo ratings yet

- Assessment of Complementary Feeding of Canadian Infants - Effects On Microbiome & Oxidative Stress, A Randomized Controlled TrialDocument12 pagesAssessment of Complementary Feeding of Canadian Infants - Effects On Microbiome & Oxidative Stress, A Randomized Controlled TrialMartinaNo ratings yet

- The Researchers To Design, Research, and Develop New Drugs ForDocument19 pagesThe Researchers To Design, Research, and Develop New Drugs ForMartinaNo ratings yet

- Izab 277Document10 pagesIzab 277MartinaNo ratings yet

- Molecules: Ffects of Rich in B-Glucans Edible MushroomsDocument25 pagesMolecules: Ffects of Rich in B-Glucans Edible Mushroomsharry potterNo ratings yet

- The Gut Microbiome As A Target For IBD Treatment - Are We There YetDocument12 pagesThe Gut Microbiome As A Target For IBD Treatment - Are We There YetMartinaNo ratings yet

- Microbiome Risk Profiles As Biomarkers For Inflammatory and Metabolic DisordersDocument15 pagesMicrobiome Risk Profiles As Biomarkers For Inflammatory and Metabolic DisordersMartinaNo ratings yet

- Molecules: Ffects of Rich in B-Glucans Edible MushroomsDocument25 pagesMolecules: Ffects of Rich in B-Glucans Edible Mushroomsharry potterNo ratings yet

- Internal Connections Between Dietary Intake and Gut Microbiota Homeostasis in Disease Progression of Ulcerative Colitis - A ReviewDocument12 pagesInternal Connections Between Dietary Intake and Gut Microbiota Homeostasis in Disease Progression of Ulcerative Colitis - A ReviewMartinaNo ratings yet

- Hericium Erinaceus, An Amazing Medicinal MushroomDocument24 pagesHericium Erinaceus, An Amazing Medicinal MushroomMartinaNo ratings yet

- Polysaccharides From Natural Resources Exhibit Great Potential in The Treatment of Ulcerative Colitis - A ReviewDocument12 pagesPolysaccharides From Natural Resources Exhibit Great Potential in The Treatment of Ulcerative Colitis - A ReviewMartinaNo ratings yet

- Health Benefits of Edible Mushroom Polysaharidesand Associated Gut Microbiota RegulationDocument19 pagesHealth Benefits of Edible Mushroom Polysaharidesand Associated Gut Microbiota RegulationMartinaNo ratings yet

- A Review of Mushrooms in Human Nutrition and HealthDocument14 pagesA Review of Mushrooms in Human Nutrition and HealthBegoña MartinezNo ratings yet

- The Researchers To Design, Research, and Develop New Drugs ForDocument19 pagesThe Researchers To Design, Research, and Develop New Drugs ForMartinaNo ratings yet

- A Review of The Effects of Natural Compounds, Medical Plants, Mushrooms On Thegut Microbiota and Colitis and CancerDocument8 pagesA Review of The Effects of Natural Compounds, Medical Plants, Mushrooms On Thegut Microbiota and Colitis and CancerMartinaNo ratings yet

- Clinical and Physiological Perspectives of βGlucans in The Past, Present, and FutureDocument48 pagesClinical and Physiological Perspectives of βGlucans in The Past, Present, and FutureQualityMattersNo ratings yet

- Recent Developments in Hericium Erinaceus Polysaccharides - Extraction, Purifacion, Structur Characterist and Biology ActivityDocument21 pagesRecent Developments in Hericium Erinaceus Polysaccharides - Extraction, Purifacion, Structur Characterist and Biology ActivityMartinaNo ratings yet

- The Role of Gut Microbiota Biomodulators On Mucosal Imuniti and Intestinal InflamationDocument24 pagesThe Role of Gut Microbiota Biomodulators On Mucosal Imuniti and Intestinal InflamationMartinaNo ratings yet

- I. Lesson Plan Overview and DescriptionDocument5 pagesI. Lesson Plan Overview and Descriptionapi-283247632No ratings yet

- Business Law Term PaperDocument19 pagesBusiness Law Term PaperDavid Adeabah OsafoNo ratings yet

- Gucci MurderDocument13 pagesGucci MurderPatsy StoneNo ratings yet

- 10.MIL 9. Current and Future Trends in Media and InformationDocument26 pages10.MIL 9. Current and Future Trends in Media and InformationJonar Marie100% (1)

- Hp Ux系统启动的日志rcDocument19 pagesHp Ux系统启动的日志rcMq SfsNo ratings yet

- Running Head: Mental Illness As A Cause of Homelessness 1Document12 pagesRunning Head: Mental Illness As A Cause of Homelessness 1api-286680238No ratings yet

- Business Communication EnglishDocument191 pagesBusiness Communication EnglishkamaleshvaranNo ratings yet

- Fabled 6Document75 pagesFabled 6joaamNo ratings yet

- Specifications: Back2MaintableofcontentsDocument31 pagesSpecifications: Back2MaintableofcontentsRonal MoraNo ratings yet

- Upvc CrusherDocument28 pagesUpvc Crushermaes fakeNo ratings yet

- Member, National Gender Resource Pool Philippine Commission On WomenDocument66 pagesMember, National Gender Resource Pool Philippine Commission On WomenMonika LangngagNo ratings yet

- MoncadaDocument3 pagesMoncadaKimiko SyNo ratings yet

- Do 18-A and 18 SGV V de RaedtDocument15 pagesDo 18-A and 18 SGV V de RaedtThomas EdisonNo ratings yet

- GSRTCDocument1 pageGSRTCAditya PatelNo ratings yet

- Precontraint 502S2 & 702S2Document1 pagePrecontraint 502S2 & 702S2Muhammad Najam AbbasNo ratings yet

- BE 601 Class 2Document17 pagesBE 601 Class 2Chan DavidNo ratings yet

- Gaffney S Business ContactsDocument6 pagesGaffney S Business ContactsSara Mitchell Mitchell100% (1)

- Forge Innovation Handbook Submission TemplateDocument17 pagesForge Innovation Handbook Submission Templateakil murugesanNo ratings yet

- Purposive Communication GROUP 9Document61 pagesPurposive Communication GROUP 9Oscar DemeterioNo ratings yet

- A Copmanion To Love Druga KnjigaDocument237 pagesA Copmanion To Love Druga KnjigaSer YandeNo ratings yet

- Build The Tango: by Hank BravoDocument57 pagesBuild The Tango: by Hank BravoMarceloRossel100% (1)

- Plant-Biochemistry-by-Heldt - 2005 - Pages-302-516-79-86 PDFDocument8 pagesPlant-Biochemistry-by-Heldt - 2005 - Pages-302-516-79-86 PDF24 ChannelNo ratings yet

- Assessment Guidelines For Processing Operations Hydrocarbons VQDocument47 pagesAssessment Guidelines For Processing Operations Hydrocarbons VQMatthewNo ratings yet

- Brand Brand Identity: What Are Brand Elements? 10 Different Types of Brand ElementsDocument3 pagesBrand Brand Identity: What Are Brand Elements? 10 Different Types of Brand ElementsAŋoop KrīşħŋặNo ratings yet

- Education-and-Life-in-Europe - Life and Works of RizalDocument3 pagesEducation-and-Life-in-Europe - Life and Works of Rizal202202345No ratings yet

- Bethany Pinnock - Denture Care Instructions PamphletDocument2 pagesBethany Pinnock - Denture Care Instructions PamphletBethany PinnockNo ratings yet

- Kangar 1 31/12/21Document4 pagesKangar 1 31/12/21TENGKU IRSALINA SYAHIRAH BINTI TENGKU MUHAIRI KTNNo ratings yet

- Sir Phillip Manderson SherlockDocument1 pageSir Phillip Manderson SherlockSkyber TeachNo ratings yet

- The Constitution Con by Michael TsarionDocument32 pagesThe Constitution Con by Michael Tsarionsilent_weeper100% (1)

- TOEFLDocument27 pagesTOEFLAmalia Nurhidayah100% (1)

- By the Time You Read This: The Space between Cheslie's Smile and Mental Illness—Her Story in Her Own WordsFrom EverandBy the Time You Read This: The Space between Cheslie's Smile and Mental Illness—Her Story in Her Own WordsNo ratings yet

- The Age of Magical Overthinking: Notes on Modern IrrationalityFrom EverandThe Age of Magical Overthinking: Notes on Modern IrrationalityRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (28)

- Raising Mentally Strong Kids: How to Combine the Power of Neuroscience with Love and Logic to Grow Confident, Kind, Responsible, and Resilient Children and Young AdultsFrom EverandRaising Mentally Strong Kids: How to Combine the Power of Neuroscience with Love and Logic to Grow Confident, Kind, Responsible, and Resilient Children and Young AdultsRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Think This, Not That: 12 Mindshifts to Breakthrough Limiting Beliefs and Become Who You Were Born to BeFrom EverandThink This, Not That: 12 Mindshifts to Breakthrough Limiting Beliefs and Become Who You Were Born to BeRating: 2 out of 5 stars2/5 (1)

- Summary: The Psychology of Money: Timeless Lessons on Wealth, Greed, and Happiness by Morgan Housel: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedFrom EverandSummary: The Psychology of Money: Timeless Lessons on Wealth, Greed, and Happiness by Morgan Housel: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (81)

- LIT: Life Ignition Tools: Use Nature's Playbook to Energize Your Brain, Spark Ideas, and Ignite ActionFrom EverandLIT: Life Ignition Tools: Use Nature's Playbook to Energize Your Brain, Spark Ideas, and Ignite ActionRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (404)

- Summary: Outlive: The Science and Art of Longevity by Peter Attia MD, With Bill Gifford: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisFrom EverandSummary: Outlive: The Science and Art of Longevity by Peter Attia MD, With Bill Gifford: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (42)

- The Obesity Code: Unlocking the Secrets of Weight LossFrom EverandThe Obesity Code: Unlocking the Secrets of Weight LossRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (6)

- ADHD is Awesome: A Guide to (Mostly) Thriving with ADHDFrom EverandADHD is Awesome: A Guide to (Mostly) Thriving with ADHDRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- The Ritual Effect: From Habit to Ritual, Harness the Surprising Power of Everyday ActionsFrom EverandThe Ritual Effect: From Habit to Ritual, Harness the Surprising Power of Everyday ActionsRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (3)

- When the Body Says No by Gabor Maté: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisFrom EverandWhen the Body Says No by Gabor Maté: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2)

- Dark Psychology & Manipulation: Discover How To Analyze People and Master Human Behaviour Using Emotional Influence Techniques, Body Language Secrets, Covert NLP, Speed Reading, and Hypnosis.From EverandDark Psychology & Manipulation: Discover How To Analyze People and Master Human Behaviour Using Emotional Influence Techniques, Body Language Secrets, Covert NLP, Speed Reading, and Hypnosis.Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (110)

- The Body Keeps the Score by Bessel Van der Kolk, M.D. - Book Summary: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of TraumaFrom EverandThe Body Keeps the Score by Bessel Van der Kolk, M.D. - Book Summary: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of TraumaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Raising Good Humans: A Mindful Guide to Breaking the Cycle of Reactive Parenting and Raising Kind, Confident KidsFrom EverandRaising Good Humans: A Mindful Guide to Breaking the Cycle of Reactive Parenting and Raising Kind, Confident KidsRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (170)

- Why We Die: The New Science of Aging and the Quest for ImmortalityFrom EverandWhy We Die: The New Science of Aging and the Quest for ImmortalityRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (3)

- Gut: the new and revised Sunday Times bestsellerFrom EverandGut: the new and revised Sunday Times bestsellerRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (392)

- Sleep Stories for Adults: Overcome Insomnia and Find a Peaceful AwakeningFrom EverandSleep Stories for Adults: Overcome Insomnia and Find a Peaceful AwakeningRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (3)

- 12 Rules for Life by Jordan B. Peterson - Book Summary: An Antidote to ChaosFrom Everand12 Rules for Life by Jordan B. Peterson - Book Summary: An Antidote to ChaosRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (207)

- Outlive: The Science and Art of Longevity by Peter Attia: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisFrom EverandOutlive: The Science and Art of Longevity by Peter Attia: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Cult, A Love Story: Ten Years Inside a Canadian Cult and the Subsequent Long Road of RecoveryFrom EverandCult, A Love Story: Ten Years Inside a Canadian Cult and the Subsequent Long Road of RecoveryRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (44)

- Mindset by Carol S. Dweck - Book Summary: The New Psychology of SuccessFrom EverandMindset by Carol S. Dweck - Book Summary: The New Psychology of SuccessRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (328)

- The Marshmallow Test: Mastering Self-ControlFrom EverandThe Marshmallow Test: Mastering Self-ControlRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (58)

- A Brief History of Intelligence: Evolution, AI, and the Five Breakthroughs That Made Our BrainsFrom EverandA Brief History of Intelligence: Evolution, AI, and the Five Breakthroughs That Made Our BrainsRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (6)