Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Psych Science

Uploaded by

Ngoc Hoang Ngan NgoCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Psych Science

Uploaded by

Ngoc Hoang Ngan NgoCopyright:

Available Formats

APA NLM

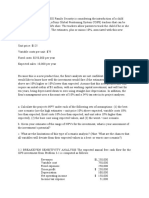

tapraid4/z2n-amepsy/z2n-amepsy/z2n00515/z2n4383d15z xppws S⫽1 5/19/15 7:41 Art: 2014-3568

“Everybody Knows Psychology Is Not a

Real Science”

Public Perceptions of Psychology and How We Can Improve Our

Relationship With Policymakers, the Scientific Community, and the

General Public

AQ: au Christopher J. Ferguson

This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

AQ: 1 Stetson University

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers.

In a recent seminal article, Lilienfeld (2012) argued that 2012), and similar outlets and may have contributed to

psychological science is experiencing a public perception reduced government funding of social science research

problem that has been caused by both public misconcep- (Stratford, 2014). Concerns about psychology’s status as a

tions about psychology, as well as the psychological sci- science come not only from among policymakers and the

ence community’s failure to distinguish itself from pop general public, but also from other areas of science (e.g.,

psychology and questionable therapeutic practices. Lilien- see Yong, 2012, and Wai, 2012, for several examples).

feld’s analysis is an important and cogent synopsis of Psychology’s status as a science is clearly not accepted as

external problems that have limited psychological sci- a given either among policymakers, the general public, or

ence’s penetration into public knowledge. The current ar- other scientists.

ticle expands upon this by examining internal problems, or The reasons for this are manifold, ranging from mis-

problems within psychological science that have poten- perceptions of psychology among the general public, the

tially limited its impact with policymakers, other scientists, continued popularity of psychological myths, the visibility

and the public. These problems range from the replication of therapeutic techniques with poor empirical support, and

crisis and defensive reactions to it, overuse of politicized lack of clear delineation between pop psychology and

policy statements by professional advocacy groups such as research psychology (Lilienfeld, 2012; Lilienfeld, Lynn,

the American Psychological Association (APA), and con- Ruscio, & Beyerstein, 2009). These are all external prob-

tinued overreliance on mechanistic models of human be- lems, although they might be exacerbated by issues such as

havior. It is concluded that considerable problems arise psychological researchers’ reluctance to engage the public

from psychological science’s tendency to overcommunicate (Lilienfeld, 2012; Weeks, 2005).

mechanistic concepts based on weak and often unrepli- In the current article, however, I discuss a slightly

cated (or unreplicable) data that do not resonate with the different issue, namely that some of the problem may be

everyday experiences of the general public or the rigor of self-inflicted from within psychological science itself, with

other scholarly fields. It is argued that a way forward can issues ranging from the replication crisis to an overselling

be seen by, on one hand, improving the rigor and trans- of psychological science, particularly on morally or cultur-

parency of psychological science, and making theoretical ally valenced issues to a mechanistic world-view that does

innovations that better acknowledge the complexities of the not speak to the complexities of the human condition.

human experience. Although a difficult topic to consider, I argue that psycho-

logical science, both theoretically and methodologically, is

Keywords: psychological science, replication, bias, public

perceptions not quite ready for prime time.

At the outset, however, I wish to be clear that although

T

my observations may be critical, they are offered with a

hat psychological science has struggled to find its

sense of optimism. Our field has much to offer, and the

voice among policymakers, other scientists, and the

desire among policymakers and the general public to un-

general public is an issue that is difficult to ignore.

derstand human behavior has never been greater. Reflec-

Those of us who are involved in psychological science

deeply believe in the scientific value of the study of human

behavior. But, on a fundamental level, many within other

fields of scholarship, as well as the general public, still I thank Moritz Heene, Rachel McNair, Emily W. Moore, and William

question whether psychology is a science at all. The ques- O’Donohue for comments on a draft of this article.

Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Chris-

tion of whether psychology is a “real” science is not just topher J. Ferguson, Department of Psychology, Stetson University, 421 N.

questioned among the masses, but has been debated in the Woodland Boulevard, DeLand, FL 32729. E-mail: CJFerguson1111@

New York Times (Gutting, 2012), L.A. Times (Berezow, aol.com

Month 2015 ● American Psychologist 1

© 2015 American Psychological Association 0003-066X/15/$12.00

Vol. 70, No. 5, 000 http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0039405

APA NLM

tapraid4/z2n-amepsy/z2n-amepsy/z2n00515/z2n4383d15z xppws S⫽1 5/19/15 7:41 Art: 2014-3568

with scientific rigor. I argue that collectively the nature of

these issues damages the credibility of our science in the

eyes of others. Similarly, they have in common that they

are self-inflicted rather than externally inflicted. In the

spirit of Simmons, Nelson, and Simonsohn (2011), I will

note that I do not excuse myself from the various issues and

errors discussed within and believe most of the issues are

those of good-faith human nature. I hope that this essay

will spark an understanding that we can all improve and we

can work together to make our science better. With that

qualifier, I turn first to methodological issues.

Methodological Issues

This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers.

In this section, I address methodological pitfalls for the

field of psychology that have potentially reduced confi-

dence in the reliability of the field among policymakers,

other scientists, and the general public. By methodological

issues I do not necessarily refer to specific methodologies,

such as for laboratory studies, although these can be of

issue as well. For instance, the validity of laboratory studies

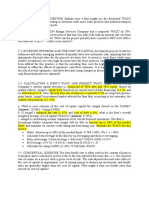

Christopher J. has often been debated, particularly in relation to their

Ferguson generalizability to real-life behaviors (e.g., Ritter & Eslea,

2005; Shipstead, Redick, & Engle, 2012; Wolfe & Roberts,

1993; although see Mook’s (1983) famous defense of “ex-

ternal invalidity”). This generalizability issue, although

tion, criticism, and remaking are part of science. With a

methodological in nature, actually goes to the marketing of

hard look at our field, I sincerely believe we can work

psychological science, particularly when artificial labora-

together to improve and reach our full potential as a sci-

tory studies are improperly generalized to the real world.

entific discipline.

The methodological issues I refer to here are not specific to

I note upfront that factors that influence policymakers,

individual studies, but refer instead to broad issues regard-

other scientists, and the general public as groups may vary.

ing the conduct of psychological science itself and how

For instance, it is doubtful that methodological issues such

these methodologies may influence perceptions by the gen-

as the replication crisis or psychological science’s aversion

eral public.

to the null are kitchen-table topics in the average house-

hold. However, such issues undoubtedly influence the opin- The Replication Crisis

ions of other scientists who may view our field as less

rigorous than hard-science fields such as physics, chemis- Roughly since the 2011 publication of an article suggesting

try, or biology. These opinions of other scholars may be that humans could foretell the future (Bem, 2011 and see

transmitted both to policymakers and the general public Wagenmakers, Wetzels, Borsboom, & van der Maas, 2011

through public comments, written editorials, and academic for comment), psychology has been gripped with what has

lectures to students. Furthermore, psychology’s internal been called a replication crisis. Replicability issues in

problems (e.g., the replication crisis, problematic policy science are neither new nor limited to psychology (see

statements) have received remarkable press coverage in Ioannidis’ (2005) famous essay on false positives in sci-

recent years (e.g., Berezow, 2012; Chambers, 2014; Firth ence). However, the publication of an article about ESP in

& Firth, 2014; Gutting, 2012; Hendricks, 2014), and some the top journal of social psychology arguably brought home

of this public discussion has arguably influenced decisions the likelihood that many other false-positive articles are

of policymakers regarding psychological science (Nyhan, being published but are not easily identifiable because of

2014). Citizens in the general public may remain unaware less fantastical subject matter. As such, several areas, par-

of the specific internal problems and controversies of psy- ticularly within social psychology, began to be identified as

chological science. Yet a pervasive stream of bad news and difficult to replicate ranging from social priming (Doyen,

negative comments from science journalists, policymakers, Klein, Pichon, & Cleeremans, 2012; Pashler, Coburn, &

and scientists in other fields will contribute to a more Harris, 2012) to media effects (Lang, 2013; Tear &

general negative impression of psychological science Nielsen, 2013) and embodied cognition (Johnson, Cheung,

among the general public. & Donnellan, 2014). This, in turn, led to public and highly

In this article, I will discuss three broad areas of acrimonious debates between the replicators and those

concern, namely methodological issues, theoretical issues, whose studies were not replicated about which much as

and the marketing of psychological science. These are a been written (e.g., Bartlett, 2014; Etchells, 2014) and ulti-

disparate range of concerns, but they have in common that mately invited unfavorable comparisons once again to the

they contribute to the perception that psychology struggles “hard” sciences (Chambers, 2014).

2 Month 2015 ● American Psychologist

APA NLM

tapraid4/z2n-amepsy/z2n-amepsy/z2n00515/z2n4383d15z xppws S⫽1 5/19/15 7:41 Art: 2014-3568

To be clear, the problem is not that some areas of erally assume that larger samples have smaller sampling

psychology have ultimately proven difficult to replicate. errors and thus more power to detect effects that are

This can happen in any field, but the replication crisis has assumed to be “true” rather than because of sampling

unveiled a surprising resistance to the concept of replica- error), or traditional “file drawer” issues in which null

tion within psychological science (Elson, 2014). For in- studies or results are simply not reported. Having larger

stance, with respect to the Bem (2011) precognition study standard errors, smaller samples produce more extreme

mentioned earlier, replication efforts were initially rejected effect sizes, and in the presence of publication bias,

by the editor of the publishing journal, with the replicating more extreme effect sizes that attain statistical signifi-

authors told that the journal “does not publish replications” cance are more likely to be published. Effect size is

(French, 2012). These included highly acrimonious ex- generally independent of sample size and thus the ex-

changes between scholars, even those not directly involved pected correlation between effect size and sample size

in the replication efforts, and essays by prominent scholars should be zero. A negative correlation between sample

(e.g., Mitchell, 2014) advocating that failed replications are size and effect size indicates that publication selectivity

This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

scientifically unworthy and should not be published. As

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers.

is at play, and samples that did not produce statistically

Elson (2014) notes, the replication crisis is not a crisis significant results are being declined from publication,

because some areas of psychology have not been repli- either by journals or because of authors’ practices them-

cated, but rather that the debate over replication has re- selves.

vealed an academic culture in which a central tenet of As Bakker, van Dijk, and Wicherts (2012) note that as

science, replicability, does not appear to be universally

many as 96% of publications in psychology provide data to

valued.

support the authors’ a priori hypotheses, a track record not

Aversion to the Null warranted by the statistical power of the studies involved.

Taken together, these results suggest a strong tendency

Related to the replication crisis is psychological science’s toward rejecting studies with null results or authors using

well-known aversion to publishing null results. Aversion to questionable researcher practices (described later) to con-

the null can occur both at the level of the editor/journal vert null findings to statistically significant findings, a

(publication bias) and because of authors who themselves tendency that is difficult to explain purely based on quality

suppress null findings for various reasons. The issue of differences in studies (e.g., Mitchell, 2014 and reply by

publication bias has been known for some time (Rosenthal, Neuroskeptic, 2014).

1979). Author-level suppression of null findings has re- The issue appears even in top journals. In a recent

ceived less attention and may occur because of perceived analysis of psychology articles appearing in the journal

difficulty in publishing null findings (e.g., Franco, Malho- Science (Francis, Tanzman, & Matthews, 2014), the au-

tra, & Simonovits, 2014; van Lent, Overbeke, & Out, thors found that the success rate for hypothesis tests as

2014), perceived difficulty in interpreting inconsistent re- indicated by achieving p ⫽ .05 was much greater than

sults when they occur (e.g., Crotty, 2014), and ideological would be expected given the power and design of the

biases because of theoretical rigidity or the perception that studies included. The authors concluded that approximately

positive findings would support an advocacy goal. It has

83% of published multi-experiment psychology articles in

become the culture of our field that either an empirical test

Science had suspicious statistically significant outcomes

provides evidence for a theory, or the empirical test failed

possibly indicating the presence of questionable researcher

(Schimmack, 2012). This is not an adequate scientific cul-

practices (QRPs), particularly tweaking statistical analyses

ture.

Like many of the issues described in this article, to achieve p values below .05 or suppressing inconvenient

aversion to the null is not unique to psychology, al- null findings. Thus, authors may feel pressure to achieve

though there is some evidence that it is particularly statistical significance in order to attain publication or to

common in behavioral and psychological science support beloved theories.

(Fanelli, 2010). The proportion of studies published in Arguments against publishing null results tend to ar-

psychological science that support the authors’ a priori gue either that null studies are of lower quality than statis-

hypotheses appear to be unusually high. For instance, tically significant ones (although see Neuroskeptic, 2014)

Fanelli (2010, p. 4) stated, based on his analyses of or that null results are more difficult to interpret owing to

published reports “. . . the odds of reporting a positive Type II error. Little evidence has emerged, however, that

result were around five times higher for papers published null studies are necessarily of lower quality, and low power

in Psychology and Psychiatry and Economics and Busi- causes unreliable results that may influence both null and

ness than in Space Science.” Fritz, Scherndl, and Küh- statistically significant studies. Or, put another way, if we

berger (2012) found that from 395 randomly selected can only publish statistically significant results and our

psychological studies, sample size correlated with effect statistics offer no road to falsification, the process we are

size at r ⫽ ⫺.46, typically an indication of “sample size engaged in is not scientific. This skew in publication prac-

chasing” (increasing sample sizes to just adequate size to tices results in research bodies that do not represent real-

obtain statistical significance for a given effect size) to world behaviors and may, in fact, be increasingly remote

achieve statistical significance (statistical analyses gen- from behavior in the real world.

Month 2015 ● American Psychologist 3

APA NLM

tapraid4/z2n-amepsy/z2n-amepsy/z2n00515/z2n4383d15z xppws S⫽1 5/19/15 7:41 Art: 2014-3568

QRPs 2014; Rouder & Morey, 2012), or greater emphasis on

outcomes such as effect size or confidence intervals, al-

Arguably, the incentive structure in psychological science though these too have the pitfalls. More recently one psy-

publishing, which values statistical significance and repu- chological journal, Basic and Applied Social Psychology,

diates falsification, results in pressure for researchers to has effectively banned null hypothesis significance testing

convert nonsignificant findings into statistically significant altogether (Trafimow & Marks, 2015). Not surprisingly,

ones (Nosek, Spies, & Motyl, 2012). Such an incentive this has created significant discussion and debate (e.g.,

structure coupled with a lack of standardization in methods, Haggstrom, 2015; Novella, 2015) because this represents a

data extraction and analysis, or data interpretation may major departure from business as usual regarding statistical

create a research scenario in which research results reflect analysis in psychology. Whether this effort truly develops

experimenter expectancies to a greater extent than they do into new thinking and greater rigor or simply greater cre-

real-life behavior (Klein et al., 2012). That is to say exper- ativity in producing false-positives remains to be seen.

imenters themselves, sometimes fraudulently, but more However, these efforts are certainly welcome and should

This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

often acting in good faith, may be able to “tilt the machine” be encouraged whether they ultimately succeed or fail.

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers.

to produce research results which reflect what they wanted

to see rather than what actually is. Lack of Transparency

This issue was prominently brought to light by Sim-

mons et al. (2011), who demonstrated that statistics can be It is often startling to outsiders to learn that psychological

potentially manipulated to produce statistically significant researchers are not required to submit datasets for review as

but absurd results. In one experiment, Simmons and col- part of the publication process nor are repositories of data

leagues demonstrated that, by manipulating statistical anal- kept for confirmation purposes. Although American Psy-

yses for an experiment using real data, they could make it chological Association (APA) ethics require researchers to

appear that listening to a Beatle’s song made participants maintain records for 5 years’ post publication and to pro-

chronologically younger, an obviously impossible out- vide those records to other scholars on request, enforce-

come. Using simulations, they further demonstrated how ment of this ethical principle is arguably spotty at best and

manipulating statistical designs could produce considerable dependent upon individual journals, which themselves may

spurious results. QRPs may include behaviors such as be reluctant to support a challenge to articles published in

stopping data collection only when statistical significance their pages. Some scholars (e.g., Wicherts & Bakker, 2009)

is achieved (i.e., sample size chasing), selecting from contend that revisions to the APA ethical code made data

among data analytic strategies those that produce statistical sharing less likely, mainly by allowing published authors to

significance and rejecting those that do not, extracting data place undue demands and restrictions on authors requesting

from individual measures in ways that maximize the like- data. Given that requests for data may be perceived as

lihood of statistical significance, convenient exclusion or “hostile,” there appear to be few incentives for scholars to

inclusion of outliers, convenient inclusion or exclusion of provide requested datasets and many incentives for them

covariates in statistical analyses, selective reporting of pos- not to, with the possible exception of their own personal

itive but not null results from studies with inconsistent consciences. More often than not, both the field of psycho-

outcomes, running multiple independent experiments but logical science and the general public has little recourse but

to take scholars at their word that their data says what their

only reporting those with significant results (something

articles say it does.

some scholars have publically admitted to), and so forth.

Previous studies have suggested that positive re-

Surveys of psychological researchers indicate that such

searcher responses to requests for data tend to be low,

behaviors are rather common (e.g., Fang, Steen, & Casa-

ranging from a low of about 27% (Wicherts, Borsboom,

devall, 2012; John, Loewenstein, & Prelec, 2012), although

Kats, & Molenaar, 2006) to a high of about 75% (Eaton,

most often in good faith rather than deliberately fraudulent.

1984). This higher figure was for summary statistics only

That is to say, researcher expectancies tend to direct re-

(data necessary to calculate effect sizes), however, not the

searchers to select from among multiple possible analytic

raw data. Most studies that have examined this issue have

strategies, those that produce statistically significant re-

found low compliance figures closer to Wicherts et al.

sults, while eschewing analytical strategies that produce

(2006) than Eaton (1984) (e.g., Craig & Reese, 1973; AQ: 2

null results. In some cases, research designs and statistical

Wolins, 1962). Wicherts, Bakker, and Molenaar (2011)

analyses may be selected specifically to offer maximal

noted that negative replies (or unresponsiveness) to re-

likelihood of support for a priori theoretical models or

quests for data were more common for articles published

hypotheses (Fiedler, 2011). Such approaches most often

with apparent statistical errors or other evidence method-

increase Type I error results and should not be applied. ological problems.

Several approaches and efforts have been put into

place to try to nudge the field away from these types of Methodological Problems: What Can

practices. These include a priori registration of research

designs through outlets such as the Open Science Frame-

Be Done?

work, in-principle acceptance of articles based on methods As noted earlier, the general public is unlikely to be watch-

and design before results are known, use of alternate sta- ing every aspect of psychology’s replication crisis and

tistical approaches such as Bayesian statistics (Dienes, attendant concerns regarding QRPs, transparency, and pub-

4 Month 2015 ● American Psychologist

APA NLM

tapraid4/z2n-amepsy/z2n-amepsy/z2n00515/z2n4383d15z xppws S⫽1 5/19/15 7:41 Art: 2014-3568

lication bias, although policymakers and other scientists are greater openness and transparency on the part of the re-

likely paying more attention. However, enough of this search community.

information has likely trickled down to the general public I advocate for a change of culture in psychological

to create the image of an investigative field that is defen- science because, at the moment, many scholars appear to

sive, ideologically rigid, nontransparent, and slippery in believe many of the issues I describe to be normative and

methodology. No field could survive such a public image acceptable. Such a change can be difficult and slow to

with credibility intact. achieve. However, one crucial effort in such a change

Fixing this requires several things related to increased would involve the training of graduate students. Graduate

transparency, as well as a cultural shift for the field. First, students in psychology and the social sciences need to be

and foremost, psychological science must repudiate its informed, most appropriately during the research methods

previous aversion to null results generally and failed rep- sequence, of the methodological issues in our field, includ-

lications specifically. The credibility of psychological sci- ing issues of replication, transparency, QRPs, and null

ence will not be restored until we are able to communicate aversion. How these issues detract from scientific progress

This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

our openness to ideas not working out, theories being should be openly discussed. Academic mentors can also

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers.

falsified and, in general, simply being proved wrong. For- demonstrate good scientific practices for students, promote

tunately, some positive steps are already being taken in this open science, and encouraging trainee scholars to embrace

regard. Psychological scholars are beginning to stress the and report research results whether they are theory confir-

importance of direct replications (e.g., Simons, 2014), and matory or not. The graduate school years are undoubtedly

journals such as Perspectives on Psychological Science are formative regarding the culture of academic science and

providing avenues for publishing direct replications. None- thus addressing and instilling good practices during grad-

theless, a more general aversion to the null likely remains uate training can be a powerful element of cultural change.

pervasive and will continue until psychological journals Addressing these issues in graduate training may not pre-

demonstrate a determinedness to publish null studies along- vent those determined to be fraudulent but may help reduce

side statistically significant ones, so long as those studies good-faith QRPs that may come across as business as usual

are of equal methodological merit. Opportunities are being in the current climate.

created for scholars to preregister their hypotheses and

methodologies in advance of data collection and articles Theoretical Issues

that avail themselves of these opportunities should be re-

In this section, I discuss several theoretical issues related to

inforced with particular consideration (Wagenmakers,

psychological science and its difficulty in speaking to the

Wetzels, Borsboom, van der Maas, & Kievit, 2012). Rep-

totality of human experience. Put simply, I argue that there

lication studies, both positive and negative, could be ex-

often exists a gulf between psychological science’s expla-

amined meta-analytically with preregistration status con-

nation for human behavior, which tends to be narrowly

sidered as a moderator to examine whether preregistration

focused, mechanistic, and rigid, and the lives people actu-

is likely to result in lower effect sizes.

ally live. This does not at all discount Lilienfeld’s obser-

As for data, it is understandable that an open posting

vation (2012) that people may often misunderstand psy-

of data to the general public may be precluded by a number

chological principles at work in their personal lives.

of ethical, practical, and proprietary concerns. However, it

However, I do argue that psychological science can some-

is argued here that raw datasets should be provided along-

times miss the forest for the trees and make assumptions

side articles to journal editors during the manuscript review

that the dubious effects seen under artificial laboratory

process. Many journals, including those of the APA and

conditions speak to real human experience. Thus, in this

Society for Personality and Social Psychology, have poli-

section I advocate for new and more complex theories of

cies that specifically require authors to share data with

human behavior.

other scholars. However, the degree to which authors com-

ply with these requirements or to which journal editors The Hammer Hypothesis

enforce them is unclear. If authors fail to share data, are

their articles retracted? By requiring authors to submit Psychological science sometimes has the tendency to over-

datasets to journals upon submission, these ambiguities can emphasize the impact of imitation and modeling and auto-

be avoided. Furthermore, journals should retain the sub- matic processes on human behavior. Since the 1960s, it has

mitted datasets for the required period of 5 years. In such been well understood that humans are capable of learning

cases that data are questioned, the journal could act as a through processes of imitation and vicarious reinforcement.

repository for the data in question and would be able to Indeed, the “Bo-Bo doll” studies of Bandura (e.g., Ban-

directly address concerns or possibly solicit statistical re- dura, 1965) are psychological science classics taught to

analysis if necessary. In accordance with APA ethics, jour- every introductory psychology student (although not be-

nals would be expected to release datasets to reasonable yond criticism; see Tedeschi & Quigley, 1996). In these

requests for reanalysis by other scholars. This may help to classic studies, children were randomized to watch an adult

reduce the impact of reluctant authors, although journals model either hit a Bo-Bo doll in a playroom or play

themselves may be reluctant to revisit previously published peacefully, were then frustrated, and finally given the op-

data. Although imperfect, this may be a crucial step to portunity to model the behavior in a similar playroom.

prevent disappearing datasets that would communicate Children who watched the adult actor engage in aggression

Month 2015 ● American Psychologist 5

APA NLM

tapraid4/z2n-amepsy/z2n-amepsy/z2n00515/z2n4383d15z xppws S⫽1 5/19/15 7:41 Art: 2014-3568

toward the Bo-Bo doll tended to imitate that behavior, process of data collection is a mere proforma one to support

particularly in conditions in which the model had been the theoretical model. Although theory in science is of

reinforced for the aggressive behavior. The amount of critical importance, it is understood that theories can at

research conducted on social learning theory is so numer- times obstruct scientific progress (Greenwald, 2012;

ous (a PsycINFO subject search for “social learning the- Greenwald, Pratkanis, Leippe, & Baumgardner, 1986).

ory” OR “social– cognitive theory” turned up over 1,500 This occurs when scholars become emotionally invested in

hits) that it would be difficult to summarize even in book a theoretical perspective. Inconclusive data may be inter-

form. preted as supportive of the theory and nonsupportive data

Nonetheless, public discussions of imitative behavior, ignored, criticized, or suppressed.

either between scholars or to the general public, too often Theoretical rigidity can lead to “scientific inbreeding”

come across as simplistic. Rather than a useful tool that and obligatory replication in which the replication process

people can use to learn useful skills or behaviors, imitation is subverted to provide support for a given theoretical

is often presented as something people, particularly chil- model rather than to seriously test whether it is falsifiable

This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

dren must do (e.g., Heusmann & Taylor, 2003) and in (Ioannidis, 2012). Defenders of a given theoretical model

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers.

which automatic and senseless responding to even subtle may engage in same-team replications, and (whether pur-

stimuli has been emphasized (e.g., Bargh, & Chartrand, posefully or not, such as through peer review of journal

1999). Some scholars may acknowledge the complexities articles) put pressure on other scholars to produce similar

involved given multiple potential models in a person’s life results (possibly through QRPs or publication bias; see

(e.g., Kazdin & Rotello, 2009), yet modeling is still often Shooter, 2011). The result is a fairly common pattern:

discussed as a powerful, overweening and automatic theory-glorifying literature that can stretch for years or,

(rather than chosen) force for shaping behavior. sometimes, decades, only to come under considerable

I refer to this as the Hammer Hypothesis (in the sense doubt once more skeptical scholars attempt replication

of, if the only tool you have is a hammer, everything begins (Coyne & de Voogd, 2012).

to look like a nail) in that psychologists may overempha- Rather than a constant eye at testing theoretical mod-

size the power and, perhaps more importantly, automaticity els with falsification at the forefront, the result is often

of modeling because social learning theory is the major, theoretical “camps” of defenders and supporters who can

unique, contributing body of work that originated specifi- become acrimonious (examples of this in psychological

cally from within psychology to explain human behavior. literature are numerous enough that any reader should have

The critique here is not to suggest that modeling does not little difficulty finding them). In particular, advocates of

occur (which would be absurd) but that too often psychol- particular theoretical models can view skeptics as “here-

ogists present it too simplistically, which contributes to the tics” and employ a reverse burden of proof on skeptics.

reputation of psychologists as perceiving individuals as This closing down of dialogue is anathema to science.

programmable machines rather than complex, motivation- Undoubtedly, theory defenders may feel their own reputa-

driven, agentic people. Imitation also is too often discussed tions threatened should confidence in a theory (particularly

in the absence of other factors whether biological (Pinker, one with which their name is closely linked) comes under

2002) or motivational (Przybylski, Rigby, & Ryan 2010). doubt. But this preservation of ego should not be consid-

These simplistic portrayals of imitation or other automatic ered primary and used to diminish opportunities for open

responses to stimuli may be particularly attractive in rela- scientific dialogue in which skepticism even of “beloved”

tion to moral issues, such as highlighting the potential theories should be encouraged.

“harm” to minors because of exposure to objectionable Thus, we are well served to remember that scholars

stimuli . . . the “harm” coming through imitation of those are not immune to confirmation biases that are in play for

stimuli. However, this portrayal of imitation as senseless all people. Nickerson (1998) documents that confirmation

and automatic as opposed to purposeful and practical may bias is near ubiquitous, including in science and provides

contribute to the perception that psychology is out of touch examples of noted scientists who engaged in confirmation

with human experiences. bias practices in their scientific work. Individuals, includ-

ing scholars, are likely to spend longer scrutinizing evi-

Theoretical Rigidity and Lack of dence that challenges their prior beliefs (Edwards & Smith,

Open Dialogue 1996). Biased cognitions such as belief perseverance and

myside bias appear to be independent of intelligence

A further problem occurs when theoretical models of hu-

(Stanovich, West, & Toplak, 2013) and may be part of a

man behavior become rigid and purveyors of such theories

process that makes scientific debates both less productive

begin to see them as “truth” rather than heuristics that may

and more acrimonious.

need to be adjusted or, indeed, abandoned when a body of

contradicting new data comes to light. This can be partic- Advocacy and Science

ularly likely for theories that are rooted to public policy or

social morality advocacy goals. Theories that provide Perhaps one of the bigger challenges for academic psychol-

structure for advocacy goals, however well meaning, may ogy is the dual role that psychology often finds for itself in

effectively reverse the scientific process in which the pub- advocating for human welfare while at the same time

lishing process begins with a desired endpoint and the attempting to find objective scientific facts. This duality is

6 Month 2015 ● American Psychologist

APA NLM

tapraid4/z2n-amepsy/z2n-amepsy/z2n00515/z2n4383d15z xppws S⫽1 5/19/15 7:41 Art: 2014-3568

not surprising given that many of the subjects open to pursuit of a social agenda that may represent a particular

scientific psychology touch upon concerns related to psy- ideology rather than a pluralistic view of human welfare.

chological wellness, social justice, and public policy. Ar- As a potential illustrating point of the dangers of

guably, many individuals with academic appointments and scholars taking advocacy positions, in the 1990s, the Cen-

publishing in reputable scientific journals find themselves ters for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) lost funding

functioning both as scientists and as advocates for partic- for gun-violence research as a result of its perceived biases

ular policy or social justice goals. on the issue, particularly from Republican congress mem-

The difficulty is that advocacy and science are dia- bers, following statements by CDC personnel that appear to

metrically opposed in method and aim. On an idealistic specifically advocate gun control policy (e.g., New York

level, science is dedicated to a search for “truth” theoreti- Times, 1994; see Bell, 2013). Naturally, gun control/rights

cally even if that truth is undesired, inconvenient, unpalat- policy is complex, and it is reasonable to argue that oppo-

able, or challenging to one’s personal or the public’s beliefs nents of gun control may have looked for any opportunity

or goals. By contrast, advocacy is concerned with con- to defund studies of gun violence. However, where CDC

This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

structing a particular message in pursuit of a predetermined officials strayed beyond careful objective and policy-neu-

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers.

goal that benefits oneself or others. Because of these dia- tral presentation of data into an advocacy agenda, the CDC

metrically opposed processes, it is unlikely that either made it that much easier for politicians to argue, even if

organizations such as the APA or individual scholars are cynically, for the defunding of gun studies. I argue here that

likely to be successful at operating as both scientists and attempts by psychological science to attempt to juggle

advocates at the same time. Fundamentally, because advo- science and advocacy simultaneously risk the same issues

cacy may be more immediately attention-getting than sci- and damage the credibility of our field in the process.

ence, I propose that mixing science with advocacy almost

inevitably ends in damage to the objectivity of the former. Theoretical Issues: What Can

This may not be immediately apparent to the scholars Be Done?

themselves for whom partnerships with advocacy groups

may seem a “meeting of the minds” in pursuit of social The first answer to most of the issues I outline above is to

agendas. Yet the urge to intermingle science with advocacy seek ways to make psychological science more data-driven

can be detrimental to the scientific process, reducing ob- than theory-driven (although, to be clear, I am not advo-

jectivity and impartiality. As Grisso and Steinberg (2005, cating small sample exploratory studies likely to prove

p. 619) noted, “scientific credibility demands impartiality, difficult to replicate). At present, psychological science is

whereas advocacy is never impartial.” As the authors also too often in danger of reversing the scientific process by

note (p. 620), “when developmental scientists choose what proving how “true” theories are either for ideological or

they will study about children and their welfare, they are advocacy reasons. As a result, it is too easy to ignore

often motivated by personal beliefs and values about the inconvenient data, engaged in “obligatory” or “same-lab”

importance of child protection,” and these personal beliefs replications, and nudge data to fit existing theories, rather

and goals may lead to scientists knowingly or unknowingly than using data to falsify them. I advocate a straightforward

forcing data to fit these beliefs or goals. Close associations process. Theories should be developed from preexisting

with advocacy groups, particularly via research funding, data, with an active effort to search out data that may be

may further reinforce ideological values and remove the problematic for a theory in development. Such theories

scholars further from objective science. Additionally, should be able to provide clear, testable hypotheses, includ-

Brigham, Gustashaw, and Brigham (2004, p. 201) admon- ing clear guidelines for when those hypotheses would be

ished that “advocacy, however, requires conviction. Advo- falsified and when the theory itself should be considered to

cates ‘sell’ their positions so that they might convince be falsified. Tests of a theory should be preregistered with

others of a specific solution to a problem. Uncertainty is equal opportunity for publication, whether supportive or

unhelpful to the advocate as well as to the salesperson.” not. This proposal is neither remotely novel nor should it be

This objectivity is reduced further by the observation controversial but, at present, I do not suspect that it is the

that the body of psychologists tends to be uniform in beliefs norm.

and agendas that may not reflect the general populace Reestablishing a culture of falsification would be crit-

(Redding, 2001). Thus, the advocacy goals selected both by ical in moving the reputation of our field forward. So too

individual scholars and professional advocacy groups such would be reconsidering our close proximity to advocacy

as the APA may themselves be the product of self-selected goals. I strongly suggest that psychological researchers

political and social inclinations rather than representing a should avoid accepting funding from advocacy groups ad-

plurality of ideas and perspectives. Policy statements in vancing particular policy or social advocacy agendas, how-

pursuit of a particular set of ideological agendas, however ever well-meaning these may be. It is probably impossible

well-meaning, can place the profession inadvertently at to avoid any pressure to produce certain results whatever

odds with the remainder of the populace. Were this a matter funding source may be available, even with government

of pure science and data, this could be perceived as a brave funding, but avoiding obviously biased sources would be

stance in favor of “truth,” but because this comes in pursuit helpful.

of an advocacy agenda, the fragile nature of social science If psychological science is to consider examining

(see again Simmons et al., 2011) can become perverted in more complex theories of human behavior, which I gener-

Month 2015 ● American Psychologist 7

APA NLM

tapraid4/z2n-amepsy/z2n-amepsy/z2n00515/z2n4383d15z xppws S⫽1 5/19/15 7:41 Art: 2014-3568

ally endorse, this comes with a few caveats. First, such recommending a clear distinction between scholarly and

theories must remain empirically based and care must be advocacy activities.

taken to avoid hidden problematic assumptions. Second, Concerns about theory does not mean that theory has

more complex theories would require more sophisticated no value in psychology; of course, it does. We may simply

analyses, potentially driving up demands for power and need to consider alternate theoretical models that are less

larger samples. Individual experiments could test smaller mechanistic and speak to a broader range of human expe-

pieces of larger theories, but in general, scholars must be rience. As part of this, we may need to acknowledge that

aware of power needs and the potential for Type I errors to our current methods may not yet be able to definitively

promulgate a given theory beyond its natural life span. Put answer all questions of interest. Similarly, we need to be

simply, theory construction and testing needs to be done careful not to imply that the small effect sizes obtained in

with far greater care than in the past. Balancing the devel- most psychological data can be translated to a fully mech-

opment of more sophisticated theory with maintaining anistic view of human experience. The challenge for psy-

methodological rigor will not be a simple task. chology forthcoming will be in becoming more data-fo-

This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

Regarding the issue of advocacy, it is worth asking:

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers.

cused while acknowledging that the data we have may not

When does data in psychology become sufficient to en- always fully capture the human condition.

dorse a particular advocacy or political course of action?

When should psychological researchers feel comfortable Marketing of Psychology

vocally supporting advocacy or policy agendas related to

their field of study? This is obviously not an easy question Professional organizations are understandably interested in

to answer. promoting the field of psychology. Indeed, this is one of the

Three things should be acknowledged. First, policy- primary purposes for such institutions. At the same time,

makers and the public will often seek definitive answers marketing approaches may lead to making bigger promises

and support for particular agendas before the data is clearly than can be delivered, and advocacy organizations such as

able to do so (which, in fact, may never happen) and may the APA may display biases relevant to false positive

put pressure on scholars and groups such as the APA to claims of nonexistent social problems psychologists would

support these agendas. Second, data and even scholarly nonetheless fix. This next section turns to the issue of how

consensus often changes rapidly in psychological science; psychology is “sold” to the general public and how some of

thus, what is “true” one year may be falsified the next. these efforts may backfire. This is not to say that the field

Third, there is likely no existing shortage of social agenda should not reach out to the general public to explain what

advocates outside of the psychological research community we can do—just that, here again, a cautious and honest

and thus, little clear need for psychological researchers to approach may be most effective in relation to long-term

join these ranks. perception.

Thus, given the problems with advocacy in psycho-

logical science in the past, I suggest that the default posi- Policy and Other Official

tion for psychological researchers should be to simply Public Statements

present and clarify research data carefully, warts and all,

and restrain their statements to specific comments on data One means for demonstrating that a profession is active in

including corrections to any hyperbole or misstatements the global community and promote itself is to attempt to

made by advocates or policymakers. Obviously, many psy- connect research to policy issues under debate in society.

chological researchers may be displeased by this recom- Policy statements take many forms and serve multiple

mendation but, until our scientific culture changes so that purposes. For instance, professional organizations may re-

we have a clearer, objective read of data even in socially lease policy statements that pertain to professional ethics or

sensitive areas, indulgence in advocacy will only continue that otherwise are intended to state positions directly rele-

to damage the objectivity of psychological science. If is- vant to the field. Policy statements may also pertain to

sues such as the replication crisis, lack of transparency, and issues less directly relevant to the field with the implication

QRPs appears to clear in the future, this stance could be that research from the field can be helpful in guiding policy

reassessed then, but only with great caution. debates in other realms. In effect, these policy statements

This does not mean that scientists cannot provide take a stance on a particular debated issue and imply that

information to interested policymakers, only that such in- psychological science can or should be used by others to

formation should be strictly data-based, include data that help inform their decisions as well. Such policy statements

may conflict with the scholar’s personal views, and be can appear beneficial to the field to the extent that they

restrained from interpretations advocating a particular garner press attention and support from advocates of the

course of policy. In other words, “Just the facts, ma’am.” position advanced by the policy statement.

This also does not mean that advocacy cannot be informed The website of the APA’s Public Policy Directorate

by science, naturally, it can. Furthermore, scholars can (http://www.apa.org/pi/guidelines/index.aspx) lists approx-

certainly advocate for causes in which they believe. How- imately 70 – 80 active policy statements, in addition to

ever, it may be wise for scholars not to function as advo- several advocacy letters to government officials and a doc-

cates on topics on which they do research. As such, I am ument detailing 52 resolutions concerned with the status of

8 Month 2015 ● American Psychologist

APA NLM

tapraid4/z2n-amepsy/z2n-amepsy/z2n00515/z2n4383d15z xppws S⫽1 5/19/15 7:41 Art: 2014-3568

Fn1 women in psychology.1 By contrast, the American Society careful representation of science (Goffin & Myers, 1991;

of Criminology (ASC) lists only three advocacy letters to O’Donohue & Dyslin, 1996; Olson, Soldz & Davis, 2008)

government officials and two statements from the policy and fail to distinguish whether hard data or personal opin-

committee related to incarceration and the death penalty, ion is guiding policy stances (Martel, 2009).

which both carry the disclaimer that they represent the Policy statements may be further reduced in objectiv-

Fn2 policy committee, not necessarily the ASC.2 Thus, the ity when they are written by specific groups of scholars

APA appears to be particularly enamored of policy state- highly invested in specific advocacy goals. It is perhaps this

ments. Naturally, making direct comparisons between two past point that is most critical. To the extent that profes-

fields of different sizes must be done with caution, but both sional organizations such as the APA attempt to “sell” their

psychology and criminology address issues related to pub- opinions on various social issues as well-replicated find-

lic policy, yet take clearly different approaches as to the ings, such organizations can risk damaging the credibility

appropriate frequency of such policy statements and when of the field as an objective arbiter of information on human

a threshold of evidence has been reached to support them. behavior.

This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

Although the opportunities for news media attention I provide three examples of APA position and/or

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers.

and political influence that come with policy statements are policy statements that are arguably problematic. The first

understandable, there are also risks associated with the use concerns the reaction of the psychological community as

or, perhaps, overuse of policy statements. First, the field of exemplified by task forces and position statements pro-

psychology can develop a reputation for being opinionated, moted by the APA that appear to be critical of the Personal

particular to the degree that policy statements extend into Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act

areas of human welfare, however well intended, that are of 1996 (PRWORA). PRWORA was a bipartisan welfare

beyond the strict realm of a science that strives to be reform effort of the 1990s that has generally been consid-

objective. This is particularly risky when psychologists ered successful by politicians in both parties (e.g., The New

themselves do not represent a pluralistic view of social and Republic, 2006). Nonetheless, a task force of Division 35

political perspectives (Redding, 2001). Consistent with this (Psychology of Women) in apparent cooperation with the

observation, policy statements by the APA and other sci- APA’s Public Policy Office, released a position paper that

entific organizations appear to support generally left-lean- appeared critical of PRWORA and portrayed many citi-

ing positions likely to alienate social conservatives (the zen’s concerns with welfare as “myths” (Task Force on

allegation that the APA colluded with the Bush adminis- Women, Poverty, and Public Assistance, 1998). This is not

tration to allow psychologists to participate in enhanced to say that the position statement was without valid points,

interrogations during the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan is but rather that it took only a limited (and arguably left-

the obvious, yet still problematic, counter example. Risen, leaning) perspective, appeared to unintentionally disparage

2014). Scholarly organizations such as the APA have con- alternate perspectives, and arguably attempted to apply

sistently failed to distinguish, in their public policy state- psychological science to a real-world scenario where it may

ments, between scientific “truths” (which are few and far have been ill-suited. Although certainly well intended, this

between) and policy positions that can be informed by, but position statement ultimately appeared to place psychology

not dictated by psychological science. in opposition to a bipartisan and largely successful (al-

Second and related, the impact of each policy state- though certainly imperfect) effort to address a pressing

ment arguably becomes less the more policy statements are social problem.

issued. An objective scientific organization taking the un- The second example concerns various policy state-

usual step of releasing a policy statement on a particular ments by the APA on the issue of abortion. As a moral

issue can have dramatic impact, particularly when the issue, many may agree with the APA’s proabortion rights

reputation of the field as an objective neutral arbiter has

stance (for the record, this author is staunchly neutral on

otherwise been maintained. However, frequent use of pol-

this issue). But should a scientific organization take a

icy statements, particularly on advocacy issues that are up

stance on a purely political/moral issue particularly when it

for debate in the public sphere, can ultimately result in the

(potentially selectively) cites scientific articles in support of

field developing the reputation as an invested politicized

this position? The APA has multiple policy statements

entity and the impact of such statements is reduced.

dating from 1969, 1980, and 1989, and including a 2008

Third, by becoming invested in particular social ad-

task force report on the research (APA Task Force on

vocacy issues, the field may inadvertently engage in cita-

Mental Health & Abortion, 2008). The 2008 task force

tion bias, only citing scientific evidence supporting a policy

statement while ignoring scientific evidence that contrasts appears to provide scientific rationale for previous policy

with the policy statement. Such policy statements may

gravitate toward sweeping politicized statements while 1

The actual number of policy statements is arguably much larger,

misrepresenting, intentionally or unintentionally, nuances including internal policies and older policy statements technically still on

or discrepancies in the research. the books. A full listing of APA policy statements is provided at http://

Thus, it is not surprising that many policy statements www.apa.org/about/policy/index.aspx.

2

It is worth acknowledging that, in conversation with the current

by both psychological and other health and behavioral President of the ASC Chris Eskridge (personal communication, August

health organizations have been criticized for inaccuracies, 25, 2014), he noted that the ASC continues to debate whether to be more

lack of clarity, and a tendency to put agenda before a or less active in the policy arena.

Month 2015 ● American Psychologist 9

APA NLM

tapraid4/z2n-amepsy/z2n-amepsy/z2n00515/z2n4383d15z xppws S⫽1 5/19/15 7:41 Art: 2014-3568

statements, concluding that a single abortion for unplanned the task force currently reviewing the literature on video

pregnancy did not impact women’s mental health any more game violence, which likewise has been criticized as ap-

than continuing the pregnancy. While certainly noting po- pearing to be purposefully weighted with individuals with

tential issues for women with multiple abortions, the task a priori antigame views (Ferguson, 2014).Such policy

force concluded that (p. 4) “In general, however, the prev- statements arguably mistake science for moralization and

alence of mental health problems observed among women indulge in “culture war” and damage the credibility of

in the United States who had a single, legal, first-trimester scientific organizations once research disconfirming the

abortion for nontherapeutic reasons was consistent with policy statements can be readily identified. Scientific orga-

normative rates of comparable mental health problems in nizations should, at minimum, present a full summary of

the general population of women in the United States.” research, including conflicting findings, not merely that

Prolife groups have criticized the APA for being selectively supporting a policy statement.

critical of research that conflicts with their policy state- There are many other historical examples of policy

ments, ignoring methodological flaws in research support- statements or other public statements that appear either to

This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

ing their position, and allowing tasks forces to be com- have little to do with psychological science, are simply

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers.

posed of scholars with a priori pro-choice moral stances left-leaning takes on policy issues, or seem simply unnec-

(e.g., Ertelt, 2006) who downplayed results from studies essary because they take positions few would disagree

associating abortion with subsequent mental health issues with. Examples of politicized policy statements include a

in women (e.g., Fergusson, Horwood, & Boden, 2008; 1982 policy on limiting the nuclear arms race; 1969, 1980,

Pedersen, 2007). and 1989 policies supporting abortion; and various policies

Current APA policy (initially implemented in 1969, or other public statements supporting liberal issues, includ-

updated in 1980, and to the knowledge of this author, ing affirmative action, equating Zionism with racism,

remaining in effect) states “that termination of pregnancy same-sex couple rights, and the Affordable Care Act. Un-

be considered a civil right of the pregnant woman.” It is necessary resolutions (so-called because the position of any

unclear that it is appropriate that social science be used to reasonable entity should have been obvious) include a 2008

make such a moral and policy determination. For instance, resolution against genocide, a 2002 resolution stating that

it is unclear the degree to which women’s mental health psychologists should work to reduce terrorism, and a 1999

consequences related to abortion are critically meaningful resolution against child sexual abuse.3 Some policy state- Fn3

regarding whether abortion is moral. Nonetheless, the re- ments such as that on Zionism and arguably abortion may

sults of the 2008 task force appear to be geared to support lack cultural sensitivity toward groups these may offend. It

a moral stance by the APA. Furthermore, there is concern is not my position that these opinions by the APA are

that policy and task force statements by the APA presented “wrong” (in fact, I share most of them), but rather that the

a far more conclusive portrait of the research literature than APA simply expresses what are, indeed, opinions too often,

may have been warranted by inconsistent data. It is not the obfuscates policy opinion for scientific fact, and consis-

intent of this article to take a position on abortion and tently leans in a liberal political direction in a way that

mental health, only to suggest that policy statements such alienates many policymakers and the general public.

as these may create a “tail wags the dog” effect in which This is not to say the policy statements are never

science is selected to support a preexisting policy instead of warranted, of course. Policy statements that directly relate

science being carefully and objectively communicated to to the practice of psychology are well within the purview of

policymakers and the general public. Moral positions that organizations such as the APA. Condemnations of thera-

can certainly be informed by science but not determined by pies designed to alter sexual orientation are an example of

science and it is unclear whether it is wise for professional policy statements that take a stance on an issue of social

groups to endorse moral positions. justice, while still grounded in empirical data and practice

The third example concerns the APA’s 1994 policy within the field. Policy statements in other areas less related

statement on media violence (APA, 1994) and subsequent to psychological practice may also be warranted so long as

2005 policy statement on interactive media violence (APA, the policy is clearly identified as one of advocacy rather

2005). These statements, and others like it, have long been

than science. However, frequent use or overuse of advo-

criticized for failing to include research findings that con-

flicted with the policy statement (see Freedman, 1984, for

a discussion of conflicting findings predating the 1994 3

However, it is granted this policy statement has a curious history

resolution), presenting inconsistent research findings as and appears to be in response to an article published in Psychological

consistent, and extending often problematic research pro- Bulletin that appeared to minimize the impact of child sexual abuse (see

Lilienfeld, 2002, for full history). In a letter to Congressman Tom Delay,

grams into a real-life social issue when the external validity then APA CEO Ray Fowler (1999) noted that this policy statement was

of such conclusions were in doubt (see Dillio, 2014; Hall, intended to reaffirm the APA’s position on child sexual abuse. Dr. Fowler

Day, & Hall, 2011; O’Donohue & Dislin, 1996, for recent also stated “We acknowledge our social responsibility as a scientific

discussions). The tasks forces creating these statements, as organization to take into account not only the scientific merit of articles

in other controversial areas, have also been criticized for but also their implications for public policy” which, aside from the

obvious seriousness of the topic of child sexual abuse, I argue is a

appearing stacked with members likely to endorse a par- worrisome position for a scientific organization to take. Should we not

ticular view without counterbalancing of differing views. publish valid scientific research if it is inconvenient for public policy

Unfortunately, this trend appears to have continued with objectives?

10 Month 2015 ● American Psychologist

APA NLM

tapraid4/z2n-amepsy/z2n-amepsy/z2n00515/z2n4383d15z xppws S⫽1 5/19/15 7:41 Art: 2014-3568

cacy agendas run the risk of undermining the scientific guson, 2009; Hsu, 2004; Kraemer, 2005). Without delving

reputation of fields that release too many on too many too far into the “inside baseball” of the statistics, the

issues while blurring the lines between science and advo- problem was one of nonequivalence, namely the tendency

cacy. for medical studies to use different effect size indices

(typically odds ratio or OR) based on different types of data

Small Is Big than those commonly employed in psychological science

One issue that has plagued psychological science is the (most typically either Pearson r or Cohen’s d). Thus, to

observation that so many results from empirical studies make comparisons it was necessary to convert OR into “r”

demonstrate only very small effects, the practical signifi- or “d.” In most cases, this transmogrification was done

cance of which is unclear (Wilson & Golonka, 2012). For using formulas that include sample size as a denominator

instance, in one recent survey of meta-analyses in psychol- term (despite the fact that sample size and effect size

ogy, the authors found that most meta-analyses found av- should be independent). The problem arises with medical

erage effects (in terms of r2 here for ease of understanding) epidemiological studies in which the number of partici-

This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

pants reaches into the tens and even hundreds of thousands

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers.

in the range of 0%– 4% (corresponding to rs below .1

through to .2, with few above this level) shared variance (such as the Salk vaccine trials or the physician’s aspirin

between independent and dependent variables, with many study, two studies falsely highlighted as having “small” r

of the effects at the range of 1% and lower (Ferguson & effect sizes). Using sample size as a denominator term for

Brannick, 2012). Bakker et al. (2012) reported slightly the conversion of OR to r dramatically truncates the resul-

higher average effect sizes in meta-analyses (reported as tant r value to near zero. That this seemed “good news” to

approximately d ⫽ .37, p. 547), although the authors sug- psychologists used to defending r values in the .1 to .2

gest that these effect sizes are likely inflated by QRPs. Too range seems to have acted as a block to asking whether

many papers have been written on the topic of effect sizes such results were too good to be true and might have been

and their interpretation to do remote justice to covering the product of flawed formulas. Related to this is the

them here. However, the concern expressed here is that, too observation that most of the medical samples in question

often, the field has constructed pat explanations for why used skewed samples, detecting relatively rare events such

“small is big”; that is to say, the small effects typically as cancer in large populations. It is inappropriate to make

demonstrated in psychological science remain of tanta- direct comparison between samples with differing distribu-

mount practical significance. tions, using very different types of outcome analyses. Un-

One of these is the argument that small effects spread fortunately, these comparisons between medical and psy-

over a wide population can still be of great significance chological research are statistically meaningless.

even if only a small proportion of people are influenced. However, and as the second point, even had they been

For example, if a study finds that viewing more negative meaningful statistically, they were nonetheless an “apples

words on Facebook is associated with a decline in mood of and oranges” comparison. Psychological research very of-

0.07% (e.g., Kramer, Guillory, & Hancock, 2014), the ten has to contend with “proxy” measures that estimate the

argument sometimes seen is that, in a population of, say, actual behavior of interest. Neither laboratory measures of

one billion worldwide users, if Facebook even influenced behavior sampled under unrealistic and unnatural circum-

only 0.07% of them, that is still 700,000 people dramati- stances nor self-report surveys are a true measure of most

cally influenced (and presumably endangered) by Face- of the behaviors that interest us. Thus, even for the best

book. However, this argument fundamentally misrepre- measures of behavior, there are issues related to reliability

sents the effect sizes. The r2 demonstrates the typical and validity. However, many medical epidemiological

impact on the average user, not the proportion of users studies measure mortality or pathology rates that are not

impacted in a more dramatic fashion. Presumably few proxy measures; put simply, death is a perfectly reliable

individuals would note 0.07% (that is about 1/15th of a and valid measure of death. Thus, overzealous comparisons

percent, not 7% reduction in mood from one day to the between psychological and medical research are fraught

next; Grohol, 2014). and potentially do more to make the field appear desperate

The other common and equally problematic argument rather than rigorous.

seen sometimes is the temptation to compare psychological

effect sizes with those found in important medical studies, Juvenoia

with the implication that psychological effects sizes are

bigger than those perceived in vital medical studies (e.g., Juvenoia, or the fear of youth among older adults, is a term

Meyer et al., 2001; Rosnow & Rosenthal, 2003) and have coined by sociologist David Finkelhor (2010) and involves

been used to defend weak claims in psychology up through society’s efforts to find “evidence” that youth today (in any

and including parapsychology (Bem & Honorton, 1994). generation) are, somehow, psychologically worse than in

That these claims are “good news stories” for psychology previous generations. Psychological science can unwit-

is obvious, but they are problematic on two levels. tingly promote juvenoia through claims insinuating unfa-

First, the calculations made to compare medical to vorable psychological characteristics of the current gener-

psychological effects are based on statistical analyses that ation of youth, compared with previous generations.

are now known to be flawed (Block & Crain, 2007; Fer- Research directed at such claims may appear to be partic-

Month 2015 ● American Psychologist 11

APA NLM

tapraid4/z2n-amepsy/z2n-amepsy/z2n00515/z2n4383d15z xppws S⫽1 5/19/15 7:41 Art: 2014-3568

ularly lucrative in regards to grant funding, book sales, (Brown et al., in press), exaggerated press releases likely

prestige from older adult members of society, and so forth. contribute to “myths” about psychology rather than a care-

Examples of this in psychological science include the ful and systematic understanding of psychological pro-

disparagement of the recent generation of youth as experi- cesses. It has been observed that new research often expe-

encing a “narcissism epidemic” (e.g., Twenge & Campbell, rienced a decline effect (Shooter, 2011) wherein many

2009), being less empathic (Konrath, O’Brien, & Hsing, initial results ultimately prove difficult to replicate. With

2011) or incapable of rational thought because of alleged this in mind, exaggerated press releases on novel but un-

structural deficits in the brain (Galván, 2013). Such narra- replicated findings can do more to misinform than inform

tives about youth may fit well with typically generational the general public.

struggles in which older adults may enjoy hearing “evi-

dence” that youth are less rational or desirable than older Marketing of Psychology: What Can

adults are. However, the validity of these lines of inquiry Be Done?

that apparently disparage youth have often been questioned

This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

The issues surrounding the marketing of psychology all

(e.g., Grijalva et al., 2015; Males, 2009; Willoughby,

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers.

focus on the difficulty in balancing a desire to attract

Good, Adachi, Hamza, & Tavernier, 2013), and statistical attention to our work while appropriately retaining a con-

evidence suggests that the current generation of youth are servative and objective perspective. Much can be done

psychologically healthier on most outcomes, compared simply by changing the culture related to marketing psy-

with previous generations (Childstats.gov, 2014). Coupled chology. Certainly, psychological science should be active

with an apparent overeagerness to condemn elements of in promoting “truth” and questioning “myths” related to

youth popular culture as “harmful” based on weak data (see human behavior (Lilienfeld et al., 2009). At the same time,

Adachi & Willoughby, 2013; Hall, Day & Hall, 2011; psychological science must be careful, in its eagerness to

Steinberg & Monahan, 2011, for discussions), psychology promote itself, not to inadvertently create new myths that

may appear to be overly willing to contribute to genera- come from within psychological science as opposed to pop

tional squabbles, particularly at the expense of youth, rather psychology.

than functioning as fair arbiters of careful science. Some of the issue is a failure to learn from history,

Juvenoia among psychological researchers is unlikely such as on the issue of juvenoia. Scholars making dramatic

to go unnoticed among youth themselves, who may be negative statements about “kids today” is nothing new, yet

exposed to a litany of scholars describing them or the our field persists in such behavior. Similarly, “small is big”

culture they value in reproachful terms. Such exposures to arguments, particularly those based on comparisons to