Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Ağır2013 - Evolution of Grain Policy

Uploaded by

ikame jetOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Ağır2013 - Evolution of Grain Policy

Uploaded by

ikame jetCopyright:

Available Formats

The Evolution of Grain Policy: The Ottoman Experience

Author(s): Seven Ağir

Source: The Journal of Interdisciplinary History , Spring 2013, Vol. 43, No. 4 (Spring

2013), pp. 571-598

Published by: The MIT Press

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/43829898

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

The MIT Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The

Journal of Interdisciplinary History

This content downloaded from

176.235.136.130 on Sun, 24 Mar 2024 12:11:13 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Journal of Interdisdplinary History, xliii:4 (Spring, 2013), 571-598.

Seven Agir

The Evolution of Grain Policy: The Ottoman

Experience Recent debates about the "great divergence" be-

tween Western Europe and the rest of the world have brought

comparative analysis to the forefront of research. Yet, the Otto-

man Empire, with its history spanning six centuries and three con-

tinents, has found litde place in this literature. The nature of Otto-

man institutions and institutional change, more specifically the

ways in which the motives and the tools of the Ottoman eco-

nomic policies were shaped, have scarcely been examined. This

study attempts to help fill this gap by studying the changes in the

Ottoman grain policies against the background of grain-market

liberalization in Europe.1

Understanding how grain policies evolved in the Ottoman

Empire is important for two reasons. First, the subsistence of the

masses in the Ottoman Empire, as in many other places, depended

Seven Agir is Assistant Professor of Economics, Middle East Technical University. She is the

author of "Empires Looking Seawards: The Benefits and Costs of Foreign Seaborne Trade,"

Journal of Mediterranean Studies, VI (2006), 1-18.

The author thanks Timothy Guinnane, Naomi Lameroux, Michael Cook, and Alex

Balistreri for their helpful comments and suggestions.

© 2013 by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and The Journal of Interdisciplinary

History, Inc.

i Douglas C. North, Institutions, Institutional Change, and Economic Performance (New York,

1990); Kenneth Pomeranz, The Great Divergence: China, Europe and the Making of the Modem

World Economy (Princeton, 2000); Jean-Laurent Rosenthal and R. Bin Wong, Before and Be-

yond Divergence: The Politics of Economic Change in China and Europe (New York, 201 1);

Prasannan Parthasarathi, Why Europe Grew Rich and Asia Did Not: Global Economic Divergence,

1600-1850 (New York, 201 1); Daron Acemoglu and James A. Robinson, Why Nations Fail:

The Origins of Power, Prosperity, and Poverty (New York, 2012).

Kivanç K. Karaman and Çevket Pamuk's study of the Ottoman fiscal centralization rela-

tive to that of other European states - "Ottoman State Finances in European Perspective,

1500-1914," Journal of Economic History, LXX (2010), 593-629 - represents a remarkable ex-

ception to the dearth of comparative analysis involving the Ottoman Empire. By studying the

evolution of the Ottoman taxation in a comparative framework, their study offered a fertile

ground for discussing the limits and potentials of Ottoman institutional change. Another ex-

ception is Timur Kuran's study of Islamic law - The Long Divergence: How Islamic Law Held

Back the Middle East? (Princeton, 2010) - which elaborated the observed differences in West-

ern and Islamic forms of economic organization. Although Kuran's work has spurred a well-

deserved interest among social scientists for Islamic legal institutions, many of its broad argu-

ments have not yet received critical examination. His claim that Islamic law was too rigid to

allow the emergence of corporations and accumulation of wealth, in particular, needs to be

scrutunized through both case studies and explicitly comparative works.

This content downloaded from

176.235.136.130 on Sun, 24 Mar 2024 12:11:13 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

572 I SEVEN AČIR

mostly on grain and grain products. Therefore, the nature and suc-

cess of redistributive policies concerning grain were directly tied

to the resilience of the political structure and the institutional ar-

rangements through which a multitude of interests interacted.

Hence, attention to Ottoman grain policies helps us to explore

particular characteristics of the Ottoman polity and how they

shaped its redistributive institutions. Furthermore, the centrality of

grain for subsistence and political stability implies relative homo-

geneity across different cases regarding corporate interests and in-

formation problems, making the grain sector a suitable subject to

explore in comparative perspective.2

Second, grain production was the backbone of agriculture,

and the role of government in grain markets has important impli-

cations for agricultural production and economic growth. Hence,

the interaction between the rules and regulations and the geo-

political and cultural context is pertinent to broad discussions

about the relationship between institutional change and economic

growth. More specifically, examining the evolution of govern-

mental regulation of the grain trade, with reference to both the

motives of policymakers and the effectiveness of the policies in a

particular historical context, sheds light on the different, and

sometimes contradictory, factors underlying the specific form and

degree of intervention.3

2 Edward P. Thompson, "The Moral Economy of the English Crowd in the Eighteenth

Century," Past & Present, 50 (1971), 76-136; Louise A. Tilly, "The Food Riot as a Form of

Political Conflict in France ," Journal of Interdisciplinary History, II (1971), 23-57; Charles Tilly,

"Food Supply and Public Order in Modern Europe," in idem (ed.), The Formation of National

States in Europe (Princeton, 1975), 380-455; Boaz Shoshan, "Grain Riots and the 'Moral

Economy': Cairo, 13 50-1 5 17," ibid., X (1980), 459-478.

3 Robert Fogel, The tscape Jrom Hunger and Premature Death, 1700-2100: hurope, America, ana

the Third World (New York, 2004); Karl G. Persson, Grain Markets in Europe 1300-1900: Inte-

gration and Deregulation (New York, 1999); Randall Nielsen, "Storage and English Govern-

ment in Early Modern Grain Markets, "Journal of Economic History, LVII (i997)> I- 33; Andrew

B. Appleby, "Grain Prices And Subsistence Crises in England and France, 1 590-1 740," ibid,.

XXXIX (1979), 865-887. Although this literature mosdy emphasized the "uniformity of the

European experience," it also instigated an interest in the development of grain markets in

other places, such as China and India (Persson, Grain Markets, xv). Lillian M. Li, "Integration

and Disintegration in North China's Grain Markets, 1739-19 11 "Journal of Economic History,

LX (2000), 665-699; Roman Studer, "India and the Great Divergence: Assessing the

Efficiency of the Grain Markets in Eighteenth- and Nineteenth-Century India," ibid.,

LXVIII (2008), 393-436; Carol H. Shiue and Wolfgang Keller, "Markets in China and Eu-

rope on the Eve of the Industrial Revolution," American Economic Review, XCVII, 1189-1216;

Enrique Llopis Agelán and Miguel Jerez Mendez, "El mercado de trigo en Castilla y León,

1691-1788: arbitraje espacial e intervención," Historia Agraria, XXV (2001), 13-68.

This content downloaded from

176.235.136.130 on Sun, 24 Mar 2024 12:11:13 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

OTTOMAN GRAIN ADMINISTRATION | 573

During the second half of the eighteenth century, most gov-

ernments in Europe attempted to remove age-old restrictions on

their grain trade and to establish free domestic markets. Although

policymakers did not necessarily concur about what would consti-

tute the appropriate degree and timing of liberalization, a general

re-orientation among those who wrote about the issue is clearly

noticeable: They presented a free domestic grain market as both a

better alternative to traditional policies in meeting the needs of the

urban masses and a necessary condition for agricultural growth and

international competitiveness. Ottoman grain markets, however,

remained mostly outside this literature. In line with the conven-

tional view that the Ottoman rulers had priorities different from

those of their European counterparts, traditional scholarship on

Ottoman grain markets in the eighteenth century has primarily fo-

cused on the increased involvement of government, arguing that

the policy changes were merely a response to the strains on the old

system of provisioning, driven by military and fiscal challenges.

This article presents a more complete account of Ottoman reforms

regarding the grain trade not only by using a larger range of

sources but also by focusing on a broad realm of ideas accompany-

ing the reforms.4

4 For the attempts at deregulation in the French grain trade (1763-1764), see Steven L.

Kaplan, Bread, Politics and Political Economy in the Reign of Louis XV (The Hague, 1976); in the

Austrian grain trade (1765-1786), Alexander Grab, "The Politics of Subsistence: The Liberal-

ization of Grain Commerce in Austrian Lombardy under Enlightened Despotism, " Journal of

Modem History, LVII (1985), 185-210; in Tuscany (1767), Mario Mirri, La lotta politica in

Toscana intomo alle 'riforme annonarie' (Pisa, 1972); in Sweden (1775), Karl Âmark, Spannmal-

shandel och spannmâlspolitik i Sverige, 1719-1830 (Stockholm, 191 5); in Spain, Jose U. Bernardos

Sanz, "Libertad e intervención en el abastecimiento de trigo a Madrid durante el siglo XVIII,"

in Brigitte Marin and Catherine Virlouvet (eds.), Nourrir les cités de Méditerranée: antiquité -

temps modernes (Paris, 2003), 367-388.

In this article, liberalization refers to policies aiming to reduce the direct involvement of

the state in the economy, such as abolishing trade barriers and price controls. In this sense, the

term implies neither an overall reduction in state activity nor the emergence of a " spontane-

ous w market order but an administered process best described as "(the) introduction of free

markets, [which,] far from doing away with the need for control, regulation, and interven-

tion, enormously increased their range" (Karl Polanyi, The Great Transformation [New York,

1944], 140-141).

The traditional historiography portrayed Ottoman political economy as fundamentally

different from that of its European counterparts. Recent historians, however, revised this bi-

nary view by underlining the parallels. For instance, Palmira Brummett, Ottoman Seapower and

Levantine Diplomacy in the Age of Discovery (New York, 1993), pointed to the "economic

intentionality" of the Ottoman state and the involvement of the Ottoman notable class in na-

val warfare. Kate Fleet, European and Islamic Trade in the Early Ottoman State: The Merchants of

Genoa and Turkey (New York, 1993), demonstrated the Ottomans' capacity and willingness to

This content downloaded from

176.235.136.130 on Sun, 24 Mar 2024 12:11:13 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

574 I SEVEN AGIR

The incipient liberalization that occurred almost simulta-

neously in various parts of Europe resonated with Ottoman re-

formers' ideas about (de)regulation of the grain trade. Along with

their establishment of a centralized administration to finance and

control a larger portion of the grain trade in 1790s, Ottoman

policymakers adopted a more liberal attitude toward price forma-

tion in grain markets and considered removing the pre-emptive

privileges held by government agents and licensed merchants. The

emergence of this more liberal attitude was not simply a result of

the Ottoman state's formal provisionist or fiscalist attempts to deal

with strains on the pre-existing supply network. Ottoman

policymakers also considered a relatively free interplay of market

forces in the grain trade to be a necessary condition for agricultural

growth and international competitiveness. Furthermore, as was

the case in the less-developed countries of the European conti-

nent, arguments for these policy changes reflected an attempt to

emulate more developed states.5

grain redistribution and price control Istanbul's grain sup-

ply was always an important concern for the Ottoman court.

In the mid-eighteenth century, the administration had already

adopted a variety of instruments along the commodity chain to

use their economic assets to strengthen their political position. Giancarlo Casale, "The Otto-

man Administration of the Spice Trade in the Sixteenth-Century Red Sea and Persian Gulf,"

Journal of the Economic and Sodai History of the Orient, XLIX (2006), 170-198, discussed the in-

novative strategies the Ottomans used to challenge the Portuguese monopoly over the spice

trade in the Indian Ocean. Similarly, by focusing on the relationship of the empire with the

fiscal elite, two works by Ariel Salzmann - "Privatizing the Empire: Pashas and Gentry during

the Ottoman 18th Century," in Kemal Çiçek (ed.), The Great Ottoman-Turkish Civilisation

(Ankara, 2000), II, 132-139, and Tocqueville in the Ottoman Empire: Rival Paths to the Modem

State (Boston, 2004) - pointed to a similar transformation in Ottoman and French fiscal prac-

tices and its accompanying changes in governance during the eighteenth century. All of these

studies attempt to place the Ottoman or Asian Empires within a broader framework that raises

comparative questions without assuming an essential difference between European and non-

European categories.

Rhoads Murphey, "Provisioning Istanbul: The State and Subsistence in the Early Mod-

ern Middle East," Food and Foodways (1988), II, 217-263; Tevfik Güran, "ístanbuTun

Ìa§esinde Devletin Rolii, 1793-1839," ístanbul Üniversitesi íktisat Fakültesi Mecmuasi, XLIV

(1988), 15-42; Lynn T. Çaçmazer, "Provisioning Istanbul: Bread Production, Power and Polit-

ical Ideology in the Ottoman Empire, 1789-1807," unpub. Ph. D. diss. (Indiana Univ., 2000).

5 For the Spanish case, see Agir, "From Welfare to Wealth: Ottoman and Castilian Grain

Policies in a Time of Change," unpub. Ph. D. diss. (Princeton Univ., 2009); for the Italian

case, John Robertson, "The Enlightenment above National Context: Political Economy in

Eighteenth-Century Scodand and Naples," The Historical Journal, XL (1997), 667-697.

This content downloaded from

176.235.136.130 on Sun, 24 Mar 2024 12:11:13 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

OTTOMAN GRAIN ADMINISTRATION | 575

ensure that the city's 400,000 inhabitants, a hotbed of social and

political upheaval, had access to an affordable and abundant food

supply. The key component of this redistribution was a system of

forced purchases - known as the comparative quota assessment

(mukayese nizamt) - in the zones designated as the official hinter-

land of Istanbul. This system was introduced to control the move-

ment of surplus grain from these regions. Through an investiga-

tion of Kapan (Istanbul's central grain market) registers, which

contained data about the amount of grain sent to the capital in

previous years, the authorities tried to determine how much sur-

plus each district was able to produce in normal years. According

to these estimates, each district was assigned a quantity to be deliv-

ered to a designated dock for sale to government agents or

officially authorized private merchants. The procedure for this lo-

cal distribution was vaguely defined; local agents were to assess and

collect the assigned quota for all of the households according to

"their condition and endurance capacity."6

Merchants could make purchases from the official hinterland

of Istanbul if they held long-term collective contracts with the

Kapan, which they acquired by providing a guarantee (kefalet) for

other merchants. These merchants of the Kapan enjoyed pre-

emptive privileges in the designated docks. The state also hired in-

dependent merchants or assigned its own requisition agents (muba-

yaact) to purchase grain to be stored at the Arsenal (Tersane), and it

sought to prevent entry of unauthorized intermediaries into the

grain trade by designating official docks for grain exchange and by

requiring local officials to keep registers about the quantity and

quality of the grain and the name of each ship owner.7

Various studies about the Ottoman control of the grain trade

reveal three broad features of the mid-eighteenth-century quota

system that paved the way for the subsequent policy changes: First,

6 For various estimates of Istanbul's population, see Giiran, "istanbul'un iaçesinde," 16, 20;

Engin Akarli, "Ottoman Population in Europe in the Nineteenth Century: Its Territorial,

Ethnic and Religious Composition," unpub. M.A. thesis (Univ. of Wisconsin, 1972). Lütfi

Giiçer, "XVIII. Yüzyil ortalannda ístanbul'un iaçesi için lüzumlu hububatin temini meselesi,"

istanbul Üniversitesi iktisat Fakültesi Mecmuasi, XI (1952), 397-416 (405-407 for the redistribu-

tion system); Salih Aynural, istanbul deģirmettleri ve finttlari (Istanbul, 2002), 5.

7 Gûçer, "XVI. Yüzyil Sonlannda Osmanli ímparatorlugu Dahilinde Hububat Ticaretinin

Tabi Olduģu Kayitlar," istanbul Üniversitesi iktisat Fakültesi Mecmuasi , XIII (1951/52), 1-20;

idem , 'istanbul'un ia§esi için lüzumlu hububatin temini,' 400, 403-404. The Grain Registers

(Zahire Defterleri) are located in the Prime Ministry Archives, Istanbul (hereinafter zd).

This content downloaded from

176.235.136.130 on Sun, 24 Mar 2024 12:11:13 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

576 I SEVEN AGIR

Istanbul's grain supply was procured primarily from regions within

the political realm administered by the Ottoman government. Ex-

amining the accounts of grain purchased and distributed from the

Kapan and the Tersane between 1755 and 1762, Aynural showed

that 85 percent of the grain sold at the Kapan was bought from the

Black Sea and the Danubian coasts. An investigation of the Grain

Registers, which contain a large number of orders sent to the

provinces, and various studies about Istanbul's provisioning cor-

roborate the primacy of the northwest littoral of the Black Sea and

the Danubian region in the grain provisioning of Istanbul during

this period. Second, according to the Kapan and Tersane records

summarized by Aynural, 93 percent of purchases were made by li-

censed merchants with their own capital. This finding is in line

with an earlier study by Giiçer, which shows that less than 9 per-

cent of grain was delivered to Istanbul using state funds. Third, the

negotiations between grain owners and intermediaries about the

price of grain were subject to official control, which aimed pri-

marily to ensure a low bread price in Istanbul.8

These three features of grain-trade organization in the mid-

eighteenth century had vanished by the last decade of the eight-

eenth century. But an understanding of how the main features of

the grain provisioning changed requires an understanding of how

the Ottoman administration tried to control the purchase prices.

The Ottoman government used two kinds of price control. The

miri (official) price was used in obligatory transactions between

grain-producing regions and the government. Each jurisdictional

unit was asked to deliver a certain amount of grain all at once, re-

gardless of the specific amounts that producers and grain holders

held. The miri price was much lower than the standing market

price. It was not adjusted according to the vicissitudes of supply -

8 Aynural, istanbul degirmenleri, 63-64; ZD 11, 13. See also Maria M. Alexandrescu-Dersca,

"L'approvisionnement d'Istanbul par les Principautés roumaines aux XVIIIe siècle: commerce

ou réquisition," Revue du Monde Musulman et de la Mediterranée, LXVI (1992), 73 - 7^; Eyüp

Özveren, "Black Sea and the Grain Provisioning of Istanbul in the Longue Durée," in

Brigitte Marin and Catherine Virlouvet (eds.), Nourrir les cités de Méditerranée: antiquité - temps

modernes (Paris, 2003), 223-250, 228; Robert Mantran, XVII. Yiizyihn ikinci Yartstnda istanbul:

Kurumsal, îktisadi, Toplumsal Tarih Denemesi (Ankara, 1990), 175, 182; Giiçer, "Hububat

ticaretinin tâbi olduģu kayitlar," 87; Bruce McGowan, "The Middle Danube cul-de-sac," in

Huricihan Ìslamoglu-Ìnan (ed.), The Ottoman Empire and the World-Economy (New York,

1987), 13; Feridun Emecen, "XVI. Asnn ikinci yansinda istanbul ve saraym ia§esi için Bati

Anadolu'dan yapilan sevkiyat," Tarin boyunca istanbul semineri (Istanbul, 1989), 197-230, 199;

Giiçer, "istanbul'un ia§esi için liizumlu hububatin temini," 410; Mantran, istanbul, 174.

This content downloaded from

176.235.136.130 on Sun, 24 Mar 2024 12:11:13 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

OTTOMAN GRAIN ADMINISTRATION | 577

no bargaining was involved - and the price remained constant for

long stretches of time.9

The other type of price set in the grain trade was the rayic -

literally, "current price" - which was supposed to be adjusted reg-

ularly according to supply conditions. For each locality in which

licensed merchants or requisition agents bought grain that was in-

tended ultimately for Istanbul, the rayic price was set through a

bargaining process in which local administrators could intervene

to keep prices at acceptable levels and to prevent delays in deliv-

ery. Although price setting between grain owners and officially

authorized intermediaries was based on a principle of "mutual

consent," the fact that grain owners could sell only to agents au-

thorized by the central administration invalidated the principle in

practice. Numerous official documents in which authorities ex-

plicitly mentioned the gap between the rayic price and that offered

by smugglers substantiate the supposition that the rayic price was

set below the market price.10

Price controls in the quota system functioned as an in-kind

tax on grain owners, exercised through monopsonistic control

over the grain supply. By controlling the sale price of grain in Is-

tanbul, however, the administration tried to restrict the monop-

sony rents of the licensed merchants by transferring these rents

from the merchants to the consumers and thereby gaining a lower

price for consumers. This result emanated from the regulation of

the baking/milling sector and the designation of the bakers' guild

as the sole customer for the grain brought to the city. The licensed

merchants had to deliver the grain that they had purchased to the

9 Various documents in the Kamil Kepeci collection (hereinafter kk) and the Mevkufat col-

lection (hereinafter d.mkf) in the Prime Ministry Archives, Istanbul, provide information on

the purchasing price of grain. In both kk 5577 (1809-11) and d.mkf 30528 (1770-73), miri

price per kile was recorded as 60 para (1.5 guru§)' rayic price (see next paragraph) was around 2

to 3 guru§. The kile was an Ottoman unit of volume. As a measure of weight, the standard kile

was equivalent to 25.65 kg. Gurus was the Ottoman silver coin.

10 See ZD 19 (158/1) (1795) for a case of bargaining over rayic price. See also Osman Nuri

Ergin, Mecelle-i umur-t belediyye (Istanbul, 1995), 380; Ahmet Akgündüz, Osmanli

kanunnâmeleri ve hukukí tahlilleri (Istanbul, 1990), 371. zd 13 (1778); zd 19 (1745(95). See also

Giiçer, "Istanbul'un iaçesi için lüzumlu hububatin iemini," 401; zd 19 (i 794-1 795); Aynural,

istanbul deģirmenleri, 40-42; Ceyhun Orhonlu, "Osmanli teçkilatina aid kiiçûk bir risale:

Risale-i Terceme," Beigeler, IV (1965), 39-48. The documents do not usually specify who the

smugglers were; they report only that the smugglers were active in certain regions and paid

such and such a price. Usually, smugglers bought the grain in coastal areas that were less su-

pervised and sold it mosdy to foreign ships, which offered a higher price. Smuggling was in-

deed dependent on an arbitrage window

This content downloaded from

176.235.136.130 on Sun, 24 Mar 2024 12:11:13 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

578 I SEVEN AGIR

Kapan, where they collectively negotiated with the bakers' guild

under the official supervision of a judge and Kapan officials. Guild

regulations forbade any new bakeries and mills from opening

without the permission of the administration. Furthermore, most

bakeries had their own mills; those that did not were assigned to

specific mills in their proximity. Because the import of flour to Is-

tanbul was forbidden, most of the grain brought to Istanbul ar-

rived unprocessed rather than as flour or bread.11

This formal organization of the baking industry served two

purposes: First, it enabled easier supervision of bread prices and

thus bakers' profits. Second, it improved bakers' bargaining posi-

tion with merchants by allowing them to haggle collectively over

input prices, thereby preventing the merchants from raising prices

to monopoly levels. Under these regulations, the bread price

could be officially determined according to the price of grain at

the Kapan, which depended on the local purchasing prices and

transportation costs. This maintenance of low purchasing prices

through monopsonistic control over the grain supply ensured the

affordability of bread in Istanbul.12

The effectiveness of this vertically integrated chain of controls

depended on the government's capacity to enforce barriers to en-

try. Purchasing prices lower than the market price would naturally

encourage smuggling and reduce the quantity of grain transported

to Istanbul below the amount that would be supplied without

price controls. The loss to smuggling would depend on the actual

capacity of the Ottoman administration to prevent smuggling. As

long as the effect of smuggling on Istanbul's supply and price of

grain was minimal, the controls could serve their purpose. Al-

though it is impossible to measure the exact effectiveness of price

controls as a spatial redistributive tool without information about

the quantities smuggled and the gaps between the market price

and the legal price, it is possible to discuss how the potential effec-

tiveness of the controls might have changed over time.

The effectiveness of the Ottoman controls over the grain

trade began to diminish toward the end of the eighteenth century

because of conjunctural changes in the grain market. Even though

li Ergin, Mecelle; Aynural, istanbul deģirmenleri, 59, 63-64, 88.

12 Keeping input prices low was one of the primary motives for instituting monopolies in

other markets as well. See Ergin, Mecelle, 649-650; Gabriel Baer, "The Administrative, Eco-

nomic and Social Functions of Turkish Guilds," International Journal of Middle East Studies, I

(1970), 28-50.

This content downloaded from

176.235.136.130 on Sun, 24 Mar 2024 12:11:13 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

OTTOMAN GRAIN ADMINISTRATION | 579

Ottoman economic historians are familiar with these changes,

they have made no attempt to assess their quantifiable effect on

grain markets. The quantitative and qualitative evidence to follow

complements existing studies, showing how the pressures on the

old system of provisioning affected the grain markets.

SUPPLYING ISTANBUL WITH GRAIN

In the middle of the eigh

tionally advantageous seab

importandy, to a vast reg

outside the Ottoman cor

Plain and the Black Sea co

plains of the Balkans, but

the peninsula served as barr

West. Moreover, the Ott

trade on the Black Sea; the shores of the Black Sea and the

lower Danube could be kept relatively safe from foreign demand

through controls on the Bosphorus Straits. Accordingly, the

northwest littoral of the Black Sea and the Danubian coasts were

the preferred sources for provisioning Istanbul. The coasts of west-

ern Anatolia were considered a secondary option. Only when the

shortage was severe did such farflung places as Kefe, Tripoli, the

eastern provinces, and Egypt (Istanbul's former grain depot) re-

ceive orders for grain dispatches.13

The political domination over a large surplus-producing re-

gion (the legal capacity to enforce export bans and internal barri-

ers) and the abundance of waterways and coasts (the cheapest way

to transport grain in the pre-industrial era) enabled the Ottoman

administration to create a large redistributive network that would

guarantee to Istanbul an affordable supply of grain. In order to

function, however, this redistributive mechanism necessitated an

elaborate network of intermediaries - including brokerage and pa-

tronage relations between different social actors - to control the

grain flow from the provinces to Istanbul. The rationale for policy

change was not founded on a simple state-society binary.14

13 Özveren, "Black Sea," 225, 228; Beydilli, "Karadeniz'in kapaliliģi," 687; McGowan,

"Middle Danube," 13, 14-15; Mantran, istanbul, 175, 182; Giiçer, "Hububat ticaretinin tabi

olduģu kayidar," 87-88; Alexandrescu-Dersca, "L'approvisionnement d'Istanbul"; Emecen,

"ístanbul ve sarayin ia§esi," 199; Kiitükoglu, "Osmanli íktisadi Yapisi," 569.

14 Overland transportation of grain for a distance of around 200 to 300 miles was more than

enough to double the price of grain, whereas overseas transportation accounted for 15 to 25%

of the purchase price of the grain shipped. See Giiçer, XVI-XVIIL Astrlarda Osmanli

This content downloaded from

176.235.136.130 on Sun, 24 Mar 2024 12:11:13 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

58o I SEVEN AGIR

Local intermediaries were needed, first and foremost, for their

knowledge of local precedures. Yet, the relationship that these in-

termediaries had with the central administration, as well as with

various local groups that did not share their social interests or bar-

gaining power, was not without friction. The incentives for the

officially assigned intermediaries to favor certain groups in the al-

location process and to collaborate with the local grain owners and

the merchants to misrepresent the volume of production and ship-

ment are obvious.15

Because it lacked a centrally organized and financed bureau-

cratic network in the provinces, the administration had to assign

local notables as the requisition agents with an active role in quota

allocation. Since many of these notables were themselves tax farm-

ers and landholders, their compliance with the official regulations

was in conflict with their interests as grain owners. Not surpris-

ingly, ample evidence suggests that they used their prerogatives to

further their own ends. In the context of this large network of in-

termediaries, controls could be effective only if the cost of smug-

gling (that is, the legal and natural deterrence of smuggling) ex-

ceeded the returns to smuggling (the gap between the official

price and the external price).16

The demographic and geopolitical changes of the last quarter

imparatorlugu'nda hububat meselesi ve hububattan altnan vergiler (Istanbul, 1964), 29; Aynural,

istanbul deģirmenleri, 25-26.

In one of the first environmental histories of the Empire, Alan Mikhail, Nature and Empire

in Ottoman Egypt: An Environmental History (New York, 201 1), demonstrates how imperial

initiative and a "coordinated system of local autonomy" interactively shaped the management

of natural resources in Ottoman Egypt. Particularly interesting is Mikhail's discussion of how

the emergence of a more centralized and authoritarian regime caused a decrease in Egyptian

rural autonomy during the late eighteenth century. The reform attempts discussed below at-

test to similar trends in the Ottoman central bureaucracy's relation to the Balkan provinces.

15 82 Numarah Mühimme Defteri 1026-1027/1617-1618 (Istanbul, 2000), 37; 05 rsumarali

Mühimme Defteri 1040-1041/1630-1631 (Istanbul, 2002) 134; ZD 19, 9, 82; Michael A. Cook,

Population Pressure in Rural Anatolia, 1450-1600 (New York, 1972), 55 Emecen, "istanbul ve

sarayin iaçesi," 203-204; Suraiya Faroqhi, "istanbul'un ia§esi ve Tekirdaģ-Rodoscuk limam,

16-17. yüzyillar," METU Studies in Development (1979/80), 139-154.

16 For the rise of ay an as provincial notables, see McGowan, The Age ot Ayans, 1699-

1812," in Halil inalcik and Donald Quataert (eds.), An Economic and Social History of the Otto-

man Empire, 1300-1914 (New York, 1994); Robert W. Zens, "The Ayanlik and Pasvanoģlu

Osman Pa§a of Vidin in the Age of Ottoman Social Change, 1791-1815," unpub. Ph. D. diss.

(Univ. of Wisconsin, 2004); Ali Yaycioglu, "The Provincial Challenge: Regionalism, Crisis,

and Integration in the Late Ottoman Empire, 1792-1812," unpub. Ph. D. diss. (Harvard

Univ., 2008). ZD 19, C. BLD. 841. See also Güran, "State Role," 24, 39; Aynural, istanbul

deģirmenleri, 24, 39; Yaycioglu, "Provincial Challenge," 250.

This content downloaded from

176.235.136.130 on Sun, 24 Mar 2024 12:11:13 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

OTTOMAN GRAIN ADMINISTRATION | 581

of the eighteenth century caused the incentives for smuggling to

increase during this period. On the demand side, the international

grain price was on the rise, creating upward pressure on the price

of grain smuggled from Ottoman lands to Western Europe. At the

same time, Istanbul's population was escalating as a result of migra-

tion from rural provinces struggling with social and economic

problems. The forced purchases, justified on the grounds of sus-

taining Istanbul's high population, were also a source of discontent

in the Balkans. As contemporaries observed, the growing pop-

ulation of Istanbul, induced by rural problems, augmented the

pressure on the traditional hinterland, further exacerbating rural

conditions and reinforcing migratory trends. The endogenous re-

lationship between redistributive policy and agricultural produc-

tion implied a gradual decrease in grain from the hinterland.17

Parallel to the changes in the demographic structure, the ca-

pacity of the government to enforce controls was decreasing be-

cause of political and military troubles in the regions providing

grain to Istanbul. Since the seventeenth century, the administra-

tion's gradual reorganization of state finances had been leading to

the spread of the tax-farming system and the rise of local notables,

complicating fiscal and administrative control over local resources.

Furthermore, the needs of the army had to be met by a frequent

recourse to emergency taxes, as well as such new fiscal instruments

as esham (a form of internal borrowing), which rendered rural in-

vestment unattractive. These long-term, incremental changes

might have had an adverse effect on both crop yields and domestic

market integration. Yet, without an analysis of long-term price se-

ries for a sufficient number of localities, it is not possible to deter-

mine the extent to which the institutional changes of the long

eighteenth century affected the Empire's supply base.18

Continuous wars on several fronts since 1768, however, had a

17 Ernest Labrouisse, Esquisse du mouvement des prix et des revenus en France au XVI I le siecle

(Paris, 1932), 598-603; Pierre Vilar, "Histoire des prix, histoire générale," Annales ESC, i

(1949), 29-45; McGowan, Economic Life, 121, 148; Süleyman Penah Efendi (transliterated by

Aziz Berker from the original, written c. 1769), "Mora ihtilali tarihçesi veya Penah Efendi

Mecmuasi," Tarih Vesikalart, II (1942/43), 230.

18 Inalcik, "Military and Fiscal Transformation in the Ottoman Empire, 1600- 1700,"

Archivům Ottomanicum, VI (1980), 283-337; Cezar, Osmanli maliyesinde bunalim ve deģiļim

dönemi (Istanbul, 1986); Linda Darling, Revenue-raising and Legitimacy: Tax-collection and Finance

Administration in the Ottoman Empire, 1360-1660 (Leiden, 1996). Mehmet Genç, Osmanli

imparatorluģu'nda devlet ve ekonomi (Istanbul, 2000).

This content downloaded from

176.235.136.130 on Sun, 24 Mar 2024 12:11:13 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

582 ļ SEVEN AČIR

distinct effect on Istanbul's grain supply. Territories in the Danu-

bian principalities were occupied by Austria and Russia for five-

year periods from 1769 to 1774 and from 1787 to 1892, causing the

disruption of the traditional grain routes feeding Istanbul. Further-

more, after military defeats led to the loss of Crimea and the partial

detachment of Wallachia and Moldavia, the Ottoman government

was deprived of its exclusive control of the Black Sea. The open-

ing of trade there saw the Ottoman and Russian grain produced

along its coasts inundate western Mediterranean markets. This de-

velopment was formally acknowledged in 1802 when the Otto-

man government began granting trade permits to foreign ships un-

der certain conditions.19

As a result of this severe geopolitical loss, the Mediterranean

coasts became more important for the provisioning of Istanbul.

Numerous official documents ordering substantial purchases from

southern Mediterranean ports after the 1790s demonstrate the sup-

ply zone's expansion southward. According to the 1794/9$ Grain

Registers, 70 percent of the wheat purchases for Istanbul - com-

pared to 1$ percent in the mid-eighteenth century - came from

the Mediterranean coasts. The accounts of the Grain Administra-

tion from 1795 to 1800, summarized by Güran, indicate that

66.4 percent of all grain coming to Istanbul was purchased from

the Mediterranean region. Since smuggling grain was much easier

from the Mediterranean coasts through the archipelago than from

the Black Sea area of present-day Bulgaria and Romania - in other

words, since the net incentives for not complying with the court's

orders were higher there - pre-existing policy tools would not be

as effective. The changing geopolitical context of Istanbul's grain

provisioning and the problems that it implied were also acknowl-

edged by Tatarcikzade Abdullah Efendi (d. 1797), one of the well-

known reformers of the period.20

19 A. Üner Turgay, "An Aspect of Ottoman-Russian Commercial Rivalry: Confiscation of

Ottoman Merchant Ships in the Black Sea," in Heath W. Lo wry and Ralph S. Hattox (eds.),

Proceedings of the II Congress on the Social and Economic History of Turkey (Istanbul, 199°)» 59~~

65 (60, for the implications of the Kûçiik Kaynarca Treaty for the grain trade); Gelina Harlaftis

and Sophia Laiou, "Ottoman State Policy in Mediterranean Trade and Shipping, c.1780-

C.1820: The Rise of the Greek-owned Ottoman Merchant Fleet," in Mark Mazower (ed.),

Networks of Power in Modem Greece : Essays in Honor of John Campbell (New York, 2008), 9- 11;

Kemal Beydilli, "Karadeniz'in kapalihgi karçisinda Avrupa kûçiik devletleri ve miri ticaret

te§ebbüsü," Belleten, LV (1991), 691-693.

20 The collections of Hatt-i Humayun (hereinafter hh), Cevdet Iktisat (hereinafter c. ikt),

and Cevdet Belediye (hereinafter c. bld) in the Prime Ministry Archives abound with docu-

This content downloaded from

176.235.136.130 on Sun, 24 Mar 2024 12:11:13 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

OTTOMAN GRAIN ADMINISTRATION | 583

Along with the shift in Istanbul's traditional hinterland, two

redistributive pillars of the quota assessment system - price con-

trols and forced purchases - became not just useless but counter-

productive. The government promulgated several decrees be-

tween 1774 and 1783 to abolish the quota system, claiming to

"end the oppression of the poor." The removal of the quota sys-

tem did not mean that exporting grain from these regions was al-

lowed; grain owners and producers were ordered to send their

surplus grain to Istanbul. Now, however, the quantities to be pro-

cured were bought direcdy from the grain owners, not assigned to

each administrative region. By abolishing the quota system, the

administration probably expected to reduce the role of the nota-

bles in the allocation process, prevent abuses, reduce corruption,

and thereby increase the amount of grain sent to Istanbul.21

The grain owners did not find these purchase prices accept-

able. In 1788, when requested to ascertain the reasons for scarcity

in Istanbul, the highest judge pointed to the price differentials be-

tween the supply zones and Istanbul's city market. The purchasing

price in Istanbul, he maintained, was much lower than the price in

the places where the grain was bought; this differential discour-

aged grain owners from bringing their grain to Istanbul. He sug-

gested that the purchasing price in the locations where the grain

was bought be raised. Likewise, a decree promulgated in 1789/90

attributed the low quality of bread to the scarcity of grain, which

also was considered the result of low purchasing prices. Eventually

in 1793, to encourage producers and grain owners to deliver more

grain to the authorized buyers, the Imperial Council ordered pur-

chasing prices to be set at the rayic price.22

ments concerning wheat smuggling along the Mediterranean coasts, hh 15/620, 29 Z

1203 [1789]; c.iKT 14/656, 18 C 1205 [22 02 1791]; c. BLD 4/177, 20 S 1209 [September 15,

1794]; C. BLD 38/1882, 19 S 1209 [15 09 1794]; C. BLD 28/1367, 20 Ç 1209 [l2 03 I795]; C. BLD

66/3256, 10 S I2I0 [2608 I795]; C. BLD 38/1887, 10 N I209 [31 03 I795]; C.IKT I3/638, 29 N

I2I0 [07 05 1796]; c. BLD 71/3527, 16 Ca 1217 [14 09 1802]; c.BLD 4/180, io S 1219 [May 20,

1804]; c.BLD 7/305, i R 1225 [May 5, 1810]; c. bld 58/2892, 10 Ca 1209 [03 12 1794]; c. bld

82/4097, 06 Za 1 22 1 [15 01 1807]; ZD 19. Güran, "Ìstanbul'un ia§esinde," 31. For Tatar-

cikzade's opinion of the grain trade in the Mediterranean region, see Ergin, Mecelle, 739.

21 ZD 13 (dated 1776), transcribed in Ergin, Mecelle, 739. Aynural, istanbul deģirmenleri, 11,

suggests that the system was abolished in 1783, and Alexandrescu-Dersca 'L'approvisionne-

ment d'Istanbul,' 76, in 1774. This confusion about when the quota system ended can be at-

tributed to the fact that the forced purchases continued even after the quota system was

removed. ZD 19 (1 794-1 795).

22 hh 23/1158, 1202 [1788]; hh 266/15437, 1204 [1790]. Güran, "State Role," 31. The

This content downloaded from

176.235.136.130 on Sun, 24 Mar 2024 12:11:13 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

584 I SEVEN AGIR

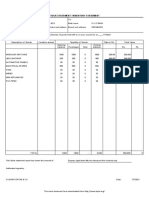

Table 1 Official Bread Prices in Istanbul, in Real Values

NUMBER OF

OBSERVATIONS AVERAGE PRICE

(FOR AVAILABLE PER KILOGRAM

YEARS PRICE DATA) (SILVER GRAMS)

1530-1642 (112 years) 37 0.524

1651-1724 (74 years) 8 0.508

1775-1819 (45 years) 33 0.638

I793~I8o5 (13 years) 9 0.782

source Values generated from the data compile

Wages (Ankara, 2001), 69-74, 102,106, no, 114, 1

of bread with the silver content of akçe and then

by dividing the price given in the Ottoman unit

kilograms). Data grouped according to the num

The increase in grain-purchase p

of the eighteenth century is also

fluctuations in bread and flour pr

they show that the average price o

significantly higher than the averag

vious century (see Table 1). Furthe

ratio for this period seems to be h

eighteenth century than the avera

the seventeenth century (see Table

the increase in the price of bread

bakers' profit margins. Thus, the i

pears to reflect an increase in grai

When the run-up in prices was n

supply in certain years, as was the c

Egypt, the Ottoman administratio

illegal grain imports by the baker

end of Ottoman-controlled self-suf

allowing higher prices in official

ports, the government took a mo

trade toward the end of the eight

was abolished in that same year wh

of policy, established the Grain Ad

sense of rayic in this context is "current," referrin

set through mutual consent in the marketplace.

not just any price emerging in the market.

This content downloaded from

176.235.136.130 on Sun, 24 Mar 2024 12:11:13 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

OTTOMAN GRAIN ADMINISTRATION | 585

Table 2 Flour Price-Bread Price Ratios in Istanbul

YEARS FLOUR PRICE / BREAD PRICE (%)

1623-1696 (9 observations) 64.69

1776-1829 (27 observations) 78.71

1793-1805 (8 observations) 77-47

source Values generated from the data compiled in Çevket Pa

Wages (Ankara, 2001), 69-74, 102,106, no, 114, 118, 122, 126, 1

of flour is used to make 1 km of bread and that the price data

medium quality of flour, whereas the bakers generally mixed

flour into bread. The percentage of the cost of flour used in mak

bul's grain supply. What motivated this pecu

problems, as opposed to the alternative solut

formers?23

reform of the public purchasing system D

of his reign, Sultan Selim III (r. 1789-180

council of dignitaries to discuss the future of

More than 200 members of the ruling class a

some of whom later submitted memoranda to the sultan contain-

ing their analyses of the Empire's main problems together with

their proposals for reform. The inherent drawbacks of the forced

purchasing system, specifically the abuses of the centrally autho-

rized intermediaries with their pre-emptive privileges, were among

the common themes. Tatarcikzâde Abdullah Efendi (d. 1797), one

of the high-ranking officials in the Ottoman judiciary, identified

the illicit acts of the requisition agents as the main source of the

trouble. He argued that these intermediaries tormented the peas-

antry to such an extent that the peasants had to abandon cultiva-

tion and migrate to other places.24

Despite his strong criticisms, Abdullah Efendi devoted para-

graphs to explain why, in spite of all its problems, the public pur-

chasing system had to be retained. He argued that its removal

would make it impossible to monitor and constrain the actions of

merchants, leading to an increase in profiteering. For instance,

merchants would be able to mix the high-quality grain produced

23 C. BLD 72/3551, 18 Za I2I2 [04 05 1798].

24 For a brief summary of Abdullah Efendi's memorandum, see Besim Özcan, "Tatarcik

Abdullah Efendi ve ìslahadarla ilgili layihasi," Türk Kültürü Ara§tirmalan) XXV (1988), 55-64.

Ergin, Mecelle, 739-742.

This content downloaded from

176.235.136.130 on Sun, 24 Mar 2024 12:11:13 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

586 I SEVEN AGIR

in the Mediterranean region with the lower-quality grain from the

Black Sea region and sell it for the higher price. His suggestion was

to set separate prices for grain purchased from each region - in

other words, to introduce price differentiation according to an

officially designated market segmentation. But he acknowledged

that the imposition of price controls for Mediterranean grain

would be difficult since smuggling from there was relatively easy.

But the alternative, the rescinding of all price controls, would gen-

erate a considerable rise in bread prices, which, in Abdullah

Efendi's view, was intolerable.25

The idea that the removal of price controls would lead to a

rise in bread prices indicates that price control was still considered

a feasible redistributive tool. But why did Abdullah Efendi believe

that the government-authorized agents were easier to control,

given that they, too, as he was well aware, engaged in smuggling

and hoarding? He might have assumed that the purchasing agents

were less inclined to violate the regulations because their assign-

ment as officially recognized agents included a host of local privi-

leges that they would not want to lose. Or, the center desperately

needed the locally acknowledged power and prestige of these in-

termediaries to determine and collect the surplus and thus prevent

the emergence of a black market, especially at a time when the ca-

pacity for central monitoring was limited.

Abdullah Efendi was not against price controls per se, but he

fervendy advocated an increase in purchasing prices. The low

prices, he maintained, threatened producers' livelihoods and

forced them to abandon their land, resulting in a perilous decline

in agricultural production. Accordingly, he proposed that all of the

grain coming to Istanbul should be purchased at the rayic price, set

through "free bargaining" and "mutual consent."

In his report, the Grand Vizier Koca Yusuf Pa§a also focused

at length on the abuses of the requisition agents assigned for grain

procurement. Supported by powerful political figures in Istanbul

and in the provinces, these agents took advantage of their privi-

leges by forcing the peasants to contribute more than their "just"

share or by paying them less than the "just" value of their grain.

Like Abdullah Efendi, however, Yusuf Pa§a did not consider abol-

ishing their agents' preemptive privileges as a viable strategy. In-

25 Ergin, Mecelle, 739-742.

This content downloaded from

176.235.136.130 on Sun, 24 Mar 2024 12:11:13 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

OTTOMAN GRAIN ADMINISTRATION | 587

stead, he described in detail how these agents should be chosen

and which rules and regulations should govern their actions.26

Yusuf Pa§a argued that if rules for the storage and transporta-

tion of grain could be imposed appropriately, grain could be

bought for a price even below the official price. To support his ar-

gument, he added, falsely, that the rayic price of grain produced in

the Black Sea littoral was already lower than its miri price and that

the rayic price in the Mediterranean zones could also be low if

smuggling could be prevented. Despite the feet that the Black Sea

rayic price was actually much higher than the miri price, the well-

known difference in quality between the Black Sea and the Medi-

terranean grains could have been a legitimate source of price

disparity, to which Yusuf Paja seemed oblivious. Furthermore,

frequent complaints about the reluctance or inability of the grain

owners in the Black Sea region to deliver the assigned quota

amount stand in contrast to his rosy portrayal of the purchasing

system.

Why would Yusuf Pa§a argue that prices could be easily

brought down if profiteering by public and private agents could be

prevented? As grand vizier, did he genuinely imagine that profi-

teering could actually be suppressed by supervisory measures,

without raising prices (or lowering incentives for smuggling)? His

solution might have reflected more a concern with the power of

the local notables who acted as intermediaries in the grain trade

than a realistic evaluation of the factors underlying the gap be-

tween real and desired price levels. Responding to the predica-

ment in which the Ottoman central administration found itself in

this era - the desire to curb the military and financial power of the

local notables while being unable to rule without their assent and

assistance - Yusuf Paça had no choice but to envision ways to

command purchasing agents.

The memoranda submitted by other Ottoman reformers to

the sultan also point to the intermediaries' abuses as one of the

main problems of the public purchasing system. Nevertheless,

only Mehmed Çerif Efendi suggested ending the entire practice of

public purchasing in grain market - after a one-time purchase for

emergency storage - on the grounds that eliminating the requisi-

26 Ibid, 739; Ergin Çagman, III. Selim' e takdim edilen layihalara göre Osmanli Devleti'nde

iktisadi deģi$me, unpub. M.A. thesis (Marmara Univ., 1995), 21.

This content downloaded from

176.235.136.130 on Sun, 24 Mar 2024 12:11:13 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

588 I SEVEN AGIR

tion agents would improve the links between the center and the

producing provinces, thereby stimulating agricultural production.

§erif Efendi's subde emphasis on the significance of unhindered

commercial linkages between the provinces and the center for the

development of agriculture is remarkably similar to the Physio-

cratic view that domestic free trade in grains would benefit

agricultural production. Yet Çerif Efendi stood alone among the

Ottoman ruling elite in his unreserved critique of the public

provisioning system.27

Most reformers seem to have believed that removing the

abuses in the system would be sufficient to ensure the well-being

of the peasants and eliminate disincentives for agricultural produc-

tion. Insistence on the forced purchases implied that the center

would continue to authorize use of the local allocation mechanism

to prevent the free movement of grain. The assumption was that

when merchants operated freely according to their economic in-

centives, grain prices would rise even above the levels that were

sufficient to sustain agricultural producers.

The trade-offs faced by the Ottoman reformers, as they per-

ceived them, were not different from those faced by their Euro-

pean counterparts. Like Pedro Rodríguez, Conde de Campo-

manes (d. 1802), in Spain or Anne-Robert-Jacques Turgot, Baron

de Laune (d. 1781), in France, Ottoman bureaucrats such as Ab-

dullah Efendi and §erif Efendi viewed systems based on either

private merchants or officially authorized intermediaries as "im-

perfect alternatives. " The rationale behind the administration's de-

cision to retain the public purchasing system, albeit reluctandy, has

to do with the peculiar institutional characteristics of economic

organization along the Ottoman commodity chain. At first glance,

however, the inability of the central Ottoman administration to

manage provisioning without involving local notables seems to be

one of the reasons for the requisition agents' continued presence

in the provisioning network.28

27 Ahmet Ögreten, Nizam-i Cedid'e dair islahat layihalart, unpub. M.A. thesis (Istanbul

Univ., 1989); Çagman, "Osmanli devletinde iktisadi degi§me," 217-233.

28 The question of how different interest groups (merchants and agricultural producers)

might have influenced the positions of the authorities and their reform proposals is also

significant for understanding the dynamics of Ottoman institutional change, engaging with

recent literature about the relationship between institutions' characteristics (extractive or

efficiency-enhancing) and political power. See North, John J. Wallis, and Barry R. Weingast,

Violence and Social Orders: A Conceptual Framework for Interpreting Recorded Human History (New

This content downloaded from

176.235.136.130 on Sun, 24 Mar 2024 12:11:13 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

OTTOMAN GRAIN ADMINISTRATION | 589

Ultimately, the government elected to retain the purchasing

system but sought to support producers and stimulate agriculture

by allowing the rayic price to prevail in purchases. Price controls

were lifted in the same year as was the license requirement to sell

grain in Istanbul. Grain owners could then bring grain wherever

they wanted and ask any price that they wanted and that the mar-

ket would bear.Transactions could take place outside of the

officially designated marketplace. Meanwhile, the government be-

came more active in the grain trade, in 1793 abolishing the miri

price and establishing the Grain Administration to regulate Istan-

bul's grain supply. Its aim was to keep at least 2,000,000 kile

(51,308 tons) of grain in state storage. Given an estimate of Istan-

bul's annual grain requirement at that time as around 4,000,000

kile (102,617 tons) per year, the government's intended supply

would have accounted for half of it. Given that the state was able

to store only a forty-day supply in its granaries at the start of the

century, its plan represented a major increase in its capacity for

storage.29

It took almost two years before the administration had the

fiscal capacity to pursue its goal. In 1795, an independent budget

(Zahire Hazinesi) was designed to finance the operations of the

York, 2009); Daron Acemoglu and James A. Robinson "Persistence of Power, Elites, and In-

stitutions," American Economic Review, XCVIII (2008), 267-293.

29 HH 225/12550B, I212 [1798]; HH 7/1853» 29 Z I215 [13 05 1801]; HH 7906 (1210)

[1795/6]. Yavuz Cezar, "Osmanli Devleti'nin mali kurumlanndan Zahire Hazinesi ve 1795

(1210) tarihli nizamnamesi," Toplum ve Bitím, VI (1978), 119, refers to hh 13951. Güran,

"State Role," 29, refers to mad (Maliyeden Müdewer Collection), no. 8591, 4-5, 19 03 1208

[25 10 1793]. Both documents are marked "in repair," and not currently open to researchers

in the Prime Ministry Archives. The tasks of the Grain Administration as defined by the by-

laws issued in the same year were summarized by Güran, "ístanbul'un iaçesinde," 17-18.

Aynural, ìstanbul deģirmenleri, 4, bases his estimate of the annual amount of grain needed in Is-

tanbul on the grain distributed from Kapan and state storages to bakers between 1756 and

1762. He supports it with reference to the number of milling stones in the city. Güran,

"Istanbul'un iaçesinde," 16, however, estimates Istanbul's annual wheat consumption to be

3.6 million kile (92,400 tons), based on the assumptions of each person requiring 8 kile

(201 kg) of wheat per year, and the population of Istanbul being 450,000 in the 1830s. He sup-

ports this estimation with an account from Cevdet Pa§a, who records the grain requirement of

the city at around 3 million kile when the Grain Administration was established. See Cevdet-i

Tarih (Istanbul, 1891/92), VI, 95. The estimate of 4 million kile takes into consideration that

Istanbul's population rose significantly between 1750s and 1790s and that Aynural overesti-

mates the grain need of the city by assuming that milling/baking facilities operated at full

capacity. Murphey, "Provisioning Istanbul," 231. Based on Aynural's data in Ìstanbul deģir-

menleri, 63-64, the average amount of grain distributed from the state storages between 1755

and 1762 was around 7% of the total.

This content downloaded from

176.235.136.130 on Sun, 24 Mar 2024 12:11:13 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

590 I SEVEN AČIR

Grain Administration. From 1795 to 1800, the average annual

amount of grain distributed by the Administration was approxi-

mately 1,000,000 kile (27,987 tons), almost one-third of the city's

annual grain consumption. Although this amount was below the

officially stated objective, it was three times the annual average

amount distributed by the state granaries from 1755 to 1762. As

such, the Administration became the major grain merchant in the

capital, selling the largest portion of the grain needed for Istanbul

at fixed prices to bakers.30

The Grain Administration statute book reconfirmed the abo-

lition of the official price of grain and ordered all purchases to be

made at the rayic price, the preference for which, along with the

earlier decrees abolishing the quota system, implied that grain

would be bought directly from grain owners. Archival evidence,

however, shows that the Administration continued to assign

lump-sum quantities for some regions despite ending the quota

system. It also undertook a more active role in the local allocation

process, especially in Macedonia, where smuggling was more

difficult to prevent for geographical reasons. Numerous orders in

the Grain Registers during this period instructed requisition agents

to purchase grain at the rayic price, specifying the names of the

wealthy grain owners and the amounts assigned to each of them.

Furthermore, the administration tried to increase its control over

requisition agents by auditing accounting registers and replacing

in-kind payments with salaries, which would allow it to forge a

long-term financial relationship with intermediaries.31

Although some of these policy changes were reversed during

the turbulent reign of Selim III in second half of the eighteenth

century (the quota assessment system was reintroduced in 1807,

along with purchases made at the miri price), Ottoman policy-

makers increasingly emphasized the benefits of higher prices and a

less coercive attitude in setting prices, as well as tighter regulation

and supervision of the grain-trade network and a more direct in-

30 Cezar, "Zahire Hazinesi," 122, 125; Giiran, "Istanbul' un ia§esinde devletin rolli," 31;

Aynural, ìstanbul deģirmenleri, 63-64.

31 Cezar, "Zahire Hazinesi,' 141, 149. For a few examples of these lump sums, see ZD 19,

orders 27/1, 29/1, 108/2, 109/1; ZD19, orders 19/1, 43/1, 54/1, 58/1; Antonis Anastaso-

poulos, " Karafery e (Veroia) in the 1790s: How Much Can the kadi sicilleri Tell Us?" in idem

and Elias Kolovos (eds.), Ottoman Rule and the Balkans, 1760-1850: Conflict, Transformation, Ad-

aptation (Rethymno, Crete, 2007), 45-59 (52, for the local judicial registers that demonstrate

how the system worked in Karaferye). kk 2959 confirms this policy change.

This content downloaded from

176.235.136.130 on Sun, 24 Mar 2024 12:11:13 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

OTTOMAN GRAIN ADMINISTRATION | 591

volvement in the grain market. These seemingly contradictory

policy changes could conceivably be explained, at least in part, by

(1) the expansion of the supply zone toward the Mediterranean

coasts, which implied higher purchasing prices because of the

steeper transportation costs; (2) the government's greater invest-

ment in policing; and (3) the increased prices offered to grain

owners in these regions. A concern that these higher prices would

elevate bread costs could have motivated the government to con-

trol a larger share of grain trade destined to Istanbul. This theory,

however, does not fully capture the forces shaping the changing

attitudes of the Ottoman administration. The newly emerging

concern for improving the productive base of the country and the

willingness to emulate policies in Europe were also involved in

these policy proposals.32

EUROPE AS A MODEL FOR THE OTTOMAN POLITICAL ECONOMY In

the last quarter of the eighteenth century, agricultural production

was becoming an increasing economic concern among the Otto-

man reformist elite, who were eager to emulate "more devel-

oped" states. The emergence of a position that was more tolerant

of higher consumer prices should also be seen within this context.

Reformers observed that a multitude of economic, politi-

cal, and military factors - including forced purchases and price

controls - were causing the impoverishment of the peasants, the

emigration of former proprietors, and the desolation of the lands

in the Ottoman Balkans. To encourage rural re-population and

agricultural output, which were considered the basis of political

32 Güran, "istanbul'un iaçesinde devletin rolü," 21. The Administration continued to use

pre-emptive privileges and miri prices, albeit with reserve, until after the Ottoman-British

Commercial Treaty of Baltalimam (1838). Evidence about how the city's population reacted

to these manipulations in the grain price is sketchy. Although few references to grain riots ex-

ist in the Ottoman context, the scarcity and low quality of bread probably constituted a threat

to public order. Indeed, Sultan Selim III, who established the Grain Administration to deal

with the problems surrounding the grain supply, lost his throne after a popular revolt that in-

cluded among its grievances the low quality of bread. See Aysel Danaci Yildiz, "Vaka-yi

Selimiyye or the Selimiyye Incident: A Study of May 1807 Rebellion," unpub. Ph.D. diss.

(Sabanci Univ., 2008), 723, which refers to one of the riot's leaders displaying a loaf of low-

quality bread as a symbol of the gap between the poor and the elite. Although the records fail

to show any incidents in which the rural population opposed the movement of grains out of

their communities, local unrest (to which the frequent complaints about purchasing agents

may well testify) could have played a role in the redesign of the grain policy, indicating paral-

lels with the French case that Charles Tilly discussed in The Vendée: A Sociological Analysis of

the Counter-Revolution of 17Ģ3 (New York, 1976).

This content downloaded from

176.235.136.130 on Sun, 24 Mar 2024 12:11:13 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

592 I SEVEN AČIR

and military stability as well as the only remedy for the overpopu-

lation of Istanbul, they advocated policy measures such as raising

grain prices and reducing compulsory procurement quotas.33

The suggestions of the memoranda writers, however, were

not limited to removing such disincentives to agricultural produc-

tion as forced purchases or low purchase prices. Ebubekir Ratib

Efendi - ambassador to Vienna in 1791 and, later, the first head of

the Grain Administration - depicted the lamentable state of agri-

culture in the Ottoman regions relative to what he saw in Europe.

In his view, the problems did not arise from natural conditions of

agricultural production; the Ottoman lands were more fortunate

in their natural resources than other places. He gave a detailed ac-

count of how Austria's emperor and the local authorities encour-

aged agricultural production by distributing land and equipment

to farmers and granting them temporary tax exemptions. He also

noted that Austria had no official purchasing agents who could

force owners to sell their grain at low prices or confiscate their

grain, thus removing the motivation for hoarding; consenting

producers and grain owners sold their entire surplus for the cur-

rent price. Describing how freedom in grain trade ensured abun-

dance in Austria, Ratib Efendi linked the ease with which the state

agents were able to procure goods and collect taxes to the welfare

of the subjects and the freedom that they had over the use of their

commodities: "No one intervened with what they produced or

consumed. "34

Ottoman concern with the economic policies of other states

was by no means confined to the agricultural realm. Economic

factors underlying the wealth and power of other states became

the subject of intense interest and purposeful inquiry among the

Ottoman elite during this period. In a treatise submitted to the

Sultan in 1803, Behic Efendi devoted a chapter on creating indus-

try in Ottoman realms, in which he used the notion of balance

33 For this issue, see Özcan, "Tatarcik Abdullah Efendi ve ìslahatlarla ilgili layihasi," 55-64;

Ergin Çagman, "III. Selim'e sunulan bir ìslahat raporu: Mehmet Çerif Efendi Layihasi," Di-

van, VII (1997), 217-233. See also Penah Efendi, "Penah Efendi Mecmuasi," 230.

34 Ebubekir Ratib Efendi (ed. and transliterated by S. Ankan from the original, written in

1793), "Nizâm-i Cedîd devri kaynaklanndan Ebubekir Ratib Efendi'nin büyük layihasi,"

unpub. Ph. D. diss. (Istanbul Univ., 1996), 412, 413-415. The reference to European practices

in the proposals concerning agricultural production goes back to Penah Efendi. See Penah

Efendi, "Penah Efendi Mecmuasi," 339. Fatih Yeçil, "III. Selim döneminde bir Osmanli

Biirokrati: Ebubekir Ratib Efendi," unpub. Ph. D. diss. (Hacettepe Univ., 2002), 162, 197.

This content downloaded from

176.235.136.130 on Sun, 24 Mar 2024 12:11:13 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

OTTOMAN GRAIN ADMINISTRATION | 593

of trade to underline the significance of domestic production

for wealth creation: "Promoting various crafts to ensure self-

sufficiency is a condition for the augmentation of state power.

Producing an excess over domestic consumption to be exported,

on the other hand, enhances the glory and grandeur of the state.

Having recognized the importance of these principles, all Euro-

pean and Asian states try to produce as great a number of com-

modities as possible - even though they themselves do not need

these commodities - just in order to attract the wealth of other

countries and hence to make themselves wealthy."35

Wealth in this context seems to have been understood as "a

measure of relative might," an idea that resonates with the devel-

opmental discourse emerging in other national contexts. Although

Behic Efendi takes self-sufficiency as given, neglecting to differen-

tiate between countries by their divisions of labor and ranges of

manufactured goods, he demonstrates a robust understanding of

how less-developed industries could be promoted by government

policies. For instance, he argued for the protection of domestic

crafts from foreign competition until they were able to compete

themselves. Focusing especially on Russia, the Empire's primary

military rival, he offered specific ideas regarding how to encourage

the production of such skill-intensive commodities as textiles,

clocks, and paper. He advocated the importation of technological

expertise from Europe through such incentives as rewards and

patents.36

35 Beydilli, "Kiiçûk Kaynarca'dan Tanzimat'a ìslahat diiçiinceleri," ilmi Araçtimalar VIII

(I999)> 50-52, is the first to note Behic Efendi's emphasis on domestic industry and trade.

Behiç Efenci (ed. and transliterated by A. O. Çinar from the original, written in 1803),

Sevânihii'l-Levâyih, in Çinar, "Es-Seyyid Mehmed Emin Behic'in Sevanihíi'l-levayihi ve

Deģerlendirmesi," unpub. M. A. thesis (Marmara Univ., 1992), 67.

36 For an insightful study that demonstrates how the idea of economic emulation served as

a prism through which eighteenth-century ideas and reforms were shaped, see Sophus A.

Reinert, Translating Empire : Emulation and Origins of Political Economy (Cambridge, Mass.,

201 1). For other studies discussing the role of emulation played in Enlightenment economic

thought, see Gabriel Paquette, Enlightenment , Governance, and Reform in Spain and Its Empire

1759~ iSoS (Houndmills, 201 1); Hamish M. Scott, Enlightened Absolutism: Reform and Reformers

in Later Eighteenth- Century Europe (Ann Arbor, 1990); Keith Tribe, Governing Economy: The

Reformation of German Economic Discourse, 1750-1840 (New York, 1988). An excerpt from

François Veron de Forbonnais, Elements du commerce (Paris, 1754), known to have influenced

German cameralism, bears a striking similarity to Behic Efendi's comments: "The real wealth

of a state is the greatest degree of independence from other states with respect to its needs,

and the greatest superfluity with which it can export to them." Tribe, Governing Economy, 81,

67-71.

This content downloaded from

176.235.136.130 on Sun, 24 Mar 2024 12:11:13 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

594 I SEVEN AGIR

Behic's use of Russia as a comparative model attests to the

Ottoman elites' increasing concern with economic competition.

The rapid transformation of the Russian economy and society

during the reign of Peter the Great was not only remarkable but

also, in Behic 's view, imitable: The tsar examined the policies of

other states before encouraging skilled experts in the sciences and

crafts to come to Russia and train locals. If even the Russians, who

were as uncivilized as "wild animals" in Behic's view, could pros-

per "in less than a hundred years," the Ottomans could do even

better.37

Mustafa Rasih Efendi, the Ottoman ambassador to Russia,

had expressed similar ideas ten years earlier. The fact that Russia

could improve its international position through military and eco-

nomic reform within a short period of time (a "latecomer phe-

nomenon," as it would be defined in the literature of modern

development) should have made it a suitable model for the Otto-

man bureaucrats. These various examples indicate that emulation

itself - that is, a willingness to recognize and adopt the successful

policies and institutions of rival nations - became the object of

emulation for Ottoman reformers during this period. In this sense,

emulation does not simply mean copying. Like that of other coun-

tries with fledgling developmental agendas, the Ottoman's search

for models entailed both choice and synthesis, without doing away

with traditional political formulas. For instance, the fact that Aus-

tria and Russia, both regarded as threats to the Empire, rather than

France, its main political ally, constituted primary models for agri-

cultural and industrial policy indicates the extent to which the de-

sired reforms were implicated in the survival of state. Further-

more, as Behic Efendi emphasized, the precedent of Russia

proved that learning from more developed states within a short

period was both feasible and advisable.38

37 See Çinar, "Es-Seyyid Mehmed Emin Behic," 67- 68.

38 Y. Karakaya (transliterator from the original, written in 1793;. Mustata Kasin

Efendi'nin 1793 Tarihli Rusya sefaretnamesi," unpub. M.A. thesis (Istanbul Univ., 1996),

no- 112. For an earlier argument for emulation in the military realm, see Virgina H. Aksan,

"Ottoman Political Writing, 1768-1808," International Journal of Middle East Studies, XXV

(1993), 56, which refers to íbrahim Müteferrika's Usui ül-Hikem (173 1). Miiteferrika (d. 1745)»

the first Muslim to run a printing press in the Empire, cited the reforms of Peter the Great and

underlined the necessity to model the army after the organization of successful nations. The

emulative inclinations of the Ottoman bureaucrats can be traced back to the early eighteenth

century when the military superiority of rival states, in particular Russia, became a subject of